Chapter Four

The Feds

FUCK THE STATE I WANT MY BROTHER BACK

—Katie Got Bandz

In one popular narrative, the changes I’ve examined so far in this book have occurred because conservatives have successfully waged a war on the welfare state. Antitax fanatic Grover Norquist summed up this plan with the eloquent and oft-repeated 2001 quote “I don’t want to abolish government. I simply want to reduce it to the size where I can drag it into the bathroom and drown it in the bathtub.”1 Liberals and other Democrats believe that far-right conservatives and other Republicans have succeeded in shrinking the New Deal state, and they’re well on their way to finishing the infanticide. At the same time, conservatives widely believe that liberals (particularly former president Obama himself) are out to exercise unprecedented control over American lives, from local bureaucrats all the way up to shadowy federal agencies like the NSA. What the evidence suggests is the worst of all possible scenarios: On this question, both sides are largely correct. The role of the United States government in its citizens’ lives has changed significantly over the past couple of decades, and this change has had a large impact on the development of young Americans.

As a percentage of gross domestic product, the Congressional Budget Office says that neither government outlays nor revenue has changed that much since the 1970s.2 Outlays have stayed at around one-fifth of GDP and revenues a few points below, yielding a deficit except for a couple of years around the turn of the millennium when the two switched places and we rode an irrationally exuberant economy to a small annual surplus. But spending only tells us about the dollars in and out: It doesn’t tell us anything about the composition of that spending, it doesn’t tell us where the money is actually going and whether, even though the spending has remained relatively consistent, the character of the government that is collecting taxes and spending them has changed. Thanks to the New Deal legacy, when we think of “government work,” many of us think of union jobs with solid middle-class wages, benefits, and a predictable advancement ladder. These government jobs might very well be the spending that conservatives most object to, and since 2003, the ratio of government employment to population has declined—steadily and then more rapidly in the last couple of years. Now, under 9 percent of the population works for the government (local, state, federal), a lower proportion than the lean times of Reagan rule.3

The state has, like all employers, benefitted from increases in productivity, and has been able to invest in technological improvements to reduce the number of employees required. And just like state universities outsourcing jobs to private firms, the federal government quickly increased the use of private contractors during the George W. Bush administration. Between 2001 and 2008, annual federal spending on contractors ballooned from the neighborhood of $200 billion to over half a trillion dollars.4 Nearly half of this spending ($248 billion in 2010, the last year in the White House report) was dedicated to defense contractors alone.5 When the federal government does decide to add new personnel, where they hire them says a lot about the state of state priorities: The Partnership for Public Service reports that 77.7 percent of new jobs were added by security-related agencies like Veterans Affairs, Defense, and Homeland Security.6 What little sustaining growth there is when it comes to federal employment is in the post-9/11 security sector, both in the “homeland” and abroad wherever American soldiers—and their better-paid and better-equipped contractor brethren—roam. Providing dependable middle-class careers is a shrinking part of that state’s role in the twenty-first century, and since Americans are working longer, this is disproportionately affecting young people. In 1973, over 19 percent of full-time civilian federal employees were under thirty years of age; by 2013, that number was down to 7 percent.

But just because the government isn’t hiring as many young people doesn’t mean it’s shrinking. Statistician Nate Silver broke down total government spending (local, state, and federal) between 1972 and 2011 in an attempt to suss out exactly where growth was coming from.7 Adjusted government spending as a portion of GDP increased 9 percent on balance over the time in question. Defense spending’s contribution to the balance was negative (-1.8 percent), which speaks not so much to a demilitarized America as to the end of the Cold War and the emergence of the US as a unipolar power. Infrastructure and service only added a tenth of a percent to total spending, with the 1.1 percent increase in “Protection and Law Enforcement” nearly offset by small declines in transportation, research, and education. The big increase, Silver (and every other analyst) found, is coming in entitlement spending, which makes up over 100 percent of the growth in the time he analyzed; Medicare and Medicaid costs alone make up more than half of the 9 percent increase.8 This problem isn’t particular to the state, as private spending on health care has jumped as well, more than doubling as a percentage of GDP since the 1970s, but entitlement programs are eating up a growing part of the federal budget.9 As Silver puts it, “We may have gone from conceiving of government as an entity that builds roads, dams and airports, provides shared services like schooling, policing and national parks, and wages wars, into the world’s largest insurance broker.” One of the most popular adjectives for Millennials is “entitled,” but the entitlement system wasn’t built for us.

4.1 Not-So-Entitled Millennials

During the last third of the twentieth century, government attempts to reduce poverty among the elderly have been incredibly successful. In 1960, a full 35 percent of Americans age sixty-five and over were living under the poverty line. Now it’s under 10 percent. Researchers at the National Bureau of Economic Research credit the entirety of this decrease to a doubling of Social Security expenditure per capita over the time in question.10 The elderly have gone from the poorest American age demographic to the richest, in no small part due to sizable increases in state support. The problem is, the system is based on the ratio of workers paying into the system to beneficiaries, and as the population ages, the ratio between workers and beneficiaries decreases.

In 1960, there were five workers per beneficiary, but by the time the last Baby Boomer retires, the ratio will be down to two to one.11 (And with wages stagnant, the jobs might not even be enough to support the people who work them.) In their 2014 reports, the Social Security trustees themselves estimate that by 2020 outgo will exceed total fund income; by 2033 the reserves will be totally depleted and new tax revenue will only cover 77 percent of scheduled benefits.12 Americans who retired in the 1980s received twice as much in benefits as they paid taxes into the system, but the ratio has been declining ever since.13 If the feds can only pay out 77 percent, Millennials will end up paying more into the system than they get in benefits. Based on the trustees’ reports, the decline in elder poverty may not be a permanent change to the national fabric; rather, it could simply refer to a sizable transfer to a particular cohort of workers born before the 1970s.

Millennials, despite mostly supporting Social Security, are not naive about how much they’ll benefit as compared to their elders. A March 2014 Pew study of Millennial attitudes toward entitlements revealed that a paltry 6 percent believe they will receive the full Social Security benefits that they’ve been promised, and 51 percent believe they will see no benefits at all.14 Think about that for a moment: The average dual-earner couple will pay over a million dollars in taxes into a system that more than half of Millennials think will leave them high and dry.15 Whether it’s generosity of spirit, utilitarian analysis, or plain old resignation, the so-called entitled generation doesn’t even feel entitled to our own entitlements.

Conservatives call Social Security a Ponzi scheme—the scam, made recently famous by Bernie Madoff, in which each new round of investors pays back the last one, creating the illusion of returns. It’s also called a pyramid scheme, because each new layer of investors has to be bigger, but the right wants to put the system on a secure footing with another popular scam called the stock market. They want workers to invest in their own private retirement savings accounts instead of government guarantees, hoping that higher-than-government returns will make up for the diminishing worker-beneficiary ratio.

Of course, any entitlement based on the fluctuating price of stocks isn’t much of an entitlement at all, and while some retirees might get lucky picking blue chips, conservatives would remove the “safety” in “safety net,” leaving the elderly who make the wrong investment decisions to live on the street and eat cat food, as the Democrat talking points go. Linking retiree benefits to the stock market would also tie the month-to-month wellbeing of one of America’s votingest demographics to the health of capital markets, and nothing would better ensure another round of bailouts than the threat of America’s current cohort of elderly people returning to mid-twentieth-century poverty rates. Practically speaking, to anchor social security in the stock market is to offer financiers a government guarantee. Liberals don’t really have a plan at all, except to safeguard current benefit levels and the retirement age and stall for time until the fund is depleted.

The reason? Neither party can really afford to piss off America’s wealthiest and most organized age demographic. The American Association of Retired Persons (AARP) claims 37 million members age fifty and over. It’s a nonprofit (with a for-profit arm, of course), and one of the biggest, most influential ones in the country. The AARP’s two publications have larger circulations than any other magazines in the country, and they reap over $100 million a year in advertising fees. In 2013, the association brought in over $1.4 billion16 in operating revenue, including $763 million in royalties from AARP-branded product and service providers.17 The aged are a big and growing market, and AARP is a name they can trust. The AARP spends millions of dollars a year in lobbying on issues like health care, taxes, and entitlement reform, and they’ve been incredibly successful.18 They pushed through and then protected one of the greatest antipoverty achievements in modern memory in Supplemental Security Income, changing the way the old and elderly live in this country. The AARP made Social Security the original third rail of American politics, and made sure politicians know not to betray their members’ interests. It’s a great strategy, and they’ve used it to make the government work for them. Kids, on the other hand, can’t vote, and they don’t have an AARP to join. And it shows.

4.2 The Juvenilization of Poverty

Before the late 1960s, the poverty rates for children, middle-aged adults, and seniors were all dropping along the same schedule, following the same slope down as shared living conditions improved. The elderly had the highest proportion of poor people, kids were next, and working-age adults dragged the total number down. But when children’s poverty plateaued in the early 1970s, Medicare and nationalized Social Security payments kept rates falling for the elderly. In 1974, around when our story begins and a few years before the first Millennials were born, children’s poverty overtook the rate for seniors. Since then, children’s poverty has gone through a few cycles but has never dropped to 15 percent, where it had been earlier. Meanwhile, as we’ve seen, the elderly became the least-poor age demographic. By 2012, more than one in five American kids lived below the poverty line, and at 21.8 percent, the portion of children in poverty was more than twice as high as for those over sixty-five (who were at 9.1 percent).19 Social scientists call this switch in fortunes between the old and young the “juvenilization of poverty.”

While the elderly and their advocates have been able to protect and even grow their cash payments, poor children haven’t exercised the same kind of leverage. In 1996, President Clinton ushered in welfare reform, replacing the Aid to Families with Dependent Children with the somewhat hectoring tone of Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF). The condescending Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Act put a lifetime cap on federal assistance at sixty months, required beneficiaries to find work, and left most of the details up to state governments—practically encouraging conservative state legislatures that are ideologically opposed to welfare to sabotage the system’s operation. In most of the southern states, maximum TANF benefits amount to less than one-fifth of what it takes to live at the federal poverty line.20 The programs that serve the elderly are built to succeed, whereas many if not most of TANF’s architects would rather it not exist at all.

In 2012, the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP) released a report for the sixteenth anniversary of TANF, assessing its effectiveness as a replacement program. Because TANF gets the same $17 billion in federal appropriations every year, the real value of this sum has declined with inflation; the AARP knows that trick, Social Security has a built-in Cost of Living Adjustment that keeps benefits’ purchasing power steady over time as prices rise.21 The rise in childhood poverty, the declining real funds, and the new law’s restrictions have meant that the percentage of families with children in poverty receiving welfare benefits has plummeted. At the time of TANF’s enactment, AFDC covered 68 out of every 100 families with impoverished kids—down from 82 in 1979. By 2014, it was down by more than half, to 23 percent. As the CBPP report put it, “TANF caseloads going down while poverty is going up means that a much smaller share of poor families receive cash assistance from TANF than they did prior to welfare reform.”22 Insofar as this was the intention, the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Act has been successful. It’s simplistic to say that an anomalously rich cohort of elderly people has been starving poor children of tax dollars. It’s also not wrong.

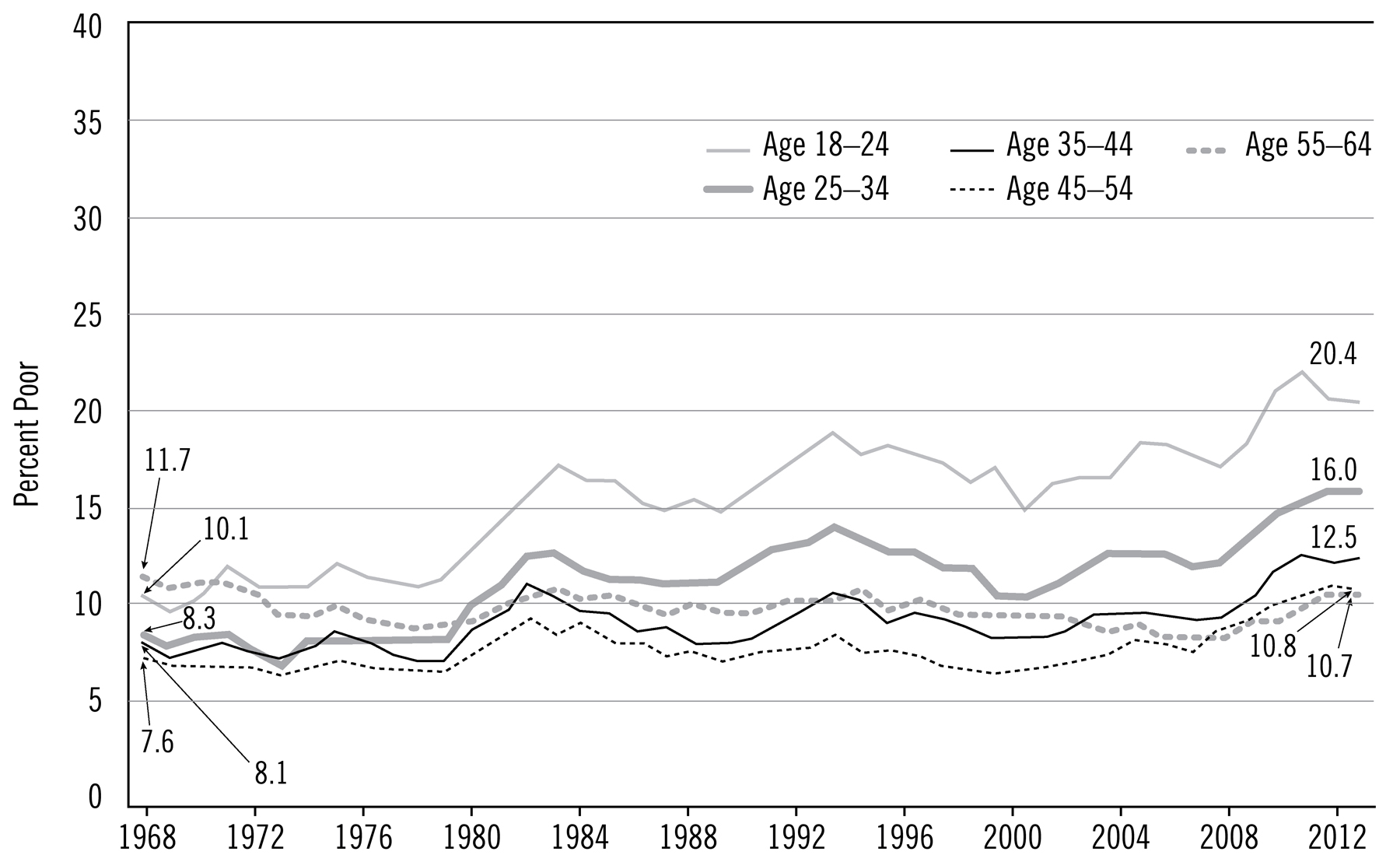

In a 2014 report, the Stanford Center on Poverty and Inequality divided the nonelderly adult poverty data by age cohort for the period 1968 to 2012.23 What their findings suggest is that it’s not how old you are that matters, it’s when you were born. The fluctuations in the poverty rate for adults age eighteen to twenty-four over the time in question look a lot more like the child than the adult rate. Now they come in at 20.4 percent—less than a point and a half below the childhood number. During the 1980s, the pattern settled: All things being equal, the younger you are, the better the chances that you’re poor. Since then, the spread between different age groups has widened. In 1968, at the high point of twentieth-century Western intergenerational tension, there was no correlation between a nonelderly adult’s age and their poverty rate, and all groups had rates within the small range of 8 to 12 percent. Now young adults are impoverished at nearly twice the rate of older adults (20.4 vs. 10.8 percent in the Stanford study). If you’re trying to avoid being poor in America, since 1974 it has been better to be older and worse to be younger.24

Poverty Rates for Nonelderly Adults by Age Cohort, 1968–2012

Given the state of the American social insurance system and of Millennial wealth accumulation, this age distribution trend isn’t likely to hold. It seems fair to conclude that the US government did not permanently “solve” elder poverty, but instead transferred huge amounts of money to a few birth cohorts. If the Social Security trust fund runs short as predicted, then by the end of the century, the graph of the elder poverty rate over time might very well look like a deep bowl, with a low bottom for Americans born between 1915 and 1965, and sharp rises on both sides. Life-span extension could accelerate the trend, with the number of seniors increasing faster than expected as they routinely live into third and fourth decades of retirement. Government actuaries find themselves in the unenviable position of hoping people don’t live too long.

These uneasy trends reemphasize that though relations between the young and the old have some immutable elements, they aren’t fixed. It’s a question of what kind of place you’re born into, not just geographically or socioeconomically, but historically. There are lucky times and places to be born, and unlucky times and places. In America, the relatively lucky time for the average person to be born appears to be past. This is another way of putting the now widely published line that today’s children and young adults are, for the first time, worse off than their parents. When history teachers talk about government policy decisions, they tend to use the progressive frame: The government improves things over time. While liberals think conservatives slow down or rewind progress, and conservatives are only willing to accept government policy forty or fifty years after its implementation (at which point they want an equal share of the credit), both agree that America is improving itself, and improving the world as it goes. This simplistic historical perspective doesn’t jibe with the reality: Somehow, things got worse.

4.3 Left Behind in the Race to the Top

Education is one of the areas of public life where American policymakers claim a lot of credit for progress. Despite all the anxiety about how US students stack up internationally, more young people are reaching higher levels of schooling, becoming more attractive potential employees. Each generation of Americans may not be better off, but they are definitely better educated. Changes at the federal level have pushed this performance inflation until it became law. Twenty-first-century primary and secondary education reform is all about efficiency and rationalized process.

In 2001, President Bush signed into law the No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB), reauthorizing what are called Title I funds (federal cash for school districts with a high percentage of impoverished students). Like welfare reform, NCLB leaves a lot up to the states, while maintaining federal standards and goals. Although it doesn’t mandate which tests the states have to administer, participating schools have to assess their kids with a statewide standardized exam every year. The name of the law isn’t quite literal, but schools were required to achieve 95 percent participation among all groups.25 Performance inflation is written into the law as Adequate Yearly Progress, or AYP: Every year, students at any given grade level have to be testing better than the students at that grade level the year before. It’s progress by declaration. According to NCLB, all students should be “proficient” or above by now.26 Well-adjusted adults have no problem admitting there are subjects in which we underperform, but it’s the official policy of the US government that all kids will be up to snuff at everything.

The penalties for not reaching your AYP goals are quick and harsh: Two years of failure means students are allowed to jump ship and head to a better school in the district, and after five the state takes over administration.27 Many schools don’t survive their sixth year of AYP failure; they’re closed or turned into charters. A lot is riding on a poor school’s ability to achieve the quantitative standards set up at the state and federal levels. The law is effective at incentivizing school administrations to meet their yearly progress goals, but that’s not the same as incentivizing them to improve instruction or learning. Instead, it’s about compelling schools to generate the right kind of data. The state accepts these assessment reports as valid representations of educational quality, so administrators and teachers—and most of all, students—have to generate the right reports.

Schools have found a lot of ways to improve their scores, demonstrating the kind of innovation that happens when the state puts a gun to your head. They’ve reduced arts and music time in favor of tested subjects like math and reading. Teachers spend instructional time telling kids how to fill out bubbles correctly and how to narrow choices to make a better guess. Critics call this “teaching to the test,” and it’s predictable and worrisome. If you threaten a school with heavy sanctions, it’s no surprise that teachers will tend toward instruction geared to test performance, whether or not that’s the best thing for young people’s intellectual development. They will also find ways to twist the rules to their advantage by encouraging underperforming kids to drop out or stay home on testing days, or misleading high-performing students about their right to opt out of the tests. NCLB reoriented compulsory public school around the tests, and now teachers and administrators can either pour an extraordinary amount of their time and energy into complying and excelling, or they can find a new line of work.

Or they can cheat outright. The National Center for Fair & Open Testing compiled a list of more than fifty ways that schools have been caught manipulating their state testing numbers.28 The superintendent of Atlanta’s school district was indicted for racketeering after it was discovered that her nationally celebrated results were a sham: She was presiding over a giant conspiracy to defraud state and federal education authorities. From rigging testing classrooms so as to make cheating easier, all the way to teachers getting together to erase wrongs answers and fill in the right ones, schools have found and made use of work-arounds. Classrooms and teachers that look alike on paper might very well be totally different in ways the test can’t see. Meanwhile, anything that’s enjoyable or nurturing about school falls away if it can’t be made to serve the tests.

Public school districts in areas with large low-income populations are stuck in a trap: They’re being judged by the tests, as well as by graduation rates and the careers they prepare students for, but if they dedicate themselves to vocational training for middle-income jobs, of which there are fewer and fewer anyway, then whatever richer families are left will flee the district and bring down the metrics further. Scholar Nicole Nguyen found one district that’s trying to thread the needle with an unconventional strategy: The whole place is focused on national security. The district in pseudonymous Fort Milton is near Washington, DC, nestled in the growing security sector. That’s where the local jobs are—on both sides of wage polarization, since even the NSA’s lawn care professionals need security clearances—so that’s where the district put its effort. It doesn’t hurt that there are lots of private and public interests happy to help, as long as there’s something in it for them.

On its face, this sounds like symbiosis, or making the best of a bad situation. But some of Nguyen’s observations border on the horrific. A Milton high school principal bragged about their “kindergarten-to-career pipeline,” explaining that instead of counting apples, five-year-olds are counting fire trucks. “We need to catch them at that early age,” he says.29 It starts innocuously enough, but by algebra they’re calculating parabolas using the trajectory of an American sniper’s bullet in North Korea.30 Military police literally patrol the hallways. Nguyen can’t find much evidence that the program is actually transitioning students into national security jobs, even though “students were made to believe that they could and would secure jobs in the security industry as long as they could obtain a security clearance.”31 Regardless, military contractors have been happy to make Milton schools a showroom for edtech products, even if they’re not about to hire a bunch of Milton High graduates.

The innovative thinking behind turning a school district into a private-public war academy is exactly what education reform is supposed to generate. Milton picked up a number of sizable federal grants when it switched to a security focus, which makes any district look good. Nguyen writes that “Milton’s story points to how remaking public education for corporate-and military-oriented exigencies necessarily relies on the active role of the state, whether through funding, resources, or curriculum.” But the federal government can’t go in and reshape every school district, and even if they could, they wouldn’t be any good at it. Instead, the feds have used an effective strategy with which we’ve become familiar: Put a big pile of money at the top of a hill and yell, “Race!”

Like welfare reform, contemporary education reform seems at least as devoted to tearing the past system down as to improving it. In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, as part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act stimulus plan, the Obama administration put forward a $4.35-billion plan to postmodernize education. “Race to the Top” was quite literally a contest in which states competed for grants ranging from $17 million to $700 million based on school achievement and standards compliance. Trying to make over thirteen thousand districts across fifty states operate using the same curricula and testing standards is a logistical and political nightmare, so instead of trying to compel states to change the way they operate, the Obama administration let them race to rationalize. The program set up a 500-point rubric, in which states receive credit for trendy and ill-defined achievements like “using data to improve instruction” and “supporting the transition to enhanced standards and high-quality assessments.”32 It’s a cost-effective way for the federal government to institute a series of reforms that it has no constitutional authority to mandate and no bureaucratic bandwidth to administer.

The most controversial of the Race to the Top provisions was forty points for adopting “common” standards.33 The Common Core State Standards Initiative seeks to unify K-12 grade-level standards across the country, and it has met with a lot of resistance, mostly from conservatives who resent the Obama administration’s overreach in meddling with the way they educate their children. But conservatives weren’t the only ones upset: Some liberal and left-wing educators worry that the unified curricula are stultifying, crowd out more engaging pedagogy, and are too focused on test preparation. Both critiques were well founded; the feds defining an annual rate of progress for every child in the country from the time they enter school until adulthood does sound like the kind of dystopian plot a tyrannical state might undertake in an effort to create a more uniform population. And centering the academic development of American kids on math and language arts testing standards is shortsighted at best, and deeply harmful at worst.

Standardization, as we’ve seen in the labor market, is an important part of a rationalization process that’s ultimately about lowering costs. Once we’ve turned educational achievement into a set of comparable returns, the policymakers and bureaucrats can focus on getting the same returns for less money. We can read this trend in the other Race to the Top scorecard items, like “improving teacher and principal effectiveness based on performance.”34 Students themselves don’t have any representation, of course, even though any change in curriculum, assessments, or standards affects their lives as much as anyone’s. The national education reform plan, under Republicans and Democrats, is to increase student scores. The explicit reason the increases are needed, politicians tell us, is so that kids will be ready for college and the workforce. Besides the fact that some children must be left behind if they’re all racing to the top, job training is a lousy way to spend ages five to eighteen. Even worse if it’s standardized across the whole country.

The entire way we talk about education turns students into lab rats, objects of experimentation and feedback, and Millennials were born in captivity. Stakeholders work out compromises and decide on procedures in order to create kids who will fill out the right bubbles on their standardized tests. From all the rhetoric about preparation (the Common Core calls itself “a set of clear college-and career-ready standards for kindergarten through 12th grade in English language arts/literacy and mathematics”—I wonder if these standard-makers don’t feel just a bit silly talking about career-ready six-year-olds),35 it’s clear the American public education system is a rapidly rationalizing factory for producing human capital. They think once every school is on the same page, they can turn up output like they’re producing bottle caps or bars of steel. If employers need a lot of skilled workers, then the state will provide. The workers might not be happy, but they’ll know how to work. For kids who don’t (or can’t) fit the mold, however, getting along has become more difficult. We can draw a straight line between the standardization of children in educational reform and the expulsion, arrest, and even murder of the kids who won’t adapt.

4.4 Cops

As much as policymakers wish they could erase all the differences between students except for how high their scores are, there’s (thankfully) far too much variation for this to be feasible. The kind of scholastic training we have requires kids to be at least manageable if it can’t make them all the same. That is, they must be instructable up to the minimum common standard, display adequate progress, and not interfere with anyone else’s learning. If a kid can’t manage these three things, then the school is forced to take further action. As the demand for human capital has broadened, the educational project’s stakes are higher, and the higher the stakes, the lower the tolerance for disruption. The result has been schools that are disciplined and policed as if the system’s goals were career preparation first and punishment second.

As we saw earlier in the section on risk elimination and zero-tolerance discipline, the modern classroom aspires to total control, to be a space where education can progress according to policymakers’ predictions and employers’ needs. To standardize all those students in peace, teachers and administrators have to excise the disruptive elements. School officials have accomplished this by removing more and more kids from class. A comprehensive study by Daniel J. Losen and Tia Elena Martinez of UCLA’s Civil Rights Project tracked the shocking increase in suspensions at American primary and secondary schools. Comparing data from the 1972–73 and 2009–10 school years, Losen and Martinez found that the elementary school rate increased from .9 percent to 2.4 percent, while the secondary school rate increased from 8 percent to 11.3 percent.36 That’s millions of American kids who are given the scholastic equivalent of a felony conviction every year.

As if the ostensible motive for the increase in suspension—efficiency—weren’t sinister enough, there’s not much evidence that suspensions have a positive effect on the resulting learning environment. In a report for the Southern Poverty Law Center (“Suspended Education: Urban Middle Schools in Crisis”), Losen and coauthor Russell J. Skiba examined the studies on suspension rates and how they affect classroom ecology:

There are no data showing that out-of-school suspension or expulsion reduce rates of disruption or improve school climate; indeed, the available data suggest that, if anything, disciplinary removal appears to have negative effects on student outcomes and the learning climate. Longitudinal studies have shown that students suspended in sixth grade are more likely to receive office referrals or suspensions by eighth grade, prompting some researchers to conclude that suspension may act more as a reinforcer than a punisher for inappropriate behavior. In the long term, school suspension has been found to be a moderate-to-strong predictor of school dropout, and may in some cases be used as a tool to “cleanse” the school of students who are perceived by school administrators as troublemakers. Other research raises doubts as to whether harsh school discipline has a deterrent value.37

Suspensions are a way to separate out students according to the arbitrary passions of teachers and administrators. Despite the frequent moral panics about school violence, the vast majority of suspensions are for nonviolent and often incredibly vague offenses like tardiness, disrespect, and classroom disruption. In fact, the number of in-school victimizations (like assault and robbery—crimes where people are harmed) has dropped precipitously in both absolute and relative terms (along with crime nationally) since the 1990s. The number of violent attacks was cut by more than half between the 1992 and 2011 school years, while theft declined 77.5 percent.38 School violence is a red herring used to justify an increasingly petty and aggressive school discipline system. And as the stakes of childhood have grown, so have the consequences for kids who fall afoul of the school cops.

Like every other single trend in this story, the rise in suspension rates has not been evenly distributed. While suspensions have increased significantly for students in all demographics, there is a huge racial disparity. K-12 suspensions for white students increased from 3.1 to 4.8 percent between 1973 and 2006, while the rate for all nonwhite students more than doubled. Black students were suspended two and a half times as often (up from 6 to 15 percent) as in the 1970s, making them three times as likely to be removed from the classroom as whites.39 The numbers for high schoolers are even more dramatic: Nearly a quarter of black high schoolers are suspended, a 100 percent increase over the time in question, while only 7.1 percent of white high schoolers get sent home (up from 6 percent).40 These discrepancies start as soon as children enter schooling; a 2014 report from the Department of Education found that black students represent 18 percent of preschool enrollment but 42 percent of preschool students suspended once and 48 percent of students suspended more than once.41

Lately, it’s not just school cops that kids have to worry about. Real officers and the criminal justice system they represent no longer stop at the schoolhouse gate. Classrooms are better policed in a metaphorical sense by teachers wielding suspensions, but also literally, by the police. For her 2011 book Police in the Hallways, Kathleen Nolan embedded in a New York City public high school in an attempt to learn how the new discipline was playing out in cities across the country. What she saw was closer to an authoritarian dystopia than the popular image of American high school. Nolan writes that the school felt like a police precinct or a prison, with all sorts of high-tech security apparatuses and crime-oriented discipline practices: “Handcuffs, body searches, backpack searches, standing on line to walk through metal detectors, confrontations with law enforcement, ‘hallway sweeps,’ and confinement in the detention room had become common experiences for students….Penal management had become an overarching theme, and students had grown accustomed to daily interactions with law enforcement.”42 School administrators knew police were in charge, and police knew the same. Students did too. Teachers threatened students with prison, if not immediately, then as their inescapable future.

Bringing the police into schools to patrol the hallways and intervene in noncriminal matters, along with the increased use of suspensions, is an intensification of school discipline, analogous to the intensification of the production of human capital. The system is geared to churn out more skilled workers, but it’s also meant to produce prisoners. This harsh reality lurks behind every “joke” all the teachers, counselors, and administrators tell their students about ending up in prison if they don’t work hard. They can try to justify the discipline with a “tough love” philosophy, but there’s no love here. The mark of “troublemaker” can be just as bad for your life outcomes as actually making trouble, especially if you’re black or Latinx.

America’s criminal justice system needs lives to process, and our schools are obliging by marking more kids as bad, sometimes even turning them over directly to the authorities. Nolan compares the changed atmosphere of school discipline to the changed nature of American criminal justice: “Despite critiques of the overuse of the criminal-justice system, some educators become dependent on its strategies in much the same way that neoliberal criminal-justice administrators have come to rely on low-level forms of repression, such as zero-tolerance community policing, as forms of prevention.”43 (Outside of schools this is often called “broken window” policing.) The overarching effect—if not the goal—of such low-level forms of repression at the scholastic and adult levels is to separate out black people from American civil society, and it has been getting much worse. Despite the media’s efforts to get us to picture generic Millennials as white, black victims of these policies are no less “Millennial” than their white peers; in fact, insofar as they are closer to the changes in policing, they are more Millennial.

Once again, the progressive story about public schools making the country more equal by breaking down racial barriers to achievement does not accord with the trends and statistics. Neither does the common excuse that schools are doing their best to combat inequality in the broader society. Instead of imagining that the current state of school discipline is a malfunction in a fundamentally benevolent system, it seems more likely that one of the education system’s functions is to exclude some kids. When I look at school discipline in the context of declining violence and a lack of evidence that suspensions are effective at improving students’ learning conditions, I can only conclude that the actual purpose of such discipline, at a structural level, is to label and remove black kids (disproportionately) from the clearly defined road to college and career. Just as they have increased human capital production, schools have increased the production of future prisoners, channeling kids from attendance to lockdown. The school system isn’t an ineffective solution to racial and economic inequality, it’s an effective cause.

4.5 Pens

The liberal idea of the relation between poor children and the government is that the state has abandoned them to historical inequity, uncaring market forces, and their own tangle of pathologies. The racism isn’t well veiled in this last part. Jonathan Chait, the liberal writer for New York magazine, gives the most concise version of this “cultural” argument for racial inequality: “It would be bizarre to imagine that centuries of slavery, followed by systematic terrorism, segregation, discrimination, a legacy wealth gap, and so on did not leave a cultural residue that itself became an impediment to success.”44

A combination of well-tailored government programs and personal responsibility—a helping hand and a working hand to grab it—are supposed to fix the problem over time. Pathologies will attenuate, policymakers will learn to write and implement better policies, and we can all live happily ever after. The problem with the relationship between poor black and brown children and the state, liberals contend, is that it’s not tight enough. Analysts speak of “underserved” communities as if the state were an absentee parent. If kids are falling behind, they need an after-school program or longer days or no more summer vacation. Unlike for the rich, who have to pay for it, for the poor, the state is a solution, not a problem. There’s just one fly in the ointment: The best research says that’s not really how the relationship works at all.

For his 2011 ethnography Punished: Policing the Lives of Black and Latino Boys, sociologist Victor M. Rios went back to the Oakland, California, neighborhood where he had grown up only a few decades earlier to talk to and learn from a few dozen young men growing up in a so-called underserved neighborhood. What he discovered was a major shift in how the law treated the young men he was working with. “The poor,” Rios writes, “at least in this community, have not been abandoned by the state. Instead, the state has become deeply embedded in their everyday lives, through the auspices of punitive social control.”45 He observed police officers playing a cat-and-mouse game with these kids, reminding them that they’re always at the mercy of the law enforcement apparatus, regardless of their actions. The young men are left “in constant fear of being humiliated, brutalized, or arrested.”46 Punished details the shift within the state’s relationship with the poor, and the decline of a social welfare model (as we saw earlier in the chapter) in favor of a social control model. If the state is a parent, it’s not absent; it’s physically and psychologically abusive.

One of the things Rios does best in his book is talk about the way just existing as a target for the youth control complex is hard work. He calls the labor done by the young men he observed to maintain their place in society “dignity work.” Earlier, I wrote that a Millennial’s first job is to remain eligible for success, which involves staying sane and out of jail. Before a young person can compete to accrue human capital, they have to be part of free society. The police exist in part to keep some people at the margin of that free society, always threatening to exclude them. “Today’s working-class youths encounter a radically different world than they would have encountered just a few decades ago,” Rios writes. “These young people no longer ‘learn to labor’ but instead ‘prepare for prison.’”47 The data backs him up: A 2012 study from the American Academy of Pediatrics found that “Since the last nationally defensible estimate based on data from 1965, the cumulative prevalence of arrest for American youth (particularly in the period of late adolescence and early adulthood) has increased substantially”:

If we assume that the missing cases are at least as likely to have been arrested as the observed cases, the in-sample age-23 prevalence rate must lie between 30.2 percent and 41.4 percent. The greatest growth in the cumulative prevalence of arrest occurs during late adolescence and the period of early or emerging adulthood.48

Along with other kinds of youth labor, dignity work has grown. It’s harder now for kids to stay clear of the law. All of the trends in school discipline (increasingly arbitrary, increasingly racist, and just plain increasing) play out the same way at the young adult level. There are many explanations for the rise of American mass incarceration—the drug war, more aggressive prosecutors, the 1990s crime boom triggering a prison boom that started growing all on its own, a tough-on-crime rhetorical arms race among politicians, the rationalization of police work—and a lot of them can be true at the same time. But whatever the reasons, the US incarceration rate has quintupled since the 1970s, and it’s affecting young black men most of all and more disproportionately than ever. The white rate of imprisonment has risen in relative terms, but not as fast as the black rate, which has spiked. The ratio between black and white incarceration increased more between 1975 and 2000 than in the fifty years preceding.49 Considering the progressive story about the arc of racial justice, this is a crushing truth.

Mass incarceration, at least as much as rationalization or technological improvement, is a defining aspect of contemporary American society. In her bestselling book The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, law professor Michelle Alexander gives a chilling description of where we are as a nation:

The stark and sobering reality is that, for reasons largely unrelated to actual crime trends, the American penal system has emerged as a system of social control unparalleled in world history. And while the size of the system alone might suggest that it would touch the lives of most Americans, the primary targets of its control can be defined largely by race. This is an astonishing development, especially since given that as recently as the mid-1970s, the most well-respected criminologists were predicting that the prison system would soon fade away….Far from fading away, it appears that prisons are here to stay.50

The rise of racist mass incarceration has started to enter the national consciousness, but though the phenomenon coincides with Millennials’ growth and development, most commentators don’t connect the two. I insist that we must. If the change in the way we arrest and imprison people is a defining aspect of contemporary America—and I believe it more than qualifies—then it follows that the criminal justice system also defines contemporary Americans, especially Millennials. Far from being the carefree space cadets the media likes to depict us as, Millennials are cagey and anxious, as befits the most policed modern generation. Nuisance policing comes down hard on young people, given as they are to cavorting in front of others. Kids don’t own space anywhere, so much of their socializing takes place in public. The police are increasingly unwilling to cede any space at all to kids, providing state reinforcement for zero-risk childhood. What a few decades ago might have been looked upon as normal adolescent hijinks—running around a mall, horsing around on trains, or drinking beer in a park at night—is now fuel for the cat-and-mouse police games that Victor Rios describes. It’s a lethal setup.

4.6 Murderers

It’s dangerous to be policed. We use the “cat-and-mouse” metaphor since it’s readily at hand, but it camouflages the human stakes. Because police officers interact with Millennials more than they have with kids in the past, we’re more likely to be the victims of state violence. We’ve already seen how that happens with harassment and arrests, but when the authorities engage young people—especially young people of color—there’s another much greater risk. It’s empirically the case that, a certain percentage of the time, America’s armed police will murder people. It’s a cost that we must consider before implementing any plan to increase law enforcement, but policymakers caught up in tough-on-crime madness overlooked it. And that’s the charitable judgment; some Americans just don’t care about people whom the police happen to kill.

The systematic exclusion of young black and brown Americans reaches its most visible and horrific level when the state’s armed guards execute them in public, only to face the most minimal consequences, if any at all. Extrajudicial and pseudojudicial violence against racial minorities has always been a flashpoint in American society, but the qualitative change in policing over the past few decades (combined with new communications technologies) has caused this particular form of injustice to take on new resonance. A number of egregious police murders have entered the national spotlight, and though not all of them have featured young victims killed in public, many of them have.

These stories share a series of disturbing commonalities. As the police ratchet up their control of public spaces, hyperattuned to the presence of young black Americans, they put these communities in grave danger. The police, by treating their lives so casually and with such disdain, spread the message that these people aren’t worth anything. No one has heeded the state’s message quite like the private citizens who have taken the spirit of the law into their own hands and murdered black kids; Trayvon Martin, Renisha McBride, and Jordan Davis are some of the better-known victims. As long as state institutions keep pushing the message that these children and young adults are appropriate targets for violence and control, they’re responsible for the climate they create.

State power in the twenty-first century reaches its apex in these extrajudicial murders. From the withdrawal of welfare support for the segregated schools to the lethal police flooding the street, the American government is a predator. Whether an individual Millennial is a target or not, they see all this happening to others in their cohort. So it’s no surprise Millennials don’t trust the state: Fewer kids are being helped by it, and more are being harmed. Solving pain and deprivation with today’s government is like trying to stitch a wound with a flyswatter. The liberal solution to inequality and poverty—welfare state cooperation with individual gumption—is no solution at all, and not for the reasons conservatives moaning about welfare think. Unfounded assumptions about government benevolence have allowed the state youth control complex to mutate into this highly aggressive form. Nate Silver was only half right: America is an insurance company and an occupying army.