There have certainly been changes for the better in the past fifty, sixty years and more.

Our average wealth has much increased. This new wealth gives us freedom to drive where we like, go on holiday abroad and take longer holidays. Fifty years ago, even senior management worked on Saturday mornings and most people had holidays of two weeks or less. Now nine out of ten people have a holiday entitlement of four weeks or more.1 There are more and better restaurants. The pill has helped to make sex between unmarried people commonplace, suggesting increased physical pleasure, whatever the emotional and other effects may be. People are less constricted. These can all be held out as improvements in the quality of our lives.

But what else has changed? What are British people like now and how does that compare with how they used to be? It is the most profound question you can ask about a country and one of the most difficult to answer.

I will offer some objective ways of gauging how we have changed later on. But first, here are some images of the British, past and present.

Were the British really like that?

Professor Geoffrey Gorer, a psychologist and anthropologist, wrote about all sorts: the inhabitants of a Himalayan village, the Americans and the Russians. Finally, in the early 1950s, he turned his attention to his own people. His research was sponsored by The People, which had an estimated readership of 12 million at the time, and appeared in his book Exploring English Character.2

As a psychologist he was puzzled. He took it for granted that aggression was part of human nature. What he found intriguing about the English was that their natural aggression was so successfully controlled.

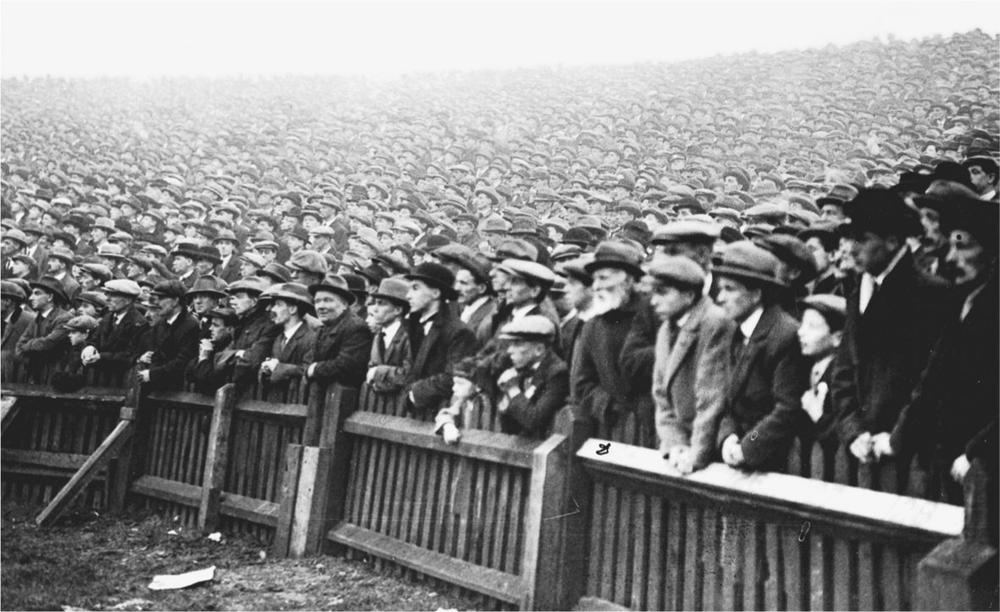

In public life today, the English are certainly among the most peaceful, gentle, courteous and orderly populations that the civilised world has ever seen … You hardly ever see a fight in a bar (a not uncommon spectacle in most of the rest of Europe or the USA) … Football crowds are as orderly as church meetings. … This orderliness and gentleness, this absence of overt aggression calls for an explanation.

The crowd at a Bristol Rovers versus Bristol City match in 1935. ‘Football crowds are as orderly as church meetings,’ observed Professor Gorer.

He was puzzled all the more because the English had not always been this way. In the seventeenth and eighteenth century they had been pugnacious and violent. But somehow, during the nineteenth century, violence and pleasure in fighting had almost completely disappeared and England produced, instead, institutions of care and philanthropy such as the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals.

George Orwell, from a very different standpoint, came to a similar conclusion. He wrote in 1944: ‘An imaginary foreign observer would certainly be struck by our gentleness; by the orderly behaviour of English crowds, the lack of pushing and quarrelling … And except for certain well-defined areas in half-a-dozen big towns, there is very little crime or violence.’3

George Santayana, the leading American philosopher, lived the latter part of his life in various parts of Europe including Britain. In 1922 he wrote:

The Englishman … is disciplined, skilful, and calm – in eating, in sport, in public gatherings, in hardship. … He is the ideal comrade in a tight place; he knows how to be … well-dressed without show, and pleasure-loving without loudness. … What ferocious Anglophobe … is not immensely flattered if you pretend to have mistaken him for an Englishman?’4

And again, ‘The Englishman’s heart is seldom designing or mean. There are nations where people are always … cheating in small matters, to get out of some predicament, or secure some advantage … Such is not the Englishman’s way.’ The praise of the British up to at least 1960 is so fulsome it may surprise younger people.

Where did the good behaviour come from?

It seems the ideal of good behaviour became prevalent during the nineteenth century. The words varied. Among the working, it was considered important to be ‘respectable’ and of ‘good character’.5 The word ‘character’ had an extra meaning. It could be a written testimony by an employer about a man’s qualities – his honesty, industriousness, sobriety and punctuality.

A working-class man could be ‘respectable’ even if less well-off than another worker who was ‘rough’. Even children shared in a sense of family and individual self-respect. Working-class memoirs reveal that children thought it natural that they should help in the house and then, as they got older, earn small sums by running errands or doing chores for neighbours. Finally they would get a regular job. As Gertrude Himmelfarb, who has specialised in nineteenth century culture, put it:

Part of the ethos of work was the pride of growing up, assuming the mantle of adulthood, and with it of work. But part of it was also a sense of responsibility to the family and, beyond this, a sense that work itself was something to be proud of, a source of self-respect and the respect of others.6

Among the middle class, the terms were different but the meaning was similar. The terms ‘gentleman’ and ‘lady’ denoted moral qualities almost as much as social status. Hippolyte Taine, writing just after the middle of the century, contrasted the French gentilhomme with the British gentleman. The former was elegant, stylish and chivalrous. The latter was a ‘disinterested man of integrity’ capable of ‘sacrificing himself for those he leads’ and a man ‘of honour’. A ‘gentleman’ in the latter half of the nineteenth century was honest, gracious and considerate to others. This concept remained part of British culture right up to fifty years ago at least.

The culture of decency was reflected and perpetuated in children’s books in the 1950s. In Little Women, Christian kindness permeates the pages. Consideration for others was a moral duty which, early in the story, means the children give up their special Christmas breakfast and take it round to people more seriously poor than themselves. In Children of New Forest, honour, bravery, self-reliance and loyalty are implicitly the characteristics that are most valued.

Each of the short stories in Tales after Tea by Enid Blyton has a firm moral. An Alsatian dog bullies and frightens other animals. It gets its comeuppance. A boy is rude and aggressive to other children who have been building a sandcastle. He takes over and insists on getting on top. He ends up surrounded by sea and in fear for his life. He is saved, but gets a powerful lesson in modesty and consideration. The children to whom these stories were read were being taught a moral system.

And what about now? What are the modern British like?

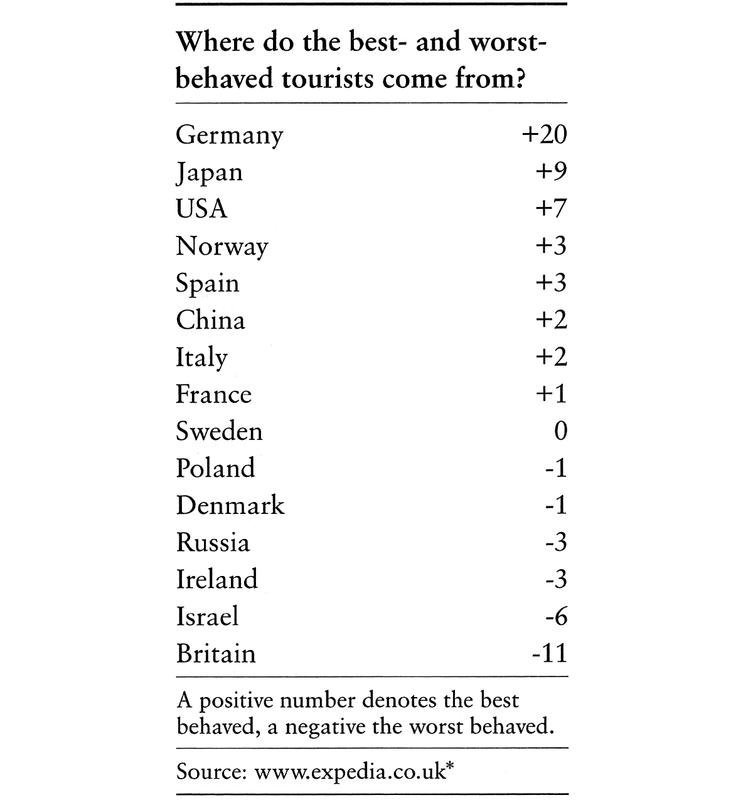

A travel company called Expedia.co.uk contacted tourist offices in seventeen countries and asked how they regarded their visitors. From the answers, Expedia created a league table.

Germany easily came out best. Tourists from Japan and the USA were also repeatedly mentioned as being well behaved. The worst-behaved tourists were the British. They were rated the worst or second worst by more than half the tourist offices polled.

The British take their crime with them on holiday. In Rhodes, the police said in 2003 that British tourists had created a crime wave. The resort of Faliraki was particularly hard hit. Out of 105 people who were arrested, ninety-nine were British.8

Even the British themselves no longer think they are polite and considerate. Birmingham Midshires Building Society asked people whether they thought that most Britons gave up bus or train seats for women and the elderly. Seven out of ten said ‘no’. In a Gallup poll, four out of five people who expressed an opinion believed that British society today is less moral than fifty years ago.9 A large majority felt that we leave it too much to individuals to develop their own moral code. We do not have an agreed set of moral standards.

Swearing is now so commonplace that it appears regularly on television and even people who know they are being filmed have been known to swear obscenely. In a Channel 4 series called Wife Swap, Justin Wells lived for a while with Kellie Ansell, a vegan. She removed his cola drinks from the fridge which provoked him into a tirade in front of his son Dre, two, and his step-daughters Antonella, twelve, and Amy, nine.

‘There was nothing said about f***ing fizzy drinks. I’ll have whatever I f***ing want. That’s all b******s. I’ll wipe my f***ing a*** with that,’ he said.

One of his children said he was not allowed to swear in front of them. He replied, ‘F***, f***, f***. There you go.’

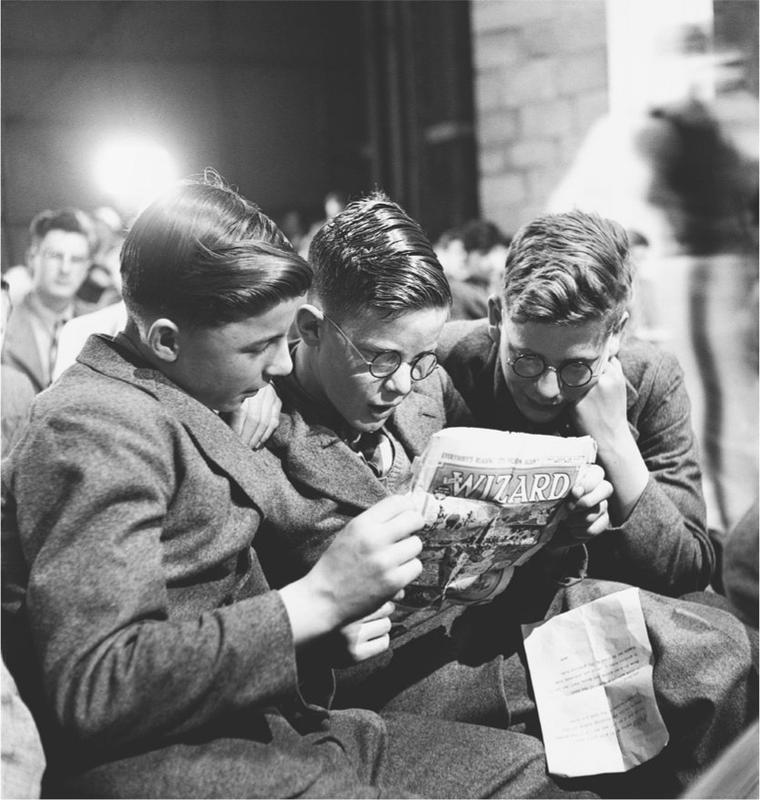

Children reading The Wizard in 1948. Children and teenagers in the 1940s and 1950s wore uniforms, shoes (polished) and perhaps flat caps.

Youths today often wear hoods which obscure their faces or baseball caps, back to front. A significant minority walks in an intimidating way – hunched over, as if absorbed in anger or depression.

An affair that never took place

Two ordinary middle-class people are in the tea room of a suburban train station. A cinder from one of the steam engines gets into the eye of one of them, Laura Jesson. Alec Harvey, a doctor, comes to her aid and gets it out with the end of a handkerchief. This is the beginning of the classic film, Brief Encounter, released in 1945. Laura, played by Celia Johnson, rushes off immediately to catch her train and thinks no more about it. But they accidentally meet again since they both travel by train into town each Thursday. Both are happily married but, as they get to know each other better, they fall in love. Alec, played by Trevor Howard, becomes increasingly ardent and Laura is powerfully attracted to him – he is dashing and handsome whereas her husband is neither.

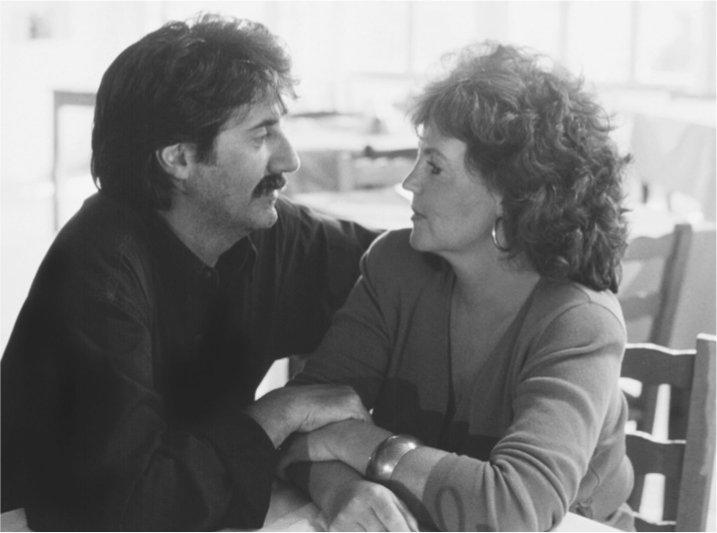

Towards the end of the film, Alec wants to consummate their passion and start life afresh with her. Laura is tempted but summons up her courage and, instead, stops the relationship entirely. She goes back to her stolid husband. At the end of the film, she is seated in her suburban home with him. It is a strange tale by modern standards – about an affair that does not happen. Laura is powerfully attracted to Alec but quells her excitement. Why?

Trevor Howard and Celia Johnson in Brief Encounter, 1945. The story is about a woman who decides not to be unfaithful to her husband.

Implicitly because she thinks it right. She loves and is committed to her son. If she embarked on an affair or divorce, it could hurt him. As for her husband, although she no longer loves him passionately, she sees him as a decent person to whom she has made a commitment. She sees no justification for breaking that commitment. He has done his best. The struggle within her is between her desires and her moral sense. Her sense of honour, or duty, is an integral part of the way she makes decisions.

Forty-four years later came another British film about a woman tempted to be unfaithful to her husband. The eponymous heroine in Shirley Valentine – played by Pauline Collins – is bored with her life and feels her husband has lost the sparkle which first attracted her to him. Egged on by a girlfriend, she flies off to a Greek island. There she is attracted to a Greek man, played by Tom Conti, who seems excitingly romantic. They go to bed on their first date. The event is not portrayed as a grave decision but as a moment of liberation.

Pauline Collins and Tom Conti in Shirley Valentine, 1989. The story is about a woman who has no hesitation in being unfaithful to her husband.

Her husband, Joe, follows her to Greece. Implicitly it is all his fault that she went off at all and he is the one who ought to be ashamed. He has been boorish and mundane. The film-maker does not suggest she had any responsibility to keep her marriage vows to him. Her responsibility is not to others – not even her husband. Only to herself.

Of course not everyone was faithful to their husbands in the 1940s and 1950s. But Brief Encounter suggests the culture at the time had a strong sense that married people ought to be faithful.

Another change in morality is revealed in the 1953 film Genevieve. Two old friends race their vintage cars against each other on the annual London-to-Brighton rally. Alan, the family man – played by John Gregson – is sure his car will beat that of Ambrose, played by Kenneth More. They bet £100 on it.

First one gets the advantage, then the other. Ambrose sabotages Alan’s car. Alan is arrested for speeding. They call the race off because it is getting out of hand. Then it is on again. Finally the winning point on Westminster Bridge is only a few hundred yards away. Alan is in the lead and about to win when he has to stop at a red traffic light. An elderly gentleman comes up to him and exclaims what a wonderful car Alan has. He talks about the time he used to have one himself. The traffic lights turn green. Alan is desperate to get away and win the race. He struggles with his conscience … and his conscience wins. He politely hears the gentleman out and invites him to come to have a spin in the car when he likes. Ambrose swoops past. The lights turn red again. Alan has let victory slip his grasp – at least, so it seems. The ethos of the film is that being a good, kind person is more important than winning.

The red card index

Much of the above is open to argument. It is possible, for example, to find 1950s British films in which people behave very badly – although in such cases the bad behaviour is generally treated as such by the director. What about some objective measure – one that has been recorded year after year for a century or more? There are not many things like that. Fortunately there is one, at least: in football.

Bad behaviour in football has always taken place. A match between Scotland and Austria in 1951 got so nasty that the journalist who saw it said it came to resemble a battlefield. But has the amount of bad behaviour on the football field always stayed about the same? We can try to get an idea by looking at the number of people sent off each season.

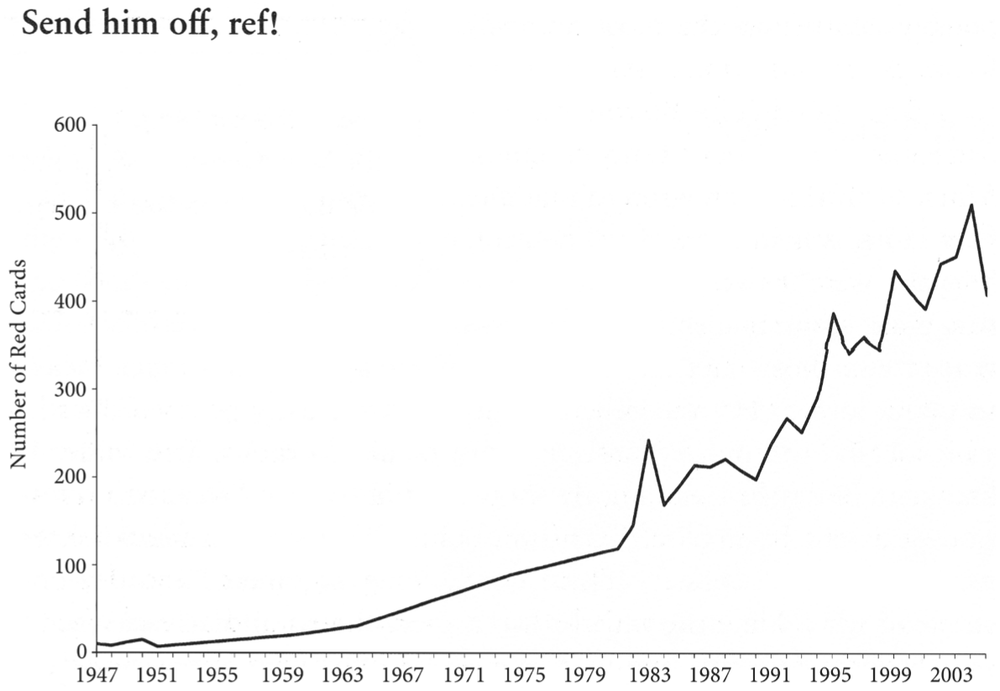

In 1946/7 – the first season after the war – ten men were sent off in league football. The next year was a bit better. There were eight. The next season was worse – fifteen got their marching orders. Jumping forward to 1954/5, seven players were dismissed. The figures for every year are not readily available, but Tony Brown, the sendings-off expert, estimates that from the 1891/2 season up to 1961/2, there was a ‘steady state’ of about a dozen sendings-off per season.

It was then, in the early 1960s, that things distinctly began to change. The trajectory of the figures is like the profile of a volcano – a gentle incline at first, gradually becoming steeper. By 1979/80, the number of sendings-off had reached 115. Over a mere two decades, the number of sendings-off had jumped eight-fold.

The football authorities tried to clamp down on the growing violence and cheating in 1982. Referees were instructed to enforce the laws more rigorously. It is important to understand that the tougher regime was a response to the growing lawlessness, not some strange, arbitrary decision that football should not be physical any more. It was hoped that a sudden assertion of authority would bring order back to the game.

Sendings-off in first-class football matches: English, Welsh and Scottish league games and cup competitions.* The figures from 1959/60 to 1973/4 are less reliable, being based on samples. Source: Tony Brown.**

It didn’t work. The sendings-off rose higher still. In 1990/91, they reached 200 in a single season for the first time – nearly double the level of eleven years before. They quickly rose higher again, passing three hundred in 1994/5. In the latest year for which figures are available, the total number of sendings-off was 451 – that makes a total rise of 3,658 per cent compared to the years between 1891/2 and 1961/2.

Some football fans may still want to believe that the rise has all been due to the referees being more pernickety. But surely the enormous scale of the rise and its persistence under various footballing authorities will persuade most people. We might ask the opinion of those who were there at the time and professionally involved.

Sir Tom Finney was a star of the post-war years, a winger playing for Preston and England. He later recalled:

Throughout my playing career with Preston North End, I can only recall two sendings-off. This was not because referees were more lenient but because standards of conduct were much higher. Yes, we played hard, but we were also fair … To be sent off was a cause for shame. You had let your team, the manager and the spectators down.12

It is noticeable that he thought shame was attached to being sent off. There is not so much now.

Mervyn Griffiths was the referee of the ‘Matthews final’– the celebrated FA Cup final in 1953 in which Stanley Matthews, the most admired forward of his time, sensationally turned a 3–1 deficit for Bolton into a 4–3 victory in the final twenty minutes. When Griffiths later wrote about the game as it was in those days, he said, ‘Players were better behaved. There was more sportsmanship than gamesmanship in those days and it showed in so many ways.’14 He remembered a match in the early post-war days in which a Millwall player questioned one of his decisions. The Millwall manager, Benny Fenton, angrily shouted at his player, ‘You don’t question decisions by that ref!’ Griffiths said, ‘Players had a much better spirit towards referees … There were no big arguments and demonstrations when I had the whistle. It makes my hair stand on end when I see players today surrounding a referee, hurling abuse and even laying hands on him. Such a thing was unheard of.’

John Charles was a big man who played for Wales. Griffiths remarked of him, ‘As big as he was, he never used his weight unfairly’. So those who knew the game up close in the 1950s and 1960s certainly think there has been a big change.

Never mind the violence, feel the success

It is revealing how the authorities and others reacted to bad behaviour.

Willie Woodburn, playing for Scotland, pokes the ball away from England’s Tommy Lawton. After five serious fouls in his career, Woodburn was banned for life in 1954.

Another leading player of the early post-war years was Willie Woodburn, a Scottish international. He appeared before the Scottish FA Referees Committee four times. Then, on 28 August 1954, he played for Rangers against Stirling Albion and fouled someone again – the method is not described.15 He went before the Referees Committee for a fifth time. The committee suspended him from the game sine die – that is, indefinitely. His footballing career was finished. Over. He was asked to comment but only said ‘It is too bad to talk about’. Bad behaviour was punished severely.

In more recent times, there was another player with a bad record. Vinnie Jones was – and still is – a big man, like John Charles. But he was not admired, in his relatively recent footballing career, for using his size fairly – as Charles had been.

Despite being sent off twelve times Vinnie Jones was never banned. His reputation for violence helped him become a celebrity.

Jones was sent off twelve times in his career. He was not called in, though, after five major infringements, like Woodburn, and told that he would never play professional football again. He was never permanently banned. Instead of his career being finished, it thrived. A video was made of his most unpleasant attacks on other players. He was invited onto television chat shows like ‘Mrs Merton’. He was used as a model by Charles Tyrwhitt, a mail-order shirt-seller. He became well enough known to be cast as a tough-guy villain in the film Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels. What would have earned him disgrace in the late 1940s and 1950s won him fame and fortune.

In 1998, Jones was tried for assault.16 He had called on a neighbour, Mr Timothy Gear, late at night. He wanted to know why Mr Gear had removed a stile near his smallholding. According to Mr Gear’s evidence, Jones banged on the door of his mobile home and smashed a window. Mr Gear claimed that when he opened the door, Jones bit him on top of the head, punched, kicked and then stamped on him. Jones gave a different version of events. But the magistrates found Jones guilty of assault causing actual bodily harm and criminal damage. Jones thus became a convicted criminal. How did the press cover the incident? It concentrated on how the months since his assault on his neighbour had been ‘terrible’ for Jones.17 His feelings of stress were given more prominence than his violent, criminal behaviour. Four years later, Vinnie Jones was even made ‘the new face of Burton’, the men’s clothes store, for the company’s centenary year.18 The marketing director said Jones was chosen to launch the campaign because ‘he is a gutsy, modern British character … he represents the modern version of a British icon’.

In June 2003, the ‘icon’ flew with Virgin Atlantic to Tokyo in Upper Class.19 He left his seat to drink at the Airbus bar and began talking to three men and a woman. The woman felt that Jones had become boorish and returned to her seat. Jones went over to her where she was sitting. He put a plate of food on her lap and told her to go to the bar. One of the men went to Jones and told him to stop pestering the woman. Jones slapped the man around the face and pushed his head into a window of the plane. He was aggressive and abusive. At one point, when air crew were trying to pacify him, he screamed at them, ‘Go and pour the f****** coffee like you are paid to. I can get you murdered. I can get the whole crew murdered for £3,000.’ He was later convicted of assault and threatening behaviour.20

Vinnie Jones might be regarded as a one-off. Actually – in football, at least – he was more like a pathfinder. What seemed exceptional in his early days has now become mainstream.

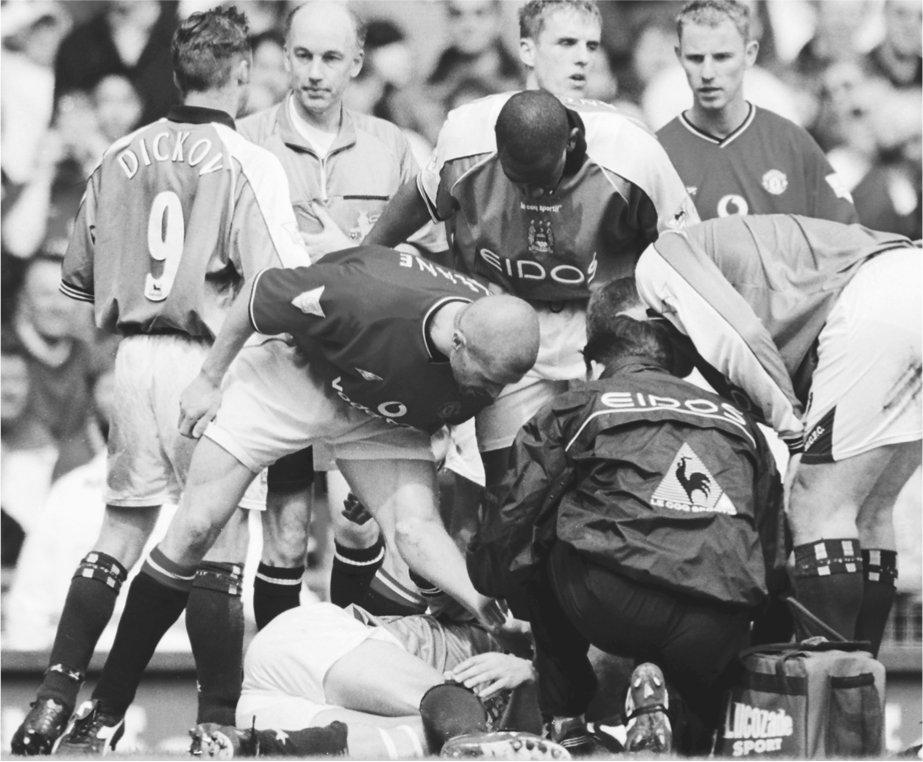

Roy Keane shouts abuse at Alfie Haaland after deliberately hurting him in a Manchester United versus Manchester City match, in April 2001. ‘I f****** hit him hard,’ he wrote later.

Acceptance of malicious violence has reached the heart of the game. Roy Keane was captain of Manchester United in 2001 when United – the most successful British team at the time – was playing Manchester City. He had a grudge against one of the City players, Alfie Haaland. Keane set out to hurt him. According to his own autobiography, ‘I f****** hit him hard. Take that you c***.’ The attack caused knee ligament damage. Following it, Haaland only played four substitute appearances in the next sixteen months.21

In August 2002, Keane was sent off for the tenth time in his career. What did his manager, Sir Alex Ferguson, say about his repeated acts of violence? Did he say, as Benny Fenton, the Millwall manager, had shouted to his player ‘Don’t question decisions by that ref!’? At an annual general meeting in November 2002, Ferguson said, ‘There are moments when he gets those flashes of temper but that is because he is a winner.’22 The ethic Ferguson revealed was simple: it does not matter if a player cheats and injures people as long as he wins games. It seems a long way from Genevieve.

The unreported crime wave

Is there another kind of behaviour which provides a fairly objective measure of behaviour, year after year? Yes. And it happens to concern one of the most crucial kinds of human behaviour: crime.

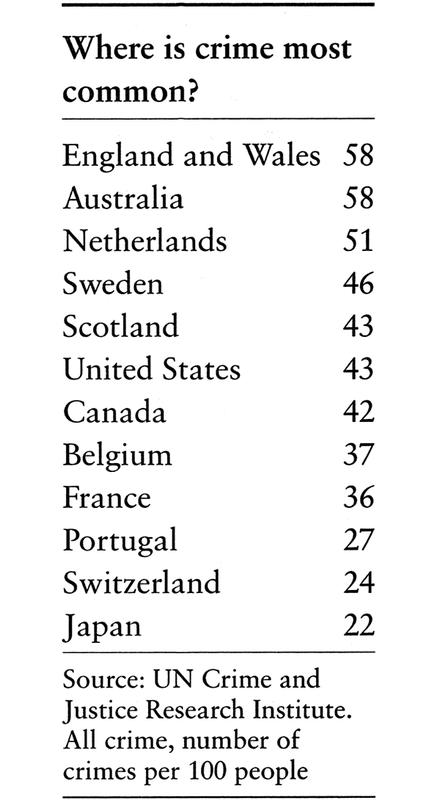

The figures are even more dramatic than those for sendings-off in football. In 1898 there were 4,221 violent crimes in England and Wales. Just over a century later, in 1998/9, there were 331,843. The number of violent crimes has increased seventy-seven times over. Of course the population has risen but even after adjusting the figures for that still shows a 47-fold rise in violent crime.24 The rise began in the 1920s and 1930s and continued remorselessly thereafter.

Once again, some will argue that the figures give a false impression.25 It is said that reporting of crime has increased. It is far from clear that this is true, let alone to the extent which would explain away such a massive change. In fact the very opposite may be true. According to Professor Jose Harris:

A very high proportion of Edwardian convicts were in prison for offences that would have been much more lightly treated or wholly disregarded by law enforcers in the late twentieth century. In 1912–13, for example, one quarter of males aged sixteen to twenty-one who were imprisoned in the metropolitan area of London were serving seven-day sentences for offences which included drunkenness, ‘playing games in the street’, riding a bicycle without lights, gaming, obscene language and sleeping rough. If late twentieth century standards of policing and sentencing had been applied in Edwardian Britain, the prisons would have been virtually empty; conversely, if Edwardian standards were applied in the 1990s then most of the youth of Britain would be in gaol.26

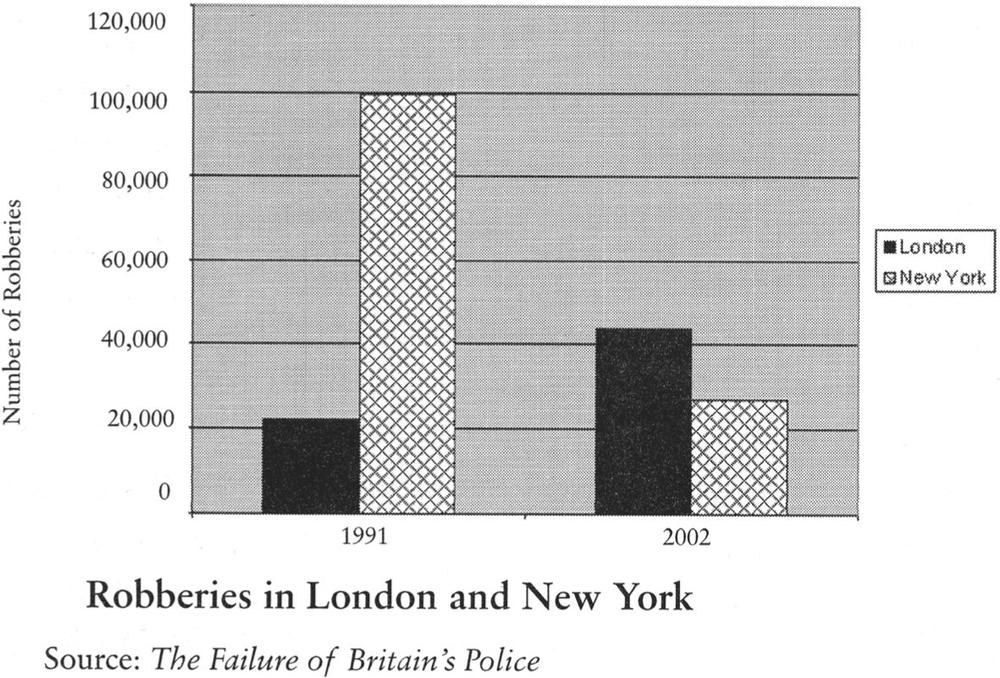

Further evidence of the massive increase in crime comes from international comparisons. The United Nations ignored official national figures and asked random samples of 2,000 people in different countries about their experiences.27 England and Wales had the highest crime rate of all – equal to that of Australia but well above that of the United States, France, Switzerland and Japan.

In the crime epidemic, children have been hit particularly hard – often literally. The figures have soared even over quite short periods. Prosecutions for cruelty to or neglect of children rose from 228 in 1988 to 839 in 1999.28 Abuse of children has increased dramatically too. ‘Gross indecency with a child’ was three times more frequent in 2000 than in 1983.29

Just one crime may bring home some of the reality behind the figures. A ten-year-old boy was brought by his loving mother from Nigeria to Britain in 2000. The family had saved £5,000 over two years to have his sister treated for severe epilepsy at King’s College Hospital. The mother had lived in Britain before and was able to get a flat in Peckham, south London. The boy attended Oliver Goldsmith primary school while his sister was being treated. He was a bright, keen boy. But after only a few months in London, his mother discovered that boys at school were swearing at him and calling him names. The mother told his teachers of the taunts and abuse but, according to her, they did not take her seriously.

After four months, one Friday, he told his mother that some boys had beaten him at school. His mother asked, ‘Did you fight with them?’ He replied, ‘No mummy, I did not fight with them.’ The next Monday, he walked to the library after school for an extra computer class. He left the library at 4.25 p.m. to go home. When he was in Blakes Road, he was stabbed. He started bleeding heavily. He staggered one hundred yards before collapsing and dying. His was one of the small minority crimes which, for a variety of reasons, made it into the newspapers and – even more difficult – onto national television. The name of the boy was Damilola Taylor.31

‘I can’t believe how much Britain has changed since we left.’32

Mrs Gloria Taylor, mother of Damilola, who left Britain in the early 1980s and returned in 2000

The reason for choosing the death of Damilola Taylor out of all the thousands of crimes in recent years is that it resulted in newspaper coverage of a sort rarely seen. Journalists left their comfortable offices and went to Peckham. Their stories often had two bylines – the journalists were sent in pairs for safety. One of these pairs talked to two black sisters who were discussing teenagers on the estate – children really – who regularly threatened them. One explained, ‘They smashed my car with an iron bar. That’s why I park two miles away’.

At that moment, a boy, estimated by the reporters to be about twelve, loped past, his face and head hidden in the hood of his sweatshirt. One of the women shrieked, ‘Him, ask him, he’s one of them!’ This terrified her sister who clamped her hand over her mouth, whispering, ‘Shut up, shut up’. The two women hurried away, frightened of what the twelve-year-old boy – or perhaps his fellow gang members – might do to them. This boy – a child – swaggered over to the two journalists. He said his mother had told him to tell journalists to ‘f*** off’. He slowly pulled down his hood and stared. The journalists interpreted this to mean, ‘You walk away, not me. This is my patch.’

What is it like to live in an area like that? Two women were interviewed about the daily fear of muggings and stabbings, the no-go areas, the syringes littering the stairwells, the drunken parties and blaring music thudding through their walls from dusk to dawn.33 They said gangs of kids would roam the streets searching for other kids to rob or mug. Even in daylight you weren’t safe. One old lady was attacked on her way to buy a newspaper. When they found out she had only 40p on her, they ripped off her wedding ring and knocked her to the ground.

Connie opened her door reluctantly even to journalists, keeping closed an outer steel mesh which protected her.35 ‘I talk to nobody,’ she said. ‘That way I don’t get involved. I know nothing. No one who has any sense round here knows nothing’. She had three menacing Alsatian dogs behind her. The dogs snarled. She slammed the door. What horrifying fear and nastiness can Connie have lived through to end up behaving this way?

Britain has been through a crime epidemic. It reflects on the changed character of a significant minority of people. And for every one actually convicted of a crime, there are surely many others who have been aggressive and anti-social.

Move over, Keats, it’s Johnny Rotten

What else has changed? What about the intellectual and cultural life of British people?

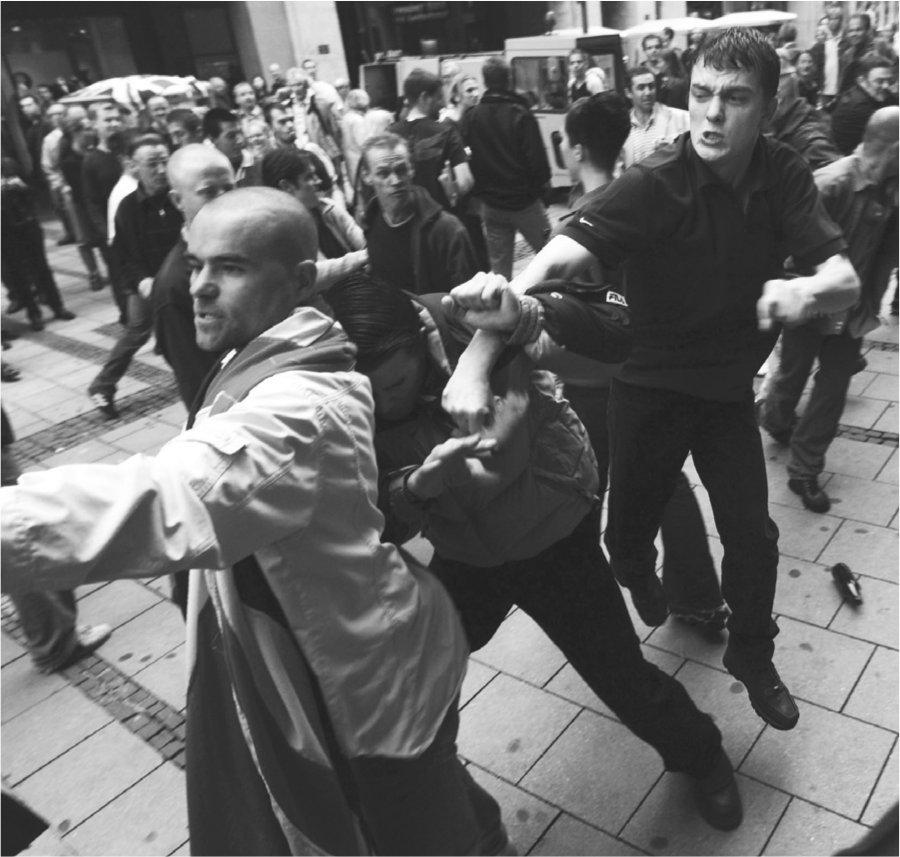

English and German football fans clashing in Munich in 2001. The frequency of violent crime has increased 47 times since 1898.

In 2002, a cable television channel conducted a survey in which people were asked what they considered the most significant event in British history over the previous hundred years out of a choice of ten.37 What event did the British choose? The most popular choice – selected by nearly a quarter of those questioned – was the death of Princess Diana. That was, of course, a tragic event. But was it an historical event to compare with the start of the Second World War or the end of the First, both of which were ranked lower?

In another survey, secondary-school pupils were asked whom the English were fighting in the Battle of Hastings.38 One in three did not know. They were asked when the First World War took place. Two out of three did not know. Nearly a quarter could not even place it in the right century. Half had no idea that Oliver Cromwell was a key figure in the English Civil War.

The BBC asked a very large sample of people – thirty-three thousand – to draw up a list of a hundred people who could be candidates for the title of the ‘Greatest Briton’ of all time. They did not select John Milton, William Wordsworth, John Keats, Samuel Johnson or Rudyard Kipling for the top 100.39 John Locke, Thomas Hobbes and David Hume – some of Britain’s most celebrated philosophers – did not make it either. Nor did Britain’s most famous painters, John Constable and William Turner. Was this because the competition was so strong? Well, the hundred did include people you might expect such as William Shakespeare and Winston Churchill. But also among their number were Cliff Richard, David Beckham, radio presenter John Peel, Julie Andrews, Michael Crawford and Johnny Rotten. Each of these individuals certainly has had their achievements. But did they truly deserve to push out people of the stature of Kipling and Constable? The easiest explanation is that most British people nowadays know little or nothing about many of the greatest British people to have lived.

How well do people follow current events? Whitaker’s Almanack questioned over a thousand people, asking them to name members of the British Cabinet.40 More than two out of five could not name one. Slightly under a quarter were able to name the Chancellor of the Exchequer. In contrast, 63 per cent could name a character from the television soap opera EastEnders. A remarkable 46 per cent could name five of the characters. EastEnders personalities are better known than members of the government – by far.

Children’s language skills are getting worse, according to Alan Wells, director of the Basic Skills Agency. He revealed that an estimated 50 per cent of children in Wales were not ready to start primary school at five because of their limited ability to talk.42

University academics were asked how students coming from schools compared with those in the past.43 An overwhelming 70 per cent said they were less well prepared. Three-quarters said they had been forced to adapt their teaching techniques to the increasingly ‘diverse’ mix of students – ‘diverse’ being the euphemistic way of saying that they included seriously weak students.

We are beginning to build up a picture of intellectual and cultural deterioration (investigated more fully in the education chapter).

A Faustian pact?

It is not going too far to say that there seems to have been a revolution in the culture and character of the British people in the last sixty years. The evidence is overwhelming that they are less polite and more violent. We live in a far more crime-ridden society. Though educated for longer, the effectiveness of the education appears poor. We will see evidence in later chapters of other kinds of deterioration in healthcare, parenting, unemployment and benefits dependency. And though we have indeed enjoyed a rise in wealth, we will see it has been less dramatic than that in various countries which were once far poorer than ourselves. Taxes, of course, are vastly higher than a century ago.

SPOT THE DIFFERENCE

Cartoon by Ron McTrusty, Evening Standard, 15 August 2002. This was at the time of the controversy over Roy Keane’s fouls and a court case about a fight at a London nightclub involving other prominent footballers.

A picture emerges of a country that has become brutish and even degenerate compared to what it was. It is as if it had made a Faustian pact: greater wealth in exchange for moral decline. But there was no pact. And no need for the moral decline. A country which had a remarkable history and character appears to have just thrown it away.

This happy breed?

There could be a kind of defence. Are the British happy? If, at least, we are happier, perhaps we need not care about the rest. It is an idea that can be tested.

No single study covers the whole period but two studies over shorter, overlapping time-frames provide telling evidence. Psychologist Glyn Lewis sought to compare the mental state of people in 1985 to a similar sample in 1977. Even over this relatively short period he discovered a big change. He looked at the proportion suffering from ‘psychiatric morbidity’ – that is psychiatric illness or distress.45 The sort of symptoms included were panic attacks, phobias and depression. In the earlier sample, 22 per cent were suffering mentally in one way or another. In the later sample, the percentage had increased to 31 per cent – almost one-third of the population.

Another study examined the changing state of British minds a little later. It was based on two major, well-known surveys: one of children born in a single week in 1958 and another of children born in 1970. Both groups were looked at when they reached the age of twenty-six – i.e. in 1984 and 1996 respectively. The proportion of those born in the 1950s who said they were depressed was 7 per cent. The second group, a dozen years later, was richer and had been educated, on average, for longer. Were they happier? Not at all. The proportion reporting that they were depressed had doubled, to 14 per cent.

Why should the British be less happy? They are wealthier and have had lengthier educations. What is causing the unhappiness?

Oliver James, the psychologist and author, suggests, among other things, ‘We are increasingly likely to live alone, the care of children has become increasingly erratic and the elderly are left to fend for themselves in unnaturally lonely, estranged circumstances.’47 He mentions, too, the ‘divorce epidemic’ which damages first the adults who become far more likely to suffer depression, and then the children. Among women, rates of smoking and drinking – ‘signs of distress’ – indicate their unhappiness is rocketing.

James’s remarks about drinking are supported by a Data-monitor survey from 2003, which found that young British women drink more alcohol than those of any of the other European countries studied. They drink more than three times as much as young Italian women.48

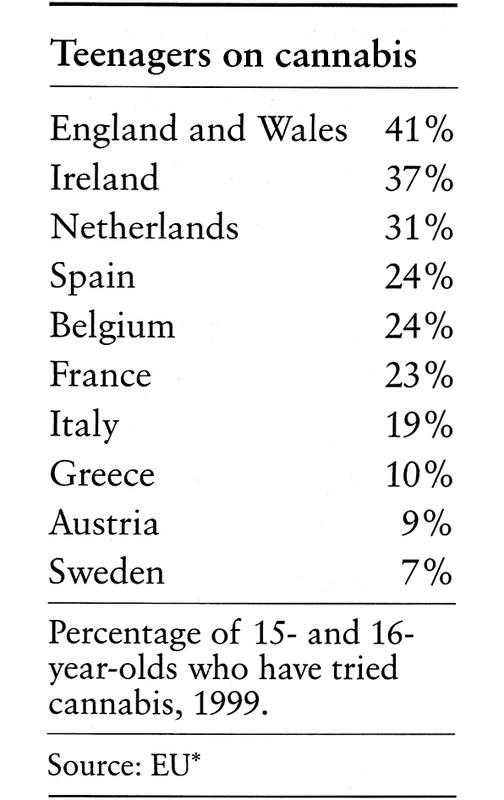

Drug-taking, like heavy drinking, may well be a symptom of ‘psychological distress’. The European Union conducted a study of fifteen- and sixteen-year-olds to see how many had tried cannabis. In England and Wales more than four out of ten had tried it – again, a higher figure than for any other country in the European Union.

The great rise in wealth over the past sixty years has been a marvellous thing, bringing many benefits, but the story has been marred by an equally astonishing decline in the way British people are. And we are not even happier. Quite the reverse. We have indeed suffered a fall from grace. The vital question remains, why? And can it really be something to do with the welfare state?

Notes

1 Halsey, A. H. and Webb, Josephine (eds), Twentieth Century British Social Trends (Macmillan, Basingstoke, 2000), p. 632.

2 Published by Cresset Press, London, 1955. Extract quoted in Davies, Christie, ‘Crime, Bureaucracy and Equality’, Policy Review 23, Winter 1983.

3 ‘The English People’ in The Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters of George Orwell, ed. Sonia Orwell and Ian Angus, (Secker and Warburg, London, 1968), vol. 3, quoted in Norman Dennis, Rising Crime and the Dismembered Family: How Conformist Intellectuals Have Campaigned against Common Sense (Institute of Economic Affairs, London, 1993).

4 Soliloquies in England (Constable, London, 1922), pp 30, 32, 53, 54.

5 Himmelfarb, Gertrude, The De-moralization of Society: From Victorian Virtues to Modern Values (Knopf, New York, 1995).

6 Ibid.

7 Reissued by Egmont (2000), p. 58.

8 Daily Mail, 22 September 2003.

9 Daily Telegraph, 5 July 1996.

10 Daily Mail, 17 July 2003.

11 Col. Maurice Willoughby, letter to the Daily Telegraph, 1 April 2000.

12 Daily Mail, 18 February 2000.

13 Ibid.

14 Daily Express, 6 January 1972.

15 Cutting dated 15 September 1954, newspaper not identified, supplied by Hayters.

16 BBC News online, 2 June 1998.

17 Daily Telegraph, 3 July 1998.

18 Daily Telegraph, 24 September 2002.

19 Daily Mail, 2 June 2003.

20 Daily Telegraph, 13 December 2003. Much of this paragraph is derived from this court report.

21 Ian Wooldridge, Daily Mail, 14 August 2002.

22 Daily Telegraph, 16 November 2002.

23 Jimmy Greaves, Sun, 2 September 2002.

24 I have taken the population of thirty-two million shown for 1901 on page 72 of Social Trends 30 (Office for National Statistics, 2000) and counted the population of fifty-two million for 1996/97 from the same source. The years are slightly but not significantly different from the years of the crime figures.

25 Some people might be surprised that, if crime is so much more widespread, they do not experience it themselves. But crime levels vary enormously according to where one lives. According to government figures, for every crime experienced by ‘wealthy achievers’ in the suburbs, nearly three are endured by residents of the poorest council estates. ‘Affluent greys’ experience less than one-seventh of the crime level of such estates. The relatively affluent – which includes the vast majority of media people, politicians and other opinion-formers – do not experience crime as it is suffered by millions of other people. The people who suffer most from crime are the poor. The wealthy are insulated, on the whole, from what is going on.

26 Harris, Jose, Private Lives, Public Spirit: A Social History of Britain 1870–1914 (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1993), quoted in Peter Hitchens, A Brief History of Crime (Atlantic, London, 2003).

27 Daily Mail, 15 July 2002.

28 Kilsby, Peter, Aspects of Crime: Children as Victims 1999, Crime and Criminal Justice Unit, Home Office, July 2001. http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk/rds/pdfs/aspects-children.pdf

29 In case some may think this was a statistical aberration due, perhaps, to changes in the amount of abuse recorded by the police, the NSPCC recorded more than a doubling in the rate of physical abuse of children aged 0–14 between 1979 and 1989 (Robert Whelan, Broken Homes and Battered Children: A Study of the Relationship between Child Abuse and Family Type, Family Education Trust, London, 1994).

30 Dennis, Norman et al., The Failure of Britain’s Police: London and New York Compared (Civitas, London, 2003).

31 Guardian Unlimited, 4 December 2000, 30 November 2000 and 29 November 2000.

32 Guardian Unlimited, 30 November 2000.

33 Daily Mail, 20 May 2002, interview by Helen Weathers.

34 Financial Times, 20 May 2002.

35 Sunday Telegraph, 28 April 2002.

36 Calculation made by Donal Shanahan, a surgeon at Homerton Hospital, quoted in the Sunday Telegraph, 14 April 2002.

37 Daily Mail, 23 August 2002 and Guardian, 24 August 2002.

38 Survey by Osprey, a book publisher, Daily Mail, 18 January 2001.

39 Stephen Glover, Daily Mail, 22 October 2002.

40 BBC Online, 22 October 2002 and Daily Mail, 10 October 2002.

41 Daily Express, 17 June 1997.

42 Daily Mail, 9 January 2003.

43 Times Higher Education Supplement, reporting a poll conducted for it by ICM, 23 May 2003.

44 Times Educational Supplement, 17 January 2003.

45 James, Oliver, Britain on the Couch: Why Are We Unhappier Compared with 1950 despite Being Richer (Century, London, 1997), p. 345.

46 Ibid.

47 Ibid., p. 20.

48 Daily Mail, 17 October 2003. UK: 203 litres, Germany: 189, Netherlands: 107, Sweden: 82, Spain: 72, France: 70, Italy: 59, other Europe: 93, total Europe: 104.