Now an understanding of the elements, their various properties, essentially everything that we see around us, is within our grasp! We use the states of the electron in hydrogen as a guide in a progression through four related tables. These are unusual tables. They don't contain boring data. Their contents are broken down into sections that have physical meaning. And one table flows to the next until (voilà) in the fourth table we have a modern periodic table of the elements! And we have achieved this through a progression that simply reveals the atomic structure of the elements as we progress easily from what we already know about the hydrogen atom.

Before proceeding with this chapter, it's best to get an overview first. For this I ask you to just scan to get a “snapshot” of each of the tables (to facilitate this scan, and for easy reference, I would suggest—if it is convenient for you to do so—that you make a separate copy of each of the tables.) When you have finished this scan, glance at the short notes about each table on the page that immediately follows them. This will be like fanning through a succession of slightly changed cartoon pages to get the effect of a motion-picture show.

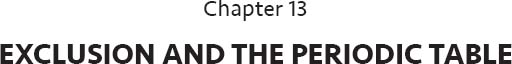

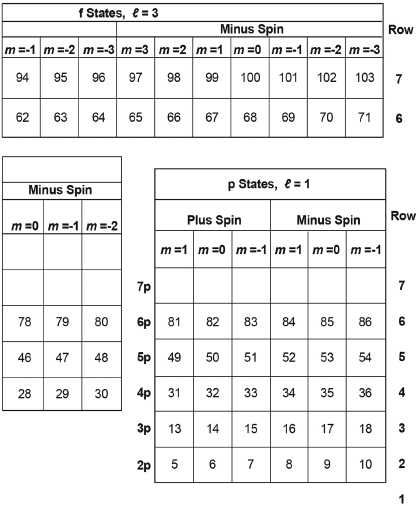

Table I. Properties of 128 of the Lowest Energy Combined Spin and Spatial States of the Electron in the Hydrogen Atom.

Each square marks a state, with energy, angular momentum, and spatial and spin and column in which it is located States for energy levels n = 4 and n = 5 of the magnetic moments as indicated by the quantum numbers of the row f block of states are shown separately at the top of this table.

Unlike those shown in Figure 3.8, the probability cloud cross section representing some of the states here do not show relative size. (They have been taken from Figure 5-5 of leighton, Reference F, with permission from maragaret L. Leighton.

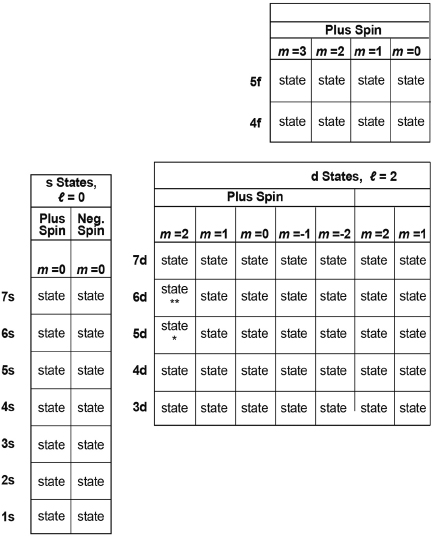

Table II. Properties of 128 of the lowest Energy States for the Electron in a Generic Many-Electron Atom.

**Insert this entire row into Row #7 after the **state below.

*Insert this entire row into Row #6 after the *state below.

The labels to the left of the blocks correspond to the original energy levels and angular momenturn of the comparable states for the electron in the hydrogen atom, as displayed in Table I.

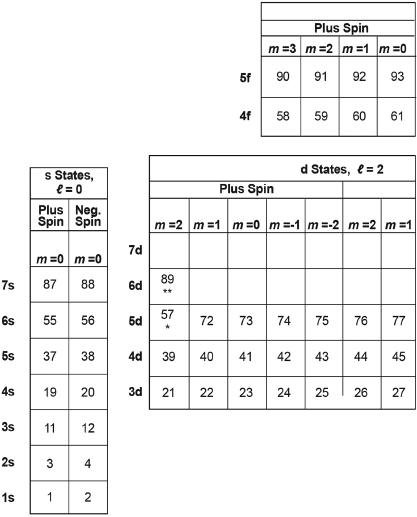

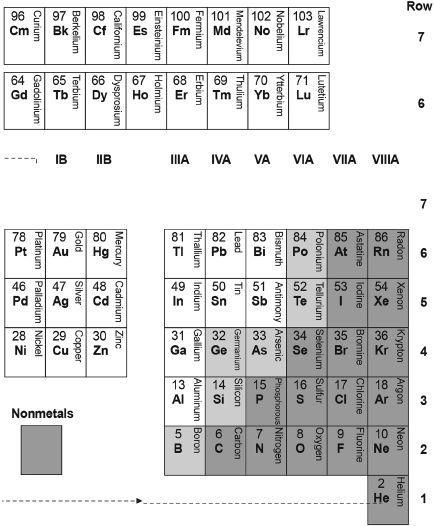

Table III. Expected Outermost Occupied Electron State for the Atom of Each Element, as Marked by Its Atomic Number.

**Insert this entire row into Row #7 after Element #89 ** below.

*Insert this entire row into Row #6 after Element #57 ** below.

The labels to the left of the blocks correspond to the original energy levels and angular momenturn of the comparable states for the electron in the hydrogen atom, as displayed in Table I.

Table IV. A Modern Arrangement of the Periodic Table of 103 Elements (Same as Table B.2).

** Actinide Series (Insert the entire row after Ac, Z = 89 below)

** Lanthanide Series (Insert the entire row after La, Z = 57 below)

Table I is a set of squares, each of which represents one of the 128 lowest-energy states of the hydrogen atom—starting with the states of lowest energy in the bottom row. The various rows, columns, and four groups organize these states according to their energy, angular momentum, and spin properties. The cloud cross sections for forty of these states are shown in some of the boxes.

Table II represents the tables of states of all of the rest of the elements. Each will have its own table, but the tables are somewhat similar, and so we represent them all with this one generic table. No cloud cross sections are shown, because these will be somewhat different for the atoms of each element, and only somewhat changed from those shown for hydrogen in Table I. For reasons that will be described, the d block of states in the middle is raised upward by one row to higher energy, and the f block is shifted upward by two rows, as compared to the position of these blocks in Table I.

Table III just numbers the states of Table II from left to right across each row—starting with the bottom row. Each number marks the last state that would be occupied in a table of states for an atom with that atomic number, that number of electrons. This assumes that the electrons of that atom will successively occupy the lowest energy states, one electron per state, starting with the state at the left end of the first row, and then successively filling states to the right in that row and then up to the left end of the next row, and so on.

Table IV is just Table III with the name of each element added into the square (now stretched to a rectangle) where its atomic number appears—and with Roman-numeral “group” labels for the columns inserted above the lower blocks of elements. And, as noted above, voilà! Now we have a modern periodic table of the elements!

If you were to flip Table IV bottom to top, it would take on a more familiar form, with the lightest elements shown in the first row and the heaviest elements at the bottom. And remember, Table III gives us the spin and spatial state of the outermost electron for each of the elements shown in Table IV. We'll see how that state affects the properties of each element.

In the rest of this chapter I'll describe more fully the three steps from Table I for the hydrogen atom to the periodic table (Table IV). And we'll see how Table III reflects the degree to which the p states at each energy level are occupied and how, for every element, this determines its chemical properties. Then in Chapter 14 we'll see what is happening inside the atom as we consider heavier and heavier elements with more and more electrons. First let's consider our tables, and then I'll describe a bit more about the progression to a periodic table that I have just outlined.

THE HYDROGEN ATOM AS A GUIDE TO THE ATOMS OF THE REST OF THE ELEMENTS

We start with Table I, a concise summary of the properties of 128 of the infinity of states available to the electron in the hydrogen atom. These 128 are the states with the lowest levels of energy and angular momentum (those states most likely to be occupied by the electron, recognizing, again, that things in nature tend to occupy a lower- or the lowest-energy state). Table I has the following features:

- Each square marked “state” represents one unique state that the electron may occupy. Each state has a unique set of properties noted by the four quantum numbers for that state.

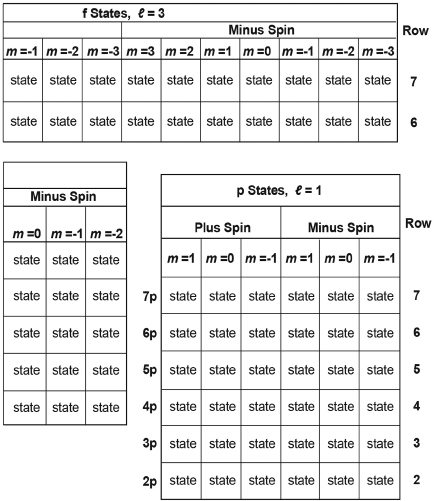

The states are grouped into four major blocks. Considering each block successively from left to right and then up: the first block contains those squares marking s-states, states with angular momentum indicated by the quantum number ℓ = 0; the second block contains those squares marking d-states, states with angular momentum indicated by the quantum number ℓ = 2; the third block contains those squares marking p-states, states with angular momentum indicated by the quantum number ℓ = 1; and the fourth block above contains those squares marking f-states, states with angular momentum indicated by the quantum number ℓ = 3.

- Each block is divided into block halves, with the left half containing squares that mark those states with plus spin, and the right half marking those states with minus spin.

- Each half of each block is divided into columns, with each column indicating a magnetic quantum number m = 0, 1 or –1, 2 or –2, and so on, of the states within that column; note that each m value represents the component of angular momentum that would align parallel (or antiparallel) to the direction of a magnetic field.

- Finally, each row of the table (numbered at the right of the table) indicates the corresponding principal quantum number, n = 1, 2, 3, 4, and so on (shown at the left side of the table); note that each n represents the energy level of all states within that row.

- To indicate some of the variety of forms of the probability clouds of the various states, forty of the “state” labels have been replaced by the probability-cloud cross sections for those states. (All of these cloud cross sections have been magnified differently so that they just fill the squares. The relative sizes of five of these cross sections, all under the same magnification, are displayed in Figure 3.8.

CLUES TO THE CHEMISTRY OF THE ELEMENTS IN A GENERIC TABLE OF STATES

Next consider generic Table II, which (in a manner similar to Table I for hydrogen) represents the states and properties available to electrons in atoms having more than one electron. The similarity between these two tables results mainly because Schrödinger's solutions for the states of the many-electron atom are much the same as those found for the hydrogen atom.

However, Table II differs from Table I in three ways. The first difference results from a difference in the physics and is of fundamental importance, as described immediately below.

- Note that the entire d block of states in Table II has been raised one row (one energy level) higher than the d block in Table I, and the entire f block has been raised two rows (two energy levels) higher. These shifts result because of a physical interaction that is present in the many-electron atom but not present in the hydrogen atom. In the many-electron atom, each electron, wherever it may be in its probability cloud, is screened from the attraction of the positively charged protons of the nucleus by the negative charge of each of the other electrons, to the degree that the probability clouds of these other electrons lie closer to the nucleus. So, those states that on average lie farther out and are more screened are attracted less, have higher (less negative) energies and are less tightly bound. Specifically, the d states are more screened and have less negative energies, and so the d block of states is higher in energy (and in the table) than the s and p blocks of the same n, and the f block of states is similarly higher in energy than the d block of states.

- The second difference between the tables is in the labels to the left of each block of states in Table II. These labels correspond to what were the original energy level and angular momentum of each row of states before the shift, and to the comparable rows of states for the electron in the hydrogen atom. For example, the bottom row of the d block, now in the fourth row of Table II, is labeled as 3d, because these states are somewhat like the hydrogen states in the third row of the d block in Table I.

- Finally, no probability-cloud cross sections are shown in Table II. That is because a particular state (say n = 2, ℓ = 1, m = 0, plus spin) of the atom of one element is somewhat different from a state with the same quantum numbers in an atom of another element, and their cloud cross sections are somewhat different. Since this is a generic table, pertaining to all many-electron atoms, it would be inappropriate to show the cloud cross sections of the states of the atom of any particular element. We can get some idea of what these states may look like by examining the cross sections of comparable states for the electron in hydrogen, as shown in Table I.

So, we have all of these states with all of their associated properties. So what? Surprisingly (as you will soon come to see) much of an understanding of the chemistry of each element comes from simply counting the number of states occupied by electrons at each energy level in its atoms.

For starters, note that Row #1 of Table II has just 2 states in it; Row #2 has 8; Row #3 has 8; Row #4 has 18; Row #5 has 18; and Row #6 has 32, including those states in Row #6 of the f block of states at the top of the table. This “2, 8, 8, 18, 18, 32” sequence is exactly that found for the number of elements between “inert” elements as one counts through the elements in order of atomic weight or atomic number. And this correlation is not a coincidence, as will become clear as we proceed.)

ANTISOCIAL BEHAVIOR (EXCLUSION)

Now we discuss something that is fundamental to our understanding of the properties of the atoms of all of the elements after hydrogen, and fundamental to our understanding of the arrangement of the periodic table.

Remember that exclusion was originally postulated by Wolfgang Pauli, in what is now known as the Pauli exclusion principle, to help Bohr use his model of the atom to explain the elements and the periodic table. That was just a postulate. Since then, scientists have shown exclusion to be a fundamental property of electrons.

As it happens, particles have states described either by symmetrical or antisymmetrical wavefunctions. (Symmetry is in the mathematics, beyond the scope of explanation here. But the results of the math are profound!) Those particles having symmetrical wavefunctions all have integral or zero spin and are called bosons. (Remember the fundamental bosons of the Standard Model described in Chapter 9.) Bosons may all occupy the same state. Those particles having anti-symmetric wavefunctions all have half integral spin and are called fermions particles. (Again, remember the fundamental fermions described in Chapter 9.) Indistinguishable fermions cannot occupy the same total state. They stay away from each other. (All of this is observed to be so.) The electron is a fermion (actually, a fundamental fermion).

Recall from Chapter 12 Dirac's calculation that the electron has an intrinsic angular momentum, called spin, with values of either +½ or –½ times one basic unit of angular momentum. Electrons have half integral spin! Note also that the wavefunctions describing the spatial states of the electron are fuzzy and spread out. Electrons are intrinsically indistinguishable because they are the same kind of particle. And so, no two electrons can be in the same total state, that is, be in a place where their wavefunctions substantially overlap (in our visualization, but also mathematically), have the same energy, have the same spatial-state angular momentum, have the same magnetic component of the angular momentum, and have the z component of their spins in the same direction (i.e., both +½ or both –½) at the same time. If all of their other properties are the same, electrons can't be in the same place, and so they stay away from each other. This is exclusion.

We will now see how very important exclusion is in explaining the structure and properties of atoms having more than one electron.

HOW EXCLUSION WORKS IN EACH MANY-ELECTRON ATOM

Each atom, like hydrogen, has its own set of an infinite number of quantized states that its electrons may occupy. (The properties of 128 of these states have been represented in a generic way in Table II.) Complicated as each electron spatial state may seem from the appearance of its electron cloud, by the very nature of its being a solution of the Schrödinger equation, even in a multielectron atom, each state (mathematically) overlaps no other spatial state. And so electrons in the atom of an element can stay away from each other by being in separate spatial states.

The number of electrons in the atom of each element is by definition the atomic number of that element. So, for example, hydrogen has one electron, helium two, oxygen eight, neon ten, argon eighteen, and so on. And each electron, like most things in nature, tends to occupy the lowest energy state that it can in the atom of its particular element. However, because of exclusion, no two electrons can occupy the same total spin and spatial state in the same atom. So, the electrons tend to occupy, successively, the lowest energy state of each atom, and then the next lowest, and so on, one electron per state. The one electron in hydrogen tends to occupy its lowest energy state; the two electrons in helium tend to occupy the lowest and then the second lowest of the energy states for helium, and so on. Importantly, the chemical behavior of each element is determined largely (as we will see) by the last state to be occupied in its atom, and by the next lowest energy state that may be available for occupancy in that atom.

POPULATING THE STATES OF THE MANY-ELECTRON ATOM

Now we can see what states are occupied by the electrons in the atoms of the various elements (and eventually what that means for the properties of those elements). We proceed as follows, with reference to Table II.

There is some detail in the following numbered paragraphs. But in these specific examples we begin to show how quantum physics manifests itself in the properties of the elements and in the emergence of the periodic table. So please read with patience. The importance of this information will become clear later on.

(1) An electron tends to be in the lowest energy state available to it. Thus the overall ground state of the atom of each element results from the occupation by its electrons of the states of lowest energy for that atom, to the extent that those occupations are allowed by exclusion. An atom is usually found in this ground state.

(2) The single electron in a hydrogen atom, atomic number Z = 1, occupies either the [1s, +spin] or the [1s, –spin] state in the table for hydrogen; let's say the [1s, +spin] state located at the bottom left of Table I or Table II.

(3) For atoms with additional electrons (because of exclusion) no two electrons can occupy the same total (spatial and spin) state.

(4) So the first of the two electrons in a helium atom, atomic number Z = 2, occupies the lowest energy, [1s, +spin], state and then the second electron occupies the next lowest energy [1s, –spin] state in the helium atom's table of states represented by the generic Table II. This completes the occupation of the lowest (most-negative) energy states in the first (bottom) row of the table; what is called the 1s first “shell” of helium states for the helium atom. And helium is consequently inert and interacts with no other elements, as will be explained later in this chapter.

(5) The three electrons in a lithium atom, atomic number Z = 3, occupy its [1s, +spin] state, its [1s, –spin] state, and then its next lowest energy [2s, +spin] state in its table of states for lithium (again, represented by generic Table II). And the four electrons in a beryllium atom, atomic number Z = 4, occupy these three of its electron states plus the [2s, –spin] beryllium state in its table of states (again, represented by generic Table II), completely filling the 1s shell and the 2s “subshell” part of the second row of states). (Note that a subshell is filled whenever all of the states within a given row of either an s, p, d or f block are filled.)

(6) Continuing with the five electrons of the Z = 5 boron atom, we see that its states are occupied up to and including the first of its plus-spin 2p states in the second row of a table for the boron atom.

(7) For the Z = 6 carbon atom and the Z = 7 nitrogen atom additional plus-spin, 2p states are occupied in their respective tables of states, each represented by our generic table of states, Table II.

Note that in each block of states at each energy level, all states of plus spin tend to be occupied before the beginning of the occupation of states having minus spin. That is because as soon as we begin occupying both plus-spin states and minus-spin states having the same n, ℓ, and m quantum numbers, we have two electrons spatially virtually on top of each other. Because these electrons each have a charge of –e, they tend to repel each other but are otherwise trapped in their identical spatial-state clouds. This repulsion causes an increase in energy, and nature likes energy to be low and avoids such an increase as long as possible. So the electrons seek, subject to exclusion, to first populate within each block only a sub-block of either plus or minus spin. Consistent with our understanding that the lower energy states in any given row occur toward the left of the row, we have the plus-spin states populated first.

(8) And so it is that oxygen, for example, with atomic number Z = 8 and the first occupancy of a negative-spin 2p state (because it experiences the first population of a p block spatial state with electrons of both plus and minus spin), has some peculiar chemical properties relative to what might otherwise be expected (as will be discussed in Appendix D and Chapter 15).

(9) Skipping ahead, we find that the states of the Z = 10 neon atom are occupied by its ten electrons up to and through the entire 2p subshell, that is, through the entire second-row shell of states for the neon atom. (And that is why neon is inert, as will also be discussed later in this chapter.)

(10) We continue with the filling of states for the atoms of the rest of the elements. In some cases the subshells and shells for those atoms are “just” completely filled with electrons. Those elements whose atoms have a just-filled subshell or shell have special properties (as we have already noted for helium and neon), as do those whose atoms begin to fill otherwise-identical states with opposite spin (as we have already noted for oxygen).

MARKING THE LAST OCCUPIED STATE TO CREATE A PERIODIC TABLE

For each element, we can mark the position of the state that is last filled with an electron by inserting the atomic number of that element into the square of Table II for that last-filled state. The result, if we do this for all of the elements, is Table III (which otherwise resembles Table II.) It would remain then only to: (a) add the corresponding name and symbol for each element to each square of Table III and (b) move the second square from the left in the bottom row (for helium, Z = 2) to the far right to create our periodic table, Table IV (shown also as Table B.2 of Appendix B). The move of the square for helium is shown by the arrow at the bottom of Table IV. (The reason for this move will become clear shortly.)

THE ELECTRONIC STRUCTURE AND CHEMISTRY OF THE ATOMS OF THE ELEMENTS

Table IV, our periodic table, was created as described in Appendix B initially as an arrangement of the elements sequentially in rows according to their atomic numbers and in columns by their empirically determined chemical properties. Table III, by contrast, has been created by marking the final occupancy of states of higher and higher energy levels (across sequentially higher rows) across blocks of states of particular angular momentum, sub-blocks of particular spin, and columns of the component of angular momentum that would align parallel to a magnetic field. The similarity of these tables reflects the linkage between the observed chemical properties of the elements (described in Table IV) and the theoretically derived occupied electron-state structure of their atoms (described in Table III).

Table III, of course, was put together through a semiquantitative understanding of the quantum mechanics of the many-electron atom. But the prediction from Table III of which type of state (s, p, d, or f), and how many states of each type, are occupied in the atom of each element is in good agreement with the predictions made in more sophisticated ways.1

Experiment has shown that our predictions are 100 percent accurate for 66 of the 75 elements in the lower three blocks of the tables! And the predictions are close to being accurate for the remaining 9 of these elements, all of which lie in the central block containing the (so-called) transition metals, in which some of the d states are populated before both s states are populated. The situation is more complicated for the elements in the upper f block of the tables, where the energies of the last-filled of the various types of states are not as distinctly separated and some of the 4f and 5f states are populated before all of the 4d and 5d states are populated. In spite of these differences, overall, our crude method of projecting the electronic structure of the elements from what we know of the hydrogen atom has been remarkably successful.

THE NOBLE GAS ELEMENTS

We now examine particularly the electron structure of the inert elements, the noble gases (those elements in the last column in both tables). The noble gases are among those elements for which our projection of the occupation of states has been shown by experiment to be 100 percent accurate.

We know that the atom of each element (labeled in Table III only by its atomic number) consists of electrons that occupy, one per hydrogenlike state, all of the states shown in all of the squares up to that point in its equivalent of Table II. Now (remembering that we represent the atomic number of each element generally by the letter Z), we note particularly that the square second from the left at the bottom of Table III marks the filling of both of the 1s states in the atom of the element helium, Z = 2.

As will be discussed more later, this filling of both states in the lowest-energy-level first row, results in a highly compact atom with its electrons so tightly bound that they cannot be pulled loose by other atoms. Nor does the helium atom seek to gain an electron by combining with the atoms of other elements. That is because the two positive charges of the protons in the helium atom's nucleus are almost entirely shielded by the negative charges of its two electrons, so that the nearest unoccupied state that the new electron might go into is only very slightly negative in energy and doesn't attract and hold an electron. Helium, thus, as observed, tends to be inert and to combine with no other elements. So in helium we have the complete filling by its two electrons of what we call the first shell of states.

The atoms of all of the elements down the rightmost column of Tables III and IV, with atomic numbers Z = 10, 18, 36, 54, and 86, all have completely filled shells in which the electrons are similarly expected to be relatively tightly bound (as will be discussed further in Chapter 14). These shells also almost completely shield the positive charge of the protons in the nucleus so that they do not attract additional electrons. These, the rest of the noble gases, might also therefore be expected to be inert. But, as one considers the heavier of these noble gases, those elements of higher atomic number, their outer electrons, though completing a shell, are less and less tightly bound. These outer electrons can be stripped away by such highly acquisitive elements as fluorine and oxygen. So these heavier noble gases are not inert. Regardless, from the filling of states in Table III (subject to further discussion in Chapter 14), we have answered the questions posed earlier as to why elements with atomic numbers Z = 2, 10, 18, 36, 54, and 86 tend to be inert, and why we have the curious spacings of the number of elements before or between the listings of these noble gases in Table IV, that is, we have answered why the numbers of elements in the first six rows of the periodic table are 2, 8, 8, 18, 18, and 32.

Now we can also understand why I've moved the square for helium, Z = 2, from the left to the right side of Table IV, as shown by the arrow at the bottom of the table. The helium atom has a completely filled shell of states, just as do the atoms of the rest of the noble gases listed in the last column of this table. (But to keep the electron structure straight, we must remember that both electrons in helium are in an s state, despite helium's listing in the otherwise last-filled p state Group VIIIA column of Table IV.)

ELECTRON STRUCTURE AND CHEMICAL BEHAVIOR OF ATOMS CLASSIFIED IN “GROUPS”

Now we begin to see how the occupation of states by electrons in atoms explains the chemical properties of the elements. To start with, note that the total number of electrons acquired or shared by one or several atoms when they react (combine) to form a compound is always equal to the number of electrons that are taken away from or shared by one or several others.

So, for example, for the compound water, H2O, two hydrogen atoms each give up or share one electron to combine with one oxygen atom, which acquires or shares two electrons to completely fill its p subshell and its n = 2 shell of states. The organized listing of elements whose atoms tend to acquire or give up electrons is inherent in the layout of Table IV and is called out in the labeling of its columns.

The strength toward acquisition is highest for atoms of those elements shown in the bottom rows and (except for the last column) to the right of the tables, in those squares that are darkly shaded. It is the nearness to a completely filled (lowest-energy-configuration) shell that makes these elements particularly active in acquiring an electron or electrons. These are the nonmetals. (As an example, note that atoms of fluorine [F, Z = 9, at the bottom of the Group VIIA, second from the right column] are so reactive that they displace oxygen from water to form hydrofluoric acid, HF, which is so reactive that the fluorine in it will further rip silicon [Si, Z = 14, second from the bottom in the much less acquisitive Group IVA column] from oxygen in SiO2 to etch glass.

Conversely, atoms having one more electron than fills the row of a p block (called a valence subshell) want to be in a just-filled valence subshell configuration and tend to react strongly to lose that last electron. That is because the electron outside of the filled subshell is largely shielded from the attraction of the nucleus by the smaller, essentially spherical, ball of negative charge of the filled subshells within. The elements having these kinds of atoms are marked in the first column of Table III and are listed in the first, Group IA, column of the periodic table. The elements whose atoms have two extra electrons beyond the filled subshells tend to less aggressively try to lose these electrons and are marked in the second column of Table III and are listed in the Group IIA second column of the periodic table. The tendency of atoms of all of the elements to shed electrons increases with their location farther up and to the left in the tables.2 Those elements that tend to lose electrons are shown without shading in Table IV. They are classified as metals because they show this tendency. They have what we know as metallic properties: electrical conduction, luster, and (usually) malleability.

(As one familiar example of a reactive metal, consider sodium [Na, Z = 11, third from the bottom in the leftmost Group IA]. We know sodium from its combination with chlorine to form sodium chloride, NaCl, common table salt. Sodium is a malleable metal, an electrical conductor with metallic luster. But thrown into water, sodium will rip one oxygen along with one hydrogen atom from the other hydrogen atom to produce sodium hydroxide, NaOH. If enough sodium is present, this will create a violent reaction with heating and steam, releasing hydrogen to possibly ignite and burn again or even explode, should it accumulate in sufficient concentration and come into contact with the oxygen in the air. Potassium [K, Z = 19] will displace the sodium from NaOH, and so on. Going the other way, down the first column, lithium and hydrogen are not so reactive; and beryllium, at the bottom of the Group IIA, alkaline earth metals column, is only reluctantly metallic. We don't think of hydrogen as a metal because we see it mainly as a gaseous element that doesn't display metallic properties; however, theoretically, under enough pressure and at low-enough temperatures, hydrogen may be solid and display the properties typical of a metal.)

The atoms of a few of the elements in the first four columns in the p block of Table III and shown lightly shaded in a diagonal from bottom left to top right across the Group IIIA, IVA, VA, and VIA columns of the periodic table, have properties that lie “in between” those of the metals and those of the nonmetals, as will be discussed in later chapters. These are known as metalloids or semiconductors. (We are familiar with silicon and germanium and their use in modern electronics.)

The letter B after the Roman numerals labeling the columns across the left–center of the periodic table refers to the additional groups (columns) that occur when electrons occupy d states after s states outside of a completed p block subshell. The elements in these groups are the transition metals. (Among these are iron, nickel, and chromium, which are used to make steels, and some of the elements sometimes found in their uncombined metallic state and known since ancient times: copper, silver, and gold.)

The Row #6 f block of lanthanide elements shown near the top of the table, also known as the rare earths, is to be inserted into the Row #6 transition metal series, after lanthanum, Z = 57. The Row #7 f block of actinide series elements shown at the top of the table, also known as heaviest elements, is to be inserted into the Row #7 transition-metal series, after actinium, Z = 89. (Among these are radioactive uranium and plutonium, familiar to us through their use in the production of nuclear power and weaponry.)

As discussed earlier, the s and d (and in Rows #6 and #7 also f) electron states in some of the elements across the B-type groups (columns) in each row may have nearly comparable energies, so that the order of their occupancy is not as clearly given as for elements in the A-type groups. And, despite their similar Roman numerals, the electronic makeup and properties of the atoms of the elements in the similarly numbered A-type and B-type groups may sometimes be quite different in their properties. The B groups contain three more columns of elements than do the A groups, accommodated by having all three of the columns in the center of Table IV labeled as VIIIB. None of the elements in these Group VIIIB columns bear any resemblance to the noble gases of Group VIIIA. Note particularly that the lightest transition elements in these three columns of Group VIIIB, those in Row #4, are iron, cobalt, and nickel, which all tend to be magnetic.

(More is described of the transition elements in Appendix D. However, Appendix D is best read in light of the physical picture of what goes on in the many-electron atom, as presented next.)