Transforming objects by dragging them or their handles on the canvas is easy and intuitive, but it’s not very precise (even when using various constrained modes) and may sometimes feel quite clumsy. Many long-time users of Inkscape prefer to use keyboard shortcuts for most of their transformations.

Keyboard shortcuts for transforming objects are easy to remember, and often, they will make your work a lot easier. Another reason to learn these keys is that, as we will see in the rest of the book, they are used consistently in many other tools and contexts to perform analogous functions—for example, to transform nodes with the Node tool, text characters with the Text tool, or gradient handles with the Gradient tool.

Note

Skewing is not possible from the keyboard, which is understandable given that this operation is not used all that often.

The  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  arrow keys move the selection. The amount of move depends on the modifiers.

arrow keys move the selection. The amount of move depends on the modifiers.

Without modifiers, arrow keys move by 2 px (2 SVG pixel units, not screen pixels, A.6 Coordinates and Units). This is the default value; you can change it in the Steps tab of the Inkscape Preferences dialog.

With

, arrows move the selection by 1 screen pixel. This means the actual distance depends on the zoom level, and you can do finer moves when you are zoomed in or coarser moves when zoomed out. This is one of the most common and useful shortcuts because of its precision and adaptability: With it, you can always move your selection by the minimum distance that is still noticeable at the current zoom.

, arrows move the selection by 1 screen pixel. This means the actual distance depends on the zoom level, and you can do finer moves when you are zoomed in or coarser moves when zoomed out. This is one of the most common and useful shortcuts because of its precision and adaptability: With it, you can always move your selection by the minimum distance that is still noticeable at the current zoom.With

, arrows move by 10 times the distance as they would without

, arrows move by 10 times the distance as they would without  . So, simple

. So, simple  -arrows move by 20 px (by default) and

-arrows move by 20 px (by default) and  -arrows move by 10 screen pixels at the current zoom.

-arrows move by 10 screen pixels at the current zoom.

The ease and predictability of the keyboard move commands make them useful in a lot of different situations. For example, sometimes I need to do something to objects obscured by some large foreground object.  -clicking to “select under” works, but it’s often too cumbersome; moving the foreground object to a new layer and hiding that layer is also a good option, but it is even more cumbersome. In such cases, I often select the foreground object and move it off (to the right) by several

-clicking to “select under” works, but it’s often too cumbersome; moving the foreground object to a new layer and hiding that layer is also a good option, but it is even more cumbersome. In such cases, I often select the foreground object and move it off (to the right) by several  or

or  keystrokes. When finished, I will select it again and move it precisely back into place by the same number of movement keystrokes in the opposite direction. (Just remember to not use

keystrokes. When finished, I will select it again and move it precisely back into place by the same number of movement keystrokes in the opposite direction. (Just remember to not use  -arrows in this case because you may be at a different zoom level when moving the object back, and that would affect the distance.) The same “move away and then back” trick is useful for analyzing complex compositions when I’m trying to find out which parts of the drawing correspond to which objects.

-arrows in this case because you may be at a different zoom level when moving the object back, and that would affect the distance.) The same “move away and then back” trick is useful for analyzing complex compositions when I’m trying to find out which parts of the drawing correspond to which objects.

The  and

and  keys (angle brackets) scale the selection down and up, respectively. Keyboard scaling always preserves aspect ratio and is performed around the geometric center of the object’s bounding box (not around its moveable rotation center). Again, the amount of scaling depends on the modifiers.

keys (angle brackets) scale the selection down and up, respectively. Keyboard scaling always preserves aspect ratio and is performed around the geometric center of the object’s bounding box (not around its moveable rotation center). Again, the amount of scaling depends on the modifiers.

Without modifiers, the

and

and  keys scale by 2 px (2 SVG pixel units, not screen pixels). This increment is applied to the biggest of the two dimensions of the bounding box; for example, if the object is wider than it is tall, its width grows by 2 px (the left and right edges of the bounding box move by 1 px each, in opposite directions), and its height grows by a proportionally smaller amount. The default value is 2 px; you can change it in the Steps tab of the Inkscape Preferences dialog.

keys scale by 2 px (2 SVG pixel units, not screen pixels). This increment is applied to the biggest of the two dimensions of the bounding box; for example, if the object is wider than it is tall, its width grows by 2 px (the left and right edges of the bounding box move by 1 px each, in opposite directions), and its height grows by a proportionally smaller amount. The default value is 2 px; you can change it in the Steps tab of the Inkscape Preferences dialog.With

, the

, the  and

and  keys scale by 2 screen pixels, so that in the larger dimension of the bounding box, the edges move by 1 screen pixel each in opposite directions. As with

keys scale by 2 screen pixels, so that in the larger dimension of the bounding box, the edges move by 1 screen pixel each in opposite directions. As with  -arrows, this means the actual distance depends on the zoom level, and you can scale finer when you are zoomed in or coarser when zoomed out.

-arrows, this means the actual distance depends on the zoom level, and you can scale finer when you are zoomed in or coarser when zoomed out. has no effect on the

has no effect on the  and

and  keys. This is because on some keyboards, you need to press

keys. This is because on some keyboards, you need to press  just to get these characters. By the way,

just to get these characters. By the way,  (comma) and

(comma) and  (dot) work as

(dot) work as  and

and  , respectively, because on many keyboards they are physically the same keys.

, respectively, because on many keyboards they are physically the same keys.With

, the

, the  and

and  keys scale by a factor of 2—that is, they make the selection twice smaller and twice larger, respectively. This is convenient when you need to scale something by a large ratio; for example, start by pressing

keys scale by a factor of 2—that is, they make the selection twice smaller and twice larger, respectively. This is convenient when you need to scale something by a large ratio; for example, start by pressing  a few times to get within the ballpark of the required size, then adjust it more precisely using the same key with

a few times to get within the ballpark of the required size, then adjust it more precisely using the same key with  or without modifiers.

or without modifiers.

The  and

and  keys (square brackets) rotate selection counterclockwise and clockwise, respectively. Rotating is performed around the moveable rotation center that is visible in Selector’s rotate mode; unless you moved it, it’s the geometric center of the object’s bounding box. Again, the amount of rotation depends on the modifiers.

keys (square brackets) rotate selection counterclockwise and clockwise, respectively. Rotating is performed around the moveable rotation center that is visible in Selector’s rotate mode; unless you moved it, it’s the geometric center of the object’s bounding box. Again, the amount of rotation depends on the modifiers.

Without modifiers, the

and

and  keys rotate by 15 degrees. This is the same angle constraint value that is used by mouse rotation with

keys rotate by 15 degrees. This is the same angle constraint value that is used by mouse rotation with  . It is changeable in the Rotation snaps every drop-down menu in the Inkscape Preferences dialog.

. It is changeable in the Rotation snaps every drop-down menu in the Inkscape Preferences dialog.With

, the

, the  and

and  keys rotate by such an angle that the bounding box corners of the selection move by 1 screen pixel. This means the actual rotation angle depends on the zoom level, and you can rotate finer when you are zoomed in or coarser when zoomed out.

keys rotate by such an angle that the bounding box corners of the selection move by 1 screen pixel. This means the actual rotation angle depends on the zoom level, and you can rotate finer when you are zoomed in or coarser when zoomed out. has no effect on the

has no effect on the  and

and  keys, for the same reason it has no effect on the

keys, for the same reason it has no effect on the  and

and  keys.

keys.With

, the

, the  and

and  keys rotate by 90 degrees (one quarter of the full circle).

keys rotate by 90 degrees (one quarter of the full circle).

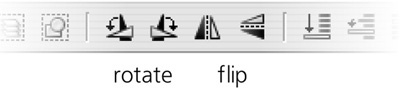

Also, four common transformations are accessible both as keyboard shortcuts and as buttons on the Selector tool’s controls bar, as shown in Figure 6-9:

To make two objects exchange places, you can use double flipping: First, select them both and flip them as a whole; then, select each one in turn and flip it individually to restore it. To make the exchange two-dimensional, you will need to perform this procedure twice, once using horizontal flipping ( ) and then using vertical flipping (

) and then using vertical flipping ( ).

).

Artists sometimes use flipping to check their work. When you’re drawing something, it’s easy to grow progressively blinder to your errors exactly because you’re looking at them for so long. In this situation, flipping the entire drawing horizontally or vertically gives you a fresh look at the drawing and makes many problems with shape, balance, or composition painfully obvious.