Most superheroes and superhero teams don’t operate as a business or formal legal organization, but there are some notable exceptions, such as the Avengers, which has had a charter since 1982. Could a superhero team ever qualify as a real business? 1 If so, which of the alphabet soup of business organizations (LLP, LLC, Inc., etc.) would be a good fit? 2 And what about the laws and regulations that affect businesses?

The first page of the Avengers’ charter. Note section one, subsection B. We wonder if this was amended following the passage of the Superhuman Registration Act? Bob Harras et al., AVENGERS ANNIVERSARY MAGAZINE 1 (Marvel Comics November 1993).

Business associations are significantly and arguably principally concerned with minimizing two things: taxation and personal liability. Superheroes aren’t generally in it for the money, so the tax implications of their activities aren’t really so important. But all superheroes, especially ones with significant assets, should be concerned with minimizing their personal liability. The fact that the superhero team members haven’t themselves thought about how their relationship works will not stop a court from deciding if one team member might be liable for the actions of another. So if, for example, Robin assaults someone, a plaintiff might sue Robin and Batman, under the theory that they’re partners, or that Robin is Batman’s employee. That seems to make a certain amount of sense, given their relationship. But what if the situation was reversed? What if Batman assaults someone, and the plaintiff sues both of them? Does that work? To figure it out, we have to take a look at the various kinds of business relationships and entities.

The most basic kind of business entity is the sole proprietorship. Very briefly, sole proprietorships occur when a single individual goes into business for himself and doesn’t create any kind of formal business entity. When Peter Parker works as a freelance photographer without forming a business entity through filing appropriate documents with the state government, he’s effectively operating a sole proprietorship. Sole proprietors are completely and personally liable for all the debts and torts related to their business activity. What this means is that if the business goes under, all of the proprietor’s personal assets are exposed to his creditors. Any business income is treated as personal income for tax purposes. As far as superheroes go, pretty much any superhero—or supervillain—that just sets out to save/conquer the world on his own, without there being any discussion or implication of a business entity, would be treated like a sole proprietor in that there would be no distinction between his “business” activities and his personal activities. He would be fully responsible for both tax and tort liability for everything he does. Spider-Man is a good example, except when he’s working with the Avengers or the Fantastic Four, but pretty much any solo superhero/supervillain would fit.

Of course, many superheroes work together as part of a team, and that brings us naturally to partnerships. Partnerships come in several flavors, the most basic of which is a general partnership. General partnerships are basically the same as sole proprietorships except that there’s at least two people involved. A general partnership is an association of two or more people or entities to carry on a business for profit as co-owners. 3 The association is only a contractual association and can be demonstrated by a written agreement, oral agreement, conduct, or some combination of the three. 4 The parties must also intend to carry on the business as co-owners, which generally requires the parties must intend to share both the profits and control over the business, though this does not require equal sharing. 5 Finally, especially important for superhero teams, the parties must intend to make a profit, though the business does not need to actually earn any profits or income so long as it is set up with the intention of being a commercial enterprise. 6 If the parties do not intend to make a profit, such as an unincorporated nonprofit association, they cannot meet the requirements of a general partnership. 7

A general partnership is the “default” business entity, meaning it is the business organization that results where parties do not make any filings with a state electing an alternative business form. 8 All partners have equal authority to bind the partnership, and all partners—including their personal assets—are on the hook for any contract, debt, or tort related to the business and activities of the partnership. 9 One advantage of a partnership is that it enjoys what is known as “pass-through taxation.” That is, the partnership itself does not pay income tax, though it must still file an annual information return. Instead, it “passes through” any profits or losses to its partners, who then pay any required income tax. 10 Some other kinds of business entity, such as C corporations, must pay corporate income tax first in addition to the taxes paid by the employees or shareholders.

For example, the Green Lantern and Green Arrow’s association looks a lot like a general partnership, in that they seem to work largely as equals, and neither one of them is really capable of ordering the other around, at least not in terms of their joint activity. Like most superhero teams, however, they aren’t trying to make a profit, which means they definitely would not qualify as a partnership. If they wanted to form a business entity they would have to choose something else, and we’ll talk about those options later in this chapter.

Then there are limited partnerships. Unlike general partnerships, which are implied by default, limited partnerships are created by filing a certificate with the state government where the partnership wants to be registered. 11 These entities are composed of one or more general partners who are just like partners in a general partnership, and one or more limited partners. Limited partners have an ownership interest in the partnership but no control over its assets or business activities. Unlike general partners, limited partners are not liable for the debts of the partnership beyond their investment. Like general partnerships, limited partnerships must be for-profit. Taxation works the same as in other kinds of partnership. Limited partners can be employees of the partnership, and would be liable for their activities as employees just like any other employee of any other entity, but as long as the limited partners do not exercise too much control over the business, they remain immune from liability for the actions of the general partner and of the partnership as a whole. 12

Batman and Robin are iconic superhero partners, but they probably aren’t a general or even a limited partnership. Batman definitely calls the shots. He owns the Batcave, he supplies all the gear, he pays all the expenses. Robin looks for all the world like some kind of limited partner, but limited partnerships aren’t something courts are going to recognize without the proper filings, and Batman and Robin aren’t a for-profit organization in any case. Instead, a court would probably recognize some kind of employer-employee relationship between Batman and Robin. Batman would be liable both for his own actions and for those actions Robin takes on his behalf, 13 but Robin wouldn’t be liable for what Batman does, because Batman is really the one in charge.

The Fantastic Four, by contrast, are probably one of the few examples of a superhero team that could qualify as a partnership because they each have a more or less equal say in how the team is run and they actually take in money, primarily through Reed Richards’s inventions. A partnership is probably not the ideal business organization for the Fantastic Four (more on that later), but at least it’s an option.

There are other kinds of partnerships, such as limited liability partnerships (LLPs). LLPs emerged in the early 1990s in the wake of the real estate bust of the 1980s. Cascading bank failures and cratering asset prices left investors with few other options than to go after the attorneys and accountants who had helped structure the deals that had gone south. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing: someone who signs off on a deal that, in hindsight, is obviously flawed, should probably be held accountable. But what about other professionals in the partnership who had nothing to do with the transactions in question? Remember, in a general partnership, which almost all professional firms were at the time, every partner is personally liable for the actions of every other. The prospect of sending thousands of innocent professionals and their families into bankruptcy was sufficiently distasteful to encourage most state legislatures to pass acts permitting the creation of LLPs. In an LLP, there are no general partners, and each partner is only liable for his or her own wrongdoing. Like other partnerships, LLPs enjoy pass-through taxation. That is, the LLP itself does not pay income tax. Instead, the income is only taxed when partners collect it. Like limited partnerships, LLPs aren’t something a court is going to read into a liability situation.

There are also more exotic forms of partnership like limited liability limited partnerships (LLLPs), but that’s starting to get pretty far into the weeds. We turn instead to the other major kind of business entity: the corporation.

Another potential option for our heroes would be a corporation. Corporations are creatures of statute, created by filing papers as required by state incorporation laws. Every state has its own incorporation statute, but the statutes are not uniform. Some states have favorable incorporation laws and thus attract a lot of filings, historically Delaware, but more recently Nevada and a few others. Delaware has such a head start here that more than 50 percent of publicly traded companies in the U.S. are Delaware corporations. 14 But regardless of where they are created, corporations share some basic common features. First, they all offer limited liability. It is very difficult to hold the owners (i.e., shareholders), directors, officers, or employees of a corporation personally liable for the actions or debts of the corporation. Doing so is known as “piercing the corporate veil” and is very difficult to pull off in the courts. 15 The limited liability protections of limited liability partnership entities are borrowed from this corporate concept.

Many state corporation acts also provide an option for incorporating as a not-for-profit (also sometimes referred to as nonprofit) corporation. Unlike typical corporations, profits from not-for-profit corporations are not distributed to the shareholders, but are instead used by the corporation for its own purposes. The ability to operate as a not-for-profit is extremely useful for many superhero teams, most of which do not seek to earn a profit or even have income, although they may own assets such as a headquarters or vehicles. There are generally two major steps to creating a not-for-profit corporation: first, incorporating under state law and second, applying for exempt status with the Internal Revenue Service. 16

Corporations have two general options for taxation. “C” corporations are taxed “twice”: first, at the corporation income tax level and second when the profits are distributed to the shareholders as dividends. “S” corporations, named after subchapter S of the Internal Revenue Code, have “pass through” taxation like partnerships, but there are limits on ownership, including the number of shareholders and their citizenship (no foreign shareholders for S-corps). The vast majority of big publicly traded corporations are C-corps. Not-for-profit corporations, assuming they meet the requirements to qualify as a not-for-profit under federal and state laws, are exempt from federal corporate income tax and, in most states, state corporate income tax as well. Individual states and municipalities may also offer exemptions from other taxes, such as sales tax and property tax, for not-for-profit corporations.

The most frequently encountered not-for-profit corporations qualify for tax-exempt status under §501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code. To qualify as a 501(c)(3) not-for-profit entity, the corporation must be organized and operated exclusively for one of the exempt purposes listed in this section of the code: charitable, religious, educational, scientific, literary, testing for public safety, fostering national or international amateur sports competition, and preventing cruelty to children or animals. 17 “Charitable” is used in its generally accepted legal use and includes “relief of the poor, the distressed, or the underprivileged…lessening the burdens of government; lessening neighborhood tensions; eliminating prejudice and discrimination; defending human and civil rights secured by law; and combating community deterioration and juvenile delinquency.” 18 Many superhero organizations could qualify under one or more of those provisions, particularly “lessening the burdens of government” and “defending human and civil rights secured by law; and combating community deterioration and juvenile delinquency.”

However, there are important restrictions in the amount of political campaigning and legislative or lobbying activities that a 501(c)(3) not-for-profit corporation can engage in, which may be relevant to a superhero organization that opposes a law such as the Superhuman Registration Act or which opposes an anti-mutant candidate for office. We’re afraid that the finer details of nonprofit and campaign finance are beyond the scope of this book, however.

Regular corporations are not the only kind of corporate form. Limited liability companies are an increasingly popular alternative to regular corporations in many contexts. Like corporations, LLCs are defined by state statutes, and there are variations in the statutes from state to state. LLCs are a rather unique “hybrid entity,” in that they have limited personal liability like corporations, but have the option of being taxed like a corporation, a partnership (i.e., pass-through taxation), or, for single-member LLCs, the entity can be disregarded for tax purposes. Through this combination of limited personal liability and partnership taxation, and without the restrictions on membership that S-corporations have, the LLC can provide advantages unavailable to corporations, partnerships, or limited partnerships. LLCs can have a single or multiple members, and most states permit all members to participate in the management and control of the company without the member losing their limited personal liability. 19 As an alternative method of control, many state statutes also allow the LLC to appoint one or more managers to control the business of the company. 20

LLCs are also comparatively easy to set up in most states and often require fewer corporate formalities or annual filings, which makes them appealing for superheroes who are looking for a corporate structure where they do not need to publicly disclose as much information. The LLC is typically formed by filing articles of organization with the state government. 21 The owners of the company (called “members” of the LLC) can, or in some states must, create a written operating agreement that sets forth the rules governing the business, not unlike the Avengers’ charter. 22 Several states have also recently allowed the creation of low-profit or not-for-profit limited liability company statutes, which may be of particular interest to superhero organizations. 23

The question then becomes which of the above would be best suited for something like the Avengers or the Justice League?

As a first order question, we should probably ask whether our organization is going to be part of the private sector at all. Since the Civil War event in the Marvel Universe, the Avengers are organized under the auspices of the federal Fifty State Initiative and thus probably don’t need to have any kind of corporate entity. But prior to that they were a private group funded by Tony Stark through the Maria Stark Foundation, his personal not-for-profit. 24 The Justice League’s origins are a little harder to discuss with any kind of certainty due to the frequent and conflicting retcons DC has had over the past few decades, but it seems plausible that the group could have alternated between public and private at various points in its history. The Fantastic Four almost certainly have (or should have) a business organization that leases the Four’s headquarters, owns its vehicles and other assets, and takes in income and pays the team members.

Anyhow, what form are we going to choose? The heroes certainly seem to act like they’re partners much of the time, but here’s the thing: One of the biggest reasons to be a partnership rather than a corporation has to do with taxes, as corporations have a higher income tax rate than individuals. True, multinational companies are infamous for coming up with zero or even negative tax liabilities despite record-breaking profits, but you need to generate way more revenue than most of our superheroes ever do, even working together, to achieve that kind of silliness. Those sorts of manipulations involve complicated accounting practices related to expenses, capital depreciation, and shifting revenue to overseas subsidiaries, which just aren’t relevant here. Since most superhero teams have no income—and thus would pay no taxes—why not be a regular corporation? The limited liability protection would certainly be nice, right?

Well, for one thing, corporate governance is kind of a pain in the neck, which is the other reason many small businesses are partnerships or LLCs: doing anything as a corporation just involves more paperwork. It’s hard to imagine Superman and Wonder Woman sitting down in the boardroom deciding whether they, together, have enough shareholder votes to get the League to do a mission they support or whether they need to bring in someone else, maybe giving him additional control of…It’s boring just thinking about it! Luckily, comic book writers can happily gloss over those messy details.

Partnerships are significantly less formal. Partners can act independently, and if they don’t get along, hey, that’s the end of it. Each is more or less capable of taking his ball and going home, particularly when said ball doesn’t involve messy, illiquid capital investments such as a headquarters or vehicles. The problem is that most superhero groups aren’t profit-seeking organizations, which means they can’t organize as a partnership of any kind.

An LLC could suit many superhero organizations quite well. Only a few states require that LLCs be for-profit businesses, and some states even explicitly recognize not-for-profit LLCs. In a state that does not require LLCs to be for-profit, a regular LLC that isn’t trying to make a profit simply won’t get the tax benefits of being a not-for-profit. LLCs also have the advantage of being easy to set up and easier to run than corporations, but provide the similar liability protections, unlike partnerships. As a result, an LLC is a good choice for most superhero teams, especially smaller ones like the Fantastic Four and the Justice League.

The Avengers, however, are not an informal group. They own bases and vehicles, have a large operating budget, and employ numerous superheroes and regular employees. Rather than a partnership of more or less equals, like the Justice League, the Avengers have a hierarchy organized along traditional company lines. As a result, a regular corporation or LLC likely suits them best.

Of course, for some superheroes the question of involvement with a corporation is not a hypothetical one. The Fantastic Four, Bruce Wayne, and Tony Stark all have ties to companies, and this naturally raises questions about whether the superheroes’ actions could affect their respective businesses—and vice versa!

Respondeat superior (“let the master answer”) is the legal doctrine by which employers can be held accountable for the torts of their employees under certain circumstances. 25 Specifically, the employee must be acting within the scope of his or her employment. 26 “An employee acts within the scope of employment when performing work assigned by the employer or engaging in a course of conduct subject to the employer’s control. An employee’s act is not within the scope of employment when it occurs within an independent course of conduct not intended by the employee to serve any purpose of the employer.” 27 This is a very important distinction, as it makes the difference between liability and non-liability for some superheroes.

For example, while Bruce Wayne often uses Wayne Enterprises resources when fighting crime as Batman, such crime fighting isn’t work assigned by his employer or subject to his employer’s control. In fact, most Wayne Enterprises employees and shareholders are, like the general public, unaware that Bruce Wayne is Batman. And while Batman may sometimes take actions that benefit Wayne Enterprises (e.g., preventing a criminal from stealing from the company), his motivation is to fight crime in general, not to benefit his employer. Thus, Wayne Enterprises is probably not liable for Batman’s torts. Which is good, because there are a lot of them.

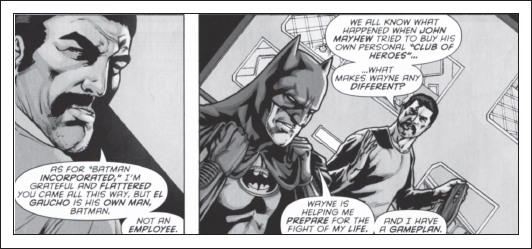

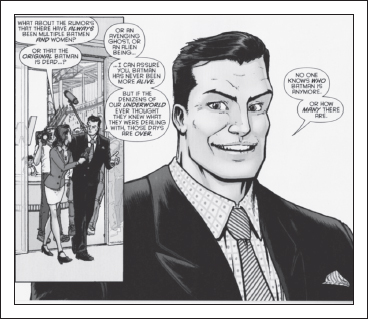

The situation is very different when one considers DC’s recent Batman Incorporated title. Batman, Inc. is a recent effort by Batman to adopt a franchise model for Batman, funding various Batmen around the United States and the rest of the world. This presents a significant liability problem because Wayne Enterprises directly and publicly funds and equips these new Batmen, although Bruce Wayne’s identity as Batman is still a secret. Since Wayne Enterprises is providing the funding, equipment, and coordination, a court would likely view the Batmen as employees rather than independent contractors. 28 As a result, Wayne Enterprises has opened itself up to potentially massive liability. A more prudent approach would have been to create a separate nonprofit organization (not owned or controlled by Wayne Enterprises) that funds the Batmen; the intermediary organization would shield Wayne Enterprises from liability. Our next example actually follows that model.

When Tony Stark works with the Avengers as Iron Man, he isn’t there as an employee of Stark Industries, 29 nor does Stark Industries fund the Avengers directly. That’s the role of the Maria Stark Foundation, which functions as a liability shield. However, because the Avengers are themselves a corporate entity of some kind, the Avengers organization may be held liable for the torts of the individual Avengers if the torts were committed within the scope of the members’ employment. But at least liability would be effectively limited to the assets of the Avengers organization (and possibly the Maria Stark Foundation) rather than potentially bankrupting all of Stark Industries.

The Fantastic Four are, like the Avengers, another example of a superhero team to which respondeat superior would likely apply. It’s not clear exactly how the Fantastic Four are organized as a business, but it is clear that there is some kind of entity that leases the Fantastic Four headquarters and collects licensing revenue from Reed Richards’s patents. When the Fantastic Four act as superheroes, they seem to do so under the auspices of that same organization. As a result, the organization could be liable for any torts they commit while on a mission.

What about liability flowing in the other direction? Could Bruce Wayne or Tony Stark be personally liable for the actions of Wayne Enterprises or Stark Industries? Although most of their wealth is probably tied up in shares of stock in their companies, both of them are independently wealthy and would make very attractive targets in a lawsuit. We noted that “piercing the corporate veil” to sue the managers or shareholders of a corporation, the partners of a limited liability partnership, or the members of an LLC is very difficult. But it’s not impossible.

Batman sets up franchises. Grant Morrison et al., Resurrector, in BATMAN INCOPORATED 2 (DC Comics February 2011); Grant Morrison et al., Scorpion Tango, in BATMAN INCORPORATED 3 (DC Comics March 2011); Grant Morrison et al., Nyktomorph, in BATMAN INCORPORATED 6 (DC Comics June 2011).

There are a few different theories under which a court will pierce the corporate veil. A common one is the “alter ego” theory, under which the corporation is a “mere extension of the individual.” 30 Some of the factors that a jury may look to when deciding if a corporation is an alter ego include

if the individual controls the corporation and conducts its business affairs without due regard for the separate corporate nature of the business; or that such separate corporate nature ceased to exist; or if the corporate assets are dealt with by the individual as if owned by the individual; or if corporate formalities are not adhered to by the corporation; or if the individual is using the corporate entity as a sham to perpetrate fraud or to avoid personal liability. 31

Luckily for our heroes, this doesn’t come up much. Both Wayne Enterprises and Stark Industries are massive, well-run conglomerates with boards of directors (and in the case of Wayne Enterprises a professional CEO). Both companies are generally good “corporate citizens” that follow the law. As a result, it would be highly unlikely for either Wayne or Stark to be personally liable for anything their respective companies did.

The situation with the Fantastic Four is a little closer cut. The company seems to consist of the Four themselves, without a lot of other employees or directors providing oversight. They also live in the company’s headquarters. As a result, the Fantastic Four will have to be careful to maintain a separate corporate existence (e.g., maintaining separate corporate accounts, signing letters and documents as corporate officers rather than individuals, properly maintaining corporate minute books).

In chapter 1, we discussed how superpowered individuals, specifically mutants, could be protected by the Constitution. But there’s more to civil rights than the Constitution. Congress and the state legislatures have also passed laws that go beyond the constitutional minimums, and many of these laws primarily regulate businesses rather than individual behavior. One of the most important of these is the Americans with Disabilities Act. 32 The ADA is particularly important because people with disabilities are not a protected class under the Constitution, so their legal protections must come from the legislature. 33 Could mutants and other people with superpowers be covered by the ADA?

The ADA defines a disability as “a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities.” 34 Perhaps equally importantly, a disability can also simply consist of “being regarded as having such an impairment.” 35 In other words, even if you aren’t actually impaired, it’s sufficient that you are discriminated against in violation of the ADA because you are regarded as being so impaired. Both of these definitions depend heavily on the meaning of phrases like “major life activity.” Luckily, the statute goes on to define those terms as well:

[M]ajor life activities include, but are not limited to, caring for oneself, performing manual tasks, seeing, hearing, eating, sleeping, walking, standing, lifting, bending, speaking, breathing, learning, reading, concentrating, thinking, communicating, and working.…[A] major life activity also includes the operation of a major bodily function.…36

Furthermore, Congress intended for all of these terms to be construed broadly:

The definition of disability in this chapter shall be construed in favor of broad coverage of individuals under this chapter, to the maximum extent permitted by the terms of this chapter.…An impairment that substantially limits one major life activity need not limit other major life activities in order to be considered a disability.…An impairment that is episodic or in remission is a disability if it would substantially limit a major life activity when active.…The determination of whether an impairment substantially limits a major life activity shall be made without regard to the ameliorative effects of mitigating measures.…37

Armed with a sense of the scope of the ADA, let’s analyze whether it might apply to superpowers.

Right off the bat, we can see that, in general, voluntarily controlled superpowers generally will not qualify as disabilities. It’s pretty hard for, say, the ability to fly to substantially limit a major life activity, especially if you can simply choose not to use it. But not all superpowers are voluntary, and whether the power is continuous (like Rogue’s involuntary life-draining power) or only poorly controlled (like Bruce Banner’s transformation into the Hulk) doesn’t matter because an episodic impairment still counts.

Before her power evolved, Rogue’s involuntary, lethal ability to drain the life out of others simply by touching them would have qualified because touching others seems like a major life activity. Certainly it is a common part of communication and many jobs (e.g., handshakes, receiving money from customers and returning change). Bruce Banner’s power definitely qualifies as it also frequently interferes with work and communication (“Hulk smash!”). Cyclops’s power may also qualify. A slightly less serious example along the same lines is Moist from Joss Whedon’s Dr. Horrible’s Sing-Along Blog, whose “power” consists of the uncontrollable production of prodigious amounts of sweat.

Ready for that shower now? Zack Whedon et al., DR. HORRIBLE AND OTHER HORRIBLE STORIES (Dark Horse September 2010).

Although Hank McCoy’s (Beast) and Kurt Wagner’s (Nightcrawler) physical appearances might not be considered outright disabilities, they may be discriminated against because they are perceived as being impaired, which fits 12102(C).

The ADA offers many legal protections to disabled individuals. In general, discrimination on the basis of disability is prohibited in employment, provision of public services, and in public accommodations and services provided by private entities. For the purposes of this chapter we will focus on employment discrimination.

The general rule against employment discrimination is this:

No [employer] shall discriminate against a qualified individual on the basis of disability in regard to job application procedures, the hiring, advancement, or discharge of employees, employee compensation, job training, and other terms, conditions, and privileges of employment. 38

Seems straightforward and complete, right? However, there are important defenses to charges of discrimination, such as when discrimination is “job-related and consistent with business necessity, and such performance cannot be accomplished by reasonable accommodation” and when a qualification standard includes “a requirement that an individual shall not pose a direct threat to the health or safety of other individuals in the workplace.” 39 Reasonable accommodation is a broad term, but it’s basically anything that isn’t an undue hardship (“an action requiring significant difficulty or expense”).

Since there are defenses, the natural question is, what can employers get away with?

Two examples of powers that can almost certainly be reasonably accommodated are Rogue’s power and Cyclops’s power. For most jobs, Rogue could simply be allowed to wear gloves and other appropriate clothing. There are very few jobs for which Rogue could not be reasonably accommodated. Similarly, Cyclops could be allowed to wear his blast-taming glasses or other appropriate headgear. He probably couldn’t be reasonably accommodated as an actor in a commercial for eyedrops or the like, but that’s about it.

Other cases are less clear. Bruce Banner would probably not be so well protected. His power would definitely raise the issue of “a direct threat to the health or safety of other individuals in the workplace.” Any work environment that involved close interaction with other employees, customers, or other sources of stress would pose a significant challenge. In many cases there simply may be no reasonable accommodation for someone who turns into an “enormous green rage monster” at the drop of a hat.

Although most superpowers are not impairments, many superpowered individuals (particularly mutants in the Marvel Universe) face discrimination despite the fact that they are not actually impaired. In addition, there are some superpowers that do impair their possessors. As a result, the ADA would protect many superpowered individuals from discrimination in several important areas of life.

Sometimes even supervillains can find themselves dealing with business law, at least on the wrong end of a lawsuit. This example from Manhunter touches on labor laws, employee class actions, and bankruptcy.

In the story, a multinational pharmaceutical/biotech/medical device company called Vesetech runs a plant in El Paso, Texas, where it employs many Mexican women who live in Ciudad Juárez across the border. While investigating the disappearances of a large number of women in the area, Kate Spencer (a.k.a. Manhunter) discovers that Vesetech was kidnapping the women and using them in unethical medical experiments. After busting up the supervillain-led research team, Spencer, who is also an attorney, announces at a press conference that she is leading a class action lawsuit against the company on behalf of the former employees.

Kate says that Vesetech pays the women “pennies,” suggesting a violation of minimum wage laws. For violations of the federal minimum wage (the same as the state minimum wage in Texas), employees can sue for both back wages and an equal amount as liquidated damages. 40 However, violations of the federal minimum wage law are frequently enforced by the Department of Labor’s Wage and Hour division, which is empowered to sue on the employee’s behalf. 41 If the Department of Labor steps in, then that terminates the employee’s right to sue on her own behalf. 42 So there’s a very good chance that part of the suit could be dismissed. But there would still be the injuries suffered by the women who were experimented on.

Kate Spencer announces her class action suit against Vesetech on national news. A good trial lawyer knows how to make good use of publicity. Marc Andreyko et al., Forgotten, Part Six: Full Circle, in MANHUNTER (VOL. 3) 36 (DC Comics January 2009).

Kate also announces that she will represent the women in a class action lawsuit, but things aren’t that simple. A judge must first certify the class, and the plaintiffs in this case may not meet the requirements. For simplicity we’ll assume that the case would be brought in federal court. Bringing a case in federal court requires (among other things) that the court have subject matter jurisdiction. That is, since the federal courts are courts of limited jurisdiction, it must be the kind of case that the federal courts can address.

In brief, federal courts can get subject matter jurisdiction three ways: the “Arising Under” clause, 43 diversity of citizenship, 44 and supplemental jurisdiction. 45 The Arising Under clause grants jurisdiction in cases involving a question of federal law. Diversity of citizenship applies when no plaintiff is a citizen of the same state as any defendant and the amount in controversy is at least $75,000. Supplemental jurisdiction allows state law issues to tag along when they are related to another claim or controversy that the court had jurisdiction over.

In this case, federal jurisdiction seems likely since the plaintiffs are all Mexican citizens, whereas the defendant is a US corporation, giving a federal court jurisdiction under diversity of citizenship. 46 There may also be federal question jurisdiction (e.g., if the women sue for wages and the Department of Labor doesn’t step in).

In any case, federal class actions are governed by Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 23. There are several requirements, 47 but the biggest issue in this case is probably commonality: Are there “questions of law or fact common to the class?” The problem is that there are at least two groups of plaintiffs: women who were paid below minimum wage and the women who were experimented on (or at least the deceased women’s estates). Admittedly, members of the latter group may also be members of the former group, but the questions of law and fact are very different between the two groups. It is possible that a federal court would consolidate the cases, but they would probably best be brought as two separate suits.

But even that may not be enough. Unless the women were subjected to at least broadly similar mistreatment at the hands of Vesetech’s “scientists” then a class action may not be the best way to resolve their claims. A court could decide that the women’s injuries are too unique to be treated as a class.

During the press conference Kate explains that data gleaned from Vesetech’s human experiments may have been used to develop a range of highly profitable and widely used products. Kate says that this is “fruit of the poisonous tree” (a rather terrible misuse of a legal phrase; read Chapter 4 on criminal procedure to learn why). Anyway, it is implied that this has something to do with the women’s case. Ordinarily the women’s damages would be what it took to compensate them (or their estates) for their injuries, plus likely punitive damages of up to ten times the compensatory damages. 48 The women would ordinarily not be entitled to any share of the ill-gotten gains derived from their suffering.

However, the equitable remedy of restitution may allow the women to recover some of those ill-gotten gains. But as an equitable remedy, restitution is discretionary, so a court may or may not impose it.

The real bad news is that Vesetech is almost certainly going to be bankrupt in short order: All of its facilities around the world were raided, virtually every aspect of its business is suspect, and it is looking at massive criminal penalties. What’s more, tort claims are general unsecured claims, a.k.a. “the back of the line” in bankruptcy. So even if the women’s case is successful, they may ultimately receive nothing as secured creditors and the government take everything the corporation owns in liquidation. Sad, but that’s the law for you.

1. We discuss only superhero teams rather than supervillains in this section because a criminal conspiracy can’t avoid liability by hiding behind a corporation. Forming an explicit organization also makes it that much easier to prosecute the organization under the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, which is often used to prosecute organized crime. That leaves tax avoidance as the major advantage to forming a business organization, and somehow we suspect that most supervillains (with some exceptions, such as Lex Luthor) aren’t too concerned with paying income tax on their loot.

2. The terms “business organization,” “business association,” and “business entity” are used interchangeably here.

3. UNIFORM PARTNERSHIP ACT § 202(a) (1997). Every state except Louisiana has adopted some version of the Uniform Partnership Act.

4. See, e.g., In re Brokers, Inc., 363 B.R. 458 (Bankr. M.D.N.C. 2007) (“A partnership may be formed without a written or oral contract. In the absence of an express contract, the existence of a partnership may be established by examining the manner in which the parties conducted business. A partnership may be created by the agreement or conduct of the parties, either express or implied.”).

5. UNIFORM PARTNERSHIP ACT § 401(b) (by default, “Each partner is entitled to an equal share of the partnership profits”) and § 401 cmt. 3 (partners may agree to share profits other than equally).

6. See, e.g., Reddington v. Thomas, 45 N.C. App. 236 (1980) (“The word ‘profit,’ as it is used in the Act relates to the purpose of the business, not to whether the business actually produced a net gain.”).

7. UNIFORM PARTNERSHIP ACT § 202(a), cmt. 2.

8. Id.

9. UNIFORM PARTNERSHIP ACT § 301, -306 (1997).

10. INTERNAL REVENUE SERV., PUBLICATION 541, PARTNERSHIPS, available at http://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/p541.pdf.

11. UNIFORM LIMITED PARTNERSHIP ACT § 201 (2001).

12. Gavin L. Phillips, Annotation, Liability of Limited Partner Arising From Taking Part in Control of Business Under Uniform Limited Partnership Act, 79 A.L.R. 4th 427 (1990).

13. See discussion of respondeat superior later in this chapter.

14. About Agency, DELAWARE DEPARTMENT OF STATE, http://corp.delaware.gov/aboutagency

.shtml (last visited Mar. 14, 2012).

15. See, e.g., Robert B. Thompson, Piercing the Corporate Veil: An Empirical Study, 76 CORNELL L. REV. 1036 (1991). Thompson studied a pool of about 1600 cases, finding that courts pierced the veil in only 40 percent of cases. In no case did a court pierce the corporate veil in a case involving a publicly held corporation. Courts applying Delaware law likewise universally declined to pierce the corporate veil. Also see John H. Matheson, Why Courts Pierce: An Empirical Study of Piercing the Corporate Veil, 7 BERKELEY BUS. L.J. 1 (2010) (finding an overall piercing rate of 31.86%).

16. There may be additional registrations with states and municipalities once a federal tax-exempt application is approved. The requirements vary by state and municipality.

17. 26 U.S.C. § 501(c)(3).

18. INTERNAL REVENUE SERV., INTERNAL REVENUE MANUAL § 7.25.3.5 (1999), available at http://www.irs.gov/irm/part7/irm_07-025-003.xhtml.

19. J. WILLIAM CALLISON AND MAUREEN A. SULLIVAN, LIMITED LIABILITY COMPANIES: A STATE-BY-STATE GUIDE TO LAW AND PRACTICE § 1:1 (2011); Id. at § 1:3.

20. Id. at § 1:3.

21. Id. at § 3:2.

22. Id. at § 3:7; See, e.g., Mo. Rev. Stat. § 347.081(1) (2004) for an example of a state statute requiring the adoption of an operating agreement.

23. Id. at § 1:1.

24. As a not-for-profit, the Maria Stark Foundation itself is likely organized as a corporation.

25. In some states, the employer can then seek indemnification from the employee (i.e., sue them). As a practical matter, however, many employees are “judgment proof” and cannot afford to pay the damages, which is one of the justifications for respondeat superior.

26. See RESTATEMENT (THIRD) OF AGENCY §§ 2.04 and 7.07(1) (2006).

27. RESTATEMENT (THIRD) OF AGENCY, §7.07(2) (2006).

28. Respondeat superior only applies to the torts of employees, not independent contractors. It is possible to sue someone for the negligent hiring of an independent contractor, but that’s harder to do than suing an employer under respondeat superior.

29. Or Stark International, Stark Enterprises, etc. The name of Stark’s company changes almost as often as his armor does.

30. Or a subsidiary corporation, but we’re concerned with individuals here, not corporate shell games.

31. Castleberry v. Branscum, 721 S.W.2d 270, 275–76 (Tex. 1986).

32. 42 U.S.C. § 12101 et seq.

33. See Cleburne v. Cleburne Living Center, 473 U.S. 432 (1985).

34. 42 U.S.C. § 12102(1)(A).

35. 42 U.S.C. § 12102(1)(C).

36. 42 U.S.C. § 12102(2)(A-B).

37. 42 U.S.C. § 12102(4)(A,C-D) and (E)(i).

38. 42 U.S.C. § 12112(a).

39. 42 U.S.C. § 12113(a, b). We’re looking at you, Mr. Banner.

40. 29 U.S.C. § 216(b).

41. 29 U.S.C. § 217.

42. 29 U.S.C. § 216(b).

43. U.S. Const., Art III § 2, cl. 1.

44. 28 U.S.C. § 1332.

45. 28 U.S.C. § 1367.

46. Legal pedantry note: It is broadly assumed that this is so, but the Supreme Court has indicated in dictum that a foreign plaintiff may not claim federal jurisdiction under diversity of citizenship. Verlinden BV v. Central Bank of Nigeria, 461 U.S. 480, 492 (1983). It is not completely clear what the answer is in a case like this, with foreign plaintiffs and a US defendant.

47. These requirements are usually referred to as numerosity (“the class is so numerous that joinder of all members is impracticable”), commonality (“there are questions of law or fact common to the class”), typicality (“the claims or defenses of the representative parties are typical of the claims or defenses of the class”), and adequacy of representation (“the representative parties will fairly and adequately protect the interests of the class”).

48. See State Farm Mut. Auto. Ins. Co. v. Campbell, 538 U.S. 408 (2003) (holding that Due Process generally requires punitive damages be less than ten times the compensatory damages).