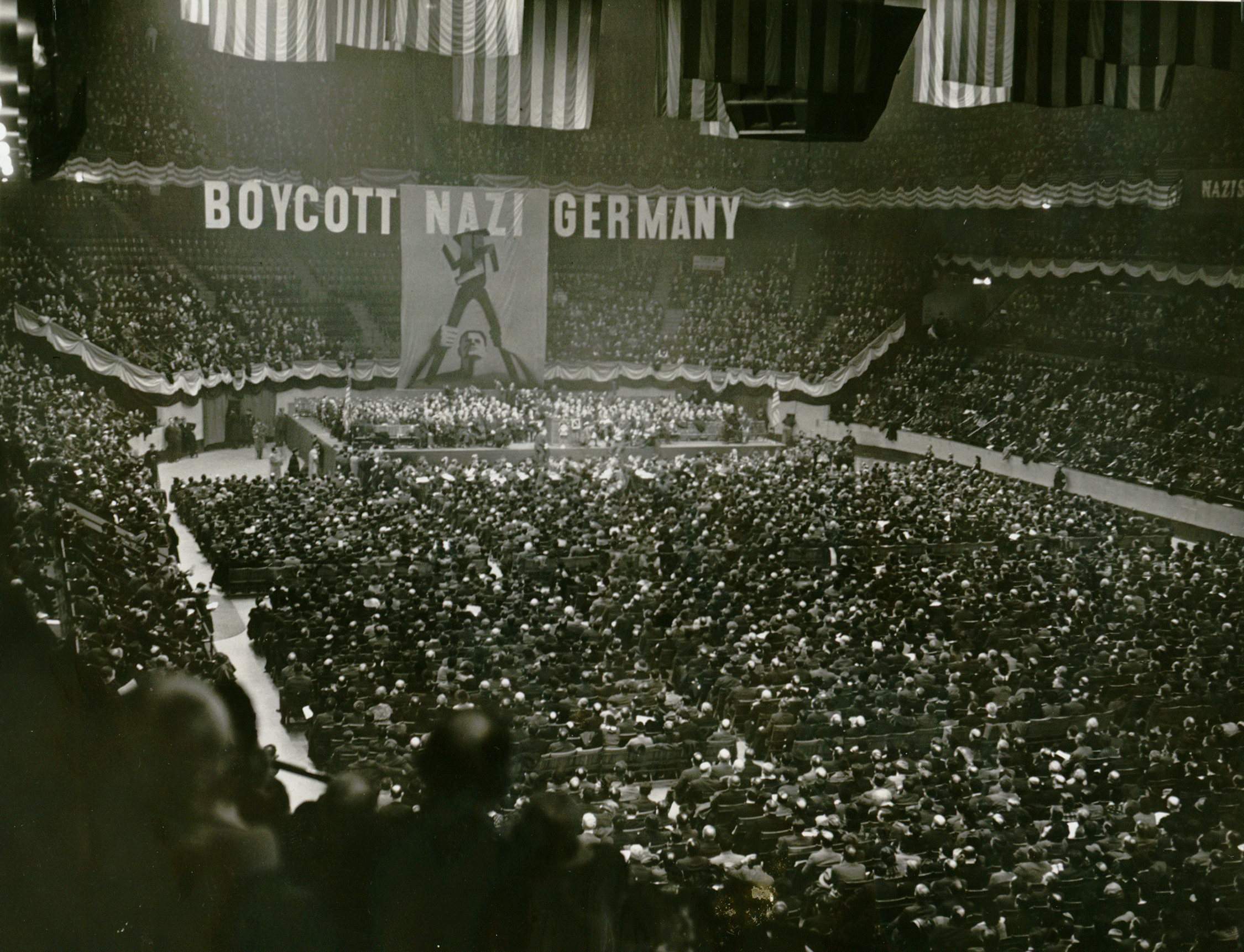

Anti-Nazis hold a demonstration, March 15, 1937. Thousands of opponents packed Madison Square Garden in a demonstration of support for a boycott of Nazi Germany. Facing an increasingly dire situation in Germany, the socialist Jewish Labor Committee and Zionist American Jewish Congress joined forces to keep up economic pressure on the Third Reich. With the help of sympathetic longshoremen and labor leaders, they cooperated in prosecuting a boycott of German products and services at the port of New York. Those who attended the rally hoped to influence Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who had just been elected to a second term as president. Courtesy New York World Telegram & Sun Newspaper Collection, Library of Congress.

9

Wars on the Home Front

After the American Revolution, New York was never a war zone until September 11, 2001. Still, reverberations from overseas wars reached the city and fomented conflict. Ideological and theological beliefs inflected Jewish attitudes toward European political struggles. Even when compromise seemed to be required due to looming catastrophe abroad, often one or another group dissented and refused to go along with a majority perspective. Critical times nudged Jews to bury some of their intramural differences to cooperate, but crisis simultaneously exacerbated internal arguments when so much was at stake.

New York Jews lived at the center of American Jewish national and international politics, connecting them to key decisions, involving them in bitter debates, and allowing them to influence public affairs. As the crucial Holocaust decade from 1938 to 1948 unfolded, American Jews’ responses to the genocide of European Jews and establishment of the State of Israel took shape in the city. The Cold War against the Soviet Union, an ally of the United States during the Second World War, followed in the wake of that war, provoking attacks on Jewish political radicals, especially communists and those fellow travelers who had supported a Popular Front against fascism. Jewish political activity suffered significant travails that narrowed the range of New Deal Democrats, socialists, progressives, and radicals that had characterized New York Jews. By the mid-1950s, Jewish organizations had revamped their programs to focus on civil rights and Cold War internationalism, cleansed their memberships of Jews suspected of “subversion,” and aligned in support of Israel. A decade later, many New York Jews regrouped around a new cause consonant with the Cold War: the rescue of Soviet Jews.1

World War II

March 1937. Thousands of people made their way to Madison Square Garden, filling its seats to rally against Hitler and Nazi Germany. These men and women had disrupted their regular routines to come to the Garden in the hopes that their presence might exert some political pressure on Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who had just been elected to a second term as president. The situation for Jews in Germany continued to deteriorate with little progress made in finding homes for desperate refugees. Recognizing a common cause in opposing Nazism, the socialist Jewish Labor Committee and Zionist American Jewish Congress had joined forces to brand “Hitlerism” as “the gravest menace to peace, civilization and democracy.” To keep economic pressure on the Third Reich, they cooperated in a boycott of German products and services at the port of New York. With the help of sympathetic longshoremen and labor leaders, the boycott, initiated in 1933, also involved Jewish women who pledged not to purchase German-made goods.2

Then, in the aftermath of the 1938 November pogrom in Germany, more than twenty thousand people jammed another mass meeting at Madison Square Garden. This rally of working-class Jewish and non-Jewish organizations aimed to “protest Nazi outrages.” Side streets filled with thousands more who listened through loudspeakers. At the podium, Zionist, socialist, and communist representatives stood shoulder to shoulder calling for an end to persecutions. New York Jews’ ideological diversity—encompassing a handful of Republicans, large numbers of liberal New Deal Democrats, and voluble supporters of various iterations of socialism and Zionism as well as progressivism and communism—influenced their political posture. But in 1938, all of them opposed Nazism. This moment of unity did not endure.3

Hundreds of Jewish political, social, and religious groups, across the broadest of spectrums, maintained offices in the metropolis. Although the seat of the United States government was 250 miles away, seemingly all major deputations to influence leaders in Washington, DC, originated in New York. Jewish organizations spread within midtown across Forty-Second Street, east to west. Two major defense organizations, the American Jewish Congress and the American Jewish Committee, with often opposing approaches to Jews’ monumental problems, stood at opposite sides of this famous New York street. The American Jewish Congress, a Zionist mass-membership organization with headquarters on the West Side off Eighth Avenue, led by Rabbi Stephen S. Wise, advocated public demonstrations to draw attention to Jewish suffering. The American Jewish Committee, a bastion of elite leadership located on the East Side on Lexington Avenue, prized quiet diplomacy. However, both walked together in harmony when they received an opportunity to speak to government. Jews who set foot among the powerful, they agreed, had to do so with respect and dignity.4

The offices of the Joint Distribution Committee and the American section of the Jewish Agency for Palestine also faced each other across the street between Park and Madison Avenues. The JDC acquired renown for sending supplies to Jews in eastern Europe before, during, and after the war, but its focus on European Jews disturbed Zionists who favored directing aid to Palestine. The Jewish Agency, the pre-state Jewish government in Palestine, shared space with its most dynamic publicity arm, the American Zionist Emergency Council, and its primary fund-raising group, the United Palestine Appeal. In 1939, however, the United Palestine Appeal and the fund-raising arm of the Joint Distribution Committee joined forces, despite their differences, to establish the United Jewish Appeal (UJA). The increasingly dire situation in Europe and Palestine warranted cooperation.5

Future leaders of American Judaism’s religious movements studied in Manhattan. Rabbis and religious teachers learned at the Orthodox yeshiva Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary and its undergraduate school, Yeshiva College, in Washington Heights. Sixty blocks south, the men and women of the Jewish Theological Seminary prepared either to become Conservative rabbis or, in the women’s cases, to graduate as Hebrew teachers. Even further south stood the Jewish Institute of Religion, a liberal rabbinical school for men, led by Rabbi Stephen S. Wise.

Volunteer workers and advocates for Zionist organizations, with different strategies for how Palestinian Jews should fight for their freedom and varying visions of what sort of state Jews might create, passed one another daily on the way to their offices in the Chelsea section of Manhattan. At lunchtime, Madison Square Park served as an informal spot for unscheduled debates between supporters of the David Ben-Gurion–led Histadrut, the “umbrella framework of the Labor Zionist movement in Palestine,” and the confrontational New Zionist Organization (Revisionist), headed by Ze’ev Jabotinsky. In the critical postwar years, Histadrut supporters pleaded that the British could be convinced through diplomacy and cooperation to leave Palestine. Their interlocutors, Revisionist Zionists, sought to drive out the English through violence and intimidation. This debate continued wartime disputes between Wise’s American Jewish Congress, allied with Ben-Gurion, and Jabotinsky’s Revisionists over how to convince the United States government to rescue Jews. They disagreed over whether Roosevelt had Jewish concerns at heart. Wise believed in and trusted FDR; the Revisionists did not. If the American Jewish Congress spoke to the powerful with respect, the Revisionists—who rarely could get audiences with government—harangued and condemned, especially in the press.6

In another part of the park, Mizrachi members sermonized about the glories of a future Jewish state rising in the Land of Israel, “in the spirit of the Law of Israel.” These Religious Zionists munched on sandwiches from home or purchased at Lugee’s Kosher Restaurant nearby.7 Yet despite a shared commitment to Zionism, they differed profoundly from Labor Zionists, who rejected religion. Instead these socialists, headquartered further south near Union Square, advocated for the power of labor to transform Jews and the land itself. Identified with the kibbutz movement and other forms of collectivism, they published a lively English-language journal, Jewish Frontier, along with the Yidisher kemfer (Jewish militant), to spread their message.8

Two other groups stood even further apart ideologically, sharing little aside from a common Jewish background: communist members of the Jewish People’s Committee and the Agudath Israel, representative of Orthodox rabbinical refugees and their followers. Yet despite communists’ antinationalist ideology, during the Popular Front era, they put international revolution on the back burner. They became American and Jewish patriots eager to make common cause with Zionists and others against fascism and Nazism. The Agudath rejected the ideal of restoring Jews to their ancient homeland. Attuned to the unfolding tragedy, they dedicated themselves to saving remnants, especially pious Jewish men, rabbis and their disciples, from the Nazis’ hands. In this emphasis, they resembled the social democratic Jewish Labor Committee, which worked hard to rescue socialists, both Jewish and non-Jewish, from fascist persecution.9

As the nation’s media center, New York both disseminated information and molded public opinion. Its newspapers published terrifying news about the Holocaust as well as reports about the Jewish commonwealth in Palestine. Efforts to reach Americans began with gaining space in New York’s newspapers, weekly and monthly magazines, and radio outlets. Nine English-language dailies competed for readers in America’s information capital, from the popular tabloid the Daily News, with close to two million readers, to the staid New York Times. Borough-based organs had their own loyal subscribers. David Sarnoff’s National Broadcasting Company (NBC) operated out of Manhattan, as did its competitor, William Paley’s Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS). These two Jewish media magnates promoted both sponsored and sustaining programs as they sought to win listeners throughout the country. CBS hired Edward R. Murrow in 1935 to provide real-time news coverage, while NBC expanded the reach of AM radio. Scores of periodicals, from the newsweeklies Time and Newsweek to the photo magazines Life and Look, published out of the metropolis.10

Jewish media followed suit. The city housed the Jewish Telegraphic Agency; it fed reports to the four Yiddish dailies and a myriad of journals and Anglo-Jewish periodicals. Operatives of the Jewish Labor Committee (JLC), which before and during the war was one of the most aggressive Jewish organizations dedicated to fighting fascism and Nazism and preventing “the spread of Fascist propaganda in America,” did not have to go far to hear the most important reports. Its offices rented space downtown in the Forward Building.11

Manhattan also provided a prime venue for public Jewish protest. Rallies at Madison Square Garden, with its approximately twenty thousand seats within the main arena and room for thousands more under its famous rotunda on the street, regularly attracted press attention. In December 1940, the Jewish Labor Committee and the American Jewish Congress sponsored another mass meeting to protest Nazi conquest of eastern and western Europe. This time, they turned to Christian leaders, since communists hewed to a pacifist position, opposing U.S. involvement in World War II in line with the 1939 nonaggression pact between Germany and the Soviet Union. This rally attacked both “Nazi terrorism and Soviet aggression.” Two years later, as word of the systematic murder of European Jewry in the death camps filtered into the city, the Jewish Labor Committee, American Jewish Congress, and B’nai B’rith gathered even more solemnly to decry these murderous onslaughts. They listened to a message from President Roosevelt promising that “the American people would hold the perpetrators of these crimes accountable on the day of reckoning.”12

Dueling Jewish political organizations competed to use the power of Madison Square Garden to amplify their message. A week after the American Jewish Congress packed the Garden for a “Stop Hitler Now” rally, which beseeched FDR to rescue Jews, the Emergency Committee to Save the Jewish People of Europe took over the arena to stage a dramatic pageant titled “We Will Never Die.” For the Revisionist Zionist leader Peter Bergson and his followers, this event, which filled the Garden, represented the culmination of a yearlong media torrent designed to energize its supporters to embarrass the U.S. government into making saving European Jews a priority. Previously, the Emergency Committee had taken out full-page newspaper ads that proclaimed, “At 50$ a Piece Guaranteed Human Beings,” pleading with the Allies to ransom Jews. Now, through a cantata that the Hollywood screenwriter Ben Hecht wrote and the Broadway impresarios Moss Hart and Billy Rose directed and produced, child actors dressed as shadowy, shrouded figures, representing the doomed Jews of Europe, called out, “remember us,” to a hushed gathering. After recitation of the kaddish, memorializing the dead, attendees filed out silently as if they were leaving a cemetery.13

But any group could rent the Garden. It hosted rallies of a very different sort designed to send opposing messages to the U.S. government and people. Most disturbing, from a Jewish point of view, was the German-American Bund’s 1939 “ ‘Americanism’ rally and Washington’s Birthday celebration.” Through visual pageantry of uniformed marchers carrying flags with swastikas and the Stars and Stripes together to the podium, these American Nazis projected themselves as patriotic defenders of the United States. A crowd of twenty-two thousand heard the Bund leader recite a list of Jews whom he said controlled America, its media, and its president, all part of a Jewish conspiracy, “the driving force of Communism” in the U.S.14

May 1942. At a low point in the war, with no Allied victories in sight, Jews gathered at the Biltmore Hotel in midtown Manhattan. Six hundred delegates from every American and world Zionist organization, including Chaim Weizmann, president of the World Zionist Organization, and David Ben-Gurion, attended this Extraordinary Zionist Conference. They demanded that “the gates of Palestine be opened.” Three years had passed since the 1939 British White Paper severely limited Jewish immigration to Palestine. In anticipation of a far-from-certain Allied victory, the meeting proclaimed “that Palestine be established as a Jewish Commonwealth integrated in the structure of the new democratic world.”15

A year later, as Allied armies made gains in North Africa, hundreds of delegates from virtually every Jewish organization in the United States descended on New York’s Waldorf Astoria Hotel to attend the American Jewish Conference. By an overwhelming vote of 478 to 4, an almost unified American Jewish community agreed to prod its governmental officials and members of the international community to support a Jewish commonwealth in Palestine.16

Thus, New York Jews actively sought to rouse coreligionists and fellow citizens everywhere in the nation to Jewish suffering and advocated both rescue and a Jewish commonwealth. Almost two million strong, they stood closest to the center of home-front action. They could fill the Garden, and perhaps do more, to prove that American Jews cared about the fate of European Jewry and the destiny of Jewish Palestine.

Occasionally religious Jews took extraordinary measures to emphasize to those thousands of unaffiliated Jews just how grave the situation was during the Holocaust. In January 1941, even before Germany invaded the Soviet Union and started to murder Jews en masse, two Brooklyn Orthodox rabbis, emissaries of Agudath Israel’s Rescue Committee, drove around wealthier sections of Brooklyn on a Saturday to solicit badly needed funds. Their seeming violation of Sabbath strictures against driving was understood correctly as far from a transgression. They were acting appropriately, within the spirit and letter of Jewish law, to save lives in a critical emergency. The sight of these pious Jews in their cars on the holy Sabbath dramatized their doomed brethren’s desperate situation.17

In the autumn of 1942, a group of students at the Jewish Theological Seminary, shocked by public confirmation of the death camps and determined to do more than just attend Garden rallies, organized an Inter-Seminary Conference of Christian and Jewish Students. Meeting at the JTS, these future leaders of many faith communities called on the United States to throw open the nation’s doors to Jewish refugees who had managed to elude the Nazis and to create temporary internment camps within the United States. The students’ call for greater activism, published in Mordecai M. Kaplan’s The Reconstructionist, spurred support by the Synagogue Council of America, a national organization of rabbis and lay leaders of all Jewish religious movements. The council summoned some three thousand synagogues and Jewish schools nationwide to use the weeks between the holidays of Passover and Shavuot, days historically associated with Jewish tragedy, to observe special memorial days and partial fast periods, to raise additional funds for relief organizations, and to curtail “occasions of amusement” during this time of contemporary tragedy. Subsequently, JTS students appealed for a rabbinical march on Washington, DC. In 1943, five hundred Orthodox rabbis cried out on the steps of the Capitol.18

That year, on Washington’s birthday, the New York Jewish Education Committee conducted a “Children’s Solemn Assembly of Sorrow and Protest.” Some thirty-five hundred children, their teachers, and leaders from community Talmud Torahs, congregational schools, and Religious Zionist day schools and youth movements descended on the New York City Center in Manhattan. Through melodramatic scenes displaying grief and anger, the gathering attempted not only to deepen the students’ and their parents’ awareness of the dimensions of the Holocaust but also to enlist the sympathies of all New Yorkers. The city radio station WNYC broadcast the show to its listeners; the next day, newspaper readers saw the participants’ anguished faces. Other cities replicated this New York protest model.19

Rabbi Joseph Lookstein of Yorkville’s Kehilath Jeshurun, who presided at this impressive youth gathering, determined to sensitize his congregants to the fate of European Jewry. In April 1943, as Jews in the Warsaw Ghetto began their courageous revolt against their Nazi oppressors, Lookstein distributed black ribbons to his congregants to wear for seven weeks of mourning. He pleaded at the traditional memorial service concluding Passover for increased contributions to the recently established United Jewish Appeal. Finally he directed congregants to recite special prayers at “the close of the main meal in every home.”20

Nonetheless, activists failed to enlist consistent widespread support. Even the trumpeted Garden events occupied less than a score of nights in seven years (1938–1945). Multiple stumbling blocks prevented activist Jews from galvanizing continuous community engagement. War news of death and destruction dominated newspapers and airwaves. The unbelievable details and extent of atrocities made the unfolding genocide difficult to grasp. Fears for loved ones in military service overseas took precedence over Jewish suffering abroad. Yet a kind of callousness also seemed to exist. How else can we explain, in light of what the Germans were actually doing, publication of a spoof in Yeshiva College’s student newspaper to celebrate Purim, a feast day that commemorates Jewish escape from certain death in ancient Persia? The headline read, “Adolf Hitler Was Once Teacher Here.” A year later, all too many students still ignored the unfolding Holocaust, protected from military service by draft deferments for divinity students.21

At the Jewish Theological Seminary, its president, Rabbi Louis Finkelstein, “neither responded to direct appeals to participate in protest actions … nor involved the Seminary in any public activity about the Holocaust.” Seeking to explain his inaction, a historian has suggested that Finkelstein “did not have a clear sense that European Jewry would not be able to reconstitute itself” and “misunderstood the reasons for the Nazi assault on the Jews, blaming it on Nazi animosity for the monotheistic idea.” Yet Finkelstein, his students, and their rank-and-file counterparts at Yeshiva College could be counted among those New York Jews who were most committed to their people’s destiny.22

While the New York Times published basically “a story every other day” on the destruction of European Jewry, it never “presented the story of the persecution and extermination of the Jews in a way that highlighted its importance.” The paper resisted making “what was happening to the Jews … the lead story even when American troops liberated the Buchenwald and Dachau concentration camps.” Accounts of the “discrimination, the deportation and ultimately the destruction” of European Jews appeared on the front page only twenty-four times and never repeatedly. Editors only “intermittently editorialized about the extermination” and rarely highlighted it in the “Week in Review” or magazine sections. With Holocaust articles tucked away “on inside pages amid thirty or so other stories,” all but the most acutely aware readers “would not necessarily focus on the stories because they were not presented in a way that told them they should.”23

By contrast, from the very start of the war in September 1939, the Jewish Telegraphic Agency fed verified reports and eyewitness testimony that was consistently picked up by Yiddish dailies and not long thereafter by the English-language Jewish press. Still, even with these terrifying reports in hand, a gap remained between hearing and reading, believing and acting.24

Meanwhile, theological and political disagreements among New York–based Jewish organizations and leaders who clearly understood the dimensions of the Nazis’ murders stymied unified community-wide efforts. While thousands of schoolchildren assembled at Manhattan City Center, those who attended Brooklyn yeshivas did not. Their schools’ leaders refused to cooperate in an event that included non-Orthodox and nonreligious Jewish schools. Organizers of the gathering harbored their own political prejudices. They did not invite Revisionist Zionists because of their confrontational style. Rabbis also refused to join together in a Jewish interdenominational prayer meeting in May 1943. Rejection of Reform and Conservative rabbis took precedence over joint prayer for European Jews.25

By contrast, New York Jews knew for sure their obligations as loyal citizens. The United States demanded that they actively participate in the war effort, a commitment they enthusiastically assumed. As patriots, immediately after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, young Jewish men in the thousands signed up for military service. After the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) was organized, some Jewish women joined it. Occasionally, volunteering spawned tensions between dedicated sons and their parents, who not only feared for their safety, as all American mothers and fathers did, but also had to overcome a repugnance to army service grounded in myths of tsarist conscription. But this new generation of New York Jewish men understood that the U.S. military was an entirely different army, fighting a war that mattered immensely to Jews. While most non-Jewish soldiers enlisted eager to defeat the Japanese for their attack on Pearl Harbor, Jews in the barracks wanted to take on Hitler. On the most visceral level, they saw themselves fighting for their people and against Nazism and doing so as American Jewish men. They also recognized that their presence in the armed forces answered canards that American Jews avoided military service.26

For some Jewish men who took up arms, exigencies of the day trumped politics. One CCNY graduate, who as a left-leaning student in late 1930s had taken the Oxford Oath, reneged on that pledge never to fight in a war in order to battle a greater enemy: Nazism. Though he had a high draft lottery number and an essential home-front job, he forsook his potential exemption and was called up. Other, more doctrinaire former students, particularly some anti-Stalinist Trotskyists, who in the prewar years dominated their CCNY alcoves, bristled at these transformations. Irving Howe considered the war “the literal last convulsions of capitalist interminable warfare,” he wrote; “both sides fight for the retention of their reactionary status quo.” Howe penned these and other words against FDR, Churchill, Hitler, and Stalin for Labor Action while serving as a private first class, stationed in Alaska.27

Once in the army, Jewish soldiers received support from their families and communities, as did most GIs. New York Jewish delis urged Jewish parents, “send a salami to your boy in the army.” Such packages gave their boys a taste of home. Army rations did not include kosher food; pork was a popular source of daily protein. Even many Jews who did not particularly keep kosher disdained eating ham.28

New York Jews on the home front participated enthusiastically in neighborhood war drives. They bought war bonds, gave blood, rolled bandages, collected scrap metals, organized block observances memorializing those who had fallen, and attended first-aid and civilian-defense activities. Local Jewish organizations used patriotic naming opportunities to raise funds for the United States and demonstrate their engagement in the war effort. Five days after Treasury Secretary Henry W. Morgenthau called on all New Yorkers to “start digging down into their pockets” to raise billions for the war-bond drive, a chapter of the American Jewish Congress in the Bronx contributed its first $5,000 toward financing “a bomber bearing the name ‘The American Jewish Congress.’ ” In the Syrian Jewish community of Bensonhurst, members of its Magen David congregation demonstrated their loyalty by raising $300,000 for a two-engine B-25 Mitchell bomber named “Spirit of Magen David.”29

Jews also challenged fellow Jews to avoid exploitation of wartime shortages. During Passover of 1943, peak season for kosher-meat sales, 150 Bronx kosher poultry retailers joined a “selling strike” designed “to force wholesalers into lower price levels.” They closed their stores for three days to demand prices be pegged in accord with Office of Price Administration (OPA) regulations, which monitored rationing of consumer goods during the war.30

Brooklyn’s insular Syrian Jewish community demonstrated unwavering patriotism in support of its young men in uniform. The war empowered a group of women to stay connected to their soldiers, relieving homesickness. They created a newsletter, The Victory Bulletin, which shared events at home with roughly one thousand Syrian Jews in uniform both stateside and overseas. Many of these young women discovered the transforming effect of their activism, perhaps “equal in impact to that of the boys who went off to fight a global war.” These activists broke out of long-standing passive female roles and assumed leadership positions to a degree previously unseen within this traditional Jewish community.31

A consciousness of becoming American permeated diverse communities of Jewish New Yorkers during the war. Victory Bulletin editorials reminded readers of their ongoing obligations as patriotic Americans to show unquestioning support for the war effort. Through all the twists and turns in the priorities and conduct of the war, The Victory Bulletin expressed only total support for FDR. When it came to controversial war policies, like when and where to open a “second front”—an allied invasion in western Europe to complement the Soviet Union’s titanic struggle with Germany from the east—The Victory Bulletin instructed its readers to write to Roosevelt and tell him, “I am behind you in your efforts.” The one article that explicitly discussed the verified reports about the murder of Jews under Hitler criticized neither FDR nor his subordinates. But it did pillory the Red Cross for its failure to “utilize their financial resources and power to their utmost.” It also called on the Allied nations “to threaten a terrible vengeance should such a crime”—the murder of an estimated four million additional Jews—“be perpetrated.” The editors did not call for extraordinary measures to rescue doomed Jews.32

The Syrian community’s unwavering support for the president paralleled the sentiments of most New York Jews. Although Peter Bergson’s group of Palestinian Jewish activists and American supporters relentlessly criticized FDR, they remained an outspoken minority. When the president died, New York Jews mourned. Many had only known one president: Roosevelt. Rabbi Wise eulogized him as “a beloved and immortal figure,” who “felt the misery of the Jewish people in Europe” with “compassion.”33

New York Jews had joined Roosevelt’s bandwagon in the late 1920s, helping to elect him governor. Gradually they entered the Democratic political column and became loyal members of an emerging urban coalition of ethnic minorities that backed candidates who favored social welfare legislation. Many understood their politics as congruent with normative, American ways of acting, even as they continued to favor policies championed by neighborhood socialists. Support for FDR spiked after passage of New Deal legislation designed to help working men and women. Roosevelt appointed unprecedented numbers of Jews to high administrative offices. Jews commended his courage, especially since their presence in government provided grist to anti-Semites who charged that “Jew Deal” operatives controlled Washington.34

Eventually even committed socialists lined up with FDR. Abraham Cahan’s appeal to his comrades to “give up their theories and back Roosevelt’s specific polices” resonated in the streets and at the ballot boxes. Beginning in 1936, those who refused to vote the Tammany party ticket could support FDR on the new American Labor Party (ALP) line. New York garment-union leaders established this so-called Jewish third party to strengthen their political clout and garner moderate left-wing backing for FDR at the same time as they drew Jewish votes away from the socialists. In 1936, the ALP contributed nearly a quarter of a million votes for Roosevelt—a substantial component of the 90 percent of New York Jewish votes for FDR—and for the Jewish Democrat Herbert Lehman, who was running for governor. By the 1944 election, the ALP captured within one heavily Jewish Bronx neighborhood some 40 percent of the vote. Many socialists and communists eventually joined the ALP, with only a handful, along with a staunch minority of Republicans, standing apart from this Jewish political alliance with the White House.35

Yet their wartime anxieties as Americans and Jews did not erase desires to live as normally as possible under the circumstances. Trying concerns—worries about family, fear over what was really happening to Jews in Europe, struggles to cope with consumer deprivations, demonstrations of their loyalty to the United States and eagerness to trust Roosevelt—coexisted with mundane daily realities. In extraordinary times, New York Jews also lived ordinary lives, displaying a mixed set of priorities that balanced wartime apprehensions with local needs. Ambiguities of communal life—conflicting priorities of commitment to Jewish rescue and realties of an American war together with a desire to maintain institutional equilibrium—surfaced among many Jewish religious organizations.36

A rabbi like Lookstein might plead for his congregants to remember Jewish suffering abroad, but such exhortations did not cast a mournful pall on synagogue life. At Kehilath Jeshurun, for example, its “Annual Smoker” for men went off as scheduled in January 1944, despite Lookstein’s pleas. The next night, couples attended “a sellout” theater party on Broadway. Such events, not to mention the congregation’s annual dinner, followed guidelines that the synagogue’s president had articulated back in 1941. As the congregation made plans to celebrate its seventieth anniversary, its president asserted, “our common prayer should be that neither personal sorrow nor universal hardship may mar our proposed celebration and that it may be observed amidst a world enjoying the blessings of peace.”37

Given a decidedly mixed record of Jewish congregational activity during wartime, most New York Jews who did not affiliate with a synagogue similarly behaved in normal ways. During World War II, Sylvia and Jack Goldberg harbored no strong Jewish organizational ties. Perhaps their story of how they coped, more than the saga of activists and those who had conflicting communal priorities, exemplified a quintessential New York Jewish home-front narrative. Living in the Bronx, their local religious involvement consisted of Jack’s accompanying his wife’s stepfather on the High Holidays to one of the older Orthodox synagogues in the neighborhood. In thinking about those days more than half a century later, Sylvia insisted that they “had absolutely no idea” about the Holocaust. “The press did not write about it, and we read the papers every day.” Nor were they aware in retrospect of the public protests by Wise or Bergson. Their issue was not even the war effort, although they surely were patriotic. Rather, they wanted Sylvia to live a normal life raising their infant child, while Jack, drafted in 1943, served in England and then in France and Germany with the Third Army. He did not see his daughter until he was discharged in 1945.38

Sylvia lived rent-free with her mother and participated in an informal support circle of eight Jewish couples from the neighborhood. In addition to keeping daily tabs on each other while three of the husbands were in the service, they met monthly, as they had done before the war, at each other’s homes. Their friendship had blossomed in the 1930s on the handball courts of the Castle Hill Pool, a blue-collar Jewish swim and sports club. Occasionally, they went to the Catskills for a weekend of rest and recreation. It helped them to cope with their daily cares and floating anxieties about their loved ones at war. They obtained a group discount by calling themselves “The Sylvia Goldberg Association,” since Sylvia made the reservations. Comfortable in this upstate, bucolic Jewish space, as they ate to their hearts’ content from an extensive menu of Jewish delicacies, they temporarily put their cares behind them and did not worry about the fate of their loved ones in uniform. Yet they remained conscious of how they had found personal normalcy during extenuating times. One woman took home a hotel dinner menu as a souvenir and commented with a mix of amazement and irony, “Would you believe this is war time?”39

Cold War

It seemed that no sooner had the Japanese surrendered and the millions of soldiers shipped back stateside than a new wartime footing emerged. The Cold War that took hold following World War II between the United States and the Soviet Union encouraged New York Jews to align themselves against the Soviet Union and adopt an anticommunist position. But for a brief moment in 1947, as the United Nations voted to partition Palestine into Jewish and Arab states, both the Soviet Union and the United States landed on the same page. Their support for the new State of Israel, established in May 1948, allowed Zionists and communists, socialists and capitalists, to coalesce into a single outpouring of enthusiasm for the beleaguered Jewish state. Such unanimity was short-lived. The 1948 presidential campaign fractured that unity, as New York Jews split their votes between the Democratic Party nominee, President Harry Truman, and the Progressive Party’s standard-bearer, former vice president Henry Wallace, with a handful of Republicans voting for New York Governor Thomas Dewey. Yet by the 1950s, despite the Cold War, New York Jews increasingly integrated support for Israel and consumption of Israeli culture into their lives. Subsequently the Cold War facilitated a decision to embrace a decades-long campaign to speak out on behalf of Soviet Jews and to rescue them from an anti-Semitic government. A generation of New York Jews growing up in the postwar decades determined to enlist in a new Jewish cause that would rectify the scales of history. Some claimed to learn from what they understood as their parents’ failures to save European Jews, while others challenged decisions made by members of what came to be called “the greatest generation.”

The Holocaust cast a long shadow over New York Jewish politics. It shook up committed socialists, like Irving Howe, who had seen no difference during the war between Churchill and Hitler, Stalin and FDR. Nazism’s branding of Jews as a race galvanized men and women to oppose discrimination in New York on the grounds of race, religion, and national origin. Jewish defense organizations revamped their programs. But the rise of a new anticommunist movement, identified with Senator Joseph McCarthy of Wisconsin, complicated New York Jewish politics. In 1948, many New York Jews, especially in the Bronx, had voted for Henry Wallace and his Progressive Party. With McCarthyism sweeping the country, New York Jews wrestled with their own, more intimate question of where they stood on communism and the Soviet Union. Watching “the trial of the century” unfold in Manhattan, they furiously debated the political issues swirling around the defendants, Ethel and Julius Rosenberg, arrested in 1951 for conspiracy to commit espionage.40

Although the charge was conspiracy, most observers thought of this Jewish couple, convicted based on the testimony of other Jews, as atomic spies. The drama of their trial, played out before a Jewish judge, with dueling Jewish prosecutors and defense attorneys, seemed to implicate all New York Jews. The trial pitted Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, both born and bred on the Lower East Side, children of struggling Jewish immigrants, against an ambitious, young assistant prosecuting attorney who grew up on the Grand Concourse before moving to Park Avenue. They stood before another Jew, a “boy judge” who aimed for respectability. The trial’s drama presented a stark choice for Jews: “between those who had made it and those who still struggled on the edge of poverty, between the values of Park Avenue and those of the Lower East Side, between a religious Jewish identity and a secular radical one, between those clothed in the power of the state and those who wore only their own ideology.” When the jury agreed that Julius had served as a spy for the Soviet Union, recruiting Ethel’s younger brother, David Greenglass, and had been helped by Ethel, who appears to have been framed by the FBI with her brother’s assistance, the judge sentenced them to death. He accused them of “devoting themselves to the Russian ideology of denial of God, denial of the sanctity of the individual and aggression against free men everywhere instead of serving the cause of liberty and freedom.”41

In the two years of appeals preceding the Rosenbergs’ execution, neither side wavered. The Rosenbergs asked for justice, not mercy. The judge replied, “I consider your crime worse than murder.” Subsequent appeals were rejected. The outbreak of the Korean War further inflamed passions, as did McCarthyism, which endangered so many left-wing Jews with loss of their livelihoods through blacklists and loyalty oaths, investigating committees, and prosecutions. The Rosenberg case threatened to implicate a significant segment of New York Jews and their synthesis of political radicalism with Jewish ethnicity.42

The Rosenbergs’ execution occurred on a Friday evening in June 1953, as hundreds of New Yorkers gathered in Union Square in a silent vigil. The Jewish communist novelist Howard Fast took the microphone to announce that there was no more hope for reprieve. When Fast proclaimed that Julius Rosenberg was dead, “tears and sobs seized the crowd.” A teenager later recalled, “We had stood there, silently, from late afternoon until that moment thinking that against all odds our presence might somehow persuade President Eisenhower to grant executive clemency.” It was not to be. Yet in other parts of the city, where Jews mingled with their Italian American neighbors on Brooklyn streets, cheers greeted news of the couples’ deaths, broadcast live from Sing Sing prison. An enormous burden on New York Jews had been lifted.43

The Rosenbergs’ execution, coupled with difficulties defending a position that was neither communist nor liberal in an environment dominated by McCarthyism, contributed to the decision of a number of left-leaning Jewish intellectuals, including graduates of CCNY’s alcoves like Irving Howe, German refugee scholars like Lewis Coser, and Ivy League–educated writers like Norman Mailer, to launch a new magazine, Dissent. Although the American Jewish Committee had underwritten the new Jewish intellectual magazine Commentary after World War II, its perspectives tended to support U.S. Cold War policy. Dissent and Commentary shared many writers, part of a circle of New York intellectuals, many of whom lived on the Upper West Side, increasingly an ethnically and socioeconomically diverse neighborhood. Both magazines attracted a mix of Jewish and non-Jewish men and a few women (especially once the feminist movement arrived) who sought to shape American political life. However, Dissent, lacking any Jewish organizational support, regularly critiqued United States politics from a democratic socialist position. It challenged the bureaucratization of American life, addressed rampant socioeconomic inequalities, and mounted substantial cultural criticism against bland, middle-brow culture, while publishing avant-garde writers. Its cultural criticism at times overlapped with The Village Voice, a weekly alternative paper that regularly published many New York Jewish columnists.44

A number of these men, “New York Intellectuals,” had considered themselves in their college days to be “citizens of the world,” cosmopolitans who set themselves apart from parochial sympathies and patriotic American realities. In the postwar years, their consciences raised by communist aggression, by Soviet anti-Semitism, and most profoundly by the horrors of the Holocaust that reminded them of their Jewish backgrounds, they refashioned themselves as self-conscious Jews. Living together on the “Upper West Side kibbutz,” as they jokingly referred to the neighborhood, a number of them, including Daniel Bell, Nathan Glazer, and Irving Kristol, met regularly with their wives to study Talmud and Maimonides’s Mishneh Torah. They wrote for a cluster of new journals that appeared after the war, including Dissent and Commentary, as well as two influential quarterlies, Judaism and Midstream (a Zionist publication). A few of these intellectuals, notably Kristol, transformed into Cold Warriors and, using Commentary and other magazines to its political right, influenced the rise of American neoconservatism.45

Aside from sharing a neighborhood and a passionate commitment to politics and intellectual debate, many New York Jewish intellectuals admired the new Jewish state. Their fierce arguments prior to May 1948 on whether a state should be established faded in the face of Israel’s war against Arab nations. Israel’s socialist leadership, its kibbutz experiment, its extraordinary effort to gather in displaced European Jews who had survived the war and to absorb Jews from Arab lands who fled persecution all elicited approbation. However, popular efforts to glorify Israel, such as Leon Uris’s best-selling novel Exodus, provoked disdain for its “pro-Israel sentimentality.”46

Enthusiasm for Israel extended beyond intellectuals to increasingly wide circles of New York Jews, who gave generously to the United Jewish Appeal’s annual campaigns for financial support. In 1948, the campaign raised unprecedented sums that produced private worries among New York Jewish Federation leaders about such formidable competition for funds. Gradually, New York Jews integrated consciousness of Israel into their urban culture. Synagogues added the Israeli flag to the American one, flanking the ark or bima (platform); Jewish events often began with singing the Israeli national anthem. An organization like the 92nd Street YMHA encouraged Israeli dancing as it shifted away from Americanization activities. Its regular weekly sessions, which combined teaching new dances with old favorites, drew participants from around the city. Once a year, beginning in 1952, troupes from diverse venues converged on Hunter College for the annual Israeli folk-dance festival. It subsequently grew so big that it shifted to larger quarters at Carnegie Hall.47

By the 1960s, New York City enabled sustained advocacy for Jews trapped in the Soviet Union. More than ever, New York assumed visibility as an international media capital, even as it continued as the country’s Jewish capital city. It also harbored the United Nations, only blocks from midtown Jewish organizational headquarters. The fight for Soviet Jewry ultimately ended in victory, with close to a quarter million settling in New York. Many of those who chose the United States over Israel in the 1970s and 1980s were not Zionists. Their choice to seek America’s promises rankled Israeli officials who had been the first to fight for their right to emigrate, albeit often behind the scenes. Subsequently, the dissolution of the Soviet Union sent well over a million Jews and family members to Israel because the U.S. no longer considered them refugees.48

Although the struggle to rescue Soviet Jews occurred in the city, conflicts over tactics often reverberated with debates over how best to address Jewish crises. Recriminations over what Jewish “establishment” as opposed to “grassroots” leaders did, or did not do, during the Holocaust fueled these arguments. Such designations as “establishment” and “grassroots” were redolent with meaning and passion. Divergent views of the world from headquarters versus neighborhoods loomed large, even if everyone shouted, “Never Again.”49

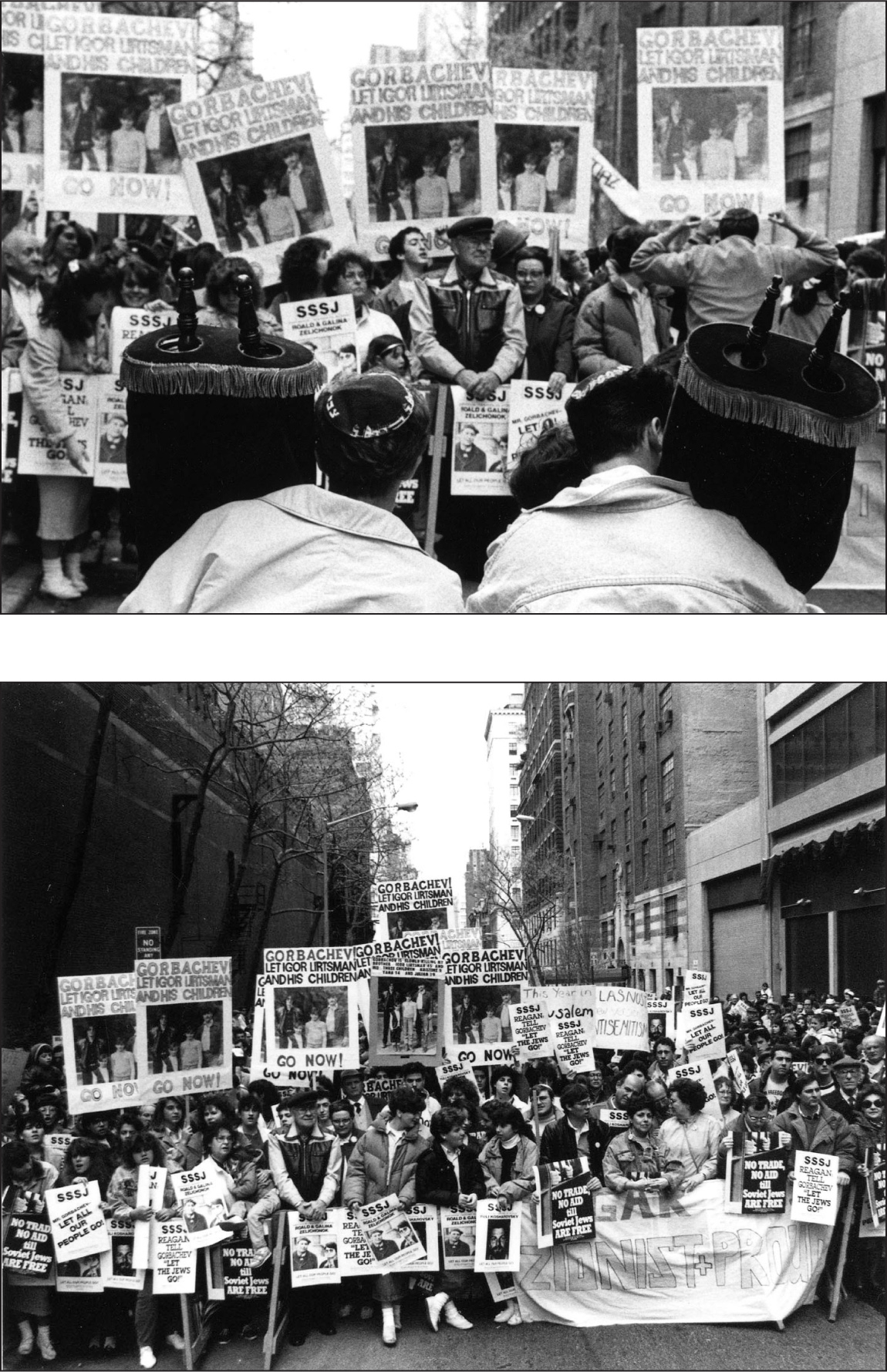

The Soviet Jewry movement also recruited a younger generation. Jacob Birnbaum (1926–2014) arrived in New York armed with a vision of how to attack the Soviets and free Soviet Jews. This cause became his life’s work. Born in Hamburg, Germany, to a distinguished family of Yiddishists, he escaped to Britain on a Kindertransport. After the war, he moved to France to help survivors. When he came to New York City at age thirty-eight, he imagined a mass movement, a “tidal wave of public opinion,” that would take the message of freedom to the streets, making the enemy decidedly uncomfortable through unfavorable publicity. Bearded and balding, wearing a black yarmulke, he planned to recruit his shock troops among Jewish students in the city. Living a few blocks from Yeshiva College, he found young Orthodox men and women ready to fulfill the religious obligation of “freeing captives.” Birnbaum also reached Jewish students at Columbia University, where he founded the Student Struggle for Soviet Jewry (SSSJ). On May Day 1964, the group organized its first protest rally and picketed the Soviet UN mission. SSSJ appeared repeatedly at the United Nations. Its protest themes melded Jewish historical and religious imagery with contemporary political objectives, as demonstrations enacted Jewish identification. A Passover “Night of Watching” linked Soviet Jews with the Israelite Exodus from Egypt.50

Student Struggle for Soviet Jewry, Freedom Day Rally at the Soviet UN mission, May 1, 1988, by Abraham Kantor. New York City housed the United Nations and also served as America’s media center. This combination amplified the voices of New York Jews when they rallied to rescue Soviet Jews. The movement regularly recruited young Jews. In the 1970s, many were veterans of 1960s protest movements (such as the civil rights movement and antiwar movement). Courtesy of Judith Cantor, Student Struggle for Soviet Jewry Records, Yeshiva University Archives, New York.

Birnbaum’s tactics resonated with Jewish college students, veterans of contemporary American protest movements. A full half of SSSJ members had been involved in anti–Vietnam War movements, while more than a quarter had fought for civil rights. Jewish engagement with civil rights involved both efforts to dismantle discrimination in college admissions, employment, and housing in New York and participation in efforts to integrate schools, public transportation, restaurants, and hotels in southern states. Protests against the Vietnam War took Jewish students out into the city’s streets, where they occasionally encountered counterprotests from supporters of the president and America’s involvement in Vietnam.51

Meir Kahane (1932–1990) and his Jewish Defense League (JDL) similarly despised the establishment. But Kahane also deemed nonviolent confrontations to be weak-kneed and “dangerous” because they provided “a false sense of activism.” While in JDL’s ongoing battles with New York’s black militants, members only threatened to use any means available to them, when it came to harassing Russians living in the city, they fought both within and without the law. JDL derived from the Holocaust the “lesson” that Jews stood alone and that those who were content just to “hold rallies and mimeograph sheets of paper” would “doom” Soviet Jewry. Seeing themselves as struggling against the world and shamefully wrongheaded Jewish leaders, JDL members rejected respectability. They pledged “to do what must be done” so that the U.S. would have no alternative but to demand justice for Jews.52

With the crisis of Soviet Jews increasingly in the headlines, a new National Conference on Soviet Jewry (NCSJ) obtained Jewish communal funding along with its cooperating organization, the Greater New York Conference on Soviet Jewry (GNYCSJ). These organizations quickly “assumed the posture of the Student Struggle emphasizing mass demonstrations.” The JDL also influenced their militancy. These new organizations feared leaving the field of protest to the lawless Kahane. But this turn did not augur a unified front among nonviolent advocates.53

Still, Solidarity Sunday, an annual event started in 1971, exemplified a community engaged in nonviolent protest. It attracted up to one hundred thousand marchers down Manhattan’s Fifth Avenue to the UN. Beyond proving the people power of New York Jews with numbers that activists had dreamed of for generations, Solidarity Sunday also intensified the Jewish identities of many who participated. Those who stood in the streets, wearing bracelets bearing the names of oppressed Soviet Jews and carrying signs that called for their release and emigration, experienced the day as a secularized holy moment.54

JDL redoubled its militancy. It attacked Soviet newspaper and tourist outlets in New York and disrupted performances of Russian cultural troupes. It took to firing shots into the Soviet UN mission. Most egregiously, it bombed the offices of Sol Hurok Productions in Manhattan, killing a Jewish employee and injuring fourteen others. Hurok, a Jewish impresario, had gotten his start in Brownsville’s Labor Lyceum and worked to help Soviet artists appear in the United States, using cultural exchange to overcome Cold War antagonisms. Seemingly, Kahane answered to no one except the police and the FBI, which monitored his activities. But actually, Lubavitcher Hasidic leaders along with Manhattan-based Jewish establishment opponents harshly called him to task. The former feared that his protests would undermine their own clandestine efforts to smuggle Jewish religious articles into Russia and to spirit Jews out of the Soviet Union. These Orthodox diplomats shared common tactics with Manhattan Jewish leaders.55

Jewish efforts on behalf of Soviet Jews fit comfortably within U.S. Cold War culture. In 1972, Senator Henry Jackson proposed a bill to tie release of Soviet Jews to Moscow’s desire to be accorded “most favored nation” status. The Jackson-Vanik amendment stipulated that the Soviets would be denied specific trade and credit benefits unless they agreed to release annually large numbers of Jews—the target number became sixty thousand—and to end harassment of both politically outspoken dissenters and Jews who wanted to leave the Soviet Union. All groups of New York Jews involved in advocacy for Soviet Jews supported the legislation. However, when it became law in 1975, these organizations again diverged, some favoring protest and others opposed.56

Activists on behalf of Soviet Jewry achieved impressive victories within their organizers’ lifetimes. They also provoked antagonisms and exacerbated divisions separating New York Jews. But just as the movement drew on the city’s unique geography, its neighborhoods that clustered Jews according to class, religion, and politics, so did New York Jews’ experiences resound beyond the city’s boundaries. Despite inroads of suburbanization and diminution of New York City’s Jewish population, its over a million Jews in the 1970s and 1980s still sustained sufficient diversity to fuel activist dreams, create communities of solidarity, and transform promises into realities.