It is nine years since this book was first published. Has anything changed about the welfare state we’re in?

It seems like a series of incompatible opposites, like the description of how things were in the opening sentences of Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities. It is a time of hope and a time of despair. Good news keeps coming and the bad news gets worse. Much has changed and nearly everything remains the same.

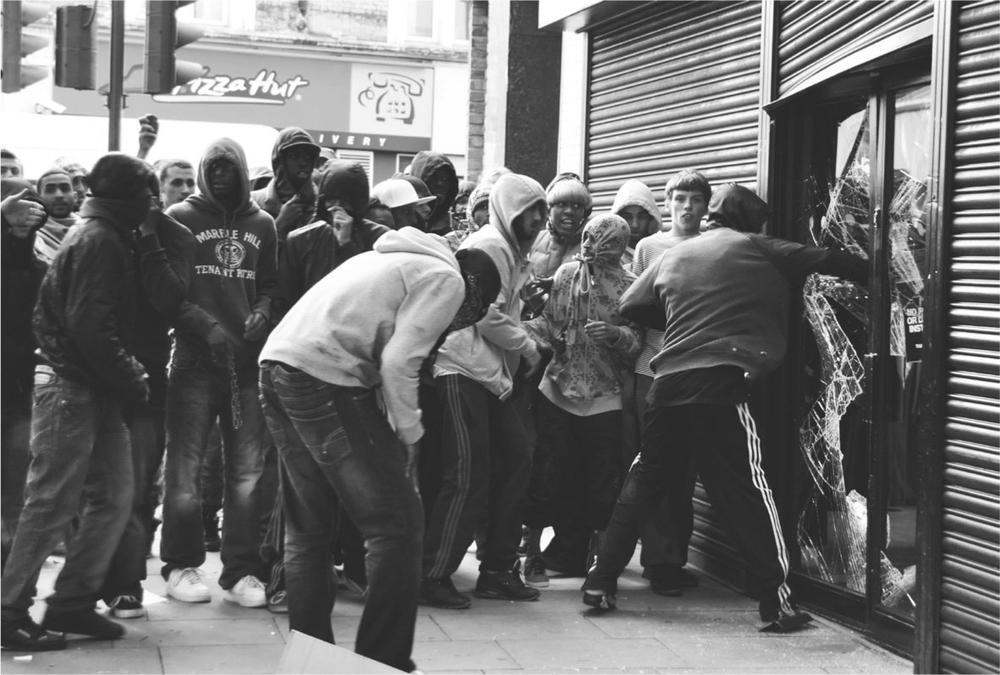

Looting during London riots in 2011

The disjunction is between, on the one hand, the words, intentions and actions of both politicians and the public and, on the other hand, the reality on the ground.

People’s views have certainly shifted. They are much less likely now to treat welfare benefits as obviously good things. Instead, they are more wary – even suspicious. The British Social Attitudes Report reveals that the proportion of the public which agrees that people would stand on their own feet if welfare benefits were less generous has more than doubled – from 26 per cent in 1991 to 54 per cent in 2011.i

Many politicians have moved on, too. I have met a few Labour Party ones who have surprised me with the toughness of their attitudes to welfare provision. Meanwhile the coalition government which came to power in 2010 has embarked on fairly radical reforms.

But how radical are they really? The man behind them has been Iain Duncan Smith, the Secretary of State for Work and Pensions. He is the first minister in my memory who has arrived in the job with real knowledge and understanding of the issues. So he hit the ground running. Most people are aware that the big new idea is to consolidate many welfare benefits into one: the Universal Credit. This is meant to ensure it is profitable to work at any level of income compared to relying on benefits.

That is a worthwhile effort and can do nothing but good. But there is a catch. It is time for one cheer rather than three. The degree to which it is worth working is not as great as would be desirable. There are rumours of big arguments between the Department for Work and Pensions and the Treasury because, at existing benefit levels, making work clearly pay well at all levels means giving quite a lot of money to people who are already in a job. The Treasury was apparently unwilling to lay out as much cash as was needed to make the financial incentive really powerful. The politically difficult alternative which could have made work clearly pay more would have been a cut in benefits.

There is also a complication in that, in fact, not every benefit is included. Council tax benefit is outside it, which means there may remain some circumstances in which work may bring a negligible reward. Still, the Universal Credit remains a bold reform especially as it includes housing benefit, which has been a major roadblock to work incentives for decades. The value of housing benefit has also been reduced. Overall, incentives are being modestly improved.

Meanwhile a lot of effort is being put into helping those who have been unemployed for a year to get jobs. They are being assisted to become more employable with training, literacy lessons, practice at interview technique and so on. If they refuse to engage in the process, there are sanctions including withdrawal of benefit. That is highly desirable and follows what is happening in many other countries. But it is clear that it would be better to give that support and pushing much sooner after someone becomes unemployed. However that costs money and the government has not been willing to provide it. There has been progress but it is not dramatic change.

Much publicity has been given to the new ‘benefit cap’ of £26,000 – an annual limit on what a couple or a lone parent can receive on benefits.ii It only affects a small minority but at least it adds to the theme tune of our time: that people should work rather than sink into a benefits lifestyle.

More people are being assessed for whether they are really entitled to be on Incapacity Benefit. I should mention that this benefit has been renamed Employment and Support Allowance but since these words give little idea of what one is talking about, I am tempted to stick to the previous name. Also much publicised has been the 1 per cent limit on the rise in most welfare benefits for three years up to 2016.iii That could mean a cut in welfare benefits of over 3.5 per cent in real terms and an even bigger drop in comparison to average earnings. The incentive to work will undoubtedly become more clear-cut over this period. But to some extent it just compensates for the period beforehand during which benefits rose faster than earnings.

A change that is much less well known is the requirement that more lone parents should seek work. Until 2008, they were not required to seek work until their youngest child reached the age of sixteen. This started to be reduced under the previous Labour government and has taken place gradually. But over time, the change has been substantial. Since 2012, a lone parent with a youngest child of five or over has become obliged to seek work.iv Far more lone parents are now expected to work. It is a big and necessary change.

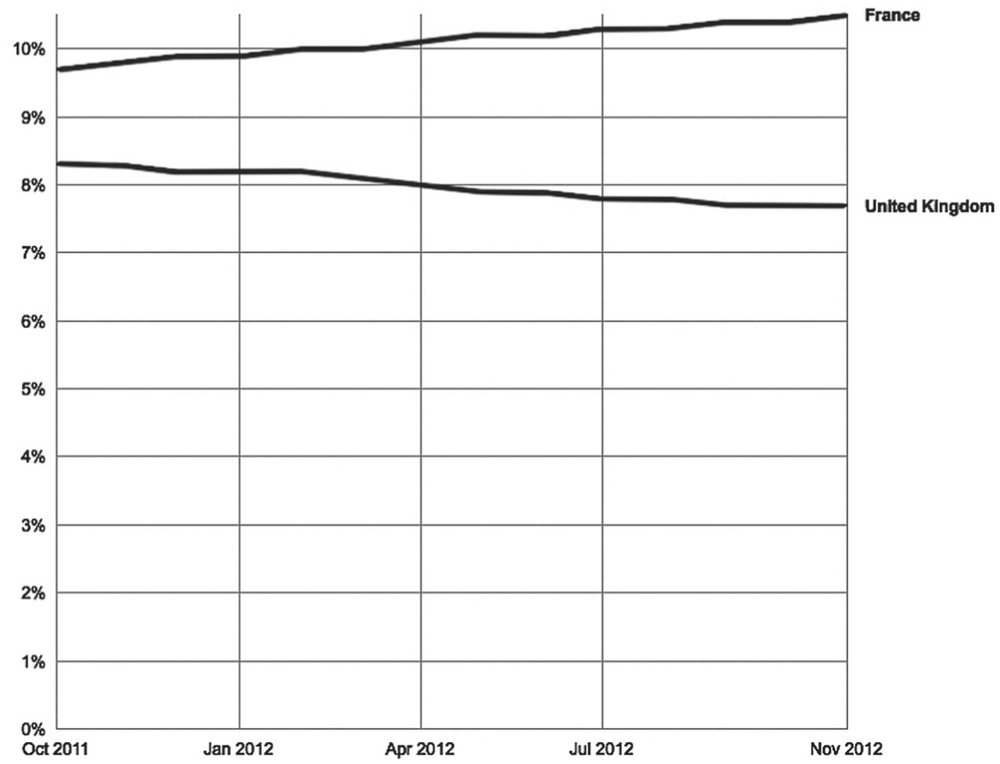

This and the continuing testing of those on incapacity benefit has meant a steady stream of extra people being added to the numbers seeking work. This development should have increased the official unemployment rate. The jobless total did of course rise between 2005 and 2011 but part of that was obviously due to the recession followed by very low growth. What is remarkable is that the jobless figure actually fell in 2012 when the economy was flat. That is significant and encouraging.

Unemployment rate of France and the UK since October 2011.v

The unemployment figures are also a lot better than in comparable countries such as France, let alone Spain. It is hard to know exactly which measures have brought about this change. It may be some combination of the measures mentioned above. The increase in the personal tax-free allowance may also have helped. It is even possible that the drive to work and move away from benefits has had some psychological impact on the unemployed and the civil servants and others who advise them. However it has been caused, it is welcome.

All this is mostly positive. But standing back and looking at the big picture, the fact remains that mass unemployment is still a permanent feature of modern Britain. We are nowhere near the low levels of unemployment of Switzerland or Singapore where the willingness to give benefits is less and insistence on work is more. Although we have shown more job-preserving wage flexibility than most other European countries, that is a low standard to apply. We still have a minimum wage and even the Low Pay Commission – which decides on its level – concedes that there is evidence that the minimum wage deters people from working as many hours as they otherwise would.

Overall, the coalition government has worked hard to make significant changes in welfare benefits. They are useful and, in the British context, politically radical. They will make things better. But they do not go far enough to rid us of the misery of permanent mass unemployment.

Education is the other major area where the coalition government has acquired a reputation for making significant change. It has introduced measures to bring rigour back into the classroom. Reducing the widespread use of coursework in public exams is an example. Coursework is subject to abuse and, to put it bluntly, cheating. More schools are being made into ‘academies’ which have more independence. Some are good but overall the results are mixed. Teachers are to be paid more on merit and less on the basis of how long they have been doing the job. These are mostly good things. But the most radical change is the introduction of ‘free schools’ – schools set up by parents and/or teachers which have much more independence.

This is the reform that has the potential to make a big difference. At last, schools will live or die according to whether they are chosen by loving parents rather than existing just because they have existed before – a way which has allowed dreadful schools to blight children’s lives over decades. But this – the greatest hope in education for generations – has been a revolution with one hand tied behind its back. Profit-making companies have not been allowed to set up these schools. The example of Sweden shows that profit-making companies can provide a bigger surge in numbers than anything else. There, free schools account for more than 10 per cent of places and as many as 25 per cent in Stockholm.vi It is confidently expected that they will rise to account for 30 per cent of schools.

For a long time in Britain the creation of free schools has also been hampered by too many planning restrictions on what kinds of buildings can be turned into schools. Only in January 2013 was it announced that there would be future legislation so that offices, theatres and so on could be converted in this way.vii There needs to be a rigorous obligation on local planning authorities to grant planning permission unless there are the most pressing and unusual reasons for not doing so. For the time being, progress has been far too slow. In early 2013, fewer than a hundred free schools had been created, with another 114 due to open in autumn 2013.viii This compares with a total of over 24,000 schools in England.ix The proportion is tiny. For the majority of children almost nothing has changed.

In healthcare, the changes have been less radical and give cause for concern. Power is being put into the hands of general practitioners to commission care. This appears to give them a conflict of interest. They are meant to give the best possible care to their patients but if someone needs expensive care, the money comes out of the doctors’ own budgets. They are even to be given a financial incentive not to send patients to hospital.x This seems far from ideal.

On the other side, they are at least able to send patients to the rapidly increasing number of independent treatment centres for operations. The competition between these centres and NHS hospitals is likely to drive up standards and keep waiting times below what they would otherwise be. But the NHS monopoly remains with its appalling waste and treatment that falls well below the standards of other European countries. The five-year survival rate for colorectal cancer, for example, is seventeenth out of twenty OECD countries.xi The scandal of the dreadful way patients were treated at Stafford Hospital with people being left in their beds in their own faeces and urine while some staff were ‘dismissive’ of their needs was a recent illustration that the rhetoric of a heroic NHS being the fulfilment of idealistic hopes is an illusion.xii Nobody will ever know for sure how many died because of the terrible care but certainly hundreds and up to 1,200. The negligent treatment of patients went on for years. There is also reason to believe Stafford was not an isolated case. Much has emerged about how the NHS has become a place of targets, fearful employees and staff contracts requiring silence about what is going wrong.

The NHS is a scandal which no political party is currently willing to take on but which will never go away. It simmers on the back burner and perhaps one day, unpredictable in its timing, the issue will boil over and a completely new system will be introduced. Massive change has taken place in the Netherlands and it could happen here, too.

Taken as a whole, there have been some reforms to the welfare state varying between the moderate and the small. But down at ground level, modest improvements have been more than matched by continued deterioration. The changes made by politicians, however worthy, are taking time to filter down. The downward momentum of the past is taking years to turn around.

There are still 1.5 million unemployed.xiii A little under 2.5 million are on incapacity benefit.xiv The proportion of births outside marriage has risen still further from 40 per cent in 2001 to 47 per cent in 2011. This compares with only 6 per cent back in 1961.xv There are 3.2 million children being raised by lone parents.xvi Truancy from school remains high with 400,000 pupils repeatedly absent in England alone.xvii Illiteracy remains widespread. The ill still do not get the latest drugs that they would receive in other countries and they are less likely to have the tests and operations which would benefit them.

It is true that crime appears to be falling, which is welcome. Frankly it is not clear why. As people struggle to explain it, I have even seen it argued that it is due to the decreased use and then banning of leaded petrol. But we should recognise, too, that people defend themselves against crimes much more than before. Doors are double-locked and young children not allowed to walk home from school as I was, in London in the 1950s, at the age of six or seven.

Standards of behaviour continue to decline. It is hard to find objective proof but one sees signs of it in ordinary life. Children walking home from school who do not move aside for someone walking in the opposite direction. The children are monitored by teams of community support officers to limit the vandalism. Such precautions were not necessary in previous decades. People often will not stand for an elderly person on a bus or tube. Lorries stop and block a road then abuse anyone who complains. Teenage girls get drunk and incapable on the streets late at night. Only the most spectacular manifestations of bad behaviour now make it into the news. The most notable of these were the riots in various parts of London in August 2011 with shops looted and burnt and over 1,100 charged. It was a spectacular event that temporarily shocked the country into facing the fact that all is not well.xviii

The proportion of children being brought up without married parents continues to rise

The proportion cared for by a lone parent has stopped rising in the recent years but this may be temporary since the numbers brought up by co-habiting couples have continued to increase and co-habiting couples on average are more likely to break up than married couples. In 2012, the proportions were 62.2 per cent children with married couples (this includes step-parent families), 23.8 per cent lone parents, 13.8 per cent call number with same-sex couples.

Source: Families and Households 2012, Statistical Bulletin of the Office for National Statistics issued November 2012.

The most telling insight I have had recently into the reality of Britain today was a conversation with Frank Field, the Labour MP for Birkenhead who was once welfare reform minister.

He told me how he had been to some schools in his constituency and asked children what they wanted to get from their schools. There were three things:

Drunken women late at night on the streets of Cardiff, 2011.

- how to become good parents

- how to get and keep a job

- how to have lifelong friendships.

The list is poignant. It tells us a mixture of what these children do not have and what they fear they will not get. Children hate to criticise their own parents but they know they have seen or experienced bad parenting. Many have a missing father. They see unemployment around them and they fear it. And many have seen friendships and relationships come and go, giving them a sense of instability.

Frank Field remarked that he was appalled by the poor parenting he had seen. There were children arriving in school who ate with their hands. At an early age, there are even children who are not potty-trained. He asked one father if he had ever tried potty-training his little child. The man replied that, yes, he had tried ‘once’. Some children arrive barely able to speak. They grunt.

At least the child Frank Field referred to had a father around. Frank Field comments that 80 per cent of the children who are poor are from single parent families. And the combination of being poor and badly looked-after has meant that Tesco has reported a change in the pattern of shop-lifting.xix Children now don’t take sweets so much. They take sandwiches. They are hungry.

These children are not seen by opinion-formers in national newspapers and broadcasting. They are the ones living with the legacy of the welfare state described in this book. They are the result of several generations of benefits dependency, lone parenting and bad education – a society that has lost the idea of self-reliance, mutual responsibility, decency and work.

Making this situation better cannot be done by one government. It will take a large body of opinion in the whole country to perceive what is wrong and to want to take action. And even if, very fortunately, that happens, it would take another generation or more to turn the situation around. There are some reasons for hope but for the time being the welfare state we’re in remains pretty grim.

Notes

i 29th British Social Attitudes Report published in 2012. http://www.bsa-29.natcen.ac.uk/.

ii Benefit Cap factsheet published by the Department for Work and Pensions. http://www.dwp.gov.uk/docs/

benefit-cap-factsheet.pdf.

iii BBC online news report, ‘Benefits squeeze to save £3.7bn in 2015–16, Osborne says’, 12 December 2012. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/

business-20610157.

iv Department for Work and Pensions: http://www.dwp.gov.uk/adviser/updates/

changes-to-benefits-for-lone/ and http://www.dwp.gov.uk/

newsroom/press-releases/2012/

mar-2012/dwp027-12.shtml.

v http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.

eu/cache/ITY_PUBLIC/3-30112012-BP/

EN/3-30112012-BP-EN.PDF and http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/cache/

ITY_PUBLIC/3-08012013-BP/

EN/3-08012013-BP-EN.PDF.

vi Author interview with Odd Eiken in Stockholm, June 2011.

vii The Times, ‘Free schools get head start to set up in offices, theatres and shops’, 25 January 2013.

viii http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/education-19460927.

ix http://www.education.gov.uk/

popularquestions/schools/buildings/a005553/

how-many-schools-are-there-in-england.

x Daily Mail, ‘£7,500 “bribe” for doctors to stop sending their patients to casualty’, 3 January 2013, http://www.dailymail.co.uk/health/article-2256397/

Doctors-offered-7-500-bribe-stop-sending-

patients-pneumonia-heart-problems-

hospital.html#axzz2JwUDvYhr.

xi Health at a Glance 2011 (OECD 2011) p. 123. http://www.oecd.org/els/

healthpoliciesanddata/49105858.pdf.

xii Robert Francis Inquiry 2010. http://www.dh.gov.uk/

en/Publicationsand-statistics/Publications/

PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_113018.

xiii Office for National Statistics. http://www.ons.gov.uk/

ons/dcp171778_292911.pdf Labour Market Statistics January 2013.

xiv ‘Early estimate’ for November 2012, Department for Work and Pensions, http://research.dwp.gov.uk/

asd/index.php?page=statistical_summaries.

xv Live births in England and Wales by characteristics of mother, January 2011, Office for National Statistics pdf dated 24 January 2013. http://www.ons.gov.uk/

ons/dcp171778_296157.pdf. 408 the welfare state we’re in

xvi Families and Households 2012, Statistical Bulletin of the Office for National Statistics issued November 2012. http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/dcp171778_284823.pdf.

xvii http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/education-17539608.

xviii http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-14532532.

xix ‘The Foundation Years: preventing poor children becoming poor adults’, the report of the Independent Review on Poverty and Life Chances (HMSO, 2010), p. 15. http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/

20110120090128/ http://povertyreview.

independent.gov.uk/media/20254/

poverty-report.pdf.