Long associated with the stinging snap of the Fender Telecaster guitar, Albert Collins began performing in Houston nightclubs and recorded his first blues instrumental hit, “The Freeze,” in 1958. A collection of early singles on TCF Hall, The Cool Sounds of Albert Collins, marked his debut album, but it wasn’t until 1968 that Collins’s career ascended after he recorded a series of albums for Imperial that captured his furious sound.

Collins signed with the Alligator label in 1977 and recorded a series of acclaimed albums that received several Grammy nominations. The guitarist enjoyed continued success into the 80s, eventually winning a Grammy after teaming with Robert Cray and Johnny Copeland on the Showdown release in 1985 and even a cameo appearance in the 1987 motion picture Adventures in Babysitting. Collins helped usher in a renewed interest in the blues in the late ’80s and early ’90s and signed to the Virgin subsidiary Point Blank in 1991. He died November 24, 1993, silencing one of the most distinctive guitar sounds in the genre.

The following interview occurred in London on March 16 and 17, 1979, when Collins spoke with BU writers Cilla Huggins and Denis Lewis. With the release of his Ice Pickin album for Alligator in 1978, his first recording in seven years, Collins visited England and the Continent twice. Although most of his career highlights occurred after this interview, here Collins details his early family life and childhood and the burgeoning Houston R&B scene of the late ’50s, including playing in the Third Ward along with Johnny “Guitar” Watson. He also describes his move to Los Angeles, via Kansas City, with the help of Canned Heat’s Bob Hite, and his contractual problems with Tumbleweed Records.

—Mark Camarigg

A Long Conversation with Collins

Denis Lewis and Cilla Huggins

Blues Unlimited #135/136 (July/Sept. 1979)

I was born in a little town called Leona, Texas, in 1932, October 1. I’m Libra. When I was a little kid, you know, my father and mother they worked on, they call—it wasn’t a plantation but it was, he was doing farm work, for a man that we lived on his place. Like sharecroppers, right, and they made like a dollar and a half a week which that was nice money in them days. You could buy a lot with a dollar and a half. And after I grew I went to elementary school and when I got to high school I had to quit school to help my family because they kinda got in bad … and I got me a job in a service station. I worked to help my family for a while and when they got theirselves together, and they asked me was I going back to school? And I told them no I couldn’t make it ’cause I had been out too long. I stayed out of school a couple of years and I said, “There’s no sense in me going back to school.” So I got as far as the tenth grade and I quit when I had to help my family. I quit in the tenth grade when I was about nineteen, twenty.1

I have a sister, she lives in Fort Worth, Texas and I have a brother who lives in Texas also, right out from Houston and I have another brother. I haven’t seen him since he was a baby. My father, he’s there now, but he’s kinda sick. He was a guitar player, but I picked most of my playing up from my uncle. My uncle plays guitar—he’s a preacher. He has a big church in Dallas, Texas. His name is Rev. Campbell Collins. I used to play guitar in church when I started out. We called it The Church of God In Christ and I just stayed there too long, you know! (laughs)

I used to like to listen to John Lee Hooker and Lightnin’ Hopkins, which Lightnin’ Hopkins is kin to me, you know. He’s in the family on my mother’s side. And what happened is when John Lee Hooker had out “Boogie Chillun,” that was when I was kinda getting together there. I enjoyed listening to John Lee Hooker’s tune because I really admire the man, because when I first started out playing that was what I was playing, like him. You know I wanted to play like him. I was in the country at the particular time, then I moved to Houston, Texas, you know, the big city. We call it the “Big H.” I moved to Houston, well—I first went there before I started playing. I went to Houston when I was about nine years old, back and forth like 125-miles range. In the summertime when the school was out I would go back to the country and stayed for the summer with my auntie. And my mother had asthma, which she died from asthma and the climate was too low in Houston. So the little town called Normangee, Texas, that’s where my auntie was living at and my mother bought a home up there. See, my auntie raised my mother. She raised up practically all of us, you know, my brothers. She was like a grandmother and a mother, you know, when I went back up there during the summer.

Well, in the first, I was playing piano. I wanted to play piano. I really wasn’t interested in guitar. No, I wasn’t playing piano in church, I was taking piano lessons. This little town I was telling you about living in—Normangee, Texas—well, it’s like thirteen miles from where I was born. I was born in a log cabin. Well, what happened, this lady she had to come from this little town, like thirty-five miles away, and this town was called Bryan, Texas, and she come twice a week. But you know, when it rains in Texas, it floods! During the winter the weather got so bad she come once a week. She used to come like on Mondays and Fridays. So she come on Fridays to teach piano lessons ’cause we didn’t have no piano. I didn’t have nothing that looked like a piano, the piano was in the school. She come to the school to teach us, you know. It got like where, well, she couldn’t come to teach us.

A cousin of mine named Willow Young, he had a Harmony guitar, so he used to let me keep that because I wasn’t able to buy no guitar. He let me keep his. So he taught me that tuning I’m playing in ’cause he was playing that. I put one of them little pickups under the strings and started with that for about, I guess, maybe four or five months. Then I bought me an Epiphone with an Alamo amp. I think that’s what John Lee Hooker used to use. I think so, Sears Roebuck!

And that’s when I ran into Gatemouth Brown, T-Bone Walker, because Gatemouth was living at a little town called Orange, Texas, and he was cutting for Peacock Records, and he was doing a lot of shows with T-Bone Walker and Junior Parker. That’s when I went into electric blues. Gatemouth used to use that capo, and I used to have a problem using this finger [indicates middle finger] for the, you know, you use this finger for bar and for your different keys. He said, “Try a capo instead of using your finger.” I picked that up from Gatemouth Brown, because Gatemouth always uses that style to get the high range of notes. I used to go and see T-Bone Walker, that’s what really turned me to the blues. I mean as far as electric blues, I call it electric blues because I used to listen to, like I said, John Lee Hooker and I like that kind of blues. But I wanted to play jazz. But I was living near to T-Bone, ’cause he lived in a town called Conroe, Texas. That’s like about sixty-five miles from Houston and he had some relatives lived in. He was kinda raised up around that area and he lived in Houston for a while before he moved to California, and I used to hear him play a lot, you know. I kinda went off into the blues then, but I used to listen to Jimmie Lunceford and Tommy Dorsey. This is where I got my interest in the horns and everything. This was before Freddie King’s time, it was in the ’50s. I was started out when I was pretty young. Well, actually, I met B. B. King when I was eighteen. That was in Houston, Texas, and he had out the tune called “Three O’Clock in the Morning.” That’s when I first met B. B.

At this time I was living in the Third Ward in Houston. I was raised up in that ward. Like they say, it’s a ghetto, but I lived in the Third Ward off and on since I was nine years old. I went to Blasher High School, elementary school, then I went to Jackie Ace High and I got on the football team for a while. I was on the B team, not the A team! And I got away from that and Johnny Nash was playing in the high school band. Before I cut “The Freeze,” before I changed bands, Charles Washington worked with me for a long time. Me and Charles Washington started out together, just me and Charles Washington, nobody else. We used to travel, just me and the drummer, all around Texas. And he played with me for a while, but we didn’t cut no records together. He was a drummer and he started out with me.

In 1958 that’s when I cut my first record. I cut “The Freeze,” an instrumental, in 1958, on the Kangaroo label. We had a dispute about that. See what happened was that … okay, I had it first, I put it out first. Fenton Robinson and a guy named David Dean was playing on me, on my tune called “Frosty,” and he played “The Freeze” with me. He played with me for, like, four years. So what happened is that they went and re-cut it.2 Don Robey got mad with me and stopped my record from playing on the air for two weeks because I wouldn’t sign no record contract with him. I didn’t like him! I don’t care you put it out, I didn’t like him. He’s dead now, I don’t care! But I didn’t sign with him, I stayed on my own. He tried to make things very awkward, but I had … The Kangaroo label had paid the superintendent of KCOH radio, and I played for their grand opening for this radio station, which is still there now. And Don Robey went down and stopped my record from playing for two weeks, and this record company had already paid these people to play my record on the air. So he was fixing to get sued, so they said, well, man, after they found out what had happened, you know, they said, “We can’t do this, ’cause Kangaroo Records have done paid this radio station to play this thing.” That’s the way they had it, when payola was going out at that time.

I played behind a group called the Dolls, an all-girl group. That’s how I got my first record. My band was backing them up. It was R&B, you know, we weren’t really playing nothing like no disco, but they was singing like the Inspirations. That was on the Kangaroo label. See, that was two schoolteachers, one schoolteacher and this Henry Hayes guy. He’s a saxophone player. He used to back me up with my group, because he was a music teacher and this other guy was just a regular schoolteacher. His name was Mel Young. And they were the ones that had the Kangaroo label, including the Great Scott, that when they brought him in. ’Cause the Great Scott was the one that introduced me to doing—they had some studio time left and they said, “Hey, man, those tunes you been playing, why don’t you go ahead and play this for the next thirty minutes, you already know it in the band already. Let’s see if you can run it down right quick.” So I played “Freeze” and “Collins Shuffle.” I had Herbert Henderson on drums and I had a left-hand bass player named Bill Johnson and I had Henry Hayes on alto sax and I had Tiny on tenor. We called him Big Tiny. His name was Cleotis Arch. Frank Scott and Mel Young and Henry Hayes were running Kangaroo. Frank Scott, they called him “The Great Scott.” He lives in Chicago right now, not the one lives in Los Angeles!

“The Freeze” was first and “De-Frost” was second, on the Great Scott label. “De-Frost” was in 1960. What happened is the Great Scott beat me out of some money, this money-type thing. So he hooked up with, he’d already hooked up with Bill Hall after we did “De-Frost.” He got in touch with Bill Hall in Beaumont, Texas, and it’s called Hall and Clement. See, him and Jack Clement had this studio in Beaumont, Texas. At first Bill had his part and Jack Clement had his part. So they joined together and that’s the reason they called it Hall and Clement. Right down on Pearl Street in Beaumont, Texas. They on Belmont Street now in Nashville, Tennessee. They was producing, like they were producing country and western at first, but Jack, that’s what he’s still doing now, but he changed over after the Great Scott went down and talked to him about me. I met the Great Scott in Houston, Texas. He come to hear me play. He had heard me for a long time. He used to play with Jimmy Reed, play guitar hisself. He come to Houston. He was handling this kid, Little Frankie Lee. He was handling him, and me and Frankie Lee used to work together, so he asked me about cutting a record.

It was the Great Scott that took me to Bill Hall in Beaumont. They used to have Johnny Preston, “Running Bear,” that kind of stuff. They had the Big Bopper, too, “Chantilly Lace.” Right along about that particular time it was called Big Bopper Enterprises, ’cause it was named after the Big Bopper after he got killed in the airplane crash. So he went down and made a deal with Bill Hall about pushing this 45, ’cause during that particular time Booker T and the MGs had “Green Onions.” And instrumentals were selling in that particular year, ’cause I didn’t used to sing. I just played instrumentals and instrumentals always went over big in Texas. Yeah, instrumentals and the Louisiana beat.

Houston was a city of blues and jazz mostly. Lightnin’ was playing everywhere. I was fronting then. I used to play behind a lot of musicians that would come into town, like, by themselves. Like I come over here by myself, I’d back ’em up, you know. I had my own group, like I said, I had Big Tiny … well, back and forth, me and Johnny “Guitar” Watson had the same musicians. Yeah, Johnny used to play piano for me. Piano is his major instrument. He just picked up guitar. He’s a little bit younger than me. I knew his whole family, his mother and all of them.

Clarence Green? Yeah, Clarence, he had his own group all the time. But we used to run into each other every now and then, you know. I know him as a person, but as far as we playing together, no. He had a little group called the Blues for Two, which wasn’t but two guitarists and drums. They made a big name for theirselves around there for a while. Albert Reno was on the other guitar. He lives in Austin, Texas, now, last time I seen him. I think he did some session work for other people. He’s a pretty good guitar player. Cal Green, yeah, he worked mostly with the Midnighters at different times.

Clarence Holiman? Well, his brother used to play with me before he passed away. Clarence Holiman, he had a brother that played piano. We called him Sweetheart. (laughs) Well, he was really sweet, you know, whatever. He drank hisself to death. He died a young man. Clarence Holiman played some things with Bobby Bland, Junior Parker. He’s out in Los Angeles now.

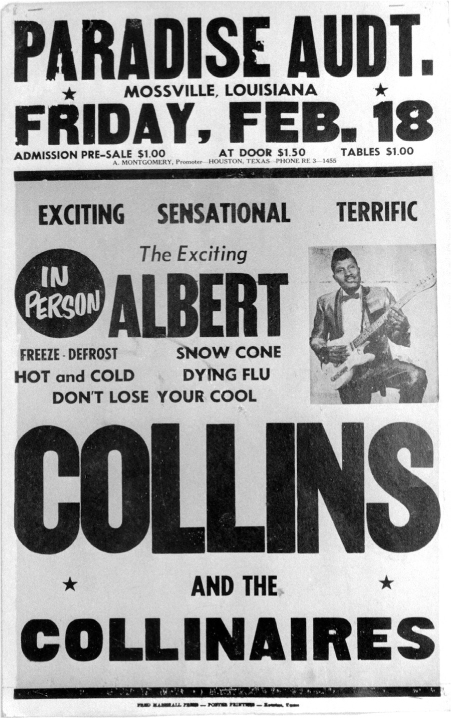

Albert Collins poster, c. 1960.

Little Joe Washington? Oh, Little Joe! Little Joe stayed right across the street from me. He’s hanging out there, he’s still playing guitar. Yeah, people used to think he was crazy. Fall all out on the floor, play dead! He had a thing going. He used to do all that kind of stuff, you know. He do everything—play with his toes!

Johnny Copeland? Well, Johnny and a friend of his named Joe Hughes played guitar. They used to play together. They had a group something like the Clarence Green group. And Johnny Copeland put out a tune called “Down on Bended Knees.” And he kind of sung like this guy named Nappy Brown. Well, I used to do some shows with Nappy Brown, in Houston, and around the little small towns around Houston, a hundred and two hundred miles radius. Johnny’s trying to get something happening for him now. He lives in New York now, but he kinda got away from the music for a while and he’s back into it now. He had a nice record one time, “Down on Bended Knees.”3

Jimmy Nelson? Oh, yeah, “Meet Me with Your Black Dress On.” Yeah, I played with him, but I didn’t play with him too long. I played with him around Houston, playing little old jobs we were making about six or seven dollars apiece a night. He was working at a steel company. I think he drive a truck for a while, too. He didn’t make it really that big. He had a good job, so he just doing records like a hobby. He was—that “Meet Me with Your Black Dress On” was a good seller for him at that time. He went out for a little while, but he didn’t stay long. He didn’t care too much about traveling. From what I heard he’s still in Houston now.4

Joe Fritz played with me for a little while, but he used to back up Junior Parker and all of them. He’d blow alto. You ever heard of Joe Scott? He had a good band in Texas one time, he’s a trumpet player. I just got his number, he lives right around the corner from my home right now. He’s the one that wrote “Further On Up the Road” and all that stuff. He arranged all that stuff for Bobby Bland. Anyway, Joe Fritz stop playing, you know, he always, he do a lot of working on cars. He likes to do that. He’s mechanical and he used to do all the sessions and stuff for Robey. So I heard that he’s gone back into music and they say he’s still really sounding good. I haven’t seen him in twelve years!

Bill Harvey? He was a sax player. He used to back up B. B. and a lot of … he’s dead now. I never worked around him too much. He’s been dead a long time. Good saxophone player, too. He had a good band, too. John Roberts, you ever heard of a group called John Roberts and the Hurricanes? Well, he played a lot of stuff around with some of Robey’s stuff. Well, I guess he wasn’t too big. Archie Bell and the Drells, I hung out around with all them guys. See, we were all raised up together.

The deejay King Bee, yeah he was at KCOH and he helped me out quite a bit on my records. Most disc jockeys—there’s a lady jock her name is Gigi. We called her Gigi, her name was Gladys Hill. She helped me out a lot on pushing my records like “Frosty” and “The Freeze,” you know, and she passed away not too long ago. She had cancer. She did a lot for a lot of musicians, but I was her pick, you know, because we used to go and do gigs together, because she sang, too. She’d go with me and my band.5 I had the same guys, Bill Johnson on bass, and Frank Mitchell, a trumpet player, and a blind trumpet player. I had two trumpets and a tenor at one time—I had everything. I always wanted a big band sound. I wants it now!

I stayed away from home a whole year once and I didn’t even see my house. Yeah, with Piney Brown, that was in ’54. I came back home day after Christmas, the day after Johnny Ace killed himself. Stayed on the road a whole year! I enjoyed it. It don’t make me no difference. I wasn’t living out of a suitcase, I was living out of New Orleans. I stayed in New Orleans six months. I was married then to my first wife. Traveling? I had a wagon, a station wagon. I bought one of those Chrysler limousines. I used to put a trailer behind it. It had three seats in it and my band traveled like that.

Johnny Ace’s death? Yeah, a couple of weeks, three weeks before that happened a guy that played in the band with him was telling me, and well, his cousin played with him. This guy wasn’t playing, he just said his cousin told him. Say he was driving along one day, Johnny Ace, he just pulled his gun out and starting shooting at road signs, shooting at rabbits. Then he just take one bullet, they say he had been playing with that gun for three weeks. Take the bullet out and point it at you, but he wouldn’t pull it. Take it again, spin the chamber, he might put it in his arm like he gonna shoot himself. He did it too many times. He did it the wrong time, because he pointed it at this girl, her name was Shirley. I know her well. I been knowing her a long time, because I used to go to school with her. But anyway, she was there with him that night, because he had been going with her off and on. He spin it around and pointed it at her head and she said, “Oh, don’t do that, baby, don’t play with no gun like that,” and he said, “Oh, I ain’t gonna hurt you,” and he spin it around like this, “Bam!” He fell over in her lap. She said she kept that skirt she had.

Shirley, yeah, she still alive living in Houston somewhere, I guess. I don’t know, it’s been a long time since I seen her. If she’s still there or done moved somewhere else. But Willie Mae Thornton can tell you where she lives, ’cause Willie Mae go back and forth home all the time, back to Houston. I came in the day after. See, he killed himself on the Christmas Eve. I come on the Christmas. He killed himself on the 24th of December, 1954. I came home Christmas Day to spend Christmas, because I had been gone a whole year and I heard about it. There’s a lot of little different stories about that, you see, because, like, one time I talked to Willie Mae about it, she didn’t want to talk about it. In other words, cut me off and told me to shut up, you know.

Well, what happened is his contract was gonna be up with Don Robey. See, he had a pretty nice record out at that one time. He had went and said to somebody else and they went back and told Don Robey he wasn’t gonna sign with Peacock Records. He was gonna sign with somebody else. I guess under cover somebody was … See, Robey he jumped on Gatemouth Brown one time. Gatemouth Brown almost killed him! He jumped on Little Richard, put Little Richard in the hospital. He was fooling around with Robey. He had been working some shows for Don Robey. I played with Little Richard when he had a band called the Tempo Toppers. I took Jimi Hendrix’s place when he came to Houston. He had been playing with Little Richard. So Hendrix went with the Drifters. That’s when Hendrix was playing the blues then. He went on to those other things later on then. Hendrix was about eighteen or nineteen years old when I met him. He was coming there with Little Richard. So I finished a date with Little Richard, part of his band and part of my band, because a lot of them guys left Little Richard. Because during that time Richard was going through some problems about paying the musicians. You understand what I’m saying? So I went along and did six dates with him and about two months later Don Robey jumped on him, put the man in the hospital, something about contracts or something. I don’t know what happened. He’d (Robey) hit you, man, put his gun in your face and say, “You’d better not hit me back!” That’s the way he did that kind of thing. He was heavy, a pretty heavy dude. Got mad with me ’cause I wouldn’t sign with him. He said, “I’m gonna stop your records from playing!” I said, “I’ll tell you one thing, I bet you they’re gonna play again.” He said, “You smart, ain’t you?” I said, “Uhm-uhm.” Gatemouth’d like to kill him! He know better than to jump on Gatemouth. Gatemouth’s a cowboy. Gatemouth put his boots all over that butt! Every time Gatemouth would hit him, he put his pistol in his face, told him, “Don’t you reach in your pockets, I’ll blow your brains out!” Gatemouth’s crazy! But now that Robey’s dead, Evelyn Johnson got everything. Evelyn Johnson, she had the booking agency. She just took over everything.

Well, she used to wear them, you know, the old overalls with the hammer thing, where you hang your hammer on, and rubber boots that come up to here (knee height). Well, she’d fold them down in the summertime. She’d fold them down, you know, it would be 105 degrees, man, she’d be steady walking. She wouldn’t walk on the sidewalk every time, she’d walk in the street, where people could see her. With that cap on her head, with beer, and looking mean. You can’t upset her, she fight woman or man. Don’t make her no different.

Some lady told her one night, say, “You look good, but you need to get out of those boots, man.” She slapped that woman. Well, she went to slap her, but the lady ducked, you know, those old rickety tables in one of those old nightclubs, and all the drinks fell over on the floor, and she called her all kinds of names, man. “These my boots! I wear them when I get ready.” She don’t like you to talk about her boots. You know, Don Robey talked to her one time about going on a show with Bobby Bland and Junior Parker with them boots on. Yeah, she go up on stage with those boots on, with her overalls on. During them particular times when you played clubs you had to kinda look decent, you know. It took them a long time before they could make her put on a dress. She don’t wear dresses, I know. I saw her in one dress since I been knowing her! She feels uncomfortable in it. She wears just pants now and a shirt, and her cap. They put her in a dress one time to take a picture. It took two weeks to convince her. “You’re a lady. Put a dress on!” I remember that one, but she pulled it right off when she made that picture. I bet she came right out of that dress. She don’t like dresses.

We played in Portland, Oregon, together and she ordered a six-pack of Budweiser beer backstage and she say, “Get you a beer, Albert.” I said, “Well, okay.” So she handed me a beer, ’cause she opened it. So I said, “I can’t drink no two beers,” ’cause I can’t drink too much anyway. I say, “I’ll just drink this. Me and my wife will drink it together.” So she put something in my beer, man. I just took a little taste. It didn’t bother me too much, but it knocked my wife out. She just fell over this way. I said, “What’s wrong with you?” She said, “I don’t know. I can’t walk!” She just went out, and Willie Mae’s just sat up there just laughing. I took my wife to the car and some policemen came by and it was during the winter and they saw the steam coming from the engine. So they checked the car and she was laying down in the car. So they woke her up to tell her to crack her glasses, you know, the carbon monoxide would have killed her. When I got back to Los Angeles, maybe about a couple of months later, I saw Willie Mae. One night she came in I was playing at the Troubadour, with Joe Turner, and she started laughing, and she said, “How was that beer?” I said, “I oughta take this chair and go upside …” (laughs) She always pulling those little funny pranks. She likes to do that. I didn’t drink too much of it, but it almost made me not even play my gig! I don’t know what she put in there, but it’s some kind of stuff they put in your drink and it knocks you out. I don’t know what she did! It was funny to her, but it wasn’t funny to me, ’cause I didn’t know what was wrong with my legs! It might not knock you out. It just make you feel good, ’cause she was probably using it herself.

I left Houston and went to Kansas City, Missouri. I stayed in Kansas City around about three years. That’s where I met my wife. That’s where my wife’s from. I was working out of Kansas City. I worked in Kansas City, but I was working through an agency there that was connected with the Buffalo Booking Agency. They was good friends. I liked Kansas City and I decided I wanted to stay there for a while because my mother had passed away and I didn’t want to stay around Houston for no memories. I just got away from everything. That’s the reason why I stayed there.

In Houston in 1965, I did the session with Big Walter Price, “The Thunderbird.” I played the guitar on the Big Walter “Thunderbird” session. That was at his house, that’s all that was, it wasn’t no studio. We only recorded a couple of numbers, that’s all. I just went over his house one day because he was trying to get a tape to send to Mike Leadbitter. It wasn’t no big thing about that and I left. I was in a hurry, too, anyway, ’cause I had to go outta town. You know, Walter, he was trying because me and him were supposed to be coming over here together a long time ago. He knew Mike Leadbitter, and I don’t know, somebody screwed up somewhere and we didn’t make it. I think Walter messed it up. I got the record at home. I got the tape on it. Dick Shurman, he’s the one that gave me the tape, like I’d forgotten about it. He had this tune, Big Walter had this tune “Get to Getting”—“Take the baby home, pet her and put her to bed.” I played on that, too. I think he still got the tape. He told me he was going to send it to me. [sings the song] It’s a kind of weird way he plays it. Yeah, he’s something else.6

In 1969 I met the Canned Heat in the Third Ward at a place where I was playing called the Ponderosa. I was playing there, just like on Wednesday nights. They was playing at the Music Hall and Bob Hite was looking for me. So he went and found Lightnin’ Hopkins and Lightnin’ told him where I was playing, ’cause Lightnin’ used to come up to hear me every Wednesday night. That’s the way it happened. See, Bob come with that beard and that long hair, and I said, “What is this, Jesus?” He come up and asked me and said, “I’m Bob Hite.” I’d heard of him but I didn’t know he had that beard and that long hair. “Well,” he said, “We been looking for you, man, we talked to your cousin Lightnin’, told me you were up here.” I said, “Yeah.” He said, “We’re with Imperial Records,” and they had called down to Bill Hall, you know, down in Beaumont. Yeah, Bill Hall was looking after me then, that’s before they moved to Nashville, Tennessee. So Bob said, “Why don’t you try to come out to California, man? We can help you out.” So he wrote the liner notes on my first album with Imperial. I wanted to get out of Houston. There wasn’t anything happening in Houston. Playing in little small clubs, I got tired of that, man. “Chitlin’ circuit” we called it. It was pretty bad for blues, ’cause, you know, trends changes and they was into jazz and that’s when this rock stuff came out with the psychedelic.

I was booked at the Fillmore West. I played there with the Who, B. B. King. I played there with Elvin Bishop, Mike Bloomfield, Buddy Miles. I just (1979) come out of a strictly rock ’n’ roll club, the Body Shop in Vancouver, Canada, which surprised me.

I got into organ, you know. I been into organ for a long time, because I used to be around Jimmy Smith and Jimmy McGriff. Jimmy Smith used to come to sit in with me all the time when I’d play. He owns a club in the western part of Los Angeles called the Jimmy Smith Club, I think. He’s out there now. Last time I played with him was down in San Diego. See, I been around a lot of those guys, you know. I was just learning, trying. I was around Wes Montgomery in the Midwest. I first met Wes Montgomery in Kansas City, Missouri.

Like Ike Turner, he’s from St. Louis. I did some, I did “Bold Soul Sister” for him, and I did The Hunter album with Tina. Ike was playing piano. That’s his instrument, piano. He just picks that guitar, you know, because he’d been on the show. Go on and see the Ike and Tina Turner show, he’d stand out front. He just picked up guitar, like Johnny “Guitar” Watson. Ike felt like he got to a limit when he’d get ready, ’cause he played a certain way and he said, “Man, I want you to put some blues on top of this.” He’s kinda strict about his music as far as on the bandstand, but I have never worked with him on the bandstand. I wouldn’t sit in with him. He’s kinda hard, he’s very strict about his musicians. My name wasn’t mentioned on The Hunter album at all, ’cause I was signed with Imperial Records and Ike felt like he might get sued. They put my name on that record as “Al Jackson.” But a lot of people knew that was me playing. I didn’t get no recognition from that at all, including “Bold Soul Sister.” I did it on a Sunday evening. He just paid me for the session, did it in about six hours. Tina already had the material. I just went right on and played in the studio, no overdubbing at all. It was just a straight session. I took the main guitar work all the way through and Ike took the piano.7

After The Hunter I did a lot of overdubs for Ike in Los Angeles. When I wasn’t doing too much, wasn’t traveling too much, I’d go out there to Bolic Sounds and do some stuff. He’s got a lot of stuff there that I overdubbed that he didn’t release. They’ve got material now. I just went and did overdubs for him. I stayed there three days before I even came outdoors. (laughs) I said, “Man, I got to run,” and he said, “No, no, no, man, wait, wait. I’ll call and get you anything you want.” See, Ike is a very funny guy. He’s a guy that is self contained, you say? She ask him once for me, go, to come over to London with them. They was coming over here, and he was so into his studio thing. He said, “No, I’m gonna keep Albert here with me, ’cause I want him to stay with me.” Well, see, he used to fire—he fired one guy, he was a real nice-looking kid, used to play with James Brown. Played guitar, he was real bad, too, man! I forget that kid’s name. I met him in Freeport, Texas, when they played in Freeport, Texas, and he fired that kid the same night, ’cause he went up and got in Tina’s face, and Tina said, “Hey, he’s a cute little …” Ike said, “Hey, man, here’s your check!”

After the session work with Ike and Tina, I went back out on the road. I was playing, you know, Pacific Northwest—Portland, Oregon; Seattle, Washington; and Canada. Yeah, I was living in California—Los Angeles. I had my own group—well, I took this guy he played with me, like, seven years. Booker T and the MGs’ drummer, they call him Spider. His real name is Larry Daniels, he’s from Kansas. We played together in Kansas City, Missouri. He lives in Long Beach, California, now. And I had an Indian kid that played saxophone with me, his name is Sonny Boyan. Very good tenor man, and I had an organ player name Mike, played B3 Hammond, and a bass player named Mike Rosso—he moved to Oregon, and he quit playing. I also played with Howlin’ Wolf in Kansas City, Missouri. I played with him at the last gig he played before he died, in Seattle, Washington, a place called Six Stadium. He was on a kidney machine at the end. I played the last gig with Wolf before he passed away. Him and Koko Taylor, and Hubert Sumlin was playing guitar with him.

I was without a recording contract from the time I did the Tumbleweed. Oh, I’ll tell you what happened behind that. See, I was signed with Tumbleweed Records for four years, and Gulf and Western was backing it, and this guy took the money and came over here. Now he’s in Seattle, Washington, and the company folded. I called one day and the phone was disconnected and I panicked, you know. So I seeked around and found out that ABC Dunhill had bought all my stuff from Tumbleweed. J. Geils—the group J. Geils—they went with Atlantic Records. So I goes to ABC Dunhill and I tried to get on with them since they had my material and I was two weeks late! Evelyn Johnson from the Buffalo Booking Agency signed Bobby Bland and they already had B. B. King. So the guy turned and said, “Man, I wish you would have been here earlier, but I got enough blues right now.” I hung out and hung out, so Dick Shurman got me with Alligator Records. ABC bought everything from Tumbleweed. I’ve got about four or five tunes that wasn’t released. Well, Bill Szymcyk, he didn’t produce the album like I wanted, ’cause I asked him to let me be there when he got ready to overdub the reed sections. But I had to go to Canada and they held me there too long, and he [was] trying to hurry up and get his stuff done. Because he had to produce somebody else—he’s steady on the road all the time—and we did the overdubbing in Los Angeles. I didn’t like that album too much. It sounded too commercial. The singers was one chick and a guy, that’s all it was, that’s all. They really weren’t no singers.

When I’m on the road now in California, I pay my band by the week, weekly salary. But when I was in Texas, I’d give them the money every gig, each night we played. No, they [the musicians] didn’t have contracts on recording sessions in them days. All they’d do was pay you for the session and that’s it. It was olden days; they’ve changed all that now. Many times I felt I was being ripped off back then. Yeah, well, people been getting ripped off for a long time. In this kind of business a lot people don’t realize how they can get ripped off so bad, because they only want to get on a record. That’s what I was doing the first time. The second time I did, when I played “De-Frost.” I got with Hall and Clements. I didn’t care what happened, that’s when—this is a record company, ’cause these other guys only owned little labels anyway, doing nothing—I said, “This here’s big enough for me.” And then this Great Scott turned around and beat me out of 1,800 dollars. That’s a lot of money in them days.

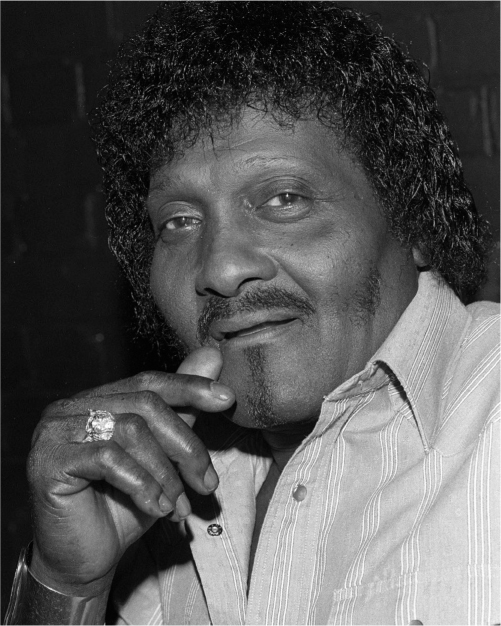

Albert Collins. (Photo Denis Lewis)

Well, see what happened, I had some royalties coming. He went down and collected the royalties, and I didn’t know this. So I called down one day, I needed some money, I was buying a house. We did a contract over and he told the man don’t come to his office anymore. I didn’t get my money. But I always get my own cars. Now, this last album I cut with Tumbleweed, they bought my equipment, like amplifier. But I bought my van, I bought it brand-new. I pay for my own stuff. I don’t like no record company to give me anything. I might want to say, “I don’t want to cut no more for you, man. I ain’t obligated to you!” ’Cause, see, where a lot of musicians make their mistakes, see, you sign a contract and you go out there and buy one of those expensive cars on your contract—you got to sign another one!

Man, when I first met Bruce Iglauer, I like him. You know, a lot of record companies they cut you, they don’t care if you’re out there, you’re on your own. I’ve had my first Alligator album out now. Next I would like to have a live album. I got a band in Chicago, that’s with Larry Burton and Aron Burton. I got Casey Jones on drums and I’m using A. C. Reed. You know, he play with different people. He played with Son Seals, but I’m keeping him with me, you know. He’s playing electric saxophone all the time now. I talked to Bruce about me playing with a disco band and seeing how it sounded, run some tracks down. He was kinda interested in it, but you know he like that blues. He say he was excited because all his artists is out of Chicago and, see, Chicago blues and Texas blues are different blues.

I tried to find my directions, because I had my directions. What I wanted, my own creations, because, like I say, I’m listening to those guys. Man, you can play blues so long it all sounds the same. I play a lot of twelve-bar changes, ’cause I wanted a different show from the rest of them guys. I didn’t wanna go on the bandstand and just sit there and play, just stand up and play. I like to have the energy! That’s another thing I worked on was the energy. You know, I did a show with Albert King, and after you done heard about three or four of his numbers you done heard his whole show. I mean a lot of people say this. I’m not putting him down, ’cause, I mean, I admire the man. He admires me, too. If I deliver my own creation, or whatever you do, you automatically get the respect. If you carry yourself in a respectable way, that’s the way I think about it. I wanna keep on going up that ladder. That’s what I want, high energy!

1. Leaving high school in the tenth grade would probably put his age closer to sixteen years old.

2. Fenton and the Castle Rockers, “The Freeze,” Duke 190.

3. Johnny Copeland, “Down on Bending Knees” [title printed on original 45], Golden Eagle 101. [Following a revitalized career, Johnny Copeland died on July 3, 1997.]

4. [Jimmy Nelson died on July 30, 2007.]

5. Gladys Hill, “Prison Bound”/“Please Don’t Touch My Bowl,” Peacock 1618. This is possibly the same artist.

6. Big Walter, “My Tears”/“Houston Ghetto Blues,” The Thunderbird, Flyright LP527.

7. Ike and Tina Turner, The Hunter, Blue Thumb BTS11.