Different as night and day, bubbly Reims and brooding Verdun offer worthwhile stops between Paris and Alsace. The administrative capital of the Champagne region, bustling, modern Reims greets travelers with cellar doors wide open. It features a lively center, a historic cathedral, and, of course, Champagne tasting. Too-often overlooked, quiet Verdun is famous for the brutal WWI battles that surrounded the small city and pummeled its countryside, and offers an exceptional opportunity to learn about the Great War. High-speed TGV trains make these destinations accessible to all travelers.

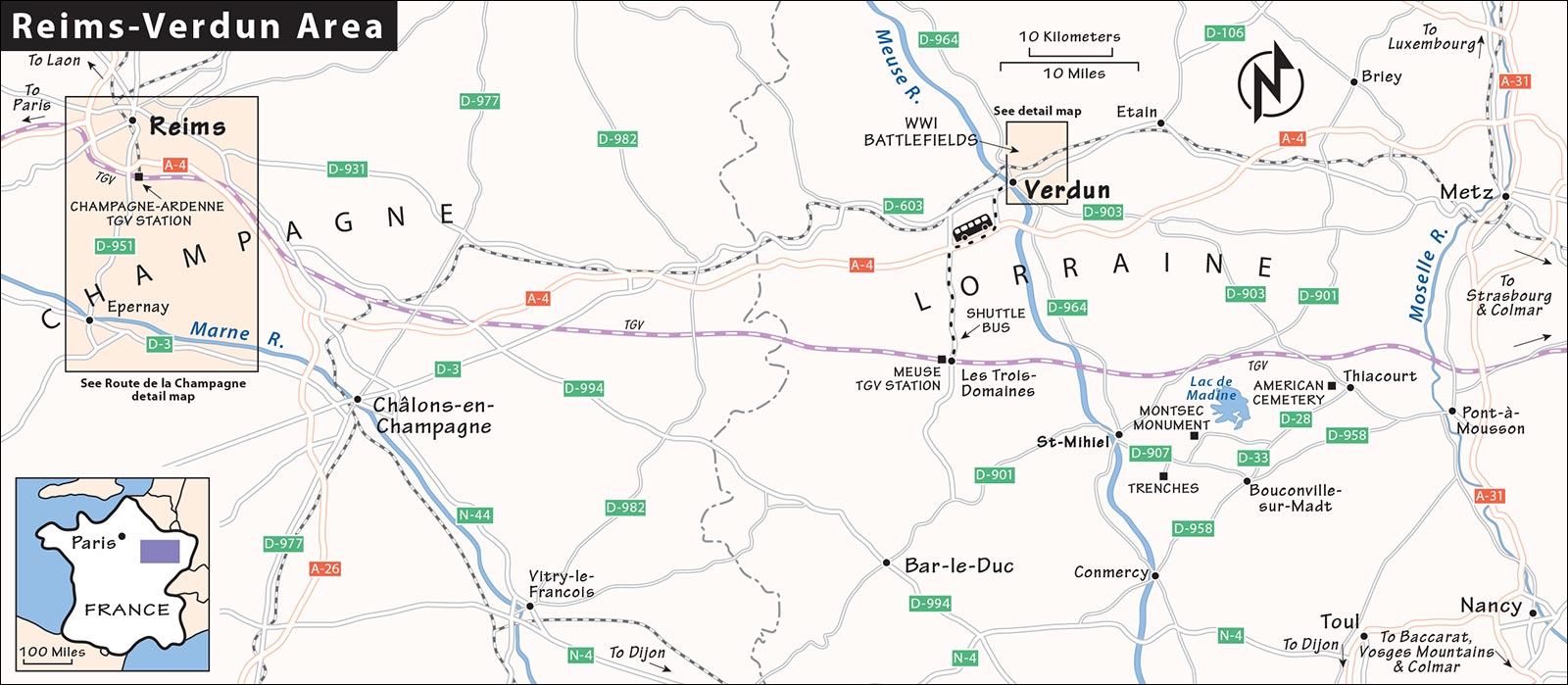

Organized travelers can see Reims and Verdun in a day and a half as they travel between Paris and the Alsace (with an overnight in Reims). Plan on most of a day for Reims and at least a half-day for Verdun. It’s about 70 miles between the two towns, making a day trip from Reims to Verdun doable if you have a car, but it’s challenging by train. Day-tripping by train from Paris to Reims is a breeze but getting to Verdun from Paris requires planning (think about spending a night).

A car is sans doubt the most efficient way to tour this region. You’ll do fine without one in Reims: The town is easily walkable, and excellent public transportation links its major sights. But for touring Verdun battlefield sights, it’s best to rent a car—whether you choose to drive yourself or arrange for a private guide to accompany you.

Many find Reims a good place to pick up a rental car for a longer trip after leaving Paris. Train travelers from Paris will reach Reims before drivers get out of the city. Verdun is just off the A-4 autoroute (an hour from Reims, 2.5 hours from Paris, and 3 hours from Colmar).

Frequent high-speed TGV trains link central Paris and Reims in 45 minutes, and a few TGV trains link Paris and Verdun in 2 hours. Several trains per day connect Charles de Gaulle Airport to Reims (via its Champagne-Ardenne train station) in about one hour. Train connections between Reims and Verdun take 1.5-3 hours each way, with 1-2 transfers.

Contrary to popular belief, Champagne is wine that can easily accompany an entire meal. Locals drink Champagne with everything here. And just as the Burgundians cook many of their meat and poultry dishes with their local red wine, the Champenois cook with bubbly (on menus you’ll see à la champenoise).

This is a “meaty” region: Most menus will offer foie gras, raw tartares, loads of beef, and some dishes you may choose to avoid, such as rognons, ris de veau, tête de veau, pieds de porc, andouillette, and boudin noir (kidneys, sweetbreads, calf’s head, pig’s feet, tripe sausage, and blood sausage, respectively). Despite its bloody reputation, I find boudin noir delicious. La potée champenoise (also called La Joute) is like a pot-au-feu stew, made of smoked ham, chicken, sausage, and vegetables with lots of cabbage. Boudin blanc is a moist, white sausage made from pork or chicken, eggs, cream, and spices. Many salads and starters include jambon de Reims, the local smoked ham. Andouillette de Troyes is a tripe sausage that you can smell from across the room. Ample rivers make for flavorful trout (truite) dishes. You may also find rooster cooked in the rare local red wine known as Bouzy Rouge (coq au vin de Bouzy).

Brie de Meaux cheese, made on Champagne’s border, is the most flavorful Brie, as it’s unpasteurized. Other local cheeses include Cendré de Champagne (similar to Brie but the size of a large Camembert, with a thin ash covering), Chaource (a young, creamy, and mild cheese in a cylindrical shape), and Langres (orange-colored rind, creamy and pungent, usually aged). All of these listed cheeses have edible rinds.

Biscuits roses de Reims (pink cookies) are on every bakery shelf in town. Traditionally dunked in Champagne, this ladyfinger-style treat also goes well with afternoon coffee or tea and is often used in local desserts, such as charlotte aux biscuits roses (trifle). Fruit-flavored brandies are a common way to end an evening.

With its Roman gate, Gothic cathedral, Champagne caves, and vibrant pedestrian zone, Reims feels both historic and youthful. And thanks to the TGV bullet train, it’s less than an hour’s ride from Paris.

Reims (pronounced like “rance”) has a turbulent history: This is where 25 French kings were crowned, where Champagne first bubbled, where WWI devastation met miraculous reconstruction during the Art Deco age, and where the Germans officially surrendered in 1945, bringing World War II to a close in Europe. The town’s sights give you an entertaining peek at the entire story.

You can see Reims’ essential sights in an easy day, either as a day trip from Paris or as a stop en route to or from Paris. Because some trains connect Charles de Gaulle Airport directly with Reims, this can be a handy first- or last-night stop. Take a morning train from Paris and explore the cathedral and city center before lunch, then spend your afternoon below ground, in a cool, chalky Champagne cellar or cave (pronounced “kahv”). You can be back at your Parisian hotel by dinner.

With a car, it’s worth taking a few hours to joyride the Champagne road that leaves from Reims’ back step (described later). Day-tripping drivers can arrange to pick up their car near either of the Reims train stations and visit the city before continuing on (storing bags at the rental office or in the car at the train station’s secure parking).

To best experience contemporary Reims, explore the busy shopping streets between the cathedral and the Reims-Centre train station. Rue de Vesle, Rue Condorcet, and Place Drouet d’Erlon are most interesting. Try to visit Reims on a Saturday, when the market erupts inside the dazzling Halles Boulingrin, and surrounding streets are lively. Sundays are très quiet and worth avoiding—handy buses don’t run, and so much is closed that it’s hard to get a feel for the town.

Reims’ hard-to-miss cathedral marks the city center and makes an easy orientation landmark. Most sights of interest are within a 15-minute walk from the Reims-Centre train station. City buses and taxis connect the harder-to-reach Champagne caves with the central train station and cathedral. The city is ambitiously renovating its downtown, converting large areas into pedestrian-friendly zones.

The main TI is one block away from the cathedral at 6 Rue Rockefeller (Easter-Sept Mon-Sat 9:00-19:00, Sun 10:00-18:00; Oct-Easter Mon-Sat 9:00-18:00, Sun 10:00-12:30 & 13:30-17:00; +33 3 26 77 45 00, www.reims-tourisme.com [URL inactive]). A smaller TI lies just outside the Reims-Centre train station (Mon-Sat 8:30-12:30 & 13:30-18:00, Sun 10:00-11:30 & 12:30-16:00, Oct-Easter closed Sun).

At either TI, pick up free maps of the town center, bus and tram routes, and the Champagne caves. Ask at the cathedral TI about renting a multimedia guide for visiting the cathedral and city.

Either TI can call a taxi (about €10) to get you to any Champagne house that you book. TIs also have information on minivan excursions into the vineyards and Champagne villages (see “Reims’ Champagne Caves” on here; reservations may be required).

Sightseeing Pass: The TI sells a €22 one-day Reims City Pass that serious sightseers will appreciate. It covers the Palais du Tau, Museum of the Surrender, Reims Cathedral tower tour, all public transportation, and the Reims City Tour by bus, and offers discounts on Champagne tours (20 percent off at Taittinger; see details on TI website).

By Train: From Paris’ Gare de l’Est station, take the direct TGV to the Reims-Centre station (12/day, 50 minutes). In Reims, the small TI is to your right as you exit; a taxi office is to your left (taxis wait in front of the station at busy times).

Trains also run directly from Charles de Gaulle Airport to the Champagne-Ardenne TGV station five miles away from Reims-Centre station (4/day, 45 minutes). Other TGV trains from Paris destined for Germany or Alsace also stop at the Champagne-Ardenne station. From there, take a local “milk-run” (TER) train to Reims-Centre (TER usually leaves 15 minutes after TGV arrival, 15 minutes to Reims-Centre station), or ride tram #B into the city center (3/hour, 20 minutes, direction: Neufchâtel; walk downhill from the station to find the tram stop; see “Getting Around Reims” for ticket information).

By Car: Day-trippers should follow Cathédrale signs, and park in metered spots on or near the cathedral or in the well-signed Parking Cathédrale structure. If you’ll be staying the night, take the Reims-Centre exit from the autoroute for most of my recommended hotels, and park in the Erlon parking garage—enter from Boulevard du Général Leclerc.

Department Store: Monoprix is inside the Espace Drouet d’Erlon shopping center (Mon-Sat 9:00-20:00, Sun until 13:00, basement level, 53 Place Drouet d’Erlon, follow FNAC signs).

Baggage Storage: Stash your bags a minute from the train station at the Ibis Reims Centre Hotel (turn left directly as you exit the station, small fee, 28 Boulevard Joffre, +33 3 26 40 03 24), or at a nearby shop by booking online at www.nannybag.com/en.

Laundry: You’ll find a launderette a 10-minute walk south of the cathedral (long hours daily, 49 Avenue Gambetta).

Bike Rental: Manu Loca Vélo delivers bikes within about 10 miles of Reims (reservations required, mobile +33 6 51 27 24 10, manulocavelo@hotmail.fr).

Taxi: Taxi offices are at the train station and at 40 Rue Carnot, next to the Opéra. Or you can call +33 3 26 03 03 00.

Car Rental: Single-day or longer car rental in Reims is usually reasonable even when booked late. Avis is just outside the central train station at 20 Rue Pingat (+33 3 26 47 10 08 or +33 8 20 61 17 05; use the Clairmarais exit from the station, turn right, and walk 200 yards); another office is in front of the Champagne-Ardenne TGV station (+33 3 61 58 82 71). Europcar is at 76 Boulevard Lundy (+33 9 77 40 32 61); Hertz is at 26 Boulevard Joffre (+33 3 26 47 98 78). Rental agencies are usually open Mon-Sat 8:00-12:00 & 14:00-18:00; most are closed Sun and some close early Sat afternoon.

City Tours: Reims City Tour offers a one-hour circuit of the city by minibus (€10-15, 3-5/day in summer, fewer in winter, recorded commentary). Purchase tickets from the main TI or online. Tours depart from behind the cathedral (www.reims-citytour.com).

Champagne Tours: See here.

By Bus or Tram: Reims has an integrated network of colorful buses, trams, and an electric shuttle bus (www.citura.fr, French only, but excellent maps). You can buy tickets from the bus or shuttle driver; for trams it’s better to use the ticket machines at any tram stop (€1.60/1 hour, €4.10/24 hours, €13/10 1-hour tickets that can be shared; coins only, no credit cards). Your ticket is valid for unlimited transfers between all buses and trams, even a round-trip on the same line. Each time you board, hold your ticket to the validation machine until you hear a beep.

Bus #11 runs from the train station to Porte de Mars, Halles Boulingrin, and the Mumm Champagne cellars, though the walk to all but Mumm is easy.

Two tram lines—#A and #B—connect Reims’ two train stations and travel on to a few stops in town (about every 10 minutes, fewer on Sun). To get from either station to the cathedral, main TI, and town center, take a tram to the Opéra stop or walk 10 minutes.

The handy bright-green CityBus electric shuttle makes a 30-minute loop from the Reims-Centre station to the cathedral, stopping at St. Timothée and St. Niçaise (close to Martel and Taittinger caves), Veuve Clicquot and Pommery cellars, then Place du Forum and Halles Boulingrin (near recommended restaurants) before returning to the station. Wave at the driver to get the shuttle to stop (Mon-Sat 9:00-19:00, no service Sun, free for up to 5 people with Erlon parking garage receipt).

BLITZ WALKING TOUR FOR TRAIN TRAVELERS

▲Carnegie Library (Bibliothèque Carnegie)

Covered Market Hall (Halles Boulingrin)

▲Museum of the Surrender (Musée de la Reddition)

Caves Southeast of the Cathedral

If you’re racing through Reims, here’s a quick walking plan that follows the order of its main sights. These highlights can be seen on foot in a three-hour sightseeing stroll from the train station (add another two hours to visit a cellar, and another hour each per museum visit). Pick up a town map from the TI just outside the train station before you begin.

If you plan to visit the Museum of the Surrender, check their hours locally first as it may close during lunch (you can start there and do this walk in reverse—especially fun on a Wed, Fri, or Sat morning, when the market at Halles Boulingrin is in full swing).

From the station (which retains its original 1860 facade), walk directly into the park out front. Find the statue of hometown boy Jean-Baptiste Colbert, the finance minister of Louis XIV back in the 17th century.

The park, or Grande Allée des Promenades, was originally a garden outside the city walls. In 1848, when it was clear that Reims didn’t need a protective wall, the fortifications were demolished to create a three-mile-long circular boulevard. Look at your town map to see the “left foot”-shaped outline left by the wall.

From Colbert, angle to the right, cross what was the wall, and walk along Place Drouet d’Erlon. This long, pedestrianized street-like square marks the commercial center of town. It’s Reims’ “little Champs-Elysées.” Stroll two long blocks up to the square’s centerpiece: a fountain and column crowned by a glistening gold-winged figure of Victory. (The original Victory, from 1906, was melted down by the Nazis—the current one is a recent replacement.) The fountain—with four voluptuous women—celebrates the four major rivers of this district.

While World War II left the city unscathed, World War I devastated Reims. It was the biggest city on France’s Western Front, and it was hammered. Sixty-five percent of Reims was destroyed by shelling, and in 1918 only 70 buildings remained undamaged. The area around you was entirely rebuilt in the 1920s. If it looks eclectic, that’s because the mayor at the time said to build any way you like—just build. Make a little spin tour to survey the facades.

All around you’ll see the stylized features—geometric reliefs, motifs in ironwork, rounded corners, and simple concrete elegance—of Art Deco. The only hints that this was once a medieval town are the narrow lots that struggle to accommodate today’s buildings. Continue along the square to check out the building at #15, which is fake half-timbered (in concrete), and the three Art Deco facades at #19-21. Where Place Drouet d’Erlon ends (at a small fountain), pop into the Waida Pâtisserie at #5 for a pure, typical Art Deco interior.

While at Waida, consider picking up a quiche and some pastries to enjoy on the cathedral square. They also sell biscuits roses de Reims—light, rose-colored egg-and-sugar cookies that have been made since 1756. They’re the locals’ favorite munchie to accompany a glass of Champagne—you’re supposed to dunk them, but I like them dry (many places that sell these treats offer free samples).

From here, cut over to the left (Rue Condorcet works), then take a right on Rue de Talleyrand; you can’t miss Reims Cathedral.

The cathedral museum (Palais du Tau) and Carnegie Library are next to the church. From the Cathédrale stop near the TI, you can catch the electric CityBus to the Taittinger and Martel Champagne caves (see “Reims’ Champagne Caves,” later), or continue your walk via Place du Forum (the former Roman forum) to Porte de Mars (the old Roman gate). Near Porte de Mars you can’t miss the restored 1927 Art Deco covered market hall (Halles Boulingrin). From here, the Museum of the Surrender is a short walk across the intersection, behind the train station. Just like that, you’ve seen the highlights of the city. Now it’s time for a nice glass of Champagne.

The cathedral of Reims is a glorious example of Gothic architecture, and one of Europe’s greatest churches. It celebrated its 800th birthday in 2011. Clovis, the first Christian king of the Franks, was baptized at a church on this site in AD 496, establishing France’s Christian roots, which still hold firm today. Since Clovis’ baptism, Reims Cathedral has served as the place for the coronation of 26 French kings, giving it a more important role in France’s political history than Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris. This cathedral is to France what Westminster Abbey is to England.

And there’s a lot more history here. A self-assured Joan of Arc led a less-assured Charles VII to be crowned here in 1429. Thanks to Joan, the French rallied around their new king to push the English out of France and finally end the Hundred Years’ War. During the French Revolution, the cathedral was converted to a temple of reason (as was Paris’ Notre-Dame). After the restoration of the monarchy, the cathedral hosted the crowning of Charles X in 1825—the last coronation here. During World War I about 300 shells hit the cathedral, damaging statues and windows and destroying the roof, but the structure survived. Then, during the 1920s, it was completely rebuilt, thanks in large part to financial support from John D. Rockefeller Jr.

Luckily, World War II spared the church, and since then it has come to symbolize reconciliation. A French plaque set in the pavement just in front recalls the 1962 Mass of Reconciliation between France and Germany. A German version of the marker was added in 2012, commemorating 50 years of friendship and celebrating the belief that another war today between these two nations would be unthinkable.

Cost and Hours: Free, daily 7:30-19:15, helpful information boards in English throughout the church (www.cathedrale-reims.com [URL inactive]). You can rent multimedia guides at the cathedral TI, but my self-guided tour below works well for most.

Getting There: The cathedral is a 15-minute walk from the Reims-Centre station. Follow sortie signs for Place de la Gare, then walk to the TI on the right and follow the map on here. You can also take the tram or catch the green electric CityBus from in front of the station (5-minute ride to the cathedral).

Cathedral Tower: An escorted one-hour tour climbs the 250 steps of the tower to explore the rooftop and get a close-up look at the Gallery of Kings statuary (€8, €11 combo-ticket with Palais du Tau; reserve tickets on cathedral website on day of your visit, get hours at TI or Palais du Tau, where you’ll pick up tickets and meet escort).

Cathedral Sound-and-Light Show (Rêve de Couleurs): For a memorable experience, join the crowd in front of the cathedral for a free, 25-minute sound-and-light show on most summer evenings. The colorful lights and booming sound take you through the ages, evoking the building’s design and construction, the original appearance of the statuary, the coronations that occurred here, the faith of the community, and—during the centennial of the Great War—the shelling it absorbed during World War I. Sit directly in front of the cathedral or settle more comfortably into a seat at a café with a clear view through the trees. The show generally starts when it’s dark—between 21:30 and 23:00 (TI has the schedule, nightly except Mon July-Aug, Wed-Sun only in June). Sometimes a second show commences 10 minutes after the first show ends.

Self-Guided Tour: Begin your visit by admiring the cathedral’s West Portal. It’s perhaps the best west portal anywhere. Built under the direction of four different architects, it is remarkable for its unity and harmony. The church was started in about 1211 and mostly finished just 60 years later. The 260-foot-tall towers were added in the 1400s; the spires intended to top them were never installed for lack of money.

Self-Guided Tour: Begin your visit by admiring the cathedral’s West Portal. It’s perhaps the best west portal anywhere. Built under the direction of four different architects, it is remarkable for its unity and harmony. The church was started in about 1211 and mostly finished just 60 years later. The 260-foot-tall towers were added in the 1400s; the spires intended to top them were never installed for lack of money.

Like the cathedrals in Paris and Chartres, this church is dedicated to “Our Lady” (Notre Dame). Statues depicting the crowning of the Virgin take center stage on the facade. For eight centuries Catholics have prayed to the Mother of God, kneeling here to ask her to intervene with God on their behalf. In 1429, Joan of Arc received messages here from Mary encouraging her to rally French troops against the English at the Siege of Orléans (a statue of Joan from 1896 is over your left shoulder as you face the church).

An ornate facade like this comes with a cohesive and carefully designed message. Study the carving. A good percentage of the statues are original and date from around 1250. There are three main doors, each with a theme carved into the limestone.

On the left is the Passion (the events leading up to and including the Crucifixion). Among the local saints shown below is the famous Smiling Angel, whose jovial expression has served the city well as its marketing icon. The central portal is dedicated to the Virgin Mary, featuring the Coronation of Mary with scenes from her life below. And on the right is the Last Judgment, with scenes from the apocalypse. Above the great rose window are reliefs of David (with his dog) and Goliath. Notice the fire damage, from 1914, around the rose window (fire melts limestone). Across the top is the Gallery of Kings, depicting 56 of France’s kings. They flank the country’s first Christian king, Clovis, who appears to be wearing a barrel—he’s actually kneeling prayerfully at a baptismal font. These anonymous statues, without egos, are unnamed kings whose spiritual mission is to lead their people to God.

Before going inside, step around to the right side and study the exoskeletal nature of the church’s structure. Braces on the outside—flying buttresses—soar up the sides of the church. These massive “beams” are critical to supporting the building, redirecting the weight of the roof outward (and into the ground), rather than downward on the supporting walls. With the support provided by the columns, arches, and buttresses, the walls—which no longer needed to be so solid and thick—became window holders.

The architects of Reims Cathedral were confident in their building practices. Gothic architects had learned by trial and error—many church roofs caved in as they tested their theories and strove to build ever higher. Work on Reims Cathedral began decades after the Notre-Dame cathedrals in Paris and Chartres, allowing architects to take advantage of what they’d learned from those magnificent earlier structures.

Contemplate the lives of the people in Reims who built this huge building in the 13th century. Construction on a scale like this required a wholesale community effort—all hands on deck. The builders of the Reims Cathedral gave it their all, in part because this was the church of France—where its kings were crowned. Most townsfolk who participated donated their money or their labor knowing that neither they, nor their children, would likely ever see it completed—such was their pride, dedication, and faith. Imagine the effort it took to raise the funds and manage the workforce. Master masons supervised, while the average Jean did much of the sweat work.

Now, step inside and stand at the back of the nearly 500-foot-long nave. The weight of the roof is supported by a few towering columns that seem to sprout crisscrossing pointed arches. This load-bearing skeleton of columns, arches, and buttresses allowed the church to grow higher. Sun pours through the stained glass, bathing visitors and worshippers in divine light.

Take a look at the wall of 52 statues stacked in rectangular blocks inside the door. (Cover the light from the door with this book to see better.) Imagine the 13th-century technology employed to carve each of these blocks in the nearby workshop and then install them so seamlessly here. These blocks continue the stories told by the statues on the outside.

Walk up the central aisle until you find a plaque in the floor marking the site of Clovis’ baptism in 496. Back then, a much smaller, early-Christian Roman church stood here. And back then you couldn’t enter a church until you were baptized. Baptisteries stood outside churches, like the one that welcomed Clovis into the Christian faith.

Walk ahead to the choir. The set of candlesticks and crucifix at the high altar were given to the church by Charles X on the occasion of his coronation in 1825. Look back at the west wall. The original windows were lost in World War I; these, rebuilt from photographs, date from the 1930s.

Walk into the south transept. The WWI-destroyed windows here were replaced in 1954 by the local Champagne makers. The windows’ scenes portray the tending of vines (left), the harvest (center), and the time-honored double-fermentation process (right). Notice, around the edges, the churches representing all the grape-producing villages in the area.

Looking high above at the ceiling, you’ll see evidence of bomb damage from 1917, when the roof took direct hits and collapsed. (The lighter bricks show the repair job from the 1920s.) The gray/white “grisaille” windows in this transept were installed in the 1970s. Many of the darker, more richly colored medieval glass windows were replaced by clear glass in the 18th and 19th centuries (when tastes called for more light).

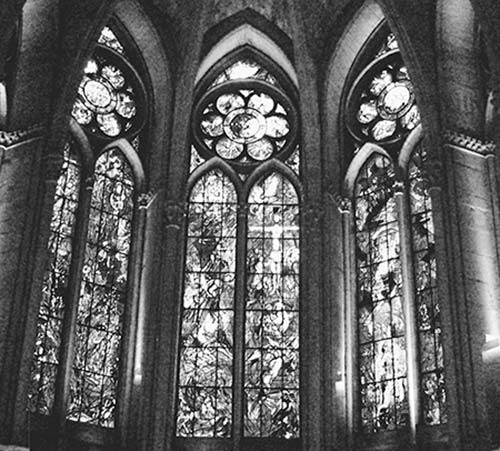

The apse (east end, behind the altar) holds a luminous set of Marc Chagall stained-glass windows from 1974. Chagall’s expressive style lends itself to stained glass, and he enjoyed opportunities to adorn great churches with his windows. The left window illustrates scenes from the Old Testament, with the Tree of Jesse (with Jesse himself sleeping at the bottom) reaching up to Mary with the Christ Child. In the central panels, the cohesion of the Old and New Testament scenes is emphasized by the ladder that connects one to the other. On the right, the Tree of Jesse—which is essentially a genealogical diagram of Christ’s lineage—is extended to symbolically include the royalty of France, thus affirming the divine power of the monarchs and stressing their responsibility to rule with wisdom and justice. Featured are Clovis (at the bottom, with his bishop); St. Louis IX (seen at the cathedral and then dispensing justice); Charles VII (on the right in green); and Joan of Arc, in blue, holding her sword (on the far right).

For the cathedral’s 800th anniversary, in 2011, six modern, abstract windows were installed on either side of the Chagall windows. Just to the left is a 1901 statue of Joan of Arc, her face carved from ivory.

From here, directly behind the high altar, enjoy the best view of the entire nave. Seen from this distance, the west wall is an ensemble seemingly made entirely of glass. Look at the confidence of the design. Even the corners outside the rose window were glass, made without stone. The architects pulled out all the stops in this triumph of Gothic.

This former Archbishop’s Palace, named after the Greek letter T (tau) for its shape, houses artifacts from the cathedral next door and a pile of royal goodies. You’ll look into the weathered eyes of original statues from the cathedral’s facade, and see precious tapestries, coronation jewels, and more.

Cost and Hours: €8, €11 combo-ticket includes cathedral tower tour (covered by Reims City Pass); open Tue-Sun 9:30-18:30, Sept-April Tue-Sun 9:30-12:30 & 14:00-17:30, closed Mon year-round. The €3 audioguide is overkill for most—follow my tour below and supplement it with the free English brochure, good bookshop, +33 3 26 47 81 79, www.palais-du-tau.fr.

Visiting the Palace: The collections are in two distinct parts—the royal chapel and treasury with jewels and artifacts, and the cathedral museum with statues and tapestries. Most of the exhibits are on the upper level.

On the ground floor (Room 1), you’ll start in the hall dedicated to the rebuilding of the cathedral after WWI bombings and the enlightened philanthropy of John D. Rockefeller Jr. When the roofs of Gothic churches burned, the lead that covered them melted and cascaded down like flowing rivers. Here, the gargoyles with once-molten lead spewing out of their storm-drain mouths make that much easier to envision.

Upstairs, the royal chapel (Room 5) was where the king would spend the night before his coronation, secluded in prayer. Inlaid in the floor are fleurs-de-lis, symbol of the French monarchy. At the altar are six candlesticks used at Napoleon’s wedding in 1810.

Flanking the entry to the chapel are treasury rooms (Rooms 6 and 7) filled with royal valuables. On the left are examples that survived the melt-it-down mania of the French Revolution. Imagine the fury of the revolutionaries, who would melt down precious crowns and chalices to satisfy their practical need for gold and silver. Very little survived that wasn’t buried away—these varied treasures were excavated from royal tombs in the 1920s (and survive in perfect condition). Don’t miss the ninth-century talisman worn by Charlemagne and the exquisite chalice used by French royalty in the 12th century.

Room 8 is filled with gold-plated silver regalia made for the coronation of Charles X in 1825. The new pieces were necessary because the historic regalia had been melted down.

In the next room (9) ponder the royal portraits and the 60-pound mantle of the divine king. Think of the dramatic swings in France’s history: A generation after you cut off a king’s head, you welcome a new king as if he were divine.

Turning right into Room 10, where the cathedral museum section begins, let your gaze soar high. An original 13th-century statue of Goliath measures a whopping 17.7 feet. In the next rooms, find cases with tiny statues with traces of original paint. Admire the amazing detail of the carving.

The highlight and grand finale (Room 15) is the original centerpiece of the cathedral’s west facade: the fire-damaged Coronation of Mary group, carved in the 12th century. In the same room, six figures from the Gallery of Kings stand as if guarding 16th-century tapestries. Originally hung around the choir in the center of the cathedral, the themes of these tapestries illustrating the Virgin’s life supported the prayers and preaching of the faithful.

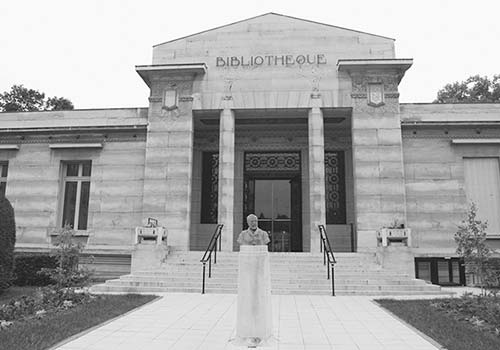

The legacy of the Carnegie Library network, funded generously by the 19th-century American millionaire Andrew Carnegie and his steel fortune (notice the American flag above the main entrance on the left), extends even to Reims. Carnegie believed knowledge could put an end to war, and he built several thousand such libraries around the world (he dedicated $200,000 for the one in Reims). Built in 1921 in the flurry of interwar reconstruction, this beautiful Art Deco building still houses the city’s public library. Considering that admission is free and it’s just behind the cathedral, it’s worth a quick look.

Visitors are welcome to poke around but are asked not to enter the reading room. In the onyx-laden entry hall, small marble mosaics celebrate different fields of knowledge, and a chandelier hangs down like the sleek dress of a circa-1920s flapper. Peek through the reading room door to admire the stained-glass windows of this temple of thought. The gorgeous wood-paneled card-catalogue room takes older visitors back to their childhoods. Go ahead, finger the laboriously created typewritten files, and imagine the technology available back in 1928, the year the library was inaugurated.

Cost and Hours: Free; Tue-Wed and Fri 10:00-13:00 & 14:00-19:00, Sat until 18:00, Thu 14:00-19:00 only, closed Sun-Mon; Place Carnegie, +33 3 26 77 81 41. The CityBus shuttle runs near the library.

Reims’ main square recalls the forum, or market, that marked the center of the ancient city. Legend has it that Reims was founded by Remus (brother of Romulus), and so the tribe that lived here came to be called “Remes.” This old town of 50,000 people was the capital of the Roman province of Gaullia-Belgica. From Place du Forum, you can climb down steps into the Cryptoportique, a first-century AD Roman gallery. About 10 feet below today’s street level, this cool retreat was once the cloister that defined a sacred temple zone in the middle of the Roman Forum (free, daily 14:00-18:00, closed Oct-May). This is also a pleasant place to dine al fresco on warm summer evenings (see “Eating in Reims,” later).

The only aboveground monument surviving from ancient Reims is this entry gate to the city (free, always open, at Place du Boulingrin). The Porte de Mars, built in the second century AD, was one of four principal entrances into the ancient Gallo-Roman town. Inspired by triumphal arches that Rome built to herald war victories, this one was constructed to celebrate the Pax Romana (the period of peace and stability after Rome had vanquished all its foes). Unlike most other structures here, the gate was undamaged in World War I, but it bears the marks of other eras, such as its integration into the medieval ramparts.

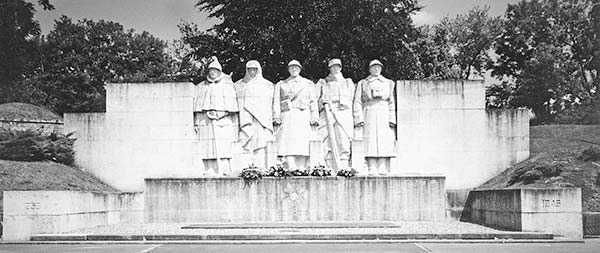

Near the Porte de Mars (on Place de la République—an easy walk from the Reims-Centre train station or take bus #11) stands a huge WWI memorial. Reims, the biggest city on the Western Front during the Great War, endured 1,051 days of shelling during those four years.

Built in 1927, this jewel of Art Deco architecture reopened in 2012 for the first time in 20 years after an estimated €31 million renovation. The vaulted roof consists of a mere 2.75 inches of reinforced concrete and rises 65 feet. Its splendid, bustling morning market spills over to include surrounding streets (open Sat 6:00-14:00, also Wed and Fri 7:00-13:00; tiny organic market Fri 16:00-20:00, closed other days, 50 Rue de Mars—an easy walk from the Reims-Centre train station or take bus #11).

Anyone interested in World War II will enjoy visiting the place where US General Dwight Eisenhower and the Allies received the unconditional surrender of all German forces on May 7, 1945. The news was announced the next day, turning May 8 into Victory in Europe (V-E) Day. There’s an extensive collection of artifacts, but the most thrilling sight is the war room (or Signing Room), where Allied operations were managed.

Start with the good 10-minute video in the theater on the main floor. Then climb upstairs to the museum and Signing Room. Imagine running the European Theater of Operation from here, as General Eisenhower did from February to May 1945 (after the Allies gained control of the airspace). The walls are covered with floor-to-ceiling maps showing troop positions, fuel supplies, where train lines were functioning, and so on. Progress was painstakingly marked and updated daily. The chairs around the table, with name tags in their original spots, show where the signatories sat.

Cost and Hours: €5, Wed-Mon 10:00-18:00 (may close at lunchtime—check hours locally), closed Tue, 12 Rue Franklin Roosevelt, +33 3 26 47 84 19, www.musees-reims.fr.

Getting There: It’s a 10-minute walk from the train station.

Reims, the capital of the Champagne region, offers many opportunities to visit its ▲▲ world-famous chalk Champagne cellars (caves). The oldest were dug by the Romans as they mined chalk and salt in the 1st century BC. Hundreds of years later, Champagne producers converted the caves—with their perfect and constant temperatures—into wine storage.

Which cave should you visit? Martel offers the most personal and best-value tour. Taittinger and Mumm have the most impressive cellars (Mumm is also close to the city center and offers one of the best tours in Reims). Veuve Clicquot is popular with Americans and fills up weeks in advance. Cazanove is closest to the train station and the cheapest, but you get what you pay for. Wherever you go, bring a sweater, even in summer, as the caves are cool and clammy.

How to Visit: All charge entry fees, most have several daily English tours, and most require a reservation (only Taittinger allows drop-in visits). Call, email, or visit the website for the schedule and to secure a spot on a tour. The TI can make reservations for the Mumm and Martel cellars, and they offer minivan excursions into the nearby vineyards. Cris-Event Champagne Tours gets rave reviews and can be booked directly (€85/person for half-day, €190/person all day, includes lunch, +33 3 26 53 03 06, www.cris-event.fr). France Bubble Tours is another good option (€180/person for all-day tour, +33 2 47 79 40 20, www.france-bubbles-tours.com).

Getting to the Caves: Mumm and Cazanove are both in the city and easy to reach on foot. Without a car, the others involve a long walk (30-40 minutes), a 15-minute ride on the CityBus (except on Sun), or a taxi ride (see “Caves Southeast of the Cathedral”). A taxi from either of Reims’ train stations to the farthest Champagne cave will cost about €10 each way. To return, ask the staff at the caves to call a taxi for you. The meter starts running once they are called, so count on €5 extra for the return trip.

Mumm (“moome”) is one of the easiest caves to visit, as it’s a short walk from the central train station. Reservations are essential, especially on weekends (book in advance online). Choose which tasting you want when getting your ticket (the cheapest Cordon Rouge tasting is fine for most, though you can pay more for the same tour with extra “guided” tastings). You’ll see a quick promotional video explaining the Champagne-making process, then follow a guided walk taking you through the industrial-size chalk cellars, where 25 million bottles are stored (Mumm is Champagne’s largest producer), and a museum of old Champagne-making tools and traditions. The tour ends with your tasting choice.

Cost and Hours: €23-45 depending on tasting level, includes a one-hour tour followed by tasting; tours generally offered daily 9:30-11:30 & 14:00-16:30 (34 Rue du Champ de Mars—go to the end of the courtyard and follow Visites des Caves signs; +33 3 26 49 59 70, www.mumm.com).

Getting There: It’s a 15-minute walk from the Reims-Centre train station or from the cathedral. From the station, turn left on Boulevard Joffre and walk to Place de la République; pass through the square, and continue along on Rue du Champ de Mars (to the left of the Europcar office). You can also take bus #11 from the station (direction: Béthany) to the Justice stop, turn right (south) onto Rue de la Justice, and then left onto Rue du Champ de Mars. To return to the station on bus #11, turn left from Mumm and walk a block down Rue du Champ de Mars to the bus shelter (direction: Apollinaire).

If you’re in a rush and not too concerned about quality, Cazanove is closest to the train station and has a cheap and basic tasting. (Martel’s tasting for same price is far superior; see “Martel,” later.) There are no chalk caves and only some Champagne is made on-site (€15, includes “tour” with 3 tastings; daily 10:00-13:00 & 14:00-19:00, 5-minute walk from the station up Boulevard Joffre to 8 Place de la République, +33 3 26 88 53 86, www.champagnedecazanove.com).

Taittinger and Martel, offering contrasting looks at two very different caves, are a few blocks apart, and can easily be combined in one visit. Veuve Clicquot Ponsardin is a bit farther out and pricey—but it has impressive cellars and that memorable name. It’s also a big draw for American travelers and must be booked well in advance.

Getting There: From the town center, it’s a 30-minute walk to Taittinger and Martel. Starting from behind the cathedral’s south transept, walk straight down Rue de l’Université, then Rue du Barbâtre. Veuve Clicquot is another 15 minutes farther on foot (see map on here). If that’s too far, there’s a handy taxi stand at 40 Rue Carnot, next to the Opéra (about €10).

To reach Taittinger and Martel by bus, take the small green CityBus from the train station or from the Cathédrale stop (near TI one block in front of the cathedral)—and ride 10 minutes to the St. Timothée stop (ask the driver to point you in the right direction). Use the same stop to return to the cathedral or station.

To reach Veuve Clicquot, take the CityBus from the train station or the Cathédrale stop (to the Droits de l’Homme stop, return stop is on opposite side of big roundabout on Boulevard Dieu Lumière, bus stop Cimetière du Sud, direction: Gare Centre).

One of the biggest, slickest, and most renowned of Reims’ caves, Taittinger (tay-tan-zhay) runs morning and afternoon tours in English through their vast and historic cellars (call for times, best to show up early or make an online reservation, about 25 people per tour). After seeing their 10-minute promo movie (hooray for Taittinger!), descend with your guide for 40 chilly minutes in a chalky underworld of caves, the deepest of which were dug by ancient Romans. You’ll tour part of the three miles of caves, see ruins of an abbey and a Roman chalk quarry, pass some of the three million bottles stored here, and learn all you need to know about the Champagne-making process from your well-informed guide. Popping corks signal that the tour’s done and the tasting’s begun.

Cost and Hours: €25-77 depending on tasting level, includes cellar tour, reserve ahead online; open Tue-Sun 9:30-17:30, closed Mon; 9 Place St. Niçaise, +33 3 26 85 84 33, www.taittinger.fr.

This small operation with less extensive caves offers a homey contrast to Taittinger’s big-business style, and it’s a great deal. Call to set up a visit and expect a small group that might be yours alone. Friendly Emmanuel runs the place with a relaxed manner. Only 20 percent of their product is exported, so you won’t find much of their Champagne in the US. A visit includes an informative 10-minute film, a tour of their small cellars (which are peppered with rusted old winemaking tools), and a tasting of three Champagnes in a casual living-room atmosphere.

Cost and Hours: €17, one-hour tour and tasting, daily 10:00-11:30 & 14:00-17:30, reservations not required but advised, TI can call ahead for you, 17 Rue des Créneaux, +33 3 26 82 70 67, www.champagnemartel.com.

Because it’s widely exported in the US, Veuve Clicquot is inundated with American travelers willing the pay the high price to visit their cellars. Reservations are required and fill up three weeks in advance, so book before your trip—it’s easy on their website (figure €30-40 for tour and tasting, vineyard visit also possible, Place des Droits de l’Homme, +33 3 26 89 53 90, www.veuve-clicquot.com [URL inactive]).

Drivers can joyride over the hills just south of Reims (the pretty Montagne de Reims area) and through the vineyards, experiencing the chalky soil and rolling landscape of vines that produce Champagne’s prestigious sparkling wines. This leisurely 50-mile loop drive takes about three hours, including stops.

There are thousands of small-scale producers of Champagne in these villages—unknown outside France and producing fine-quality Champagne without the high costs and flash associated with big brand-name houses in Reims and Epernay (figure about €15-30/bottle). These less famous producers harvest the grapes themselves and make wine only from their own grapes (identified as “récoltant manipulant” or just “RM” on bottles and elsewhere).

The Reims TI has maps of the Route de la Champagne and a Discovery Guide for the Marne region. Roads are well marked: Brown Route Touristique de la Champagne signs lead along much of our route and take you to some great viewpoints. The only rail-accessible destination along this route is Epernay.

It takes a little work to line up visits to wine producers in this area, and you must call ahead to tour a cellar rather than just taste, but this usually pays off with a more intimate, rewarding cultural experience. The Reims TI can book visits (or you can do it on their website), or check in with Les Vignerons Indepéndents de Champagne (Independent Winemakers of Champagne) for a list of producers and information on booking visits: +33 3 26 59 55 22, www.vignerons-independants-champagne.com.

If you’re doing this drive without reservations, it’s easier on a weekend, when more places are open and more likely to welcome drop-in tasters. If you plan to picnic, you’ll find all you need in the sweet little town of Aÿ. There’s also a bakery and a small grocery in Bouzy (unpredictable hours).

If you’re pressed for time, you can still sample the vineyard scenery by driving just 15 minutes south from Reims, or by working parts of this route into your drive to or from Reims (the best stop is Hautvillers).

• From Reims, take A-4 (direction: Châlons-en-Champagne), then soon exit south to Cormontreuil on D-9, following signs to Louvois (first tasting opportunity).

You’ll pass through the usual commercial fringe before popping out into lovely scenery just 15 minutes after leaving Reims. If you toured Mumm’s cellars, you’ll notice their hilltop property with a windmill well off in the distance (on the left) as you climb the Montagne de Reims, where the best grapes are grown.

Consider a stop at Guy de Chassey, where drop-ins are welcome to enjoy a tasting (assuming the place isn’t busy). Call ahead if you want to tour their property (Mon-Sat 10:00-12:00 & 14:00-17:00, closed Sun, closed Aug and mid-Dec-mid-March, on the roundabout as you enter town at 1 Place de la Demi-Lune, +33 3 26 57 04 45, www.champagne-guy-de-chassey.com).

• Take D-34 out of town. A little after leaving Louvois, look for Route de la Champagne signs leading left along a vineyard lane into the appropriately named village of Bouzy. Take the short detour off to the point de vue for a fine view over the village and vines.

There are 30 producers of Champagne in little Bouzy alone, some of whom are famous for their Bouzy Rouge (a still red wine made only from pinot noir grapes, and not made every year). Most places require reservations to visit, but drop-ins are welcome for the fun tasting at Champagne Herbert Beaufort. You’ll likely be served by a family member. Arrive at 10:30 or 15:30 for visits to their cellars (free tastings, Mon-Fri 9:30-11:30 & 14:00-17:30, Sat 9:30-11:30 & 14:30-17:00, Sun 10:00-12:00 in summer, closed Sun Oct-Easter, first domaine on your left coming from Louvois on D-34 at 32 Rue de Tours, +33 3 26 57 01 34, www.champagnebeaufort.fr).

• From Bouzy, leave the vineyards following D-19 to Tours-sur-Marne, then turn right onto D-1 and carefully track signs to Aÿ.

This lively little town (pronounced “eye”) boasts of producing 100 percent grand cru Champagne from all its vineyards. Detour into the pleasant town center, and park near Hôtel de Ville and Café du Midi. Within a few blocks you’ll find bakeries, charcuteries, cafés, and a good grocery store (which sells cold drinks).

• Back on D-1, drive into the next town—Dizy (what you get after too much Bouzy, Aÿ!)—and follow signs up the hill to Hautvillers. You’ll pass Moët et Chandon vineyards on your way.

If you have time for only one stop, make it Hautvillers (meaning “High Village”). This is the most attractive hamlet in the area, with strollable lanes, houses adorned with wrought-iron shop signs, and a seventh-century abbey church with the tombstone of the monk Dom Pérignon. Park near the Café Hautvillers, across from the little TI (+33 3 26 57 06 35, www.tourisme-hautvillers.com). From here it’s a nice walk to the town’s sights (all well-signed).

The abbey church is worth a wander (great WCs) for its wood-accented interior alone. According to the story, in about 1700, after much fiddling with double fermentation, it was here that Dom Pérignon stumbled onto the bubbly treat. On that happy day, he ran through the abbey, shouting, “Brothers, come quickly...I’m drinking stars!” Find his tombstone in front of the altar.

To taste your own stars, find Champagne G. Tribaut (300 yards from the café), and meet animated Valerie or her assistant, who love their work and the family’s product. Ask them about Ratafia, a local fortified wine served as an aperitif. You can linger over your glass of bubbly in the comfortable view reception room as you survey the sea of vineyards, but it’s best to call or email a day ahead to let them know you’ll be stopping by (may charge small fee for tasting, open Mon-Fri 9:00-12:00 & 14:00-18:00, Sat-Sun 10:00-17:30, closed Jan-Feb, +33 3 26 59 40 57, www.champagne-tribaut-hautvillers.com [URL inactive]).

Another option is Au 36, a slick wine shop/tasting room that represents many producers. The passionate staff will help you understand the differences among grape varieties (€10-15 tastings with 3 contrasting Champagnes, good prices for purchase, daily 10:30-18:00, a block from Café Hautvillers at 36 Rue Dom Pérignon, +33 2 26 51 58 37).

For a spectacular picnic spot (with tables and benches, but no WCs) and sweeping views over vineyards and the Marne River, drive to the abbey church and follow Rue de l’Eglise past it for three minutes. Get out of the car and wander among the vineyards. That picture-perfect village down below is Cumières.

• Exit the town downhill, toward the river to Cumières, then turn left on D-1 and follow signs home to Reims (about 20 minutes back on the speedy D-951). You could also pass through Cumières and drive two miles into Epernay, home to Moët et Chandon.

True connoisseurs can continue along the Route Touristique de Champagne south of Epernay toward Vertus, along the chardonnay grape-filled Côte des Blancs.

Champagne purists may want to visit Epernay, about 16 miles from Reims (and also well-connected to Paris—two daily local TER trains run through Epernay on the way to Reims). Epernay is most famously home to Moët et Chandon, which sits along Avenue de Champagne, the Rodeo Drive of grand Champagne houses.

Arrival in Epernay: Trains run frequently between Reims-Centre station and Epernay (12/day, 35 minutes). From the Epernay station, walk five minutes straight up Rue Gambetta to Place de la République, and take a left to find Avenue de Champagne. Moët et Chandon is at #20, and the TI is at #7 (TI open Mon-Sat 9:30-12:30 & 13:30-19:00, Sun 10:30-13:00 & 14:00-16:3, off-season until 17:30 and closed Sun, +33 3 26 53 33 00, www.ot-epernay.fr [URL inactive]).

Tasting in Epernay: The granddaddy of Champagne companies, Moët et Chandon offers 70- to 90-minute tours with pricey tasting possibilities (€25 “Traditional Visit” with one tasting, €47 for two tastes and longer tour, no reservation needed, kids 10-18 can join the tour for €10—but no tasting, under 10 free, daily 9:30-11:30 & 14:00-16:30, closed weekends off-season, closed Jan, 20 Avenue de Champagne, +33 3 26 51 20 20, www.moet.com).

To sip a variety of different Champagnes from smaller producers, stop by the wine bar C Comme Champagne (meaning “C like Champagne”). Start with a peek in the wine cellar, then snuggle into an armchair and order by the taste, glass, or bottle (Thu-Tue 10:00-20:00, Wed from 15:00, 8 Rue Gambetta, +33 3 26 32 09 55).

$$$ Hôtel Continental**** is a boutique hotel on lively Place d’Erlon with plush, quite modern rooms in every size, shape, and price (RS%, good family options; air-con, elevator, pay parking, 5-minute walk from central train station at 93 Place Drouet d’Erlon, +33 3 26 40 39 35, www.continental-hotel.fr, reservation@continental-hotel.fr).

$ Hôtel Kyriad Reims Centre*** is a fair three-star hotel with modern comforts (air-con, 29 Rue Buirette, +33 3 26 47 39 39, www.kyriad.com, reims.centre@kyriad.fr).

$ Best Western Hôtel Centre Reims*** delivers crisp and modern comfort at fair rates in surprisingly quiet rooms, despite being right on the lively square (family rooms, elevator, air-con, 75 Place Drouet d’Erlon, +33 3 26 47 39 03, www.hotel-centre-reims.fr, contact@hotel-centre-reims.fr).

Dining in Reims is as much about the area you eat in as the restaurant you choose. I’ve described areas to troll for dinner as well as a few specific restaurants. If you’re just looking for cheap picnic fixings, head to the grocery store at Monoprix (see “Helpful Hints,” earlier).

This bustling line of cafés and restaurants serves mostly cheap and so-so meals but has the city’s best people-watching and café action. Linger over a drink at one of the cafés on the square, then eat elsewhere. You’ll find exceptions to the forgettable offerings at the recommended $$$ Hôtel Continental’s restaurant, with quiet, inside-only dining, contemporary decor, and top service thanks to the helpful staff (good three-course menu, 93 Place Drouet d’Erlon, +33 3 26 40 63 83). Also consider across the square at $$$ Brasserie Excelsior, with an established clientele, a woody brasserie interior, and fine terrace tables outside (open daily, 96 Place Drouet d’Erlon, +33 3 26 91 40 50).

The quiet but popular Place du Forum attracts a young professional crowd at several bistros with good outdoor seating; it’s best for a more wine-focused, intimate meal with locals. Cathedral Square is ideal for picnicking while you admire the impressive church, eating outdoors under the towering cathedral facade. This spot is sensational after dark, when the floodlighting and sound-and-light show make the view a performance.

$$ Bistrot du Forum is an informal place with small wooden tables, a cool zinc bar, and good terrace seating. They serve hearty salads, bruschetta-like tartines, and burgers, as well as traditional meat and fish dishes. You’ll also find a good selection of wines (and Champagne, bien sûr) by the glass (long hours daily, 6 Place Forum, +33 3 26 47 56 58).

Just off the Place du Forum, on Rue Courmeaux, you’ll find $$ L’Epicerie au Bon Manger, a foodie refuge whose mantra is “In Good We Trust.” They have a handful of tables, stacks of organic local wines (by smaller, hard-to-find producers), smelly cheese, and charcuterie to go or to enjoy sitting down. It’s a handy place if you’re eating outside the rigid French lunch hours, because they serve nibbles all day (Tue-Sat 10:00-20:00, Thu-Fri until 22:00, closed Sun-Mon, 7 Rue Courmeaux, +33 3 26 03 45 29).

$$ Au Bureau, one of a handful of eateries on Cathedral Square, is worth it only if you grab a table outside and are OK with average café fare and indifferent service—but it’s a good place to linger over coffee (daily until late, at the cathedral at 9 Place du Cardinal Luçon, +33 3 26 35 84 83).

Near the Covered Market Hall (Halles Boulingrin): The pedestrian street Rue du Temple, along the south side of the market hall, is filled with cafés and brasseries—all with inviting outdoor terraces and a pleasant atmosphere. It’s especially lively on Saturday mornings during the weekly market. $$$ Brasserie du Boulingrin is a grand old Reims institution serving traditional French cuisine (including fresh oysters and a seafood platter) at reasonable prices (closed Sun; 10-minute walk from the Reims-Centre train station at 31 Rue de Mars, next to the Covered Market Hall, +33 3 26 40 96 22). Consider a glass of Champagne or wine in the cozy courtyard of the Le Clos wine bar at #25 (18:00 until late, closed Sun-Mon, live music some evenings, +33 3 26 07 74 69).

Near Opéra: $$$ Café du Palais is appreciated by older locals who don’t mind paying a premium to eat a meal or sip coffee wrapped in 1930s ambience. Reims’ most venerable café-bistro stands across from the Opéra and is good even just for a glass of wine (serves hot food during lunch hours and snacks the rest of the day, Tue-Sat 9:00-20:30, closed Sun-Mon, 14 Place Myron Herrick, +33 3 26 47 52 54).

Reims has two train stations—Reims-Centre (for the city center) and Champagne-Ardenne (a remote TGV station 5 miles from the center of Reims). Many TGV trains (particularly those heading east from Reims) require a connection at the Champagne-Ardenne station (with frequent local TER train or by tram from Reims Centre). For more on Reims’ train stations, see “Arrival in Reims” on here.

From Reims-Centre Station by Train to: Paris Gare de l’Est (12/day by TGV, 45 minutes, some with change at Champagne-Ardenne), Epernay (12/day, 35 minutes), Verdun (8/day, 1.5-3 hours, 1-2 changes, some via TGV with change at Champagne—Ardenne), Strasbourg (hourly by TGV, 2.5 hours, change at Champagne-Ardenne), Colmar (10/day by TGV, 4 hours, change at Champagne-Ardenne, most also change in Strasbourg).

While World War I was fought a hundred years ago, and there are no more survivors to tell its story, the WWI sights and memorials scattered around Europe do their best to keep the devastation from fading from memory.

Perhaps the most powerful WWI sightseeing experience a traveler can have is at the battlefields of Verdun, where, in 1916, roughly 300,000 lives were lost in what is called the Battle of 300 Days and Nights.

Today, the lunar landscape left by WWI battles is buried under thick forests—all new growth. But there are plenty of rusty remnants of the battle and memorials to the carnage left to be experienced.

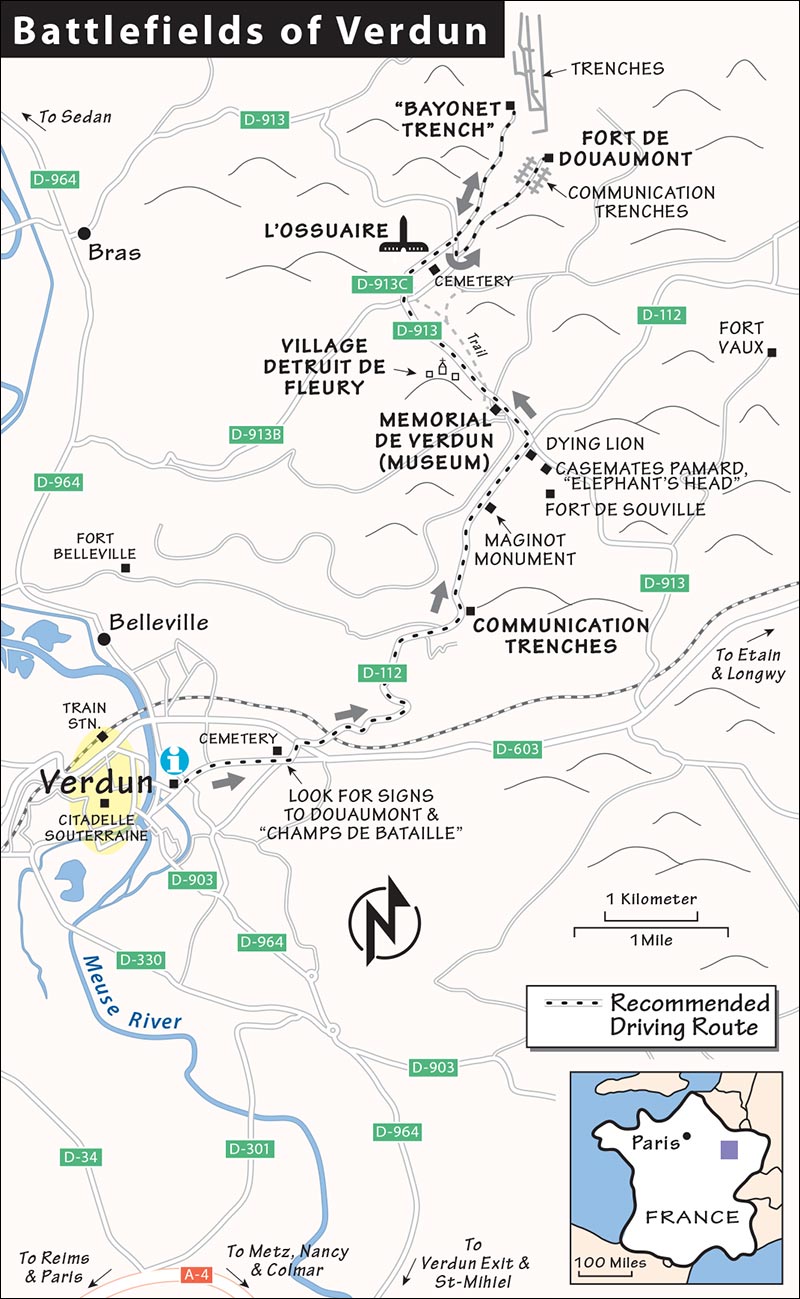

A string of battlefields lines an eight-mile stretch of road outside the town of Verdun. From here (with a tour, rental car, shuttle bus, or taxi) you can ride through the eerie moguls left by the incessant shelling, pause at melted-sugar-cube forts, ponder plaques marking spots where towns once existed, and visit a vast cemetery. In as little as three hours you can see the most important sights and appreciate the horrific scale of the battles.

Verdun’s TI is east of Verdun’s city center (just across the river—cross at Pont Chaussée, on Place de la Nation; generally Mon-Sat 9:00-12:30 & 14:00-18:30, shorter Sun hours off-season; +33 3 29 86 14 18, en.tourisme-verdun.com). Ask for the free Pass Lorraine, which is good for discounts at some sights in the region. The pleasant park nearby provides a good picnic setting.

By Train: Verdun is served by two train stations: the Meuse TGV station (18 miles from Verdun) and the Verdun station (within walking distance of town).

TGV trains from Paris’ Gare de l’Est and destinations from the east serve the Meuse TGV station. The high-speed TGV service puts Verdun within 1.5 hours of Paris and 2.5 hours of Strasbourg. A 30-minute shuttle bus connects the Meuse TGV station with Verdun’s main station (free with ticket to Verdun or a rail pass, leaves shortly after TGV train arrives).

Verdun’s main train station is 15 minutes by foot from the TI. To reach the town center and TI, exit the station, cross the parking lot and the roundabout, and keep straight down Avenue Garibaldi, then follow Centre-Ville signs on Rue St. Paul. Turn left on the first traffic-free street in the old center (Rue Chaussée) and cross the river to the TI. Shuttles back to the Meuse TGV station depart from in front of a glassy building 75 yards to the right when facing Verdun’s main station.

By Car: Drivers can bypass the town center and head straight for the TI or the battlefields. To find the TI, follow signs to Centre-Ville, then Office de Tourisme. To reach the battlefields, follow signs reading Verdun Centre-Ville, then signs toward Longwy, then find signs to Douaumont and Champs de Bataille (battlefields) on D-112, then D-913. The sights covered here fall in a line along this drive (just follow signs to Fort de Douaumont and Ossuaire). The map in this book is adequate for this drive.

While the Battle of Verdun took place in the hills outside town, the town of Verdun itself is worth a stroll—except on Sundays and Mondays, when most shops and businesses are closed. It’s a handy base for exploring the battlefield sights.

Verdun’s strategic location has left it with a hard-fought history. Locals call it “the most decorated town in France;” the number of war memorials would suggest they’re right. It’s a monochrome place, with bullet holes still pocking its stony buildings. And it’s small, with only 16,000 people—4,000 fewer than at the start of World War I. Most of the action lies along the Meuse River on the broad esplanade of Quai de Londres, where you’ll find a commotion of recreation boats mostly from the Low Countries and Germany (enjoying a system of former industrial canals) and scads of cafés, restaurants, and locals.

The town’s mighty 14th-century gate squats on the river (near the TI), looking warily east. The city’s state-of-the-art (in the 17th century) fortifications still seem poised to repel German armies. Just across the river, a thicker wall—built in 1871 in anticipation of an attack—supports a mammoth monument to the French victims of German invaders in both world wars.

Verdun’s old town is crowned by its Victory Monument, high above the river, with a cascading fountain connecting it to the pedestrian heart of town. The fountain’s centerpiece, a towering warrior, plants his sword in the ground in a declaration of peace. He’s flanked by twin cannons—made by the French for the Russians but ultimately used by the Germans against the French at Verdun. While the monument originally honored French and Allied troops, today it honors Germans as well. Now that a century has passed, the German flag flies next to French and European Union flags. The varied sights of the Verdun battlefields have risen above national bias, memorializing all victims of that senseless war, and celebrating peace.

Verdun has a special place in the hearts of the French, as nearly every soldier in World War I was cycled in and out of this killing field. In 1916 Verdun was the departure point for soldiers heading to the battlefields (as it is today for visitors). The Citadelle Souterraine was the site where French soldiers assembled and had their last good bed, meal, and shower before heading into the shelling zone. The citadel, with 2.5 miles of tunnels cut into a rock, was a teeming military city. How big? Its bakery cranked out 23,000 rations of bread every day. Today, it tries to give the public a glimpse at life on the front with a 30-minute ride on a Disneyesque wagon that comes with a recorded narration (€9, open daily 9:00-18:30). While interesting, if your time if limited, it’s better spent at other battlefield sights.

Eating and Sleeping in Verdun: A good selection of eateries lines the river on Quai de Londres. $ Bolzon Charcuterie on the pedestrian-only Rue Chaussée (#21, closed Sun) has good salads, quiche, and dishes to go. Eating options are limited at the battlefields—consider assembling a picnic in Verdun or at an autoroute minimart.

Verdun makes an inexpensive and handy overnight stop. The comfortable $ Hotel de Montaulbain*** is in the heart of the old town (4 Rue de la Vieille Prison, mobile +33 6 13 56 47 08, www.hoteldemontaulbain.fr, contact@hoteldemontaulbain.fr).

High-speed TGV trains serve the Verdun area from the Meuse TGV station, 30 minutes south of Verdun. Regular but slower trains and buses also run to Verdun’s central station. For TGV connections listed next, allow an additional 30 minutes to ride a shuttle bus from Verdun’s train station (included with ticket to Verdun or rail pass).

From Verdun by Train to: Paris Gare de l’Est (5/day direct via TGV, 1.5 hours; 4/day by regional train, 3.5 hours with transfer), Strasbourg (10/day, 2-5 hours, 1-2 transfers, faster trips by TGV possible), Colmar (10/day, 4-6 hours, 2-3 changes, trips by TGV), Reims-Centre (8/day, 1.5-3 hours, 1-2 changes; about half are by TGV and require a change at Reims Champagne-Ardenne).

Verdun’s battlefields are littered with monuments and ruined forts. For most travelers, a half-day is enough. We’ll concentrate on the three most important sights, the Verdun Memorial Museum, Douaumont Ossuary, and Fort Douaumont.

Information: Sights are adequately described in English (some provide audioguides). The TI and all sights sell books in English. At the TI, the simple but adequate booklet Verdun du Ciel provides helpful details (€5). Serious students will read ahead, and there’s no shortage of literature about the Battle of Verdun. Alistair Horne’s The Price of Glory sorts through the complex issues and offers perspectives from both sides of the conflict.

Eating: There are only two places to eat along this route. One is the rooftop café at Verdun Memorial Museum; the other is a café-restaurant near the Ossuary. Consider picking up supplies in Verdun and using the picnic area near the trenches at Fort Souville (see later).

The most interesting battlefield sights lie along an easy eight-mile stretch of road from the town of Verdun. The Verdun TI offers a very limited number of bus tours to the battlefields, but most are in French only. Most visitors will find renting a car, taking a taxi, or hiring a guide a far better option to lace these sights together.

By Car: Cheap car rental is available a block from the Verdun train station at AS Location (about €55/day with 110 km/60 miles included—that’s plenty, Mon-Fri 8:30-12:00 & 14:00-18:00, sometimes open Sat, closed Sun, 22 Rue Louis Maury, +33 3 29 86 58 58, www.location-vehicule-verdun55.fr). I’ve included basic route tips in my “Verdun Battlefield Drive,” later.

By Taxi: Taxi rates are about €30/hour. For roughly €40 round-trip, taxis can drop a carload at one sight and pick up at another (walk between sights). Ask to be dropped at “Fort de Douaumont” and picked up three hours later at the “Ossuaire de Douaumont” or five hours later at the “Mémorial de Verdun”; figure about 30 minutes of level walking between each of these sights). Taxis normally meet trains at the station; otherwise they park at the TI (see http://taxi-verdun.com, mobile +33 6 81 95 26 98).

By Private Guide: These local guides will considerably enrich your understanding of events at Verdun: Ingrid Ferrand (mobile +33 6 79 45 30 98, or +33 7 71 66 79 74, www.verdun-fuehrungen-macht-ingrid.com), Florence Lamousse (+33 3 29 85 21 83, , + 33 3 29 85 21 83 Mobile +33 6 89 22 10 43, www.lorrainetouristique.com), and Guillaume Moizan (mobile +33 7 70 06 66 61, guillaume.moizan.guide@gmail.com). Guillaume can take you in his car while Ingrid and Florence will join you in your rental car (allow €200/half-day, €350/day).

After the annexation of Alsace and Lorraine following the German victory in the Franco-Prussian War in 1871, Verdun found itself just 25 miles from the German border. This was too close for comfort for the French, who invested mightily in new fortifications ringing Verdun, hoping to discourage German thoughts of invasion. It was as if the French knew they’d be seeing German soldiers again before too long.

The plan failed. World War I erupted in August 1914, and after a lengthy stalemate, in 1916 the Germans elected to strike a powerful knockout punch at the heart of the French defense, to demoralize them and force a quick surrender. They chose Verdun as their target. By defeating the best of the French defenses, the Germans would cripple the French military and morale. The French chose to fight to the bitter end. Three hundred days of nonstop trench warfare ensued. France eventually prevailed, but at a terrible cost. This is as far as Germany ever got.

World War I introduced modern technology to the age-old business of war. Tanks, chemical weapons, monstrous cannons, rapid communication, and airplanes made their debut, conspiring to kill nearly 10 million people in just four years. This senseless war started with little provocation, raged on with few decisive battles, and ended with nothing resolved, a situation that sowed the seeds of World War II.

The Battle of Verdun was fought from February through December of 1916. This was one chapter in a horrific battle of attrition in which Germany and France decided to wage a fierce fight, knowing they would suffer unprecedented losses. Each side calculated that the other would drop first.

During the “Hell of Verdun” (hell for troops and hell for locals), Germany and France dropped 60 million artillery shells on each other. An estimated 95 percent of the deaths at Verdun were from artillery shrapnel. Shells were fired from as far away as nine miles, with poor accuracy. Death by friendly fire was commonplace.

Today, soft, forested lands hide the memories of World War I’s longest battle. Millions of live munitions are still scattered in vast cordoned-off areas. It’s not unusual for French farmers or hikers to be injured by until-now unexploded mines. It’s difficult to imagine today’s lush terrain as it was just a few generations ago...a gray, treeless, crater-filled landscape, smothered in mud and littered with shattered weaponry and body parts as far as the eye could see. But as you visit, it’s good to try.

All the sights described here are along (or just off) the same road. As Fort Douaumont is the most distant stop, follow signs for Douaumont. With the simple map in this book, you should have no problem. Along the way (within easy view of the road), you’ll see the sights described next. Your major stops: the museum, the huge cemetery/ossuary, and the pulverized fort.

• Leave Verdun on D-603 (direction: Longwy), and then take a left on D-112. Departing Verdun, on the first corner you see six field cannons—German guns made by Skoda that were state of the art in 1914. (Renault, Peugeot, Skoda—seemingly all industry was geared toward machines of destruction.) Behind those guns are 5,000 gravestones—most dated 1916. Following signs to Champs de Bataille, from here you enter a lumpy forest that has grown over what was smooth farmland.

At this parking and picnic area, find a curving trench and craters, similar to those that mark so much of the land here. A few communication trenches like this remain—they protected reinforcements and supplies being shuttled to the front, and sheltered the wounded being brought back. But the actual trenches defining the front in this area were destroyed during the battles or have since been filled in. The nearby Fort Souville is not safe to visit.

André Maginot served as France’s minister of war in the 1920s and ’30s, when the line of fortifications that later came to bear his name was built. The Maginot Line, which stretches from Belgium to Switzerland, was a series of underground forts and tunnels built after World War I in anticipation of World War II and another German attack. The Germans solved the problem presented by this formidable line of French defense by going around it through Belgium. The monument (showing a wounded Maginot being carried to safety) is here because André Maginot’s family was from this region, and he was wounded near Verdun.

At the intersection with D-913, a statue of a dying lion marks the place where, after giving it their all, the German forces were stopped. The German military commanders had hoped for a quick victory at Verdun so troops could be sent to fight the British in the Somme offensive. The war was dragging on, hunger was setting in among the German citizenry, and the German leadership feared a revolt. They needed a boost—but the offensive failed. This was the site of massive artillery barrages: Imagine no trees here, only a brown lunar-like terrain with countless shell holes 20 feet deep. A short detour (turn right on D-913 at the intersection) leads to a small sight signed Casemates Pamard, which is an armored machine gun nest nicknamed “Elephant’s Head” for the way the 1917 structure looks. (Access was only by tunnel from the nearby Fort Souville.)

• Return to the intersection, and continue straight ahead on D-913 (following signs to Ossuaire and Douaumont). Along the way you’ll pass the...

This museum delivers gripping exhibits on the 300 days of the Battle of Verdun, with lots of information in English. Allow a minimum of one hour to visit.

Cost and Hours: €12, discount with free Pass Lorraine—get at Verdun TI, daily 9:30-19:00, until 17:00 in winter, closed Jan; last entry one hour before closing; rooftop snack bar, +33 3 29 88 19 16, http://memorial-verdun.fr.

Visiting the Museum: The ground floor sets the scene with videos and exhibits that draw you into the battle. Start 10 steps past the turnstile at a small screen for a breathtaking five-minute review of “why WWI.” The museum is rich in artifacts and pairs both German and French exhibits. Displays help you imagine the experiences of men on the front line. You’ll see soldiers’ personal effects, uniforms, guns, trucks, and more. A battlefield replica lies below you, visible through the glass floor, complete with mud, shells, trenches, and WWI military equipment. You’ll learn about shrapnel, medical help in the trenches, and leaps in technology (from X-ray machines to machine guns shooting through airplane propeller blades). It was the end of horses and the start of ergonomic helmets. Sitting under a wall of faces, page through letters to loved ones sent from the trenches.

The upper floor continues with exhibits providing a broader context for the Battle of Verdun and World War I, from trench art to the role of women in World War I to propaganda. You can’t help but see how, before 1914, propaganda, nationalism, and isolation from other cultures (lack of travel) was a tragically explosive mix. Your visit finishes on the top floor with a terrace overlooking the actual battlefields.

From this museum, it’s a chilling 10-minute walk through the wooded yet bomb-pitted terrain to the destroyed village of Fleury, and a 20-minute walk on a trail to the cemetery at the base of the ossuary (trail starts across the road from the museum).

Thirty villages caught in the hell of Verdun were destroyed. Nine—like Fleury—were never rebuilt. Though gone, these villages (signposted as Villages Détruites) have not been forgotten: Each has a ceremonial mayor who represents the villages and works on preserving their memory.

Photos at the roadside pullout show Fleury before and after its destruction. Stroll through the cratered former townscape. The rebuilt church stands where the village church once did. Plaques locate the butcher, the baker, and so on. There’s also a memorial to two French officers who were executed by the French military because, by leaving the battlefield briefly to take a wounded soldier to safety, they disobeyed the order to “stand your ground until the last drop of blood.” Ponder the land around you. Not one square meter was left flat or unbombed.

• Drive on, following signs to the tall, missile-like building surrounded by a sea of small white crosses.

This is the tomb of countless unknown French and German soldiers who perished in the muddy trenches of Verdun. In the years after the war, a local bishop wandered through the fields of bones—the bones of an estimated 100,000 French soldiers and even more German soldiers. Concluding there needed to be a respectful final resting place, he began the project in 1920. It was finished in 1932. The unusual artillery shell-shaped tower and cross design of this building symbolizes war...and peace (imagine a sword plunged into the ground up to its hilt). Over time, fewer visitors come as pilgrims and more as tourists. Yet even someone who’s given little thought to the human cost of this battle of attrition will be deeply moved by this somber place.

Cost and Hours: Free entry, €6 for film and tower; Mon-Fri 9:00-18:00, Sat-Sun 10:00-18:00; shorter hours off-season, closed Jan; +33 3 29 84 54 81, www.verdun-douaumont.com [URL inactive].

Eating: The nearby $$ Café Abri des Pèlerins is the only place to eat among all these Verdun monuments (open daily, just beyond the Ossuary on the road to Douaumont, 1 Place Monseigneur Ginisty, +33 3 29 85 50 58).

Visiting the Ossuary: Park behind the theater/shop/tower. Look through the low windows in the back of the building at the bones of countless unidentified soldiers. From there, steps lead down to the shop and theater where you can see the excellent 20-minute film (shows on the half-hour; English speakers get headphones) and hike 200 steps up the tower (skippable). Appropriate attire is required, and men are asked to remove their hats.

The Mémorial Ossuaire is a humbling, moving tribute to the soldiers who believed the propaganda that this “Great War” would be the war to end all wars. The building has 22 sections with 46 granite graves, each holding remains from different sectors of the battlefields. Those who donated to the construction (in the 1920s) got a plaque for their loved one: the soldier’s name, rank, regiment, and dates of birth and death. In the chapel, stained-glass windows (circa 1920) honor priests, nurses, stretcher bearers, and mothers—all of whom contributed and suffered.

Outside, in front, walk through the cemetery and reflect on a war that ruined an entire generation, leaving more than 70 percent of all French soldiers dead, wounded, or missing. Rows of 16,000 Christian crosses and Muslim headstones (the latter gathered together and oriented toward Mecca), all with red roses, decorate the cemetery.

Just beyond the main cemetery you’ll find memorials to the Muslim and Jewish victims of Verdun. The Muslim memorial (built in 2006, across the street from the cemetery) recalls the 600,000 “colonial soldiers” (most of whom came from North Africa) who fought for France. These men, often thrown into the most suicidal missions, were considered instrumental in France’s ultimate victory at Verdun (a fact overlooked by anti-immigration, right-wing politicians in France today).

French Jews also fought and died in great numbers. The Jewish memorial (which you’ll pass as you drive out of the ossuary) survived World War II. That’s because the Nazi governor of this part of France, who had fought at Verdun and respected soldiers of any faith, covered it up.

• Leaving the ossuary parking lot, follow signs to the...

There is a legend that an entire company of French troops was buried in their trench by an artillery bombardment—leaving only their bayonets sticking above the ground to mark their standing graves. The memorial to this “bayonet trench” is a few hundred yards beyond the ossuary. The bulky concrete monument, donated by the US and free to enter (notice the inscription reading “Leurs frères d’Amérique,” meaning “Brothers from America”) opened in 1920, and was the first such monument at Verdun.

In fact, most of the Third Company of the 137th Infantry Regiment was likely wiped out here because they had no artillery support and died in battle—still tragic, just not quite as vivid as the myth. The notion of the bayonet trench could have come from the German habit of making “gun graves”—burying dead French soldiers with their guns sticking up so that their bodies could be found later and given a proper burial. Walking around this monument provides a thought-provoking opportunity to wander into the silent and crater-filled second-growth forest that now blankets the battlefields of Verdun.