6. Bardstown

The Kentucky Bourbon Festival, Barton 1792, Heaven Hill Bourbon Heritage Center, Kentucky Bourbon Distillers, Maker's Mark, and Jim Beam

Bardstown calls itself the Bourbon Capital of the World, and with good reason. It is home to the Barton 1792 Distillery; headquarters of Heaven Hill Distilleries, along with its bottling plant and warehouses; Kentucky Bourbon Distillers' Willett Distillery; and the Oscar Getz Museum of Whiskey History. Maker's Mark Distillery is about half an hour south of town, and both the Jim Beam Distillery and the Four Roses warehouses and bottling operation are about a twenty-minute drive northwest. As if that weren't enough to lay claim to the name, Bardstown also hosts the Kentucky Bourbon Festival, an annual six-day celebration of the city's most famous product.

In 1780 brothers David and William Bard used a 1,000-acre land grant from Governor Patrick Henry of Virginia to found Bardstown, which is Kentucky's second-oldest town. In addition to being famous for bourbon, Bardstown is the site of the oldest Catholic cathedral west of the Appalachian Mountains (St. Joseph's Proto-Cathedral happens to be just next door to the Oscar Getz Museum of Whiskey History).

Another claim to fame is the Georgian mansion known as Federal Hill, enshrined at My Old Kentucky Home State Park (501 East Stephen Foster Avenue, 502-348-3502, http://parks.ky.gov/parks/recreation-parks/old-ky-home/default.aspx). Federal Hill was home to the Rowan family and was reportedly visited by the Rowans' Pittsburgh cousin, composer Stephen Foster, in the 1850s. Inspired by the house and the surrounding plantation, Foster penned the song that would become the state's anthem, sung by tens of thousands of Kentucky Derby spectators the first Saturday in May. The mansion and grounds are open for tours given by guides in period costume. Every summer, Stephen Foster: The Musical is performed in the park's amphitheater. In the past, the park grounds served as one of the sites for the Bourbon Festival, and they may do so again. Call or visit the park's website for more information about tours and performances.

The Richardson Romanesque–style Visitors Center was formerly the county courthouse.

Federal Hill at My Old Kentucky Home State Park.

Bardstown itself is a charming place, with more than 300 buildings listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The streets around Courthouse Square are lined with shops, restaurants, and bed-and-breakfasts. And most of the restaurants have an excellent selection of bourbon. Several of the large historic houses along North Third Street constituted what was known as Distillers' Row, since many lived here. Fred Noe, master distiller for Jim Beam, still lives on the street. For more details on Bardstown's non-bourbon-related attractions and festivals, go to http://www.visitbardstown.com/.

The Kentucky Bourbon Festival

The Kentucky Bourbon Festival began in 1992 with a dinner and tastings. Today it has grown into a six-day event with concerts, races, a golf tournament, a cocktail contest, cooking and drink-mixing classes, expert panel discussions, an auction of bourbon memorabilia, a gala black-tie dinner, and more. In 2011 some 50,000 people attended the festival, traveling from thirty-eight states and fourteen countries.

The center of the festival's activities is the Spalding Hall lawn, just outside the entrance to the Oscar Getz Museum of Whiskey History (114 North Fifth Street). Almost all the distilleries set up exhibits on the lawn, and merchants display and sell all kinds of bourbon-related items there, from books to foodstuffs. There are also demonstrations of barrel making, and the lawn is well within hearing range of the outdoor concerts taking place on a nearby stage. Not surprisingly, the Spirit Garden, where visitors can purchase bourbon drinks and beer, is one of the most popular sites. Venues for festival activities are scattered throughout Bardstown and may change from year to year, so be sure to double-check locations.

A Jim Beam barrel-racing team.

The Buffalo Trace barrel-racing team. Buffalo Trace master distiller Harlen Wheatley. Gala guests mingle with Heaven Hill master distiller Parker Beam, and one attendee shows off a Four Roses tattoo. Jim Beam master distiller Fred Noe and a gala attendee compare footwear.

Distillery employees practice throughout the year to compete in the Saturday morning World Championship Bourbon Barrel Relay. Men's, women's, and mixed teams, as well as individuals, participate in the competition, which is based on the skills required to properly store barrels in a warehouse. The teams roll water-filled barrels around a course, and each barrel has to finish bung side up. A combination of the best time and the proper bung orientation wins the competition.

The festival is a good time to meet many of the people involved in the bourbon industry. All the master distillers are on hand for many of the events, and they will certainly be in attendance at Saturday night's Great Kentucky Bourbon Tasting and Gala.

For details about tickets and events, call 800-638-4877. The Bourbon Festival staff will be glad to mail you a brochure. You can also buy tickets online at http://www.kybourbonfestival.com/.

Where to Eat and Drink

Most of the best food in Bardstown can be found in restaurants serving traditional southern cuisine. Pricing is indicated as follows: $—inexpensive, with most entrees priced at $15 or less; $$—moderate, at $16 to $25; and $$$—expensive, at $26 or higher. Reservations are recommended, especially during the Bourbon Festival.

BJ's Steakhouse—201 Camptown Road, 502-348-5070, http://www.bjssteakhouse.com. American, steaks, $$.

Circa Restaurant—103 East Stephen Foster Avenue, 502-348-5409, http://www.restaurant-circa.com/. Fine dining, $$–$$$.

Kentucky Bourbon House—107 East Stephen Foster Avenue, 502-507-8338, http://www.kentuckybourbonhouse.com/. Southern, $$. Bourbon tastings daily from 4 to 10 p.m.

Kurtz Restaurant—418 East Stephen Foster Avenue, 502-348-8964, http://www.bardstownparkview.com/dining.htm. Southern, $$.

My Old Kentucky Dinner Train—602 North Third Street, 502-348-7300 or 866-801-3463, http://www.kydinnertrain.com. American, $$.

Kentucky Bourbon Festival auction.

The historic Old Talbott Tavern has both a restaurant and lodging.

Old Talbott Tavern—107 West Stephen Foster Avenue, 502-348-3494 or 800-482-8376, http://www.talbotts.com. American, plus a good bourbon bar, $–$$.

The Rickhouse Restaurant & Lounge—Xavier Drive, 502-348-2832, http://www.therickhouse-bardstown.com/. American, steaks, $$–$$$.

Rosemark Haven Restaurant & Wine Bar—714 North Third Street, 502-348-8218, http://www.rosemarkhaven.com/dinners.html. American, $$–$$$.

Where to Stay

Hotel space is very limited during the Bourbon Festival. Even though Bardstown has many bed-and-breakfasts, most have only a few rooms. Keep in mind that you could stay in Louisville, which isn't far from Bardstown. Rates listed are the establishment's lowest. Special features and suites cost more, and daily rates can vary, so you will probably be quoted a higher rate, depending on when you want to stay.

Bardstown Parkview Motel—418 East Stephen Foster Avenue, 502-348-5983 or 800-732-2384, http://www.bardstownparkview.com/. $70.

Beautiful Dreamer Bed & Breakfast—440 East Stephen Foster Avenue, 502-348-4004 or 800-811-8312, http://bdreamerbb.com/. $149.

Best Western General Nelson Inn—411 West Stephen Foster Avenue, 502-348-3977 or 800-225-3977, http://www.generalnelson.com. $68. This is the venue for several Bourbon Festival events.

Hill House, in the town of Loretto, is near Maker's Mark.

Hill House—110 Holy Cross Road, Loretto, 877-280-2300, http://www.thehillhouseky.com/. $95.

Jailer's Inn—111 West Stephen Foster Avenue, 502-348-5551 or 800-948-555, http://www.jailersinn.com/. $100.

Old Kentucky Home Stables and Bed & Breakfast—115 Samuels Road, Cox's Creek, 502-349-0408, http://www.farmstayus.com/farm/Kentucky/Old_Kentucky_Home_Stables. $115.

Old Talbott Tavern—107 West Stephen Foster Avenue, 502-348-3494 or 800-482-8376, http://www.talbotts.com. $65.

Rosemark Haven–714 North Third Street, 502-348-8218, http://www.rosemarkhaven.com/. $109.

Warehouse H at Barton 1792 Distillery.

Barton 1792 Distillery

300 Barton Road

Bardstown, KY 40004

502-331-4879 or 866-239-4690

Hours: Monday–Friday, 9 a.m.–3 p.m.; Saturday, 10 a.m.–2 p.m. Tours are given year-round and start on the hour. Closed Sundays and major holidays. Call for information about special tours offered at other times.

Bourbons: 1792 Ridgemont Reserve, Colonel Lee, Kentucky Gentleman, Kentucky Tavern, Ten High, Tom Moore, Very Old Barton (80, 86, 90, and 100 proof)

Chief Executive: Mark Brown

Master Distiller: Ken Pierce, but his official title is director of distillation and quality assurance

Owner/Parent Company: Sazerac Company

Tours: The free tours take about two hours and end with a tasting of 1792 Ridgemont Reserve. Be aware that parts of the tour involve steps, including 33 from the floor (often wet) of the still house to the still safe and you should not wear open-toed shoes.

What's Special:

- When the mash is cooking, it gives downtown Bardstown a distinctly aromatic atmosphere.

- The 192-acre property has twenty-eight aging warehouses.

- Water from an on-site spring is still used to make the bourbon here.

- One feature of the site is a fifteen-foot-tall, 8,000-gallon bourbon barrel that was a local high school's shop project (only in Kentucky).

- Many other brands of liquor owned by Sazerac are bottled on the premises.

- This was the first distillery to offer public tours, starting in 1957.

- Bardstown's Oscar Getz Museum of Whiskey History was originally housed here.

- The distillery's column still is six feet in diameter and fifty-five feet high.

History

Having a reliable source of limestone water is crucial for bourbon making, which is why so many Kentucky distilleries are located on rivers and streams. The Barton 1792 Distillery makes use of a third option: it has its own “never fail” spring.

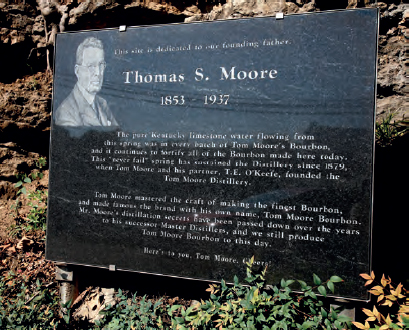

The first distillery on the Morton's Spring site was owned by Willett & Franke, one of whose proprietors was John D. Willett (yes, there is still a Willett bourbon made today; see page 166). Willett's daughters married Thomas S. Moore and Benjamin F. Mattingly, and in 1876 their father-in-law transferred the distillery to the pair. Mattingly & Moore Distillery released Tom Moore bourbon in 1879, but the business was sold to investors in 1881. Mattingly left the company, but Moore stayed until he bought the property next to the Morton's Spring site and built his own distillery. Apparently, the investors who had purchased Mattingly & Moore were not very good businessmen, and they went bankrupt in 1916. Moore bought the property and merged it with his own operation, resulting in today's 192-acre site. But four years later came Prohibition.

The Moore family managed to keep the property and reopened the distillery after repeal but then sold it to Harry Teur, who renamed it Barton and modernized the facility. No one seems to know how he came up with the name, but according to one story, he picked it out of a hat. Barton was subsequently sold to Oscar Getz and Lester Abelson (coincidentally, another pair of brothers-in-law). After Barton filled its one millionth barrel in 1957, Getz, who was keenly interested in bourbon history, opened a museum on the grounds and invited the public to take tours, beginning an industry practice that is common today. Eventually, the collection was moved to Spalding Hall and became the Oscar Getz Museum of Whiskey History.

A plaque dedicated to Thomas Moore.

Barton was a major player in the consolidation of bourbon brands that occurred in the 1970s and 1980s. Barton itself was bought in 1993 by the company that would become Constellation Brands. In a nod to history, Constellation renamed the distillery Tom Moore in 2008, but it turned out to be a very short-lived moniker. Sazerac (also the parent company of Buffalo Trace Distillery) acquired Tom Moore in 2009 and changed the name to Barton 1792 to include a reference to the company's premium bourbon—1792 Ridgemont Reserve, which had been released in 2003 (1792 is the year Kentucky became a state).

The Tour

The facility at Barton 1792 has an authentically industrial feel. Most of the larger distilling buildings date from the 1940s and were built for function, not aesthetics. Trucks rumble in and out of the grounds past the Visitors Center, and glass and machinery rattle loudly in the bottling plant. It's like traveling back in time to mid-twentieth-century America, when manufacturing drove the economy.

The combination gift shop and tasting room, where tours begin, is located in the remodeled building that originally housed Oscar Getz's collection of bourbon memorabilia. Your tour guide will cover the history and details of bourbon, including a description of the aging process, on a visit to one of the warehouses. A full fifty-three-gallon barrel weighs about 520 pounds, but the whiskey begins to evaporate almost immediately. The first year, about 10 percent is lost, with another 3 or 4 percent lost each year thereafter. This is why bourbons aged more than a decade start to get pricey: there are simply fewer bottles per barrel.

Bourbon warehouses are constructed using an interlocking system of beams, resembling giant Tinker Toys, to allow air circulation. If one side of the warehouse becomes too heavy, with too many new, full barrels in one place and too many older and evaporating barrels in another, the whole structure could go out of balance and collapse. So you'll notice plumb lines strategically placed in Warehouse H; these are used to measure any structural shifts and ensure that the 10 million pounds of bourbon stored there stays put.

The second stop on the tour is the still house for a look at Barton's impressive distilling apparatus. The five-story-high column still is six and a half feet wide and can distill more than 100 gallons an hour. (At this point, the guide might mention that as of 2011, the human population of Kentucky was 4.4 million, whereas the number of aging bourbon barrels in warehouses throughout the state was 4.7 million.) After gazing up at the still, you'll climb three flights of metal stairs to the room housing the gleaming copper spirit safe, where there will be plenty of time to have your photo snapped.

The Barton 1792 women's barrel-racing team on the distillery's practice course.

Distiller Ken Pierce nosing new whiskey from the spirit safe.

Barton's bottling operation is impressively efficient. There are six bottling lines, and each can be changed in about twelve minutes to accommodate different products. In addition to its own bourbons, Barton does a lot of contract bottling for other distillers, including California brandy distillers. Parent company Sazerac owns several brands of vodkas and gins, which you may also see being bottled. The plant is noisy—a cross between a roller coaster and a light rail system, accented with the high-pitched click of glass on metal. (It's quieter when the bottles on the line are plastic.)

Adding stoppers to bottles of 1792 Ridgemont Reserve.

Like all good distillery tours, this one ends with a tasting. Little snifters of 1792 Ridgemont Reserve are a nice touch. Trays of bourbon balls are offered too, and no one minds if you have more than one.

The Bourbon

When current director of distillation Ken Pierce joined Barton's in 1994, he was given the task of creating a premium small-batch bourbon. The result, released in 2003, was 1792 Ridgemont Reserve (the bourbon you will sample at the end of the tour). The name honors the year of Kentucky's statehood and the name of the still in which the bourbon is produced. (Apparently, some stills, like some automobiles, are given names.)

Barton does not release the exact proportions used in its mash bills, but it has disclosed that 1792 Ridgemont Reserve has a higher rye content than most bourbons. This is evident from the first whiff of the whiskey. The nose is all about spice. Joining the expected vanilla and caramel are notes of coffee and chocolate. If there is any fruit at all, it is apple, but you really have to concentrate to taste it. The bourbon is bottled at 93.7 proof, so the longer it sits in the glass, the more layers of flavor are revealed. The finish is long and spicy.

Visitors pose with Barton 1792's fifteen-foot-tall bourbon barrel.

The signature brand of the distillery is the six-year-old Very Old Barton. When it was first made in the 1940s, it was aged two years longer than most other bourbons—hence the name. Long the best-selling bourbon in Kentucky, it is bottled at 80, 86, 90, and 100 proof. The distillery gift shop sells the 86-proof Very Old Barton in addition to 1792 Ridgemont Reserve. The 100-proof version is bottled in bond and well worth seeking out at a local liquor store.

Travel Advice

Barton 1792 is less than a five-minute drive from the Bardstown Courthouse Square. Go west on Stephen Foster Avenue for a quarter mile and turn left onto Barton Road. The distillery is half a mile farther on your right.

Nearby Attractions

All the attractions of Bardstown are within a few minutes of one another, but you will certainly want to visit the Oscar Getz Museum of Whiskey History (114 North Fifth Street, 502-348-2999, http://www.whiskeymuseum.com). Originally housed at Barton, it is now located at Spalding Hill, just a short drive across Stephen Foster Avenue from the distillery, tucked behind St. Joseph's Proto-Cathedral. The collection of bourbon-related artifacts spans more than two centuries and includes antique distilling equipment, rare bottles and other containers, glassware, advertisements, and prescriptions for bourbon written during Prohibition. As a bourbon lover, you'll probably want to avert your eyes from Carrie Nation's hatchet, which is displayed in a little case next to a photograph of the temperance zealot.

Heaven Hill Bourbon Heritage Center

1311 Gilkey Run Road

Bardstown, KY 40004

502-337-1000

http://www.bourbonheritagecenter.com

Hours: Monday–Saturday, 10 a.m.–5 p.m.; Sunday, noon–4 p.m. Tours are given year-round. Closed major holidays.

Bourbons: Evan Williams, Evan Williams Single Barrel Vintage, Elijah Craig Single Barrel 12-Year-Old, Elijah Craig Single Barrel 18-Year-Old, Larceny, Parker's Heritage Collection (very limited release), Heaven Hill, Henry McKenna, Henry McKenna Single Barrel, Fighting Cock, Old Fitzgerald, Old Fitzgerald's 1849, Old Fitzgerald Very Special 12-Year-Old, Cabin Still, J. W. Dant, Echo Spring, Mattingly & Moore, J. T. S. Brown, T. W. Samuels, Kentucky Deluxe, Kentucky Supreme

The 1792 Ridgemont Reserve bottling line.

Heaven Hill Bourbon Heritage Center.

Ryes: Rittenhouse Straight Rye, Pikesville Straight Rye

Other Liquors: Bernheim Original Kentucky Straight Wheat Whiskey, Evan Williams Honey Reserve (liqueur made with bourbon), Corn and Rye New Make Whiskeys, Mellow Corn Kentucky Straight Corn Whiskey, and a large catalog of vodkas (plain and flavored), rums, tequilas, gins, and other spirits

Chief Executive: Max L. Shapira

Master Distillers: Parker Beam and Craig Beam

Owner/Parent Company: Heaven Hill Distilleries Inc.

Tours: The Mini Tour, which lasts about half an hour, is free and is offered many times throughout the day. The Deluxe Tour, also free and offered throughout the day, lasts an hour and a half. The Behind the Scenes Tour is three hours and costs $25. A half-hour Trolley Tour of Bardstown is $5. Reservations for the last two tours can be made online or by calling the Bourbon Heritage Center.

What's Special:

- Heaven Hill opened in 1935—after the repeal of Prohibition.

- It is the largest family-owned and -operated independent (not publicly traded) producer and marketer of distilled spirits in the United States.

- Heaven Hill owns the second-largest amount of aging bourbon in the world, with an inventory of more than 900,000 barrels.

- After a 1996 fire destroyed its Bardstown distillery, Heaven Hill bought the Bernheim Distillery in Louisville in 1999, where all the company's bourbon is made today.

- The Bourbon Heritage Center, which opened in 2004, has won numerous awards, including Whisky Magazine's Icon and Visitor Attraction of the Year.

- You can join the distillery's Bardstown Whiskey Society (www.bardstownwhiskeysociety.com) and receive notice of special events and its monthly e-newsletter the Barrelhouse Chronicle.

- Heaven Hill plans to open an Evan Williams microdistillery and a history exhibit on Louisville's Whiskey Row in the fall of 2013, just a couple of blocks south of the probable location of Evan Williams's eighteenth-century distillery.

History

In addition to bringing relief to bourbon drinkers, the end of Prohibition on December 5, 1933, created business opportunities for entrepreneurs who had managed to retain some capital even in the midst of the Great Depression. Before 1920 there had been more than 200 operating distilleries in Kentucky. Only about one-third of them reopened in 1934 to make bourbon for thirsty Americans.

With the number of distilleries seriously diminished, brothers David, Ed, Gary, George, and Mose Shapira recognized that starting a new distillery could be a profitable venture. The Shapiras bought property south of Bardstown where one William Heavenhill had had farm in the nineteenth century. They split the farmer's name in two and christened their new distillery Heaven Hill.

Even today, one obstacle to opening a new distillery is how long you have to wait for a salable product. Although it doesn't take long to make whiskey, you can't sell it until it has aged for several years. The Shapiras got their brand into the marketplace quickly by selling their new whiskey when it was just two years old, the age at which it could legally be called “straight bourbon.” Bourbon Falls Kentucky Straight Bourbon made enough money to keep the business going until the brothers could release bourbon that had been aged longer. That bourbon was four-year-old Heaven Hill.

In 1946 the Shapiras recognized that although they knew how to build a business, they really didn't know much about bourbon, other than what they were learning on the job. (There's a big difference between owning a baseball team and being able to hit home runs.) So they hired a member of the Beam family, distiller Henry Homel. Beams have been at the helm of Heaven Hill's distilling ever since. In 1948 Homel's cousin, Earl Beam, left the Jim Beam Distillery to become Heaven Hill's master distiller. Earl's son, Parker Beam, started working at Heaven Hill in 1960 and eventually became master distiller himself, a position he still holds, although most of the daily distillery operation is now in the hands of his son, Craig Beam. Meanwhile, the Shapira family is still in charge of the business, with the children and grandchildren of the original brothers continuing to expand the company's presence both in America and abroad.

The filling room, part of the Behind the Scenes Tour.

Visitors read about the history of Heaven Hill in the Bourbon Heritage Center.

Custom-designed machinery in the bottling plant.

This growth is all the more impressive in light of the catastrophe that occurred at Heaven Hill on the stormy afternoon of November 7, 1996. At around two o'clock, a fire started in one of the warehouses (it might have been sparked by lightning, but no cause has ever been determined). Warehouse interiors are made of wood, designed to allow maximum air circulation, and they are filled with alcohol-soaked wooden barrels that act like resin-soaked kindling in a woodstove. It is impossible to stop a bourbon-fueled fire once it has started. The best possible outcome is containment—preventing the fire from leaping to other buildings. But in this case, that too proved to be almost impossible.

The storm front was accompanied by winds of forty to fifty miles per hour, which caused the fire to spread rapidly. Soon half a dozen other warehouses had caught fire. Flames shot hundreds of feet in the air, and the light and heat of the fire were accompanied by the percussive cracks of thousands of exploding bourbon barrels. A dozen engine companies, including two from as far away as Louisville, responded to the scene, but all the firefighters could do was pump water onto the buildings that had not yet caught. Worst of all, by four o'clock the distillery itself, located downhill from the warehouses, was engulfed. Footage shot from news helicopters showed streams of flaming whiskey flowing from the burning warehouses to the distillery buildings.

Remarkably, no one was seriously injured, but almost 8 million gallons of bourbon were destroyed. (This was estimated to represent 2 percent of the world's bourbon supply at the time.) The good news was that Heaven Hill's proprietary yeast strain dating from 1935 had been rescued.

Barton, Jim Beam, and Brown-Forman allowed Heaven Hill to distill in their plants until 1999, when the company purchased the Bernheim Distillery in Louisville from Diageo. Heaven Hill continues to make bourbon there today. It also enlarged its bottling operation in Bardstown and rebuilt its warehouses. And in 2004 the Bourbon Heritage Center opened to visitors.

The Tours

Even though Heaven Hill no longer has a working distillery in Bardstown, visitors to the Bourbon Heritage Center can still get an excellent sense of what is involved in the bourbon-making process. The center's design was inspired by traditional warehouse architecture, and it is chock full of informative, interactive exhibits on the history of bourbon and its place in Kentucky history. Each of the Heritage Center's site-based tours begins in the Evan Williams Theater, where a short film, Portrait of Heaven Hill, contains narrative about the suitability of Kentucky's climate and natural resources for bourbon making. Fittingly (given that two of Heaven Hill's signature bourbons are named after them), bourbon pioneers Elijah Craig and Evan Williams make onscreen appearances. Each of the tours ends with a tasting in the Barrel Bar inside the Parker Beam Tasting Barrel, where bourbons are served in Glencairn glasses placed on built-in bar-top lights to show off the whiskies' colors.

After a tasting, you can take your time exploring the gift shop, which surrounds the Tasting Barrel. Several interactive exhibits about bourbon flavors are interspersed with the displays of merchandise, which includes a large array of books, signature glassware, clothing, and gourmet food items made with Heaven Hill products. A small number of bottles of Parker Beam's very limited edition Heritage Collection are also available in the gift shop. A different bottling is released each year.

Mini Tour

If you are planning to visit more than one distillery in a day or happen to be in Bardstown for the Bourbon Festival, the thirty-minute Mini Tour is a fine introduction to Heaven Hill. After the orientation film, your guide will take you around the exhibits in the Bourbon Heritage Center, which is filled with historic photos, distilling paraphernalia, and time lines. Although these exhibits are very detailed and self-explanatory, the guide will field questions and, of course, lead you in the tasting of Evan Williams Single Barrel Vintage in the Barrel Bar. Visitors are given vials of scents to sniff in order to warm up their nosing “muscles.” Small pitchers of water are also provided so you can experiment with how a splash of water affects the whiskey's flavors. There is no charge for the tour.

Deluxe Tour

The Deluxe Tour is also free. From the theater, the guide leads visitors outside to Warehouse Y for a detailed explanation of the aging process, with an emphasis on the influence of the barrel char, the barrel's position in the warehouse, and the number of years to maturity. Then he or she will take you back to the Barrel Bar to taste two bourbons—Evan Williams Single Barrel Vintage and Elijah Craig 12-Year-Old—allowing you to compare and contrast.

A post-tour tasting in the Parker Beam Tasting Barrel.

Behind the Scenes Tour

Heaven Hill makes a lot of bourbon, but it accounts for only about a quarter of the company's sales. It also owns dozens of brands of spirits and imports and distributes many more. Most of this liquor winds up at the massive production plant next door to the Bourbon Heritage Center, in which about a million cases are bottled each year. This is the focus of the Behind the Scenes Tour.

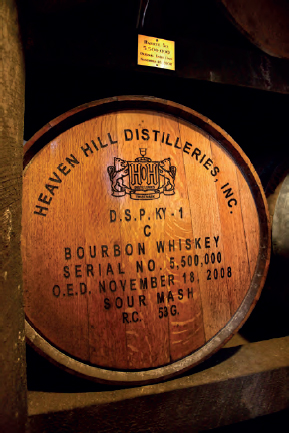

The Shapiras have invested in custom-built, state-of-the-art technology to handle the enormous volume of product passing through the facility. After the same orientation film shown for the other tours, a van will whisk you to the barrel-filling building, where a series of conveyors rolls the barrels into position. This saves the backs of the staff; all they have to do is run the computerized filling machinery. A display of barrel heads on the wall by the entrance marks the important Heaven Hill barrel milestones. The first barrel was filled with whiskey in 1935, and it took twenty-six years to reach the millionth barrel. It's a measure of Heaven Hill's (and the bourbon industry's) growth that the gap between the five millionth and six millionth barrels (the latter filled in 2010) was only four years.

The gleaming bottling operation is mesmerizing, like an over-twenty-one version of Willie Wonka's Chocolate Factory. Thousands of bottles of various shapes and sizes zip along steel channels, where they are filled, labeled, sealed, boxed, and stacked. Helical conveyor towers carrying cardboard cases look like escaped carnival rides. There's even a machine that squirts glue on the box flaps before closing and sealing them and a giant plastic shrink-wrapping machine to wrap flats stacked high with cardboard cases.

The tour includes a warehouse visit before concluding with a tasting of any two of three bourbons—Evan Williams Single Barrel Vintage, Elijah Craig 12-Year-Old, and Elijah Craig 18-Year-Old. The Behind the Scenes Tour is limited to six participants at a time, lasts about three hours, and costs $25 per person. Reservations must be made in advance.

Trolley Tour

The half-hour Trolley Tour leaves from the Bourbon Heritage Center and offers a good introduction to the history and sights of Bardstown. The route may vary, depending on the time of day and the interests of the passengers, but among the popular sites are My Old Kentucky Home State Park, Old Bardstown Village, Old Talbott Tavern, My Old Kentucky Dinner Train, and the Wickland mansion. The tour costs $5 per person, and reservations are required.

The Bourbon

Heaven Hill produces more than twenty bourbons and offers three of its best at the tour-end tastings. A bottling of Evan Williams Single Barrel Vintage has been released each year since 1995. Craig and Parker Beam select individual barrels that have the profile they want, and the bourbon is bottled from each barrel without mingling. This means that each vintage is a little different, even though the proof is always 86.6 and the age is about nine years. (The statement “Put in the Oak,” followed by the year, appears on each bottle.) The little lights on the Barrel Bar bring out the bourbon's bright gold sparkle. The nose features caramel and oak. Wood persists on the palate, dominating the orange notes; spice and wood dominate the finish.

At 94 proof, the Elijah Craig 12-Year-Old immediately gets your attention with a big vanilla nose. The fruit on the palate takes second place to spice, including cinnamon and nutmeg, and the coppery-colored bourbon finishes with more sweetness than it begins with. It's a small-batch bourbon that has been mingled from several barrels.

Barrel number 5,500,000.

Given its age, it is not surprising that the Elijah Craig 18-Year-Old has a darker amber color than the other two bourbons. Both the nose and the palate are a lovely balance of vanilla and nutty caramel. This single-barrel bourbon has a lightly spicy finish that lingers luxuriously.

Travel Advice

From Bardstown's Courthouse Square, take US 150 (East Stephen Foster Avenue) for eight-tenths of a mile past My Old Kentucky Home State Park and turn right onto Parkway Drive (KY 49). After about a mile, you will come to a fork in the road, where you'll see the Heaven Hill warehouses. Bear to the right, and the Bourbon Heritage Center is on your right. The drive from the center of Bardstown takes about five minutes.

Kentucky Bourbon Distillers and Willett Distillery

1869 Loretto Road

Bardstown, KY 40004

502-348-0081

http://www.kentuckybourbonwhiskey.com

Hours: Tours are given year-round, Monday–Saturday, at 10 a.m. and 2 p.m. The tasting room is open Monday–Friday, 9 a.m.– 5 p.m., and Saturday, 10 a.m.– 3 p.m. Closed major holidays.

Bourbons: Willett Pot Still Reserve, Noah's Mill, Rowan's Creek, Pure Kentucky XO, Kentucky Vintage, Johnny Drum Kentucky Straight Bourbon Whiskey, Johnny Drum Private Stock, Old Bardstown Black Label, Old Bardstown Estate Bottled, Old Bardstown Gold Label, limited-edition 17-Year-Old Vintage Bourbon

Chief Executive: Even Kulsveen

Master Distiller: Drew Kulsveen

Owner/Parent Company: Kentucky Bourbon Distillers Ltd.

Tours: Tour of the working distillery includes the still house, a warehouse, and the gift shop/tasting room. Tours include a taste of any two Kentucky Bourbon Distillers' bourbons, except for the very expensive, limited-production Willett Pot Still Reserve.

What's Special:

- This is a small, independent, family-owned distillery.

A bull made out of barrels (the signs read, “No bull, just bourbon”).

Kentucky Bourbon Distillers and Willett Distillery.

- The distillery has both a pot still and a column still, which can be used independently or in combination.

- Until 2012, the bourbons from Kentucky Bourbon Distillers (KBD) were bottled from existing stocks of aging barrels bought from distilleries that had gone out of business, such as Stitzel-Weller, or bought from working distilleries and aged at the KBD site.

- The distillery, including its eight bonded warehouses, is situated on a hill overlooking Heaven Hill.

- Development of the distillery property is ongoing, including the construction of two buildings to accommodate overnight guests. The bed-and-breakfast is scheduled to open in 2014.

History

Many bourbon travelers combine a morning visit to the Heaven Hill Bourbon Heritage Center with an afternoon jaunt to Maker's Mark, which is about half an hour away via Loretto Road. But just a minute's drive from the Heritage Center, a few hundred yards past the ruins of Heaven Hill's original distillery, you'll find the very antithesis of a million-case-a-year operation.

The Willett Distilling Company was founded by several members of one family in 1935. Lambert Willett bought the property, and his sons A. L. “Thompson” Willett and Johnny Willett built the distillery. Willett's best-known brand was Old Bardstown, and it remained small by the standards of its neighbor. By the 1970s, the company was producing about fifty barrels a day and had eight warehouses. With the downturn in the bourbon market, the plant was converted to making fuel alcohol. Unfortunately, the end of the 1970s oil crisis shrank the demand for industrial ethanol too, and Willett's closed in the early 1980s. But this is not another sad story of a closed and abandoned distillery.

Thompson Willett's daughter Martha married a Norwegian named Even Kulsveen, who purchased the property in 1984 and founded Kentucky Bourbon Distillers Ltd. Kulsveen, along with his son Drew, daughter Britt, and son-in-law Hunter Chavanne, have run KBD as a successful bottler of bourbons made under contract by other (undisclosed) distillers. Willett Pot Still Reserve was introduced in 2008; it's an award-winning single-barrel bourbon aged eight to ten years and bottled at 47 proof. But that's still not the end of the story.

For three decades, Even Kulsveen and his family have slowly been restoring and refurbishing the Willett Distillery. New, custom-made distilling equipment was commissioned from Vendome Copper & Brass Works, which complements some of the equipment that remains from the distillery's founding in 1935. And as of January 2012, bourbon is once again being produced at the Willett Distilling Company. A 103-proof bourbon was put into barrels on Thompson Willett's 103rd birthday, signaling the rebirth of Willett Distillery.

The Tour

Unless you are part of a group that has made special arrangements, tours at the big distilleries are usually led by staff guides, not by the master distiller. But Willett is a small operation, and chances are good (at least until production increases considerably) that your tour guide will be master distiller Drew Kulsveen. His pride in his family's distilling history and the pleasure he takes in explaining the features of the current plant make this a true insiders' tour.

Visitors meet in the gift shop/tasting room. It's a short walk to the still house, which has been restored and enhanced with carefully selected materials ranging from limestone and brick to custom-made iron-work. You'll climb a wide flight of stairs to the floor containing the tops of the fermentation tanks. This overlooks the room that houses Willett's new copper pot still. In summer, the fermentation room is cooled with a series of large, handsome, belt-driven ceiling fans powered by a small enclosed motor, which prevents dangerous sparks.

Master distiller Drew Kulsveen.

Willett's copper pot still.

Red door at Willett Distillery.

Sour Mash Bourbon Whiskey barrel.

When the tour returns to the main floor, Kulsveen will fill a glass with new whiskey from the spirit safe and pass it around for visitors to nose. The tour then moves to the barrel-filling house, before going to one of the warehouses. The hilltop elevation (more than 640 feet above sea level, higher than any other warehouse in Nelson County) allows a striking amount of air to circulate between the barrels. You seldom encounter this much breeze in a bourbon warehouse.

The tour ends in the gift shop and tasting room, housed in the building that originally served as the distillery offices.

The Bourbons

Several KBD brands are offered for tasting, but in accordance with state law, each visitor is limited to two small tastes, so you'll have to make some choices. Here's a rundown of a few of the KBD brands offered:

- Johnny Drum Private Stock (101 proof)—caramel nose and taste dominated by oak and showing some hints of ginger

- Kentucky Vintage (90 proof)—light caramel character supplemented by notes of tobacco and leather

- Noah's Mill (114.3 proof)—oaky and spicy; tame its heat with a splash of water

- Old Bardstown Gold Label (80 proof)—dominated by corn and vanilla, with more fruit than many KBD bourbons

- Pure Kentucky XO (107 proof)— complex fruit, which can be better appreciated with the addition of a little water

- Rowan's Creek (101 proof)—vanilla, dark fruits, and more than a hint of nuttiness

Maker's Mark

3350 Burks Spring Road

Loretto, KY 40037

270-865-2881

Hours: Monday–Saturday, 10 a.m.–4:30 p.m.; Sunday, 1–4:30 p.m. Closed major holidays and Sundays in January and February.

Bourbons: Maker's Mark, Maker's 46

Chief Executive: Rob Samuels

Master Distiller: Greg Davis

Owner/Parent Company: Beam Inc.

Maker's Mark.

Tour: The tour-end tasting includes bourbon balls and samples of both whiskies.

What's Special:

- Maker's Mark was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1980.

- You can dip your own bottle of bourbon in the signature red wax.

- If you join Maker's Mark Ambassadors, your name will be put on a barrel in the warehouse.

- Nighttime tours with holiday lights and music are given in December.

- The site is also an arboretum, and many trees have identification signs.

History

With its distinctive red wax–covered bottle neck, Maker's Mark is instantly recognizable at any restaurant bar or on any store shelf. The look is a triumph of branding that dates from the middle of the twentieth century, even though the Samuels family has been making bourbon for eight generations, ever since Robert Samuels settled in Kentucky in the 1780s.

In 1840 Robert Samuels's grandson, T. W., build the family's first commercial distillery near Samuels Depot in Nelson County. (Before then, they had made whiskey mainly for consumption by the family and select friends.) Over the next three generations, until Prohibition closed the distillery in 1919, T. W. Samuels bourbon was made and sold. In 1933, at the end of Prohibition, T. W. Samuels reopened, but the distillery was sold in 1943. As it turned out, the family couldn't stay out of the whiskey business, and that's when Maker's Mark was born.

In 1952 Bill Samuels Sr. started experimenting with whiskey recipes by baking bread with different proportions of grains. T. W. Samuels bourbon had been made with corn, rye, and malted barley, but Samuels was looking for something a little different. He consulted with Julian “Pappy” Van Winkle of the Stitzel-Weller Distillery in Louisville, who suggested using wheat in place of rye, as the Van Winkle bourbons do. Samuels took this advice, and his experiments evolved into the mash bill used by Maker's Mark today—70 percent corn, 14 percent red winter wheat, and 16 percent malted barley. But he needed a distillery.

In 1953 Samuels bought the 200-acre Star Hill Farm in Marion County, near Loretto. Bourbon had been distilled on the site since 1805, and it contained a small distillery and several historic buildings, all in need of repair. Samuels not only repaired the buildings but also restored them to their period charm, painting the wooden buildings black with bright red trim and planting native Kentucky trees on the grounds. The restoration was done with such meticulous attention to detail that Maker's Mark Distillery was later designated a National Historic Landmark, the first distillery in the United States given that distinction.

So why is it called Maker's Mark? Credit for the name, and for much of what gives the bourbon its identity, goes to Samuels's wife, Marge, who was a collector of pewter and of antique cognac bottles. Pewter pieces are stamped with the distinctive marks of their makers, so Mrs. Samuels suggested that this distinctive, handmade bourbon should also bear its maker's mark. She got the idea for the red wax from a similar wax on cognac bottles. The circle on the wax seal and the paper label features a star (for Star Hill Farm), the letter S for Samuels, and roman numeral IV for the fourth generation of commercial distillers in the family. Every bottle is hand-dipped in red wax, and every label is hand-cut and pasted on each bottle.

In deference to his Scotch-Irish heritage, Samuels spelled whisky in the traditional rather than the American way on his label. Samuels prided himself on his handmade “small-batch” bourbon, which was sold almost exclusively in Kentucky for twenty years, from the time it was introduced to the market in 1959. That all changed in 1980.

By the 1970s, Bill Samuels Jr. was working for his father at the distillery. In 1980 the Wall Street Journal ran a front-page article about the picturesque distillery situated in a beautiful Kentucky valley. Maker's Mark suddenly became an international brand, and demand and sales soared. Samuels Jr. succeeded his father as company president in 1982. Displaying much of the same marketing savvy as his mother, he wrote copy for many of the first distinctive magazine and billboard ads for Maker's Mark. He was perfectly happy to don colorful costumes and appear in many of the ads himself, adding to Maker's reputation as a unique bourbon in a crowded field. The bourbon was so popular that capacity for distillation was doubled in 2002 by replicating the nineteenth-century distilling equipment.

In 2010 Bill Jr.'s son, Rob Samuels, was named chief operating officer of Maker's Mark and general manager of the distillery, now owned by Beam Inc. But even in “retirement,” the colorful Bill Samuels Jr., now chairman emeritus, continues to be the public face of Maker's Mark.

The Tour

Today, visitors to Maker's Mark can watch the bottling process and even dip a bottle themselves. If you happen to visit the distillery during the winter holiday season, you'll find that the employees working on the bottling line appear to have been borrowed from a certain cookie maker that claims its products are made by elves in trees.

Elf togs notwithstanding, any season is a fine time to visit Maker's Mark. With its idyllic setting, charming historic buildings, and hospitable tour guides, the distillery is appealing not only to bourbon lovers but also to anyone interested in learning about Kentucky history and spending a few quiet hours in the country. Spring is spectacular, when many of the distillery's flowering trees are in bloom and make a striking contrast against the black-painted buildings.

Tours begin in the red frame distiller's house, which at one time was the Samuels family home. Bill Samuels Sr.'s office is preserved and lined with photo portraits of family members that “tell” their stories. (There's a touch of Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry at work here.)

As you leave the distiller's house on the way to the still house, you'll see the firehouse, complete with a bright red antique fire engine—a reminder that fire is the number-one safety concern at every distillery. After you cross the road, you'll climb a short flight of limestone steps to enter the still house. Your guide will show off samples of the corn, wheat, and barley used to make the whiskey and explain the distilling process as the tour progresses from the cypress fermenting tanks to the gleaming copper column stills and doublers.

The bottling house is the next stop, and then into Warehouse D, where you'll learn that Maker's Mark is the only distillery that undertakes the laborious task of rotating its barrels through various levels of the warehouse to achieve a uniform aging flavor. You may also notice metal plates with names etched on them affixed to some of the barrels. These are the names of Maker's Mark Ambassadors—essentially, the bourbon's “fan club”—and these nameplates are one of the perks of membership. (For full details of the program, go to the Maker's Mark website.)

Factory “elves” dip holiday bottles of bourbon in wax.

Spirit safes.

Bill Samuels Jr.

From the warehouse, your guide will lead you through a door into the very contemporary interior of the gift shop and tasting room. Provided you are at least twenty-one years old, you'll get to sample Maker's Mark, Maker's 46, and a Maker's Mark bourbon ball chocolate candy. You'll also have plenty of time to stock up on all the red-and-black signature Maker's Mark “swag,” from barware and bourbon to clothing and golf gear.

Weather permitting, spend some time strolling the grounds, which can be as relaxing as sipping some Maker's Mark. The small Toll House Café, near the distillery entrance, serves sandwiches, salads, and desserts every day from 11:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. Group reservations can be made by calling 270-865-4982.

The Bourbon

The signature Maker's Mark bourbon in the square bottle with the red wax top is distilled at 120 proof, goes into the barrel at 110 proof (instead of the usual 125 proof), and is bottled at 90 proof. The mash bill is the same as it was back in the 1950s: 70 percent corn, 14 percent red winter wheat, and 16 percent malted barley. The yeast is cultured on-site and is a strain that has been in the Samuels family for five generations. Maker's Mark has a bright amber hue, and the high proportion of corn gives it a very sweet nose from which vanilla, caramel, and notes of orange emerge. It is medium bodied and smooth on the palate and has a soft, clean finish.

Unlike most other distilleries, which produce more than one brand of bourbon, Maker's Mark made only its original bourbon for many years. However, it created variation by issuing commemorative versions of its square, wax-topped bottle. Blue wax showed up to celebrate a University of Kentucky national basketball championship. Holiday bottles marked Halloween, Thanksgiving, and Christmas.

Finally, in 2010, the new Maker's 46 bourbon was introduced, with much fanfare. Maker's 46 is 94 proof, slightly higher than the original. It is made by dumping mature Maker's Mark from its barrel, lining the barrel with ten additional charred oak staves, reintroducing the whiskey, and aging it for several more months. The name is derived from the number assigned to the charring process developed by Independent Staves (the barrel maker) owner Brad Boswell and former master distiller Kevin Smith to achieve just the right amount of char. The resulting bourbon is less sweet on the nose and a bit darker in color, and it shows more wood and spice than original Maker's Mark.

Bottles are decorated for various holidays.

Tasting at the end of the tour.

The site is also an arboretum, and spring brings beautiful blooms to the trees.

Travel Advice

Maker's Mark is located farther from a major highway than any of the other distilleries that offer tours, so more than a few would-be visitors have found themselves lost in the scenic Kentucky countryside in an effort to find it. This is especially true if you are heading to Maker's Mark on a dark December night for the “candlelight” tour (in reality, the candles are thousands of tiny fairy lights—no open flames in a distillery!). There are signs, but they are easy to miss.

From Bardstown, take East Stephen Foster Road just past My Old Kentucky Home State Park and turn right onto KY 49. This will take you past both Heaven Hill and Kentucky Bourbon Distillers along a wooded route. After about ten miles, staying straight puts you on KY 527. Follow this road for about four and a half miles to Burk Spring Road, and then follow the signs to Maker's Mark, about half a mile farther along.

Maker's Mark is half an hour south of Bardstown, and it takes about forty-five minutes to get to Bardstown from Louisville via I-65 or US 31E, or about an hour to get there from Lexington via the Bluegrass Parkway.

Nearby Attractions

Kentucky Cooperage (712 East Main Street, Lebanon, 270-692-4518, http://www.independentstavecompany.com), which makes barrels for all the bourbon distilleries except those owned by Brown-Forman, is less than twenty minutes east of Maker's Mark.

Limestone Branch Distillery (1280 Veterans Memorial Parkway, Lebanon, 270-699-9004, http://www.limestonebranch.com) is a small operation run by Beam descendants. They are currently selling a new, unaged whiskey (they actually call it “moonshine”). Tours are offered.

Lincoln's birthplace and boyhood home at Knob Creek are enshrined at the Abraham Lincoln Birthplace National Historical Park (2995 Lincoln Farm Road, Hodgenville, 270-358-3137, http://www.nps.gov/abli/index.htm), about a forty-five-minute drive from Maker's Mark.

The Lincoln Homestead State Park (5079 Lincoln Park Road, Springfield, 859-336-7461, http://www.parks.ky.gov/findparks/recparks/lh), his parents' courtship site, is about fifteen minutes north of Kentucky Cooperage.

Barrels display the Limestone Branch name.

Limestone Branch Distillery.

The Abbey of Gethsemani (3642 Monks Road, Trappist, 270-699-9004, www.monks.org), once home to philosopher Thomas Merton and known for the bourbon fruitcake and candies made by the Trappist monks, is about twenty minutes west of the distillery.

Jim Beam Distillery

149 Happy Hollow Road

Clermont, KY 40110

502-543-9877

Hours: Monday–Saturday, 9 a.m.–4:30 p.m.; Sunday, 12–4:30 p.m. Closed major holidays and Sundays in January and February.

Bourbons: Jim Beam White Label, Jim Beam Black Label, Jim Beam Choice, Devil's Cut, Baker's, Basil Hayden, Booker's, Knob Creek, Old Crow, Old Grand-Dad (86, 100, and 114 proof), Old Taylor

Ryes: Jim Beam Rye, Knob Creek Rye, Old Overholt Rye

Other Liquors: Red Stag (cherry-infused bourbon), Red Stag Honey Tea, Red Stag Spiced

Chief Executive: Matthew Shattock

Master Distiller: Fred Noe

Owner/Parent Company: Beam Global

Tours: Tours of the Clermont distillery and the American Stillhouse, with interactive exhibits, were added in 2012. There is an $8 admission fee.

What's Special:

- Jim Beam White Label is the best-selling brand of bourbon worldwide.

- Current master distiller Fred Noe is the great-great-great-great-grandson of Jacob Beam (who was distilling in Kentucky in the 1790s) and the great-grandson of the distillery's namesake, Colonel James Beam.

- Beam has a second distillery in nearby Boston, Kentucky, and bottling facilities in Frankfort.

- Beam started bottling bourbon in what has become a series of collectible decanters in the early 1950s.

- Booker's, the first barrel-proof, unfiltered bourbon available to the consumer market, was released in 1988.

- The Clermont location includes a 34,000-square-foot research and development facility.

- Members of the Beam family have had a hand in making at least sixty different brands of bourbon from several distilleries.

History

There is probably no more widely recognized name in the bourbon industry than Jim Beam, and not just because it is the best-selling bourbon brand in the world. Beam family members have been distillers in Kentucky for seven generations; these whiskey makers can all trace their roots to an eighteenth-century Pennsylvanian of German descent named Johannes Jacob Boehm.

By the time Boehm arrived in central Kentucky in the 1780s, he had Anglicized his name to “Beam.” He set up business as both a distiller and a miller near Blincoe (now Manton), about ten miles southeast of Bardstown. (Obviously, his occupations were connected, since milled grain could be made into whiskey.) One of Beam's sons, David, acted as his assistant, and they were selling whiskey by 1795.

David, who continued the business after his father's death in 1834, had two sons who also became distillers—David M. and John H. The latter founded Early Times Distillery nearby. John Beam named his bourbon to reflect his devotion to the traditional way of making whiskey in the “early times.” The Early Times Distillery continued to make bourbon throughout the nineteenth century and into the twentieth, changing owners more than once before being closed by Prohibition. It was during Prohibition that Brown-Forman, which needed additional stock to meet the demand for “medicinal” whiskey, bought the warehoused Early Times along with the brand name. Brown-Forman continues to make the brand at its Early Times Distillery in Louisville.

Jim Beam American Stillhouse Visitors Center and Gift Shop.

Meanwhile, David M. built a new distillery in about 1860, located northwest of Bardstown near the convent of the Sisters of Charity of Nazareth. (If you are driving south on US 31E into Bardstown, you'll see the twin towers of the church on your right. Warehouses on the former distillery property are now owned and used by Heaven Hill.) David M.'s son, James Beauregard Beam (yes, we've finally come to Jim Beam) and his brother-in-law, Albert Hart, took over the business and renamed it Beam & Hart Distillery. Among the bourbons they produced were Old Tub (rather prescient, considering how liquor was made during Prohibition), Pebbleford, Clear Springs, and D. M. Beam.

Around the turn of the century, the company was restructured and renamed Clear Spring Distillery, and it operated as such until it was closed by Prohibition. Jim Beam sold his interest in Clear Spring and purchased property at Clermont, where another victim of Prohibition, Echo Spring Distillery, had gone out of business. It was there that Beam and partners built a new facility after repeal. They called it the Jim Beam Distillery, and by 1934, Jim Beam bourbon was being made there.

When Jim Beam died in 1947, his son T. Jeremiah, who had been the company treasurer, assumed the presidency. He hired Booker Noe, his nephew and Jim Beam's grandson. Noe oversaw operations at the Churchill Distillery in Boston, Kentucky, which was purchased by Beam in 1953. Noe eventually became master distiller and developed the barrel-proof, small-batch Booker's bourbon. Today, Booker Noe's son, Fred, is master distiller at Jim Beam.

Jim Beam (both its Clermont and Boston locations) was sold in 1967 to American Tobacco. But Beam family members, including Baker and David Beam, who were distillers at the Clermont plant, continued to make whiskey for the company. Jim Beam is owned today by Beam Global, created out of parent company Fortune Brands.

Other Beams associated with other distilleries, including Parker and Craig Beam of Heaven Hill and Paul and Steve Beam of Limestone Branch, are members of the same distilling clan.

The Tour

With the opening of the American Stillhouse in September 2012, the Jim Beam tour changed completely. For years, no visitors were allowed in the working distillery. Happily, the tour has now gone to the other extreme, allowing hands-on interaction in the bourbon-making process.

The first stop is to buy tickets in the multistory Stillhouse, which features a replica column still that is actually a working elevator (imagine yourself evaporating and condensing as you ride). Visitors then board a bus for the short trip to the distillery. Along the way, your tour guide will narrate the impressive seven-generation distilling history of the Beam family. Fortunately, each visitor receives a card with pictures of the important players—from founder Jacob Beam to current master distiller Fred Noe—so you can keep track of who's who.

The bus arrives at a craft distillery within the larger distillery. Visitors are invited to scoop grain into a 750-gallon mash tub (the capacity of a regular mash tub at Beam is 10,000 gallons) and get a close-up of the small column still (producing about 3 gallons per minute) and the corresponding doubler. If production is at the right point, you might be able to help fill a barrel on the barrel porch behind the mini-distillery, or you might be asked to help dump a barrel. It's all pretty cool.

After covering the basics of the bourbon-making process in the mini-distillery, the tour moves on to the Big House, where Jim Beam is made. The 10,000-gallon-capacity mash tubs (or cookers) are making sour mash that will, in turn, be fermented into enough distiller's beer to keep the five-story-high column still turning out high wine at a rate of 200 gallons per minute. All this machinery is supervised by just two staff members seated in a computerized control room.

From the still house, the tour goes past the case house, a caged enclosure holding samples of all Beam products for a certain period of time—part of the distillery's quality-control regimen. Then you'll drop in on the action at one of the numerous bottling lines. There are so many lines bottling so many products that an HDTV monitor in the hallway keeps track of what's being bottled where. On a recent visit, bottling line J was packaging Jim Beam for shipment to Japan. Another monitor showed that 2,542 cases of product had been bottled by 10 a.m. on a shift that had started at 7:30.

Checking the color of Knob Creek during a tour tasting.

Then it's back past the case house to an exhibit that no other distillery can match. You don't even have to be a bourbon drinker to enjoy the room lined with lighted shelves displaying row after row of the famous Beam decanters. Produced between 1953 and 1992, the porcelain and glass decanters were designed in the shapes of automobiles, each of the fifty states, animals, celebrities, and much more. And who knew that the bottle that actress Barbara Eden materialized from in the 1960s TV sit-com, I Dream of Jeannie was a Beam decanter? It has its own pedestal here.

After viewing the decanter exhibit, visitors are bused back to a state-of-the-art tasting room.

The Bourbon

Since Beam makes so many products and state law limits you to two samples, Beam has borrowed a tasting technology from the wine industry. Everyone is given a plastic card upon entering the tasting room, which is furnished with several machines that dispense a whiskey sample into your glass when you insert the card and push a button for the desired selection. Choices range from Jim Beam Black Label and Red Stag Spice to Devil's Cut and Booker's. Technically, Red Stag whiskies are not bourbons, since by law, “no additives of any kind can be used to flavor or color any bourbon.” But that doesn't mean you won't enjoy them! Following are descriptions of some of the bourbons you can taste.

Bottles of Jim Beam wait in the bottling plant.

Bronze sculpture of the late Booker Noe, the master distiller who created Booker's bourbon.

Baker's is aged for seven years and bottled at 107 proof, so adding a little water helps reveal its layers of dark fruit, vanilla, caramel, and more than a hint of chocolate. The dark amber Baker's has an appealing nuttiness, too.

Basil Hayden has a higher proportion of rye in its mash bill than the other Beam bourbons. The rye and the bottling of the eight-year-old bourbon at 80 proof combine to give it a light, spicy character. No water is needed to bring out its flavors.

Booker's is one big bourbon. Bottled at the proof at which it comes out of the barrel, it usually weighs in at between 121 and 127 proof. Aged six to eight years, it is characterized by powerful vanilla and oak, which evolve into rich toffee on the tongue. A splash of water helps reveal a hint of spice at the finish.

Devil's Cut is a play on “angels' share,” since it is made with bourbon that would usually not escape from the barrel. After the bourbon is dumped, distilled water is added to the empty barrel, and a special process is used to extract the bourbon remaining in the red layer. The bourbon-flavored water is used to adjust the proof. The resulting 90-proof bourbon has rich vanilla, toasted pecan, and caramel notes.

Jim Beam Black Label is aged eight years—twice as long as the flagship White Label—and it is 90 proof. The adjective that works well for almost all aspects of its vanilla, corn, and oak notes is “toasty.”

Knob Creek is aged nine years and is bottled at 100 proof. Plenty of fruits and nuts keep the vanilla and caramel company. A touch of water brings out the orange in the nose.

Travel Advice

If you are coming from Louisville, take I-65 south to exit 112 (KY 245). Turn left (east), and you'll see Jim Beam on your left in just under two miles. The trip takes about half an hour from downtown Louisville. Coming from Lexington, take the Bluegrass Parkway west to exit 25 (US 150) and drive toward Bardstown. Turn right onto KY 245 and drive thirteen and a half miles to the distillery, on your right. This takes about ninety minutes.

If you want to drive directly to Bardstown from Louisville, take US 31E, which is Bardstown Road. It's a more scenic route and is actually a little faster than I-65.

The office building of the now-closed Chapeze Distillery, which served as a movie set for Stripes (1981).

Chapeze/Old Charter Distillery

About a mile's drive from Jim Beam, you can see what remains of the A. B. Chapeze Distillery, founded in 1867. The flagship bourbon brand was Old Charter, and the distillery was commonly referred to by that name. Like the vast majority of bourbon distilleries, it ceased production during Prohibition, although it did reopen after repeal and operated under various owners until 1951. The Old Charter brand produced today is made in Frankfort by Buffalo Trace.

Beam bought the property in 1970 and is still using the warehouses. A notable feature is the half-timbered-style building that once housed the distillery offices. The combination of the European-inflected architecture and the site's industrial feel made it a good location for filming the Russian outpost scene in the 1981 Bill Murray comedy Stripes. (Other Kentucky locations in the movie included Fort Knox and places around Louisville.) Who knew that a Kentucky bourbon distillery could stand in for Czechoslovakia?

To get to the former distillery, turn right as you leave Jim Beam, drive just over half a mile to the Forest Edge Winery, and turn right onto Chapeze Lane (County Road 3219). In another half mile you'll drive past the facility.

Bernheim Arboretum and Research Forest

Directly across the highway from the Jim Beam Distillery is a 14,000-acre forest subsidized by bourbon. German immigrant Isaac Wolfe Bernheim and his brother Bernard came to Kentucky in the nineteenth century and made a fortune from bourbon. The original Bernheim Distillery in Louisville produced I. W. Harper, Old Charter, Raven, and Mountain Dew (not to be confused with the fizzy green Pepsi product).

Bernheim felt tremendous gratitude to the city and state that allowed him to become a rich man. He and his brother were noted philanthropists, donating money to many local charitable causes. The statue of Thomas Jefferson that stands in front of the Jefferson County courthouse in downtown Louisville was one of their gifts. But their most lasting monument is a living one—Bernheim Forest (2499 KY 245, Clermont, 502-955-8512, www.bernheim.org).

Bernheim purchased the land, which had previously been farmed and logged, in 1928 and engaged the New York firm of Frederick Law Olmsted (designer of Louisville's parks system, as well as New York's Central Park) to design an arboretum. The landscaped portion of the facility is just a few minutes' drive from the entrance. The vast majority of the property is a natural, regrown hardwood forest crisscrossed by miles of hiking trails. It's a beautiful place for a break during your tour of bourbon country.

Fall color at Bernheim Forest.