23

ART CONNECTIONS

Robert Pepperell

In art there is only one thing that counts: the thing you can’t explain.

Georges Braque

Too precise a meaning erases your mysterious literature.

Stéphane Mallarmé

The most beautiful emotion we can experience is the mysterious.

Albert Einstein

Introduction

We live in a time when dialogue between the arts, sciences, and humanities is widely encouraged. Funding agencies offer incentives for scientists to work with artists; books are being written that seek to span C.P. Snow’s “gulf of mutual incomprehension” between scholarly cultures (see Wilson 1998); interdisciplinary conferences are being convened that support cross-area dialogue and report the findings of collaborative projects. There is a sense that previously disconnected fields of study are actively converging.

All this is welcome, given the fractured state of contemporary knowledge. Born just over 400 years ago, the poet John Milton is reputed to be the last person who would have been able to read every book then in print. Certainly the well-educated person of his time would have understood a wide range of subjects. The subsequent tendency towards micro-specialism in academia has brought breadth and depth at the price of fragmentation and isolation; no longer could any individual hope to absorb more than a tiny fraction of published information, and most disciplines work in ignorance of each other. Ulrich’s directory of periodicals (Ulrich’s 2009), which lists most of the world’s scholarly journals, boasts over 300,000 titles, each representing the tip of an iceberg of accumulated knowledge. And a report in 2002 by the Association of American Colleges and Universities identified the “atomization of the curriculum,” caused by artificially dividing knowledge into distinct fields, as a significant barrier to the future of education (AACU 2002).

But a note of caution: if we embrace interdisciplinarity as an antidote to over-specialization we should be wary of negating the foundational and historical differences among disciplines. In the introduction to his lucid and comprehensive survey of human thought, The Story of Philosophy, Bryan Magee divides the great span of human knowledge into four major areas: religion, which relies on faith; art, which relies on intuition; science, which operates through experiment; and philosophy, which proceeds through argument (Magee 2001: 8). Although not exhaustive, these groupings can guide us in understanding the overall organization of human knowledge, as well as in capturing the distinct approaches to understanding that each area offers. Putting religion aside as beyond the scope of the current volume, this chapter considers the ways in which art, literature, and science might be connected, and to some extent unified in a wider interdisciplinary project. As I hope will become clear, however, being connected or even unified does not necessarily mean surrendering disciplinary differences.

Interdisciplinarity: homogeneity or plurality?

Anxiety about the fragmentation of knowledge dates back at least to the late nineteenth century. The great anatomist and advocate of Darwinian evolution Thomas Henry Huxley was deeply committed to science, yet argued publicly that art and literature (what we would now call the humanities) are not only equal to science in importance but basically identical in purpose and process. In one of several addresses he made to the Royal Academy, then the foremost artistic institution in Britain, he warned of the dangers of excessive specialization in science and bid for recognition of “the great truth that art and literature and science are one, and that the foundation of every sound education and preparation for active life in which a special education is necessary should be some efficient training in all three” (Huxley 1887). Huxley was a keen draughtsman and produced many of the scientific illustrations for his own publications and lectures, as well as numerous cartoons and caricatures of contemporary figures. He was an autodidact and something of a polymath for whom the beauty of nature revealed through the scientific method was no different in essence from that revealed by art or philosophy: each seeks to penetrate “the mystery and wonder which are around us” (Huxley 1887).

The publications on meteorology and geology of Huxley’s learned contemporary John Ruskin are less well known than his still widely read works on art and aesthetics. Like Huxley, he was to a large extent self-taught, published voluminously, and engaged in many of the social and intellectual issues of his day. Ruskin, however, would lay greater stress on the intrinsic differences between science, art, and literature, noting in one of his Oxford lectures that “In science, you must not talk before you know. In art, you must not talk before you do. In literature, you must not talk before you think” (Ruskin 1872: 4). For Ruskin, the proper places for the study of science (in Victorian England at least) were the institutions regulated by the Royal Society, where factual knowledge about nature was generated and deposited. The “fine and mechanical” arts, meanwhile, were the province of the Royal Academy and its schools, which cultivated skills proper to the artist or architect. Ruskin counted within literature intellectual or philosophical ideas, which were to be nurtured by the universities.

Ruskin’s concept of “literature” is akin to what C.P. Snow conceived as one half of the “two cultures” in his famous characterization of the intellectual landscape of the mid-twentieth century, the opposing other being science, and in particular the hard sciences of physics and chemistry. Trained as a physicist and later becoming a distinguished novelist, Snow was well placed to assess the academic milieu of his day. This led him in his 1959 Rede lecture to bemoan the “sheer loss to us all” of the polarization between, on the one hand, the “traditional” culture of the humanities (philosophers, intellectuals, writers) and the highly specialized domains of the physical sciences, on the other hand (Snow 1993: 11). The inability of both to speak a common language had damaging consequences for our culture as a whole. Like Huxley, Snow advocated reform of the educational system in order to repair the damage at its root. Such pronouncements on the relationship between science, art, and the world of letters reveal not just the conventional tension between disciplinary cultures but between different ways of conceiving how interdisciplinarity might be made to work in practice: either we try to unify the various strands of knowledge by eliminating their distinctions on the basis that, as Huxley would have it, they are essentially homogeneous, or we maintain the plurality of distinctions (as Ruskin would do), albeit encouraging informed reflection or Snow’s educational reforms to keep them in balance.

If we think interdisciplinarity is worthwhile – perhaps even essential to the development of knowledge – then we must decide whether we are seeking a kind of integration that is homogeneous or pluralistic. Do we focus only on the common ground between historically distinct areas, or do we embrace these distinctions and try to reconcile them without compromising their integrity? In either case, in order to achieve a fully interdisciplinary form of inquiry we should expect that each area be given equal standing, and for each to contribute to the advancement of the other.

A recent case of interdisciplinarity

The interaction of the artistic imagination and scientific inquiry is enjoying unprecedented attention.

(Warner 2000)

As novelist Marina Warner noted, the beginning of the twenty-first century has seen a conspicuous convergence of art, science, and humanities, nowhere more evident than in the avowedly interdisciplinary field of consciousness studies. In the early 1990s philosophers, neuroscientists, psychologists, and cognitive scientists had recognized that the problem of explaining human consciousness was too deep and far-reaching to be accounted for by any single discipline, and so began formally discussing common approaches and sharing knowledge. An example of such cooperation is the biennial “Towards a Science of Consciousness” series of conferences organized since 1994 by the University of Arizona, Tucson.

One publication that has reflected this convergence is the Journal of Consciousness Studies, which, unusually for specialist journals, solicited contributions from a range of disciplines, even encouraging debate on the neural basis of art. It published three special issues on “Art and the Brain” (1999, 2000, 2004) and a more recent special edition devoted to Velazquez’s Las Meninas (2008). These issues have featured contributions from eminent scientists and philosophers, including Bernard Baars, Richard Gregory, Nicholas Humphrey, Alva Noë, and V.S. Ramachandran, each addressing what the study of art could reveal about the workings of the human mind.

The same decade saw the publication of a number of books that further suggested a rapprochement between art and science (Zeki 1999; Livingstone 2002; Solso 2003; Zangemeister and Stark 2007). Semir Zeki’s original work on the neuroscientific processes involved in the perception of art has spawned a nascent hybrid discipline – neuroaesthetics – that seeks to give an account of aesthetic perception on the basis of what is known about the biology of the brain. This new field is attracting investigators and a growing literature, with a substantial volume of related texts being published (Martindale 2006), and at least two international conferences being convened in 2009. All this demonstrates the considerable level of interest in art from scientists and philosophers of mind, and indicates a growing climate of cross-disciplinary inquiry. At the same time, we’ve seen a growth in creative art–science collaborations, where artists and scientists have sought to share knowledge and methods in making works of art, as well as many cases where artists have embraced technologies like genetic manipulation, digital media, and robotics because of their potential as new artistic mediums.

Does all this activity represent a genuine convergence of knowledge, of a kind perhaps not seen since the Renaissance, in which artists, technologists, scientists, and philosophers are starting to establish common grounds of inquiry? Could this even represent the beginning of the end for disciplinary boundaries between art, science, and the humanities as we have known them? Much as this might be welcomed, I doubt it is yet so. It turns out that the recent interest in art by science and philosophy consists for the most part in scientists and philosophers using their specialist knowledge to make low-level interventions in art theory. What is less evident – indeed almost entirely absent – among the recent literature and conferences on the relationship between art, brain, and mind is the voice or presence of the artists themselves. Only one of the many contributors to the special issues of Journal of Consciousness Studies has an art-making background, while none of the contributors to Martindale’s volume on neuroaesthetics does. With a background as an art historian, John Onians (2008) at least starts to reverse this trend by assimilating his art-historical knowledge with recent findings in neuroscience. And even though Semir Zeki can claim “artists are neurologists” (Zeki 1999: 80) because they have intuitively understood the organizing principles of the visual brain, it is unlikely that any artists will be invited to expound their theories on the basic principles of neuroscience in the way neuroscientists have on the basic principles of art. To date, artists are, by and large, subjects of rather than participants in this discussion.

Meanwhile, the commercial art world remains to be convinced about the long-term merit of much of the “art-science” work being made, with few resulting pieces making it beyond the realms specifically created to fund them. And the extent to which these ventures have contributed to the real advancement of science and technology is even less certain. The science director of the British Council raised serious doubts about the value to either community of the projects funded by the Sciart initiative operated by the Wellcome Trust, saying little good work had resulted (Times Higher Education Supplement 2005). Despite all the recent enthusiasm for integration between the arts, sciences, and humanities, it is hard to point to examples of genuinely equitable collaboration resulting in significant contributions to knowledge, understanding, and methods in all areas concerned. True interdisciplinary integration, where parity and mutual advancement are evident, still seems some way off.

The methods of science, philosophy, and art

If we compare the methods of science and philosophy to those of art we are struck by some important differences. In the scientific method investigators are subject to a number of tight constraints on how they can maneuver: the hypothesis must be testable; phenomena under investigation must be measurable; errors, ambiguities, and subjective bias must be eliminated; interpretations must strictly adhere to the data; the principles of reason must be adhered to. These constraints are essential if the integrity and universality of scientific findings are to be upheld. In philosophy similar though arguably less severe constraints apply: subjectivity is discouraged and rigorous rules of argument must be followed in which logical consistency is considered essential. Philosophy differs most substantially from science in that its propositions are generally tested through argument instead of experiments, and this allows philosophy to interrogate the kinds of conceptual problems that would be beyond the means of science to investigate.

Professional artistic activity is also constrained by numerous codes of conduct, but their purpose and outcome can be very different than those of science and philosophy. While in science it is perfectly acceptable to repeat the experimental procedures of another scientist, in art one should avoid repeating the work of another artist. Likewise, where scientists and philosophers are expected to explain their deliberations and findings as explicitly as possible, artists prefer to avoid explanations of their work, which, as Magee pointed out, is often arrived at intuitively. And where the work of scientists and philosophers should ideally remain clear and logically coherent, it is often desirable for artists that their work remains ambiguous, enigmatic, and even provocatively irrational. Artists work within rules, but ones that are different, and in many cases entirely contradictory to those of professional science and philosophy. The fact that the methods of science and philosophy have far more in common with each other than either do with art may start to account for the lack of parity so far evident in recent interdisciplinary activity.

A function of art

What I am trying to convey to you is more mysterious; it is bound up with the very roots of being, in the intangible source of sensation.

(Paul Cézanne, cited in Kendall 2001: 303)

There is a further difference between art compared to science and the humanities. All major areas of human inquiry ultimately seek to understand the mysterious aspects of existence and reality. The essence of any kind of inquiry is to delve into what is not already known. But (with the possible exception of religion) art is the only one that approaches this task by becoming mysterious itself. The philosopher Schopenhauer refers to the boundless and inaccessible essence of nature when invoking his concept of the Will, just as Einstein reaches into the cosmological unknown he called the “most beautiful emotion” through theoretical physics. But the works produced in response to these investigations are not in themselves mysterious, they are about mysteries. Velazquez’s Las Meninas (1656, Museo del Prado, Madrid), on the other hand, is a riddle wrapped in an enigma, a painting that presents the facts of daily existence as at the same time quotidian and inexhaustibly perplexing. Science and philosophy are well equipped to investigate the unknown, but are professionally bound to produce outcomes that are conceptually transparent – at least to those in the relevant communities. After all, if objectivity is a major criterion of validity, then wide consensus and understanding is desirable. Artists, meanwhile, may be concerned with similar questions about the nature of perception, mind, and reality as scientists and philosophers, but are apt to produce outcomes that, at their best, are far more open to subjective interpretation, even to the point of indecipherability.

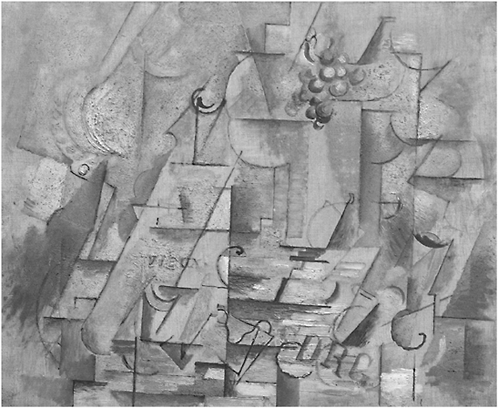

I briefly offer as an example a Cubist painting produced by Braque in the period leading up to World War I Figure 23.1). During this so-called “analytic”

Figure 23.1 Georges Braque. Fruit Dish, Bottle, and Glass: “Sorgues”, 1912. Oil and sand on canvas, 60 x 73 cm. Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris. Gift of Louise and Michel Leiris. © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2009.

period of Cubism the artist presented scenes of ordinary domestic objects – bottles, glasses, bowls, fruit, a table – in a way that is utterly extraordinary. Everything is present, everything is represented, but in a way that defies recognition (certainly for the untrained viewer). The painting, in this sense, is highly indeterminate. For Braque, the Cubist collaboration with Picasso was nothing less than a refashioning of the very act of pictorial representation. A painting need no longer “look like” what it represented in order to be a veridical depiction. Instead, abrupt, truncated, and fragmented iconic signs could stand in for objects to which they bore little physical resemblance.

Moreover, Cubism can be seen as a refashioning of the idea that perception gives us direct knowledge of the world as it is “out there.” For although we imagine we see a world of complete objects, in fact what we really see is hesitant, fleeting, partial, fractured, and often uncertain. We know from work in vision science that our rich picture of the world is actually built up from momentary fixations in our visual field captured by the tiny fovea centralis (Palmer 1999: 528). From a young age we have to learn to scan and “read” the world, just as we have to learn to read a book or a Cubist painting, in order to extract comprehensible information from the fragmented images we apprehend. Until we can do this, the world remains indeterminate and essentially mysterious, much as in the Cubist work considered here.

For many artists, art is a method by which we explore the extreme reaches of what we know, but in a way quite different from philosophy and science. Rather than trying to solve mysteries, artists are more frequently trying to create them, using the everyday materials of reality to offer signposts into the unknown.

My aim is always to get hold of the magic reality and to transfer this reality into painting – to make the invisible visible through reality. It may sound paradoxical, but it is, in fact, reality which forms the mystery of our existence.

(Max Beckmann, cited in Protter 1997: 211)

This impulse is most apparent in the tradition of religious art in which artistic objects come to represent, or stand in for, invisible spirits or deities. Modern art at its best trades on that same tradition in which the object is venerated not because of its intrinsic material value but for what it offers beyond itself in terms of transcendent experience. A review of the Mark Rothko show in London in 2008 talked of “intimations of something beyond the material,” so attesting to the continuing potency of this belief:

Sitting among the paintings for the Four Seasons restaurant, engulfed by the brooding ox-bloods and burgundies of those enormous canvases you do feel a sense of awe appropriate to a place of worship. The fact that this sense of reverence is almost impossible to quite define is the essence of Rothko’s appeal.

(Hudson 2008)

Art is often spoken of in such reverential and indefinable terms, as though it takes over where language gets off, drawing up to the edge of the known and leading us beyond – into something indeterminate. Hence art’s reputation for difficulty, willful abstruseness, and yet also profundity, a profundity that is of adifferent order than that produced by works of science or philosophy. Writing of Paul Cézanne, Maurice Merleau-Ponty contends that art avoids imposing on primordial experience both the rational coding or operationalism of science and the linguistic determinism of philosophy:

Now art, especially painting, draws upon this fabric of brute meaning which operationalism would prefer to ignore. Art and only art does so in full innocence. From the writer and the philosopher, in contrast, we want opinions and advice. We will not allow them to hold the world suspended. We want them to take a stand; they cannot waive the responsibilities of humans who speak.

(Merleau-Ponty, cited in Johnson 1996: 123)

Indeterminacy in literary theory

Writers who have attempted to capture the essence of our relationship to art (both visual and literary) have often made reference to the indeterminacy of perception in which the familiar world is momentarily disturbed by the effect of a work of art. The critic Victor Shklovsky developed an aesthetic theory in which art’s function is to resist what he calls our perceptual habitualization, whereby we become unconsciously accustomed to the world as it appears to us and therefore oblivious to the world “as it is” prior to our acquired perception of it. The purpose of art, according to Shklovsky, writing in 1917, is to defamiliarize our perceptions of the world: “The technique of art is to make objects ‘unfamiliar,’ to make forms difficult, to increase the difficulty and length of perception because the process of perception is an aesthetic end in itself and must be prolonged” (Shklovsky 1965: 12).

Although Shklovsky is primarily referring to literature, the aesthetic function he describes could just as well be applied in the case of the visual arts, and in particular the kind of painting considered here. Similar sentiments had been proposed in the previous century in relation to Symbolist theories of poetry. Speaking in 1891, when the impact of Impressionist methods had contributed to reshaping the intellectual and artistic climate of France, the poet Stéphane Mallarmé asserted:

To name an object is to suppress three-quarters of the enjoyment of the poem, which derives from the pleasure of step-by-step discovery; to suggest, that is the dream. It is the perfect use of this mystery that constitutes the symbol: to evoke an object little by little.

(cited in Dorra 1995: 141)

Mallarmé and Shklovsky both stress a criterion for aesthetic efficacy in which art is enigmatic and evocative to the imagination and at the same time difficult to decipher, so problematizing the processes of perception and cognition. They call for a suspension of those customary or facile modes of attention where we are either oblivious to the raw perceptual qualities of the world or offered representations that leave no room for imaginative interpretation. Instead, they each urge that the habitual link between seeing and knowing be loosened or broken in order to raise the aesthetic value of our experience.

More recently, the author A.S. Byatt has ambitiously linked the theories of neuroscientist Jean-Pierre Changeux to the poetic effects of John Donne’s poetry. In doing so, she accounts for the neural impact of Donne’s poetry through the imaginative struggle required to grasp its meaning, arguing that “some of Donne’s most beautiful effects are derived from the foregrounding of the difficulty and complexity – and density – of grammatical constructions” (Byatt 2006). Clearly, critics and writers remain interested in the perceptual and cognitive processes through which art is appreciated, and are perhaps intuitively aware of why certain works have the psychological impact they do. Combining the insights of creative thinkers with the investigative techniques of modern neuroscience, in the way suggested by Byatt, may offer genuinely new avenues of interdisciplinary knowledge, providing that all contributors can find common ground that does not require them to relinquish their disciplinary integrity.

The potential for interdisciplinary knowledge

Art (including literary art), science, and the humanities can justly claim common ground: they share an aspiration to bring us into closer contact with the unknown aspects of existence. But they also have different histories, trajectories, and methods that cannot be lightly overwritten. Most importantly, art stands aside from philosophy and science insofar as artworks are made less to explain the mysteries of existence than to invoke them; something often achieved by presenting the world as difficult, unfamiliar, or indeterminate. Science and the humanities, on the other hand, are more strongly compelled to explain these mysteries, and present their findings in ways that are coherent and transparent. This may go some way in accounting for the disparities that occur when art, science, and philosophy are brought together, and for why artists are inclined to let the artworks carry their voice instead of engaging more directly in the debates themselves.

Looking broadly across Western culture, we see that the impulse to explain, which science and philosophy share through their deep roots in Greek thinking and common heritage in natural philosophy, has never driven art in the same way. Instead, art had an artisan heritage that the Church put to the task of manifesting the invisible, thus bringing it into direct contact with the divine. A painting or a musical composition alone can explain nothing (even a diagram needs annotation), precisely as Merleau-Ponty says, because neither speaks. The fact that Leonardo da Vinci artfully creates Mona Lisa’s indeterminate smile while Margaret Livingstone seeks to explain it by reference to analysis of spatial frequencies (Livingstone 2002) encapsulates the fundamental difference between art and science.

And even to the extent that literary art and poetry speak, they often do so, as Mallarmé would have it, only enough to push the mind of the reader beyond what the words say. It is apt that the physicist Werner Heisenberg’s realization of the limits of what can be known about reality at the quantum level should be named the “Indeterminacy Principle.” We delude ourselves if we think that science, philosophy, or any other method of inquiry can transport us beyond the essential indeterminacy that inhabits all perception of reality. And so it is even more apt that in Balzac’s The Unknown Masterpiece of 1832, the canvas upon which the fictional artist Frenhofer labors for years to produce the perfect image of a woman should appear to the characters Porbus and Poussin as a “chaos of colors, of tones, of uncertain shades, that sort of shapeless mist” (Balzac 1899: 42). Balzac’s tale is an allegorical reminder that our most exhaustive attempts to penetrate reality, whether through art, science, or philosophy, will always lead us eventually into this same ungraspable indeterminacy.

So finally, it seems there is no simple choice between homogenizing disciplines or retaining their distinctions; the commonalities are as fundamental as the differences. Rather than this being grounds for confusion or despair, though, I would suggest this is an optimistic sign of our maturing capacity for understanding at this time in human history. The fact that there is a growing appetite for interdisciplinary inquiry – albeit one that is not yet symmetrical between the areas – offers us the chance to affirm the plurality of our methods while at the same time fostering their underlying convergence, without one approach effacing another. Problems like the nature of consciousness or art are clearly too vast to be any longer the province of a single discipline; they can only be tackled through the subtle cooperation of all areas concerned, the precise terms of which we are perhaps yet to define. It’s timely to be reminded that, however diverse human knowledge may be, the unknown is the same for us all.

Bibliography

AACU (2002) Greater Expectations. Online. Available HTTP: <http://greaterexpectations.org/> (accessed 8 May 2009).

Balzac, H. (1899) The Unknown Masterpiece, London: Caxton Press.

Braque, G. (1971) Notebooks 1917–1947, New York: Dover Press.

Byatt, A. (2006) “Observe the neurones: between, above and below John Donne,” Times Literary Supplement (22 September).

Dorra, H. (1995) Symbolist Art Theories, California: University of California Press.

Frank, P. (1947) Einstein: his life and times, New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Hudson, M. (2008) “Rothko exhibition: art replaces religious faith,” Telegraph (26 September).

Huxley, T.H. (1887) Report in the London Times, 2 May 1887; cited in Nature, 36 (914): 13–16.

Johnson, G. (1996) The Merleau-Ponty Aesthetics Reader: philosophy and painting, Evanston: Northwestern University Press.

Journal of Consciousness Studies (1999) “Art and the brain,” 6(6–7).

——(2000) “Art and the brain, part II,” 7(8–9).

——(2004) “Art and the brain, part III,” 11(3–4).

——(2008) “Las Meninas and self-representation,” 15(9).

Kendall, R. (2001) Cézanne by Himself, London: Macdonald and Co.

Livingstone, M. (2002) Vision and Art: the biology of seeing, New York: Abrams.

Magee, B. (2001) The Story of Philosophy, London: Dorling Kindersley.

Martindale, C. (ed.) (2006) Evolutionary and Neurocognitive Approaches to Aesthetics, Creativity and the Arts, London: Baywood.

Onians, J. (2008) Neuroarthistory: from Aristotle and Pliny to Baxandall and Zeki, New Haven: Yale University Press.

Palmer, S. (1999) Vision Science: photons to phenomenology, Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Protter, E. (1997) Painters on Painting, New York: Dover Press.

Ruskin, J. (1872) The Eagle’s Nest: ten lectures on the relation of natural science to art, London: Smith, Elder and Co. and G. Allen.

Shklovsky, V. (1965) “Art as technique,” in L. Lemon and M. Reis (eds) Russian Formalist Criticism, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press.

Snow, C.P. (1993) The Two Cultures, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Solso, R. (2003) The Psychology of Art and the Evolution of the Conscious Brain, London: MIT Press.

Times Higher Education Supplement (2005) 16 September.

Ulrich’s Periodicals Directory (2009) Online. Available HTTP: <http://ulrichsweb.com/ulrichsweb/> (accessed 8 May 2009).

Warner, M. (2000) “The inner eye of two cultures,” Times Higher Education (17 March): 34.

Wilson, E.O. (1998) Consilience: the unity of knowledge, London: Little, Brown.

Zangemeister, W. and Stark, L. (2007) The Artistic Brain Beyond the Eye, London: AuthorHouse.

Zeki, S. (1999) Inner Vision: an exploration of art and the brain, Oxford: Oxford University Press.