HISTORY

Consider the situation in 1789. There really was no concept of the atom, other than to postulate that there was such a thing, the smallest unit of an elemental substance. No thought or concept of its constituent particles—electron, proton, or neutron. No concept of a nucleus.

Many chemists still clung to the idea that all elements were composed of numbers of hydrogen atoms, a holdover from the days of alchemy when some believed that elements could be transformed one into another,1 for example, from lead into gold. The noble gases were still unknown and would not begin to be discovered until over a hundred years later, in 1894. Since they were all gases and at that time were found in combination with nothing, they simply did not exist as far as anyone knew.

The nineteenth century was a period of great progress for quantitative research and the systematization of information. By the middle of the century, science had transformed from the quest of well-off hobbyists to the funded operation of dedicated researchers. Laboratories were set up not only to allow for research but also to serve as schools for instruction under the guidance of the leading researchers of the times. And the students in these laboratories then set up such laboratories of their own.

Beginning in 1817, scientists began to notice that certain groups of elements had similar chemical properties. For example, they observed similarities in lithium, sodium, and potassium. These of course are elements of a group whose atoms we now know to have one electron beyond a closed shell of electrons. They also observed, for example, similarities in chlorine and bromine, two of the elements with one fewer electron than fills a shell.

Researchers eventually began listing the elements in order of their relative atomic weights, which by then they were able to calculate from measurements of the weights of substances that combined with each other. If the atomic weight of hydrogen, the lightest element, was defined to have an arbitrary unit weight “one,” and it combined with approximately eight times its weight of oxygen, then the atomic weight of oxygen would be surmised to be eight, unless of course (as had also been suggested by that time) each atom of oxygen had combined with two atoms of hydrogen, in which case the atomic weight of oxygen would be correctly deduced to be approximately 16. (For all but the lightest elements, approximately half of this weight would come from the protons and the other half from the neutrons, particles of both types composing the atomic nucleus.)

The listing of elements in order of increasing atomic weight turned out to be approximately the same as listing them according to increasing atomic number (but they didn't even know of atomic number at the time). As researchers counted through the elements, they would periodically come to elements that had chemical properties similar to the properties of previously counted elements, that is, elements of the same group. As early as 1843, they began to arrange the elements in tables, periodic tables, that placed the elements in order of their atomic weights but also grouped them in rows or columns according to their chemical properties.2 For example, if the elements were listed by increasing atomic weight in rows, then the tables would be arranged so that the periodically similar groups of elements appeared in columns.

In all, there were at least six substantial contributors to the evolution of the periodic table. The best-known of the early tables is one published by chemist Dmitri Mendeleev in 1869. It is similar to one put together at about the same time by Oskar Lothar Meyer. In all, Mendeleev published some thirty tables and produced about thirty more that remained unpublished. These appeared in various forms, with the elements listed in order of increasing atomic weights down columns, or across rows, or even in what is labeled as a “spiral” form. While the type of arrangement doesn't change the basic information of the elements, it can indicate in somewhat different ways the underlying chemistry and physics of those elements.

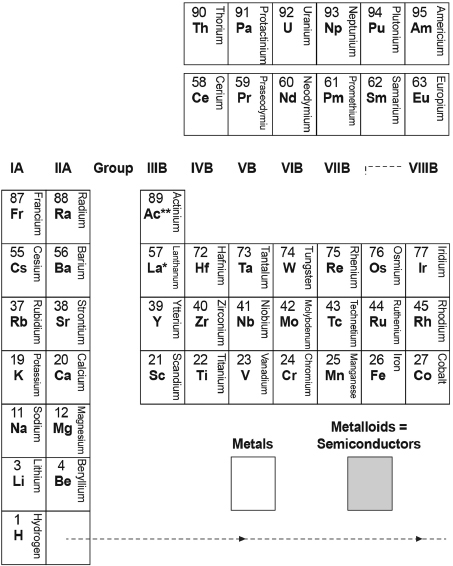

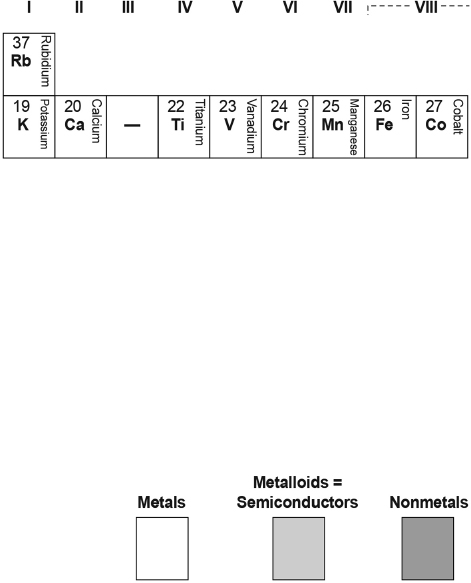

One long form table that Mendeleev published in 1879 placed the sixty-one then-known elements in order of atomic weights within rows, and it grouped those elements having similar chemical properties one above the other in columns.3 Since the number of elements between like elements varies, this meant that the successive rows thus created would not contain the same number of elements. And the table had many blank spaces where Mendeleev believed that yet-undiscovered elements should be located. But with all of its blanks and unevenness, each row would contain one complete cycle of properties (one period).

Table B.1 is a redrawn version of just the first five rows of Mendeleev's 1879 table, retaining all of the columns with their Roman-numeral group headings, but otherwise altered in several ways. First, I've “flipped” the table upside down (starting the first row of elements with hydrogen at the bottom center) to more easily show a connection to the physics of the hydrogen atom that we describe in Chapter 13. Though I've retained the chemical symbol for each element, I've added each element's atomic number (which wasn't known at the time) and its full name. And, finally, I've darkly shaded the regions of the table occupied by the nonmetals, left without shading the regions of the table occupied by metals, and lightly shaded the regions in between that are occupied by the semiconductors. (The inert elements that would occupy a rightmost column had yet to be discovered at the time that this table was constructed.)

Mendeleev (or Scerri?)4 labels the first seven columns of like elements (groups) in Table A.1 successively with Roman numerals I through VII and then the next three columns together as Group VIII. (All of these labels are shown at the top of each column.) Then he shows some ambiguity as to how to arrange the table, indicating a similarity to the properties of the first columns by starting again with the Roman numerals I, II, and so on, to label the last seven columns. So the elements with properties that we now know all follow from those of hydrogen appear in two columns, and both of these columns are labeled as Group I.

Table B.1. “Flipped” First Rows of Mendeleev's Periodic Table of 1879 (Redrawn).

PREDICTIVE CHUTZPAH

The key to being able to start constructing the periodic table was in the realization that the nature and strength of the chemical interactions of each element should be examined in relation to its atomic weight, a physical property. Mendeleev was not alone in this realization, although his may have been a more profound understanding.5 What set him apart was his conviction in the patterns revealed by the table, and this led him to boldly (and famously) predict the existence, chemical properties, and approximate atomic weights of substances that had not even yet been found. (He indicated these by including blank spaces in his tables.)

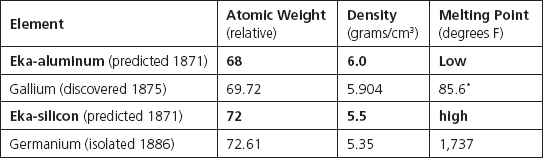

Among the first four of Mendeleev's predictions (that were made in a ninety-six-page article published in German in 1871) were what he called “eka-aluminum” and “eka-silicon” (eka is Sanskrit for “beyond”), with chemical properties expected to be similar to those of the named already-known lighter elements preceding them in the second Group III and IV columns of his 1869 table. The predicted properties of these predicted new elements are compared as follows to the properties of two later-discovered elements that now fill two of the gaps in his tables: gallium, which was discovered in 1875 (and is present in his 1879 table); and germanium, which was isolated in 1886. As you can see, Mendeleev's predictions were very good!

*Low enough to melt on a hot day

But that's not all. Gallium was discovered by Paul Emile François Lecoq de Boisbaudran, a Frenchman (obviously) who named the element using the Latin (Gallis) for the ancient name of his country (Gaul). As Kean tells it, in his bestselling book The Disappearing Spoon,6 Mendeleev sought to steal some of Lecoq's thunder by claiming that he, Mendeleev, was really responsible for the discovery of gallium, having predicted its existence. Lecoq fought back, claiming that another Frenchman had developed the periodic table much earlier. Mendeleev pointed out that Lecoq's measurements of the properties of gallium had to be in error because they didn't agree with Mendeleev's predictions. (That was really a lot of gall for a Russian!) Lecoq eventually found that Mendeleev was right, withdrew his original data, and published results that did, indeed, agree with Mendeleev's predictions. As Kean phrased it, “The scientific world was astounded to note that Mendeleev, the theorist, had seen the properties of a new element more clearly than the chemist who had discovered it.”7

It is from the properties of gallium that Kean gets the title of his book, The Disappearing Spoon. He relates how chemists would play practical jokes by crafting a spoon of the silvery metal and then serving hot tea by pouring hot water into a cup with the spoon in it. The melting point of gallium is so low that the metal transforms from solid to liquid in hot water. So the spoon would “disappear” before the guest's eyes as it melted into the bottom of the cup.

Fig. B.1. Dmitri Mendeleev at middle age. (Image from AIP Emilio Segre Visual Archives.)

Mendeleev—Teacher, Scientist, Maverick, Showman

We get a sense of the science and society of the times by examining the life of Dmitri Mendeleev, who shaped not only science but also thought and policy in tsarist Russia. He was a promoter intent on improving Russia, and, in the process, in elevating his position within the autocracy of the tsarist state. He entered into Russian society in 1861, the same year that the serfs were emancipated under the beginning of Tsar Alexander II's “Great Reforms.” And Mendeleev soon became a powerful figure with close ties to several government ministers and access to the tsar.

Though a political conservative, Mendeleev sought to modernize Russian institutions and Russian science, and he spent as much of his time trying to improve the Russian state as he did working in the sciences. He sought methods for organizing industry and human resources, helped to create the protectionist tariff of 1891, published critiques in the arts, and sat in séances as part of an ongoing personal effort to debunk a widespread spiritualism. He consulted throughout his life in practical technical areas ranging from cheese manufacturing to production in iron, coal, and oil; set the standards for alcohol content in vodka; initiated the first “big science” projects and introduced the metric system in Russia; promoted meteorology through his own balloon ascents; and was the foremost contributor to the development of the periodic table of the chemical elements.

Despite being honored around the world, Mendeleev did not receive the Nobel Prize. The prize had been established in 1901, and he was put forward as a candidate in 1906, but an old grudge from an earlier scientific dispute interfered. There is no doubt that his work was of Nobel Prize caliber. (Had he lived long enough, it would surely eventually have been awarded to him, but, as I've mentioned before, it is awarded only to living scientists.) To quote Scerri: “He is the leading discoverer of the (periodic) system…. His version is the one that created the biggest impact on the scientific community at the time…. His name is invariably and justifiably connected with the periodic system, to the same extent as Darwin's name is synonymous with the theory of evolution and Einstein's [is] with the theory of relativity.”8 One of the craters on the moon, as well as element number 101, the radioactive mendelevium, are named in his honor.

MUCH OF CHEMISTRY ON A SINGLE PAGE

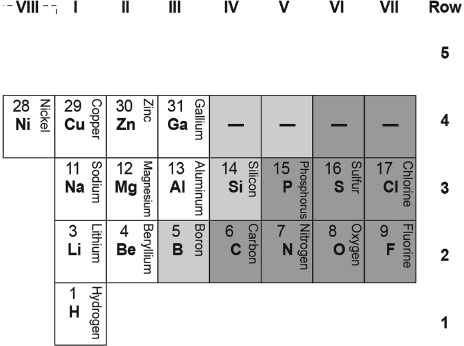

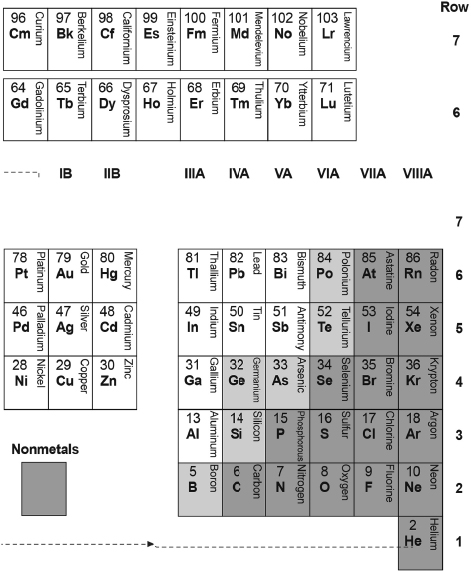

For later reference, I show in Table B.2 one commonly used modern long-form periodic table of 103 of the 118 elements. For reasons that will become apparent, I display this table “flipped” upside down, as I had done with Mendeleev's 1879 table (Table B.1 above).

I have incorporated Mendeleev's table almost as it is shown into Table B.2, just shifting the block of elements H, Li, and Na, and Be and Mg from the right Groups I and II columns to the left Groups I and II columns. Otherwise, to complete this periodic table, I have filled in Mendeleev's blanks, completed the labeling of the groups, added three more rows of elements, and added a rightmost Group VIII-A column for the noble gases discovered after 1879.

For now, we just note Scerri's general comment: “The periodic table of the elements is one of the most powerful icons in science: a single document that captures the essence of chemistry in an elegant pattern. Indeed nothing quite like it exists in biology or physics, or any other branch of science for that matter.”9

Table B.2. A Modern Arrangements of the Periodic Table of 103 Elements (Same as Table IV).

**Actinide Series (Insert the entire row after Ac, Z = 89 below)

**Lanthanide Series (Insert the entire row after La, Z = 57 below)