The prosecution has made its case: Batman responded to the Bat Signal, apprehended the crooks, and left them for the authorities. The police showed up, rounded up the incapacitated—but not dead!—criminals, made arrests, and gathered the evidence on the scene. The district attorney took the case, filed charges, and hauled the perps, who are guilty as sin and caught red-handed, in front of the judge for their arraignment…and the judge tosses out the case as a violation of the defendants’ constitutional rights.

Huh?

Turns out that Batman and Gotham City’s finest just ran afoul of the “state actor” doctrine, one of the cornerstones of American constitutional law, and it cost them their conviction on this one. But that’s just the tip of the iceberg. Constitutional law is a broad topic, so broad, in fact, that it is usually divided into multiple law school courses. While some constitutional law issues are not important to superheroes and supervillains, 1 comic book plots raise a surprising number of constitutional issues either explicitly or implicitly. These run the gamut from wearing a costume in court, to regulating superhero abilities, to banning superheroics outright.

Before we can get into the details of constitutional law we first have to talk about what the Constitution regulates. The United States Constitution is primarily a limitation on what the government can and can’t do, not what individuals can and can’t do. In fact, the Thirteenth Amendment, which prohibits slavery, is the only constitutional provision that directly regulates conduct by private individuals. When we talk about constitutional law, then, we are talking about the exercise of government power, which is called “state action.” Anyone who is acting with government authority or at the behest of a government agent is called a “state actor.” Government employees and officials are obviously state actors when they’re on the clock, but most private individuals, including most superheroes, are not bound by the limitations imposed by the Constitution.

Superheroes that have some relationship with the government, such as agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. or the Fifty State Initiative, are state actors. But what about superheroes who work with the government but not for the government? A good example here is Batman, who sometimes works in very close cooperation with the Gotham City Police Department (GCPD), which often calls on his services via the Bat Signal or even, as in the Adam West TV series, maintains a private hotline between the Bat Cave and the police commissioner’s office. Could Batman be considered a state actor?

The Supreme Court has held that private individuals can be considered state actors under certain circumstances. The reason this is an issue is so the cops can’t get around constitutional protections by having private individuals do their dirty work for them. The basic rule of thumb is that if the cops can’t do something on their own, they can’t have someone else do it for them either. There are a few different tests, 2 but we will focus on the Lugar test: first, whether the action results from an exercise of a right or privilege having its source in state authority, and second, whether the private party can be described in all fairness as a state actor?3

As to the first part of the test, Batman sometimes acts on the suggestion of the GCPD, though he is rarely (if ever) actually ordered to do something. The Supreme Court has held that “mere approval of or acquiescence in the initiatives of a private party is not sufficient,” but state action may be found when the State “has provided such significant encouragement, either overt or covert, that the choice must in law be deemed to be that of the State.”4 In many cases it seems that Batman does what he does because he has the approval of the police. And in the other direction, it seems that the police often make decisions based on Batman’s plans (e.g., the police may wait for Batman to act before attempting an arrest).

The Supreme Court has elaborated on the second part of the test. Two relevant factors that the Court has described are (1) the extent to which the actor relies on governmental assistance and benefits and (2) whether the actor is performing a traditional governmental function.5 Batman usually relies on the GCPD to formally arrest the villains after he has caught them implicating the first factor. The second factor, whether the actor is performing a traditional government function, also argues in favor of considering Batman to be a state actor. Policing and investigation are traditional governmental functions, so by engaging in the same kind of work that the GCPD does with their cooperation and approval, Batman may be fairly described as a state actor.

Overall, the more closely Batman and other superheroes work with the police, the more likely they are to be described as state actors, which makes a certain amount of intuitive sense. There wouldn’t be much value to the Constitution if the government could do an end run around it by having private parties break the law on its behalf.

But law in the real world aside, it’s clear that Batman is not actually considered to be a state actor in the DC Universe, because if he was, then the GCPD would likely be sued into the ground by villains alleging violations of their civil rights. So why the discrepancy? As Justice Sandra Day O’Connor once said, the state action cases “have not been a model of consistency.”6 These are highly fact-specific cases, and reasonable minds can disagree on the right outcome. It’s also possible that the courts in the DC Universe have weakened the state actor doctrine somewhat to give superheroes like Batman a free hand to address the threats that the regular police can’t handle.

Hawkman takes the stand in an identity-concealing costume. Frankly, we’re surprised the judge didn’t threaten him with contempt for showing up shirtless. Marc Andreyko et al., Trial by Fire, Part 2: Witness for the Prosecution, in MANHUNTER (VOL. 3) 7 (DC Comics April 2005).

The reason all of this is important is because the Constitution imposes important limits on the government’s law enforcement activities, but these limitations apply only to state actors. There are plenty of things that the government can’t do that private individuals can, but as soon as those individuals—superheroes, say—start getting involved in things like fighting crime, we need to start asking ourselves whether they might not be subject to some of these limitations just like traditional government employees. For example, there’s no constitutional problem with superheroes wearing costumes as they go about their daily activities, but as soon as a prosecutor wants to have a masked hero testify in court, we run into Sixth Amendment problems. The Constitution does limit the state’s ability to use anonymous witnesses. Similarly, there’s no constitutional problem with a telepath reading someone’s mind for private purposes, but the Fifth Amendment creates problems for using mind reading as a source of evidence in criminal trials. The rest of the chapter is going to be devoted to issues of constitutional law that are of particular interest to superheroes and supervillains, but keep in mind that these issues are only relevant where there is a state actor involved.

With that introduction in mind, let’s delve into some issues of constitutional law that are of particular interest to superheroes and supervillains.

Superheroes must often testify in court in order to ensure the conviction of villains. Superheroes who wear identity-concealing costumes must be able to testify in costume or else risk exposing their secret identity. And here we have a constitutional problem, specifically the Confrontation Clause of the Sixth Amendment, which states that “in all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right…to be confronted with the witnesses against him.”7

The DC Universe has neatly solved this problem with its fictional version of the Twelfth Amendment.8 The DC version allows members of the Federal Authority of Registered Meta-Humans to decline to answer questions about their secret identities.9 The comics suggest that this operates similar to the Fifth Amendment protection against self-incrimination. In the Marvel Universe, a colleague of She-Hulk once sidestepped the issue by introducing a device purported to be able to establish that the person wearing Spider-Man’s costume is the “real” Spider-Man without revealing that Spider-Man is actually Peter Parker. The judge permits this, and Spider-Man takes the stand.10

The reason that particular stunt is unlikely to work is that it doesn’t address the contemporary justifications for the right to confront witnesses, primarily cross-examination and credibility judgment. Cross-examination is an essential part of the adversarial system, and requiring witnesses to be present allows the fact finder (usually the jury) to better judge the witnesses’ credibility. Further, most judges view the ability of the jury to see the witness’s face as an absolutely critical part of this process, and most would not permit any witness to testify while concealed, whether by being in a different room or wearing a mask. Because of the fundamental importance of cross-examination, the long history of the right to confront one’s accusers, and its value to criminal defendants, the Confrontation Clause enjoys strong support from both conservative and liberal judges—although that support is not universal.

The general rule of the Confrontation Clause is that “[a] witness’s testimony against a defendant is…inadmissible unless the witness appears at trial or, if the witness is unavailable, the defendant had a prior opportunity for cross-examination.”11 It is an important technical point that the clause only covers testimonial statements, but for now let’s focus on actual in-court testimony in criminal cases, to which the clause definitely applies.

But what about that “unavailability” exception? One of the main exceptions to the cross-examination requirement is if the witness is somehow “unavailable,” either because they’re dead or otherwise can’t be present for trial. Does that provide an out for superheroes? What if, for example, Spider-Man prepares a description of a villain’s activities and pins it to the villain, whom he has left hanging in a web for the police to find? Spider-Man is presumably unavailable unless he voluntarily shows up in court (and good luck serving him with a subpoena!), so could the document still be entered into evidence? The answer hinges on whether the document was “made under circumstances which would lead an objective witness reasonably to believe that the statement would be available for use at a later trial.”12 In this case, it would seem objectively reasonable to believe that Spider-Man’s description was intended for use at the villain’s trial. But note that non-testimonial evidence, such as photographs, weapons, and other physical or forensic evidence, would not run afoul of the Confrontation Clause. If superheroes stick to that kind of evidence, they can avoid a lot of headaches and tedious court appearances.

But let’s suppose that non-testimonial evidence is unavailable and the only way to put away, say, Kingpin is for Spider-Man to show up in court and testify against him (and let’s also presume this is pre–Civil War or post–Brand New Day Spider-Man and that his identity is still secret). Could Spider-Man wear his mask? And could he somehow dodge questions about his identity?

Although costumed vigilantes rarely make court appearances in the real world, the scope of the Confrontation Clause has been considered in other contexts, particularly shielding child witnesses against accused abusers from face-to-face confrontation. The Supreme Court has only rarely made exceptions to a criminal defendant’s right to confront the witnesses against him. Although the Court has “never held…that the Confrontation Clause guarantees criminal defendants the absolute right to a face-to-face meeting with witnesses against them at trial.…[A]ny exception to the right would surely be allowed only when necessary to further an important public policy.”13 In another case the Court held that “[s]o long as a trial court makes such a case-specific finding of necessity, the Confrontation Clause does not prohibit a State from using a one-way closed circuit television procedure for the receipt of testimony by a child witness in a child abuse case.”14 But on the other hand, it has also held that a screen that obscured a child witness from the view of the defendant violated the Confrontation Clause.15

But it’s important to recognize that the main tool that courts typically use to deal with these sorts of issues isn’t necessarily going to help in the case of a superhero trying to keep his identity secret. When a party wants to shield a witness for whatever reason, the judge usually conducts what’s called an “in camera review,” i.e., he brings the lawyers and the witness into his chambers and lets the party that wants the protection explain what’s going on. If we were talking about a child witness whose identity was already known, this would serve to protect the child from the defendant while still permitting the judge to be appraised of all the relevant information. But with a masked superhero, the goal is to prevent anyone from knowing the hero’s secret identity, including the judge. This amounts to asking the judge to accept the superhero’s reasoning at face value without any opportunity to investigate whether the concerns are valid. So, for example, while we know that Spider-Man has compelling reasons for wanting to keep his identity secret, a judge faced with the request wouldn’t have any actual evidence beyond Spider-Man’s assertion that he even had family at all. This is going to be a really tough sell.

An identity-concealing costume seems much closer to a screen than one-way closed-circuit television, so it may be quite difficult to argue that a superhero should be allowed to testify in costume. However, a court could make a strong case-specific finding of necessity in instances in which the superhero’s friends or family were particularly likely to be targeted for reprisal and in which the defendant had a history of retaliating against accusers. Think of how much danger Aunt May would be in if all of New York’s supervillains knew that Peter Parker was her nephew. It is also possible that allowing superheroes to do their work and present testimony in court could be considered an important public policy. It may also depend on the costume. A full mask is much closer to a screen than a mask that only covers part of the face. But the further one gets from these ideal facts the harder it will be to overcome the defendant’s strong rights under the Confrontation Clause.

Regardless, winning the right to wear a mask in court may be moot if the first question on cross-examination is “What is your real name?” And indeed this also applies to a non-masked superhero whose real identity is nonetheless unknown (e.g., Superman, though he has the “Twelfth Amendment” to rely on). Here the only option may be for the superhero to plead the Fifth Amendment, i.e., refuse to answer the question on the grounds that doing so may incriminate him or her.16 This can work for non-superhero witnesses too. Take, for example, accomplices in a bank robbery. They obviously can’t be forced to testify against themselves, but they can’t really be forced to testify against their partners either, because doing so would inherently expose them to criminal prosecution given the fact that they were involved in the crime.

This could easily be a problem for superheroes too. Batman may be able to testify that a perpetrator committed a certain crime, but by doing so he may be forced to admit that he himself was trespassing or committing various other crimes. One might understand why he might be reluctant to take the stand, and the Fifth Amendment would probably permit him to refuse to do so.

The Fifth Amendment does not require that answering a question actually directly implicate the witness in a crime, only that one could reasonably believe that it could. “[T]he privilege’s protection extends only to witnesses who have reasonable cause to apprehend danger from a direct answer.…Truthful responses of an innocent witness, as well as those of a wrongdoer, may provide the government with incriminating evidence from the speaker’s own mouth.”17 As long as the judge is satisfied that the danger of self-incrimination is not of an “imaginary and unsubstantial character,” then the superhero may decline to answer questions about his or her secret identity.18

Of course, it’s always possible for the prosecution to force immunity upon a witness, which removes the Fifth Amendment protection against self-incrimination. This would involve the district attorney’s signing an affidavit to the effect that no prosecutions would result from anything the superhero said in a given deposition or court case. Immunity cannot be refused, and once someone is immune from prosecution, the Fifth Amendment no longer applies.19 Superheroes are generally witnesses for the prosecution, so the prosecutor would have no reason to pry into the superhero’s secret identity and thus no reason to worry about imposing immunity.

It’s tempting to argue that the Fifth Amendment provides a solution to the Confrontation Clause problem. Why can’t a superhero simply assert that requiring him to reveal his identity would incriminate him, thus violating his Fifth Amendment rights? Unfortunately, the Fifth Amendment only protects a person from making self-incriminating statements, and wearing (or rather not wearing) a mask is probably not a statement for Fifth Amendment purposes. It might, however, be a form of speech for First Amendment purposes, which we discuss later in this chapter.

As we discuss in chapter 3 on evidence, using psychics (such as Professor X, the telepathic leader of the X-Men) to verify that a witness is being truthful is a complicated legal issue. In addition to the law of evidence, however, constitutional law is also relevant here, specifically the Fifth Amendment rights to be silent and not to incriminate oneself. Could the government use a psychic to extract evidence from a witness who pleads the Fifth? In order to answer that question we must first ask what the Fifth Amendment actually protects.

The Supreme Court has held that “the privilege protects a person only against being incriminated by his own compelled testimonial communications.”20 So what is a testimonial communication? The Court explained in a later case that “in order to be testimonial, an accused’s communication must itself, explicitly or implicitly, relate a factual assertion or disclose information.”21 There are many kinds of evidence that are non-testimonial and may be demanded without running afoul of the Fifth Amendment, including blood, handwriting, and even voice samples.22 Perhaps the best example of the distinction between testimonial and non-testimonial communication is that requiring a witness to turn over a key to a lockbox is non-testimonial, while requiring a witness to divulge the combination to a safe is testimonial.23

We need not wonder whether reading someone’s thoughts counts as testimonial communication, however. As the Court explained, “The expression of the contents of an individual’s mind is testimonial communication for purposes of the Fifth Amendment.”24

One might be tempted to argue that the Fifth Amendment shouldn’t apply because the testimony is the psychic’s rather than the witness’s (i.e., the difference between the witness’s saying “I saw Magneto kill Jean Grey,” and the psychic’s saying “The witness remembers seeing Magneto kill Jean Grey”). However, the Supreme Court actually addressed this issue in Estelle v. Smith.25 In that case, a defendant was subjected to a psychiatric evaluation, and the psychiatrist’s expert testimony was offered against the defendant. The Court held that the expert testimony violated the right against self-incrimination because the expert testimony was based in part on the defendant’s own statements (and omissions). Thus, using an intermediary expert witness to interpret a witness’s statements will not evade the Fifth Amendment.

So psychic powers could likely not be used to produce evidence from a witness who invoked the Fifth Amendment. And, believe it or not, this issue actually has contemporary resonance. Although a far cry from the kind of psychic powers that Professor X is capable of, technologies like functional MRI (fMRI) may someday see regular use in criminal investigation. However, scholars and commentators are divided on whether fMRI-like tests fall under the scope of the Fifth Amendment (i.e., is it more like a blood sample or like speech?).26 Time will tell whether the Fifth Amendment protects people from unwanted mind reading or not.

The Keene Act was the fictional federal law passed in the Watchmen Universe27 that prohibited “costumed adventuring” (i.e., being a superhero), with a few exceptions for superheroes that worked for the government. Would such a law be constitutional in the real-world United States? A similar analysis could be applied to similar fictional laws such as the Marvel Universe’s Superhuman Registration Act (more on that law later).

Unlike state governments, the United States Congress does not have what is called a “general police power.” Instead, its powers are specified in the Constitution, 28 and anything not specifically listed is reserved to the states and the people by the Tenth Amendment. This allocation of power between the federal and state governments is called “federalism.” The basic idea here is that while state governments can do anything the Constitution doesn’t specifically say they can’t, Congress can only do things the Constitution specifically says it can. For the Keene Act to be constitutional, there must be some justification for it in the Constitution. First, let’s consider two powers that might seem appealing but don’t quite make the cut.

The Keene Act outlawed vigilantes known as “costumed adventurers” in the Watchmen universe. Like many emergency laws, it was of questionable effectiveness. Alan Moore et al., WATCHMEN 4 (DC Comics December 1986).

Congress’s spending power, 29 which is very broad, 30 can be used to force states to pass laws that the federal government couldn’t pass itself by threatening to withhold federal funding.31 For example, the federal government does not generally have the authority to set speed limits on nonfederal highways or set the drinking age—the Twenty-First Amendment is explicit about that last one—but it can tie federal highway funding to states setting speed limits in compliance with federal guidelines.32 The spending power is general enough that it could address this issue, but the Keene Act seems to be a self-contained piece of federal legislation, not a coercive act designed to prompt action by the states. So while Congress could use the spending power to require the passage of state-level costumed adventuring bans (by, for example, threatening to withhold law enforcement funding), that doesn’t seem to be the approach used in the Watchmen Universe.

Another route to making something a federal crime is to limit it to cases in which the federal government has jurisdiction, e.g., cases involving federal land, property, or employees. But the Keene Act applied to everything, not just costumed adventuring in federal parks and the like. No, we must go big, and that means the Commerce Clause.

The Commerce Clause allows the federal government to “regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States, and with the Indian Tribes,”33 and it is the mainstay of modern congressional authority. Although it does have some limits, 34 the scope of the Commerce Clause has expanded greatly over the past century, beginning with the New Deal and continuing on through the Civil Rights era and modern federal regulations. Social Security, Medicare, most of the federal regulatory agencies, federal trademark law, and many federal civil rights and antidiscrimination laws are all founded on the Commerce Power. If anything could form the basis of the Keene Act, it’s the Commerce Clause.

In this case we’re concerned with regulation of interstate commerce (meaning, commerce “among the several States”). The Commerce Clause allows the federal government to regulate the channels of interstate commerce, the instrumentalities of interstate commerce, persons, or things in interstate commerce, and activities that substantially affect interstate commerce.35 Of these, the third is the best bet for supporting the Keene Act.

Specifically, there is an interstate market for crime prevention and investigation services (e.g., private security firms, private investigators, bounty hunters). Firms and individuals involved in this market routinely work across state lines. The Keene Act could require, for example, that anyone working in such a market do so under his or her real identity. The legitimate government interest would be the safety of consumers of such services; it is important for consumers of such services to know whom they are dealing with.

The fact that costumed adventurers sometimes provide their service for free and often without contracting with clients is of no account, as is the fact that they may work only within one state. The Commerce Clause extends to noncommercial transactions and even intrastate activities as long as doing so is necessary to make the interstate regulation effective.36 If the local or noncommercial activity affects the interstate market, the Commerce Clause can reach it.37 The existence of costumed adventurers who work for free no doubt affects the market for regular security firms, private investigators, and bounty hunters. If the aggregate impact on the market is substantial or significant, then that is enough.38 So invoking the Commerce Clause may work.

But federalism isn’t the Keene Act’s only hurdle. By prohibiting certain kinds of clothing in certain situations, the Keene Act implicates the First Amendment, which, among other things, grants the right to freedom of speech. Specifically, wearing expressive clothing has been held to be a form of speech protected by the First Amendment.39 Speech can be found where “[a]n intent to convey a particularized message was present, and the likelihood was great that the message would be understood by those who viewed it.”40 A superhero’s costume conveys the message of the identity of the wearer. There is also a First Amendment right to anonymous speech, which may protect the wearing of identity-concealing costumes, at least under certain circumstances.41

The government can regulate speech, although only under narrow circumstances. There are two major kinds of speech regulation: content-based and content-neutral. Content-based restrictions (e.g., “you can’t say that”) must be narrowly tailored to serve a compelling state interest.42 In practice, content-based restrictions are rarely upheld by federal courts. Content-neutral restrictions (e.g., “you can say that but not here, right now, or at that volume”), on the other hand, are subject to a slightly more relaxed standard. Also called “time, place, and manner restrictions,” these laws must be “justified without reference to the content of the regulated speech,…narrowly tailored to serve a significant governmental interest, and…leave open ample alternative channels for communication of the information.”43

A ban on costumed adventuring seems more like a content-neutral regulation than a content-based one. After all, the Keene Act does not ban the wearing of costumes but rather the wearing of costumes while fighting crime. The justification for the law does not depend on the content of the speech (i.e., the superhero alter ego expressed by the costume) but rather the need to be able to identify and prosecute criminals. Preventing crime is certainly a significant governmental interest, 44 and many costumed adventures in Watchmen—such as Rorschach—had become anonymous criminals, so a ban on costumed adventuring would serve to prevent crime. And the Act does not prevent alternative channels for communication of the information, such as Halloween parties or even walking down the street.

Furthermore, at least one real-life law banning the wearing of identity-concealing masks has been upheld.45 The Second Circuit—including now–Supreme Court Justice Sotomayor—noted “the Supreme Court has never held that…the right to engage in anonymous speech entails a right to conceal one’s appearance in a public demonstration. Nor has any Circuit found such a right.”46 A court could find that costumed adventuring is similar to a public demonstration, and so there is no right to anonymous crime fighting.

The Marvel Universe also has a version of an act like the Keene Act. In its 2006–2007 Civil War storyline, Congress finally passed a version of the long-rumored Superhuman Registration Act (“SHRA”). Unlike the Keene Act, the SHRA did more than ban unauthorized superheroes; it requires that superpowered individuals register with the government and, if asked, serve as a superhero on behalf of the government. Could Congress do this?

This will be the last sensible thing Tony Stark says for almost two years. Brian Michael Bendis et al., NEW AVENGERS: ILLUMINATI (Marvel Comics 2008).

The Constitution empowers Congress to “raise and support Armies,…to provide and maintain a Navy; to make Rules for the Government and Regulation of the land and naval forces.”47 In other words, Congress has the power to raise armed forces for the national defense, and there is very little limit on its powers in this area. So if, as is sometimes indicated in the comic books, the SHRA was intended to form a kind of special branch of the federal armed forces, under the auspices of S.H.I.E.L.D. or something else, Congress has a lot of authority here. It certainly has the ability to authorize and fund a superhuman branch of the military.

But does it have the ability to force superhumans to register and work for the government? Maybe. Conscription is not directly addressed by the Constitution, but it has long been held that conscription is part of Congress’s power to raise armies, and the Supreme Court tends to make unusually strong statements of congressional power when faced with this particular issue.48 As John Quincy Adams said in a speech before the House of Representatives, “[The war power] is tremendous; it is strictly constitutional; but it breaks down every barrier so anxiously erected for the protection of liberty, property and of life.”49

But while the power of Congress to draft people into the armed services is generally beyond question, the power of Congress to draft specific individuals is something different. For the most part, since World War II the draft has basically applied to all men equally. Prior to World War II, there was significant class discrimination, most exemplified by the paid substitute system of the American Civil War. But directly targeting specific individuals raises due process implications far beyond the skewed drafts of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The draft is a pretty huge imposition upon civil rights, and while it is an imposition Congress is permitted to make, the Supreme Court might balk at permitting Congress to go so far as to shed even the pretense of fairness.

The Thirteenth Amendment, which prohibits involuntary servitude, is perhaps the most obvious potential constitutional issue with the draft, but the federal courts have unanimously and consistently held that it does not limit the draft power at all: “[T]he power of Congress to raise armies by conscription is not limited by either the Thirteenth Amendment or the absence of a military emergency.”50

Similarly the federal courts have held that the First Amendment’s protection of religious belief is no barrier to the draft. Conscientious objector status is the product of statute, not the Constitution: “The conscientious objector is relieved from the obligation to bear arms in obedience to no constitutional provision, express or implied; but because, and only because, it has accorded with the policy of Congress thus to relieve him.”51 In other words, conscientious objectors don’t have to serve in the armed forces, not because the Constitution says so, but because Congress has passed a law to that effect. If Congress wanted to, it could conscript everyone, regardless of any religious or moral objection.52 It’s unlikely it would do so given that it would likely lead to civil disobedience, but it’s a theoretical possibility. The Court has listed a whole host of constitutional rights that may be superseded by the war power, culminating in “other drastic powers, wholly inadmissible in time of peace, exercised to meet the emergencies of war.”53

However, this is still an untested area of law, because as far as we can tell Congress hasn’t actually tried to do this, there being no compelling reason to use the draft power this way. The only times a draft has been imposed have been in times of incredible demand for manpower—it is a drastic step, after all—so going after a handful of specific individuals wouldn’t make sense in the real world. In the case of superheroes, however, it may well be that the courts would permit such an action, as the draft power is pretty sweeping, and the courts have not really displayed any willingness to limit that power before. If Congress thinks it needs the assistance of a uniquely capable citizen, the courts would most likely not object.

Although most superheroes and supervillains have unique origin stories, the mutants of the Marvel Universe all share a common origin: the X gene mutation. This common origin has made mutants a frequent target of discrimination in the Marvel Universe since the 1960s, sometimes at the hands of the government and sometimes at the hands of private actors. The X-Men have struggled against this discrimination in many ways, but could strategic civil rights lawsuits have prevented many of these problems? There are two major constitutional arguments that would likely be raised in a mutant rights lawsuit: equal protection and substantive due process.

The Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment states, “No State shall…deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”54 As the Supreme Court has explained,

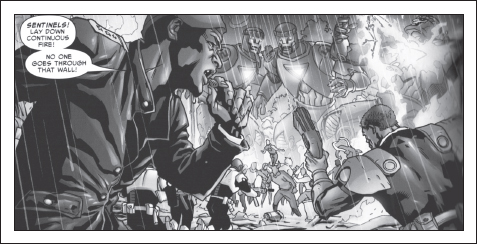

Sentinel robots are often used by the government to capture or kill mutants. David Hine et al., CIVIL WAR: X-MEN 1 (September 2006).

The general rule is that legislation is presumed to be valid and will be sustained if the classification drawn by the statute is rationally related to a legitimate state interest.…The general rule gives way, however, when a statute classifies by race, alienage, or national origin. These factors are so seldom relevant to the achievement of any legitimate state interest that laws grounded in such considerations are deemed to reflect prejudice and antipathy—a view that those in the burdened class are not as worthy or deserving as others. For these reasons and because such discrimination is unlikely to be soon rectified by legislative means, these laws are subjected to strict scrutiny and will be sustained only if they are suitably tailored to serve a compelling state interest.55

This strict scrutiny standard is the highest standard used by federal courts when evaluating legislation.

The Court has also held that other classifications (e.g., sex and legitimacy of birth) are subject to a lesser standard called intermediate scrutiny.

[W]hat differentiates sex from such nonsuspect statutes as intelligence or physical disability…is that the sex characteristic frequently bears no relation to ability to perform or contribute to society. Rather than resting on meaningful considerations, statutes distributing benefits and burdens between the sexes in different ways very likely reflect outmoded notions of the relative capabilities of men and women.…Because illegitimacy is beyond the individual’s control and bears no relation to the individual’s ability to participate in and contribute to society, official discriminations resting on that characteristic are also subject to somewhat heightened review.56

“So far, so good,” you may be thinking. After all, discrimination on the basis of mutant status is often based on “prejudice and antipathy” and unlikely to be rectified by legislative means because mutants are such a small minority. Or, at the very least, mutant status is “beyond the individual’s control and bears no relation to the individual’s ability to participate in and contribute to society,” at least inasmuch as many mutants are equal to or superior to typical humans when it comes to their ability to function as citizens.

Pixie is attacked by members of the Hellfire Cult in an example of violent anti-mutant prejudice. Matt Fraction et al., All Tomorrow’s Parties, in UNCANNY X-MEN 501 (Marvel Comics August 2008).

Alas, it is not that easy. All forms of discrimination are not created equal. Certain classifications protected by the text of the Constitution itself—race, national origin, and religion 57—are subject to “strict scrutiny,” meaning that the courts look very, very closely at anything that is even suspected to discriminate on those bases. When the courts apply strict scrutiny, they will strike down any law that is not absolutely necessary to achieve a compelling state interest and actually advances that interest. Once a court decides to apply strict scrutiny, it is almost a foregone conclusion that it will wind up striking down the law in question.

Some classifications are “quasi-suspect,” in that while the Constitution does not provide explicit protection, they are similar enough to suspect classes that the Constitution implicitly provides similar, albeit reduced, protection. Quasi-suspect classes include biological sex, citizenship status, and legitimacy of birth. 58 Discrimination on the basis of a quasi-suspect class receives what is known as “intermediate” scrutiny by the courts. Intermediate scrutiny requires that the courts strike down any laws that do not serve a compelling state interest and are at least substantially related to the interest. This is a more relaxed standard than strict scrutiny, and cases go both ways here.

But every other classification is subject to mere “rational basis” review. Here, the government just has to show that the law in question is rationally related to some state interest. The interest doesn’t have to be particularly important, and the relationship between the interest and the law doesn’t have to be particularly close. In fact, the interest in question doesn’t even have to be the one the legislature had in mind; “any conceivable rational basis” will do. 59 As one might imagine, it is very rare for the courts to strike down a law using rational basis review, but it is not unheard of. 60

Turning specifically to the question of mutation, discrimination on the basis of mutation is a relatively new phenomenon, only a few decades old, in marked contrast to discrimination on the basis of race, national origin, religion, gender, etc. 61 A court may be unwilling to conclude that legislative means of rectifying the problem will prove inadequate without giving the issue more time to develop. Second, from a legal perspective mutation could indeed bear a relation to an individual’s ability to participate in and contribute to society. For example, one could easily imagine jobs that particular mutants could do much better than a typical human. 62 Let’s continue with the Cleburne case for an example of the Supreme Court declining to grant heightened protection to a class and see if mutation fits the mold.

The Cleburne case was about discrimination against people with mental disabilities; the City of Cleburne had an ordinance that required a special zoning permit for the operation of a group home for the mentally disabled. The Fifth Circuit held that mental disability was a quasi-suspect-classification due at least some heightened scrutiny, but the Supreme Court disagreed. First, it held that mental disability was a highly variable condition requiring carefully tailored solutions not befitting the judiciary. 63 Second, it held that cities and states were addressing mental disabilities in a way that did not demonstrate antipathy or prejudice. 64 Third, the existence of specific legislation indicated that the mentally disabled were not politically powerless. 65 Fourth, if the Court recognized mental disability as a suspect class it would have to do the same for

“a variety of other groups who have perhaps immutable disabilities setting them off from others, who cannot themselves mandate the desired legislative responses, and who can claim some degree of prejudice from at least part of the public at large[, such as] the aging, the disabled, the mentally ill, and the infirm. We are reluctant to set out on that course, and we decline to do so.” 66

Some of the Court’s decision cuts in favor of mutants: Cities and states aren’t really addressing the problem and there is very little legislation on the subject to indicate mutant political power. However, other aspects cut against mutant rights. Mutation is a “highly variable condition,” and arguably it is “a difficult and often a technical matter, very much a task for legislators guided by qualified professionals and not by the perhaps ill-informed opinions of the judiciary.” 67 And making mutation a suspect class would open a door the Supreme Court explicitly declined to open in Cleburne. Given the Court’s current reluctance to embrace homosexuality as a suspect classification, 68 it’s questionable whether it would do so for mutants. Discrimination on the basis of mutation would thus likely receive only rational basis review and likely survive an Equal Protection challenge.

The second argument that might apply to mutant rights, substantive due process, is derived from the Due Process Clauses in the Fourteenth Amendment 69 (“nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law”) and Fifth Amendment 70 (“No person shall be…deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law”). While we ordinarily think of due process as being about procedural rights (e.g., the right to a hearing), substantive due process protects rights held to be “fundamental to our scheme of ordered liberty” or “deeply rooted in [American] history and traditions.” 71 An example of such rights that is relevant here are “the rights of ‘discrete and insular minorities’—groups that may face systematic barriers in the political system.” 72 When a law implicates such a right, the courts apply a strict scrutiny standard.

The courts do not recognize new substantive due process rights lightly. “Recognizing a new liberty right is a momentous step. It takes that right, to a considerable extent, outside the arena of public debate and legislative action.” 73 However,

[s]ometimes that momentous step must be taken; some fundamental aspects of personhood, dignity, and the like do not vary from State to State, and demand a baseline level of protection. But sensitivity to the interaction between the intrinsic aspects of liberty and the practical realities of contemporary society provides an important tool for guiding judicial discretion. 74

So the questions are raised: Are mutants a discrete and insular minority? Do they face systematic barriers in the political system? Do anti-mutant laws threaten fundamental aspects of personhood or dignity that demand a baseline level of protection? We think the answer to all of these questions is yes. Although anti-mutant discrimination is a relatively new phenomenon, it has existed essentially as long as mutants have. Such discrimination is pervasive, sometimes violent (remember Pixie?), and often backed by the authority of the state. In the case of Genosha (an island off the coast of Africa and thus admittedly not part of the United States) it has even lead to the wholesale enslavement of mutants. 75 This discrimination goes to the mutants’ very humanity, and there can hardly be a more fundamental aspect of personhood or dignity than that.

If mutant rights were embraced by society, could the federal or state governments pass hate crime laws that give mutants additional protections? Hate crime laws take many forms, but generally they enhance the penalty for an existing crime if the victim was chosen because of his or her race or other protected status. These kinds of laws are constitutional, as they do not punish a person for having a certain belief. Instead, the laws punish a motivation for a crime in much the same way that punishment may be enhanced when a crime was motivated by financial gain. 76 As the Supreme Court explained,

“bias-motivated crimes are more likely to provoke retaliatory crimes, inflict distinct emotional harms on their victims, and incite community unrest. The State’s desire to redress these perceived harms provides an adequate explanation for its penalty-enhancement provision over and above mere disagreement with offenders’ beliefs or biases.” 77

However, a law that targeted bias-motivated expression, such as a law prohibiting anti-mutant signs or slogans, would not be constitutional. 78 The First Amendment protects such expression, loathsome though it may be. States and cities may criminalize hate crimes but not hate speech.

The federal government is another matter altogether. As discussed, the federal government’s powers are constrained by the Constitution, and while the Commerce Clause is broad, it does have limits. The Supreme Court has held that part of the Violence Against Women Act of 1994 79 that prohibited “crimes of violence motivated by gender” was unconstitutional because it exceeded the reach of the Commerce Clause. 80 These limitations make a federal anti-mutant-hate-crime law unlikely.

Mutants may be protected from discrimination by substantive due process, but legal protection can be a double-edged sword for organizations that cater to mutants exclusively or that would like to preferentially hire people with superpowers. An example of the former would be the Xavier Institute, which is a school for, and only for, young mutants. 81 An example of the latter would be superpowered law enforcement organizations like The Fifty State Initiative and the Department of Extranormal Operations.

If the Xavier Institute is a private school that takes no public funding, then it has more leeway to discriminate, albeit with potential repercussions such as loss of its tax-exempt status. 82 If the Institute takes public funding, however, then it will generally be required not to discriminate:

The private school that closes its doors to defined groups of students on the basis of constitutionally suspect criteria manifests, by its own actions, that its educational processes are based on private belief that segregation is desirable in education. There is no reason to discriminate against students for reasons wholly unrelated to individual merit unless the artificial barriers are considered an essential part of the educational message to be communicated to the students who are admitted. Such private bias is not barred by the Constitution, nor does it invoke any sanction of laws. But neither can it call on the Constitution for material aid from the State. 83

It could be argued that mutant status is related to individual merit, and that the special curriculum of the Xavier Institute would be of little use to a nonmutant student, but that argument cuts both ways. If it is permissible for the Xavier Institute to discriminate in favor of mutants because it is a school for special students, then it would also be permissible for a regular school to discriminate against mutants because it is a school for typical students.

A more likely result is that the Xavier Institute would have to rely on private funding or open its doors to nonmutant children. Given society’s attitude towards mutants, few parents would send their nonmutant children there, especially since much of the curriculum would be of no use to them (e.g., Northstar’s flying class) and the super-genius mutants would probably wreck the grading curve for the normal classes.

S.H.I.E.L.D. and the DC Universe’s Department of Extranormal Operations (DEO) are a different story altogether. Unlike most superhero groups, S.H.I.E.L.D. is often written as a part of the United States government, and the DEO is a federal agency. Groups like the X-Men and the various instantiations of the Justice League of America are presumably private organizations that do not even employ their members, so they are free to discriminate as they wish. Private clubs can even avoid the requirements of the Americans with Disabilities Act. 84 But if S.H.I.E.L.D. or the DEO (and the United States government) want to avoid a discrimination suit, then they will have to take some precautions.

The federal government has specific rules that it must follow when employing people. These rules are part of the civil service or “merit system.” The first principle is

Recruitment should be from qualified individuals from appropriate sources in an endeavor to achieve a work force from all segments of society, and selection and advancement should be determined solely on the basis of relative ability, knowledge, and skills, after fair and open competition which assures that all receive equal opportunity. 85

As you can see, S.H.I.E.L.D. has room to prefer those with superpowers where such powers are relevant to the job (i.e., a “bona fide occupational qualification”). The problem is that superhuman abilities are not actually a requirement of being an agent of S.H.I.E.L.D. Numerous S.H.I.E.L.D. agents, although plainly very skilled, are not superhuman, at least not inherently (e.g., Nick Fury, Tony Stark, Clay Quartermain). The DEO has the same problem. This may make it difficult for S.H.I.E.L.D. or the DEO to preferentially hire people with superpowers or other unique abilities except when a position requires a particular ability (e.g., the S.H.I.E.L.D. Psi-Division).

There is an outlet, though. Not all civil service positions are covered by the merit system: “‘covered position’…does not include any position which is…excluded from the coverage of this section by the President based on a determination by the President that it is necessary and warranted by conditions of good administration.” 86 As long as the President signs off on a given position before a new agent is brought on board, S.H.I.E.L.D. is free to hire whomever it wishes.

What if the state attempted to imprison an immortal supervillain for life? Or tried to execute a nigh-invulnerable supervillain? And what about special supervillain prisons? Finally, could a supervillain’s powers be forcibly removed? Besides the practical problems involved with imprisoning an immortal, all-powerful villain like, say, Galactus, there are also constitutional issues to consider. The Eighth Amendment of the Constitution prohibits “cruel and unusual punishment.” In the examples above, how would the courts rule?

Life imprisonment appears to have emerged in the nineteenth century as an alternative to the death penalty. The Supreme Court formally recognized it as constitutional in 1974. 87 For most people, a sentence of life without parole is really just a sentence of a few decades. The issue is not limited simply to life without parole either: courts can and do hand down consecutive life sentences. A defendant convicted of multiple serious crimes that do not reach the level in which life without parole is permitted may still be sentenced to enough prison time to guarantee that he’ll never be released, e.g., six twenty-year terms to be served consecutively. He’d have to come up for and be paroled for each one in turn, which amounts to a life sentence.

But what about an immortal (or at least very long-lived) supervillain like Apocalypse? Even a very young man who gets life without parole will rarely see more than five decades in prison. Which is bad, but it’s an entirely different kettle of fish from seeing fifty decades or five hundred decades. Is this cruel and unusual punishment?

It may very well be, especially given the ongoing debate about the practice of incarceration in general. There have been cases in which judges have ordered the release of large numbers of convicts due to prison conditions, especially overcrowding. 88 But that aside, it seems plausible that the Supreme Court might well rule that imprisoning someone for centuries, in addition to being completely impractical and phenomenally expensive, is crueler than simply killing him or her. Thus, if capital punishment is unavailable as an alternative to an eternity in prison, whether because no capital crime was committed or because the jurisdiction does not allow capital punishment, then a very long but finite sentence—or at least the possibility of parole—may be constitutionally required.

While many superpowered characters are tough, most can be killed through conventional means when it comes right down to it. However, others may either be unkillable (e.g., Doomsday, Dr. Manhattan) or extremely difficult to kill (e.g., Wolverine). In the case of a character with a healing factor like Wolverine’s, none of the most common modern methods of execution would work: shooting, hanging, lethal injection, electrocution, or the gas chamber. Decapitation might work (Xavier Protocol Code 0-2-1 mentions this as a possibility for Wolverine), but no one’s tried it.

This uncertainty is problematic, because while the Supreme Court has repeatedly upheld the constitutionality of the death penalty and has never specifically invalidated a method of punishment on the grounds that it was cruel and unusual, 89 it has stated “[p]unishments are cruel when they involve torture or a lingering death.” 90 Decapitation has been specifically cited as a form of execution that is likely unconstitutional for being too painful. 91 Another hypothetical example is “a series of abortive attempts at electrocution,” which would present an “objectively intolerable risk of harm.” 92 Since we don’t know if a given method of execution would actually work for a regenerating or nigh-invulnerable supervillain, trial and error would be the only way to determine an effective method. Since regenerating characters are often unaffected by drugs, it may not be possible to mitigate pain. It seems likely, then, that the courts would rule that trying to carry out the death penalty would be unconstitutional for those who are unkillable or almost unkillable.

Letting Wolverine know you’re coming is not part of the plan. Warren Ellis et al., London Burning, in EXCALIBUR 100 (Marvel Comics August 1996).

Many supervillains could easily break out of a normal prison, so many comic books have developed special methods of incarceration to handle people who can fly or walk through walls. One example is the Marvel Universe’s Negative Zone, which housed a prison during the Marvel Civil War. Although conditions at the Negative Zone prison were similar to a normal prison, the Zone itself seemed to negatively affect some people’s emotions and mental health. Is it cruel and unusual to imprison people in such a place?

In short, probably not. Even regular prisons are seriously depressing, so it’s already going to be difficult to prove that a prison in the Negative Zone is worse enough to be considered cruel or unusual punishment. As the Supreme Court has said:

The unnecessary and wanton infliction of pain…constitutes cruel and unusual punishment forbidden by the Eighth Amendment. We have said that among unnecessary and wanton inflictions of pain are those that are totally without penological justification. In making this determination in the context of prison conditions, we must ascertain whether the officials involved acted with deliberate indifference to the inmates’ health or safety. 93

Furthermore, to be “sufficiently serious” to constitute cruel and unusual punishment, “a prison official’s act or omission must result in the denial of the minimal civilized measure of life’s necessities.” 94 Minimal is the right word; prison officials “must provide humane conditions of confinement; prison officials must ensure that inmates receive adequate food, clothing, shelter, and medical care, and must take reasonable measures to guarantee the safety of the inmates.” 95 This is a very low bar.

Not Mr. Fantastic’s finest hour. J. Michael Straczynski, Stan Lee et al., Some Words Can Never Be Taken Back, in FANTASTIC FOUR (VOL. 1) 540 (Marvel Comics November 2006).

The emotional effects of the Negative Zone are not really part of the punishment but rather a side effect of the place. Because the Negative Zone is the only suitable prison for many supervillains, the side effect is arguably necessary. Further, the side effects are not controlled or intentionally inflicted by anyone. Thus, the effects are not inflicted wantonly (i.e., deliberately and unprovoked). Offering the inmates adequate living conditions and mental health care to offset the effects of the Negative Zone could probably eliminate a charge of deliberate indifference. Finally, it would be difficult to argue that imprisonment in the Negative Zone denies the minimum civilized measure of life’s necessities. “The Constitution does not mandate comfortable prisons,” as the Farmer court noted, 96 only humane ones, and the Negative Zone is probably not bad enough to run afoul of the Eighth Amendment under the circumstances.

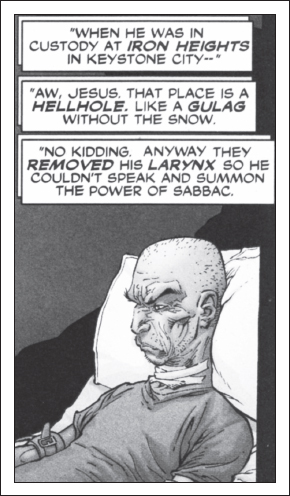

The DC supervillain Timothy Karnes had the power to transform into a demonic superbeing (Sabbac) by uttering a word of power. After being caught by Captain Marvel and transformed back into his human form, Karnes’s larynx was surgically removed in order to prevent him from turning back into Sabbac. Is this cruel and unusual?

A real-world parallel is chemical castration, where convicted sex offenders, usually pedophiles, are treated with a hormonal drug routinely used as a contraceptive in women. While it has four side effects in women, in men the drug results in a massively reduced sex drive.

About a dozen states use chemical castration in at least some cases, and there does not appear to have been a successful challenge on constitutional grounds. This may in part be due to the fact that a significant percentage of the offenders who are given the treatment volunteer for it, as it offers a way of controlling their urges. If the person being sentenced does not object, it’s hard for anyone else to come up with standing for a lawsuit. 97 Either way, despite health and civil rights concerns, this appears to be a viable sentence in the United States legal system.

The government performed an involuntary laryngectomy on Timothy Karnes in order to prevent him from summoning the power of the demon Sabbac. Judd Winick et al., Devil’s Work: Part One: Sacrifice, in OUTSIDERS (VOL. 3) 8 (DC Comics March 2004).

But it should not be hard to see that physically and permanently removing someone’s ability to speak is not exactly the same as putting a reversible (or even permanent) chemical damper on their sex drive. It’s entirely possible to live an otherwise normal life with a low sex drive, but being mute interferes with essential daily activities in a far more intrusive way. So while the idea of physical modification to the human body is not unconstitutional on its face, it remains to be seen whether this degree of modification would be permitted. For example, while chemical castration appears to be constitutional, it’s pretty likely that physical castration would not be. We can only say “pretty likely” because Buck v. Bell, a 1927 Supreme Court case that upheld (eight to one!) a Virginia statute instituting compulsory sterilization of “mental defectives,” has never been expressly overturned, and tens of thousands of compulsory sterilizations occurred in the United States after Buck, most recently in 1981. 98

On the other hand, Karnes isn’t your run-of-the-mill offender. He’s possessed by six demonic entities and capable of wreaking an immense amount of destruction. Part of the analysis in determining whether or not a punishment is cruel and unusual is whether or not the punishment is grossly disproportionate to the severity of the crime. 99 This is, in part, why the Supreme Court has outlawed the death penalty for rape cases. If the crime as such doesn’t leave anyone dead, execution seems to be a disproportionate response. 100

The Eighth Amendment also prohibits “the unnecessary and wanton infliction of pain,” including those “totally without penological justification.” 101 Here, though, there is a clear penological justification, namely the prevention of future crimes, and the laryngectomy, a routine medical procedure frequently used in those suffering from throat cancer, could be carried out in a humane manner without the infliction of unnecessary pain.

There are other criteria by which a punishment is judged, including whether it accords with human dignity and whether it is shocking or contrary to fundamental fairness. But in a case like this, necessity goes a long way, especially because the purpose of the operation is not retributive punishment but rather incapacitation. If the only way to prevent Karnes from assuming his demonic form is to render him mute, then it’s possible that the courts would go along with that, particularly if it proved impossible to contain him otherwise and the operation was carried out in a humane manner.

However, what if taking away someone’s powers could be done with no other side effects? In X-Men: The Last Stand and various stories in the comic books, someone develops a “cure” for mutation, which removes or mitigates a mutant’s powers without really affecting them in any other way. This is far more like the chemical castration situation, but unlike that, a “cure” wouldn’t even remove any functions a normal human has. It’s very unlikely that a court would recognize this as being unconstitutionally inhumane, provided their offense was serious enough to justify this rather harsh sentence.

Although some superheroes and villains have powers that are harmless or at least not directly harmful to others (e.g., invulnerability, superintelligence), many have abilities that have no or only limited uses apart from harm (e.g., Superman’s heat vision, Havok’s plasma blasts). Although the government may be limited in its ability to discriminate on the basis of mutant status or innate superpowers, could the federal government or the states regulate superpowers as weapons without running afoul of the Second Amendment?

The Supreme Court has relatively recently addressed the Second Amendment in two cases: DC v. Heller 102 and McDonald v. City of Chicago. 103 The first case dealt with the District of Columbia’s ability to regulate firearms, and (broadly speaking) the second case applied the same limits to the states via the Fourteenth Amendment. In particular, Heller held that the District of Columbia’s ban on the possession of usable handguns in the home violated the Second Amendment. From those decisions we can get a sense of how a comic book universe court might address the issue of superpowers as arms.

First, let us begin with the text of the amendment: “A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.” 104 This is a notoriously difficult sentence to interpret, but here is how the Court defined the individual terms.

“[T]he people” refers to people individually, not collectively, and not only to the subset of the people that could be a part of the militia. 105 “Arms” refers broadly to “weapons of offence, or armour of defence” and “any thing that a man wears for his defence, or takes into his hands, or useth in wrath to cast at or strike another,” and it is not limited to weapons in existence in the eighteenth century. 106 Interestingly, this suggests that defensive powers may also be protected by the Second Amendment, but for the sake of brevity we will only consider offensive powers as those are the kind most likely to be regulated.

“To keep and bear arms” means “to have weapons” and to “wear, bear, or carry…upon the person or in the clothing or in a pocket, for the purpose…of being armed and ready for offensive or defensive action in a case of conflict with another person.” 107 Taken together, the Second Amendment guarantees “the individual right to possess and carry weapons in case of confrontation,” but the right does not extend to any and all confrontations—there are limits. 108

The Court first addressed limitations established by past precedents: “the Second Amendment confers an individual right to keep and bear arms (though only arms that ‘have some reasonable relationship to the preservation or efficiency of a well regulated militia’).” 109 Further, “the Second Amendment does not protect those weapons not typically possessed by law-abiding citizens for lawful purposes, such as short-barreled shotguns.” 110

Beyond that, there are lawful limits on concealed weapons as well as “prohibitions on the possession of firearms by felons and the mentally ill, or laws forbidding the carrying of firearms in sensitive places such as schools and government buildings, or laws imposing conditions and qualifications on the commercial sale of arms.” 111 Perhaps most importantly for our purposes, there is a valid, historical limitation on “dangerous and unusual weapons.” 112

With the scope of the right established, let us now turn to whether the government could regulate superpowers under the Second Amendment.

We may start with the presumption that a superpower may be possessed and used for lawful purposes such as self-defense. The question is whether a given power fits into any of the exceptions that limit the Second Amendment right.

“Concealed Weapons”

First, many superpowers could be considered “concealed weapons.” Before the Human Torch shouts “flame on!” and activates his power, he appears to be an ordinary person. Could the government require a kind of Scarlet Letter to identify those with concealed superpowers? The answer is a qualified yes. The Constitution would not tolerate requiring innately superpowered individuals to identify themselves continuously. That would seem to violate the constitutional right to privacy and the limited right to anonymity. Furthermore, simply keeping concealed weapons is allowed (e.g., a hidden gun safe in a home). The real objection is to concealed weapons borne on the person in public.

Thus, the calculus changes when a superhero sets out to bear his or her powers against others in public (e.g., goes out to fight crime). Luckily, many superheroes already identify themselves with costumes or visible displays of power (e.g., Superman, the Human Torch). Beyond that, most states offer concealed carry permits to the public, usually after a thorough background check and safety & marksmanship training. It may well be that the Constitution requires that if a state will grant a concealed carry permit for a firearm then it must do the same for an otherwise lawful superpower.

“Typically Possessed by Law-Abiding Citizens for Lawful Purposes”

Whether this limitation encompasses a given superpower may depend on the number of superpowered individuals in a given universe and the balance of lawful superheroes to unlawful supervillains. If superpowered individuals are relatively common, which seems to be the case in the Marvel Universe, for example, and superpowered individuals are generally law-abiding and use their powers for lawful purposes, then superpowers would seem to be protected by the Second Amendment. If, on the other hand, superpowers are very unusual or if they are typically used unlawfully, then the government may be able to regulate such powers more extensively.

In most comic book universes powers are both relatively common and normally used for good, suggesting that they do not fall under this exception. However, if certain kinds of powers are more commonly associated with law breaking, then perhaps those powers in particular may be regulated, though in our experience powers of all kinds seem evenly distributed between heroes and villains.

“Dangerous and Unusual Weapons”

Here we come to the catchall. Superpowers are certainly unusual in an historical sense, 113 and they are unusual in the sense that in most comic book universes superpowered individuals are a minority. But perhaps it is the nature of the power that counts. If a superpowered individual is approximately as powerful as a normal individual with a handgun (though perhaps one with unlimited ammunition), is that really so unusual?

Wherever the line is drawn, it seems clear that at least some superpowers would qualify as dangerous or unusual weapons (e.g., Cyclops’s optic blasts, Havok’s plasma blasts). These are well beyond the power of weapons allowed even by permit, and their nature is unlike any weapon typically owned by individuals or even the police and military.

Given that some powers are likely to fall outside the protection of the Second Amendment, how could the government regulate them? We’ve already discussed the issue of concealed powers, but what about powers that fall into the other two exceptions?

The government would take a page from the way it regulates mundane firearms. First, all possessors of potentially harmful powers could be subject to a background check if they did not have the powers from birth. If they failed the background check, they could be forbidden to use the power (although use in self-defense might still be allowed by the Constitution). A registration scheme would be likely, subject to the limits discussed in reference to the Keene Act.

Second, exceptional powers could be subject to a permitting system including more thorough background checks and training requirements. Some powers could be expressly prohibited outside police or military use.

Third, superpowered individuals who have committed crimes—with or without using their powers—may be forbidden from using them or even be required to have their powers deactivated, if possible, in keeping with the Eighth Amendment issues discussed earlier. Following the decision in United States v. Comstock 114 it may even be permissible to indefinitely detain a superpowered criminal after his or her prison sentence was completed if it was not otherwise possible to prevent future criminal acts.

What about uncontrolled powers, for which merely forbidding the use isn’t enough? This probably falls outside the scope of the Second Amendment and is closer to the law of involuntary commitment. If a superpowered individual is a danger to himself or others, then he could be required to undergo de-powering treatment or be incarcerated for the individual’s protection and the protection of society.

There may be an alternative to incarceration or de-powering. In the real world, specialized drug courts offer treatment and rehabilitation rather than punishment for nonviolent offenders. “Super courts” could work with institutions like the Xavier Institute, which aims to teach mutants to control their powers and use them safely.

Thus, the Supreme Court’s current view of the Second Amendment, though politically contentious, would give superpowered individuals significant protection to keep and use their powers largely free from government regulation or interference, with some important limitations.

The 1999 Batman story arc No Man’s Land centered around a massive earthquake and fire that left Gotham City devastated. Rather than pay to rebuild the city, the federal government decided to mandate an evacuation, thereafter declaring it no longer part of the United States. The bridges to the mainland were demolished and the waters surrounding the island were mined. The result was (in theory) a legal no man’s land where survivors, criminals, die-hard police officers, and a few superheroes were left to sort through the rubble. But could the government really toss off part of a state like that?

The comic books do not clearly define the process by which Gotham was evacuated and quarantined, but we know three things for certain. First, Congress refused to grant Gotham additional federal aid (this much is certainly within congressional authority). Second, the President issued an executive order, invoking “some half-forgotten loophole about national security,” which is apparently what actually set the evacuation and quarantine in motion. Third, Congress then enacted a law that made Gotham no longer part of the United States. It’s these second and third issues that we’ll be taking a closer look at.

Isn’t Gotham City sometimes part of New Jersey? Bob Gale et al., No Law and a New Order—Part One: Values, in BATMAN: NO MAN’S LAND 1 (DC Comics March 1999).

An executive order is a formal declaration by the President, which can be made pursuant to one of two sources of authority. First, the authority can be an inherent constitutional power, such as the power to pardon. Second, the authority can be derived from a statute (i.e., a grant of power to the executive branch by the legislature). If an executive order is unconstitutional or otherwise invalid, those adversely affected by it can challenge the order. 115

So given that Congress acted after the executive order was given, what source of power could the President possibly use to justify the order to evacuate and quarantine Gotham? One possibility is the Insurrection Act, 116 which makes particular sense given that we know that the military was called in to keep order, and it was the military that eventually demolished the bridges connecting Gotham to the mainland and also mined the river and harbor.

Typically, invoking the Insurrection Act requires a request from the governor or state legislature, but we can reasonably assume that the governor of whatever state Gotham is in did so. This could arguably give the President the power to “order the insurgents to disperse” to some place other than Gotham. Ordinarily the insurgents must be ordered to “retire peaceably to their abodes within a limited time,” but it’s conceivable that the whole of Gotham was seized by eminent domain, so the insurgents’ “abodes” would no longer be in Gotham.

Invoking eminent domain would require compensating the property owners, but since the earthquake and fire drastically reduced the value of the property, the compensation would likely be significantly less than the cost of rebuilding. While it would make more sense for Congress to act first, it’s not inconceivable that the President’s actions could be more or less justified under existing law.

Here’s where we come to the sticky part. There’s no explicit constitutional provision for acquiring new territory, much less giving it up. This fact has been something of an elephant in the room ever since the Louisiana Purchase. Thomas Jefferson wanted to amend the Constitution to spell out the process for acquiring new territory, but the Purchase was pushed through without it. Various ad hoc and ex post facto justifications for acquiring new territory have since been invented, typically resting on the treaty power. The treaty power is also the mechanism by which territory can be given up (or “alienated”), which is something the United States has done several times in the twentieth century. 117

However, not all United States territory is equal. There are five different kinds of US territory: unincorporated & unorganized, unincorporated & organized, incorporated & unorganized, incorporated & organized, and states. These kinds of territory differ in how they may be alienated, but we don’t have to go into all of the details because Gotham, of course, is part of a state (traditionally New Jersey). In fact, it’s not clear how the US would go about giving up part of a state, since that has never happened before.

Making it possible to surrender part of a state would require a constitutional amendment. “The Constitution, in all its provisions, looks to an indestructible Union, composed of indestructible States.…There was no place for reconsideration, or revocation, except through revolution, or through consent of the States.” 118 If Gotham were part of an unincorporated territory (e.g., Puerto Rico), then it’s at least arguable that Congress would have the power to “deannex” it. 119 But once something becomes an incorporated part of the United States (organized or not), it’s essentially part of the United States forever. While it might be possible to evacuate and quarantine Gotham, it’s probably not possible to go so far as to declare it no longer part of the United States.

Even if the United States could give up Gotham, the remaining people living there would not cease to be United States citizens. This has an interesting side effect: Federal courts would still have jurisdiction over federal crimes committed by or against US nationals in Gotham. The United States “special maritime and territorial jurisdiction” extends to “Any place outside the jurisdiction of any nation with respect to an offense by or against a national of the United States.” 120 Because Gotham was outside the jurisdiction of any nation, the United States would actually retain jurisdiction over many crimes committed there. So much for the idea of a legal no man’s land!

1. For example, the intricacies of federal court jurisdiction rarely come up in comic books.

2. For example, the “entwinement” test set out in Brentwood Academy v. Tennessee Secondary School Athletic Ass’n, 531 U.S. 288 (2001).

3. Edmonson v. Leesville Concrete Co., Inc., 500 U.S. 614, 620 (1991). The Lugar state action test was first set forth in Lugar v. Edmonson Oil Co., 457 U.S. 922 (1982).

4. Blum v. Yaretsky, 457 U.S. 991, 1004 (1982).

5. Leesville Concrete, 500 U.S. at 621.

6. Leesville Concrete at 632 (O’Conner, J., dissenting).

7. U.S. CONST. amend. VI.

8. The real Twelfth Amendment revised the process by which the President and Vice-President are elected. Which is way less interesting.

9. The Flash v. 2 #135 (March 1998).

10. She-Hulk v. 1 #4 (August 2004).

11. Melendez-Diaz v. Massachusetts, 129 S. Ct. 2527, 2531 (2009). This “prior opportunity” is generally at the witness’s deposition.

12. Crawford v. Washington, 541 U.S. 36, 52 (2004).

13. Maryland v. Craig, 497 U.S. 836, 844–45 (1990) (quoting Coy v. Iowa, 487 U.S. 1012, 1021 (1988)).

14. Craig, 497 U.S. at 860.

15. Coy v. Iowa, 487 U.S. 1012, 1021 (1988).