Here is a puzzle. In the Middle Ages there was terrible poverty. Britain was afflicted by at least ninety-five famines. In 1235, some twenty thousand Londoners died of starvation and many resorted to eating tree bark for survival.486 Yet in the most famous piece of literature from that time – the Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer – the word ‘poverty’ can be found only twenty-six times.487

‘Poverty’ used to mean lack of clothing and ‘wasted hunger’.

A little later, during the time of the Tudor kings and queens, poverty was less common yet there were still famines. Peasants – the majority of the population – shared unheated hovels without toilets or baths. Yet in the entire works of Shakespeare, the word ‘poverty’ appears a mere twenty-four times.

Moving up to the nineteenth century, the condition of the poor had vastly improved. Clogs were routine at the beginning of the century and unusual by the end. The cost of food and clothing went down while average incomes went up. Yet curiously, Charles Dickens used the word ‘poverty’ vastly more than Chaucer and Shakespeare combined – a whopping 179 times.

In our own time, living standards have been transformed yet again. The cost of food has fallen through the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries while incomes have multiplied. The percentage of income spent on food has fallen dramatically. Clothes, too, have become cheaper. More than 99 per cent of households have a television. The major nutritional problem for the less well-off in British society is now obesity.

Yet in the face of this, use of the word ‘poverty’ is vastly greater. In the House of Commons in 2002, the word was used in 1,307 speeches.488 In many of those speeches it was used several times.

It seems back to front. As poverty has receded, the use of the word has soared. What can explain it?

To find the answer, we might listen in to two conferences. First, the Labour Party conference of 1959. It was the first conference after the Conservative Party had won three general elections in a row. Naturally, Labour Party members were depressed. Barbara Castle, the chairman of the conference, said in an aside, ‘the poverty and unemployment which we came into existence to fight have been largely conquered.’489 Her remark was a kind of explanation why Labour had been in so much trouble for so long. It appeared to her that it had lost its raison d’être. Without poverty, what need was there for a Labour Party? It was a problem in need of a solution.

Let us move forward in time three years to the second conference: the annual one of the British Sociological Association. Peter Townsend, a protégé of Richard Titmuss, Professor of Social Administration at the London School of Economics, presented some of his research findings and theories on poverty. Another of Titmuss’s protégés was Brian Abel-Smith. The trio had been working on redefining poverty. Abel-Smith and Townsend had argued that the amount given in what was then called supplementary benefit should be considered as the ‘poverty line’. Anybody with less income than that should be categorised as ‘in poverty’. Anyone with less than that amount, plus 40 per cent, should be termed ‘on the margins of poverty’.

This redefinition of poverty gained critical mass among left-wing academics at this conference in 1962. Harriet Wilson was there. She too had published research on related subjects: hardship among unmarried mothers, large families and the elderly. She said that in all the evidence about the poor at the conference and the redefinition of ‘poverty’, there was developing ‘a mood of conspiratorial excitement’. Her words, not mine. So, one of those at the heart of the redefinition of ‘poverty’ used a word based on the idea of a ‘conspiracy’.

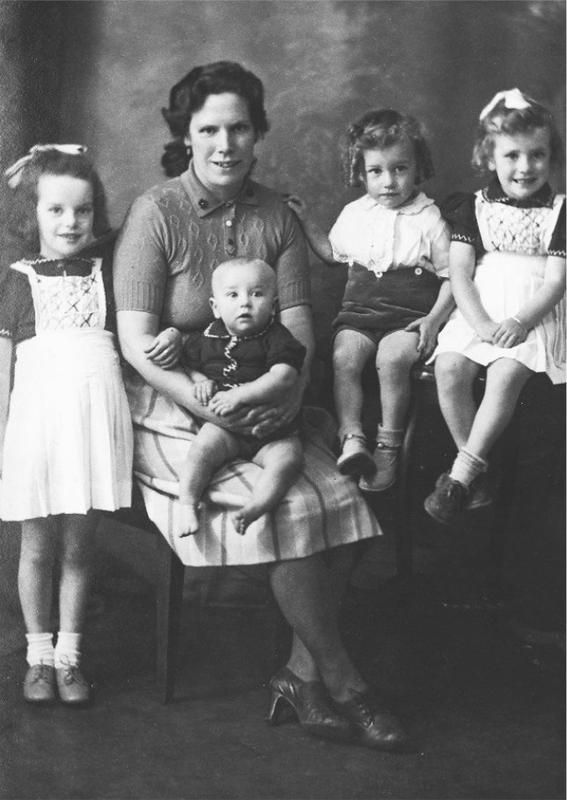

‘Liam’ (Bill Cullen) is second from the right.

Bill Cullen is now a multi-millionaire but he was brought up in a slum in Dublin, living without a bathroom or ‘electric light bulbs that go on with a switch’. In his fictionalised autobiography, It’s a Long Way from Penny Apples,490 he writes of how, when he was a child, he asked his mother one day why she gave money to the nuns.

‘For to help the poor,’ she replied.

‘But aren’t we poor?’ he asked.

She gave him one of her twinkling smiles and said,

‘Not at all, son. You’re not poor. Haven’t you a roof over your head. Clothes on yar back. Kossicks [gumboots] on yar feet. Good food every day. As healthy and strong as a young bull, you are. With a mammy and daddy who minds ya and loves ya … No, son, we’re not poor. We’re very rich.’

The historian of this change in the use of the word ‘poverty’, Keith Banting, refers to it as ‘explicitly political’. There was a desire to shock – to use a word that, to most people, meant starvation, homelessness and lack of clothing.

In The Parson’s Tale – one of the Canterbury Tales, in which the word was sparingly used – those condemned to hell were said to be going to suffer the misery of poverty which is defined, among other things, as lack of food and drink – ‘they shall be wasted hunger’ – and lack of clothing: ‘they shall be naked of body save for the fire wherein they burn.’ That idea of ‘poverty’ is vastly different from the government’s current definition which, following the influence of the 1962 ‘conspiracy’, now defines those with incomes 60 per cent of average or below as being in ‘poverty’.

The word was redefined by politically motivated people. It was a clever piece of propaganda. The word still carries the emotive force of the old meaning but now only means people that are less wealthy than others.

One can only wonder what someone in 1235, chewing bark in a desperate attempt to stay alive, would have made of it.

Notes

486 Encyclopaedia Britannica 1998 CD-ROM.

487 www.concordance.com. The modern English translation of Chaucer is used.

488 Hansard website search.

489 Quoted in Nicholas Timmins, The Five Giants: A Biography of the Welfare State (HarperCollins, London, 1995), p. 255. The material on Townsend, Titmuss, Abel-Smith and Wilson also comes from this book, pp. 255–8.

490 Mercier Press, Dublin, 2001.