In many ways, neurotheology begins with the human brain. Not just because the word itself starts with “neuro,” but because the brain is that part of ourselves that allows us to have all our thoughts, feelings, and experiences, including those related to our religious and spiritual selves. But there is arguably a great contrast between the reality described by science and the one painted by religion, or even between the reality of conscious experience and its scientific descriptions. Which one represents the true reality is perhaps a question for the ages, especially in the third millennium. So, one of the most fundamental questions is, how far can we go in our understanding of reality if we begin our search for truth from a neuroscientific, or brain-related, perspective? For example, if we say that a certain sensory area of our brain is activated when we eat a piece of chocolate, does that tell us that the chocolate actually exists in the external world? Does it mean that our brain actually created the chocolate itself? Or does it mean that the brain simply created our experience of what chocolate tastes like? But does chocolate actually have taste, or does it have taste only when it interacts with the brain? In a similar way, each of these questions can be posed with regard to religious and spiritual beliefs and experiences and their relationship with the brain—a field we now refer to as neurotheology.

Along these lines, one of my favorite stories relating to my own research came as the result of one of my laboratory’s first studies using brain imaging to explore changes that occur in the brain during practices like meditation and prayer. We were able to bring several Franciscan nuns into our lab to study their brains during the performance of a prayer practice called centering prayer. Centering prayer involves focusing the mind on a specific phrase from the Bible or on a particular prayer. The person does not repeat the phrase or prayer over and over, but rather engages an extensive and contemplative reflection on the prayer or phrase. As this contemplation occurred in our lab, the nuns began to fall into a progressively deeper meditative state. At its peak, centering prayer can help a practitioner feel as if she is deeply connected to God.

When the first nun came into our lab to be studied, we scanned her brain initially at rest and then again while she was doing the centering prayer practice. After her participation in the study was over, I brought her over to the computer and showed her the two scans so that she could understand a little bit more the work that we were doing and what neurotheology was all about. I showed her the two scans side by side on the computer screen using a variety of colors to reflect which areas of the brain had been activated or deactivated during the centering prayer. When I showed her that there were a variety of changes that occurred in her brain during the practice, she was very excited. She told me how meaningful it was to see these changes going on in her brain because these results supported her belief in the importance of this prayer as an essential component of her religious and spiritual life. This prayer, which was deeply meaningful to her, was something that she also felt within her own mind and body. She acknowledged that the scan findings actually supported her religious and spiritual beliefs, including her beliefs about God. The scans showed how her brain was able to connect her to the religious and spiritual ideas that she held so dearly. Of course I was very pleased to have made this nun happy, and when she thanked me for the study and all that I had shown her I merely said, “You’re welcome.”

But the really fascinating interaction occurred several months later when our research paper was finally published. I received a phone call from the head of the local atheist society in Philadelphia. I answered the phone with some trepidation, not knowing exactly how he would have taken this paper, which showed changes in the brain during religious experience. Immediately after greeting him, he said to me, “Dr. Newberg, I want to thank you so much for doing this brain scan study of prayer because it clearly shows that religion is nothing more than a manifestation of the brain’s functions. There is no God. Everything that people think from a religious perspective is merely their brain creating the experience.” At first I was taken aback by his response but then quickly said, “You’re welcome,” and discussed with him a little bit more about the potential that neurotheology might offer the atheist perspective.

Later that night, I reflected on the response of both the atheist and the nun to what essentially was the same information. Both people had looked at the same brain scan data but come away with completely different conclusions. For the nun, the brain scan supported her religious beliefs and validated her belief in God. For the atheist, the findings validated his belief that God does not exist.

As the field of neurotheology has continued to grow and develop, we have seen a variety of responses to the data coming out of the early studies. Of course, neurotheology is really in its infancy in terms of what it might be able to do or say about religious and spiritual phenomena. It is remarkable that when our first studies of meditation and prayer were published, there were only a handful of other brain scan studies that looked at similar types of practices. Today, on PubMed, a database of biomedical literature, there are over 150 papers that have looked at the effects of meditation and spiritual practices on the human brain and body. And there has been an exponential increase in the number of studies in the medical literature regarding the relationship among religion, spirituality, and health. With all of this interest in the intersection between science and religion as it pertains to the human body, and particularly the human brain, neurotheology appears to be a field poised for expansion in the rest of the century. Much will depend on how the questions and aims of the research are formulated, however. Neurotheology might even be able to address important mind–body problems in terms of how brain processes are associated with various thoughts, feelings, and experiences, particularly those connected to religion and spirituality. And since these experiences are frequently associated with altered states of consciousness, perhaps neurotheology will even unlock the mysteries of the nature of consciousness.

Neurotheology is a hybrid, multidisciplinary field that brings together the “neuro” piece and the “theology” piece. But the responses from the nun and the atheist pose a particular question that is central to the field of neurotheology, which is actually an epistemological question: How do we know what is really real?

This is the question that began my own quest to explore neurotheology. Although I didn’t call it neurotheology at the time, when I was very young, I wanted to understand why people looked at the world so differently. How could people look at the same world but come away with such different perspectives—religious versus atheist, Republican versus Democrat? I initially thought the answer would lie within science, since science helps us to see the world in an objective way. But science is performed by scientists, and every scientific understanding of the world still arises within the brains of those scientists. Furthermore, science seems to assume that reality is the way we can measure it. But what if that is not the case? Does science ever provide a way to get outside the prison of our brain? The epistemological question of the nature of reality seemed to me to also require a philosophical analysis. As I pursued these questions through my own philosophical contemplations, I realized that the answers were far more elusive if I proceeded by only using science, philosophy, or religion alone. It seemed that only an integrated and multidisciplinary approach, such as neurotheology, could provide even the possibility of answering such questions.

Thus, the question of what is really real is a question central to neurotheology. But the question of reality is of particular interest to neurotheology because one of the critical distinctions between science and religion is related to the existence or nonexistence of a supernatural or nonmaterial entity such as God. For the religious person, there is no doubt that God exists, and for the atheist, there is no doubt that God does not exist. How do people come to radically different conclusions, especially, as in the case of my prayer study, when they are looking at exactly the same information—the universe? For me, this issue comes back to the question of how our brain helps us to perceive reality, which is the question that brought me into this field in the first place. After all, when we explore the nature of reality, we confront two primary interpretations: the religious and the scientific. Trying to understand how these interpretations relate to each other and to the world is what drove me to pursue neurotheology.

Consider the relationship between the brain and the mind. Is the mind, consciousness, identical with its brain states, a byproduct of them, or completely independent? This massive philosophical and scientific conundrum, known as the mind–body problem, has plagued humanity for thousands of years. Ancient Greek philosophers including Plato believed that there was an ultimate domain of thoughts and ideas separate from the physical roots of our own existence. Descartes’s dualism also considered the mind and brain to be distinct entities. Modern cognitive neuroscience, in some sense, brings the two together in the reductionist approach that the brain creates the mind. Other thinkers have proposed different approaches to the mind—that is, our experiences, emotions, and thoughts—as a way of interpreting and making sense of our world.1 In this book, we are more specifically looking at the brain’s representation of our thoughts and experiences of reality. However, it is important to remember that there are many complex interactions between the mind and the brain that remain a mystery in spite of many attempts to clarify them. Hopefully, neurotheology will encourage additional investigation into the relationship between the mind and brain, whether they are separate, equal, or co-related, and how they help us experience reality, especially religious and spiritual experiences.

The field of cognitive neuroscience has exploded over the last two decades with the advent and development of many advanced brain imaging techniques. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), positron emission tomography (PET), and single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) have led the way in showing us how the human brain works. Cognitive neuroscience helped us to see how the brain performs simple tasks like moving a finger or feeling the brush of a person’s hand on our wrist. And it helped us understand complex processes related to love, morality, attention, and ultimately religion.

It seems that no matter which study one considers, something is going on in the brain no matter what we do. In fact, one of the most recent areas of research has been the default mode network, which is active particularly when the brain is doing nothing at all.2 As a neuroscientist reviewing all of these data, I have realized that there is never a time that the brain is not active. Whether we are awake or in various stages of sleep or dreaming, whatever we are doing, our brain is always on. Even people who are comatose have brain activity, albeit markedly diminished in capacity. What this ultimately tells us is that everything that happens to us, everything we do, think, and experience, affects the brain. Every facet of reality has an impact on our brain in one form or another, which in turn helps us to interpret what that reality actually is. The problem lies in whether what we perceive internally is related in any way, shape, or form to what is going on externally. This question is relevant particularly to religious and spiritual beliefs, which are so often at the crux of arguments about the ultimate nature of reality.

Given everything we know from cognitive neuroscience, we can never escape the processing of the brain. It seems that we are forever trapped within our own brain looking out at the world and trying to make some sense out of it. No matter how one tries to understand this perception from a scientific perspective, our brain and our consciousness seem to be a prison that we can never escape from.

Fortunately, the brain functions in a way that helps us deal with this imprisonment. Although we face the potentially terrifying problem of never really knowing anything for certain, we somehow generally feel at ease within our own prison. Our brain generally does not constantly activate its stress areas to inform us that we should be worried or fear the world all the time. Generally, our emotions remain calm and even positive in the face of a very scary universe. Thus, in many ways, it is a happy prison because the brain works in a way that makes us feel comfortable with what we don’t know.

There are many examples that we can turn to that show just how problematic the prison of the brain is and yet just how comfortable we seem to be with it. Let’s explore a little more the issues that arise from this happy prison of the brain. When interpreting our sensory experiences, our brain makes many mistakes. Unfortunately, it never tells us when it has made a mistake, which is one way the brain keeps us happy. The most readily apparent examples of sensory mistakes are the tricks performed by magicians who find all kinds of ways of confusing our senses and making us believe something is happening one way when it really is happening another way. In fact, we seem to delight in the occasions when we misperceive the world and then finally come to realize that misperception.

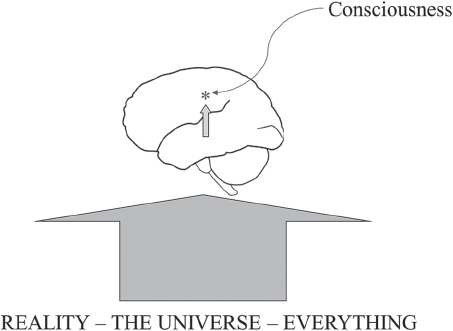

Cognitive neuroscience has demonstrated many ways in which various visual and auditory illusions can fool the brain. It also shows how difficult it is for the brain to perceive the world accurately. Illusions can work even when we know what the illusion is. An image that appears to show curved instead of straight lines continues to look that way to us even when we have taken out a ruler and proven to ourselves that the lines are actually straight (figure 1.1). How many problems have arisen because someone thought that he heard someone say something that was never said? And yet, we continue to think that we have a full grasp of the universe, a foolish mistake given the fact that the universe is essentially infinite and we have a very finite brain (figure 1.2). Right now, each of us is only aware of what’s going on in our immediate surroundings. We feel the book we are holding and perceive the letters and words we are reading. We might hear a siren outside. But, we are never aware of what’s happening on the other side of the country, on the other side of the planet, or on the other side of the galaxy. Things are happening in all of these different places, but our brain has no knowledge or sensory experience of any of them. And yet again, the brain seems quite content in its belief that it knows everything that we need to know in order to survive. This in part explains certain phenomena, such as why people think that they are not impaired while driving under the influence of alcohol or while texting. The brain keeps telling the person they are doing a very good job managing reality, when in fact the data show just the opposite.

FIGURE 1.1. In this visual illusion the lines appear curved even though they are all parallel or perpendicular and completely straight.

FIGURE 1.2. A representation of how our brain exists within an essentially infinite universe. Only a limited amount of information (< 0.00000001%) from the external world (large arrow) comes into the brain. The brain then filters out much of that information so that an even smaller amount reaches our consciousness represented by the*. This serves to show how we are trapped within our brain and the difficulty our brain faces in trying to make sense of the universe.

One of the more amazing aspects of the human brain is its ability to think far beyond what we experience. We can contemplate what it is like on the other side of the planet or in another part of the galaxy and somehow relate that back to our own personal experiences. We can envision time on a scale of billions of years into the past or future.3 We may even contemplate things unseen, such as consciousness, the afterlife, or God. Given that we have enough trouble figuring out what is happening in our everyday reality, it is fascinating that the human brain has gone out of its way to consider supernatural and divine concepts.

On the other hand, there have been some very interesting studies documenting how our brain can completely exclude certain pieces of information even when they are in full range of our sensory experiences. In a study called “Gorillas in Our Midst,” researchers showed a video to test subjects and asked them to count the number of times that a group of people threw a ball back and forth.4 At one point in the video, a person wearing a gorilla suit walks in, waves his arms, and then walks out. The researchers found that at least half the people watching the video never saw the gorilla. When the brain is completely concentrated on one thing, it has a great tendency to completely ignore many other aspects of our sensory experience. So if we can’t trust our brain’s processing of even the raw data from the world, how do we ever know if what we are thinking on the inside is accurate?

And what perceptions help us to accept or reject God’s existence? I was once interviewed about comments made by the noted atheist Richard Dawkins about religious people. I was asked my opinion of his statement that he did not understand how people could believe in something, God, for which there was absolutely no evidence. I said that the problem with his statement had to do with how Dawkins used the word “evidence.” If you were to ask people in a church or mosque if they have evidence that God exists, they will all tell you about the many pieces of evidence that they have. These people have experienced God at the birth of a child, watching a sunset, or resolving a presumably impossible personal situation. These are perceptions, often sensory, that people have about God. Dawkins is correct that such evidence may not meet certain scientific standards, but from a neurotheological perspective, we must be careful about how we assess evidence of any kind. After all, there is no scientific proof that I love my wife, but I have all the evidence I need based on my personal experience. So what type of evidence does our brain need to determine the nature of reality or the existence of God?

Assuming the brain does perceive some of the sensory stimuli from the external world accurately, how much can we trust the next processing step of that input? Our brain takes all the sensory information it receives and begins to construct a three-dimensional representation of the world that includes what the world looks like, what it smells like, what it sounds like, and how we seem to interact with it. This is also where we start to use language to help us explain or identify various objects that are out there in the universe. We provide names for things so that we can understand what they are and how we might categorize them. We can categorize a poodle, a Great Dane, and a schnauzer as different types of dogs. And we can distinguish dogs from cats, which each have different properties. Of course, our brain can be fooled: If we were to suddenly see a small four-legged animal run across our backyard, we may not necessarily know whether it was a cat or a dog.

The way we use language can alter the ways in which we actually perceive things. One interesting study asked participants to watch a video of a car accident. Observers who were asked, “How fast were the cars moving when they smashed into each other?” reported much higher velocities than observers who were asked, “How fast were the cars moving when they hit each other?” Swapping the word “smashed” (which implies a higher velocity) for “hit” apparently caused people to retrieve the event differently and report it as having involved a higher velocity.5 Since our language can alter the way in which our brain perceives and understands reality, we might wonder how much the words we use shape our religious beliefs and vice versa. This could be an important avenue of future study for neurotheology.

Our cognitions also include our memory functions, which, like everything else in the brain, can be highly flawed. We can make all kinds of mistakes in recollecting things that happened to us in the past or information that we thought we once knew. It has even been shown how our memories can be manipulated by the ways in which we are asked to retrieve them. There have been many examples where a person “remembered” instances of abuse during childhood that turned out never to have occurred.

As we are trapped within our brain, we are also to some degree trapped within our own memory system. We are who we remember we are because of all the experiences that were part of our lives. We don’t remember what college was like for somebody else; we remember what it was like for us. This helps us to construct a personal narrative, or life story, that in turn helps us to identify who we actually are and differentiate ourselves from the rest of the world. But our memories of ourselves can be just as flawed as memories about everything else. Religions try to take advantage of our memory systems by engaging them at an early age. As children, we are told the stories of the religious tradition, and we are told about the spiritual leaders of the past and the nature of God. These ideas are written into our memory systems early on, so much so that we often cannot help but remember the world with a religious flavor. But little is actually known about the relationship between childhood memories of religious concepts and future beliefs other than the generally accepted premise that the majority of adults adhere to the religious tradition within which they were raised.6

As imperfect as our memories and cognitions are, our emotions can be even more imperfect. Interestingly, we rely on our emotions to establish our beliefs about the world, as well as to defend them. When we are presented with new information about the world, we immediately use our emotional processes to tell us whether that information feels good or bad to us. Is it consistent with the ways in which we already have thought about the world, or does it perhaps provide a more effective way for understanding the world? In either circumstance, we are very likely to accept a new piece of data as important and truthful if it feels right and elicits a positive emotional response. One of the most common types of psychological studies that support this notion works by “priming” an individual before developing a belief or making a decision about something.7 These studies, which might ask someone to decide whether or not to buy a specific product, will start by evoking either a positive or negative emotion in the test subject. When a person is induced to be in a positive emotional state, he or she is much more likely to think that the product is useful and decide to buy the product.

If on the other hand, we are presented with some piece of information that does not feel right to us, or even upsets us, we are likely to reject it outright. This is borne out in the same types of studies just described in which a negative emotion, or sometimes even rainy weather, will contribute to someone’s rejection of a specific idea or product. We would never incorporate that negative-feeling information into our belief system. When we extrapolate this to the study of religious and spiritual phenomena, we can understand how people can come to diametrically opposed perspectives with regard to the existence of God. For the religious person, the notion that God exists is a very powerful, emotionally positive concept. The positive emotion itself helps to reinforce the belief about God. The emotional centers of the brain, particularly the amygdala and hippocampus, are connected to our memory centers, so these strong, positive emotional responses to God or religion create even stronger memories about the importance of religion in the person’s life. The atheist would look at the same information from the opposite perspective. Any description about God might be met with very negative emotions and hence continue to support the rejection of that particular concept.

Science itself is not immune to this particular problem. For example, we see all the time in the medical profession how emotions can run quite high when people are confronted with scientific data that run contrary to a prevailing understanding of something. Twenty years ago, when I was a resident, the first studies came out suggesting that stomach ulcers might be caused by a bacterium rather than stomach acid. Many people in the medical profession were outraged. This sounded ridiculous to them and triggered very strong emotional responses including ridicule of the scientists initially proposing the idea. Today, stomach ulcers are typically treated with antibiotics because we now have fully recognized that the bacterium Helicobacter pylori is the causative agent of most stomach ulcers.

In physics, one of the great examples of emotions altering the way a great scientist thought about the universe concerns Einstein and quantum mechanics. For Einstein, quantum mechanics just never made sense and even triggered very negative emotional responses. His famous quote that “God does not play dice with the universe” clearly shows an emotional negativity toward the notion of quantum mechanics. Einstein tried to reject quantum mechanics in many experiments, but each time the theory survived. However, Einstein never acknowledged how well quantum mechanics kept performing even in the face of his staunch opposition. And as with our senses and our cognitions, when we have an emotional response to something, our brain treats it as if it is the normal response. We do not find our emotional responses to be strange or abnormal. And so our emotional responses to scientific, political, religious, or any other viewpoints or pieces of information just seem like the natural processes by which we understand the world.

When we try to see or think beyond the happy prison of our brain, one source that we sometimes turn to is the opinions of others. After all, every person who has a brain is in the same boat. We are all trying to look out on the world and to make sense of that world. So it is reasonable to ask someone else what he or she thinks about an event or fact to see if it corroborates what we think. Social influence is an incredibly strong factor in affecting the way in which our brain perceives reality and often results in very flawed ways of thinking.

Most of our beliefs are actually created through social interaction. Our earliest beliefs come from our parents or caregivers, often regarding how to behave, what is morally correct or incorrect, and even what religious or spiritual perspectives to follow. If we grow up in a household in which going to church every day is the norm, then the neural connections that support that particular belief become stronger. It becomes very difficult to reject the religious beliefs that we’ve grown up with because they are inscribed so strongly into the memory, cognitive, and emotional systems of the brain. As we grow up, we initially encounter our friends and teachers at school. We listen to what they have to say about the world, and we modify our beliefs accordingly. If our history teacher says that the Civil War was a great event for the United States, then that is what we tend to believe. And our beliefs might be different depending on what part of the world we grew up in. As we grow older, the friends we meet at college, our professors, our work colleagues, and ultimately the general society around us have a tremendous influence on the beliefs we hold.

We are far more influenced by people with a perceived sense of authority. If a doctor tells us that we should follow a particular type of diet, we are far more likely to do so than if an acquaintance tells us the same thing. That is also why celebrities promote everything under the sun—we are more likely to buy a certain brand of shampoo, drink a certain beer, or eat a certain food if someone we admire and respect tells us to. Interestingly, we also gravitate toward people who espouse ideas and information that is consistent with our belief systems. This is because the emotional centers of our brain become very uncomfortable if we are in a group of people who tend to view the world in a substantially different manner than we do. Think about your friends and colleagues and whether they tend to share similar religious and political beliefs. There is a reason that this is usually the case.

When we are confronted with a person whose beliefs oppose ours, the brain seems to have one of two choices. We can accept the new piece of information and realize that the other person might have a better view of the world than we do. However, this is a very anxiety-provoking (and rare) scenario because it implies that we do not understand the world as well as we thought. The alternative perspective is to assume that we are correct and that the person presenting us with the alternative data is wrong. Believing that we are correct is far more satisfying and emotionally comfortable than believing that somebody else is correct.

Extrapolating to religion and spirituality, we are far more likely to want to talk to people who hold similar beliefs to our own because they will help to support the beliefs that we have and make us feel more comfortable. If you are a religious person, being around other religious people who support your belief in God makes you feel far more comfortable and allows you to continue to be happy in the prison of your brain. The same is true with atheists who would much rather congregate with people who have similar belief systems that don’t include, or even reject, God. We can all understand how difficult it would be if we were surrounded entirely by people who believe something completely different from ourselves. We would constantly be battling others cognitively, socially, and emotionally. It would be a very stressful situation. This is not without precedent, however, as we have seen many societies and governments around the world that have fostered or espoused prejudicial ideas and were highly opposed to certain groups. Examples such as the Nazis in Germany or the communists in the former Soviet Union show how very strong negative belief systems can impact the beliefs of multiple groups. Both the in-group and the out-group can be severely affected by the overall belief system.

Religions throughout history have fallen into the same problem—anyone who has an oppositional belief is typically regarded at best as wrong and at worst as heretical, to be burned at the stake or stoned to death. After all, if we come to the conclusion that our own belief system is correct and that another person’s is incorrect, we might also begin to wonder why he continues to tell us that he is right when clearly he must know that he is wrong. Given that he is continuing to tell us something “known” to be false, we might think of him not only as wrong, but as evil. Such a belief may contribute strongly to the modern-day problem of religious radicals who hold almost anyone from another religious belief system to be evil and worthy of destruction. In a later chapter, we will consider the social and religious problems that can arise from such a highly negative perspective.

So why did we start our discussion of neurotheology with the image of the happy prison of the brain? For one, we are going to spend most of this book talking about the brain, how it works, and how it helps us create our beliefs and our perspectives on reality. In this regard, religion and God can be an essential part of many people’s belief systems. Our brain evaluates its experiences and helps us decide whether to believe in God or not. We might ask thirty people to read the Bible; ten may then identify as Jews, ten as Christians, and ten as atheists. Who is right, and who is wrong? Maybe neurotheology can help us to find some answer to this question. But neurotheology is also a construction of the brain, and so we need to look for novel approaches to answering questions about reality that combine our conscious or subjective experience of the world, scientific data, and religious belief.

The real question is, no matter what our prevailing belief system, how can we actually escape the happy prison of the brain? This is much like Plato’s famous allegory of the cave. Remember that the prisoners were initially facing a wall on which they could see only shadows. The shadows were cast upon the wall by a fire behind them. Between the prisoners and the fire was a path across which different people, animals, and objects moved, thus casting the shadows. But the prisoners initially were never able to turn around to see the true reality; they could see only the shadows. The shadows thus became their entire reality.

One day, one prisoner was allowed to turn around to see the fire and the actual objects casting the shadows. This person now had a completely different perspective on reality. Although this experience was painful and fearful at first, the prisoner would eventually come to regard the objects and the fire as representing the true reality. Plato continues the allegory by asking us to imagine the prisoner being allowed to leave the cave to see the sunlight and the external world. Again, with great fear, the prisoner would eventually conclude that this outside world represented a higher, or more real, reality.

The ability to raise new questions and bring about new ideas is an important part of what neurotheology as a field strives to accomplish. It is also important to determine who is most constrained by the prison of the brain; is it the religious believer, the atheist, or both equally? One final point about the prison of the brain and Plato’s cave is that in the allegory, the prisoner allowed to see the true reality is not likely to fare well upon returning to the cave. The other prisoners, hearing of this other reality that they cannot see, are likely to ridicule the “enlightened” prisoner and might even try to kill him in order to maintain their own perspective. It would seem that two thousand years later, neurotheology is in the position of trying to help us out of this prison. Perhaps by combining all of its elements—the scientific and the religious—neurotheology might be up for the challenge.