Colmar • Route du Vin • Strasbourg

Towns and Sights Along the Route du Vin

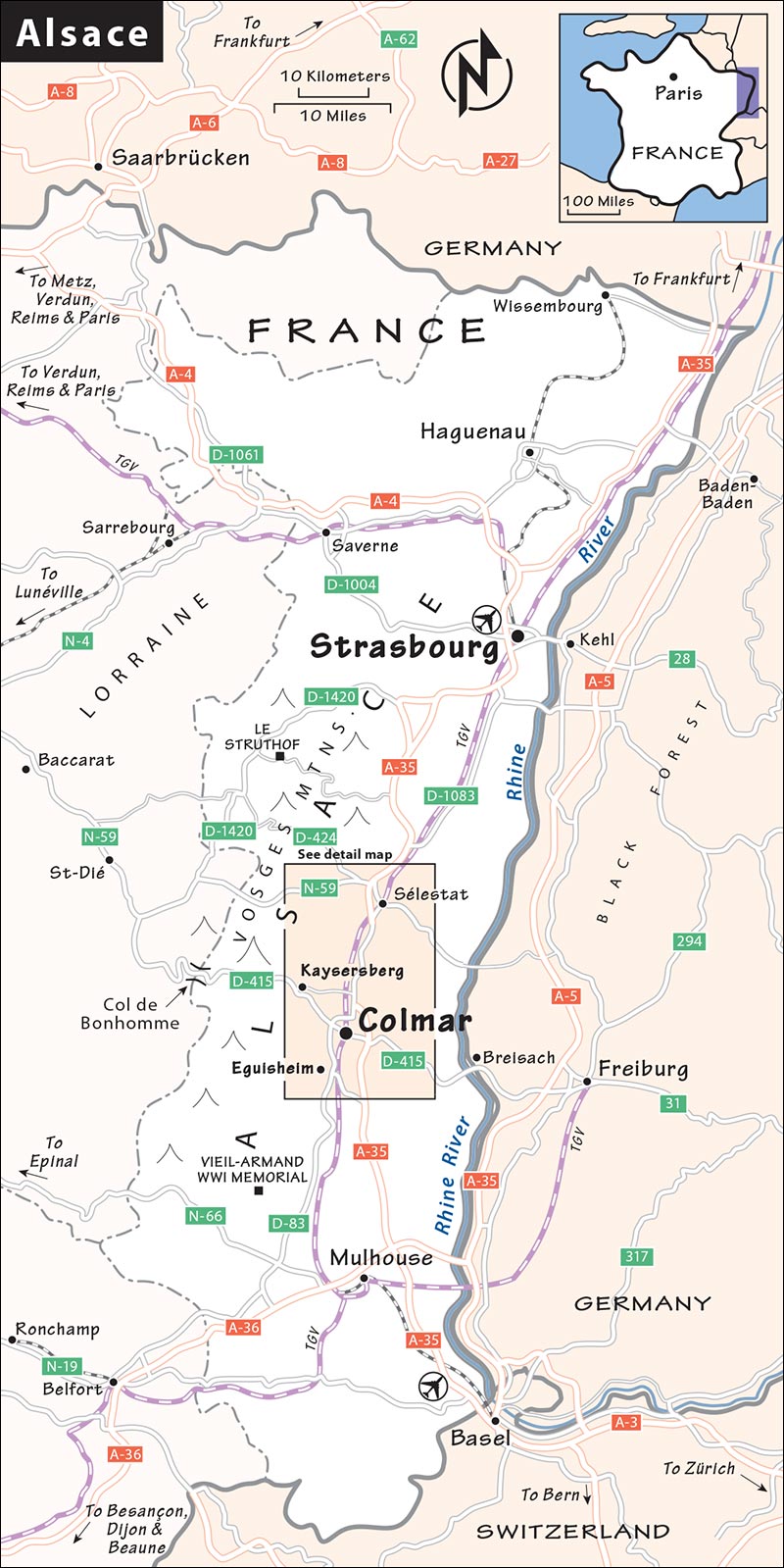

The province of Alsace stands like a flower-child referee between Germany and France. Bounded by the Rhine River on the east and the Vosges Mountains on the west, this is a green region of Hansel-and-Gretel villages, ambitious vineyards, and vibrant cities. Food and wine are the primary industry, topic of conversation, and perfect excuse for countless festivals.

Alsace has changed hands between Germany and France several times because of its location, natural wealth, naked vulnerability—and the fact that Germany considered the mountains the natural border, while the French saw the Rhine as the dividing line.

On a grander scale, Alsace is Europe’s cultural divide, with Germanic nations to the north and Romantic ones to the south. The region is a fault line marking the place where cultural tectonic plates collide—it’s no wonder the region has been scarred by a history of war.

Through the Middle Ages, Alsace was part of the Holy Roman Empire when German culture and language ruled. After the devastation of the Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648), Alsace started to become integrated into France—revolutionaries took full control in 1792. But in 1871, after France’s defeat in the Franco-Prussian War, Alsace “returned” to Germany. Almost five decades later, Germany lost World War I—and Alsace “returned” to France. Except for a miserable stint as part of the Nazi realm from 1940 to 1945, Alsace has been French ever since.

Having been a political pawn for 1,000 years, Alsace has a hybrid culture: Natives who curse do so bilingually, and the local cuisine features sauerkraut with fine wine sauces. In recent years, Alsace and its sister German region just across the border have been growing farther apart linguistically—but closer commercially. People routinely cross the border to shop and work. And, while Alsace’s Germanic-based dialect is fading, schools on the German side are encouraged to teach French as the second language and vice versa. Street names are commonly shown in both French and Alsatian.

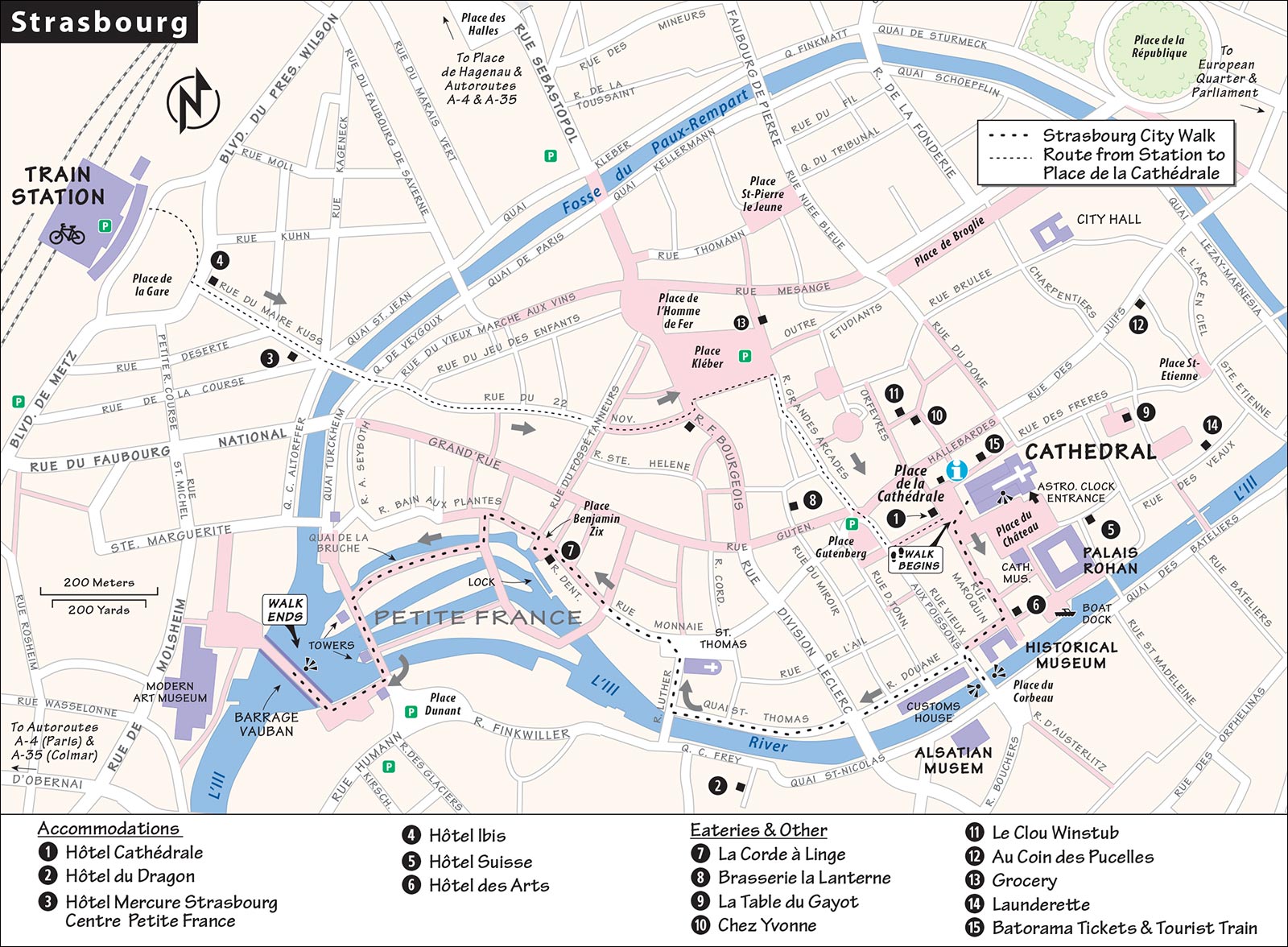

Of the 1.8 million people living in Alsace, about 275,000 live in Strasbourg (its biggest city) and 70,000 live in Colmar. Colmar is one of Europe’s most enchanting cities—with a small-town warmth and world-class art. Strasbourg is a big-city version of Colmar, worth a stop for its venerable cathedral and to feel its high-powered and trendy bustle. The small villages that dot the wine road between them are like petite Colmars and provide a delightful and charming escape from the two cities.

The ideal plan: Make Colmar your home base and spend two or three days in the region. I’d spend a day each in Colmar, the villages of the Route du Vin, and Strasbourg. If you have a car and sleep better in small towns, think about basing yourself in Eguisheim. Urban Strasbourg, with its soaring cathedral and vigorous center, is a headache for drivers but a quick 30-minute train ride from Colmar—do it by train as a day trip from Colmar or as a stopover on your way in or out of the region. If you have only one day, get an early start for a morning along the Route du Vin, when it’s quieter, and enjoy an afternoon and evening in Colmar.

The somber WWI battlefields of Verdun and the bubbly vigor of Reims in northern France (see next chapter) are closer to Paris than to Alsace and follow logically if your next destination is Paris. The high-speed TGV train links Paris with Reims, Verdun, Strasbourg, Colmar, and destinations farther east, bringing the Alsace within two hours of Paris and giving train travelers easy access to Reims or Verdun en route between Paris and Alsace.

Frequent trains make the trip between Colmar and Strasbourg a snap (2/hour, 30 minutes). Distances are short and driving is easy—though a good map helps. Connecting Colmar with neighboring villages is doable via the region’s sparse bus service or on a bike if you’re in shape. Minivan excursions are handy for those without cars and depart from Colmar or Strasbourg. Taking a taxi between towns is another worthwhile option (distances are short so prices are fair). Once in the Route du Vin villages, you can hike or rent bikes to explore further.

Alsatian cuisine is a major tourist attraction in itself. You vill not escape the German influence: sausages, potatoes, onions, and sauerkraut. Look for choucroute garnie (sauerkraut and sausage), the more traditionally Alsatian Baeckeoffe (see sidebar), Rösti (an oven-baked potato-and-cheese dish), Spätzle (soft egg noodles), quenelles (dumplings made of pork, beef, or fish), fresh trout, and foie gras. For lighter fare, try the poulet au Riesling, chicken cooked slowly in Riesling wine (coq au Riesling is the same dish done with rooster). At lunch, or for a lighter dinner, try a tarte à l’oignon (like an onion quiche) or tarte flambée (like a thin-crust pizza with onion and bacon bits). If you’re picnicking, buy some stinky Munster cheese. Dessert specialties are tarte alsacienne (fruit tart) and Kugelhopf glacé (a light cake mixed with raisins, almonds, dried fruit, and cherry liqueur).

Thanks to Alsace’s Franco-Germanic culture, its wines are a kind of hybrid. The bottle shape, grapes, and much of the wine terminology are inherited from its German past, though wines made today are distinctly French in style (generally drier than their German sisters). Alsatian wines are named for their grapes—unlike in Burgundy or Provence, where wines are commonly named after villages, or in Bordeaux, where wines are often named after châteaux. White wines rule in Alsace. Sample at least a few of the four “noble grapes” of the Alsace: riesling, gewürztraminer, pinot gris, or muscat. You’ll also see a local version of Champagne, called Crémant d’Alsace, and a variety of eaux-de-vie (strong fruit-flavored brandies). For more information, see the “Wines of the Alsace” sidebar on here.

Colmar feels made for wonderstruck tourists—its essentially traffic-free city center is a fantasy of steeply pitched roofs, pastel stucco, and antique timbers housing a few heavyweight sights in a comfortable, midsize-town package. Historic beauty was usually a poor excuse for being spared the ravages of World War II, but it worked for Colmar. The American and British military were careful not to bomb the half-timbered old burghers’ houses, characteristic tiled roofs, and cobbled lanes of Alsace’s most beautiful city. The town’s distinctly French shutters combined with the ye-olde German half-timbering gives Colmar an intriguing ambience.

Today, Colmar is alive with colorful buildings, impressive art treasures, and German tourists. Antique shops welcome browsers, homeowners fuss over their geraniums, and locals seem genuinely proud of their clean and beautiful city.

There isn’t a straight street in Colmar’s historic center—count on getting lost. Thankfully, most streets are pedestrian-only, and it’s a lovely town to be lost in. Navigate by church steeples and the helpful signs that seem to pop up whenever you need them. For tourists, the town center is Place Unterlinden (a 20-minute walk from the train station), where you’ll find Colmar’s most important museum, the TI, and a big Monoprix supermarket/department store. City buses and tourist trains depart nearby.

Colmar is busiest from May through September and during its festive Christmas season (www.noel-colmar.com). Weekends draw crowds all year (book lodging well ahead). A popular music festival fills hotels the first two weeks of July (www.festival-colmar.com), and the local wine festival keeps things flowing nicely in July and August.

The efficient TI is next to the Unterlinden Museum on Rue Unterlinden (Mon-Sat 9:00-18:00, Sun 10:00-13:00, closed for lunch in winter, +33 3 89 20 68 92, www.tourisme-colmar.com). Get information about concerts and festivals in Colmar and in nearby villages, and ask about Folklore Evenings held on summer Tuesdays (described later, under “Nightlife in Colmar”). The TI has a good city map, a bike map, and a list of launderettes, but skip their Colmar City Pass. Route du Vin travelers should pick up the free map and get information on bike rental, bus schedules, and where to catch the bus to Route du Vin villages.

By Train and Bus: The old and new (TGV) parts of Colmar’s train station are connected by an underground passageway. Follow Sortie/Avenue de la République signs to exit the station. Day-trippers can check their bags at Colmar Vélodocteurs to the left as you leave the old station (see “Helpful Hints”).

The old part of the train station was built during Prussian rule using the same plans as the station in Danzig (now Gdańsk, Poland). Check out the 1991 window that shows two local maidens about to be run over by a train and rescued by an artist. Opposite, he’s shown painting their portraits.

Connecting to the Town Center: It’s a 15-minute walk: Exit straight out of the old station past Hôtel Bristol, turn left on Avenue de la République, and keep walking. Or hop any Trace bus from the station (immediately to the left at the station) and ride to the Champ de Mars stop (Place Rapp) or the Théâtre stop, next to the Unterlinden Museum (€1.40, see the “Colmar” map, later). Taxis wait curbside to the left of the exit and charge about €8 for any downtown ride.

Connecting to Route du Vin villages: Buses to the villages arrive and depart from the front of the old station and from stops closer to the city center. As you walk out of the station, bus #145 to Kaysersberg leaves from the far left, and stops for buses #106 and #109 to Riquewihr and Ribeauvillé are to the far right (see “Alsace’s Route du Vin,” later).

By Car: Follow signs for Centre-Ville, then Place Rapp or Montagne Verte (near Hôtel St. Martin), where there are huge underground parking garages (first hour free, about €23/24 hours). Hotels can also advise you—they may have private spots or get deals at pay lots. Parking is metered along streets and in most lots in the city center, but free from 19:00-9:00 and on residential streets just outside the city center (around Boulevard St-Pierre and Rue Bartholdi near the recommended Le Maréchal and Turenne hotels). The parking lot at Place Scheuer-Kestner north of the town center is €6/day and free overnight. Half the spots are free at Parking de la Vieille Ville/Parking de la Montagne Verte near Hôtel St. Martin.

When entering or leaving on the Strasbourg side of town (north), look for the big Statue of Liberty replica—designed to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the death of sculptor Frédéric-Auguste Bartholdi. At two traffic circles closer to Colmar (look for a red devil sculpture in the middle) are the imposing army barracks built by the Germans after annexing the region in 1871.

Closed Day: Colmar’s top sight, the Unterlinden Museum, is closed on Tuesday.

Market Days: Markets take place in and around the vintage market hall (marché couvert; Tue-Sat generally 8:00-18:00, Sun 10:00-14:00, no market Mon). Textiles are on sale Thursdays on Place de la Cathédrale (all day) and Saturdays on Place des Dominicains (afternoons only). A flea market happens Fridays in summer on Place des Dominicains. The Saturday morning market on Place St. Joseph is where locals go for fresh produce and cheese (over the train tracks, 15 minutes on foot from the center, no tourists).

Department/Grocery Store: The big Monoprix, with a supermarket, is across from the Unterlinden Museum (Mon-Sat 8:00-19:00, closed Sun). A small Petit Casino supermarket stands across from the recommended Hôtel St. Martin (Mon-Sat 8:30-19:00, closed Sun).

Wine Tasting in Colmar: For a fun in-town tasting experience, visit Maison Jund. Winemakers André and Myriam Jund and family own 44 acres of vineyards and grow all 7 of the Alsatian grapes. Son Sébastien hosts the tastings in excellent English. Allow one hour (€8, call for appointment, 12 Rue de l’Ange, +33 3 89 41 58 72, www.martinjund.com). They also run a recommended guesthouse (listed later, under “Sleeping in Colmar”).

Laundry: 5àsec, across the street from the Champ de Mars park, offers wash, dry, and fold service (32 Avenue de la République, Mon-Sat 8:45-19:15, closed Sun, +33 3 89 41 75 73). The TI has a list of other launderettes.

Bike Rental: Colmar Vélodocteurs rents standard and electric bikes at the train station (€150 deposit and ID required, behind bike racks on the left as you leave the old station, Mon-Sat 8:00-12:00 & 14:00-17:00, closed Sun, +33 3 89 41 37 90). Closer to the center, rent at Lulu Cycles (closed Sun, 4 Rue d’Ingersheim, +33 3 89 41 42 66, www.lulucycles.com). I prefer renting a bike along the Route du Vin in Eguisheim, Kaysersberg, or Ribeauvillé.

Taxis: The minimum Colmar fare of about €8 gets you anywhere in town. Fares to nearby villages are reasonable—it’s just €15 for a cab to Eguisheim. You can find a taxi at the train station (to your left as you walk out, past the Trace buses), call mobile +33 6 79 50 99 96, or try William (+33 3 89 23 10 33, mobile +33 6 14 47 21 80) or Michele (mobile +33 6 72 94 65 55).

Car Rental: Avis is the only rental office at the train station (+33 3 89 23 16 89). The TI has a list of other options. Warning: Some car rental offices are located well outside the city center; verify the location before booking.

Colmar offers no scheduled city walks in English, but private English-speaking guides are available through the TI if you book in advance (about €180/3 hours, +33 3 89 20 68 95, guide@tourisme-colmar.com). Muriel Brun works independently and is a fine teacher of all things Alsatian (+33 3 89 79 70 92, muriel.h.brun@calixo.net). Stéphan Reitter is another good choice (+33 3 89 29 00 24, mobile +33 6 18 16 22 72, st.reitter@laposte.net).

Colmar has two competing choo-choo trains (green and white) that jostle along the cobbles of the old part of town offering visitors a relaxing, barely narrated half-hour tour under a glass roof (€7, departures daily 9:00-18:30). Both trains leave across from the Unterlinden Museum, follow similar routes, and offer kid discounts.

In the summer, horse-drawn carriages are also an option.

Little flat-bottomed boats glide silently on a straight stretch of the city’s canal, making a simple 30-minute lap back and forth with little or no narration (€7, departures every 10 minutes, daily 10:00-12:00 & 13:30-18:30). With eight others, you’ll pack onto the boat, gliding peacefully—powered by a silent electric motor—through a lush garden world under willows. While the route is kind of pathetic, the tranquility is enjoyable. Try to sit in front for an unobstructed view. Boats depart from Petite Venise (those leaving from the bridge at St. Pierre offer a better tour, +33 3 89 41 01 94).

9 Maison Pfister (Pfister House)

10 Meter Man

15 Maison des Têtes (“House of Heads”)

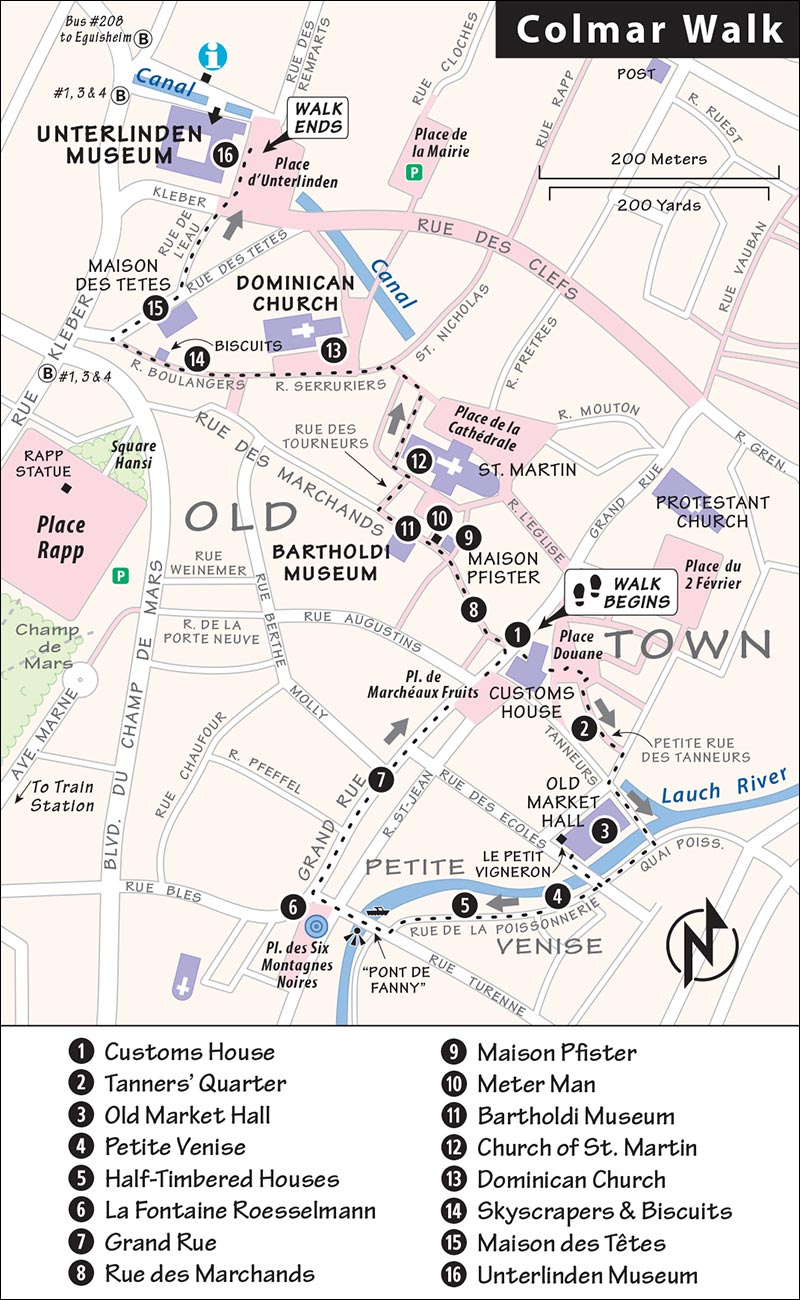

This self-guided walk—good by day, romantic by night—is a handy way to link the city’s three worthwhile sights (Little Venice, the Unterlinden Museum, and the Dominican Church). Supplement my commentary by reading the sidewalk information plaques that describe points of interest along the way. Allow an hour for this walk at a leisurely pace (longer if you enter sights). Colmar is particularly pretty after dark on Fridays and Saturdays and during festivals, when the lighting is changed to give different intensities and colors—and to impress visiting VIPs.

• Start in front of the Customs House (where Rue des Marchands hits Grand Rue). Face the old...

Colmar is so attractive today because of its trading wealth. And that’s what its Customs House was all about. The city was an economic powerhouse in the 15th, 16th, and 17th centuries because of its privileged trading status.

In the Middle Ages, most of Europe was fragmented into chaotic little princedoms and dukedoms. Merchant-dominated cities were natural proponents of the formation of large nation-states (proto-globalization), and they banded together for free trade and mutual defense. Rather than being ruled by some duke or prince, these “trading leagues” worked directly with the emperor.

The Hanseatic League was the super-league of northern Europe. Prosperous Colmar was a leading member of a similar but much smaller league of 10 Alsatian cities, called the Decapolis (founded 1354).

Looking up at the Customs House, imagine how this “Alsatian Big Ten” enjoyed special tax and trade privileges, including the right to build fortified walls and run their internal affairs. As “Imperial” cities, they were ruled directly by the Holy Roman Emperor rather than by one of his lesser princes. This was preferable and, by banding together, they negotiated to protect this special status and won the Holy Roman Emperor’s promise not to sell them to some other, likely more aggressive, prince. The 10 mostly Alsatian towns of the Decapolis enjoyed this status until the 17th century.

This street—Rue des Marchands—is literally “Merchants Street,” and throughout the town you’ll notice how street names bear witness to the historic importance and power of merchants in Colmar. Thirty yards in front of the Customs House, find the carved plaque in the wall at #23. This is a “stone of banishment,” declaring that the town’s merchants kicked a noble family out of Colmar, and that the family could never live here again.

Step up closer to the Customs House. Delegates of the Decapolis would meet here to sort out trade issues, much like the European Union does in nearby Strasbourg today. In Colmar’s heyday, this was where the action was. Notice the fancy green and yellow roof tiles. Note also the plaque above the door to the right with the double eagle of the Holy Roman Emperor—a sign that this was an Imperial city.

Walk under the archway to Place de l’Ancienne Douane and face the Frédéric-Auguste Bartholdi statue of General Lazarus von Schwendi—arm raised (Statue of Liberty-style) and clutching a bundle of local pinot gris grapes. He’s the man who brought that grape from Hungary to Alsace. Today pinot gris accounts for more than 15 percent of wine production here.

From here, do a 360-degree spin to appreciate a gaggle of gables. This was the center of business activity in Colmar, with trade routes radiating to several major European cities. All goods that entered the city were taxed here. Today, it’s the festive site of outdoor cafés and, on many summer evenings, fun wine tastings (open to all). Through much of the summer, local vintners each get 10 days to share their wine here at the site of the town’s medieval wine fair.

• Follow the statue’s left elbow and walk down Petite Rue des Tanneurs (not the larger “Rue des Tanneurs”). The half-timbered commotion of higgledy-piggledy rooftops on the downhill side of the fountain marks the...

These 17th- and 18th-century rooftops competed for space in the sun to dry their freshly tanned hides, while the nearby river channel flushed the waste products. When the industry moved out of town, the neighborhood became a slum. It was restored in the 1970s—Colmar was a trendsetter in the government-funded renovation of depressed old quarters. Residents had to play along or move out. At the street’s end, carry on a few steps, and then turn back. Notice the openings just below the roofs where hides would be hung out to dry. Stinky tanners’ quarters were always at the edge of town. You’ve stepped outside the old center and are looking back at the city’s first defensive wall. The oldest and lowest stones you see in the buildings are from 1230, now built into the row of houses; later walls encircled the city farther out.

• Walk with the old walls on your right to the first street, Rue des Tanneurs. Turn left (at the Old Market Hall), then cross the bridge for an iconic Colmar view. Turn right onto Quai Poissonnerie and walk to the next bridge, where you’ll re-cross the river to enter the market hall on its far side.

Colmar’s historic market hall is where locals have come since 1865 to buy fish, produce, and other products (originally delivered by flat-bottomed boat). You’ll find picnic fixings and produce, sandwiches and bakery items, wine tastings, and clean WCs. Several stands are run like cafés, and there’s even a bar (Tue-Sat 8:00-18:00, Sun 10:00-14:00, closed Mon). Outside, on the market hall’s northwest corner at Rue des Ecoles, find the fountain with a copy of Bartholdi’s joyful sculpture, Le Petit Vigneron (Young Alsatian Wine Grower).

• Return to the flower-bedecked Rue des Ecoles bridge and turn right on Rue de la Poissonnerie. Follow the flower-box-lined canal leading into...

This neighborhood, a collection of Colmar’s most colorful houses lining the small canal, is popular with tourists during the day. But at night it’s romantic, with fewer crowds. It lies between the town’s first wall (built to defend against arrows) and a later wall (built in the age of gunpowder). Medieval towns needed water. If they weren’t on a river, they’d often redirect parts of nearby rivers to power their mills and quench their thirst. Colmar’s river was canalized this way for medieval industry—to provide water for the tanners, to allow farmers to barge their goods into town (see the steps leading from docks into the market hall), and so on.

• As you stroll, notice the picturesque...

The pastel colors on these buildings date from this generation—designed to pump up the cuteness of Colmar for tourists. But the houses themselves are historic and real as can be. See the sidebar to learn more about this unique architectural style.

Enjoy the creaky houses toward the end of Rue de la Poissonnerie, as the lane narrows into a sort of alleyway. When you emerge, on your right is “Pont de Fanny,” a bridge so popular with tourists for its fine views that you see lots of fannies lined up along the railing. Walk to the center of the bridge and add yours to the scene. Look for examples of the flat-bottomed gondolas used to transport goods on the small river. Today, they give tourists sleepy, scenic, 30-minute canal tours (described on here).

• Cross the bridge, walk a short block, and find a fountain in the square to your left.

Another Bartholdi work, this one was commissioned to honor Jean Roesselmann, a 13th-century town provost who died defending his beloved city when the bishop of Strasbourg tried unsuccessfully to seize it.

• Take the second right leading from the square onto...

Walk for several blocks to the Customs House where this walk began. As you stroll, enjoy the Alsatian architecture and be thankful that WWII bombs spared this town. (Freiburg, about this size, just over the border in Germany, was 80 percent destroyed and consequently has very little of this Old World charm.)

With your back to the Customs House, look uphill along 8 Rue des Marchands—one of the most beautiful intersections in town. (The ruler of Malaysia was so charmed by this street that he had it re-created in Kuala Lumpur.)

• Walk uphill on Rue des Marchands for a couple of blocks, and you’ll come face-to-face with the...

This richly decorated merchant’s house dates from 1537. Here the owner displayed his wealth for all to enjoy (and to envy). The external spiral-staircase turret (with slanted windows), a fine loggia on the top floor, and the bay windows (called oriels) were pricey add-ons. The painted walls indicate this guy was one of those big-city liberal elites with a taste for Renaissance humanism.

The cozy wine shop, Vinum, on the ground floor sells fine wines, but they’re actually most proud of their locally made whisky. The staff enjoys offering tastings, so go ahead, take a hit and see what you think—ask, “Goûter un whisky Alsatian?” (goo-tay unh wee-ski al-sah-see-unh?)

Now that you’re in a happy mood, stand outside facing the Pfister House for a little review. Find the four main styles of Colmar architecture: Gothic (move to the right to see a part of the church), medieval half-timbered structures, Renaissance (that’s Mr. Pfister’s place), and (across the lane on your right) the urbane and elegant shutters and ironwork of Paris from the 19th century.

• As you move past the spiral staircase, check out the attached building (at #9).

The man carved into the side of this building was a drapemaker; he’s shown holding a bar, Colmar’s local measure of about one meter (almost equal to a yard). In the Middle Ages, it was common for cities to have their own units of length; it’s one reason that merchants supported the “globalization” efforts of their time to standardize measuring systems.

The building shows off the classic half-timbered design—the beams (upright, cross, angular supports) are grouped in what’s called (and looks like) “a man.” Typical houses are built with a man in the middle flanked by two “half men.”

Two doors farther up the street on the left is the 11 Bartholdi Museum, located in the home of the famous sculptor Frédéric-Auguste Bartholdi, creator of the Statue of Liberty. If it’s open, step into the courtyard and admire the bronze statue called The Grand Pillars of the World (for more on the museum, see here).

Next door (at #28) is an inviting café, Au Croissant Doré, with a charming Art Nouveau facade, delicate interior, and friendly staff.

• A passage opposite the Bartholdi Museum leads you through the old guards’ house to the...

The city’s cathedral-like church replaced a smaller Romanesque church that stood here earlier. It was erected in 1235 after Colmar became an Imperial city and needed a bigger place of worship. Colmar’s ruler at the time was Burgundian, so the church has a Burgundian-style tiled roof. Walk to your right to see the stork nest atop the church’s apse. Two storks have made this nest their home, and locals have named the pair Martin and Martine.

The side door still has the round Romanesque tympanum, starring St. Martin, from the earlier church. Notice how it fits into the pointed Gothic arch. This was the lepers’ door—marked by the four totem-like rows of grotesque faces and bodies. They could “go to church” but had to stay outside, away from other parishioners.

Walk left, under three expressive gargoyles, to the west portal. Facing the front of the church, notice that the relief over the main door depicts not your typical Last Judgment scene but the Three Kings who visited Baby Jesus. The Magi, whose remains are nearby in the Rhine city of Cologne, Germany, are popular in this region. The church’s beautiful Vosges-stone exterior radiates color in the early evening. The dark interior holds a few finely carved and beautifully painted altarpieces.

• Continue past the church, go left around Jupiler Café, and wander up the pedestrian-only Rue des Serruriers (“Locksmiths Street”) to the...

Compare the Church of St. Martin’s ornate exterior with this simple Dominican structure. While both churches were built at the same time, each makes different statements. The “High Church” of the 13th century was fancy and corrupt. The Dominican order was all about austerity. It was a time of crisis in the Roman Catholic Church. Monastic orders (as well as heretical movements like the Cathars in southern France) preached a simpler faith and way of life. In the style of St. Dominic and St. Francis, they tried to get Rome back on a Christ-like track. This church houses the exquisite Virgin in the Rosebush by Martin Schongauer (described on here). If the church is open, pop in to see this exquisite painting; it takes just a few minutes and is a highlight of the town.

• Continue straight past the Dominican Church, where Rue des Serruriers becomes Rue des Boulangers—“Bakers Street.” Stop at #16.

The towering green-and-brown house, dating from the 16th century, was one of Colmar’s tallest buildings from that age. Notice how it contrasts with the string of buildings to the right, which are lower, French-style structures—likely built after a fire cleared out older, higher buildings.

As this is Bakers Street, check out the one right here at #16. Maison Alsacienne de Biscuiterie sells traditional biscuits (cookies), including boxed Christmas delights year-round. Macarons and biscuits are sold by weight.

• Turn right on Rue des Têtes (notice the beautiful swan sign over the pharmacie at the corner). Walk a block to the fancy old house festooned with heads (on the right) and cross the street to view its facade.

Colmar’s other famous merchant’s house, built in 1609 by a big-shot winemaker (see the grapes hanging from the wrought-iron sign and the happy man at the tip-top), is playfully decorated with about 100 faces and masks. On the ground floor, the guy showing his bellybutton in the window’s center has pig’s feet.

Look four doors to the right to see a bakery sign (above the big pretzel), which shows the boulangerie basics in Alsace: croissant, Kugelhopf, and baguette. Notice the colors of the French flag indicating that this house supported French rule.

Behind you, study the early-20th-century store sign trumpeting the tasty wonders of a butcher who once occupied this spot (with the traditional maiden with her goose about to be force-fed).

• Continue another block to a peaceful square where a canal runs under linden trees. Our walk is over. The venerable church and convent on your left house Colmar’s top attraction, the 16 Unterlinden Museum (entrance is on the right side of the building, across from the TI).

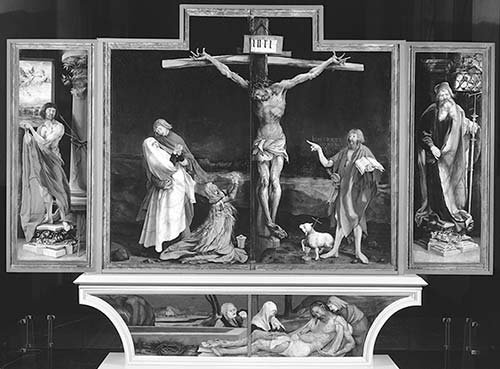

This museum is Colmar’s touristic claim to fame. Its extensive yet manageable collection ranges from Roman Colmar to medieval winemaking exhibits to Monet and Renoir, and from traditional wedding dresses to paintings that give vivid insight into the High Middle Ages. But its highlight is one of the most unforgettable masterpieces of medieval Europe: Matthias Grünewald’s gloriously displayed Isenheim Altarpiece.

Cost and Hours: €13, Wed-Mon 9:00-18:00, until 20:00 first Thu of month, closed Tue, good audioguide-€2, 1 Rue d’Unterlinden, +33 3 89 20 15 50, www.musee-unterlinden.com.

Self-Guided Tour

Self-Guided TourThe museum has three parts: the 13th-century convent cloisters and chapel (where you’ll spend most of your time), the underground galleries, and the new Ackerhof wing (modern art and temporary exhibits).

• After showing your ticket, step into the...

Cloister (Cloître): This soothing space was the largest 13th-century cloister in Alsace. Because the nuns didn’t leave the convent, this cloister was the one place they could feel the air and see the sky. This Dominican convent, founded by (and for) noblewomen in 1230, functioned until the French Revolution, when the building became a garrison.

• Rooms with museum exhibits branch off from the cloister.

Medieval and Renaissance Art: Keep straight to find the first room, dedicated to Marin Schongauer, a local artist who painted multipaneled altarpieces and became famous as an engraver. His most famous work—the Virgin in the Rosebush—is displayed in Colmar’s Dominican Church, but the Unterlinden Museum claims the largest collection of his paintings.

As you enjoy the medieval and Renaissance art displayed in this part of the museum, remember that Alsace was historically German and part of the upper Rhine River Valley. The Three Kings (of Bethlehem fame) are prominently featured throughout this region because their remains are believed to have ended up in Cologne’s cathedral (nearby, on the Rhine). Throughout the museum you’ll see small photos of engravings, illustrating how painters were influenced by other artists’ engravings (such as Schongauer’s). Most German painters of the time were also engravers (that’s how they made money—engraving versions of their art that could be duplicated to maximize sales).

• In the next room find the small...

15th-Century Stained-Glass Windows: Note the fine details painted into the glass, originally intended for “God’s eyes only”—they were too tiny for worshippers to see from the floor below. The glass is a jigsaw puzzle connected by lead. Around here, glass this old is rare—most of it was destroyed by rampaging Protestants in the religious wars following the Reformation.

• Next comes Grünewald’s gripping...

Isenheim Altarpiece (c. 1515): This remarkable work is actually a polyptych—a series of two-sided paintings on hinges that pivot like shutters. As the church calendar progressed, priests would change which parts of the altarpiece were visible to the congregation by opening or closing these panels. (The museum has disassembled the altarpiece so that visitors can view all the individual panels. To understand how the altarpiece was originally put together, see the models on the side walls.)

Designed to help people in a medieval hospital endure horrible skin diseases (specifically St. Anthony’s Fire, later called rye ergotism)—long before the age of painkillers—this altarpiece is one of the most powerful paintings ever produced. Germans know it like Americans know the Mona Lisa.

• Invest the time here to study each panel (and if you have the museum’s audioguide, listen to each one described).

Panel 1, Crucifixion: Stand in front of this panel as if you were a medieval peasant, and feel the agony and suffering of the Crucifixion. It’s an intimate drama. Jesus’ suffering and death are drilled home: The horizontal crossbar bends not so much from Jesus’ weight as from his agony. His stretched, extended arms are pulled from their sockets, his fingers grotesquely contorted in pain—reminding the faithful that Jesus suffered for them. His mangled feet are swollen with blood. In turn, the intended viewers—the hospital’s patients—would have felt that Jesus understood their distress, because he looks like he has a skin disease (though the marks on his body represent lash marks from whipping).

Study the faces and the Christian symbolism. The composition of the trio on the left is as sorrowful as it is powerful. John the Evangelist supports a swooning, white-faced Mary; she’s wrapped in the white shroud that will cover Jesus’ body in the tomb. Mary Magdalene, overcome by anguish, is on her knees. On the right, John the Baptist is shown with a little lamb—the symbol of Jesus’ sacrifice.

The outer panels feature two saints who helped the sick: St. Sebastian (on the left, called upon by those with the plague) and St. Anthony (on the right, called upon by those with ergot poisoning from rotten rye).

The predella (the horizontal painting below) shows the Lamentation over Jesus. His mourners wring their hands in sorrow. Jesus’ fingernails are black—as is the case with any corpse—and the cruel crown of thorns now rests at his feet.

• Walk around to the other side of this panel.

Panels 2-3, Resurrection and Annunciation: The Resurrection scene on the left is unique in art history. (Grünewald was a mysterious genius—an artistic loner who had no master and no students.) Jesus rockets out of the tomb as man is transformed into God. As if proclaiming once again, “I am the Light,” he is radiant. His shroud is the color of light: Roy G. Biv. Within the rainbow is the “resurrection of the flesh.” Jesus’ perfect white flesh would have offered hope to the patients who meditated on this. The happy finale is a psychedelic explosion of Resurrection joy.

The right panel depicts the Annunciation. The angel (accompanied by a translucent dove—barely visible—representing the Holy Spirit) is telling Mary she’ll give birth to the son of God. The normally sanguine Mary looks unsettled. She’s shown reading the Bible passage that tells of this event.

• Now turn around to see...

Panels 3-4, Nativity and Concert of Angels: Grünewald set his nativity scene (on the right) in the Rhineland, in a landscape that would have been familiar to him and the viewers of his artwork. The tender, loving, and much-adored Mary cradles (an unusually oversized) Baby Jesus—true to the Dominican belief that she was the intercessor for all in heaven. The infant plays with a rosary—a newly popular device in the late 15th century for organizing one’s prayers. Two angels tell shepherds of the birth while God, high above, oversees the victory of good over evil. The heavenly jam session (on the left) is the Concert of Angels.

• Walk around to view the reverse side.

Panels 4-5, Temptation of St. Anthony and St. Anthony Visits St. Paul: Looking at these last panels, zoom in on the agonizing Temptation of St. Anthony (on the left). Anthony is being ravaged by demons who look like the cast of an animated horror film. The figure in the lower left corner embodies the condition of those seeking treatment for St. Anthony’s Fire. His left arm has rotted to a stump, and his skin is a torturous mess. God the Father appears high above, as if coming to the rescue, consistent with a Christian message of hope. The scene on the right is set in the desert of Thebes; Anthony visits St. Paul, the hermit (wearing a spiffy palm-frond cloak) amid trees covered in lichen.

• Finally, turn around to see the sculpted part of the altarpiece.

Panel 6, St. Anthony on His Throne: Carved in wood by Nikolaus Hagenauer, St. Anthony sits on his throne like a king, flanked by church fathers St. Augustine (left) and St. Jerome (right). Small mortals bring gifts—a chicken and a pig. Below, Jesus shares a last supper with his 12 apostles.

• Nearby steps lead up to an exhibit of...

Decorative and Folk Art: This exhibit circles the cloister from one floor above and deserves a look. You’ll see wrought-iron signs, cast-iron ovens, massive church bells, and chests with intricate locking systems. There are also ornate armoires, medieval armor, muskets, pottery, kitchen tools, and antique jewelry boxes.

• Double back to the museum entry, and go down one floor to find...

Gallo-Roman Archaeology and Gothic Art: Follow Archéologie signs and find a room dedicated to the Mosaic of Bergheim, a portion of a luxurious mosaic from a third-century Roman villa in the town of Bergheim, which was discovered and moved here in 1848. It’s surrounded by Gallo-Roman carvings from the same age.

The next two rooms display 14th-century Gothic statues and capitals from Colmar’s Church of St. Martin and other area churches. Study the exquisite Romanesque detail of the capitals and the faces of the statues. Notice how some faces look eerily realistic, while others seem very stylized. Even though they endured the elements outdoors for more than 500 years, it’s still clear that they were sculpted with loving attention to detail. The masons knew their fine stonework would not be seen from below—it was, again, “for God’s eyes only.” The reddish stone is quarried from the Vosges Mountains, giving these works their unusual coloring. Notice the faint remnants of paint still visible on some statues—then imagine all of these works brightly painted.

• In the next rooms you’ll see a painting by Lucas Cranach and more fine stained glass windows. Farther on, don’t miss the...

Alsatian Cellar (Cave Alsacienne): Open the door into this dark, shrine-like wine room containing 17th-century oak presses (once turned by animals) and finely decorated casks. Wine revenue was used to care for Colmar’s poor. Nuns owned many of the best vineyards around, and production was excellent. So was consumption. Find the cask with Bacchus and his big tummy straddling a keg. The quote from 1781 reads: “My belly’s full of juice. It makes me strong. But drink too much and you lose dignity and health.”

• Drop down another level to find...

The Rest of the Museum: Follow signs reading Arts 19e-20e siècles to find a gallery showcasing 19th- and 20th-century paintings, including works by Monet, Renoir, Leger, Bonnard, and Dubuffet. One floor up from this gallery is the museum’s small modern art collection, including a work by Picasso and a copy of his Guernica painting by another artist. The Ackerhof and Piscine sections house more modern art and temporary exhibits.

This beautiful Gothic church is simple—in keeping with the austerity integral to the Dominican style of Christianity. It’s plain on the outside and stripped-down on the inside. Instead of gazing at art, worshippers would focus on the word of God preached from the pulpit.

Cost and Hours: €2, April-Dec daily 10:00-13:00 & 15:00-18:00, June-Oct Fri-Sat no midday closure, closed Jan-March, +33 3 89 41 27 20.

Visiting the Church: A mesmerizing medieval masterpiece—Martin Schongauer’s angelically beautiful Virgin in the Rosebush (1473), which looks as if it were painted yesterday—captivates visitors. Here, graceful Mary is shown as a loving and welcoming mother. Jesus clings to her, reminding the viewer of the warmth of his relationship with Mary. The Latin on her halo reads, “Pick me also for your child, O very Holy Virgin.” Rather than telling a particular Bible story, this is a general scene, designed to meet the personal devotional needs of any worshipper.

Nature is not a backdrop; Mary and Jesus are encircled by it. Schongauer’s robins, sparrows, and goldfinches bring extra life to an already impressively natural rosebush. The white rose (over Mary’s right shoulder) anticipates Jesus’ crucifixion. Angels hold Mary’s heavenly crown high above. The frame, with its angelic orchestra, dates only from 1900 and feels to me a bit over-the-top...as Neo-Gothic tends to be.

The painting was located in the Church of St. Martin until 1972, when it was stolen. It was recovered, then moved to the better-protected Dominican Church. Detailed English explanations are in the nave to the right of the painting as you face it. The contrast provided by the simple Dominican setting heightens the elegance of this Gothic masterpiece.

As for the rest of the church, the columns are thin to allow worshippers to see the speaker, even if the place is packed. The windows are precious 14th-century originals depicting black-clad Dominican monks busy preaching. Notice how windows face the sun on the south side while the north side is walled against the cloister. If you look at the columns in the rear of the nave, you can see how 14th-century Colmar’s street level was about two feet below today’s.

This little museum recalls the life and work of the local boy who gained fame by sculpting America’s much-loved Statue of Liberty. Frédéric-Auguste Bartholdi (1834-1904) was a dynamic painter/photographer/sculptor with a passion for the defense of liberty and freedom. Although Colmar was his home, he spent most of his career in Paris, refusing to move back here while Alsace was German. While Lady Liberty is his most famous work, you’ll see several enjoyable Bartholdi statues gracing Colmar’s squares.

The entry courtyard is free and dominated by a bronze statue, Les Grands Soutiens du Monde (The Great Pillars of the World). It was cast in 1902—two years before Bartholdi died—and shares his personal philosophy. The world is supported by three figures representing patriotism, hard work, and justice. Mr. Hard Work holds a stack of books, symbolizing intellectual endeavors, and a hammer, a sign for physical labor. Ms. Justice has her scales. And Mr. Patriotism holds a flag and a sword—sheathed but ready to be used if necessary. All have one foot stepping forward: ahead for progress, the spirit of the Industrial Age.

Cost and Hours: €7, March-Dec Wed-Mon 10:00-12:00 & 14:00-18:00, closed Tue and Jan-Feb, audioguide-€2, in heart of the old town at 30 Rue des Marchands, +33 3 89 41 90 60, www.musee-bartholdi.fr. Curiously, even though entry is free on the Fourth of July, there are no English descriptions posted. The English handout near the ticket desk gives ample background about the artist but little room-by-room information.

Visiting the Museum: As you tour the museum, notice how Bartholdi’s patriotic pieces tend to have one arm raised—Vive la France...God bless America...Freedom!

Ground Floor: You’ll see exhibits covering Bartholdi’s works commissioned in Alsatian cities (including nine for Colmar), commonly dedicated to city bigwigs and military heroes. The highlight is the Young Alsatian Wine Grower who, guzzling from his small cask, offers a fun contrast to Bartholdi’s more staid subjects.

First Floor: Climbing the stairs, you’ll pass a portrait of the artist at the first landing. Rooms to the left re-create Bartholdi’s high-society flat in Paris. The red-carpeted dining room is lined with portraits of his aristocratic family. In the far corner room, find two beautiful portraits by Jean Benner—paintings of the sculptor and another of his mother, who sits on a red chair. Bartholdi is depicted facing his mother, with whom he was very close: He wrote her daily letters while working in New York. Many see his mother’s face in the Statue of Liberty.

In the long hallway leading past the staircase, a room dedicated to Bartholdi’s most famous French work, the Lion of Belfort, celebrates the Alsatian town that fought so fiercely in 1871 that it was never annexed into Germany. Photos show the red sandstone lion sitting regally below the mighty Vauban fortress of Belfort—a symbol of French spirit standing strong against Germany. Small models give a sense of its gargantuan scale. (If you’re linking Burgundy with Alsace by car, you’ll pass the city of Belfort and see signs directing you to the Lion.)

The rest of the floor shows off Bartholdi’s other French works. Small wax models let you trace his creative process. Glass cases are filled with the tools of his trade. The last room shows sculptures of important figures in French history—the statue of Vercingétorix is wild and mesmerizing.

Second Floor: The next (and top) floor is dedicated to Bartholdi’s American works—the paintings, photos, and statues that Bartholdi made during his many travels to the States. You’ll see statues of Columbus pointing as if he knew where he was going, and Lafayette (who was only 19 years old when he came to America’s aid) with George Washington.

One room is dedicated to the evolution and completion of Bartholdi’s dream of a Statue of Liberty. The sculptor devoted years of his life to realizing the vision of a statue of liberty for America that would stand in New York City’s harbor. Fascinating photos show the Eiffel-designed core in Bartholdi’s French workshop, the frame being covered with plaster, and then the hand-hammered copper plating, which was ultimately riveted to the frame. The statue was created in Paris, then dismantled and shipped to New York in 1886...10 years late. The big ear in the exhibit is half-size.

Though the statue was a gift from France, the US had to come up with the cash to build a pedestal. This was a tough sell, but Bartholdi was determined to see his statue erected. On 10 trips to the US, he worked to raise funds and lobbied for construction, bringing with him a painting (shown here) and a full-size model of the torch—which the statue would ultimately hold. (Lucky for Bartholdi and his cause, his cousin was the French ambassador to the US.)

Eventually, the project came together—the pedestal was built, and the Statue of Liberty has welcomed waves of immigrants into New York ever since. Thank you, Frédéric-Auguste Bartholdi.

No one would come to Colmar solely for its nightlife. But if you’re out after dinner, there are a few good old town options.

Floodlit Town Stroll: Colmar puts lots of creative energy into its floodlit cityscapes, making evening strolls memorable. You could retrace the route of this chapter’s guided walk simply to enjoy the lights and architecture.

Wine Festival Stalls: Every July and August, five local vintners take 10 days each to show off local wines at a small wine festival. It’s held under the historic arches of the Customs House (daily 12:00-23:00, self-service, no food, great prices for nice wine).

Folk Dance Tuesdays: On Tuesdays in May to September, there’s likely Alsatian folk dancing at the town’s Folklore Evening (Soirée Folklorique, starts at 20:30) to give your wine tasting a little color.

Bar Scene: Rue du Conseil Souverain (stretching from the Customs House to the “Pont de Fanny”) has a fun run of watering holes where you can enjoy mellow outdoor seating with the locals on balmy evenings or interiors of your choice when it’s cold. Les Incorruptibles attracts younger locals, with a DJ on weekends, some Alsatian edginess, and gourmet Belgian beers (1 Rue des Ecoles). Pub James’On has a big, pubby-warm interior and draws a marginally more mature crowd (2 Rue du Conseil Souverain). Sport’s Café is a big-screen, Red Bull-and-foosball place. This is the place to be if there’s a big sporting event on TV and you want to share it with a gang of French enthusiasts (3 Rue du Conseil Souverain). J. J. Murphy’s Irish Pub, a short block away, invites you to take a trip to Ireland at the bar, where you can enjoy a classic pub vibe and Murphy’s Irish Stout on tap (48 Grand Rue).

Hotels are a reasonable value in Colmar. They’re busy on weekends in May, June, September, and October, and every day in July and August. Hotels have air-conditioning, buffet breakfasts, and elevators unless otherwise noted. If you have trouble finding a bed, ask the TI for help or look in a nearby village, where small hotels and bed-and-breakfasts are plentiful (see my recommendations in nearby Eguisheim, later).

$$$ Hôtel Quatorze**** is a high-end boutique hotel blending sleek, daringly modern design and a central location. It offers 14 rooms tucked behind a quiet patio (14 Rue des Augustins, +33 3 89 20 45 20, www.hotelquatorze.com, info@hotelquatorze.com).

$$$ Hostellerie le Maréchal,**** in the heart of La Petite Venise, holds Colmar’s most characteristic rooms. Though the rooms are on the small side (three-star quality and prices), the setting is romantic, the decor is warm, and the service is professional (pay garage parking, 4 Place des Six Montagnes Noires, +33 3 89 41 60 32, www.le-marechal.com, info@le-marechal.com). The hotel is famous for the quality of its well-respected $$$$ restaurant; many French clients travel to dine here (€50-100 menus, reserve ahead).

$$ Hôtel Turenne*** is less central (a 10-minute walk from the city center) and greets you with a big, open lobby, interior patio, and top service. Its 90 very comfortable rooms are split between an older, more traditional wing (cheaper) and a new wing with more modern rooms. All rooms are well-appointed and come with access to a spa and secure private parking (family rooms, 10 Route de Bâle, +33 3 89 21 58 58, www.turenne.com, infos@turenne.com).

$$ Grand Hôtel Bristol**** has little personality but works if you want American-like comfort at the train station with a spa and fitness room (7 Place de la Gare, +33 3 89 23 59 59, www.grand-hotel-bristol.com, reservation@grand-hotel-bristol.com).

$ Hôtel St. Martin,*** ideally situated near the old Customs House, is a family-run place that began in 1361 as a coaching inn. It has 40 mostly traditional, well-equipped rooms with big beds. The rooms are woven into its antique frame and joined together by a small courtyard (some rooms with no elevator access, family rooms, limited free public parking nearby at Parking de la Vieille Ville/Montagne Verte, pay parking in private garage at Parking Josse, 38 Grand Rue, +33 3 89 24 11 51, www.hotel-saint-martin.com, colmar@hotel-saint-martin.com).

$ Hôtel Ibis Colmar Centre,*** on the ring road, is economical—renting tight rooms with small bathrooms at acceptable rates (10 Rue St. Eloi, +33 3 89 41 30 14, https://ibis.accorhotels.com, h1377@accor.com).

$$ Hôtel le Rapp,*** conveniently located off Place Rapp and near a big park, offers rooms for many budgets, a full-service bar and a good restaurant. The cheapest rooms are tight but smartly configured; the bigger rooms are tasteful, usually with king-size beds. There’s also a small basement pool, a sauna, and a Turkish bath (family rooms, 1 Rue Weinemer, +33 3 89 41 62 10, www.rapp-hotel.com, rapp-hotel@calixo.net). The $$ Restaurant le Rapp is a traditional place to savor a slow, elegant meal served with grace and fine Alsatian wine (closed Sun-Mon).

¢ Maison Martin Jund holds my favorite budget beds in Colmar. This ramshackle yet historic half-timbered house—the home of likeable winemakers André and Myriam and their grown kids—feels like a medieval treehouse soaked in wine and filled with flowers. The rooms are humble but spacious and comfortable enough. Some have air-conditioning and many have kitchenettes (big family apartments, fun tasting room—see “Helpful Hints” earlier, no elevator, 12 Rue de l’Ange, +33 3 89 41 58 72, www.martinjund.com, myriam@location.alsace). Leave your car at Parking de la Mairie. There is no real reception—though good-natured Myriam or her daughter Cécile will likely be around (call if arriving after 20:00).

¢ Ibis Budget Hôtel offers bright, efficient, cookie-cutter rooms with three beds—one bed is a bunk—and ship-cabin bathrooms (secure pay parking, 10-minute walk from city center at 15 Rue Stanislas, +33 8 92 68 09 31, https://ibis.accorhotels.com], h5079@accor.com).

Colmar is full of good restaurants offering traditional Alsatian or creative French menus for €20-35. Worth careful consideration (and reservations) are: L’Arpège (fun and foodie), Wistub de la Petite Venise (romantic Alsatian), Cour des Anges (foodie, Bohemian-mellow), and L’un des Sens (peaceful wine bar with Alsatian tapas).

The venerable Customs House, with a canal cutting right behind it on Place de l’Ancienne Douane, marks the touristic and historic center of Colmar. Dine here under the stars on a balmy evening to enjoy the floodlit scene of half-timbered buildings and strolling musicians. While you’ll be sitting side-by-side in a mosh pit of tourists, it’s hard to beat the location and fun vibe.

$ Cour des Anges is an easygoing delight serving organic, locally grown products to discerning regulars in a quiet Alsatian courtyard or cozy interior just steps away from the tourist mobs. The chef “revisits” traditional dishes in tasty ways. Order family-style here to maximize the experience—sharing delicious salads, homemade tarte flambée, “revisited” choucroute or crêpes, and more (closed Sun-Mon, 4 Place de l’Ancienne Douane, +33 3 89 24 98 02).

$ Brasserie Schwendi has fun, German pub energy inside with six beers on tap and hustling waiters. The big terrace with tight, regimented seating fills up on warm evenings. Choose from a dozen filling, robust Swiss Rösti plates or tarte flambée—I like the strasbourgeoise flambée (daily 12:00-22:30, facing the Customs House at 3 Grand Rue, +33 3 89 23 66 26).

$ Crep’ Stub Crêperie Caveau is my favorite for crêpes in the old center, with great outside seating—at the gray tables around the big tree on Place de l’Ancienne Douane—or inside in a cute little back room (daily for lunch, closed Sun-Mon for dinner, 10 Rue des Tanneurs, +33 3 89 24 51 88).

$$ La Maison Rouge, with a folk-museum interior and sidewalk seating, has reasonably priced, beautifully presented Alsatian cuisine and an understandably loyal following. You’ll be greeted by a jambon à l’os—ham cooking on the bone (try the veal cordon bleu with Munster, daily, 9 Rue des Ecoles, +33 3 89 23 53 22).

$$$ Aux Trois Poissons is an intimate and refined place across from the old market hall without a hint of Alsatian decor or cuisine (pleasant indoor and outdoor seating). The traditionally French menu emphasizes fish, though meat dishes are also available (tasty steak tartare, closed Sun-Mon, 15 Quai de la Poissonnerie, +33 3 89 41 25 21).

$$ Wistub de la Petite Venise’s caring owners Virginie and Julien buck the touristy trend, combining a wood-warm, chalet ambience with the energy of an open kitchen. The limited menu, heavy on the meaty classics, is reliably tasty. Chef Julien is particularly proud of his jambonneau, choucroute, and foie gras (no outside seating, closed Wed, 4 Rue de la Poissonnerie, +33 3 89 41 72 59).

$$ Wistub Brenner offers quality, seasonal specialties and attentive service in a good atmosphere. Book ahead or arrive early for a table on the fun terrace. Their formula is freedom: You can choose any first course to go along with any main course on their €30 menu deal (daily, 1 Rue Turenne, +33 3 89 41 42 33).

Lunch in Petite Venise: For the best selection of quick, inexpensive, and memorable lunch options, grab a bite in the $ Old Market Hall in Petite Venise. There are a handful of enticing little eateries to choose from and the fun atmosphere can’t be beat (Tue-Sat 8:00-18:00, Sun 10:00-14:00, closed Mon). You can also get a dish to go or a picnic and find a nice canalside perch just outside.

$$$ L’Arpège offers a special experience, like eating in a Monet painting where each waiter’s mission is to be sure you leave evangelical about Chef Jean-Martin’s cooking. He gives classic French dishes a creative modern twist with seasonal and organic ingredients, always respects the vegetarians with a serious dish, and finishes with a delightful dessert. Inside you’ll enjoy candlelight and sleek rocking chairs. Outside, you dine in a homey and beautifully lit garden. It’s romantic either way (reservations essentially required, closed Sun-Mon for lunch, closed Sun-Wed for dinner, 24 Rue des Marchands, +33 3 89 24 29 64, www.larpegebio.com).

$ L’un des Sens is your Midnight in Paris rendezvous—a cool little wine bar three blocks from the nearest tourist offering. You’ll discover a laid-back interior and an idyllic leafy courtyard with rickety little tables. They have a long wine list and a short food list: ideal for enjoying nice French wines with a shared tapas-style meal featuring local meats, cheeses, fancy foie gras, and a couple of hot dishes. Three small portions will likely be enough for a couple (reservations helpful, Tue-Sat 17:00-22:00, closed Sun-Mon, 18 Rue Berthe Molly, +33 3 89 24 04 37, www.lun-des-sens.alsace, helpful Chantal speaks English and serves while Annabelle does the food prep).

Sweet Tooth: Sorbetière d’Isabelle sells fine sorbet and sweets; you can eat at an outdoor table or get it to go (daily until at least 19:00, later in July-Aug and on busy weekends, near Maison Pfister at 13 Rue des Marchands).

From Colmar by Train to: Strasbourg (about 2/hour, 35 minutes), Reims (TGV to Champagne—Ardenne station: 10/day, 4 hours, most change in Strasbourg), Verdun (10/day, 4-6 hours, 2-3 changes, trips by TGV require 30-minute bus ride from Gare de Meuse), Beaune (10/day, 3.5 hours, fastest by TGV via Mulhouse, reserve ahead, possible changes in Mulhouse or Belfort and Dijon), Paris’ Gare de l’Est (12/day with TGV, 2.5 hours, 3 direct, others change in Strasbourg), Amboise (13/day, 6 hours, most with transfer in Strasbourg and Paris), Basel, Switzerland (hourly, 45 minutes), Freiburg, Germany (hourly bus to Breisach then direct train, 1.5 hours), Karlsruhe, Germany (TGV: 7/day, 2 hours, best with change in Strasbourg; non-TGV: hourly, 2-3 hours, change in Strasbourg and Appenweier or Offenburg; from Karlsruhe, it’s 1.5 hours to Frankfurt, 3 hours to Munich).

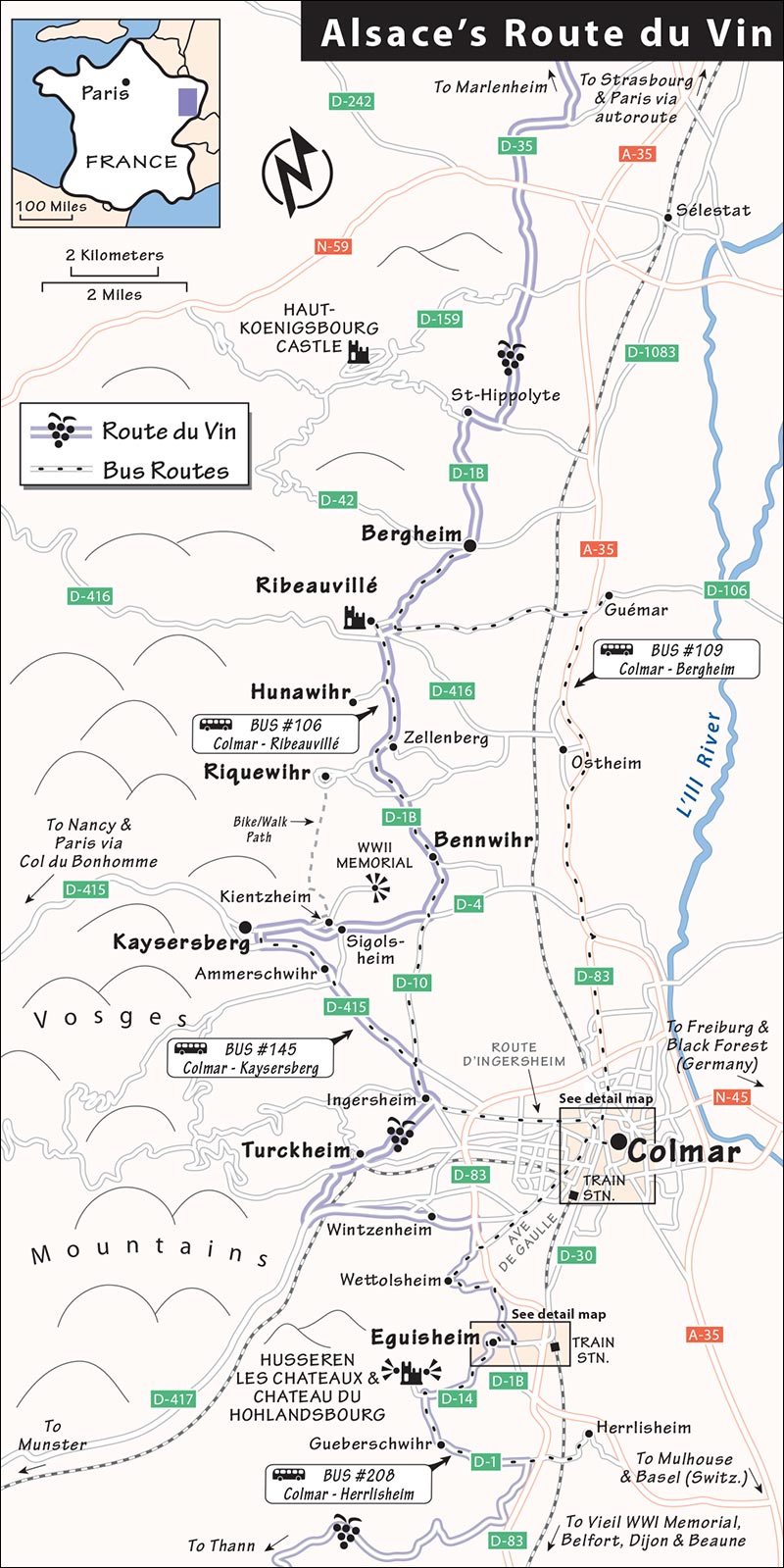

Alsace’s Route du Vin (Wine Road) is an asphalt ribbon that ties 90 miles of vineyards, villages, and medieval fortress ruins into an understandably popular tourist package. With France’s driest climate, this sunny stretch of vine-covered land has made for good wine since Roman days. Colmar and Eguisheim are well located for exploring the 30,000 acres of vineyards blanketing the hills from Marlenheim to Thann.

This is France’s smallest wine region. It’s long (75 miles) and skinny (a mile wide on average), with vineyards strategically planted between the flood line of the marshy plains and the frost line of the higher ground. Everyone scrambles for the finest land. Medieval towns grew low into regular farmland rather than high into the vineyards. Local folk wisdom reminded young brides to marry into a family that grew grapes. The region’s 50 grand cru vineyards (the highest quality) get the privilege of putting up their names on big signs along the hillsides.

The towns with evocative castle ruins are often strategically located at the ends of valleys. Their names can reveal their histories—towns ending with “heim” and “wihr” were born as farmsteads (Eguisheim was Egui’s farm, and I guess Riquewihr was the farm of a guy named Rick).

Peppering the landscape are Route du Vin villages, full of quaint half-timbered architecture corralled within medieval walls (for a practical review of what to look for as you wander through these towns, see the “Half-Timbered Houses of Alsace” sidebar, earlier). These villages take their flowers seriously. The Ville Fleurie flower competition revs up village pride through an annual contest designed to improve the beauty of the villages. Winners are awarded from one to four flower petals; these ratings are posted on signs as you enter the village. While this contest takes place throughout France, it seems particularly important in Alsace.

As you tour the Route du Vin, you’ll see stork nests on church spires and City Halls, thanks to a campaign to reintroduce the birds to this area. (Those nests can weigh over 1,000 pounds, posing a danger if they fall and forcing villagers to shore them up.) Storks make a noise something like a woodpecker. If you hear such a sound, look up: Nests can be on top of any building. Look also for crucifixion monuments scattered about the vineyards—intended to get a little divine intervention for a good harvest.

If you have only a day, focus on towns within easy striking range of Colmar. World War II hit many Route du Vin villages hard. While some of the towns are amazingly preserved from centuries past, others were entirely rebuilt after the war. It all depended on where the war went in 1944. Among the villages that emerged from World War II unscathed are the four I cover most extensively in this chapter: Eguisheim, Kaysersberg, Riquewihr, and Bergheim.

A sampling of two of the touristy villages is enough for most (visit them early to minimize crowds), then add a less-touristed place (like Bergheim or Turckheim, each of which can be seen in under an hour). Driving distances between villages are generally short. If taking a minibus tour, you can see a representative sampling in a half-day or cover the highlights of the entire region in a full day (including a few wine tastings). For those without wheels it’s more work (by bike), time-consuming (by bus), or pricier but manageable (by taxi).

Towns are most alive during their weekly morning (until noon) farmers markets (Mon—Kaysersberg and Bergheim; Fri—Turckheim; Sat—Ribeauvillé and Colmar). Riquewihr and Eguisheim have no market days.

Drivers can pick up a detailed map of the Route du Vin at any area TI. To reach the Route du Vin north of Colmar, leave Colmar following signs to Ingersheim. Look for Route du Vin signs. For the quickest way to Eguisheim from Colmar, head for the train station and take D-30 and then D-83 south toward Belfort. In general, it’s better to navigate by town names rather than road numbers.

Many drivers discreetly use some of the scenic wine-service lanes known as sentiers viticoles. If you do, drive at a snail’s pace. I’ve recommended my favorite segments.

The only Route du Vin village accessible by train from Colmar is pleasant little Turckheim (12/day, 10 minutes, described later).

Several bus companies connect Colmar with villages along the Route du Vin daily except Sunday, but deciphering schedules and locating bus stops in Colmar is tricky. I have done this for you (later), but things can change; confirm bus schedules and stop locations by asking at any TI or by using the helpful website (in English) www.vialsace.eu/en. Schedules are posted at most stops.

Buses to Route du Vin villages stop at Colmar’s train station (see under “Arrival in Colmar”) and in Colmar’s city center near the Unterlinden Museum (at the Théâtre stop—with shelters labeled quai, each identified with a letter—or a few blocks away by the cinema). The TI can show you the exact locations of these bus stops.

Here’s a rundown of service to key Route du Vin villages from Colmar (see Alsace’s Route du Vin map to locate these bus routes). Remember, there’s no Sunday service on any of these routes.

Kaysersberg has reasonable service (Kunegel bus #145, direction: Le Bonhomme, 7/day, 30 minutes, Théâtre stop Quai G). At the Colmar train station, find the last stop to the left, Quai E, as you leave the station.

Riquewihr, Hunawihr, and Ribeauvillé have decent service (bus #106, roughly 8/day, 45 minutes, big midday service gaps in summer). Buses leave from the train station (to the right as you exit) and from the bus stop near Place Scheurer-Kestner, behind the cinema on Rue de la 5ème Division (direction: Illhaeusern). See the “Colmar” map, earlier, for stop locations.

Bergheim and Ribeauvillé are served by bus #109 (roughly 4/day, 30 minutes, direction: St-Hippolyte, same bus stops as #106).

Eguisheim has one bus per day, which departs Colmar about noon and returns from Eguisheim at about 17:00 (Mon-Sat only, 15 minutes). Look for bus #208 (direction: Herrlisheim, leaves from Théâtre stop Quai F, or from the train station, to the right as you exit). Eguisheim is so close that many get there by bike or taxi.

Château du Haut-Kœnigsbourg has a shuttle bus from the Séléstat train station (explained on here).

Allow €15 from Colmar to Eguisheim (€25 round-trip) and €35 from Colmar or Eguisheim to Kaysersberg or Riquewihr. For a group of four with limited time, this is a smart option. For recommendations, see here.

The three companies listed first offer private group tours as well as these shared tours. These prices are per person.

Ophorus Tours offers well-run trips from Colmar and Strasbourg to villages along the Route du Vin that include good wine tastings, informative walking tours, and time to wander (€125/full day, €75/half-day, +33 5 56 15 26 09, www.ophorus.com).

Alsascope also offers tours departing from Colmar and Strasbourg (€120/full day, €65/half-day, mobile +33 6 82 87 50 73, www.alsascope.fr [URL inactive]).

Vinotours offers tours with a wine focus (€140/full day, €90/half-day, mobile +33 6 51 94 05 17, www.vinoroute.fr).

Mariano Ruiz is a reliable driver who speaks English and can take you around the Route du Vin, +33 6 50 70 06 33, contact@callacar.fr). Muriel Brun and Stéphan Reitter are excellent guides for the Route du Vin (see here).

Alsace is among France’s best biking regions. The Route du Vin has an abundance of well-marked trails and sentiers viticole (wine-service roads) that run up and down the slopes, offering memorable views and the fewest cars but lots of sweat (rent an electric bike). Colmar’s TI has a good bike map, and bike rental shops know all the routes. Bikers can rent in Colmar, Turckheim, Eguisheim, Kaysersberg, or Ribeauvillé. (I’ve listed rental options for each.) All but Turckheim have electric bikes for rent and all make great starting points.

Riding round-trip between Ribeauvillé and Kaysersberg via Hunawihr and Riquewihr along the upper sentier viticole yields sensational views but very hilly terrain (you can reduce some of the climbing by following lower wine-service lanes).

A bike path runs south from Colmar to Eguisheim following the river for a stretch (described on bike map available at Colmar’s TI). One of the most beautiful wine-service lanes in Alsace runs south from Eguisheim through Husseren to Gueberschwihr.

Bike tours work well, too. Service-oriented Alsa Cyclo in Eguisheim runs tours using electric bikes (€45-85 for 2-4 hours with a guide, see “Orientation to Eguisheim,” later).

Hikers can stroll along sentier viticole service roads and paths into vineyards from each town on short loop trails (each TI has brochures), or connect the villages on longer walks. Consider taking a bus or taxi from Colmar to one village and hiking to another, then taking a bus or taxi back to Colmar (Riquewihr and Kaysersberg make good combinations—see details on here). Hikers can also climb high to the ruined castles of the Vosges Mountains (Ribeauvillé is the best starting point).

Vieil-Armand WWI Memorial (Hartmannswillerkopf)

These sights are listed in the order you’ll encounter them starting from Colmar.

This is the region’s most charming village (described later).

This sweet little village 15 minutes south of Colmar sees almost no tourists and offers an excellent wine-tasting experience at Domaine Ernest Burn, where sincere Simone takes you on a tasting tour of their well-respected wines in an atmospheric tasting room (daily, best to call ahead, 8 Rue Basse, +33 3 89 49 20 68, www.domaine-burn.fr [URL inactive]). Follow the gorgeous wine lane due north from Gueberschwihr’s center to Eguisheim through Husseren.

This powerful memorial evokes the slaughter of the Western Front in World War I, when Germany and France bashed heads for years in a war of attrition. It’s up a windy road above Cernay (20 miles south of Colmar). From the parking lot, walk 10 minutes to the vast cemetery, and walk 30 more minutes through trenches to a hilltop with a grand Alsatian view. Here you’ll find a stirring memorial statue of French soldiers storming the trenches in 1915-1916—facing near-certain death—and rows of simple crosses marking the graves of those who lost their lives here.

With a picturesque square and a garden-filled moat, this quiet town is refreshingly untouristy. It’s an ideal destination for nondrivers, with quick trains from Colmar and easy bike rental. Drivers will find easy parking by the station.

Its 13th-century walls are some of the oldest in the region. Drivers and train riders enter Turckheim through its walls at the France Gate, where—once upon a time—all foreign commerce entered. Just inside the wall you’ll see the TI, offering a helpful town map with a suggested stroll (Rue Wickram, +33 3 89 27 38 44, www.turckheim.com). Turckheim’s main drag (Grand Rue) runs east from here and makes for a nice wander among bakeries and shops. Rent bikes a block past the TI at the classy Hôtel des Deux Clefs reception desk (long hours, 3 Rue du Conseil, +33 3 89 27 06 01, www.2clefs.com).

Turckheim has a rich history and has long been famous for its wines. It gained town status in 1312, became a member of the Decapolis league of cities in 1354, and was devastated in the Thirty Years’ War. In the 18th century it was rebuilt, thanks to the energy of Swiss immigrants. Reviving an old tradition, from May to October there’s a town crier’s tour each evening at 22:00 (in Alsatian and French).

Turckheim’s “Colmar Pocket” Museum (Musée Mémorial des Combats de la Poche de Colmar), chronicling the American push to take Alsace from the Nazis, is a hit with WWII buffs (€4, minimal English information; daily 14:00-18:00, Sat-Sun also 10:00-12:00; closed Nov-March; +33 3 89 80 86 66, http://musee.turckheim-alsace.com).

This is the most historic town after Colmar. It has an intriguing medieval center, Dr. Albert Schweitzer’s house, and plenty of hiking opportunities (described on here).

After this town was completely destroyed during World War II, the only object left standing was the compelling statue of two girls depicting Alsace and Lorraine (outside its modern church). The war memorials next to the statue list the names of those who died in both world wars. During World War II, 130,000 Alsatian men aged 17-37 were forced into military service under the German army (after fighting against them). Most were sent to the deadly Russian front.

This adorable town is the most touristed on the Route du Vin—and understandably so. If you find crowds tiresome, this town is exhausting (described on here).

This bit of wine-soaked Alsatian cuteness is far less visited than its more famous neighbors, and features a 16th-century fortified church that today is shared by both Catholics and Protestants (the Catholics are buried next to the church; the Protestants are buried outside the church wall). Park at the village washbasin (lavoir) and follow the path between vines up to the church, then loop back through the village. Kids enjoy Hunawihr’s small nature-conservation park, Centre de Réintroduction, where they’ll spot otters (loutre), over 150 storks (cigogne), and more (€11, daily 10:00-18:00, shorter hours April and Oct, closed Nov-March, other animals take part in the afternoon shows—times listed on website, +33 3 89 73 72 62, https://naturoparc.fr). A nearby butterfly exhibit (Le Jardin des Papillons) houses thousands of the delicate insects from around the world (€8, includes audioguide, daily 10:00-18:00, until 17:00 March-April and Oct, closed Nov-Easter, +33 3 89 73 33 33, www.jardinsdespapillons.fr).

This town, less visited by Americans, is well situated for hiking and biking. It’s a linear place with a long pedestrian street (Grand Rue). A steep but manageable trail leads from the top of the town into the Vosges Mountains to three castle ruins, and is ideal for hikers looking for a walk in the woods and sweeping views. Follow Grand Rue uphill to the Hôtel aux Trois Châteaux and find the cobbled lane leading up from there. St. Ulrich is the most interesting of the three ruins (allow 2 hours round-trip, or just climb 10 minutes for a view over the town—get info at TI at 1 Grand Rue, +33 3 89 73 23 23, www.ribeauville-riquewihr.com [URL inactive]). It’s a short, sweet, and really hilly bike loop from Ribeauvillé to Hunawihr and Riquewihr (can be extended to Kaysersberg). You can rent a bike at Ribo’ Cycles (Tue-Sat 9:00-12:00 & 14:00-18:00, Sat until 17:00, closed Sun-Mon, 17 Rue de Landau, +33 3 89 73 72 94).

With a well-preserved gate and charming architecture, sleepy Bergheim is happily untouristed. It’s my vote for the best nontouristy stop on the Route du Vin (described on here).

This granddaddy of Alsatian castles stands atop a rocky spur of the Vosges Mountains, 2,500 feet above the flat Rhine plain. From here you’ll get an eagle’s-nest perspective over the Vosges and villages below. Be aware that the castle gets hammered with visitors in high season, particularly on weekends.

Cost and Hours: €9, daily April-Sept 9:15-18:00, June-Aug until 18:45; Oct-March 9:30-17:45; Nov-Feb closes for lunch and a half-hour early; audioguide-€5, about 15 minutes north of Ribeauvillé, above St-Hippolyte, +33 3 69 33 25 00, www.haut-koenigsbourg.fr.

Tours: An English leaflet and posted descriptions give a reasonable overview of key rooms and history, but the one-hour audioguide is a good investment.

Getting There: A shuttle bus should run to the castle from the Séléstat train station (verify in advance, small fee, generally 8/day mid-April-mid-May and mid-June-mid-Sept, weekends only off-season, none Jan-mid-March, 30 minutes, timed with trains, call château for schedule or check website). Your shuttle ticket saves you €2 on the château entry fee. If driving in high season, expect to park along the road well below the castle (unless you come early). Parking can be a zoo in the summer—it’s limited to roadside spaces.

Visiting the Castle: While the elaborate castle was rebuilt barely 100 years ago, it’s a romantic’s dream, dramatically situated along its sky-high ridge. Its exhibits give helpful insight into this 15th-century mountain fortress.

Started in 1147 as an Imperial castle in the extensive network that served the Holy Roman Empire, Haut-Kœnigsbourg was designed to protect valuable trade routes. It was under constant siege and eventually destroyed by rampaging Swedes in the 17th century. The castle sat in ruins until the early 1900s, when an ambitious restoration campaign began (a model in the castle storeroom shows the castle before its renovation).

Today’s castle—well-furnished by medieval standards—highlights Germanic influence in Alsatian history with decorations and weapons from the 15th through 17th centuries. Don’t miss the top-floor Grand Bastion with its elaborate wooden roof structure and models showing its construction. There are cannons and magnificent views in all directions.

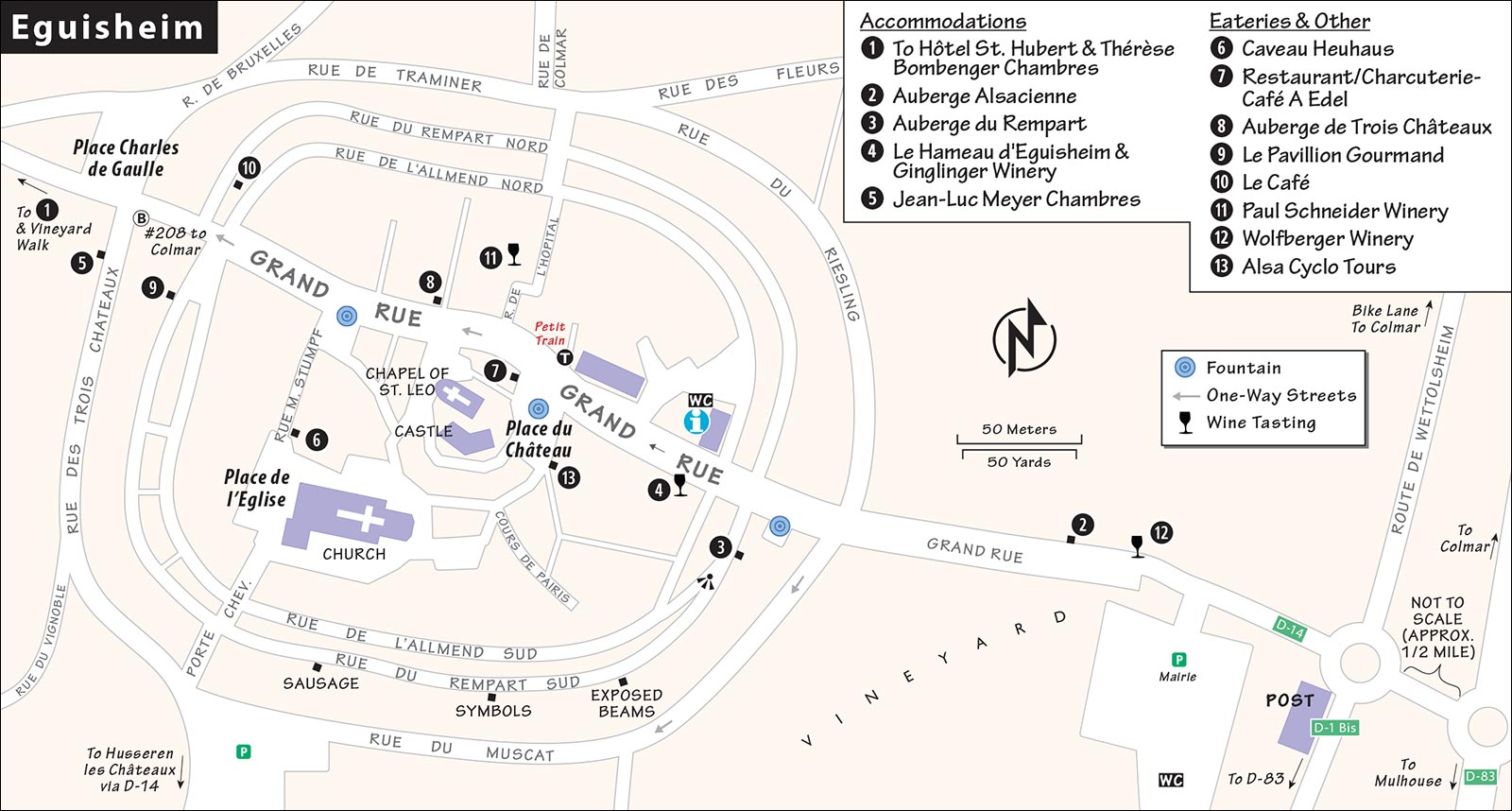

Just a few miles south of Colmar’s suburbs, this circular, flower-festooned little wine town (pop. 1,500, 33 wineries), often busy with tourists, is a delight. Come here first thing to experience the village at its peaceful best (or spend the night). In 2013 it was named France’s favorite town, adding to its touristic fame. Eguisheim (“ay-gush-I’m”) is ideal for a relaxing lunch and vineyard walks. If you have a car, it makes a good small-town base for exploring Alsace. It’s also a cinch to day-trip here by car (easy parking) or taxi (€15 from Colmar), and manageable by bike (see “Getting Around the Route du Vin—By Bike,” earlier), but barely accessible by bus.

The TI has information on bus schedules, festivals, vineyard walks, and Vosges Mountain hikes (generally Mon-Sat 9:30-12:30 & 13:30-18:00, Sun 10:30-13:30, shorter hours and closed Sun off-season, 22 Grand Rue, +33 3 89 23 40 33, www.tourisme-eguisheim-rouffach.com). They’re happy to call a taxi for you. A handy WC sits behind the TI.

Eguisheim’s bus stop is at the upper end of the village, close to Place Charles de Gaulle (see map, same stop for both directions).

The Petit Train leaves from the town center, a block east of the TI, and runs a scenic route through Eguisheim and into the vineyards (€7, 40 minutes, hourly).

Alsa Cyclo Tours is a good outfit that rents top-quality bikes with GPS and recorded directions in English (electric bike-€25/half-day, €35/day; regular bike-€15/half-day, €25/day; GPS-€3; May-Oct daily 9:00-18:00, just off the main square at 3 Rue de Pairis, +33 3 69 45 96 48 or +33 6 34 41 19 04, www.alsacyclotours.alsace). They also offer bike tours from Colmar (€45-85 for 2-4 hours with a guide, includes electric bike).

Draw a circle and then cut a line straight through it. That’s your plan with this inviting little town. The main drag (Grand Rue) cuts through the middle, with gates at either end and a stately town square in the center. And, while Eguisheim’s town wall is long gone, it left a circular lane (Rue du Rempart—Nord and Sud) lined with gingerbread-cute houses. (For more on this type of architecture, see the “Half-Timbered Houses of Alsace” sidebar in the “Colmar” section, earlier.) Rue du Rempart Sud is more picturesque than Rue du Rempart Nord, but the Nord ramparts feel more real and lived in. I’d walk the entire circle.

• Start your self-guided walk near the TI and circle the former ramparts clockwise, walking up Rue du Rempart Sud (just after the Auberge du Rempart hotel).