It is 1961 and Walt Disney is bringing out 101 Dalmatians. Audrey Hepburn is appearing in her little black dress and large dark glasses in Breakfast at Tiffany’s. Elvis has plenty of number one hits, as usual, including Wooden Heart. Harold Macmillan is the suave, patrician Prime Minister and urbane ‘Rab’ Butler, the Home Secretary, is his most prominent cabinet minister. John Profumo, who will later be disgraced because of his affair with Christine Keeler, is Minister of War. The Conservatives have been in power for a decade and are, perhaps, looking rather tired.

The Conservative Party has long since accepted the increase of the scope of the welfare state brought about by Labour after the war. The two political parties are so close in their views that people talk of ‘Butskellism’ – a political philosophy shared by both Butler and Hugh Gaitskell, the Labour leader. Butler himself introduced one of the biggest expansions of the welfare state in his Education Act and Macmillan established some of his reputation by building plenty of council housing when housing minister. In 1961, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Selwyn Lloyd, brings in wage and salary controls. That is a measure of how much the Conservatives agree with Labour that big government is good government.

In this same year of 1961, six thousand miles away in Hong Kong, a tall, plump, balding, bespectacled civil servant has been promoted. John Cowperthwaite comes from a family prosperous enough to send him to Merchiston Castle, the leading independent boys’ school in Edinburgh. The school has a grand main building of stone with a pillared portico resembling the front of a Greek temple. It boasts that it ‘promotes the Scottish values of hard work, integrity and good manners’. Cowperthwaite is Scottish through and through. He is not Scottish like Rob Roy or Billy Connolly though. But he is recognisably a Scot coming from a recognisable Scottish tradition. He knows Hong Kong well, having lived there since 1946, after the Japanese occupation ceased at the end of the Second World War.

Post-war Hong Kong – poor, ravaged and flooded with refugees.

What is Hong Kong? An oddity of history. A little bit of the Empire that has not yet been handed over to someone else. It is a strange place for a British outpost. Across the harbour, beyond the territories leased by Britain, is the vastness of China, now run by the Communists. Chairman Mao Tse-tung dominates the country with fear. His ‘little red book’ is read by all who understand what is good for themselves and their families.

Cowperthwaite has seen the effect of Chinese communist rule all around Hong Kong. The small colony has been flooded with refugees, coming with no more than they can carry, in their hundreds of thousands. The population has soared – from six hundred thousand or less in 1945 to 3,200,000. The refugees have built shanty towns or live in boats on the water or in cramped government-provided units.

Cowperthwaite is forty-six years old and not famous at all. Few people outside Hong Kong have heard of him. He has been promoted to an important job in this outpost, but he has not become the top man, the Governor or even the official number two. He has been made Financial Secretary, number three in the official hierarchy. He goes to the government home provided for him, which is grand by Hong Kong standards. But he lives modestly during the next decade while he lives there, doing little to improve it.

The Hong Kong press finds that he is not exactly media-friendly. He doesn’t court newspaper attention, willingly give interviews, grin or show off his family. His manner is dry almost to the point of rudeness. One day he arrives back from meetings in London and climbs down the steps from his BOAC plane to be greeted by some local journalists.433

‘What did you discuss at the meetings in London?’ one asks.

‘I really don’t think that is the right sort of question to ask me.’

‘Well, Financial Secretary, what should we be asking you?’

‘It is not for me to tell you how to do your jobs.’

End of press conference.

It is a classic Cowperthwaite story. Perhaps it is not wholly accurate but it certainly conjures up the man.434 He can be cussed and infuriating. He is only concerned to get on with his job and his duty. Over the next decade, he will frustrate the wishes of many more people than just that gaggle of reporters.

As Financial Secretary, he is urged to allow mortgage interest to be charged against salaries tax, as in Britain. He says ‘no’. It would only benefit those with substantial incomes. He is urged to extend government housing to the middle class. He refuses again. He says that all public housing involves subsidy. The bigger the housing – which the middle classes would expect – the bigger the subsidy. It would be wrong to subsidise the middle classes, who should pay for their own housing.

Some businessmen want the government to build a tunnel across Hong Kong harbour. Cowperthwaite declines once more. He says that if they think the project would be so beneficial, they should build it themselves. (In due course, they do.) He is urged to tax people on all their incomes, as in Britain, instead of only on their salaries. Yet again, he says ‘no’. Tax on all income is inevitably ‘inquisitorial’, he says, and would discourage investment and enterprise. Surely he should at least collect statistics on Hong Kong’s balance of payments, he is asked. ‘No,’ he replies. ‘If I let them compute those statistics, they’ll want to use them for planning.’

John Cowperthwaite, a little-known, tall, plump, balding, bespectacled civil servant.

As time passes, it gradually becomes clear which sort of Scot he is. He is from the Adam Smith tradition, believing that entrepreneurial activity does good. He is also from the tradition of being careful with money. He is careful with not merely his own money but, more importantly, that of taxpayers. He has integrity – as demanded by his old school. (Perhaps his old school could also take credit for the fact that his knowledge was so extensive that he could playfully refer to the tax policies of Vespasian, the Roman emperor, in one of his budget speeches.) He resists the temptation to spend public money to ‘make his mark’ or satisfy personal vanity. He is ‘true to the ethics of Scottish Protestantism’.435

Cowperthwaite became the civil servant who liked to say ‘no’. Although never in the top job, he dominated policy in Hong Kong. He held the line as best he could against all sorts of spending proposals. His bosses in London – Harold Macmillan and then Harold Wilson – both greatly expanded the welfare state. But Cowperthwaite held out against similar changes in Hong Kong. He did not always succeed. At the end of his period of office, he had to announce free primary education. He revealed what he disliked about it, saying, ‘I hope that we shall be able to do something to limit free primary education … to the schools which do not cater for the affluent.’ Towards the end of his time in Hong Kong, nearly half the children still went to private schools and most who went to government-subsidised schools attended ones which were privately run.

Cowperthwaite’s most important reason for playing Scrooge was to keep down taxes. He thought high taxes slowed economic growth. Low taxes would eventually produce more revenue than higher ones, he argued, because of the growth they would encourage. Fast growth would also benefit the poor by boosting demand for labour and pushing up wages. Fast growth produced ‘a rapid and substantial redistribution of income’. Successful capitalism benefited the poor.

Because he kept to his creed, at the end of his time in Hong Kong, the standard rate of tax was 15 per cent. Even the richest were not asked for more than 15 per cent of their gross income. Profits tax was similarly low. There was no tax at all on dividends or foreign income. The poor were not liable for salaries tax at all.

Cowperthwaite was not the only Hong Kong official to believe in low spending, but he was the most influential. His legacy has gradually been eroded. But even now when China has resumed control, the top salary tax rate in Hong Kong is still only 15 per cent and as recently as 1997, a majority of the population was not liable to salary tax. The poor in Hong Kong are simply not taxed.

Back in Britain, meanwhile, a very different line was being followed.

Government spending seriously got going after Harold Wilson became Prime Minister in 1964.

Government spending seriously got going when Harold Wilson became Prime Minister in 1964. Charges on NHS prescriptions were abolished in 1965.436 New, extra salary-related benefits were paid to the unemployed or ill. Means-tested ‘supplementary benefits’ were introduced and paid as of right to those with low incomes. It was decided to raise the school-leaving age to sixteen.437 Higher education was boosted, with the numbers of students almost doubling in a decade.438 Government spending as a proportion of national income grew inexorably – from 36.5 per cent of national output in 1964 to 40.9 per cent in 1970.439 Inevitably taxes had to rise, too.

So what was the effect of higher taxes? Who was hit and how? The politicians found that one of the politically easiest ways to raise tax was to let inflation do the job. Inflation and real wage increases raised incomes. So if the government did not increase tax-free personal allowances by a similar amount, then more and more people would be automatically brought into the tax net. This way of raising tax went unnoticed by most newspapers and other commentators. It was controversy-free. But who was caught in the ever more capacious net? The rich, of course, were already in it. The net was being widened to catch the less well-off and then the poor.

In 1961 a married couple with two young children paid income tax if they brought in three-quarters of average earnings.440 Ten years later, in 1971, couples in Britain with a mere 58 per cent of average earnings were paying income tax (see table on p. 271).441 In Hong Kong itself, such a couple would pay zero income tax.

Eventually Wilson lost office to the Conservatives in 1970 but they did little to cut back spending. Then Wilson returned in 1974 and immediately increased unemployment benefits, among other things. His new administration took government expenditure to unprecedented heights, reaching 49 per cent of national income in 1975 (compared with only 34 per cent in 1950 and 12 per cent in 1913). Inevitably, taxes rose too. Excise duty on beer was increased by a third.442 Relatively poor married couples on only half average earnings with two children started having to pay tax. The standard rate they had to pay reached 35 per cent – a world away from Hong Kong’s 15 per cent. The top rate of tax reached 98 per cent under the Labour administration, including a 15 per cent surcharge on dividends.

In 1979, Margaret Thatcher came to power. She is thought by some to have taken a hatchet to public spending. But she got nowhere near reducing it to Hong Kong levels – normally about 17 per cent of the colony’s income. The welfare state – particularly social security and the NHS – kept growing during the Thatcher years as if it had a life of its own, largely thwarting her ambitions to reduce spending and thus taxes. In 1986, in the middle of her time as Prime Minister, British government spending was still over two-fifths of national income.443

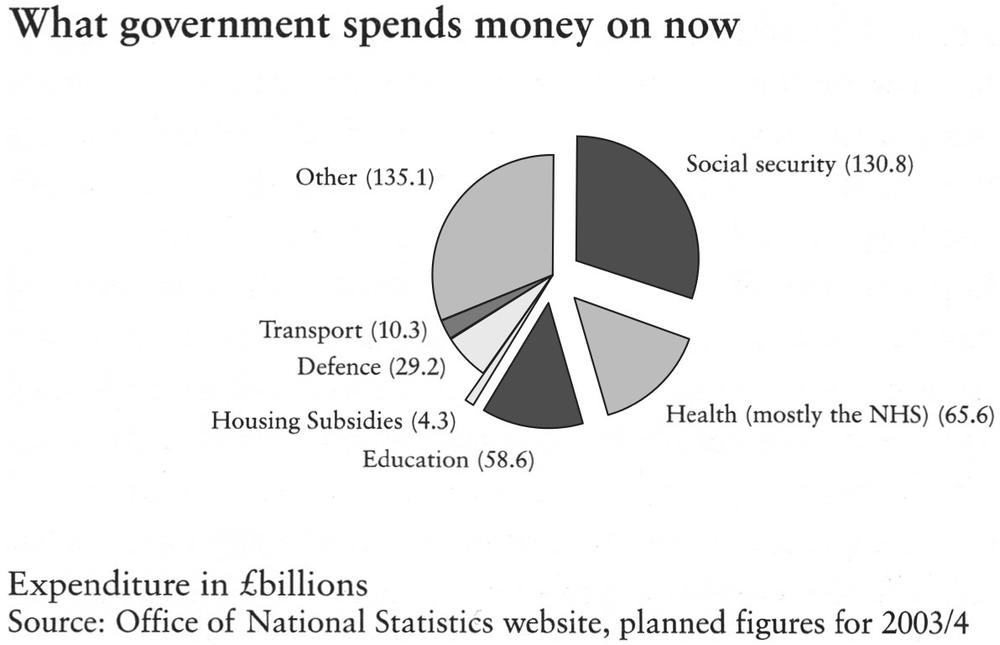

We might pause here to note that the huge and hard-to-control cost of the welfare state was not expected by its creators. Going back to the days of Attlee’s post-war government, the cost was relatively modest. The bill for defence was more than that for housing, local government, the NHS, national insurance, national assistance and state pensions all put together. Now the cost of social security alone is four times that of defence. Government figures at present seem designed to obscure, rather than to reveal the current overall cost of the welfare state. Nevertheless a minimum of £258.9 billion of welfare state spending can be identified in the 2003/4 Budget, accounting for 60 per cent of all government spending (excluding debt financing). The grand total of welfare state spending, including expenditure tucked away in such categories as ‘Scotland’, ‘Wales’ and ‘Deputy Prime Minister’s Office’, is probably at least two-thirds of all government spending and it therefore accounts for about 30 per cent of all national output.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, government spending accounted for a tenth of economic activity. At the end, it accounted for 40 per cent of it (and that despite the reduction in defence spending). The welfare state is the reason.

So there is a big contrast in the policies followed by Britain and Hong Kong. Attlee, Macmillan, Wilson and others created a country with a highly developed welfare state and consequent heavy taxation. Meanwhile, the austere, little-known Scot, Sir John Cowperthwaite, and others in Hong Kong followed the opposite course of a minimal welfare state and low taxes. The effectiveness of Britain’s state welfare is examined in the other chapters. Here, we consider how tax – necessitated by a big welfare state – affected economic growth.

*

Britain in 1945 was one of the most advanced countries in the world. It had hospitals and doctors admired around the globe, and some of the finest engineers and scientists, who only recently had developed the Spitfire fighter and penicillin among other achievements. It was far richer than the vast majority of countries around the world. Hong Kong, in contrast, was a Third World country, like Kenya or India, only probably even poorer than either of those.

Hong Kong in 1945 was described as ‘a barren rock’. It was poor. It had been occupied by the Japanese in the Second World War and then received a flood of refugees with hardly any money. To begin with, average incomes fell in Hong Kong because of this influx of penniless people, so that in 1960 the per capita output of Hong Kong was a mere 21.5 per cent of what advanced Britons produced. Britain was nearly five times more productive per capita and, broadly speaking, correspondingly wealthier.

Then, from 1961 – the year Cowperthwaite became Financial Secretary as it happens – output per person began to grow very fast. The rate in the 1960s was 6.0 per cent while Britain was growing at a snail’s pace in comparison – only 2.3 per cent a year. Britain then had a currency crisis and devalued in 1967.

The prosperity of low-tax Hong Kong overtook that of high-tax Britain.

In the 1970s Hong Kong’s output per person grew even faster – at 6.5 per cent a year. Meanwhile, Britain had to go, cap in hand, to the International Monetary Fund because its credit had run out. Its per capita growth slumped to a mere 1.5 per cent a year.

By 1992 Hong Kong’s growth had been so outstanding – and so vastly better than Britain’s – that its output per head actually overtook that of the ‘mother country’.444 Hong Kong, under the influence of Cowperthwaite, had transformed itself from being a poor relation – a poverty-stricken colony making cheap plastic toys – to Britain’s equal. Hong Kong caught up with Britain in a mere three decades.

People can argue that Hong Kong benefited from a variety of factors which contributed to its extraordinary growth. It had light regulation and virtually no trade barriers. The colony developed a role as an entrepot for China’s trade with the rest of the world. But Cowperthwaite would argue that low tax and small government were the key reasons why the barren rock became richer than the motherland.

Tax and growth around the world

The contrasting stories of Hong Kong and Britain are powerful evidence, but not proof that ‘tax matters’. Is there any other evidence in favour of such a view?

In 1960, one leading country had markedly lower government expenditure than all the others. In most advanced countries, spending was around 30 per cent of GDP.445 But in Japan government expenditure was not much more than half that – only 17.5 per cent.

How did its growth compare? Other countries managed an average growth rate of 4.25 per cent between 1950 and 1973 but Japan did nearly twice as well with an average annual growth rate of 8 per cent. No one could say it had an advantage, as Hong Kong did, in acting as an entrepot for China.

Let’s take 1980 and a country at the other end of the spectrum of spending and taxing. By this time, most countries had significantly increased their government spending as their welfare states had expanded. One country, though, became well known for being particularly enthusiastic so that its spending soared above that of any other. Sweden’s government, in 1980, accounted for 60.1 per cent of all the country’s expenditure.

Over the period which most probably reflects such spending (and the correspondingly high taxes) between 1973 and 1999, what was the Swedish growth rate? A mere 1.4 per cent. When Swedish spending and taxing was at its peak, its growth was lower than that of any other leading country in the world.

We are gradually building up a string of associations: Hong Kong and Japan had low tax and high growth. Britain and, more recently, Sweden had higher spending and much lower growth. But in the end we have to look at studies based on lots of countries, which take into account all sorts of things that might affect growth. Nicholas Crafts, a leading British economic historian, has set about doing exactly this. He appears to have no obvious political bias and considers how things such as technology and capital investment may also affect growth. After considering the impact of these and other factors, he comes to taxation. He concludes that the ‘econometric evidence’ is that taxes on income are ‘distortionary’ and ‘have an adverse impact on growth’.446

He adds that growth in ‘transfer payments’ (an economist’s term for welfare payments and the tax-raising it makes necessary) in the 1960s and 1970s could be part of the reason why growth around the world slowed in the following years.448

Crafts puts this claim in the most cautious, academic terms – perhaps not surprising considering that he is indeed an academic at the London School of Economics – which has long been associated with the welfare state. But in the above, almost incidental, remark he puts forward a big idea: that the entire advanced world has been growing more slowly partly because of the expansion of welfare states.

The OECD similarly looked at many countries to establish the relationship between tax and growth. It came to the conclusion that for every 1 per cent of a country’s economic output that is taken by tax, the output per person falls by 0.6 to 0.7 per cent. So, if a country has, like Britain, taxation of approaching 40 per cent of GDP (compared to well under 10 per cent in the late nineteenth century) it has reduced its GDP by about 20 per cent.449 To put it another way, if we had not increased taxation, our output – and income – per capita would be a quarter higher.

What is wrong with tax?

Why should tax damage growth? Many will think, ‘If someone is taxed at 60 per cent or 70 per cent, surely they will go on working anyway? They will keep going to the office and trying to get promotion and so on. They get other things from work apart from cash.’ That may be true for some people – notably those like civil servants in jobs where there is little obvious opportunity to react to high taxes. But someone thinking of setting up a new business may be deterred if, after all the work and the risks, he or she will only be allowed to keep 60 per cent of any profit. Such a person might just take an office job instead. If so, the economy would lose someone who could have helped improve national productivity.

Someone on benefits may find that taxation means he or she may not be much better off in work. So he or she may not take a job. That would be a direct loss of output because of taxation.

A company thinking of investing in research will have less cash coming in, if the research is successful, if its profits are taxed at 40 per cent than a company in another country which is only taxed at 15 per cent. The heavily taxed company may decide the risk-reward ratio is not good enough – because of the tax on success – to invest in the research at all. The lightly taxed company in another country may go ahead and make the investment.

Another company might like to expand quickly, hiring more people. But there is employer’s national insurance to pay on everybody it hires. The company has only got a certain amount of money in the kitty. Therefore it hires fewer people and expands more slowly.

These are some of many, varied ways in which tax discourages employment, investment and entrepreneurial activity. Part of the effect, over the long term, is psychological. In Britain in the high-tax 1970s, few people wanted to start businesses. There was little point. You would only get taxed for your enterprise. Many with ambition and talent left the country. It was referred to as ‘the brain drain’. A culture of enterprise was lost.

In Hong Kong, at the same time, the attitude of get-up-and-go was electric. The colony buzzed with rags-to-riches stories. Hard work and full employment were normal parts of life. Expatriates and indigenous people alike were enthused by the entrepreneurial spirit. One of the greatest fortunes was made by Li Ka Shing, who started off in toy manufacturing and went on to become one of the richest men in the world with investments including Orange, the mobile phone company, and huge property holdings in Hong Kong, mainland China, Canada and the rest of the world.

Britain could have been a rich country

Let us imagine, for a moment, that Britain had not massively developed its welfare state in the twentieth century. Using the OECD estimate – that every 1 per cent of tax reduces output by 0.6 to 0.7 per cent – how wealthy might Britain have become?

Using the OECD estimate mentioned above, instead of having output per capita of US$27,650 in 2003450 as we did, it would have been US$34,562. We would have ranked as the third richest country in the world instead of the fifteenth. We would have had higher average incomes than the Swiss or the Japanese. The only countries with higher output per person than ourselves would have been America and Norway. And since we would not be as heavily taxed as them, our take-home pay would be a little higher even than theirs. It would be the highest in the world.

There seems no reason why British people would not easily have the highest average incomes in the whole world if we had stayed as a low-tax society. It is reasonable to suppose that there are cumulative effects in being a low-tax country that were not captured by the OECD analysis. An entrepreneurial culture develops over time. It does not respond instantly to changes in tax. If Britain had not created its welfare state but had kept taxation below 10 per cent of national output throughout the twentieth century, it seems likely that Britain would be decidedly more than a quarter richer than it is now. With such a spur to growth, it could easily have outpaced other countries in its productivity and success. It would now have a high rate of saving, a high rate of investment and research (based on retaining virtually all profits made); it would consequently be a leader in technology and medicine. Instead of the top innovative companies in the world being predominantly American – IBM and Boeing in the 1970s and more recently Microsoft, Intel and Amgen – the world leaders would include a large number of British names, as indeed used to be the case.

What about the poor?

The really important thing, many will think, is the wealth of people on average or below-average incomes. How would that have been affected if Britain had remained a low-tax society?

Cowperthwaite argued that a successful economy would drive up the wages of the average working person. He suggested, though he did not put it so grandly, that successful capitalism redistributes wealth to the less well-off. Is there any evidence for this?

Not many British economists have even considered the idea – perhaps because most have been educated to think that only tax redistributes wealth. Meanwhile many non-economists probably adopt the saying ‘The rich get richer and the poor get poorer.’

The statistics, though, suggest something different. In 1938/9, the top 1 per cent accounted for 17.1 per cent of all incomes in Britain.451 Ten years later, their share had fallen to 10.6 per cent. Their share kept on falling so that by 1972/3 it was down to 6.4 per cent. So the richest certainly do not seem automatically to get relatively richer as an economy grows. Rather the reverse. It is true that those coming between twenty and fifty out of every hundred people ranked by income were the biggest relative gainers over this period. These figures suggest a spreading out of income from the richest which does not immediately reach those of below-average incomes. But this may be because the least well-off during this period became increasingly dependent on benefits. In any case, the poor did not get poorer. According to these figures, their income rose just slightly faster than the average rise in incomes.

If we take a longer period, with less distortion from benefits – from 1911 to 1960 – a greater redistribution of wealth appears. The share of the very richest was slashed from 69 to 42 per cent. Those outside the top 10 per cent more than doubled their assets – from an 8 to a 17 per cent share. Looking at earnings of those in work is probably the best way of reducing the distorting effect of changing rates of welfare dependency. In 1913–14, ‘higher professionals’ earned 5.2 times the wages of unskilled workers. This great premium was slashed as the economy grew, falling to only 2.4 times the average by 1978.452

Certainly there are counter-arguments and conflicting data, but there is some reason to think that capitalism over time does spread wealth to the less well-off disproportionately.453 If this is true, it is reasonable to suggest that ‘successful’ capitalism – that is to say, the fast growth that low taxes encourage – should promote a correspondingly faster redistribution of income and wealth.

In 2002, the vast majority – 80 per cent – of all adults in full-time work were earning between £11,261 and £38,788. Considering that the total workforce includes manual and non-manual workers, some of whom have only just started work and some of whom are at the top of their career, the difference is not so very great. The difference is surely a lot less than when, in the first half of the twentieth century, anyone who was upper middle class expected to be so much richer than the rest that he or she could employ several servants. That kind of marked disparity of income has disappeared, again suggesting that economic growth does indeed redistribute income to the less well-off.

In the meantime, we know one thing for sure: there is one aspect of modern taxation that would have scandalised every one of the original creators of the welfare state, including David Lloyd George, Winston Churchill, William Beveridge, ‘Rab’ Butler and Aneurin Bevan. Modern politicians and observers have become accustomed to it but it was never in the worst nightmares of the pioneers. Poor people are now taxed.

The government’s position is that anyone with less than 60 per cent of average earnings is in ‘poverty’. This definition of poverty may be badly flawed but it is certainly true that someone with only 60 per cent of average earnings can be described as ‘relatively poor’.

How does the government treat someone in that position?

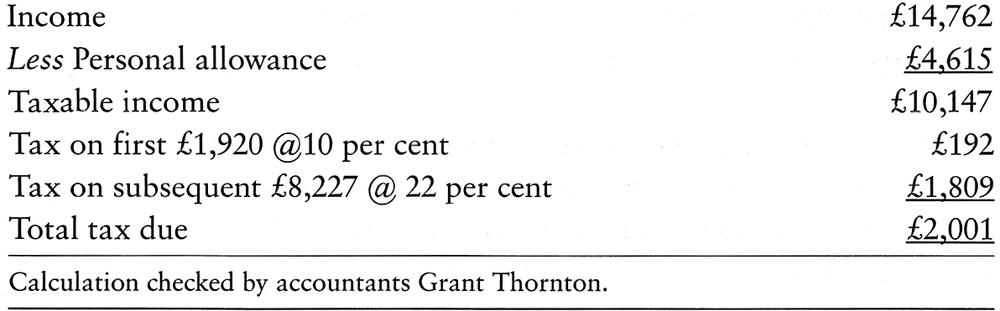

In April 2002, average earnings were £24,603,455 so someone on 60 per cent of average earnings received £14,762. It could be, say, a widow aged sixty who still did some work or had a small pension. If her income was 60 per cent of average earnings, her tax position (using the personal allowances and tax rates of 2002/3456) was as follows:

In other words, the state took a woman it considered to be in poverty and forcibly removed £2,001 a year from her. In addition to that, she faced council tax, excise duty on alcohol and on petrol, VAT on most products and a variety of other indirect taxes. Lloyd George would have been astonished, Beveridge uncomprehending and Bevan disgusted.

In 1938/9, despite the state welfare which already existed,457 there were still only 3.8 million individuals or couples who paid income tax. In the following decades, the numbers have steadily spread out to include virtually everybody in work. The projected number of people expected to pay income tax in 2003/4 was thirty-one million individuals.

Modern politicians and the media accept it as simply normal that the relatively poor should be taxed. But it is quite contrary to the original intentions.

Of course it is easily possible for people, with hindsight, to come up with reasons why it is all right for the relatively poor to pay tax. They can say that the poor are taxed to pay for things they will themselves benefit from such as pensions and healthcare. In other words, the government takes money away to give it back later. But when the state takes money even from the poor, the question ‘is the money well spent?’ becomes all the more urgent and important. If it is not well spent, it is appalling to think that money is forcibly taken from the poor and then wasted. This is especially so, bearing in mind that if the welfare state had not been created at all, the relatively poor woman already mentioned would probably have a much higher income to start with, probably at least £18,452 (25 per cent more than what she has now), and she would also suffer no income tax whatever. Her take-home income might therefore have been nearly 50 per cent greater.

High taxation is a major part of what is wrong with the welfare state. It has made people – people on average incomes and below – a great deal poorer than they would otherwise have been – the very opposite of what was intended.

Notes

432 Hoover Digest, 1998, no. 3.

433 BOAC was a British long-distance airline, which was later nationalised and subsumed into British Airways.

434 I tried to check it and much else besides. As part of my research he was telephoned at his home in St Andrews – where he remains a member of the Royal and Ancient Golf Club. But he declined to be interviewed.

435 Much of the research on Sir John Cowperthwaite was done for me by Christian Wignall, to whom I am most grateful. The reference to Vespasian is from a talk which Christian gave in San Francisco in November 2003. The remark about Scottish Protestantism was made by Professor Alvin Rabushka.

436 Butler, David and Butler, Gareth, British Political Facts 1900–1994 (Macmillan, Basingstoke, 1994), p. 335. Prescription charges were reintroduced in 1968 with certain exemptions.

437 Ibid. But the start date was delayed until 1973.

438 Ibid., p. 343.

439 General government expenditure as a percentage of gross domestic product, 1901 to 1998, Social Trends 30 (Office for National Statistics, 2000), accessed on Office for National Statistics website.

440 Field, Frank et al., To Him Who Hath: A Study of Poverty and Taxation (Pelican, Harmondsworth, 1977), p. 32.

441 Ibid.

442 Butler and Butler, British Political Facts 1900–1994, p. 394.

443 General government expenditure was 42.2 per cent of GDP in 1986. Source: Social Trends 30, viewed on National Statistics website.

444 The growth of Hong Kong’s income compared to Britain’s has been jerky because of exchange rate movements but, whichever way you measure it, the outperformance by Hong Kong was astonishing.

445 Britain was on 32 per cent, the USA on 27 per cent and Germany 32.4 per cent.

446 He suggests that indirect taxes such as VAT are not a problem. Even if this is entirely true, how many leading countries rely exclusively on indirect taxation? Precisely none. As soon as countries need to finance a welfare state, they inevitably tax income and damage growth.

447 Quoted in Edward Leigh, Right Thinking: A Personal Collection of Quotations Dating from 3000 BC to the Present Day Which Might Be Said to Cast Some Light on the Workings of the Tory Mind (Hutchinson, London, 1979).

448 ‘Throughout the OECD, government spending is now vastly higher than before World War II, and the surge in transfer payments financed by distortionary taxation during the 1960s and 1970s emerges as a candidate to explain part of the subsequent growth slowdown.’ Crafts, Britain’s Relative Economic Performance 1870–1999 (IEA, London, 2002).

449 Unfortunately the government’s figures on tax as a proportion of GDP are not necessarily calculated in a way that is universally considered sound. In 2003, net taxes and social security contributions were projected to be 36.3 per cent of GDP. However, this figure was stated to be net of personal tax credits. Some observers believe such credits should be considered as part of social-security spending, not as negative tax. Amidst the obscurity in which public finances are now draped, it is not clear – except perhaps after more extensive investigation – what the level of taxation is, on a basis that might receive wider acceptance. In 2000/01, which may be before credits became such an important part of government tax policy, tax was stated to be 37.4 per cent of GDP.

450 World Bank figures adjusted for purchasing power parity.

451 Royal Commission on the Distribution of Income and Wealth, date uncertain, supplied by Inland Revenue press office to author in January 1994.

452 Routh, Guy, Occupation and Pay in Great Britain 1906–79 (Macmillan, London, 1980), cited in A. H. Halsey and Josephine Webb (eds), Twentieth-century British Social Trends (Macmillan, Basingstoke, 2000).

453 One can argue that the lower premium for top jobs in the late 1970s was due to the very high taxation of the time, which encouraged employers to use every possible means to remunerate higher-paid employees in ways other than their salaries. Meanwhile the Low Pay Unit has offered conflicting data for relative earnings.

454 Pelican, Harmondsworth, 1977.

455 Office of National Statistics, telephone conversation with press office, 18 September 2003. Figure is for male and female, manual and non-manual.

456 To make her tax bill as low as possible.

457 This included pensions, unemployment benefits, state-subsidised education, national assistance and council housing.

458 Op. cit.