CHAPTER TWO

America in World War II and the Beginnings of Central Intelligence

IF MOST ASPECTS OF THE American intelligence effort fell well behind the country’s rivals and enemies after World War I, the United States did have remarkable success in the field of communications intelligence or code-breaking—especially against Japan. In the Washington Naval Conference of 1922, the World War I Western Allies tried to prevent another ruinous naval arms race like the competition between imperial Germany and Great Britain before 1914. The United States and Great Britain were alarmed by growing Japanese aggressiveness following Japan’s shocking destruction of the Russian fleet in 1905 and wanted to limit the size of the Japanese fleet relative to the size of the American and British battle fleets. The United States was successful in limiting the number of Japanese battleships because brilliant American code-breaker Herbert Yardley could read Japan’s diplomatic telegrams that laid out its negotiating strategy.1 In September 1940, the same month that the British broke the famous German “Enigma” cipher machine, US Army analysts began reading what US code-breakers called Japan’s “Purple” diplomatic machine.2 The British called the Enigma messages ULTRA, while the Americans used the code word MAGIC for decoded Japanese material. Unhappily, despite the reach of American radio intercept stations, and the skill of American military code-breakers, the national effort was muddled by bitter rivalry between the American navy and army, which refused to cooperate until forced to do so. Beyond that rivalry, the Japanese messages were so secret that only the most senior Washington officials—including President Roosevelt and the secretaries of state, war, and the navy—saw them. As William J. Casey, a senior OSS officer who later became President Ronald Reagan’s director of central intelligence, said: “The military had confined the priceless intercepts to a handful of people too busy to interpret them. . . . No one had put the pieces together . . . and told [senior officials] of their momentous implications.”3

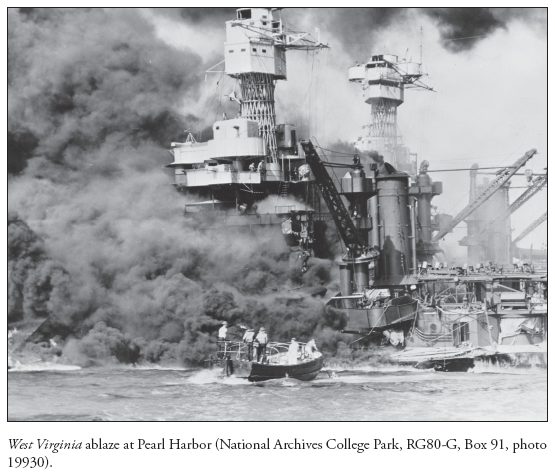

Among the first to suffer the consequences of America’s feeble intelligence apparatus were Commander Hillenkoetter and the sailors of the Pacific Fleet on Sunday, December 7, 1941. The captain of West Virginia, Mervyn Bennion, was mortally wounded early in the attack, and executive officer Hillenkoetter was trapped by fierce fires sparked by the explosion of Arizona as well as by the more than half dozen torpedoes and bombs that struck his ship.4

Thanks to the heroism and skill of her crew, West Virginia was saved from capsizing, but settled to the bottom of the shallow harbor with relatively light loss of life as her surviving crew continued to fight raging fires. The next day, on orders from Admiral Walter Anderson, who as director of naval intelligence had been Hillenkoetter’s boss when he served as attaché in Paris in 1940, Hillenkoetter sent two sailors to hoist an American flag over the ruins of Arizona.5

Both Commander Samuel Fuqua of Arizona and Captain Bennion of West Virginia received Medals of Honor at Pearl Harbor, while Hillenkoetter, also wounded, only received a Purple Heart. A black mess attendant, Doris “Dorie” Miller, who helped defend West Virginia and evacuate the wounded, was awarded the Navy’s third-highest honor, the Navy Cross, in May 1942 by Admiral Chester Nimitz, Commander in Chief of the Pacific Fleet. Within a week of the Japanese attack, Hillenkoetter was appointed executive officer of Maryland, whose crew worked around the clock to make quick repairs, allowing the battleship to support the decisive Battle of Midway in early June 1942, which fatally crippled Japan’s naval air forces.6

Finally, in September 1942, newly promoted Captain Hillenkoetter was given one of the most important, but also most controversial, intelligence assignments in the navy, when he was appointed chief of intelligence for Admiral Nimitz.7 Hillenkoetter’s new office grew from one of the navy’s string of Pacific radio-intercept and direction-finding stations used to locate the positions of Japanese warships and try to listen to their communications. The Japanese had been emboldened by their victory over Russia in 1905 and were angry and resentful that American code-breakers had forced them to accept the humiliating battleship limitations of the Washington Naval Conference of 1922. The Japanese knew of this intelligence success because Herbert Yardley boasted about this triumph in his book The American Black Chamber, published in 1931 after moralistic Secretary of State Henry Stimson had shut down American code-breaking in 1929.8 Yardley’s book was widely read in Japan, but fortunately for the United States, despite Japanese efforts to protect its secrets during World War II, American code-breakers repeatedly gave American leaders insight into Japan’s secrets.

In the 1930s the militaristic Japanese government set out on an aggressive expansionist course. It annexed Manchuria and brutally attacked China. Like Germany at the same time, Japan also energetically built up its military forces while trying to conceal its new strength. The country limited the freedom of foreign, especially American and British, military attachés and went so far as to erect screens around its shipyards to hide the construction of what was to be the world’s biggest battleship: Yamato. Well aware of the Japanese threat, and eager to keep close watch on the imperial navy, the United States Navy established radio posts in the Philippines, on the Pacific islands of Guam, Samoa, Midway, and Hawaii, and as far north as Dutch Harbor, Alaska.9 Over the vast distances of the Pacific Ocean, the only way to locate ships was for several stations to hear their radio transmissions and then triangulate their location, and continuing to listen to establish their course and speed. Several of these stations, including Cast in the Philippines and Hypo in Hawaii, were also staffed with code-breakers, who worked with naval code-breaking headquarters in Washington to break Japanese naval codes. Unfortunately, the work on the Japanese Purple diplomatic codes was carried out only in Washington and, as noted by CIA director William Casey, not shared with Hawaii, the American military stronghold first attacked by the Japanese in December 1941. Also, the Japanese navy had carefully prepared for the December attack and kept strict radio silence from the time their aircraft carriers left port until their aircraft appeared over Hawaii. Navy listening posts knew that the Japanese fleet had disappeared into the vast Pacific Ocean but had no idea, or any way of discovering, exactly where it was.

The Japanese believed that the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, which crippled the American Pacific Fleet, would give them the freedom to overpower all of Southeast Asia and the Pacific Islands, and for months it appeared that they were correct. Guam quickly fell and, after unexpectedly stout resistance, so did Wake Island.10 The day after Pearl Harbor, Japanese bombers crippled General Douglas MacArthur’s Philippine air fleet, the strongest American air forces outside the United States. Two days later Japanese aircraft attacked and destroyed the British battleship Prince of Wales near Singapore, the first—but not the last—time that such a powerful ship would be destroyed exclusively by air attack. Just before Christmas, Japanese army forces landed on the main Philippine island of Luzon, and on Christmas Day, Hong Kong fell. Although US Army soldiers hung on stubbornly on Bataan and the island of Corregidor, the personnel of the navy’s Cast listening post were moved to safety in Australia. MacArthur escaped on a PT boat with a Medal of Honor for “conspicuous leadership in preparing . . . to resist conquest . . . confirming the faith of the American people in their Armed Forces.”11 The starving survivors of the US Army in the Philippines finally surrendered at Corregidor in early May 1942, just three weeks after army bombers, led by Lieutenant Colonel James “Jimmy” Doolittle, flew off the aircraft carrier Hornet and bombed Tokyo in the first dramatic American counterattack—and less than five months after Pearl Harbor.12 A month after Corregidor came the first great American success of the Pacific war, thanks in large part to the skill of American intelligence officers and the commander who trusted them.

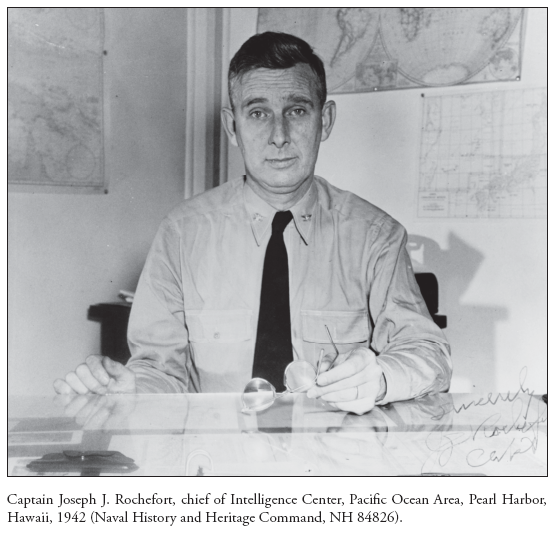

Since May 1941, brilliant code-breaker Joseph Rochefort, one of only fifty navy officers trained to understand Japanese, had commanded the Hawaiian intelligence station Hypo. Officially, Rochefort and Hypo worked for the navy’s code-breaking organization in Washington, but Pacific Fleet commander Admiral Husband Kimmel and his fleet intelligence officer, Lieutenant Commander Edwin T. Layton, another Japan expert, looked to Rochefort’s local office for overall intelligence support.13 Indeed, beyond radio interception, Rochefort’s newly named Combat Intelligence Unit (CIU) began trying to understand the organization of the Japanese fleet and the capabilities of such dangerous Japanese weapons as the Zero fighter plane. Both Layton and Rochefort quickly gained the hostility of their Washington superiors, such as the navy director of war plans, Captain—later admiral—Richmond Turner, who felt that his operational planning staff, rather than intelligence officers, should be responsible for analyzing Japanese intentions. Turner and his Washington allies not only withheld access to Japanese MAGIC diplomatic messages, but then blamed Admiral Kimmel and his Hawaii staff for the Pearl Harbor disaster. In his outspoken memoirs, Pearl Harbor intelligence officer Layton described Turner as an “opinionated, stubborn fool” and recounted almost coming to blows with the very senior admiral during the final Japanese surrender in Tokyo Bay in September 1945.14 Remarkably, while Kimmel was recalled in disgrace in December 1941 and Rochefort himself was later ruined by his jealous Washington navy enemies, Layton continued to serve as fleet intelligence officer for Admiral Nimitz’s Pacific Fleet until almost the end of the war.

When Admiral Nimitz took command of the shattered Pacific Fleet in late December, he prudently retained almost all of Admiral Kimmel’s staff, including his intelligence officers. Unfortunately, he had few weapons with which to resist the Japanese advance through the Philippines, the South Pacific islands, and across the Pacific Ocean. His battleships were damaged or destroyed, but by a stroke of good fortune, his aircraft carriers had been away from Pearl Harbor on December 7, and he still had Commanders Layton and Rochefort. Nimitz and Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Ernest J. King spent the spring of 1942 planning their counterattack and drawing up the outline for a Pacific Fleet joint intelligence center. The center would collect and analyze photos, maps, and radio intercepts; gather all that information into an authoritative reference database; and then try to estimate Japanese locations, strengths, and intentions. Meanwhile, Rochefort’s fifty-person CIU staff worked to locate Japanese warships and, most important, to attack and finally break new high-level Japanese naval codes. Based on this new MAGIC intelligence, Rochefort and Layton persuaded Admiral Nimitz to set a trap for the Japanese fleet by making it appear that the small American garrison on Midway Island was suffering a water shortage. Subsequent Japanese radio messages confirmed that Rochefort had indeed broken their code.15 In June 1942 Nimitz’s aircraft carriers ambushed the unsuspecting and confident Japanese carriers. The Japanese navy would never recover from the loss of those carriers and, even more significant, from the loss of their highly trained and skillful pilots.

A few weeks later, on June 24, 1942, Admiral Nimitz created the Intelligence Center, Pacific Ocean Area, or ICPOA, with Rochefort as commander. Rochefort’s original CIU was still responsible for radio interception, direction finding, and code-breaking. The larger center, with some 190 staff, now added sections to analyze captured documents and prisoner interrogation reports as the navy and Marine Corps began retaking Pacific islands, starting with Guadalcanal, which had been captured by the advancing Japanese army. The center also began publishing weekly reports to Washington and the Pacific Fleet so that the officers on the islands and aboard the fighting ships would have the latest intelligence, translations, interrogations, information on Japanese weapons and tactics, and ICPOA’s best estimates on the enemy’s strength and location. For Rochefort’s brilliant contribution to the victory at Midway, Admiral Nimitz nominated him for the Distinguished Service Medal, but Chief of Naval Operations Admiral King, swayed by jealous enemies in Washington who tried to take credit for Midway while blaming Rochefort for missing warning signs before Pearl Harbor, refused him this honor and recalled him from Hawaii. Eventually, this exceptional Japanese linguist, intelligence officer, and code-breaker was assigned as commander of a floating dry dock in San Francisco.16

In his place, Captain Roscoe Hillenkoetter was appointed commander, Intelligence Center, Pacific Ocean Area (ICPOA), a position he held from September 1942 until March 1943. In the words of one historian, “Simultaneously dismayed and driven by duty, ICPOA’s analysts continued working without their former commander to provide the best intelligence they could for [Nimitz].”17 Aside from serious morale problems, Hillenkoetter had to deal with many of the same resource problems facing the entire American war effort. New personnel with basic Japanese-language skills would appear, but they would be without necessary analytic skills or experience, which required extensive on-the-job training. Normally, analysts would work fifteen to seventeen hours a day, seven days a week. However, during Hillenkoetter’s months, the number of personnel would sometimes not match the workload, and people would be moved to other assignments in a “helter-skelter personnel flow” that hindered the delivery of intelligence to Nimitz.18 Hillenkoetter did have access to OSS reports, since a small Coordinator of Information (COI) office had been set up in Honolulu a month after Pearl Harbor. The office continued under OSS to provide analytic studies, secret agent reports, and interrogation information to the navy. Admiral Nimitz, on the other hand, never permitted OSS to receive ICPOA information.19

With much of Southeast Asia and the southwestern Pacific lost to the triumphant Japanese navy and army, early American and British efforts focused on protecting Australia and supply lines to the United States. After the Philippines fell, the Japanese threatened Port Moresby on the island of New Guinea from their base at Rabaul on New Britain, as well as Allied supply lines from a new airfield the Japanese were building on Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands. After a brief but bitter dispute between General MacArthur and Admiral King about whether MacArthur or Nimitz should direct the new campaign, US Marines landed on Guadalcanal in early August 1942 and immediately seized the Japanese airfield. For the next six months, each side struggled to send more troops and supplies to the mountainous jungle-covered island, with the American and Japanese fleets clashing repeatedly in bloody duels. While the US Navy was initially at a clear disadvantage, by the time the Japanese abandoned the island in February 1943, the American fleet had proven itself the equal of the Japanese. On shore, the American marines and army soldiers proved equally determined and fierce, while in New Guinea, Australian troops stopped the Japanese advance despite General MacArthur’s low opinion of their ability.20

Slowly, the war began to produce useful intelligence for Hillenkoetter’s analysts. The first Japanese prisoner of war had been Ensign Kazuo Sakamaki, the only survivor from the five midget submarines that participated in the attack on Pearl Harbor. He considered his capture a disgrace, demanded to be shot, and refused to answer any questions. On the other hand, thirty-two sailors from the aircraft carrier Hiryu, including the chief engineer, had been abandoned as the carrier sank during the Battle of Midway. An interrogator flown out from ICPOA found them “reasonably cooperative” in disclosing “many facts and details clarifying our knowledge of the battle.”21 In early 1943, according to an ICPOA analyst, US troops on Guadalcanal began capturing a “steady stream” of Japanese personal diaries written in a cursive script that American translators found very challenging. “Japanese soldiers and sailors were addicted to keeping diaries. Some . . . had real literary merit. Sometimes they provided intelligence of considerable value and occasionally they were evidence of war atrocities.”22

Two analytic successes were particularly important. A map from a crashed Japanese airplane showed the secret code used to designate any geographic location in the world, but it was not until US Marine officer Alva B. Lasswell suggested using a nursery rhyme by which Japanese children learned their language that the code “fell into place like a marine platoon at the bugle’s call.”23 In early 1943 ICPOA code-breakers also broke the code used for Japanese supply convoys. Every morning, intelligence analysts would meet with Pacific Fleet submarine planners to compare the movements of Japanese convoys to the current locations of US submarines. According to one scholar of the Pacific war, “There were nights when nearly every American submarine on patrol in the Central Pacific was working on the basis of information derived from [code-breaking].”24

In January 1943, at a conference in Casablanca, President Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Churchill agreed that while their first priority would be defeating Nazi Germany and winning the European war, there would be no easing of the pressure on Japan. Unfortunately, the army and navy continued to squabble over Pacific strategy and whether MacArthur or Nimitz should lead the attack. Finally, agreement was reached that General MacArthur, supported by Admiral William F. “Bull” Halsey, Jr., would attack northward from New Guinea and Guadalcanal. Soon, new and more effective American aircraft and tactics were turning the tide in the South Pacific, and with the Japanese increasingly unable to supply or reinforce their troops, Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, the victor of Pearl Harbor, decided to launch mass waves of inexperienced pilots against Allied positions in New Guinea and Guadalcanal. Their exaggerated reports of success so encouraged the Japanese that Yamamoto decided to visit them, and in mid-April code-breakers in Hawaii decoded the route his airplane would take. Captain Layton, Pacific Fleet intelligence officer, immediately reported the news to Admiral Nimitz, and on April 18, 1943, thanks to MAGIC, Japan’s best World War II military commander and strategist was ambushed and killed by US Army fighter planes.25

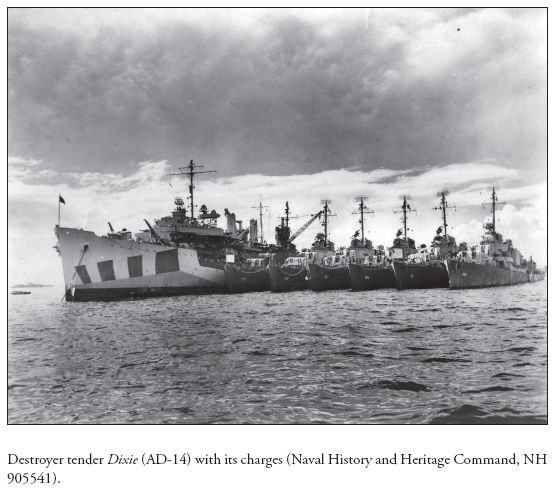

Just a few weeks before this great success by the analysts of the Pacific Fleet’s intelligence center, Captain Hillenkoetter had been transferred back to sea duty as commander of the naval destroyer tender Dixie in the Solomon Islands, where he served until February 1944.

Hillenkoetter had earned Nimitz’s commendation, and OSS chief William Donovan wanted him to take charge of OSS operations in the Pacific, “but the Navy would not release him.”26 During this period, Hillenkoetter also served as the representative of Admiral Nimitz’s destroyer commander in the South Pacific, putting Hillenkoetter again in the middle of the strategic competition between General MacArthur and Admiral Nimitz for control of the Pacific theater. Interestingly enough, Hillenkoetter’s fellow Missourian Samuel Fuqua of Arizona would later command Dixie from 1949 to 1950, by which time Hillenkoetter himself was Harry Truman’s director of central intelligence.27 For his service commanding Dixie, Hillenkoetter was finally awarded the Bronze Star “for meritorious service.”

As Hillenkoetter’s successor, army colonel and later brigadier general, Joseph J. Twitty, concluded, the intelligence center’s goal was not to produce “‘apple polishing perfection,’ but to provide enough intelligence to get the job done.”28 From this perspective, getting the job done meant helping Admiral Nimitz and the troops and sailors under his command in their daily fight against the Japanese, from island to island and over, on, and under the broad Pacific Ocean. The “combat intelligence” Hillenkoetter and then Twitty supplied included information about Japanese forces and their strength, disposition, and probable movements, but necessarily quickly expanded to include detailed data about the islands on which the Americans would fight in their long march to Japan.29

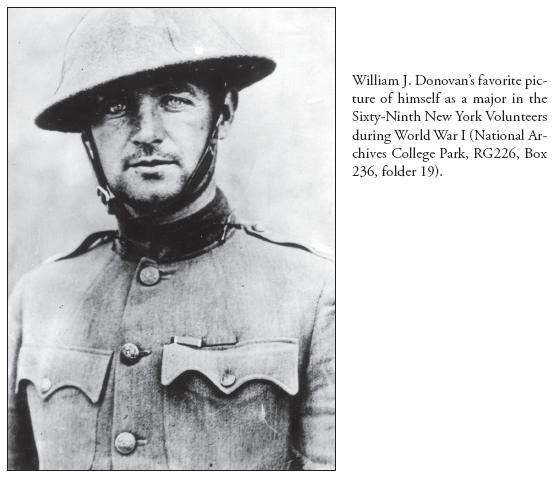

More general global information to help the president and his generals and admirals direct the worldwide war was left to ONI in Washington, the Army’s Military Intelligence Division, and an ambitious new organization led by dashing World War I Medal of Honor winner William J. Donovan.