A fine vocalist and equally proficient on both guitar and harmonica, Louis Myers was a triple threat. He was held in high esteem by his contemporaries and widely recognized as one of the top accompanists in Chicago. Born in Byhalia, Mississippi, on September 18, 1929, Louis and the rest of the Myers family relocated to Chicago in 1941, a move that was perfectly timed, coinciding as it did with the new emerging Chicago blues scene, one in which Louis was to eventually play a pivotal role.

Throughout his career he played and recorded with a multitude of artists, his reputation secured when he, along with his brother Dave Myers and drummer Fred Below, teamed up with harmonica player Little Walter, who was then at the pinnacle of his creativity. The band was the perfect foil for Walter’s innovative style. Rockers like “Off the Wall” and “Tell Me, Mama” to the haunting “Sad Hours” are considered classic Chicago blues.

Willie Dixon, working as a producer for the Abco label, was well aware of Louis Myers’s talent, having worked with him at Chess Records, and in 1956 Dixon had him record “Just Whaling” and “Bluesy,” a stunning pair of harmonica instrumentals that unfortunately failed to ignite the public interest. A fine session for One-Der-Ful in 1967 remained unissued until its eventual release on the Delmark compilation Sweet Home Chicago. Undeterred, Louis continued the life of a working bluesman, occasionally with others like Otis Rush, with whom he also recorded, or, occasionally, Muddy Waters, but more often leading his own band. In the late 1960s, along with his brother Dave and Fred Below, he reformed the Aces. In the early 1970s the Aces toured Europe on several occasions, recording an uneven album in France for Vogue. An album for Delmark with Myers accompanying Robert Jr. Lockwood fared much better and was followed by a tour of Japan with Lockwood in 1974, which resulted in the Advent album Blues Live in Japan. In 1976 BBC Television shot some excellent footage of the Aces at Eddie Shaw’s club in Chicago, which was subsequently shown in the documentary The Devil’s Music. But despite an impressive resume, personal recording opportunities were few. A couple more albums did see the light of day, but the success that should have been his continued to elude him. Louis Myers died in Chicago on September 5, 1994.

—Bill Greensmith

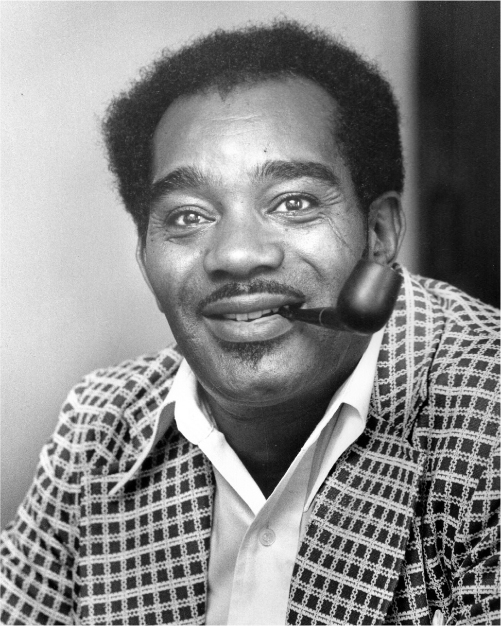

Louis Myers

Bill Greensmith

Blues Unlimited #122 (Nov./Dec. 1976)

You got to be saying something. You got to sound like Louis Myers before I can really feel that you can play a guitar.

—Bobby King

My father was like a sharecropper. He had land of his own, but it was run by his uncle. He’s still got it now, one hundred acres of land, and he was part owner. He inherited it. He’s dead now, he died in ’60. He played more classic blues than what’s going on today, what went on back in his time when I was a baby. He was playing classic guitar, but blues. He was playing around with some cats in Memphis, Tennessee. That was before my knowledge of him doing—I never did know none of the cats that he was playing with. I know my father play mostly for white people back down there. They come and get him and he go stay a week or two weeks sometimes before we see him again, he’d play for like their weddings. My mother played too, they’d play together sometimes. I used to sit on the porch and they’d be sitting up there playing. I imagine he taught her to play.

I can’t remember actually when I did start playing. Whenever I’d pick up one of the guitars around the house when I was little, they used to whup me, they used to tear me up. I couldn’t keep my hands off the guitar. I loved to look at the tuning pegs and the strings, it was something pretty for me. I used to mess with their guitars; they’d say, “Leave the guitar alone or I’m gonna tear your backside up.” That didn’t stop me. I had to have a hand on that guitar whenever I could see it. I kept that up and they whup me until they just gave up whuppin’ me. Then my father he just stopped playing around like he used to and started to working more at the house and farming. He borrowed his guitar off to someone and they kept his guitar. I know he let some guy have it. I can’t even remember the cat’s name. The cat took it off and kept it too long; when he brought it back it was kinda busted. I know him and my father had a little hassle, and he told my father that he had fell off a horse or something and busted the guitar. I know my father told him, “You got drunk and busted it!”

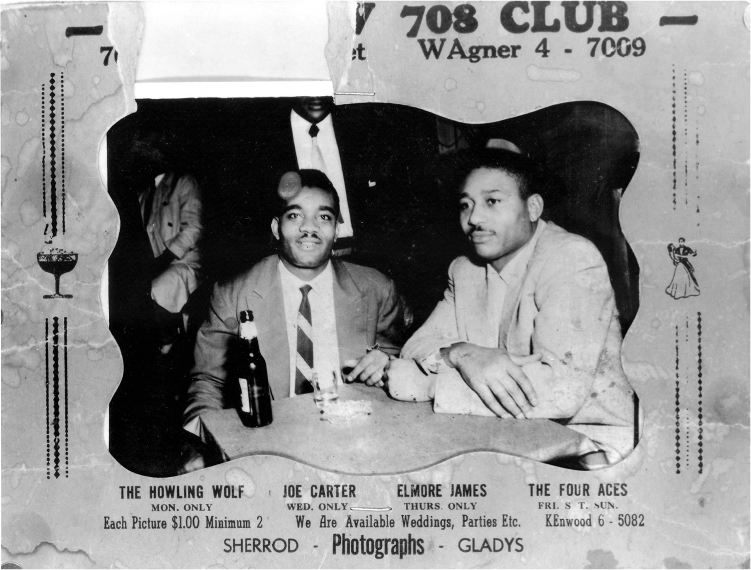

Louis and Bob Myers. 708 Club, Chicago, mid-1950s.

What really inspired me to play as I got up around nine and ten years old was a guy named Willie B. Sesserly and his brother Buncher. Willie B. was the youngest one. He is a good friend of mine right today. He come and hear me play right today. He inspired me to play, really. Because my mother and father they didn’t want none of us to play no music no way, but what’s in you gotta come out. So Willie B. was a guitar player. He was young, hanging around my father, and that old cat could play better. Willie B. was getting to be a terrible fine guitar player and singer. He could sing. Him and his brother Buncher—he was the one that was tough until Willie B. went away and stayed about a year, a couple of years, and he come back and he was really playing guitar then. He had a harmonica player with him and they both could play. He started to come by the house, he knew the family. We lived not far from one another. He left his guitar over the house because he know I liked to bang on it, and the next day he come back by there, I was so scared he was gonna take it away. He told me, “Say, you can keep the guitar, because I’m gonna be gone for two weeks.” And when he got back I think there was only two strings on the guitar. I had done bust them all. But I had learnt how to play something, though, because when he come back he wasn’t mad because I broke the strings. He said the strings were old on there anyway. But anyway, he put some strings on the guitar and listened at me bang on it. He said, “You know, you learnt what you learnt on your own, that’s good.” He tried to show me how to play, and from then on I got very interested in guitar. But, like I said, my father didn’t want me to be a musician, and I imagine that’s why he whipped me all the time when I touched the guitar. He knew it was in me, but he wanted to stop it right there. He really didn’t want me to play the guitar.

Them two brothers, Willie B. and Buncher, they play together, man, they were rough. They played at house frolics. When we were little kids we’d go to other neighbors’ houses, might be two miles across the country, you know, like our neighbors and friends, and we’d go around there when we know they gonna have a frolic. Everybody wants to know who’s playing there, they say, “Willie B. and Buncher.” Well, they were top at that time, they could play, man. You could hear them guitars a country mile, too. Yeah, down there you could. They had them round old guitars, man, they sound so loud and clear. And that’s why I started playing. Every so often I learnt a little bit more. I watched Buncher and Willie B. how they played, and just seeing them I know I had to find what they were doing.

My cousin on my father’s side, he was a musician. My father’s brother—he played guitar, too. His name was Fred Myers, but he died. I guess I was about seven years old. Yeah, they all was musicians on my father’s side. I don’t know of no musicians on my mother’s side.

My brother Bob has been playing for years. See, I always had something to lean on. He used to fool around with the harmonica down there at that time when I was a little boy. He was fooling around with the older boys, everybody down there was playing the harmonica whenever they could get one. And he really could play harmonica. He learnt to play with different names—the cat I done forgotten, but they were very good harmonica players. They hang around, like Sonny Boy and Little Walter, they were tough, but they never did get no … Bob was playing harp before he left Mississippi and I was, too. Whenever I could get me a harp, I play that.

Some harp player that we know, he was named Wilhelm. I never will forget him, they call him Wilhelm. He was kind of a shy harp player. He was much older than we was, he was upper teenager cat. I guess he was around about eighteen years old then. I was about seven or eight then. And I know my older brother and Wilhelm they’d be playing all the time, and I used to listen to him, but he was shy. Dark tall cat, he was real shy. Just them two get together you can hear them really playing. Whatever instrument I could get my hands on, if music come out, I was interested in it.

We used to take nails—now, you listen to this. Believe this or not, but this is what we used to do. We used to go out and find cane, tall cane. We call them cane down South, but they call them bamboo poles what they use now, same thing like you use for fishing. Some of them you’d get real large and long joints on them; we cut the joints out of them with the ends of it right on the joint. We’d make a fire and put the nails in the fire and let them get red-hot, and we’d take that and burn holes through them, much as six holes, and we’d make a fife out of it. And sometimes we’d get sounds out of them too, man. They might not be in tune, but we got something out of them! We made whistles out of little small canes. We made all kind of whistles and flutes, anything that made a tune. Yeah, I just loved that music all the time. I still do right now, really. But it’s a lot done changed since then.

I moved to Chicago when I was eleven years old, the beginning of 1941. I guess we got here around late January. Things started changing, because the war had just got on. I remember real well things were changing, most people leaving farms going into the service. The whole thing, the whole scene back there then was farmers wanting to do a little better. So I guess my father thought that we better move on to Chicago, because my mother had three sisters living in Chicago then.

Coming to the city is really different. You got to get to know the way the city is. I mean, when you come from the country you don’t see all the lights, sidewalks, and buildings and things. Yeah, it was really different, but I got to meet musicians. I mean not meet ’em, but just see ’em. They were old musicians, they were old to my time then. But I imagine they wasn’t all that old, it was just the time I met ’em, being a boy around eleven years old.

We were living at 3948 Indiana and the first guy playing guitar that I really learnt about was Lonnie Johnson. He was living at 3946½ Indiana in the basement. Yeah, he’s sitting on one basement level down there playing on his guitar, and, being the nosey kid that I was, anybody with a guitar, I’m peepin’, you know. So I was on the back porch, which I was up on the second floor, and I happen to look down there and I asked my auntie who’s that man. She said, “That’s Lonnie Johnson, that blues-playing Lonnie Johnson cat.” Well, you know, my auntie was a religious woman—church—she didn’t believe in no blues, and that’s what had me kinda scared of playing then. My father brought an old guitar with him, wasn’t no strings on it, but I was gonna put some strings on it and try to play with him. But Lonnie Johnson seem to be a kinda mean man. I know he told me to get away from around there one time. I never did, what you call, get to meet him or shake his hand or “my name is Myers …” It’s just what you call a next-door-neighbor thing. But I saw him there for about two or three years; all I see him do was go out and in. Some hot days he’d be sitting out on the back in that little basement porch. Sometimes, not often, but every once in a while you might see him out there with his guitar playing. But he was a self-man, a do-it-his-self-man. He didn’t play with nobody.

My father was working at some factory. He gave up playing when he left down South, because, like I said, he quit going out, he just did work on the farm and that’s all. His guitar laid around till it got busted, tore all up. Then I had to get me a guitar of my own. I think I paid $12 for a little bitty small round old guitar and I kept that for years. I guess I bought that guitar when I was around twelve years old and kept it till I was about seventeen. It was completely demolished itself then, it wasn’t no use trying to play it.

I also saw Homesick James. He wasn’t going under the name Homesick James then. I don’t know what name he was going under, but I know he called himself James. James Williamson? It might have been. Well, I know when I met him I heard Othum, him and Othum Brown. My older brother, Bob, it didn’t take him long, ’cause he played harp, and every guitar player wants to see a harp player that could blow any harp. He got around and he knew them. Well, he was playing harp and he always would tell me about a guy named Othum Brown that really play guitar. And I told him I’d be very interested in meeting him. He said, yeah, he want me to meet him, too. But I was a kid—you don’t get out to these places, whiskey joints. So one day, one evening I met him and Othum Brown on the street and Homesick James. They both was playing and I got to know Othum, because Othum could really, really play. He was playing on the sidewalk on the street with a cigar box, him and James, and people was gathered around them throwing quarters, nickels, and dimes in the cigar box and they were playing. This was right around where I lived at 39th and Indiana. They were hanging around 39th all the way back down to 31st. They was playing at all these places at night, but whenever they want some money to get them a drink, man, they play right there on the street and get that money. You see them walk off, they got enough money to get them a drink. Othum was pickin’ some guitar, mister. I ain’t never seen no cat that could pick as much guitar as he was pickin’ by himself. He didn’t need nobody to play with him, even though Homesick James was playing. They both play, but that Othum could play, now, he could play.

I met Othum Brown back there then, but I never did hang around on Maxwell Street. I never did go down there. I mean those cats had been makin’ their little money and things down there for years, you know, but you take the cats around my age bracket, they didn’t hang around down there too much. Take, like, Earl Hooker. Now, how I met Earl Hooker, it was like in a little gang fight. We was kids going back and forward to the show, catching the streetcar, jump on the back end of it and ride down to where you going. And I know Hooker, he was running around with a little street gang then and I never did know he played guitar. They jumped us one time on 35th Street, and the next time I saw Hooker he was on the street playing guitar. And, now, he could play, he was around my age bracket. Man, he could play. When I saw him that kinda made me wanna come on out and play on the street, too, but I never did, because, see, I was always shut in by my peoples or the religion on my auntie’s side. Like, we was living in with her and she didn’t like blues. This was when I was about fourteen—like, I really wanted to play.

You see, in my neighborhood then, the only cats you could see were the older cats, and they could do what they wanna do. But there I was, a young boy from Mississippi, and all the kids wasn’t going for the blues back there then. They was going for swing and stuff like that, and the people didn’t like the blues—kinda like the older set. Kids around my age bracket didn’t go for that. I used to sit on the porch and play, and the kids used to laugh at me ’cause I was playing the blues, so I quit playing for about four years then. Wasn’t no use, my auntie didn’t allow me to play and nobody allowed me to play in the house. So I quit and I picked it back up, especially when I saw Earl Hooker. He was playing with another kid named Vincent.1 He come back to Chicago last year. Now, he can play, too. I don’t know his last name, never did. Now he plays jazz. He’s one of the best guitar players in Chicago, but don’t nobody know it, because he’s just come back from Oklahoma in the last year or so, but he used to play around with Hooker on the streets then. Hooker was a terrible young guitar player.

Earl learnt from different cats, you know, same way as myself. Nobody learns to play what they can play by themselves, because it ain’t to be done. Only cats that can do that can sit down and write and let other people read it, and then they can play it and then they know this cat invented it. But blues players—they play by feelin’. Like, I hear something Lonnie Johnson did on records, I loved that man. I said I ain’t never heard anybody play like this. Lonnie Johnson was in his own bag. A person learns to play from feelin’. The way I gotta hear is how much I can hear and how much it sound to me and how much I can feel it. If it don’t stay with me, that’s something I’m not gonna learn. But if something stay with me, I can hear somebody do something maybe five months previous to the time I’m gonna do it, eventually I’m gonna do it.

Professional, well, we just eased up into that. Because I had been playing, I started playing for house parties, that’s where I met Robert Jr. Lockwood. Some old wineheads come over and got me to play at their house party. That was terrible, terrible. I don’t want to tell nobody about that. That was terrible, man. There I was eighteen years old and I went to this wine-head’s building on 39th and State. There was some cats that live in there that heard me play and liked me. They liked the way I was playing for a kid. And he taken me up there and told me he was gonna get some money for me playing, so I go on up there with my guitar. There I am sitting up there playing, and Robert Jr. was there playing when I got there. He play awhile and I play awhile, then we play together. Well, anyway, a wife and a husband got into a disagreement. They come up with big knifes. There I was, you know, I ain’t never been through a thing like this. So I got up to get out of there, because when I saw them knives and they were swinging at one another. When I got up and tried to get out of there that’s when the woman come grab me. She grab me from behind with the knife, swinging out from behind me at her husband. Her husband in the meantime is swinging at her over me and there I was. Robert Jr. and this other guy that got me there to play told them, “Y’all shouldn’t do that, that ain’t nothin’ but a kid. Y’all turn the kid loose.” They were using me for a shield. Every time he cut at her she would push me out there to him, until they told them to stop that, so I got away. That’s how I met Robert Jr. I don’t know if he’s done forgotten, that’s been a long time ago. The Pomerange Building, Willie Dixon was living in there, too. This was around about ’46, ’47, something like that. I think ’46. I didn’t do no more parties by myself. No. I didn’t know nothing about what them people were doing, ’cause I was just as scared as I ever been—them knives, man. Two blades, one coming at you and one coming out from behind you, and I didn’t know what to do. I went home and didn’t come out the place for nobody.

Amos Milburn sent for me to play guitar in his band. Said they was gonna tutor me into music. I probably would have been a better-off guitar player now had I went with him, but my mother wouldn’t about let me go. That was about 1946, something like that. He sent a man first, then he sent a letter. What you’d call a talent scout looking for good young guitar players, and at that time my mother wouldn’t let me go. I never will forget that, you know, things like that. You know, the man come there and said, “We’ll tutor the boy to become a good musician.” Some older musician turned him on, a piano player. I can’t think of his name now, but he was living right around the corner from where we were living then. Amos Milburn was makin’ records and traveling on the road. I can’t think of this piano player’s name. He played downtown all the time. He start me tuning up with the piano, 4/40, which I didn’t know nothing about, and I learnt how to tune the guitar up to 4/40. He heard me play and he told his friend what a tremendous guitar player I was for such a young boy, and I think he about turned them cats on to me, because he knew all about Amos Milburn and all them cats making records. I was about sixteen.

A man named Mr. Spires, he kept hanging around, like he was interested in me. Arthur Spires. I think Mr. Spires about sixty-five years old now. He got interested in me because, like, I started playing house parties with him, me and Mr. Spires played around a good little while. He recorded for Leonard Chess, “Big Fat Mama.”2 He used to come by and get me all the time. Mr. Spires wasn’t what you would call an out-and-out guitar player. He couldn’t hold his own, but he could sing real good. But he was trying to learn to play guitar when he got his guitar. But when he heard me play, well, he knew that he could learn with me, because at that time, man, I could really play pretty well. Because anything I hear I could play. I’ll find it. A lot goes into playing blues guitar. We play around I guess three or four years. Me and Mr. Spires had it like an incorporated band, me and him. Like he would get the little jobs and things and I would do the playing. Just me and him.

My brother Dave was learning how to play, but he was learning how to play much faster than Mr. Spires, like things that Mr. Spires couldn’t learn. Dave would spend a lot of time with me. He’d come around when he’d get off his job, but Mr. Spires, you’d see him maybe two or three times a week. I was playing way before David even picked up a guitar. I didn’t even know that he was interested in guitar till he used to say, “I’m gonna go and buy me a guitar.” I told him, “If you do, let’s get together.” So he went and bought him a good guitar, a Gibson. He started learning with me. That didn’t stop Mr. Spires. He come and get me and David.

I used to go to the show and Mr. Spires come looking for me one night. He had a party on a Friday night and I went to the show. And incidentally, he had Dave in the car with him. I came home about 10:30 that night and there they sat waiting for me. They were so mad. (laughs) Mr. Spires said, “You sure messed up a good night. I had all them girls and things up there, where was you? Me and Dave went there and did the best we could do but …” I used to love to go to the show, man. I’d go see me a Western or something like that. You know, my mother would tell me, “Mr. Spires been by here looking for you …”

Well, I met Junior Wells. Some of his cousins heard us playing in a building across the street from where he lived. We was playing at some of his relations’ house. They was grown girls, they said, “We got a cousin that can play harp pretty good.” He was younger than I was. Junior could play. He wasn’t playing professionally, but he was playing what he was playing. As you go into music and be more together with one another you come off better. When you’re young and got it in you, it’ll come out of you. Junior learned how to play pretty well and we started playing together. That time David started pickin’ up on guitar better than Mr. Spires was, so when we did get a professional gig, we went on and took the gig, and that’s where we cut Mr. Spires out. That was me, Junior, and Dave. We didn’t have a drummer for about three or four years.

The people started accepting us because we were playing much faster. Our music was mostly up-tempo, and they hear us play and they call us the Little Chicago Devils and wasn’t but us three. We were the Three Dukes for a good while. Then we turned ourselves into the Three Aces, then we went to some other name.

Elgin Edmonds, he also took up with me, he liked me. Him and his wife used to take me out fishing, go fishing all the time, because I love to fish, too. He told me one time, “Y’all gonna need a drummer with y’all.” Like, we’d sit in with them (Muddy Waters) and Elgin would tell us how we sound with a drummer, but we’d sit up there and pat our feet so heavy till we didn’t need no drummer. We had been used to playing by ourselves. We stomp, you know, for the beat. He said, “The way y’all play, y’all don’t need no drummer, but y’all do need a drummer so you won’t have to be stompin’ your feet. I know a boy just out the army. He’d be a good drummer for y’all.” And that was Below.

I said, “Well, if you see Below you be sure to tell him.” So we got the gig at the Brookmont and he sent Below. Below didn’t have a whole set of drums. Elgin let him have the drums, too. So Below come with us, he tried to play with us, but he couldn’t. He said, “I can’t play with y’all, tonight is my last night.” I said, “Man, it’s funny you can’t learn to play blues, and you say you can play jazz and all be-bop and stuff, it’s mighty funny you can’t play blues. I can play jazz and you can’t even play blues, you know there’s something wrong about that.” So Below said, “Well, I’ll tell you what. I’m gonna try it another two weeks. You talkin’ about I can’t play no blues and you can play jazz. I’m gonna learn to play the blues.” I said, “Well, okay, then.” But he had quit. He said he ain’t never heard nothing sound like that before. He said, “Man, I can’t play that.” I could play some jazz by listening, by ear, but that wasn’t what I was getting over on. I was freakin’ out playing blues.

Shoot. Man, it didn’t take Below two weeks to learn, but, see, he had to get in there and create his own beat. You have lots of people who said where I taught Below to play. No, I just showed him the way that a blues had to have a foundation beat to it. He wore out my guitar case. I had an old guitar case; he just beat that till it fell apart and I couldn’t put my guitar in it no more. He used my guitar case for a drum, sit there beating it with his hands right there where I was living at. But he invented his beat to go along with the blues; don’t nobody learn nobody nothing. A person learns how to get into something, whatever he can fit into his own bag. I tell him all the time, I say, “Below, I read some article where they say Louis Myers taught you how to play the blues. I ain’t taught you how to play the blues. I showed you a way to a beat where you had to find a beat so you could play with us, and you had to do that yourself.” He said, “Yeah, that’s right.” I said, “Well, I don’t like to see it, because people get the wrong impression. How can I teach you to play blues on a drum?”

We went around and sat in with Muddy Waters when Walter was playing with him, and Walter was planning this thing after his record had come out.3 He always wanted to play with us, because we was playing faster music; our music was faster than Muddy’s and the people’s liked to dance with a little speed, jump, or something. And we sat in with Muddy Waters and right away Walter heard us play, man. He said, “God-dog.” Walter and Muddy was playing way over there and we went over there on the West Side. That’s the first time Walter ever heard us play, and he was completely out of his mind when he heard us play. He was determined to get on the bandstand and play with me, Dave, and Below, see, because Below was a monster drummer. It didn’t take Below three months to be a monster drummer in Chicago. Walter heard us play and there was something about us that Walter want to do. See, Junior was playing the harp and we was getting down. He said, “Y’all play fast music.” And he got in there and sat in with us one time, boy, and I heard it myself. He said, “Louis, you guys are really playing.” But when he left Muddy and come to us, he had his way of playing. You see, Walter had tutored himself in this style of what we was doing and he knew he could play right … The kinda stuff that we was playing he was very interested in. I’d be the same way if I heard some dudes out there playing and they sounding and I knew I could fit in. Them the kind of cats I want to play with, somebody that I could learn to play with and learn to fit in with. Nobody don’t want to play with nobody they can’t play with.

I hired Walter after Junior left and went with Muddy. We cut “Lawdy Lawdy” after Junior done gone with Muddy.4 Walter called me up and told me that Junior was gonna split. Walter had been back in Chicago for two weeks. They had been gone on the road, everybody know that they out of town. But when I found out Walter was back here in Chicago, because he called me up and said, “You know your boy done split on you,” talking about Junior gonna leave the band, Junior hadn’t told me nothing about it. See, back there then the union was very strict, the black local. When one cat gonna leave out the band, gonna quit or something, give the proper notice, just like you do the proprietor who own the joint and the man also give you that if he wants to fire you. So Junior hadn’t said nothing to me, which he was gonna leave the next two or three days. I asked him, I said, “Junior, when is you leavin’ to join Muddy?” That was a surprise to him to know that I knew. He said, “Well, I’m supposed to leave Friday.” I said, “Well, okay, then, I just want to know so I can get myself a harp player, because you should have told me.” He said, “Well, I didn’t know if I want to go with Muddy or not.” I said, “Well, that’s your business, but I never would have known until you done gone.”

Walter had done made “Juke,” and the way he was telling me, I think that’s why he left Muddy, because he was getting so many requests for “Juke” and he wanted to be on his own. But that wasn’t the reason I hired him. I hired Walter because we needed a harp player, and Walter made sure he’d be the first one to know, because otherwise he wouldn’t have called me up and told me Junior was leaving. When he did I told him I’m gonna need a harp player with Junior gone and I ain’t got no time to find one, because Forrest City Joe was around and we couldn’t find him, and he could really play. Oh, man, Forrest City Joe was rough! He’s the baddest harp player I ever saw. Yeah, ain’t nobody as bad as Forrest City Joe. Better than Walter? Oh, yeah, man, yeah. I ain’t puttin’ none of ’em down, but the fact remains anybody who heard Forrest City Joe knows that he’s the baddest harp player that ever lived. He could take them chromatics and play anything that them jazz cats play. He’d take that little harp and you wouldn’t believe the things he could play on it.

He’d play the “Tommy Dorsey Boogie” just like that record go with one of them little harps. Nobody could see how he’d do it but him. But he was a wino; he’d play with you a couple of nights, get that money, you wouldn’t see him in a month of Sundays. Like I said, I ain’t never heard nobody play as much harp as he, no kind of way. That cat could play, never heard nobody play the harp he play. Even when I hired Walter, Walter had to leave for two weeks. He had a show with an all-girl band somewhere traveling across the country. Yeah, he was booked with an all-girl band on a show. He didn’t dig that, because he told me when he come back. But we hired Forrest City Joe to play, and he played about two or three days and we didn’t see Forrest City Joe no more. But, man, Forrest City Joe was the kind of cat like this: when Walter was playing with us and Forrest City Joe did show back up there, Walter wouldn’t let him come near the bandstand. No, sir. I never heard nobody play as much harp as he did.

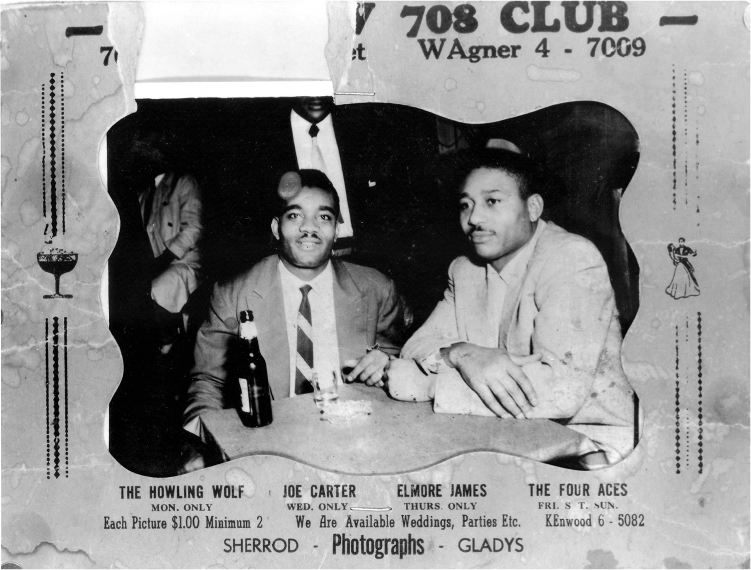

Little Walter and Louis Myers. Apollo Theater, New York, 1952.

Bob (Myers) could really play, man. You wouldn’t believe, but he could play just as good as Sonny Boy. But he didn’t have the name. Sonny Boy was already out there playing when we were little bitty kids, but they were friends and he started playing around with him. I never did see Sonny Boy, never did see him. My brother used to try and show him to me, but you don’t pay things like that no attention. He was playing over there the same place where we got the gig at when I hired Little Walter, the Hollywood. Sonny Boy came down there one evening. My brother tried to tell me, “Why don’t you come on down so you can see and hear Sonny Boy?” They was crazy about Sonny Boy then. To me, I didn’t think of cats like that, because my thing was playing guitar. I didn’t care too much about no harp. But when I did hear his records, I heard what he was saying. That was good enough for me. What he would sing he would play at. And a lot of cats would never be able to duplicate Sonny Boy, not even Forrest City Joe. He’d come very close to the same thing, but not Sonny Boy.

That old Forrest City Joe, he a bad dude on harp, man. He could really play harp. He played piano, too. He was as rough on piano as he was on that harp. Forrest City Joe was a cat like this. He can hear what a cat’s saying and duplicate that there. Most of the things I’ve heard on record he sounds more like Sonny Boy. But if you get down to actual playing, man, if he’d just cut his fooling around and go on and play, like, do his thing, you’d say, now, there’s Little Walter sounding like Forrest City Joe. It’s just that simple. He’d turn it right back around. You see, if he’d hear somebody do something, it goes in that ear and he’d sound like that, almost. The only difference was that Sonny Boy sing as much as he played. Now, believe me, this cat was a great singer, this Sonny Boy, John Lee Williamson. Yeah, he played them songs, man. He sang ’em and played ’em. You listen at his harp, it’ll be saying just what he be saying in the words. But Forrest City Joe, man, come down to harp playing, no kind of way them cats would touch him playing harp.

Little Walter had enough authority playing his instrument to fit in with any band that is playing time, and he could play so strong until he’d dominate. If the band’s listening to what he’s doing, naturally they gonna make him sound good. We were all playing in the same environment, man, our intentions were the same. If you listen at my guitar playing, man, distinctive sounds and the attitude was there. The little notes that I was pickin’—it’s trying to say it’s tone. I’m playing tone, and this is what makes the whole world go around in music is tone. He played all different amplifiers. He had a Gibson amplifier and a PA system, two speakers, things like that, whatever he could get his sound over with. Like, to me, Walter studied a way to get himself in on the harp.

But before I knew of Muddy Waters and Little Walter and all them cats, I had heard guys sitting on the corner playing harp out of amplifiers, man. A whole lot of cats playing by themselves, no guitar, now. That was back in ’43 and ’44. And I think that was before some of them big stars come to Chicago, don’t you think? Like I said, I have heard that stuff on the corners, cats with amplifiers. Some of them had little bitty old small amplifiers making that noise out of them with the harp. I know because I used to try and play harp myself, but I wouldn’t do it. I used to hear my brother stand on the corner and play harp.

I cut records with Junior Wells before Walter. I know I made “Hoodoo Man” with Junior Wells. “Mean Old World” and “Sad Hours” was the first record I made with Walter.5 We had been playing “Sad Hours” down there where we was playing. Junior was with us, we used to play that by ourselves. Junior never tried to play harp on that, though. That was just a number that we liked to play for one particular man, the proprietor, Charles Hallaburg, that was at the Hollywood Rendezvous. He and his wife owned the place then, and this is what he wanted me to play every night. It’s something like a—what’s that thing’s name? (hums “Blues after Hours”) Yeah, I guess they call that “Blues after Hours.” Every night we had to play that two or three times. When Walter come in, like when I got him with the group after Junior cut out, he come right on it, that’s something that he could play on the harp, he could fit the harp in with it. See, ’cause Walter wasn’t no slouch on the harp. He could handle the harp, but he didn’t go doing anything too obnoxious. He just play what he could handle, like tone. That’s all there is about playing harp is tone.

Now, here’s a thing that arise at the wrong time. Now, you understand what I’m saying? On the gig we would do it, but when we got down there, when we recorded, Walter wouldn’t do it. Dave started playing it and (Leonard) Chess liked it. Chess said, “Hey, y’all play that again, man, do that again.” Walter chickened out. Said, “No, no, that’s alright.” And Chess wants to know why. Now, this makes Chess more interested in it. So anyway, they went on and him and Walter got into a big thing about it. He said, “Man, what you don’t want to play a number like that for? That sounds good.” Well, Walter had done said, “Well, look, that’s one of the men’s ideas, I don’t want …” Now, that’s honest as a man could be. I told David myself, I said, “Man, you should keep your ideas.” Just the same thing Walter told him. He said, “I’ve got my numbers, I’m already made, whatever you got keep it to yourself.” Chess wanted it and it wasn’t Walter’s idea, and Walter knew that just like I did. We all knew that. But Chess wanted it. It’s a business thing with Chess, which is no more than right. He wanted it because he see that he liked it, somebody else would like it and he could sell many records on it. But that means somebody gonna lose in the deal. So Chess got around there and he talked to Walter, begged Walter, and Walter told him no. But some kinda way Chess convinced David that he’ll get the credit for it. But he never did.

Now, you see, Walter didn’t want to accept anybody’s idea. But he had to play on this when he knows that he could fit in real good. He wasn’t gonna just play it out there and let nobody else have it. He wasn’t gonna just play on there and do all his thing on there and then say, “Give it to so-and-so.” Then, if you look at it you could say this: had Walter had’ve give it to David, David couldn’t play it, because he couldn’t play the harmonica part. Chess said, “You’re not gonna get by with this number, this number’s gonna be played.” And in business I would have did the same thing. I don’t give a hell who it come from, that’s what I want. If I want it, I’m gonna pay for it. I’m gonna get it. That’s all there was to it. He just said, “I want that number.” And he also told Walter, “You gonna play it, too.” And Walter played it.

We never did rehearse. We walked in the studio because we were playing with one another, I know what he’s gonna do. See, I’d deal with Walter on his level, what he’s capable of playing. If he can play 2, I can play 2/2. You see, because a harp is limited, man. He can’t do nothing on a harp that can get away from a guitar player if he can play more than three or four changes. Chess would call you down if things ain’t right out there, and they got to be damn near right. Chess was a very funny kind of cat, man. But I’ll tell you, when it gets down to that music and that ear, ain’t no way you could fool him, and his brother, Phil, was the same. Both of them were what you call good. They had that ear on them, they could hear the blues and stuff like that. They know when it’s supposed to be right, and when it ain’t right they’d let you cool, try and keep you calm till you come back normally to your thing. He knew what the people wanted and he wanted to sell what the people buying.

It’s what a person is producing when he’s sounding, whatever number he’s doing. Chess had an ear for that, he could detect whether you gonna come through or not, or he’s gonna make you come through. I think the sound was something else different, because I know Walter sound good in one studio, and some studios, man, you just couldn’t get no sound. I didn’t cut that much with Walter. I don’t want you to get the wrong impression that I cut a lot with him. I didn’t. David cut with him for years after.

We toured for years all over the United States playing auditoriums, dance halls, roadhouses, nightclubs. Here we were with amplified music with a different thing altogether. Where I had fun at, after I realized what we were really doing, that the other cats didn’t have a chance, some of them bands didn’t have a chance. We was playing out of big amplifiers, and they’re sitting there playing horns and things with one or two mikes. A ten-, twelve-, or fifteen-piece band, but the peoples had to get up close to hear that. In the meantime, we had big amplifiers, man, and Walter could take one of the things that he was playing out of and sit it way out there, hang it up on the wall somewhere out there. He was using—I think they call them “Macon” PA system, and those things were heavy, man. Do you realize how strong an amplifier is just blowing an instrument out of it? Can you imagine an upright bass gonna sound as loud as an electric bass? You can throw that big upright bass among an electric bass with all them amplifiers, you won’t even hear him. You won’t even think he’s there. In fact, good musicians used to tell me, you’re not supposed to hear too much of a bass, you’re supposed to feel it. Now, you imagine, we got all amplifiers and here’s these cats still playing the old style, just sitting up there playing drive-along-jimmy, no amplifiers. I realized this at the time. Walter, David, Below, and myself, we all knew this. But, now, those cats didn’t know, they didn’t know until we was up on them. Like we done played and they say, “Man, those cats choppin’ us up.” We ran into quite a few bands out there with names that didn’t have a chance. If they played their set before we played, just call themselves lucky. Because that next set they go back on, them peoples just boo them off the bandstand, wouldn’t let them play no more.

I heard a piano player crying one night because he goes to play the piano and there all the notes out of the piano. Piano’s done tore up and he’s got to play this piano through the night. He’s just one, but think about all the rest of them that’s been in that same shape. They relying upon the piano for the big chords and things, and they get there and the piano player can’t play, because twelve or fourteen of the notes is gone. So they’re cooked before they start, right? Anything we play is gonna be heard whether it’s right or wrong. How could a small four-piece group do any harm to a big band? All they had to do was look at what we had and look at what they didn’t have. We had amplified music. The horn player would stand up there, pull his horn out of its case. We’d always run across some cat that could blow, had volume, that could really get up there, but he was just one in the band. They all got to be choppin’ to fool around with us. We would chop them bands. Walter was playing like forty horns, man. His amplifier would sound like that sometimes, put his echo on and God! Music was hittin’ the walls and bouncing back to us, bouncing all over the place, and they’d say, “Them cats sound like a giant band and there ain’t but four of them.” Like, I heard some horn players talking: ‘Man, that Little Walter or whatever his name is, he really got a thing going on. Look at the cat, he’s got all that volume and them boys, them cats that’s playing with him are just something on them guitars and that drummer is outta sight and they got their stuff together.”

It was an altogether new different type of stuff that the people was accepting, because we was whippin’ it on ’em strong and sure. We was killin’ ’em, man. One time I read in a paper that Little Walter was the baddest band in the land and it wasn’t but us four. But we had something new and something different. And had we been men among ourselves, we’d been strong right today, still been in a new bag with all the youngsters coming on. We’d still be playing something that the people would be enjoying from now on, but whatever we brought here we wasn’t men enough to handle, we wasn’t men with ourselves. Everybody had a greedy bag they want to get in. Well, I had to live through that. I never knew what greediness was, I always loved to hear cats play.

But we was playing and getting ourselves together in blues. There’s so much stuff we played that didn’t get on wax, that is the killing part. Had people had tape recorders back then like today and heard some of the things. Like, say, for instance, you heard Walter on the record. He went there for that one purpose, that was to put something good on record. That wasn’t all we played. Like today you got tape recorders, you can follow the performer around and listen to him, listen to what he’s got to offer. We played so much stuff, man. When we play our best, like, we beam to ourselves. That’s one thing, the greatest stars is facing that one thing, they can’t outplay themselves. They mostly do their best with themselves.

I know one Sunday we went up there, 609 West on 47th Street, and Muddy Waters was playing there. It was in the daytime. I met up on Walter someplace and we went over there. Well, Sonny Boy (Rice Miller) was playing there, too. Well, Walter and Sonny Boy, to me they was funny. Like, they never got along, but I imagine they got along, but both of them play harp. Sonny Boy was much older than both of us, and Walter used to wave his hand at him when he see him, and Sonny Boy used to look at Walter real funny, really look at Walter. Well, anyway, Walter said, “Hey, let’s go up there and light him up.” I said, “Oh, man, I don’t feel like foolin’ with that old man. You gonna go up and get that old man stirred up. He’s gonna blow you right on outta here.” Walter said, “Let’s go up there and get him.” Well, I tell you. Sonny Boy played the way he played—his own trip, the same as Walter did—but, now, to me you couldn’t put them both together saying Sonny Boy could overdo Walter with the harp, tricks, and things. Yeah, but, man, Walter could lay down a tone on that harp, he knew that. He whupped that tone on any of them, boy, and didn’t even care. He got on up there and stirred Sonny Boy up, and, like I said, Sonny Boy blow Walter right on out, tricked him out is what I mean. He took two or three harps and went through his bag and took the great big harp. He could really put on a show. Well, Walter wasn’t that much of a show, but Walter could blow. That’s something that he just wanted to do, just tee off with old Sonny Boy to get him—make him go do all them things. But, man, you get on down to nitty-gritty playing, you don’t fool around with Walter, because he lay that tone on you. He’d lay back there, you’d see him battin’ them eyes, lookin’ around at you out the corner of his eye, you might as well turn him a-loose. There ain’t nothin’ you can do with him ’cause he’s gonna be playing tone and come out with some things that make you believe he’s sounding a music score. When you hear him you’d say, “How’s he do all that on the harp?” I know I heard something, he ain’t had no business … I heard a way-out horn player saying, “Man, if that cat pick up a horn and get that sound he’s getting out of that harp, I’d take my hammer and catch him and do something to him, break every one of his fingers so he …” (laughs) If you listen at that harp it don’t even sound like a harp no more.

We did a gig at the Apollo and they had one of them high-up stages in the back for the drummer, and Below went to hit the drums and the leg slipped off and Below fell. Well, you know, it was a funny thing; the peoples thought that it was in the show, but it wasn’t. He went to hit his cymbal way over there and the leg slipped and Below went boom! And the people gave him applause. We laughed about that while we were traveling on the road. Walter said right there, “That Professor got a-loose back there.” We called Below “Professor.” Walter called him ’Fess. The reason we called him that was because Below was what you’d call more educated than what we were, and he would explain. Back there then he would use his education when it’s time to use it. Like when you don’t have the appropriate education on some things that’s said, Below was always there. He would always speak, put it right. We all named him “Professor.”

But we named Little Walter “Little Goola,” because he act like a kid. He was a nice cat, but I guess when I left him and the band left him and he got different other cats playing with him, he just changed. This is what I say about blues. It will still change a cat, because he’s existing off of that. You see, when a cat’s existing off music and he goes and plays with somebody else, he’s got to dig his whole personality in order to say what he’s got to say, and that’s a hard thing to do. Even Walter told me that himself before he died. He said, “Had I been with y’all and treated you guys like men, paid you right, and done the right things, I’d be top man today.”

Walter was a nice cat. We was all young and he had a better understanding with us than Junior. See, Junior, to me, didn’t have any understanding. But when I hired Walter with us, naturally Walter took over the band, because he had a hot record out on the streets, but we didn’t have to change our name. But Walter had so much influence that Dave and Below went on with him in spite of me. The majority won, so I was gone right after he come back talkin’ that stuff. So that’s why I left him. See, a lot of people don’t know why I left him. See, I believed in the right thing. Now, they stayed on with him. Before we left town, going out on an engagement, he used to change the name to the Jukes or Night Caps, things like that, and we already were the Aces. I told the man we should remain the Aces and let it be “Little Walter featuring the Aces” or “The Aces featuring Little Walter” so we wouldn’t get lost out here. And they stayed on with Walter and one by one they left Walter. I was with Walter quite two years. Before we hit the road, we had an understanding, but Dave and Below, they left me. I was just one, so the majority won.

We was in the car talking and Walter wasn’t saying nothing, because he’d got them together on me. What could I do? But I told them we should keep our name the same and let Little Walter be … I said, “You already a star, Walter, you should let us remain the Aces.” But he couldn’t hear that, and Dave and Below agreed with him, so that was the end of that. I was what you’d call one foot in the door and one foot out anyway, because I don’t want to play with anybody that don’t want that understanding. Because Walter was a greedy man. He want it all for himself and, like I said, he didn’t want to pay right. When a person’s that greedy, he ain’t got time to do nothing right. And that’s the onliest fault I found in him, and that was a big enough fault for me to leave. He didn’t want to pay us nothing. I got on to him time after time. I said, “I’m not trying to get into your business or nothing like that, but why should one cat be professional out here? I know one name and you know I know it and you know it. One cat ain’t nothing without the other one.” “Yeah, but I got a name, I’m Little Walter.” I said, “Yeah, that’s true, but, you see, we sound good together.” I couldn’t change Dave and Below’s mind, they was older than I was.

When we got to California I saved Walter $900 one night because they were gonna beat him out of his P.C. money.6 Me and Below heard the cat talking, the cats that ran the show. They were gonna leave Walter out. So we went and hipped Walter, and Walter came and gave me $10! We saved him $900 and his salary that night was only about $300 and something. I said, “Man, you don’t like me. Not only you don’t like me, you don’t like nobody in the band. You don’t need me.” “What you mean?” I said, “Look, anytime I save a man $900, I figure he should give me more than that. I saved you money that you wasn’t about to get and you give me a measly $10. You take your $10 back, you need it more than I do.” I told him, “When you get back to Chicago get yourself a guitar player, I’m giving you my notice out here. I don’t like to play with nobody that thinks so little of me. I don’t want to be around you. We sound beautiful together, but when it comes down to that money, uh-uh.”

After I left Walter I had a band with Earl Phillips and Henry Gray, and who else did I have playing down there with me? I had to get rid of Henry Gray, because he drank so much wine until him and Earl Phillips get so drunk they couldn’t play. I had to get rid of one so I could keep the other one in line, and I hired Otis Spann. Otis Spann played piano with me before he ever knew Muddy Waters. Now, I don’t know where all this come about, but I read something that said Otis Spann was Muddy Waters’s brother. Now, I never knew nothing about it. Otis Spann played piano with me, man, for about a year. That’s where Muddy got Spann, from me.

Then I had a group with Luther Tucker, Charles Edwards, and Sir Oliver Bibbs on the drums. He used to be one of the old-time Dixieland jazz drummers, one of the best in Chicago. He’s an old man. I don’t know whatever happened to him. A lot of people remember him from the old school of music. It lasted about a year, I think, then I come up on Otis Rush.

Me, Below, and him had a band from about ’56. We quit playing together around ’59. I had quit playing with Junior Wells and David at the 708. I quit them at the 708 in about ’56 and went with Otis Rush, and wasn’t but us three playing together. Then we hired a cat from out of Mississippi named Willie D. Warren. Played guitar, but he had it run down like a bass. He’s from Greenwood or Greenville, Mississippi, one of them two. Then we hired a cat named Jerry, played horn, which was Below’s friend. Jerry Gibson. And a cat started hanging around wanting to jam with us named Donald Hankins, big cat played baritone. We left this place named Jazzville, a very exclusive jazz club we were playing at on a Sunday evening. We went to the New Castle Rock. We went on the road down South, and after we came back we hired Earl Hooker, that’s around ’56. We formed the biggest band in Chicago. We had the best band in Chicago. Sometimes other horn players come in and sit in, because at that time me and Otis had the only horn band in Chicago. We’d look around, sometimes we’d have six or seven horns, cats just come in, just wanna jam. We had a swinging band, played nine days a week in Chicago and, you know, there ain’t but seven days a week. We played Sunday evening and night, Monday evening and night. We didn’t hardly have time off. We played out in Gary and back to Chicago. I’ve got a picture around here somewhere of myself, Earl Hooker, and B. B. King. B. B. had the pictures made, that was back in ’56. He was playing the gig out here at Roberts Show Lounge, and me and Earl Hooker went by there to see him and Hooker got up and played for him. B. B.’s crazy about Earl Hooker, he’s crazy about him.

We cut records [for Cobra]. I was on “It Takes Time,” “Keep On Loving Me.” I cut about four or five records with Otis, I think. Yeah, “All Your Love.”7 “Bluesy” and “Just Whaling,” that was the first thing that they put my name on. I did that for Willie Dixon and this Abco cat. We was cuttin’ a session for somebody else and he just wanted something different. Dixon come in and said, “I want you to make a couple of numbers on the harp.” The band wasn’t there. Wasn’t nobody there except me, Dave, Eugene Lyon, and Willie Dixon. Eugene Lyon, he was a helluva drummer and a good entertainer, actor, too. Bad dude, boy. He’s still around, he’s takin’ pictures, he’s the photo man. He’s been doing that ever since he quit playing music. He was a hell-fire drummer. He’s playing drums in church now. He made a couple of things with Junior, and also, I think, he made a thing with Elmore James.8

Me, Otis, and Below got the job at the 708. We played the 708 till it closed in 1958 and we went back to the New Jazz Castle Rock on a weekend because we gave up on the travel, and we played there until me and Dave got something together. I don’t know where we went then. Oh, yeah, we got a job and started playing over there at 63rd and California. We had Bobby Jones, we had a good band then, a rock ’n’ roll band, nothing but rock. We played at the 1049 on a weekend, then we went to the place downtown on Rush Street and we played there until ’62. We was makin’ money then, big money. Playing rock and beautiful tunes, ballads. Only a few times I played a couple of blues by B. B. King, that’s all. We had a cat arrange for the band. You had to read the chart.

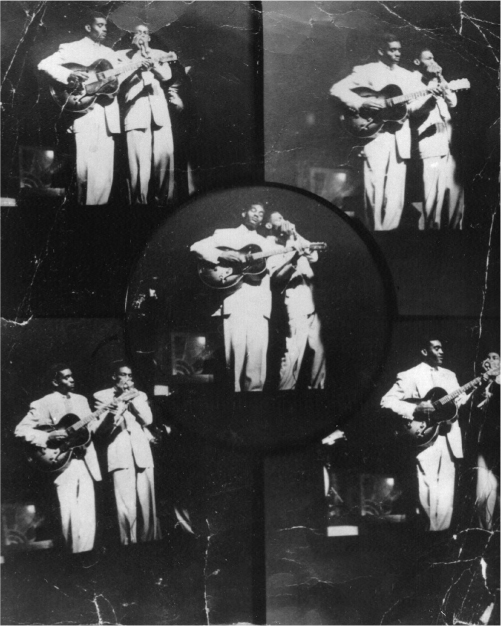

Louis Myers. Abco 104.

I recorded one or two of the songs that I did with Otis on the Blue Thumb label in 1969.9 They ain’t too good. That music and them cats out there in California don’t know too much. I didn’t even like the session. You just can’t throw a bunch of musicians together and say this is it. Some cat told me I cut with twenty-nine different artists. He had them wrote on a sheet of paper. I just couldn’t believe it and some of them cats I cut with ain’t even on it.

I cut with all the blues artists that I know of in Chicago. Chuck Berry, Bo Diddley, Muddy Waters, Little Walter, Junior Wells, Otis Spann, Shakey Jake, you probably ain’t heard that about Shakey Jake. One I cut with Shakey, a bad one, boy. It’s with me playing harp on and Shakey says it’s … (laughs) But everybody knows it’s me on it, the musicians. You see, Shakey don’t never set himself up as being a good harp player anyway. I played harp on about four of his things, and we had Otis Spann on piano, it sounds pretty good. I heard that thing when I was playing with Sam Lay back in ’67. We was coming from somewhere up in New York. We was riding along in the car and I heard it say “Shakey Jake” and that harp playing on there; even Sam Lay said, “I didn’t know Shakey could blow like that.” I said, “I didn’t either.” Then I said, “You know what? When I heard the piano I knew it wasn’t Shakey, that was me.” Shakey just sing, I played the harp. I made records with so many guys I can’t even remember them.10

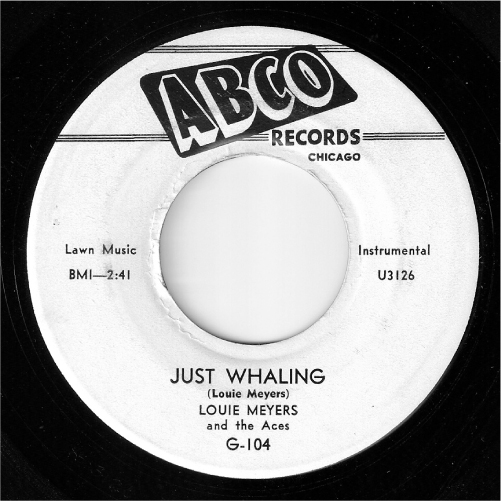

Willie Williams, Louis Myers, Robert Jr. Lockwood, Lefty Dizz, Dave Myers, Bob Myers. Ann Arbor, Michigan, September 1972. (Photo Bill Greensmith)

Have I a favorite guitar player? Yeah, I really do. I mean for the blues, playing a good blues guitar, hard blues, Eddie Taylor, he can play, man. He’s underrated. They underestimate a good blues guitar player—when I say blues, I mean blues. He can play that and he don’t try to play nothing else but the blues. Every time I meet him he’s the same Eddie Taylor I met thirty-something years ago. He’s playing the blues. I wish I could have a cat like that just to play with. I know he’s trying to get him a bag of his own now. He’s been out there a long time, longer than I have. He’s never got a break. It’s one thing that the people will accept you on and they’ll keep you right there if you let ’em, it’s being a sideman. I know he played with Jimmy Reed around here and made Jimmy Reed, the way I understand it. And I do, because I know Jimmy was hanging around out there where we was playing at. He drink a lot of wine and he was working too, and to me he didn’t care too much about playing. But he made a record and got out there and made it big, and he made other good records that the peoples liked, right down to earth.

I was playing at 90th and Mackinaw with my own band and he used to come in there.11 He hadn’t recorded one record and nobody knew Jimmy Reed then. The lady that we were playing for, I think her name was Thelma. She didn’t want him to play, because he was a wino, drink wine. I used to say let him come in and play. He come in there a couple of times and play. That cat that he had with him, he was a stone wine-head, but he could play. He could play jazz and different stuff. I don’t know whatever happened to that cat. I ain’t saw him no more.

Louis Myers. Chicago, April 1974. (Photo Bill Greensmith)

Today I like quite a few harp players. Ain’t too many harp players I don’t like. Little Walter and some things Sonny Boy did, Rice Miller. I loved some of the things he played. And I also liked Little Pot,12 but he got killed. I really loved his playing. Both the Sonny Boys I dug. John Lee Williamson had a story that intrigued me. He sings and plays at the same level. And Sonny Boy, with all that wind that he had and cuttin’ through with what he had, was alright, too. Little Walter was outstanding because he had the tone locked up. There’s no better tone with the harp than Little Walter. The only way you can get anything across, whatever instrument you playing, you got to have that knowledge that tone is the most important thing. Like today I like quite a few young fellows, but ain’t nobody playing with them. Yeah, I like all harp players, because being an old retired harp player myself, you can sit down and hear what they intending to do.

Like a lot of people say, “Man, you sound just like Little Walter,” or “You sound like this.” Any cat that is playing with a tone, because this is where it’s at, tone. I ain’t playing how much harp a man can play. I ain’t playing that, I’m playing tone. I play for tone only. I don’t play no harp or riffin’ or all that, which can’t be done on a harp anyway. I take tone and I could throw myself up against anybody if it comes to a competition thing, and I wouldn’t even be worried about ’em, because I know where they’re gonna be. I wouldn’t care about no harp players living today, none of them, because I ain’t gonna be playing what they’re playing. They’re gonna be up there trying to do something on a harp that ain’t to be done in the first place. I’m gonna be playing one kinda way—tone—and you’ll see the difference.

1. Possibly Vincent Durling.

2. “Murmur Low”/“One of These Days,” Big Boy Spires, Checker 752.

3. “Juke”/“Can’t Hold Out Much Longer,” Little Walter, Checker 758.

4. “Lawdy Lawdy”/“’Bout the Break of Day,” Junior Wells, States 139.

5. “Hodo Man”/“Junior’s Wail,” Junior Wells, States 134; “Mean Old World”/“Sad Hours,” Little Walter, Checker 764.

6. Percentage money.

7. According to Blues Records, 1943–1970, Louis Myers plays on the following Otis Rush Cobra sides: “Love That Woman”/“Jump Sister Bessie,” Cobra 5015, and “It Takes Time”/“Checking on My Baby,” Cobra 5027. However, the Cobra Records discography is not an exact science and it’s possible he is featured on other titles as well.

8. “Just Whaling”/“Bluesy,” Louis Meyers, Abco 104. “Eugene Lounge” is listed as the drummer in most discographies. This is probably a mispronunciation of Eugene Lyons.

9. “Coming Home,” Chicago Blue Stars, Blue Thumb BST 9.

10. “Respect Me Baby”/“A Hard Road,” Shakey Joke [sic], The Blues 303.

11. Club Jamboree.

12. Henry Strong.