Problems and Tactics Table: Craftsmanship

Craftsmanship is the process of making things extraordinarily well. It involves fits and finishes, obsession with details, tender loving care, and pride. The topic was easier to talk about in the age when objects were made by individuals and by hand, though it is still possible to look at sculpture, custom jewelry, fine woodwork, and exquisite “craft” pieces and comment on the craftsmanship. These comments, however, may be off the mark. We amateurs might be terribly impressed by a polyurethane coating, but a professional woodworker would realize that a rubbed mixture of alkyd varnish and oil, or simply the bare wood enhanced by the patina of use over the years, would have been a better fit. Still, most people are comfortable in thinking they know what craftsmanship means in the case of individual hand craftsmanship. How about in the case of airplanes or motorcycles, plastic spoons and pizza boxes, nails, hangers, or any of the other items spewed out of modern industry. Is craftsmanship still an issue? Is it important? And if so, why?

To neglect craftsmanship in the production of industrial products is foolish—perhaps in the long run suicidal. Craftsmanship is a state of mind that permeates design and manufacturing and is highly appreciated by consumers. Its importance was obvious in the 1980s in the ascendancy of the Japanese automobile industry. Immediately after World War II, countries such as the United States were convinced that Japanese products were low-quality copies of Western brilliance. In hindsight, this thought was somewhat myopic. In fact, the Japanese have had a long tradition of outstanding craftsmanship and at the time were suffering from the war that had left their economy and industry in a shambles.

In the 1980s, Japanese automobile makers were noticed for their “fits and finishes.” Much was made of the extraordinary evenness of the spaces between door, hood, and trunk panels and body panels on Japanese cars, while U.S. automobiles were criticized because their paint jobs were inferior. It was apparent that the care and attention to the manufacturing process in the quality of the exterior was reflected throughout the automobile, accompanied by greater reliability and eventually leading to higher market price and increased sales. The U.S. automobile industry was caught by its complacency and is still scrambling to reacquire its reputation for outstanding quality against not only Japan but also Germany, and soon South Korea.

After World War II, there was a large market for automobiles in the United States because production had been halted during the war effort and now a large number of drivers were returning from military service. U.S. automobile companies were in heaven because many of their former overseas competitors had suffered major economic and physical damage. They were able to operate at the same (or diminished) level of craftsmanship until the recovery in other countries allowed ancient traditions of craftsmanship to become apparent, augmented by new approaches to production such as the Toyota production system. You no longer hear Japanese products referred to as cheap copies.

Good craftsmanship results in aesthetic pleasure and pride both to the manufacturer and to the user. Museums display the ancient implements and artifacts of our ancestors, and even those from the Stone Age have a certain functional beauty. We humans have been making and then using things throughout our history. Therefore it is not surprising that we would derive pleasure from well-made products.

One of Stanford’s anthropology professors, John Rick, occasionally entertains people by making tools from flint or obsidian in the quadrangle or in his talks and lectures. The process consists of chipping or flaking the rock until it acquires the shape desired—and the results are quite beautiful. The chipping, if properly done, is fairly regular, but there is always a slight variation to each one that makes the individual finished object somehow more interesting. This phenomenon is well known to anyone who is an artist and associated with handmade objects. The shape of these tools is functional in a simple and satisfying way. A chipped obsidian edge is said to be sharper than a sharpened steel edge and capable of holding its sharpness longer.

Undoubtedly the users of stone tools made and utilized utensils, storage devices, decorations and totems, and other items that have not all survived the years. Those that have and that we respond to most strongly are considered “primitive art” and put in museums to be wondered at. Attendance at so-called crafts fairs shows that we still value handmade objects, which are often imbued with rough and irregular characteristics. Blacksmithing has become a hobby for some, and evening education programs are replete with courses in ceramics, weaving, and other such ancient activities. Many of us build things as a hobby and gain increasing pleasure as our skills become more refined. Craftsmanship encompasses a wide range of human activity, and the pleasure we receive from it has certainly not diminished, even over hundreds of years. As we encounter more recent well-made products—Grecian amphorae, 17th-century suits of armor, Hepplewhite furniture, restored Brass Era automobiles, Barcelona chairs—we respond even more strongly.

There are several reasons for the aesthetic pleasure we gain from well-crafted products. First, we are impressed by surface beauty. Silver is appealing to us because as it wears, the surface acquires a finish (called a patina) that is reflective, but not a mirror. We can see the nature of the material rather than just our reflections. With age, surface patterns are emphasized by oxidation that is missed by the polish rag, and the overall nature of the item takes on a mellow glow. For such reasons, antique silver pieces are often more attractive than newly manufactured ones. Wood is appealing to us because of the variation in color and pattern and because of the glow of a nicely done finish. Perhaps, like me, you wonder at the highly polished, probably urethane-based finish applied to wood used in some automobile interiors. Wood is a difficult material to use in an industrially manufactured product and is undoubtedly there for its appearance. But why cover it with a finish that makes it look like plastic?

Pleasure also comes from the juxtaposition of various materials, shapes, colors, and finishes, one of the attractions of antique mechanisms and instruments and many sculptures. This attraction might make you wonder about the present trend to cover things up. For example, many modern “luxury” cars place shrouds over the engine, so it is not possible to see the details of the engine itself. I suppose they are aiming to please customers with an allergy to things technical, but it is not much fun to lift the hood on such a car. Often the engine is aesthetically much more interesting than the shroud. To me an engine, especially a clean one, or even better one detailed for a roadster show or a concourse, is a beautiful thing. Ferrari has taken advantage of this aesthetic by exposing the engine to view. Similarly, the inside of an electronic device is more interesting and shows more craftsmanship than the outside. For a brief time Apple made a small desktop computer that was available with a transparent cover. Remember that one? I still have one even though I no longer use it because I enjoy looking at its internal workings. If consumers gain pleasure from well-crafted objects, why do producers cover them up?

People also are impressed by things they recognize they could not, or would not, do. I have spent a great deal of time in my life working with wood, metal, and other materials on hobby projects ranging from buildings to steam tractors to model ships. In my professional career I have acquired a fair amount of skill at making things and am, perhaps as a result, filled with immense pleasure (and perhaps a bit of envy) as I encounter things that I do not have the skill or patience to do. A perfect weld bead, a proper and exquisitely crafted wood joint, a flawless paint job, or a machining job that seems to me impossible not only pleases me, but makes me want to get to know the person who brought forth the miracle.

But good craftsmanship brings us more than just aesthetic pleasure. It also implies pride on the part of those who made the product, which is usually an indication that the object not only holds intrinsic beauty but also functions well. If a Lexus, BMW, Mercedes, or Porsche had a crummy paint job and visible rough sheet metal edges, you might suspect it would not be mechanically reliable or sophisticated in its performance—and you would probably be right. Good craftsmanship implies good performance and vice versa. And in the purchaser’s eye, craftsmanship implies that a company cares about details and therefore produces outstanding products. Such craftsmanship is highly motivating to the people doing the work, as it is a matter of pride and satisfaction to all concerned. The company loses a great deal of potential if it does not keep this in mind. Craftsmanship is a factor in pride, and pride is a factor in producing high-quality products. Look closely at a Honda motorcycle or talk to the people who make them. The craftsmanship, the pride, and the quality are obvious. And they reinforce each other.

I have worked quite a bit on craftsmanship with a wonderful company in Pune, India, named Forbes Marshall. It is a family company now run by Naushad Forbes, who was a Ph.D. student of mine, and his brother Fahrad, who studied electrical engineering and business and was a Sloan Fellow at Stanford. Naushad is particularly interested in craftsmanship, and the company has done a great deal in that regard. The first time I visited the company some 20 years ago, it, like many Indian firms, was creating products under license to a European company. The reason for my visit was that Naushad was particularly interested in increasing exports and the number of indigenous products the company produced, and he thought I could help.

The first thing I noticed when I stepped into the lobby was one of the impressive products the company manufactured (an electronically controlled valve) on display. But I later found out that it was a unit that had been made in the European plant rather than their own. When I asked the reason, I was told that the European-made one was “better” than the ones they made—a clearly unacceptable attitude. Although the units that Forbes Marshall manufactured were built to the same specifications as the ones made in Europe, the castings were rougher on the outside, the paint was applied by hand with a marginal brush and no use of masking tape, and after completion the units were put in a rough bag made of jute and packed in straw in a somewhat poorly made, though strong, box. The shipping address was then applied to the box with an even more marginal brush. The net result would not have thrilled a customer in Germany.

Because of Naushad’s commitment to higher quality and his position in the company, and maybe a little bit because of my ranting and raving, things began changing rapidly. By my next visit, masking tape, sprayed paint, cartons and foam cushioning, and labels had appeared. On a later visit I found that the company had given its foundry suppliers a good going over and the exterior of the cast parts was much improved as well. Now the products in the lobby are made in their own plant.

As the company continues to improve the craftsmanship on its products, the products’ reliability and performance also increase, as does the international reputation of the company. And the pride and confidence of the employees has grown to the point where they have a large number of their own internally designed and manufactured products. In a recent visit, I ran across a particular high-precision instrument that measures fluid flow by means of vortices, which at one point worked very well but definitely had rough edges. The item is now beautifully made, and performance and sales have improved along with the crafts-manship—a common story.

There is a tendency to associate good craftsmanship only with surface finish, which is why I stress the fact that craftsmanship requires an attitude that affects anything one works on. But even surface finish can have profound functional effects. Failures are often associated with so-called stress concentrations in structures, which may be due to localized damage during manufacturing or assembly, or to wear associated with heat treatment or finish of parts that move against one another. Thermodynamic efficiency is often dependent on such things as smooth fluid passages and precise burner geometry. Corrosion resistance demands tight control of surface coatings. The list goes on. Quality definitely depends upon the details, and the details depend upon craftsmanship.

Good craftsmanship also implies that the product was designed to be easily manufactured, which in turn implies it was well designed. Good product designers keep manufacturing uppermost in mind. An example of this mind-set is found in the case of plastic model kits. Here the Japanese again took the ball away from U.S. companies because of Japan’s attention to the injection molding process and the details of the components. Companies such as Tamiya are able to sell their products at a premium because the parts go together beautifully and the results are unexcelled in realism.

In fact, in smart companies, design and manufacturing engineers work as part of the same team. If you are contemplating acquiring a product assembled by the manufacturer and it shows symptoms of having been difficult to assemble, you should worry. Only dumb companies produce products that have not been designed with assembly in mind. Consumers don’t expect high-quality products from dumb companies, and there is little pride in working for an organization that is considered inferior.

Despite its importance, craftsmanship is often inadequately stressed in industry, partly because it is difficult to measure and describe in words and numbers (the usual languages of industry). Engineers and managers are much more comfortable measuring surface finish in micro-inches of deviation from the mean than in beauty. There are few courses, outside of art schools, that deal with craftsmanship and few forums and books on the subject. Many elements of craftsmanship deal with the senses and are fairly right-brained in nature. You probably own something that is beautifully crafted and value it highly. However, can you eloquently explain why? Can you explain why hand-rubbed furniture finishes are more attractive than urethane varnishes? Why hand-thrown pots are more attractive than greenware pots made in molds? Why leather is more satisfying than vinyl? What metrics would you apply to an interior paint job in your house?

The difficulty in addressing problems of craftsmanship in modern industry is due not only to communication difficulties but also to “progress.” There was a time, say 150 years ago, when a much larger percentage of the population worked with their hands. After all, the word manufacture originally meant “made by hand.” Creating something by hand is a good way to build an appreciation for craftsmanship—probably much more effective than reading books or wandering through museums. Even being closely associated with people who work with their hands is useful, an opportunity I had when I was young as a I grew up on an orange orchard in Southern California with my brother, uncle, parents, and grandparents. My grandfather had no previous experience with farming before buying the land, but he picked up the necessary skills and knowledge rapidly and by necessity. He built most of the buildings on the ranch, as well as many of the tools, machines, and pieces of furniture. My grandmother and mother sewed all their own clothes in addition to shirts and jackets for us males. Such people were my mentors.

By the time I became an engineer in the 1950s, U.S. culture had changed a great deal. The industrial surge in the United States after the Depression of the 1930s, and especially during World War II, resulted in a greatly increased supply of affordable products. People began to buy what they had formerly made and replace things they had formerly fixed. The work involved in making products, and therefore much of the appreciation for how they were made and the understanding of their function, was separated from the user. However, at the time, the work was well understood by the engineers and managers, since many of them had “come up through the ranks” and had a good sense of craftsmanship.

When I was in college, the Warner and Swasey Company in Cleveland, Ohio, made extremely high-quality machinery, and I talked with company representatives at length about possible employment. They were somewhat interested in me because of my experience in machine design and my motivation to design fine machinery. They made it plain to me, however, that if I came to work with them I would spend my first two years as a machinist, since my shop abilities were not adequate for a designer. At the time, their president and all other line managers had served their time in the shop. They recognized good work when they saw it and insisted upon it. I did not take the job they offered, but I sometimes look back and think that perhaps I missed a unique opportunity to really learn what the making of machinery was all about.

One reason I did not take the job was that even then craftsmanship occupied a relatively low status in our abstraction-loving society. We value people who talk well, use mathematics, are familiar with scientific theories, and study history and the classics. Many people value others who “work with their minds” more highly than those who can make beautiful things. Think of the difference between the pay of senior shop people and senior managers, or beginning carpenters and beginning lawyers. We tend to invite authors to our parties more than outstanding masons or sheet-metal workers (that’s probably one reason why I write books). I am afraid that we are still burdening ourselves with the outmoded social priorities of the ancient Greeks, in which the upper classes did not deal with trade or technology. In the top-ranked engineering school in which I work, most of the faculty members are familiar with advanced mathematics and the theories of science. However, only a handful of them have much of a grasp of craftsmanship. Interacting with the physical world is not their specialty. They do better in life by spending their time transferring their thoughts to publications rather than three-dimensional form.

It is still possible to find companies (usually small ones) in wood and metalworking in which the bosses are themselves extraordinary craftsmen, or at least have worked enough in the trade that they are good judges of craftsmanship. Such companies are highly prized by their customers for the quality of their work. But most customers, most managers, and even many engineers are quite divorced from the actual work of building things. Engineering education has become much more theoretical, with the result that many graduates have little background in making things and little interest in or feel for craftsmanship. More and more managers have gone through business schools and not only obtained their M.B.A. degrees but also happily accepted the belief that management is a transportable skill that can be used almost independently of one’s business. It is popularly thought now that you can manage a company that manufactures machinery even though you have spent no time designing, maintaining, or even operating the machinery. After all, management is considered to be about finance, marketing, organizational behavior, and supply chains.

Computer control has also decreased the need for highly skilled workers to the point where more and more people who work in factories are either maintenance technicians or monitor machines to make sure those machines do their job. Others are responsible for moving raw materials to the machines and then the products to the shipping point. Computers are extremely useful in the production of well-crafted objects. But unfortunately, they do only what they are told and don’t know a whole lot about craft.

Several years ago, for example, I was visiting a large automobile assembly plant in Detroit that had an interesting problem dealing with the paint line. Automobiles are painted mainly by industrial robots that are programmed by humans. The man in charge of paint quality control at this plant had previously run his own automotive painting business and had years of experience in painting cars. But he was retiring and the company was having a great deal of trouble replacing him. If you have looked for someone to paint your entire car lately (a “complete”), you may have found that there are few body shops that do so anymore and those that do charge an extremely high price. This situation has occurred partly because the United States is running out of people who have the background to do such things. We are therefore also running out of individuals who are able to supervise robots involved in such work. Robots neither have a sense of craftsmanship nor give birth to baby robots that acquire one.

In my lifetime, social values in the United States have changed so that working with one’s hands is increasingly thought to be a lesser goal. The United States has for most of the last 50 years been trying to convince itself that we are in a “new economy” that subsists on “knowledge” workers. Many people have pointed out that perhaps “white-collar” work is becoming dumbed down and the world is running short of good auto mechanics, finish carpenters, “fix-it” people, and other such highly skilled folk upon which our society depends. The traditional “vocational” schools continue to be converted to college prep, where calculus, literature, advanced placement science, and other such “upscale” topics are taught. Shop courses lose their funding, and computer programming courses take their place. Most parents want their kids to go to college and get business, law, or medical degrees even if these students might find greater fulfillment as craftspeople.

If you are interested in the role of such training at a deeper level, read a wonderful article entitled “Shop Class as Soul Craft” written by Matthew Crawford and originally included in the Summer 2006 issue of New Atlantis magazine.1 Since that time Crawford has also written a book with the same title. Incidentally, as is pointed out in the book The Millionaire Next Door by Thomas Stanley and William Danko, many millionaires in the United States these days are self-employed tradespeople.2

Modern industry is short, especially at management level, of people who have an appreciation for, and sense of, craftsmanship. You can’t place high priority on something that you don’t value, are uncomfortable with, or perhaps don’t even know exists. I have mentioned previously that the United States has lost leadership, or lost out completely, in many industrial sectors in which it used to lead the world. The excuses have ranged from “cheaper labor over there” to “government collusion” to “U.S. antibusiness policies” to “a lazy workforce.” But in some of these cases, isn’t craftsmanship perhaps a factor? Comparing Japanese and U.S. cars or machine tools in the 1980s might have given an early indication that U.S. automobile and tool companies were headed for trouble. Looking at the rapid improvement in craftsmanship in Chinese products over the past 10 years and the present rapid improvement in products from India should signal concern for the future.

If you do not grow up with a trade or craft, craftsmanship is a complex topic. It requires both left-brain and right-brain thinking, involving knowledge, sophistication, and emotion. One of the more provocative discussions of the issue is contained in a book entitled The Nature and Art of Workmanship by David Pye.3 When Pye wrote the book, he was professor of furniture design at the Royal College of Art in London. In the book he points out that there are several types of craftsmanship (or “workmanship,” as he prefers—to him craftsmanship is simply good workmanship).

Pye refers to rough, free, and regulated workmanship. Rough workmanship is oriented toward accomplishing the purpose with minimal effort, like the split-rail fence. Such products often have an honest beauty and, as he points out, are often found in rural environments but are rare in cities, despite the efforts of a few architects and interior designers. Rough workmanship is seldom adorned with decoration and usually more focused on form than surface finish. Free workmanship is more refined but is still directly affected by the individual(s) doing the work. Expert carving falls into this category. The strength and message of the piece is of more importance than geometrical perfection. In regulated workmanship, on the other hand, products are expected to be close to the defined dimensions and surfaces, and therefore highly controlled and interchangeable—the grille of an automobile or the fuselage of an airplane would be examples.

Pye also discusses the workmanship of risk as opposed to the workmanship of certainty. The workmanship of risk refers to processes in which the quality of the result is continually at risk. The individual custom furniture maker, for instance, has continuous opportunities to affect the final product. In the workmanship of certainty, the final product is preordained before production begins: it is completely designed, production tooling is manufactured and the plant assembled, then out comes the product. Free craftsmanship may be involved in the making of prototypes and the necessary tooling. Once the button is pushed, however, the effect of humans on the product is minimized. This type of workmanship is what is found in industry.

Pye does not state that one type of workmanship is better than the others. In fact, he feels that industrially made products can have the same extraordinary workmanship as handmade products. However, he is willing to say that rough and free workmanship are important to us and unlikely in products of industry. He also writes that there can be major problems in relying exclusively upon the workmanship of certainty.

Why are rough and free workmanship important to us? Pye bases his argument partly on world history, during most of which workmanship was rough while the human race made tools, implements, and shelters through individual labor for the purpose at hand. Two stone axes, two oxcarts, or even two cathedrals did not have the similarity of two 2011 Chevrolet Malibus. It is probable that attention to “perfection” of human-made objects did not begin until wealth was accumulated. Certainly by the time of the pyramids there was an emphasis toward tremendous control of materials and form. In fact, during the past 5,000 years this attention to control has continued to increase. The engraved armor of the medieval period, the jewelry and glassware of the Renaissance, the furniture of the Victorian age, the skyscrapers of the mid-20th century, and the automobiles and airplanes of today show the trend clearly—everything in its place and fewer and fewer rough edges. Pye hypothesizes that originally this geometrical perfection and regularity must have seemed almost miraculous. It also must have symbolized wealth and power, because only those with both could afford and maintain such objects in the less controlled environments of the time.

The regularity and control in industrial processes together with standardization and economies of scale are basic to our extraordinary material life. Regularity and control are also extremely satisfying to people. As Pye points out, to our forebears, nature was not especially wonderful. It contained uncomfortable levels of cold and heat, scarcities of food and water, and hostile creatures of all sizes. Control must have initially been an extremely satisfying way of defeating the enemy. I have heard other people philosophize upon similar points. In a talk he gave at Stanford, David Billington, a professor at Princeton University who has studied the aesthetic aspects of technology extensively, presented his belief that one reason for the high degree of control in the Netherlands is the hostility of nature. As the North Sea storms, the Dutch behind their dikes produce artists such as Mondrian, power plants that are laid out like Mondrian paintings, legendarily clean homes, and extraordinarily geometrical and neat fields. All of us have a need for predictability and order, even though most of us are not below sea level and the roll of significant hostile creatures has been reduced to viruses and our fellow humans. The products of modern industry satisfy this need.

However, according to Pye, these products must be carefully designed. The designer must be thoughtful in choosing materials, forms, textures, colors, and other characteristics that work together consistently when built. In the long run, wood-grained vinyl on the sides of station wagons was doomed. We interact with products from all distances and with all of our senses. A building designed by an architect may look good from afar, as it is portrayed on the drawing board. However, how about from six feet away? Is the structure boring, or do the features that please the onlooker do so independently of the distance from which we view it? Pye’s hypothesis states that the designer working on paper cannot think about the details of design in a complete enough way to provide this diversity. The craftsman, however, is sensitive to small-scale texture, smell, sound, feel, and psychological impressions. The designer who is divorced from the making of the product is limited. This limitation is reflected in many industrial products that are well made and, at first glance, appealing but in the long run turn out to be bland or dull. Controlled products must also be made well. Shiny surfaces, for example, should not end in rough edges. The more refined the design, the better the workmanship must be.

Rough workmanship, alas, is probably disappearing as industrial capability increases and people who live off the land decrease in number. Chain-link fences, barbed wire on prefabricated steel posts, and electrical fences are replacing the split rail. Recently some land not far from where I live was converted to the raising of horses, and I was amazed to see, on driving by it, that it was completely surrounded by brand-new white fencing of the type seen surrounding horse pastures for thoroughbreds. It seemed like a bit of Kentucky in the middle of the Sacramento Valley in California, and opulent beyond belief in an area that raises field crops and fruit. But upon closer inspection, the fence turned out to be plastic, and weatherproof, never to need painting. Interestingly enough, my response turned from awe to disgust. Plastic textured to look like wood, although sometimes impressively done, demeans both plastic and wood. Fake is fake. But such is the direction of our society—check out the interior of a McDonald’s.

Free workmanship is also becoming rare as the cost of labor rises and the cost of mass-produced products decreases. It is still widespread in less industrially developed countries, such as India, China, and Mexico, and practiced by makers of high-priced luxury items and industrial prototypes in developed countries. Some practices such as dentistry still employ free workmanship because of varying constraints. However, in many cases free workmanship can no longer compete economically. Even when products are created by hand, they are often copied and produced in large number through a predetermined process.

This trend in decreased free workmanship costs us not only quality but also diversity. Pye contrasts a street of parked cars with a harbor of fishing boats. Somehow the first is depressing (we build parking structures to hide them) and the second is wonderful (we build high-priced restaurants overlooking them). After spending almost all of our two million years with a great amount of diversity, we are now frantically stuffing ourselves into condominium units, which must cause a little internal trauma. We require things that fit our individual values and personalities and that are fun. The present love of funk, kitsch, antiques, and nostalgia products (such as 1960s Detroit cars) is an indication that we need more than beautifully made manufactured, mass-produced items.

The United States should offer more recognition and award to outstanding practitioners of free workmanship. Much attention has been paid to Japan’s Living National Treasures program. People are selected for this recognition because they do an outstanding job of producing artifacts consistent with Japanese cultural values. But the emphasis is on traditional craft areas such as ceramics, textiles, lacquerware, metalwork, wood and bamboo crafts, and dolls. Similar programs are now underway in countries such as Korea, the Philippines, Thailand, Romania, Australia, and France, but all oriented toward handicrafts and none overlapping industry. I know of no industry honored because of the quality of its craftsmanship. In fact, I know of no cases in which employees within industry are honored for their craftsmanship. This is shortsighted on the part of industry.

Perhaps the United States will rediscover free workmanship, designate outstanding practitioners as living national treasures, and return to teaching such things in our schools. Maybe engineers and managers will be trained to have a better appreciation for and facility in craftsmanship. Also, perhaps the increased flexibility in industry that is coming from more sophisticated computer control and more flexible approaches to manufacturing will allow more diversity in our products. As previously mentioned, craftsmanship is not a topic that is easy to debate and treat in our schools and companies, since it is quite visceral in nature and without a good vocabulary. However, craftsmanship is extremely important to people, and the issue is not likely to go away. Industry is periodically reminded that products that are well crafted simply do better in the marketplace, and they usually result in higher margins of profit.

Some motivations for outstanding craftsmanship happen regularly in industrially developed countries. The United States, for instance, does well in aerospace, where the cost of finishing parts is small compared to the overall cost of a project and craftsmanship is directly tied to function. Assembly is necessarily done carefully because of the high cost of a failure, while aerodynamics promotes nicely done finish and external detail. Interiors in upper-class compartments are very carefully detailed because airlines compete for higher-paying passengers.

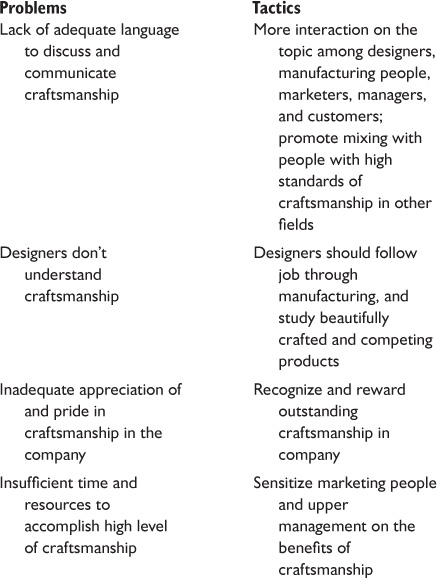

Great improvement has occurred in areas with intense competition, such as the automobile industry. But there is a great deal of room for continued improvement in all areas. There are a number of steps that can be taken to improve product craftsmanship, but they require investment of time and money. Some of them can be taken at the individual level, many at the corporate level, and some require national or even international attention. Other steps can be done through traditional education or require lifetimes of practice. Some result in lower product cost, some increase the cost. All of them dangle the inducement of higher profit margin. Let’s look at seven of these steps to improve craftsmanship that I consider highly worth exploring for the future of industry:

1. Increase awareness in business of the nature and importance of good craftsmanship in general and in the particular product. This must not only be the case with individuals responsible for defining and manufacturing the product, but broadly throughout a company. There is a saying that has been endemic in companies that have drastically improved the quality of their products: “Quality begins at the top.” When Hewlett-Packard and Ford Motor Company decided to radically improve the manufacturing quality of their products in the 1980s, John Young and Donald Petersen, who were the CEOs, made it their personal top priority. When CEOs make such a decision, people notice. Manufacturing quality was of such concern in the 1980s that companies consciously made a fetish out of it, with slogans, T-shirts, charts on the wall, and recognition dinners—such is also necessary with craftsmanship. It is possible to increase people’s sensitivity to craftsmanship through traditional courses, reverse engineering, and product reviews. Most people can learn to better recognize it. However, to produce something well crafted, there must be a company commitment to develop an acceptable language to discuss it, a system to evaluate it, and the ability to think about the many components of operations that cause it to be.

2. Ensure broad-based acceptance of responsibility for increasing the level of craftsmanship. In a product company, many people have an effect on craftsmanship, from the marketing people and designers through those who manufacture, pack, and ship the product. Everyone must take pride in the craftsmanship of the product and feel the need to perform his or her function in a way that improves it. In many cases craftsmanship can be improved with no additional expense. Sensitivity to good fits and finishes can result in alternate and sometimes less expensive approaches to production. Often, however, time and effort must be spent to improve craftsmanship. More expensive processes must be employed, and more care must be taken in manufacture and assembly. Of course, businesses do not want to spend money on such things unless they can increase the price by at least a corresponding amount.

Once “Made in the USA” signified outstanding strength, dependability, and good craftsmanship. However, as discussed, complacency caused industry to seek profits by producing large numbers of items rather than finely made ones. Only recently has the United States been competing directly with Asians and Europeans, people who make certain products very well. This competition has been good for the country. Cadillac and Lincoln used to be accepted as the U.S. luxury cars, but they have improved rapidly from confronting companies such as Mercedes, Lexus, and BMW (though they have not yet reclaimed their title on the international stage, or even in the United States). U.S. companies have done a good job of ridding the production process of inefficiency and in some cases have improved the design of products markedly. However, would you say that U.S. products are in general beautifully made? This question would not have been asked 50 years ago when the country was happily making things as U.S. companies had always made them, customers were perhaps not as sophisticated, and European and Japanese products were relatively rare.

3. Utilize a concurrent approach to engineering and a cross-functional approach to product design. Craftsmanship can be impaired by poor product integration. The product must be designed from the beginning to maximize the potential for outstanding craftsmanship. For instance, it is difficult to achieve a beautiful paint job if some of the parts are made of materials that reject the primer, or if someone’s subassembly causes a geometry that makes it impossible to coat the surface. Anyone who has painted an old car knows it is impossible to avoid drips, runs, and thin spots on them, while contemporary cars can achieve a better finish simply because they do not have strange corners and projections that cause such flaws.

4. Increase the degree of exposure and perhaps hands-on experience that give at least some people in the companies the level of sophistication that traditional craftsmen acquire. The ability to make things beautifully and appreciate fine work is learned through actually making things. People can be sensitized to the nature and importance of craftsmanship through books and lectures, but the ability to produce outstanding work must be acquired by experience—through working with the hands rather than viewing overhead slides or taking a computer course. Like any artist, the craftsman or craftswoman spends a lifetime of practice reaching the level of sophistication needed to produce and recognize the best. But industry, like schools, seems to continually want to decrease this training.

When I began working in machine shops, apprenticeships required four years. They were conducted seriously, with much effort spent to ensure that the apprentice went through the proper steps to learn the necessary skills. I was asked to do such things as file surfaces flat when a milling machine would have accomplished the same job more rapidly simply because, in the judgment of the machinists, I could not file flat enough. This sort of training was obviously not making any money for the company, but they were investing in me. When I graduated from Caltech, I joined Shell Oil Company as a production engineer. They put me directly into an oil field, first on a work-over rig, and then on a drilling rig, as the start of their hands-on training program. I rapidly learned a great deal about the craft of drilling a deep hole that was not in the field manuals. It is regrettably rare these days for companies to invest in their employees regarding instilling a sense of craftsmanship and understanding of overall production within an organization.

5. Increase recognition of outstanding work. Craftsmanship must be elevated to higher importance. One way of both encouraging awareness and motivating improvement is through recognition. Companies regularly reward outstanding salespeople, designers, researchers, and clerks. It would be interesting to witness the effects of occasionally selecting people who made outstanding contributions to craftsmanship and raising their salary to $250,000 a year or so.

6. Increase research and development intended to improve craftsmanship. Every time I look at something like a cheap kitchen knife, I realize that it could be made much more nicely with probably little increase in cost. However, the knife company likely spends little effort thinking about how to do so. A bit of investment and the formal expenditure of a few people’s time could make a huge difference. Many companies simply produce products the way they always have and have not yet been goaded into thinking how to make them better. Judging from the past 20 years’ experience in many product areas, it is better to improve craftsmanship before being goaded instead of after. One exercise I routinely assigned to engineering design students at Stanford was to have them go buy some cheap product (a dollar or two) and figure out how to improve the craftsmanship. They had no trouble succeeding, often by something as simple as removing crummy paint.

7. Increase consumer demand for better craftsmanship and then fill it. Consumers, the United States, the world, and the human race need more craftsmanship. Producers should promote increased appreciation of outstanding craftsmanship among their customers and then produce the products to satisfy the new demand they have created.

Enough about craftsmanship for now. The last chapter was about human fit. The next chapter will be about the interaction between products and human emotions. Craftsmanship has to do with both, so I will visit it again.

Chapter 5 Thought Problem

This one is a bit trickier because we have become so used to associating the word craft with handwork. But practice using it in the context of industrial production.

Choose an industrially produced product that is beautifully crafted and one that is not. You may be tempted to choose a handcrafted example, but stay with items that are produced in quantity with much of the work being done by machines. Once again, how do you account for the difference in well-crafted and not well-crafted products? To what extent is money a factor? Sensitivity? Tradition?