Directory A–Z

Accommodations

Climate

Customs Regulations

Electricity

Embassies & Consulates

Food

Gay & Lesbian Travelers

Health

Internet Access

Language Courses

Legal Matters

Maps

Money

Post

Public Holidays

Safe Travel

Telephone

Tourist Information

Travelers with Disabilities

Visas & Tourist Cards

Volunteering

Women Travelers

Directory A–Z

Book Your Stay Online

For more accommodation reviews by Lonely Planet authors, check out http://lonelyplanet.com/hotels/. You’ll find independent reviews, as well as recommendations on the best places to stay. Best of all, you can book online.

Accommodations

Cuban accommodations run the gamut from CUC$10 beach cabins to five-star resorts. Solo travelers are penalized price-wise, paying 75% of the price of a double room.

Budget

In this price range, casas particulares are almost always better value than a hotel. Only the most deluxe casas particulares in Havana will be over CUC$50, and in these places you're assured quality amenities and attention. In cheaper casas particulares (CUC$15 to CUC$20) you may have to share a bathroom and will have a fan instead of air-con. In the rock-bottom places (campismos mostly), you'll be lucky if there are sheets and running water, though there are usually private bathrooms. If you're staying in a place intended for Cubans, you'll compromise materially, but the memories are guaranteed to be platinum.

Midrange

Cuba's scant midrange category is a lottery, with some boutique colonial hotels and some awful places with spooky Soviet-like architecture and atmosphere to match. In midrange hotels you can usually expect air-con, private hot-water bathrooms, clean linens, satellite TV, a swimming pool and a restaurant, although the food won't exactly be gourmet.

Top End

The most comfortable top-end hotels are usually partly foreign-owned and maintain international standards (although service can sometimes be a bit lax). Rooms have everything that a midrange hotel has, plus big, quality beds and linens, a minibar, international phone service, and perhaps a terrace or view. Also falling into this category are the main all-inclusive resorts.

Price Differentials

Factors influencing rates are time of year, location and hotel chain. Low season is generally mid-September to early December and February to May (except for Easter week). Christmas and New Year is what's called extreme high season, when rates are 25% more than high-season rates. Bargaining is sometimes possible in casas particulares – though as far as foreigners go, it's not really the done thing. The casa owners in any given area pay generic taxes, and the prices you will be quoted reflect this. You'll find very few casas in Cuba that aren't priced between CUC$15 and CUC$50, unless you're up for a long stay. Prearranging Cuban accommodation has become easier now that more Cubans (unofficially) have access to the internet.

SLEEPING PRICE RANGES

The following price ranges refer to a double room with bathroom in high season.

$ less than CUC$50

$$ CUC$50–CUC$120

$$$ more than CUC$120

Types of Accommodations

Campismos

Campismos are where Cubans go on vacation (an estimated one million use them annually). Hardly camping, most of these installations are simple concrete cabins with bunk beds, foam mattresses and cold showers. There are over 80 of them sprinkled around the country in rural areas. Campismos are ranked either nacional or internacional. The former are (technically) only for Cubans, while the latter host both Cubans and foreigners and are more upscale, with air-con and/or linens. There are currently a dozen international campismos in Cuba ranging from the hotel-standard Villa Aguas Claras (Pinar del Río) to the more basic Puerto Rico Libre (Holguín).

For advance bookings, contact the excellent Cubamar in Havana for reservations. Cabin accommodation in international campismos costs from CUC$10 to CUC$60 per bed.

Casas Particulares

Private rooms are the best option for independent travelers in Cuba and a great way of meeting the locals on their home turf. Furthermore, staying in these venerable, family-orientated establishments will give you a far more open and less censored view of the country, and your understanding and appreciation of Cuba will grow far richer as a result. Casa owners also often make excellent tour guides.

You'll know houses renting rooms by the blue insignia on the door marked 'Arrendador Divisa.' There are thousands of casas particulares all over Cuba; well over 1000 in Havana alone and over 500 in Trinidad. From penthouses to historical homes, all manner of rooms are available from CUC$15 to CUC$50. Although some houses will treat you like a business paycheck, the vast majority of casa owners are warm, open and impeccable hosts.

Government regulation has eased since 2011, and renters can now let out multiple rooms if they have space. Owners pay a monthly tax per room depending on location (plus extra for off-street parking) to post a sign advertising their rooms and to serve meals. These taxes must be paid whether the rooms are rented or not. Owners must keep a register of all guests and report each new arrival within 24 hours. For this reason, you will also be requested to produce your passport (not a photocopy). Regular government inspections ensure that conditions inside casas remain clean, safe and secure. Most proprietors offer breakfast and dinner for an extra rate. Hot showers are a prerequisite. In general, rooms these days provide at least two beds (one is usually a double), fridge, air-con, fan and private bathroom. Bonuses could include a terrace or patio, private entrance, TV, security box, kitchenette and parking space.

Bookings & Further Information

Due to the plethora of casas particulares in Cuba, it is impossible to include even a fraction of the total. The ones chosen are a combination of reader recommendations and local research. If one casa is full, they'll almost always be able to recommend to you someone else down the road.

The following websites list a large number of casas across the country and allow online booking.

CubacasasCASA PARTICULAR

The best online source for casa particular information and booking; up to date, accurate and with colorful links to hundreds of private rooms across the island (in English and French).

Casa Particular OrganizationCASA PARTICULAR

Reader-recommended website for prebooking private rooms.

Hotels

All tourist hotels and resorts are at least 51% owned by the Cuban government and are administered by one of five main organizations. Islazul is the cheapest and most popular with Cubans (who pay in Cuban pesos). Although the facilities can be variable at these establishments and the architecture a tad Soviet-esque, Islazul hotels are invariably clean, cheap, friendly and, above all, Cuban. They're also more likely to be situated in the island's smaller provincial towns. One downside is the blaring on-site discos that often keep guests awake until the small hours. Cubanacán is a step up and offers a nice mix of budget and midrange options in cities and resort areas. The company has recently developed a new clutch of affordable boutique-style hotels (the Encanto brand) in attractive city centers such as Sancti Spíritus, Baracoa, Remedios and Santiago. Gaviota manages higher-end resorts including glittering 933-room Playa Pesquero, though the chain also has a smattering of cheaper 'villas' in places such as Santiago and Cayo Coco. Gran Caribe does midrange to top-end hotels, including many of the all-inclusive resorts in Havana and Varadero. Lastly, Habaguanex is based solely in Havana and manages most of the fastidiously restored historic hotels in Habana Vieja. The profits from these ventures go toward restoring Habana Vieja, which is a Unesco World Heritage Site. Except for Islazul properties, tourist hotels are for guests paying in convertible pesos only. Since May 2008 Cubans have been allowed to stay in any tourist hotels, although financially most of them are still out of reach.

At the top end of the hotel chain you'll often find foreign chains such as Sol Meliá and Iberostar running hotels in tandem with Cubanacán, Gaviota or Gran Caribe – mainly in the resort areas. The standards and service at these types of places are not unlike resorts in Mexico and the rest of the Caribbean.

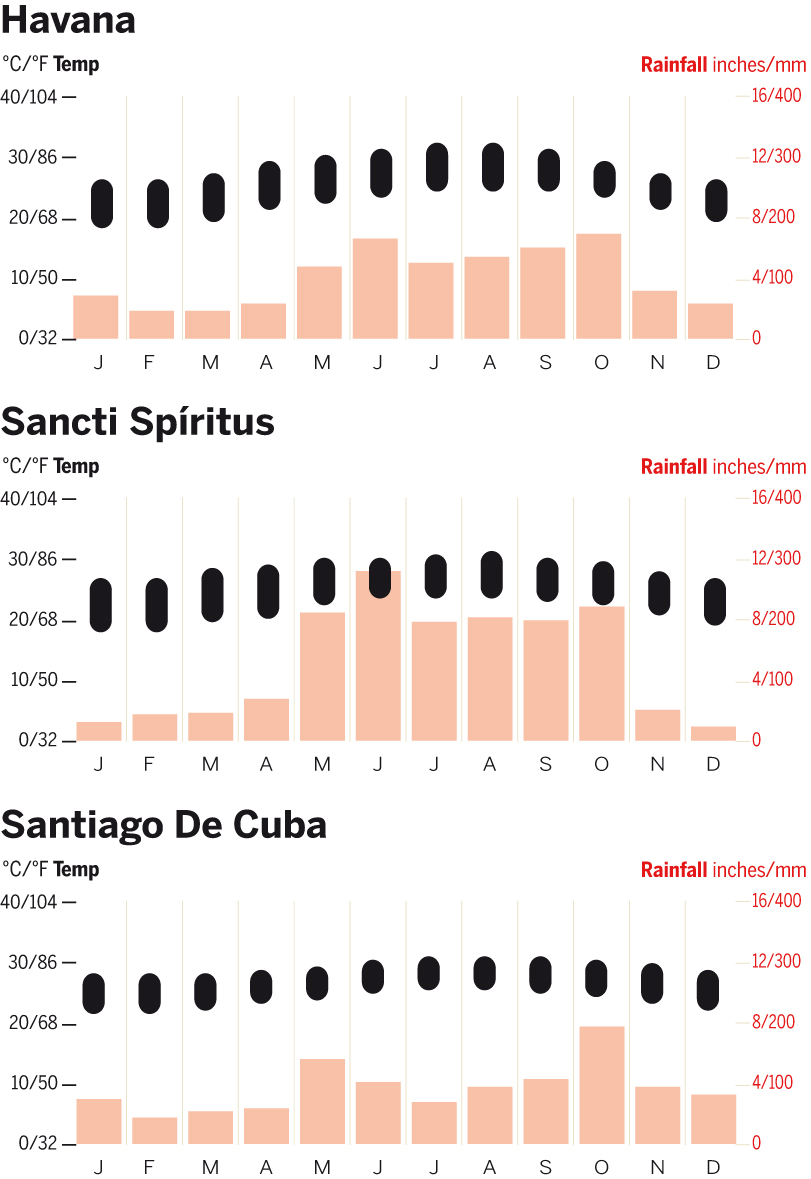

Climate

PRACTICALITIES

Newspapers Three state-controlled, national newspapers: Granma, Juventud Rebelde and Trabajadores.

Smoking Technically banned in enclosed spaces but only sporadically enforced.

TV Five national television channels with some imported foreign shows on the newer Multivisión channel.

Weights & Measures Metric system except in some fruit and vegetable markets where imperial is used.

Customs Regulations

Cuban customs regulations are complicated. For the full up-to-date scoop see www.aduana.co.cu.

Entering Cuba

Travelers are allowed to bring in personal belongings including photography equipment, binoculars, a musical instrument, radio, personal computer, tent, fishing rod, bicycle, canoe and other sporting gear, and up to 10kg of medicines. Canned, processed and dried food are no problem, nor are pets (as long as they have veterinary certification and proof of rabies vaccination).

Items that do not fit into the categories mentioned above are subject to a 100% customs duty to a maximum of CUC$1000.

Items prohibited from entry into Cuba include narcotics, explosives, pornography, electrical appliances broadly defined, light motor vehicles, car engines and products of animal origin.

Leaving Cuba

You are allowed to export 50 boxed cigars duty free (or 23 singles), US$5000 (or equivalent) in cash and only CUC$200.

Exporting undocumented art and items of cultural patrimony is restricted and involves fees. Normally, when you buy art you will be given an official 'seal' at point of sale. Check this before you buy. If you don't get one, you'll need to obtain one from the Registro Nacional de Bienes Culturales (

GOOGLE MAP

; Calle 17 No 1009, btwn Calles 10 & 12, Vedado, Havana; ![]() h9am-noon Mon-Fri) in Havana. Bring the objects here for inspection; fill in a form; pay a fee of between CUC$10 and CUC$30, which covers from one to five pieces of artwork; and return 24 hours later to pick up the certificate.

h9am-noon Mon-Fri) in Havana. Bring the objects here for inspection; fill in a form; pay a fee of between CUC$10 and CUC$30, which covers from one to five pieces of artwork; and return 24 hours later to pick up the certificate.

Travelers should check local import laws in their home country regarding Cuban cigars. Some countries, including Australia, charge duty on imported Cuban cigars

Electricity

The electrical current in Cuba is 110V with 220V in many tourist hotels and resorts.

Embassies & Consulates

All embassies are in Havana, and most are open from 8am to noon on weekdays. Australia is represented in the Canadian Embassy. New Zealand is represented in the UK Embassy. The US is represented by a 'US Interests Section.' Canada has additional consulates in Varadero and Guardalavaca.

Canadian EmbassyEMBASSY

(

GOOGLE MAP

; ![]() %7-204-2516; Calle 30 No 518, Playa)

%7-204-2516; Calle 30 No 518, Playa)

Also represents Australia.

Japanese EmbassyEMBASSY

(

GOOGLE MAP

; ![]() %7-204-3508; Miramar Trade Center, cnr Av 3 & Calle 80, Playa)

%7-204-3508; Miramar Trade Center, cnr Av 3 & Calle 80, Playa)

US Interests SectionEMBASSY

(

GOOGLE MAP

; ![]() %7-839-4100; Calzada, US Interests Section, btwn Calles L & M, Vedado)

%7-839-4100; Calzada, US Interests Section, btwn Calles L & M, Vedado)

Due to become a full-blown embassy when US–Cuba diplomatic ties are restored.

US CITIZENS & CUBA

Technically, Americans aren’t banned from physically traveling to Cuba; rather they are banned from making ‘travel-related transactions’ in the country, a ruling which pretty much amounts to the same thing. The measure was brought into force by President Kennedy in 1961 by invoking the 1917 Trading with the Enemy Act. In theory, breaking this law can land you a $250,000 fine, though prosecutions are rare – and have become rarer since Obama succeeded George W Bush. As a result, many thousands of Americans circumnavigate the law every year by flying to Cuba out of third countries such as Mexico, Canada and the Bahamas. Cuban customs officials don't stamp American passports.

Food

Cuban cuisine – popularly known as comida criollla – has improved immensely since new privatization laws, passed in 2011, inspired a plethora of pioneering restaurants to take root, particularly in Havana. Travel outside the bigger cities, however, and Cuban food can still be limited and insipid (Click here).

EATING PRICE RANGES

It will be a very rare meal in Cuba that costs over CUC$25. Restaurant listings use the following price brackets for meals.

$ less than CUC$7

$$ CUC$7–CUC$15

$$$ more than CUC$15

Where to Eat & Drink

Government-Run Restaurants

Government-run restaurants operate in either moneda nacional or convertibles. Moneda nacional restaurants are nearly always grim and are notorious for handing you a nine-page menu (in Spanish) when the only thing available is fried chicken. There are, however, a few newer exceptions to this rule. Moneda nacional restaurants will normally accept payment in CUC$, though sometimes at an inferior exchange rate to the standard 25 to one.

Restaurants that sell food in convertibles are generally more reliable, but this isn't capitalism: just because you're paying more doesn't necessarily mean better service. Food is often limp and unappetizing and discourse with bored waiters can be worthy of a Monty Python sketch. Things have got progressively better in the last five years. The Palmares group runs a wide variety of excellent restaurants countrywide, from bog-standard beach shacks to the New York Times–lauded El Aljibe in Miramar, Havana. The government-run company Habaguanex operates some of the best restaurants in Cuba in Havana, and Gaviota has recently tarted up some old staples. Employees of state-run restaurants will not earn more than CUC$20 a month (the average Cuban salary), so tips are highly appreciated.

Private Restaurants

First established in 1995 during the economic chaos of the Special Period, private restaurants – formerly known as paladares – owe much of their success to the sharp increase in tourist traffic on the island, coupled with the bold experimentation of local chefs who, despite a paucity of decent ingredients, have heroically managed to keep the age-old traditions of Cuban cooking alive. They have proliferated since new business laws were passed in 2011, especially in Havana. Private-restaurant meals are generally more expensive than their state-run equivalents, costing anything between CUC$8 and CUC$30.

Vegetarians

In a land of rationing and food shortages, strict vegetarians (ie no lard, no meat, no fish) will have a hard time. Cubans don't really understand vegetarianism, and when they do (or when they say they do), it can be summarized rather adroitly with one key word: omelet – or, at a stretch, scrambled eggs. Cooks in casas particulares, who may already have had experience cooking meatless dishes for other travelers, are usually much better at accommodating vegetarians; just ask.

Gay & Lesbian Travelers

While Cuba can't be called a queer destination (yet), it's more tolerant than many other Latin American countries. The hit movie Fresa y Chocolate (Strawberry and Chocolate, 1994) sparked a national dialogue about homosexuality, and Cuba is pretty tolerant, all things considered. People from more accepting societies may find this tolerance too 'don't ask, don't tell' or tokenistic (everybody has a gay friend/relative/coworker, whom they'll mention when the topic arises) but what the hell, you have to start somewhere and Cuba is moving in the right direction.

Lesbianism is less tolerated and seldom discussed and you'll see very little open displays of gay pride between female lovers. There are occasional fiestas para chicas (not necessarily all-girl parties but close); ask around at the Cine Yara in Havana's gay cruising zone.

Cubans are physical with each other and you'll see men hugging, women holding hands and lots of friendly caressing. This type of casual touching shouldn't be a problem, but take care when that hug among friends turns overtly sensual in public.

Health

From a medical point of view, Cuba is generally safe as long as you're reasonably careful about what you eat and drink. The most common travel-related diseases, such as dysentery and hepatitis, are acquired by the consumption of contaminated food and water. Mosquito-borne illnesses are not a significant concern on most of the islands within the Cuban archipelago.

Prevention is the key to staying healthy while traveling around Cuba. Travelers who receive the recommended vaccines and follow commonsense precautions usually come away with nothing more than a little diarrhea.

Insurance

Since May 2010, Cuba has made it obligatory for all foreign visitors to have medical insurance. Random checks are made at the airport, so ensure you bring a printed copy of your policy.

Should you end up in hospital, call Asistur for help with insurance and medical assistance. The company has regional offices in Havana, Varadero, Cayo Coco, Guardalavaca and Santiago de Cuba.

Outpatient treatment at international clinics is reasonably priced, but emergency and prolonged hospitalization gets expensive (the free medical system for Cubans should only be used when there is no other option).

Should you have to purchase medical insurance on arrival, you will pay between CUC$2.50 and CUC$3 per day for coverage of up to CUC$25,000 in medical expenses (for illness) and CUC$10,000 for repatriation of a sick person.

Health Care for Foreigners

The Cuban government has established a for-profit health system for foreigners called Servimed (![]() %7-24-01-41; www.servimedcuba.com), which is entirely separate from the free, not-for-profit system that takes care of Cuban citizens. There are more than 40 Servimed health centers across the island, offering primary care as well as a variety of specialty and high-tech services. If you're staying in a hotel, the usual way to access the system is to ask the manager for a physician referral. Servimed centers accept walk-ins. While Cuban hospitals provide some free emergency treatment for foreigners, this should only be used when there is no other option. Remember that in Cuba medical resources are scarce and the local populace should be given priority in free health-care facilities.

%7-24-01-41; www.servimedcuba.com), which is entirely separate from the free, not-for-profit system that takes care of Cuban citizens. There are more than 40 Servimed health centers across the island, offering primary care as well as a variety of specialty and high-tech services. If you're staying in a hotel, the usual way to access the system is to ask the manager for a physician referral. Servimed centers accept walk-ins. While Cuban hospitals provide some free emergency treatment for foreigners, this should only be used when there is no other option. Remember that in Cuba medical resources are scarce and the local populace should be given priority in free health-care facilities.

Almost all doctors and hospitals expect payment in cash, regardless of whether you have travel health insurance or not. If you develop a life-threatening medical problem, you'll probably want to be evacuated to a country with state-of-the-art medical care. Since this may cost tens of thousands of dollars, be sure you have insurance to cover this before you depart.

There are special pharmacies for foreigners also run by the Servimed system, but all Cuban pharmacies are notoriously short on supplies, including pharmaceuticals. Be sure to bring along adequate quantities of all medications you might need, both prescription and over the counter. Also, be sure to bring along a fully stocked medical kit. Pharmacies marked turno permanente or pilotos are open 24 hours.

Water

Tap water in Cuba is not reliably safe to drink and outbreaks of cholera have been recorded in the past few years. Bottled water called Ciego Montero rarely costs more than CUC$1, but is sometimes not available in small towns. Stock up in the cities when going on long bus or car journeys.

Internet Access

State-run telecommunications company Etecsa has a monopoly as Cuba's internet service provider. For public internet access, you'll have to decamp to one of their Etecsa telepuntos available in almost every provincial town. The drill is to buy a one-hour user card (CUC$4.50) with scratch-off usuario (code) and contraseña (password) and help yourself to an available computer. These cards are interchangeable in any telepunto across the country, so you don't have to use up your whole hour in one go.

The downside of the Etecsa monopoly is that there are few, if any, independent internet cafes outside the telepuntos. As a general rule, most three- to five-star hotels (and all resort hotels) will have their own internet terminals. Usually the terminals in these places are less busy and more reliable than Etecsa, although the fees are often higher (sometimes as much as CUC$12 per hour).

As internet access for Cubans is ostensibly limited, you may be asked to show your passport when using a telepunto (although if you look obviously foreign, they won't bother). On the plus side, the Etecsa places are open long hours and are seldom crowded.

Wi-fi is slowly catching on in Cuba's better hotels. Towns with reasonable wi-fi coverage include Baracoa, Havana and Trinidad. You can use your CUC$4.50 Etecsa card for wi-fi when it is available. Warning: connections are often slow and temperamental.

Language Courses

Cuba's rich cultural tradition and the abundance of highly talented, trained professionals make it a great place to study Spanish. Technological and linguistic glitches, plus general unresponsiveness, make it hard to set up courses before arriving, but you can arrange everything once you get here. In Cuba, things are always better done face to face.

The best official Spanish-language courses are available at Cuba's two leading universities: the Universidad de La Habana and the Universidad Central Marta Abreu de las Villas in Santa Clara. It's useful, though not imperative, to book in advance.

Students heading to Cuba should bring a good bilingual dictionary and a basic 'learn Spanish' textbook, as such books are scarce or expensive in Cuba. You might sign up for a two-week course at a university to get your feet wet and then jump into private classes once you've made some contacts.

Legal Matters

Cuban police are everywhere and they're usually very friendly – more likely to ask you for a date than a bribe. Corruption is a serious offense in Cuba, and typically no one wants to get mixed up in it. Getting caught out without identification is never good; carry some around just in case (a driver's license, a copy of your passport or a student ID card should be sufficient).

Drugs are prohibited in Cuba, though you may still get offered marijuana and cocaine on the streets of Havana. Penalties for buying, selling, holding or taking drugs are serious, and Cuba is making a concerted effort to treat demand and curtail supply; it is only the foolish traveler who partakes while on a Cuban vacation.

Maps

Signage is awful in Cuba, so a good map is essential for drivers and cyclists alike. The comprehensive Guía de Carreteras, published in Italy, includes the best maps available in Cuba. It usually comes free when you hire a car, though some travelers have been asked to pay between CUC$5 and CUC$10. It has a complete index, a detailed Havana map and useful information in English, Spanish, Italian and French. Handier is the all-purpose Automapa Nacional, available at hotel shops and car-rental offices.

The best map published outside Cuba is the Freytag & Berndt 1:1.25 million Cuba map. The island map is good, and it has indexed town plans of Havana, Playas del Este, Varadero, Cienfuegos, Camagüey and Santiago de Cuba.

For good basic maps, pick up one of the provincial Guías available in Infotur offices.

Money

This is a tricky part of any Cuban trip, as the double economy takes some getting used to. As of early 2015, two currencies were still circulating in Cuba: convertible pesos (CUC$) and Cuban pesos (referred to as moneda nacional, abbreviated MN$). Most things tourists pay for are in convertibles (eg accommodation, rental cars, bus tickets, museum admission and internet access). At the time of writing, Cuban pesos were selling at 25 to one convertible, and while there are many things you can't buy with moneda nacional, using them on certain occasions means you'll see a bigger slice of authentic Cuba. The prices we list are in convertibles unless otherwise stated.

Making everything a little more confusing, euros are also accepted at the Varadero, Guardalavaca, Cayo Largo del Sur, Cayo Coco and Cayo Guillermo resorts, but once you leave the resort grounds, you'll still need convertibles.

The best currencies to bring to Cuba are euros, Canadian dollars or pounds sterling. The worst is US dollars, for which you will be penalized with a 10% fee (on top of the normal commission) when you buy convertibles (CUC$). Since 2011, the Cuban convertible has been pegged 1:1 to the US dollar, meaning its rate will fluctuate depending on the strength/weakness of the US dollar. Australian dollars are not accepted anywhere in Cuba.

Cadeca branches in every city and town sell Cuban pesos. You won't need more than CUC$10 worth of pesos a week. There is almost always a branch at the local agropecuario (vegetable market). If you get caught without Cuban pesos and are drooling for that ice-cream cone, you can always use convertibles; in street transactions such as these, CUC$1 is equal to 25 pesos and you'll receive change in pesos. There is no black market in Cuba, only hustlers trying to fleece you with money-changing scams.

CURRENCY UNIFICATION

In October 2013, Raul Castro announced that Cuba would gradually unify its dual currencies (convertibles and moneda nacional). As a result, prices are liable to change. At the time of writing, the unification process had yet to begin and no further details had emerged as to when or how the government will go about implementing the complex changes. Check www.lonelyplanet.com for updates.

ATMs & Credit Cards

The acceptance of credit cards has become more widespread in Cuba in recent years and was aided by the legalization of US and US-linked credit and debit cards in early 2015. When weighing up whether to use a credit card or cash, bear in mind that the charges levied by Cuban banks are similar for both (around 3%). However, your home bank may charge additional fees for ATM/credit-card transactions. Ideally, it is best to arrive in Cuba with a stash of cash and a credit card and debit card as backup. (An increasing number of debit cards work in Cuba, but it's best to check with both your home bank and the local Cuban bank before using them.)

Almost all private business in Cuba (ie casas particulares and private restaurants) is still conducted in cash.

Cash advances can be drawn from credit cards, but the commission is the same. Check with your home bank before you leave, as many banks won't authorize large withdrawals in foreign countries unless you notify them of your travel plans first.

ATMs are becoming more common. They are the equivalent to obtaining a cash advance over the counter. This being Cuba, it is wise to only use ATMs when the bank is open, in case any problems occur.

Cash

Cuba is a cash economy and credit cards don't have the importance or ubiquity that they do elsewhere in the western hemisphere. Although carrying just cash is far riskier than the usual cash/credit-card/debit card mix, it's infinitely more convenient. As long as you use a concealed money belt and keep the cash on you or in your hotel's safety-deposit box at all times, you should be OK.

It's better to ask for CUC$20/10/5/3/1 bills when you're changing money, as many smaller Cuban businesses (taxis, restaurants etc) can't change anything bigger (ie CUC$50 or CUC$100 bills) and the words no hay cambio (no change) echo everywhere. If desperate, you can always break big bills at hotels.

Denominations & Lingo

One of the most confusing parts of a double economy is terminology. Cuban pesos are called moneda nacional (abbreviated MN) or pesos Cubanos or simply pesos, while convertible pesos are called pesos convertibles (abbreviated CUC), or simply pesos (again!). More recently people have been referring to them as cucs. Sometimes you'll be negotiating in pesos Cubanos and your counterpart will be negotiating in pesos convertibles. It doesn't help that the notes look similar as well. Worse, the symbol for both convertibles and Cuban pesos is $. You can imagine the potential scams just working these combinations.

The Cuban peso comes in notes of one, five, 10, 20, 50 and 100 pesos; and coins of one (rare), five and 20 centavos, and one and three pesos. The five-centavo coin is called a medio, the 20-centavo coin a peseta. Centavos are also called kilos.

The convertible peso comes in multicolored notes of one, three, five, 10, 20, 50 and 100 pesos; and coins of five, 10, 25 and 50 centavos, and one peso.

Post

Letters and postcards sent to Europe and the US take about a month to arrive. While sellos (stamps) are sold in Cuban pesos and convertibles, correspondence bearing the latter has a better chance of arriving. Postcards cost CUC$0.65 to all countries. Letters cost CUC$0.65 to the Americas, CUC$0.75 to Europe and CUC$0.85 to all other countries. Prepaid postcards, including international postage, are available at most hotel shops and post offices and are the surest bet for successful delivery. For important mail, you're better off using DHL, which is located in all the major cities; it costs CUC$55 for a 900g letter pack to Australia, or CUC$50 to Europe.

Public Holidays

Officially Cuba has nine public holidays. Other important national days to look out for include January 28 (anniversary of the birth of José Martí); April 19 (Bay of Pigs victory); October 8 (anniversary of the death of Che Guevara); October 28 (anniversary of the death of Camilo Cienfuegos); and December 7 (anniversary of the death of Antonio Maceo).

January 1 Triunfo de la Revolución (Liberation Day)

January 2 Día de la Victoria (Victory of the Armed Forces)

May 1 Día de los Trabajadores (International Worker's Day)

July 25 Commemoration of Moncada Attack

July 26 Día de la Rebeldía Nacional – Commemoration of Moncada Attack

July 27 Commemoration of Moncada Attack

October 10 Día de la Indepedencia (Independence Day)

December 25 Navidad (Christmas Day)

December 31 New Year's Eve

Safe Travel

Cuba is generally safer than most countries, and violent attacks are extremely rare. Petty theft (eg rifled luggage in hotel rooms or unattended shoes disappearing from the beach) is common, but preventative measures work wonders. Pickpocketing is preventable: wear your bag in front of you on crowded buses and at busy markets, and only take what money you'll need when you head out at night.

Begging is more widespread and is exacerbated by tourists who hand out money, soap, pens, chewing gum and other things to people on the street. If you truly want to do something to help, pharmacies and hospitals will accept medicine donations, schools happily take pens, paper, crayons etc, and libraries will gratefully accept books. Alternatively pass stuff onto your casa particular owner or leave it at a local church. Hustlers are called jineteros/jineteras (male/female touts), and can be a real nuisance.

Telephone

The Cuban phone system is still undergoing upgrades, so beware of phone-number changes. Normally a recorded message will inform you of recent upgrades. Most of the country's Etecsa telepuntos have now been completely refurbished, which means there will be a spick-and-span (as well as air-conditioned) phone and internet office in almost every provincial town.

Cell-phone usage has become much more widespread in Cuba in the last few years.

Cell Phones

Cuba's cell-phone company is called Cubacel (www.cubacel.com). You can use your own GSM or TDMA phones in Cuba, though you'll have to pay an activation fee (approximately CUC$30). Cubacel has numerous offices around the country (including at the Havana airport) where you can do this. After this you're looking at between CUC$0.30 to CUC$0.45 per minute for calls within Cuba and CUC$2.45 to CUC$5.85 for international calls. To rent a phone in Cuba costs CUC$6 plus CUC$3 per day activation fee. You'll also need to pay a CUC$100 deposit. Charges after this amount to around CUC$0.35 per minute. For up-to-date costs and information see www.etecsa.cu.

Phone Codes

To call Cuba from abroad, dial your international access code, Cuba’s country code (53), the city or area code (minus the ‘0,’ which is used when dialing domestically between provinces), and the local number.

To call internationally from Cuba, dial Cuba’s international access code (119), the country code, the area code and the number. To the US, you just dial 119, then 1, the area code and the number.

To call cell phone to cell phone just dial the eight-digit number (which always starts with a ‘5’).

To call cell phone to landline dial the provincial code plus the local number.

To call landline to cell phone dial ‘01’ (or ‘0’ if in Havana) followed by the eight-digit cell phone number.

To call landline to landline dial ‘0’ plus the provincial code plus the local number.

Phonecards

Etecsa is where you buy phonecards, use the internet and make international calls. Blue public Etecsa phones accepting magnetized or computer-chip cards are everywhere. The cards are sold in convertibles (CUC$5, CUC$10 and CUC$20), and in moneda nacional (five and 10 pesos). You can call nationally with either, but you can call internationally only with convertible cards.

You will also see coin-operated phone booths good for Cuban pesos (moneda nacional) only.

Phone Rates

Local calls cost from five centavos per minute and will vary with time of day and distance, while interprovincial calls cost from around CUC$1.40 per minute (note that only the peso coins with the star work in pay phones). Since most coin phones don't return change, common courtesy means that you should push the 'R' button so that the next person in line can make their call with your remaining money.

International calls made with a card cost from CUC$2 per minute to the US and Canada and CUC$5 to Europe and Oceania. Calls placed through an operator cost slightly more.

Hotels with three stars and up usually offer slightly pricier international phone rates.

Tourist Information

Cuba's official tourist information bureau is called Infotur (www.infotur.cu). It has offices in all the main provincial towns and desks in most of the bigger hotels and airports. Travel agencies, such as Cubanacán, Cubatur, Gaviota and Ecotur can usually supply some general information.

Travelers with Disabilities

Cuba's inclusive culture extends to disabled travelers, and while facilities may be lacking, the generous nature of Cubans generally compensates. Sight-impaired travelers will be helped across streets and given priority in lines. The same holds true for travelers in wheelchairs, who will find the few ramps ridiculously steep and will have trouble in colonial parts of town where sidewalks are narrow and streets are cobblestone. Elevators are often out of order. Etecsa phone centers have telephone equipment for the hearing-impaired, and TV programs are broadcast with closed captioning.

Visas & Tourist Cards

Regular tourists who plan to spend up to two months in Cuba do not need visas. Instead, you get a tarjeta de turista (tourist card) valid for 30 days, which can be extended once you're in Cuba (Canadians get 90 days plus the option of a 90-day extension). Package tourists receive their card with their other travel documents. Those going 'air only' usually buy the tourist card from the travel agency or airline office that sells them the plane ticket, but policies vary (eg Canadian airlines give out tourist cards on their airplanes), so you'll need to check ahead with the airline office via phone or email. In some cases, you may be required to buy and/or pick up the card at your departure airport. Some independent travelers have been denied access to Cuba flights because they inadvertently haven't obtained a tourist card.

Once in Havana, tourist-card extensions or replacements cost another CUC$25. You cannot leave Cuba without presenting your tourist card. If you lose it, you can expect to face at least a day of frustrating Cuba-style bureaucracy to get it replaced.

You are not permitted entry to Cuba without an onward ticket.

Fill the tourist card out clearly and carefully, as Cuban customs are particularly fussy about crossings out and illegibility.

Business travelers and journalists need visas. Applications should be made through a consulate at least three weeks in advance (longer if you apply through a consulate in a country other than your own).

Visitors with visas or anyone who has stayed in Cuba longer than 90 days must apply for an exit permit from an immigration office. The Cuban consulate in London issues official visas (£32 plus two photos). They take two weeks to process, and the name of an official contact in Cuba is necessary.

Licenses for US Visitors

The US government issues two sorts of licenses for travel to Cuba: ‘specific’ and ‘general.’ Specific licenses require a lengthy and sometimes complicated application process and are considered on a case-by-case basis; it is recommended that you apply at least 45 days before your intended date of departure. General licenses are self-qualifying.

Supporting documentation to back up your claim must be sent to an authorized travel-service provider when you book your flight ticket. The nature of this documentation will vary depending on which category you fall into. To minimise bogus claims, travel service providers require all US travelers to sign a ‘travel affidavit’ (a sworn statement) which may be viewed by US immigration officials when returning from Cuba. Check with the US Department of the Treasury (www.treasury.gov/resource-center/sanctions/Programs/pages/cuba.aspx) to see if you qualify for a license.

Extensions

For most travelers, obtaining an extension once in Cuba is easy: you just go to the inmigración (immigration office) and present your documents and CUC$25 in stamps. Obtain these stamps from a branch of Bandec or Banco Financiero Internacional beforehand. You'll only receive an additional 30 days after your original 30 days (apart from Canadians who get an additional 90 days after their original 90), but you can exit and re-enter the country for 24 hours and start over again (some travel agencies in Havana have special deals for this type of trip). Attend to extensions at least a few business days before your visa is due to expire and never attempt travel around Cuba with an expired visa.

Cuban Immigration Offices

Nearly all provincial towns have an immigration office (where you can extend your visa), though the staff rarely speak English and aren't always overly helpful. Try to avoid Havana's office if you can, as it gets ridiculously crowded. Hours are normally 8am to 7pm Monday, Wednesday and Friday, 8am to 5pm Tuesday, 8am to noon Thursday and Saturday.

Immigration OfficeIMMIGRATION

(Antonio Maceo No 48, Baracoa)

Immigration OfficeIMMIGRATION

( GOOGLE MAP ; Carretera Central, Km 2, Bayamo)

In a big complex 200m south of the Hotel Sierra Maestra.

Immigration OfficeIMMIGRATION

( GOOGLE MAP ; Calle 3 No 156, btwn Calles 8 & 10, Reparto Vista Hermosa, Camagüey)

Immigration OfficeIMMIGRATION

( GOOGLE MAP ; Calle 1 Oeste, btwn Calles 14 & 15 Norte, Guantánamo)

Directly behind Hotel Guantánamo.

Immigration OfficeIMMIGRATION

( GOOGLE MAP ; Calle Fomento No 256 cnr Peralejo, Holguín)

Arrive early – it gets crowded here.

Immigration OfficeIMMIGRATION

( GOOGLE MAP ; Av Camilo Cienfuegos, Reparto Buenavista, Las Tunas)

Northeast of the train station.

Immigration OfficeIMMIGRATION

(

GOOGLE MAP

; ![]() %41-32-47-29; Independencia Norte No 107, Sancti Spíritus)

%41-32-47-29; Independencia Norte No 107, Sancti Spíritus)

Immigration OfficeIMMIGRATION

( GOOGLE MAP ; cnr Av Sandino & Sexta, Santa Clara)

Three blocks east of Estadio Sandino.

Immigration OfficeIMMIGRATION

(

GOOGLE MAP

; ![]() %22-65-75-07; Av Pujol No 10, btwn Calle 10 & Anacaona)

%22-65-75-07; Av Pujol No 10, btwn Calle 10 & Anacaona)

Stamps for visa extensions are sold at the Banco de Crédito y Comercio at Felix Peña No 614 on Parque Céspedes.

Volunteering

There are a number of bodies offering volunteer work in Cuba, though it is always best to organize things in your home country first. Just turning up in Havana and volunteering can be difficult, if not impossible.

Canada-Cuba Farmer to Farmer ProjectVOLUNTEERING

Vancouver-based sustainable agriculture organization.

Witness for PeaceVOLUNTEERING

Looking for Spanish-speakers with a two-year commitment.

Women Travelers

In terms of physical safety, Cuba is a dream destination for women travelers. Most streets can be walked alone at night, violent crime is rare and the chivalrous part of machismo means you'll never step into oncoming traffic. But machismo cuts both ways, protecting on one side and pursuing – relentlessly – on the other. Cuban women are used to piropos (the whistles, kissing sounds and compliments constantly ringing in their ears), and might even reply with their own if they're feeling frisky. For foreign women, however, it can feel like an invasion.

Ignoring piropos is the first step. But sometimes ignoring isn't enough. Learn some rejoinders in Spanish so you can shut men up. No me moleste (don't bother me), está bueno ya (all right already) or que falta respeto (how disrespectful) are good ones, as is the withering 'don't you dare' stare that is also part of the Cuban woman's arsenal. Wearing plain, modest clothes might help lessen unwanted attention; topless sunbathing is out. An absent husband, invented or not, seldom has any effect. If you go to a disco, be very clear with Cuban dance partners what you are and are not interested in.