Musée de l’Orangerie

This Impressionist museum is as lovely as a water lily. Step out of the tree-lined, sun-dappled Impressionist painting that is the Tuileries Garden and into the Orangerie (oh-rahn-zhuh-ree), a little bijou of select works by Monet, Renoir, Matisse, Picasso, and others.

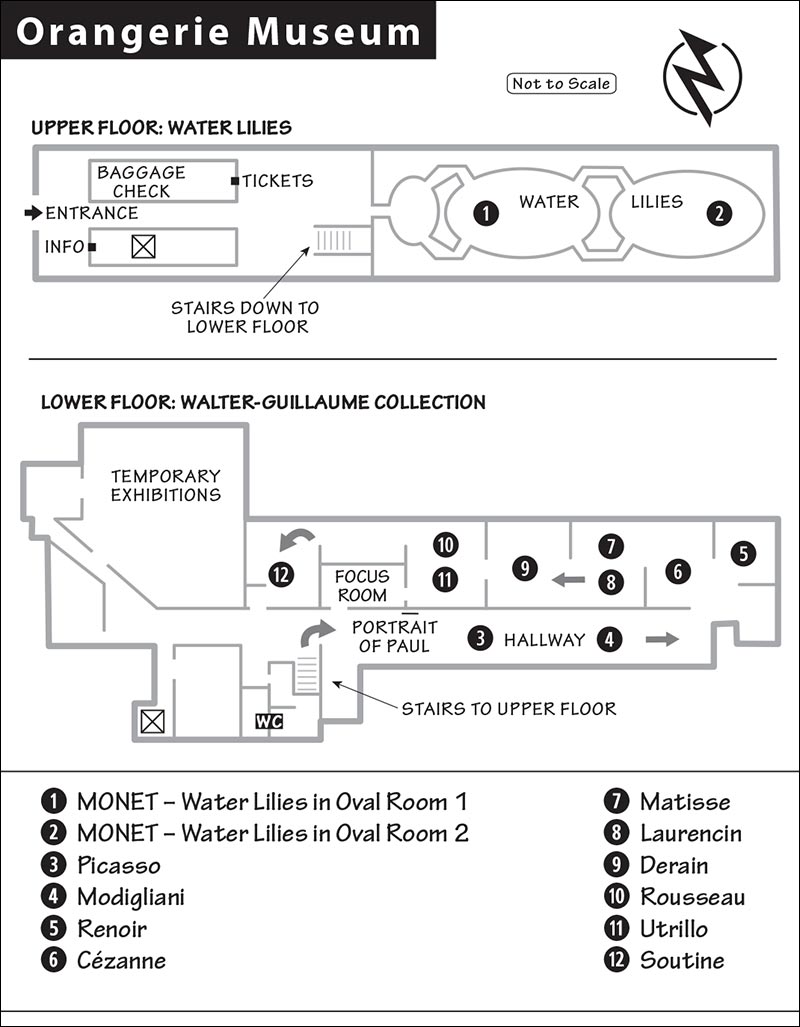

On the main floor you’ll find the main attraction, Monet’s Water Lilies (Nymphéas), floating dreamily in oval rooms. The rooms were designed in the 1920s to display this art, following the artist’s exacting specifications. But in the 1960s the museum added a floor above the Water Lilies, cutting them off from the daylight that was, after all, their inspiration and subject matter. In 2006 the upstairs collection was moved underground, and the upper floor was transformed into a tall skylight—drenching the Water Lilies in natural light.

In the underground gallery are select works of other Impressionist heavyweights well worth your time. The museum is small enough to enjoy in a short visit, but complete enough to show the bridge from Impressionism to Modernism. And it’s all beautiful.

Cost: €12.50, timed-entry ticket highly recommended (purchase online in advance), free for those under 18, free on the first Sun of the month (but timed-entry ticket required), €20 combo-ticket with Orsay Museum (not sold online but you can book a free timed-entry ticket on the Orangerie website, then purchase combo-ticket at the museum), covered by Museum Pass.

Hours: Wed-Mon 9:00-18:00, closed Tue.

Information: +33 1 44 77 80 07, www.musee-orangerie.fr.

Reserved Entry: The Orangerie highly recommends all visitors—including Museum Pass holders—reserve a time slot for your visit. In quiet times, you may be able to get a reservation in person for the same day, but to avoid long lines I’d err on the side of booking ahead.

When to Go: The museum is small and popular. It’s most crowded on weekends, on Mondays, and in the afternoons (14:00-18:00).

Getting There: It’s in the Tuileries Garden near Place de la Concorde (Mo: Concorde) and a lovely 15-minute stroll from the Orsay Museum through the Tuileries.

Getting In: A security checkpoint causes lines, but there may be a shorter security line for Museum Pass holders.

Tours: €6 guided tours in English are offered a few times a week—book online. The €5 audioguide adds nothing beyond what’s in this book on the Water Lilies, but it provides good detail about individual canvases in the Walter-Guillaume Collection.

Length of This Tour: Allow one hour. Temporary exhibitions often merit extra time. With less time, you could see (if not “experience”) the two rooms of Water Lilies in a glance.

Starring: Claude Monet’s Water Lilies and select works by the pioneers of modern painting.

Cuisine Art: Between the two floors, a cheery café with reasonable prices offers a welcome pause.

• Monet’s Water Lilies float serenely in two pond-shaped rooms, straight ahead past the ticket takers. Examine them up close to see Monet’s technique; stand back to take in the whole picture.

Like Beethoven going deaf, a nearly blind Claude Monet (1840-1926) wrote his final symphonies on a monumental scale. Even as he struggled with cataracts, he planned a series of huge six-foot-tall canvases of water lilies to hang in special rooms at the Orangerie.

These eight mammoth, curved panels immerse you in Monet’s garden. We’re looking at the pond in his garden at Giverny—dotted with water lilies, surrounded by foliage, and dappled by the reflections of the sky, clouds, and trees on the surface. The water lilies (nymphéas in French) range from plain green lily pads to flowers of red, white, yellow, lavender, and various combos.

The effect is intentionally disorienting; the different canvases feature different parts of the pond from different angles, at different times of day, with no obvious chronological order. Monet mingles the pond’s many elements and lets us sort it out.

• Start with the long wall on your right (as you enter) and work counterclockwise.

It’s Morning on the pond at Giverny. The blue pond is the center of the composition, framed by the green, foliage-covered banks at either end. Lilies float in the foreground, and the pond stretches into the distance.

The sheer scale of the Orangerie project was daunting for an artist in his twilight years. This vast painting is made from four separate canvases stitched together and spans 6 feet 6 inches by 55 feet. Altogether, Monet painted 1,950 square feet of canvas to complete the Water Lilies series. Working at his home in Giverny, Monet built a special studio with skylights and wheeled easels to accommodate the canvases.

The panel at the far end, called Green Reflections, looks deep into the dark water. Green willow branches are reflected on the water in a vertical pattern; lily pads stretch horizontally.

Along the other long wall (Clouds), green lilies float among lavender clouds reflected in blue water. Staring into Monet’s pond, we see the intermingling of the four classical elements—earth (foliage), air (the sky), fire (sunlight), and water—the primordial soup of life.

The true subject of these works is the play of reflected light off the surface of the pond. Monet would work on several canvases at once, each dedicated to a different time of day. He’d move with the sun from one canvas to the next. Pan slowly around this hall. Watch the pond turn from predawn darkness (far end) to clear morning light (Morning) to lavender late afternoon (Clouds) to glorious sunset—in the west, where the sun actually does set.

In Sunset (near end), the surface of the pond is stained a bright yellow. Get close and see how Monet worked. Starting from the gray of the blank canvas (lower right), he’d lay down big, thick brushstrokes of a single color, weaving them in a (mostly) horizontal and vertical pattern to create a dense mesh of foliage. Over this, he’d add more color for the dramatic highlights, until (in the center of the yellow) he got a dense paste of piled-up paint. Up close, it’s a mess—but back up, and the colors begin to resolve into a luminous scene. There are no clearly identifiable objects in this canvas—no lilies, no trees, no clouds, no actual sun—just pure reflected color.

• Continue into the second oval room, starting with the long wall on your right and working counterclockwise.

In this room, Monet frames the pond with pillar-like tree trunks and overhanging foliage. The compositions are a bit more symmetrical and the color schemes more muted, with blue and lavender and green-brown. Monet’s paintings almost always deal with the foundation of life and unspoiled nature. This room begs you to stroll its banks, slowly ambling with the artist in a complete loop—perhaps while listening to Debussy.

In Willows on a Clear Morning (on the long wall to the right), we seem to be standing on the bank of the pond, looking out through overhanging trees at the water. The swirling branches and horizontal ripples on the pond suggest a gentle breeze.

The Two Willows (far end) frame a wide expanse of water dotted with lilies and the reflection of gray-pink clouds.

Stand close in front of Morning Willows (long left wall). Notice how a “brown” tree is a tangled Impressionist beard of purple, green, blue, and red. Each leaf is a long brushstroke, each lily pad a dozen smudges.

At the near end, Reflections of Trees is a dark mess of blue-purple paint brightened only by the lone rose lilies in the center. Each lily is made of many Impressionist brushstrokes—each brushstroke is itself a mix of red, white, and pink paints. Put a mental frame around a single lily, and it looks like an abstract canvas. Monet demonstrates both his mastery of color and his ability to render it with paint, applied generously and deftly. He wanted the vibrant colors to keep firing your synapses.

With this last canvas, darkness descends on the pond. The room’s large, moody canvases, painted by an 80-year-old man in the twilight of his life, invite meditation.

For 12 years (1914-1926), Monet worked on these paintings obsessively. A successful eye operation in 1923 gave him new energy. Monet completed all the planned canvases, but he didn’t live to see them installed here. In 1927, the year after his death, these rooms were completed and the canvases put in place. Some call this the first “art installation”—art displayed in a space specially designed for it in order to enhance the viewer’s experience.

Monet’s final work was more “modern” than Impressionist. Each canvas is fully saturated with color, the distant objects as bright as the close ones. Monet’s mosaic of brushstrokes forms a colorful design that’s beautiful even if you just look “at” the canvas, like wallpaper. He wanted his paintings to be realistic and three-dimensional, but with a pleasant, two-dimensional pattern. As the subjects become fuzzier, the colors and patterns predominate. Monet builds a bridge between Impressionism and modern, abstract art.

To see more of Monet’s work, visit the Marmottan Museum, and to experience the place that inspired these water lilies, take a day trip to Giverny (see the Giverny & Auvers-sur-Oise chapter).

• Descend the stairs to the lower floor. At the bottom of the stairs is a small room with temporary exhibits highlighting a single artist. As you enter this room (labeled “Focus” on the map), check the two miniature rooms on the left. The art you’ll see here was in the apartment of the pioneering art collector Paul Guillaume, who funded and inspired many artists. This is a good place to read the sidebar about him and prepare to tour the...

These paintings—Impressionist, Fauvist, and Cubist—were amassed by the art dealer Paul Guillaume and inherited by his wife, Domenica Guillaume Walter. (You may see portraits of them as you tour their collection.) This power couple’s collection is a snapshot of what was hot in the world of art, circa 1920. The once-revolutionary Impressionists had become completely old-school, although their paintings—now classics—commanded a fortune. The bohemian Fauvists and Cubists, who invented modern art atop Butte Montmartre (c. 1900-1915), had suddenly become the darlings of the art world. But they refused to be categorized, and their work in the 1920s branched out in dozens of new directions. Browse the rooms and watch the various “isms” unfold. (Note that though the displays change often, the place is small and you can easily find the artists covered in this tour, usually in the order I’ve listed them.)

• Start with the long hallway.

This hallway features a smattering of paintings by some of the era’s greatest pioneers. You’ll get a taste of Picasso’s many styles, Modigliani’s primitive heads, Derain’s quirky still lifes, Matisse’s “flatness,” and Rousseau’s charming childlike world. • You may see more of these artists later, but for now focus on the hallway’s fine selection of work by two contrasting artists.

Picasso is a shopping mall of 20th-century artistic styles. The Orangerie’s collection alone traces his life through several periods: Rose (red-toned nudes with timeless, masklike faces), Blue (sad and tragic), Cubist (flat planes of interwoven perspectives), and Classical (massive, sculptural nudes—warm blow-up dolls with substance). If all roads lead to Paris, all art styles flowed through Picasso.

In his short, poverty-stricken, drug-addled life, Modigliani produced timeless-looking portraits of modern people. Born in Italy, Modigliani moved to Paris, where he hung around the fringes of the avant-garde crowd in the Montmartre. He gained a reputation for his alcoholic excesses and outrageous behavior.

Turning his back on the prevailing Fauvist/Cubist ambience of the times, Modigliani developed a unique style, influenced by primitive tribal masks. Modigliani died young, just as his work was gaining recognition.

• At the end of the hall, turn left to Renoir’s room. As you enter each remaining room, you’ll find a brief description of the artists whose works are shown there.

These pleasant works by Renoir provide a smooth transition from 19th-century Impressionism to 20th-century Modernism.

Renoir loved to paint les femmes—women and girls—nude and innocent, taking a bath or practicing the piano, all with rosy-red cheeks and a relaxed grace. We get a feel for the happy family life of middle-class Parisians (including Renoir’s own family) during the belle époque—the beautiful age of the late 19th century. Renoir’s warm, sunny colors (mostly red) are Impressionist, but he adds a classical touch with his clearer lines and, in the later nudes, the voluptuousness of classical statues and paintings. He seems to enjoy capturing the bourgeoisie, soft and elegant, enjoying their leisure pursuits.

• The next artists may be featured in a different order, but in this small museum, they’re not hard to find.

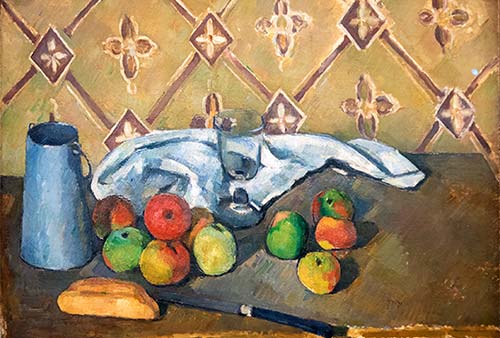

These small canvases of simple subjects pushed modern artists to reinvent the rules of painting. The fruit of Cézanne’s still lifes has an underlying geometry “built” from patches of color. In the shapes of nature, Cézanne saw spheres, cylinders, and cones. He was fond of saying, “First you must learn to paint these simple shapes. Then you will be able to do whatever you want.”

There’s no traditional shading to create the illusion of three dimensions, but this fruit bulges out like a cameo from the canvas. The fruit is clearly at eye level, yet it’s also clearly placed on a table seen from above. Cézanne broke the rules, showing multiple perspectives at once. Picasso was fascinated with Cézanne’s strange new world—which seems to give us a peek into the secret lives of fruits.

In his landscapes, Cézanne the Impressionist creates “brown” rocks out of red, orange, and purple, and “green” trees out of green, lime, and purple. Cézanne the proto-Cubist builds the rocks and trees with blocks of thick brushstrokes.

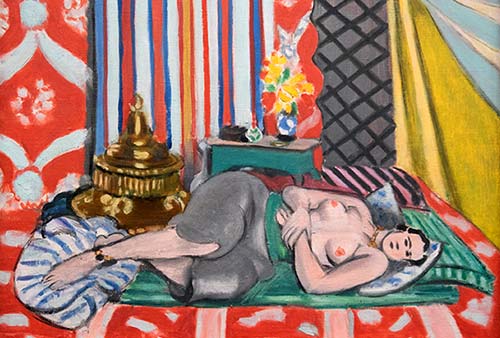

After World War I, Matisse moved to the south of France. He abandoned his fierce Fauvist style and painted languid women in angular rooms with arabesque wallpaper. These paler tones evoke the sunny luxury of the Riviera. Traditional perspective is thrown out the occasional hotel window as the women and furnishings in the “foreground” blend with the wallpaper “background” to become part of the decor.

As the girlfriend of the poet and art critic Guillaume Apollinaire, Laurencin was right at the heart of the Montmartre circle when modern art was born. Her work—featuring women and cuddly animals intertwined in pink, blue, and gray tones—spreads a pastel sheen over this tumultuous time.

Along with his friend Matisse, Derain helped invent Fauvism. Then, in Montmartre, along with his friend Picasso, he helped forge Cubism. In the 1920s, this former wild beast (fauve) tamed his colors. He and Picasso rode the rising wave of Classicism that surfaced after the chaos of the war years. With sharp outlines and studied realism, Derain’s still lifes portray nudes, harlequins, portraits, and landscapes—all in odd, angular poses.

Rousseau, a simple government worker, never traveled outside France. But in his artwork he created an exotic, dreamlike, completely unique world. A good example is his painting of a Parisian wedding set amid tropical trees (you might find this painting in the main hall). Figures are placed in a 3-D world, but the lines of perspective recede so steeply into the distance that everyone is in danger of sliding down the canvas. Without any feet, the subjects seem barely tethered to the earth. The way Rousseau put familiar images in bizarre settings influenced the Surrealists. The Orangerie has France’s biggest collection of Rousseaus.

The hard-drinking, streetwise, bohemian artist is known for his postcard views of Montmartre—whitewashed buildings under perennially cloudy skies. For more on Utrillo, see here.

• The next small room is often dedicated to art from beyond the Western world that Paul Guillaume brought to Paris. This “primitive” style—of stylized features, elongated heads and necks, and almond eyes—inspired painters of the period, including Picasso, Derain, and Modigliani.

When his friend Modigliani died (and Modigliani’s widow committed suicide), Soutine went into a tailspin of depression that drove him to paint. The subjects are ordinary—landscapes, portraits, and a fine selection of your favorite cuts of meat—but the style is deformed and Expressionistic. It shows a warped world in a funhouse mirror, smeared onto the canvas with thick, lurid colors. The never-cheerful Soutine was known to destroy work that did not satisfy him. Stand and ponder why these made the cut.

Did I say that the Orangerie’s collection was as beautiful as an Impressionist painting? Well, Soutine’s misery is so complete, it’s almost a thing of beauty.

• You’ll find a few more rooms for temporary exhibits at the end, usually worth checking out.