1

Retail Reform

On a May evening in Philadelphia in 1914, the carriage carrying Russell Conwell and John Wanamaker crawled along a three-mile parade route linking Conwell’s Broad Street home to the Academy of Music, the home of the city’s symphony orchestra. A large crowd had gathered along the street to celebrate the lawyer turned Baptist minister, founder of Temple University, and first president of the Samaritan Hospital.1 On this night, Conwell would present his wildly popular lecture “Acres of Diamonds” for the five thousandth time to an eager audience of three thousand.2 Providing the introductory remarks for this grand occasion was Conwell’s fellow philanthropist and friend of more than thirty years, John Wanamaker.

Before moving to Philadelphia in 1882, Conwell had gained fame as an orator on the Chautauqua circuit and speaking at churches. He had delivered “Acres of Diamonds” across the country to eager audiences who wanted to reconcile their Protestant theology with their changing economic circumstances. The growth of commerce and industry opened the way not only to financial security but to affluence. A growing middle class needed a new way to think about money unencumbered by Protestantism’s negative interpretation of wealth.

In “Acres of Diamonds,” Conwell advanced the surprising message that seeking wealth was neither a sign of greed nor the root of evil. Instead, it was a godly pursuit. He passionately told his listeners, “I say that you ought to get rich, it is your duty to get rich. . . . Because to make money is to honestly preach the Gospel.”3 He spoke plainly of the advantages of money, linking it to the prosperity of churches and reminding audiences, “Money is power, and you ought to be reasonably ambitious to have it. You ought because you can do more good with it than you could without it.” Indeed, money supported evangelism, he pointed out: “Money printed your Bible, money builds your churches, money sends your missionaries, and money pays your preachers, and you would not have many of them, either, if you did not pay them.” Money underwrote the church and its outreach.

Conwell’s lecture marked a startling transformation in tone among Protestants. He promoted the accrual of riches as a reform tool, which he claimed Jesus would wholeheartedly approve. Speaking of assumptions that piety and affluence were mutually exclusive, he pointedly told his audiences that to say “‘I do not want money,’ is to say, ‘I do not wish to do any good to my fellowmen.’” He instructed his followers to pursue prosperity in an honest, morally upright way. And he warned them, “It is an awful mistake” to believe that you have to be “awfully poor in order to be pious.”4 You could be pious and rich. A strong work ethic combined with moral living would be rewarded by God. Becoming wealthy demonstrated God’s approval and allowed one to do more of God’s work. This idea, which would later become known as the “prosperity gospel,” was part of a larger movement that emphasized individualism and the “self-made man,” and altered the relationship between business and Christianity in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Material goods played a key role in Conwell’s message—prosperity was expressed by accumulation and quality of goods. It was natural for Wanamaker and other prosperity gospel adherents to turn to aesthetics as an expression of God’s blessing and as an educational tool.

John Wanamaker epitomized Conwell’s gospel.5 Although Conwell was a Baptist and Wanamaker was a Presbyterian, they shared a theological perspective that spanned denominational divides. Conwell’s concept of money and wealth provided Wanamaker and other Protestant entrepreneurs a much-needed positive interpretation of their dizzying success and helped him make sense of how to be deeply religious and prosperous at business. It also explained why he spent his money both to purchase luxury goods and to build institutions that served the poor.

Wanamaker never grew tired of Conwell’s “Acres of Diamonds.” He published dozens of editions of the speech at his printing press. The lecture helped him make sense of his world and he wanted others to learn it. It bridged the worlds of religion and commerce. For the six thousandth delivery of the lecture, Conwell gave the speech at the store’s radio station. Wanamaker’s treasured religious philosophy of material wealth radiated from the store for hundreds of miles.

“A Country Boy”

It is hard to say how much Wanamaker and his biographers embellished the details of his early life. His version of the story emphasized how hard work, moral fortitude, and Christian devotion resulted in social mobility and impressive economic success. He cast himself as a “self-made man” straight from a Horatio Alger novel.6 His early biographers, many of them friends and admirers, perpetuated this image with their laudatory accounts produced shortly after his death in 1922.

During his life, Wanamaker presented his biography—long used as part of the advertising for the store—to help establish the moral character of his department store.7 His personal stories emphasized his hardworking, religiously devout brickmaking family and the simplicity of living among the riverside marshes and farms of Philadelphia in an unexpected juxtaposition of country and city life.8 The virtues of hard work, mutual support, loyalty, and sacrifice, mixed in with familial devotion, served as signposts of Wanamaker’s character.

Born to Nelson and Elizabeth Wanamaker in the summer of 1838, the first year of a crushing economic depression that gripped the nation, John Wanamaker was the oldest boy of six children and was named after his grandfather.9 His father and grandfather before him were brickmakers, sharing a small brickyard in the South Philadelphia neighborhood of Grays Ferry.10 His mother, Elizabeth, the daughter of a local farmer and described as a descendent of French Huguenots, was a deeply religious woman who “communed with God, and to this end, she was regular and diligent in her readings and devotions.”11 Her uncle ran the local inn, the Kochersperger Hotel.12 Grays Ferry sat between South Street and the Schuylkill River on one side and the Delaware River on the other. In the early and mid-nineteenth century, it was home to various light industries, including leather tanning, lime burning, lumber, and fertilizer and chemical companies. Of the nine Philadelphia brickmakers listed in the McElroy Business Directory of 1859, six of them made their home in Grays Ferry, in part because of the high clay content in the soil—an essential element for making bricks.13 The area also was home to a number of small farms and the impressive Naval Home, a hospital for disabled veterans modeled after a Greek temple in Athens.14

A marshy rural area, Grays Ferry was sparsely populated compared to bustling downtown Philadelphia. It formed one of the many “island” neighborhoods that made up American cities in the early nineteenth century.15 Perhaps not surprisingly, Wanamaker liked to call himself “a country boy” and liked to recount childhood memories of fishing, catching frogs, and frolicking with friends among the fields and marshes.16 However, the extent of his modest upbringing remains uncertain. Wanamaker mentions that his birth took place in a house on a small farm initially belonging to his mother’s family. His adult descriptions of his childhood home were thoroughly Victorian—the home was a bright and cheery oasis ruled by his devoted mother. In a store advertisement, he sweetly described it as “a little white house with its green shutters and a small garden of marigolds and hollyhocks.” It is most likely that the Wanamakers were decidedly working middle-class, although unstable in their social ranking.17

One of the challenges of living in Grays Ferry was its lack of schools. At best, a child’s formal schooling was occasional in the mid-nineteenth century. Families frequently relied on their children to provide labor on farms and in family businesses, making regular school attendance challenging. A lack of accessible schools compounded the problem. At the age of ten, John received his first taste of organized education when a small schoolhouse was set up at the edge of his family’s brickyard for the neighborhood children.18 However, the schoolmaster meted out blows with his spelling lessons, making John’s schoolhouse experiences stressful.

Over two winters starting in 1847, Trinity Lutheran Church surveyed the Grays Ferry neighborhood for the establishment of a mission Sunday school. During this period, churches started mission Sunday schools to serve poor urban areas and provided moral education and lessons in reading and writing rooted in the Bible.19 A local farming family, the Landreths, offered an empty house for the school, and one of the workers from the church, John A. Neff, became its superintendent. John Wanamaker’s father, Nelson Wanamaker, and his grandfather, John Sr., a longtime Methodist lay preacher, volunteered to teach Sunday school classes. Later in life, he claimed “the Sunday School as the principal educator of my life” and the Bible as the source for “knowledge not to be obtained elsewhere, which established and developed fixed principles.”20 Wanamaker also kept busy at the family business, where he turned bricks to dry in the yard with his brothers.

Grays Ferry did not remain bucolic. The fields and marshes Wanamaker fondly recalled gave way to increasing industrialization, pushing out longtime residents. The routing of new rail lines through other parts of the city isolated Grays Ferry from the wave of new economic development springing up in Philadelphia.21 Competition increased as larger brickyards swallowed up small, family-run businesses. Racial tensions grew between workers as opportunities for work became competitive. Long an abolitionist, John Sr. employed free and formerly enslaved African Americans in his brickyards despite protests and sporadic attacks by white workers.22 Unemployed men started gangs, and young local ruffians began roaming the streets to stir up mischief.23 By 1850, John Sr. looked for an escape for his extended family from the deteriorating area and struck upon the idea of moving to Indiana to be near his father’s family. Nelson and Elizabeth followed with their five children, moving into a homesteader log cabin on an isolated farm of about 250 acres located seven miles from Leesburg, Indiana.24 But homesteading through Indiana’s harsh winters offered a harder life than Grays Ferry. John Sr.’s sudden death sealed the fate of the pioneer adventure. The Wanamaker family returned to Philadelphia, buying back the old business to take up brickmaking once more, first living in Grays Ferry and later moving to a home on Lombard Street, closer to the center of town.25

Upwardly Mobile

John Wanamaker grew up in a swiftly changing country. At the point his family headed to Indiana to improve their fortunes, other Americans left their homes searching for new opportunities. Some moved west to try their luck at homesteading, farming, or getting rich in one of the gold rushes. Others made their way to cities lured by steady jobs and paychecks, leaving the fickleness of agriculture and small-town life behind.

Philadelphia bustled with growth and activity throughout the nineteenth century. By the late nineteenth century, it served as a publishing, finance, and manufacturing hub.26 The city had experienced rapid development earlier than other cities.27 Its growth spurt began in the antebellum period and continued through the early part of the twentieth century, making it one of the wealthiest and largest cities in the country by 1920.28

It was a religious center for the nation as well. Not only did Philadelphia remain an anchor for the Quakers, but it was also the home of the mother diocese of the Episcopal Church, the birthplace of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, and one of the first places Catholics openly worshipped in the American colonies.29 The first presbytery in the United States started in the city, making it a center for Presbyterianism. Two major synagogues were established in the eighteenth century, giving Judaism an early foothold that allowed it to prosper in the city. Later, Philadelphia became the headquarters for a number of national religious organizations, agencies, and boards.30 And like other major American cities, Philadelphia experienced the complex problems and conflicts of rapid urban growth.

An embrace of innovative technology and transportation spurred Philadelphia’s expansion.31 Situated on two rivers with ocean access, the city augmented its transportation system with the construction of a series of canals. The arrival of railroads connected Philadelphia and New York with a growing network of cities on the Eastern Seaboard. Philadelphia was especially adept at constructing an urban transportation infrastructure.32 The establishment of a streetcar system allowed urban workers to live farther afield and increased the city’s footprint. Telegraph wires went up in 1845 and quickly expanded. The emergence of Philadelphia’s industrial center in the 1850s led to a remarkably diverse set of industries and businesses, including heavy manufacturing, steel, textile production, pharmaceuticals, and chemicals. Cheaper transportation meant cheaper consumer goods, so items such as household furnishings became affordable to a growing middle class.33 At the same time, wealth became more widespread with an increase in industrial and especially white-collar jobs, allowing individuals and families to buy more goods than what was essential. The time was ripe for new developments in retail to meet the changing needs.

For the Wanamakers, the move to Indiana and back did not improve their financial situation. While his parents wanted to educate their children, a lack of schools and the family’s financial distress made it necessary for thirteen-year-old John to find a job to help support the family. Nelson and Elizabeth hoped for a position for their son outside the brickyards. Using their religious ties, they consulted with John Neff, who had been the superintendent of the Landreth Mission Sunday School. Wanamaker’s mother implored Neff, “I want you to find my John a good place in a good store; somewhere near where you are so that you can keep an eye on him.”34 Neff suggested that Wanamaker accept the opportunity to be an errand boy first at a bookseller and later at a law firm.35 By the next year, John had moved from being an errand boy to sweeping floors and dusting mannequins at a dry goods store—a shop that carried a variety of nonliquid (that is, dry) goods, including textiles, and that became an early model for emerging department stores.36 His parents’ vision of upward mobility for their oldest son was a propelling force in John Wanamaker’s life, and he would later interpret his stint at the dry goods store as a source of his interest in retail.37

Despite what he described later in life as a limited education, Wanamaker proved to be a fast learner with an entrepreneurial streak. He grew restless as a store janitor and began to develop ideas for improving the store’s business. He already knew he wanted to be a successful merchant and decided to find a job at one of the city’s larger retail establishments. Wanamaker set his sights on a job at Tower Hall, a leading men’s clothier in downtown Philadelphia specializing in men’s ready-to-wear clothing. An up-and-coming trend, “ready-made” or “ready-to-wear” clothing was still a novelty at a time when customers typically made their clothes at home or had them made by dressmakers or tailors.38 Tower Hall was one of many businesses changing the way people dressed and shopped. It was a shift away from businesses that sold the materials to produce goods at home to purchasing items created in a factory. Tower Hall’s proprietor, Colonel Joseph N. Bennett, a man often described as eccentric, hired the young Wanamaker because he had known John’s grandfather well.39

Wanamaker wanted to learn how to sell. However, Bennett assigned him menial tasks as his first jobs around Tower Hall. Perhaps sensing that it was a test, Wanamaker enthusiastically performed small jobs. In an effort to prove himself, he polished the brass doorknobs of the store until they gleamed. Bennett took a liking to the young man, recalling years later, “He was the most ambitious boy I had ever met.” Wanamaker repeatedly told Bennett that “he was going to be a great merchant someday.”40 In particular, Bennett admired John for his “natural born” organizational abilities, saying, “He was always organizing something.”41

For the next three years, Bennett tutored Wanamaker on the ins and outs of the retail business, from managing stock to sales to buying the store’s inventory. His apprenticeship at Tower Hall put him into a relatively small pool of white-collar workers that in a few short decades would grow exponentially into the thousands. In those early years, a white-collar salesman possessed a set of skills that placed him in an elite group of workers. Many of these young men would take their leap into business, founding what would become thriving dry goods and wholesale businesses in America’s booming cities.

“A Religion to Live By”

Elizabeth Wanamaker had wanted her oldest son to be a minister.42 Wanamaker recalled, “My first love was my mother. . . . Leaning little arms upon her knees, I learned my first prayers.”43 Church and Sunday school were constants throughout his boyhood. But it was not until Wanamaker’s late teens that the religious devotion of his family became fully his own. He started attending worship services at First Independent Church at the corner of Broad and Sansom Streets on the edge of town, where the well-liked Irish preacher, the Reverend John Chambers, was known for his creative and sometimes rebellious approach to ministry.

Chambers started First Independent when local Presbyterians refused to ordain him for his “unorthodox” views.44 He opened a new church, and in another maverick move, Chambers advertised worship times and his sermon titles in the newspaper. Like many Protestant leaders in the mid-nineteenth century, he preached a message that increasingly placed an emphasis on moral and ethical reform as the heart of the gospel. A big champion of the temperance movement, Chambers insisted on total abstinence from alcohol, despite the fact that some of his parishioners made their money from distilling liquor. A Sabbatarian, he urged parishioners to keep a strict sanctity of Sunday as the “Lord’s Day.”45 Chambers rejected creedal statements like the Westminster Confession because they lacked a practical emphasis. He felt that creeds interfered with “holy living” and outreach to those in need.46 And as the Baptist Russell Conwell would later preach to great effect, he taught his followers that “time and talents no longer belonged to himself but to the Lord and should be used in his service.” Chambers stressed the humanitarian impulse of Christianity, an idea that would crop up in the teachings of Josiah Strong and Washington Gladden, leaders of what became known as the social gospel movement later in the century. He argued that people needed to be “like the good Samaritan, to go out of his way to help people in trouble, lend a helping hand in life to those who had fallen, and help to start them on their way again.”47

Wanamaker discovered Chambers’s First Independent Presbyterian Church by accident. One evening as he was walking by the church, the sound of singing drew him inside.48 He had walked into a prayer meeting where men were talking about how religion gave meaning to their lives. The first speaker—an older gentleman with wispy white hair who stepped forward and began to speak of the importance of religion for him and of the way that he now “had a religion to die by”—failed to impress young Wanamaker.49 He recalled that as a young man he was seeking “something not to die by, but to live by.”50 His attitude changed with the next speaker, a hatter named R. S. Walton who walked to the front of the room and spoke of the “practical” side of religion—how as a Christian, he felt that his religion was part of his trade as a hat maker.51 The hatter told the small gathering that business and religion were not mutually exclusive; they were part of one another. Religion informed his trade, and trade informed his religion. In a letter written later in life, Wanamaker remembered that evening and how after the meeting he searched the building for the Reverend Chambers to tell him that “I had given my heart to God that night.” The minister replied with a firm handshake and said, “You will never regret it.” Wanamaker described those words in his later years as “the truest thing that I know.”52

After Wanamaker’s experience at the prayer meeting, he threw himself into a frenzy of religious activities at church, Tower Hall, and then the streets of Philadelphia. He taught Sunday school at First Independent, gathering neighborhood boys for lessons, led prayer meetings during his lunch break, and, like many young men in cities, joined the city’s newly established YMCA. He invited coworkers to church, circulated a temperance pledge to promote abstinence from alcohol, and started prayer meetings.53 The more he devoted himself to religious work, the more zealous he became.

Tireless at first, Wanamaker eventually found that his religious fervor combined with his long hours at Tower Hall took a toll on his health. He suffered from skin infections, and his lungs filled with congestion. He had never possessed a robust constitution.54 Growing up among the chemical-laden industries of Grays Ferry likely exposed him to harsh chemicals. His profession as a store clerk consisted of long hours toiling in improperly ventilated rooms full of textile dust. Poor respiratory health was a constant struggle for retail clerks of the time. Wanamaker consulted a doctor, who prescribed he leave Tower Hall and his religious work to rest and recover. Wanamaker interpreted the doctor’s orders as an opportunity to travel. Taking his savings, he set off to see what was beyond Indiana. He traveled to Chicago and then on to Minnesota, spending time in the woods and fresh air.

The time away afforded Wanamaker a chance to reflect, especially on matters of religion and business. He wrote to a friend of his desire for Christians “to be faithful and true to their profession that they led abroad by their example a power that will grow and expand in the hearts of those around and induce them to join with us.”55 He told his friend that he would come home with recovered health and “renewed energy to engage in the service of the Lord.”56 He returned to Philadelphia at the end of 1857, just as a financial panic took hold of the nation and a religious response to the panic began to stir in American Eastern Seaboard cities.

Urban Prayer

Throughout the second half of the nineteenth century, the United States experienced a series of economic downturns and panics rattling the stability of businesses and financial institutions. In late 1857, credit disappeared, banks closed, and unemployment surged in Northern cities. In the face of economic instability, religious revival movements sprang up in business districts and on Wall Street itself. The grassroots Protestant phenomenon that became known as the Businessmen’s Revival cropped up first in Boston and then, through a series of religious meetings, near Wall Street in New York City. In New York, Jeremiah Calvin Lanphier, a former businessman turned church worker, started a weekly prayer meeting for businessmen at noon on Wednesdays.57 Within a few weeks, over a hundred men attended, and new meetings quickly sprang up.58

The Businessmen’s Revival was at once “a mass stirring of affections” and a disciplined movement. Prayer meetings followed a controlled agenda in a strict one-hour format that ran like a business meeting.59 Revival leaders encouraged attendees to “make an appointment with God.”60 The prayer meetings found immediate success, especially because of their location; the New York City prayer meetings took place at the North Dutch Street Church, a quick five-minute walk from Wall Street.61 New meetings appeared in unusual places, including stores, firehouses, and movable tents, to make them more convenient.62 Though Lanphier spearheaded the nascent days of the revival, the religious movement gained momentum as the country sank deeper into economic crisis by the end of 1857. The revival spread without the orchestration of a high-profile leader and soon found new fertile ground in other major urban centers, including Philadelphia.63 An embryonic Young Men’s Christian Association branch begun three years before by dry goods salesman and banker George Stuart, assisted in catapulting Philadelphia’s Businessmen’s Revival into high gear.64

The YMCA was one of the new and creative evangelistic approaches developed to address the rising tensions in urban areas around the influx of young men looking for work. In London in 1844, a twenty-two-year-old department store sales clerk, George Williams, and a group of eleven friends generated one of the most fruitful and creative institutions to address Protestant concerns. The young men decided to combat what they saw as the unwholesome temptations of urban life that seduced naive young men seeking a new life in the city. Taking inspiration from Charles Finney’s revival preaching, which emphasized moral living and character, Williams and his friends began holding prayer meetings for their coworkers in 1842. Over a two-year period, the prayer group reportedly raised “the morals and morale” of attendees and even converted the owner of the store.65 Soon Williams’s colleagues took their program to other dry goods firms in the neighborhood. They declared that their goal was “the improvement of the spiritual condition of young men engaged in the drapery and other trades.”66 By the summer of 1844, they had founded the Young Men’s Christian Association. While the propagation of Christianity was the initial purpose of the YMCA, it quickly expanded its scope to the mental, physical, and spiritual welfare of young men from a variety of trades.67

The concept spread to other urban areas. Chapters of the YMCA sprang up in Boston and New York City, quickly taking root in the fertile North American evangelical soil among those who sought creative ways to mitigate the threats of the city.68 American YMCAs espoused a “concern for the young man away from his home in the great city” with a particular focus on the “spiritual, mental, and social condition of young men.”69 The Y also built bridges between Protestantism and business—training men for a productive work life and shaping businesses.70 While the YMCA was not the first foray into benevolent societies for the welfare of young men, earlier efforts struggled to gain firm footing.71 Spreading from successful chapters in Eastern Seaboard cities, new YMCA chapters emphasized evangelism in combination with relief services, libraries, and social facilities.72 Hoping to start a branch of the Y in Philadelphia, George Stuart sought out Williams for advice while on a visit to London for business.73 In 1854, three years after Stuart’s visit, Philadelphia’s YMCA branch opened with fifty-seven members, five of whom were clergy. Stuart served as the branch’s first president. The group rented a building at 833 Arch Street that included two of the earliest features of the typical Y: a small library and a reading room.74

The new organization struggled at first. Many Philadelphia churches condemned the local Y, some going so far as to threaten to withhold church membership from any person connected to the organization.75 Ministers feared that the Y would steal away their young men, making congregations unnecessary. Some congregations protested against the YMCA’s habit of welcoming, at least as associate members, Catholics, Jews, and other non-Protestants who wanted to partake in what the Y had to offer.76 Despite initial resistance, the Philadelphia YMCA began to deliver a wide variety of services that emphasized building moral character and encouraged honesty, frugality, and hard work.

During the early months of the Businessmen’s Revival, Stuart redoubled his efforts for the Y, leading revival prayer meetings and generating excitement through publicity.77 His application of business techniques to fundraising put the Y on stronger financial footing. It was Stuart’s grueling schedule that led him to create a paid secretary position to lead the Philadelphia Y, the first such position in a North American YMCA. He approached Wanamaker about filling the position and offered him a generous salary; it was an offer he could not refuse.

Stuart felt that hiring the young, evangelically spirited Wanamaker as secretary could harness the excitement of the revival for his struggling YMCA chapter. Business and religion proved a potent mix—a recipe Stuart communicated to Wanamaker during his service as secretary.

Wanamaker had accepted the position as secretary in part because of the large salary; Stuart personally guaranteed a hefty $1,000 annually. However, Wanamaker soon discovered that, in reality, he needed to raise nearly the entire amount of his salary each year.78 Stuart charged him to “seek out young men taking up residence in Philadelphia and its vicinity, and endeavor to bring them under moral and religious influences by aiding them in the selection of suitable boarding places and employment, by introducing them to the members and privileges of this Association, and, by every means in their power, surrounding them with Christian associates.”79

Under Wanamaker’s leadership, the Philadelphia YMCA experienced a swift expansion in membership and in its physical plant. He focused part of his energy on raising the profile of the Y.80 Advertising played a key role: Wanamaker placed daily advertisements broadcasting YMCA-sponsored prayer meetings—a technique he had learned from Chambers.81 By 1857, the YMCA had garnered favor among some congregations, largely through Wanamaker’s efforts.82 It was an uphill battle, with Wanamaker recalling later, “I never worked harder in my life to stem the tide of prejudice.”83 During his tenure, Wanamaker added an estimated two thousand new members in the three years he served as secretary.84 He recalled, “I went out into the byways and hedges, and compelled them to come in.”85 Wanamaker focused his outreach to the “rougher edges” of Philadelphia society. After all, although he was transforming himself into a white-collar worker, he had grown up in Grays Ferry.

Wanamaker enthusiastically supported Philadelphia’s Businessmen’s Revival in his role as Y secretary. In collaboration with Stuart, he guided the local Y’s efforts to fan the flames of the revival by offering space for evening meetings, and when the embers of the movement appeared to cool, the Y “reactivated it with the Union Tabernacle, a movable tent set up in various parts of the city.” The mobile worship service aimed to spread “the Gospel to masses who would not enter a church.”86 He also organized and led noontime prayer meetings at a local hall. The meetings quickly mushroomed, making it necessary to rent out the largest auditorium in the city for the meetings.

Wanamaker also focused his energy on religious outreach to the city’s infamous firemen; he wanted to “reform their character.”87 Firefighters in mid-nineteenth-century Philadelphia had a reputation for rowdiness and the use of profanity. Because they were paid based on who arrived first at a fire, an intense rivalry developed between competing fire companies, leading to gang-like behavior that resulted in outrageous pranks and sometimes violence.88 Wanamaker brought the prayer meetings to the firehouses, making attendance for firefighters almost impossible to avoid. His efforts appeared to pay off, with hundreds of firefighters attending revival meetings and joining religious organizations.89 Wanamaker learned about the power of persuasion.

Near the end of his tenure with the Y, he helped the Philadelphia branch save enough money to purchase a dedicated building to house its wide-ranging services and offer a consistent moral atmosphere. Stepping down as secretary, he moved into Stuart’s role as president of the branch—steering the group to raise funds and complete its first two buildings. Wanamaker felt that dedicated buildings and spaces aided the work of the YMCA. Wanamaker’s faith in the potential of a “built environment” to stir change began to grow.

As Wanamaker moved into his new role as secretary of the Philadelphia Y, he also returned to the Sunday school work he had begun. He attended an American Sunday School Union meeting and volunteered to start a mission Sunday school.90 In 1790 a consortium of Philadelphia Protestant groups had founded the Sunday School Union, which was part of a wider religious and education movement in the United States and Great Britain.91 Its successor, the American Sunday School Union, began in 1824 and focused on planting Sunday schools in impoverished areas. Working as a Sunday school missionary was a path to the ministry for many young men. By the 1840s, eager Sunday school workers poured into poverty-stricken areas, urban and rural, to establish Sunday schools. Wanamaker’s success with the noontime prayer meetings during the Businessmen’s Revival fed his confidence for church work. By starting a Sunday school, he would have a chance to shape the character and beliefs of young men and women in his community.

Wanamaker decided to start his mission Sunday school near his childhood home in a working-class immigrant neighborhood ruled by gangs of boys and young men called the Schuylkill Rangers, or sometimes simply the “killers,” or the “bouncers.”92 It was a predominantly Catholic enclave. On a snowy day in early February 1858, Wanamaker held a preliminary meeting in a vacant house loaned to the cause with the help of the Reverend Edward H. Toland, an American Sunday School Union official. They encouraged those who attended to give their names and addresses and to invite their friends when the next meeting gathered. Outside, the loud jeering and shouts of the neighborhood gang marred the session, and, fearing for their safety, his potential students fled out the back door.93 Wanamaker attempted to confront the gang and was physically threatened.94 Undaunted, he held the first official meeting of the Sunday school a week later in the second-floor room of a cobbler’s shop. Wanamaker had spent the week canvassing the neighborhood to ensure that a large group of children would attend. He asked his sister Mary and her friend Mary Brown to assist.95 During the meeting, the neighborhood gang returned, interrupting the meeting. They “broke in the lower door” of the cobbler’s shop, “raced up the stairs, chased out the children and warned” Wanamaker and his two teachers “to leave and never to return.”96

Wanamaker remained undeterred. He planned another gathering of the budding Sunday school for the next week despite the threats. His sister and her friend agreed to return. Wanamaker needed to secure a new location after the cobbler complained of damage caused by the gang; however, word had spread about the Sunday school. Fifty children and adults appeared for the third meeting. The Rangers not only attacked again but escalated their assault, this time pelting Wanamaker and the Sunday school children “with rotten eggs, bricks and snowballs until a policeman drove off the gang.”97 Despite this setback, and likely shaken, Wanamaker promised the children and their parents to return the next week. He made a plan to thwart the gang by calling on the local firefighters he had befriended during the revival for help.98 The firemen spread the word that they would not tolerate attacks on Wanamaker and his Sunday school.99 The fourth meeting of the Sunday school was not interrupted, and even more children came, though sporadic harassment by the gang continued throughout the first months.100

Wanamaker’s Sunday school flourished even as he divided his time between the school and the YMCA. Now established, the group returned to the cobbler’s shop, only to outgrow the space by spring. They needed a new place to meet. A member of Chambers’s congregation, an elderly German man named John Oberteuffer, surveyed the neighborhood for a meeting spot to no avail. He then suggested collecting discarded sails from the wharves off the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers and using them to build a tent for the Sunday school. Oberteuffer personally collected the sails, Wanamaker and boys from the Sunday school cleared an old ash lot loaned for the purpose, and the mothers of the Sunday school children sewed the old sails together to create the tent. Not everyone was pleased with the new tent Sunday school. A Catholic neighbor threatened to burn it down if it was erected. Ignoring the threat, the Sunday school raised the tent and set up a schedule of overnight guards to protect it.101 By July 1858, the school held its first meeting inside what Wanamaker called “a beautiful little white church” situated on a borrowed lot.102 To accommodate large crowds, especially when popular ministers preached, the tent flaps were raised. Wanamaker reported that three hundred children attended the first tent meeting. Although it was initially called the Chambers Mission School after his beloved minister, Wanamaker and his followers decided to name the Sunday school Bethany, after Luke 24:50, a text that focuses on the risen Jesus blessing his disciples.103 Wanamaker said that the new name mirrored his hope for the school, that it would be “a place of blessing, a home where spiritual food, comfort and love can be found!”104 The school focused on service and on creating a moral environment rather than emphasizing doctrine or creed. It continued to grow, and by January 1859 a simple building had been constructed. Barely a year had passed from the beginning of the Sunday school mission.105

In 1862 an attempt was made to add a church to the Sunday school. Continuing what would be a lifelong flexibility in denominational labels, the first minister called to Bethany was the Reverend Augustus Blauvelt of the Dutch Reformed Church to serve as the first “Missionary” of the congregation. He served the church for a year before departing due to ill health, leaving the church side of Bethany in disarray.

Bethany drew over half its members from what one historian describes as “a mix of lower white collar and blue collar laborers.”106 Despite the outbreak of the Civil War, the Sunday school grew, and by the end of the war there were over nine hundred on the Sunday school rolls. In the summer of 1865, Bethany welcomed the Reverend Samuel Lowrie to try once more to launch a church alongside the Sunday school. This time the effort met with success, and the congregation broke ground on another building, at the corner of Twenty-Second and Bainbridge, to accommodate the congregation’s rising membership.

By end of the Civil War, the Sunday school had become too large for Wanamaker to handle alone, especially as his retail business took off. He signed on new staff to run the congregation and Sunday school.107 One of the first individuals he hired was John Neff, the man who found him his first job, who was employed to assist with the school. A series of ministers followed Lowrie, attracted by the opportunity for urban missionary work. They served for a few years and then departed, often to purse foreign missionary work or revival preaching. This became a pattern at Bethany. Wanamaker’s constant presence as a leader may have been another reason for the high turnover. Initially, he was the only ordained elder in the congregation and was a permanent member of the church’s governing board. Bethany’s ministers answered to him.

Bethany’s building, at the corner of Twenty-Second and Bainbridge, was as much a part of the mission as its location and services. Members of the Sunday school raised the money, many sending notes with their weekly donations explaining what they had originally budgeted the money for and how they instead were donating it to Bethany. The first building was a lofty square brick Greek Revival structure with poor acoustics; Wanamaker recalled that “no one could speak in the building so as to be heard.”108 Despite the money and time invested in the building and potential embarrassment, they tore it down, saving only a large stained-glass memorial window from the building. The congregation again started construction.

Bethany’s new building bore little resemblance to its first iteration. Designed by the up-and-coming Philadelphia architect Addison Hutton, the much larger building wrapped the corner of Twenty-Second and Bainbridge, reaching down the block in two directions. The architect used a Gothic Revival style that had surprisingly become “the generic Christian style” of church architecture in the United States starting in the 1840s and continuing into the first two decades of the twentieth century.109 Proponents of the design believed that Gothic structures possessed an aesthetic power that had the ability to uplift the city through beauty. And it was more than aesthetics. It was a reassertion of clerical and Protestant authority through spatial politics.110 Gothic structures made imposing additions to neighborhoods and city skylines and challenged the Catholic cathedrals sprouting up at the same time. Wanamaker’s fascination with Gothic architecture and Catholic forms would increase in the coming years.

Figure 1.1. An undated postcard (ca. 1870s) of Bethany Presbyterian Church’s second building at Twenty-Second and Bainbridge in a Gothic style. Over time, Wanamaker purchased nearby buildings to house the expanding services the church offered to members and the surrounding neighborhood. The postcard’s inset shows a young John Wanamaker, and advertised the connection between the merchant and the church.

Hutton’s conception of Bethany produced a tall brick-and-stone multigabled structure with large Gothic arch windows. A slim bell tower protruded from the middle. Signaling its public nature, the bell tower contained an immense clock. At the corner intersection of the building, wide steps led to the main entrance. It made a statement in the neighborhood with its size and dignified style without taking on the more ostentatious decorations of Gothic Revival architecture.

Inside, the sanctuary incorporated the fashionable theater style used by many evangelical Protestant congregations. Bethany’s chancel had a broad stage with a centrally located pulpit. A large organ anchored the chancel, and its pipes offered a dramatic backdrop to the pulpit and choir.111 The auditorium seated fifteen hundred and had a sloped floor to improve visibility and acoustics. The wooden pews faced the central pulpit and were curved on the sides so congregants could maintain eye contact with the preacher. Tiffany stained-glass windows filtered outside light from a clerestory above and large windows opposite the chancel stage.112 The round room allowed parishioners to see and be seen by one another. The seating arrangement promoted not only attendance but concern over proper decorum.113 It also engendered an intimacy that older box pew churches lacked. A balcony wrapped the upper story of the mahogany-trimmed auditorium, adding more seating with a good view of the chancel below. Delicate ironwork decorated the balcony railings. Support pillars in the front of the sanctuary framed the chancel much like a theater’s proscenium.114

Wanamaker and his handpicked teachers instructed his Sunday school using the latest methods in religious education in a smaller auditorium that seated five hundred. The portion of the building devoted to the Sunday school also had an extensive series of rooms for meetings and education. The large room employed the “Akron model” of folding partitions to make classrooms “entirely isolated from one another, thus grouping the pupils into classes according to their ages and needs.”115 The model offered maximum flexibility for the large Sunday school. After the age-group classes finished, the group convened “for the general lesson,” which Wanamaker frequently led. The large Sunday school room decorated by a fountain in the middle was equipped with curved desks and benches for the young scholars pointed toward the front of the room.116

Wanamaker saw Bethany as a moral force in the neighborhood. Thirty years later, at the International Sunday School Convention, Wanamaker reflected on the effectiveness of Sunday schools. He told the audience, “It is the only School organized to teach the Bible at the most teachable age; to inform the mind, influence the heart and mould the life in the highest principles of unselfishness and uprightness in the fear of God and love for our fellow men.”117 He felt that Sunday schools leveled social strata and opened opportunities for all: “The Sunday-school door, wide open to all alike, lets in a ray of hope that there are no levels marked ‘Reserved,’ and places of equal footing and equal opportunity for all men.” As historian Jeanne Kilde has noted, “In Protestant churches of the late nineteenth century, then, location, architecture, and mission intertwined, influencing and altering one another, merging in the process of meaning creation.”118 A part of this meaning placed these churches at the intersection of public and private, a “spiritual armory” against the onslaught of urban changes and a hub of outreach to the working class and those who struggled on the margins.119

At its height, Bethany boasted 6,097 enrolled in the school, making it one of the largest in the country.120 Its Sunday school rolls and membership numbers were points of pride for the congregation and were regularly quoted. And although Bethany began under a Presbyterian flag, the congregation had an independent streak running through it, much as Chambers’s First Independent did; it had more in common with the popular revivals of the day led by Moody and others. After the Civil War, Bethany broadened its focus beyond religious education and salvation to community service under the leadership of Wanamaker and its ministers. Wanamaker took the lead in opening a series of institutions and programs to support the working poor. In particular, calling the Reverend Arthur Tappan Pierson solidified Bethany’s standing as what would become known as a social gospel church.121

Making a Social Gospel Church

Wanamaker and Pierson had struck up a friendship sometime in the 1860s, most likely through their Presbyterian and YMCA connections. They also shared a passion for urban mission outreach and the temperance movement, and both were friends with Dwight L. Moody.122 Pierson turned out to be a prolific writer, penning dozens of articles, sermons, and lectures that led to a rapid rise in prominence. Interested in foreign and domestic missionary work early in his career, he read extensively and traveled to Europe to learn about British urban missions.

On a visit to England in 1867, Pierson wrote a letter to Wanamaker that shows the extent of their friendship. Visiting a number of urban mission tabernacles and leading British preachers, Pierson explained to Wanamaker, “I am seeking to find, that I may carry back the information for use among our own members,” “how the most successful churches here are carried on especially among the same class as we are seeking to reach.” He attended services at the famous Metropolitan Tabernacle, the largest Baptist church in the world, to hear the eminent Charles Spurgeon preach. The church was designed architecturally with an opera house in mind to help make city dwellers feel more comfortable coming to worship.123 The experience made an impression upon Pierson, and he had carried the ideas of the Metropolitan to his work in Detroit and Philadelphia. Pierson held Wanamaker in great esteem and harbored the same worries Moody had for the merchant and his growing business. Pierson confided in his friend, “I want you to be like a star in god’s right hand. May he keep you in the hollow of that hand.” Unlike Conwell, who saw Wanamaker’s success as a sign of God’s blessing, Pierson had warned his friend, “You need [God’s] keeping, you are in a high place—a fall would be correspondingly deep,” and urged him to “hide yourself in his [God’s] deep shadow.”124

The year before Pierson’s European trip, he joined the Evangelical Alliance. Founded in 1847 in London, the American branch of the Alliance took twenty years to gain momentum. Following the Civil War, the organization gathered a group of elite, educated Protestant evangelicals: urban ministers, seminary professors, businessmen, and college presidents. They wanted a “social Christianity” that addressed the practical and religious needs of the working poor and foreign-born without losing the importance of individual conversion, moral living, and the centrality of the Bible.125 The group emphasized Christian unity and partnership among the denominations while pointedly opposing Catholicism.

The Alliance’s social gospel approach promoted a “moral equivalent of war” on a variety of social ills fought by Protestants from numerous denominations holding a variety of theological perspectives.126 Institutional churches served as a major “weapon” in the social gospel war.127 As one scholar notes, “With its emphasis on ministering in the community and making the church a vital part of its neighborhood, institutional churches brought many middle-class Protestants in the pews face to face with the problems of an industrializing urban society.”128 It provided a way for white Protestants to cope by actively responding to the social ills they saw around them.

Pierson was one of the younger members of the Alliance, but it was a comfortable space for him—his theology professor, Henry B. Smith, and several other members of the Union Seminary community were leaders in the renewed organization.129 The secretary of the Evangelical Alliance was Josiah Strong, one of the leaders of what became called the “social gospel movement” and author of the bestseller Our Country: Its Possible Future and Its Current Crisis, published in 1884.130 In the book Strong made a case for mission work in the United States to reach the immigrant working-class masses. Pierson completed his own acclaimed book, The Crisis of Missions, shortly after Strong’s. His book had a foreign mission focus and set the stage for Pierson’s later leadership in foreign missions.

Pierson had left the congregation he served in Massachusetts in 1869 to settle at Fort Street Church, a prominent and wealthy Detroit church with railroad barons among the parishioners. Espousing a strong social conscience, Pierson fretted over the growing “materialism” of his congregation, especially among the emerging middle class. The congregation had disappointed him with its lackluster response to Reconstruction and to the newly freed people of the South. Observing the changes in society around him, he felt conflicted by the ways Native Americans and immigrants were treated and believed that without Protestant Christianity, the social fabric of democracy was threatened.131

For seven years, Pierson had urged his parishioners to be more attentive to the urban poor and to the need for missionaries abroad. Expressing a strong missionary impulse, he recognized the need to evangelize the city as much as the foreign mission fields. Successful at encouraging his church members to fund foreign missions, he struggled to make the church, with many wealthy members, into one that served the neighborhood’s working poor and immigrants. The congregation refused to get rid of “pew rentals,” which would have enabled Pierson to open the doors of the church to those who could not afford them, what he called the “unevangelized masses.”132 He dreamed of his own Tabernacle church like Spurgeon’s and Finney’s as a way to reach the masses who did not feel comfortable in ornate churches. Pierson grew more agitated over his congregation’s lack of response to the urgent need around them. On March 24, 1876, a sudden fire answered his prayers. The blaze gutted the elegant Gothic building of Fort Street Church, toppling its mighty spire, one of the tallest in the country, and creating an opportunity for the change Pierson craved.133

After the fire, the congregation rented Detroit’s Whitney Opera House to conduct worship services while they decided how to rebuild. Pierson convinced the congregation’s leadership not to reserve seats for members as they had done before and instead allow the poor to mingle with the rich and sit where they wished. He adopted a more casual “gospel style” of worship that was the hallmark of revivalists and the worship service of the Broadway Tabernacle and other earlier experimental churches.134 He made the service less formal, took up extemporaneous preaching, and held an altar call at the end of every service for those who sought prayer or conversion. Local newspapers called Pierson’s worship services a revival, and for sixteen months the Opera House services were packed, with thousands turned away at each service.135 Pierson begged the church leadership not to rebuild a church for the wealthy but instead to construct one that continued to welcome and serve the poor. The Great Railroad Strike of 1877, during which West Virginia railroad workers went on strike over repeated wage cuts and other workers joined them across the country, only to be broken by state militias and federal troops, deepened Pierson’s resolve to create a missionary church in the city. He wanted the congregation to serve the real needs of the neighborhood by offering services. The congregation’s answer to his pleas was clear. They rebuilt the church within the walls of its original Gothic structure, complete with an opulent interior, and reinstated pew rentals.136

Pierson began looking for another congregation that would welcome his ministry. He landed briefly in Indianapolis at the centrally located Second Presbyterian Church in 1882. There he found the same obstacles he had encountered in Detroit. From the outset, Pierson’s strong moralizing sermons against drinking, playing cards, and other amusements prevented him from forming a warm relationship with the congregation members. Although he rented the local opera house for evening services and again drew large crowds, Pierson resigned after six months. He felt that the church was not a good match for his vision. Wanamaker began courting Pierson to be the minister of Bethany after a YMCA meeting in Milwaukee. The congregation was between ministers once again, and the merchant knew that he and Pierson held a similar vision for the church. At the meeting Wanamaker implored Pierson to visit his church in Philadelphia. He wanted to share the work of Bethany but the invitation also had another purpose: Wanamaker had possibly heard rumors—or had heard from Pierson himself—that he was not happy in his new parish.

Pierson was very direct with Wanamaker, laying out his vision of the church to convert and serve the urban poor.137 He would not accept another post that failed to align with his ideas about the purpose of the church. He also suggested a shift to full-immersion baptism, a surprising move for a Presbyterian. Wanamaker agreed to the minister’s vision. He had already made adjustments to Bethany’s worship by adding a printed program with popular gospel hymns, a choir, and a church orchestra. Wanamaker reported to Pierson that when they built the church they had installed an immersion baptism pool that was yet unused. Pierson was impressed that Wanamaker had planted the church in a poor Philadelphia neighborhood as a Sunday school mission, deciding perhaps he had more in common with the department store magnate’s church than he had realized. Pierson accepted the offer to come to Bethany, but he insisted on being paid less than the original offer and stipulated that his entire salary would be raised through free-will offerings rather than through pew rentals.138 In this church, he would live the social Christian experiment he had been dreaming about.

Pierson discovered a like-minded Presbyterian in Wanamaker. Professing similar beliefs about morality, temperance, and the evangelical purpose of Christianity, they set about creating an “institutional church,” one of the expressions of the social gospel movement. Historians have long disagreed on the definition of the social gospel movement and whether social gospel churches are identifiable by actions or beliefs.139 It was a more multivalent movement than often presented, with fluid boundaries and no single theological center; many different people and institutions identified, promoted, and endorsed social Christianity.140 Even without a definitive theological statement from the movement, scholars tend to place social gospelers in the liberal progressive camp. Contrary to common interpretations that often place the social gospel and revivalism on opposite poles, many leaders of social Christianity thought, wrote, and spoke as evangelicals who valued campaigns for conversion. Their social awakening, social salvation, and social evangelism were expressed in revivalist terms; they did not deny the prevailing emphasis on individual salvation but instead added a social dimension to it.141

Wanamaker and Pierson moved Bethany into a full-blown social gospel church, founded on the mission Sunday school, that attempted to address the problems of urbanization and of the burgeoning working and middle class.142 Under their leadership, Bethany created dozens of social outreach programs offering a wide variety of “services” to the neighborhood through a network of institutions that expanded the church’s geographic presence far beyond the corner of Twenty-Second and Bainbridge.143 While the church housed some of the services, over time Wanamaker bought buildings for the dedicated use of the congregation’s service branches. Bethany’s services included the Friendly Inn, a home for unemployed men; an infirmary offering medical services to those in need; and a Deaconess Home for older single women who dedicated themselves to the church and gave back to the community by running a small kindergarten. Wanamaker acquired a building for the Bethany Mission on Bainbridge and Carpenter Streets to serve the neediest in the community. Mary Wanamaker continued to work at Bethany and particularly enjoyed leading classes on sewing, proper hygiene, and cleanliness for working-class women.144

On what had been the original site of the Bethany’s tent church, Wanamaker constructed a men’s clubhouse for the local branch of the Andrew and Phillip Brotherhood, an organization that promoted Bible study, community service, and physical fitness and was a part of a national, cross-denominational movement that had started in 1883 in Chicago.145 Wanamaker founded the chapter at Bethany and regularly attended Brotherhood meetings before teaching Sunday school. The Brotherhood House offered books, wholesome entertainment, and an art gallery.

In 1888 Wanamaker opened the Penny Savings Bank in the basement of Bethany, a concept similar to Philadelphia’s Cardinal John Neuman’s Beneficial Bank, which helped immigrants keep their money safe and helped them learn to save. As the bank’s name advertised, it accepted very small deposits, even as little as a penny, with the hope that it would encourage children and their families to save. When the bank outgrew its church quarters, Wanamaker found a building a few blocks away to house the institution as he was to do many times over the years, for service organizations he supported in the United States and abroad.146 The year before Pierson arrived, Wanamaker opened a night school he called Bethany College, to equip unskilled laborers with a vocational education in an effort to help them secure better employment.147 Pierson took up teaching at the college on a range of theological topics.

In many ways, Bethany emulated the YMCA, which had shaped and inspired the services the church offered. Most of Bethany’s outreach programs sought to instill “middle-class values” such as frugality, cleanliness, and temperance steeped in moral living and religious devotion.148 A booklet describing the Sunday school’s methods listed—in addition to Bible classes, prayer services, and mission and temperance work—wholesome entertainment and life skills coaching that covered how to make a household budget, dietary instruction, sewing, and more. Pierson and Wanamaker remained a team until 1889, when the minister felt a pull to return to missionary work.

By 1904, long after Pierson had left and other ministers had served at Bethany’s helm, Wanamaker remained the ever-present thread in the life of the congregation. A visitor that same year described Wanamaker’s bustling church and Sunday school: “There were thousands of children, with their fresh faces and in their Sunday dress, from little girls and boys of six or seven years to young men and women of eighteen and twenty.”149 Sunday mornings began at eight o’clock with the gathering of men and women who studied scripture texts as a source for “practical religion.” Impressed by the gathering, the visitor remarked, “When I looked out over the Sunday-school of Bethany Church, I seemed to see before me a garden of God.”150 Bethany continued to draw visitors and impress them with the Sunday school.

***

Wanamaker’s life had taken a big turn at the beginning of 1858. He participated in the Businessmen’s Revival, led noontime prayer meetings, started work at the YMCA, and planted a mission Sunday school that would grow to be one of the largest institutional congregations in the country. In 1860 he married Mary Brown, the young woman his sister brought along to help teach his first Sunday school class at the cobbler’s house in South Philadelphia. His father died around this time, leaving the care of his beloved mother on his shoulders.

Choosing between ministry and business proved challenging. Wanamaker’s passion for ministry only grew with his Sunday school and YMCA work. However, some friends advised him against ministry, noting his fragile health. Others suggested he become a minister of a small congregation in the country to protect his health. Wanamaker, in turn, began to think about business in a new way: “I thought that if I became a man of means through my business, I might be able to accomplish as much or even more for Christ than I would have as a minister.”151 Perhaps his business could help his religious endeavors.

Now with a wife to support, Wanamaker left the YMCA, and with the money he had saved he decided to open a men’s store with his new brother-in-law, Nathan Brown. The young men tried to buy the store of Wanamaker’s old employer, but Bennett refused their offer. So, with their combined savings of $3,500, the men leased two floors of the six-story McNellie Building on the corner of Sixth Street and Market Street (at that time called High Street), near the Pennsylvania State House (Independence Hall), and bought a small supply of men’s suits, collars, shirts, cuffs, neckties, and other accessories.152 The new store was situated on the same block as Colonel Bennett’s establishment in the retail district of town.

War was brewing and the economy was still recovering from the economic crisis of 1857–1858, but the two entrepreneurs appeared to pay little attention to problems of timing.153 They called the store Wanamaker & Brown, Oak Hall, perhaps in a competitive nod to Colonel Bennett after he had refused to sell Tower Hall to the young men. Oak Hall held its grand opening on April 8, 1861, two weeks after Wannamaker’s first child, Thomas was born. Only one customer entered the store on the first day.154 Within a week, the Civil War began.155

The war began slowly; it was July before the first major battle broke out at Bull Run. As news of the battle spread to Philadelphia, Wanamaker attempted to enlist in the Union Army despite his obligations at home and in the store, but the army physicians refused him for his poor lung health. His rejection was a wound he carried throughout his life, calling the army’s refusal “his greatest humiliation.”156 But Wanamaker found another way to support the war effort. At a fledgling national YMCA meeting in New York City in November 1861, delegates voted to create a Christian service commission to attend to the “spiritual welfare” of soldiers and sailors by providing chaplains in hospitals and on the battlefields. George Stuart was tasked with leading the newly developed organization and once again enlisted Wanamaker to help recruit volunteers, raise money, and organize the massive undertaking.

Many of Wanamaker’s friends predicted that Oak Hall was doomed to fail.157 They thought that Wanamaker and Brown were too inexperienced and that the war and economic landscape were not favorable for a new enterprise.158 The early days of the store were challenging. Wanamaker’s connections through the YMCA and other evangelical organizations gave the young shopkeepers a reputation of integrity and trustworthiness, leading banks to extend credit, a resource that made the difference between success and failure.159 The war also contributed to the new store’s survival. An order for uniforms for local Union regiments provided income that kept the store afloat during the lean years.160

To draw customers to their shop, Wanamaker and Brown created innovative advertisements before their doors were even open. For the first half of the nineteenth century, retailers considered store advertisements gauche. Store location, word of mouth, and quality of goods were the primary attractors for businesses.161 Yet Wanamaker had watched Chambers bring visitors to the church through advertising. Colonel Bennett had attracted customers with attention-grabbing poems in the newspaper without ever mentioning his merchandise. To draw attention to their new establishment, Wanamaker and his partner took a similar approach and covered Philadelphia with mysterious advertisements displaying their initials “W & B” with no explanation.162 Thirteen painted billboards, some a hundred feet tall, went up all over the city, and balloons carrying prize certificates were released. Anyone who returned with a certificate received a free suit of clothes. These campaigns succeeded in drawing attention and excitement to Oak Hall’s opening.163 The favorable outcome of the initial advertising onslaught fueled their efforts. Soon, the name “Oak Hall” plastered fans, postcards, posters, and other small goods, leading one observer to jest about “the universal Wanamaker & Brown chiseled on the street crossings, painted on rocks, and mounted on house-tops. That they have not been wafted to the clouds, and tied to the tail of a fiery comet, is only because Yankee ingenuity has not yet devised the ways and means.”164 Wanamaker & Brown, and later Wanamaker’s stores—he never liked or adopted the label “department store”—maintained the tradition of creative and unconventional advertising.165

Surviving the lean war years, Wanamaker and Brown’s Oak Hall reaped the benefits of the postwar boom economy.166 The two men had expanded their clothing store from two floors to the entire McNellie Building. The men established a wholesale and mail-order enterprise on the top floors of the building and made a name for themselves selling reasonably priced and high-quality men’s wear. When Brown died three years later in 1868, Wanamaker bought Brown’s shares from the estate and continued to enlarge the business under its original name. A year later, he was again ready to expand his store and the merchandise it carried but found the adjacent properties too expensive to acquire.

Abandoning the idea of one large store, Wanamaker purchased property next to one of Philadelphia’s upscale hotels, the Continental, on Chestnut Street between Eighth and Ninth. The new store featured an open floor plan lit from above by a large skylight. Galleries open to the main space formed the upper floors of the store. Wanamaker outfitted the new establishment with high-end finishes, thick carpets, and large, gilt-framed mirrors and experimented with hanging artwork.167 A man decked out in livery stood at the front door, a practice Wanamaker had abandoned at Oak Hall when customers deemed it too pretentious.168 On the street, large show windows topped with “mediaeval stained glass” provided space for displaying merchandise—an approach that scandalized other merchants.169 He called his new luxury store John Wanamaker & Co. and opened its doors under the management of his brothers.

By the end of 1871, Oak Hall and John Wanamaker & Co. had surpassed Colonel Bennett’s Tower Hall as the largest men’s store in Philadelphia with the purchase of adjoining buildings.170 That same year, inspired by previous fairs and a Wabash College professor’s vision of a great fair to celebrate the centennial of the Declaration of Independence, Wanamaker, along with a group of businessmen and state political leaders and with the blessings of the city and state, petitioned Congress to hold a world’s fair in Philadelphia. That year he also traveled to Europe for the first time.171

“A School for the Nation”

Over the span of fifteen years, Wanamaker had withstood a series of painful economic panics, financial downturns, and the personal tragedies of losing two children, his son Horace as an infant and his little girl Hattie at the age of five. He had transformed a small men’s store started on the eve of the Civil War into a thriving retail establishment with a luxury branch. But neither Wanamaker & Brown’s Oak Hall nor John Wanamaker & Co. constituted a department store. During a visit to Europe to inspect a wool manufacturer, Wanamaker arranged a visit to London’s International Exhibition. The visit gave him his first inkling of an idea for what he called “a new kind of store.”

London’s Annual International Exhibition in 1871 was not the first international display of the latest technology, goods, and art gathered in one place. Previous exhibitions in Paris, London, and New York City had evolved out of a century of fairs and trade gatherings that were initially aimed at the working class. In 1851, under the guiding hand of Queen Victoria’s husband, Prince Albert, London hosted a spectacular exhibition in a dazzling glass structure built for that purpose. Inside what became known as the Crystal Palace, a series of grand displays presented the latest in technology and luxury goods. The exhibition demonstrated the power and riches of the British Empire and served as a rationalization of colonialism. Technological advancements and artistry were positioned as the pinnacle of Western white civilization. Organizers had developed new “ways of showing” goods and created organizational concepts to categorize the massive collections of objects, people, and machines brought together for the exhibits.172 Luxury items were displayed in great abundance and with dramatic flair, inviting the onlookers to see high-end goods and then to make the leap that luxury was not just for the aristocracy anymore. From the architecture to the exhibits, visitors were invited to look, with no other purpose, at the wonders of the modern industrial age.173 In the open and protected spaces of the Crystal Palace, fairgoers also were able to watch one another.

London’s successful exhibition spawned a proliferation of world’s fairs from Dublin to Calcutta throughout the nineteenth century.174 In particular, Paris fell in love with the expositions and held them in 1855, 1867, 1889, and 1900. The fairs coincided with the French capital’s rise in prominence for American tourists. The century before, it had been a way station en route to Italy, but now Paris served as a primary destination for Americans to obtain culture and taste.175

Publicity for the Exposition Universelle Internationale de 1900 in Paris boasted of the democratizing power of the exposition: what was “once the exclusive possession of a few noble spirits of the last century today gains ground more and more.”176 The event, and others like it, offered an opportunity for a shared experience for a large number of people. The promoters asserted that the displays were “the common religion of modern times,” imparting a “powerful impetus . . . to the human spirit.”

The great exhibitions’ displays did bring people together, making them a temporary and seductive “pilgrimage” site for all classes.177 Education and the demonstration of technology served as themes for the majority of the exhibitions.178 Each exposition offered innovations of industry, science, art, music, and luxury goods presented in an ever-increasing spectacle of power, fantasy, and beauty. Cultural critic Walter Benjamin called it “the enthronement of the commodity.”179 Machines, commodities, and objects from the host city and country, and from around the world, were gathered together and meticulously organized and categorized.180 Drawing millions of visitors, the great exhibitions proved to be some of the most significant events in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.181 In turn, the exhibitions inspired and shaped the emergence of art museums and department stores.182 All three institutions—exhibitions, art museums, and department stores—concentrated on the display and organization of a wide range of objects. Each sought to educate the masses and guide public taste.183

London’s International Exhibition of 1871 acted as a catalyst for Wanamaker. At the exhibition, his traveling companion, Dr. Samuel Lowrie, Pierson’s predecessor at Bethany, recalled that Wanamaker was “like a child” at the fair, reveling in the majestic pipe organ at the center of the building that led a large crowd in singing.184 He loved seeing the latest technology mixed with paintings and unusual objects. He returned home full of ideas for the upcoming Centennial Exhibition and new possibilities for the expansion of his two stores.

Wanamaker pondered the possibility of enlarging his store again by merging the two stores under one roof. He launched a search for a larger space with the idea that more space would allow him to try new merchandising techniques. On the hunt for affordable options, he looked west of the retail district where, in 1865, the Union League Club had built an imposing French Renaissance building. Nearby, city hall had broken ground in 1871 for a massive “New Public Building” at the intersection of Market and Broad Streets, and the Masonic Temple started construction on a new edifice in 1873. The plan for the new city hall had blocked the Pennsylvania Railroad’s right of way and necessitated moving its freight depot to another location. The move had left behind the empty train shed and a four-story building.

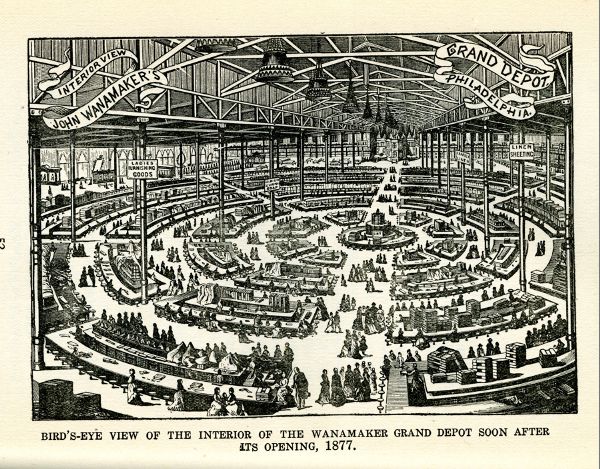

Wanamaker did not at first see the old train depot as a possible location for his new store. In the fall of 1874, the now-empty depot hosted an exhibition by the Franklin Institute. For the fair, the institute adapted the old depot by enclosing the glass train shed. Underneath the glass canopy, with natural sunlight from above, fair organizers laid out a series of display booths that featured new inventions in engineering and mechanics. As Wanamaker walked through the building, he began to visualize the freight depot as an unlikely but nevertheless creative location for a new store where a larger selection of merchandise could be categorized, systematized, and grandly displayed.185 The train shed’s glass-and-iron ceiling mimicked the Crystal Palace and had much in common with the plans for the Centennial Exhibition’s Main Building.

The depot site also offered an enormously flexible space and, at the time, the largest open floor in Philadelphia. Wanamaker recalled, “The idea came to me that it was the greatest situation for a large store, but I was perplexed and frightened at the idea of making the purchase.”186 Relocating his stores away from the established retail district would be a daring move full of uncertainties. All indicators—particularly the construction of several new buildings—pointed to Thirteenth and Market Streets becoming the new center of Philadelphia. But it was still quite a distance from the retailing district. His original store was on the same block as the Pennsylvania State House (Independence Hall) on a street filled with stores. The depot was just over a half mile across town. Filling the depot space proved to be another problem. Initially, Wanamaker planned to entice other businesses to partner with him and to open specialty “departments” in his depot. When this scheme broke down, he decided to move forward with the new store alone.

The location posed a danger; he could lose regular customers if he overestimated how far they were willing to travel. To balance the risk, Wanamaker decided to maintain his original stores, Oak Hall and John Wanamaker & Co., under the management of his brothers and to use the depot as a place to advertise the stores to the Centennial Exhibition visitors by offering similar goods and the same level of service.

Wanamaker purchased the cavernous freight depot as a retail experiment. He negotiated an option on the train shed and left for Europe with his family to take notes on the methods for storekeeping, displays, and selling different kinds of merchandise employed by the multidepartment stores of Paris.187 They were also taking part in a rite that wealthy and middle-class American families had begun before the Civil War—a tour of Europe.

While the Wanamaker family traveled in Europe, a group of Philadelphia Protestant businessmen received the good news for which they had been waiting anxiously. Moody and Sankey, now among the most famous revivalists in the country after their triumphant tour of England, Ireland, and Scotland, sent word that they would be coming to Philadelphia. Although the Philadelphia Academy of Music was available for the revival, the businessmen wanted a larger space to host what they hoped would be the most successful Moody revival in the United States. They contacted the Pennsylvania Railroad about their old train depot, only to discover that Wanamaker was in the process of purchasing the building. The men, all friends of Wanamaker, sent word to Europe asking whether the train depot was available for the revival. Hosting the revival would delay construction on his new store, but Wanamaker agreed to rent the freight depot to the committee for one dollar, declaring, “The new store can wait a few months for its opening; the Lord’s business first.”188