The Five Points, 1828. This engraving from Valentine’s Manual (1861) depicts a profusion of classes, men and women, mixing in the streets. Although densely crowded and the poorest section of New York, the Five Points offered immigrants opportunities to establish a foothold in the city.

2

Shaking Off Constraints

A series of dramatic changes swept through New York City beginning in 1791 that changed the character of Jewish communal life, ultimately destroying the synagogue community of colonial times. Following the American Revolution came upheavals associated with Jeffersonian democracy that broadened the electorate and disrupted long-established patterns of deference. Economic innovation accompanied these political and religious experiments, fostering rapid expansion of the city’s population through immigration. This urban transformation made New York the nation’s largest metropolis. Its pluralism and diversity promoted significant alterations in the fabric of Jewish life that transformed Judaism into a distinctively urban religion. Concomitantly an industrial and commercial revolution facilitated new modes of work, housing, culture, religion, and politics. As civil conflict loomed, New York Jews bore few resemblances to the small, tightly knit and contentious community that had faced the revolt against British colonialism in 1776. Instead, democratic modes of Jewish communal life established patterns for a pluralistic urban American Judaism.

New York’s Jews joined the rest of the growing seaport community in one of the greatest contests in American political history: the battle over the legacy of the American Revolution. With the new nation deeply divided over the meaning of 1776, passionate political debates erupted. The Hamiltonians, subsequently the Federalist Party, sought a strong central government. They passed legislation creating a potent national bank, encouraged growth of manufacturing, including factory production, and staunchly supported Britain while fiercely opposing the French Revolution. Federalist ideology championed deference rather than egalitarianism, contending that people with less wealth ought to allow men with standing to guide the helm of nation, state, and city. Jeffersonians responded by forming the nation’s first political party, ancestor of today’s Democratic Party. Supporters of an agriculturally based society with a weak central and stronger state governments, they disliked financial speculation and regarded banks with fear and suspicion. They preferred that factories remain in England. Many initially opposed the Constitution. They supported the French Revolution and saw Britain as a foe of American independence. Advocates of political egalitarianism, they argued that a shoemaker could make as wise a choice regarding government policies as a learned attorney.1

Jews entered this political fray. In the tumultuous 1790s, while Jews aligned with both parties, most joined the Jeffersonians. However, the Hamiltonian version of republicanism that stressed deference and tradition found a home in Shearith Israel even as the egalitarian Jeffersonian strain was winning at the polls. As the city fathers attempted to establish order within a republican framework by laying out the rectangular street grid that was to define Manhattan Island, so, too, prominent Jewish leaders of Shearith Israel tried to inaugurate an ordered republican structure. They sought through constitution writing to remake their synagogue in the image of American republicanism.2

This first constitution tried to navigate opposing tendencies in New York political culture and to wed synagogue traditions with republican ideals. Its preamble echoed the initial lines of the Bill of Rights. But even as its bylaws opened membership to Jewish males who were at least twenty-one years old, they rejected indentured or hired servants and those who were intermarried. A further clause forbade any Jew who violated “religious laws by eating trefa, breaking the Sabbath, or any other sacred day” from being called to the Torah or running for congregational office. Yet this new compact allowed all members to vote for members of the board, gave three members the right to call a synagogue meeting, and directed arbitration to end divisive internal controversies.3

Shearith Israel remained the only synagogue in New York throughout the first thirty-five years of the early republic, but it no longer served as the cornerstone of Jewish life. Efforts to create a republican congregation failed to keep pace with the city’s growing Jewish population. Membership could not compete with other choices for fellowship, such as the Masonic Order or the Mechanics Society. However, on the High Holidays, nonmembers purchased seats and filled the synagogue. For many Jews, the synagogue assumed relevance for only part of their lives: primarily life-cycle ceremonies and the High Holidays. Thus began practices that became increasingly common throughout the United States.4

Shearith Israel struggled as a result. It endured repeated financial crises. Its Mill Street building gradually deteriorated. But it adamantly resisted all proposed reforms, rejecting a request for a choir, the right not to wear a prayer shawl, and any innovations in worship. This increasing rigidity rested on a new constitution that contained neither a bill of rights nor a statement proclaiming the right to enact compacts. It named only a single governing body, the Board of Trustees, with the parnas as president. The constitution stressed order and decorum, sustained by substantial fines. The Board of Trustees exercised tight control over hazan, shochet, and shamash, disbursed charity, and supervised the school. Though the hazan was a respected religious leader, the board governed. The trustees expected obedience.5

Jeffersonian influences battered Shearith Israel. The right to challenge authority, a key Jeffersonian tenet, sparked controversies. Intrigues among synagogue leadership and bitterly contested elections revealed how members shunned deference to oust traditional leadership. Generational tension and friction between Ashkenazi and Sephardi members contributed to these conflicts. Most significantly, Jeffersonianism spurred a revolt of Ashkenazi members that produced a second synagogue. Jefferson had affirmed that a people under a government that denied them “the inalienable rights of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness” possessed the right “to alter or abolish it, and to institute new government.” This spirit fostered the birth of B’nai Jeshurun in 1824.6

From the colonial period until the beginning of the nineteenth century, most Jews, like most New Yorkers, lived and worked in the area south of City Hall. But gradually more prominent Jews moved farther north, west of Broadway, to “quiet, tree-shaded blocks.” From there, New York’s wealthier families could still walk to their businesses and places of worship. Poorer Jews from England and central Europe also settled to the north, albeit east of Broadway. But while Protestants could choose among an array of churches, many reflecting class, denominational, and ethnic differences, all Jewish New Yorkers, regardless of wealth, headed to Shearith Israel, the city’s only synagogue, on Mill Street since the eighteenth century. Contemporary observers blamed the breakup of Shearith Israel on the growing geographic spread of the Jewish population. The city’s geography began to shape Jewish life, even as Jewish life shaped the geography of New York. But other forces were also at work.7

An Ashkenazi faction organized, seeking to implement a form of equality among Jewish men as well as greater religious observance than was the norm at Shearith Israel. While they pledged loyalty to Shearith Israel, they emphasized strict performance of Jewish law and attendance at services. More surprising, they established rotation in office, with an executive committee of five elected members to govern for three-month terms followed by a new committee. Believing in transparency, they opened committee meetings to the public and adopted a majority rule for accepting new members. The group promised to distribute honors democratically rather than in accordance with wealth. They intended to foster Ashkenazi identity and to increase religious observance by establishing egalitarian governance and democratic procedures in Jewish ritual practice.8

When Shearith Israel’s Board of Trustees refused to sanction a separate faction within the synagogue, the dissidents seceded. Explaining their decision to establish a new congregation, they wrote to the board a list of their grievances. First, being “educated in the German and Polish minhog,” they found it “difficult” to practice Sephardic ritual. Second, despite the still-small Jewish population in New York and sparse synagogue attendance, a growing Jewish community made it impossible for Shearith Israel to handle all Jewish congregants, “particularly on Holidays.” Third, the distance “of the shool” from their homes made it hard to attend services. The secessionists did not “capriciously withdraw” from this “ancient and respectable congregation.” Rather, echoing the Declaration of Independence, they declared it “nature’s necessity.” In closing, they invoked a shared identity “as Brethren of one great family.” As part of a Jewish community larger than any one synagogue, the new congregation, B’nai Jeshurun, trusted that their endeavor would “be recognized.”9

Shearith Israel’s board considered the letter, postponed action, and never responded. However, it soon recognized the new congregation. Shearith Israel loaned B’nai Jeshurun four Torah scrolls for the dedication of its synagogue in a remodeled First Coloured Presbyterian Church in the very heart of New York’s immigrant working-class neighborhood. Each congregation offered prayers for the welfare of both sets of trustees. Prominent members of Shearith Israel had signed the secessionists’ letter.10 It was time to let their fellow Jews go. The growing city could encompass more congregations.

This division of B’nai Jeshurun and Shearith Israel marked a turning point in New York Jewish communal life. Shearith Israel was New York’s first synagogue, but B’nai Jeshurun was the first of many new synagogues. Bolstered by increasing numbers of immigrants, congregations split and split again as egalitarian republicanism and rampant congregationalism blossomed in the city. B’nai Jeshurun represented a younger generation with fewer men of wealth and prestige, but it rapidly became one of the city’s largest synagogues, inaugurating new patterns of growth and expansion.11

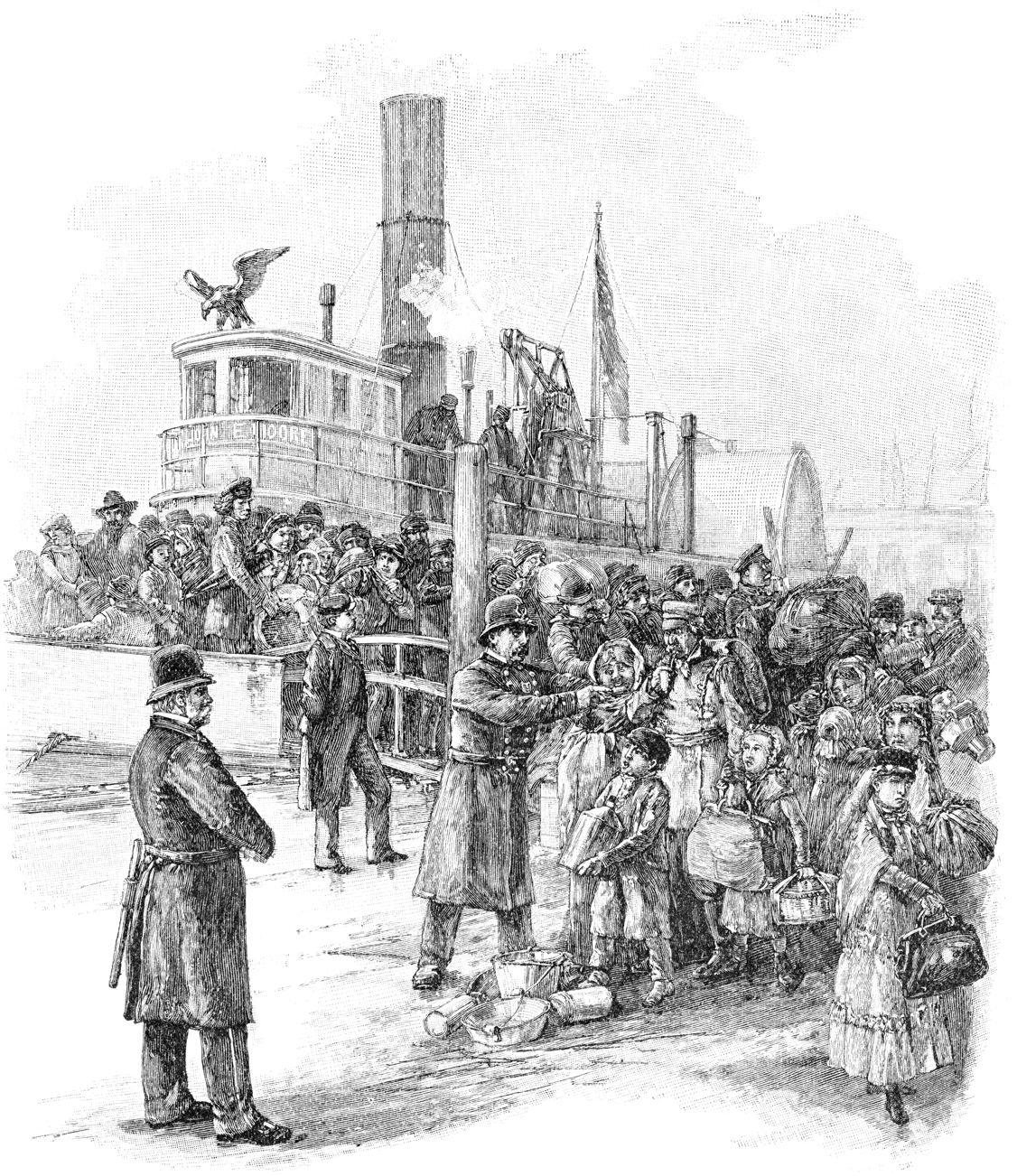

Prior to the Civil War, 150,000 Jews arrived in the United States as part of the central European migration, which included eastern European Jews from Russia and Poland who came by way of the German states. While many traveled on to midwestern cities like Chicago, Cleveland, Cincinnati, and St. Louis, thousands remained in New York. As central Europe transitioned from a society of estates, in which Jews served as middlemen between peasants and nobles, to an industrial society, many Jews faced dismal economic prospects. The slightly better off moved to larger cities in search of work; the poor migrated to the United States. Immigration not only took Jews from small towns to the metropolis but also transported them from a premodern society to a rapidly modernizing urban center. Letters home and newspaper articles heralded economic opportunities, accelerating migration and creating a chain guiding Jews. Jewish immigrants thus joined a great migration streaming out of various regions of central Europe.12

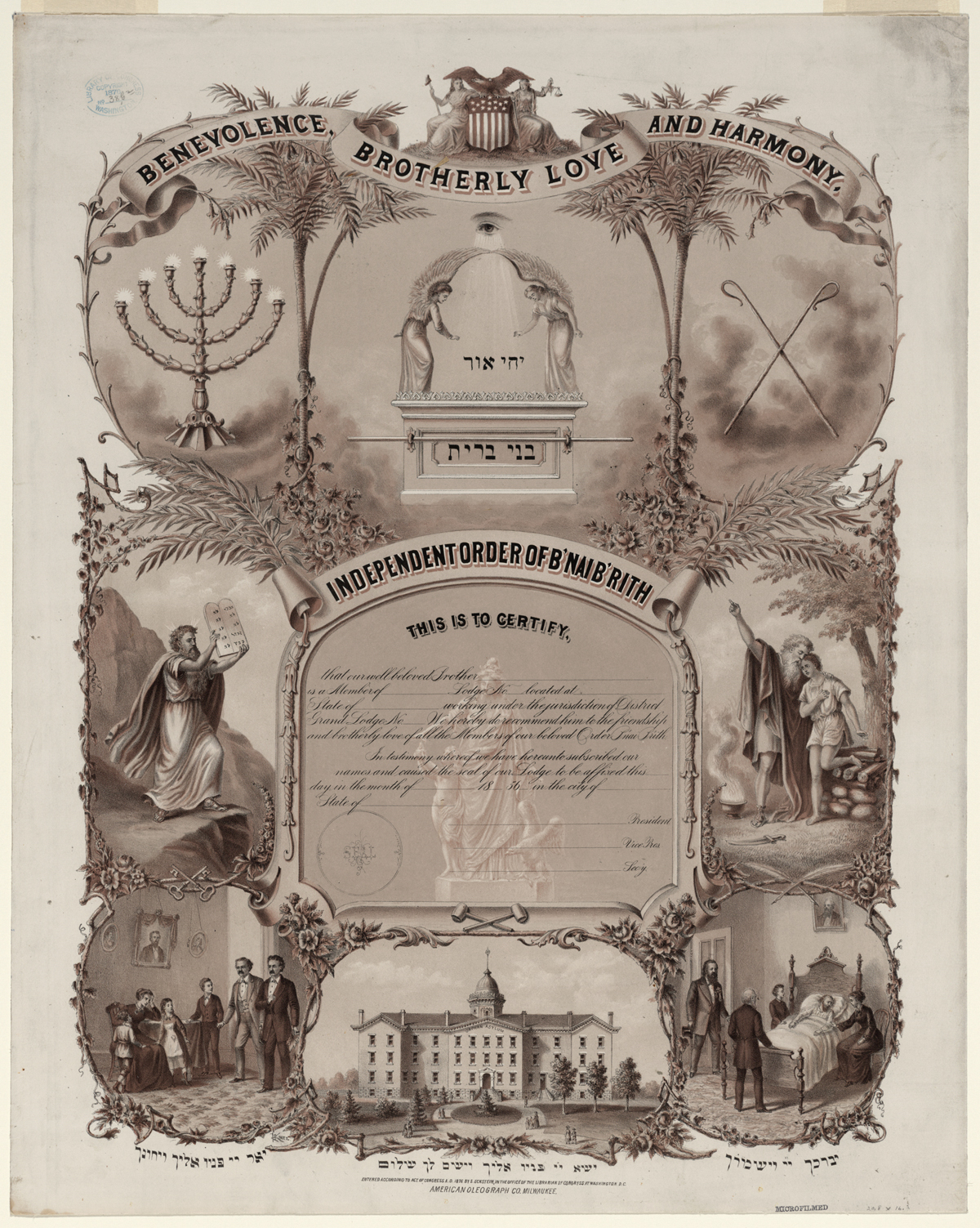

B’nai B’rith certificate, 1876. Jewish immigrant men in New York City established the Independent Order of B’nai B’rith, the Jewish fraternal society, in 1843. Initially designed to succor German-speaking immigrants, it grew rapidly, and many lodges switched to English before the Civil War. This certificate portrays the order’s charitable activities as well as its motto of “benevolence, brotherly love, and harmony.” Courtesy of the Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

Immigration changed New York’s Jews. By the mid-1840s, a quarter of the American Jewish population lived in the city. By 1859, New York’s Jewish population numbered near forty thousand (5 percent of the city’s general population), half of them central European Jews. They came from lands intermittently hostile to Jews, restricting access to professions, trades, real estate, and even marriage. Whether they left Prussia, Bavaria, or Bohemia, young immigrant Jews shared common characteristics: lack of formal education, little money, no spouse, and hardly any knowledge of English.13

Alternative Identities

October 1843. The Jewish cycle of High Holidays, culminating with celebration of the harvest festival of Sukkot, had just ended, and the regulars had gathered at Sinsheimer’s Café in the German Kleindeutschland (Little Germany) neighborhood of Manhattan for beer, conversation, and fellowship. While they were looking forward to the New Year that had just begun, their frustrations with, as they put it, “the deplorable condition of Jews, in this, our adopted country,” rankled. The congregations weren’t doing anything; they were too busy fighting over issues of ritual and liturgy. The new literary club that Henry Jones had joined hoping it would mediate between the congregations had succumbed and joined the fray. A born organizer, Jones, a serious, dark-haired, and bespectacled young man with a prominent nose and cleft chin framed by a fringe of beard, desperately wanted to foster a spirit of cooperation among New York Jews. He and several of the regulars had joined the Masons or Odd Fellows lodge, but a recent incident excluding Jews from a lodge irritated them. They needed something different.14

Seeking to rise above New York Jews’ internecine wrangling, the Sinsheimer regulars decided to create an alternative to both religious congregations and secular lodges: a secular Jewish fraternal society. They named their invention B’nai B’rith (Sons of the Covenant). This fraternity combined traditions of Judaism and Freemasonry and replaced the synagogue with the lodge room. Incorporating special handshakes and passwords, B’nai B’rith spoke to central European Jewish immigrants, offering a form of sociability that men once had enjoyed in synagogue. As the fraternal organization spread to many American cities, Jews found fellowship in its lodges and security in its insurance policies. B’nai B’rith members also strove to support “science and art,” to help “the poor and needy,” to come “to the rescue of victims of persecution,” and to bridge gaps between immigrant standing and citizenship. In short, they laid out for themselves basic demands of Jewish communal responsibility couched in universal language. Within less than a decade, New York enrolled seven hundred members, with more lodges opening each year. Before the century ended, New York Jews had exported their innovative form of Jewish secular fraternity across the ocean to Europe and the Middle East. Other Jewish fraternal orders followed, at times rivaling B’nai B’rith in numbers.15

As B’nai B’rith grew, it devoted itself to helping immigrants integrate into American society. Here, indeed, was a modern form of Jewish brotherhood, true “sons of the covenant,” whose fellowship knew no national boundaries, unconstrained by struggles over religious ritual. Responding to a Baltimore lodge’s request to admit non-Jews, the New York chapters replied that the order is “adapted … solely for Israelites.” Members organized the Maimonides Library “to provide instruction for the masses.” The library held eight hundred books available for loan for a dollar-a-year membership fee. B’nai B’rith lodges acted as adult literary societies guided by German liberal intellectual ideas. Lodges sponsored cultural evenings. On the eve of the Civil War, as immigrants prospered, lodges switched from German to English and dropped many secret rituals.16

Freedom from constraints of the “synagogue community” unleashed enormous creativity among New York Jews. They initiated new forms of Jewish communal organization that responded to opportunities and demands of urban living and remade Jewish life in the city. As the Jewish population diversified through immigration from central and eastern Europe, a more pronounced upper class and a growing working class emerged, products of urban growth. This combination spurred establishment of independent charitable organizations, including the city’s first Jewish hospital, as well as a wide array of social welfare, cultural, and communal groups.17 Though Jews composed less than 5 percent of New York’s population in the pre–Civil War decades, they supported almost as many organizations as non-Jewish ethnic and religious groups did. Organizational diversity—and competition—came to characterize New York’s Jews.

Synagogues multiplied but struggled to keep pace with Jewish institutional innovation. New immigrants from towns throughout central and eastern Europe sought familiarity in worship among their fellows as well as greater stringency in observance of Jewish law. Leaving towns that often restricted their freedom to marry and start a family, individual Jewish men found American democracy and freedom intoxicating. They aspired to leadership positions within congregations and willingly experimented by creating new organizations. No single institution could contain these variations. Neither could one congregation accommodate all would-be leaders, who, over a thirty-year period, established twenty-seven congregations. When Jews did go to synagogue, they went to pray and to socialize.18

Isaac Mayer Wise, the leader of Reform Judaism in America, reminisced that in 1846, when he first disembarked as a young man in New York, most poor Jews were ignorant of Jewish learning, while the better off “kept aloof from Hebrew society” and “despaired of the future.” Yet neither abandoned Judaism. Their “psychological and emotional needs” kept them “within the fold.” Immigrant Jews needed each other in a foreign land. Common ties of ethnicity, language, and culture endured, while deeply ingrained traditions, practices, and commonalities encouraged many native-born Jews to remain loyal to family and faith. But if the synagogue, despite its strong presence in New York, would not or could not fully satisfy desires for connections, where would these yearnings find an outlet?19

New York Jews spent most of their time outside synagogues—in tenements, on the streets, in workshops, and in the marketplace. They interacted with non-Jewish New Yorkers on a daily basis, forming relationships that influenced synagogue life and encouraged new patterns of Jewish association. Synagogue-goers adapted what they learned from New York politics, business, and society to introduce such new trends within the synagogue as elected officers. Synagogue leaders also decided to hire Jewish ministers able to represent the congregation in ecumenical gatherings and to deliver English-language sermons. The arrival of these first rabbis in the 1840s challenged previous patterns of lay leadership.

But daily life in New York also inspired formation of alternative forms of Jewish community—newspapers, social clubs, libraries, hospitals, lectures, and charities. Thus, the story of New York synagogues and their various divisions, while telling, is not the story of Jewish New York. Rather, the story of the urban origins of American Jewish life flourished in the markets, tailor shops, saloons, and butcher stores where Jews formed an ethnic economy and forged neighborhood networks. These more informal connections shaped new forms of associational life.

Jewish creativity also found outlets in the arts. The Italian Opera Company under Max Maretzek briefly exceeded even dancing in popularity. Born in Moravia, Maretzek came to New York after time in London as a conductor. He formed his own company, supported by fellow Jews who relished his productions of European operas. Other Jews tried their hand at theater, building playhouses and offering single-price tickets in a democratic move. On occasion, the local Jewish press boasted of Jewish contributions to the city’s culture. Yet such praise could be double-edged, with Jews accused of controlling New York’s cultural offerings and lowering their quality.20

As audience members, New York Jews evidenced diverse tastes in theater. They could be found in the dress circle of the City Theater and at Barnum’s Museum, where they watched plays that were “more intensely effective representations of real life” than elsewhere in the city. They also patronized the German National Theater as well as Fellow’s Minstrels, an entertainment parodying blacks, with whites wearing blackface and imitating black dialects. Participation in the arts offered the middling and newly affluent Jewish community opportunities to mix with Christians on equal terms, promising social acceptance in a broader urban public community.21

The literary society, an alternative fraternal outlet, attracted ambitious young Jewish men. Literary societies exemplified attempts to encourage fraternization by German-speaking Jewish immigrants, joined by non-German newcomers and native-born Jews seeking greater refinement. They aimed to integrate better into American society and discuss critical contemporary issues. Typical debates, for example, concerned whether “a woman ought to move in the same sphere as men” or whether fashion benefited humanity. Political issues, such as comparisons between Russian serfdom and American slavery, also animated discussion. Jewish, secular, optimistic, and ambitious, literary societies enrolled low numbers since most New York Jews focused on getting an economic foothold in the new country. Yet their ambitious intellectual agendas reflected energies and enthusiasms nurtured in the growing metropolis.22

As Jews achieved economic security, they embraced ever more lavish festive occasions. They attended dinners sponsored by literary and benevolent societies, enjoying music and dancing. In 1861, Meyer S. Isaacs, the twenty-one-year-old son of the editor of the Jewish Messenger, founded the Purim Association to raise funds for worthy causes. Its annual Purim Ball quickly became the social event of the year, celebrated with elaborate gaiety, despite the ongoing Civil War. Demand for invitations was intense; nobody of means wanted to be left off the list. More and more tickets were printed, as upward of three thousand fashionable Jews attended. Perhaps most sumptuous, the 1863 ball featured the Seventh Regiment band, with sixty-five musicians playing varied dance numbers. Remarkable elaborate costumes rarely referenced either Queen Esther or Mordecai, the holiday’s heroes. Adopting Christians’ New Year’s Day tradition, Jews opened their homes on Purim for visits. The Purim Ball marked the end of “ball season,” a season that encompassed synagogue and benevolent-society affairs and exclusive social gatherings, as well as public lectures and concerts.23

German influence on New York Jewish organizational practices spurred a secularization that extended to Sabbath observance. An exasperated editorialist complained that the average Jewish New Yorker desired to keep the Sabbath but felt that America’s “climate” created “something in the air that opposes his intention.” This pattern persisted. Fifty years later, a staunch crusader for Sabbath observance claimed that immigrants seeking freedom and economic opportunities “seemed to think there was something in the American atmosphere which made the religious loyalty of their native lands, and especially the olden observance of the Sabbath, impossible.”24

Indeed, something in New York’s “climate” did make regular Sabbath observance difficult, if not impossible. Sabbath practices differentiated not only Jew from Christian but also Catholic from Protestant and, significantly, German from Anglo. New Yorkers debated the Sabbath, how it should be observed, and whether it should be observed at all. German Christian immigrants contributed to this debate over appropriate behavior on the American Sunday. Even those who attended church regularly considered “secular activities” part of their Sunday routine, but these elicited criticism from native-born white Protestants. While some wished to reserve Sunday for rest and churchgoing, other definitions of Sunday behavior included attendance at a library, voluntary association, or lecture hall. Many immigrants championed a “Continental Sabbath,” which encompassed leisure and amusement. Theaters, dance halls, and saloons beckoned city dwellers but irked those who favored a government-protected Sunday as a day of church attendance and quiet contemplation. German immigrants organized to protect their right to spend their day off work as they pleased, appealing to American separation of church and state and individual liberties to fight Sunday blue laws.25

Jews, too, joined these debates. Sermons and publications noted that Jews shirked their religious responsibilities. Jewish communal leaders denounced Sabbath desecration but also argued over Christian worship patterns. Some claimed that Jews’ ability to open their stores on Sunday actually illustrated “American freedom, a striking instance of independence and equality.” Others rejected that argument. On a practical and personal level, New York Jews grappled with whether to work on Saturday, simultaneously the Jewish day of rest and an important commercial day. Jewish networks of peddling and business failed to insulate Jewish peddlers and businesspeople from the pull of the city’s commercial demands and the lure of its economic opportunities.26

Landing immigrants at Castle Garden, New York City. Engraving from Harper’s Monthly Magazine, June 1884. New York became a city of immigrants prior to the Civil War, with most arriving at Castle Garden at the southern tip of Manhattan. Immigrants transformed New York into the nation’s largest metropolis. Around 150,000 Jews, many of them from central Europe, figured among the immigrants coming to America in these years, and thousands remained in the city.

The growing presence of secular Jews in an increasingly immigrant city complicated what it meant to be Jewish. No longer was Jewishness defined by religious practice and congregational membership. Yet both Christians and Jews assumed that these nonobservant New Yorkers remained Jews. Their irreligious behavior challenged the boundaries of the city’s burgeoning and diversifying Jewish community and transformed characteristics of Jewish identity. On the one hand, in the formation of B’nai B’rith, the founding of Jews’ Hospital, and the inception of ninety-three different societies ranging from small burial societies to the Hebrew and German benevolent societies, Jews determined to bond with each other, often by nationality. On the other hand, Jewish families welcomed the public school, the institution that offered the quickest mode of acceptance for immigrant children into the greater community. Similarly, in Jews’ immersion in the arts, as in business, they chose to join Christian New Yorkers without distinction, to sit side by side at the Astor Opera House, the Academy of Music, and the Broadway theaters. Jewish identity and Jewish integration remained challenging and elusive as Jewish life increasingly became more complex, diverse, and urbanized, no longer centered on the synagogue. Instead, Jewishness acquired secular urban dimensions rooted in common experiences of immigration, occupational choices, and residence.

Immigrant Urbanism

The American Revolution had unleashed New Yorkers’ entrepreneurial expectations and generated remarkable urban growth. No city could match New York’s merchants, artisans, or manufacturers. Jews freely ventured into all arenas of the marketplace. Whether it was Asher Myers crafting bells for City Hall, Harmon Hendricks constructing a copper-rolling mill, or Sampson Simson launching clipper ships, Jews exploited the new opportunities. But even as an open market widened horizons of economic enterprise for aspiring artisans, merchants, and manufacturers, it increased economic stratification: by 1800, 20 percent owned 80 percent of the city’s wealth, while the bottom half owned less than 5 percent. This inequality grew even greater over the century.27 These changes were mirrored among New York Jews.

Soon after the Revolution, New York became the nation’s financial center. Four Jewish businessmen joined together with twenty other New Yorkers to found the New York Stock Exchange in 1793. The city’s merchants cornered the cotton trade, became expert at speculation and insurance, and launched ambitious economic adventures. With the opening of the Erie Canal, New York began its journey to become a world-class metropolis. The entry point for immigrants, the city’s port also served as the entrée for a majority of the nation’s imports as well as a site for transatlantic shipping of many exports from the West.28

Housing the New York Stock Exchange and the Gold Exchange, New York flourished as the American center of market speculation. Its banks provided investment capital for the West and South. The California gold rush brought the city both capital in newly minted gold and an outlet for its manufactories supplying western speculators. New York maintained close ties to the South: its bankers accepted slave property as collateral; its brokers hawked southern railroad and state bonds; its wholesalers sold southerners household goods; its traders and shipowners monopolized the sale of cotton.29

New York became the axis of the nation’s communication network. Telegraphy permitted almost instantaneous news of business and current events. A new invention, the rotary press, allowed an 80 percent drop in the price of a newspaper. Dailies and weeklies bloomed, enticing both elite and working classes with news, politics, sports, court trials, theater, investigative exposés, and gossip about the rich and famous. The weeklies included two English-language newspapers aimed at Jews: the independent Asmonean, edited by the English immigrant Robert Lyon, and the Orthodox Jewish Messenger, edited by Samuel Isaacs, the rabbi of Congregation Shaaray Tefilah.30

Before mass immigration from central Europe began in the 1840s, New York’s Jewish population most commonly fell within the middle or lower middle classes. Relatively few Jews entered the professions. However, as early as the 1790s, the first American-born Jewish physician graduated medical school at Columbia College. He pioneered in what became a common Jewish profession in New York. Most Jews worked as merchants, auctioneers, and brokers; smaller numbers labored in crafts. The expansion of printing in the city enticed Jewish artisans to enter the field. Yet even with a booming economy, poverty, disability, mental illness, and crime also existed among the city’s Jews, albeit in unknown proportions. New York’s wealthy Jews did not keep pace with this changing city; they no longer possessed the economic standing of earlier years. But Jews continued to own slaves as commonly as their non-Jewish peers did, until slavery was abolished in New York State in 1827.31

A major engine of social and economic transformation came with thousands of immigrants who crowded into New York in the thirty years before the Civil War. Pushed out by a potato famine in 1845 that spread from Ireland to the southern and western German states, the failure of the German Revolution of 1848, and widespread unemployment in Britain, an average of 157,000 emigrants arrived annually at Castle Garden at the tip of Manhattan. Approximately one of every five or six remained in the city, where they were joined by thousands of native-born Americans who left their farms or workshops to try their luck in the metropolis. By 1855, immigrants, mostly from Ireland and Germany, made up over half the city’s population. Two of every three adults in Manhattan were born abroad. New York’s urban revolution transformed it into an immigrant city, an identity that endured for over a century.32

Most newcomers considered life in New York better than in Europe, with more meat and nicer furniture, but they remained one bad recession away from the pawnshop. Many Germans lived in tenements in Kleindeutschland in lower Manhattan. A mere twenty-five feet wide and only seventy feet deep, of three to five stories, a tenement housed twenty-four two-bedroom apartments, each with only a single window for families and their boarders. Usually over 150 tenants crowded into a single tenement.33

In the era’s robust economy, at least a quarter of immigrant Jews attained middle-class standing by the 1850s, joining native-born Jews as merchants, wholesalers, retailers, skilled craftspeople, and professionals. Some did even better. During the Panic of 1857, a harrowing recession caused by the overextension of banks and a fall in the price of wheat, the Asmonean, hoping to persuade wealthy Jews to help those without work, published the names of fifty leading Jewish firms, averaging 278 employees each. Most were in textiles, a few in importing and dry goods. Many of the men heading these companies had connections in the South and West, including Joseph Seligman, whose family firm made a fortune supplying the California gold rush, and Levi Strauss, who achieved legendary success outfitting miners in California, while his purchasing office and manufacturing operations remained with his older brothers in New York. This wealth, immigrant and nonimmigrant, provided resources to build Jews’ Hospital and the Hebrew Orphan Asylum, to patronize the arts, and eventually to construct elaborate synagogues.34

Urbanization transformed the world of Jewish women as well as men. Unmarried women—whether widows or daughters—often worked as peddlers, washerwomen, domestics, and tailors. In the Five Points immigrant neighborhood just north of City Hall, almost half of employed women worked in the needle trades and a quarter as domestic servants. Some seamstresses labored in workshops; many sewed in their apartments. Irrespective of other employment and marital status, most women kept house. The majority of households had between three and six children. Whether through wage work or housework, shared occupations and responsibilities of the Five Points Jews created informal but vital neighborhood networks.35

Except for several women who achieved notoriety as feminists, few New York Jewish women participated in the women’s rights movement. However, many heard of the Seneca Falls convention of 1848 and its manifesto demanding equality. The Asmonean even printed a parody of the proclamation that it was time for the women to “break off the chains which Fashion has thrown among them.” Judging from newspaper columns, most Jewish men rejected women’s equality, echoing nineteenth-century middle-class norms that women belonged neither in the marketplace nor in the public square but rather in the home, at the center of domestic life. Men did support secular education for girls as well as boys, but if pages of advertisements for pianos are any evidence, religious training and participation remained peripheral to women’s lives. By contrast, attendance at concerts, dramas, and operas suggested that middle-class Jewish women embraced the arts and rarely frequented the synagogue gallery.36

New York’s urban expansion produced distinctive residential neighborhoods that reflected variations in class, occupations, and points of origin. Residential stratification changed the character of daily interactions. Within each neighborhood, different modes of life took root, increasing social distance between Jews. While the more established Shearith Israel leaders living west of Broadway and just north of City Hall might have used oil lamps, coal stoves, and iceboxes, those east of Broadway inhabited dilapidated and hastily subdivided wooden homes and depended on candles, oil lamps, and found wood. Much of the native-born Jewish population moved to the Lower West Side, north of Canal Street (Shearith Israel built a new synagogue on Crosby Street in 1834 in recognition of this residential clustering), while immigrant Jews settled among Catholic and Lutheran German immigrants. The bulk of their synagogues clustered in a section of Kleindeutschland on the East Side. Thus, class divisions separated Jewish congregations even as they stratified Protestant churches.37

Jewish immigrants usually spent their first years in Five Points, the city’s immigrant neighborhood, where familial and communal ties mitigated difficult living conditions. Five Points, so called due to the five-cornered intersection of five streets, acquired a reputation as a place of crime, prostitution, and disorder. But it primarily served as a home and workplace for a struggling and burgeoning working-class population. By the mid-nineteenth century, Irish immigrants and their children—the largest immigrant group in New York City—constituted 75 percent of Five Points’ population. German-speaking immigrants composed the second-largest group (approximately 20 percent), and of these, approximately half were Jewish. Most of the Jews living in Five Points came from Posen, Polish territory then governed by Prussia.38

The city had created the Five Points neighborhood by filling in and building over the Collect Pond. Never properly drained, the pond regularly flooded the two-and-a-half-story wooden structures constructed on it. Yet Five Points’ stables, workshops, and factories provided a convenient combination of work and residence, making it a prime destination for tens of thousands of immigrants who sought affordable rent and housing close to work. As a result, the dilapidated wooden homes contained far more inhabitants than one might expect. The first floors often housed stores, and backyards had additional sheds and workstations. Soon, a great demand for homes and work in this neighborhood led property owners to tear down the old wooden structures in order to build brick tenements. But the tenements’ crowdedness, dark interior spaces, and cellars made for miserable housing.39

Like other ethnic groups, immigrant Jews settled in specific blocks and even certain tenement buildings. But blocks with a high proportion of an immigrant group retained a heterogeneous population. In other words, just because a block was known as “Jewish” did not mean that all the shops or all the residences were necessarily Jewish.40

Newcomers often relied on ethnic ties to gain a foothold. Employers, conversely, looked to members of their own ethnic groups as workers on whom they could rely and with whom they could easily communicate. Neighborhoods like Five Points offered not only jobs but also Jewish community networks. These helped newcomers directly even as more established Jews used them to create an American Jewish identity that involved caring for coreligionists in need. Informal neighborhood networks developed fundamental elements of more formalized charitable organizations as the numbers of Jews grew. In an ethnic economy, people depended on those whom they knew, usually from a shared hometown and family, to get started. This help benefited the giver, too. Such work propelled individuals forward, even as it knit together a tight ethnic economy.41

Thus, while Jews might bicker in their synagogues, they forged ties with one another in the streets. They helped one another find jobs, expand business networks, and form community in shops and on street corners. Over time, this community even survived its members’ dispersal. As Jews moved uptown with socioeconomic success, they still returned to Five Points to visit the old synagogue, patronize Jewish book dealers, and buy Passover groceries and matzo. They relied on Five Points for jobs for their children, Jewish connections and sustenance, and social ties for themselves.42

New York in the three decades before the Civil War emerged as the nation’s most vigorous municipality. It grew to a metropolis numbering 814,000 in 1860. At the hub of the nation’s growing rail system, Gotham became America’s leading manufacturing center. The city housed the heart of the nation’s garment trade, major iron works, and a multitude of assorted industries such as the Singer Sewing Machine Company. New York’s merchants established the country’s first department stores.43

These opportunities for labor attracted immigrants, but they clustered in specific industries and occupations, initially reflecting skills and experience they had brought with them. Subsequently, ethnic connections facilitated finding work and expanded economic niches. Irish immigrants arrived extremely poor, with only agricultural experience, and most entered laboring jobs. By the mid-nineteenth century, they composed the majority of New York’s longshoremen, shipyard and warehouse workers, quarrymen, and construction workers. Germans possessed more money and experience in trades and crafts such as carpentry, tailoring, shoemaking, tanning, pottery, bricklaying, and weaving. They found work in many trades and also introduced new ones, such as piano manufacture, to the city.44

Immigrant Jews similarly found their niche, most importantly in peddling and selling used clothing. Given a “hastily fixed up basket,” a new immigrant was “hurried into the country.” Jews applied their old-country experience to their new situation, supplying demand in city and countryside. Perhaps half of immigrant Jews took up peddling when they arrived. Peddling involved Jews who settled in small towns in the South and new cities in the Midwest. Many peddlers assiduously worked to ascend the socioeconomic ladder that led from peddler to dry-goods merchant. The myth of ascent appealed to many immigrants, but some preferred the security of the ethnic neighborhood. Others worked as tailors or shoemakers, also using skills they had previously learned. These Jews joined their fellow German immigrants laboring in similar trades.45

Peddlers expanded their businesses by developing ties with Jews elsewhere in the country, much as Jewish merchants had developed networks around the Atlantic in the previous century. By 1860, the majority of the sixteen thousand peddlers in the United States were Jewish, which enabled New York Jewish merchants to take advantage of regional and even national markets. Thus, Jewish peddlers facilitated the growth of New York suppliers. Subsidiary wholesale and manufacturing centers, like Cincinnati, emerged, led by transplants from the shops and warehouses of New York.46

Jewish peddlers often specialized in the sale of secondhand clothing. In these years, only men at the bottom of the socioeconomic ladder—sailors, miners, or slaves—wore ready-made clothing. Most Americans stitched clothes at home, had clothes sewn by a custom tailor, or bought reconditioned used garments. While few Jews worked as custom tailors, many Jews were secondhand clothing merchants, who took in, cleaned, and renovated old clothing, preparing it for both retail and wholesale markets. Often “an object of ridicule and contempt,” the secondhand clothing trade facilitated Jews’ contribution to an emerging garment industry, despite the fact that they played no role in such technological advances as the invention of the sewing machine. Jewish secondhand traders actually “renovated” the traffic, incorporating innovative commercial ideas as well as experimenting with production of new clothes on the side. At first, New York Jews dabbled in the production of cheap clothing—“slops.” A dry-goods merchant with cloth in stock risked little by hiring workers to produce inexpensive ready-made clothes, a process of gradual transformation from merchant into small manufacturer.47

Opportunity and mobility existed for a minority. Contemporary observers credited Jewish peddlers with introducing the installment plan (selling on “time”), direct selling, and lower prices, made possible by a willingness to maintain a smaller profit margin. Connections with Jews in London encouraged a transatlantic traffic in used clothes and facilitated a transition for some from peddler to merchant standing within a decade. Workers in the nascent garment industry joined successful peddlers and native-born Jews in manufacturing and selling clothes, wholesale or retail.48

Jews in New York acquired a reputation especially for their shops downtown in the Chatham Square neighborhood. “Clothing stores line the southern sidewalk without interruption, and the coat-tails and pantaloons flop about the face of the pedestrian,” wrote an observer. “In front of each, from sunrise to sundown, stands the natty, blackbearded and fiercely moustached proprietor,” the account continued. “Stooping as you enter the low, dark doorway, you find yourself in the midst of a primitive formation of rags, carefully classified into vests, coats and pantaloons.” These Jewish shopkeepers embarrassed Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise, who was always well dressed with vest, jacket, tie, and crisp white collared shirt. He deemed the area a “disgrace.” However, these modest Chatham shops formed the nucleus of a rapidly expanding international trade and a growing ready-made clothing industry. On the eve of the Civil War, the value of the clothing market in New York reached $17 million.49

The Civil War demanded production of uniforms, and Jewish merchants eagerly filled orders. This effort helped to propel Jews from the margins to the center of clothing manufacture. Both those already involved in the clothing business and those lacking any experience whatsoever jumped at the contracts to set up shop. Without time to measure each soldier, suppliers developed a system of standardized sizes. This facilitated rapid production of uniforms but also mass production for a civilian market.50

As the Civil War helped transform an undesirable secondhand-clothing trade into a garment industry, so some Jewish owners of Chatham dry-goods shops made a comparable transition to proprietors of small firms. This transformation materialized in cast-iron loft buildings arising on Broadway, that long street that ran from the base of Manhattan diagonally up to its northern tip. Walking up Broadway from Canal Street to Union Square, an observer noted how the occupants of some four hundred buildings were almost all “Hebrews,” counting “over 1000 wholesale firms out of a total of 1200.” More than Broadway bore witness to Jewish commercial mobility since Jewish firms similarly predominated “in the streets contiguous to Broadway.”51 But even as these impressive buildings had risen, with the names of Jewish merchants above their doors, thousands of Jewish immigrants were pouring into miserable tenements to the east. When the owners of the Broadway warehouses had lived on those streets, they had been a part of Kleindeutschland. Now their employees found themselves on the renamed Jewish East Side.

Religious Quarrels

In the years leading up to the Civil War, specifically Jewish religious quarrels divided New York Jews. Their struggles with each other over questions of tradition reflected not merely efforts to fashion a mode of religious life compatible with metropolitan demands but also desires to articulate a vision to guide the future of Judaism in the United States. The movement to reform Jewish religion in both its rituals and core doctrines agitated Jews in New York and throughout the United States. Ultimately, as it produced numerous variations, it transformed all forms of Jewish religious practice into minority expressions. While the battle for the hearts and minds of American Jews began in Charleston, South Carolina, in the 1820s, it reached new dimensions in New York. The city’s affluence encouraged congregations for the first time to recruit rabbinic leaders, who carried in their baggage some of Europe’s contentious debates over religion. Their vigorous arguments, amplified by New York’s position as the nation’s leading media center, mobilized masses of supporters that produced key institutions influencing the rise of not only Reform but also modern Orthodox and Conservative Judaism. Moments of cooperation accompanied the ebb and flow of disputes determining a distinctively urban form of Judaism in the city, its lineaments shared by the entire spectrum of Jewish religious practice.52

Rooted in central Europe, Reform Judaism spread with Enlightenment ideas in response to a protracted emancipation process granting Jews civil and political rights. Seeking Christian approval for full citizenship and desiring to have Judaism reflect the spirit of the age in order to be intellectually and spiritually satisfying, European reformers adjusted Judaism to modern behavioral norms and philosophy. They hoped this process would also inspire and retain new generations of Jews. Reformers tinkered with Sabbath services, shortening them, adopting stricter rules of decorum, and adding instrumental music. Rabbis introduced reading the Torah on a three-year rather than annual cycle and abolished the second day of festivals. Yet even such modest changes as German-language sermons, mixed choirs of men and women, and organ music encountered resistance. Whether opposition came from Jewish or governmental authority, it hampered the “free development” of Reform.53

No such restrictions constrained Reform in the United States. Reform Judaism prospered in the United States, where religious freedom and capitalist enterprise encouraged dramatic changes and where opportunities for full expression prevailed. As Jews struggled to fulfill the obligations of traditional Jewish practice, they simultaneously established Orthodox congregations and ignored demands of personal observance. Many immigrants, intent on getting businesses off the ground or enjoying newfound social opportunities, neglected both synagogue attendance and regular daily prayers. Statistics suggest that half of all American Jews chose not to affiliate with any congregation by 1850. No centralized authority guided congregations as they attempted to alter traditions to modernize worship. Self-governing, congregations made their own rules and elected their own ministry. This freedom produced variations, as each congregation found its own way to reconcile Judaism with American culture.54

While many Jews gave up on congregational life or chose a secular alternative to the synagogue in B’nai B’rith, a handful decided to try to remake the synagogue. The founders of Temple Emanu-El, much like the men of B’nai B’rith, also worried that existing synagogues repelled youth. But unlike B’nai B’rith, they explicitly desired a new religious community. In choosing the name Emanu-El—“God is with us”—they expressed their intention to stay within the bounds of Judaism. While they hoped that reform would enable them “to occupy a position of greater respect” among their fellow citizens, they also yearned to “worship with greater devotion.” Eager to keep Judaism relevant to others like themselves, they embraced reform in order to “save Judaism” from a perceived straitjacket of outdated forms imposed by fanatical traditionalists.55

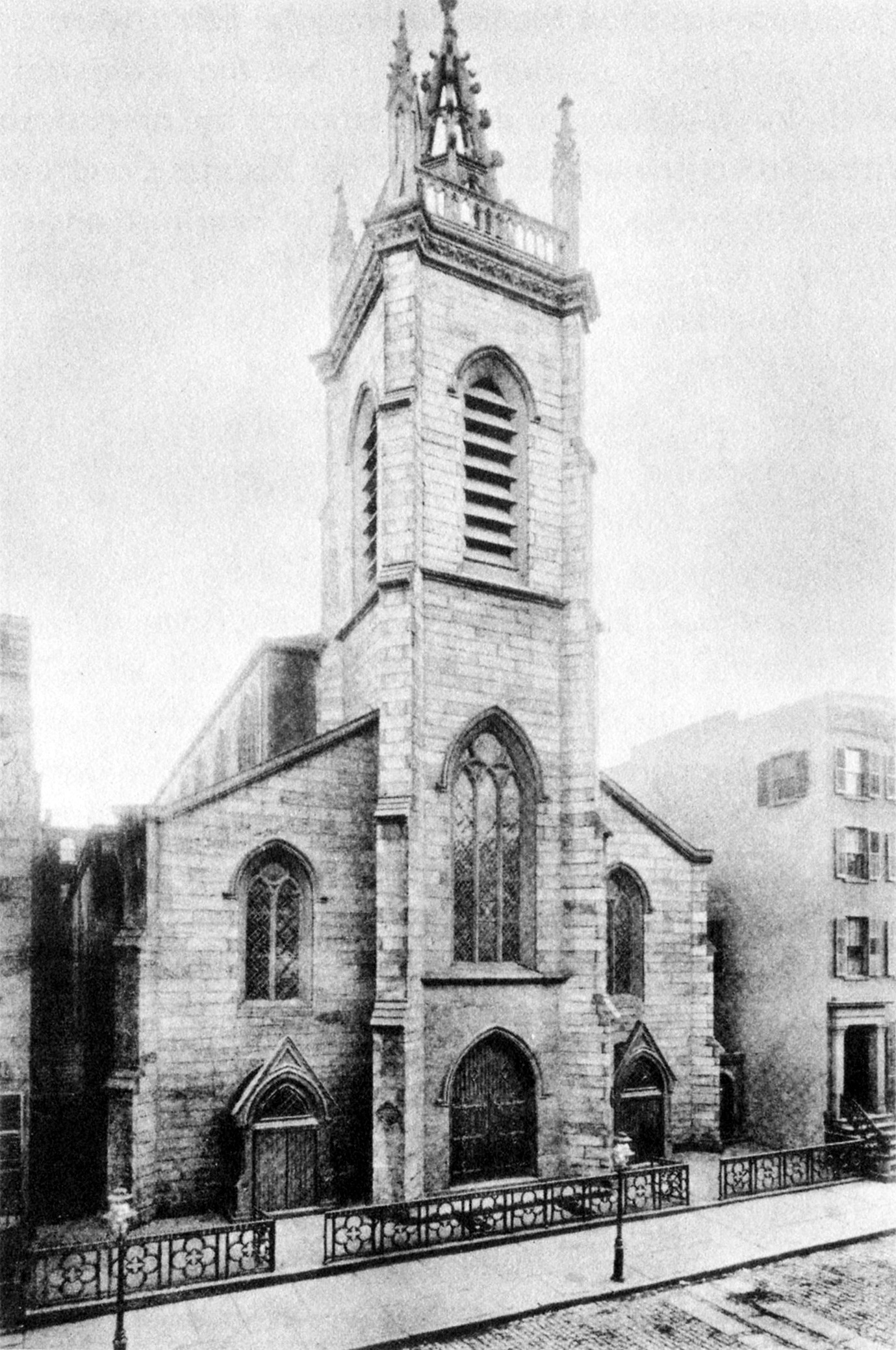

New York’s first Reform congregation slowly altered worship to blend devotion to the divine and fidelity to the new age, initially mostly through decorum that matched its aesthetic aspirations. Keeping the traditional prayer book, the congregation added vocal music, German-language hymns, and a German-language sermon. Yet the congregation also initially upheld many critical elements of traditional Jewish life, practices they would later reject: Jewish dietary laws (kashrut), separation of men and women during prayer, and prayer shawl and head covering for men. Overall, Emanu-El’s approach attracted new members, enabling it to expand. Moving into a former church spurred additional reforms. Emanu-El decided to read the Torah on a three-year cycle, introduced an organ, and minimized requirements for boys studying to become bar mitzvah. In short, it strove to modernize in order to strengthen, not diminish, Judaism.56

Each of these changes alienated some congregants and elicited ire from traditionalists in the press, but Emanu-El flourished. It drew ever more worshipers and grew bolder in its reform initiatives. It introduced a new prayer book that eliminated a host of theological beliefs (the concept of a chosen people, the coming of a personal Messiah and resurrection of the dead, restoration to Zion, and resumption of sacrifices) and ritual practices (observance of the second day of festivals). Soon other Reform congregations adopted the prayer book, a sign of Emanu-El’s influence. Emanu-El also abandoned prayer shawls and no longer required hats. Then, in an aggressive move, it required all men to go bareheaded.57

Temple Emanu-El, the city’s only Reform congregation, grew rapidly from a small discussion group. In 1854, it purchased a large Baptist church on Twelfth Street. Transforming the church into a synagogue, Temple Emanu-El ended the traditional Jewish practice of separate seating of men and women. Temple Emanu-El became one of the city’s most influential synagogues, supported by many wealthy Jewish immigrants. Reproduced from Synagogue Architecture in the United States: History and Interpretation by Rachel Wischnitzer by permission of the University of Nebraska Press. Copyright 1955 by the Jewish Publication Society of America.

Most boldly, the congregation introduced family seating. Emanu-El was the first Jewish congregation in New York and only the second in the United States to allow men and women to sit together during services as they did in mainstream Christian denominations. While a radical innovation from the perspective of Judaism, Emanu-El’s family seating seemed to its members merely the next step in its efforts to meet American social standards. To seat men and women together distinguished Emanu-El even from Reform practice in Germany. Other New York congregations that had adopted some of Emanu-El’s reforms at first shied away from family seating, as did reforming congregations in other American cities. (New York’s second-oldest synagogue, B’nai Jeshurun, adopted family seating in 1875 only after a fight that led to a civil court case.)58

Debates over mixed seating reflected reconsiderations of women’s position in Judaism. Emanu-El replaced the bar mitzvah service, which made “no impression on the boy,” with a confirmation ceremony that received “sons and daughters into the same covenant.” Gender egalitarianism expressed, in part, a desire to emulate the spiritual milieu of Protestant churches, where women’s presence mandated conventions of dignified bourgeois behavior. Nineteenth-century American Christianity underwent a period of “feminization” as women became mainstays of church congregations, the most reliable attendees at Sunday services, the most conscientious members of committees, and the most pious congregants. Jewish women’s fate was entwined with the Jewish community’s quest for respectability in the Christian world. But this was only one consideration. Reform ideology extended beyond emulation of Protestant society to reinforce the movement for women’s political, social, and economic equality. Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise termed a traditional morning prayer in which a man thanked God that he was not created a woman “an insolence.”59

Such concerns for women’s rights did not extend to synagogue governance. A tradition of male lay control held sway at Emanu-El as in other Jewish congregations. The temple’s trustees included some of the city’s most prosperous central European immigrants. Its ritual committee regularly overruled its rabbi, who could conduct no marriage ceremony without the board’s permission. Concerned with decorum, the board paid attention not only to what Jews said during worship and how they prayed, but also to how they dressed. It expected elegant clothes on the part of men and women attending services. The board regularly invited prominent reform figures to lecture and recruited talented, highly educated leaders. Under this spirited management, Emanu-El grew rapidly both in numbers and in wealth.60

With Temple Emanu-El as the Reform movement’s base, reformers challenged traditionalists in debates that reverberated in the streets, pulpits, and Jewish press. Reformers grounded their creed in a wedding of science and Judaism, arguing that Judaism must stand the test of modern investigation. This included thought and ritual. Reformers argued that Judaism evolved over the centuries. Talmud mirrored a distant past containing wisdom but also ceremonies and commandments that were lifeless in the modern era. Many rabbinic customs (minhagim) derived from cultures of nations with whom Jews lived in the Diaspora. Science demonstrated that the Bible was divine in its creation but Talmud was not. Reformers harshly condemned many Jewish rituals. For example, they ridiculed the requirement that a man cease shaving for thirty days after the death of a mother or father and disparaged the eleven months of mourning.61 They attacked kashrut, a bastion of traditionalism; a kosher table should not be the “diploma of a good Jew.”62

These spirited attacks did not go unanswered. By midcentury, New York emerged as a center of both Reform and Orthodox Judaism due to the presence of leading intellectuals in both camps. Reform Jews had a voice in the influential Asmonean and Orthodox Jews in the Jewish Messenger. New York housed the nation’s foremost Reform synagogue, Emanu-El, supported by the city’s wealthiest Jews, as well as Shearith Israel, its oldest Orthodox synagogue.

Growth in both population and affluence facilitated recruitment of men educated in Jewish learning and secular studies. Their arrival in Gotham transformed the city into American Judaism’s intellectual center. The most prominent Orthodox leaders were Samuel Myer Isaacs of Shaaray Tefilah and Morris Raphall of B’nai Jeshurun. Isaacs, a tall and somewhat dour personage with mutton-chop whiskers, cut a very different figure from the short and stout Raphall. Both, however, had spent time in England before coming to New York City, thus helping to knit an English-speaking diaspora connecting the United States with Great Britain. Both gave sermons on a regular basis. Raphall eagerly spoke wherever he could, traveling throughout the country. Isaacs used his Messenger newspaper to spread his ideas and attack reform.63

Despite rabbis’ superior knowledge of Jewish religion and history, they deferred to boards of trustees, which remained by law the congregational governing bodies and zealously guarded their prerogatives. Each considered its rabbi an employee, along with the shochet and shamash. The boards did not want any employee speaking about controversial subjects, jeopardizing its standing in the community.64

New York congregations occupied all points on a spectrum from traditional orthodox practice through to radical reform. On average, a new congregation appeared each year for various reasons. Most new congregations organized around immigrants’ place of origin. But other issues prompted splits: a willingness to accept proselytes, contested elections to the Board of Trustees, demands for religious observance outside synagogue, hiring of a shochet, even antagonism to new immigrants. These schisms demonstrated the influence of New York’s religious pluralism and openness to religious entrepreneurship, which transformed disputes over ethnicity, personality, and ideology into new congregations.65

Yet in moments of crisis, New York Jews temporarily put aside their religious differences. The largest outcry arose over the Mortara case in 1858, in which a Jewish child was torn from his home in Italy under Catholic law because a family servant had secretly had him baptized at age six. Synagogues led and hosted protest gatherings. At a mass meeting, the assembled adopted a resolution condemning the “kidnapping.”66

This mobilization instigated an effort to establish an American Jewish union. The Orthodox Jewish Messenger pleaded for a national board of Jewish congregations to enable Jews to have a greater influence in national affairs. Almost two dozen congregational representatives from cities ranging from New Orleans to St. Louis met in New York and established the Board of Delegates of American Israelites with headquarters in New York. It pledged no interference in either party politics or internal congregational affairs. But this did not prevent Reform congregations from boycotting along with Shearith Israel, which never felt comfortable with Ashkenazi congregations.67

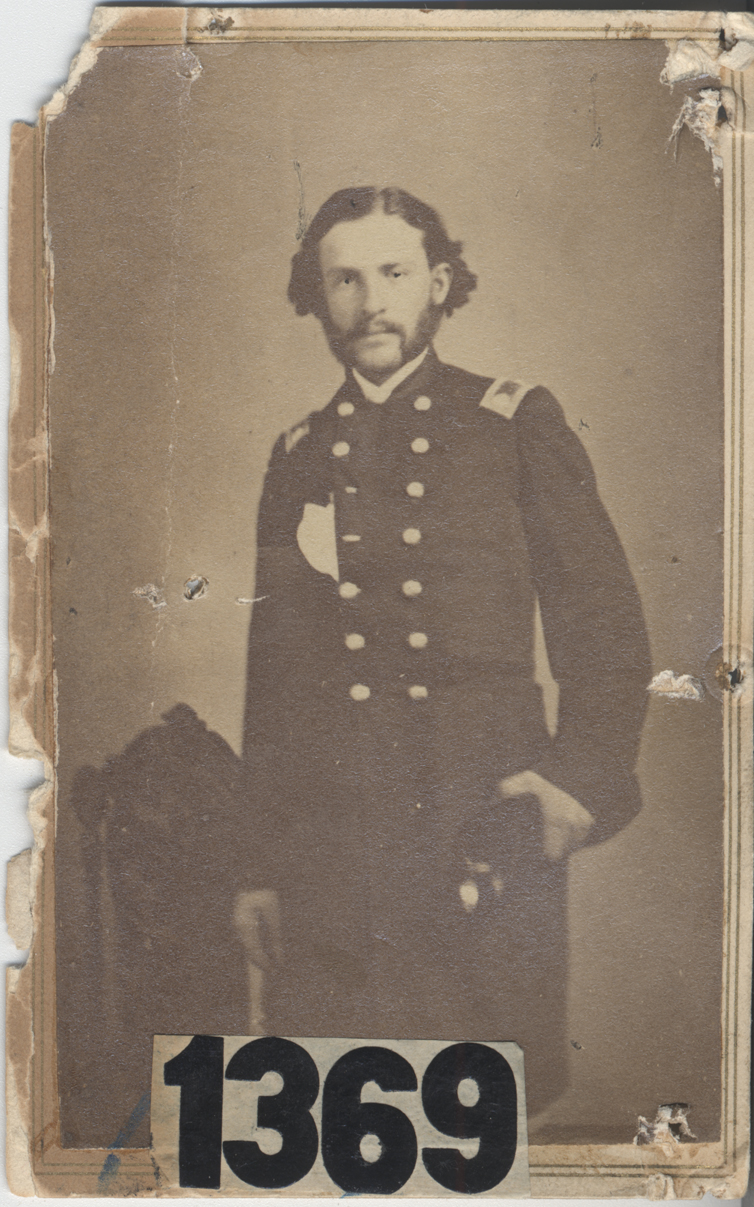

Leopold Newman, in uniform. A Columbia-educated attorney and poet, Newman joined New York’s Thirty-First Regiment and fought at the battles of Bull Run and Antietam. Rising to lieutenant colonel, he was hit by grapeshot in the leg and taken to Washington, DC, where he died while surgeons amputated his leg. President Lincoln visited him at bedside and promoted him to brigadier general. Courtesy of the New York State Military Museum.

Changes wrought by successive revolutions in industry and commerce, politics and society, religion and culture transformed New York City into a major metropolis, filled with immigrants as well as an extraordinarily wealthy elite. New York Jews participated in these transformations that dramatically recast their religious and communal worlds. As the Civil War approached, they stood poised to confront decades of contention pitting competing groups of Jews against each other. Yet these civil conflicts served as both prelude to and context for significant struggles to forge forms of community among New York Jews.

Debating Slavery

Abraham Lincoln had just been elected president of the United States. South Carolina and other southern states were seceding from the union, although Lincoln had not yet been sworn into office. The future did not look promising that Sabbath in January 1861 as Rabbi Morris Raphall ascended the bima (elevated platform) of B’nai Jeshurun and surveyed his congregants. His congregation, the first one to break away from Shearith Israel, had prospered, moving uptown to a new and more spacious building on Greene Street, north of Houston. Rabbi Raphall, too, had flourished in the city. His English-language sermons had vaulted him to an enviable position as New York’s most prominent Jewish spiritual leader, the first rabbi invited to open a session of Congress in 1860. Now, with the union in peril, the bearded and bespectacled Raphall stepped forward to tackle the tough question of slavery and the Bible. Though no “friend to slavery in the abstract” and still less “to the practical working of slavery,” he claimed that his personal feelings were irrelevant. Invoking the biblical story of Noah and his son Ham, the Orthodox rabbi concluded that, aside from family ties, slavery was the oldest form of social relationship. For viewing his father’s nakedness, Ham and his descendants, the black race, were cursed to become slaves.

The Bible, Raphall explained, differentiated between enslaved Hebrews, who as slaves for limited periods were to be treated as any other Hebrew, and non-Hebrew slaves and their progeny, who were to remain in bondage during the lives of their master, his children and his children’s children. Non-Hebrew slaves provided the relevant model for southern slavery. Hebraic law permitted masters to chastise these slaves short of murder or disfigurement and required that a slave who fled from Dan to Beersheba be returned, as must the slave absconding from South Carolina to New York.68 While Raphall cautioned southerners that slaves must be protected from lustful advances, hunger, and overwork, he emphatically concluded that the Bible sanctioned slave property.69

Raphall’s sermon created a sensation. Three New York newspapers published the text in full. Southern sympathizers distributed it throughout the country.70 Raphall was not the first New York Jew to enter the debate on slavery, however. Several influential newspaper editors preceded him.

The question of slavery dominated politics in the antebellum era, reaching a fever pitch in the 1850s and drawing Jews into its debates. Most prominent Jewish leaders in New York opposed abolition and, to varying degrees, supported slavery. While they spoke for themselves, the absence of strong voices in favor of abolition differentiated Jewish leaders from New York Christian spokespeople. In 1856, a straw poll of “twenty-five of the prominent clergy” in New York revealed that twenty-three of them backed the Republican antislavery candidate for president.71 Jewish rabbis’ reluctance to support antislavery candidates for president suggested that many Jews acquiesced in slavery and did not desire to abolish it. These attitudes among Jewish and Christian clergy initially emerged in the 1840s.

Considered by many Christians to be the “most important Jew in America,” Mordecai M. Noah, a playwright, former U.S. consul at Tunis, sheriff and surveyor of New York, Democratic Party leader, and newspaper editor, proudly declared, “I was always a friend of the south.” Through his paper, he encouraged New Yorkers, particularly merchants, to develop close ties with southerners. He considered slavery a common good. Blacks, he claimed, were “anatomically and mentally inferior a race to the whites, and incapable, therefore, of ever reaching the same point of civilization, or have their energies roused to as high a degree of enterprise and productive industry.” They could be content only in servile positions. Emancipation would jeopardize the country’s safety. Noah wished to make publication of antislavery literature a punishable offense. Abolitionists were dangerous. They strained relations between merchants and southern traders. At war with America, they jeopardized the Union.72

Robert Lyon, the editor of the Asmonean, also edited the New York Mercantile Journal, a paper reputed to carry “great influence over the minds of many commercial men.” His newspapers reached both local and national audiences. A Jewish religious progressive, Lyon opened the pages of the Asmonean to advocates of reforming Judaism. A staunch Democrat, he endorsed prosouthern Democrats for president and governor in 1856. Given Lyon’s detailed knowledge of the Jewish commercial world and his consultation of “the wishes and desires of the majority of [the paper’s] supporters,” his political leanings likely reflected those of the city’s Jewish business community. Lyon despised abolitionists as much as Noah did and urged Americans “to crush out for once and forever the attempt to plunder our Southern citizens of their property.”73

The Asmonean supported enforcement of the controversial Fugitive Slave Act, which required police to turn over an alleged fugitive solely on the affidavit of a master, denying the fugitive the right to speak in court. The act was “the law of the land.” While Jews might purchase a slave’s release, they could not endanger “national and even international peace by gaining his freedom through violence,” he wrote. Jews owed their renewed sense of self-confidence and comfortable position to America; they must “stand by the constitution, now and forever.”74

These outspoken leaders expressed views held by many Jewish New Yorkers. An abolitionist report perspicaciously noted, “Jews of the United States have never taken any steps whatever with regard to the Slavery question,” although Jews were often “the objects of so much mean prejudice and unrighteous oppression.” Most Jews avoided the subject of slavery, nervous that Jewish political engagement might spark anti-Semitism. Jews observed how the Irish suffered after their more forceful entry into local politics. When Raphall delivered his controversial proslavery sermon, B’nai Jeshurun’s board did not reprimand him over his position on slavery but rather objected to “the impropriety of intermeddling with politics.” In 1860, Abraham Lincoln commanded only 35 percent of the city’s vote. German-immigrant wards where most Jews lived voted two to one against him.75

Abram J. Dittenhoefer, who grew up in South Carolina, was an exception among New York Jews. He not only championed abolition but also worked on Lincoln’s campaign. Dittenhoefer attended Lincoln’s Cooper Union address in 1860, and despite the raspy quality of Lincoln’s voice, thought “his earnestness invited and easily held the attention of his audience.” The address launched Lincoln’s successful run for the Republican nomination. Dittenhoefer later called it “epoch-making.” Few New York Jews shared these sentiments. In fact, Dittenhoefer’s father counseled his son, when he was a young law student, to become a Democrat as a public career because a Republican “would be impossible in the City of New York.” He later reminisced, “One can hardly appreciate to-day what it meant to me, a young man beginning his career in New York, to ally myself with the Republican Party. By doing so,” he explained, “not only did I cast aside all apparent hope of public preferment, but I also subjected myself to obloquy from and ostracism by acquaintances, my clients, and even members of my own family.”76 Dittenhoefer made an unusual decision. Most New York Jews aimed to fit into society. Unpopular positions did not win friends.

Only rarely did New York Jews identify southern slavery with the Israelite sojourn in Egypt; Dittenhoefer did. He pointedly observed that an Israelite, “whose ancestors were enslaved in Egypt, ought not to uphold slavery in free America, and could not do so without bringing disgrace upon himself.”77 Each year, numerous Passover articles in the Jewish press refused to equate the two. Ancestral Israelites and black slaves existed in two different worlds. Racism undoubtedly pervaded Jewish society as it did much of American culture.

By 1860, many of New York’s Jews—merchants, wholesalers, retailers, and even garment workers—considered the southern trade their lifeblood. Southern planters and merchants owed New York firms $200 million in 1860; war would wipe out that enormous debt. Unsurprisingly, New York capitalists desperately sought compromise, sending delegations to Washington, DC, in hopes of preventing secession. Jews and others faced loss of trade and the panic of bankruptcy if the Union dissolved. For many, this proved reason enough to oppose the Republican platform. In addition, the Union’s collapse imperiled political security. The Constitution of New York State and the U.S. Constitution provided protections for Jews that existed in few other places in the world.78

The Civil War triggered a spike in anti-Semitic sentiment. It had grown as the city’s Jewish population increased, neighborhoods became recognizable as Jewish, and Jewish merchants gained financial standing. Visibility worsened impressions of Jews. Newspapers and magazines commonly pictured them as parvenus rapaciously climbing the economic ladder as they flaunted material success and opulence. Unlike other forms of anti-immigrant sentiment that singled out the poor for attack, anti-Semites targeted those who achieved financial stability. Even reputable papers that were favorably inclined toward Jews reported stories confirming a Jewish propensity for dishonest commerce and targeting Jews working in the stock market. By 1860, the terms “Jew” and “Jew one down” as verbs, meaning to haggle on a price and bargain in a miserly way, had entered the American lexicon, nowhere more so than in New York. Religiously motivated attacks on Jews as infidels and “malicious, bigoted hypocrites” accompanied a revival of evangelicalism. Educated men harbored anti-Jewish feelings. A Walt Whitman prose sketch described “dirty looking German Jews,” while a Herman Melville short story about Manhattan depicted “a Jew with hospitable speeches, cozening some fainting stranger into ambuscade, there to burk him.”79

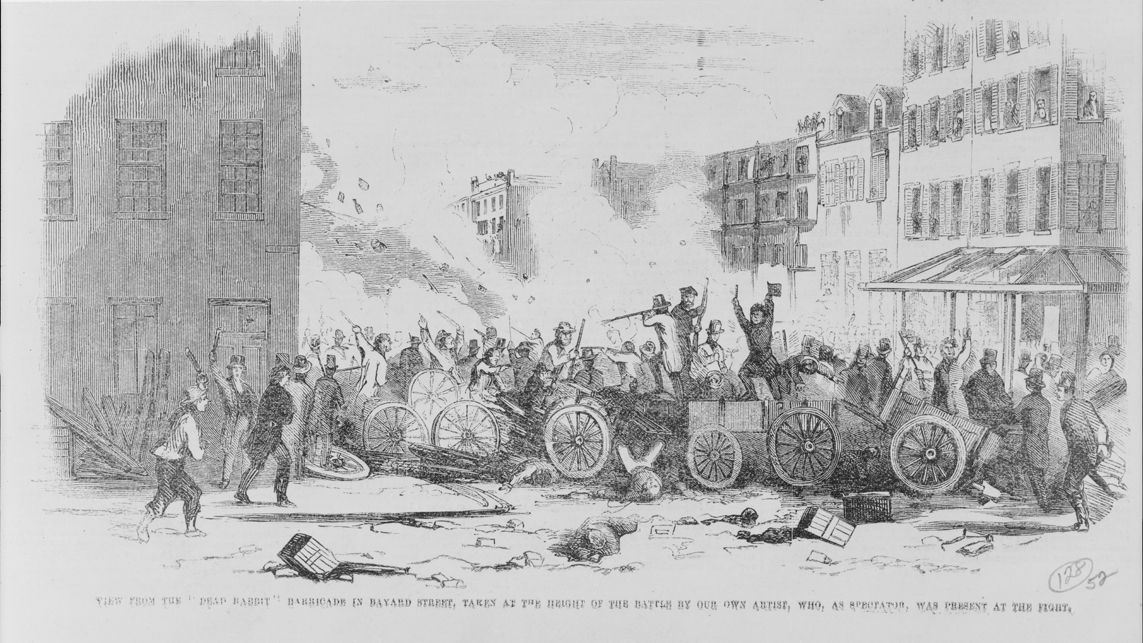

Street barricades in New York, 1857. When the Republican state legislature, led by temperance reformers, attempted to implement prohibition of alcoholic beverages, riots resulted. Irish and German immigrants fought militias in the streets. This violence foreshadowed other conflicts between Republicans and Democrats in the city. Courtesy of the New-York Historical Society.

But these attacks paled in comparison with General Order No. 11, “the most sweeping anti-Jewish regulation in all of American history,” which rattled the Jewish community of New York. On December 17, 1862, General Ulysses S. Grant, terming Jews “a class violating every regulation of trade established by the Treasury Department,” commanded their immediate expulsion from his military department, an area that included northern Mississippi and parts of Kentucky and Tennessee. Once a Jewish emissary informed Lincoln of the act, he immediately revoked the order. But that didn’t satisfy New York Jews. When a “committee of Jews” in the city “took it upon themselves” to applaud Lincoln for “annulling the odious order,” the “bulk” of the city’s Jews rebuked them, according to the New York Times. Grant, they averred, should have been summarily dismissed.80

By comparison, other anti-Semitic slurs seemed almost routine. These slanders claimed that Jews were cowardly and crooked, lacked patriotism, favored the draft, and remained far from the battlefield while they profited from shoddy war production. Some charged that Jews manipulated the gold exchange. Others accused Jews of being copperheads (southern supporters), claiming that the banker August Belmont, “the Jew banker of New York,” was leading a conspiracy of Jewish bankers in a plot to support the Confederacy. Belmont represented the Jewish banking house of Rothschild in the city and was an ardent Democrat, serving as chair of the Democratic National Committee in the late 1850s. He had converted to Episcopalianism, but that did not prevent people from identifying him as a Jew. The anguish of a long, bloody war heightened anti-Semitism in the city.81

These simmering ethnic, religious, and racial conflicts burst out into the open in the summer of 1863. Enraged over a lottery draft, Irish and German workers rioted as resentment soared against blacks, blamed as the cause of the war, and against the wealthy, who could buy out of the draft. For three days, gangs stalked New York’s streets. Barricades blocked avenues and alleys. Crowds attacked German garment stores, including those owned by Jews, and houses in wealthy neighborhoods. Mobs lynched blacks in the streets and set fire to the Colored Orphan Asylum. The official count listed 2,000 wounded and 118 dead, though many more may have perished. The riot, “considered one of the worst civil insurrections in American history,” ended when the secretary of war ordered soldiers fresh from the battle of Gettysburg to the city. The Jewish General William S. Mayer, an immigrant from Austria, received a personal note of thanks from President Lincoln for his service during the uprising. Mayer had raised a regiment from New York as a colonel, although he was too recent an immigrant to have acquired citizenship.82

In 1864, Lincoln carried only 33 percent of the city’s vote, doing no better than in 1860 despite recent Union victories presaging an end of war. But some Jewish attitudes toward the war had shifted, as most industrialists and merchants turned to the Union side. After a difficult initial year, the city’s men of commerce had prospered. The Hendrickses’ copper manufactory, founded by Harmon Hendricks, one of the city’s wealthiest Jews, operated at full capacity during the conflict; garment manufacturers, like Joseph Seligman, supplied the army’s seemingly endless needs. Republicans and industrialists forged a common economic bond. But the working classes suffered. Wages stagnated as inflation eroded living standards. The working-class vote produced a sizable Democratic majority. Still, while Germans favored the Union more than the Irish did, not a single German ward in Kleindeutschland gave a majority of its votes for Lincoln. German Jews tended to identify with Christian Germans, so their vote probably did not differ from that of their fellow immigrants.83

Lincoln’s assassination and Union victory gradually changed Jewish attitudes. New York Jews turned out to mourn the murdered president as his body traveled by train across the country, through the city, and back to Springfield, Illinois. B’nai B’rith marched in the funeral procession, and even B’nai Jeshurun participated in the memorial ceremony. The arrival of hundreds of thousands of Jewish immigrants in the years after the Civil War transformed Jewish attitudes toward Lincoln. These newcomers brought an implicit sympathy for “honest Abe” on the basis of European depictions of him. In later decades, rabbis regularly honored Lincoln as the great emancipator, integrating him into a Jewish pantheon of heroes, recalling his rise from humble beginnings, and quoting his biblically phrased speeches. New York Jewish support for slavery and the South faded from memory, as new immigrants arrived with no experience and little knowledge of the Civil War.84

These immigrants entered a very different city from the southern-sympathizing one of the pre–Civil War era. Although they built on foundations established by Jews who had preceded them, they also innovated. As their numbers soared to over a million, New York Jews gradually transformed the city itself, remaking its politics, reinterpreting its culture, and enhancing its economic power.