Albi • Carcassonne • Collioure

Cathar Sights near Carcassonne

From the 10th to the 13th century, this mighty and independent region controlled most of southern France. The ultimate in mean-spirited crusades against the Cathars (or Albigensians) began here in 1208, igniting Languedoc-Roussillon’s meltdown and eventual incorporation into the state of France.

The name languedoc comes from the langue (language) that its people spoke: Langue d’oc (“language of Oc” or Occitan—Oc for the way they said “yes”) was the dialect of southern France; langue d’oïl was the dialect of northern France (where oïl later became oui, or “yes”). Languedoc-Roussillon’s language faded with its power.

The Moors, Charlemagne, and the Spanish have all called this area home, with the Roussillon part corresponding closely with its Catalan corner, near the border with Spain. The Spanish influence is still muy present, particularly in the south, where restaurants serve paella and the siesta is respected.

While sharing many of the same attributes as Provence (climate, wind, grapes, and sea), this sunny, southwesternmost region of France is allocated little time by most travelers. Lacking Provence’s cachet, sophistication, and tourism, Languedoc-Roussillon (long-dohk roo-see-yohn) feels more real. Pay homage to Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec in Albi; spend a night in Europe’s greatest fortress city, Carcassonne; scamper up to a remote Cathar castle; and sift through sand in Collioure. That wind you feel—la tramontane—is this region’s version of Provence’s mistral wind.

Languedoc-Roussillon is a logical stop between the Dordogne and Provence—or on the way to Barcelona, which is not far over the border.

If you’re driving between the Dordogne and Carcassonne, consider stopping for the day or overnight in Albi, Puycelsi, or St-Cirq-Lapopie (about 1.5 hours from the Dordogne’s Sarlat-le-Canéda). Figure about two autoroute hours from Albi to either the Dordogne or Carcassonne; Puycelsi is 40 minutes closer to the Dordogne. By train, Carcassonne and Albi take about the same travel time from Sarlat-la-Canéda (about 7 hours).

Plan your arrival in popular Carcassonne carefully: Get there late in the afternoon, spend the night, and leave no later than 11:00 the next morning to miss most day-trippers.

Collioure lies a few hours from Carcassonne and is your Mediterranean beach-town vacation from your vacation, where you’ll want two nights and a full day. The most exciting Cathar castles—Peyrepertuse and Quéribus—work well as stops between Carcassonne and Collioure on a scenic drive.

Albi, Carcassonne, and Collioure are accessible by train, but a car is essential for seeing the remote sights. Pick up your rental car in Albi or Carcassonne and buy Michelin maps #344 and #338. Roads can be pencil-thin, and traffic très slow. To find the Cathar castle ruins or the village of Minerve, you’ll need wheels of your own and a good map—or a minivan tour (see here).

If you’re connecting Languedoc with eastern regions like Provence, D-5 between Béziers and Olonzac will escort you between long lines of plane trees and along sections of the Canal du Midi.

For a side trip from Albi, choose from a scenic one-hour detour connecting Albi and points north, or with a bit more time, follow the “Route of the Bastides” (for either, see here). If you really want to joyride, take a half-day drive through the glorious Lot River Valley via Villefranche-de-Rouergue, Cajarc, and St-Cirq-Lapopie (if you’re not overnighting there—see the Dordogne chapter).

Hearty peasant cooking and full-bodied red wines are Languedoc-Roussillon’s tasty trademarks. While the cuisine shares common roots with Provence (olives, olive oil, tomatoes, anchovies, onions, herbs, and garlic), you’ll find a distinctly heartier cuisine in Languedoc-Roussillon. Be adventurous. Cassoulet, an old Roman concoction of goose, duck, pork, mutton, sausage, and white beans, is the main-course specialty. You’ll also see cargolade, a satisfying stew of snail, lamb, and sausage. Local cheeses are Roquefort and Pelardon (a nutty-tasting goat cheese).

Driving through Languedoc-Roussillon reveals how important wine is to the region: Vineyards extend as far as the eye can see. This region is the single biggest wine-producing region in the world, and it accounts for over a third of France’s total wine production. This means that you need to select wines carefully (there are lots that are not good), but there are also plenty of fine needles in this vineyard-haystack.

Corbières, Minervois, and Côtes du Roussillon are the area’s good-value red wines. Syrah, grenache, mourvèdre, and carignan grapes dominate the reds, though the area also produces tasty rosés and some good white wines (made from the picpoul grape, often blended with other southern-French grapes such as bourboulenc, muscat, roussanne, and viognier). You’ll also taste good-value sparkling wines. The town of Limoux is home to a sparkling wine that predates champagne. The local brandy, Armagnac, tastes just like Cognac and costs less.

Albi, an enjoyable river city of sienna-tone bricks, half-timbered buildings, and a marvelous traffic-free center, is worth a stop for two world-class sights: its towering, red-brick cathedral and the Toulouse-Lautrec Museum. Lost in the Dordogne-to-Carcassonne shuffle and overshadowed by its big brother Toulouse, unpretentious yet dignified Albi rewards the stray tourist well. For most, Albi works best as a day stop, though some will be smitten by its charm and lured into spending a night.

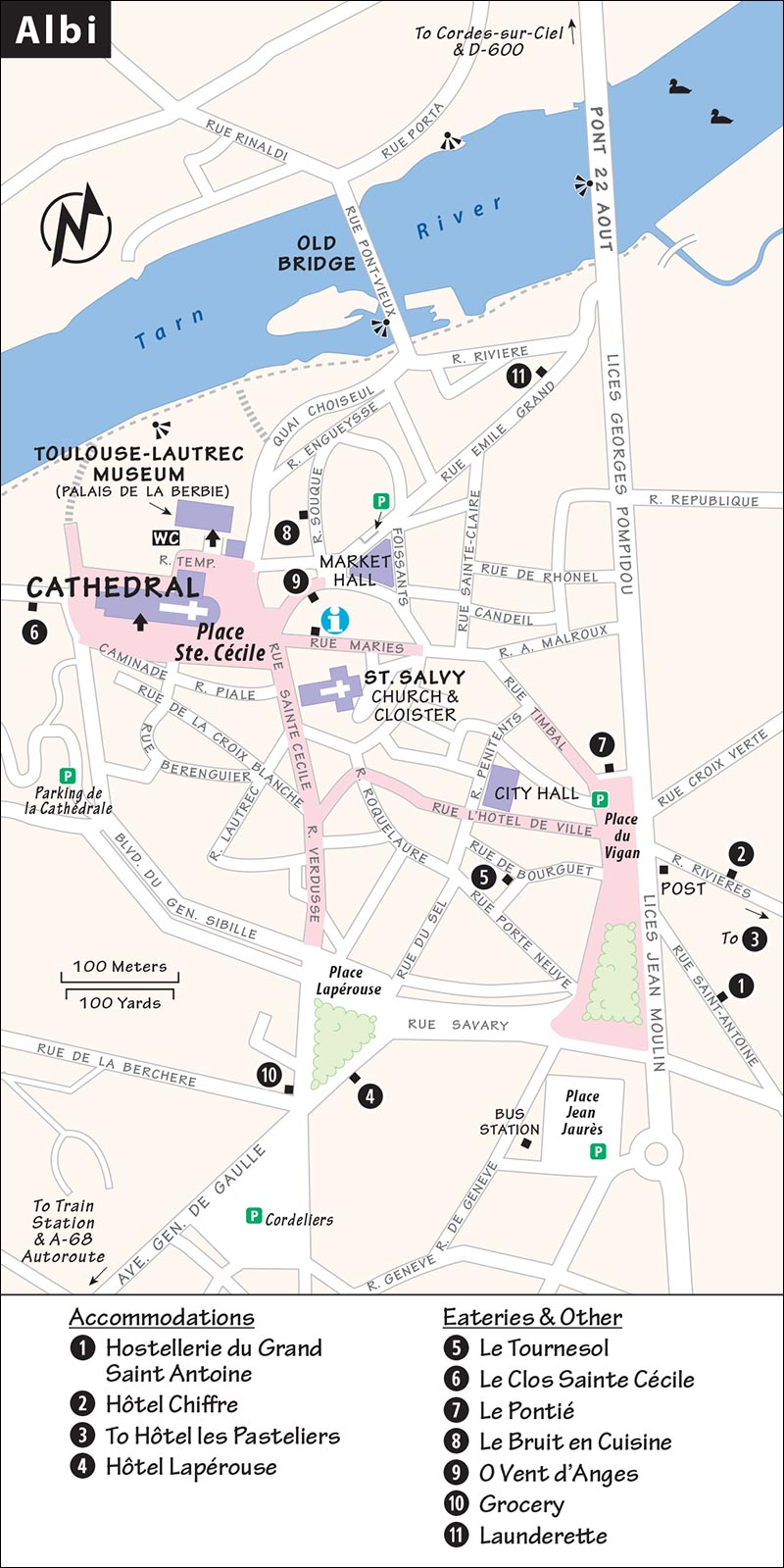

Albi’s cathedral is home base. For our purposes, this is the city center—all sights, pedestrian streets, and hotels fan out from here and are less than a 10-minute walk away. The Tarn River hides below and behind the cathedral. The best city view is from the 22 Août 1944 bridge. Albi is dead quiet on Sundays and Monday mornings.

The main TI is across the square from the cathedral, at 42 Rue Mariès (daily 9:30-18:00, shorter hours Nov-Feb; +33 5 63 36 36 00, www.albi-tourisme.fr). The TI sells a worthwhile combo-ticket that includes the Toulouse-Lautrec museum and the cathedral choir for €13 (saves €2). Ask about concerts in the cathedral and pick up two maps: one of the city center with walking tours, and the map of La Route des Bastides Albigeoises (hill towns near Albi).

By Train: There are two stations in Albi; you want Albi-Ville. It’s a level 15-minute walk to the town center: Exit the station, take the second left onto Avenue Maréchal Joffre, and then take another left on Avenue du Général de Gaulle. Go straight across Place Lapérouse and find the traffic-free street to the left that leads into the city center. This turns into Rue Ste. Cécile, the main shopping street that takes you to my recommended hotels and the cathedral.

By Car: Follow Centre-Ville and Cathédrale signs (if you lose your way, follow the tall church tower). Some sections of the surface-level Parking de la Cathédrale are free (on Boulevard Sibille); reasonably priced pay garages are under the market hall (Marché Couvert) and Place du Vigan. If you find a spot on the street, note that parking meters are free between 12:00-14:00 and 19:00-8:00—as well as all day Sunday; otherwise pay by the hour.

Market Days: The beautiful Art Nouveau market hall, a block past the cathedral square, hosts a market daily except Monday (7:00-14:00). On Saturday mornings, a lively farmers market gathers around the market hall and the TI.

Supermarkets: Carrefour City is across from the recommended Hôtel Lapérouse (long hours, 14 Place Lapérouse). There’s also a grocery at the market hall in the city center.

Baggage Storage: The Toulouse-Lautrec Museum has lockers accessible during the museum’s open hours. You can also arrange baggage storage online at Eelway.com.

Laundry: Do your washing at Lavomatique, above the river at 10 Rue Emile Grand (daily 7:00-21:00).

Taxi: Call Albi Taxi Radio (mobile +33 6 12 99 42 46).

Tourist Train: The petit train leaves from Place Ste. Cécile in front of the cathedral and makes a 45-minute scenic loop around Albi (€8, daily in high season).

Everything of sightseeing interest is within a few blocks of the towering cathedral. (I’ve included walking directions to connect some of the key sights.) Get oriented in the main square (see map).

Grab the lone bench or a café table on the far side of Place Ste. Cécile. With the church directly in front of you, the bishop’s palace (with the Toulouse-Lautrec Museum inside) is a bit to the right. The TI is hard on your right, and the market hall is a block behind it.

Why the big church? At its peak, Albi was the administrative center for 465 churches. Back when tithes were essentially legally required taxes, everyone gave their 10 percent, or “dime,” to the church. The local bishop was filthy rich, and with all those dimes, he had money to build a dandy church. In medieval times, there was no interest in making a space so people could step back and get a perspective on such a beautiful building. A clutter of houses snuggled right up to the church’s stout walls, and only in the 19th century were things cleared away. (Just in the past few years the cars were also cleared out.)

Why so many bricks? Because there were no stone quarries nearby. Albi is part of a swath of red-brick towns from here to Toulouse (nicknamed “the pink city” for the way its rosy bricks dominate that townscape). Notice on this square the buffed brick addresses next to the sluggish stucco ones. As late as the 1960s, the town’s brickwork was considered low-class and was covered by stucco. Today, the stucco is being peeled away, and Albi has that brick pride back.

When the heretical Cathars were defeated in the 13th century, this massive cathedral was the final nail in their coffin. Big and bold, it made it clear who was in charge. The imposing exterior and the stunning interior drive home the message of the Catholic (read: “universal”) Church in a way that would have stuck with any medieval worshipper. This place oozes power—get on board, or get run over.

Cost and Hours: It’s free to enter the church (daily 9:00-18:30 except Nov-April closed 13:15-14:00). Once inside, you’ll pay €6 to visit the choir (includes excellent audioguide describing art throughout the church, open daily from 9:30 except Sun when it closes from 10:15 until Mass is over—usually 14:00, last entry one hour before the church closes). The treasury (a single room of reliquaries and church art) isn’t worth the entry fee or the climb.

Organ Concerts: From mid-July to mid-August, concerts are held at the cathedral at 16:00 on Wed and Sun, and sometimes at St. Salvy Church on Wed (ask TI for schedule).

Self-Guided Tour: Visit the cathedral using the following commentary, which you can supplement with an excellent audioguide (it’s especially good if you want to know more about the church’s Last Judgment mural; pick it up as you enter the choir).

Self-Guided Tour: Visit the cathedral using the following commentary, which you can supplement with an excellent audioguide (it’s especially good if you want to know more about the church’s Last Judgment mural; pick it up as you enter the choir).

• Begin facing the...

Exterior: The cathedral looks less like a church and more like a fortress, as it was a central feature of the town’s defensive walls. Notice how high the windows are (out of stone-tossing range). The simple Gothic style was typical of this region—designed to be sensitive to the antimaterialistic tastes of the local Cathars.

The top (from the gargoyles and newer, brighter bricks upward) is a fanciful, 19th-century, Romantic-era renovation. The church was originally as plain and austere as the bishop’s palace (the similar, bold brick building to the right). Imagine the church with a rooftop more like that of the bishop’s palace.

• Walk to the bottom of the cathedral’s steps and gaze up at the extravagant Flamboyant Gothic...

Entry Porch: The entry was built about two centuries after the original plain church (1494), when concerns about Cathar sensitivities were long passé. Originally colorfully painted, it provided one fancy entry.

• Head into the cathedral’s...

Interior: The inside of the church—also far from plain—looks essentially as it did in 1500. The highlights are the vast Last Judgment mural (west wall, under the organ) and the ornate choir (east end).

• Walk toward the front of the altar and find a good spot to view the...

Last Judgment Mural: The oldest art in the church (1474), this is also the biggest Last Judgment painting from the Middle Ages. The dead come out of the ground, then line up (above) with a printed accounting of their good and bad deeds displayed in ledgers on their chests. Judgment, here we come. Those on the left (God’s right) look cocky and relaxed. Those on the right—the hedonists—look edgy. The assembly above the risen dead (on the left) shows the heavenly hierarchy: The pope and bishops sit closest to the center; then more bishops and priests—before kings—followed by monks; and then, finally, commoners like you and me.

Get closer. Inspect both sides of the arch to find seven frames illustrating a wonderland of gruesome punishments that sinners could suffer through while attempting to earn a second chance at salvation. Those who fail end up in the black clouds of hell (upper right).

But where’s Jesus—the key figure in any Judgment Day painting? The missing arch in the middle (cut out in late Renaissance times to open the way to a new chapel) once featured Christ overseeing the action. A black-and-white image near the first pew (as you enter the church) provides a good guess at how this painting would have looked—though no one knows for sure.

The altar in front of the Last Judgment is the newest art in the church. But this is not the front of the church at all—the altar is to the west. Turn 180 degrees and head east, for Jerusalem (where most medieval churches point).

• Stop in front of the choir—a fancy, more intimate room within the finely carved stone “screen.” Find the desk selling tickets to the choir and pick up the included audioguide.

Choir of the Canons: In the Middle Ages, nearly all cathedrals had ornate Gothic choir screens like this one. These highly decorated walls divided the church into a private place for clergy and a general zone for the common rabble. The screen enclosed the altar and added mystery to the Mass. In the 16th century, with the success of the Protestant movement and the Catholic Church’s Counter-Reformation, choir screens were removed. (In the 20th century, the Church took things one step further, and priests actually turned and faced their parishioners.) Later, French Revolution atheists destroyed most of the choir screens that remained—Albi’s is a rare survivor.

Follow the plan (in English) as you stroll around the choir. You’ll see colorful Old Testament figures along the Dark Ages exterior columns and New Testament figures in the enlightened interior. Stepping inside the choir, marvel at the fine limestone carving. Scan each of the 72 unique little angels just above the wood-paneled choir stalls. Check out the brilliant ceiling, which hasn’t been touched or restored in 500 years. A bishop, impressed by the fresco technique of the Italian Renaissance, invited seven Bolognese artists to do the work. Good call.

• Exit the cathedral through the side door, next to where you paid for the choir. You’ll pass a WC on your way to the...

The Palais de la Berbie (once the fortified home of Albi’s archbishop) has the world’s largest collection of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec’s paintings, posters, and sketches.

Cost and Hours: €10, mid-June-Sept daily 9:00-18:00; otherwise daily 10:00-12:00 & 14:00-18:00 except closed Tue Oct-March; audioguide-€4 (for most, the printed English explanations in most rooms are sufficient), lockers available, on Place Ste. Cécile.

Information: +33 5 63 49 48 70, www.musee-toulouse-lautrec.com.

Background: Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, born in Albi in 1864, was crippled from youth. After he broke his right leg at age 13 and then his left leg the next year (probably due to a genetic disorder), the lower half of his body stopped growing. His father, once very engaged in parenting, lost interest in his son. Henri moved to the fringes of society, where he gained an affinity for people who didn’t quite fit in. He later made his mark painting the dregs of the Parisian underclass with an intimacy only made possible by his life experience.

Visiting the Museum: From the turnstile, walk down a few steps and enter the main floor collection.

The first room is filled with intriguing portraits of Toulouse-Lautrec painted by artists on whom he made an impact. There’s also a rare self-portrait on display.

In the next sections we see his earliest classical paintings (of horses and pets) and his boyhood doodles. Find the dictionary he scribbled all over as a schoolkid. In the 1880s, Henri was stuck in Albi, far from any artistic action. During these years, he found inspiration in nature, in the pages of magazines, and by observing people. This was his Impressionistic stage.

Next, go down a few more steps to see some of his first portraits of family and friends, most done in an Impressionist style.

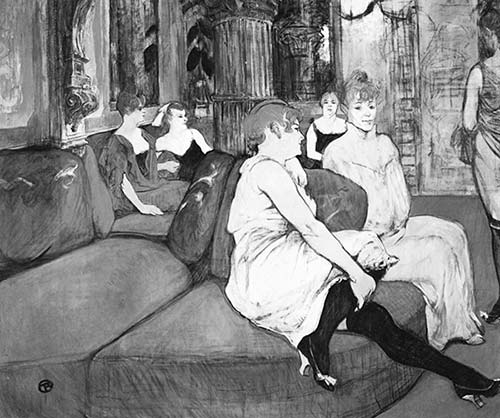

Step into the next room for his most famous stuff: paintings of the prostitutes and brothels of Paris. In 1882, Henri moved to the big city to pursue his passion. In these early Paris works, we see his trademark shocking colors, and down and dirty street-life scenes emerge. Compare his art-school work and his street work: Henri augmented his classical training with vivid life experience. His subjects were from bars, brothels, and cabarets...Toto, we’re not in Albi anymore. In these exploratory years, he dabbled in any style he encountered. The naked body emerged as one of his fascinations.

Henri started making money in the 1890s by selling illustrations to magazines and newspapers. Back then, his daily happy hour included brothel visits—1892-1894 was his prostitution period. He respected the women, feeling both fascination and empathy toward them. The prostitutes accepted him the way he was and let him into their world...which he sketched brilliantly. He shows these sex workers as real humans—they are neither glorified nor vulgarized in his works.

At the far end of this room, notice the big Au Salon de la Rue des Moulins (1894). There are two versions: the quick sketch, then the finished studio version. With this piece, Toulouse-Lautrec arrived—no more sampling. The artist has established his unique style, oblivious to society’s norms: colors (strong), subject matter (society’s underbelly), and moralism (none). Henri’s trademark use of cardboard was simply his quick, snapshot way of working: He’d capture these slice-of-life impressions on the fly on cheap, disposable material, intending to convert them to finer canvas paintings later, in his studio. But the cardboard quickies survive as Toulouse-Lautrec masterpieces.

Spiral up two flights through a room showing off a rare, 13th-century terra-cotta tile floor original to the building. Enter the next room on the left to find Lautrec’s famous advertising posters, which were his bread and butter. He was an innovative advertiser, creating simple, bold, and powerful lithographic images. Look for displays of his original lithograph blocks (simply prepare the stone with a backward image, apply ink—which sticks chemically to the black points—and print posters). Four-color posters meant creating four different blocks. Many of the displayed works show different stages of the printing process—first with black ink, then the red layer, then the finished poster. The Moulin Rouge poster established his business reputation in Paris—strong symbols, bold and simple: just what, where, and when. Across the room, cabaret singer and club owner Aristide Bruant (dans son cabaret—“in his cabaret”) is portrayed as bold and dashing.

The next room has more advertising posters, several featuring the dancer Jane Avril. Henri was fascinated by cancan dancers (whose legs moved with an agility he’d never experience), and he captured them expertly. Next, continue through several more rooms with more posters (check out those lips on Yvette Guilbert), portraits of Parisian notables and misfits, and finally the darker works he painted before his death.

One thing you will not see (because it’s away on loan) is Toulouse-Lautrec’s cane, which offers more insight into this tortured artistic genius. To protect him from his self-destructive lifestyle, loved ones had him locked up in a psychiatric hospital. But, with the help of this clever hollow cane, he still got his booze. Friends would drop by with hallucinogenic absinthe, his drink of choice—also popular among many other artists of the time. With these special deliveries, he’d restock his cane, which even came equipped with a fancy little glass.

In 1901, at age 37, alcoholic, paranoid, depressed, and syphilitic, Toulouse-Lautrec returned to his mother—the only woman who ever really loved him—and died in her arms. The art world didn’t mourn. Obituaries, speaking for the art establishment, said good riddance to Toulouse-Lautrec and his ugly art. Although no one in the art world wanted Henri’s pieces, his mother and his best friend—a boyhood pal and art dealer named Maurice Joyant—recognized his genius and saved his work. They first offered it to the Louvre, which refused. Finally, in 1922, the mayor of Albi accepted the collection and hung Toulouse-Lautrec’s work here in what had previously been a sleepy museum of archaeology.

Your visit continues with a few rooms showing off the one-time grandeur of the Palais de la Berbie and two captivating paintings by 17th-century master Georges de La Tour.

If you still have stamina, you can climb up to the next floor, with a good exhibit of modern art. You’ll see works by Toulouse-Lautrec’s classmates and contemporaries, including paintings by Matisse, Degas, Brayer, and Vuillard.

• Leaving the museum, curl around to the right, following the hulking building to find a gorgeous garden overlooking a fine...

Albi is here because of its river access to Bordeaux (which connected the town to global markets). In medieval times, the fastest, most economical way to transport goods was down rivers like this. The lower, older bridge (Pont Vieux) was first built in 1020. Prior to its construction, the weir (look just beyond this first bridge) provided a series of stepping-stones that enabled people to cross the river. The garden of the bishop’s palace dates from the 17th century (when the palace at Versailles inspired the French to create fancy gardens). The palace grew in importance from the 13th century until 1789, when the French Revolution ended the power of the bishops, and the state confiscated the building. Since 1905, it’s been a museum.

• The last two sights are in the town center, roughly behind the cathedral.

Although this church (the oldest in town) is nothing special, the cloister creates a delightful space embracing an ancient well (now planted) and modern garden. Find the easy-to-miss entrance on the main shopping street, Rue Ste. Cécile, a block off the main square. Delicate arches surround an enclosed courtyard, providing a peaceful interlude from the shoppers that fill the pedestrian streets. Notice the church wall from the courtyard. It was the only stone building in Albi in the 11th century; the taller parts, added later, are made of brick.

This is one of many little hidden courtyards in Albi. In the rough-and-tumble Middle Ages, most buildings faced inward. If doors are open, you’re welcome to pop in to courtyards.

• Leave the cloister, go up the steps, and find a sweet square with quiet cafés.

Albi’s elegant Art Nouveau market is good for picnic-gathering and people-watching. There are fun lunch counters on its main floor and a grocery store on the lower level (Tue-Sun 7:00-14:00, closed Mon, 2 blocks from cathedral). On Saturdays, a lively farmers market sets up outside the market hall.

These hotels do not have elevators unless noted.

$$ Hostellerie du Grand Saint Antoine**** is Albi’s oldest hotel (established in 1784) and the most traditional place I list. Guests enter an inviting, spacious lobby that opens onto an enclosed garden. Some of the 44 rooms are Old World cozy, while others have a modern flair (great breakfast, elevator, private pay parking, a block above big Place du Vigan at 17 Rue Saint-Antoine, +33 5 63 54 04 04, www.hotel-saint-antoine-albi.com, courriel@hotel-saint-antoine-albi.com).

$$ Hôtel Chiffre*** is a modern and impersonal place, with 38 simple yet comfortable rooms (elevator, pay parking garage, near Place du Vigan at 50 Rue Séré de Rivières, +33 5 63 48 58 48, www.hotelchiffre.com, hotel.chiffre@yahoo.fr).

$ Hôtel les Pasteliers** is a cool, homey place with appealing lounges, a service-oriented owner, and simple-yet-comfortable rooms with air-conditioning at terrific prices (pay secured parking, 3 Rue Honoré de Balzac, +33 5 63 54 26 51, www.hotellespasteliers.com, contact@hotellespasteliers.com).

$ Hôtel Lapérouse** is one block from the old city and a 10-minute walk to the train station. This family-run hotel offers 24 modest rooms and enthusiastic owners, Quentin and Christèle. Spring for one of the two rooms with a balcony over the big pool and quiet garden where picnics and aperitifs are encouraged (air-con, reception closed 12:00-15:00 and after 20:00, 21 Place Lapérouse, +33 5 63 54 69 22, www.hotel-laperouse.com, contact@hotel-laperouse.com).

Albi is filled with reasonable restaurants that serve a meaty local cuisine, including plenty of duck dishes. If you’re adventurous, search out these local specialties: tripe (cow intestines), andouillette (sausages made from pig intestines), foie de veau (calf liver), and tête de veau (calf’s head). Besides the restaurants listed below, there are many tempting cafés on the squares behind St. Salvy’s cloister and in front of the market hall.

$ Le Tournesol is a good (primarily lunch) option for vegetarians, since that’s all they do. The food is delicious (vegan options available), the setting is bright with many windows and a good terrace, and the service is friendly. Try the wonderful homemade tarts (open Tue-Sat for lunch, dinner Fri and some Sat in high season, 11 Rue de l’Ort en Salvy, +33 5 63 38 38 14).

$ Le Clos Sainte Cécile, a short block behind the cathedral, is an old-school place (literally and figuratively) transformed into a delightful family-run restaurant with a charming courtyard laced with cheery lights and covered with umbrellas. Friendly waiters serve regional dishes including good salads, confit de canard, and foie gras (closed Tue-Wed, 3 Rue du Castelviel, +33 5 63 38 19 74).

$ Le Pontié is Albi’s go-to brasserie with a big selection (pizza, salads, plats, and such) and a large terrace. Interior seating is pleasant, and prices are fair (daily, Place du Vigan, +33 5 63 54 16 34).

$$ Le Bruit en Cuisine offers refined food that blends the modern with the traditional. Interior tables are OK, but you’ll have a spectacular view of the cathedral (and catch a memorable sunset) from the broad, lamp-lit terrace (lunch menu based on market of the day, evening menu with good choices, reservations recommended, closed Sun-Mon, 22 Rue de la Souque, +33 5 63 36 70 31).

$ O Vent d’Anges, on the market hall square, is Albi’s happening wine bar-café, with tables sprawling over several terraces. It’s good for an evening aperitif or small plates that can make a meal. Big tasty salads and a delicious house burger are served during lunch only (closed Mon, 9 Place St-Julien, +33 5 81 02 62 33).

You’ll connect to just about any destination through Toulouse.

From Albi by Train to: Toulouse (hourly, 70 minutes), Carcassonne (hourly, 2.5 hours, change in Toulouse), Sarlat-la-Canéda (6/day, 5-8 hours with 2-3 changes), Paris (6/day, 6 hours, change in Toulouse or Montauban; also a night train with change in Toulouse—may not run every day).

The hilly terrain north of Albi was tailor-made for medieval villages to organize around for defensive purposes. Here, along the Route of the Bastides (La Route des Bastides Albigeoises), scores of fortified villages (bastides) spill over hilltops, above rivers, and between wheat fields, creating a ▲ detour for drivers. These planned communities were the medieval product of community efforts organized by local religious or military leaders. Most bastides were built during the Hundred Years’ War (see sidebar on here) to establish a foothold for French or English rule in this hotly contested region, and to provide stability to benefit trade. Unlike other French hill towns, bastides were not safe havens provided by a castle. Instead, they were a premeditated effort by a community to collectively construct houses as a planned defensive unit, sans castle.

Connect these bastides as a day trip from Albi, or as you drive between Albi and the Dordogne. I’ve described the top bastides in the order you’ll reach them on these driving routes.

Day Trip from Albi: For a good 80-mile loop route northwest from Albi, cross the 22 Août 1944 bridge and follow signs to Cordes-sur-Ciel (the loop without stops takes about 2.5 hours). The view of Cordes as you approach is memorable. From Cordes, follow signs to Saint-Antonin-Noble-Val, an appealing, flat “hill town” on the river, with few tourists. Then turn south and west past vertical little Penne, Bruniquel (signed from Saint-Antonin-Noble-Val), Larroque, Puycelsi (my favorite), and, finally, Castelnau-de-Montmiral (with a lovely main square), before returning to Albi. Each of these places is worth exploring if you have the time.

On the Way to the Dordogne: For a one-way scenic route north to the Dordogne that includes many of the same bastides, leave Albi, head toward Toulouse, and make time on the free A-68. Exit at Gaillac, go to its center, and track D-964 to Castelnau-de-Montmiral, Puycelsi, and on to Bruniquel. From here you can head directly to Caussade on D-115 and D-964, then hop on the A-20 northbound (toward Cahors/Paris); from here, exits for Cahors, St-Cirq-Lapopie, Rocamadour, and Sarlat-la-Canéda are all well marked.

It’s hard to resist this brilliantly situated hill town about 20 miles north of Albi, but I would (in high season, at least). Enjoy the fantastic view on the road from Albi and consider a detour up into town only if the coast looks clear (read: off-season). Cordes, once an important Cathar base, has slipped over the boutique-filled edge to the point where it’s hard to find the medieval town under the all the shops. But it’s dramatically set, boasting great views and filled with steep streets and beautiful half-timbered buildings (TI: +33 5 63 56 00 52, www.cordessurciel.fr).

This overlooked, très photogenic, but less-tended village will test your thighs as you climb the lanes upward to the Châteaux de Bruniquel (small fee, daily 10:00-18:00, July-Aug until 19:00, closed Nov-Feb). Don’t miss the dramatic view up to the village from the river below as you drive along D-964 (about an hour northwest of Albi).

Forty minutes north of Albi, this town crowns a high bluff overlooking thick forests and sweeping pastures. Drive to the top (passing a signed, lower lot) to find parking and an unspoiled, level village with a couple of cafés, a bistro with a view, small grocery, bakery, a few chambres d’hôtes, and one sharp little hotel.

From the parking lot, pass the Puycelsi Roc Café and make your way through town. Appreciate the fine collection of buildings with lovingly tended flowerbeds. At the opposite side of the village, a rampart walk yields fine views, reminding us of the village’s history as a bastide. The parklike ramparts near the parking area come with picnic benches, grand vistas (ideal at sunset), and a WC. It’s a good place to listen to the birds and feel the wind.

As you wander, consider the recent history of an ancient town like this. In 1900, 2,000 people lived here with neither running water nor electricity. Then things changed. Millions of French men lost their lives in World War I; Puycelsi didn’t escape this fate, as the monument (by the parking lot) attests. World War II added to the exodus and by 1968 the village was down to three families. But then running water replaced the venerable cisterns, and things started looking up. Today, there is just enough commercial activity to keep locals happy. The town has a stable population of 110, all marveling at how lucky they are to live here.

Sleeping in Puycelsi: An overnight here is my idea of vacation. Church bells keep a vigil, ringing on the hour throughout the night.

$$ L’Ancienne Auberge is the place to sleep, with eight surprisingly smart and comfortable rooms, some with sublime views. Owner/chef Dorothy moved here from New Jersey many moons ago and is eager to share her passion for this region (air-con in some rooms, Place de l’Eglise, +33 5 63 33 65 90, www.ancienne-auberge.com, contact@ancienne-auberge.com). Ask about their self-catering apartments that can accommodate up to five people, and consider dinner at their view bistro Jardin de Lys (described below).

$ Delphine de Laveleye Chambres is another great choice just behind L’Ancienne Auberge. Warm Delphine and her dogs fill a cave-like, 17th-century house with a variety of rooms, ranging from a small romantic room for two to a three-bedroom suite with a kitchen, all hovering above a small garden and pool (family rooms, cash only, +33 5 63 33 13 65, mobile +33 6 72 92 69 59, delphine@chezdelphine.com).

Eating in Puycelsi: The $$ Jardin de Lys bistro-café clings to the hillside, offering breathtaking views and all-day service. Come for a drink at least, or, better, for dinner based on original recipes and cooked with fresh products (closed Mon-Tue, +33 5 63 60 23 55). $ Puycelsi Roc Café, at the parking lot, has good café fare at very reasonable prices, a warm interior, and pleasant outdoor tables (daily for lunch and dinner in high season, +33 5 63 33 13 67).

This overlooked village (30 minutes northwest of Albi) has quiet lanes leading to a perfectly preserved bastide square surrounded by fine arcades and filled with brick half-timbered facades. Ditch your car below and wander up to the square, where a TI, restaurant, café, and small pâtisserie await. Have a drink or lunch on the square.

Medieval Carcassonne is a 13th-century world of towers, turrets, and cobblestones. Europe’s ultimate walled fortress city, it’s also stuffed with tourists. At 10:00, salespeople stand at the doors of their main-street shops, a gauntlet of tacky temptations poised and ready for their daily ration of customers—consider yourself warned. But early, late, or off-season, a quieter Carcassonne is an evocative playground for any medievalist. Forget midday—spend the night. In fact, this is one city that can be well seen with a late afternoon arrival. There’s only one “sight” to enter, and the majesty of the place is best enjoyed after-hours.

Locals like to believe that Carcassonne got its name this way: 1,200 years ago, Charlemagne and his troops besieged this fortress-town (then called La Cité) for several years. A cunning townsperson named Madame Carcas saved the town. Just as food was running out, she fed the last few bits of grain to the last pig and tossed him over the wall. Splat. Charlemagne’s bored and frustrated forces, amazed that the town still had enough food to throw fat party pigs over the wall, decided they would never succeed in starving the people out. They ended the siege, and the city was saved. Madame Carcas sonne-d (sounded) the long-awaited victory bells, and La Cité had a new name: Carcas-sonne.

It’s a good story...but historians suspect that Carcassonne is a Frenchified version of the town’s original name (Carcas). As a teenage backpacker on my first visit to Carcassonne, I wrote this in my journal: “Before me lies Carcassonne, the perfect medieval city. Like a fish that everyone thought was extinct, somehow Europe’s greatest Romanesque fortress city has survived the centuries. I was supposed to be gone yesterday, but here I sit imprisoned by choice—curled in a cranny on top of the wall. The wind blows away the sounds of today, and my imagination ‘medievals’ me. The moat is one foot over and 100 feet down. Small plants and moss upholster my throne.”

More than 40 years later, on my most recent visit, Carcassonne “medievaled” me just the same. Let this place make you a kid on a rampart, too.

Contemporary Carcassonne is neatly divided into two cities: the magnificent La Cité (the fortified old city, with 200 full-time residents taking care of lots more tourists) and the lively Ville Basse (modern lower city). Two bridges, the busy Pont Neuf and the traffic-free Pont Vieux, both with great views, connect the two parts. The train station is separated from Ville Basse by the Canal du Midi.

The main TI, in Ville Basse, is useful only if you’re walking to La Cité (28 Rue de Verdun). A far more convenient branch is in La Cité, a block to your right (on Impasse Agnès de Montpellier) after entering the main gate (Narbonne Gate—or Porte Narbonnaise). Both TIs have similar hours (July-Aug daily 9:00-19:00; April-June and Oct Mon-Sat 9:00-18:00, Sun 10:00-13:00; Nov-March daily 9:30-12:30 & 13:30-17:30; +33 4 68 10 24 30, www.tourisme-carcassonne.fr).

At either TI, pick up a map of La Cité and the excellent (and free) Walks booklet that includes biking ideas. Ask about walking tours of La Cité or rent their €3 audioguide for a self-guided tour (or follow my tour later in this section).

By Train: The train station is in Ville Basse, a 30-minute walk from La Cité. The nearest pay baggage storage is a few blocks away (at the recommended Hôtel Astoria). You have three basic options for reaching La Cité: taxi, bus, or on foot.

Taxis charge €12 for the short trip to La Cité but cannot enter the city walls. Taxis usually wait in front of the train station.

Two cheaper options run to La Cité from the Chénier stop (on Boulevard Omer Sarraut, at the far edge of the park a block from the station): public bus #4 (€1, hourly Mon-Sat, none Sun) and the rubber-tired train-bus (€2 one-way, €3 round-trip, hourly 11:00-19:00, daily June-Aug, Mon-Sat only Sept-mid-Oct, no service mid-Oct-June). Schedules for both are posted in the bus shelter.

An airport bus departs from in front of the station to Carcassonne’s airport, scheduled to coincide with departing flights (€6); most departures also stop at La Cité en route. A taxi to the airport costs around €20.

The 30-minute walk through Ville Basse to La Cité ends with a good uphill climb. Walk straight out of the station, cross the canal, then follow the route shown on the “Carcassonne Overview” map in this chapter (starting up Rue Clemenceau). La Cité is signposted.

By Car: Follow signs to Centre-Ville, then La Cité. You’ll come to a drawbridge at the Narbonne Gate, the walled city’s main entrance, where day-trippers will find several huge public pay lots (about €10/6 hours). Free parking can be found below on both sides of the river, but it’s more plentiful on the Ville Basse side (along the river just north of the Pont Neuf or along Quai Bellevue; see the “Carcassonne Overview” map). Leave nothing of value in your car; theft is common in public lots. Allow 15 minutes on foot over uneven surfaces to hotels in La Cité.

Market Days: Pleasing Place Carnot in Ville Basse hosts a thriving nontouristy open market (Tue, Thu, and Sat mornings until 13:00; Sat is the biggest and worth the detour).

Supermarkets: There’s a small one in the train station. You’ll also find a Monoprix department store (with a grocery section) where Rue Clemenceau and Rue de la République cross, a few blocks from the train station.

Summer Festivals: Carcassonne becomes colorfully medieval during many special events each July and August. Highlights are the spectacle équestre (jousting matches) and July 14 (Bastille Day) fireworks. The TI has details on these and other events.

Laundry: Try Laverie Express (daily 8:00-22:00, 5 Square Gambetta at Hôtel Ibis; from La Cité, cross Pont Vieux and turn right).

Bike Rental: Bike riding is very popular thanks to the scenic towpath that follows the canal (start at the train station). Ask at the TI for bike rental locations.

Taxi: Dial +33 4 68 71 50 50.

Car Rental: The airport has all the rental companies but is 30 minutes from Carcassonne.

Guided Excursions in and from Carcassonne: Vin en Vacances offers city walks of Carcassonne (€40/person) and daylong vineyard tours that mix wine tasting with local food, sightseeing, and cultural experiences. They’re run by charming Wendy Gedney and her terrific team, all of whom have excellent knowledge of the region and its wines. Tours include stops at two wineries, lunch, and visits to key sights such as the Cathar castles (€125-€145/person, see website for other tour options, mobile +33 6 42 33 34 09, www.vinenvacances.com [URL inactive]).

Minivan Service: Friendly Didier provides comfortable transportation for up to eight passengers to the village of Minerve, all area châteaux and sights, airports, and hotels. He’s not a guide and speaks just enough English (for 4 passengers plan on about €240/half-day, €420/day, €30-40/person for the Châteaux of Lastours; bike transport also possible; mobile +33 6 03 18 39 95, www.catharexcursions.com, bod.aude11@orange.fr).

Tourist Train or Horse Carriage: You have two options for taking a 20-minute loop around La Cité in high season (both cost €8 and begin at the Narbonne Gate): The tourist train has headphone English commentary and loops outside the wall, while the horse-and-carriage ride is in French and clip-clops between the two walls.

Cooking Classes: Brit Heather Hayes and Aussie David Crago offer a full-day classic French cooking class in a fun, relaxed atmosphere at a working farm and wine domaine just 50 yards from the Canal du Midi and eight miles from Carcassonne. Up to eight cooks can learn to prepare savory soufflés, duck, quail, fish or guinea fowl, classic French sauces, and delicious desserts, then enjoy a traditional three-course canalside lunch. Companions are welcome to observe and join for lunch (€110/person, €40/companion, 29 Domaine de Millepetit, Trèbes, mobile +33 6 51 63 29 04, www.canaldumidicooking.com).

While the tourists shuffle up the main street, this self-guided walk, rated ▲▲▲, introduces you to the city with history and wonder, rather than tour groups and plastic swords. We’ll sneak into the town on the other side of the wall...through the back door (see the “Carcassonne’s La Cité” map). This walk can be done at any hour. It’s wonderfully peaceful and scenic early or late in the day, when the sun is low (but the church and castle may be closed).

• Start on the modern asphalt 20 steps outside La Cité’s main entrance, the Narbonne Gate (Porte Narbonnaise). Pause a moment to simply take in Europe’s best-preserved fortress city.

La Cité: On the pillar to the right of the gate, you’re welcomed by a 12-foot-tall, contemporary-looking bust of Madame Carcas—which is modeled after a 16th-century original of the town’s legendary first lady (for her story, see here). This relates to a ninth-century siege, during the days of Charlemagne.

But, when you gaze at the awe-inspiring turrets and ramparts of La Cité (as old Carcassonne is called), you’re really looking at an edifice from the 13th-century crusade of the king of France and the pope against the heretical Cathars (see “The Cathars” sidebar, earlier). Back then, the notion of a Paris-centered France was a dream and far from reality. This independently minded region was essentially a different country whose inhabitants spoke a different language (Occitan). It sympathized with the Cathar movement, and Carcassonne was one of its leading cities. This was an age when defenses were better than offenses, and this strategic headquarters employed state-of-the-art fortifications.

• Cross the bridge toward the...

Narbonne Gate: Pause at the drawbridge and survey this immense fortification. When forces from northern France finally conquered Carcassonne, it was a strategic prize. Not taking any chances, they evicted the residents, whom they allowed to settle in the lower town (Ville Basse)—as long as they stayed across the river. (Though it’s called “new,” this lower town actually dates from the 13th century.) La Cité remained a French military garrison until the 18th century.

This drawbridge was made crooked to slow attackers’ rush to the main gate and has a similar effect on tourists today.

This is La Cité’s biggest gate and worth a closer look. High above, between the two big turrets, a statue of Mary blesses all who enter. She may be blessing you, but not if you’re an enemy: The drawbridge is outfitted with “murder holes” to attack people from above, a heavy portcullis (a big iron grate) that dropped down, and huge doors bolstered by beefy sliding beams. Notice the arrow slits. (In fact, you’re already dead.) Behind you is a barbican, an extra defensive tower.

• Don’t enter the city yet. After crossing the drawbridge, lose the crowds and walk left between the walls. At the first short set of stairs, climb to the outer-wall walkway and linger while facing the inner walls.

Wall Walk: The Romans built Carcassonne’s first wall, upon which the bigger medieval wall was constructed. Identify the ancient Roman bits by looking about one-third of the way up and finding the smaller rocks mixed with narrow stripes of red bricks (and no arrow slits). The outer wall that you’re on was not built until the 13th century (after the French defeated the city), more than a thousand years after the Roman walls went up. The massive walls you see today, with 52 towers, defended an important site near the intersection of north-south and east-west trade routes.

Look over the wall and down at the moat below (now mostly used for parking). Like most medieval moats, it was never filled with water (or even alligators). A ditch like this—which was originally even deeper—effectively stopped attacking forces from rolling up against the wall in their mobile towers and spilling into the city. Another enemy tactic was to “undermine” (tunnel underneath) the wall, causing a section to cave in. Notice the small, square holes at foot level along the ramparts. Wooden extensions of the rampart walkways outside the walls (which we’ll see later, at the castle) once plugged into these holes so that townsfolk could drop nasty, sticky things on anyone trying to tunnel underneath. When you see a new section of a wall like this, it’s often an indication that the spot was once successfully undermined.

In peacetime the area between the two walls (les lices) was used for medieval tournaments, jousting practice, and markets. But during times of war, it was always kept clear so defenders could see and target anyone approaching.

During La Cité’s Golden Age, the 1100s, independent rulers with open minds allowed Jews and Cathars to live and prosper within the walls, while troubadours wrote poems of ideal love. This liberal attitude made for a rich intellectual life but also led to La Cité’s downfall. The Crusades aimed to rid France of the dangerous Cathar movement (and their liberal sympathizers), which led to Carcassonne’s defeat and eventual incorporation into the kingdom of France.

The walls of this majestic fortress were partially reconstructed in 1855 as part of a program to restore France’s important monuments (led by the Neo-Gothic architect Eugène Viollet-le-Duc). The tidy crenellations and the pointy tower roofs are generally from the 19th century.

As you continue your wall walk to higher points, the lack of guardrails is striking. This would never fly in the US, but in France, if you fall, it’s your own fault (so be careful). Note the lights embedded in the outer walls. This fortress, like most important French monuments, is beautifully illuminated every night (for directions to a good nighttime view, see “Night Wall Walk” under “Sights in Carcassonne,” later).

• You could keep working your way around the walls (though you may be detoured inside for a stretch if special events block your path). If you do the entire wall walk, you’ll see five authentic Roman towers just before returning to the Narbonne Gate. Walking the entire circle between the inner and outer gate is a terrific 30-minute stroll (and fantastic after dark).

But for this tour, we’ll stop at the first possible entrance into La Cité, the...

Inner Wall Tower (St. Nazaire Tower): The tower has the same four gates it had in Roman times. Before entering, notice the squat tower on the outer wall—this was another barbican (placed opposite each inner gate for extra protection). Barbicans were generally semicircular—open on the inside to expose anyone who breached the outer defenses. Notice the holes in the barbican for supporting a wooden catwalk.

While breaching the wall, study the ornate defenses. Look to the right. Damn. More arrow slits—you’re dead again. Look up to see a slot for the portcullis and the frame for a heavy wooden door. Imagine the heavy beams that would have bolstered the door against battering rams. The beam hole on the left goes back eight feet so the beam could slide. The entry is at an angle (to provide better cover). At the inner set of doors, you can see centuries-old, rusty parts of the hinge.

Once safely inside the wall, pretend you’re a defender. Hook right and station yourself in the first arrow slit, where the design gives you both range and protection. Notice how, from here, you can guard the entrance through the outer wall (immediately opposite).

• Opposite the tower stands the...

St. Nazaire Church (Basilique St. Nazaire): This was a cathedral until the 18th century, when the bishop moved to the lower town. Today, due to the depopulation of the basically dead-except-for-tourism Cité, it’s not even a functioning parish church. Step inside. Notice the Romanesque arches of the nave and the delicately vaulted Gothic arches over the altar and transepts. After its successful conquest of this region in the 13th-century Albigensian Crusades, France set out to destroy all the Romanesque churches and replace them with Gothic ones—symbolically asserting its northern rule with this more northern architectural style. With the start of the costly Hundred Years’ War in 1337, the expensive demolition was abandoned. Today, the Romanesque remainder survives, and the destroyed section has been rebuilt Gothic, leaving us with one of the best examples of Gothic architecture in southern France. When the lights are off, the interior—lit only by candles and 14th-century stained glass (some of finest in southern France)—is evocatively medieval. A plaque near the door says that St. Dominique (founder of the Dominican order) preached at this church in 1213.

• The ivy-covered luxury hotel in front of the church entrance is...

Hôtel de la Cité: This hotel sits where the bishop’s palace did 700 years ago. Today, it’s a worthwhile detour to see how the privileged few travel. You’re welcome to wander in. Find the cozy bar/library (consider returning for a pre- or post-dinner drink). Stepping into the rear garden, turn right for super wall views.

While little of historic interest survives in La Cité, along with this bishop’s palace, it was once filled with abbeys, monasteries, the headquarters of the local Inquisition, fortified noble mansions, and one huge castle within this castle—our next stop.

• Leaving the hotel, turn left and take the right fork at the medieval flatiron building. Notice the surviving timbers and medieval wattle-and-daub construction (spaces between the oak posts were filled in with twigs and sticks, then finished with a layer of clay, mud, or dung). You can see the beams were roughed up so the daub finish would attach more firmly.

Follow Rue St. Louis for several blocks. Merge right onto Rue de la Porte d’Aude, then look for a small view terrace on your left, a block up.

Château Comtal: Originally built in 1125, Carcassonne’s third layer of defense was enlarged in later reconstructions. From this impressive viewpoint you can see the wooden rampart extensions (rebuilt in modern times) that once circled the entire city wall. (Notice the empty peg holes to the left of the bridge.) During sieges, these would be covered with wet animal skins as a fire retardant. Château Comtal is a worthwhile visit for those with time and interest (see “Sights in Carcassonne,” later).

• Fifty yards away, opposite the entrance to the castle, is...

Place du Château: This busy little square sports a modest statue honoring the man who saved the city from deterioration and neglect in the 19th century—Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, who also restored Paris’ Notre-Dame Cathedral. The bronze model (considered fairly accurate) circling the base of the statue shows Carcassonne’s walls as they looked before their fanciful 1855 Neo-Gothic reconstruction.

• It’s downhill from here to the Narbonne Gate (where this walk started). But first, one last stop. Backtrack a few steps to face the château entry, then turn right and walk one block to...

Place du Grand Puits: This huge well is the oldest of Carcassonne’s 22 wells. In an age of starve-’em-out sieges, it took more than stout walls to keep a town safe—you also needed a steady supply of water and food.

• Our walk is finished. You can return to the Château Comtal entrance gate to tour the castle. Or, if you turn left at the fountain, you’ll pop out in the charming, restaurant-lined Place St-Jean; a hard left here takes you down into the château’s moat garden (free to roam) and a small gate (on the right side of the castle), which leads to the most impressive part of the city wall (around the Porte d’Aude).

Save some post-dinner energy for a don’t-miss walk around the same walls you visited today (great dinner picnic sites as well). The effect at night is mesmerizing: The embedded lights become torches and unfamiliar voices become the enemy. You can enter and exit the old city from two locations: Porte d’Aude, on the west side, or from the main Narbonne Gate, on the east side. From either point you can walk 15 minutes down to the Pont Vieux (old bridge) and find an unforgettable view of the floodlit walled town. Ideally, take one route down and the other back up (see the “La Cité” map).

Your best look at Carcassonne’s medieval architecture is a walk through this castle-within-the-castle, followed by a walk atop the city ramparts (possible only with a castle ticket). Grab the basic flier in English (and rent the audioguide for the full story—as narrated by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, the man who restored the old city in the 19th century), cross the drawbridge over the garden moat, and once inside the courtyard, enter the château on your left and climb to the top of the stairs.

Start your visit in a small theater, where a short video sets the stage. Next is a big model of La Cité (made in 1910 to show the city as it looked in 1300). Enjoy the black-and-white images of old Carcassonne on the walkway above. From here, a self-guided tour with posted English explanations (and your audioguide) leads you around the inner ramparts of Carcassonne’s castle. You’ll see the underpinnings of the towers and of the catwalks that hung from the walls, and learn all about medieval defense systems. The views are terrific. Your visit ends with a museum showing fragments from St. Nazaire Church and important homes.

From the castle you can climb out onto the highest city ramparts and circle about two-thirds of the old town. The north rampart is open all the way to the main Narbonne Gate, but there’s no exit and you’ll need to backtrack. The west rampart lets you circle all the way to the St. Nazaire Tower, from where you can exit (drop off your audioguide before entering the west rampart). I’d explore both sections.

Cost and Hours: €9.50, daily 10:00-18:30, Oct-March 9:30-17:00, last entry 45 minutes before closing, audioguide-€3, +33 4 68 11 70 70, www.remparts-carcassonne.fr.

A magnificent stretch of fortifications extends behind Château Comtal. The impressive gate called Porte d’Aude is central to this section and allows access from the walls down a path to Pont Vieux, a 14th-century bridge that spans the Aude River with 12 massive arches. It was built to connect La Cité with the Ville Basse, which was first populated with outcasts from La Cité. Agreements and treaties between the two towns (which did not always get along) were signed here. Today the pedestrian-only bridge provides stirring views day or night and access to walking paths along the river. Those paths run along both banks of the river, offering occasional views to the fortress and a verdant escape for runners and walkers.

Completed in 1681, this sleepy 155-mile canal connects France’s Mediterranean and Atlantic coasts and, at about its midpoint, runs directly in front of the train station in Carcassonne. Before railways, Canal du Midi was clogged with commercial traffic; today, it floats only pleasure craft. Carcassonne Navigation runs 1.5-2.5-hour canal trips from in front of the station (about €9-11, April-Oct 2-4/day, longer cruises with meals also possible, www.carcassonne-navigationcroisiere.com).

Travelers with limited time are best off biking along the canal: The path is level, pedaling is a breeze, and you can cover far more territory than by boat—for bike rental locations, ask at the TI.

Duck into this impressive photo gallery in the old town before selecting which Cathar castles you want to visit (brilliant shots of many monuments in Languedoc-Roussillon, generally daily 10:00-12:30 & 14:00-19:00, just up from Place Marcou at 27 Rue du Plô).

There are several low-key ways to enjoy La Cité after dark. For relief from all the medieval kitsch, savor a pricey drink in four-star, library-meets-bar ambience at the Hôtel de la Cité bar. To taste the liveliest square, with loads of tourists and strolling musicians, sip a drink or nibble a dessert on Place Marcou. Near the château, the recommended L’Escargot morphs into a convivial bar after dinner is finished.

For a peaceful drink and floodlit views from outside the wall, pause at the recommended Hôtel du Château’s broad terrace, below the Narbonne Gate (2 Rue Camille Saint-Saëns). To be a medieval poet, share a bottle of wine in your own private niche somewhere remote on the ramparts.

Le Bar à Vins is the only real nightclub in the old town. It’s a down and dirty bar with a huge open-air terrace offering lively music, plenty of drinks, and a fun garden scene in the moonshadow of the wall...without any tourists (daily 12:00 until late in high season, 6 Rue du Plô, +33 4 68 47 38 38). They serve gut-bomb bar food without a full-service kitchen.

Sleep within or near the old walls, in La Cité. I’ve also listed a hotel near the train station. In the summer, when La Cité is jammed with tourists, consider sleeping in quieter Caunes-Minervois. July and August are most expensive, when the town is packed. At other times of the year, prices drop and there are generally plenty of rooms. Hotels have air-conditioning and elevators, unless noted.

Pricey hotels, good B&Bs, and an excellent youth hostel offer a full range of rooms inside the walls. The first three places are run by the same outfit. The Hôtel de la Cité and Best Western Hôtel le Donjon offer private pay parking near the castle moat (pass the small cemetery, heading slightly uphill, and find the attendant; includes bag transfers); they also validate parking in the main lot below the Narbonne Gate (no bag transfers; you must show your reservation or have the attendant call your hotel).

$$$$ Hôtel de la Cité***** offers 59 rooms with deluxe everything in a beautiful building next to St. Nazaire Church. Peaceful gardens, a swimming pool and spa, royal public spaces, the elegant Barbacane restaurant, and reliable luxury are yours—for a price (family rooms, pay parking, Place Auguste-Pierre Pont, +33 4 68 71 98 71, www.hoteldelacite.com, h8613@accor.com).

$$$ Best Western Hôtel le Donjon**** has 61 well-appointed rooms, a lobby with wads of character, and a great location inside the walls. Rooms are split between three buildings in La Cité (the main building, a lookalike annex across the street, and the cheaper Maison des Remparts a few blocks away). The main building is most appealing, and the rooms with terraces on the garden are delightful (free and secure pay parking, 2 Rue Comte Roger, +33 4 68 11 23 00, www.hotel-donjon.fr, info@bestwestern-donjon.com).

$ Chambres le Grand Puits, across from Maison des Remparts, is a splendid value. It has one cute double room and two cavernous apartment-like rooms that could sleep five, with kitchenette, private terrace, and sweet personal touches. Inquire in the small boutique, and say bonjour to happy-go-lucky Nicole (includes self-serve breakfast, cash only, no elevator, no air-con, 8 Place du Grand Puits, +33 4 68 25 16 67, http://legrandpuits.free.fr, legrandpuits@free.fr).

¢ Hostel Carcassonne is big, clean, and well-run, with an outdoor garden courtyard, self-service kitchen, TV room, bar, washer/dryer, and a welcoming ambience. If you ever wanted to bunk down in a hostel, consider doing it here—all ages are welcome. Reserve ahead for summer (€11/person membership, includes breakfast, rental towels, Rue du Vicomte Trencavel, +33 4 68 25 23 16, www.hifrance.org or www.hihostels.com, carcassonne@hifrance.org).

Sleeping just outside La Cité offers the best of both worlds: quick access to the ramparts, less claustrophobic surroundings, and easy parking.

$$$ Hôtel du Château**** and $$ Hôtel le Montmorency*** are adjacent hotels that lie barely below La Cité’s main gate and are run by the same family. Check-in, parking, and breakfast for both hotels are at Hôtel du Château. Guests enjoy an easy walk to La Cité, a snazzy pool, hot tub, view terraces to the walls of Carcassonne, a lazy hound, and a sweet cat. Hôtel du Château gives four-star comfort with 17 sumptuous rooms (RS%—use code “RICKSTEVES,” pay parking, 2 Rue Camille Saint-Saëns, +33 4 68 11 38 38, www.hotelduchateau.net, contact@hotelduchateau.net). Hôtel Montmorency, a short walk behind Hôtel du Château, offers très mod rooms, some with views to the ramparts. Many come with private decks or terraces (RS%—use code “RICKSTEVES,” no elevator but only one floor up, pay parking, 2 Rue Camille Saint-Saëns, +33 4 68 11 96 70, www.hotelmontmorency.com, contact@hotelmontmorency.com).

$$ Hôtel Mercure**** hides a block behind the Hôtel le Montmorency, a five-minute walk to La Cité. It rents 80 snug but comfy air-conditioned rooms and has a refreshing garden, good-sized pool, big elevators, a restaurant, and a warm bar-lounge. A few rooms have views of La Cité (many family rooms, free parking, 18 Rue Camille Saint-Saëns, +33 4 68 11 92 82, www.mercure.com, h1622@accor.com).

These places are on either side of the Pont Vieux, about 15 minutes below La Cité and 15 to 20 minutes from the train station on foot.

$$ Hôtel les Trois Couronnes,**** a modern hotel in a concrete shell just across Pont Vieux, offers 44 rooms with terrific views up to La Cité—and 26 nonview rooms that you don’t want (indoor pool with views, pay parking garage, 2 Rue des Trois Couronnes, +33 4 68 25 36 10, www.hotel-destroiscouronnes.com, contact@hotel-destroiscouronnes.com). Their reasonably priced restaurant also has a good view.

$$ Hôtel de l’Octroi*** delivers colorful, contemporary comfort, efficient service, and a young vibe from its full-service bar to its small, stylish pool and 21 rooms (RS%—use code “RICKSTEVES,” family rooms, no elevator, pay parking, 143 Rue Trivalle, +33 4 68 25 29 08, www.hoteloctroi.com).

$ Hôtel Espace Cité,** three blocks downhill from the main gate to La Cité, is a fair value, with 48 small-but-clean, cookie-cutter rooms (no elevator, limited free parking—otherwise pay parking in garage, 132 Rue Trivalle, +33 4 68 25 24 24, www.hotelespacecite.fr, espace-cite@hotel-espace-cite.fr).

$ Carcassonne Bed and Breakfast is a meticulously maintained, five-room chambres d’hôte that sits a 15-minute walk below La Cité and 20 minutes from the train station. Rooms are gorgeously furnished with antiques, some have views of Carcassonne, and there’s a cool courtyard to relax in (12 Rue Fernand Merlane, +33 4 68 25 80 34, www.carcassonnebandb.com, info@carcassonnebandb.com).

$ Chambres les Florentines is a good-value B&B run by charming Madame Mistler. The five rooms are spacious, traditional, and homey; one room has a big deck and grand views of La Cité (cash only, family rooms, includes breakfast, no air-con, no elevator, pay parking, 71 Rue Trivalle, +33 4 68 71 51 07, www.lesflorentines.net, lesflorentines11@gmail.com).

$ Hôtel du Pont Vieux,** with welcoming Catherine and Jean-Michel, offers 19 sharp rooms, a peaceful garden, and a small rooftop terrace with million-dollar views. Four rooms come with views to La Cité; others look over the garden (secure parking garage—reserve ahead, no elevator, 32 Rue Trivalle, +33 4 68 25 24 99, www.hotelpontvieux.com, info@hoteldupontvieux.com).

$ Hôtel Astoria** has some of the cheapest hotel beds that I list in town, divided between a main hotel and an annex across the street. Book ahead—it’s popular. The updated annex rooms have air-conditioning; rooms in the main building are simple—the cheapest have a shared bath (no elevator, pay parking—reserve ahead, bike rentals, baggage storage for small fee; from the train station, walk across the canal, turn left, and go two blocks to 18 Rue Tourtel; +33 4 68 25 31 38, www.astoriacarcassonne.com, info@astoriacarcassonne.com).

To experience unspoiled, tranquil Languedoc-Roussillon, sleep surrounded by vineyards in the characteristic village of Caunes-Minervois. Comfortably nestled in the foothills of the Montagne Noire, Caunes-Minervois is a 25-minute drive from Carcassonne. Take route D-118 or follow signs toward Mazamet to a big roundabout and find D-620. The town houses an eighth-century abbey, two cafés, several restaurants, a pizzeria, a handful of wineries, and only a trickle of tourists. The friendly staff at the town’s TI (in the abbey) is eager to help you explore the region. Caunes-Minervois makes an ideal base for exploring the area’s wine roads. For even more remote accommodations, see my recommendations in Couiza and Cucugnan, under “South of Carcassonne,” later.

$ Hôtel d’Alibert, in a 15th-century home with character, sits in the heart of the village. It has a mix of nicely renovated and Old World traditional rooms. It’s managed with a relaxed je ne sais quoi by Frédéric “call me Fredo” Dalibert and his son, who can help plan your wine-tasting excursion (includes breakfast, Place de la Mairie, +33 4 68 78 00 54, www.hotel-dalibert.com, frederic.guiraud.dalibert@gmail.com). Tasty meals are offered most days in his cozy restaurant with great courtyard tables.

For a social outing in La Cité, take your pick from a food circus of basic eateries on a leafy courtyard—often with strolling musicians in the summer—on lively Place Marcou. If rubbing elbows with too many tourists gives you hives, go local and dine below in Ville Basse (the new city). Cassoulet (described on here) is the traditional must. It’s a rustic peasant’s dish—beloved for sure, but locals will remind you “there’s no gourmet cassoulet” (tip: a dash of vinegar helps the digestion); big salads provide a lighter alternative. For a local before-dinner drink, try a glass of Muscat de Saint-Jean-de-Minervois.

$$$ Comte Roger has a quiet elegance that seems out of place in this touristy town. If you want one fine meal in the old town, book a table here to enjoy Chef Pierre’s fresh Mediterranean cuisine. Ask for a table on the vine-covered patio or eat in their stylish dining room. Their €50 menu is the best gourmet value in town. Pierre’s cassoulet comes closer than anyone to breaking the “no gourmet cassoulet” rule (closed Sun-Mon, 14 Rue St. Louis, +33 4 68 11 93 40, www.comteroger.com).

$$ Auberge des Lices, serving traditional plates with a rustic-plush ambience, is hidden down a quiet lane and has a courtyard with cathedral views (daily July-Aug, closed Tue-Wed Sept-June, vegetarian options, 3 Rue Raymond Roger Trencavel, +33 4 68 72 34 07).

$$ Le Jardin de la Tour, run with panache by Elodie for many years, offers good cassoulet, duck, seafood, and a list of first-course plates designed for sharing family-style. Inside you’ll feel like you’re dining in an antique shop; outside, enjoy the peaceful atmosphere in the parklike garden (closed Sun-Mon, lunch served July-Aug only, 11 Rue de la Porte d’Aude, +33 4 68 25 71 24).

$ L’Escargot, casual and welcoming, feels like a wine bar with tapas. The tight seating, sizzle of an open kitchen, minimal tables, wine-bottle walls, and popular following combine to create a convivial bustle. Thomas and his black-shirted staff serve several gourmet salads and give their Spanish and French plates an extra twist: anise in the escargot, apple in the foie gras...and definitely no cassoulet. Reserve ahead during busy times (lunch from 12:15 and two dinner seatings: 19:00 and 21:00, three seating zones: peaceful streetside, quiet basement, busy ground-floor kitchen area, closed Wed and in winter, 7 Rue Viollet-Le-Duc, +33 4 68 47 12 55, https://restaurant-lescargot.com).

When L’Escargot is full, they send people two blocks away to their branch Le Jardin de L’Escargot, with the same formula (decor, menu, and prices) at 4 Rue St. Jean.

$$ Le Chaudron takes its cassoulet seriously. It’s carefully traditional, served with a salad, and may be the best in town. You’ll dine in a peaceful outdoor setting under the shade of trees, in the simple interior room, or the more refined and spacious upstairs space (daily July-Aug, closed Mon-Tue off-season, 6 Rue St Jean, +33 4 68 71 09 08).

Castle Views On Place St. Jean: On this great little square in La Cité, several eateries compete for your business. All have outside terrace tables with views to the floodlit Château Comtal. $ Restaurant Adélaïde is a lively bistro with good prices; they serve a three-course menu with cassoulet as well as big salads (daily except closed Mon Sept-May, +33 4 68 47 66 61). Kid-friendly $ Le Créneau, with more commotion and energy, serves creative tapas, pizzas, and Spanish plates. They have a cafeteria vibe inside and a sunny, castle-view roof terrace. Owner-chef Paul is enthusiastic about his oysters and escargot (daily, +33 4 68 71 81 53).

Picnics: Basic supplies can be gathered at shops along the main drag (generally open until at least 19:30, better to buy outside La Cité). For your beggar’s banquet, picnic on the city walls or in the little park above Place Marcou.

$$ Restaurant les Trois Couronnes, just across the Pont Vieux in the recommended Hôtel les Trois Couronnes, gives you a panorama of Carcassonne from the top floor of a concrete hotel (open daily for dinner only, closed Jan, call ahead, 2 Rue des Trois Couronnes, +33 4 68 25 36 10).

From Carcassonne by Train to: Albi (10/day, 3 hours, change in Toulouse), Collioure (8/day, 2-3 hours, most require change in Perpigan), Sarlat-la-Canéda (5/day, 7 hours, 1-2 changes usually in Bordeaux and/or Toulouse), Arles (2/day direct, 2.5 hours, more with transfer in Narbonne or Nîmes), Nice (3/day, 7 hours with change in Marseille), Paris (Gare de Lyon: 8/day, 6 hours, 1 change), Toulouse (nearly hourly, 1 hour), Barcelona (1/day direct, 2.5 hours, 5/day with change in Narbonne, 3 hours).

The land around Carcassonne is carpeted with vineyards and littered with romantically ruined castles, ancient abbeys, and photogenic villages. To the south, the castle remains of Peyrepertuse and Quéribus make terrific stops between Carcassonne and Collioure (allow 2 hours from Carcassonne on narrow, winding roads; from the castles it’s another 1.5 hours to Collioure). You can also link them on a fine loop trip from Carcassonne.

Northeast of Carcassonne, two Cathar sights and the gorge-sculpted village of Minerve (45 minutes from Carcassonne), work well for Provence-bound travelers or as a day trip from Carcassonne.

Getting There: Public transportation is hopeless; taxis for up to six people cost about €330 for a daylong excursion (taxi +33 4 68 71 50 50). See here for excursion bus and minivan tours to these places.

About two hours south of Carcassonne, in the scenic foothills of the Pyrenees, lies a series of surreal, mountain-capping castle ruins. Like a Maginot Line of the 13th century, these cloud-piercing castles were strategically located between France and the Spanish kingdom of Roussillon. As you can see by flipping through the picture books in Carcassonne’s tourist shops, these crumbled ruins are an impressive contrast to the restored walls of La Cité. You’ll want a hat (there’s no shade) and sturdy walking shoes—prepare for a vigorous climb.

Getting There: Connect two of these castles (but visit just one) along this incredibly scenic, 2.5-hour drive. You can either make a loop from Carcassonne or continue on to the seaside village of Collioure.

From Carcassonne drive to Limoux, then Couiza. At Couiza follow little D-14 to Bugarach (passing through Languedoc’s only spa town, Rennes-le-Château). Near Bugarach, views open to rocky ridgelines hovering above dense forests. You’ll soon see signs leading the way to Peyrepertuse. At Cubières, canyon lovers can detour to the Gorges de Galamus, driving partway into the teeth of white-rock slabs that seem to squeeze closer the farther in you go (those looping back to Carcassonne can do the whole canyon on their way back). Peyrepertuse is a short hop from Cubières; you’ll pass snack stands and view cafés on the twisty drive up. After visiting this Cathar castle, your next destination—Quéribus—is a well-signed, 15-minute drive away.

From Quéribus it’s a 1.5-hour drive to Collioure (follow signs in direction: Maury, then direction: Perpignan). If returning to Carcassonne, follow signs for Maury, then St-Paul-de-Fenouillet, then drive through the Gorges de Galamus and track D-14 to Bugarach, Couiza, Limoux, and Carcassonne.

Sleeping Along This Route: If sleeping in a 16th-century fortified castle stirs your soul, head for the peaceful village of Couiza and the $$ Château des Ducs de Joyeuse,*** where you’ll sleep like a duke at commoner prices. The sturdy castle has been renovated into a fine hotel with a pool, a pétanque field, tennis courts, and a central courtyard smothered with ambience. Enjoy a meal at its reasonably-priced $$ restaurant (Allée Georges Roux, Couiza, +33 4 68 74 23 50, www.chateau-des-ducs.com, reception@chateau-des-ducs.com).

To really get away (and I mean really), sleep in the little village of Cucugnan, located between Peyrepertuse and Quéribus. $ L’Ecurie de Cucugnan is a friendly bed-and-breakfast with five comfortable rooms at great rates, a view pool, and a shady garden. Joël, winemaker and owner, doesn’t speak English, but his wife—a teacher—does (includes breakfast, full house rental available, 18 Rue Achille Mir, +33 4 68 33 37 42, www.cucugnan.fr, ecurie.cucugnan@orange.fr).

$$ Ferrairolles Eco Guesthouse, about 16 miles from the castle ruins, is an elegant four-room guesthouse run by dynamic Dutchwoman Rolinka Bloeming (who doubles as a Rick Steves’ Europe tour guide). Located on the scenic route from Carcassonne to Collioure in remote Villeneuve-les-Corbières, it’s 30 minutes from the Mediterranean and surrounded by Cathar castles, canyons, hiking trails, and vineyards (includes breakfast, nice pool, ask about vegetarian dinners with wine, mobile +33 6 47 53 16 34, www.rolinkablooming.com, ecoguesthouseferrairolles@gmail.com).

The most spectacular Cathar castle is Peyrepertuse (pay-ruh-pehr-tews), where the ruins rise from a splinter of cliff: Try to spot it on your drive up from the village. From the parking lot, you’ll first hike downhill, curling around the back of the rock wall, then hike steeply up 15 minutes through a scrubby forest to the fortress. The views are sensational in all directions (including to Quéribus, sticking up from an adjacent ridge). But what’s most amazing is that they could build this place at all. This was a lookout in the Middle Ages, staffed with 25 very lonely men. Today, it’s a scamperer’s paradise with weed-infested structures in varying states of ruin. Let your imagination soar, but watch your step as you try to reconstruct this eagle’s nest—the footing is tricky. Don’t miss the St. Louis stairway to the upper castle ruins—another stiff, 10-minute climb straight up.

Cost and Hours: €7, daily 9:00-19:00, July-Aug until 20:00, shorter hours off-season and closed Jan, theatrical audioguide-€4 for two (narrated from the perspective of a French captain posted here), free handout gives plenty of background, +33 4 30 37 00 77, www.chateau-peyrepertuse.com).

While Peyrepertuse rides along a high ridge, this bulky castle caps a mountaintop and delivers more amazing views (find the snow-covered peaks of the Pyrenees). It owns a similar history to Peyrepertuse but has an easier (but still uphill) footpath to access the site and gentler climbing within the ruins. It’s famous as the last Cathar castle to fall, and was abandoned after 1659, when the border between France and Spain was moved farther south into the high Pyrenees.

Cost and Hours: €7.50, daily 9:30-19:00—July-Aug until 20:00, Oct-April 10:00-17:00 or 18:00), theatrical audioguide-€4 for two, good handout, +33 4 68 45 03 69, www.cucugnan.fr.

The next two Cathar sights provide an easy excursion north from Carcassonne, offering a taste of this area’s appealing countryside. They tie in well with a visit to the village of Caunes-Minervois (where I recommend sleeping—see here).

Ten scenic miles north of Carcassonne, four ruined castles cap a rugged hilltop and give visitors a handy (if less dramatic) look at the region’s Cathar castles. These castles, which once surrounded a fortified village, date from the 11th century. The village welcomed Cathars (becoming a bishop’s seat at one point) but paid dearly for this tolerance with destruction by French troops in 1227. But three of the four castles still have their towers intact.