CHAPTER THREE

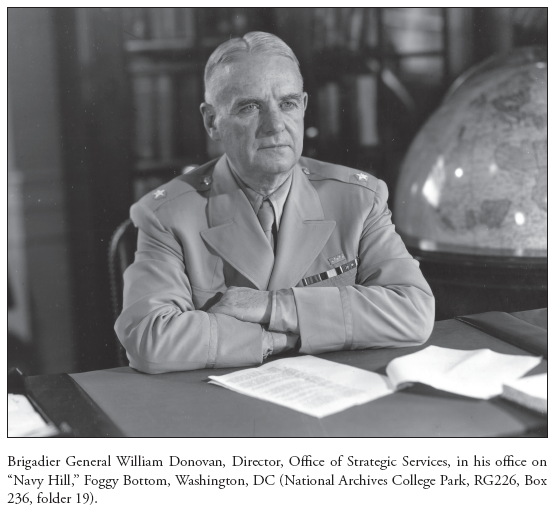

William J. Donovan and the Office of Strategic Services

HISTORIANS OF FRANKLIN ROOSEVELT HAVE noted how well suited his management style was to the popular idea of an intelligence chief—for good or bad. “I never let my right hand know what my left hand does . . . . I am perfectly willing to mislead and tell untruths if it will help me win the war.” His son James quoted him as saying, “You play the game the way it’s been played over the years, and you play to win.”1 He loved to hoard secrets, and “manipulated people, conducted intrigues, scattered responsibility, duplicated assignments, provoked rivalries . . .” To the frustration of his cabinet secretaries, who were responsible for advising him on foreign policy and national defense, Roosevelt delighted in managing his own foreign intelligence network of personal friends, whom he dispatched on private foreign missions, deliberately bypassing ambassadors and the few military attachés stationed overseas. Two of these men were wealthy Philadelphia journalist and novelist William C. Bullitt, “a man of great . . . intellectual energy, and egocentric brilliance” and Irish American college football quarterback, war hero, and prominent Republican New York lawyer William J. Donovan. Even before assuming the presidency in early 1933, Roosevelt sent Bullitt to Europe in violation of the Logan Act, which forbids informal diplomatic activity by private citizens.2 Despite embarrassing news stories about Bullitt’s activities, President Roosevelt appointed him his first ambassador to Moscow and later sent him to Paris, where he and Hillenkoetter worked on such audacious schemes as their effort to use fake documents to capture a suspected German spy after her escape from New York.

Donovan had been assistant US attorney general in the late 1920s and ran unsuccessfully as a Republican to replace Roosevelt as governor of New York when Roosevelt was first elected president in 1932. During the 1930s, he traveled frequently to Europe, meeting Italian dictator Benito Mussolini, observing the Italian war against Ethiopia, watching German military maneuvers, and even accompanying an attack in the Spanish Civil War. Donovan became close to the British intelligence chief in New York, William “Little Bill” Stephenson, who encouraged senior British officials—including King George VI, Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and Secret Intelligence Service (MI6) chief Stewart Menzies—to receive him in August 1940 after the fall of France to convince both Donovan and Roosevelt that England would continue to fight Hitler but desperately needed American help. Beyond encouraging President Roosevelt’s decision to give England fifty old American destroyers, Donovan requested and received many intelligence reports from the British, which were distributed among senior Washington officials. He also supported “full intelligence collaboration” between the United States and Great Britain, which still remains strong more than seventy years later.3 In December 1940 he was again in Europe and the Mediterranean—including the Balkans, Greece, and Egypt—meeting generals, senior government officials, and kings. As a CIA historian noted:

Wherever he went he discussed whatever pertained to the winning of the war-strategy, tactics, aircraft, ordnance, transportation, training, health [as well as functions he would include in OSS, such as] intelligence, special operations, psychological warfare, commandos, and guerrilla units.4

Donovan was greeted warmly in Washington upon his return in spring 1941 and even broadcast a radio report to the country reporting his conclusions. Not everybody was so enthusiastic, however, and on April 8 the army’s chief intelligence officer, Brigadier General Sherman Miles, wrote to General George C. Marshall in alarm:

There is considerable reason to believe [that Donovan wants] to establish a super agency controlling all intelligence . . . Such an agency, no doubt under Col. Donovan, would collect, collate, and possibly even evaluate all military intelligence . . . . From the point of view of the War Department, such a move would . . . be very disadvantageous, if not [disastrous].5

In fact, in 1940 and the early months of 1941, neither the restless Donovan nor the wily president seemed sure how to harness the colonel’s energy and enthusiasm. In a decision the army would regret, Secretary of War Henry Stimson rejected his request for command “of the toughest division in the whole [army].”6 Still, Donovan was obviously giving great thought to how best to organize a strategic national intelligence organization using the British Secret Intelligence Service as a model, and he spelled out his thoughts to his friend and supporter Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox in late April:

[The chief of intelligence operations] should be appointed by the president directly responsible to him and no one else. [He] should have a [secret] fund solely for . . . foreign investigation. [He should have] sole charge of intelligence work abroad, to coordinate the activities of military and naval attachés and others in the collection of information abroad, to . . . interpret all information from whatever source to be available for the president and for such other services as he would designate. [Beyond narrow intelligence functions] interception and inspection . . . of mail and cables; the interception of radio communication; the use of propaganda to penetrate behind enemy lines; the direction of active subversive operations in enemy countries.7

Not surprisingly, given the suspicion and hostility of military intelligence organizations—and Roosevelt’s own chaotic management style—Donovan never achieved his ideal. However, almost all of these powers eventually came to the director of the postwar national intelligence organization created by Roosevelt’s successor, Harry S. Truman.

The Coordinator of Information

Typically, Roosevelt kept his own counsel and toyed with Donovan, even suggesting that he take the job of selling war bonds in New York State.8 Finally, on June 10, 1941, Donovan and Roosevelt met privately, and the president scrawled a note to “set this up confidentially.”9 Again, Roosevelt left it to others to work out exactly what he meant, but while the Bureau of the Budget and army struggled to define Donovan’s new duties, the colonel was already bringing his new office into existence. On July 11, 1941, with the Battle of Britain over, the Atlantic U-boat war in full swing, the Japanese in China and Southeast Asia, and Germany two weeks into its surprise invasion of Hitler’s former ally Russia, Roosevelt finally signed the order designating Donovan “Coordinator of Information” to “collect and analyze all information and data, which may bear upon national security . . . and to make such information . . . available to the president . . . . And to carry out, when requested by the president . . . supplemental activities.” The order directed the rest of the government to give the COI “all and any such information” as Donovan, with Roosevelt’s approval, requested.10

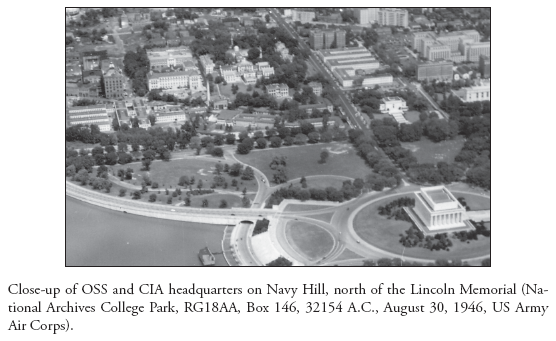

Within days Donovan had offices in the new Federal Triangle “Apex Building” closest to the Capitol; was talking to the Librarian of Congress, the famous poet Archibald MacLeish, about organizing and housing his new research staff of distinguished university professors and other experts; and was recruiting staff from his years at the Department of Justice and from elite New York law firms, Wall Street investment houses, and banks. Within a few weeks, he moved his headquarters into the old navy medical buildings near George Washington University, directly across the street from the site of the post-World War II State Department building, now named for Harry Truman. He also requested an initial budget of $10 million, more than six times what the Bureau of the Budget thought he would need for COI’s first year. Demonstrating Donovan’s ambition, his 1942 budget request was $75 million.

Donovan envisioned a large organization with many functions, although he lost many bureaucratic battles to his implacable Washington enemies. As two OSS veterans remembered, these other institutions—principally the FBI, State Department, army, and navy—“forgot their . . . animosities and joined in an attempt to strangle this unwanted newcomer at birth.”11

The OSS War Report, written in 1946 at Admiral William D. Leahy’s request, noted, “[After Pearl Harbor] . . . many in Washington who did not believe they knew exactly what should be done, at least thought they knew what someone else should be prevented from doing.” After the war, they would again try to kill Harry Truman’s new CIA.12

Once the United States entered World War II, the country’s military leadership structure evolved to meet the burdens of global war. By mid-1942, the war was being managed by a Joint Chiefs of Staff, or JCS, consisting of Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall, Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Ernest J. King, US Army Air Force commander Lieutenant General Henry H. Arnold, and military chief of staff to the president and former ambassador to France Admiral Leahy.13 To defend his new organization from its Washington enemies, Donovan turned to Brigadier General Walter Bedell Smith, secretary of the JCS. The brilliant but irascible Beetle Smith went on to become the indispensable chief of staff to Supreme Allied Commander General Dwight Eisenhower during the conquest of Western Europe, and in 1950, he replaced Hillenkoetter as second director of the new Central Intelligence Agency. President Roosevelt agreed to the transfer of most COI functions to the newly created OSS under the JCS on June 13, 1942, with Donovan as director of strategic services. The very brief order creating the OSS said only that the new organization would “collect and analyze . . . strategic information . . . [and] plan and operate such special services as may be directed by the United States Joint Chiefs of Staff.”14 Saint Louis lawyer Clark Clifford—who, as President Truman’s naval aide and White House counsel, would later play a major role in the creation of the postwar Defense Department and CIA—called the OSS “the most romantic of all wartime organizations.”15

The OSS lost COI’s foreign propaganda function to a new Office of War Information; was never allowed to operate in Latin America, which J. Edgar Hoover considered FBI territory; and never gained the commando or ranger capability so dear to Donovan’s heart. On the other hand, the analytic Research and Analysis (R&A) unit of the OSS flourished. Using the model of the Secret Intelligence Service and wartime Special Operations Executive (SOE)—which Winston Churchill ordered to “set Europe ablaze”—the OSS formed a Secret Intelligence (SI) Branch to recruit and manage foreign spies and a Special Operations (SO) Branch to work with SOE, conduct sabotage, and work with local resistance forces to attack German, Italian, and Japanese forces from behind enemy lines.16 After the war, one early and bitter challenge was to combine these two functions into a single CIA organization, misleadingly called the Directorate of Plans. To arm and equip his officers, Donovan also formed a Research and Development (R&D) branch under the leadership of brilliant chemist and inventor Stanley Lovell. All of Donovan’s ideas and functions survived the war and made up the basis for the modern CIA, as did the far-flung network of overseas offices from which OSS officers operated.

Donovan recognized that America’s only goal was the destruction of the Axis powers, and he drew his staff from all walks of life and all political views, from communists to rock-ribbed conservatives. His psychological screening staff sought men and women with “freedom from disturbing prejudices . . . or racial intolerance” and, for his frontline personnel, officers with “disciplined daring,” who were “calculatingly reckless” and “trained for aggressive action.”17 For training, the OSS turned to its more experienced British cousins— of the Secret Intelligence Service (MI6), Security Service (MI5), and Special Operations Executive,—who, after all, had been fighting the Germans for some time. For the tools of espionage, sabotage, and secret warfare, however, Donovan had his own “Professor Moriarty,” so named for the evil criminal genius of Sherlock Holmes’s adventures. As Stanley Lovell recalled in his informal and darkly humorous memoirs, he met Donovan in his deserted OSS office one evening. The “pear-shaped,” “soft-spoken” Donovan told him:

I want every subtle device and every underhanded trick to use against the Germans and the Japanese—by our own people—but especially by the underground groups of all occupied countries. You will have to invent all of them, Lovell, because you’re going to be my man. Come with me. I had never met a man of such magnetism. I heard myself say: “I will.” He said: “Start tomorrow.”18

Delighted at the idea of throwing “all your normal law-abiding concepts out the window,” Lovell’s scientists, forgers, and chemists created a whole catalog of devices—from knives and silenced guns to clandestine radios and codes used by officers like Virginia Hall, to explosives and chemicals for crippling vehicles and engines, to secret cameras and copying devices for reproducing secret enemy documents.19

According to Lovell, Donovan took a silenced OSS pistol into the Oval Office and fired the bullets into a sandbag while President Roosevelt sat across the room dictating letters to his secretary, without either Roosevelt or the secretary noticing the shots. As recounted by Lovell, Roosevelt’s only comment was “Bill, you’re the only . . . Republican I’ll ever allow in my office with a weapon like this.”20 Perhaps his most devilish device was a substance with a “violent, repulsive, and lasting odor” that “patriot” Chinese children could squirt on Japanese officers to “create disturbances, attack morale, and divert attention.” It was called “Who, Me?”21

The Scholars of the OSS

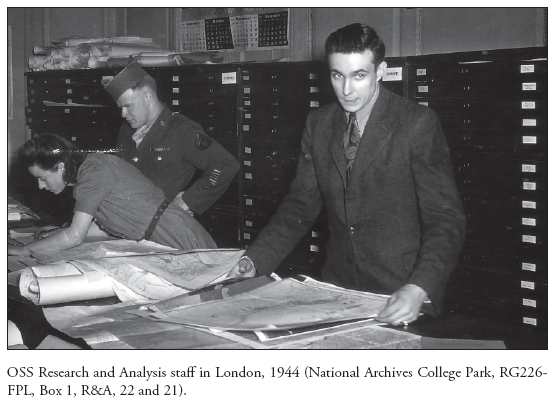

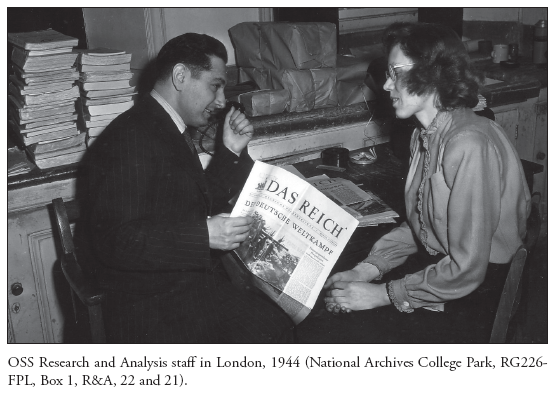

Perhaps most important, for the first time in American history, Donovan’s new creation rallied the social science skills housed in the faculties of America’s great universities. Critics of Donovan and his OSS accused the organization of being made up of his “Oh so Social” circle of Wall Street bankers and fancy big-city lawyers, but in fact, “Donovan . . . had a high regard for professors, placing them above diplomats, scientists, and even ‘lawyers and bankers.’” He loved taking their studies to Roosevelt on his many visits to the White House.22 For the first time, the president now had a group of highly intelligent and experienced experts free of army, navy, or State Department loyalties, policy preferences, or prejudices, who were able to give Donovan, the president, and other national civilian and military leaders the impartial results of their study and research without having to defer to the policy positions of cabinet secretaries or military leaders.23 This independence would remain one of the proudest characteristics of the analysts of the Central Intelligence Agency.

Like all experienced researchers, Donovan’s professors in this Research and Analysis office began their work by reviewing the files of the existing intelligence offices in the army, navy, and even the State Department. Not surprisingly, they were “appalled” by the “haphazard and indiscriminate” official files but understood that secret information stolen by spies or reported by attachés is only a very small part of the information required by intelligence analysts. In fact, only 5 to 10 percent of such raw information came from the “daring, courage, good luck, and tenacity” of the intelligence collectors assembled by Donovan in his Secret intelligence organization, and that is probably still true today.24

Fortunately, R&A experts had perfected their analytic and writing skills in long years of graduate study and academic life, and thus did not need the specialized military training given other OSS personnel. They did need data, however, and a worldwide network was set up to collect thousands of books, magazines, and newspapers, especially from within enemy countries. Because Donovan had a secret budget, he was able to hide the cost of buying all this material and shipping it back to Washington. In 1943, one overseas office alone was sending twenty thousand pages a week to R&A. Although the Germans tried to stop this flow of essentially “public” information, by the end of the war, OSS had accumulated some fifty thousand books and three hundred fifty thousand foreign magazines and newspapers.25 Ironically, Donovan’s insatiable researchers were often frustrated by their own American colleagues. Although Hillenkoetter’s Pearl Harbor naval intelligence officers used decoded Japanese naval radio signals to warn of the attack on Midway Island and to plot Admiral Yamamoto’s fatal flight plan, this priceless MAGIC information and the ULTRA intelligence produced from German Enigma code machines was not shared with R&A.26 Similarly, while Hillenkoetter’s analysts learned much from interrogating Japanese prisoners of war, the OSS SI collectors withheld most of their secret reports, especially prisoner interrogations, from their analytic colleagues.27

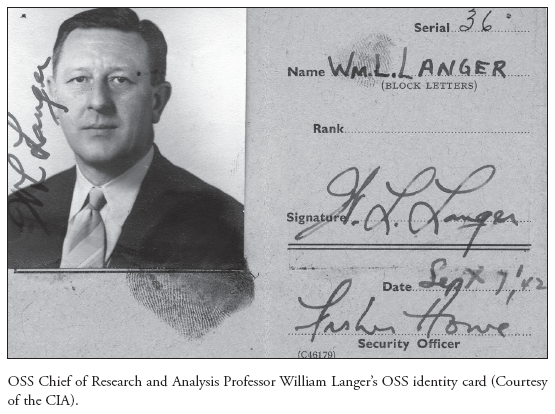

Analysts complained bitterly to the chief of R&A, distinguished Harvard University historian William Langer. In one remarkable case, a “super-secret” report on the organization of the German army in Russia, supposedly received from General Charles de Gaulle’s exile “Fighting French sources,” turned out to have been an official Soviet press release published some time earlier in the New York Times.28 The problem with spies like the French source is, of course, the need to trust them, especially if they claim to have unique access to very sensitive secrets. In most cases the SI intelligence collection officers were not experts on the information the spies were reporting, nor could they be expected to have deep knowledge about everything that OSS knew on any given subject. On the one hand, collectors, whether in OSS/SI or the later CIA Directorate of Plans, did like to believe that their spies were giving them valuable information of critical importance to the war effort, and they liked to think that they themselves were good enough judges of character to recognize if their spies were lying to them.

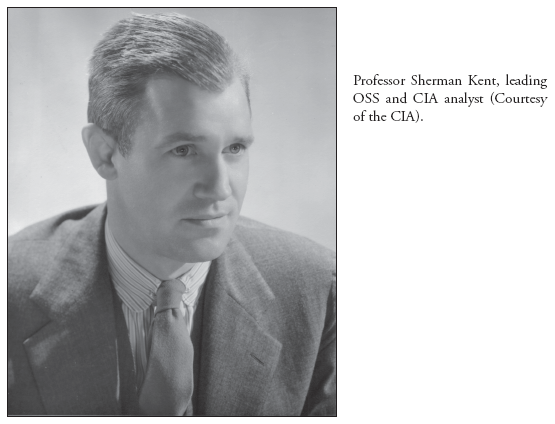

Historians, on the other hand, know very well that much information and many “facts” are wrong—or at the very least incomplete—and that people frequently seek to deceive. They thus put great store in trying to find out exactly where every fact comes from and in recording exactly how to know whether something is true. They want to know exactly where a source learned his information and whether that source had been reliable in the past. They are also accustomed to building great libraries and files—organized so that information can be quickly retrieved—and their goal, in the words of leading OSS and CIA analyst and Yale University history professor Sherman Kent, is “To know everything.”

In the case of the Fighting French information, R&A carefully watched Soviet press releases about German forces and knew that this “super-secret” information had been published in American newspapers. This was by no means the only time that spies misled intelligence officers, and where possible, the OSS and later CIA emphasized what analysts call “original source material” like enemy documents such as the Japanese diaries, maps, and other materials captured on Guadalcanal and other war zones. In cases where spies were placed high in enemy governments, they were often ordered to either photograph the original documents themselves or, if possible, give their OSS managers original documents.

By the end of the war, R&A had grown to a staff of fifteen hundred in Washington, with a further four hundred fifty abroad in such field offices as London, Paris, and Stockholm. They had produced over twenty-five hundred reports and studies.29 Most of R&A’s experts were either historians or economists, but since the focus of their studies was enemy countries in the midst of a global world war, they learned the urgency of working accurately and quickly to produce broad “area studies” needed by military commanders as well as political leaders. They also learned to focus on the very practical matter of using their training and skill to win the war. R&A economists, for example, carefully studied German transportation and industrial production to recommend where American and British strategic bombing could best be targeted to cripple the German war effort.30 The R&A’s first great challenge, which established its reputation for speed and accuracy, was the first Allied counterattack against the Germans: Operation TORCH in North Africa.

As recorded earlier by American diplomat Robert Murphy, Paris naval attaché Hillenkoetter had identified French North Africa as a promising area of Allied attack, and President Roosevelt had dispatched Murphy to develop a network of American offices and relationships with local French authorities. Murphy’s vice-consuls, joined by more of Colonel Eddy’s OSS officers, turned North Africa into the “most impressive” source of intelligence on the French military, but organizing effective resistance to the Germans proved much more difficult. As one vice-consul complained, “We worked . . . with what we had,”31 and what they had were warring groups of conservative anti-republican royalists, Nazi sympathizers, supporters of arrogant General de Gaulle’s Fighting French, and other assorted underground factions. All hated the British for “abandoning” France in 1940 and destroying the French fleet at Mers-el-Kébir on the coast of Algeria, and all of them feared their restive, Arab Moroccan, Algerian, and Tunisian colonial populations. And all of them begged Murphy and Eddy for funds and weapons.

Eddy, as a renowned Middle Eastern expert, thought an American invasion of North Africa would face only “token resistance,” and Donovan budgeted $2 million for an armed underground uprising timed for the American landings. Two OSS officers even organized an irregular Arab army of ten thousand men, but the plan to arm colonial peoples alarmed the French and British and was rejected by Murphy. While OSS officers in North Africa were busy preparing to welcome General Eisenhower’s army, Langer’s R&A Europe-Africa analysts, led by expert in French history Sherman Kent, produced in fifty hours of around-the-clock work an “encyclopedic report” on Morocco, followed within two and a half weeks by comparable reports on Tunisia and Algeria. The military was impressed, and Donovan praised R&A for its “first victory.”32

The Shadow Warriors of the OSS

Unfortunately, the first American invasion of the European war, on November 8, 1942, did not go nearly as smoothly. Underground groups in Morocco and Algiers, supported by the OSS, arrested Vichy officials and seized key locations, but the British Royal Navy had landed Eisenhower’s troops in the wrong locations, and pro-Nazi authorities overwhelmed the underground forces before the Americans could reach them. Famous French general Henri Giraud, whom the Americans hoped would join them, refused to do so unless he, instead of Eisenhower, was given command of the TORCH army. Finally, after several days of fighting and the loss of hundreds of American and French lives, Hillenkoetter’s old contact, Admiral François Darlan, now commander in chief of all French armed forces, ordered French forces to cease fire—but only after German troops invaded Vichy France. As Eisenhower’s deputy, newly promoted Lieutenant General Mark Clark announced in great frustration, the “yellow bellied [French] sons of bitches” finally reached an agreement with American forces under which Darlan was to become chief of French North Africa.33 The fighting allowed the Germans enough time to occupy Tunisia, and Darlan was assassinated by a young French royalist on Christmas Eve 1942.

Donovan’s “calculatingly reckless” young SI and SO officers might have been chosen for their “ability to get along with other people,”34 but in North Africa—and later in Italy, the Balkans, France, China, and Southeast Asia—they were thrown into political, ethnic, or religious situations that had festered for decades or, in some cases, hundreds of years. Most of the world had not enjoyed America’s and Great Britain’s representative democracy, and Germany, France, Italy, and Eastern Europe had been torn by decades of political and even physical battle among those who supported monarchs, those who wanted a communist workers’ paradise, and a wide range of groups in the middle who wanted various types of democracy or liberty. Adolf Hitler had risen to power in Germany in 1933 out of exactly that sort of political turmoil.35 Many OSS officers were refugees from these struggles, especially those European Jews who escaped anti-Semitism. Most other Americans were just as impatient with obscure kings or sectarian squabbles, and unsympathetic to the idea of protecting or restoring European empires. Trained for aggressive action, and often living with and growing to respect and admire their local underground allies, few OSS personnel worried about their hosts’ political views as long as they were effective fighters, and few hesitated to express their own democratic sentiments, regardless of American diplomatic or military strategy—beyond the shared strategy of destroying Nazi Germany and imperial Japan. In Yugoslavia, for example, OSS officers often found communist partisan leaders hostile and obstructive, despite the tens of thousands of tons of supplies and munitions supplied to them. Finally, after unsuccessful attempts to deal with communist leader Josip Broz Tito’s representatives, a frustrated OSS officer wrote “urgently suggest you . . . deal with the horse’s mouth instead of wasting time at the other end.”36

Another equally frustrated OSS officer, also speaking of the fighting between rival groups in Yugoslavia but making a universal point, wrote:

I personally do not feel I can go on . . . unless . . . every possible honest effort is being made to put an end to the civil strife. It is not nice to see arms dropped by . . . our airmen . . . be turned against men [who help us.] It is not pleasant to see our wounded lying side by side with the men who rescued . . . them—and to realize that the bullet holes . . . resulted from American ammunition fired from American rifles dropped from American aircraft flown by American pilots . . . . The issues in Yugoslavia . . . will have to be faced in many parts of the world. The Yugoslavians . . . have abandoned reason and resorted to force. Is this the shape of things to come? Are we all of us sacrificing to end this war only to have dozens of little wars spring up which may well merge into one gigantic conflict involving all mankind?37

Sadly, Yugoslavia would indeed prove to be one of the first pressure points of the long Cold War in which the new CIA became engaged, and after Tito’s death, the country became one of the first great intelligence and military challenges of the post–Cold War world in the 1990s.

Their battle-hardened British mentors and allies often regarded the Americans as hopelessly naïve as well as pushy, and tried to control their activities. Like other Europeans, the British had long experience with secret activities and intrigues, and beyond that had been learning painful lessons for two years in the war before the OSS showed up. The British were happy enough to teach espionage, unconventional warfare, and sabotage and subversion skills in Special Operations Executive (SOE) training facilities, which Donovan then replicated and expanded in the United States near Washington, DC, and elsewhere, but they considered themselves the senior partners. Accordingly, the British tried to limit OSS activities and areas of operation, and even demanded that two-thirds of the mostly American support, supplies, and transport be committed to secret operations. Donovan and his officers, naturally aggressive, took a much broader view of America’s areas of interest and sometimes suspected the British of violating hard-won agreements.38 Only in October 1943, over the objections of the US Army in London, did OSS get JCS approval to conduct the kind of independent espionage that would be a hallmark of the CIA.39 Even in the midst of great global war, individual prejudices and animosities were just as prevalent on the front lines as in the military commands or bureaucratic corridors of Washington or London.

France

Although the Allies were fighting a global war, Germany was the primary target and France the battleground recognized to best ease the pressure on the Soviet Union and lead directly to victory in Europe. As early as May 1943, Allied planners agreed to invade France, a decision approved by Roosevelt and Churchill in Quebec in August. By then the British had been operating spies in France for some time, as had the French themselves—and even the Poles.40 American activities were constantly hindered by MI6 deputy Sir Claude Dansey, a “crusty old spirit” who repeatedly demonstrated “unnecessary combativeness and severe criticism of all things American.”41 He was especially protective of his own agents inside France and worried that American activities might expose or threaten his people. The French in exile in London were equally hostile, and while de Gaulle resented British actions dating to the fall of France and destruction of the French fleet, he also resented US support for Admiral Darlan and General Giraud in French North Africa. As later reported by William Casey, the British Special Operations Executive’s goal was to

encourage and enable . . . [the harassment of] the German war effort at every possible point by sabotage, subversion . . . raids, etc, and at the same time build up secret forces . . . organized, armed, and trained to take their part only when the final assault began.42

There were many inside France willing to help, especially after Germany invaded the Soviet Union and French communists turned against the Nazi occupiers. Beyond that, Germany’s plans to “draft” French workers for factory labor in Germany caused many thousands to flee to the mountains or forests—where they lived in hidden camps and were very receptive to SOE or OSS officers, who joined them with promises of training and weapons. Despite their retreat at Dunkirk in 1940, the British never really left France, and the SOE was very active. The first OSS officers arrived in June 1943, a year before the planned invasion across the English Channel, and by April 1944 French OSS agents, organized by eighty-five OSS personnel, were reporting to London by radio.

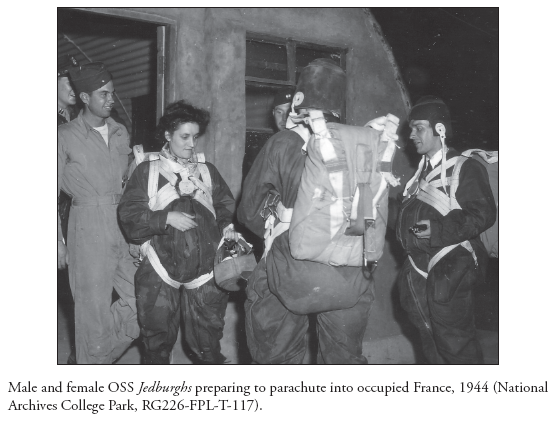

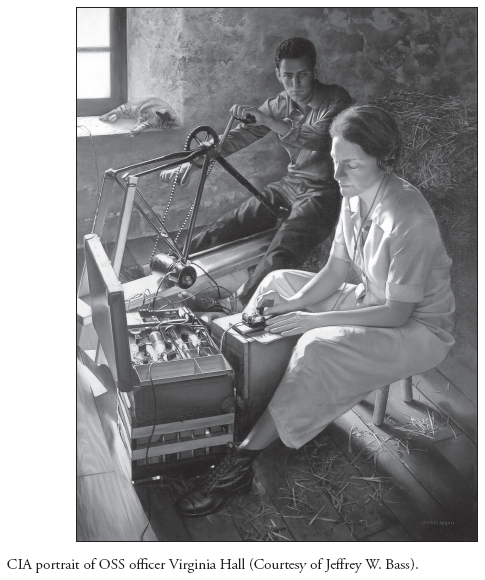

After the Operation OVERLORD D-day invasions on June 6, 1944, Jedburgh teams—made up of British, American, and French officers—parachuted into France to rally, arm, and train as many as three hundred thousand resistance fighters and to try to coordinate their activities with the invading Allied armies.43 Among the brave American OSS officers who prepared the way for the Allied invasion was an extraordinary woman named Virginia Hall, whom the French and Germans called “the woman who limps” because, like Colonel Eddy, she had an artificial leg.

From a wealthy Baltimore family, Hall studied in Europe and was fluent in French, German, and Italian. Athletic and adventurous, she served as an American embassy clerk in Warsaw, Vienna, and Turkey, where she lost a foot in a hunting accident. Because she was dismissed as a “crippled” woman, the State Department would not make her a diplomat, so when World War II broke out, she joined the French ambulance service until German victory in 1940. Recruited by SOE, she returned to Vichy France in August 1941 undercover as a neutral American reporter for the New York Post, setting up resistance networks just after Commander Hillenkoetter left the American embassy to return to sea duty. Beyond recruiting French agents and supplying them with training, money, and weapons, she helped escaped prisoners of war and downed airmen get out of France. After the American invasion of North Africa and the German occupation of Vichy France, she herself escaped by hiking across the rugged wintry Pyrenees mountains into Spain. The OSS sent her back to France in April 1944 to help prepare the French resistance for the great June OVERLORD invasion. The German Gestapo knew her from her SOE activities, so using false identity documents, she disguised herself as a weathered farm woman or cowherd so she could watch German troops and scout areas where the OSS could secretly drop supplies or weapons to her fighters.

In all, by moving constantly to avoid capture, she received fifteen airdrops, and in the month after Bastille Day, she transmitted thirty-seven reports back to London by secret radio. Originally helped and protected by thirty French fighters, she was joined by a joint OSS-SOE Jedburgh team after the Operation DRAGOON landings in southern France, and together they trained and equipped three French battalions that killed one hundred fifty German troops and captured five hundred prisoners. For her wartime heroism, she was made an honorary Member of the Order of the British Empire and, in September 1945, became the only civilian woman awarded a Distinguished Service Cross for World War II service.44

It’s estimated that there were between one hundred thousand and three hundred fifty thousand resistance fighters inside France, but unfortunately, they were not always as effective as their numbers might suggest.45 It was not only the British and Americans who were sometimes hostile to one another; the French were as well. As one Frenchman admitted, the resistance was plagued by a

nasty climate of constant and futile argument, frayed nerves, and hair-trigger tempers. [The OSS] declared with some vehemence that the only thing that interested them was that we fight the war . . . it made not the slightest difference to them whether we were partisans of one French general or the other.46

Beyond the petty infighting between factions, all of which demanded more and more weapons and supplies, the Allies worried that the rival resistance groups, especially the communists, were stockpiling weapons to fight their French rivals once the Germans were defeated.

Everyone who knew William Donovan considered him fearless, although his mild demeanor and pudgy appearance were sometimes deceptive. His senior representative in London was David Bruce, the multimillionaire son-in-law of steel magnate Andrew Mellon, who in later years was a distinguished American ambassador. Donovan originally asked Bruce to create the OSS Secret Intelligence organization, and when Bruce protested that he knew nothing of espionage, Donovan dismissed the protest by remarking, “Nobody else does.”47 In a meeting witnessed by Bruce with the American military intelligence chief in London, who made it obvious he didn’t “trust General Donovan or his ideas,” Donovan quietly responded, “Unless the general apologizes at once, I shall have to tear him to pieces physically and throw his remains through these windows.”48

Clearly, even direct orders from Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal could not keep a man like Donovan from joining the D-day invasion, and he even wore his Medal of Honor ribbon as he and Bruce went ashore on the Normandy beaches. Belatedly realizing the foolhardiness of putting Roosevelt’s chief of centralized intelligence at risk of capture as they came under German machine-gun fire—and discovering he had forgotten his OSS suicide pill—Donovan told Bruce: “David, we mustn’t be captured, we know too much . . . . If we are about to be captured, I’ll shoot you first. After all, I am your commanding officer.”49 The postwar OSS report called this kind of recklessness by senior officers who knew the ULTRA secret “clearly outrageous” and “simply not professional behavior.”50

The Germans were initially paralyzed by the Normandy D-day landings, since the British had mounted a massive deception campaign to convince them that the “main attack,” to be led by General George Patton’s American army, would land farther north. As William Casey wrote, fifteen hundred people working on the deception program held down over two hundred fifty thousand German troops in twenty-two combat divisions. French saboteurs cut telephone and cable lines between Paris and Berlin, forcing the Germans to communicate by radio so that Allied code-breakers could listen in on the strategic debate between Field Marshal Hans von Kluge and Hitler about the best response to the Allied invasion.51 On July 20, with the Battle of France still raging, senior German military officers tried to assassinate Hitler. Von Kluge, associated with these anti-Hitler officers, was recalled to Germany and committed suicide on August 17, two days after American troops landed in southern France in Operation DRAGOON, and as the Allies were nearing Paris.

David Bruce stayed with or ahead of American forces as they advanced toward Paris. Indeed, the American and British advance was often so rapid that the OSS and SOE struggled to put enough Jedburgh teams in front of them to rally French resistance and collect intelligence on the retreating German forces. In mid-August the Red underground of twenty-five thousand armed men rose up against the German occupation troops in the city, but de Gaulle’s generals delayed dropping arms to the communists. At that time Bruce was twenty miles ahead of General Patton’s army and noted in his diary: “It is maddening to be only thirty miles from Paris.” Bruce and his new OSS officer Ernest Hemingway got a rude reception by French General Philippe Leclerc, commanding the Free French division chosen to have the honor of liberating Paris. As Hemingway recalled, Leclerc greeted them with an expression that the famous writer translated as “buzz off, you unspeakables.”52

The American OSS officers were nonetheless welcomed by Parisians “almost hysterical with joy.” On August 25, 1944, after surveying the last fighting from the top of the Arch of Triumph, Bruce and Hemingway toasted the liberation of Paris with martinis at the Ritz hotel. Bruce moved his OSS headquarters from London to Paris for the final push toward Germany. Speaking of the French agents and resistance fighters with whom they worked, fought, and sometimes died, one OSS officer said, “These are the kind of people worth respecting and the hell with the ones who were busy denouncing each other . . . to get political power.”53 Casey agreed, concluding that France liberated itself: “[Outside the area of the Normandy invasion] the huge area south of the Loire and west of the Rhone, as well as Paris, were liberated entirely by the [French] people and the FFI [French Forces of the Interior].”54 Aside from Casey himself, another future director of the CIA, William Colby, led a Jedburgh team reporting on and harassing the German retreat.

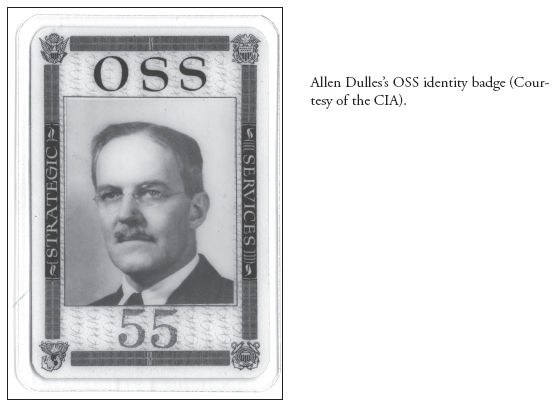

Allen Dulles and the Penetration of Germany

The American invasion of southern France in August 1944 offered Allen Dulles, the OSS representative in Switzerland, his first opportunity to leave that small, neutral country—totally surrounded by Axis armies—since he had quietly ridden a train from Vichy France just a few days after Eisenhower’s American troops landed in French North Africa in November 1942. The grandson and nephew of secretaries of state, Dulles had been a junior diplomat in Switzerland during World War I and later served at the Versailles Peace Conference and the American embassy in Berlin. Like Donovan, Dulles had become a prosperous New York lawyer. He toured Europe in 1933 as the Nazis and Italian Fascists were consolidating their power, even meeting and interviewing Hitler.55 Having known Donovan while he was assistant attorney general, Dulles had, in January 1942, been offered the job of opening the Coordinator of Information’s New York City office, where he worked on research and operations against Germany. Offered the position as David Bruce’s OSS deputy in London, Dulles modestly but slyly asked for a “less glamorous post”—where he would be his own man, away from huge bureaucracies and Allied intrigues—and was given Bern.56 In fact, as Dulles knew from his World War I experience—and as the OSS war report stated—“in both World Wars, Switzerland was the main Allied listening post for . . . European enemy and enemy-occupied countries.”57

Over the next years he approached every American citizen living in Switzerland, most of whom agreed to help collect information on Germany and introduce him to the many enemy officials who visited Switzerland, as well as to the wide variety of anti-Nazi émigrés living in the small, neutral Alpine country. Dulles used the unconventional but very effective approach of calling himself President Roosevelt’s special representative for Europe and working out of his apartment rather than the American embassy, so visitors could meet with him unnoticed. Soon anti-Nazi officers of Admiral Wilhelm Canaris’s military intelligence organization, the Abwehr, approached him with the message that they hoped to overthrow Hitler and make a separate anti-Soviet peace with the United States and Great Britain. Heinrich Himmler—who, as head of Nazi security forces, including the SS and Gestapo, was Canaris’s bitter rival—also began making overtures to the OSS after the German defeat by the Russians at Stalingrad in February 1943. Similar German messages also went to another “special Roosevelt representative” in Stockholm, OSS officer Abram Hewitt, but both American and British senior officials rejected these anti-Hitler, anti-Soviet overtures out of worry that their suspicious and paranoid Soviet ally, Joseph Stalin, would discover these discussions and think the Western Allies were double-crossing him.58 Despite early assassination attempts in March 1943, and the spectacular bombing of his headquarters in July 1944, Hitler survived and ordered the killing of thousands of opponents, including Admiral Canaris. Himmler never dared to abandon him until the Russians entered Berlin, at which point he fled westward until captured by the British army.

Dulles also received a number of volunteers, including Nazi foreign ministry official Fritz Kolbe, known as “Wood,” who was allowed to visit Bern periodically as part of his official duties.59 Kolbe gave the OSS some sixteen hundred documents, primarily messages from German military attachés in some twenty countries. Anti-American British MI6 deputy Sir Claude Dansey doubted the authenticity of these stolen documents, but their accuracy was confirmed by ULTRA Abwehr intercepts.60 As the OSS discovered after receiving supposedly supersecret Russian information—which the Free French had gotten from Soviet press releases and the New York Times—it is always prudent to confirm spy information from other sources. It is also wise to get secret information using the least risky method, and in this case the ULTRA material would have saved Kolbe from the very real danger of stealing German foreign ministry telegrams and smuggling them to Dulles in Switzerland, if Dulles or OSS R&A had known about ULTRA.

Ironically enough, the OSS office most intimately aware of ULTRA was X-2, the counterintelligence branch charged with catching foreign spies and protecting American secrets. In one of the great successes of military and intelligence history, at the beginning of the war in Europe, the British Security Service had captured the German spy network in England and had begun using captured German radio operators to send false and misleading reports to Berlin. Because this deception was managed by the so-called Twenty (XX) Committee, led by John Masterman, the entire process became known as the Double-Cross System.61 Much of the information used to identify enemy spies—and confirm that the British deception was working and that the Germans believed the false reports from their spies inside England—came from ULTRA. Indeed, as one historian wrote, “The principal by-product of ULTRA was counter-intelligence.”62 Once the British shared both the Double-Cross success and the ULTRA secret with their American allies, it was decided that OSS/X-2 counterintelligence officers would employ decoded German messages to identify and capture German spies throughout Europe, and that special X-2 officers serving with American military commands would be responsible for safeguarding ULTRA and delivering this critical intelligence to army commanders. Only after the formation of the CIA would intelligence analysts and managers have routine access to such valuable communications intelligence, known as COMINT.

In neutral or occupied countries, the Allies were able to identify and work with local sympathizers, but both the OSS and British service saw the penetration of Germany “as an exceedingly difficult task, with a high casualty rate . . . expected.” In fact, Germany had become so disorganized in the months before surrender—with hundreds of thousands of foreign workers and eastern Volksdeutsche ethnic German refugees fleeing from the advancing Soviet armies—that the spies had a “surprisingly low” casualty rate.63 In the last nine months of the European war, thirty-four teams were safely parachuted into Germany, with seven using a remarkable new secret communication system called Joan-Eleanor (J-E), named after the wives of the inventors. Most OSS operators, including Virginia Hall, relied on bulky radio sets in suitcases, which demanded the use of codes and were subject to German detection and location. In late 1944, however, a two-part J-E high-frequency radio was invented. It was made up of a small, lightweight handset on which teams on the ground could talk directly to their managers in a specially equipped small British Mosquito airplane thirty thousand feet overhead, without being noticed by German security forces.64

In the final weeks of the war in Europe, the OSS had already begun planning for the occupation of Germany. Research & Analysis scholars were drawing up handbooks for the anticipated future Allied military government, compiling lists of Nazis to be arrested and anti-Nazi Germans who could serve in the new democratic German government. Professor Kent thought that the idea of bringing senior Nazis to trial, as was later done in the Nuremberg War Crimes Trials, was a waste of time, and wrote in his journal that the Allies should “simply single out the several hundred Nazis about whom there could be no doubt as to guilt, beginning with Hitler, and summarily execute them.”65

Many OSS agents with forged papers from Stanley Lovell’s R&D branch, wearing authentic German clothing, were penetrating Germany, with some of them even operating in Berlin.66 Nazi officials were still trying desperately to halt the Russian advance on Berlin and the Soviet domination of Eastern Europe by making a separate peace with the West. SS General Karl Wolff, who commanded German army forces in northern Italy, undertook talks in Switzerland with Dulles to surrender his forces and prevent Yugoslav communist Josip Tito’s Red partisans from capturing the northern Italian port city of Trieste.

The Wolff initiative caused great concern about Russian reaction. Eisenhower’s chief of staff General Walter Bedell Smith rebuked the OSS European chief, and Roosevelt’s military chief of staff, Admiral Leahy, summoned Donovan to the White House for an explanation of Dulles’s actions.67 Stalin bitterly accused the West of making a separate anti-Soviet peace, and on April 4, 1945, President Roosevelt wrote him a stern response: It would be one of the great tragedies of history, if, at the very moment of victory now within our grasp such distrust, such lack of faith should prejudice the entire undertaking after the colossal losses of life . . . and treasure involved.68

A week later Roosevelt had died, and Harry S. Truman was president. A month later, on May 8, 1945, the war in Europe ended.

At the end of the European war, Donovan rejected the suggestion that Dulles be made chief of OSS Europe on the grounds that he was a “poor administrator” but appointed him chief of OSS Germany, largely because in Bern his “exceedingly small staff . . . succeeded in producing the best OSS intelligence record of the war.”69 Many experienced officers were already being transferred from Europe to the war still raging in Asia, and Dulles was put in charge of denazification. Sterling Hayden, an OSS officer who earned a Silver Star in Yugoslavia and went on to have a long and distinguished acting career, bitterly noted “the real anti-Nazis were dead, in exile, or in . . . Auschwitz, Buchenwald. Names we thought at the time . . . would teach us a lesson we’d never forget.”70

The Soviets quickly returned Walter Ulbricht’s German communists from their Russian exile and began establishing puppet governments in the territories occupied by the Red Army. As a disappointed OSS officer later recalled:

Those were still days when we thought four-power cooperation might work, first in Germany and then . . . [at] the United Nations. Berlin is perhaps where that hope was first shattered . . . where we tried to make it work in a real situation.71

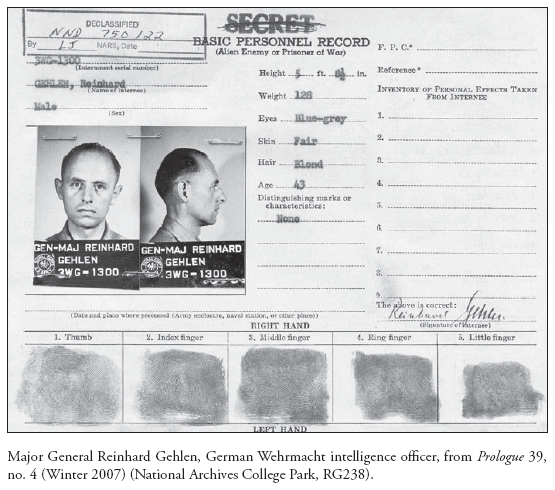

In the chaos of the collapse of Nazi Germany, the German military intelligence officer responsible for operations against Russia, Major General Reinhard Gehlen, hid his files and offered his services, and those of his experienced intelligence officers, to the United States.

This so-called Gehlen Organization, which later became the foundation of the Cold War German Federal Intelligence Service, continued its espionage operations in Soviet territory under the supervision of OSS officers Frank Wisner and Richard Helms, yet another future director of central intelligence.72

Asia

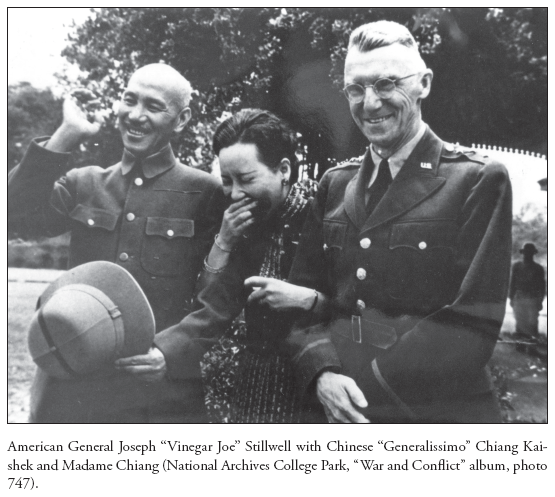

While most OSS activities in Europe were in support of large-scale military operations, in Asia the American military presence was relatively small, and OSS concentrated on rallying local populations for guerrilla and paramilitary operations.73 The combat-hardened European veterans who joined their OSS colleagues already working in Asia found that the resistance groups fighting the Japanese were plagued with the same internal political strife that had complicated their operations in France, Italy, and the Balkans.74 Beyond the rivalries among nationalists, communists, and, in China, even local warlords, however, the Americans found that almost all the local populations were deeply suspicious of the Western imperial powers of Great Britain, France, and even Holland. And those powers, especially the British and French, were equally suspicious of the OSS for its willingness to work—and in many cases sympathize—with local anti-colonial groups. When British Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten, a great-grandson of Queen Victoria, Empress of India, was made Allied commander in chief of the South East Asia Command (SEAC), Americans suspected he was focused on restoring the eastern empire, but he proved more supportive than General Douglas MacArthur, who barred the OSS from the Pacific theater, or army General Joseph “Vinegar Joe” Stillwell, who had the thankless job of dealing with the corrupt and incompetent Chinese Nationalist “Generalissimo” Chiang Kai-shek. Although officially Chiang’s deputy, the sharp-tongued Stillwell called him a “peanut dictator,” “an ignorant, arbitrary, stubborn man” who, with his “merry nest of gangsters,” ruled China based on “fear and favor.”75

Despite his justifiably sour disposition and his suspicion of unconventional guerrilla warfare, Stillwell did give OSS Detachment 101 a free hand to conduct anti-Japanese operations in Burma, telling them, “All I wanted to hear was ‘Booms’” from the jungle. Lord Mountbatten was equally supportive, although some of his officers thought that “OSS would give undue encouragement to the aspirations to freedom of the subject peoples in Asia.”76 Det 101 Burma activities were considered “the most successful OSS guerrilla operations of the war,” with just 500 Americans organizing, training, arming, and leading as many as 9,000 Kachin tribesmen, who attacked Japanese outposts, reported on enemy activities, and rescued downed aircrews.77 By 1944 OSS was also working alongside Brigadier General Frank Merrill’s famed Merrill’s Marauders, the only American ground combat troops in the China-Burma-India theater at the time.78 Although the OSS lost 15 Americans, Det 101 rescued 574 Allied fliers while killing at least 5,400 and possibly as many as 10,000 Japanese.79

A number of OSS officers had deep experience in Asia, with some having been Christian missionaries in China and feeling great sympathy for the impoverished long-suffering peasants and frustration at Chinese “disunity, the incompetence, the half-hearted . . . Chinese war effort.”80 As with General de Gaulle in France, Chiang’s Nationalists too often seemed more concerned with saving their strength and stockpiling weapons to fight Mao Tse-tung’s Red army than with driving out the Japanese. Ironically, because China was officially an ally, the OSS was never able to mount successful operations into Manchuria, Korea, and onward into Japan, in large measure because of relentless Chinese Nationalist opposition to OSS activities.81 Neither could OSS operate in areas under the control of Mao’s communists as they could in areas of Indochina occupied by Ho Chi Minh’s Viet Minh. In summary, “OSS became accustomed to profound disappointment in its four years in China.”82 The final disappointment was that by order of President Harry Truman, OSS was terminated on October 1, 1945, just as Donovan was setting up observation stations in eight Chinese cities to conduct “long-range intelligence operations in China.”83 In Thailand, the OSS faced the same challenge, as one Thai explained:

We have been free for over seven hundred years . . . . Why do you think we fear France, Great Britain, and China? Because they are all around us . . . uncomfortably close. We are for the United States because [you have] no territorial ambitions in Asia.84

Although the Japanese dominated the Thai government, that government “became in effect a resistance group working for OSS,” cooperating so extensively that Thai police escorted OSS officers around Japanese-occupied Bangkok.85 Unlike in Europe, where the OSS had to work with underground resistance groups, “there existed in [Thailand] what might best be described as a patriotic governmental conspiracy against the Japanese in which most of the key figures of the state were involved,” including the chief of police, senior generals, the minister of foreign affairs, and the Regent.86 Of course, as patriots, they saw their first responsibility to be to their own country rather than to the United States, a matter that later CIA officers would have to remember in working with “friendly liaison services” or allied governments around the world. And the most powerful incentive the OSS could offer was American support for postwar Thai independence against “suspected British designs.”87

Next door, in French Indochina, the Japanese had left the French Vichy colonial government in place, although the OSS made contact with a frail and skinny revolutionary who called himself Ho Chi Minh and led the communist underground group known as the Viet Minh. Ho’s fighters passed to the OSS intelligence about Japanese forces and helped rescue downed Allied pilots. The French, who wanted to restore their African and Asian empires, considered Ho “cunning, fearless, sly, clever, powerful, deceptive, ruthless—and deadly.” His OSS contacts, in contrast, regarded him as “much more a nationalist than a communist,” a “true patriot” who spoke American English after working as a waiter in New York and Boston, a man who loved to question them about the American Declaration of Independence. Ho “was convinced that America was for free, popular governments all over the world, that it opposed colonialism.” Roosevelt seemed to encourage that view when just before his death he said, “[Indochina] should never be simply handed back to the French to be milked by their imperialists.”88

After the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki by atomic bombs in early August 1945, the Viet Minh rose across Vietnam and took control of Hanoi—although at the Potsdam Conference in July, Joseph Stalin, new president Harry Truman, and new British prime minister Clement Attlee agreed that the British should “liberate” southern Vietnam, while Chiang Kai-shek’s Chinese Nationalists would do the same in Hanoi. An OSS team was the first to arrive in Saigon, followed shortly by British Indian Army General Douglas Gracey, who immediately imposed martial law and a curfew. In response to a general strike, Gracey armed the remaining French colonial troops, who brutally attacked Vietnamese civilians. In the ensuing Vietnamese retaliation, Gracey organized Japanese soldiers to fight alongside the British and French in a bloody “war of extermination.” As a bitter observer noted, “The conclusion is inevitable that the French have learned almost everything under Hitler except compassion.” Gracey ordered the OSS commander, a twenty-eight-year-old Chicagoan, Major A. Peter Dewey, out of the country, but he was killed at a Viet Minh roadblock by fighters who apparently mistook him for a Frenchman.89 Dewey, who had parachuted into France in preparation for Operation DRAGOON, was the first American killed in what was to become a bitter thirty-year war between the Vietnamese and Western powers. In the north, the OSS escorted Ho Chi Minh to Hanoi, where he declared Vietnamese independence based on the model of the American Declaration of Independence and appealed for American support and investment. His OSS escorts were met by another team of OSS and French officers, and as the senior French officer observed, “We seemed to the Americans incorrigibly obstinate in reviving a colonial past to which they were opposed.” A Chinese army arrived in mid-September and looted Hanoi before returning north.90 French General Philippe Leclerc, the liberator of Paris, replaced Gracey in October, and Ho’s Viet Minh began the long underground war that finally drove the French out of Vietnam a decade later.

In China, World War II ended no less chaotically. General Stillwell had finally been replaced by General Albert Wedemeyer, after numerous complaints from Chiang Kai-shek. Wedemeyer argued that US forces should not get drawn in with Chiang’s Nationalists in a civil war against Mao’s communists. Many pro-Japanese Chinese warlords joined the Nationalists, and the OSS found itself caught in the middle. On August 25, 1945, just a week before the formal Japanese surrender aboard the battleship Missouri in Tokyo Bay, OSS officer Captain John Birch was stopped by a group of teenage Red peasant soldiers. Birch was a fundamentalist Baptist missionary who had just joined the OSS in May after serving as an intelligence officer for General Claire Chennault’s pro-Nationalist Fourteenth Air Force, successor to the famed Flying Tigers. According to one account, the furious Birch said: “I want to find out how [the communists] intend to treat Americans. I don’t mind if they kill me, for if they do . . . the United States will use the atomic bomb to stop their banditry.”91 Birch was shot dead, and four years later Chiang’s Nationalists were driven from the mainland as Mao proclaimed the People’s Republic of China.

The Postwar Vision

Well before Germany and Japan were defeated, General Donovan and his staff were already thinking of a permanent postwar national intelligence organization, one based upon the lessons they had learned during the war. As early as August 1942, his deputy, Brigadier General John Magruder, said, “Only a joint national intelligence service can lay bare all the facts and factors upon which a sound national decision can be based.”92 According to the OSS War Report, they “never lost sight of the fact . . . that [the OSS] was . . . an experiment of vital significance which . . . should determine the peacetime intelligence structure for the United States.”93 Most important, from Donovan’s perspective, was preserving the skills and methods that the OSS had developed in analysis, counterintelligence, and espionage. In July 1944 Research and Analysis chief Professor William Langer said there was

no need [to set] up a new secret intelligence and counter-intelligence service . . . because . . . the OSS [is] such an intelligence agency . . . . In short, the solution to the problem in the post-hostilities period is not . . . in further experimentation . . . but rather in the proper development, expansion and full exploitation of the facilities already available.94

Donovan saw unconventional propaganda and military operations as primarily wartime functions to be shut down with the coming of victory. In late 1944 the OSS had almost 13,000 people, including some 4,500 women. In all, about 7,500 served overseas.95 In what the War Report called “typical Donovan [humor],” he teased military commanders that if they couldn’t spare 2,000 or 3,000 troops for some task, he “would send twenty or thirty men to do the job.” Privately, calling himself a “prudent realist,” he admitted it would probably require 50 or 60 OSS personnel.96 Still, with fewer people than a single army division, Donovan had built a service with officers and bases covering most of the world, along with support and administrative staffs to fund, train, and supply worldwide intelligence and military operations. He had also accumulated a number of enemies.