Arromanches, with its pinwheels and seagulls, has a salty beach-town ambience that makes it a good overnight stop. For evening fun, have a drink at The Mary Celeste pub, a block from the beach on Rue Colonel René Michel.

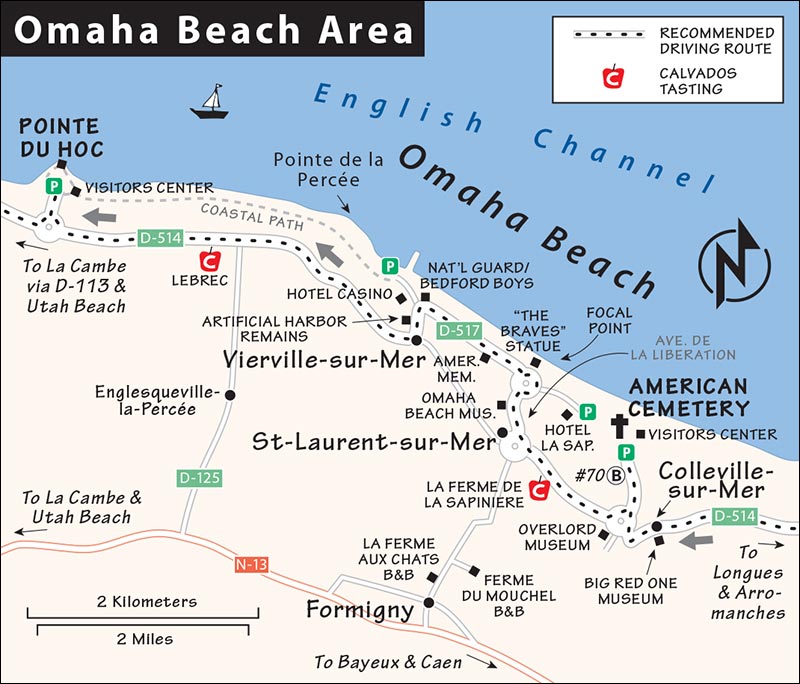

Drivers should also consider my sleeping recommendations near Omaha Beach (see “Sleeping near Omaha Beach,” later).

$$ Hotel Les Villas d’Arromanches*** has a privileged location, perched above the sea in its own park at the town’s entry, a short walk to the center. While faded on the outside, the hotel has an attractive, manor-house feel within, featuring bright and tastefully designed rooms and a handsome wine-bar lounge. Plans are afoot to attach a new building with more rooms, a spa, and a fitness room (free and easy parking, 1 Rue du Lieutenant-Colonel de Job, +33 2 31 21 38 97, www.lesvillasdarromanches.com, contact@lesvillasdarromanches.com).

$$ Hôtel de la Marine*** has a knockout location with point-blank views to the artificial harbor from most of its 33 comfortable rooms, and charming Sylvie at the reception (family rooms, elevator, good view restaurant, Quai du Canada, +33 2 31 22 34 19, www.hotel-de-la-marine.fr, hotel.de.la.marine@wanadoo.fr).

$ Hôtel d’Arromanches,** on the main pedestrian drag near the TI, is a good value, with nine small, straightforward rooms (some with water views), all up a tight stairway that feels like a tree house. Here you’ll find the cheery, recommended Restaurant “Le Pappagall” run by English-speaking Luis (2 Rue Colonel René Michel, +33 2 31 22 36 26, www.hoteldarromanches.fr, reservation@hoteldarromanches.fr).

$ L’Hôtel Ideal de Mountbatten,*** located a long block up from the water, is a 12-room, two-story, motel-esque place with generously sized, stylish, clean, and good-value lodgings—and welcoming owners Sylvie and Laurent (family rooms, reception closed 14:00-16:00, easy parking—free when you book direct, short block below the main post office at 20 Boulevard Gilbert Longuet, +33 2 31 22 59 70, www.hotelarromancheslideal.fr, contact@hotelarromancheslideal.fr).

For locations, see the “D-Day Beaches” map on here.

$$ Ferme de la Rançonnière is a 35-room, country-classy oasis buried in farmland a 15-minute drive from Bayeux or Arromanches. It’s flawlessly maintained, from its wood-beamed, stone-walled rooms to its traditional restaurant (good menu options) and fireplace-cozy lounge/bar (family rooms, bike rental, service-oriented staff, 4.5 miles southeast of Arromanches in Crépon, +33 2 31 22 21 73, www.ranconniere.fr, info@ranconniere.fr).

The same family has two other properties nearby: The $$ Manoir de Mathan has 21 similarly traditional but bigger rooms a few blocks away in the same village (comparable prices to main building, Route de Bayeux, Crépon). An eight-minute drive away, in the village of Asnelles, are seven slick, glassy, modern seaside $$ apartments right along the beachfront promenade (2 Impasse de l’Horizon, www.gites-en-normandie.eu). For any of these, check in at the main hotel. Book directly so they can help you choose the property and room that works best for you.

$ La Ferme de la Gronde lies midpoint between Bayeux and Arromanches with five large traditional rooms in a big stone farmhouse overlooking wheat fields and lots of grass, with outdoor tables (includes breakfast, 2 big comfortable apartments ideal for families, well-signed from D-516 on Route de l’Eglise in Magny-en-Bessin, +33 2 31 21 33 11, www.chambres-gite-normandie.fr, info@chambres-gite-normandie.fr).

At ¢ André and Madeleine Sebire’s B&B, you’ll experience a real Norman farm. The hardworking owners offer four modest, homey, and dirt-cheap rooms in the middle of nowhere (includes breakfast, 2 miles from Arromanches in the tiny Ryes at Ferme du Clos Neuf, +33 2 31 22 32 34, emmanuelle.sebire@wanadoo.fr, little English spoken). Follow signs into Ryes, then go down Rue de la Forge (kitty-corner from the restaurant). Turn right just after the small bridge, onto Rue Tringale, and go a half-mile to a sign on the right to Le Clos Neuf. Park near the tractors.

You’ll find cafés, crêperies, and shops selling sandwiches to go (ideal for beachfront picnics). The bakery next to the recommended Arromanches Militaria store makes good sandwiches, quiches, and tasty pastries. Many restaurants line Rue Maréchal Joffe, the bustling pedestrian zone a block inland. The following restaurants at recommended hotels are also reliable:

$$ Restaurant “Le Pappagall” serves basic café fare in a cheery setting (daily in high season, closed Wed and possibly other days off-season, Hôtel d’Arromanches).

$$ Hôtel de la Marine allows you to dine or drink in style—and with good quality cuisine—right on the water (ideal outdoor seating for a drink in nice weather, daily).

From Arromanches by Bus to: Bayeux (bus #74/#75, 5/day in summer; 3/day Mon-Sat and none on Sun in off-season), Juno Beach (bus #74/#75, 20 minutes, www.nomadcar14.fr). The bus stop is near the main post office, four long blocks above the sea (the stop for Bayeux is on the sea side of the street; the stop for Juno Beach is on the post office side).

The American sector, stretching west of Arromanches, is divided between Omaha and Utah beaches. Omaha Beach starts just a few miles west of Arromanches and has the most important sights for visitors. Utah Beach sights are farther away (on the road to Cherbourg), but were also critical to the ultimate success of the Normandy invasion. The American Airborne sector covers a broad area behind Utah Beach and centers on Ste-Mère Eglise.

Omaha Beach is the landing zone most familiar to Americans. This well-defended stretch was where US troops suffered their greatest losses. Going west from Arromanches, I’ve listed four powerful stops (and a few lesser ones): the massive German gun battery at Longues-sur-Mer (which secured the west end of the beach), the American Cemetery, Omaha Beach itself (at Vierville-sur-Mer, the best stop on the beach), and Pointe du Hoc.

• The D-514 coastal road links to all the sights in this section—just keep heading west. I’ve provided specific driving directions where they’ll help. Allow about an hour driving time plus whatever time you spend at each stop.

Four German casemates (three with guns intact)—built to guard against seaborne attacks—hunker down at the end of a country road. The guns, 300 yards inland, were arranged in a semicircle to maximize the firing range east and west, and are the only original coastal artillery guns remaining in place in the D-Day region. (Much was scrapped after the war, long before people thought of tourism.) This battery, staffed by 194 German soldiers, was more defended than the better-known Pointe du Hoc. The Longues-sur-Mer Battery was a critical link in Hitler’s Atlantic Wall defense, a network of more than 15,000 defensive structures stretching from Norway to the Pyrenees. These guns could hit targets up to 12 miles away with relatively sharp accuracy if linked to good target information. The Allies had to take them out.

Cost and Hours: Free and always open (and a good spot for a picnic); on-site TI open April-Oct daily 10:00-13:00 & 14:00-18:00. The TI’s €5.70 booklet is helpful, and guided tours are offered several times a day (€5, one-hour tour, details at TI, +33 2 31 21 46 87, https://bayeux-bessin-tourisme.com).

Getting There: You’ll find the guns 10 minutes west of Arromanches off D-514 on Rue de la Mer (D-104). Follow Port-en-Bessin signs from Arromanches; once in Longues-sur-Mer, turn right at the town’s only traffic light and follow Batterie signs to the free and easy parking lot (with WC).

Visiting the Battery: Walk in a clockwise circle, seeing the inland gun bunkers first and then the command bunker closer to the bluff before circling back to the parking lot. Enter the third bunker you pass. It took seven soldiers to manage each gun, which could be loaded and fired six times per minute (the shells weighed 40 pounds). Climbing above the bunker you can see the hooks that secured the camouflage netting that protected the bunker from Allied bombers.

Head down the path (toward the sea) between the second and third bunkers until you reach a lone observation bunker (the low-lying concrete roof just before the cliffs). This was designed to direct the firing; field telephones connected the observation bunker to the gun batteries by underground wires. Peer out to sea from inside the bunker to appreciate the strategic view over the Channel. From here you can walk along the glorious Sentier du Littoral (coastal path) above the cliffs and see bits of Arromanches’ artificial harbor in the distance, then walk the road back to your car. (You can drive five minutes down to the water on the road that leads from the parking area.)

• Continue west on D-514, passing two small sights of note—Port-en-Bessin and the Big Red One Museum—before arriving at the American Cemetery.

This sleepy-sweet fishing port west of Longues-sur-Mer has a historic harbor, lots of harborfront cafés, a small grocery store, and easy, free parking. Drive to the end of the village, cross the short bridge to the right, and park. While the old harbor was too small to be of use during the invasion, this was the terminus of PLUTO (Pipe Line Under the Ocean), an 80-mile-long underwater fuel line from England. This (and an American version that terminated at Ste-Honorine, one town over) kept the war machine going after the Normandy toehold was established.

In humble Colleville-sur-Mer, this museum is a roadside warehouse filled with D-Day artifacts. This labor of love—one of many small D-Day museums in the area—is the life’s work of Pierre, who for 30 years (since he was a boy) has been scavenging and gathering D-Day gear—and he is still finding good stuff. “Big Red One” refers to the nickname of the 1st Infantry Division, the US Army troops in the first wave (with the 29th Infantry Division) to assault Omaha Beach. Pierre is happy to show visitors around—his passion for his collection adds an extra dimension to your D-Day experience. Near the museum, the main street of little Colleville-sur-Mer is lined with WWII photos.

Cost and Hours: €5, June-Aug daily 10:00-19:00, spring and fall Wed-Mon 10:00-12:00 & 14:00-18:00, closed in winter, Le Bray, Colleville-sur-Mer, +33 2 31 21 53 81.

The American Cemetery is a pilgrimage site for Americans visiting Normandy. Crowning a bluff just above Omaha Beach, 9,386 brilliant white, marble tombstones honor and remember the Americans who gave their lives on the beaches below to free Europe. France has given the US permanent free use of this 172-acre site, which is immaculately maintained by the American Battle Monuments Commission.

A fine modern visitors center prepares you for your visit. Plan to spend at least 1.5 hours at this stirring site. If you come late in the day, a moving flag ceremony takes place at 17:00 at the main flagpole.

Cost and Hours: Free, daily 9:00-18:00, mid-Sept-mid-April until 17:00, +33 2 31 51 62 00, www.abmc.gov.

Tours and Services: Guided 45-minute tours are offered a few times a day in high season (call ahead to confirm times). The best WC is in the basement of the visitors center.

Getting There: The cemetery is just outside Colleville-sur-Mer, a 30-minute drive northwest of Bayeux. Follow signs on D-514 toward Colleville-sur-Mer; at the big roundabout in town (at the Overlord Museum, described later), follow signs leading to the cemetery (plenty of free parking).

From the parking lot, stroll in a counterclockwise circle through the lovingly tended, parklike grounds, making four stops: at the visitors center, the bluff overlooking Omaha Beach, memorials to the fallen and the missing, and finally the cemetery itself.

Visitors Center: The low-slung, modern building is mostly underground. On the arrival level (after security check) are computer terminals providing access to a database containing the Roll of Honor—the names and story of each US serviceman and woman whose remains lie in Europe. Out the window, a rectangular pond points to the infinite sea.

The exhibit downstairs does more than recount the battle. It humanizes the men who fought and died, and are now buried, here. First find a large theater playing the video Letters, a touching 16-minute film with excerpts of letters home from the servicemen who now lie at rest here (shown on the half-hour, you can enter late). Next is a smaller, open theater with a moving eight-minute video, On Their Shoulders. From here, worthwhile exhibits and more videos (one includes an interview with Dwight Eisenhower) tell the stories of the brave individuals who gave their lives to liberate people they could not know, and shows the few possessions they left behind (about 25,000 Americans died in the battle for Normandy).

A lineup of informational plaques on the left wall provides a worthwhile and succinct overview of key events from September 1939 to June 5, 1944. Starting with June 6, 1944, the plaques present the progress of the landings in three-hour increments. Omaha Beach was secured within eight hours of the landings; within 24 hours it was safe to jump off your landing vehicle and slog onto the shore.

You’ll exit the visitors center through the Sacrifice Gallery, with photos and bios of several individuals buried here, as well as those of some survivors. A voice reads the names of each of the cemetery’s permanent residents on a continuous loop.

Bluff Overlooking Omaha Beach: Walk through a parkway along the bluff designed to feel like America (with Kentucky bluegrass) to a viewpoint overlooking the piece of Normandy beach called “that embattled shore, the portal of freedom.” An orientation table looks over the beach and sea. Gazing at the quiet and peaceful beach, it’s hard to imagine the horrific carnage of June 6, 1944. You can’t access the beach directly from here (the path is closed for security)—but those with a car can drive there easily; see the Omaha Beach listing, later. A walk on the beach is a powerful experience.

• With your back to the sea, climb the steps to reach the memorial (on the left).

Memorial and Garden of the Missing: Overlooking the cemetery, you’ll find a striking memorial with a soaring statue representing the spirit of American youth. Around the statue, giant reliefs of the Battle of Normandy and the Battle of Europe are etched on the walls. Behind is the semicircular Garden of the Missing, with the names of 1,557 soldiers who perished but whose remains were never found. A small bronze rosette next to a name indicates one whose body was eventually recovered.

Cemetery: Finally, wander through the peaceful and poignant sea of headstones that surrounds an interfaith chapel in the distance. Names, home states, and dates of death are inscribed on each tombstone, with dog-tag numbers etched into the lower backs. During the campaign, the dead were buried in temporary cemeteries throughout Normandy. After the war, the families of the soldiers could decide whether their loved ones should remain with their comrades or be brought home for burial. (About two-thirds were returned to America.)

Among the notable people buried here are General Theodore Roosevelt Jr., his brother Quentin (who died in World War I but was moved here at the request of the family), and the Niland brothers (whose story inspired Saving Private Ryan). There are 33 pairs of brothers lying side by side, 1 father and son, 149 African Americans, 149 Jewish Americans, and 4 women. From the three generals buried here to the youngest casualty (a teen of just 17), each grave is of equal worth.

• To visit Omaha Beach itself, return up the long driveway to the roundabout (at the Overlord Museum) and follow signs to St-Laurent-sur-Mer (D-514). But first consider popping into the Overlord Museum.

While there are several museums more worthy of your sightseeing energy, you’ll drive right by this purpose-built warehouse filled with Normandy’s most impressive collection of WWII-era vehicles. Offering a good balance of American, British, and German exhibits, the museum’s highlights include Germany’s 88mm antiaircraft and antitank gun (formidable and feared by the Allies), a strafed German Panther tank (the best tank of the Third Reich), a Sherman tank, and a battlefield crane (recalling the on-the-go construction that took place in the field). You’ll also see a horse—a reminder that much of the German war machine was powered by horses—and a Jeep, one of 640,000 made for the war.

Cost and Hours: €8.50, daily June-Aug 9:30-19:00, off-season 10:00-18:30, Oct-March until 17:30, closed Jan, +33 2 31 22 00 55, www.overlordmuseum.com).

• As you continue west on D-514, just before St-Laurent-sur-Mer, be on the lookout for the well-signed...

La Ferme de la Sapinière is a stony apple farm welcoming guests with lots of free tastes along with a few photos of this family’s (seven generations on this same farmstead) war experience. Drop-ins are welcome for tastings or you can join a one-hour tour in English that explains the growing, pressing, and fermenting of apples in Normandy (followed by tasting).

Cost and Hours: Open daily for tasting 9:30-18:30 except closed Sun Oct-March; tour/tasting-€3.50, April-mid-Nov Mon-Sat at 14:30, no tours on Sun, wise to call first; +33 2 31 22 40 51, www.producteur-cidre.com. The farm is just off D-514 (Route de Port-en-Bessin) between the American Cemetery and St-Laurent-sur-Mer.

• From the farm, return to westbound D-514. At the next roundabout, follow signs to Vierville s/Mer par la Côte to get to Omaha Beach.

Omaha Beach has five ravines (or “draws”), which provided avenues from the beach past the bluff to the interior. These were the goal of the troops that day. You’ll drive down one (the Avenue de la Libération)—passing the small Omaha Beach Memorial Museum—to reach the beach and two commemorative statues. Then drive west along the beach to the National Guard Memorial before leaving the beach up a second ravine.

Skip the museum (for most visitors, it’s not worth the entry), but WWII junkies should make a quick stop in the parking lot. On display is a rusted metal obstacle called a “Czech hedgehog”—thousands of these were placed on the beaches by the Germans to stop and immobilize landing craft and foil the Allies’ advance. Find the American 155mm “Long Tom” gun nearby, and keep it in mind for your stop at Pointe du Hoc (this artillery piece is similar in size to the German guns that US Army Rangers targeted at that site). The Sherman tank here is one of the best examples of the type that landed on the D-Day beaches.

• You’ll hit the beach at a roundabout. Park your car for a look at the two memorials, and to take a stroll on the beach. (If parking is tight or you want a quieter beach experience, turn right along the water and find a spot farther down along the road.)

Omaha was the most difficult of the D-Day beaches to assault. Nicknamed “Bloody Omaha,” nearly half of all D-Day casualties were suffered here.

Two American assault units landed on Omaha Beach—the 1st Infantry Division (the “Big Red One,” a veteran formation) and the 29th Infantry Division (a National Guard citizen army unit with little combat experience). For those troops, everything went wrong.

The four-mile-long beach is surrounded on three sides by cliffs, which were heavily armed by Germans. The Allies’ preinvasion bombing was ineffective, and about 500 Germans manning 11 gun nests pummeled the beach all day. Thanks to the concave shape of the beach, German artillery was positioned to hit every landing ship. It was an amphitheater of death. If the tide is out, you’ll see little skinny lakes between the sandbars. These were blood red on D-Day.

Those who landed first and survived were pinned down, played dead, and came in with the tide over a period of four hours. Troops huddled against the beachhead for six to eight hours awaiting support—or death. But reinforcements kept coming, and thanks to navy ships that moved in dangerously close to shallow water, then turned broadside so they could fire at the Germans, the attack ended successfully. By the end of the day, 34,000 Americans had landed on the beach, and the Germans had been pushed back. In the next 34 days, these troops built 34 airfields. The final assault leading to Berlin was under way.

You’re at the center of Omaha Beach. While only Americans landed on this beach, the flags recognize eight nations that took part in the invasion. A striking modern metal statue (The Braves, 2004) rises from the waves in honor of the liberating forces and symbolizes the rise of freedom on the wings of hope. Next to that is a much older memorial from 1949. Built by thankful French, it was funded by selling scrap metal after the war and honors the two assaulting divisions, the 29th and 1st. You can read the motto of the 1st Division: “No mission too difficult. No sacrifice too great. Duty first.”

• Drive west from here along the beachfront, nicknamed “Golden Beach” before the war for its lovely sand.

While movie images may give the impression that the D-Day beaches were wild, they were actually lined with humble beach hotels and vacation cottages much like those you see today. After about 300 yards, you’ll pass a small memorial down on your left. This marks the site of the first temporary American cemetery (which was moved after about three days, as it provided a sad welcome to newly landed troops).

• Drive until you see a wharf stretching out from the Hôtel du Casino, at the base of the next ravine, where you’ll find a couple of battlements and monuments. Park in the lot across from the hotel and walk toward the boxy gray monument by the flagpoles. Find the bronze statues of soldiers.

These two bronze soldiers commemorate the so-called “Bedford Boys” and the little Virginia town of Bedford that contributed 35 men to the landing forces—19 were killed.

Look out to the ocean. It was here that the Americans assembled a floating bridge and artificial harbor (à la Arromanches; for a description, find the panel near the blue telescope). The harbor was under furious construction for 12 days before being destroyed by an unusually vicious June storm (the artificial port at Arromanches and a makeshift port at Utah Beach survived and were used until November 1944).

• Walk down the steps of the boxy gray monument next to the statues.

The 29th Infantry Division, a National Guard unit, was one of the American assault units that landed on Omaha Beach on D-Day. While well-trained and disciplined, these troops were less experienced than the battle-tested 1st Division, their landing partners. A memorial to their sacrifices is built atop an 88mm German artillery casement.

Peer down through the cage into the gun station. Rather than being aimed out to sea, this gun was aimed at the beach. It could shoot all the way across the beach in two seconds at the rate of two well-aimed shots per minute. Notice the desperate bullet holes all around the gun. Its twin was several miles away at the opposite end of Omaha Beach. In 1944 the Germans built this gun station and hid it inside the facade of a fake beach hotel. A second gun casement with two 50mm guns, a few steps to the west, added to the Omaha Beach carnage.

The nearby pier offers good views—handy if the tide is in. This is also a good place to walk along the beach.

• From here, drive uphill on D-517 to return to coastal road D-514 at Vierville-Sur-Mer (as you head up, immediately look above and to your left to find two small concrete window frames high in the cliff that served as German machine gun nests).

When you reach D-514, turn right (west) and head toward Pointe du Hoc. Along the way, just past the turnoff for the hamlet of Englesqueville la Percée (D-125), you’ll have an opportunity to quench your thirst.

A 10th-century fortified farm on the left offers Calvados tastings. To try some, cross the drawbridge and park on the right. Ring the rope bell and meet charming owners Soizic and Bernard Lebrec (+33 9 60 38 60 17). They’re happy to offer a free three-part tasting: cider, Pommeau (a mix of apple juice and Calvados), and a six-year-old Calvados. Consider their enticing selection of drinkable souvenirs. Bernard likes to share his family’s D-Day scrapbook (his farm was requisitioned as a military base in 1944). Ask to see the farm’s own D-Day monument. Erected in September 1944—before the war was even over—it’s likely one of the earliest in France.

• Rejoin D-514, and at the next roundabout, follow signs to Pointe du Hoc.

The intense bombing of the beaches by Allied forces is best understood at this bluff. This point of land was the Germans’ most heavily fortified position along the Utah and Omaha beaches. The cliffs are so severe here that the Germans turned their defenses around to face what they assumed would be an attack from inland. Yet US Army Rangers famously scaled the impossibly steep cliffs to disable the gun battery. Pointe du Hoc’s bomb-cratered, lunar-like landscape and remaining bunkers make it one of the most evocative of the D-Day sites.

Cost and Hours: Free, always open; visitors center open daily 9:00-18:00, mid-Sept-mid-April until 17:00, +33 2 31 51 62 00, www.abmc.gov/cemeteries-memorials. It’s off route D-514, 20 minutes west of the American Cemetery, in Cricqueville-en-Bessin.

Crowd Control: The sight is most crowded in the afternoons. Try to avoid 14:00-16:00 in summer.

Two paths lead to the site, one from each end of the long parking lot (take one path out and the other back).

The visitors center is at the eastern end of the lot. If you have time, stop here for the WCs and to see the eight-minute film explaining the daring Ranger mission from a personal perspective, through interviews with survivors. But if the security line is long, skip it, or save it for later.

Follow either gravel path to the site (both with info panels focusing on individual Rangers). The path to the western end of the site leads past a big French 155mm gun barrel from World War I. While state-of-the-art in 1917, in World War II this gun was still formidable. Six of these were what Pointe du Hoc was all about. The other path near the visitors center leads to an opening (on the left) that’s as wide as a manhole cover and about six feet deep. This was a machine gun nest that had three soldiers crammed inside—a commander, a gunner, and a loader.

Lunar Landscape: The craters are the result of 10 kilotons of bombs—nearly the explosive power of the atomic bomb at Hiroshima—but dropped over seven weeks. This was a jumbo German gun battery, with more than a mile of tunnels connecting its battlements. Its six 155mm guns could fire as far as 13 miles—good enough to hit anything on either beach. For the American D-Day landings to succeed, this nest had to be taken out. So the Allies pulverized it with bombs, starting in April 1944 and continuing until June 6—making this the most intensely bombarded of the D-Day targets. Even so, the heavily reinforced bunkers survived.

Walk around. The battle-scarred German bunkers and the cratered landscape remain much as the Rangers left them. You can identify the gun placements by the short, circular, concrete walls, sometimes with the rusted remains of a gun support sticking out of the center. The guns sat in wide-open placements. You can crawl in and out of the bunkers at your own risk, or stick to the viewing platforms with helpful information panels. Work your way to the bunker with the tall stone memorial at the cliff edge.

Dagger Memorial: The memorial represents the Ranger dagger used to help scale the cliffs. Here, it’s thrust into the command center of the battery. Exploring the heavily fortified interior of this observation bunker (officers’ quarters, enlisted quarters, and command room) with its charred ceiling and battered hardware, you can imagine the fury of the attack that finally took this station. The slit is only for observing. This bunker was the “eyes” of the guns—from here spotters directed the firing via hard-wired telephone, sending coordinates to the gunners at the six 155mm guns. The bronze plaque in the larger room honors the Rangers who did not return from this mission.

Walk down the steps to the front of the bunker for the greatest impact. Peer over the cliff and think about the 225 handpicked Rangers who attempted a castle-style assault on the gun battery (they landed on the beach down to the right). They used rocket-propelled grappling hooks connected to 150-foot ropes, and climbed ladders borrowed from London fire departments.

Timing was critical; the Rangers had just 30 minutes to get off the beach before the rising tide would overcome them. Fortunately, the soldiers successfully surprised the Germans and climbed to the top in two hours—the Germans had prepared no defense for an attack up the cliffs. The most dangerous part of the Ranger’s mission occurred after reaching the top, when they faced an intense German counterattack. The Rangers used the bomb craters as foxholes until reinforcements arrived.

Then it was the Americans’ turn to be surprised. After taking control of the clifftop, the Rangers found that the guns had been moved—the Germans had put telegraph poles in their place as decoys. The Rangers eventually found the operational guns hidden a half-mile inland and destroyed them.

Three American presidents (Eisenhower in 1963, Reagan in 1984, and Clinton in 1994) have stood at this bunker to honor the heroics of those Rangers.

Viewing Platform: Navigate the craters inland about 100 yards to another bunker capped with a viewing platform. Climb up top to appreciate the intensity of the blasts that made the craters and disabled phone lines—cutting communication between the command bunker and the guns to render them blind.

• Our tour of the American Omaha Beach sights is finished. To consider the other side of the conflict, it’s worth visiting the German Military Cemetery at La Cambe. To get there from Pointe du Hoc, follow D-514 west, then turn off in Grandcamp following signs to La Cambe and Bayeux (D-199). After crossing over the autoroute, turn left at the first country road and follow it around to the cemetery.

To appreciate German losses, visit this somber, thought-provoking final resting place of 21,000 German soldiers. Compared to the American Cemetery at St-Laurent, this site is more about humility than hero appreciation. The cemetery was not inaugurated until 1961—it took that long to identify bodies and find next of kin.

Cost and Hours: Free, daily April-Oct 8:00-19:00, off-season generally 9:00-17:00, +33 2 31 22 70 76. Good WCs are in the back of the visitors center.

Getting There: La Cambe is 15 minutes south of Pointe du Hoc and 20 minutes west of Bayeux (from the autoroute, follow signs reading Cimetière Militaire Allemand).

Visiting the Cemetery: The largest of six German cemeteries in Normandy, it’s appropriately bleak, with two graves per simple marker and dark basalt crosses in groups of five scattered about. The tall circular mound in the middle—with a cross, topped by a grieving mother and father—covers the remains of about 300 mostly unknown soldiers. You can climb to the top for a different perspective over the cemetery.

Wandering among the tombstones, notice the ages of the soldiers who gave their lives for a cause some were too young to understand. “Strm” indicates storm trooper—the most ideologically motivated troops that bolstered the German army. About a fifth of the dead are unidentified, listed as “Ein Deutscher Soldat.” You’ll also notice many who died after the war ended—a reminder that over 5,000 German POWs perished in France clearing the minefields their comrades had planted.

A field hospital was sited in this area during the war, and originally American troops were buried here. After the war, those remains were moved to the current American Cemetery or returned to the US. A small visitors center—with a focus on building peace—has information about German war cemeteries, a small display showing the German soldiers’ last letters home, and a case of their artifacts. Visiting here, you can imagine the complexity of dealing with this for today’s Germans.

With a car, you can sleep in the countryside, find better deals on accommodations, and wake up a stone’s throw from many landing sites. Besides these recommended spots, you’ll pass scads of good-value chambres d’hôtes as you prowl the D-Day beaches. The last two places are a few minutes toward Bayeux on D-517 in the village of Formigny.

$$ Hôtel la Sapinière** is a find just a few steps from the beach at Vierville-sur-Mer. A grassy, beach-bungalow kind of place, it has 15 sharp rooms, all with private patios, and a lighthearted, good-value restaurant/bar (family rooms, outside St-Laurent-sur-Mer 10 minutes west of the American Cemetery—take D-517 down to the beach, turn right and keep going to 100 Rue de la 2ème Division D’Infanterie US, for location see the “D-Day Beaches” map on here, +33 2 31 92 71 72, www.la-sapiniere.fr, sci-thierry@wanadoo.fr).

$$ Hôtel du Casino*** is a good place to experience Omaha Beach. This average-looking hotel has surprisingly comfortable rooms and sits alone overlooking the beach in Vierville-sur-Mer, between the American Cemetery and Pointe du Hoc. All rooms have views, but the best face the sea: Ask formal owner Madame Clémençon for a côté mer (elevator, view restaurant with menus from €30, café/bar on the beach below, Rue de la Percée, for location see the “D-Day Beaches” map on here, +33 2 31 22 41 02, www.logishotels.com [URL inactive], hotel-du-casino@orange.fr). Don’t confuse this with Hôtel du Casino in St-Valery-en-Caux.

$ La Ferme aux Chats sits on D-517 across from the church in the center of Formigny and has a cozy lounge with a library of D-Day information, and four clean, comfortable, modern rooms (includes breakfast, for location see the “Omaha Beach Area” map on here, +33 2 31 51 00 88, www.lafermeauxchats.fr, info@fermeauxchats.fr).

At $ Ferme du Mouchel, animated Odile rents three colorful and good rooms with impeccable gardens in a lovely farm setting in the village of Formigny (cash only, includes breakfast, 3-day minimum in summer, +33 2 31 22 53 79, mobile +33 6 15 37 50 20, www.ferme-du-mouchel.com, odile.lenourichel@orange.fr). Follow the sign from the main road (D-517), then turn left down the tree-lined lane when you see the Le Mouchel sign (for location see the “Omaha Beach Area” map on here).

Utah Beach, added late in the planning for D-Day, proved critical. This was where two US paratrooper units (the 82nd and the 101st Airborne Divisions) dropped behind enemy lines the night before the invasion, as dramatized in Band of Brothers and The Longest Day. Many landed off-target. It was essential for the invading forces to succeed here, then push up the peninsula (which had been intentionally flooded by the Nazis) to the port city of Cherbourg.

Utah Beach was taken in 45 minutes at the cost of 194 American lives. More paratroopers died (over 1,000) preparing the way for the actual beach landing. Fortunately for the Americans who stormed this beach, it was defended not by Germans but mostly by conscripted Czechs, Poles, and Russians who had little motivation for this fight.

While the brutality on this beach paled in comparison with the carnage on Omaha Beach, most of the paratroopers missed their targets—causing confusion and worse—and the units that landed here faced a three-week battle before finally taking Cherbourg. Ultimately over 800,000 Americans (and 220,000 vehicles) landed on Utah Beach over a five-month period.

• These stops are listed in the order you’ll find them coming from Bayeux or Omaha Beach. For the first two, take the Utah Beach exit (D-913) from N-13 and turn right (see the “D-Day Beaches” map on here).

Allow 40 minutes to reach Angoville-au-Plain if you come direct from Bayeux, and another 45 minutes to drive between the Utah Beach sites, plus time at each stop.

At this simple Romanesque church, two young American medics—Kenneth Moore and Robert Wright—treated the wounded while battles raged only steps away. On June 6, American paratroopers landed around Angoville-au-Plain, a few miles inland of Utah Beach, and met fierce resistance from German forces. The two medics (who also parachuted in) set up shop in the small church and treated both American and German soldiers for 72 hours straight, saving many lives. German patrols entered the church on a few occasions. The medics insisted that the soldiers park their guns outside or leave the church—incredibly, they did. In an amazing coincidence, this 12th-century church is dedicated to two martyrs who were doctors.

An informational display outside the church recounts the events here; an English handout is available inside. Pass through the small cemetery and enter the church. Inside, several wooden pews toward the rear still have visible bloodstains. Find the new window that honors the American medics and another that honors the paratroopers.

After surviving the war, both Wright and Moore returned to the US and led full lives. Wright’s wish was to be buried here; you’ll find his grave in the cemetery to the left of the church entry.

Cost and Hours: €3 requested donation for brochure, daily 9:00-18:00, 2 minutes off D-913 toward Utah Beach.

• As you continue toward the beach, you’ll see a statue on the left a few minutes after passing through Ste-Marie-du-Mont. This honors paratrooper Richard Winters, a hero of the 101st Airborne Division’s “Easy Company,” who landed near here. Winters was the leader of the company portrayed in Band of Brothers.

This is the best museum located on the D-Day beaches, and worth the 45-minute drive from Bayeux. For the Allied landings to succeed, a myriad of complex tasks had to be coordinated: Paratroopers had to be dropped inland, the resistance had to disable bridges and cut communications, bombers had to soften German defenses by delivering their payloads on target and on time, the infantry had to land safely on the beaches, and supplies had to follow the infantry closely. This thorough yet manageable museum pieces those many parts together in a series of fascinating exhibits and displays.

Cost and Hours: €8, daily June-Sept 9:30-19:00, Oct-Nov and Jan-May 10:00-18:00, closed Dec, last entry one hour before closing, +33 2 33 71 53 35, off D-913 at Plage de la Madeleine, www.utah-beach.com. Park in the “obligitaire” lot, then walk five minutes to reach the museum.

Film and Tours: Check for the next English video time as you pay. Guided tours of the museum and the beachfront are offered twice a day (€4, call ahead for times or ask when you arrive, tips are appropriate).

Built around the remains of a concrete German bunker, the museum nestles in the sand dunes on Utah Beach with floors above and below beach level. Your visit follows a one-way route beginning with background about the American landings on Utah Beach (over 20,000 troops landed on the first day alone) and the German defense strategy (Rommel was in charge of maintaining the western end of Hitler’s Atlantic Wall). See the outstanding 12-minute film, Victory in the Sand, which sets the stage.

Highlights of the museum are the displays of innovative invasion equipment with videos demonstrating how it all worked (most were built for civilian purposes and adapted to military use): the remote-controlled Goliath mine, the LVT-2 Water Buffalo and Duck amphibious vehicles, and the wooden Higgins landing craft. Next, see a fully restored B-26 bomber with its zebra stripes and 11 menacing machine guns—find the one at the rear, without which the landings would not have been possible (the yellow bomb icons painted onto the cockpit indicate the number of missions a plane had flown).

Upstairs is a large, glassed-in room overlooking the beach. From here, you’ll peer over re-created German trenches and get a sense for what it must have been like to defend against such a massive and coordinated onslaught.

Outside the museum, find the beach access where Americans first broke through Hitler’s “Atlantic Wall.” Pile into the Higgins boat replica (this one is made of steel—those used in the landings were made from plywood). You can hike up to the small bluff, which is lined with monuments to the branches of military service that participated in the fight. A gun sits atop a buried battlement under the flags, part of a vast underground network of German defenses. And all around is the hardware of battle frozen in time.

• To reach the next several sights, follow the coastal route D-421 and signs to Ste-Mère Eglise.

This celebrated village lies 15 minutes west of Utah Beach and was the first village to be liberated by the Americans. The area around Ste-Mère Eglise was the center of action for American paratroopers, whose objective was to land behind enemy lines before dawn on D-Day and wreak havoc in support of the Americans landing at Utah Beach that day.

For The Longest Day movie buffs, Ste-Mère Eglise is a necessary pilgrimage. It was in and near this village that many paratroopers, facing terrible weather and heavy antiaircraft fire, landed off-target—and many landed in the town. American paratrooper Private John Steele dangled from the town’s church steeple for two hours (a parachute has been reinstalled on the steeple near where Steele became snagged). Though many paratroopers were killed in the first hours of the invasion, the Americans eventually overcame their poor start and managed to take the town. (Steele survived his ordeal by playing dead). These troops who dropped (or glided) in behind enemy lines in the dark played a critical role in the success of the Utah Beach landings by securing roads and bridges.

Today, the village greets travelers with flag-draped streets (and plenty of pay parking). The 700-year-old medieval church on the town square now holds two contemporary stained-glass windows. One, in the back, celebrates the heroism of the Allies (made in 1984 for the 40th anniversary of the invasion). The window in the left transept features St. Michael, patron saint of paratroopers (made in 1969 for the 25th anniversary).

The TI on the square across from the church has loads of information (July-Aug Mon-Sat 8:30-18:00, Sun 10:00-16:00; Sept and April-June closes Mon-Sat 12:00-14:00 and on Sun; shorter hours off-season; 6 Rue Eisenhower, +33 2 33 21 00 33, www.ot-baieducotentin.fr [URL inactive]).

This four-building collection is dedicated to the daring aerial landings that were essential to the success of D-Day. During the invasion, in the Utah Beach sector alone, 23,000 men were dropped from planes or landed in gliders, along with countless vehicles and tons of supplies.

Cost and Hours: €10, daily May-Aug 10:00-19:00, April and Sept 9:30-18:30, shorter hours off-season and closed Jan, 14 Rue Eisenhower, +33 2 33 41 41 35, www.airborne-museum.org [URL inactive].

Visiting the Museum: Your visit to the museum unfolds across four buildings (allow a full hour to visit). In the first building, you’ll see a Waco glider, one of 104 such gliders flown into Normandy at first light on D-Day to land supplies in fields to support the paratroopers. These gliders could normally be used only once. Feel the canvas fuselage and check out the bare-bones interior.

The second, larger building holds a Douglas C-47 plane that dropped paratroops and supplies. Here you’ll find mannequins of soldiers (including Gen. Dwight Eisenhower) with their uniforms, displays of their personal possessions and weapons, and a movie that venerates President Ronald Reagan’s 1984 trip to Normandy.

A third structure, labeled Operation Neptune, puts you into the paratrooper’s experience starting with a night flight and jump, then tracks your progress on the ground past enemy fire using elaborate models and sound effects. Don’t miss the touching video just before the exit showing the valor of Gen. Theodore Roosevelt Jr. on D-Day.

The fourth building houses temporary exhibits and a cushy theater showing a good 20-minute film focusing on the airborne invasion.

• From Ste-Mère Eglise, head 10 minutes on N-13 (back toward Bayeux) to St-Côme-du-Mont.

This unique museum is dedicated to the paratroopers of the 101st Airborne Division (a.k.a. the “Screaming Eagles”), the first to land in Normandy. The museum has three parts: the “Dead Man’s Corner” exhibit that focuses on the battles that raged around this vital location, the D-Day Experience section, and a 36-minute 3-D IMAX film about the Battle of Normandy and Battle of Carentan. It’s a labor of love for the passionate owners, crammed with lots of artifacts, uniforms, and experiences.

The highlight is the D-Day Experience with two creative exhibits designed to help you feel what it might have been like to be in the 101st. You’ll enter a briefing room for a 10-minute review of your mission by a hologram commander. Then you’ll climb into an authentic Douglas C-47 (built in 1943, it actually flew on D-Day), buckle in, survive a simulated flight through flak across the English Channel, and then crash-land before you can parachute out.

Cost and Hours: €13 for flight simulator and museum, €19 for the whole enchilada (adds 3-D film); daily April-Sept 9:30-19:00, Oct-March 10:00-18:00; 2 Vierge de l’Amont (D-913), St-Côme-du-Mont, +33 2 33 23 61 95, www.dday-experience.com.

The Canadians’ assignment for the Normandy invasions was to work with British forces to take the city of Caen. They hoped to make quick work of Caen, then move inland. That didn’t happen. The Germans poured most of their reserves, including tanks, into the city and fought ferociously for a month. The Allies didn’t occupy Caen until August 1944.

Located on the beachfront in the Canadian sector, this facility—inaugurated in 2003—is dedicated to teaching travelers about the vital role Canadian forces played in the invasion, and about Canada in general. Canada declared war on Germany two years before the United States, a fact little recognized by most Americans today (after the US and Britain, Canada contributed the largest number of troops to D-Day—14,000). The Centre includes many thoughtful exhibits that bring to life Canada’s unique ties with Britain, the US, and France, and explains how the war front affected the home front in Canada.

Cost and Hours: €7.50, €12 with guided tour of Juno Beach—highly recommended; open daily April-Sept 9:30-19:00, Oct and March 10:00-18:00, Nov-Dec and Feb 10:00-17:00, closed Jan; +33 2 31 37 32 17, www.junobeach.org.

Tours: The best way to appreciate this sector of the D-Day beaches is to take a tour with one of the Centre’s capable Canadian guides, who will take you down into two bunkers and a tunnel of the German defense network (€6 for tour alone, 45 minutes; April-Oct generally at 10:30 and 14:30, July-Aug also at 11:30, 13:30, 14:30, and 16:30; verify times prior to your visit). If you can’t make a tour, ask for the brochure that gives a self-guided tour of the beaches.

Getting There: It’s in Courseulles-sur-Mer, about 15 minutes east of Arromanches off D-514. Approaching from Arromanches, as you enter the village of Grave-sur-Mer, watch for the easy-to-miss Juno Beach-Mémorial sign marking the turnoff on the left; you’ll drive the length of a sandy spit (passing a marina) to the end of the road at Voie des Français Libres, where you’ll find the parking lot.

Visiting the Juno Beach Centre: Your visit begins with a short film designed to get you inside the soldier’s heads as their boats neared the shore. Then you’ll view informative exhibits about the various Canadian forces and their contributions to the invasion. You’ll learn about the campaigns that Canadian soldiers were most involved with (such as the disastrous raid on Dieppe) and understand the immense challenges they faced during and after the landings. A scrolling list honors the 45,000 Canadians who died in World War II and a large hall highlights the vital roles women played in the war. Your visit ends with a powerful, 12-minute film that captures Canada’s D-Day experience.

Take advantage of the center’s eager-to-help, red-shirted “student-guides” (young Canadians working a seven-month stint here). Ask about the bulky “kiosks” in front of the center and get their take on other D-Day sites.

Nearby: Between the main road and the Juno Beach Centre, you’ll spot a huge stainless-steel double cross (by a row of French flags). This is La Croix de Lorraine, marking the site where General de Gaulle returned to France (after four years of exile) on June 14, 1944. A small memorial just beyond is dedicated to the 16,000 Polish soldiers who fought in the Battle of Normandy.

This small, touching cemetery hides a few miles above the Juno Beach Centre. To me, it captures the understated nature of Canadians perfectly. Surrounded by pastoral farmland with distant views to the beaches, you’ll find 2,000 graves marked with maple leaves and the soldiers’ names and ages. Most fell in the first weeks of the D-Day assault. Like the American Cemetery, this is Canadian territory on French land.

Getting There: From Courseulles-sur-Mer, follow signs to Caen on D-79. After a few kilometers, follow D-35 toward Reviers (and Bayeux). The cemetery is on Route de Reviers.

Caen, the modern capital of lower Normandy, has the most thorough (and by far the priciest) WWII museum in France. Located at the site of an important German headquarters during World War II, its official name is Caen-Normandy Memorial: Center for History and Peace (Mémorial de Caen-Normandie: Cité de l’Histoire pour la Paix). With thorough coverage of the lead-up to World War II and of the war in both Europe and the Pacific, accounts of the Holocaust and Nazi-occupied France, the Cold War aftermath, and more, it effectively puts the Battle of Normandy into a broader context and is worth ▲▲.

It’s like a history course that prepares you for the D-Day sites, but it’s a lot to take in with a single visit (tickets are valid 24 hours). If you have the time and attention span, it’s as good as it gets. If forced to choose, I prefer the focus of many of the smaller D-Day museums at the beaches.

Town of Caen: The old center of Caen is appealing and, with its château and abbeys, makes a tempting visit. But, I’d focus on Bayeux and the D-Day beaches. Bayeux or Arromanches—which are much smaller—make the best base for most D-Day sites, though train travelers with limited time might find urban Caen more practical.

The TI is at 12 Place St. Pierre, 10 long blocks from the train station—take the tram to the St. Pierre stop (Mon-Sat 9:30-18:30, until 19:00 July-Aug, Sun 10:00-13:00 & 14:00-17:00 except closed Sun Oct-March, drivers follow Parking Château signs, +33 2 31 27 14 14, www.caenlamer-tourisme.fr).

If Caen is your first stop on a longer trip, consider renting a car after arriving at the train station. Several major rental agencies have offices close by.

A looming château, built by William the Conqueror in 1060, marks the city’s center. To the west, modern Rue St. Pierre is a popular shopping area and pedestrian zone. The more historic Vagueux quarter to the east has many restaurants and cafés.

By Car: From Bayeux, it’s a straight shot on the N-13 to Caen (30 minutes). From Paris or Honfleur, follow the A-13 autoroute to Caen. When approaching Caen, take the Périphérique Nord (ring-road expressway) to sortie (exit) #7—the museum is a half-mile from here. Look for white Le Mémorial signs. When leaving the museum, follow Toutes Directions signs back to the ring road.

By Train or Bus: By train, Caen is two hours from Paris (12/day) and 20 minutes from Bayeux (20/day). The modern train station sits next to the gare routière, where buses from Honfleur arrive (2/day express or 7-12/day local). There’s no baggage storage at the station, though it is available (and free) at the museum. Car rental offices are nearby.

Taxis usually wait in front of the train station and will get you to the museum in 15 minutes (about €18 one-way—more expensive on Sun). A tram-and-bus combination takes about 30 minutes (Mon-Sat only): Take the tram right in front of the train station (line A, direction: Campus 2, or line B, direction: St. Clair; buy €1.50 ticket from machine and validate on tram and again on bus, good for entire trip). Get off at the third tram stop (Bernières), then transfer to frequent bus #2 (cross the street). For transit maps, see www.twisto.fr.

To return to the station, take bus #2 across from the museum (museum has schedule, buy ticket from driver and validate); transfer to the tram at the Quatrans stop in downtown Caen. Either line A or line B will take you to the station (Gare SNCF stop).

Cost and Hours: €20, ticket valid 24 hours, free for all veterans and kids under 10 (ask about good family rates), €22.50 combo-ticket with Arromanches 360° theater (see here). Open March-Sept daily 9:00-19:00; Oct-Dec and Feb Tue-Sun 9:30-18:00, closed Mon; closed most of Jan (Esplanade Général Eisenhower).

Information: Dial +33 2 31 06 06 44—as in June 6, 1944, www.memorial-caen.fr.

Planning Your Time: Allow at least two hours for your visit. The museum is divided into two major wings: one devoted to the years before and during World War II, and the other to the Cold War years and later. Focus on the WWII wing.

Visitor Information: English descriptions are posted at every exhibit (but if you read every word, you’d be here for days). The €4.50 audioguide is well done and adds insight to the exhibits—a kid’s version is also available.

Services: The museum provides free baggage storage and free supervised childcare for children under age 10. The large gift shop has plenty of books in English.

Eating: An all-day sandwich shop/café with reasonable prices sits above the entry area, and there’s a restaurant with garden-side terrace (lunch only). Picnicking in the gardens is an option.

Minivan Tours: The museum offers good-value minivan tours covering the key sites along the D-Day beaches and is a good option for day-trippers from Paris (though tours may be in French and English). The all-day “D-Day Tour” package (€140) includes pickup/drop off at the Caen train station, a tour of the museum followed by lunch, and a five-hour tour of the American sector (there’s a similar tour option to Juno Beach). There’s also a €99 half-day minivan tour that includes free entry to the museum (no tour) but no lunch. It’s appropriate to tip if you were satisfied with your tour.

Find Début de la Visite signs and begin your museum tour here with a downward-spiral stroll, tracing (almost psychoanalyzing) the path Europe and America followed from the end of World War I to the rise of fascism to World War II. Rooms are decorated to immerse you in the pre-WWII experience.

The “World Before 1945” exhibits deliver a thorough description of how World War II was fought—from General Charles de Gaulle’s London radio broadcasts to Hitler’s early missiles to wartime fashion to the D-Day landings. Videos, maps, and countless displays relate the stories of the Battle of Britain, Vichy France, German death camps, the Battle of Stalingrad, the French Resistance, the war in the Pacific, and finally, liberation. Several powerful displays summarize the terrible human costs of World War II, from the destruction of Guernica in Spain to the death toll (21 million Russians died during the war; Germany lost 7 million; the US lost 300,000). A smaller, separate exhibit (on your way back up to the main hall) covers D-Day and the Battle of Normandy, though the battle is better covered at other D-Day museums described in this chapter.

Next, don’t miss the 25-minute film, Saving Europe, an immersive and, at times, graphic black-and-white film covering the agonizing 100 days of the Battle of Normandy (runs every half-hour 10:00-18:00, English subtitles).

At this point, you’ve completed your WWII history course. Next comes the “World After 1945” wing, which sets the scene for the Cold War with photos of European cities destroyed during World War II and insights into the psychological battle waged by the Soviet Union and the US for the hearts and minds of their people until the fall of communism (you’ll even see a real Soviet MiG 21 fighter jet). The wing culminates with an important display recounting the division of Berlin and its unification after the fall of the Wall.

Two more stops are outside the rear of the building. I’d skip the first, a re-creation of the former command bunker of German General Wilhelm Richter, with exhibits on the Nazi Atlantic Wall defense in Normandy. Instead, finish your tour with a walk through the US Armed Forces Memorial Garden (Vallée du Mémorial). On a visit here, I was bothered at first by the seemingly unaware laughing of lighthearted children, unable to appreciate the gravity of their surroundings. Then I read this inscription on the pavement: “From the heart of our land flows the blood of our youth, given to you in the name of freedom.” And their laughter made me happy.

For more than a thousand years, the distant silhouette of this island abbey has sent pilgrims’ spirits soaring. Today, it does the same for tourists. Mont St-Michel, one of the top pilgrimage sites of Christendom through the ages, floats like a mirage on the horizon. For centuries devout Christians endeavored to make a great pilgrimage once in their lifetimes. If they couldn’t afford Rome, Jerusalem, or Santiago de Compostela, they came here, earning the same religious merits. Today, several million visitors—and a steady trickle of pilgrims—flood the single street of the tiny island each year. If this place seems built for tourism, in a sense it was. It’s accommodated, fed, watered, and sold trinkets to generations of travelers visiting its towering abbey.

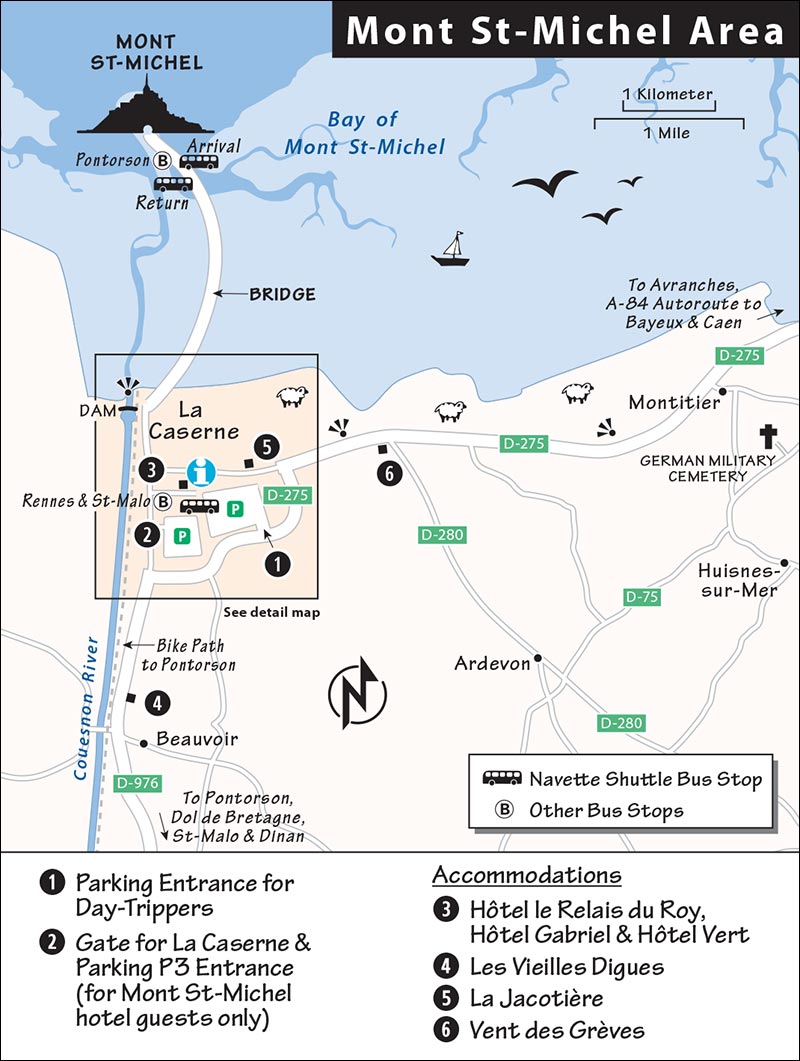

The easiest way to get to Mont St-Michel is by car, but train, bus, and minivan options are also available. A fast TGV train serves nearby Rennes (with bus connections to Mont St-Michel), and Flixbus runs direct and cheap bus service to the island from Paris’ Gare de Bercy. Also, minivan shuttle services can zip you here from Bayeux. See “Mont St-Michel Connections” and “Bayeux Connections” for more details.

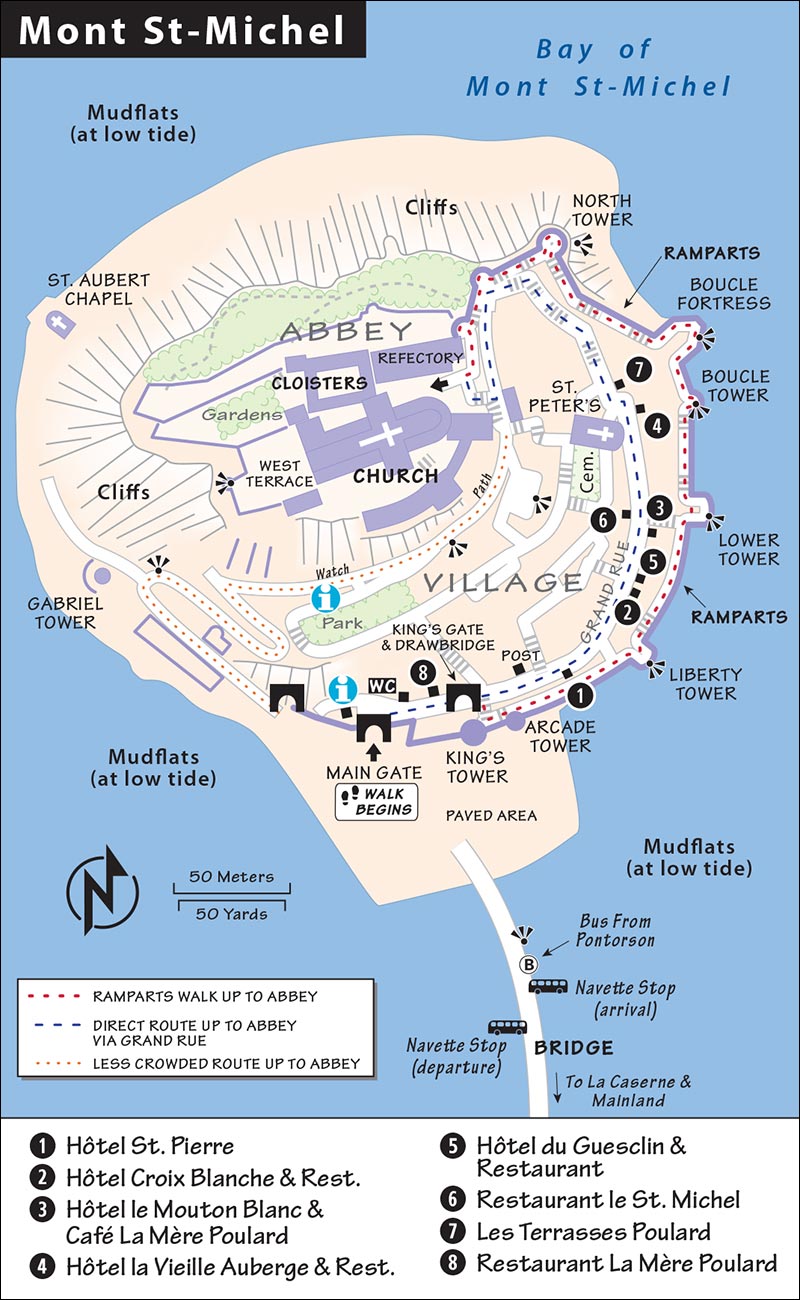

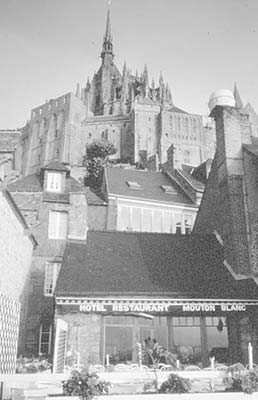

Mont St-Michel is surrounded by a vast mudflat and connected to the mainland by a bridge. Think of the island as having three parts: the Benedictine abbey soaring above, the spindly road leading to the abbey, and the medieval fortifications below. The lone main street (Grand Rue), with the island’s hotels, restaurants, and trinkets, is mobbed in-season from 11:00 to at least 16:00. Though several tacky history-in-wax museums tempt visitors with hustlers out front, these are commercial gimmicks with no real artifacts. The only worthwhile sights are the abbey at the summit and a ramble on the ramparts, which offers mudflat views and an escape from the tourist zone.

The “village” on the mainland side of the causeway (called La Caserne) was built to accommodate tour buses. It consists of a lineup of modern hotels, a handful of shops, vast parking lots, and efficient shuttle buses zipping to and from the island every few minutes.

The tourist tide comes in each morning and recedes late each afternoon. To avoid crowds, arrive late in the afternoon, sleep on the island or nearby on the mainland, and depart early.

On the mainland, near the parking lot’s shuttle stop, look for the helpful Visitors Center with convenient WCs (daily April-Sept 9:00-19:00, off-season 10:00-18:00, www.abbaye-mont-saint-michel.fr/en). The official TI is on the island (just inside the town gate, daily July-Aug 9:15-19:00, March-June and Sept-Oct 9:15-12:30 & 14:00-18:00, shorter hours off-season; +33 2 33 60 14 30, www.ot-montsaintmichel.com). A post office and ATM are 50 yards beyond the island TI. While either office can inform you about English tour times for the abbey, bus schedules, and tide tables (horaires des marées), the Visitors Center at the parking lot is far less crowded.

Prepare for lots of walking as the island—a small mountain capped by an abbey—is entirely traffic-free. For good explanations of your arrival options by car or train/bus, visit www.accueilmontsaintmichel.fr.

By Bus or Taxi from Pontorson Train Station: The nearest train station is five miles away in Pontorson (called Pontorson/Mont St-Michel). Few trains stop here, and Sunday service is almost nonexistent. Trains are met by buses that take passengers to the foot of the island (€3, 10 buses/day July-Aug, 8/day Sept-June, fewer on Sun, 20 minutes). Or take a taxi to the shuttle stop in the Mont St-Michel parking lot (about €20, €26 after 19:00 and on weekends/holidays; +33 2 33 60 26 89, mobile +33 6 32 10 54 06).

By Bus or Van from Regional Train Stations: Buses connecting with fast trains from Rennes and Dol-de-Bretagne stations drop you near the shuttle stop in the parking lot. From Bayeux, it’s faster by shuttle van.

By Flixbus: Flixbuses from Paris’ Gare de Bercy stop in the huge parking lot near the shuttle stop (at the P7 parking area).

By Car: Day-trippers are directed to a sea of parking (remember your parking-area number). Expect parking jams in high season between 10:00 and noon. To avoid extra walking, take your parking ticket with you and pay at the machines near the visitors center (€15/24 hours—no re-entry, machines take cash and US credit cards, parking +33 2 14 13 20 15). If you arrive after 19:00 and leave before 01:00 that night, the fee is €4.70.

If you’re staying at a hotel on the island or in La Caserne, you’ll receive a parking-gate code from your hotel (ending with “V”). As you approach the parking areas from Bayeux, don’t enter the parking lot at the main entry. Instead, follow wheelchair and bus icon signs until you come to a gate. Those staying on the island turn right here and follow signs for Parking P3 (the parking is close to the shuttle bus). Those staying at the foot of the island in La Caserne should be able to continue straight at the gate (enter your code), then drive right to your hotel (€9 fee). Coming from Pontorson, you’ll reach the wheelchair and bus icons before the main entry—follow these to reach the gate described above. Changes to the parking system are possible—ask when booking your hotel.

From the Parking Lot or La Caserne to the Island: You can either walk (about 50 level and scenic minutes) or pile onto the free and frequent shuttle bus (runs 7:30-24:00, 12-minute trip). The shuttle makes four stops: at the parking lot Visitors Center, in La Caserne village (in front of the Les Galeries du Mont St-Michel grocery), near the dam at the start of the bridge, and at the island end of the bridge, about 200 yards from the island itself. The return shuttle stop is about a hundred yards farther from the island (where the benches start). Most stops are unsigned—sleek wood benches identify the stops. Buses are often crammed. If it’s warm, prepare for a hot (if mercifully short) ride. You can also ride either way in a horse-drawn maringote wagon (€6.50).

Tides: The tides here rise above 50 feet—the largest and most dangerous in Europe. High tides (grandes marées) lap against the island TI door, where you should find tide tables posted (also posted at parking lot visitors center). If you plan to explore the mudflats, it’s essential to be aware of the tides—and be prepared for muddy feet.

Baggage Check: There is no bag check available.

ATM: You’ll find one on the island just after the TI, at the post office.

Taxi: Dial +33 2 33 60 26 89 or +33 2 33 60 26 89.

Guided Abbey Tours: Between the information in this chapter and the tours (and audio tours) available at the abbey, a private guide is not necessary.

Guided Mud Walks: The TI can refer you to companies that run inexpensive guided walks across the bay (with some English).

Crowd-Beating Tips: If you’re staying overnight, arrive after 16:00 and leave by 11:00 to avoid the worst crowds. During the day you can skip the human traffic jam on the island’s main street by following this book’s suggested walking routes (under “Sights in Mont St-Michel”); the shortcut works best if you want to avoid both crowds and stairs. If you’re here from mid-July through August, consider touring the abbey after dinner (it’s open until midnight).

Best Light and Views: Mont St-Michel faces southwest, making morning light along the sleek bridge eye-popping. Early risers win with the best light and the fewest tourists.

After dark, the island is magically floodlit. Views from the ramparts are sublime. But for the best view, exit the island and walk out on the bridge a few hundred yards. This is the reason you came.

Since the sixth century, the vast Bay of Mont St-Michel has attracted hermit-monks in search of solitude. The word “hermit” comes from an ancient Greek word meaning “person of the desert.” The next best thing to a desert in this part of Europe was the sea. Imagine the desert this bay provided as the first monk climbed the rock to get close to God. Add to that the mythic tide, which sends the surf speeding eight miles in and out. Long before the original causeway was built, pilgrims would approach the island across the mudflat, aware that the tide swept in “at the speed of a galloping horse” (well, maybe a trotting horse—12 mph, or about 18 feet per second at top speed).

Quicksand was another peril. A short stroll onto the sticky sand helps you imagine how easy it would be to get stuck as the tide rolled in. The greater danger for adventurers today is the thoroughly disorienting fog and the fact that the sea can encircle unwary hikers. (Bring a mobile phone, and if you’re stuck, dial 112.) Braving these devilish risks for centuries, pilgrims kept their eyes on the spire crowned by their protector, St. Michael, and eventually reached their spiritual goal.

To resurrect that Mont St-Michel dreamscape, it’s possible to walk out on the mudflats that surround the island. At low tide, it’s reasonably dry and an unforgettable experience. But it can be hazardous, so don’t go alone, don’t stray far, and be sure to double-check the tides—or consider a guided walk (details at the TI). You’ll walk on mucky mud and sink in to above your ankles, so wear shorts and go barefoot. Remember the scene from the Bayeux tapestry where Harold rescues the Normans from the quicksand? It happened in this bay.

The island’s main street (Grand Rue), lined with shops and hotels leading to the abbey, is grotesquely touristy. It is some consolation to remember that, even in the Middle Ages, this was a commercial gauntlet, with stalls selling souvenir medallions, candles, and fast food. With only seven full-time residents (not counting a handful of monks and nuns at the abbey), the village lives solely for tourists.

To avoid the crowds, veer left just before the island’s main entry gate and walk under the stone arch of the freestanding building. Follow the cobbled ramp up to the abbey. This is also the easiest route up, thanks to the long ramps, which help you avoid most stairs. To trace the route, see the “Mont St-Michel” map, earlier.

If you opt to trek up through the village on Grand Rue, don’t miss the following stops:

Restaurant La Mère Poulard: Before the drawbridge, on your left, peek through the door of Restaurant La Mère Poulard. The original Madame Poulard (the maid of an abbey architect who married the village baker) made quick and tasty omelets here. These were popular with pilgrims who, back before there was a causeway or bridge, needed a quick meal before they set out to beat the tide. The omelets are still a hit with tourists—even at rip-off prices. Pop in for a minute just to enjoy the show as old-time-costumed cooks beat eggs. (When it comes to the temptation of an omelet on this island, I’d make like a good pilgrim and fast.)

King’s Gate: During the Middle Ages, Mont St-Michel was both a fortress and a place of worship. The abbot was a feudal landlord with economic, political, and religious power. Mont St-Michel was the abbot’s castle as well as a pilgrimage destination. Entering the town, you’ll pass two fortified gates before reaching the actual village gate, the King’s Gate, with its Hollywood-style drawbridge and portcullis. The old door has a tiny door within it, complete with a guard’s barred window (open it). The other gates you passed were added for extra defensive credit. Imagine breaching the first gate and being surrounded by defensive troops. The highest tides bring saltwater inside the lowest gate.

Main Street Tourist Gauntlet: Stepping through the King’s Gate, you enter the old town commercial center. Look back at the City Hall (flying the French flag, directly over the King’s Gate). Climb a few steps and notice the fine half-timbered 15th-century house above on the right. (To skirt the main street crowds, stairs lead from here to the ramparts and on to the abbey—see “Ramparts” under the Abbey listing, later.) Once upon a time this entire lane was lined with fine half-timbered buildings with a commotion of signs hanging above the cobbles. After many fires, the wooden buildings were replaced by stone. As you climb, you’ll see a few stone arches and half-timbered facades that pilgrims also passed by, five centuries ago.

St. Peter’s Church (Eglise St-Pierre): At the top of the commercial stretch (on the left) is St. Peter’s Church. A statue of Joan of Arc (from 1909, when she became a saint) greets you at the door. She’s here because of her association with St. Michael, whose voice inspired her to rally the French against the English. St. Peter’s feels alive (giving a sense of what today’s barren abbey church might once have felt like). The church is dedicated to St. Peter, patron saint of fishermen, who would have been particularly beloved by the island’s parishioners. Tour the small church counterclockwise. Just left of the entry is the town’s only surviving 15th-century stained-glass window. In the far-left rear of the church (past its granite foundation) find the 1772 painting of pilgrims crossing the mudflat under the protection of St. Michael, who seems to be surfing on a devil’s face over a big black cloud. To the right of the main altar lies the headless tomb of a 15th-century noblewoman (notice the empty pillow). During the Revolution heads were lopped off statues like this one, as France’s 99 percent rose up against their 1 percent in 1789. From the center of the altar area, the fine carvings you see on the lectern and tall chairs are the work of prisoners held here during the Revolution. The church offers several Masses (daily at 11:00 and special services for pilgrims).

Pilgrims’ Stairs to the Abbey: A few steps farther up you’ll pass a hostel for pilgrims on the right (Stella Maris, dark-red doors). Reaching the abbey, notice the fortified gate and ramparts necessary to guard the church entry back in the 14th century. Today the abbey, run by just a handful of monks and nuns, welcomes the public.

Mont St-Michel has been an important pilgrimage center since AD 708, when the bishop of Avranches heard the voice of Archangel Michael saying, “Build here and build high.” Michael reassured the bishop, “If you build it...they will come.” Today’s abbey is built on the remains of a Romanesque church, which stands on the remains of a Carolingian church. St. Michael, whose gilded statue decorates the top of the spire, was the patron saint of many French kings, making this a favored site for French royalty through the ages. St. Michael was particularly popular in Counter-Reformation times, as the Church employed his warlike image in the fight against Protestant heresy.

This abbey has 1,200 years of history, though much of its story was lost when its archives were taken to St-Lô for safety during World War II—only to be destroyed during the D-Day fighting. As you climb the stairs, imagine the centuries of pilgrims and monks who have worn down the edges of these same stone steps. Don’t expect well-furnished rooms; those monks lived simple lives with few comforts.

Cost and Hours: €11; May-Aug daily 9:00-19:00, until 24:00 Mon-Sat early July-Aug; Sept-April daily 9:30-18:00; closed Dec 25, Jan 1, and May 1; may close during music festival in late Sept; last entry one hour before closing; allow 20 minutes on foot uphill from the island TI, www.abbaye-mont-saint-michel.fr/en. Mass is held Mon-Sat at 12:00 and Sun at 11:15 (www.abbaye-montsaintmichel.com [URL inactive]).

When to Go: To avoid crowds, arrive before 10:00 or after 16:00 (the place gets really busy by 11:00). In summer, consider a nighttime visit. You’ll enjoy the same access with mood-lighting effects (bordering on cheesy) and no crowds (€15, €13 at TI, early July-Aug Mon-Sat 19:00-24:00, last entry one hour before closing, daytime tickets aren’t valid for re-entry, but you can visit before 19:00 and stay on). The last shuttle bus leaves the island for the mainland parking lot at midnight.

Tours: The excellent audioguide gives greater detail (€3,). You can also take a 1.25-hour English guided tour (free but tip requested, 2-4 tours/day, first and last tours usually around 11:00 and 15:00, confirm times at TI, meet at top terrace in front of church). These tours can be good, but come with big crowds. You can start a tour, then decide if it works for you—but I’d skip it, instead following my directions, next.

Self-Guided Tour: Your visit is a one-way route, so there’s no way to get lost—just follow the crowds. You’ll climb to the ticket office, then climb some more. Along that final stony staircase, monks and nuns (who live in separate quarters on the left) would draw water from a cistern from big faucets on the right. At the top (just past the WC) is a small view terrace, with a much better one just around the corner.

Self-Guided Tour: Your visit is a one-way route, so there’s no way to get lost—just follow the crowds. You’ll climb to the ticket office, then climb some more. Along that final stony staircase, monks and nuns (who live in separate quarters on the left) would draw water from a cistern from big faucets on the right. At the top (just past the WC) is a small view terrace, with a much better one just around the corner.

You’ve climbed the mount. Stop and look back to the church. Now go through the room marked Accueil, with interesting models of the abbey through the ages.

• Emerging on the other side, find your way to the big terrace, walk to the round lookout at the far end, and face the church.

West Terrace: In 1776, a fire destroyed the west end of the church, leaving this unplanned grand view terrace. The original extent of the church is outlined with short walls. In the paving stones, notice the stonecutter numbers, which are generally not exposed like this—a reminder that stonecutters were paid by the piece. The buildings of Mont St-Michel are made of granite stones quarried from the Isles of Chausey (visible on a clear day, 20 miles away). Tidal power was ingeniously harnessed to load, unload, and even transport the stones, as barges hitched a ride with each incoming tide.

As you survey the Bay of Mont St-Michel, notice the polder land—farmland reclaimed by Normans in the 19th century with the help of Dutch engineers. The lines of trees mark strips of land regained in the process. Today, the salt-loving plants covering this land are grazed by sheep whose salty meat is considered a local treat. You’re standing 240 feet above sea level.

The bay stretches from Normandy (on the right as you look to the sea) to Brittany (on the left). The Couesnon River below marks the historic border between the two lands. Brittany and Normandy have long vied for Mont St-Michel. In fact, the river used to pass Mont St-Michel on the other side, making the abbey part of Brittany. Today, it’s just barely—but definitively—on Norman soil. The new dam across this river was built in 2010. Central to the dam is a system of locking gates that retain water upriver during high tide and release it six hours later, in effect flushing the bay and returning sediment to a mudflat at low tide (see the “An Island Again” sidebar, earlier).

• Now enter the...

Abbey Church: Sit on a pew near the altar, under the little statue of the Archangel Michael (with the spear to defeat dragons and evil, and the scales to evaluate your soul). Monks built the church on the tip of this rock to be as close to heaven as possible. The downside: There wasn’t enough level ground to support a sizable abbey and church. The solution: Four immense crypts were built under the church to create a platform to support each of its wings. While most of the church is Romanesque (see the 11th-century round arches behind you), the light-filled apse behind the altar was built later, when Gothic arches were the rage. In 1421, the crypt that supported the apse collapsed, taking that end of the church with it. None of the original windows survive (victims of fires, storms, lightning, and the Revolution).

In the chapel to the right of the altar stands a grim-looking 12th-century statue of St. Aubert, the man with the vision to build the abbey. Directly in front of the altar, look for the glass-covered manhole (you’ll see it again later from another angle). Take a spin around the apse and find the suspended pirate-looking ship.

• Follow Suite de la Visite signs to enter the...

Cloisters: A standard abbey feature, this peaceful zone connected various rooms. Here monks could meditate, read the Bible, and tend their gardens (growing food and herbs for medicine). The great view window is enjoyable today (what’s the tide doing?), but was not part of the original design. The more secluded a monk could be, the closer he was to God. (A cloister, by definition, is an enclosed place.) Notice how the columns are staggered. This efficient design allowed the cloisters to be supported with less building material (a top priority, given the difficulty of transporting stone this high up). Carvings above the columns feature various plants and heighten the cloister’s Garden-of-Eden ambience. The statues of various saints, carved among some columns, were defaced—literally—by French revolutionaries.

• Continue on to the...