Chapter 6

![]()

From Brown to Brown: Sixty-Plus Years of Separately Unequal Public Education

Kimberly Jade Norwood

“Do you know how hard it was for me to get him to stay in school and graduate? You know how many Black men graduate?”

—Lesley McSpadden, Michael Brown’s mother1

On August 9, 2014, Michael Brown, an 18-year-old Black teenager, was killed by police officer Darren Wilson. Brown had just graduated from a public high school in the Normandy School District (Normandy Schools) located in Normandy, Missouri. He was scheduled to attend a for-profit college in Missouri a few days after his death.2 For all of his life, Normandy Schools were predominately Black, poor, and in academic distress. Take away the year 2014 and leave the words Brown, education, and segregation, and one would immediately think of a different time: the 1950s. One of the most famous decisions in U.S. Supreme Court history, Brown v. Board of Education,3 decided in 1954, outlawed segregated and unequal education. Over 60 years later, the battle for integrated, quality education continues. This chapter examines the school district Michael Brown graduated from and situates its place in the Brown legacy.

A Segregated and Unequal Past

Unequal access to education for Black Americans began long before Brown. Almost from the beginning of African enslavement in this country through the end of the Civil War, laws existed in most of the colonies, and later the states, making it a crime to teach Blacks (in some cases whether enslaved or free) how to read or write.4 With the Civil War’s end and the beginning of Reconstruction in 1865, strong demands to overturn those laws and a positive movement toward obtaining a quality education became one of the first priorities for Blacks in America.5 Freedom from bondage, citizenship, and the right to vote were eventually secured by the ratification of the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments. These gains were believed (and hoped) to be the beginning of the end of a 200-plus-year nightmare.6 The post-Reconstruction era, however, saw the legalization of racial segregation as evidenced by the Supreme Court’s holding in Plessy v. Ferguson that a standard of separate but equal was constitutional.7 The decision in Plessy, combined with other laws in the nation at the time (e.g., peonage and convict lease laws) and the continued and escalating violence waged by the Ku Klux Klan, all worked to ensure that separate would not be equal.8

The collective Black community overwhelmingly believed, however, that education was the key to real freedom. Formerly enslaved Blacks were often mutilated and even killed if caught trying to learn how to read and write.9 Both during Reconstruction, with the help of the Freedmen’s Bureau—and thereafter once the Bureau was disbanded—these formerly enslaved people spent virtually all of their money to build schools and to obtain an education.10 Although the right to an education was secured in many states, the quality of the education varied depending on the color of one’s skin. Charles Hamilton Houston, born one year before Plessy, dedicated his life to changing that outcome. Using public education as his foundation, Houston proved, in cases spanning a 20-year period, that separate was not equal in the field of public education.11 Though Houston did not live to see the culmination of his work in Brown, his protégé, Thurgood Marshall Jr., secured a unanimous Supreme Court vote completely accepting Houston’s philosophy that segregation based on race was not, and could never be, equal.12

Following Brown’s announcement, and its second opinion a year later famously directing the nation to desegregate its schools with “all deliberate speed,”13 there was tremendous pushback against the ruling, particularly in the South.14 For two decades though, Supreme Court decisions suggested that integration was here to stay.15 But White backlash was steadfast. Encouraged by racially discriminatory policies enacted by private banks, realtors, and even the federal and state governments, Whites fled urban areas as Blacks moved in.16 Urban school districts soon found very few Whites left in the cities with which to desegregate.17 One district court in Michigan found its answer by allowing children to cross school district boundaries lines in order to desegregate schools. After finding that it was not enough that the State violated the constitution, the Supreme Court found that individual school districts, too, must be in violation of the constitution in order to be included in any remedy; in the case at hand, then, the crossing of school boundary lines was rejected.18 This was the Court’s first retreat from Brown. Over the next 20 years, the Court issued multiple opinions that virtually halted judicial efforts to undo hundreds of years of unequal and segregated education.19 This occurred despite evidence that schools were not, in fact, being desegregated, much less integrated. Indeed, the Court held in 1991 that desegregation was no longer the goal. Rather, if a school could prove that it had acted in good faith to do what it could, “to the extent practicable,” to desegregate, that was all that was required.20 In 2007, the Court again revisited desegregation in public schools. In that year, the Court decided Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District No. 1.21 There the Court applied the most demanding constitutional standard, that is, the strict scrutiny test, to the question of whether race could be used by school districts to voluntarily desegregate schools. Answering no, the Court found that the use of race failed the second prong of the strict scrutiny test in the cases before it: the use of race was not narrowly tailored to achieve a compelling governmental interest.22

Racial Inequality in Public Schools

Segregated and unequal schools thrive throughout the United States.23 Brown’s vision of both integrated and quality education for all students has been lost and indeed may be impossible to fulfill in the 21st century. Under racially segregated systems pre-Brown, most Black students were not receiving quality education; most White students were. Brown envisioned that if the students were desegregated and assigned to schools without regard to the color of one’s skin, not only would the goal of integration be met—which many believe in and of itself is a form of education—but also that all students would receive a quality education. Quality education in an integrated setting was possible in the decades following Brown, but this dual goal is no longer possible. It is not simply that public schools today are more racially segregated than 40 years ago, although this is true.24 And it is not simply that Black, Asian, and non-White people of Latin American descent make up a majority of the students in public schools today (thus the term “majority minority”), although this is also true.25 But, we must consider two other key factors: (1) White student enrollment in public schools has decreased over the years and (2) White births have declined significantly over the years.26 All of these realities challenge any goal to integrate schools as that term was defined in Brown.

Notwithstanding the challenges facing racial integration of schools today, we must not abandon the other goal of Brown: that all children, no matter their skin color, receive access to quality education. This is really what Brown stood for. Brown viewed education as the mechanism to enable full citizenship in American society.27 Indeed, Brown specifically acknowledged that without an education, it is virtually impossible to execute the rights of citizenship.28 And yet, today, for millions, this goal has also been largely abandoned.

Public schools in the United States have been falling and failing for many years.29 They have also become more unequal in terms of the quality of education and this can be racially tracked. Black, non-White Hispanic students, and American Indian/Alaska Native or Native American students are at the greatest academic disadvantage as compared to non-Hispanic White/Caucasian students and Asian/Pacific Islander students.30 Blacks, and Black males in particular, are at the bottom of the academic ladder. Consider the following:31

Graduation

The national public school graduation rate for Black males in 2012–2013 was 59 percent. The percentage was 80 percent for White males. Worse still, the graduation rates for Black males in large urban school districts during that same period were far lower. Missouri’s graduation rate for Black males in 2012–2013, for example, was 66 percent. Yet, for its largest urban school district, St. Louis Public School District (SLPSD), the graduation rate for this subgroup was 33 percent. These results were not unique to St. Louis. Atlanta graduated 38 percent of Black males; Cleveland, 28 percent; Detroit, 20 percent; Miami, 38 percent; New York, 28 percent; Philadelphia, 24 percent; and Milwaukee, 43 percent.32 The announcement in 2015 by the Department of Education that U.S. students are graduating from high school at rates higher than ever before33 rings hollow for some.

Literacy

Graduation is undoubtedly important but literacy is even more so. Indeed, one can graduate from high school but be unable to read.34 Large achievement gaps exist between Black and Latino student performance and that of White and Asian students.35 Of all subgroups, Black males are at the bottom of all performance levels.

The National Assessment of Education Progress (NAEP) has three academic achievement levels: Basic, Proficient, and Advanced.36 NAEP’s performance data reveals huge racial disparities. For example, in the 2012–2013 school year, the national percentage of Black males who scored at proficient or above in 8th-grade reading was 12 percent. The same figure for White males was 38 percent. For 8th-grade mathematics, the national figure for Black males in 2012–2013 was 13 percent at or above proficiency, compared to 45 percent for White males.37

Although NAEP tracks three achievement levels, many states add a fourth level: below basic (or level 1). This level is below grade level.38 In New York State, for example, 2014 English Language Arts assessments for grades 3–8 showed that 46 percent of Black students scored below basic, compared to 25 percent of White students; in mathematics, the figures were 47 percent and 21 percent respectively.39 In the nation’s capital, 15 percent of Black students in 8th grade performed below basic in both reading and math categories as compared to 1 percent of White students.40 In some of these Washington, D.C., school districts, the below basic percentage of Black students was as high as 61 percent for 8th-grade reading and 59 percent for 8th-grade math.41

Resources

If you compare schools where the student body is predominately Black and Latino to schools where the student body is overwhelmingly White and Asian, it is immediately apparent that a different type of education is taking place in each space.42 In October of 2014, the Department of Education, Office of Civil Rights Division (OCR), issued a report demonstrating the different educational experiences of children depending on the racial makeup of their school. A sample of some of the findings contained therein revealed that schools attended by predominately Black and/or non-White Hispanic students

- were less likely to offer advanced and/or gifted courses and where offered, the students were less likely to be recommended to or enrolled in those classes.

- were less likely, at least in the case of predominately Black schools, to offer Advanced Placement (AP) courses.

- had newer, more inexperienced teachers.

- had teachers who made less money than similarly credentialed teachers in predominantly White school districts.

- were older and poorly maintained, with inadequate heating, ventilation, air conditioning, and lighting.

- were more likely to be overcrowded and lack essential educational facilities like science laboratories, auditoriums, and athletic fields.

- had fewer computers and other mobile devices and computers were of lower quality and capability; indeed, even the speed of Internet access varied.

These disparities were not limited to a simple comparison of inner-city and poor schools with wealthier suburban schools. Rather, even for schools in the same school district, schools with primarily White populations were shown to have more and better resources.43 Michael Brown attended what are sometimes referred to as ‘apartheid schools,’ schools whose students are almost all Black and/or non-White Hispanic, and often usually poor.44 These schools struggle in every way and at every level imaginable. As demonstrated below, Michael Brown attended one of these schools.

Normandy Schools

Michael Brown attended schools located in Normandy, Missouri. Incorporated in 1945, Normandy was originally a White suburb of St. Louis City. As Blacks started moving into Normandy and other similar suburbs near St. Louis city, Whites fled.45 By 1978, Normandy Schools had the second-highest percentage of Black students in the St. Louis metropolitan area. SLPSD had—and still has—the highest percentage in the area.46

Born in 1996, Michael Brown started kindergarten in a district that had not been “accredited” since 1991.47 The Missouri Department of Elementary and Secondary Education (DESE) is required by law to annually review school performance to evaluate which schools (and students) need improvement.48 DESE follows an accountability system for reviewing schools. The system “outlines the expectations for student achievement with the ultimate goal of each student graduating ready for success in college and careers.”49 DESE considers various standards in attempts to determine if a school is on target to achieve its goal. Based on evaluation of these standards, a district can be unaccredited, provisionally accredited, accredited, or accredited with distinction. A 14-point scale was used (this system has since been replaced) to evaluate the effectiveness of school districts. A minimum of 6 points were required for accreditation.50 During Michael Brown’s tenure in the district, Normandy Schools never received more than 5 points.51 Normandy Schools were not labeled as unaccredited during this time, as they should have been, but were allowed to operate as a provisionally accredited district. Though the district was finally, oficially labeled as unaccredited in 2013, the lengthy stay as provisionally accredited prevented the type of attention and focus on the district and on the children in that district that it surely needed.

To add insult to this injury, in 2009 DESE took another all-Black, poor, and unaccredited district, the Wellston School District (Wellston)—which was then the worst performing district in the state—dissolved it, and placed all of its students in technically-unaccredited-but-nonetheless-labeled-provisionally-accredited Normandy Schools.52

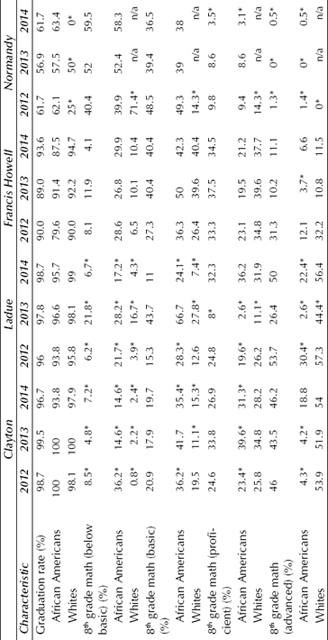

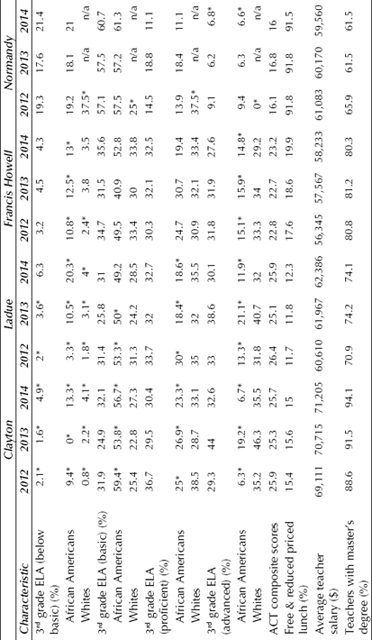

Serious questions remain as to why DESE placed students from Wellston into the struggling Normandy Schools. Granted, Normandy Schools were in close proximity to Wellston, but nothing required Wellston students to be placed in the district closest to them.53 More importantly, given that Normandy Schools were, for all intents and purposes, technically unaccredited, it was a horrible choice. Indeed, there were two accredited districts near Wellston where those children could have been assigned. Those two districts, the Clayton School District (Clayton) and the Ladue School District (Ladue), were 3.2 miles and 7.6 miles away respectively, from Normandy Schools. (See Figure 1.) Not only were these two districts close to Normandy Schools and accredited but they were actually very high-performing districts. (See Appendix.) As the data in the Appendix reveals, both Clayton and Ladue outperformed Normandy Schools academically in all categories. The Wellston children could have easily been reassigned to schools in Clayton and Ladue, thus avoiding the unneeded pressure on the already frail Normandy Schools.

But DESE did not assign the Wellston children into these higher-performing districts. Many believe race and class were the underlying reasons. Clayton and Ladue are both affluent and virtually all-White school districts. Wellston and Normandy Schools both were then predominately Black, poor, and academically struggling. Missouri Board of Education Vice President Michael Jones said it best: “The [Wellston] students were not going to be absorbed into any of the high-performing, mostly White districts nearby. You’d have had a civil war.”54 There likely was a power dynamic going on as well. Two struggling and poor districts—Wellston and Normandy Schools—simply did not have the political clout of the wealthier Clayton and Ladue districts. Thus, by placing the Wellston children into already faltering Normandy Schools, political peace was maintained but it came at the cost of the demise of Normandy Schools.

Figure 1. African American student enrollment (K–12) by school district, 2013.

![]()

And just like that, three years after Wellston was merged into Normandy Schools, Normandy collapsed. In September of 2012, DESE announced that, effective January of 2013, Normandy Schools would be unaccredited. This announcement triggered a Missouri law, known as the transfer law. This law provides that if a Missouri school was rendered unaccredited, the pupil residents in that district could opt to attend another accredited school in the same district, or could attend an accredited school in another district of the same or an adjoining county. The statute further mandated that the unaccredited district pay tuition for the transferring pupil to the accredited school and mandated that the unaccredited district choose a district for which it would also provide transportation.55

The Missouri transfer law dates back to 1931 but it was not until a 1993 amendment that the right of children in unaccredited schools to transfer to accredited schools was provided.56 Interestingly, the sponsor of the transfer law never imagined it would actually be triggered. The statutory terms were to be used as a stick to force struggling districts to improve. “It was meant to be harsh. It was a wake-up call to clean up your situation and get it fixed.”57 In 1993, then, had Normandy Schools—with its 5 out of 14 points—been labeled unaccredited, parents might have taken advantage of the benefits of the transfer law. But DESE did not label Normandy Schools as unaccredited in 1993 or at any time during the 1993–2012 school years. This failure to label the district unaccredited for almost 20 years prevented parents from transferring their children to better schools. Twenty years. An entire generation of children were trapped in a failing district and deprived of their right to fully perform their citizenship.

Even when it was prepared to acknowledge Normandy Schools’ unaccredited status in 2012, DESE still got it wrong. It announced in September of 2012 that Normandy Schools would become unaccredited in January of 2013. This delayed effective date of the change to unaccredited status again prevented parents from transferring their children into accredited schools at the start of the 2012 school year. Because the statute is not triggered until a school and/or district is officially labeled unaccredited, parents could not take their children out of the failed schools until the middle of the school year. Anyone knows that transferring a child in the middle of a school year is rarely in the child’s best interest.

Because of DESE’s manipulation of the timing of Normandy Schools’ unaccreditation, Normandy Schools did not experience the full impact of the transfer rule until the start of the 2013–2014 school year. In preparing for parents to exercise their children’s right to transfer under the law, Normandy Schools chose to provide transportation to the nearly all-White Francis Howell School District (Francis Howell), approximately 23 miles (and a very long bus ride) away. (See Figure 1.) Recall that there were two highly performing districts less than eight miles away from Normandy Schools. Not only were Clayton and Ladue substantially closer than Francis Howell to Normandy Schools, but Clayton and Ladue were also stronger academic districts. In virtually every category, Clayton and Ladue outperformed Francis Howell. (See Appendix.) Yet Normandy Schools chose the further, lower-performing district for its students.

Transfers were effective for the 2013–2014 school year. Of the approximately 4,100 students in Normandy Schools, 1,100 elected to transfer to various school districts. Approximately 430 selected Francis Howell because that was the district to which Normandy Schools would provide transportation.58

In the weeks and months after Normandy Schools announced its decision to provide transportation to Francis Howell, anyone who picked up a St. Louis newspaper would have thought they were reading stories from the 1950s. They told of interviews with parents in Francis Howell, social media comments, and town hall meetings where parents in Francis Howell worried about Normandy Schools children being a bad influence on the Francis Howell children. They worried about compromising their test scores and accreditation; despite the higher drug use in the district, they worried about increased drug use and the need for drug sniffing dogs. Some comments referred to the Normandy School’s children as trash, thugs, slum kids, and rapists.59 One comment summed it up this way: “Too bad this country places such an emphasis on publically subsidizing the least qualified citizens to reproduce. I wonder how much things would improve if instead of WIC and other such nonsense, the govt gave out vouchers for free abortions.”60 Additional similar comments posted on the Francis Howell website and Facebook page were so troubling that the district had to disable the comment feature. Of course many of these comments also denied that race and class had anything to do with their conclusions. Safety was touted as the number one concern. The local newspaper in St. Louis did a story highlighting Normandy as the “most dangerous school in the area.”61 The comments, though, clearly went beyond concerns for safety. Race was often front and center. And indeed, for those who believe otherwise, one need only read the comments that did explicitly cover race and unabashedly admitted that they did not want their children to attend schools with black children.62

Nonetheless, the transfers proceeded, and pursuant to statute, despite some parents’ concern that Normandy would not pay and would just suck their district dry, Normandy Schools wrote tuition checks to the tune of $1.5 million per month to the various transferee school districts, including Francis Howell.63 Three interesting things happened as a result of those transfers:

1) Not one of the perceived fears of the Francis Howell parents manifested.64

2) Although the transfer law contained no such limitation, DESE advised all districts to set class size limitations that were in the range of already acceptable limitations, and districts followed this advice.65 Schools did not have to deal, then, with hiring more teachers or finding additional classroom space. Some additional expenditures were necessary for extra books, art supplies, and such, but larger expenses like teacher salaries often were not.66 Thus, only a portion of the money paid by Normandy Schools to the transferee districts was used to cover additional expenses and in some cases, none of the tuition money was spent on the Normandy children.67

3) The payments virtually bankrupted Normandy Schools.68

The situation became so dire that on May 20, 2014, the State Board of the Department of Education used its statutory power to dissolve Normandy Schools. It then proceeded to create what it said was a new district, appointed a new school board for the district, and announced that the new district would be operated under direct state oversight. This, the State Board said, would provide the district with a new beginning. It did not accredit the “new” Normandy Schools but labeled it as a “‘State Oversight District’” without an accreditation status for up to three years.”69 This new district, then, would be not-unaccredited. And, this meant that the transfer statute would no longer apply. The new district, now called the Normandy Schools Collaborative (NSC), went into effect on July 1, 2014. Days later Francis Howell announced that it would not accept children from NSC. This decision was odd. After all, Francis Howell still had over a million dollars in tuition from NSC that it had not spent. There also were no concerns about drugs, violence, or crime. Nonetheless, the district stated that because NSC was no longer unaccredited, the statute no longer applied.70 Several parents who wanted their children to continue to attend Francis Howell filed a lawsuit for injunctive relief to force that district to accept the students. A hearing was held on August 6, 2014, the first day of school in Francis Howell.

In the meantime, schools in NSC were scheduled to begin classes on August 11, 2014. Many children who lived near the Canfield Green Apartments, where Michael Brown was killed just 48 hours earlier, attended school in NSC. Emotions and tensions were high. Readers will recall the protests and civil unrest, tear-gas-filled air, military-style tanks, and police with assault rifles pointed and ready to shoot that marked Ferguson streets for the days and weeks after the Brown killing. In the midst of that turmoil and a week and a half after school had already begun in Francis Howell, a judge in St. Louis County enjoined Francis Howell from preventing the plaintiff children from coming back. Finding NSC “abysmally unaccredited,” the judge stated that irreparable harm would occur if the students, who wished to transfer and had done everything necessary to effectuate their right to transfer under the law, were not permitted to return to the district.71

To put the judge’s statement that NSC was “abysmally unaccredited” into perspective, consider the following: In 2013, DESE adopted a new measure of performance based on a 140-point scale. A district needs 50–60 percent of those points to be accredited.72 In 2013 NSC earned a total of 11.1 percent. By the time Michael Brown graduated one year later, it had earned just 7.1 percent.73 This was the worst academic record in the state.74 The court noted that under these circumstances, any attempt to recognize NSC as anything other than unaccredited would “completely def[y] logic.”75

Even after the judge’s order, however, Francis Howell required each student who wanted to return to have his or her own uniquely signed court order in hand. Thus another fight ensued for parents who thought the August 15 court order was enough. The court’s preliminary injunction became final in February of 2015. Although it took some time (critical time, in fact, for a parent wanting to return to Francis Howell), Francis Howell finally, albeit begrudgingly, accepted the students. All of this uncertainty and instability, two things no child ever needs, were happening in the midst of the turmoil and unrest of Ferguson in the aftermath of the Michael Brown killing. Michael Brown’s youngest sister attended school in this very district. This gives you a sense of how close the students in the school were to the issues simultaneously going on outside of the schoolhouse doors. The stress load on many parents and children alike was often too great to bear.

Thus, only about 110 of the 430 students who transferred to Francis Howell the prior year took advantage of the court victory. There were many students who, once the district stated that they could not return, did not fill out the proper “intent to return” documents. When Francis Howell tried to enforce the deadline, another fight was had, and the parents again won. Many parents, though, were simply tired of their children being batted about like balls in a ping pong game. The stress load in the community was already on overload. And a lingering question remained: Would the children be able to stay in Francis Howell once and for all, or would they be going through similar battles in the foreseeable future? In other words, if Normandy regained accreditation the next year or the year after, would Francis Howell push those children out and force them to return to their home school district or allow them to stay and graduate from their new school? Most parents decided to keep their children in Normandy Schools. Tanks and tear gas on the streets, fights with the Francis Howell school district, angry White parents in Francis Howell, two-hour-long one-way bus commutes, and the uncertainty of being able to stay in and graduate from high school in Francis Howell forced many parents to choose the devil they knew.

At the time of this writing, NSC continues to send tuition payments out to school districts including Francis Howell. It continues to have a student body that is over 97 percent Black, over 90 percent on free or reduced lunch, and struggling with tremendous academic issues. There are also behavioral challenges with the Normandy Schools children.76 And, as discussed infra, NSC continues to have challenges with curriculum offerings, resources, and teacher expectations. The district is segregated by race, unequal on almost every measurable level, and there is no relief in sight.

What Is Left of Brown?

Nine months after Michael Brown’s killing, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch ran a story on his former high school.77 The story was written from the vantage point of Cameron Hensley, then a senior honors student. Hensley, unlike a number of his high-achieving classmates, had opted not to exercise his rights under the transfer statute, choosing instead to remain at NSC.78 The story revealed no new beginning, as promised by state education officials; no expectations, few books, no homework, and no attempt to educate. Specifically, readers learned that at Normandy High School, there were: zero honors courses; seniors reading on a third-grade level; a physics teacher who had not planned a lesson in months; substitute teachers who had been substituting the same class since the beginning of the school year; unsupervised and unattended students sleeping in class, taking pictures, practicing dance routines, all in front of teachers who were in the classroom but not teaching; an AP English class taught by an instructor not certified to teach it; rooms that smelled like mildew and lacked adequate air conditioning; no school books to take home; and virtually nonexistent homework.79 For students like Michael Brown and Cameron Hensley, who opted to stay in their home schools, no tangible benefits of the victory in Brown over 60 years earlier could be seen in their schools. They attended racially segregated schools, overwhelmingly poor schools, and extremely underperforming (and thus unequal) schools. Supreme Court precedents kept them in segregated schools, compulsory attendance laws required their attendance in segregated and underperforming schools, and despite that compulsory attendance, they were virtually ignored once inside the building.

Normandy Schools are reflective of many public schools throughout the nation. Dysfunction, racial segregation, and unequal education plague Black, Brown, and poor children in public schools.80 Normandy Schools are not an anomaly. What is happening there, what has happened there, is reflective of a national story.81 Indeed, public schools remain “so separate and vastly unequal that Plessy v. Ferguson, not Brown v. Board of Education, might as well be the law of the land.”82 Historical segregation and discrimination have laid the foundation for what we continue to see today. But it is the current trappings of poverty and unequal access to opportunity and resources, that is, the legacies of Plessy, that continue to smother the academic achievement of poor students, of Black students, of Brown students, and even of Native American students.

What Now?

For 60-plus years, we have defined integration in terms of White and Black. We can no longer do this given declining White births, increasing births among non-White Hispanic populations, and continued White flight from public schools. It is becoming harder to integrate, if integration is defined in Black and White. Of course, the benefits of diversity have been well established, so although increasingly difficult to implement, we should continue to work to integrate schools in spaces where that is still possible. But integration based on the Black/White model can no longer be the goal.

There remain real structural barriers to quality education. Racial isolation, class and housing segregation, unemployment and underemployment, concentrated poverty, inadequate access to nutritional food, inadequate health care and access to health care, and criminalization are just a part of the vicious cycle keeping people and their children trapped in dysfunction, inequity, and inequality.83 Many children also come from communities afflicted with drugs, violence, and gangs. Family support structures are not always present. Many come from single-parent homes and homes where the students may have to care for younger siblings or work themselves to help the family survive. Many parents are uneducated themselves, coming from the same dysfunctional school systems their children attend. Consider too practices that prey on the working poor, like the failure to pay living wages, higher rents and food prices, predatory loans and interest rates, and municipal court abuses as reflected earlier in chapter 3. All of these certainly have negative repercussions on the lives of the children who live in these communities and on their cognitive development, learning capability, and attentiveness in school. Imagine trying to attend school and learn and thrive with this weight on your shoulders. Michael Brown’s mother is often quoted for asking a reporter shortly after her son’s death: “Do you know how hard it was for me to get him to stay in school and graduate?”84 Maybe we can see a little of what she meant now.

Systemic educational deficiencies are part of the problem as well. Many children do not receive the critical early childhood education that they need to set their foundation for future learning. Despite the evidence of the importance of early childhood education, many districts in poor communities do not have early childhood education programs. Children without this access begin kindergarten behind the starting line.85 We must find the funding for these proven means of providing the educational foundation children need. Early childhood interventions can and should also include work with parents and other care providers.86 Schools should receive adequate funding to provide wraparound services to meet the needs of the students, the parents, and the community. Consider the work of Superintendent Tiffany Anderson in the Jennings School District, in close proximity to Normandy Schools. Superintendent Anderson was recognized by Education Week in 2015 as one of “the nation’s 16 most innovative district leaders” in its 2015 Leaders to Learn From report. Despite a predominately Black, poor, and academically struggling district, Superintendent Anderson has implemented a variety of social services that reach into her district’s community and therefore reaches her students. And her academic numbers have consistently improved over the past few years.87

Schools also need basic resources: textbooks, desks, chairs, science laboratory equipment, chalk. Schools need certified, qualified, degreed, well-paid, diverse, and empathetic teachers who care about their students and who have expectations of them. Recall from the OCR report cited earlier that the best teachers do not gravitate to poor districts and it is not uncommon that many of the teachers in these districts are less experienced and hold fewer degrees than teachers in more affluent districts, and some have little or no expectations of their students.88 Diverse teachers also are lacking despite the overwhelmingly Black and Brown student populations.89 Explicit and implicit racial biases negatively inform and often taint teacher assumptions and conclusions about students and exacerbate the school to prison pipeline.90 All of this can be addressed and remedied.

We must also rethink how schools are funded. Most public schools are funded by property taxes under the guise of local control. Such limited funding not only hurts the educational prospects for children who live in property-poor districts,91 but also works to keep schools segregated.92 Indeed, affluent communities often fight efforts to bring affordable housing to their communities.93 And, as long as housing is segregated and schools are assigned by neighborhoods, schools will continue to be segregated based on class and/or race.94 But there is an answer to this. We could change the way students are assigned to schools. Legislatures can remedy this deficiency by reassigning schools based on factors other than zip codes. For example, socioeconomic status is an acceptable way of assigning students to schools and its benefits are well known.95 This has been suggested as a factor that should be considered when assigning schools.96 Similarly, the Obama administration has recommended that schools consider multiple factors like household income, educational attainment of the adults in the household, and racial and economic demographics of a neighborhood when assigning children to schools.97

What Now for Normandy?

For Normandy Schools, the question of “what now?” is still uncertain. The governor of Missouri announced a plan for the state and surrounding school districts to support Normandy Schools and fellow struggling district Riverview Gardens. The state will provide $500,000 in reading and literacy funding, while neighboring districts will lend varying support: curricula design assistance, teacher training, cost reductions from pooled purchasing power, reading and math specialists, and in some districts reductions in tuition for transfer students.98 Is this a step in the right direction or another Band-Aid? I think the latter. For decades now, Normandy children have been trapped in a failing and dying district. And they are not alone in the greater St. Louis area.99

The efforts previously mentioned at reforming unaccredited schools are not evidence of anything more than piecemeal and partial feel-good attempts at change. $500,000 and a little support by other districts is just feel good salve for the doers. It will not change the educational trajectory of the thousands of students in Normandy Schools or other failing districts. Sure, temporary relief might be had. But what is needed is more than temporary relief. We need systemic change. It is time to completely restructure how children are being educated in Missouri (and indeed, in public schools throughout America). But first, neighborhoods, like people, must be nourished. Communities need adequate housing, health care, and employment, for example. Districts must also meet children where they are. Recall the work of Superintendent Anderson in the Jennings School District, a district with near identical demographics to Normandy. There teachers are provided with dismantling racism training, poverty simulations, cultural and ethnic competency classes. Washers and dryers are made available for students. They have a health clinic in the school, parenting classes, and a food pantry. The district has a shelter for its homeless children. As the Superintendent says, it is impossible to teach if the child is cold, hungry, unhealthy, and has no place to live. Educating the child means treating the whole child and that requires meeting the child where the child is.100 States, including Missouri, need to reconsider the way it assigns children to schools. Clearly children are receiving a different quality of education depending on where they live. (Appendix.) This can and must be changed. Of course in order to do this in Missouri, we would need to consider consolidation of school districts. Currently the metropolitan area comprises 24 school districts. The districts would have to be consolidated into several larger groups or one large district, and children would need to be assigned along socioeconomic lines or a combination of other factors along the lines discussed earlier.

The solution of one unified school district in the St. Louis metropolitan area, at least, has been suggested before.101 And, while it has been rejected time and time again, it seems to be the only way to assure that every child in Normandy Schools and the other failing school districts can be assured of the opportunity of a quality education without regard to their zip code.102 It is the only way to ensure that every taxpayer, every teacher, every politician, and every parent is invested in the education of all. It is the only path on the road to full citizenship. It is the thing we have not tried.

Michael Brown attended school. He graduated. Given what you now know of the school district he graduated from, you might agree the road ahead of him would have been difficult had he lived. Indeed, underperforming schools, “a dearth of successful models, lack of networks that lead to jobs, unsafe streets, recurrent multi-generational family dysfunction, or the general miasma of depression that can pervade high poverty contexts may inhibit the success of even the most motivated.”103

St. Louis NAACP City Chapter President Adolphus Pruitt once noted that “if the districts cannot find a way to properly educate their children, they might as well put a gun to their head and kill them…. The outcome of failing to get a good education is ruining their lives. I make that statement because it is that serious of an issue. It impacts everything.”104 While the statement regarding guns to the head is merely hyperbole, we know that the rest of the statement is certainly true.

At the time of this writing, it is one year after Michael Brown’s death. A new school year has just begun. Welcome Back signs greet students in Normandy everywhere. The question now is, Welcome back to what?

Notes

1. Julie Bosman & Emma G. Fitzsimmons, Grief and Protests Follow Shooting of a Teenager: Police Say Michael Brown Was Killed after Struggle for Gun in St. Louis Suburb, N.Y. TIMES, Aug. 10, 2014, http://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/11/us/police-say-mike-brown-was-killed-after-struggle-for-gun.html.

2. Id. Michael Brown was scheduled to attend Vatterott College, a for-profit school interested in “the UN-DER world: [the] Unemployed, Underpaid, Unsatisfied, Unskilled, Unprepared, Unsupported, Unmotivated, Unhappy and Underserved.” See Nikole Hannah-Jones, School Segregation, the Continuing Tragedy of Ferguson, PROPUBLICA, Dec. 19, 2014, http://www.propublica.org/article/ferguson-school-segregation. Hannah-Jones conducted a very powerful interview on the Normandy School system in a segment of This American Life. It is worth the time to listen. Go to: http://www.thisamericanlife.org/radio-archives/episode/562/the-problem-we-all-live-with.

3. Brown v. Bd. of Educ., 347 U.S. 483 (1954) (Brown I).

4. Slavery and the Making of America, PBS (broadcast Feb. 9 & 16, 2005), http://www.pbs.org/wnet/slavery/experience/education/docs1.html.

5. See generally W. E. BURGHARDT DU BOIS, BLACK RECONSTRUCTION IN AMERICA: 1860–1880 (1935).

6. See, e.g., JOHN HOPE FRANKLIN, FROM SLAVERY TO FREEDOM, THIRD EDITION: A HISTORY OF NEGRO AMERICANS (1971).

7. Plessy v. Ferguson, 16 S. Ct. 1138 (1896).

8. See generally MICHELLE ALEXANDER, THE NEW JIM CROW, MASS INCARCERATION IN THE AGE OF COLORBLINDNESS (THE NEW PRESS 2012); DOUGLAS A. BLACKMON, SLAVERY BY ANOTHER NAME: THE RE-ENSLAVEMENT OF BLACK AMERICANS FROM THE CIVIL WAR TO WORLD WAR II (2009).

9. See, e.g., JANET DUITSMAN CORNELIUS, WHEN I CAN READ MY TITLE CLEAR (1991); IRA BERLIN, MARC FAVREAU & STEVEN F. MILLER, REMEMBERING SLAVERY (2013).

10. HEATHER ANDREA WILLIAMS, SELF-TAUGHT 106–08 (2005).

11. This story is documented in The Road to Brown (Cal. News Reel 2004). Some of the cases leading up to the Brown decision included Pearson v. Murray, 169 A.2d 478 (1936) (University of Maryland School of Law ordered to admit Black male student); Mo. ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U.S. 337 (1938) (University of Missouri School of Law ordered to admit Black male student); Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629 (1950) (University of Texas ordered to admit Black male student); Sipuel v. Board of Regents of the University of Oklahoma, 332 U.S. 631 (1948) (University of Oklahoma School of Law obligated under the equal protection clause to provide Black female plaintiff same educational opportunity as provided to White students); and McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents for Higher Education, 339 U.S. 637 (1950) (segregation of Black male student in University of Oklahoma’s doctoral program violated equal protection clause).

12. Brown I, 347 U.S. at 493.

13. Brown v. Bd. of Educ., 349 U.S. 294 (1955) (Brown II).

14. See, e.g., PBS, The Supreme Court: Expanding Civil Rights, Primary Sources, Southern Manifesto on Integration (Mar. 12, 1956), http://www.pbs.org/wnet/supremecourt/rights/sources_document2.html (19 senators and 77 members of the House of Representatives signed the “Southern Manifesto,” promising to use all lawful means to bring about a reversal of Brown). In 1957, Elizabeth Eck-ford, one of the Little Rock Nine, famously walked through a mob of angry White protestors in order to desegregate Central Rock High School. JAMES T. PATTERSON, BROWN V. BOARD OF EDUCATION: A CIVIL RIGHTS MILESTONE AND ITS TROUBLED LEGACY (2001). Prince Edward County closed all public schools from 1959 to 1964 in lieu of desegregating them. Id. In 1960, federal marshals escorted six-year-old Ruby Bridges into her new all-White school. Id. In 1963 then Alabama Governor George Wallace famously blocked the entrance to the University of Alabama, refusing to allow two Black students—Vivian Malone and James Hood—to enter the school. B.J. HOLLARS, OPENING THE DOORS: THE DESEGREGATION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ALABAMA AND THE FIGHT FOR CIVIL RIGHTS IN TUSCALOOSA (2013).

15. See Green v. Sch. Bd. of New Kent Cnty., 391 U.S. 430 (1968); Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 402 U.S. 1 (1971); Keyes v. Sch. Dist. No. 1, Denver, 413 U.S. 189 (1973).

16. COLIN GORDON, MAPPING DECLINE: ST. LOUIS AND THE FATE OF THE AMERICAN CITY (2009).

17. Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S. 717 (1974). See also Cedric Merlin Powell, Milliken, “Neutral Principles,” and Post-Racial Determinism, 31 HARV. J. ON RACIAL & ETHNIC JUST. 1 (Spring 2015).

18. Milliken, 418 U.S. at 752.

19. See, e.g., Milliken; Bd. of Educ. of Okla. City Pub. Sch. v. Dowell, 498 U.S. 237 (1991); Freeman v. Pitts, 122 S. Ct. 1430 (1992); Missouri v. Jenkins, 115 S. Ct. 2038 (1995).

20. Dowell, 498 U.S. at 638.

21. Parents Involved in Cmty. Sch. v. Seattle Sch. Dist. No. 1, 551 U.S. 701 (2007) (PICS).

22. Id. at 726. The Court left undisturbed prior rulings that race could be considered to remedy the effects of past discrimination and to diversify the student body in higher education. Id. at 720–22.

23. GARY ORFIELD ET AL., BROWN AT 60 (Civil Rights Project May 15, 2014), http://civilrightsproject.ucla.edu/research/k-12-education/integration-and-diversity/brown-at-60-great-progress-a-long-retreat-and-an-uncertain-future/Brown-at-60-051814.pdf [hereinafter BROWN AT 60].

24. ERICA FRANKENBERG, CHUNGMEI LEE & GARY ORFIELD, A MULTIRACIAL SOCIETY WITH SEGREGATED SCHOOLS: ARE WE LOSING THE DREAM (Civil Rights Project Jan. 2003), http://civilrightsproject.ucla.edu/research/k-12-education/integration-and-diversity/a-multiracial-society-with-segregated-schools-are-we-losing-the-dream/frankenberg-multiracial-society-losing-the-dream.pdf. See also BROWN AT 60, supra note 23.

25. Valerie Strauss, For the First Time Minority Students Expected to Be Majority in U.S. Public Schools This Fall, WASH. POST, Aug, 21, 2014, http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/answer-sheet/wp/2014/08/21/for-first-time-minority-students-expected-to-be-majority-in-u-s-public-schools-this-fall. Most public school students today are also poor, qualifying for free and reduced lunch, the educational predictor for poverty. See Lyndsey Layton, Majority of U.S. Public School Students Are in Poverty, WASH. POST, Jan. 16, 2013, http://www.washingtonpost.com/local/education/majority-of-us-public-school-students-are-in-poverty/2015/01/15/df7171d0-9ce9-11e4-a7ee-526210d665b4_story.html.

26. See William H. Frey, Shift to a Majority Minority Population in the U.S. Happening Faster than Expected, BROOKINGS INST., June 19, 2013, http://www.brookings.edu/blogs/up-front/posts/2013/06/19-us-majority-minority-population-census-frey; BROWN AT 60, supra note 23, at 6.

27. Linda Sheryl Greene, The Battle for Brown, 68 ARK. L. REV. 131, 132 (2015).

28. Brown I, 347 U.S. at 493.

29. Edward Graham, “A Nation at Risk” Turns 30: Where Did It Take Us?, NEA (Apr. 25, 2013), http://neatoday.org/2013/04/25/a-nation-at-risk-turns-30-where-did-it-take-us-2/. See also U.S. DEP’T OF EDUC., PERFORMANCE OF U.S. 15-YEAR-OLD STUDENTS IN MATHEMATICS, SCIENCE, AND READING LITERACY IN AN INTERNATIONAL CONTEXT (2014), http://nces.ed.gov/pubs2014/2014024rev.pdf.

30. See, e.g., U.S. DEP’T OF EDUC., AVERAGED HIGH SCHOOL GRADUATION RATES OF PUBLIC SECONDARY SCHOOLS (2014), http://dashboard.ed.gov/statecomparison.aspx?i=e&id=6&wt=40 (state-by-state comparison of average freshman graduation rates from public secondary schools for the various racial/ethnic groups).

31. This chapter does not address school discipline matters, which also plague public schools with glaring racial disparities. See Daniel Losen et al., Are we Closing the School Discipline Gap?, CIVIL RIGHTS PROJECT 1 (Feb. 2015), http://civilrightsproject.ucla.edu/resources/projects/center-for-civil-rights-remedies/school-to-prison-folder/federal-reports/are-we-closing-the-school-discipline-gap/AreWeClosingTheSchoolDisciplineGap_FINAL221.pdf; U.S. DEP’T OF EDUC., CIVIL RIGHTS DATA COLLECTION DATA SNAPSHOT: SCHOOL DISCIPLINE (Mar. 2014), https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/docs/crdc-discipline-snapshot.pdf; Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw with Priscilla Ocen and Jyoti Nanda, Black Girls Matter: Pushed Out, Overpoliced and Underprotected, AFRICAN AM. POL’Y FORUM, http://www.atlanticphilanthropies.org/sites/default/files/uploads/BlackGirlsMatter_Report.pdf.

32. BLACK LIVES MATTER: THE SCHOTT 50 STATE REPORT ON PUBLIC EDUCATION AND BLACK MALES (Schott Found. 2015) [hereinafter BLACKLIVESMATTER REPORT].

33. Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Educ., U.S. High School Graduation Rate Hits New Record High, Feb. 12, 2015, http://www.ed.gov/news/press-releases/us-high-school-graduation-rate-hits-new-record-high.

34. See, e.g., Kimberly Jade Norwood, Adult Complicity in the Dis-Education of the Black Male High School Athlete & Societal Failures to Remedy His Plight, 34 THUR. MAR. L. REV. 21 (2008). See also “Cheated” Out of an Education: Book Replays UNC’s Student-Athlete Scandal, NPR (broadcast Mar. 23, 2015, 6:46 PM), http://www.npr.org/2015/03/23/394884826/cheated-out-of-an-education-book-replays-unc-s-student-athlete-scandal.

35. See, e.g., Nat’l Ctr. for Educ. Statistics, NAEP Data Explorer: Reading Grade 12, http://nces.ed.gov/nationsreportcard/naepdata/report.aspx?app=NDE&p=3-RED-2-20133%2c20093%2c20053%2c20023%2c19983%2c19982%2c19942%2c19922-RRPCM-GENDER%2cSDRACE-NT-MN_MN-J_Y_0-1-0-37 (last visited July 13, 2015).

36. Nat’l Ctr. for Educ. Statistics, NAEP Glossary of Terms (2015), https://nces.ed.gov/nationsreportcard/glossary.aspx?nav=y#proficient.

37. BLACKLIVESMATTER REPORT, supra note 32, at 39.

38. The New York State Department of Education defines level 1 as follows: NYS Level 1: Students performing at this level are well below proficient in standards for their grade. They demonstrate limited knowledge, skills, and practices embodied by the New York State P–12 Common Core Learning Standards for Mathematics that are considered insufficient for the expectations at this grade. N.Y. Dep’t of Educ., Definitions of Performance Levels (2014), http://www.p12.nysed.gov/irs/ela-math/2014/2014-MathDefinitionsofPerformanceLevels.pdf.

39. N.Y. Dep’t of Educ., 3–8 ELA Assessments (2014), http://data.nysed.gov/assessment38.php?year=2014&subject=ELA&state=yes. The assessments for mathematics were nearly identical (47 percent Black students as compared to 21 percent White students). See 3–8 ELA Assessments (2014), http://data.nysed.gov/assessment38.php?year=2014&subject=Mathematics&state=yes.

40. D.C. Pub. Sch., DCPS Data Sets, http://dcps.dc.gov/DCPS/About+DCPS/DCPS+Data/DCPS+Data+Sets (last visited July 13, 2015).

41. Id.

42. See, e.g., San Antonio Indep. Sch. Dist. v. Rodriguez, 411 U.S. 1 (1973). In 2006, Oprah Winfrey aired a special report titled “Schools in Crisis.” Although the report focused on many inferior public school buildings in inner cities throughout America, one particular experiment revealed in the report is worth noting. A group of students from a poor inner-city school in Chicago with a graduation rate of 40 percent traded places for a day with a group of students from an affluent suburban school 35 miles west of the city and with a graduation rate of 99 percent. The students from the inner-city school were overwhelmingly Black while the students from the affluent suburban school were predominately White. The physical structure of the two facilities were vastly different, with the inner-city school barely structurally sound and the suburban school a multimillion-dollar facility. Inside, the buildings continued to reflect the vast differences in resources. Working computers with keyboards (with all keys intact), instruments for music classes, award winning music programs, fully functional science laboratories, state of the art—and thus actually working—exercise equipment, cardio rooms, and water-filled pools, to name a few amenities, were all available in the suburban school, but completely absent in the inner-city school. Even the level of expectation from teachers and rigor in classrooms were vastly different between the schools. An “A” student in math from the inner-city school sat in on a comparable class in the suburban school and later remarked: “I was looking at the math problems that they’re doing and I was like what language is that? Soon as I get to college, I’mma be lost.” The Oprah Winfrey Show: Oprah’s Special Report: American Schools in Crisis (Harpo Prods. Inc. television broadcast Apr. 12, 2006).

43. Letter from Catherine E. Lhamon, Assistant Sec’y for Civil Rights, to colleagues (Oct. 1, 2014), http://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/letters/colleague-resourcecomp-201410.pdf (emphasis added).

44. “Apartheid schools” is a term used to describe schools that are 90% or more Black and/or brown. See, e.g., Lilly Workneh, March 26, 2014, Study: NY schools most segregated in US labeling some “apartheid schools;” http://thegrio.com/2014/03/26/study-ny-schools-most-segregated-in-the-us-labeling-some-apartheid-schools/; see also Jonathan Kozol, Shame of the Nation 19 (2005). This frequently also means that the school is likely a high poverty one. See, e.g., supra note 25.

45. For studies in the history of the White communal beginnings of the suburbs immediately surrounding St Louis city, see GORDON, supra note 16.

46. See, e.g., Hannah-Jones, supra note 2. From 1972 through 1999, SLPSD was at the center of the largest voluntary desegregation lawsuit (and settlement) in the country. Minnie Liddell, a Black parent who resided in the City of St. Louis, filed a lawsuit in 1972 against SLPSD and the state of Missouri to force those entities to comply with the mandate of Brown. The lawsuit eventually ballooned to include over 20 suburban school district defendants. Settlement included transportation of some Black students from the city schools into largely White suburban schools and the transfer of some White suburban children into city magnet schools. This arrangement did not allow transfers between county schools. Normandy Schools, a county school district, was not a defendant in the case. Not being a party to the lawsuit, it could not benefit from the settlement. More importantly, even had it been a defendant, as a county district, it would not have been eligible to transfer students from its primarily Black school district to any of the largely White county school districts. See, e.g., GERALD W. HEANEY & SUSAN UCHITELLE, UNENDING STRUGGLE: THE LONG ROAD TO AN EQUAL EDUCATION IN ST. LOUIS (2004). I explored areas that unfolded after this book’s publication. See Kimberly Jade Norwood, Minnie Liddell’s Forty-Year Quest for Quality Public Education Remains a Dream Deferred, 40 WASH. U. J.L. & POL’Y 1 (2012).

47. E-mail from Carol D. McCauley, Custodian of Records for the Normandy Schools Collaboration (June 8, 2015, 17:48 CST) (on file with author).

48. See, e.g., MO. CODE REGS. ANN. tit. 5, § 20-100.105.

49. MO. DEP’T OF ELEMENTARY & SECONDARY EDUC., COMPREHENSIVE GUIDE TO MISSOURI SCHOOL IMPROVEMENT PROGRAM 1 (May 2012), http://dese.mo.gov/sites/default/files/MSIP-5-comprehensive-guide.pdf.

50. Norwood, supra note 46, at 32.

51. E-mail from Kelli Dickey (June 4, 2015, 11:05 CST) (on file with author). See also Mo. Dep’t of Elementary & Secondary Educ., 2012 School District Performance and Accreditation: A Presentation to the State Board of Education 109 (Sept. 18, 2012) (on file with author); Mo. Dep’t of Elementary & Secondary Educ., What Happens When a School District Becomes Unaccredited? (May 2012).

52. Leah Thorsen, School Merger Draws Fire at Forum That Draws More Than 400 People; Wellston District Residents Question Whether Normandy Schools Are Much Better, ST. LOUIS POST-DISPATCH, Dec. 15, 2009, http://www.stltoday.com/news/school-merger-draws-fire-at-forum-that-draws-more-than/article_a713f679-717d-526b-bb7c-4b792d335237.html.

53. Children have a right to free education in Missouri. MO. CONST. art. IX, § 1(a). State statutes require that school aged children from a lapsed district be reassigned to another school district or districts. MO. ANN. STAT. § 162.081 (West 2015). See also MO. ANN. STAT. § 167.121 (West 2015) (setting forth the residency requirements to register a pupil in a school district); MO. ANN. STAT. § 167.121 (West 2015) (noting circumstances of hardship under which students may be assigned to a district other than that of residence).

54. Hannah-Jones, supra note 2.

55. MO. REV. STAT. §167.131 (2000). For additional analysis of this law, see Norwood, supra note 46.

56. Norwood, supra note 46, at 40–42.

57. Elisa Crouch & Jessica Bock, School Transfer Issue Spawns Logistical Headaches and Legal Questions, ST. LOUIS POST-DISPATCH, Aug, 4, 2013, http://www.stltoday.com/news/local/education/school-transfer-issue-spawns-logistical-headaches-and-legal-quetions/article_d3942b4b-24ee-5246-9743-77fed0b8579a.html.

58. Massey v. Normandy Schs. Collaborative, No. 14SL-CC02359 (St. Louis Cnty. Ct. Feb. 11, 2015 (Findings of Fact, Conclusions of Law, Final Order, and Judgment).

59. See, e.g., Chris McDaniel, Francis Howell Parents Express Outrage over Incoming Normandy Students, ST. LOUIS PUB. RADIO, Jul 12, 2013, http://news.stlpublicradio.org/post/francis-howell-parents-express-outrage-over-incoming-normandy-students.

60. FB Post to Francis Howell Facebook Page by Todd Breer, July 11 at 8:39 am.

61. Elisa Crouch, May 5, 2013, Normandy High: The most dangerous school in the area, http://www.stltoday.com/news/local/education/normandy-high-the-most-dangerous-school-in-the-area/article_49a1b882-cd74-5cc4-8096-fcb1405d8380.html.

62. All comments are on file with the author.

63. Elisa Crouch, Efforts to Improve Normandy Schools Have Fallen Short, State Board Admits, ST. LOUIS POST-DISPATCH, May 19, 2015, http://www.stltoday.com/news/local/education/efforts-to-improve-normandy-schools-have-fallen-short-state-board/article_65d7b44b-6407-5c94-96b9-1b5a62d09856.html.

64. Jessica Bock, Francis Howell Officials Say ‘No’ to Normandy Students, ST. LOUIS POST-DISPATCH, June 21, 2014, http://www.stltoday.com/news/local/education/francis-howell-officials-say-no-to-normandy-students/article_fad2b8bd-3631-5b51-9c58-e31ccf5d2a22.html.

65. Elisa Crouch, Missouri Offers Some Relief on Impending School Transfers, ST. LOUIS POST-DISPATCH, June 20, 2013, http://www.stltoday.com/news/local/education/missouri-offers-some-relief-on-impending-school-transfers/article_bca34ac8-c8ad-51d3-8a90-e60a3aacbaeb.html. In the Guidance for Student Transfer from Unaccredited Districts to Accredited Districts, DESE also imposed arbitrary time limits on when students could sign up to transfer, see Mo. Dep’t of Elementary & Secondary Educ., Guidance for Student Transfer from Unaccredited Districts to Accredited Districts, STlTODAY.COM, http://www.stltoday.com/guidelines-for-student-transfers/pdf_7760177a-6fbf-5e35-b702-b05bc557d53f.html.

66. See also Elisa Crouch & Jessica Bock, Money Being Paid by Normandy, Riverview Gardens to Other Districts Not Being Spent, ST. LOUIS POST-DISPATCH, Feb. 10, 2014, http://www.stltoday.com/news/local/education/money-being-paid-by-normandy-riverview-gardens-to-other-districts/article_f2ae8233-bf03-57b3-9270-dcc5366de090.html.

67. Id.

68. Dale Singer, Normandy Not Bankrupt Now, but Its Future Remains Cloudy, ST. LOUIS PUB. RADIO, Mar. 31, 2014, http://news.stlpublicradio.org/post/normandy-not-bankrupt-now-its-future-remains-cloudy.

69. Massey, supra note 58.

70. Bock, supra note 64.

71. Massey, supra note 58.

72. Today districts are “accredited with distinction” if they obtain at least 90 percent of all possible points (126–140 points); “accredited” if they have 70–89.9 percent of the possible points (98–125 points); “provisionally accredited” if they have between 50 and 69 percent of the relevant points (70–97 points). If the district has less than 50 percent of the points (0–69 points), the district is unaccredited. Mo. Dep’t of Elementary & Secondary Educ., MSIP 5 Questions and Answers, http://dese.mo.gov/sites/default/files/msip5-faq.pdf.

73. Mo. Dep’t of Elementary & Secondary Educ., LEA Summary for Annual Performance Report–Public, http://mcds.dese.mo.gov/guidedinquiry/MSIP%205%20%20State%20Accountability/LEA%20Summary%20for%20Annual%20Performance%20Report%20-%20Public.aspx?rp:Year=2014&rp:District=096109.

74. See Mo. Dep’t of Elementary & Secondary Educ., Normandy School District Report Card 2000–2014, http://mcds.dese.mo.gov/guidedinquiry/School%20Report%20Card/District%20Report%20Card.aspx?rp:SchoolYear=2014&rp:SchoolYear=2013&rp:SchoolYear=2012&rp:SchoolYear=2011&rp:DistrictCode=096109. See also Mo. Dep’t of Elementary & Secondary Educ., Normandy School District Demographic Data 2005–2014, http://mcds.dese.mo.gov/guidedinquiry/District%20and%20Building%20Student%20Indicators/District%20Demographic%20Data.aspx?rp:Districts=096109&rp:SchoolYear=2014&rp:SchoolYear=2013&rp:SchoolYear=2012&rp:SchoolYear=2011.

75. Massey, supra note 58.

76. See Elisa Crouch, Behavior Problems Boil Over at Normandy Schools, ST. LOUIS POST-DISPATCH, Sept. 12, 2014, http://www.stltoday.com/news/local/education/behavior-problems-boil-over-at-normandy-schools/article_dd9f1f26-06cb-5326-bcfa-3eec77e6f9c1.html; Elisa Crouch, Normandy High: The Most Dangerous School in the Area, ST. LOUIS POST-DISPATCH, May 5, 2013, http://www.stltoday.com/news/local/education/normandy-high-the-most-dangerous-school-in-the-area/article_49a1b882-cd74-5cc4-8096-fcb1405d8380.html.

77. Elisa Crouch, A Senior Year Mostly Lost for a Normandy Honor Student, ST. LOUIS POST-DISPATCH, May 4, 2015, http://www.stltoday.com/news/local/education/a-senior-year-mostly-lost-for-a-normandy-honor-student/article_ce759a06-a979-53b6-99bd-c87a430dc339.html.

78. As detailed elsewhere in this book, living in the Normandy School District during the time of Michael’s Brown’s death was incredibly stressful. Canfield Green Apartments was just five miles away. Not only were there psychic traumas as a result of the killing of Michael Brown, the leaving of his body in the street for four hours, the protests, the militarized police response, and the violence, but there were tremendous uncertainties among Normandy residents about whether accredited school districts would follow the court’s August 15 order. The Francis Howell School District fought the transfers as long as it could and even once it relented, parents in Francis Howell were not happy with the transfers and Normandy Schools parents did not know when/if Normandy Schools would declare bankruptcy and if so, what would happen to their children. Moreover, transfers only applied to unaccredited districts. What would happen a year or two or three down the road for a Normandy Schools child attending school in Francis Howell if Normandy Schools regained accreditation? Would the child be able to finish school in Francis Howell or be uprooted once again? Given these uncertainties, many parents opted to have their children stay in Normandy Schools. Staying meant that the children would be surrounded by a known and familiar environment and would be close to home. This also meant receiving an education in the worst district in the state. A year after Michael Brown’s death, these issues remain. Elisa Crouch, Normandy Transfer Students Left in the Lurch, Aug. 4, 2015, http://www.stltoday.com/news/local/education/normandy-transfer-students-left-in-the-lurch/article_3f127024-1997-55d5-8219-7a057b7ee259.html.

79. Crouch, supra note 77.

80. Analysis of Census Bureau data shows that while the percentage of children living in poverty declined for Hispanics, Whites, and Asians, the number remained steady for Black children, with poverty among Black children registering at almost 40 percent. This is the first time the number of Black children living in poverty surpassed the number of White children living in poverty. This is significant because there are three times as many White children as Black children in the United States. See Eileen Patten and Jens Manuel Krogstad, Black Child Poverty Rate Holds Steady, Even As Other Groups See Declines, PEW RES., July 14, 2015, http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2015/07/14/black-child-poverty-rate-holds-steady-even-as-other-groups-see-declines/.

81. As cities become more segregated, schools follow. See, e.g., BROWN AT 60, supra note 23. Even in completely integrated cities, segregated education thrives. See, e.g., N.R. Kleinfield, A System Divided: “Why Don’t We Have Any White Kids?,” N.Y. TIMES, May 13, 2012, at MB1.

82. JONATHAN KOZOL, SHAME OF THE NATION 216 (2005) (quoting Jack White, reporter for Time Mag.).

83. See, e.g., Richard Rothstein, For Public Schools, Segregation Then, Segregation Since: Education and the Unfinished March, ECON. POL’Y INST., Aug. 27, 2013, http://www.epi.org/publication/unfinished-march-public-school-segregation/; ALEXANDER, supra note 8.

84. Bosman & Fitzsimmons, supra note 1.

85. Eduardo Porter, Investments in Education May Be Misdirected, N.Y. TIMES, Apr. 2, 2013, http://www.nytimes.com/2013/04/03/business/studies-highlight-benefits-of-early-education.html?_r=0.

86. Lynn A. Karoly, M. Rebecca Kilburn & Jill S. Cannon, Proven Benefits of Early Childhood Interventions, (RAND 2005), http://www.rand.org/pubs/research_briefs/RB9145.html.

87. Rebecca Klein, How One Superintendent Is Improving Her Community by Improving Her Schools, HUFFINGTON POST, Feb. 27, 2015, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2015/02/27/tiffany-anderson-jennings_n_6770446.html.

88. See, e.g., Appendix. See also Barbara Glesner-Fines, The Impact of Expectations on Teaching and Learning, 38 GONZ. L. REV. 89 (2003); Linda Gorman, Good Teachers Raise Student Achievement, NBER DIGEST 4 (Aug. 2005), http://www.nber.org/papers/w11154.pdf.

89. Jesse J. Holland, Studies Highlight Teacher-Student Diversity Gap, BOS. GLOBE, May 5, 2014, https://www.bostonglobe.com/news/nation/2014/05/04/teachers-nowherenot-diverse-their-students/Wq6nM4XOyoMwlOYJLtfL3L/story.html.

90. See Aleasa M. Word, Unconscious Bias and the School to Prison Pipeline, GOOD MEN PROJECT, Sept. 29, 2015, http://goodmenproject.com/featured-content/unconscious-bias-and-the-school-to-prison-pipeline-wrd/.

91. How Do We Fund Our Schools?, PBS (Sept. 5, 2008), http://www.pbs.org/wnet/wherewestand/reports/finance/how-do-we-fund-our-schools/?p=197.

92. See, e.g., Ericka K. Wilson, Toward a Theory of Equitable Federated Regionalism in Public Education, 61 UCLA L. REV. 1416, 1439 (2014).

93. See generally SHERYLL CASHIN, THE FAILURES OF INTEGRATION: HOW RACE AND CLASS ARE UNDERMINING THE AMERICAN DREAM, ch. 3 (2004); John Eligon, An Indelible Black-and-White Line: A Year after Ferguson, Housing Segregation Defies Tools to Erase It, N.Y. TIMES, Aug. 9, 2015, http://www.nytimes.com/2015/08/09/us/an-indelible-black-and-white-line.html?hp&action=click&pgtype=Homepage&module=first-column-region®ion=top-news&WT.nav=top-news&_r=0.

94. HEATHER SCHWARTZ, HOUSING POLICY IS SCHOOL POLICY (CENTURY FOUND. 2010), https://www.tcf.org/assets/downloads/tcf-Schwartz.pdf.

95. RICHARD D. KAHLENBERG, THE FUTURE OF SCHOOL INTEGRATION: SOCIOECONOMIC DIVERSITY AS AN EDUCATION REFORM STRATEGY (CENTURY FOUND. 2012). See also Sheryll Cashin, Place, Not Race: Affirmative Action and the Geography of Educational Opportunity, 47 U. MICH. J. L. REFORM 935 (2014); Amy Stuart Wells & Erica Frankenberg, The Public Schools and the Challenge of the Supreme Court’s Integration Decision, 89(3) PHI DELTA KAPPAN 178–88 (2007). See also, Erica Frankenberg, The Promise of Choice, in EDUCATIONAL DELUSIONS? WHY CHOICE CAN DEEPEN INEQUALITY AND HOW TO MAKE SCHOOLS FAIR 75–78 (Gary Orfield & Erica Frankenberg eds., 2013).

96. See, e.g., U.S. DEP’T OF ED., GUIDANCE ON THE VOLUNTARY USE OF RACE TO ACHIEVE DIVERSITY AND AVOID RACIAL ISOLATION IN ELEMENTARY AND SECONDARY SCHOOLS (2012), http://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/docs/guidance-ese-201111.html.

97. Derek Black, Middle-Income Peers as Educational Resources and the Constitutional Right to Equal Access, 53 B.C. L. REV. 1 (2012).

98. Jessica Bock, 22 School Districts Offer to Help Normandy and Riverview Gardens Schools, ST. LOUIS POST-DISPATCH, June 23, 2015, http://www.stltoday.com/news/local/education/school-districts-offer-help-to-normandy-and-riverview-gardens-schools/article_e01a8007-6e76-59bd-9790-d3df36cf80b1.html.

99. Elisa Crouch & Walter Moskop, Poverty and Academic Struggle Go Hand in Hand, ST. LOUIS POST-DISPATCH, May 17, 2014, http://www.stltoday.com/news/local/education/poverty-and-academic-struggle-go-hand-in-hand/article_944bf0f6-c13f-5bbc-9112-9ab9ae205607.html.

100. The Superintendent Who Turned Around A School District, http://www.npr.org/2016/01/03/461205086/the-superintendent-who-turned-around-a-school-district?utm_source=npr_newsletter&utm_medium=email&utm_content=20160105&utm_campaign=npr_email_a_friend&utm_term=storyshare.

101. D. Bruce La Pierre, Voluntary Interdistrict School Desegregation in St. Louis: The Special Master’s Tale, 1987 WIS. L. REV. 971, 992 (1987).

102. Tony Messenger, Editorial, Time for the Spainhower Solution: Unify St. Louis Schools, ST. LOUIS POST-DISPATCH, Feb, 18, 2014, http://www.stltoday.com/news/opinion/columns/the-platform/editorial-time-for-the-spainhower-solution-unify-st-louis-schools/article_93dee4a2-f573-5a6e-919d-c97e7942f703.html. See also Elisa Crouch, Black Leadership Roundtable Proposes City-County School District, ST. LOUIS POST-DISPATCH, Nov. 15, 2014, http://www.stltoday.com/news/local/education/black-leadership-roundtable-proposes-city-county-school-district/article_6dd6c4fd-bc9b-5474-9525-3715e85cc807.html.

103. Cashin, supra note 95, at 940.

104. Crouch & Bock, supra note 57 (emphasis added).

Appendix

Public School District Characteristics

Source: Missouri Department of Elementary and Secondary Education (DESE)

*Percentage with a numerator less than 20. Data does not include students enrolled in the Special School District, private schools, or charter schools. ELA—English Language Arts; ACT—American College Testing; Below basic—Percent of students with an Achievement Level of Below Basic; Basic—Percent of students with an Achievement Level of Basic; Proficient—Percent of reportable students who scored Proficient; Advanced—Percent of reportable students who scored Advanced.