5

Christian Interiors

To give people the things they want is not enough for the Wanamaker Stores. . . . They must be a leader in taste—an educator.

—John Wanamaker1

On Christmas Eve in 1911, John Wanamaker stood in the middle of the colossal atrium of his new store building. He was now seventy-three years old and had been in business for over fifty years. He looked up to take in the sweeping marble-clad seven-story space and the series of skylights crowning the top that brought natural light into the heart of the store. At night, the latest technology in electricity kept the store brightly lit for late shoppers.2 Corinthian pilasters, crowned in gold, framed the hall, giving it the appearance of a great temple—a flourish of beauty in the heart of a commercial building. Standing in the center of the store’s atrium, Wanamaker, like many of the shoppers milling around him, gazed at a feature unique to his store: a three-story golden organ, the largest in the world, topped by a trumpeting angel.

On that night, as for years to come, the Grand Court filled with the sound of Christmas carols sung by thousands of shoppers, reading the words to the beloved hymns in their Wanamaker Christmas songbooks. As Wanamaker stood in the center of the elaborately decorated bustling hall, “Oh, Little Town of Bethlehem” permeated the Grand Court and spilled out into the depths of the store, christening the new space with the story of Jesus’s birth. Wanamaker recalled that moment in his diary: “I said to myself that I was in a temple,” a sentiment quite possibly shared by the thousands who thronged to the store that night to sing carols and make last-minute Christmas gift selections in his elaborately decorated space. He then offered a gesture of humility: “but may I never say, ‘I built it!’”3

Earlier that same year, Wanamaker had penned a letter to his son Rodman, full of memories of the beginning of his department store. He confessed, “fifty years are crowding upon me.” He reminisced, “I see again the first morning when I swept the shavings and blocks that were about the front door [of the Grand Depot]. . . . And the procession of the years before that, beginning at Oak Hall with its little square box of a store . . . the rapid extensions of the old Grand Depot building. . . . It was splendid.” By this point in his life, Wanamaker had survived the death of three of his children, witnessed the destruction of his beloved summer home, faced down several economic calamities, and lived through a disappointing stint in politics. Finally, the new building he had long ago dreamed of was almost finished. “All these things,” he wrote, “fill me not only with wonder, but with great thanksgiving that I have been permitted to toil so long.” He paused as he often did at major turning points in his business and gave thanks to “the Heavenly Father to have permitted me to live to see so much of His hand of love toward me in the things that are surrounding me to-day.”4 He saw the building as a sign of God’s endorsement of his business and religious activities.

Construction of the last of the three sections of the building had been completed in July 1911. That summer, another celebration ensued. In the store’s atrium, the installation of the mammoth organ was nearly finished and now functioning. Shoppers were invited to witness the first playing of the instrument on July 22 in a dedication ceremony for “The Reigning Monarch of All Instruments.” Giving the organ an even more regal aura, the dedication of the organ and its first playing were timed to coincide exactly with another event across the ocean—the coronation of King George and Queen Mary of England.5 As the processional at Westminster Abbey in London took its first steps to the sound of the church’s organ, Wanamaker’s instrument roared to life backed by a 550-member chorus singing “Zadok the Priest” and “The King Shall Rejoice” to celebrate the king and queen’s crowning and the first music of the Wanamaker organ. The Wanamaker Cadets marched in a parade down the center of the Grand Court that day, in what would become a standard practice for store events and rituals.

In late October of that same year, the store family of 6,500 employees gathered to celebrate the building and Wanamaker’s fifty years in business. The employees processed down the center of the new building before a reviewing stand, singing “Onward Christian Soldiers.” That same evening, they put on a pageant of the origin story of the store and its place in the history of Philadelphia—a history that was retold repeatedly in store literature.6 Linking the store’s history with that of city and nation was one of the many ways Wanamaker and his employees crafted the civic identity of the store.

Concluding the year of celebrations, the ceremonies reached a crescendo with the formal dedication of the new building on the last day of December. A chorus, now one thousand voices strong, sang several compositions commissioned for the occasion. The store organ thundered alongside two cadet bands and the store employee orchestra. During the event, President Taft delivered a speech to the packed room that acknowledged the store’s role in the city as edifying public space. He told the audience, “We are here to celebrate the completion, in its highest type, of one of the most important instrumentalities in modern life for the promotion of comfort among the people” and “for the betterment of the condition of men.”7 Taft revealed that even he was affected by the space: “No one can stand here in this presence, in this magnificent structure without being awe-inspired.”8

The Great Civilizer

Monumental in design on the outside, the interior of Wanamaker’s department store sought to ignite wonder in those who came inside. Wanamaker cajoled shoppers from the comfort of home with advertisements promising not only a cornucopia of tantalizing merchandise from all over the world, but also an education in the latest home and personal fashion, technology, science of living, art, and music. A simple trip to find the perfect pair of red leather gloves trimmed in mink afforded a woman (or man) the chance to hear a lecture, attend an organ concert, tour a tastefully decorated model home interior, or spend a quiet half hour in the store’s art galleries gazing at copies of works from Old Masters and the latest contemporary paintings from the Paris Salons. Capping a visit, a shopper could dine in one of the store’s luxuriously appointed fine restaurants. Visiting Wanamaker’s was not limited to shopping; it offered an educational experience.9 Other department stores in the early twentieth century offered similar delights of music and art, leading them to be described by some as more of a “club house” or an “amusement place” than a retail store.10 While the French and German department stores inspired his choices with their jaw-dropping interiors, Wanamaker took a page from his YMCA work and used these attractions to woo customers for his intertwined purposes of selling and shaping people’s taste—an effort that had religious import.

Wanamaker promoted his stores as “centers of learning” and “an ever-changing educational museum” for the “multitudes” of shoppers that came every day.11 The changing nature of the displays was meant to keep customers’ interest but also offered something that museums and great exhibitions could not—a curated cult of the new, displayed more enticingly, and for sale. Wanamaker wanted people to linger not only to buy, but to learn. He explained that the goal was more than the freedom to browse. As he explained, “One’s eyes are the great gateways to knowledge,” and thus “in Wanamaker’s everyone is free to look, to see, to learn and to enjoy without feeling any obligation to buy.”12 At least according to store literature, learning was equal to buying. Wanamaker’s heavy use of store floor space for cultural offerings suggests that he meant it.

The interior provided a feast for the eyes like many of the department stores of the day; however, Wanamaker took care to construct his store’s central space to echo a great church. If his intention proved too subtle for the everyday, during Christmas and Easter the store often took on the appearance of a Gothic cathedral. For his purposes, Wanamaker reached beyond the buying appetites of the consumer. He wanted to stir their souls and invite them to reach higher moral fortitude. The beautiful interiors of the store and the lavish music programs called the customers to participate in a sensory education in visual and aural aesthetics.13

Music permeated the store. It echoed out of the two exotically decorated concert venues, the Egyptian and Greek Halls. The store employees’ orchestras, bands, and choruses produced music for concerts and ceremonies. And music poured out of the heart of the store into nearly the entire building through the centrally located Great Organ. Wanamaker created his store as a place to shop and for the burgeoning white middle and upper classes to receive an education on taste.14 The store’s anniversary Golden Book unabashedly asserted, “Commerce is the great civilizer.”15 The store’s atrium, the Grand Court, served as Wanamaker’s principal pedagogue.

Atriums, rotundas, and grand halls were common in early department store buildings to allow natural light to permeate the depths of the store. Wanamaker’s architect Burnham employed the feature in all of his department store designs.16 He felt that light was necessary not only to demonstrate the quality of goods but also to make the space uplifting. The Filene’s and Gimbels buildings contained atriums, while Marshall Field’s Chicago State Street store boasted two—with one seven-story atrium sporting a dazzling Tiffany iridescent glass dome ceiling.17 But Wanamaker’s atrium dwarfed them all. A glass rooftop that admitted sunlight floated over the Grand Court seven stories above the Tennessee marble floor. Graceful vaults covered in decorative tile stretched overhead. Lining the five floors that opened to the court were stout, curved balustrades with broad tops apt for leaning, which allowed customers to view the court from multiple perspectives. The Grand Court’s open design allowed it to be repurposed for a variety of store events. Indeed, only a few other American commercial buildings—a handful of new bank buildings in major cities—competed with Wanamaker’s Grand Court in 1911. Only large churches, courthouses, and train stations offered similar stately spaciousness.

While the atrium was unusual in its breathtaking size and décor, Wanamaker made it stand out in other ways. He gave his atrium a name, the Grand Court of Honor, a gesture to its hoped-for significance. Its name was derived from the 1893 Columbian Exposition’s central open area of lagoons and pedestrian promenades, the Court of Honor. In Chicago’s White City, the spectacular Court of Honor functioned as the central axis of the extensive fairgrounds, linking the most prominent buildings with one another in a harmonious vista decorated with theatrical statuary and water features. The exposition’s court drew the fair’s variety of buildings into a unified whole.

Wanamaker’s Grand Court functioned similarly. Connecting the multi-staged building project, it was the heart of the store and the locus of store ritual. It gave shoppers a breathtaking perspective that hinted at the store’s size from inside. But the Grand Court did more than knit together parts of the massive building: it provided a place to display goods and a large flexible civic space repurposed for ceremonies, concerts, religious events, and holiday celebrations.

The Great Organ and the Eagle

Burnham and Wanamaker designed the interior of the new store down to the minute details, adding fluted columns, tray ceilings, intricate moldings, sweeping staircases, rich fabrics, elegant lighting, marble, mosaics, tile, and decadent wood paneling throughout the store’s public rooms to reflect the latest in elegant interior design. Specially themed rooms took on an additional opulence. Among these were the multistory Egyptian and Greek concert halls and a group of adjacent smaller rooms—the Byzantine Chamber, Louis XIII and Louis XIV Suites, Empire Salon, Art Nouveau Room, and Moorish Room. The rooms that sold women’s dresses, Little Gray Salons, were outfitted to look like a collection of small Parisian luxury shops. Nearly the entire store was a spectacle of refinement.

Shining and gleaming with the latest in building design, the store felt different with its climate-control systems that circulated cool or warm filtered air as needed. The ventilation systems fostered an atmosphere that was meant to be refreshing to shoppers (and those who worked at the store) as they came off the buzzing city streets into a well of calm and beauty. The multitude of services offered to customers—or store guests, as Wanamaker liked to call them—unburdened them of hats, coats, and packages. Thoughtful touches aimed at customer comfort and delight were spread throughout the building. But easily the most seductive part of the building was the Grand Court.

For customers entering the store through one of its majestic colonnaded entries that suggested an ancient Greek or Roman temple, the Grand Court, located in the center of the store, was easy to stumble into, and the wide marble arches beckoned customers into the vast open space. Its size alone supplied drama. The elegant architectural details gave the room a palatial feel, drastically different from many stores that felt confined and cluttered. A store publication described the role of the Grand Court as “an imposing and artistic center for the store, binding all the rest together around it, and creating a certain atmosphere that the most remote corners of the store feel bound to reproduce.”18 The Grand Court served, too, as the spiritual center of Wanamaker’s store.

Two features dominated the immense court and communicated Wanamaker’s commitments—a colossal bronze eagle sculpture and the majestic organ, both from the 1904 Louisiana Purchase World’s Fair in St. Louis.19 The Grand Court was connected to the great exhibitions, and the eagle was another link between the store and the fairs. Wanamaker purportedly purchased the mammoth eagle to serve as an example of fine art statuary along with the statues of Joan of Arc, the reproduction of Diana de Gabies, and the Polyhymnia scattered throughout the store.20 No small addition to the Grand Court, its procurement necessitated reinforcing the atrium’s floor to carry the weight of the 2,500-pound bronze sculpture and its large 4,500-pound granite base.21 The placement of the eagle in the center of the court created other roles for it. Visible from the edges of the court and from the floors above, it drew shoppers into the heart of the store. For some, it was a curiosity, while others came to view it as a familiar friend. As with other public bronze sculptures, shoppers and their children could not resist touching the eagle, making its tail feathers and talons glow from the caresses of millions.

The eagle signaled to customers the store’s patriotism. Frequently photographed surrounded by American flags and the organ, it represented God and country, powerful symbols of a blossoming Protestant civil religion. Ever present during the concerts and public functions, the sculpture provided orientation in a sea of people, and, perhaps because of this, the eagle quickly became a symbol of the store, much like the exterior grand clock at Marshall Field’s. Generations of Philadelphians made the eagle their rendezvous spot, making the phrase “Meet me at the eagle” a well-known shorthand for a convenient place to meet in central Philadelphia. The eagle was something to see and somewhere to meet.

The eagle also drew attention to the other occupant in the Grand Court imported from the St. Louis Exposition, the Great Organ. If shoppers initially missed the organ, the eagle’s gaze drew their eyes to look at it towering above. From the beginning, organ music held a significant place in the life of Wanamaker’s stores. He installed his first organ at the Grand Depot in 1876 in a period when the popularity of organs was on the rise in home parlors, stunning new and remodeled churches, and concert halls and outdoor tabernacles like the one at Chautauqua, New York. A gorgeous instrument, the Grand Depot organ provided a visual and aural focus in the converted train shed. Covered with intricately carved wood paneling and topped by an angel holding a torch, the organ offered a focal point for special store events and a backdrop for decorations. Other early department stores followed suit and installed their own instruments for musical concerts and entertainment. At the turn of the twentieth century, organ music began to fall out of favor in shopping settings, even while it experienced a resurgence at movie theaters, concert halls, and churches. But organ music held a significant place in the life of Wanamaker’s store as early as the Grand Depot.22

For years, the business day at the store began for employees with an optional time of singing, inviting employees to “come when you like and enjoy it.”23 To aid this exercise, Wanamaker produced employee songbooks that included Christian hymns and patriotic tunes.24 In a 1917 Employee Songbook, Wanamaker explained to them why he felt this was important: “Starting our days in this business place where thousands are employed and thousands more come and go, with hundreds” of joined voices singing, “smoothes out the wrinkles, clears out the cobwebs and sweetens the spirit at the beginning of the day.”25 He believed that “music inspiration should be a part of the daily lives and work, as well as a form of relaxation and amusement.”26

The construction plans for the new Philadelphia store originally included two large organs for the store’s Egyptian and Greek concert halls. The plan shifted sometime in 1907 when it was decided that a large organ would be installed in the Grand Court. Originally, elaborate decorations dominated the Grand Court design. The decision to add an organ to the court led to a dialing back of the decoration scheme. The decision was an unusual choice in 1911 and a major change to the space. Two explanations for the decision to add an organ circulated. One story gave the credit to Rodman. By this time, he had moved back from France and was participating in the day-to-day management of the two stores. Wanamaker had encouraged his son to take organ lessons, and Rodman had grown up playing the organ at Bethany.27 It was during “one of [Rodman’s] routine tours of inspection” of the new store as it was under construction that he saw “the possibilities of the Grand Court as a music center” and exclaimed, “I want the finest organ in the world built up there above that gallery!”28

Mary Vogt, one of the longtime store organists, told a competing story. She suggested that the idea of placing a magnificent organ on the second level of the Grand Court materialized after the devastating fire at Lindenhurst in 1907 destroyed the two-manual Roosevelt organ that John Wanamaker had installed for Rodman on the landing of Lindenhurst’s grand staircase.29 Since construction of the new store was still ongoing, Vogt claimed, Wanamaker decided to build an enormous organ in the court to honor his only surviving son.30

Whether for sentimental or visionary reasons, the Great Organ in the Grand Court carried several associations. It connected the store with many middle- and upper-class homes where parlor organs were standard and occupied a prominent place. Home organs also were read as a sign of a family’s religious devotion and social status.31 The size and location of the Wanamaker organ visually aligned it with theatre-style Protestant churches of the period that were busily adding gigantic organs to their sanctuaries and prominently placing them in the chancel in the front of the church, elevated above the first floor with an eye-catching array of pipes soaring upward.32 Bethany Presbyterian was one of these churches.

The choice to place an organ in the Grand Court posed challenges. An instrument needed to fill not only the court but the surrounding floors opening to the atrium. Was it possible that a single organ could be built with enough power to manage the job? Research revealed that the cost of building an organ from scratch was unmanageable, and it would take years of construction to complete the project.33 The Wanamakers began searching for a large organ to buy for the court and discovered that the 1904 St. Louis Exposition’s Festival Hall concert organ lacked a home. The Festival Organ was supposed to be sold by the end of the fair; however, no one had stepped forward to purchase it.34 Wanamaker had heard the organ play during his visit to the fair and was delighted when he discovered that the instrument sat in storage awaiting a buyer. He sent his “organ man,” George W. Till, to inspect it and, after receiving positive reports despite some damage from disuse, purchased it for a heavily discounted price.35 Till arranged for the delicate transport, while Wanamaker made it into a traveling advertisement for the new store. Eleven freight cars carried their musical cargo across the country with each car displaying a muslin sign declaring, in capital letters, “ST. LOUIS WORLD’S FAIR ORGAN / JOHN WANAMAKER PHILADELPHIA.” Once again, a piece of one of the Great Expositions had found a home in Wanamaker’s store.

Installation of the organ began in the fall of 1909 while the last phase of the building was still under construction. The Festival Hall organ’s original façade was an unimpressive wall of pipes in a plain case. Wanamaker arranged for a new case and exterior pipe display with the building’s architect, Daniel Burnham. Reminiscent of a church organ, the new composition placed an ornate Renaissance-style tower in the center, flanked by two smaller towers. Crowning the central tower, a life-size angel balanced her delicate feet on an orb as she blew two horns. Behind the angel, 22-karat gold leaf gilded the visible pipes, and an ivory case hid some of the instrument’s apparatus.36

Though workers had toiled nonstop to finish the organ in time for the store’s dedication, the organ’s first playing in July of 1911 ended up a disappointment. The organ was not fully complete, and it was obvious that, despite its immense size, it did not have the power necessary to fill the court and surrounding floors with sound. Those in attendance described the sound as “puny.”37 For two years, workers had manipulated the instrument’s pipes to fit in hidden rooms around the court. To increase the organ’s power, they needed more pipes. Rodman Wanamaker hired an in-house crew of specialists to begin the expansion. Making the organ powerful enough for the Grand Court required sacrificing additional centrally located retail floor space to the organ. A workshop was opened on-site, and work commenced even as the organ became a central part of the store’s daily life. The project unfolded over a twenty-year period with a series of major enlargements in 1914, with the addition of four thousand pipes, three thousand more pipes added in 1917, and an ongoing series of enhancements and tweaks that stopped in 1930, long after John and Rodman had died.38

Making the organ larger did improve its voice and volume. It also gave the store ongoing bragging rights for the world’s largest organ—and it was promoted as such, even when that was not entirely true. In the end, the organ contained approximately 28,500 pipes with 461 ranks.39 Called the Great Organ, it merited its own guidebook discussing the sound, beauty, number of pipes, stops, pedals, and other trivia for interested customers.40

The installation of the organ had been a gamble. In the end, it made an impression aurally and visually. Perched high above the ground floor, its lustrous golden beauty sometimes eclipsed the merchandise by drawing customers’ gazes.41 In an area that held well over fourteen thousand people, Wanamaker and his team of workers used the organ as the ever-present accompaniment to ceremonies, musical extravaganzas, and holiday events, with the organ jumping back and forth from concert instrument to religious instrument, depending on the occasion.42 A professional organist was hired and a daily recital schedule was developed, except on Sundays, when the store was closed. Some customers timed their visits to the store just to hear the organ play, while others were surprised by the massive instrument thundering to life.43 Certainly, there were customers who avoided the store when the organ played.

Any doubt store guests had of the organ’s status as a quasi-religious symbol would have quickly evaporated when they read the essay by French writer Honoré de Balzac on the guidebook’s opening page. First included in the 1917 booklet, “The Organ” became a mainstay in the guidebook. Balzac’s essay majestically described it as “the grandest, the most daring, the most magnificent of all instruments invented by human genius” and “a whole orchestra in itself.” His tone turned religious when he explained that the organ is “a pedestal on which the soul poises for flight forth into space . . . to cross the Infinite that separates Heaven from Earth!” The organ served as a tool for prayer; “nothing save this hundred-voiced choir on earth can fill all the space between the kneeling men and a God hidden by the blinding light of sanctuary.” Above other instruments, Balzac claimed, the organ produces music that is “strong enough to bear up the prayers of humanity to Heaven.” Exclusive to no faith, the organ’s prayer is “upspringing with the impulse of repentance, blended with the myriad fancies of every creed.” The Balzac piece ends with the startling assertion that from “the chanting of a choir in response to the thunder of the organ, a veil is woven for God.”44

While Balzac’s essay implied the spiritual and religious significance of an organ, Alexander Russell, professor of organ music at Princeton University, wrote an essay describing playing the Wanamaker organ during a two-week period as a guest musician in which he more explicitly evoked the divine.45 For Russell, something magical happened when he played at Wanamaker’s. In an organ guidebook, Russell shared the experience of playing a Bach chorale: “As the melody of the superb hymn poured forth, the angel’s trumpet seemed to be sounding and the great Court became a temple.” He confided, “I had a sensation too often denied the performer; a delightful thrill, cool and exhilarating, passed up and down my spine. . . . The effect was electrifying.”46 This experience was more than a moment belonging to his imagination. When he finished his recital, he turned to look down into the court and discovered, “Below were crowds of people, standing and sitting everywhere. Above, the balustrades of five galleries were lined with crowds. . . . The sound of the organ had created this great audience.”47

Russell had found that the organ’s power cut across class lines, drawing listeners together and, as Wanamaker hoped, elevating them. Since the organ was placed in a centralized location, it was hard to avoid its sound. Many sought it out, attracted by the music. The guest musician Russell, in the same piece, recalled the daily visits of a bank clerk, motor salesman, and engineer who sometimes phoned up requests to the organist. Russell reflected, “They may not be on the subscription books of the opera or of a symphony society, but they know who Schubert was because they asked for him.”48 But Russell also received less lofty requests that he cheerfully played despite the incongruence. He explained, “In ten days, I played over one hundred different compositions, varying from the classics to ‘I Hear You Calling Me.’ Antithesis, do you say? Perhaps, but I believe that the sun-god of music shines in the little valleys as well as on the great mountains.” He smugly added, “Not every one can live on a mountain.”49 Later in the essay, Russell appeared to understand Wanamaker’s mission for the store organ. He closed with this claim: “This great organ creates music-lovers, not once in a while, but every working day in the year. It brings music into the daily life of the people.”50 The first store organist, Dr. Irvin Morgan, had a similar observation of the organ’s musical effect on people. He noted the positive reaction of store employees, “I have seen them raised from nervousness and weariness in their work to cheerfulness and confidence in a manner that nothing else would produce.” He, like Russell and Wanamaker, understood the organ as a “refining influence” on the class of people who were employed at the store.51

Music had always been a central component in the store’s life. Wanamaker, and now his son Rodman, routinely commissioned pieces of music as they did with art, and developed a robust music program organized around the cadets and the Robert Ogden Association’s bands, orchestras, and choruses. An organ concert was given several times a day. More music poured out of the Greek and Egyptian Halls and the Crystal Tea Room.

Music was everywhere at Wanamaker’s and other American department stores. As historian Linda Tyler notes, “Department stores were not merely centers of buying and selling, but also grand theaters of cultural expression and consumer manipulation. Music played a prominent role in this new drama of consumption.”52 Other stores also created employee bands and music groups, much like Wanamaker’s, while Strawbridge and Clothier, another Philadelphia store, maintained a large touring chorus, as did Chicago’s Marshall Field’s. Such efforts sought to reap not only goodwill but also higher sales. Used to draw customers into the stores, music productions most often accompanied sales events, holidays, and the premiere of new fall and spring fashion collections.53 Wanamaker’s organ consultant and sometime guest organist launched a new program for the store when he suggested the Grand Court host an after-hours concert. In March 1919, when the store closed, workers moved in to remove the display cases on the ground floor and add thousands of chairs on the main floor and the six floors of balconies. It was a startling transformation. The Philadelphia Orchestra and its famous conductor Leopold Stokowski played that night to an audience of twenty thousand. Charles M. Courboin was the organ soloist for the successful night, which began a new tradition. Over the years, star organists, popular composers, and musicians, including Richard Strauss and John Philip Sousa, played at Wanamaker’s. The music Wanamaker promoted had cultural authority and contributed to shifting the canon of tasteful music and art in the United States.54

By the early twentieth century, store music productions earned prominence by tapping “well-known artists” to give special concerts no longer tied to specific retail events.55 Retailers also tested the practice of having hidden musicians throughout the store play background music for shoppers. It soon became a best practice, with the virtues of music for shoppers and employees extolled by Dry Goods Economics and other professional retail magazines.56 Wanamaker led the way among retailers, becoming what Tyler describes as “the most ambitious and audacious of music impresarios among American merchants.”57

The Grand Court took on many guises depending on the event and decorations. For day-to-day operations, it provided bright, ample space for merchandise in glass-and-wood display cases. For special music concerts, patriotic extravaganzas, and holiday presentations, display cases were rolled away to make room for the crush of the crowd or, for more formal events, chairs. The open floors above became viewing galleries from which to witness the pageant of activity below and around the store.

Holidays and Holy Places

Wanamaker’s store became famous for its sumptuous holiday decorations, especially for Christmas and Easter.58 The practice of decorating the store lavishly for religious holidays began at the Grand Depot. As Wanamaker built out the store, the holiday decorations grew more dramatic. In 1893 Wanamaker purchased the Westinghouse lighting column he saw on display at the Columbian Exposition and put it in the central aisle of the old store. Installed in time for Christmas, it showed off the latest technology from the exposition and was also employed for a different purpose. The column stood in the center of the building with twenty-six hundred lamps, whose light traveled from the base all the way to the top “when it shoots off into forked lighting to the four points of the compass, emptying into revolving spheres” that whirled and flashed. The light then faded, only to repeat once again. Wanamaker’s designers built a Christmas display around the column and wrote a new interpretation of the light and buzz of the machine. Store literature described the forked bolts of light emanating from the column as symbols of the “Bethlehem light; hidden sometimes by the traditions and misconceptions of men.” The column showed “the heaven, the light which lighteth every man.”59

In 1894 store decorators constructed a “winter fountain” in the transept of the center aisle of the store. The fountain, covered in lights and greenery, featured a large twenty-four-foot basin and at its center a statue of “winter,” a woman in a “loosely flowing robe” who held “above her head 240 jets of water” that shoot into the air, with the water coming back down around the statue. A dome lit the water with colors moving from red to purple to orange, a series that the Watchman interpreted as sacrifice, passion on the cross, and a crown of glory.60 Angels made a regular appearance at the Grand Depot; dozens of angels with outstretched wings perched on the balconies surrounding the depot’s organ at Christmas and Easter. But decorations at the Grand Depot frequently looked cluttered, with statues, garland, and special exhibits crammed into the limited open areas of the store. The new building with its expansive Grand Court furnished a larger canvas for Wanamaker’s team of designers to adorn.

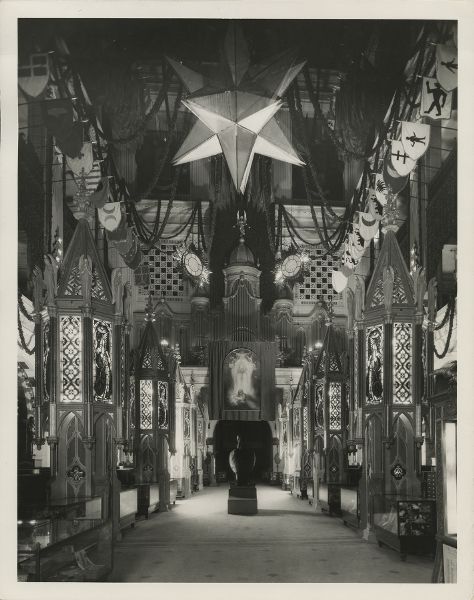

Turning the Grand Court into a cathedral for Christmas was a natural choice. In many ways, it already resembled a church with its seven-story ceiling, marble floors, sweeping archways, and large pipe organ. Over the course of the first decade of the new building, the Wanamaker art department designers slowly built out the cathedral composition, adding layers of details onto the previous year’s design. As the decorations grew more complex, an outside firm was hired to create some of the decorations. Around 1919, a full-scale Gothic cathedral plan emerged in the store and became an annual tradition. In the decades that followed, the store would bring together elements from European Gothic cathedrals, at times, authentically reproducing a particular element such as a rose window from the Reims Cathedral, a place Wanamaker had visited. The Grand Court’s cathedral was not the first dalliance by the Wanamakers with Gothic architecture.

Appropriation of medieval Catholic architecture and art was a part of a larger movement by Protestants to reinterpret them as quintessentially Christian. Since the 1830s, Protestants had been actively stripping away Catholic associations and recasting Gothic architecture and art as symbols of a nostalgic “premodern” time of Christian unity, simplicity, and authority.61 Cathedral design tapped into a larger trend that began in the nineteenth century. The aesthetic and material desires of Protestants had found expression in architecture. Starting in the 1840s and continuing in a series of waves stretching into the first part of the twentieth century, a Gothic Revival in architecture took hold in the United States.62 Pioneered by Anglicans in England and adopted first by American Episcopalians, soon Unitarians, Presbyterians, Methodists, and Congregationalists were raising scaled-down Gothic cathedrals across the country. This trend was meant to move away from regional particularities to a universal and romantic Christianity rooted in an interdenominational Protestant ethos. Its participants found within the beautiful lines and ornate design the values and ideas of Protestantism. Churches across denominations embraced the ornate style. The Gothic style thrived in Philadelphia with two churches leading the revival—St. James the Less and St. Mark’s.63 Both were Episcopalian congregations founded within a year of each other and served Philadelphia’s established and emerging upper class.

Figure 5.1. Interior view of a crowded John Wanamaker’s Grand Depot transept decorated with hundreds of angels for Christmas. Shoppers and employees fill the floor space and surrounding galleries. The basic structural elements of the transept became a part of the design of the Grand Court. Eye-catching and religiously themed decorations were used for holiday displays from the earliest days of Wanamaker’s business. The Depot’s organ pipes are visible on the right of the picture. Musicians stand on a balcony in front of the organ; the arrangement was replicated in the Grand Court on a larger scale.

Rodman Wanamaker had become deeply invested in the Gothic Revival movement starting around the time of his marriage to Fernanda. The year after Rodman graduated from Princeton, he married Fernanda de Henry (sometimes spelled de Henri) in the church where she was baptized and confirmed, St. Mark’s Episcopal Church. Although the couple moved to Paris for a decade, their ties with home remained enduring. Fernanda served on the church’s altar guild, and she was deeply attached to her home congregation.

His father and family visited often, and Rodman and Fernanda traveled back to the United States too. The rhythm of the bicontinental lifestyle came to a sudden halt when at the age of thirty-six Fernanda fell gravely ill and died. Rodman was devastated. He returned to the United States and, in his grief, found solace in Fernanda’s church, the site where they had married. Rodman’s return to Philadelphia came just as the Reverend Dr. Alfred Mortimer was settling in as new rector of St. Mark’s. Devoted to High Church ritual complete with incense and rich fabrics for vestments, Mortimer envisioned a decorated interior that aided the worship and ritual experience of the church.64 Under his leadership, the congregation’s membership expanded rapidly with many of Philadelphia’s wealthiest residents as its members. With Mortimer’s encouragement, the congregation answered his call for enhancing the church’s interior and ritual pieces. New flooring was installed, and the altar was covered in marble. He believed that beauty and refined decorations heightened emotion in the worship.

Mortimer guided Rodman’s donations. Within two months of her death, Rodman and the church had agreed to the addition of a “Lady Chapel” for his sweet Fernanda. He committed to more than the structure; he also promised to furnish the chapel with an elaborate altar and communion ware. Underneath the altar, a crypt was built. Fernanda, who had been buried at the churchyard of St. James the Less, was moved to St. Mark’s upon completion of the crypt.

Rodman loved beautiful objects and continued to make substantial contributions to St. Mark’s on and off over the years, stopping for a time when he remarried, only to resume after his divorce. He made a name for himself as a benefactor through a series of grandiose and extravagant donations to Anglican churches. He gave Westminster Abbey a jeweled processional cross and the royal family’s estate church a bejeweled Bible. In 1901 he donated two large Louis Comfort Tiffany stained-glass windows, “The Word” and “Contemplation,” in memory of his wife to the American Church in Paris.65 Through donations like these, he took on the role of European aristocracy who bestowed treasures to the church.66

The Lady Chapel was Rodman’s first Gothic memorial structure. The sudden death of his brother Thomas Wanamaker in 1908 spurred Rodman to undertake another project. This time he involved his father in constructing a family mausoleum. They chose the churchyard of St. James the Less, Fernanda’s first resting place before she was moved to St. Mark’s crypt.67 None of the Wanamakers were members of St. James. In consultation with the church leadership, Rodman hired a local architect, John T. Windrim, to draw the plans for the Wanamaker mausoleum. Windrim was familiar to the family. He was their choice to design the Wanamaker branch of the Free Library of Philadelphia in the Grays Ferry neighborhood, and the new Lindenhurst after it was destroyed by fire. However, Windrim did not have free rein on his design. The Wanamakers’ decision to locate the mausoleum at St. James the Less came with some restrictions. The Gothic design of the structure needed to complement the church building, one of the finest examples of English Gothic architecture in the United States—it was a replica of a thirteenth-century church from Cambridgeshire, England.68 To ensure accuracy, English-born and trained architect Henry Vaughan of Boston, who later went on to design other famous American Gothic churches, including the Washington Cathedral and three chapels of St. John the Divine, consulted on the project. The Wanamaker Tower was built during the same period the Wanamakers constructed their new store building in Philadelphia, and was completed in 1908. Dedicated to Thomas, who had died the year before, the tower accommodated two small chapels and a crypt. The bell tower received a fifteen-bell carillon in 1915.69

At Christmas and Easter, Gothic architecture brought the Grand Court’s church-like qualities to the fore. In the Grand Depot, Wanamaker had celebrated Christmas in its religious vein with music and decorations in the middle of his commercial empire. He continued the tradition in his 1911 building with intricate designs executed by his able designers that sought to create a Protestant Christmas experience—carefully crafted and staged to please a broad audience and symbolize Protestant Christian unity.

Wanamaker’s store holiday displays proselytized thousands of shoppers on how to decorate and on what the focus of Christmas ought to be. Embracing the neo-Gothic movement’s fascination with a medieval aesthetic, the Wanamakers instructed their decorators to design Gothic cathedrals with dazzling shrines devoted to the story of baby Jesus. Here, the authenticity cherished in Tanner and Munkácsy’s paintings was left behind for a sensual and highly imaginative concoction of shining, flowing fabrics, sparkling jewels, stunning paintings, and colorful light, all with the Great Organ visible in the background, filling the building with the sound of church at appointed hours. Symbolism was everywhere, telling a number of stories all at once.

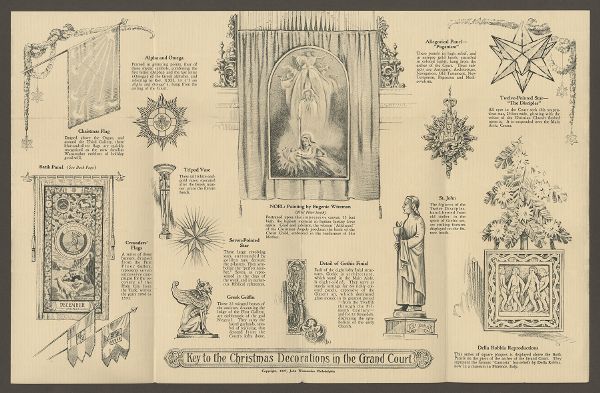

The Wanamaker cathedrals required a guidebook and signage to decipher the rich symbolism. The religious meaning of the holiday was not discreet at Wanamaker’s; rather, images of the Christ child in his mother’s arms, paintings of the Magi, and biblical quotations conveyed the season’s Christian focus.70

For the 1926 Christmas, a collection of twelve murals depicted “The Progress of Civilization” through images of twelve countries. The series began with Egypt, followed by Judea, and culminated, not surprisingly for Wanamaker, with France and America. Highlighting the importance of the store’s Christmas decorations, the guidebook noted that “there is no place, save their own hearthstones, where the public feel more completely at home than in this vast and hospitable hall.” The store’s opening and closing each day was marked by the singing of “beloved Christmas Carols” where “all listen” and “many join the singing.” The publication pointed out various Christian symbols: “The five-pointed stars signify ‘The Creator’” and “the stars with seven points symbolize ‘The Perfect Number’” while the “twelve-pointed stars are ‘The Disciples.’” Backlit in a stained-glass window was “The White Cross of Light,” the cross representing God and the Holy Spirit. Twelve statues of the disciples, made to look like carvings that belonged in a European cathedral, appeared year after year in different places in the Grand Court. Store guides named each disciple and explained the symbolism of what each held in his hands or what stood at his feet. Byzantine columns glittered with gold and paste jewels at either end of the court. Framing the entrance into the court, twelve large crosses stood surrounded by red lights and emblazoned with the first two letters of the name Christ in Greek. Salon paintings made appearances in the court if they matched the theme. For instance, Les rois mages, from the 1924 Paris Salon, was displayed when the Magi were a central element of the year’s theme.

Figure 5.3. “The Grand Court at Christmas” guidebook. A key to the symbolism of a Wanamaker Christmas Cathedral. On the inside cover, the booklet quotes Wanamaker: “I said to myself, I was in a Temple.”

Figure 5.2. Wanamaker’s Grand Court at Christmas time, ca. 1920s. Many of the decorations were used year after year in the displays as more pieces were added.

The next year, for the 1927 Christmas, the Wanamaker cathedral shared some of the same elements from the year before and added special Christmas flags of blue and silver, and a collection of Crusaders’ flags to represent the seven campaigns to retake the Holy Land from 1096 to 1370. Gracing the arches in the court, “flashing clear-blue stars” represented “The Creator,” and a collection of twelve batik panels represented the twelve months. Four other panels illustrated “the Elements—Earth, Air, Water, Fire.” Allegorical panels finished in an antique gold patina and encircled by lights represented “Antiquity, architecture, navigation, Old Testament, New Testament, and Paganism,” among others. A rotating collection of reproductions of knights and military regimental flags, hand-painted on silk, added a layer of romance and mystery to Grand Court decorations.71

People responded to the decorations with solemn awe. A store advertisement noted that “many men remove their hats” when they visit Wanamaker’s Grand Court at Christmas and that visitors are “transported out of a hurly-burly world” and “are caught up with the radiance and symbolism” of the holiday.72

At the center of the Christmas display was the Nativity—the Christ child cradled in a manger dramatically lit by a beam of light streaming down from the ceiling.73 Later, Wanamaker commissioned a French artist to paint a large, eye-catching canvas with the baby Jesus and Mary surrounded by angels and bathed in a golden light. For the merchant and at least some of his customers, the message was clear.74 Christ was at the center of Christmas and at the center of the commercial world of his department store. But this space, like all sacred space, was contested.75 Some non-Christians felt excluded, as did those who abhorred the placement of a Christmas spectacle in a store; yet thousands did respond to Wanamaker’s call to share the holidays with him, and for many it became a part of their Christmas tradition to participate in the department store’s festivities in the Grand Court, creating a ritual and religious association with the space.

Singing Christmas carols transformed into a Philadelphia holiday staple starting in 1918, when Wanamaker invited shoppers to sing Christmas carols at the end of the shopping day in the weeks leading up to Christmas. Thousands gathered nightly in the Grand Court, clutching their store-printed souvenir songbooks, which Wanamaker first printed in 1918. Each songbook opened with an edifying message from Wanamaker to the carolers. In the first songbook, the message inside the cover framed the songs as anthems proclaiming the glory of God:

Glory to God! “the sounding skies

Loud with their anthems ring—

peace to the earth, good-will to men,

From heaven’s eternal King!”

The following year’s edition carried the title “Christmas Carols in the Grand Court” and opened with a theological poem:

Lie circles widening round

Upon a clearer, blue river,

Orb after orb, the wondrous sound

Is echoed on forever:

Glory to God on high, on earth be peace,

And love toward men of love—salvation and release.76

Carols for 1919 included “Good Christian Men Rejoice,” “Joy to the World,” and “Once, in the Royal City of King David,” as well as “O Come, All Ye Faithful.”77 Emphasizing religious hymns over seasonal tunes, Christmas caroling at Wanamaker’s was a Protestant Christian event. Even as the songbook grew over the years and patriotic songs were added to the repertoire, the last hymn was always “Onward Christian Soldiers.”78

Wanamaker thought of Christmas as far more than a holiday for making money, although he did realize that it was one of the most lucrative seasons in the life of his store. He resisted candy-coating the holiday and persisted in conveying his Christian devotion. In another undated Christmas songbook, he plainly articulated his belief: “For thousands of years the expectant world waited for the Christmas that came with its wonderful gifts over which the angels sang ‘peace on earth, good will to men.’” Wanamaker did not want shoppers to confuse his store’s grand decorations with another understanding of the holiday. He attested, “Christmas is a man born, not a sentiment.” Suggesting a way to align oneself properly with the intent of Christmas, he instructed shoppers, “To get right with Christmas would make men right with one another in this old world, almost falling to pieces. Let us pay real tribute to Christmas.”79 The “real” Christmas was the one Wanamaker presented—it was a mix of Jesus and the popular medieval aesthetic of the neo-Gothic movement.

Easter received similar treatment at Wanamaker’s, and the store sometimes outstripped local churches’ efforts to celebrate the important day in the Christian calendar.80 One store advertisement told shoppers to visit the store during Easter for “spiritual refreshment and happiness” that could be found among the sea of flowers in the Grand Court. Simply by “standing in the Grand Court,” shoppers received reassurance that “it would be impossible to fail to receive a sense of immense blessing that Easter time again confers upon the world” and that at Wanamaker’s they would find “the true Easter spirit.”81

Figure 5.4. Munkácsy’s Christ before Pilate Easter crowd. During the holidays, Wanamaker’s Grand Court filled with people for the special ceremonies, organ and other musical concerts, and at Christmas time for caroling. The eagle sits in the center of the crowd and a decorative placard shares information about the painting and the artist.

Every year, the Grand Court was awash in decadent arrangements of Easter lilies, angels, palms, educational displays of glittering ecclesiastical vestments, and stunning tapestries.82 Embellished lampshades that hovered over store counters in the Grand Court proclaimed, “He is Risen!” and “Alleluia!” At Wanamaker’s, Easter constituted flowers, spring fashion, and Jesus’s resurrection.

In 1893 a lawn of green grass was cultivated along the arcade leading from Chestnut Street, and “cherry-trees and apple-trees” appearing to be in full bloom decorated the pastoral scene. On balconies above, boys working for the firm sprayed “the perfume of apple blossom down upon the people and the trees.” The Store News likened it to walking through a place where “the perfume of mothers’ prayers”—and thus home—misted down on the shoppers.83

Figure 5.5. As with the Christmas displays, Wanamaker’s Easter needed interpretation as well. Here is an interpretative placard from 1932 explaining the intricate Christmas symbolism throughout the Grand Court. The angel statue appears to be presenting the placard to viewers. Munkácsy’s Christ before Pilate can be seen in the right-hand corner of the photograph. The Easter lampshades and the biblically themed shields used for many years are also visible.

Lent had a place at the store festivities as well. Prior to 1922, during the forty days leading up to Easter customers were specifically invited to the store’s art galleries for quiet contemplation of two Munkácsy paintings depicting Jesus’s trial and crucifixion. After John Wanamaker’s death, the paintings moved to a place of prominence in the Grand Court during the Lenten season.

Civic Virtue

For national holidays and special events, the Grand Court served as a patriotic ritual site. Flags were a constant presence at the store. Clusters of American flags trimmed the store entrances, hung from the building, adorned the Great Organ, at times surrounded the eagle, and were ceremonially carried through the store by cadets. On the announcement of the armistice in 1918, hundreds of American flags were displayed in the store. In addition, Wanamaker and his son Rodman had custom flags created for store events and special anniversaries. Each of the different branches of the Wanamaker Cadets had their own flags that were used for store ceremonies.

Store newspaper advertisements publicized the public rituals. Frequently, the celebrations and commemorations extended over the entire day to give shoppers ample opportunity to experience the store’s ritual offerings. Ritual schedules were listed with times and descriptions in newspaper advertisements announcing the schedule of mini-concerts featuring the store’s bands, chorus, and the organ, making it possible for a shopper to encounter a part of the celebration throughout the day.

An example of a special ceremony was the one following the death of former president Theodore Roosevelt in 1919. A solemn tribute took place in the court, with Wanamaker’s military band and his cadets serving as the liturgists for the ceremony. The court, decorated in flags, included a display of Roosevelt’s picture and a program for the event to start at two o’clock sharp. In crisp military fashion, the liturgy unfolded:

- 1. Chopin’s funeral march

- 2. Cadets march in to the beat of the drum

- 3. Present arms and three rolls of the drum

- 4. Lead Kindly Light, Brass Quartet

- 5. One minute of Silence

- 6. Taps

- 7. Cadets march out.84

Different versions of the liturgy would be repeated throughout the day, cycling through the store’s military bands, orchestras, and other musical options Wanamaker’s had through its employee programs. Patriotic events peppered the schedule of the Grand Court with the ever-present Wanamaker Cadets always ready to lend an official and military flair to the proceedings.

Just as the organ maintained a religious tone in the Grand Court, so Wanamaker found a way to keep a patriotic and civic tone in other parts of the building with the installation of a series of plaques mounted on the store’s pillars and walls. The messages conveyed the civic virtues Wanamaker held most dear to those who paused and read the signs. In case someone missed them, store guides discussed the plaques and their meaning. They included excerpts from some of the same speeches found in the booklets that Wanamaker distributed to shoppers, including George Washington’s Farewell Address and Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address. In addition, one plaque displayed Henry Lee’s oft-quoted eulogy of the first president, “First in War—First in Peace—First in the Hearts of His Countrymen.”85 Linking his methods of retail with the founder of Philadelphia, Wanamaker installed a plaque honoring William Penn with a quotation from his Philadelphia Elm Treaty: “We are met on the broad pathway of good faith and good will so that no advantage is to be taken on either side, but all shall be openness, brotherhood and love.”86 Nearby, Ulysses S. Grant’s plaque offered a series of quotations from his presidency, about the Civil War, and regarding his visit to the store in 1877.87 Wanamaker had mapped the history of Philadelphia and the United States onto the history of the store. He had turned the ground floor into a patriotic museum.

On the side of the court where President William Howard Taft had stood for the dedication of the store, a brass star marked the spot on the marble floor, with a plaque explaining the star’s significance. For Wanamaker, an active Republican, Taft’s visit was a significant nod to his efforts for the Grand Old Party, as well as a symbol of shifting attitudes about the interaction of politics and business. For Wanamaker, civic virtue was intertwined with moral virtue. To be a virtuous individual was to embrace civic virtue. One needed to be moral to be a good citizen. Wanamaker himself joined the ranks of great men he had chosen to be honored on the columns with a plaque reiterating his own words on the store’s cornerstone: “Let those who follow me continue to build with the plumb of honor, the level of truth, and the square of integrity, education, courtesy, and mutuality.”88 The plaques complemented the pictures hanging in his personal office upstairs, where images of Ulysses S. Grant, Theodore Roosevelt, and Abraham Lincoln decorated the walls, along with copies of the Gettysburg Address and other American history memorabilia.

In 1881 and in the following years, Wanamaker distributed booklets to shoppers with a copy of the Constitution, the Bill of Rights, Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, and George Washington’s Farewell Address. There was no charge for the booklets as long as customers vowed to read the entire contents and sign a pledge on the back cover to seal the promise that they had read the words.89

John Wanamaker, whose birthday and store anniversaries received ceremonial attention every year while he was living, remained a part of the store’s ritual rhythm after his death. For many years, on his birthday employees would place one of the several oil painting portraits or a bust of “The Founder” in front of the eagle. Flags representing both stores, the Wanamaker Cadets in New York and Philadelphia, and other groups clustered behind the painting along with bouquets of flowers and wreaths laid as offerings to the dead merchant.90 With each year, the displays became more ornate.

Such religious and patriotic festivals and adornments in the Grand Court could easily be dismissed as pandering for sales, and some customers may have taken the plaques this way. Yet Wanamaker made these efforts sincerely, hoping to share a bit of his wisdom with those who came to shop with him. They translated his Protestant Christian ethos into the commercial space in a new way. He hoped that shoppers took home with their merchandise the markers of good character and morality—the virtues of a genteel Protestant Christianity.

Figure 5.6. Every year following his death, Wanamaker’s birthday was celebrated in the store. His portrait was placed in the Grand Court in front of the eagle. Flowers and other offerings from the Wanamaker Cadets and employees were placed next to and at the foot of the portrait. The celebration shown here was in 1930, eight years after his death.

***

In the spring of March 1922, Dennis F. Crolly, “a stranger,” sent a letter to Wanamaker to express gratitude for the store’s interior. The new building was ten years old now and still dazzled. Crolly commented on the “myriad clustered lights” and how they beautifully played off of the “crystal glass and burnished metal and polished wood; and bewildering variety of articles.” Beautifully lit and displayed merchandise caught his eye, and so did the art. Crolly mentioned “the pictures; the sculptures; the tapestries” and asserted that “whoever planned the storescape and set the seal of beauty on it deserved the holy name of artist.” For him, the Wanamaker store was a place of “sheer beauty” that evoked delight. Crolly observed the crowd in the Grand Court, a “moving, busy, happy, smiling, chatting throng,” and noted how the people gathered there “gave it all a soul.” What he saw before him was what he called “the ideal represented in the living reality,” an ideal that “edified the Anglo-Saxon.” He went on to say that he had heard that Wanamaker was “a great merchant.” Now that he had visited the store, his admiration had increased. Crolly ended his letter declaring to Wanamaker, “You are a great man.”91

Wanamaker wanted his store to do more than sell goods. Art and commerce went hand in hand, and his success beyond mere consumerism. He sought to use his store interior to foster a particular Christian vision of community deeply steeped in Protestant middle-class values and a form of Christian taste. Wanamaker wanted to awaken his customers’ souls and invite them to reach a higher morality. To acquire Christian taste was to appreciate beauty, which Wanamaker believed would lift the spirit closer to God, and to embrace the values of trustworthiness, simplicity, control, discipline, and balance, which he thought could be nurtured by one’s physical environment and material practices. In other words, to embrace Christian taste was not only to gain an aesthetic education but also to experience moral uplift. Wanamaker pursued this commitment most intentionally in the Grand Court by creating a space that was both beautiful and awe-inspiring. He shaped it into a sacred space through architecture, rituals, and performances. These Christian and civic expressions created religious sensations cultivated by fusing religious symbols and sentiment with spaces and practices of consumption. His displays contributed to the creation of civic Christian holidays.

Teasing out the values of morality, orderliness, and discipline that Moody’s revival had emphasized, Wanamaker merged them with Bushnell’s Christian nurture and Ruskin’s promotion of beauty as he designed the interior of his building to generate emotions in his shoppers. One of the aspects Wanamaker loved about the type of revivalism the Businessmen’s Revival and Moody were known for was the controlled, disciplined, and balanced stirring of emotions. By designing and creating the interior of the Wanamaker Building, Wanamaker sought to continue what had started on that site over twenty-five years before when Moody and Sankey had captivated thousands on his future sales floor. The new building was its own form of religious excitement, controlled and disciplined through granite and communicated through its interior design. The spacious Grand Court, the enormous organ, the musical performances, the fine art, the holiday displays—all this and more communicated to shoppers a message of morality and hope and possibility. Wanamaker had created a Protestant temple in the middle of his Philadelphia department store empire. He peddled more than just merchandise. He presented to shoppers a cultural education and a place to publicly celebrate the holidays.

Shoppers heartily responded, making Wanamaker’s department store a part of their holiday traditions and cultural excursions.