Bones

What is a bone?

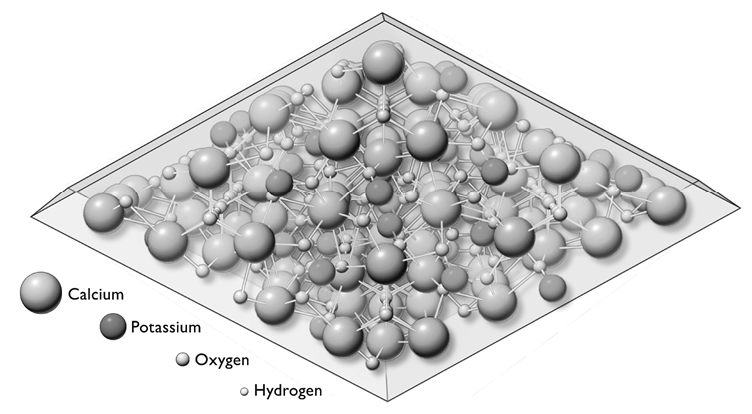

The tissue comprising bone has two components: a protein matrix or osteoid, which is produced by osteocytes, and the mineral elements that become lodged within it. The mineral elements are chiefly calcium and phosphate. There are smaller amounts of bicarbonate, citrate, potassium, sodium, and magnesium. Each element is replaced periodically.

The minerals calcium and phosphate form a crystal-like structure, hydroxyapatite, with chemical formula Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2.

Figure 7. The hydroxyapatite crystals function in bone just as metal reinforcement bars do in concrete. A coating of water surrounding the crystals of calcium and phosphate enables them to pass in and out of the bloodstream. After M. I. Kay, R. A. Young, and A. S. Pesner, “Crystal Structure of Hydroxyapatite,” Nature 204 (December 1964): 1050–1052, used with permission of Sigma=Aldrich Company, St. Louis, Missouri.

Both protein and mineral elements are necessary for bones to have their essential characteristics. We can understand the function of these elements by observing what happens when they are missing. In osteomalacia, a disease in which bones do not have enough calcium, the bones are soft and bending, not supportive. When the protein elements are removed experimentally from normal bones, they crumble like chalk.

There are a number of subtle balances here, too. Even the metabolic process has a requisite speed. Protein’s life cycle has its own timing, like the tempering of steel. When the process is hurried, problems occur, as in an unusual medical condition, osteitis fibrosa cystica, which results in fibrous bones. Failure of a child’s bones to pick up adequate minerals from the available dietary sources or from the bloodstream results in rickets, bones that bend under the strains of daily life.

As already mentioned, adults who are losing boney mineral have osteomalacia, too little calcium per volume of bone. But too much calcium, which results in the condition osteopetrosis, isn’t good either—the marrow cavities where blood cells are made become narrow and are eventually obliterated, leading to anemia that may be fatal.

Too little protein and inadequate mineral content have effects similar to osteoporosis: the chances of fracture increase. But neither condition is the same as osteoporosis, where the proportions of protein and mineral in the bone are well-balanced, there are just less of them. But there is more to the story of bones than their composition. Another important contrast highlights a critical characteristic of almost every bone.

The Structure of Bone

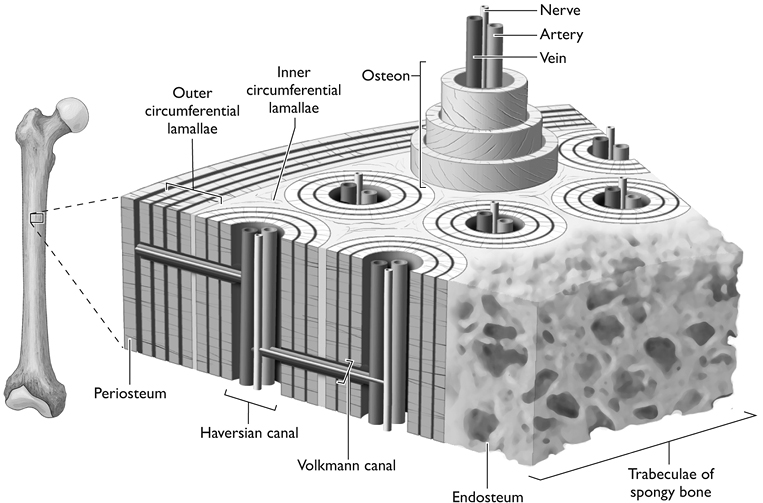

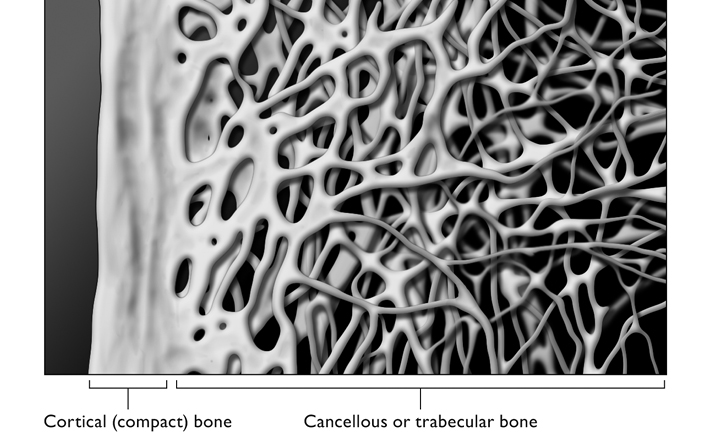

We know that osteoid and minerals make up the basic substance of bone, but what form do these elements take? We know what bones are made of, but how are they constructed? Bones actually have two distinct parts. The compact part, the cortex or cortical bone, forms a hard shell just below the surface. The spongy part, the cancellous or trabecular bone, lies deeper within. The strength of each varies along with the proportions of its two main components, the protein spicules that make up the matrix, and the calcium and other minerals that are attracted to the matrix and harden it. Both are composed of the same osteoid matrix and hydroxyapatite core, but they are different.

Cortical bone forms a hard outer ring and constitutes a large part of any bone’s strength. While there are variations in the mineral content of cortical bone, it is more or less the same thickness, and has essentially the same form in just about everyone.

Although there are certainly variations in the consistency and strength of cortical bone, by far the greater variations appear to be within the trabecular region, with its variably formed and differently angled inner struts and latticework. Bone density is responsible for only 60 percent of bone strength and consequent likelihood of fracture. The other 40 percent appears to be due to the formations of the trabecular bone.1

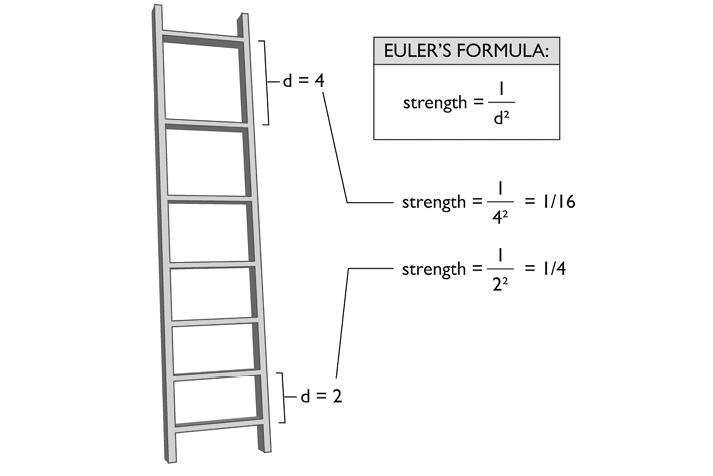

The strength of this structural formation may be calculated by a formula developed by the great Swiss mathematician Leonhard Euler (1707–1783). Euler’s buckling theory states that the strength of a vertically compressed strut is inversely proportional to the square of the unsupported length, that is, the distance between its transverse struts.2

Both the mineral content and the geometric conformation of the elements contribute to what is known as bone quality. Quality enters into any logical assessment of bone strength: Two bones of the same density may be structured differently. You don’t need a degree from MIT to know that the George Washington Bridge can support more weight than a helter-skelter pile of the same materials.

At this writing, what determines a bone’s structure, and what might change it, are not precisely known. But a good deal of research is focused on finding the answer. Certain genetic, environmental, hormonal, drug-related, and dietary influences are already known,3 but any notions of the precise ways to influence bone quality are largely hypotheses in the minds of scientists, physicians, and yogis.

The fracture risk inherent in bone is determined by two physical factors: bone density and bone quality. Bone density is well understood and can be accurately measured. Bone quality is currently under intense investigation. Considerations such as mental status, activity level, and environmental factors—stairs and rugs in the home, slippery surfaces, and occupation—are all relevant, but currently, all other things being equal, the most reliable test we have for the risk of fractures is still the DEXA scan for bone mineral density.

Until recently, the only way to assess overall bone quality was to take a biopsy. The high cost of a biopsy and its invasive nature discouraged its use in the general population. But a virtual bone biopsy, a noninvasive tool for bone quality assessment, is already being tested. Micro-MRI studies find striking differences between different individual’s bones, and these differences are almost sure to relate to the bones’ strength.4

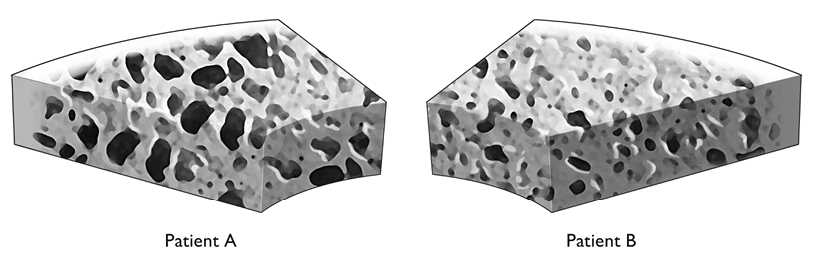

The virtual bone biopsy may be an important tool in monitoring patient treatment. Figure 10 shows the structural images of bones from two women who have similar DEXA T-scores, yet quite different trabecular bone structure. The current standard practice would have both women receive the same treatment. However, the structural characteristics of the bones, determined by the virtual assay and computed along the lines of Euler’s formula, suggest that Patient A may be at a significantly higher risk for fractures. If that is the case, then the nature and intensity of the treatment of these two patients should be adjusted accordingly. If both patients are receiving the same treatment, we may speculate that Patient A is not receiving the aggressive treatment she truly needs. Patient B may be suffering needlessly from the side effects of medications she doesn’t require.

How Bones Grow

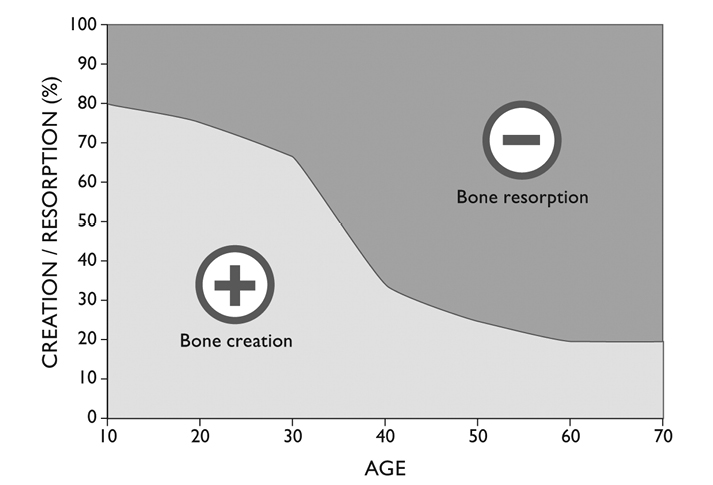

Bones begin to develop long before an infant leaves the womb, lengthening until approximately age 17, and strengthening until age 25 or 30. Although the length of bones does not change significantly after age 30, their strength declines as hormones change in midlife; that decline tapers off after age 65.5 While bone loss actually slows down after 65, this inexorable cumulative bone loss is responsible for most osteoporosis.

All bones, long or short, round or flat, men’s or women’s, are constantly subject to two processes: one builds up their mass and strength, and one eats their substance away. Like just about every tissue in the body, and the quiet imperishable quality of life itself, there is an incessant metabolism, a constant flux of the constituents of bone.

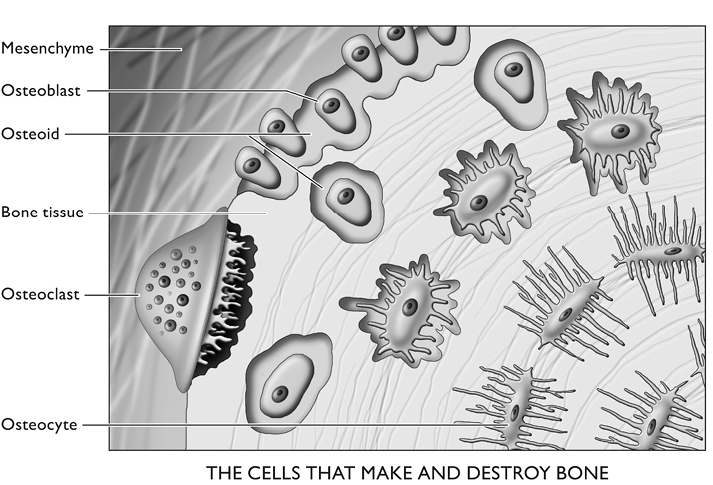

There are the osteoblasts, which are themselves derived from cartilage-making cells, the chondrocytes. These cells secrete collagen, proteoglycans, and glycoproteins that form a woven organic fabric of proteins, the aforementioned osteoid. The matrix then attracts calcium and phosphates to make up the molecule hydroxyapatite (see figure 7). Some of the flat bones spring directly from osteoblasts’ secretions; other bones, the long bones of the arms and legs, first appear in small cartilaginous forms that subsequently ossify.

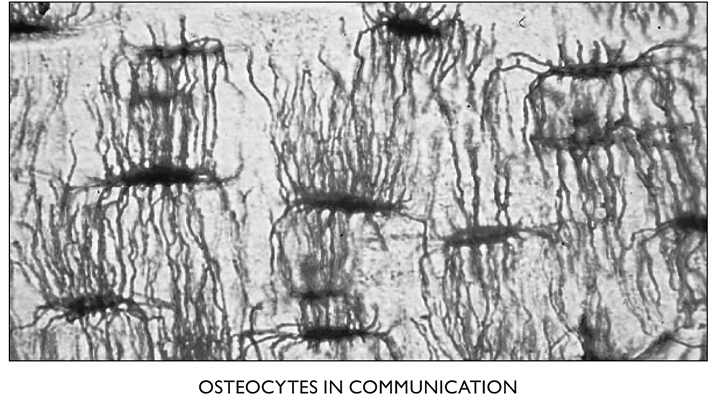

The osteoblasts form a thin lining around the bones until they incorporate themselves into it. At that point they become osteocytes. They change shape, from rectangular to star-shaped, with long thin tendrils that connect to other osteocytes. Ultimately, the first ones in these lines of connected cells link up to a blood vessel—one of the tiny capillaries—for exchange of nutrients and the products of metabolism. It is believed that a chain of as many as 15 osteocytes can effectively transport substances to and from the one that’s farthest from the central canal containing a blood vessel and a nerve.

Figure 12. Ovoid osteoblasts turn into the star-shaped osteocytes as they surround themselves with the protein they synthesize. The process is complete when minerals are attracted to their secretion, turning it into bone, within which the osteocytes soon find themselves deeply embedded. Osteoclasts reabsorb diseased and dying fragments of bone. After Junqueira and Carniero, p. 142, with permission of the publisher.

The metamorphoses of osteoblasts, the cells they come from (chondrocytes), and the cells they may become (osteocytes) are all sensitive to a number of hormonal influences—progesterone, estrogen, testosterone, growth hormone, thyroid hormones, and parathyroid hormone all play a role. We will come to them soon. This controlled conversion has one more relevant participant, osteoclasts, which are responsible for a different, antagonistic process.

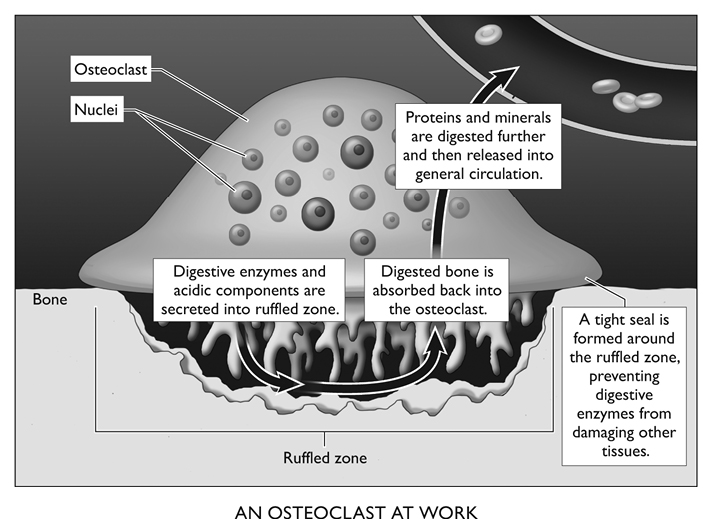

Osteoclasts are strange and gigantic cells, derived from bone marrow, that can often have more than 50 nuclei. They literally digest bone, sending the protein and minerals they swallow back into the bloodstream. They are attracted to injured and old sections of bone and to places where the supporting osteocytes have died, leaving a region of bone unattended. Not unlike a moray eel, they fasten themselves tightly to the affected bone through their “ruffled zone,” a tightly walled-off space into which they send collagenase, other digestive enzymes, and acidic components. This caustic cocktail decomposes the bone. After absorption into the osteoclast, the protein is digested further, and then its components, along with the minerals, are released back into the body’s general circulation.

Figure 14. Many nuclei are found in one osteoclast, probably because so many diverse tasks must be completed to undo the body’s work of crafting bone. These complex cells can undo a skeleton that could otherwise endure thousands of years of wind and weather.

From Junqueira and Carniero, p. 143, with permission of the publisher.

Many factors affect the behavior of osteoclasts. Some are relatively simple. Osteoclasts are inhibited by calcitonin, a hormone secreted by the thyroid gland. Parathyroid hormone, on the other hand, has contradictory effects: this hormone stimulates osteocytes, the osteoclasts’ competitor, activating them so that they produce more protein and secrete a molecule that arouses the osteoclasts. Therefore, a parathyroid hormone directly stimulates the -blasts and indirectly stimulates the -clasts, an intercellular system of checks and balances.

Balance: The Elusive Key

What governs the all-important rates of the two processes of bone creation and resorption? There are a number of factors that are not fully understood. We do know enough, however, to appreciate the complexity of the relationship and to explore some ways to manipulate the processes in our bones’ favor. For example, at low blood serum levels, parathyroid hormone stimulates bone-building osteocytes, but at higher concentrations it reduces the mineral content of the forearm bones.6 Phosphorus gets into the act as well, but too much phosphate will change the absorption of calcium. This in turn will alter parathyroid hormone levels, which will then feed back to change absorption yet again.

These seemingly opposed biologic processes cooperate beautifully under normal circumstances. Atomic force microscopic studies, finer than electron microscopy for these purposes, have seen osteoclasts munching away at corners of bone where microcracks have appeared. This suggests that at the “local level” osteoclasts are drawn to these defects (by a process we do not presently understand) and begin to create excavation sites at which bone resorption is taking place. The calcium thus reclaimed is free for the osteocytes to pick out of the bloodstream to re-create healthy bone at spots where it had been damaged.7

Research has uncovered this critical aspect of inborn maintenance capacity: When osteocytes die, the adjacent bone regions are no longer supported, and the tissue becomes resorbed by the osteoclasts. There are definite chemical signals for this clean-up operation, and different factors maintain the status quo, keeping osteoclastic activity at bay. Balancing and regulating these processes is the principal way in which many of the anti-osteoporosis drugs work. One must be aware of these checks and balances and some of their advantages to appreciate the rewards and risks of using the drugs. Before considering the treatment, though, it makes sense to look at the disease: What makes bones brittle in the first place?