Musée d’Orsay

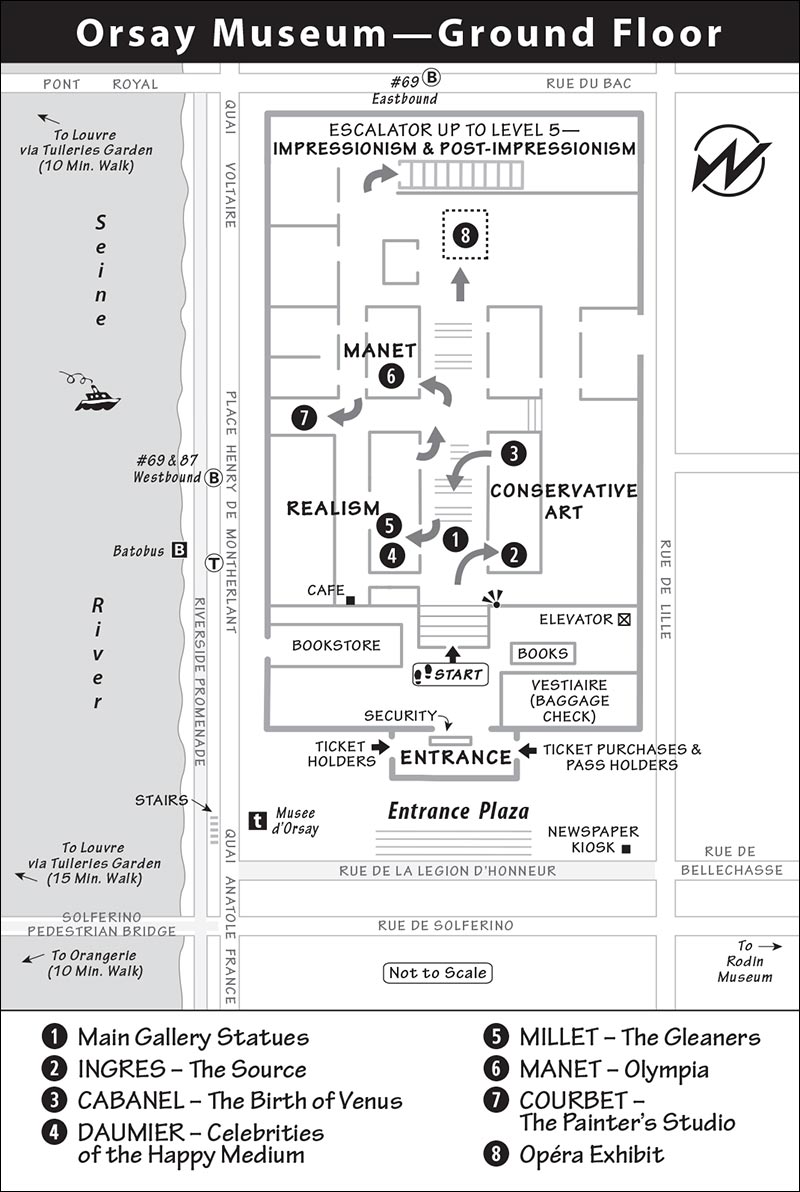

Map: Orsay Museum—Ground Floor

GROUND FLOOR-REALISM, EARLY REBELS, AND THE BELLE EPOQUE

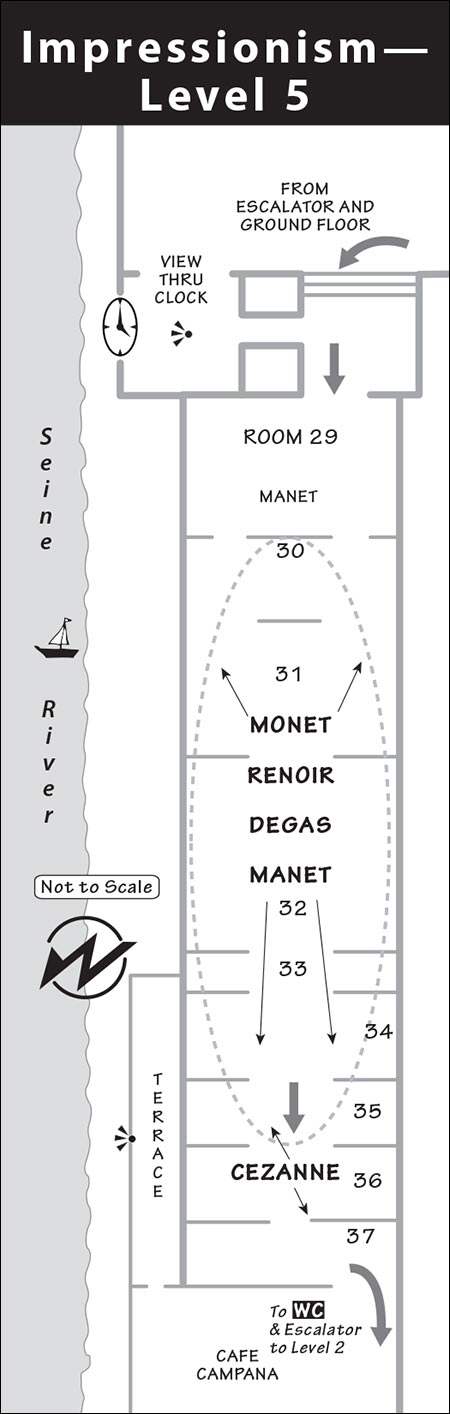

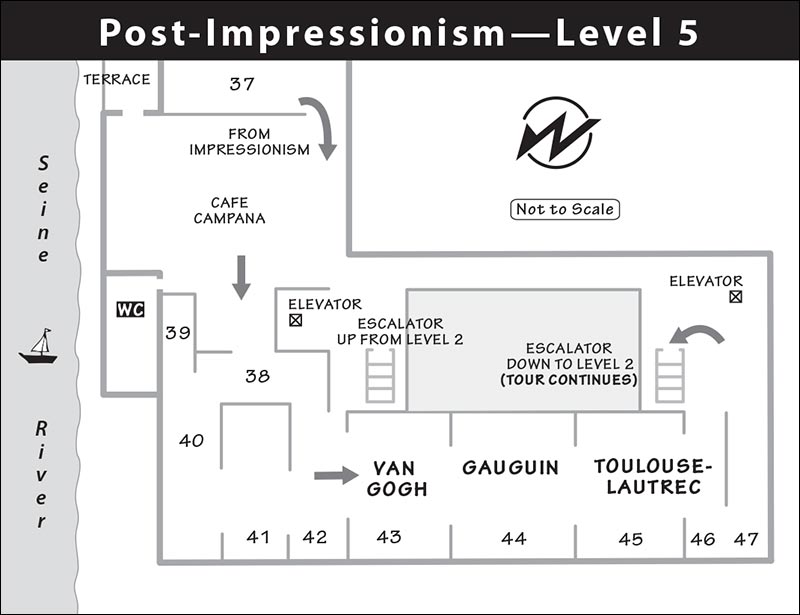

Map: Post-Impressionism—Level 5

The Musée d’Orsay (mew-zay dor-say) houses French art of the 1800s and early 1900s (specifically, 1848-1914), picking up where the Louvre’s art collection leaves off. For us, that means Impressionism, the art of sun-dappled fields, bright colors, and crowded Parisian cafés. The Orsay houses the best general collection anywhere of Manet, Monet, Renoir, Degas, Van Gogh, Cézanne, and Gauguin. If you like Impressionism, visit this museum. If you don’t like Impressionism, visit this museum. I find it a more enjoyable and rewarding place than the Louvre. Sure, ya gotta see the Mona Lisa and Venus de Milo, but after you get your gottas out of the way, enjoy the Orsay.

Keep in mind that the collection is always on the move—paintings on loan, in restoration, or displayed in different rooms. The museum updates its website daily with the latest layout, so with a little flexibility, you should be able to see most of the Orsay’s masterpieces.

Cost: €16, free on first Sun of month (but timed-entry ticket required), covered by Museum Pass, combo-tickets with the Orangerie (€20) or Rodin Museum (€24)—visit these less-crowded sights first to purchase combo-ticket; keep ticket for discount at the Opéra Garnier (within 5 days of Orsay visit).

Hours: Tue-Sun 9:30-18:00, Thu until 21:45, closed Mon, last entry one hour before closing (45 minutes on Thu). The top-floor Impressionist galleries begin closing 45 minutes early, frustrating unwary visitors.

Information: +33 1 40 49 48 14, www.musee-orsay.fr.

When to Go: For shorter lines and fewer crowds, visit on Wed, Fri, or Thu evening (when the museum is open late). You’ll battle the biggest hordes on Sun, as well as on Tue, when the Louvre is closed.

Avoiding Lines: While everyone must wait to go through security, avoid the long ticket-buying lines with a Museum Pass, a combo-ticket, or by purchasing tickets in advance on the Orsay website; any of these entitle you to use a separate entrance.

You can also buy tickets and possibly Museum Passes (no mark-up; tickets valid 3 months) at the newspaper kiosk just outside the Orsay entrance (along Rue de la Légion d’Honneur).

Getting There: The museum sits at 1 Rue de la Légion d’Honneur, above the Musée d’Orsay RER/Train-C stop. The Solférino Métro stop is three blocks southeast of the Orsay. Bus #69 from the Marais neighborhood stops at the museum on the river side (Quai Anatole France); from the Rue Cler area, it stops behind the museum on Rue du Bac. From the Louvre, catch bus #69 along Rue de Rivoli. Bus #87, running west from the Marais, shares a riverside stop with bus #69; the return stop eastbound is along Rue du Bac.

From the Louvre or Orangerie museums, the Orsay is a lovely walk through the Tuileries Garden and across the river on the pedestrian bridge (15 minutes from the Louvre, 10 minutes from the Orangerie). A taxi stand is in front of the entry on Quai Anatole France. The Batobus boat stops here (see here).

Getting In: The Orsay’s entrance will be under renovation at least until mid-2025, so expect some changes to the following entry procedure. As you face the entrance, ticket holders enter on the left (Entrance A). Ticket purchasers and Museum Pass holders enter to the right, where there’s a separate line for each (Entrance C). Security checks slow down all entrances.

Tours: Audioguides cost €6. English-language guided tours are available; confirm times and book online—usually Tue-Sat at 11:00 (€10/1.5 hours, may also run at 14:30).

Download my free Orsay Museum audio tour.

Download my free Orsay Museum audio tour.

Length of This Tour: Allow two hours. With less time, focus on the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists on the top floor.

Cloakroom (Vestiaire): Checking bags or coats is free (look to the far right, before the ticket checkers). Day bags (but nothing bigger) are allowed in the museum. No valuables can be stored in checked bags (the clerk might ask you in French not to check cameras, passports, or anything particularly precious).

Cuisine Art: The très elegant $$$ Le Restaurant on the museum’s second floor is worth a peek just to admire the grand setting and lovely views. In addition to lunch (served Tue-Sun 11:45-14:35), an affordable tea and coffee service is available daily (15:00-17:30) except Thursday, when dinner is served (19:00-21:00). Stylish $$ Café Campana serves simpler meals to crowds on the fifth floor beyond the Impressionist galleries (Tue-Sun 10:30-17:00). The reasonably priced self-service $ Café de la Gare is on the ground floor under the bookstore. Outside, behind the museum, several classy eateries line Rue du Bac. If the weather is even close to good, drop down to the riverside promenade just below the museum, where you’ll find food stands and more (closed in winter).

Starring: Manet, Monet, Renoir, Degas, Van Gogh, Cézanne, and Gauguin.

• Pick up a free map at the booth inside the entrance and belly up to the stone balustrade overlooking the ground floor.

Trains used to run right under our feet down the center of the gallery. This former train station, the Gare d’Orsay, barely escaped the wrecking ball in the 1970s, when the French realized it’d be a great place to house the enormous collections of 19th-century art scattered throughout the city.

From this perch, survey our tour route. We’ll do two laps around three floors of this grand museum: Stretching before you on the ground floor is conservative art of the Academy and Salon, with some early rebels mixed in. At the far end, we’ll ride escalators to the top floor, where we’ll enjoy the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists like Van Gogh (if you’re pressed for time, go directly there). Then, we’ll descend to the mezzanine level for a wander through Rodin’s statues and some prime examples of Art Nouveau. Ready? Bien.

Remember that the museum rotates its large collection often, so find the latest arrangement on your current Orsay map and be ready to go with the flow.

• Walk down the steps to the main floor, a gallery filled with statues.

No, this isn’t ancient Greece. These statues are from the same era as the Theory of Relativity. It’s the conservative art of the French schools, and it was very popular throughout the 19th century. It was well liked for its beauty and refined emotion. The balanced poses, perfect anatomy, sweet faces, curving lines, and gleaming white stone—all of this is very appealing. (I’ll bad-mouth it later, but for now appreciate the exquisite craftsmanship of this “perfect” art.)

• Take a right into the small Room 1, marked Ingres, Delacroix, Chassériau. Look for a nude woman with a pitcher of water.

Let’s start where the Louvre left off. Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (ang-gruh), who helped cap the Louvre collection, championed a Neoclassical style. The Source is virtually a Greek statue on canvas. Like Venus de Milo, she’s a balance of opposite motions—her hips tilt one way, her breasts the other; one arm goes up, the other down; the water falling from the pitcher matches the fluid curve of her body. Her skin is porcelain-smooth, painted with seamless brushstrokes.

Ingres worked on this painting over the course of 35 years and considered it his “image of perfection.” Famous in its day, The Source influenced many artists whose classical statues and paintings are in this museum.

In the Orsay’s first few rooms, you’re surrounded by visions of idealized beauty—nude women in languid poses, Greek mythological figures, and anatomically perfect statues. This was the art adored by French academics and the middle-class (bourgeois) public. The 19th-century art world was dominated by two conservative institutions: the Academy (the state-funded art school) and the Salon, where works were exhibited to the buying public. The art they produced was technically perfect, refined, uplifting, and heroic. Some might even say...boring.

• Continue to Room 3 to find a pastel blue-green painting of a swooning Venus.

This painting and others nearby were popular items at the art market called the Salon. The public loved Alexandre Cabanel’s Venus. Emperor Napoleon III purchased it.

Cabanel lays Ingres’ The Source on her back. This goddess is a perfect fantasy, an orgasm of beauty. The Love Goddess stretches back seductively, recently birthed from the ephemeral foam of the waves. This is art of a pre-Freudian society, when sex was dirty and mysterious and had to be exalted into a purer, more divine form. The sex drive was channeled into an acute sense of beauty. French folk would literally swoon in ecstasy before these works of art. Like it? Go ahead, swoon. If it feels good, enjoy it. (If you feel guilty, get over it.) Now, take a mental cold shower, and get ready for a Realist’s view.

• Cross the main gallery of statues, backtrack toward the entrance, and enter Room 4 (directly across from Ingres), marked Daumier.

This is a liberal’s look at the stuffy bourgeois establishment that controlled the Academy and the Salon. In these 36 bustlets, Honoré Daumier, trained as a political cartoonist, exaggerates each subject’s most distinct characteristic to capture with vicious precision the pomposity and self-righteousness of these self-appointed arbiters of taste (most were members of the French parliament). Daumier gave insulting nicknames for the person being caricatured, like “gross, fat, and satisfied” or Monsieur “Platehead.” Give a few nicknames yourself. Can you find Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton, Al Sharpton, Newt Gingrich, Donald Trump, and Paul Ryan with sideburns? How about Margaret Thatcher?

These people hated the art you’re about to see. Their prudish faces tightened as their fantasy world was shattered by the Realists.

• Nearby, find Millet’s Gleaners. (Reminder: Paintings often move around, so you may need to use your Orsay map to find specific works.)

Jean-François Millet (mee-yay) shows us three gleaners, the poor women who pick up the meager leftovers after a field has already been harvested for the wealthy. Millet grew up on a humble farm. He didn’t attend the Academy and despised the uppity Paris art scene. Instead of idealized gods, goddesses, nymphs, and winged babies, he painted simple rural scenes. He was strongly affected by the socialist revolution of 1848, with its affirmation of the working class. Here he captures the innate dignity of these stocky, tanned women who bend their backs quietly in a large field for their small reward.

This is “Realism” in two senses. It’s painted “realistically,” not prettified. And it’s the “real” world—not the fantasy world of Greek myth, but the harsh life of the working poor.

• For a Realist’s take on the traditional Venus, walk farther up the gallery and find Manet’s Olympia in Room 14.

“This brunette is thoroughly ugly. Her face is stupid, her skin cadaverous. All this clash of colors is stupefying.” So wrote a critic when Edouard Manet’s nude hung in the Salon. The public hated it, attacking Manet (man-ay) in print and literally attacking the canvas.

Compare this uncompromising nude with Cabanel’s idealized, pastel, Vaseline-on-the-lens beauty in The Birth of Venus. Cabanel’s depiction was basically soft-core pornography, the kind you see today selling lingerie and perfume.

Manet’s nude doesn’t gloss over anything. The pose is classic, used by Titian, Goya, and countless others. But the traditional pose is challenged by the model’s jarring frankness. The sharp outlines and harsh, contrasting colors are new and shocking. The woman is Manet’s favorite model, a sometime painter and free spirit who also appears in his Déjeuner (described later). Her hand is a clamp, and her stare is shockingly defiant, with not a hint of the seductive, hey-sailor look of most nudes. This prostitute, ignoring the flowers sent by her last customer, looks out as if to say, “Next.” Manet replaced soft-core porn with hard-core art.

• Exit Room 14 up a few steps, hook left, and then right to see a huge canvas at the end of a large open space…

The Salon of 1855 rejected this dark-colored, sprawling, monumental painting that perplexed casual viewers. (It may be undergoing restoration in situ when you visit.) In an age when “Realist painter” was equated with “bomb-throwing Socialist,” it took courage to buck the system. Dismissed by the so-called experts, Gustave Courbet (coor-bay) held his own one-man exhibit. He built a shed in the middle of Paris, defiantly hung his art out, and basically mooned the shocked public.

Courbet’s painting takes us backstage, showing us the gritty reality behind the creation of pretty pictures. We see Courbet himself in his studio, working diligently on a Realistic landscape, oblivious to the confusion around him. Milling around are ordinary citizens, not Greek heroes. The woman who looks on is not a nude Venus but a naked artist’s model. And the little boy with an adoring look on his face? Perhaps it’s Courbet’s inner child, admiring the artist who sticks to his guns, whether it’s popular or not.

• Return to the main corridor, turn left, and head to the far end of the gallery, where you’ll walk on a glass floor over a model of Paris.

Expand to 100 times your size and hover over this scale-model section of the city. In the center sits the 19th-century Opéra Garnier, with its green-domed roof.

Nearby, you’ll also see a cross-section model of the Opéra. You’d enter from the right end, buy your ticket in the foyer, then move into the entrance hall with its grand staircase, where you could see and be seen by tout Paris. At curtain time, you’d find your seat in the red-and-gold auditorium, topped by a glorious painted ceiling. Notice that the stage, with elaborate riggings to raise and lower scenery, is as big as the seating area. Nearby are models of set designs from some famous productions. These days, Parisians enjoy their Verdi and Gounod at the modern opera house at Place de la Bastille.

The Opéra Garnier—opened in 1875—was the symbol of the belle époque, or “beautiful age.” Paris was a global center of prosperity, new technology, opera, ballet, painting, and joie de vivre. But behind Paris’ gilded and gas-lit exterior, a counterculture simmered. Revolutionaries battled to allow labor unions and give everyone the right to vote. Realist painters captured scenes of a grittier Paris, and Impressionists chafed against middle-class tastes, rejecting the careers mapped out for them to follow their artistic dreams.

Next up—the Orsay’s Impressionist collection. (Consider reading ahead on Impressionism while you’re still on the ground floor, as the Impressionist rooms can be very crowded.)

• Take the escalator up to the top floor (follow signs for 5th floor and Impressionisme). Pause to take in a commanding view of the vast interior of the Orsay. The grand clock at the far end is a reminder that when this building opened in 1900, train travel was king and schedules to the minute actually mattered. Follow the crowds, pass through the bookstore, glance at the backward clock, and enter the Impressionist rooms.

Light! Color! Vibrations! You don’t hang an Impressionist canvas—you tether it. Impressionism features bright colors, easygoing open-air scenes, spontaneity, broad brushstrokes, and the play of light.

The Impressionist collection is scattered chronologically through Rooms 29-36. You’ll see Monet hanging in many rooms, Manet sprinkled among Pissarro and Sisley, and a few Renoir here and a lot of Renoir there. Shadows dance and the displays mingle. Where they’re hung is a lot like their brushwork...delightfully sloppy. If you don’t see a described painting, just move on.

The Impressionists made their canvases shimmer by using a simple but revolutionary technique. Let’s say you mix red, yellow, and green together—you’ll get brown, right? But Impressionists didn’t bother to mix them. They’d slap a thick brushstroke of yellow down, then a stroke of green next to it, then red next to that. Up close, all you see are the three messy strokes, but as you back up...voilà! Brown! The colors blend in the eye, at a distance. But while your eye is saying “bland old brown,” your subconscious is shouting, “Red! Yellow! Green! Yes!”

There are no lines in nature, yet someone in the classical tradition (Ingres, for example) would draw an outline of his subject, then fill it in with color. Instead the Impressionists built a figure with dabs of paint...a snowman of color.

Although this top floor displays the Impressionists, you’ll find a wide variety of styles. What united these artists was their commitment to everyday subjects (cafés, street scenes, landscapes, workers), their disdain for the uptight Salon, their love of color, and a sense of artistic rebellion. These painters had a love-hate relationship with the “Impressionist” label. Later in their careers, they all went their own ways and developed their own individual styles.

The Impressionists all seemed to know each other. You may have seen a group portrait by Henri Fantin-Latour (on the main floor) depicting the circle of Parisian artists and intellectuals. Manet first met Degas while copying the same painting at the Louvre. Monet and Renoir set up their canvases in the country and painted side by side. Renoir painted with Cézanne and employed the mother of Utrillo as a model. Toulouse-Lautrec lived two blocks from Van Gogh. Van Gogh painted in Arles with Gauguin (an episode that ended disastrously). Van Gogh’s work was some of the first bought by an admiring Rodin.

They all learned from each other and taught each other, and they all influenced the next generation’s artists (Matisse and Picasso), who created Modern art.

This part of the tour is less a room-by-room itinerary than an introduction to the Orsay’s ever-changing collection. Have fun exploring: Think of it as a sun-dappled treasure hunt.

• Start with the Impressionists’ mentor, Manet, whose work is usually found in Room 29. The Orsay loves to mix up the Impressionist paintings. Review the art and photos on the next several pages so you will know which paintings to look for as you stroll.

Manet had an upper-class upbringing and some formal art training and had been accepted by the Salon. He could have cranked out pretty nudes and been a successful painter, but instead he surrounded himself with a group of young artists experimenting with new techniques. His reputation and strong personality made him their master, but he also learned equally from them.

Manet’s thumbnail bio is typical of almost all the Impressionists: They rejected a “normal” career (lawyer, banker, grocer) to become artists, got classical art training, exhibited in the Salon, became fascinated by Realist subjects, but grew tired of the Salon’s dogmatism. They joined the Impressionist exhibition of 1874, experimented with bright colors and open-air scenes, and moved on to forge their unique styles in later years.

Manet’s starting point was Realism. Rather than painting Madonnas, Greek gods, and academic warhorses, he hung out in cafés, sketchbook in hand, capturing the bustle of modern Paris. His painting style was a bit messy with its use of rough brushstrokes—a technique that drew the attention of budding painters like Monet and Renoir. Manet was never a full-on Impressionist. He tried but disliked open-air painting, preferring to sketch on the spot, then do his serious painting in the studio. And his colors remained dark, with plenty of brown and figures outlined in black. But when Manet’s paintings were criticized by the art establishment, the Impressionists rallied to his defense, and Manet became the best-known champion of the new movement.

Manet’s Luncheon on the Grass (Le Déjeuner sur l’Herbe, 1863) shocked Paris. The staid citizens looked at this and wondered: What are these scantily clad women doing with these men? Or rather, what will they be doing after the last baguette is eaten? It isn’t the nudity, but the presence of the men in ordinary clothes that suddenly makes the nudes look naked. The public judged the painting on moral rather than artistic terms. Here, too, the pose is classical (as seen in works by Titian), but it’s presented as though it were happening in a Parisian park in 1863.

A new revolutionary movement was starting to bud—Impressionism. Notice the background: the messy brushwork of trees and leaves, the play of light on the pond, and the light that filters through the trees onto the woman who stoops in the haze. Also note the strong contrast of colors (white skin, black clothes, green grass).

Let the Impressionist revolution begin!

• Scattered in the next galleries are works by two Impressionist masters at their peak, Monet and Renoir (with a bit of Degas in the mix, too). You’re looking at the quintessence of Impressionism. Monet and Renoir were good friends, often working side-by-side, and their canvases sometimes hang next to each other in these rooms.

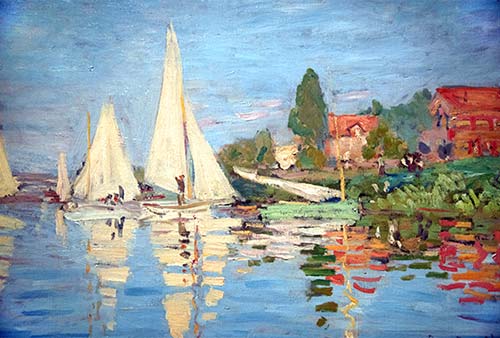

Monet (mo-nay) is the father of Impressionism. He fully explored the possibilities of open-air painting and tried to faithfully reproduce nature’s colors with bright blobs of paint. Throughout his long career, more than any of his colleagues, Monet stuck to the Impressionist credo of creating objective studies in color and light.

In the 1860s, Monet (along with Renoir) began painting landscapes in the open air. Although Monet did the occasional urban scene, he was most at home in the countryside, painting farms, rivers, trees, and passing clouds. He studied optics and pigments to know just the right colors he needed to reproduce the shimmering quality of reflected light. The key was to work quickly—at that “golden hour” (to use a modern photographer’s term) when the light was just right. Then he’d create a fleeting “impression” of the scene. In fact, that was the title of one of Monet’s canvases (now hanging in the Marmottan Museum); it gave the movement its name.

Monet is known for his series of paintings on the same subject. For example, you may see several canvases of the cathedral in Rouen. In 1893, Monet went to Rouen, rented a room across from the cathedral, set up his easel...and waited. He wanted to catch “a series of differing impressions” of the cathedral facade at various times of day and year. He often had several canvases going at once. In all, he did 30 paintings of the cathedral, and each is unique. The time-lapse series shows the sun passing slowly across the sky, creating different-colored light and shadows. The labels next to the art describe the conditions: in gray weather, in the morning, morning sun, full sunlight, and so on.

As Monet zeroed in on the play of colors and light, the physical subject—the cathedral—dissolved. It’s only a rack upon which to hang the light and color. Later artists would boldly throw away the rack, leaving purely abstract modern art in its place.

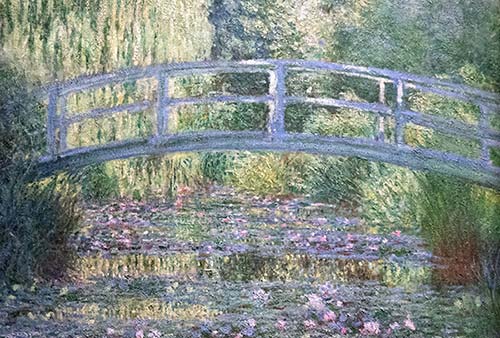

One of Monet’s favorite places to paint was the garden he landscaped at his home in Giverny, west of Paris (and worth a visit, provided you like Monet more than you hate crowds—see the Giverny & Auvers-sur-Oise chapter). The Japanese bridge and the water lilies floating in the pond were his two favorite subjects. As Monet aged and his eyesight failed, he made bigger canvases of smaller subjects. The final water lilies are monumental smudges of thick paint surrounded by paint-splotched clouds that are reflected on the surface of the pond.

Monet’s most famous water lilies are in full bloom at the Orangerie Museum, across the river in the Tuileries Garden. You can also see more Monet at the Marmottan Museum.

Renoir (ren-wah) started out as a painter of landscapes, along with Monet, but later veered from the Impressionist’s philosophy and painted images that were unabashedly “pretty.” He populated his canvases with rosy-cheeked, middle-class girls performing happy domestic activities, rendered in a warm, inviting style. As Renoir himself said, “There are enough ugly things in life.”

He did portraits of his friends (such as Monet) and his own kids, including his son Jean (who went on to make the landmark film Grand Illusion). But his specialty was always women and girls, emphasizing their warm femininity.

Renoir’s lighthearted work uses light colors—no brown or black. The paint is thin and translucent, and the outlines are soft, so the figures blend seamlessly with the background. He seems to be searching for an ideal, the sort of pure beauty we saw in paintings on the ground floor.

In his last years (when he was confined to a wheelchair with arthritis), Renoir turned to full-figured nudes—like those painted by Old Masters such as Rubens or Boucher. He introduced more and more red tones, as if trying for even greater warmth.

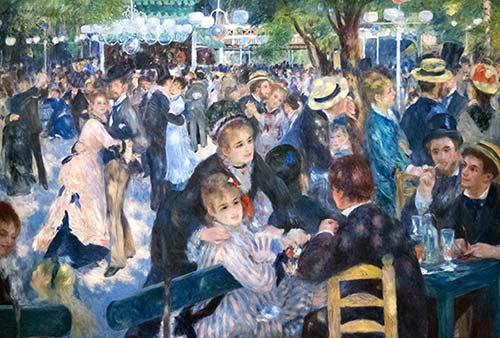

Renoir’s best-known work is Dance at the Moulin de la Galette (Bal du Moulin de la Galette, 1876). On Sunday afternoons, working-class folk would dress up and head for the fields on Butte Montmartre (near Sacré-Cœur basilica) to dance, drink, and eat little crêpes (galettes) till dark. Renoir liked to go there to paint the common Parisians living and loving in the afternoon sun. The sunlight filtering through the trees creates a kaleidoscope of colors, like the 19th-century equivalent of a mirror ball throwing darts of light onto the dancers. While the dance hall is long gone, you can still see the windmill and original entrance to the Moulin de la Galette (now a recommended restaurant) along our Montmartre Walk.

He captured the dappled light with quick blobs of yellow staining the ground, the men’s jackets, and the sun-dappled straw hat (right of center). Smell the powder on the ladies’ faces. The painting glows with bright colors. Even the shadows on the ground, which should be gray or black, are colored a warm blue. Like a photographer who uses a slow shutter speed to show motion, Renoir paints a waltzing blur.

Degas (day-gah) was a rich kid from a family of bankers, and he got the best classical-style art training. Adoring Ingres’ pure lines and cool colors, Degas painted in the Academic style. His work was exhibited in the Salon, he gained success and a good reputation, and then...he met the Impressionists.

Degas blends classical lines and Realist subjects with Impressionist color, spontaneity, and everyday scenes from urban Paris. He loved the unposed “snapshot” effect, catching his models off guard. Dance students, women at work, and café scenes are approached from odd angles that aren’t always ideal but make the scenes seem more real. He gives us the backstage view of life.

Although Degas participated in the Impressionist exhibitions, he disdained open-air painting, preferring to perfect his meticulous paintings in the studio. He painted few landscapes, focusing instead on people. And he created his figures not as a mosaic of colorful brushstrokes, but with a classic technique—outline filled in with color. His influence on Toulouse-Lautrec is clear.

Degas loved dance and the theater. The play of stage lights off his dancers, especially the halos of ballet skirts, is made to order for an Impressionist. A dance rehearsal let Degas capture a behind-the-scenes look at bored, tired, restless dancers (The Dance Class, La Classe de Danse, c. 1873-1875). Pirouetting near his oil paintings of dancers, you’ll see his small and life-size statues of them—he first modeled the figures in wax, then cast them in bronze.

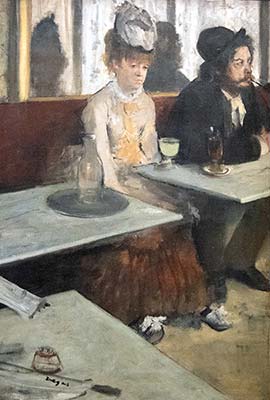

Degas hung out with low-life Impressionists, discussing art, love, and life in the cheap cafés and bars in Montmartre. In the painting In a Café (Dans un Café, 1875-1876), a weary lady of the evening meets morning with a last, lonely, nail-in-the-coffin drink in the glaring light of a four-in-the-morning café. The pale green drink at the center of the composition is the toxic substance absinthe, which fueled many artists and burned out many more.

The Orsay features some of the “lesser” pioneers of the Impressionist style. Browse around and discover your own favorites. Pissarro is one of mine. His grainy landscapes are subtler and more subdued than those of the flashy Monet and Renoir—but, as someone said, “He did for the earth what Monet did for the water.”

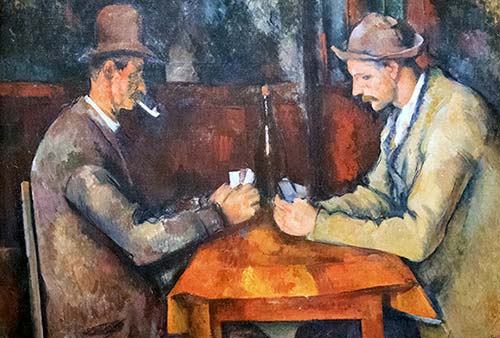

Paul Cézanne (say-zahn) brought Impressionism into the 20th century. After the color of Monet and the warmth of Renoir, Cézanne’s rather impersonal canvases can be difficult to appreciate. Bowls of fruit, landscapes, and a few portraits were Cézanne’s passion (see The Card Players, Les Joueurs de Cartes, 1890-1895). Because of his style (not the content), he is often called the first modern painter.

Cézanne was virtually unknown and unappreciated in his lifetime. He worked alone, lived alone, and died alone, ignored by all but a few revolutionary young artists who understood his genius.

Unlike the Impressionists, who painted what they saw, Cézanne reworked reality. He simplified it into basic geometric forms—circular apples, rectangular boulders, cone-shaped trees, triangular groups of people. He might depict a scene from multiple angles—showing a tabletop from above but the bowl of fruit resting on it from the side. He laid paint down with heavy brushstrokes, blending the background and foreground to obliterate traditional 3-D depth. He worked slowly, methodically, stroke by stroke—a single canvas could take months.

Where the Impressionists built a figure out of a mosaic of individual brushstrokes, Cézanne used blocks of paint to create a more solid, geometrical shape. These chunks are like little “cubes.” It’s no coincidence that his experiments in reducing forms to their geometric basics inspired the...Cubists.

Taking Cézanne’s “slabism” a step further, the last room in this gallery is dedicated to Pointillism and the vibrant dots of Seurat and Signac.

• Break time. Continue to the jazzy Café Campana, which serves small-plate fare with savoir faire. In good weather, venture out on the terrace for fresh air and great views. WCs are nearby (upstairs on level 6).

The Impressionists were like a tribe. They spoke the same artistic language. But, after that, more than ever, artists went in different directions, creating art that was uniquely their own. Van Gogh, Gauguin, and Toulouse-Lautrec are fine examples of these Post-Impressionists, and their paintings line the walls of the next string of rooms (Rooms 43-45 especially).

• You’ll find the Post-Impressionists in a series of rooms behind the café. Just follow the signs to Van Gogh.

Impressionists have been accused of being “light”-weights. The colorful style lends itself to bright country scenes, gardens, sunlight on the water, and happy crowds of simple people. It took a remarkable genius to add profound emotion to the Impressionist style.

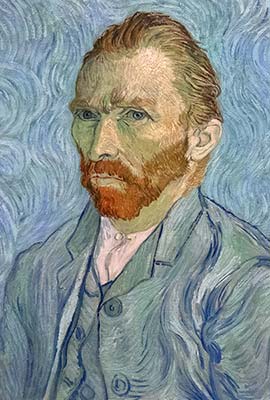

Like Michelangelo, Beethoven, and a select handful of others, Vincent van Gogh (pronounced “van-go,” or van-HOCK by the Dutch and the snooty) put so much of himself into his work that art and life became one. In the Orsay’s collection of paintings, you’ll see both Van Gogh’s painting style and his life unfold.

Vincent was the son of a Dutch minister. He, too, felt a religious calling, and he spread the gospel among the poorest of the poor—peasants and miners in overcast Holland and Belgium. He painted these hardworking, dignified folks in a crude, dark style reflecting the oppressiveness of their lives...and his own loneliness as he roamed northern Europe in search of a calling.

Encouraged by his art-dealer brother, Van Gogh moved to Paris, and voilà! The color! He met Monet, drank with Gauguin and Toulouse-Lautrec, and soaked up the Impressionist style. (For example, see how he might build a bristling brown beard using thick strokes of red, yellow, and green side by side.)

At first, he painted like the others, but soon he developed his own style. By using thick, swirling brushstrokes, he infused life into even inanimate objects. Van Gogh’s brushstrokes curve and thrash like a garden hose pumped with wine.

The social life of Paris became too much for the solitary Van Gogh, and he moved to the south of France. At first, in the glow of the bright spring sunshine, he had a period of incredible creativity and happiness. He was overwhelmed by the bright colors, landscape vistas, and common people. It was an Impressionist’s dream (see Midday, La Méridienne, 1889-90).

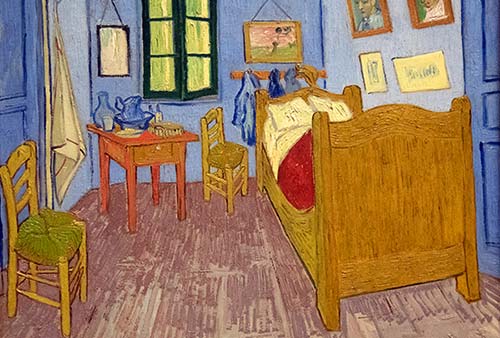

But being alone in a strange country began to wear on him. An ugly man, he found it hard to get a date. A painting of his rented bedroom in Arles shows a cramped, bare-bones place (Van Gogh’s Bedroom in Arles, La Chambre de Van Gogh à Arles, 1889). He invited his friend Gauguin to join him, but after two months together arguing passionately about art, nerves got raw. Van Gogh threatened Gauguin with a razor, which drove his friend back to Paris. In crazed despair, Van Gogh cut off a piece of his own ear.

The people of Arles realized they had a madman on their hands and convinced Vincent to seek help at a mental hospital. The paintings he finished in the peace of the hospital are more meditative—there are fewer bright landscapes and more closed-in scenes with deeper, almost surreal colors.

Van Gogh, the preacher’s son, saw painting as a calling, and he approached it with a spiritual intensity. In his last days, he wavered between happiness and madness. He despaired of ever being sane enough to continue painting.

His final self-portrait shows a man engulfed in a confused background of brushstrokes that swirl and rave (Self-Portrait, Portrait de l’Artiste, 1889). But amid this rippling sea of mystery floats a still, detached island of a face. Perhaps his troubled eyes knew that in only a few months, he’d take a pistol and put a bullet through his chest.

You can ponder his tragic life from outside his former Montmartre apartment (along the route of our Montmartre Walk) or on a day trip to the village where he took his life, Auvers-sur Oise (see the Giverny & Auvers-sur-Oise chapter).

• Carry on to the next room, where you’ll find works by…

Gauguin (go-gan) got the travel bug early in childhood and grew up wanting to be a sailor. Instead, he became a stockbroker. In his spare time, he painted, and he was introduced to the Impressionist circle. He learned their bright clashing colors but diverged from their path about the time Van Gogh waved a knife in his face. At the age of 35, he got fed up with it all, quit his job, abandoned his wife and family, and took refuge in his art. (Look for his self-portrait with the travel-dreams background.)

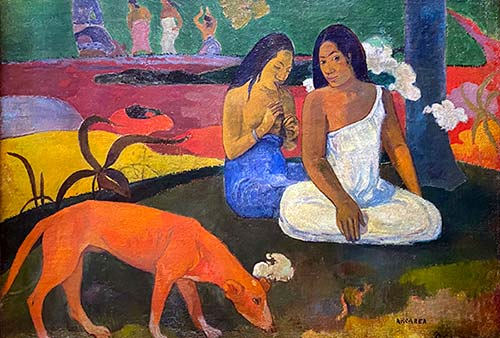

Gauguin traveled to the South Seas in search of the exotic, finally settling on Tahiti. There he found his Garden of Eden. He simplified his life into a routine of eating, sleeping, and painting. He simplified his paintings still more, to flat images with heavy black outlines filled with bright, pure colors. The background and foreground colors are equally bright, producing a flat, stained-glass-like surface.

Gauguin also carved statuettes in the style of Polynesian pagan idols. His fascination with indigenous peoples and Primitive art had a great influence on later generations. Matisse and the Fauves (or “Wild Beasts”) loved Gauguin’s bright, clashing colors. Picasso used his tribal-mask faces for his groundbreaking early Cubist works.

Gauguin’s best-known works capture an idyllic Tahitian landscape peopled by exotic women engaged in simple tasks and making music (Arearea, 1892). The local girls lounge placidly in unselfconscious innocence (so different from Cabanel’s seductive, melodramatic Venus). The style is intentionally “primitive,” collapsing the three-dimensional landscape into a two-dimensional pattern of bright colors. Gauguin intended that this simple style carry a deep undercurrent of symbolic meaning. He wanted to communicate to his “civilized” colleagues back home that he’d found the paradise he’d always envisioned.

• The next section features an artist who found his travel thrills closer to home, in the Paris underworld.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec was the black sheep of a noble family. At age 14 he broke both legs, which left him with a normal-size torso but dwarf-size limbs. Shunned by his family, a freak to society, he felt more at home in the world of other outcasts—prostitutes, drunks, thieves, dancers, and actors. He settled in Montmartre, where he painted the life he lived, sketching the lowlife in the bars, cafés, dance halls, and brothels he frequented. He drank absinthe and hung out with Van Gogh. He carried a hollow cane filled with booze. When the Moulin Rouge nightclub opened, Henri was hired to do its posters. Every night, the artist put on his bowler hat and visited the Moulin Rouge to draw the crowds, the cancan dancers, and the backstage action. Toulouse-Lautrec died at age 36 of syphilis and alcoholism.

Toulouse-Lautrec’s painting style captures Realist scenes with strong, curvaceous outlines. He worked quickly, creating sketches in paint that serve as snapshots of a golden era.

In Jane Avril Dancing (Jane Avril Dansant, 1891), he depicts the slim, graceful, elegant, and melancholy dancer, who stood out above the rabble. Her legs keep dancing while her mind is far away. Toulouse-Lautrec, the “artistocrat,” might have identified with her noble face—sad and weary of the nightlife, but immersed in it.

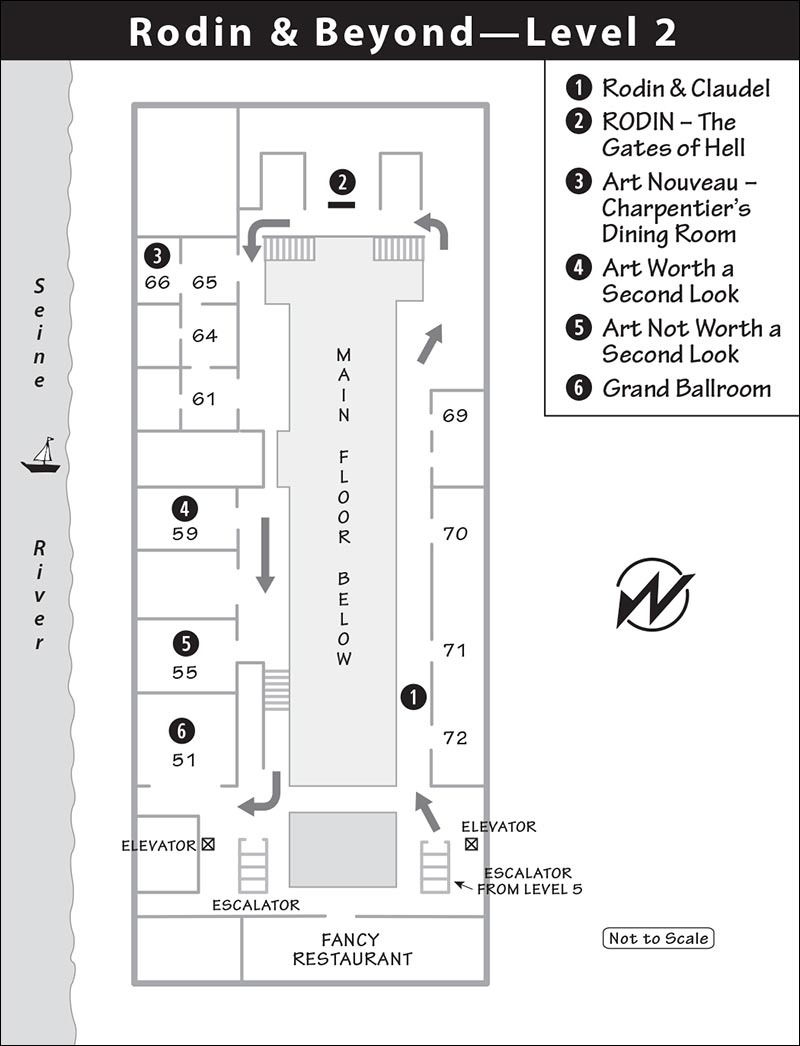

• Just past the last room in this section, ride the escalator down to level 2, an open-air mezzanine lined with statues. Make a circle around the mezzanine as you enjoy the work of Rodin, Claudel, and their contemporaries.

This section is frequently shuffled about. You should find most of these works close by, though some may be away for restoration.

Born of working-class roots and largely self-taught, Rodin combined classical solidity with Impressionist surfaces to become the greatest sculptor since Michelangelo. He labored in obscurity for decades, making knickknacks and doorknobs for a construction company. By age 40, he started to gain recognition.

• As you go along, look for a Rodin statue of a man missing just about everything but his legs.

Like his statue of The Walking Man (L’Homme Qui Marche, 1905), Rodin had one foot in the past and one stepping boldly into the future. This muscular, forcefully striding man could be a symbol of the Renaissance Man with his classical power. With no mouth or hands, he speaks with his body. Get close and look at the statue’s surface. It’s alive, rippling with frosting-like gouges. This rough, “unfinished” look reflects light like the rough Impressionist brushwork. And that makes the statue come to life, never quite at rest in the viewer’s eye. Rodin’s subject was always the human body, showing it in unusual poses that express inner emotion.

Another good example of Rodin’s style is St. John the Baptist (Saint Jean-Baptiste, 1878), which captures the mystical visionary who was the forerunner of Christ. Rodin’s inspiration was a shaggy peasant—looking for work as a model—whose bearing caught the artist’s eye. Coarse and hairy, with both feet planted firmly in mid-stride, this sculpture challenged the traditional poses expected from a 19th-century artist. A sense of movement and spontaneity mattered more to Rodin than mimicking classical stances.

Imagine Rodin’s work process. Rodin paid models to run, squat, leap, and spin around his studio however they wanted. When he saw an interesting pose, he’d yell, “Freeze!” (or “statue maker”) and get out his sketchpad. Rodin worked quickly, using his powerful thumbs to make a small statue in clay, which he would then reproduce as a life-size clay statue that in turn was used as a mold for casting a plaster or bronze copy. Authorized copies of Rodin’s work are now included in museums all over the world.

• You should pass a few more works by Rodin before landing (toward the far end of the mezzanine) on a deeply bronzed sculpture with three figures.

Camille Claudel was Rodin’s student, mistress, and muse. In Maturity (L’Age Mur, c. 1902)—a small bronze statue group of three figures—Claudel may have portrayed their doomed love affair. A young girl desperately reaches out to an older man, who is led away reluctantly by an older woman. The center of the composition is the empty space left when their hands separate. In real life, Rodin refused to leave his wife, and Claudel ended up in an insane asylum.

• At the far end of the hall (hooking left, around the corner), you will run into a large gate cluttered with sculptural brilliance...

Rodin worked for decades on this model for a ceremonial “door” depicting the lost souls of Dante’s hell. It contains some of his greatest hits—small statues that he later executed in full size. Find The Thinker squatting above the doorway, contemplating Man’s fate. The Thinker was meant to be Dante surveying the characters of Hell. But Rodin so identified with this pensive figure that he chose it to stand atop his own grave. This Thinker is only two feet high, but it was the model for the full-size work that has become one of the most famous statues in the world (you can see a full-size Thinker in the Rodin Museum garden).

The door’s 186 figures eventually inspired larger versions of The Kiss, the Three Shades, and more. (You can read more about the artist and The Gates of Hell in the Rodin Museum Tour.)

From this perch in the Orsay, look down to the main floor at all the classical statues between you and the big clock, and realize how far we’ve come—not in years, but in stylistic changes. Many of the statues below—beautiful, smooth, balanced, and idealized—were created at the same time as Rodin’s powerful, haunting works. Rodin’s sculptures capture the groundbreaking spirit of much of the art in the Orsay Museum. With a stable base of 19th-century stone, he helped launch art into the 20th century.

• While you’ve now seen the essential Orsay, you’ll need to return to the other end of the gallery to leave. For a little artistic dessert, stay on this level and slalom down the other side of the mezzanine, popping into some entertaining last rooms.

The beauty of the Orsay is that it combines all the art from 1848 to 1914, both modern and classical, in one building. The classical art, so popular in its day, was maligned and largely forgotten in the later 20th century. It’s time for a reassessment. Is it as gaudy and gawd-awful as we’ve been led to believe? From our 21st-century perspective, let’s take a look at the opulent fin de siècle French high society and its luxurious art.

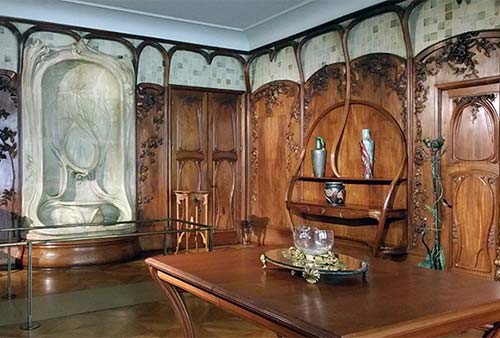

• At the start of the corridor, enter room 65. From here, Rooms 61-66 feature curvaceous Art Nouveau furniture.

The Industrial Age brought factories, row houses, machines, train stations, geometrical precision—and ugliness. At the turn of the 20th century, some artists reacted against the unrelieved geometry of harsh, pragmatic, iron-and-steel Eiffel Tower art with a “new art”—Art Nouveau. (Hmm. I think I had a driver’s ed teacher by that name.)

Stand amid a reconstructed wood-paneled dining room (Room 66) designed by Alexandre Charpentier (Boiserie de la Salle à Mangér). With its carved vines, leafy garlands, and tree-branch arches, it’s one of the finest examples of Art Nouveau.

Like nature, which also abhors a straight line, Art Nouveau artists used the curves of flowers and vines as their pattern. They were convinced that “practical” didn’t have to mean “ugly.” They turned everyday household objects into art. Another well-known example of Art Nouveau is the sinuous wrought-ironwork of some of Paris’ early Métro entrances—which were commissioned by banker Adrien Bénard, the same man who ordered this dining room for his home.

• Return to the open-air mezzanine and turn right. Enter Room 59.

We’ve seen some great art. Now let’s see some not-so-great art—at least, that’s what modern critics tell us. This is realistic art with a subconscious kick. The centerpiece of Room 59 is Henri Martin’s Serenity (Sérénité, 1899), a dream in the woods. Three nymphs with harps waft off through the trees to the right. These people are stoned on something. High above on the right, Jean Delville’s The School of Plato (L’Ecole de Platon, 1898) could be subtitled “The Athens YMCA.” A Christ-like Plato surrounded by adoring, half-naked nubile youths gives new meaning to the term “platonic relationship.” Will the pendulum shift so that one day art like The School of Plato becomes the new, radical avant-garde style?

• Continue down the mezzanine until you reach Room 55.

A director of the Orsay once said, “Certainly, we have bad paintings. But we have only the greatest bad paintings.” And here they are. On the left, Fernand Cormon’s Cain (1880) depicts the world’s first murderer, whose murder weapon is still in his belt as he’s exiled with his family. Archaeologists had recently discovered a Neanderthal skull, so the artist makes Cain’s family part of a prehistoric hunter-gatherer tribe. Opposite the entry, in Edouard Detaille’s The Dream (Le Rêve, 1888), soldiers lie still, asleep without beds, while visions of Gatling guns dance in their heads. Behind that, in the next room, Léon Lhermitte, often called “the grandson of Courbet and Millet,” depicts peasants getting their wages in his Paying the Harvesters (La Paye des Moissonneurs, 1882). The subtitle of the work could be, “Is this all there is to life?” (Or, “The Paycheck...After Deductions.”)

• Climb a few steps and continue along the mezzanine. Near the escalators, turn right and find the palatial Room 51, with mirrors and chandeliers, marked Salle des Fêtes (Grand Ballroom).

This room was part of the hotel that once adjoined the Orsay train station. One of France’s poshest nightspots, it was built in 1900, abandoned after 1939, condemned, and then restored to the elegance you see today. You can easily imagine gowned debutantes and white-gloved dandies waltzing the night away to the music of a chamber orchestra. Take in the interior decoration: raspberry marble-ripple ice-cream columns, pastel ceiling painting, gold work, mirrors, and leafy garlands of chandeliers. People it with the glitterati of Paris circa 1910.

Is this stuff beautiful or merely gaudy? Divine or decadent? Whatever you decide, it was all part of the marvelous world of the Orsay’s century of art.

• The exit is directly below. A good place to ponder it all is Le Restaurant, located near the escalators on level 2. It’s pricey, but there’s an affordable coffee-and-tea happy hour. After all this art, you deserve it. Or, for a good, fresh-air museum antidote, stroll the pedestrian-only riverside promenade (Les Berges de Seine), which starts below the Orsay and runs west to Pont de l’Alma, near the Eiffel Tower. There you can enjoy an Impressionist Parisian scene come to life.