Musée de l’Armée

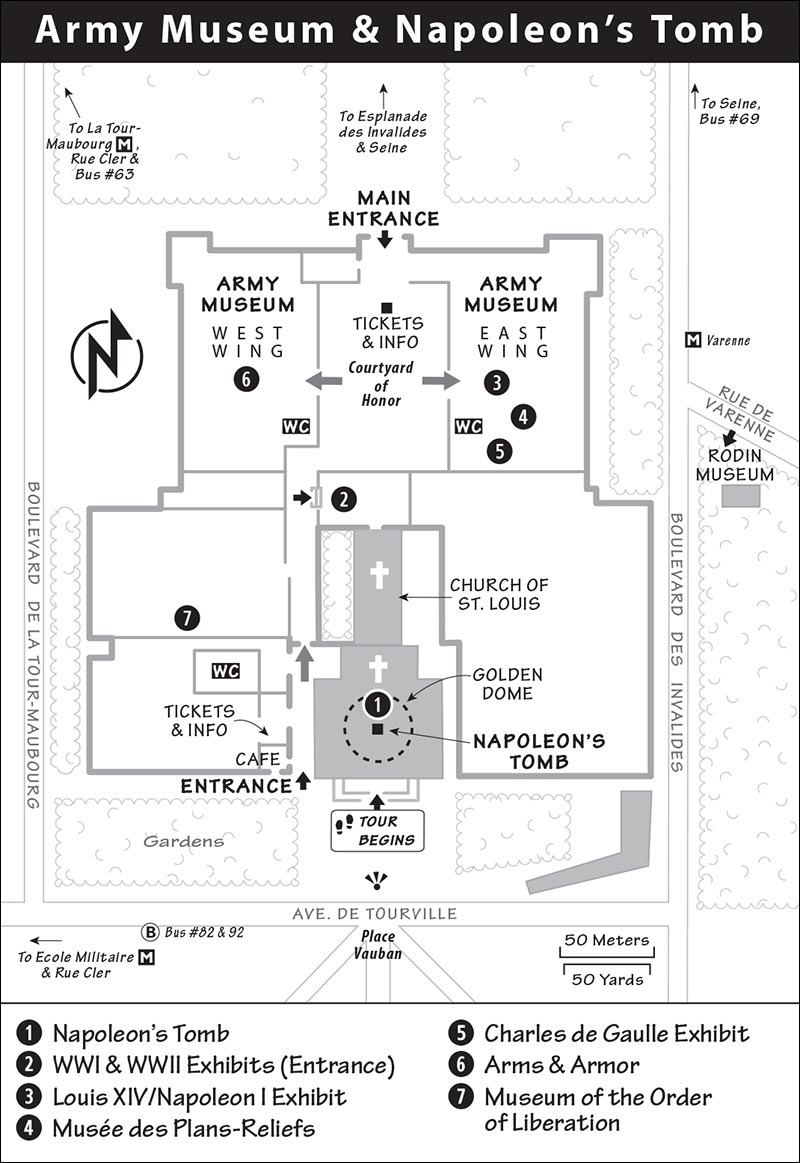

Map: Army Museum & Napoleon’s Tomb

FROM LOUIS XIV TO NAPOLEON I, 1643-1814

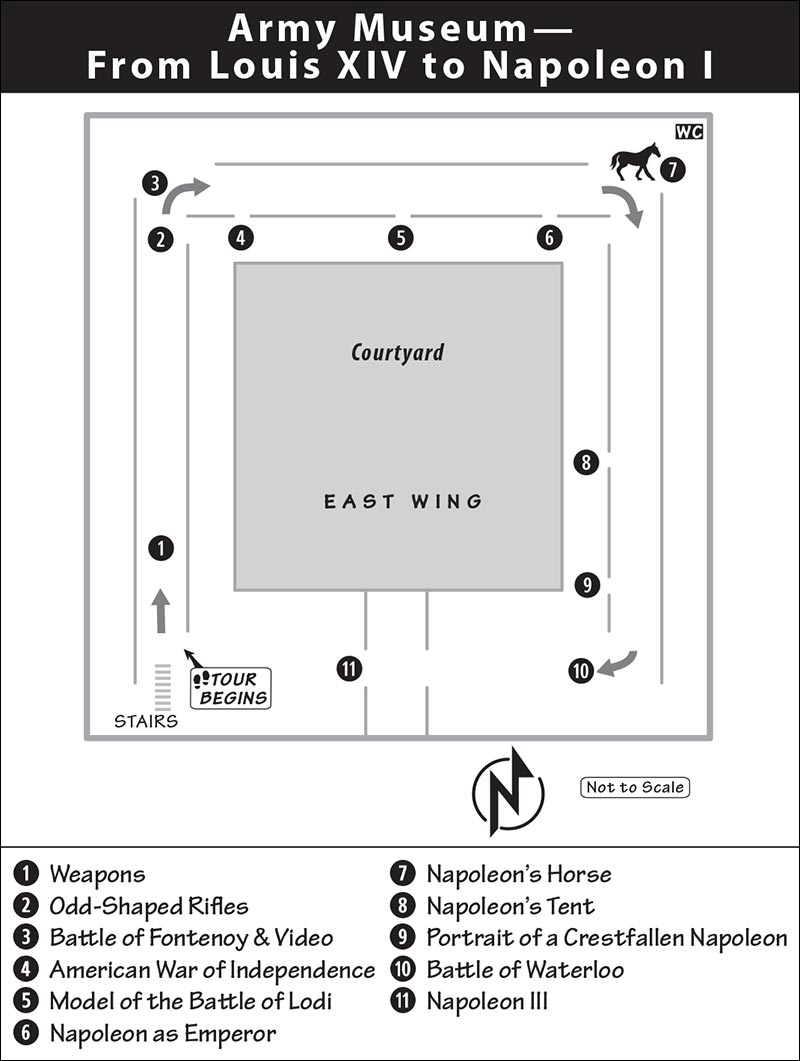

Map: Army Museum—From Louis XIV to Napoleon I

The complex of Les Invalides—a former veterans’ hospital built by Louis XIV—has various military collections, together called the Army Museum. You’ll see medieval armor, Napoleon’s horse stuffed and mounted, Louis XIV-era uniforms and weapons, and much more. The best part is the section dedicated to the two world wars, especially World War II. Visiting the different sections, you can watch the art of war unfold, from stone axes to Axis powers. What’s more, Napoleon himself is entombed beneath the church’s golden dome.

Cost: €15, covered by Museum Pass (show it at the entrance to each sight or exhibit), admission includes Napoleon’s Tomb and all museum collections within the Invalides complex. Special exhibits and evening concerts are extra. Children enter for free, but you must line up to get them a ticket. The sight is also free for military personnel in uniform.

Hours: Daily 10:00-18:00; Napoleon’s Tomb stays open until 22:00 on the first Friday of the month (when the entry drops to €10 after 18:00).

Information: +33 1 44 42 38 77, www.musee-armee.fr.

Getting There: The museum and tomb are at Hôtel des Invalides, with its hard-to-miss golden dome (129 Rue de Grenelle). Ride the Métro (Mo: La Tour-Maubourg, Varenne, or Invalides), or take a bus: #69 from the Marais and Rue Cler area or #63 from the St. Germain-des-Prés area (buses #82 and #92 also serve the sight). The museum is a 10-minute walk from Rue Cler. There are two entrances: one from the Grand Esplanade des Invalides, and the other from behind the gold dome on Avenue de Tourville.

Visitor Information: A helpful, free map/guide is available at the two ticket offices. Excellent English information is posted in most exhibits. Paired with the self-guided tour in this chapter, that should be sufficient info for most.

Tours: If you want even more background, a fine €5 multimedia guide covers the whole complex.

Length of This Tour: Allow two to four hours depending on your appetite for all things Napoleon and war.

Concerts: The museum hosts classical music concerts throughout the year. For schedules, see the museum website.

Sound-and-Light Show: From mid-July to early September, Les Invalides puts on a dazzling sound-and-light show called La Nuit aux Invalides; each year has a new theme. The 50-minute show starts when it gets dark (22:30 in July, 22:00 in Aug-Sept). Stunning light displays accompanied by stirring music and a compelling story keep viewers enthralled (€25 seated, €18 standing, English headsets available for a fee, buy tickets at https://lanuitauxinvalides.fr).

Eating: The cafeteria is reasonable (outdoor tables available), and the museum gardens are picnic-perfect. Rue Cler eateries are a 10-minute walk away, as is the riverside promenade along the Seine, with many eating options.

Nearby: You’ll likely see the French playing boules on the esplanade (as you face Les Invalides from the riverside, look for the dirt area to the upper right; for the rules of boules, see here).

Starring: Napoleon’s Tomb, exhibits on World Wars I & II, memorabilia of Napoleon (including his stuffed horse).

The Army Museum and Napoleon’s Tomb are in the Invalides complex (or should I say “Napoleon complex”?). Various exhibits are scattered around the large complex. Consult your free Army Museum map for the whole list and their locations. Your ticket covers them all—just flash your ticket or Museum Pass at each entrance.

Pick your favorite war. With limited time, visit only ▲▲▲ Napoleon’s Tomb and the excellent ▲▲▲ World War I and World War II exhibits. Next on my list would be the exhibit ▲▲ From Louis XIV to Napoleon I (1643-1814), featuring swords and muskets, key battles of the Revolution, and memorabilia of Napoleon. If you still have energy, browse the ▲ Charles de Gaulle Exhibit, which honors France’s WWII hero, or Arms and Armor, an impressive collection of medieval suits of armor, pikes, swords, and cannons. Though there are other exhibits to see here, this chapter covers only the top sights in order of importance.

• You can enter the Invalides complex from either the north or the south side (ticket offices are at both entrances). Start at Napoleon’s Tomb—underneath the golden dome, with its entrance on the south side (farthest from the Seine).

Enter the church, gaze up at the dome, then lean over the railing and bow to the emperor lying inside the scrolled, red porphyry tomb (see photo). If the lid were opened, you’d find an oak coffin inside, holding an ebony coffin, housing two lead ones, then mahogany, then tinplate...until finally, you’d find Napoleon himself, staring up, with his head closest to the door. When his body was exhumed from the original grave and transported here (1840), it was still perfectly preserved, even after 19 years in the ground.

Born of humble Italian heritage on the French-owned isle of Corsica, Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821) went to school at Paris’ Ecole Militaire, quickly rising through the ranks amid the chaos of the Revolution. The charismatic “Little Corporal” won fans by fighting for democracy at home and abroad. In 1799, he assumed power, and within five short years he conquered most of Europe. The great champion of the Revolution had become a dictator, declaring himself emperor of a new Rome.

Napoleon’s red tomb on its green base stands 15 feet high in the center of a marble floor, circled by a mosaic crown of laurels and exalted by a glorious dome above.

Now, panning around the chapel, you’ll find tombs of Napoleon’s family. Despots are quick to make loyal family members part of their inner circle. After conquering Europe, he installed his big brother, Joseph, as king of Spain (turn around to see Joseph’s black-and-white marble tomb in the alcove to the left of the door); his little brother, Jerome, became king of the German kingdom of Westphalia (tucked into the chapel to the right of the door); and his baby boy, Napoleon II (downstairs), sat in diapers on the throne of Rome.

In other alcoves, you’ll find more dead war heroes, including Marshal Ferdinand Foch, the commander in chief of the multinational Allied forces in World War I. To the right of Foch lies Maréchal Vauban, Louis XIV’s great military engineer, who designed the fortifications of more than 100 French cities. Vauban’s sarcophagus shows him reflecting on his work with his engineer’s tools, flanked by figures of war and science. These heroes, plus many painted saints, make this a kind of French Valhalla.

Before moving on, consider the design of the church itself—a model of this complex is usually displayed in front of the altar. It’s actually a double church—one for the king and one for his soldiers—built long before Napoleon under Louis XIV in the 17th century. You’re standing in the “dome chapel,” decorated to the glory of Louis XIV and intended for royalty before it became the tomb of Napoleon. The original altar was destroyed in the Revolution. What you see today dates from the mid-1800s and was inspired by the altar and canopy at St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome.

• Step behind the altar (with the corkscrew columns), descend a flight of stairs, and look through the windows at the second church—the Church of St. Louis. This is where the veterans hospitalized here attended (mandatory) daily Mass. (You can enter the Church of St. Louis from the main courtyard—a quick and worthwhile detour.)

Before descending to the crypt level where Napoleon is buried, pause on the landing and face the doorway. It’s flanked by two bronze giants representing civic and military strength. The writing above the door is Napoleon’s “desire” (as the inscription reads) for his remains to be with the French people. And, like a welcome mat on the floor before you, a big inlaid N welcomes you into the tomb of perhaps the greatest military and political leader in French history.

Now go down the final flight of stairs and belly up to the banister around Napoleon’s Tomb.

Take a moment to absorb the majesty and symmetry of this tomb and the reverence Napoleon still enjoys from the French people.

Wander clockwise to find the names of Napoleon’s great battles on the floor circling the base of the tomb. Rivoli marks the battle where the rookie 26-year-old general took a ragtag band of “citizens” and thrashed the professional Austrian troops in Italy, returning to Paris a celebrity. In Egypt (Pyramides), he fought Turks and tribesmen to a standstill. The exotic expedition caught the public eye, and he returned home a legend.

Napoleon’s huge victory over Austria and Russia at Austerlitz—on the first anniversary of his coronation—made him Europe’s top dog. At the head of the million-man Great Army (La Grande Armée), he made a three-month blitz attack through Germany and Austria. As a military commander, he was daring, relying on top-notch generals and a mobile force of independent armies. His personal magnetism on the battlefield was said to be worth 10,000 additional men.

Pause to gaze at the grand statue of Napoleon the emperor in the alcove at the head of the tomb—royal scepter and orb of earth in his hands. By 1804, all of Europe was at his feet. He held an elaborate ceremony in Notre-Dame, where he proclaimed his wife, Josephine, empress, and himself—the 35-year-old son of humble immigrants—emperor. The laurel wreath, the robes, and the Roman eagles proclaim him the equal of the Caesars. The floor at the statue’s feet marks the grave of his son, Napoleon II (Roi de Rome, 1811-1832).

Circling the tomb on the crypt walls are relief panels showing Napoleon’s constructive side. Dressed in toga and laurel leaves, he dispenses justice, charity, and pork-barrel projects to an awed populace.

• In the first panel to the right of the statue...

He establishes an Imperial University to educate naked boys throughout “tout l’empire.” The roll of great scholars links modern France with figures of the past: Plutarch, Homer, Plato, and Aristotle.

Three panels later, his various building projects (canals, roads, and so on) are celebrated with a list and his quotation, “Everywhere he passed, he left durable benefits” (“Partout où mon regne à passé...”).

Hail Napoleon. Then, at his peak, came his most tragic errors.

• Turn around and look down to Moscowa (the Battle of Moscow—marked beneath his tomb).

Napoleon invaded Russia with 600,000 men and returned to Paris with 60,000 frostbitten survivors. Two years later, the Russians marched into Paris, and Napoleon’s days were numbered. After a brief exile on the isle of Elba, he skipped parole, sailed to France, bared his breast, and said, “Strike me down or follow me!” For 100 days, the French followed him, finally into Belgium, where the British and the Prussians hammered the French at the Battle of Waterloo (conspicuously absent on the floor’s décor—for more on this battle, see “From Louis XIV to Napoleon I,” near the end of this chapter).

Exiled again by a war tribunal, he spent his last years in a crude shack on the small South Atlantic island of St. Helena. When Napoleon died, he was initially buried in a simple grave. The epitaph was never finished because the French and British wrangled over what to call the hero/tyrant. The stone simply read, “Here lies...”

• To get to the Courtyard of Honor and the various military collections, exit Napoleon’s Tomb the same way you entered, make a U-turn right, and march past the cafeteria and ticket hall. Continue to the end of the hallway. Just before the courtyard, on the right, stairs lead up to the World War I and World War II exhibits. Go upstairs, following blue banners reading Les Deux Guerres Mondiales, 1871-1945. The museum is laid out so you first see the coverage of World War I, though some may choose to pass through this section quickly to reach the more substantial WWII section.

World War I (1914-1918) introduced modern technology to the age-old business of war. Tanks, chemical weapons, monstrous cannons, rapid communication, and airplanes made their debut, collaborating to kill nearly 10 million people in just four years. In addition, the war ultimately seemed senseless: It started with little provocation, raged on with few decisive battles, and ended with nothing resolved, a situation that sowed the seeds of World War II.

A quick walk-through of this 20-room exhibit leads you chronologically through World War I’s causes, battles, and outcome, giving you the essential background for the next world war. There’s good English information, but the displays are lackluster and low-tech: Move along quickly and don’t burn out before getting to the World War II wing.

Room 1: The first room bears a thought-provoking name: “Honour to the Unfortunate Bravery.” Paintings of dead and wounded soldiers from the Franco-Prussian War make it clear that World War I actually “began” in 1871, when Germany thrashed France. Suddenly, a recently united Germany was the new bully in Europe.

Rooms 2-3, France Re-bounds: Snapping back from its loss, France began rearming itself with spiffy new uniforms and weapons like the American-invented Gatling gun (early machine gun).

The French replaced the humiliation of defeat with a proud and extreme nationalism. Fanatical patriots hounded a (Jewish) officer named Alfred Dreyfus (display at the far left end) on trumped-up treason charges (1890s).

Rooms 4-6, Colonial Expansion: Europe’s nations were in a race for wealth and power, jostling to acquire lucrative colonies in Africa and Asia (uniforms). In a climate of mutual distrust, nations allied with their neighbors, vowing to protect each other if war ever erupted. In Room 6, a map of Europe in 1914 shows the division: France, Britain, and Russia (the Allies) teamed up against Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Italy (the Central Powers). Europe was ready to explode, but the spark that would set it off had nothing to do with Germany or France.

Room 7, Assassination and War Begins: Bang. On June 28, 1914, an Austrian archduke was shot to death (see video). One by one, Europe’s nations were dragged into the regional dispute by their webs of alliances. The Great War had begun.

Room 8, The Battle of the Marne: German forces swarmed into France, hoping for a quick knockout blow. Germany brought its big guns (photo and miniature model of Big Bertha). The projection map shows how the armies tried to outflank each other along a 200-mile battlefront. As the Germans (purple-gray arrows) zeroed in on Paris, the French (blue arrows) and British (“BEF”) scrambled to send 6,000 crucial reinforcements, shuttled to the front lines in 670 Parisian taxis (one is displayed nearby). The German tide was stemmed, and the two sides faced off, expecting to duke it out and get this war over quickly. It didn’t work out that way.

• The war continues upstairs.

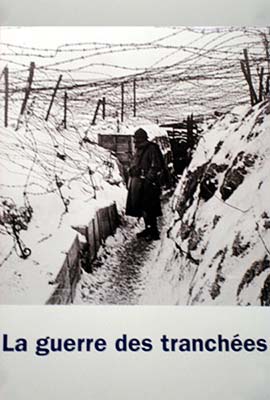

Rooms 9-10, The War in the Trenches: By 1915, the two sides reached a stalemate, and they settled in to a long war of attrition—French and Britons on one side, Germans on the other. The battle line, known as the Western Front, snaked 450 miles across Europe from the North Sea to the Alps. For protection against flying bullets, the soldiers dug trenches (tranchées), which soon became home—24 hours a day, seven days a week—for millions of men.

Life in the trenches was awful—cold, rainy, muddy, disease-ridden—and, most of all, boring. Every so often, generals waved their swords and ordered their men “over the top” and into “no-man’s-land.” Armed with rifles and bayonets, they advanced into a hail of machine gun fire. The “victorious” side often won only a few hundred yards of meaningless territory that was lost the next day after still more deaths. During the 10-month Battle of Verdun, France had about 400,000 casualties.

The war pitted 19th-century values of honor, bravery, and chivalry against 20th-century weapons: grenades, machine guns, tanks, and poison gas. To shoot over the tops of trenches while staying hidden, armies even invented crooked and periscope-style rifles.

Rooms 11-13, “World” War/Colonial Empires in the War (labeled 1917 in floor): Besides the Western Front, the war extended elsewhere, including the colonies, where many “natives” (see their uniforms) joined the armies of their “mother” countries. On the Eastern Front, Russia and Germany wore each other down. (Finally, the Russian people had had enough; they overthrew their czar, brought the troops home, and fomented a revolution that put communists in power.)

• Down a short hallway, enter Room 14.

Room 14, The Allies: By 1917, the Allied forces were beginning to outstrip the Central Powers, thanks to help from around the world. When Uncle Sam said, “I Want You,” five million Americans answered the call to go “Over There” (in the words of a popular song) and fight the Germans. The Yanks were not an enormous military factor, but their very presence signaled that the Allies seemed destined to prevail.

Room 15, Armistice (labeled 1918 in floor): In spite of a desperate last offensive by Generals Ludendorff and Hindenburg, the Germans were doomed. Under the command of French marshal Ferdinand Foch, the Allies undertook a series of offensives that would prove decisive. At the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month (November 11, 1918), the guns fell silent. Allied Europeans celebrated the Armistice with victory parades (see the newsreel footage of the Arc de Triomphe parade)...and then began assessing the damage.

Room 16, Costly Victory: After four years of battle, the war had left 9.5 million dead and 21 million wounded (see plaster casts of disfigured faces). A generation was lost, and France never fully recovered its “superpower” status.

Rooms 17-19, From 1918 to 1938: The Treaty of Versailles (1919), signed in the Hall of Mirrors, officially ended the war. A map shows how it radically redrew Europe’s borders. Germany was punished severely, leaving it crushed, humiliated, stripped of crucial land, and saddled with demoralizing war debts. Marshal Foch prophetically said of the Treaty: “This is not a peace. It is an armistice for 20 years.”

France, one of the “victors,” was drained, trying to hang on to its prosperity and its colonial empire. By the 1930s—swamped by the Great Depression and a stagnant military (dummy on horseback)—France was reeling, unprepared for the onslaught of a retooled Germany seeking revenge.

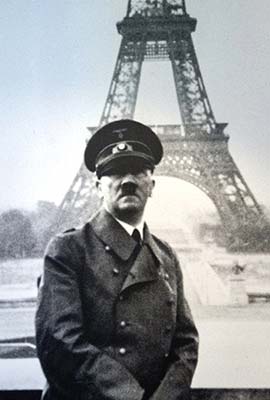

A photo of Adolf Hitler presages the awful events that came next.

• World War II is covered directly across the hall, in the rooms marked 1939-1942. Good WCs are nearby.

World War II was the most destructive of earth’s struggles. In this exhibit, the war unfolds in photos, displays, and newsreels, with special emphasis on the French contribution. (You may not have realized that it was Charles de Gaulle who won the war for us.) The museum takes you from Germany’s quick domination (third floor), to the Allies turning the tide (second floor), to the final surrender (first floor).

Be ready—displays come in rapid succession and flow into each other without obvious walls or dividers (look for room numbers in red on wall posters and find your way with the display labels). Ideally, read this tour before your visit as an overview of the vast, complex, and horrific global spectacle known as World War II.

On September 1, 1939, Germany, under Adolf Hitler, invaded Poland, starting World War II. But in a sense, the war had really begun in 1918, when the “war to end all wars” ground to a halt, leaving 9.5 million dead, Germany defeated, and France devastated (if victorious). For the next two decades, Hitler fed off German resentment over the Treaty of Versailles, which humiliated and ruined Germany.

After Hitler’s move into Poland, France and Britain mobilized. For the next six months, the two sides faced off, with neither actually doing battle—a tense time known to historians as the “Phony War” (Drôle de Guerre).

Then, in spring of 1940 came the Blitzkrieg (“lightning war”), and Germany’s better-trained and better-equipped soldiers and tanks (see turret) swept west through Belgium. France was immediately overwhelmed, and British troops barely escaped across the English Channel from Dunkirk. Within a month, Nazis were goose-stepping down the Champs-Elysées.

• A few paces farther along you see a large photo of...

Just like that, virtually all of Europe was dominated by fascists. During those darkest days, as France fell and Nazism spread across the Continent, one Frenchman—an obscure military man named Charles de Gaulle—refused to admit defeat. This 20th-century John of Arc had an unshakable belief in his mission to save France. De Gaulle (1890-1970) was born into a literate, upper-class family, was raised in military academies, and became a WWI hero and POW. But when World War II broke out, he was still only a minor officer with limited political experience who was virtually unknown to the French public.

After the invasion, de Gaulle escaped to London. From there he made inspiring speeches over the radio, beginning with a famous address broadcast on June 18, 1940. He slowly convinced a small audience of French expatriates that victory was still possible.

After France’s surrender, Germany ruled northern France, including Paris—see the photo of Hitler as a tourist at the Eiffel Tower. Hitler made a three-hour blitz tour of the city, including a stop at Napoleon’s Tomb. Afterward he said, “It was the dream of my life to be permitted to see Paris. I cannot say how happy I am to have that dream fulfilled today.”

The Nazis allowed the French to administer the south and the colonies (North Africa). This puppet government, centered in the city of Vichy, was right-wing and traditional, bowing to Hitler’s demands as he looted France’s raw materials and manpower for the war machine. (In the movie Casablanca, set in Vichy-controlled Morocco, French officials follow Nazi orders while French citizens defiantly sing “The Marseillaise.”)

Facing a “New Dark Age” in Europe, British prime minister Winston Churchill pledged, “We will fight on the beaches...We will fight in the hills. We will never surrender.”

In June 1940, Germany mobilized to invade Britain across the English Channel. From June to September, they paved the way, sending bombers—up to 1,500 planes a day—to destroy military and industrial sites. When Britain wouldn’t budge, Hitler concentrated on London and civilian targets. This was “The Blitz” of the winter of 1940, which killed 30,000 and left parts of London in ruins. But Britain hung on, armed with newfangled radar, speedy Spitfires, and an iron will.

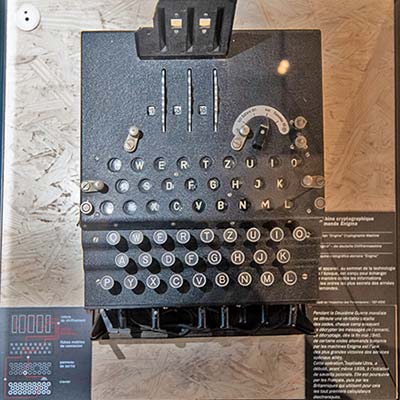

They also had the Germans’ secret “Enigma” code. The Enigma machine (in display case), with its set of revolving drums, allowed German commanders to scramble orders in a complex code that could be broadcast securely to their troops. The British (with crucial help from Poland) captured a machine, broke the code, then monitored German airwaves. (An Enigma machine co-starred with actor Benedict Cumberbatch, who played code-breaking mathematician Alan Turing, in the movie The Imitation Game.) For the rest of the war, Britain had advance knowledge of many top-secret plans, but occasionally let Germany’s plans succeed—sacrificing its own people—to avoid suspicion.

By spring of 1941, Hitler had given up any hope of invading the Isle of Britain. Churchill said of his people: “This was their finest hour.”

Perhaps hoping to one-up Napoleon, Hitler sent his state-of-the-art tanks speeding toward Moscow in June 1941 (betraying his former ally Joseph Stalin). By winter, the advance had stalled at the gates of Moscow and was bogged down by bad weather and Soviet stubbornness.

The Third Reich had reached its peak. Soon, Hitler would have to fight a two-front war. The French Renault tank (displayed) was downright puny compared with the big, fast, high-caliber German Panzers. This war was often a battle of factories, to see who could produce the latest technology fastest and in the greatest numbers. And what nation might have those factories...?

• In the corner is a glass case with a model of an aircraft carrier, announcing that...

On December 7, 1941, “a date which will live in infamy” (as US president Franklin D. Roosevelt put it), Japanese planes made a sneak attack on the US base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, and destroyed the pride of the Pacific fleet in two hours.

The US quickly entered the fray against Japan and her ally, Germany. In two short years, America had gone from isolationist observer to supplier of Britain’s arms to full-blown war ally against fascism. The US now faced a two-front war—in Europe against Hitler and in Asia against Japan’s imperialist conquest of China, Southeast Asia, and the South Pacific.

America’s first victory came when Japan tried a sneak attack on the US base at Midway Island (June 3, 1942). This time—thanks to the Allies who had cracked the Japanese code—America had the aircraft carrier USS Enterprise (see model) and two of her buddies lying in wait. In five minutes, three of Japan’s carriers (with valuable planes) were mortally wounded, their major attack force was sunk, and Japan and the US were dead even, settling in for a long war of attrition.

Though slow to start, the US eventually had an army 16 million strong, 80,000 planes, the latest technology, $250 million a day, unlimited raw materials, and a population of Rosie the Riveters fighting for freedom to a boogie-woogie beat.

• Continue downstairs to the second floor.

In 1942, the Continent was black with fascism, and Japan was secure on a distant island. The Allies had to chip away on the fringes.

German U-boats (short for Unterseeboot, meaning submarine) and battleships such as the Bismarck patrolled Europe’s perimeter, where they laid spiky mines to try to keep America from aiding Britain. (Until long-range transport planes were produced near war’s end, virtually all military transport was by ship.) The Allies traveled in convoys with air cover, used sonar and radar, and dropped depth charges, but for years they endured the loss of up to 60 ships per month.

Three crucial battles in the autumn of 1942 put the first chink in the fascist armor. Off the northeast coast of Australia, 10,000 US Marines (see kneeling soldier in glass case #14D) took an airstrip on Guadalcanal, while 30,000 Japanese held the rest of the tiny, isolated island. For the next six months, the two armies were marooned together, duking it out in thick jungles and malaria-infested swamps while their countries struggled to reinforce or rescue them. By February 1943, America had won and gained a crucial launch pad for bombing raids.

A world away, German tanks under General Erwin Rommel rolled across the vast deserts of North Africa. In October 1942, a well-equipped, well-planned offensive by British general Bernard (“Monty”) Montgomery attacked at El-Alamein, Egypt, with 300 tanks (see British tank soldier with headphones, #14F). Monty drove “the Desert Fox” west into Tunisia for the first real Allied victory against the Nazi Wehrmacht war machine.

In 1942, the Allies began long-range bombing of German-held territory, including saturation bombing of civilians. It was global war and total war.

Then came Stalingrad. In August 1942, Germany attacked the Soviet city, an industrial center and gateway to the Caucasus oil fields. By October, the Germans had battled their way into the city center and were fighting house-to-house, but their supplies were running low, the Soviets wouldn’t give up, and winter was coming. The snow fell, their tanks had no fuel, and relief efforts failed. Hitler ordered them to fight on through the bitter cold. On the worst days, thousands of men died. (By comparison, the US lost a total of 58,000 in Vietnam over 11 years.) Finally, on January 31, 1943, the Germans surrendered, against Hitler’s orders. The six-month totals for the Battle of Stalingrad? Eight hundred thousand German and other Axis soldiers dead, 1.1 million Soviets dead. The Russian campaign put hard miles on the German war machine.

A photo shows Winston Churchill, US president Franklin D. Roosevelt, and France’s Charles de Gaulle meeting to plan an indirect attack on Hitler by invading Vichy-controlled Morocco and Algeria. On November 8, 1942, 100,000 Americans and British—under the joint command of an unknown, low-key problem-solver named General Dwight (“Ike”) Eisenhower—landed on three separate beaches (including Casablanca). More than 120,000 Vichy French soldiers, ordered by their superiors to defend the fascist cause, confronted the Allies and...gave up. (Nearby, find displays of some standard-issue weapons: Springfield rifle, Colt 45 pistol, Thompson submachine gun, hand grenade.)

The Allies moved east, but bad weather, inexperience, and the powerful Afrika Korps under Rommel stopped them in Tunisia. But with flamboyant General George S. (“Old Blood-and-Guts”) Patton punching from the west and Monty pushing from the south, they captured the port town of Tunis on May 7, 1943. The Allies now had a base from which to retake Europe.

Inside occupied France, ordinary heroes—the underground Resistance—fought the Nazis. Jean Moulin (see photo), de Gaulle’s assistant, secretly parachuted into France and organized these scattered heroes into a unified effort.

Various displays show the Resistance’s efforts. Bakers hid radios within loaves of bread to secretly contact London. Barmaids passed along tips from tipsy Nazis. Communists in black berets cut telephone lines. Farmers hid downed airmen in haystacks. Housewives spread news from the front. Printers countered Nazi propaganda with pamphlets.

In 1943, Moulin was arrested by the Gestapo (Nazi secret police) and died. But Free France now had a (secret) government again, rallied around de Gaulle, and was ready to take over when liberation came.

Fans of Jean Moulin and the stirring Resistance story can explore it in greater depth at the Museum of Liberation and Jean Moulin, which opened in 2019 at Place Denfert-Rochereau (near the Catacombs, closed Mon, www.museeliberation-leclerc-moulin.paris.fr).

• Meanwhile, on the Eastern Front...

Monty, Patton, and Ike certainly were heroes, but the war was won on the Eastern Front by Soviet grunts, who slowly bled Germany dry. Maps show the shifting border of the Eastern Front.

• Bypass a couple of rooms to...

On July 10, 1943, the assault on Hitler’s European fortress began. More than 150,000 Americans and British sailed from Tunis and landed on the south shore of Sicily (see maps and video clips of the campaigns). Speedy Patton and methodical Monty began a “horse race” to take the city of Messina (the US won the friendly competition by a few hours). They met little resistance from 300,000 Italian soldiers and were actually cheered as liberators. Mussolini was arrested by his own people, and Italy surrendered. Hitler quickly poured 50,000 German troops into Italy, reinstalled Mussolini, and ordered Italy to fight on.

In early September, the Allies landed on the beaches of southern Italy. Finally, after four long years of war, free men set foot on the European continent. Lieutenant General Mark Clark led the slow, bloody push north to liberate Rome.

In January 1944, the Germans dug in between Rome and Naples at Monte Cassino, a rocky hill topped by the monastery of St. Benedict (see the large photo showing the obliterated abbey). Thousands died as the Allies tried inching up the hillside. In frustration, the Allies air-bombed the historic monastery to smithereens, killing many noncombatants...but no Germans, who dug in deeper. After four months of vicious, sometimes hand-to-hand combat by the Allies (Americans, Brits, Free French, Poles, Italian partisans, Indians, etc.), a band of Poles stormed the monastery, and the German back was broken.

Meanwhile, 50,000 Allies had landed near Rome at Anzio and held the narrow beachhead for months against massive German attacks. Finally, the Allied troops broke out and joined the assault on the capital. Without a single bomb threatening its historic treasures, Rome fell on June 4, 1944.

• Room 23 (with benches) shows a film on...

Three million Allies and six million tons of materiél were massed in England in preparation for the biggest fleet-led invasion in history—across the Channel to France, then eastward to Berlin. The Germans, hunkered down in northern France, knew an invasion was imminent, but the Allies kept the details top secret. On the night of June 5, 150,000 soldiers boarded ships and planes without knowing where they were headed until they were underway. Each one carried a note from General Eisenhower: “The tide has turned. The free men of the world are marching together to victory.”

At 6:30 a.m. on June 6, 1944, Americans spilled out of troop transports into the cold waters off a beach in Normandy, code-named Omaha (see the black-and-white newsreel projection). The weather was bad, seas were rough, and the prep bombing had failed. The soldiers, many seeing their first action, were dazed and confused. Nazi machine guns pinned them against the sea. Slowly, they crawled up the beach on their stomachs. A thousand died. The survivors held on until the next wave of transports arrived.

All day long, Allied confusion did battle with German indecision; the Nazis never really counterattacked, thinking D-Day was just a ruse, instead of the main invasion. By day’s end, the Allies had taken several beaches along the Normandy coast and begun building artificial harbors, providing a tiny port-of-entry for the reconquest of Europe. The stage was set for a quick and easy end to the war. Right.

• Go downstairs to the...

Through June, the Allies (mostly Americans) secured Normandy by taking bigger ports (Cherbourg and Caen) and amassing troops and supplies for the assault on Germany. In July, they broke out and sped eastward across France, with Patton’s tanks covering up to 40 miles a day. They had “Jerry” on the run.

On France’s Mediterranean coast, American troops under General Alexander Patch landed near Cannes (see the big photo of the sky filled with parachutes), took Marseille, and headed north to meet up with General Patton. A tiny theater shows happy liberation scenes as France is freed city by city.

French Resistance guerrilla fighters helped reconquer France from behind the lines. (Don’t miss the folding motorcycle in its parachute case.) The liberation of Paris was started by a Resistance attack on a German garrison.

As the Allies marched on Paris, Hitler ordered his officers to torch the city—but they sanely disobeyed and prepared to surrender. A video shows the exhilaration of August 26, 1944, as General Charles de Gaulle walked ramrod-straight down the Champs-Elysées, followed by Free French troops and US GIs passing out chocolate and Camels. Two million Parisians went crazy.

The quick advance from the west through France, Belgium, and Luxembourg was bogged down at the German border in autumn of 1944. Patton outstripped his supply lines, an airborne and ground invasion of Holland (the Battle of Arnhem) was disastrous, and bad weather grounded planes and slowed tanks.

On December 16, the Allies met a deadly surprise. An enormous, well-equipped, energetic German army appeared from nowhere, punched a “bulge” deep into Allied territory through Belgium and Luxembourg, and demanded surrender. General Anthony McAuliffe sent a one-word response—“Nuts!”—and the momentum shifted. The Battle of the Bulge was Germany’s last great offensive.

The Germans retreated across the Rhine River, blowing up bridges behind them. But one bridge, at Remagen, was captured by the Americans and stood just long enough for GIs to cross and establish themselves on the east shore of the Rhine. Soon US tanks were speeding down the autobahns and Patton could wire the good news back to Ike: “General, I have just pissed in the Rhine.”

Soviet soldiers did the dirty work of taking fortified Berlin by launching a final offensive in January 1945 and surrounding the city in April. German citizens fled west to surrender to the more-benevolent Americans and Brits. Hitler, defiant to the end, hunkered in his underground bunker. (See photo of ruined Berlin.)

On April 28, 1945, Mussolini and his girlfriend were killed and hung by their heels in Milan. Two days later, Adolf Hitler and his new bride, Eva Braun, avoided similar humiliation by committing suicide (pistol in mouth and poison) and having their bodies burned beyond recognition. Germany formally surrendered on May 8, 1945.

• To the left, in the adjoining room, don’t miss the exhibits on...

Lest anyone mourn Hitler or doubt this war’s purpose, gaze at photos from Germany’s concentration camps. Some camps held political enemies and prisoners of war, including two million French. Others were expressly built to exterminate people considered “genetically inferior” to the “Aryan master race”—particularly Jews, Roma, homosexuals, and the mentally ill.

Often treated as an afterthought, the final campaign against Japan was a massive American effort, costing many lives but saving millions of others from Japanese domination.

Japan was an island bunker surrounded by a vast ring of fortified Pacific islands. America’s strategy was to take one island at a time, “island-hopping” until close enough for B-29 Superfortress bombers to attack Japan itself. The battlefield spread across thousands of miles. In a new form of warfare, ships carrying planes led the attack and prepared tiny islands (such as Iwo Jima) for troops to land on and build airfields. While General Douglas MacArthur island-hopped south to retake the Philippines (“I have returned!”), others pushed north toward Japan.

On March 9, Tokyo was firebombed, and 90,000 were killed. Japan was losing, but a land invasion would cost hundreds of thousands of lives. The Japanese had a reputation for choosing death over the shame of surrender—they even sent bomb-laden “kamikaze” planes on suicide missions.

America unleashed its secret weapon, an atomic bomb (originally suggested by German-turned-American Albert Einstein). On August 6, a B-29 dropped one (named “Little Boy,” see the replica dangling overhead) on the city of Hiroshima and instantly vaporized 100,000 people and four square miles. Three days later, a second bomb fell on Nagasaki. The next day, Emperor Hirohito unofficially surrendered. The long war was over, and US sailors returned home to kiss their girlfriends in public places.

The death toll for World War II, tallied from September 1939 to August 1945, totaled 80 million soldiers and civilians. The Soviet Union lost 26 million, China 20 million, France 580,000, and the US 340,000. The Nazi criminals who started the war and perpetrated war crimes were tried and sentenced in an international court—the first of its kind—held in Nürnberg, Germany.

World War II changed the world, with the US emerging as the dominant political, military, and economic superpower. Europe was split in two. The western half recovered, with American aid. The eastern half remained under Soviet occupation. For 45 years, the US and the Soviet Union would compete—without ever actually doing battle—in a “Cold War” of espionage, propaganda, and weapons production that stretched from Korea to Cuba, from Vietnam to the moon.

• Exit through the shop and turn left. The next three exhibits are located on the east side of the large Courtyard of Honor (where Napoleon honored his troops, Dreyfus had his sword broken, and de Gaulle once kissed Churchill). Follow From Louis XIV to Napoleon III signs. Start upstairs on the second floor (elevator available).

This display traces the evolution of uniforms and weapons through France’s glory days, with the emphasis on Napoleon Bonaparte. As you circle the second floor, the exhibit unfolds chronologically in four parts: the Ancien Régime (Louis XIV, XV, and XVI), the Revolution, the First Empire (Napoleon), and the post-Waterloo world. Most exhibits have helpful English information.

This museum is best for browsing, but I’ve highlighted a handful of the (many) exhibits to get you started. Room numbers are posted on doorjambs. Prepare to search for good light to read in these dimly lit rooms.

Louis XIV unified the army as he unified the country, creating the first modern nation-state with a military force. Along the central hall you’ll see glass cases of 1 weapons. Gunpowder was quickly turning swords, pikes, and lances to pistols, muskets, and bayonets. Uniforms became more uniform, and everyone got a standard-issue flintlock.

At the end of the hall, a display case has some amazingly big and 2 odd-shaped rifles. Nearby, there’s a video on weapons and a tabletop projection screen showing a reenactment of the 3 Battle of Fontenoy (in present-day Belgium) in 1745. Put on headphones and watch how the French established their superiority on the Continent.

• Turn the corner and enter...

Room 13 features the 4 American War of Independence. You’ll see the sword (épée) of the French aristocrat Marquis de La Fayette (near his bust), who—full of revolutionary fervor—sailed to America, where he took a bullet in the leg and fought alongside George Washington.

After France underwent its own Revolution, the king’s Royal Army became the people’s National Guard, protecting their fledgling democracy from Europe’s monarchies while spreading revolutionary ideas by conquest.

Midway down Hall 2, find the large 5 model of the Battle of Lodi in 1796 (push the English-language button). The French and Austrians faced off on opposite sides of a northern Italian river, each trying to capture a crucial bridge. The model shows the dramatic moment when the French cavalry charged across the bridge, overpowering the exhausted Austrians. They were led by a young, relatively obscure officer who had distinguished himself on the battlefield and quickly risen through the ranks—Napoleon Bonaparte. Stories spread that it was the brash General Bonaparte himself who personally sighted the French cannons on the enemy—normally the job of a lesser officer. It turned the tide of battle and earned him a reputation and a nickname, “the Little Corporal.”

Rooms 19-21 chronicle the era of 6 Napoleon as emperor. While pledging allegiance to Revolutionary ideals of democracy, Napoleon staged a coup and soon ruled France as a virtual dictator. In Room 19 you’ll see General Bonaparte’s hat, sword, and medals. In 1804, Napoleon donned royal robes and was crowned Emperor. The famous portrait by J. A. D. Ingres shows him at the peak of his power, stretching his right arm to supernatural lengths. The ceremonial collar and medal he wears in the painting are normally displayed nearby, as are an eagle standard and Napoleon’s elaborate saddle.

Continue to the end of Hall 2 to find 7 Napoleon’s beloved Arabian horse. Le Vizir weathered many a campaign with Napoleon, grew old with him in exile, and now stands stuffed and proud.

Ambitious Napoleon plunged France into draining wars against all of Europe. In Room 29 (midway down the hall), you’ll find 8 Napoleon’s tent and bivouac equipment: a bed with mosquito netting, a director’s chair, his overcoat, and a table where you can imagine his generals hunched over as they made battle plans.

Napoleon’s plans to dominate Europe ended with disastrous losses when he attempted to invade Russia. The rest of Europe ganged up on France, and in 1814 Napoleon was forced to abdicate. At the end of the hall, find Room 35 with a 9 portrait of a crestfallen Napoleon, now replaced by King Louis XVIII (whose bust stands opposite). Napoleon spent a year in exile on the isle of Elba. In March of 1815, he escaped, returned to France, rallied the army, and prepared for one last hurrah.

• Turning the corner into Hall 4, you run right into what Napoleon did—Waterloo.

Study the tabletop projection that maps the course of the history-changing 10 Battle of Waterloo, fought on the outskirts of Brussels, June 15-19, 1815.

On June 18, 72,000 French (the blue squares) faced off against the allied armies of 68,000 British-Dutch under Wellington (red and yellow) and 45,000 Prussians under Blücher (purple). Napoleon’s only hope was to keep the two armies apart and defeat them individually.

First, Napoleon’s Marshal Ney advances on the British-Dutch, commanded by the Prince of Orange. Then the French attack the Prussians on the right. They rout the Prussians, driving them north. Napoleon’s strategy is working. Now he prepares to finish off Wellington.

On the morning of June 18, Wellington hunkers down atop a ridge at Waterloo. Napoleon advances, and they face off. Nothing happens. Napoleon decides to wait two hours to attack, to let the field dry—some say it was his fatal mistake. Finally, Napoleon attacks from the left flank. Next, he punches hard on the right. Wellington pushes them back. Meanwhile, the Prussians are advancing from the right, so Napoleon sends General Mouton to check it out. Napoleon realizes he must act quickly or fight both armies at once. He sends General Ney into the thick of Wellington’s forces. Fierce fighting ensues. Ney is forced to retreat. The Prussians advance from the right. It’s a two-front battle. Caught in a pincer, Napoleon has no choice but to send in his elite troops, the Imperial Guard, who have never been defeated. The British surprise the Guard in a cornfield, and Wellington swoops down from the ridge, routing the French. By nightfall, the British and Prussian armies have come together, 12,000 men have died, and Napoleon’s reign of glory is over.

Napoleon was sent into exile on St. Helena. Once the most powerful man in the world, Napoleon spent his final years as a lonely outcast suffering from ulcers, dressed in his nightcap and slippers, and playing chess, not war.

The French monarchy was restored with King Louis XVIII in charge.

• Continuing on and crossing a hall, you’ll enter rooms dedicated to “The Rebirth of the Empire” and learn about 11 Napoleon III, the emperor of France in the 1850s and the nephew of the great Napoleon Bonaparte. Picking up where his uncle left off, he would lead France into many battles, most famously the disastrous Franco-Prussian war—but that’s a whole other story. Our tour here is done.

The east wing also houses the next two exhibits:

Musée des Plans-Reliefs: On the top floor of the east wing, this exhibit displays large-scale 18th-century models of many French cities (1:1600 scale) that strategists used to thwart enemy attacks. Survey Toulon and ponder which hillside you’d use to launch an attack; good luck figuring out an easy way to attack the deeply set town of Villefranche-de-Conflent.

• If you still have an appetite for French military history, take the stairs or elevator down to the basement and find the impressive...

Charles de Gaulle Exhibit: This memorial one floor below ground level brings France’s history of war into the modern age. The exhibit leads you through the life of the greatest figure in 20th-century French history. A 25-minute documentary with few words runs twice per hour. You can use the free audioguide, or just circle clockwise and let the big photos and video images tell de Gaulle’s life story:

It starts in 1890 with a few childhood photos and posters capturing the 19th-century French world that shaped him. During World War I, de Gaulle fought bravely at Verdun. In the 1920s, as a “soldier-writer,” he rose through the ranks ghostwriting for the war hero Marshal Pétain. As fascism rose in the 1930s, de Gaulle encouraged France to modernize its armies.

When World War II broke out in 1939 and France capitulated, de Gaulle refused to collaborate with the Nazis and went into exile. He became the head of “La France Libre” (Free France)—the small unoccupied territories of French people around the world. He was instrumental in France’s liberation in 1944 and led the parade down the Champs-Elysées.

After helping to defeat Hitler, de Gaulle, like Dwight Eisenhower, turned to politics. He led the nation for a decade (1958-69) as its president. But in 1968, student protests and worker strikes eventually toppled him. Today, he’s honored as something much more than just an airport.

• Back on the west side of the Courtyard of Honor is the exhibit called...

Arms and Armor: Here you’ll discover every size, shape, and style of body armor and swords. The collection’s highlight (to the right down the hall when you enter—if not on loan) is the suit of armor of France’s great Renaissance king, François I, decorated with fleur-de-lis. He sits astride his horse, fitted out in matching armor. You’ll find two other impressive horse-mounted knights in armor down the central hall and to the right. In these halls, connoisseurs of medieval armor, cannons, swords, pikes, crossbows, and early guns can swoon over the collection of weapons from the 13th to 17th century; others can browse a few rooms and move on.

More Sights: If you still haven’t had enough of dummies in uniforms and endless glass cases of muskets, there’s more. The Museum of the Order of Liberation, near the souvenir shop, honors heroes of the WWII Resistance.