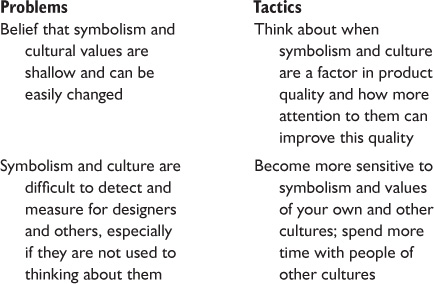

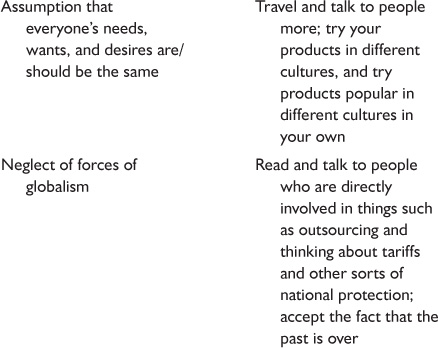

Problems and Tactics Table: Symbolism and Cultural Values

A symbol is something specific that typically stands for something more abstract. Examples might be the smiley face (happiness), the Hells Angels motorcycle patch (outlaw), the dove (peace), the diagonal bar (“do not”), or the written word. The products of industry are also symbolic. They are specific, and rightly or wrongly, we assume that they convey a message about the owner. Consider what products such as the Chevrolet Corvette, the Birkenstock sandal, the erectile dysfunction pill, the skateboard, the espresso machine, and the assault rifle say to us about their owners. Rightly or wrongly, I assume that people I see in a grocery store who bring their own bags to take their purchases home are politically liberal, sensitive to the environment, and probably neither go deer hunting nor drive a Hummer. I suggest that people who drive Volvo station wagons have a different attitude toward visceral experiences than those who drive Kawasaki Hayabusas. People shopping in REI probably like the out-of-doors and are not eligible for food stamps. Those who have neither inherited nor married money and own a personal jet probably have been quite successful in their field. People wearing highly used clothes and pushing shopping carts full of discarded objects likely do not own large estates.

The symbolism associated with individual products is partly historical, partly a function of the role they play, and partly a function of conscious effort by the producers and distributors. Some products have historically been associated with certain lifestyles. Rolls-Royces, yachts, purebred horses, and dazzling diamond jewelry have always been associated with the wealthy and their activities while scythes, plows, hammers, and, later, lunch boxes, boots, hard hats, and banged-up pickups have typically been associated with members of the working class and their travails. Products such as suits of armor, swords, assault rifles, and tanks symbolize war and violence, and strollers and baby bottles symbolize domesticity.

But aside from symbolism through history and usage, we consciously create symbolism through actions including advertising and brand building. Turn on your television or pick up a magazine and look closely at advertisements. Ads often attempt to portray a specific lifestyle by associating the product with sex appeal (clothing, cosmetics), health (pharmaceuticals), excitement (cars, motorcycles), a happy family (home products), enhanced intelligence (courses, books), entertainment (televisions, travel), or other attractive results one might presumably get from buying and using the product. Companies spend great effort and large amounts of money building a brand that will carry their products to great success. One of BMW’s slogans, “The Ultimate Driving Machine,” is a good example. It is obviously valuable for BMW to have people associate its products with both luxury and excitement—a combination that is appealing to all of us. BMW’s advertising budget for TV alone at the time of this writing is $160 million per year.1 If you think that is a lot of money, in 2010 U.S. automobile companies and dealer associations spent more than $13 billion on advertising in the United States alone.2 Much of this spending goes toward building and reinforcing the symbolism of their products.

The symbolism of products is important to us as people. Products proclaim our values and our associations. Armani suits tell the world we are successful and sophisticated, and we may wear them to work in the city with pride. Similarly, Carhartt work clothes show we work out of doors and admire well-made products, and we wear them on the farm or at a construction site with pride. We would not do nearly as well wearing an Armani suit on a construction site, or Carhartt clothes in a Wall Street office.

Producers must stay informed of their products’ symbolic nature and ensure that it matches their customers well. This prospect was perhaps easier for the United States 50 or 60 years ago, when “Made in the USA” symbolized the best, import costs were higher, and fewer countries were “developed.” But symbolism is changing over time. Because of globalization, more accessible travel, and modern communication, the United States has access to many more products, including ones that were previously symbolic of different cultural values than the ones the country had. Think of imported products that have become endemic to U.S. culture. In the United States there are espresso machines, the Camry, and chopsticks; wine from France, Australia, Chile, and most of the rest of the world is part of U.S. life; and the country has come to depend on “Made in China,” although not without a bit of ambivalence. In return, in most of the world you can find jeans, Hollywood movies, and popular U.S. music.

Products are not only symbolic of us as individuals but also of the groups with which we identify. Groups with common customs, attitudes, behaviors, institutions, and achievements are commonly referred to as cultures, and they come in many sizes. We sometimes speak of international culture (all of us) or regional cultures (Southeast Asian, North American, European, and so on). We talk about national (Chinese), state (Oaxacan), and city (Parisian) cultures and an endless number of subcultures. I sometimes refer to tribes, because the word connotes commonality of customs, interests, and a feel of belonging. Tribes can be of any size from large (Hutus, Navajos, evangelical Christians) to small (Rotary clubs, inner-city gangs, Stanford undergraduates).

Are there products that are symbolic to all humans? Certainly technology itself seems to qualify. The cell phone is becoming ubiquitous, as is the Internet. Humans are the only known life form that has technology as we define it, and our technology has always been a source of wonder and pride. Imagine the response to the wheel in a society where loads were carried on the back, the plow to people who had historically tilled fields with hand tools, the gun to those accustomed to fighting with swords, and the iron nail to those used to building with wooden pegs. Then, as now, the response was probably not immediate. New technologies are full of glitches and not only unappreciated but also resisted by experts in the old ways. When new technologies are fully born, however, we cannot help but be impressed. Think of the nuclear weapon, the transistor, the xerography process, television, the tomato harvester, GPS, computers, and cell phones. When these inventions were first presented to the public, they showed few indications of the role they would have in our lives. However, we who remember the world before them are now amazed at what they have accomplished, whether for good or evil.

Artists have always selected themes that are symbolic of the human condition, and technology has been well represented. In the cave paintings of 20,000 to 40,000 years ago, there are scenes of people using spears and bows and arrows to hunt animals (or each other). Anyone who has taken an art history course or visited a museum is aware of the products of technology that appear on Grecian or Roman pottery, in ancient friezes on buildings, on tapestries such as the Bayeux Tapestry, and in paintings. In the latter part of the 19th century and the early years of the 20th, technology and the machine were wonders.

The Crystal Palace, built for London’s Great Exhibition of 1851, and the Eiffel Tower, finished in 1889, symbolized progress by glorifying technology. Painters often sought technical themes such as railroad stations and engines (for example, Turner’s “Rain Steam and Speed,” Monet’s Gare Saint-Lazare railroad station paintings, Picasso’s “Factory in Horta de Ebbo,” Delaunay’s “Eiffel Tower,” and Russolo’s “Dynamism of an Automobile”). The Cubists were obviously affected by technological forms in their attempt to reduce their subject matter to a simple geometry. Painters such as Duchamp and Balla attempted to deal with motion in a manner similar to the camera, and Mondrian and Stella were fascinated with industrial and architectural forms. David Smith, Bruce Beasley, Jean Tinguely, and other sculptors have adopted industrial processes and materials for their work. And architects such as Renzo Piano, who designed the Centre Pompidou in Paris, have long utilized industrial products and processes as design elements.

Depictions of technology, however, have not always been a love affair. After the horrors of World War I the Dadaists emerged, who in their destructive and cynical works showed no love of capitalized industrial society and no love of technology. Interestingly, elements of this aesthetic reappeared in the 1960s in the work of such painters as Andy Warhol and Robert Rauschenberg, perhaps in reaction to the post–World War II Cold War mentality and the universally unsatisfying Korean War. But in general, art has reflected the fondness we humans have for technology.

Technology has been particularly important to the United States. Schoolroom history books extol the virtues of McCormick, Edison, and the Wright brothers. The United States was fiercely proud of the industrial capacity that swamped her enemies in World War II. The culture was fascinated by nuclear weapons and energy until many people (certainly not all) began to understand their potential for death and pollution. The country spent a large amount of money and effort to send people to the moon, and its inhabitants were extremely proud when the operation succeeded. There was little of use on the moon, and it was so remote that routine visits were not planned in the near future. Through the moon landing effort, however, technology was advanced, although the advances were bound to be oriented initially toward space travel rather than the commercial sector. The military was undoubtedly interested in the exploration of space and the moon because warriors have always liked high ground, and a quarter of a million miles is pretty high (especially for launching things toward Earth targets). The United States was also motivated to a great extent by technological competition with the Soviet Union and general technological chutzpah. Citizens loved being members of the country that placed the first man on the moon and were thrilled to realize that humans were no longer bound to Earth.

Downsides in efforts toward technological advancement existed as well, with deep disappointment caused by incidents such as the Challenger explosion and the previously mentioned Three Mile Island accident. The Challenger accident was tragic but not unexplainable. The space shuttle was an extremely advanced, complex machine, and its missions were dangerous. We in the United States did not have enough experience sending people into space that we could expect the same reliability as that of commercial air travel, and there are accidents even in that. To me, the wonder was that there had been no accidents before the Challenger. The incident let us down, though, as failures in our technology are conspicuous symbols of failures in our national ability. Three Mile Island elicited a somewhat similar experience and feeling even though no fatalities were involved. Once again, a complicated system was being operated by humans. Unfortunately, in this imperfect world, things break and people screw up. The event was a failure, however, in U.S. technology, and therefore a failure in our competency and in our self-identity.

As far as commercial products are concerned, a good example of national values can be seen in the “American” car. The United States is a large country, with good highways and widely spread snowfall in winter. Many U.S. cities have been built around the automobile. Los Angeles, for instance, although its freeways are often clogged, provides an amount of room for driving and parking that can be compared, say, to the size of Florence, Italy. The United States has also, as a petroleum producer, been committed to low-priced gasoline. As anyone who travels knows, gasoline prices in the United States have historically been approximately half what one finds in most other countries. The country’s automobiles therefore evolved into large, heavy machines that could travel extremely rapidly for long distances with a large amount of interior comfort. Crossing the Texas panhandle is best done with air conditioning, compact discs, a cooler full of food and drinks, cruise control, and lots of room to stretch and change position. Our larger cars, however, are not as useful in cramped Japanese cities, on twisty Alpine roads, or in areas where gasoline is seven dollars a gallon.

There is still a market for large, fast, powerful cars loaded with luxuries in the United States and other large, sparsely populated countries such as Canada and Mexico, and they continue to sell as prestige products in countries such as China and even Germany. In the more populated U.S. areas, smaller, nimbler cars are now becoming more attractive. In order to stay in business, U.S. automobile manufacturers have been forced to produce models that are more efficient, responsive, and economical.

House ownership has become symbolic in the United States as a major part of the “American Dream.” Over time this dream has come to include not only a house, but one with a large number of accessories, and perhaps two or more cars. As a result of these values, the United States owns more cars per person than any other country in the world. We also find the anomaly of apartment dwellers in New York City owning cars, although the city is almost completely hostile to the ownership and operation of private automobiles.

Another example of U.S. national values and the role of symbolism can be seen in the case of weapons. The United States has a long tradition of gun ownership, symbolic of “rugged individualism,” a frontier with “heroic gunfighters,” and perceived success in wars. As a result, the citizens of this country buy, sell, and own a large number of guns. Certainly these weapons are not all made in the United States, but the popularity of guns such as the Colt Single Action Army revolver (known as the Peacemaker), the Winchester lever-action rifle, and the Colt .45-caliber automatic pistol attest to the U.S. love affair with such things, symbolic of a somewhat romanticized past.

Our urge in the United States to replace labor with machinery has led us to home appliances with a high level of automatic function, symbolic of our ability to beat the age-old burden of repetitive work. U.S. kitchens boast small special-purpose devices such as Cuisinarts, bread makers, toaster ovens, mixers, blenders, espresso machines, and rice cookers, in addition to standards such as stoves, refrigerators, and microwave ovens. (A friend of mine from England amuses himself while visiting friends in the United States by counting the control buttons in their houses.)

But the United States is certainly not the only nation in which technology and the technical products of industry are symbolic of national identity and culture. Think of the hallowed historic role of the tank in Russia (which contributed to defeat of the Germans in World War II) and Russia’s present achievements in space; also the place of the sailing ship (which helped Britannia rule the seas) and the Battle of Britain fought by the Royal Air Force over England. Countries such as Germany, Switzerland, and Sweden rightfully have great pride in their ability to manufacture fine machinery. In my experience with students from Germany, France, and Japan, they seem to believe that products from their country are superior. Products are objects of national pride and reflect differences in national values in many parts of the world. This national bias also helps preserve diversity in products for all of us.

I recently ran across a paper that had accompanied a presentation on this topic given in one of my classes by a student group consisting of two graduate students from Ireland, one from Turkey, and one from Colorado. The U.S. student, as a minority, was forced to listen as his colleagues expressed disbelief at “bulky cars with fake wood on the inside” and “Californians wearing killer colors that look like they are battery powered” (a reference to clothes). Let me quote a paragraph from a paper the group wrote, since I find that we U.S. academics have been trained not to stereotype as glibly as students from different countries may:

Scandinavians regard design as the most important factor in quality, and so do the Italians. The difference in their ethic is that the Scandinavians must have products that work well both emotionally and technically, while the Italians don’t care so much. Germans emphasize functionality and performance of products in a technical hard-engineered sense. Where Germans expect a car window to go up and down a million times between failures, Italians just want the window to work when they want to ogle a bella donna. The Dutch, an economically conservative society, like products to be cheap. Our group is divided on English products. Some members believe they have a certain elegance, but no functionality or simplicity whatsoever, while others find British sports cars to be the epitome of masochistic high quality. The French are careless about environmental issues and their health, but they value products which enhance personal style.

Whether you agree or not, such stereotypes are widely held and probably have some basis on differing national values concerning industrial products.

As another example of national values expressed through technology, think of bathrooms and their fixtures in various countries: the large bathtubs of England, the water rooms of Malaysia with their troughs of water for cleansing and bathing, the bidets of France, the squat toilets and ofuros of Japan. I remember as a graduate student living in a house with four roommates, one of whom was from a country that used squat toilets. He persisted in squatting on the toilet seat with his shoes on because to him, a toilet seat used by countless others is not a pleasant thing for bodily contact. He also considered squat toilets more anatomically correct (he was right).

I broached the topic of subcultures in nations, and cultures that cross national boundaries, when discussing the emotional impact from products that allow one to associate with a particular group of people. Generally speaking, people seem to have a propensity for aligning themselves with social groups, or subcultures, rather than considering themselves to be just one of the 7 billion members of the human race. These groups have the advantage of being more workable in size and of reinforcing one’s own personal values. It is common to be a member of several such groups. One can be an American, a Southern Californian, a mother of young children, an electrician, a member of the Young Republicans, and part of a bowling team. One of the things that distinguish the members of any subculture is preference for certain industrially produced objects over others. This concept is well known to designers and marketing people, and some products are designed specifically for a given group. Skateboards are designed for the young, for example, and reclining chairs for those who seek comfort rather than visual sophistication.

You can see identification with products clearly when you consider products popular with various age groups in the United States. Senior citizens do not often drive four-wheel-drive vehicles with giant tires. However, many of them covet retirement homes that would not appeal to people in their 40s. Teenagers do not want, or care about, new Buicks, matched cooking pots, or gasoline-powered hedge clippers. Most adults don’t want “punk” clothing, unless it has been satisfactorily compromised and restated by fashion designers. Can you recall being a teenager and feeling contemptuous of all the boring stuff with which your parents complicated their life?

I still remember while in the air force being proud that all of my worldly possessions fit in the trunk of my Austin Healey. Now all my stuff expands to fill any available space. You may remember being a parent and not understanding why your kids did not seem to place any value in orderliness or why they were careless with things. At the same time, you may have noticed that your parents reached an age where they gave things away more easily and did not become as attached to possessions as you did. If you have now become one of society’s elders and have accumulated a large number of things, you might find that other issues are more important. It is quite common for elders to “lighten up” at some point.

It is interesting to watch tastes change in the United States, especially as the baby boomers age. This group consists of some 75 million people who have had a tremendous impact on U.S. consumption patterns. When they were kids, the country was very aware of toys, supportive of educational bonds, and obsessed with childbearing theory. When they became young adults, we had yuppies, an overflowing of discos and condominiums, and TV commercials and movies featuring people in their early 20s. Now we are seeing older models in clothing ads, older actresses and actors onstage, and greater emphasis on aging, health, and cosmetic surgery. The Cadillac is having a resurgence, and various types of retirement options, activities, and communities are much talked about.

Subcultures also can be defined by income and vocation. I can generalize on the consumption patterns of a number of people I know who have become well off by participating in the growth of Silicon Valley. Many of them are now presidents of companies and members or chairs of boards—so-called executives. As previously mentioned, some of them retain the trappings of the valley—jeans, bicycles, and so on—although their jeans and bicycles are more expensive than they once were. But many now tend toward the conservative taste of successful financial people: dark suits, German cars in muted colors, and perhaps a Porsche or Ferrari on the side. Their houses feature a large amount of white and marble and are meticulously ordered, not showing the ravages of use that mine does. The group tends not to own recreational vehicles, bargain furniture, or lamps made out of old kitchen pumps. They do, however, value and collect art. They tend to listen to music on new and high-quality equipment but not produce it on musical instruments. They eat and drink to moderation and are quite aware of their appearance and their health. There is a concern with apparent taste and decorum. They do not hide their wealth, but they do not flaunt it.

My friends are neither rich nor poor. Their houses are less formal than those mentioned and, in my opinion, more consistent with the business of living. There are books and magazines lying around. There are often signs of kids and grandkids. The TV sets are in plain sight and surrounded by adequate chairs and tables for beer and wine and munchies. Their furniture is more padded and less homogeneous and their housekeeping less meticulous. My wife and I are members of a subculture of people who seem to love offbeat things even though they take up space and “accomplish” very little. Even though we do not consider ourselves collectors, we constantly acquire such things. For example, we have an old dentist’s chair in the living room simply because it is fun. Our grandchildren love to give each other rides on the chair, even though some of our older guests cringe at the sight of it. But such an item is a good companion to the antique rifles, jigsaw, hedge trimmer, carpet sweeper, gravel screens, water pump, smudging torches, lead pots, log saw, pathology microscope, Southwest Indian pots, Mexican tree of life, African carvings, orchids, paintings, and sculptures in the room. Since it is our living room, we necessarily have a sofa, music equipment, a secretary desk, and several chairs and tables in it, and around Christmas, my wife adds a couple hundred crèches she has brought home from various travels. We love all the stuff in our living room so much, we carry the theme through the rest of the house.

I suppose we are members of the packrat culture, but so are many of our friends, and it is a big demographic. I recently gave a talk at a small local museum that is interested in mechanical items. The show at the time featured antique tools. At one point, I asked the audience how many of them collected things that their friends did not appreciate. Almost all of them raised their hands. I then asked how many of them had a severe problem because their house was not big enough to contain all the stuff they loved—this time all of them raised their hands. Many successful businesses support this packrat culture. Obviously, eBay is one, while other companies supply original and reproduction parts for almost any product that could be considered old and interesting.

One of my friends quietly collected and restored army tanks and musical organs. Another collected toy trains. Still another one is drawn to steam traction engines and track-laying tractors. A friend from my college days came down with such a train habit that he was led from toys to live steam to narrow gauge to concessionaire of a major tourist railway operation. His life was changed because he had a need to wander from the ordinary. Many in this “antique machine” culture restore old products and make models of them. Two of my friends construct scale 7.5-inch-gauge steam locomotives. I had an opportunity once to meet a man who was a professional ship modeler. He was at one time a physician who originally built ship models as a hobby, but he became so absorbed by it that his health was suffering from lack of sleep. His wife finally convinced him that either his medical practice or his ship modeling had to go. He gave her great credit for posing the problem in such a clear way that it was obvious he should give up medicine. When I met him, he was happily building models of yachts for wealthy owners and models for movies full-time and supporting himself by selling them. I didn’t ask if he was still married.

Products also correlate with identity in vocational groups. Construction workers buy fewer notebook computers than do business executives, and machinists and mechanics generally appreciate high-quality tools more than secretaries do. Over time, these preferred products become symbolic of the subculture. If I want to appear more like a successful business executive, I might buy a BlackBerry. When I want to appear more like a farmer, I drive my pickup, though I am of course better accepted by farmers if it is the “right” type of pickup.

As I said earlier, I have owned a pickup for many years, and I often spend time on a farm in California’s agricultural valley. In 1976, I bought a small Toyota pickup with a full-size bed and loved it greatly. However, I took quite a bit of abuse from my friends in the valley, who tended toward full-size white Fords. When my Toyota finally wore out, I bought a full-size blue Ford. I did not receive as much flack for the size and make of my pickup, but clearly the blue color confused people. I did not love the pickup as much as I had my Toyota, as it was not as much fun to drive, nor as reliable. But the new truck served me well until it too wore out. I then decided to buy a full-size Toyota pickup, but when my decision came out in a group of my friends I received such veiled disapproval that I bought a white full-size Ford instead. So, I finally had an industrial product consistent with the farmer tribe. Of course, it was not consistent with the professor tribe.

As I mentioned, one of the big tensions in the world at the time of this writing is due to rapidly increasing globalization. Such technological advances as containerized shipping, satellite and digital communication, and wide-bodied aircraft have simplified the shipping of goods, the travel of people, and the conduction of business across large distances. Products of industry are increasingly assembled from parts made in diverse locations and manufactured long distances from the ultimate consumers. China thinks this concept is wonderful. The United States likes the lower prices of Chinese products, but, as usual, we want the benefits without the costs—cheap products but a balance of payments with the world and full employment at relatively high wages. Many people think that this globalization will continue (I am one of them), although an increasing number are becoming aware of the energy costs of global business and wondering whether it is sustainable in the long run.

This globalization is making it more difficult to correlate products with countries of origin. Many products that proclaim “Made in the USA” contain components from other countries, while others are produced by a plant in another country, or even through a joint venture with a foreign company. One of the effects of globalization is increasing standardization of industrial products. Capital goods, those requiring a large investment and used by businesses in production, are becoming quite standardized. There are tremendous and increasing similarities between the machine tools, trucks, tractors, power plants, and cranes produced in the United States, Germany, Japan, and other industrialized and industrializing countries. The design of such products is heavily influenced by function, and the companies that design and manufacture them are becoming increasingly international in their operations and in their market sensitivity.

We would be surprised if a heavy-duty electrical motor manufactured in Belgium differed significantly from one manufactured in Mexico. Not only are they built for worldwide sales, but we are also becoming used to world standards not only in function and price but also in things such as material, shape, and even color palette. This trend to global standardization is not limited to high-price commercial products by any means. Athletic equipment is another example of international product uniformity. There is not much variation in tennis rackets, golf clubs, boxing gloves, or soccer balls. Some of this uniformity is standardized by rules, some of it simply has evolved into its present form through usage, but some of it is standardized by globalization. Fashion also tends to internationalize products: the present run toward jeans and athletic shoes is a good example.

There is a potential downside, however, to the quality of life in this global standardization. I do not travel overseas for enjoyment as much as I did previously, in part because airports, airlines, ground transportation, and hotels become more standardized over time with an accompanying decrease in the adventure and excitement of visiting a new and different culture. My first overseas trip was to Japan in the 1950s, and coming from the United States it was another world. Now, though strong cultural identity exists, visually the country is much more Western.

There are still countries such as India that have maintained a visual uniqueness, although they too are moving toward the prevalent Western model to cater to increasing international business and tourist travel. There is now a fine new divided toll road between Mumbai and Pune, India, a trip that I have often made. True, the travel time is cut in half and the trip is probably safer, but the new road is devoid of turned-over trucks, oxcarts, three-wheeled tractors, elephants, scooters, Austin cars, pedestrians, cattle, potholes, and other traditional features of Indian roads. To me, as a westerner, the road is less interesting. I fear that the owner-built cab on the truck in India has a limited future as well. Tata will probably soon be selling them in the United States—local purchasing agents and your basic truck-driving cowboy will not be looking for wooden cabs to festoon with totems, fringes, flowers, and other objects found decorating the cabs of the traditional trucks in India. I think there is a good chance, however, that the Indian aesthetic will remain alive—it has survived for thousands of years. A friend of mine who is president of a very successful Indian company loves watches made by Titan, an Indian company that combines traditional Indian design with a modern product. He also is fond of pointing out that successful Indian yuppie businessmen wear kurtas at parties and decorate their homes with traditional Indian crafts.

What will be the eventual price of global standardization as far as cultural diversity is concerned? Are we moving toward a shortage of products that symbolize our differences? Will we become a single global community with a single principal language and industrial products that are common to all? Business seems to be heading that way, but I don’t think all Homo sapiens will do so. In fact, the more globalization forces tend to standardize products around the world, the more market there may be for products unique to local cultures. Ten billion, six billion, or even just one billion people are still too many to have similar values, beliefs, and tastes, unless we subscribe to mass brainwashing or are lobotomized by invaders from another solar system. China tries hard for a common culture, but looking at the extreme difference between rural and urban life, the huge income gap between the rich and poor, and the lifestyles of the many people of Chinese ancestry living around the world, though a common heritage exists, it is far from homogeneous.

Although industrial products throughout the United States are perhaps not as diverse as those in India and China, they do reflect a collection of subcultures. And subcultures will remain.

As an example, as California’s population grows (now at a mere 30 million), one becomes aware of more divisions within the state and more talk of dividing the state into regions of more similar values. For many reasons this is unlikely to happen, but four regions that are quite different are Southern California (growth, entertainment, automobiles, and developers), Central California (the Sacramento and San Joaquin valleys—agriculture and newly influential cities), the San Francisco Bay region (venture capitalists, money, Priuses, and farmers’ markets), and the northern portion of the state (timber, marijuana growers, and beautiful scenery—developers not welcome). These regional differences have existed throughout my memory and have allowed Californians the pleasure of not only making rude comments and telling nasty jokes about each other but also making use of different products.

In this increasingly global world, a great deal of product diversity remains among more personal products such as food, furniture, clothing, toothpaste and toothbrushes, razors, deodorant, tampons, and underwear. Subcultures have enough choice to choose products that are consistent with their values. Grocery stores sell both organic vegetables and bacon. Some groups modify off-the-shelf products such as automobiles and computers to better fit their desires. Globalization probably means that divisions based on nations, states, and other political divides will become weaker and other groupings, such as subcultures, stronger.

Some subcultures will be heavily defined by a product: Harley-Davidson motorcycles (the big ones) might be a good example. Originally, the “cruiser” motorcycle was a typically American device. Such motorcycles are comfortable for driving long distances on straight roads. They are not as well designed for twisty roads at high speed or off-road travel through rough terrain. Because of early availability of such motorcycles and the torque and aggressive sound (especially with minimal muffler) made by their large displacement and relatively low-speed engines, they also became the motorcycle of choice for early motorcycle clubs, some of the outlaw variety. Although now most of their sales are to people who are definitely not outlaws, owners of Harley-Davidsons are a tribe. They have an annual powwow in Sturgis, South Dakota, high interest in the Harley-Davidson Company and its products, and similar values in such things as the proper clothing to wear while riding. But interestingly enough, Harley-Davidson is predicting that by 2014, some 40 percent of their sales will be overseas.3 Apparently the subculture is spreading, and undoubtedly many values of the U.S. tribe will remain intact—a global cult of people who know who Willy G. is and can tell panheads from knuckleheads is good for the company, fun for the tribe members, and fun to joke about for those of us who prefer different types of motorcycles.

The products of industry that we use say who we are. They are symbolic of our place under the sun, and the sun has been very good to us “developed” countries. We have been doing it all—financing, designing, building, selling. We like being technologically dominant in the world. But other countries want, and deserve, their slice of the pie. I think that issues such as immigration, balance of payments, intellectual property, and trade protection will become increasingly talked about in the United States. Many issues associated with industrial production, such as pollution, resource depletion, and energy and water availability, that have formerly been considered local issues, are finally being recognized by the United States as international problems. The issue of political boundaries and international versus national versus religious law will be an issue for some time to come.

In the long run, if Homo sapiens are to prosper, there is no choice but to become increasingly international in our thinking. But diversified products that are symbolic of subsets of humanity will endure. I would like to see more diversification. The ease that we have in finding fault with many products is a function of the compromises inherent in our present system of mass production. In the past 20 years, there has been much talk about more customization in products, but not much has happened. It apparently seems cheaper to convince us all to converge than to cater to the diversity in human taste. But I think we will cling to our diversity and the markets will follow.

Chapter 8 Thought Problem

Choose a subculture of which you feel a part. Choose the product that is most symbolic of this subculture. Choose the product that is most symbolic of you. Choose a product that is not at all symbolic of you.

What subculture did you choose? What three products did you choose? Why did each of these products fulfill the expressed criteria? To what extent is the product you chose that fits the subculture also symbolic of you?