Chapter Six

Behavior Modification

Sissy: We’re not bad people, we just come from a bad place.

—Shame (2011)

In economics, they measure costs in time, effort, and ultimately money. In this book, I’ve used the same categories to talk about how the costs of producing human capital have passed to workers over the past few decades. The Millennial character is a product of life spent investing in your own potential and being managed like a risk. Keeping track of economic costs is important, especially when so few commentators and analysts consciously consider the lives of young people in these terms. Growth and the growth of growth are what powers this system, and we’ve seen how that shapes Americans into the kinds of workers it needs, and what that process costs in terms of young people’s time, effort, and debt capacity. But there are other kinds of costs as well. Just because economists don’t consider the psychic costs for workers who have learned to keep up with contemporary capitalism, that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t.

More competition among young people—whether they want to be drummers, power forwards, scientists, or just not broke—means higher costs in the economic sense, but also in the area of mental health and social trust. If Americans are learning better and better to take whatever personal advantage we can get our hands on, then we’d be fools to trust each other. And as the stakes rise, we are also learning not to be fools.

In March of 2014, Pew Social Trends published the results of a survey taken between 1987 and 2012 on whether or not “generally speaking, most people can be trusted,” broken down by generation.1 The Silent Generation was able to pass most of their trust to the Baby Boomers, but Gen X took the first half of the 1990s hard, dropping all the way to 20 percent before edging up over 30 percent by the end of the survey period. But if Gen Xers are more cautious than their parents, Millennials are straight-up suspicious. Only four data points in, except for a brief Obama bump, we’ve hovered around 20 percent, dropping to 19 percent by 2012. The rate of American suckers born per minute shrank by half in twenty-five years.

When we think about the environmental conditions under which young Americans are developing, a lack of trust makes sense as a survival adaptation. A market that doles out success on an increasingly individual basis is not a strong foundation for high levels of social interdependence. With all youth activities centered on the production of human capital, even team sports become sole pursuits. Add this to the intensive risk aversion that characterizes contemporary parenting and the zero-tolerance risk-elimination policies that dominate the schools and the streets, and it’s a wonder Millennials can muster enough trust to walk outside their own doors. The market and the institutions it influences—from the family, to the schools, to the police—select for competitiveness, which includes a canny distrust. Parents and teachers who raise kids who are too trusting are setting them up for failure in a country that will betray that trust; the black and Latinx boys in Victor Rios’s Punished learn very quickly that they can’t trust the authorities that are supposed to look out for them. Generalized trust is a privilege of the wealthy few for whom the stakes aren’t so high, those who are so well-off they can feel secure even in a human-sized rat race. For everyone else, the modern American condition includes a low-level hum of understandable paranoia and anxiety. That’s a cost too.

6.1 Bad Brains

There’s a big difference between 40 percent of the population finding others trustworthy and 20 percent. Obviously, there’s the quantity—a combination of factors cut the trust rate in half—but there’s also a qualitative difference between living in the first country and living in the second. The ways we interact with each other and think about the people around us are highly mutable, and they shift with a society’s material conditions. We aren’t dumb, we’re adaptable—but adapting to a messed-up world messes you up, whether you remain functional or not. The kind of environment that causes over 80 percent of young Americans to find most people untrustworthy is likely to have induced additional psychic maladies, and there has been no institutional safeguard to put the brakes on the market as it has begun to drive more and more people crazy.

No researcher has spent as much time examining the comparative mental health of American Millennials as psychologist Jean M. Twenge of San Diego State University, the author and coauthor of numerous papers and books on the topic. Twenge’s most meaningful insights come from historical meta-analyses of results from decades of personality surveys. Her methodology is premised on the idea that the generation a person is born into has an important impact on their state of mind, at least as deep as the two traditionally recognized correlates of personality: genetics and family circumstance. Twenge describes her outlook in her 2000 paper “The Age of Anxiety? Birth Cohort Change in Anxiety and Neuroticism, 1952–1993”:

Each generation effectively grows up in a different society; these societies vary in their attitudes, environmental threats, family structures, sexual norms, and in many other ways. A large number of theorists have suggested that birth cohort—as a proxy for the larger sociocultural environment—can have substantial effects on personality.2

In “The Age of Anxiety?” Twenge compares dozens of surveys, taken between 1952 and 1993, that asked college students and schoolchildren to self-report their anxiety. For both groups, reported anxiety across the body of research increased linearly over the time in question. The growth was substantial—almost a full standard deviation. “The birth cohort change in anxiety is so large that by the 1980s normal child samples were scoring higher than child psychiatric patients from the 1950s,” Twenge writes.3 What Twenge and other researchers found is that temporary historical events like wars and depressions have not meaningfully affected America’s long-term mental wellbeing. The Great Depression was an economic phenomenon, not a psychological one. Lasting trends, on the other hand, have really moved the needle. The sociocultural environment, for which birth cohort is a proxy, has grown increasingly anxiety-inducing. Along with a generally accepted air of mistrust, American kids and young adults endure an unprecedented level of day-to-day agitation.

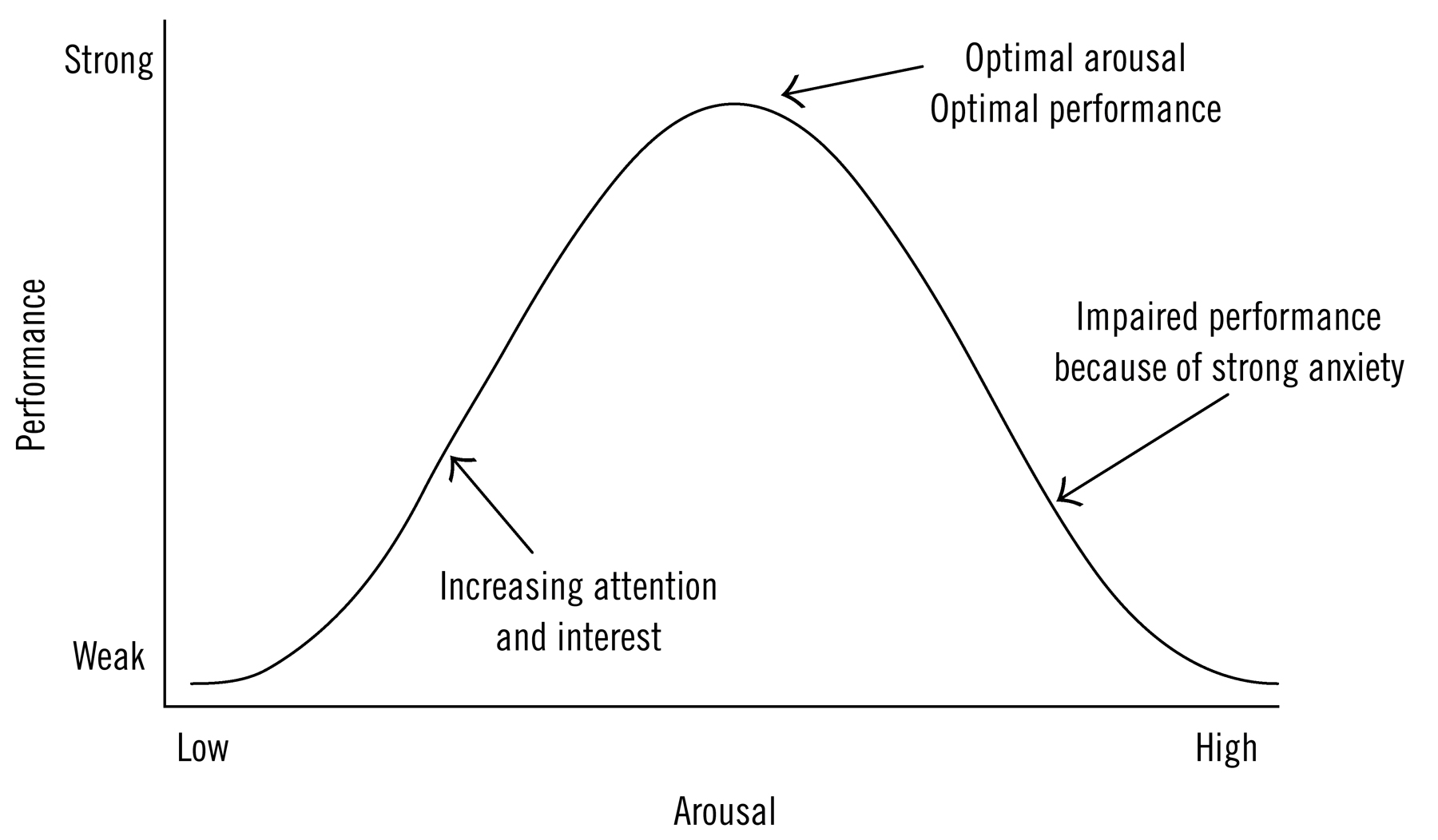

Given what we know about the recent changes in the American sociocultural environment, it would be a surprise if there weren’t elevated levels of anxiety among young people. Their lives center around production, competition, surveillance, and achievement in ways that were totally exceptional only a few decades ago. All this striving, all this trying to catch up and stay ahead—it simply has to have psychological consequences. The symptoms of anxiety aren’t just the unforeseen and unfortunate outcome of increased productivity and decreased labor costs; they’re useful. The Yerkes-Dodson law is a model developed by two psychologists (Robert Yerkes and John Dodson) that maps a relationship between arousal and task performance. As arousal heightens, so does performance, up to an inflection point when the arousal begins to overwhelm performance and scores decline. Our hypercompetitive society pushes children’s performance up, and their common level of anxiety with it. The kind of production required from kids requires attention, and lots of it. The environment aggressively selects at every level for kids who can maintain an optimum level of arousal and performance without going over the metaphorical (or literal) edge. It’s a risky game to play when you’re wagering a generation’s psychological health, and we can read the heavy costs in Twenge’s results.

Yerkes–Dodson Law

A model of the Yerkes-Dodson law at its simplest.

The dramatic psychological changes don’t stop at anxiety. The Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI) is one of the oldest and most elaborate personality tests, and one of its virtues is that its endurance allows for comparisons between birth cohorts. Twenge and her coauthors analyzed MMPI results for high school and college students between 1938 and 2007. They are blunt: “Over time, American culture has increasingly shifted toward an environment in which more and more young people experience poor mental health and psychopathology,” including worry, sadness, and dissatisfaction.4 We as a society are tending toward these pathological behaviors, and for good reason.

Restlessness, dissatisfaction, and instability (which Millennials report experiencing more than generations past) are negative ways of framing the flexibility and self-direction employers increasingly demand. Overactivity is exactly what the market rewards; the finance pros whom Kevin Roose studied who didn’t display hypomanic behavior also didn’t last long on top of the world. The best emotional laborers have a sensitivity to and awareness of other people’s feelings and motives that score paranoiac compared to past generations. Twenge spends a lot of energy criticizing narcissism among America’s young people, but a hypercompetitive sociocultural environment sets kids up to center themselves first, second, and third. All of these psychopathologies are the result of adaptive developments.

Our society runs headlong into an obvious contradiction when it tries to turn “high-achieving” into “normal.” The impossibility of the demand that people, on average, be better than average, doesn’t excuse any individual child’s average—or, God forbid!, subpar—performance. The gap between expectations and reality when it comes to the distribution of American life outcomes is anxiety-inducing, and it’s supposed to be. Anxiety is productive, up to a limit. But increased worker precarity means most firms are less incentivized to look out for the long-term stability of their human capital assets. It’s less expensive to run through workers who are at peak productivity and then drop them when they go over the edge than it is to keep employees at a psychologically sustainable level of arousal. This generation’s mental health is a predictable and necessary cost of the current relations of production, a cost that is being passed to young workers.

The link between anxiety and performance is strong, but other psychological maladies are tied to intensive production even more directly. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and sluggish cognitive tempo (SCT) are both increasingly diagnosed conditions that pose a danger to children’s ability to compete effectively. There’s some debate within the field of psychology as to whether these constitute two separate diagnoses, but they basically refer to two different ways of being distracted in class. A kid with SCT stares out the window, while one with ADHD squirms in his seat. It’s a simplification, but good enough for our limited purposes. They’re attention disorders—attention being the mental work that matters more and more in (automated) American production. Students who are unable to muster the necessary attention over time can be diagnosed with an attention disorder and given medication and certain testing allowances to improve their performance. Sure, a few students are probably gaming their doctor and faking ADHD to get extra time on their SAT—but the reality is that some kids are just better at sitting still and paying attention for long periods than others, and our culture has pathologized those who aren’t, because pathologies can be treated. Parents and teachers—the adults who traditionally spend the most time with children—both have good reasons to seek that treatment for low-attention kids, in order to turn them into high-attention kids. Their life outcomes might very well depend on it.

As the amount of attention required grows (more schoolwork, homework, studying, practice, etc., as in the time diaries in Chapter 1), more children will fall short. The number of American children treated for ADHD has grown significantly, from under one per hundred kids in 1987 to 3.4 in 19975 and from 4.8 percent in 2007 to 6.1 percent in 2011.6 Though the two studies used slightly different age ranges, the trend is abundantly clear to all observers. Between 1987 and 1997, the socioeconomic gap in diagnosis closed as the rate for low-income kids jumped; by the turn of the century, poorer children were more likely to be labeled attention disordered.7 In 1991, the Department of Education released a memorandum that clarified the conditions under which students with attention disorders were entitled to special education services, giving students who think they might fit the diagnostic criteria incentive to get certified by a medical professional.8

The most popular (on-label) medications for ADHD are stimulants like Adderall and Vyvanse, which chemically boost a user’s ability to concentrate and get to work. And with millions of children and young adults taking these pills, a thriving secondary market has sprung up among people who want to increase their performance without the medical formalities. One study of nonmedical use by college students found rates of up to 25 percent, with abuse concentrated among students with lower grades at academically competitive universities.9 The steady flow of drugs from legitimate prescriptions makes illicit use impossible to contain. Whatever the official justifications for distributing them into the environment, many young people—diagnosed and not—routinely use amphetamines to keep up in the race to accumulate human capital. It’s not for nothing they call it “speed.”

In the context of zero-tolerance school discipline, heavier law enforcement, and intensive parenting, increased medicalization of attention deficiency looks a lot like another form of youth control, a way to keep kids quiet, focused, and productive while adults move the goalposts down the field. Still, there’s not much an individual can do about it. Once again, we’re confronted with the conflict between what nearly everyone will recognize as a social problem (“Too many kids are being medicated to improve their academic performance”) and the very material considerations that weigh on any particular decision (“But my kid is having a really hard time focusing, and the PSAT is only a year away!”). This system demands too much of children—that must be clear by now—and if a pill can help them handle it better, with less day-to-day anguish, and maybe even push them toward better life outcomes, what parent or teacher could say no? A minority, as it turns out. Of American children currently diagnosed with ADHD, more than two-thirds receive medication.10

There are a lot of ways to think about the widening of these diagnoses and the prescriptions used to manage them. For an individual parent, it might very well be a question of helping a child cope with an overwhelming sociocultural environment. Teachers face all sorts of pressures when it comes to the performance of their students (recall the high-stakes testing that undergirds education reform), and guiding a disruptive pupil toward medication can make their lives a lot easier. Employers want employees loaded with human capital, with a superior ability to focus and a casual relationship to the need for sleep. How they get that way isn’t so much the boss’s concern. Kids themselves who take a long look at the world around them might well decide to ask for some pills—and then again, they might not have much of a choice. (Some students do a different calculation and start selling the “study aids” to their classmates.) Underneath all the concerned rhetoric about young people abusing medication, there’s no way to be sure that America can maintain the necessary level of production without it. And we’re not likely to find out. The economy runs on attention, and unending growth means we’re always in danger of running a deficit. In this environment, a pill that people believe can improve focus will never lack for buyers.

Given the psychological burden that Millennials bear compared to earlier generations, we can also expect an increase in depression. The competitive system is designed to turn everyone into potential losers; it generates low self-esteem like a refinery emits smoke. It’s very difficult to imagine that the changes in the American sociocultural environment have not led to more of the population suffering from depression. Sure enough, another Twenge-coauthored meta-analysis suggests that depression has increased 1,000 percent over the past century, with around half of that growth occurring since the late 1980s.11 If we’re counting costs, then a tenfold increase in depression is a huge one, with an emotional cost to our population that’s immeasurably bigger than the half-trillion dollars a year that New York Times reporter Catherine Rampell estimated depression costs the American economy.12 It’s another case of firms passing production costs to workers themselves, and depression has the added benefit of hiding social costs behind the veneer of individual psychosis or incapacity. But as Twenge reminds us, birth cohort is a proxy for changes in the social environment, and the increase in depression over time shows us that this is not a problem that emerges from the isolated turbulence of sick minds. These emotional costs are real, and Millennials bear them more than any generation of young people in memory.

6.2 Pills

Within the past few decades, the prevalence of these psychic maladies has grown fast, but not as fast as the use of medication. The refinement and popularization of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, or SSRIs (like Prozac), for depression, and stimulants such as methylphenidate (like Ritalin) for ADHD during the late 1980s and early-to-mid-1990s, changed the mainstream American relationship to pharmaceuticals, especially for young people. Average child brains were long considered too developmentally fragile for psychoactive medication, but by the mid-1990s even two-year-olds began popping pills. According to a 2000 article in JAMA, between 1991 and 1995 the number of preschoolers on antidepressants doubled, while the portion taking stimulants tripled.13 Teens saw similar increases: Between 1994 and 2001, American teens doubled both their antidepressant and stimulant prescription rates.14 But these numbers don’t reflect an increased national willingness to deal with young people’s mental distress. Over this period, the percentage of teen visits to the psychiatrist resulting in the prescription of a psychotropic drug increased ten times as much as visits overall.15 The portion of patients undergoing psychotherapy fell by over 10 percent between 1996 and 2005.16 In the aggregate, this looks a lot like what doctors call “drug-seeking behavior.”

As we would expect based on the increased reports of psychic distress, a growing number of young people know what the inside of a psychiatrist’s office looks like and how to manage their dosage. To get to this point required more than heavier academic schedules and the addition of special testing allowances for students with the right diagnoses—though both these things happened around the same time and probably helped. Pharmaceutical companies had to get the word out to people about better living through chemistry, and the population couldn’t be trusted to open the Yellow Pages to “P” without prompting. Bribing doctors could only go so far. Big Pharma decided to go right to the source: In 1981, Merck printed the first direct-to-consumer (DTC) prescription pharmaceutical advertisement.

By now the “Ask your doctor” refrain is written so deep in the American consciousness that it’s hard to believe the whole category is so young, but DTC advertising is a recent invention. In 1985, the Food and Drug Administration claimed jurisdiction over the regulation of DTC and applied the “fair balanced” standard—manufacturers would have to list all potential drawbacks in medication ads, which made radio and TV spots that satisfied the regulation so long they were unaffordable. But over time, the FDA relaxed their position, and in 1997 they began allowing advertisers to direct viewers to an 800 number or a website for the full list of risks.17 DTC advertising boomed, from $12 million in 1980 to a peak of over $5 billion by 2006. (Recall that the whole music recording industry is now worth an annual $7 billion.)18 Pharmaceutical companies were whispering right in the population’s ear; DTC is now “the most prominent type of health communication that the public encounters.”19

It’s impossible to tease apart the causes of elevated psychotropic medication among American young people: They’re undeniably facing more mental pressure than their elders; they have better medications available; more attention and participation are required of them; intensive parenting promotes frequent intervention in child development; and there’s a whole new multibillion-dollar industry dedicated to telling them they might be better off with a prescription. But we can draw correlations between changes in the American sociocultural environment over the past few decades and the mass drugging of children. This trend isn’t a system error, it’s an attempted solution to a series of problems with young people who are alive right now. Youth psychology became a Goldilocks question, with “just right” lying between depression and ADHD. For everything else, there are antidepressants and stimulants—and who can blame any individual for trying to stay happy, sane, or eligible for success by any means available?

These medications don’t always have the desired effects, but despite the increased levels of mental distress, the teen suicide rate has stayed just about flat, while there’s been some growth in the young adult rate.20 It’s a relief that child and young adult suicide hasn’t skyrocketed along with psychological health problems, but this nothing tells us something. That there hasn’t been a sharp decrease in suicides suggests that our aggressive medication regimen is not just an instance of science providing answers or a new awareness of an old problem. If we were dealing with the same amount of depression (with more diagnoses and medication), we’d expect these higher levels of treatment to have an impact on suicide. Instead, it appears that all this medication has at best merely contained suicides at their past level, getting enough young people from one day to the next despite their greater mental duress.

Though once again there’s no way to isolate cause and effect, based on the context already established, it looks like hypermedication is designed to solve new problems. It’s not hard to draw the line between increased baseline adolescent mental distress, the popularization of psychoactive meds as a part of child-rearing, and higher required levels of productivity; they constitute a cluster of recent social phenomena, a constellation in the shape of a generation. If the goal has been to develop a birth cohort able to withstand the pressures of twenty-first-century production, America has succeeded. We don’t have to like it, we just have to do it. When it comes to social media, however, we mostly do like it.

6.3 Social Media

When mainstream American commentators talk about the changes that have produced the Millennial psychosocial environment, they like to use a metonym: social media. “Twitter Is for Narcissists, Facebook Is for Egotists”;21 “Selfies, Facebook, and Narcissism: What’s the Link?”;22 “Is Facebook Making Us Lonely?”23 This is in part because content about social media tends to get shared on the platforms it references, making it successful and replicable according to site analytics, but the practice isn’t totally off the mark. One of the major differences between Americans now and Americans thirty or forty years ago is the proportion of our interactions mediated by algorithms and scored by metrics.

As a way to rationalize interactions, social media capitalizes on and further develops young people’s ability to communicate. These platforms flatten the distinctions among individuals, companies, and brands, and allow users of all sorts to measure the resonance of their every message. Social media is a good example of a lot of Millennial phenomena at the same time, but there’s a danger in framing it as the source. Facebook can give us a lot of insight about young Americans, but it’s only a superficial cause of behavior. Before I get into how these Internet technologies affect the Millennial character, I think it’s important to look at how they affect the Millennial situation. That is, how they relate to what I’ve discussed in previous chapters on shifts in workforce dynamics.

From Friendster to Myspace to Facebook to Twitter, or so the social networking story goes, firms have found new ways to connect person-shaped nodes and turn those connections into large piles of investment capital and sometimes ad revenue. Users put together a personal patchwork of hardware and software, year by year getting more fluid at creating and sharing. In relation to social media, everything from photographs to videos to writing to ads becomes content. For professional and amateur creators, there’s so much potential attention, and the rewards for securing a slice seem so large, that opting out of social media is like hiding away in an attic. You just can’t compete that way. For this cohort of young Americans, social media is hard to separate from sociality in general, and opting out is a deviant lifestyle choice. Followers and fans used to be for cult leaders and movie stars, but social media platforms have given everyone the ability to track how much attention is being paid to each of us. Instead of just consumers, the default settings make Americans (and Millennials in particular) producers in the attention economy.

As we saw in the last chapter with YouTube and SoundCloud, social media has upsides and downsides for users at all levels. Every platform has its success stories, each producing its own handful of expert users and cross-platform stars. The best example of an app creating its own genre isn’t YouTube, it’s Vine. The Twitter offshoot allowed users to record six-second looping videos with sound, and some young performers amassed millions of followers, the kind of fan base that sets you up to make actual money. The top Viners formed a sort of labor cartel, promoting each other’s work on their channels, talking to each other about their working conditions, and even living together. In the fall of 2015, as they saw other platforms developing more attractive deals for creators, they went to Vine with an offer:

If Vine would pay all 18 of them $1.2 million each, roll out several product changes and open up a more direct line of communication, everyone in the room would agree to produce 12 pieces of monthly original content for the app, or three vines per week.

If Vine agreed, they could theoretically generate billions of views and boost engagement on a starving app. If they said no, all the top stars on the platform would walk.24

The company balked: They weren’t the boss of these workers, they were a platform for these creators. The young workers withdrew en masse, some going to YouTube, others to Snapchat or Instagram. A year later, stagnated, Vine was toast. This was a rare case when creative Internet labor was organized enough and held enough leverage to negotiate collectively, but the important lesson from the story is that platforms would rather disappear entirely than start collective bargaining with talent. Which is too bad, because Vines were cool and now no one can make them—though other companies have of course replicated many of Vine’s functions.

Young people’s creativity is a mine for finance capital, and social media companies (usually built and maintained by young people) are the excavation tools. Precisely targeted advertisements refine the raw attention into money. From this perspective, technology firms are motivated to maximize user engagement, regardless of its impact on their lifestyle. Whether you’re a beginner comedian, athlete, novelist, photographer, actor, sex worker, marketer, musician, model, jewelry maker, artist, designer, landlord, inventor, stylist, curator, filmmaker, philosopher, journalist, magician, coder, statistician, policy analyst, or video gamer, there are universally accessible and professionally legitimate platforms where you can perform, distribute, and promote your work. This may not increase the number of people who can make a living doing any of these things, or the quality of their lives. It may not mean that more or better people can see their dreams realized. But it is a way for investors to profit off even the worst rappers and the weakest party promoters. The situation also raises the baseline hustle required for most people to succeed in any of these pursuits. At the very least you need to maintain a brand, and to do that you probably need to create social media content on someone else’s platform. As a symbiotic relationship between different holders of investment capital, social media is a great low-cost way to generate, corral, measure, and monetize the attention we pay each other as we go about our affairs.

Social media seeks to integrate users of all ages, but young Americans are better suited for most platforms. With the exception of the professional résumé site LinkedIn, a 2017 Pew survey found that younger adults were more likely to use all examined social networks. That reflects a wider overall rate of Internet usage among young people: Pew only surveyed Americans over eighteen, but 99 percent of those under thirty use the Web—compared to 64 percent of seniors.25 In an earlier report, Pew included teens. What they found is that over the past decade teens have consistently used the Internet more than other birth cohorts, and young adults have only caught up as Internet-using teens born in the late 1980s aged into the older demographic. (Although the bounds on the Millennial cohort aren’t yet well defined, social media use from childhood may be what separates us from Generation Z, or whatever we end up calling the next one.)

The “digital divide” between privileged young people with computer access and underprivileged ones without seems to be closing: Pew’s survey found weak or no correlation between teen computer and smartphone ownership and parental income. Among the surveyed group, 80 percent have their own computer and another 13 percent have a common computer they use at home. Of rural teens, 99 percent of the Pew group had regular online access—including 79 percent on their mobile device.26 I expect that in the near future the statistically closable gaps in American teen Internet use will indeed close. Not everyone can access the Web, but a greater proportion of teens can log on than American adults can read a book.27

Just because rich and poor teens are using the Facebook app at similar rates doesn’t mean they’re using the same data plans. But the really successful platforms are within reach for a large majority of young Americans, so the rich kids of Instagram are an exception, not the rule. The real money is in the feelings, thoughts, ambitions, work, and attention of large numbers of people—preferably everyone. If only the privileged can use an app, it’s a niche service with a shrinking niche. Even editorial publications like Gawker and BuzzFeed have sought to become platforms where users can create content instead of just viewing and sharing it. The platform Medium has so muddled the distinction between paid writing and unpaid blogging that even I can’t tell the difference half the time. From the perspective of decreasing labor costs, it’s a no-brainer: A page view earned by user-created content costs less to produce than a click on employee-created content. With a large enough user base willing to upload or publish their work for free, it’s cheaper to host than to employ—even as these conditions drive down worker compensation and drive up productivity.

The Internet-enabled market tends toward this vicious, profitable cycle. A firm that can bring an aspect of social life online and speed it up—taking a Lyft, ordering takeout on GrubHub, planning an event on Facebook, finding a date on Tinder, annotating rap lyrics on Genius, recommending a restaurant on Yelp, renting an Airbnb apartment, etc.—stands to profit as a middleman, as a harvester of attention and data for advertisers, or just from demonstrated potential to do so in the future. Social media theorist Rob Horning’s comments on the so-called sharing economy (where sites network and rationalize users’ haves and wants, so you can rent your neighbor’s chain saw, for instance, instead of buying one yourself) apply more broadly:

The sharing economy’s rise is a reflection of capitalism’s need to find new profit opportunities in aspects of social life once shielded from the market, in leisure time once withdrawn from waged labor, in spaces and affective resources once withheld from becoming a kind of capital. What sharing companies and apps chiefly do is invite us to turn more of our lives into capital and more of our time into casual labor, thereby extending capitalism’s reach and further entrenching the market as the most appropriate, efficient, and beneficial way to mediate interaction between individuals. For the sharing economy, market relations are the only social relations.28

Capitalism has always rewarded those who have found ways to monetize new life processes, but technology combined with the growth of the finance sector has accelerated this process. The Internet and social media are three-way relations among people, corporations, and technology, and they represent a major advance in the efficient organization of communication and productivity. It’s clear by now that, as far as most people are concerned, in terms of the total changes in their life circumstance, this is not a fortunate thing to have happen while you’re alive. Netflix is great, but it doesn’t make up for labor’s declining share of national production.

Proponents call the process by which investors remake activities in their own image of rationalized efficiency “disruption.” The moniker lends an evolutionary sheen to the network that links every Uber and Airbnb from Silicon Valley to New York City, but disruption in this context implies a contained reorganization that follows. Tech profiteers believe the same social instability that enables their rise will settle just in time for them to get comfortable on top. It’s possible they’re right, but a stable “disrupted” America means further developing the tendencies we’ve seen in the past chapters: more polarization and inequality, declining worker compensation, increased competition, deunionization, heavier anxiety, less sleep, wider surveillance, and lots of pills and cops to keep everything manageable. This helps explain why Facebook designed and funded an entire police substation for Menlo Park, California, where the company’s headquarters are located. “It’s very untraditional, but I think it’s the way of the future,” Police Chief Bob Jonsen told the San Francisco Examiner.29

Of course, if using apps just made you feel isolated, broke, and anxious, fewer people would probably use them. Instead, all of these technologies promise (and often deliver) connectivity, efficiency, convenience, productivity, and joy to individual users, even though most of the realized financial gains will accrue to a small ownership class. The generalized adoption of these technologies helps bosses grow their slice of the pie, but that doesn’t necessarily make using them any less irresistible for the rest of us. Coke tastes good even once you’ve seen what it can do to a rusty nail. Why do untrusting young Americans continue to download apps made by companies that they realize on some level are watching, tracking, and exploiting them?

Researcher danah boyd took up this question in her 2014 book It’s Complicated: The Social Lives of Networked Teens. With a title taken from the most nuanced option in Facebook’s drop-down menu for relationship status, the book contains boyd’s qualitative research into the way a varied cross section of American young people uses social networking platforms. When she asked teens why they use social media, boyd heard that “they would far rather meet up in person, but the hectic and heavily scheduled nature of their day-to-day lives, their lack of physical mobility, and the fears of their parents have made such face-to-face interactions increasingly impossible.”30 Asking why teens use Facebook is a lot like asking why teens like talking to each other. “The success of social media must be understood partly in relation to this shrinking social landscape,” boyd writes.31 Driven from public spaces like parks and malls, teens have found refuge online, where their flirting, fighting, and friending can be monitored and sold to investors and advertisers.

The links between using an app and kids being forced out of public space may seem tenuous and theoretical, but once in a while we see them crystallized in an instant, as happened a few years ago in the heart of gentrifying Silicon Valley, San Francisco’s Mission District. The previous home of Mexican immigrants, white flight, punk venues, and Central American refugees, the Mission has seen its character change with the influx of young tech workers. A private infrastructure has sprung up to accommodate them, spurring landlords and developers to drive the current population out with evictions and rent hikes. As part of this process, the local government contracted the management of a pickup soccer field to a group called San Francisco Pickup Soccer, a front for the national for-profit ZogSports. A “social sports league for young professionals,” ZogSports organizes fee-based team play in advance—these games aren’t “pickup” in any sense of the word. (Recall the discussion in Chapter 5 of the increasing organization of amateur sports.) The city contracted the field out Tuesdays and Thursdays between 7 and 9 p.m. to ZogSports in what Connie Chan, deputy policy director for the parks department, told the blog MissionLocal was “an experiment with new mobile app technology.”32 This tech advance in amateur sports facility management is a boon for the area’s corporate activities coordinators, but not so much for the kids who want to play some soccer.

In September of 2014, a cell phone video surfaced33 of a corporate team from Dropbox attempting to remove a bunch of local kids in time for their scheduled 7 p.m. game with Airbnb. The city’s new policy conflicts with the field’s own informal rules (seven-on-seven, winner stays), but the uniformed Dropbox team has their reservation in order and is unconcerned with the codes they’re disrupting. In the video, you can hear a kid responding to one of the impatient players threatening to call the cops. After their game, odds are those kids headed off to do something more productive, whether it was homework, joining an organized sports team, or even sending a friend the link to a Dropbox full of movies. I’m willing to bet not one of those kids would trade their cell phone for another hour on the pitch—nor should they have to in order to feel legitimately aggrieved—but the totality of these technosocial changes corners children into behavior that companies can use.

The trends all stitch together—even the Dropbox employees are still with their coworkers (at least some of whom are clearly dicks) at 7 p.m. when they could be playing an actual pickup game with their friends and otherwise building social ties that aren’t related to their productivity. In her book The Boy Kings, former Facebook employee Kate Losse described what it was like working in the early days for the company that would have such a large effect on the way so many other people would work in the near future. “Looking like you are playing, even when you are working, was a key part of the aesthetic, a way for Facebook to differentiate itself from the companies it wants to divert young employees from and a way to make everything seem, always, like a game.”34 Play is work and work is play in the world of social media, from the workers to the users.

Employees reflect on their employer’s brand, and playing pickup soccer is great branding, especially if you can beat Airbnb. “Looking cool, rich, and well-liked was actually our job,” Losse writes, “and that job took a lot of work.”35 Nice work if you can get it, as my mom used to say, but it’s work still. Losse enjoys parts of the camaraderie, the free trips, the in-team flirting, but even the party-working takes more out of employees than it gives back. “At Facebook, to repurpose the old feminist saying, the personal was professional: You were neither expected nor allowed to leave your personal life at the door.”36 Millennials have grown up with this vision of an integrated work life as aspirational, and not because we’re easily distracted by ostensibly free yogurt. (Or not just because.) If a Millennial does well enough to end up on the right side of job polarization, there’s a good chance that their employers are willing to offer some low-cost incentives to keep them working late. Access to the office snack cabinet is an index of a worker’s value in the labor market, if not of their job security. Social media means we all could be working all the time, but the people who design the platforms get perks.

The people who populate the platforms with amateur content, however, can’t expect to get free yogurt, or gym memberships, or wages, even though their quality content makes the difference between a moribund site and a vibrant one. Some older adults get very excited when they start to see just how vast and diverse the ocean of user-generated content truly is. The experience can be dizzying. In their book Born Digital: How Children Grow Up in a Digital Age, John Palfrey and Urs Gasser are psyched to discover that kids are putting thought into their actions. “Many young users are digital ‘creators’ every day of their lives,” they enthuse. “When they write updates in a social media environment or post selfies, they are creating something that many of their friends will see later that day….Sometimes young people even create entirely new genres of content—such as ‘memes.’…Although memes might look silly or seem irrelevant from an adult perspective, they are nevertheless creative expressions that can be seen as a form of civic participation.”37 Their tone is adorable, but also a bit quaint. The medium is not the totality of the message, a lesson I hope we all learned when Nazi frog memes played a noticeable role in the 2016 presidential election.

Networking platforms are an important part of both contemporary American profit-seeking and child development; it’s like investors built water wheels on the stream of youth sociality. Through social networking interaction, kids learn the practice of what political theorist Jodi Dean calls “communicative capitalism”: how to navigate the “intensive and extensive networks of enjoyment, production, and surveillance.”38 Dean writes that this education—and even attempts to resist it from the inside—ultimately serves to “enrich the few as it placates and diverts the many.”39 For all the talk about the crowd and the grassroots and the Internet age of access, for all the potentials of open source and the garage-to-mansion Internet success stories, increased inequality and exploitation have come hand in hand with these technological developments. Not only are many of young Americans’ interactions filtered through algorithms engineered to maximize profits, the younger “digital native” Millennials have never known anything different. They have always been online, and their social world has always been actively mediated by corporations.

Social networking doesn’t exist in a world apart; the inequalities that structure American society show up in new ways online. In It’s Complicated, danah boyd describes how adult authorities use social networking as an investigative tool for their aggressive disciplinary apparatuses. Social media use is broadly popular, but it’s still concentrated among the young and black, the same group targeted by the police and courts.40 Intensive parenting—a practice more common among the upper classes—also encourages the strict surveillance of children’s Internet use; some parents even require kids to hand over their account passwords. Whether it’s by the state, their corporate hosts, or Mom and Dad, “teens assume that they are being watched,” boyd concludes.41 To adapt, young Americans have developed a host of countersurveillance techniques; boyd talked to one teen who deletes her Facebook page every day so adults can’t watch her, then resurrects it at night when the observers are off the clock.42 But even resistance like this is work that prepares young people for their future employment. Finding a way to use the Internet with a compelling personal flair but without incriminating or embarrassing yourself is an increasingly important job skill, and an even more important job-seeking skill.

6.4 Good Habits

Millennials are highly sensitized to the way our behavior is observed, both by our peers and by adult authorities. We’ve learned to self-monitor and watch each other, to erase, save, or create evidence depending on the situation’s particular demands. Contemporary childhood prepares kids to think like the adults tracking us, and then to try to think a step further. And yet, despite all the surveillance and countermeasures, young Americans have less illicit behavior to hide in the first place. When it comes to sex, most illegal drugs, and crime, Millennials are significantly better-behaved than earlier birth cohorts. Moral panics about youth behavior are a historical constant, but now they are especially unmoored from reality.

With all the increased stress and anxiety, combined with the normalized use of prescribed pharmaceuticals, a reasonable observer might think Millennials are set up for elevated rates of substance abuse. At first glance, the numbers suggest this is the case: Lifetime illicit drug use among high schoolers is up, after a long and precipitous decline between 1980 and the early 1990s. But not all illegal drugs are created equal: When you factor out marijuana (the most popular and least harmful of controlled substances), there’s a different picture: Teen drug use excepting weed has continued to decline since the 1990s, pushing historical lows.

The Monitoring the Future project at the University of Michigan’s Institute for Social Research has kept detailed track of teen substance use since the beginnings of the War on Drugs in the mid-1970s. Their studies survey teens about four categories for a battery of substances: use, perceived risk, disapproval, and availability. From the late 1970s to the early 1990s, marijuana use declined, while perceived risk and disapproval increased.43 But in the decades since, an opposing normalization trend has erased those earlier changes, putting teen pot-smoking attitudes and behavior back where they were in the mid-1970s. Since 2012, most tenth and twelfth graders no longer see “great risk” in regular use. National polling data suggests teens are ahead of the policy curve when it comes to liberalizing ideas about weed: Over four decades of national polling on marijuana legalization, Gallup’s data shows a clear trend toward favoring, from merely 12 percent in 1969 to 58 percent by 2013.44 In 2012, Colorado and Washington became the first states to legalize personal use in spite of the federal government’s ongoing prohibition. In 2015, Alaska and Oregon joined them; in 2016 it was California, Nevada, Maine, and Massachusetts. If the trend continues, today’s grade schoolers may have to learn from a textbook about how marijuana used to be banned.

As localities relax the restrictions on marijuana use—whether through legalization, decriminalization, or medical provisions—even getting high is getting more efficient. Handheld vaporizers are now a luxury toy for rich Baby Boomers, and years of conscious breeding means weed with a higher average psychoactive content. But smoking and vaporizing plant matter is too inefficient for the current economy; in recent years, the popularization of THC extraction techniques and oil vaporizers has moved marijuana concentrates into the mainstream. And since concentrates can be made out of unsellable plant detritus, processing can turn trash to profit. The market endeavors to provide a nice high on demand with minimal muss and fuss. On the one hand, concentrates appeal to time-pressed teens who are constantly under surveillance and subject to zero-tolerance discipline policies. On the other, these conditions (along with new stoner technology) have turned the communal counterculture ritual of smoking a joint into something closer to medicating with a USB-charging inhaler. It appears that marijuana use—among teens as well as adults—will continue to increase, but as it gets more efficient and scalable, it may not look much like it did in the 1970s. Mainstream magazines have already started running features like “How to Be a Productive Stoner” and “The Productivity Secrets of Wildly Successful Stoners.” A few office workers are taking microdoses of LSD on the job for creative enhancement.45 Does it still count as recreational drug use if you’re doing it to work harder?

Aside from marijuana, American teens use controlled substances less than past generations. Among twelfth graders, binge drinking is down by nearly half over the past forty years, as is cigarette smoking. Use of harder illegal drugs like cocaine, meth, LSD, and heroin is down too.46 No one has a perfect causal analysis, but increased surveillance, heavier penalties, and a lack of public space most likely contribute to the decline, as has the flow of legal (and black-market) pharmaceuticals. (Based on the evidence, however, antidrug propaganda programs like D.A.R.E. don’t seem to have been effective.)47 It might surprise readers to hear that teen heroin use is down, given that we’re in the midst of a national opiate crisis, but it’s true. Teens were the only age group whose rate of heroin use declined between 2002 and 2013, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), while everyone else saw huge increases.48 Americans are used to thinking about the correlation of recreational drug use and youth (which continues to exist), but we also need to look at the birth cohort effects.

Growing up in expanding postwar America, Baby Boomers (born between 1946 and 1964) crafted the mold for how following generations have imagined “youth,” and many of our media stereotypes about teens and young adults flow from the Boomer experience. This is no surprise given the age cohort that owns and manages media companies. But Boomers are their own special group of Americans, with their own predilections. The Wall Street Journal broke down the numbers on accidental drug overdoses over time by age and didn’t find a consistent pattern: In the early 1970s, fifteen-to-twenty-four-year-olds overdosed most, then it was young and middle-aged adults, and now the forty-five-to-sixty-four-year-olds have taken over.49 It didn’t make much sense, until they looked at how the Boomer cohort traveled through those numbers.

Birth cohort is a better explanatory variable for accidental drug overdoses than age, which is to say that it’s not that young people like drugs, it’s that Boomers—whether seventeen or seventy—have tended to use drugs more than other cohorts. The overdose rate for the fifty-five-to-seventy-four cohort quintupled between 2001 and 2013 as Boomers aged into that range. Experts concluded that the spike in elderly drug abuse is due to “the confluence of two key factors: a generation with a predilection for mind-altering substances growing older in an era of widespread opioid painkiller abuse.”50 Drug overdoses are no longer a youth phenomenon. Millennials are suffering from the overprescription of drugs (including pain pills), but we aren’t the Oxy generation.

Why are Millennials so comparatively sober? Given the historically high stakes for their choices, given how much work they’ve put into accumulating human capital, perhaps today’s young people are more conservative when it comes to taking chances with their brain chemistry. Whatever the reasons, survey data indicates that Millennials were the first wave in a trend of American teens assessing the risks and just saying no at a higher rate than their predecessors.

Drugs aren’t the only vice that American teens are declining with increasing frequency. Don’t believe what you hear about “hookup culture”; kids are having less sex than they have at any time since the sexual revolution. An article in the journal Pediatrics (“Sexual Initiation, Contraceptive Use, and Pregnancy Among Young Adolescents”) looked at when young people first have sex based on their birth year. Between 1939 and 1979, an individual was more likely in general to have sex at a younger age than one born the year before.51 The median age of sexual initiation dropped from nineteen to seventeen during the forty years, while the age at which the youngest 10 percent had sex shrank similarly from just under sixteen to just over fourteen. American teen depravity hit its inflection point in the early 1990s. In just over a decade, the median age of first sexual contact was almost back up to eighteen. According to CDC’s Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) of high schoolers, the average teen now graduates a virgin, a landmark shift that occurred between 1995 and 1997.52

As teens are waiting longer to have sex, they’re also more responsible once they decide to do it. The Guttmacher Institute—the foremost research think tank when it comes to family planning and reproductive health—found that the number of teens using contraceptives when they first have sex has increased markedly, from under half in 1982 to just under 80 percent by 2011–2013.53 The teenage birthrate and abortion rate are both down as a result.54 As with drug use, there’s no way to isolate a single cause for elevated rates of teen abstinence. One thing we can rule out is religiosity; Millennials report less faith—both belief and worship—than other American age cohorts.55 If Millennials are more risk-averse than past generations, then they might be less willing to roll the dice when it comes to an unplanned pregnancy or sexually transmitted infection, but they seem to have found a way to mitigate these risks with contraception. Perhaps increased anxiety and depression means decreased teen libidos, or maybe it’s a side effect of the medication. A decline in unsupervised free time probably contributes a lot. At a basic level, sex at its best is unstructured play with friends, a category of experience that the time diaries in Chapter 1 tell us has been decreasing for American adolescents. It takes idle hands to get past first base, and today’s kids have a lot to do.

Another contributing cause to the decline of adolescent sexual initiation is a decline in sexual assault and abuse perpetrated against children. A 2006 meta-analysis in the Journal of Social Issues mapped out the reduction in maltreatment on a number of different surveys, and though the authors have trouble finding a cause, crimes against children had fallen significantly since the early 1990s.56 On the National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System measure, the physical and sexual abuse rate had fallen by more than half between 1992 and 2010.57 Juvenile (ages twelve to seventeen) victimization (on the National Crime Victimization Survey) is down across the board, with the (reported) sexual assault of teens down by over two-thirds during the last twenty years.58 On the YRBS, the percentage of high schoolers reporting sex before age thirteen (nearly synonymous with abuse) dropped from 10.2 percent in 1991 to 5.6 percent in 2013.59

Though there is good reason to believe that these statistics vastly undercount the real rate of sexual assault, these numbers force a reevaluation of the data on teen sexuality, and a confrontation with the hard reality that a significant percentage of early sexual contact is unwanted.60 The sexual revolution’s claim was that with more control over their bodies, young people would be free to explore their sexuality. The stigmas about teen sexuality continue to fall, but more sexual freedom—especially for young women—now correlates with less sex and fewer partners. It’s impossible to extricate the trend from confounding variables like declining free time, and with the reporting rates for rape so low, the federal studies are only measuring the tip of an iceberg, but perhaps the longstanding stereotype of teens as sexually obsessed isn’t as true as American Pie would have us believe. Maybe given the autonomy to choose, more teens are choosing to wait.

That teens are waiting longer to have sex and have fewer partners on average hasn’t stopped adults from panicking. The country’s nervous parents have focused their anxiety on a relatively new sexual practice: sexting. Armed with camera phones, it’s no surprise that teens have started sending each other naked pics, but what to them is a normal sexual practice sounds like self-produced child porn to adults. The best research into actual teen sexting behaviors comes from teams led by Jeff Temple, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Texas. In 2012, a team of his interviewed 948 diverse public high school students in southeast Texas about their sexting activity and found a high rate of sexting, with 28 percent reporting having sent a sext and 31 percent reporting having asked for one.61

I expect that the rates will increase as camera phones are more universally adopted and app builders like Snap attempt to mitigate the risks of sexting on the technology side, but it’s already a mainstream practice. A second study from a Temple-led Texas team looked at the longitudinal association between sexting and sexual behavior and found no connection between sexting and “high-risk” practices (unprotected sex, multiple partners, alcohol and drug use before sex), suggesting that sexting isn’t just for “bad” kids.62 Instead, the study confirmed that some kids were sexting before having sex, reversing the older generation’s relationship with self-produced nudes. No wonder adults are so confused. Still, the biggest correlate in Temple’s studies was between sexting and an ongoing sexual relationship. When Palfrey and Gasser write in Born Digital (from a self-described adult perspective) of teen sexting, “Rarely do these stories end well,” they are flatly incorrect.63

6.5 Porn

Maybe the adults protest too much. Though the stats indicate that fewer children are being sexually abused by adults, that doesn’t mean adults have stopped sexualizing young men and especially women. It’s mostly adults who are profiting from hypersexualized teen performers. The fashion industry, which is always hustling to stay ahead of the sexy curve, remains fixated on youth and starts the average model working before she turns seventeen.64 Millions of Internet pornography sites make billions in annual domestic revenue, disproportionately off actors pretending to be kids. As part of a collaboration with BuzzFeed, the site Pornhub looked into its metrics and found that “teen” was both the most popular category and search term for male users.65 “Teen” refers in a strict sense mostly to minors, and the industry term “barely legal” harkens back to Chris Rock’s joke about the minimum wage: If they could sell pornographic movies of sixteen-year-olds, they would, but it’s illegal. At the intersection of youth, sex, and technology there’s a lot of adult anxiety, but there’s also a lot of adult profit.

Millennials have grown up in a post–sexual revolution American culture, where Playboy yielded to shinier and more mainstream Maxim, until both were crushed by Internet porn. For past generations the Playboy brand stood in part for the stolen copies hidden under teenage beds; now the magazine can hardly decide whether to even bother with nudity. There is no newsstand operator as easy to sneak by as the online “Don’t go to this site if you’re not 18” pop-up “barriers.” It’s hard to get solid data on young people viewing online pornography, in part because it’s technically against the law. Porn sites can’t exactly tell researchers what percentage of their users they believe to be underage, though as proprietors they have the most reliable ways of tracking their own user demographics. With that caveat, the data we do have suggests that most kids looking at porn on the Internet are over fourteen; the epidemic of sex-crazed ten-year-olds hasn’t materialized.66 Still, most teens have probably looked. Have they suffered from it? The results from a longitudinal study of teens age thirteen to seventeen and online sexual behavior suggest not:

In general, youth who reported participation in online sexual activities were no better or worse off than those who did not report online sexual activities in terms of sexual health outcomes. Specifically, there were no differences in their rated trust for health care professionals, approach to health care, regular use of health care providers, pregnancy knowledge, STI knowledge, condom and contraception consistency, and fears of STIs. They had comparable levels of communication about sex with their parents and with their sex partners. They also were comparable in terms of levels of self-esteem and self-efficacy, as well as body image and weight management efforts. There were also no differences between the two groups in their feelings about school, their ability to get along with parents and peers in school, or performance in school. They had similar levels of ratings of the importance of finishing high school, going to college or university, and getting a good job.67

Considering the understandable fears about every kid with an Internet connection having easy access to a lot more explicit sexual content than existed in the world a generation ago, that is a whole lot of nothing when it comes to damage. This is only one study, and who knows how virtual reality will change the landscape, but Millennials do not seem to have been irredeemably malformed by the proliferation of online porn, as some commentators have long prophesied. Though it has most likely affected some sexual norms, so did Playboy.

On the production end, however, pornography has followed some of the same labor trends we’ve seen throughout the book. Even in an industry where performers can’t legally get started until they hit eighteen, amateurs have supplanted the professionals. The most popular places to see porn are so-called tube sites, as in YouTube. Users upload clips, whether self-produced or pirated. It’s like the music industry, but more intense. Professionals have to compete for attention against every exhibitionist with a video camera, and we’ve seen what kind of effect that dynamic has on wages. In a piece for The New Yorker, Katrina Forrester describes how the industry has changed:

Much online porn is amateur and unregulated. It’s hard to tell how much, because there’s little data, and even larger studios now ape the amateur aesthetic, but applications for porn-shoot permits in Los Angeles County reportedly fell by ninety-five per cent between 2012 and 2015. Now most films have low production values, and they are often unscripted. Sometimes you can hear the director’s voice; apparently, many viewers can make do without the old fictional tropes of doctors and nurses, schoolgirls, and so on—the porn industry itself having become the locus of fantasy. Where performers like [Jenna] Jameson had multi-film contracts with studios like Wicked or Vivid Entertainment, such deals are now rare, and most performers are independent contractors who get paid per sex act.68

Increased competition leads to low-cost, rationalized labor; Millennials know the deal. Increased competition also means profit for someone, and the someone when it comes to porn is a company called MindGeek. “RedTube,” “YouPorn,” and “Pornhub” sound like competing sites that do the same thing, but that’s only half right. All three are owned by MindGeek, which, starting in 2006, began acquiring as many porn networks and production studios as it could get its weird-name-having hands on. MindGeek produces the professional media (that is, the stuff that isn’t genuinely user-generated) under one set of labels, and soaks up the ad revenue from pro and amateur content alike by running ads on the tube sites. Slate’s David Auerbach described the situation as being as if “Warner Brothers also owned the Pirate Bay.”69 It’s a no-lose proposition for management, and a no-win one for labor. Sound familiar?