The Science of State Formation in Diabetes Research

Anchored at the hub of the consortium at the University of Chicago, I followed the use of DNA data through the pathways of collaborative research. I learned from Nora and other consortium members that the main data set that Nora had been working on came from a Texas researcher who had been gathering DNA and anthropometric data from Mexicana/o families for decades. There were more than ten thousand individuals in this data set, all of whom came from one South Texas area and its northern Mexican counterparts. At Nora’s suggestion, I contacted the researcher and scheduled the first of many visits to his field office and the surrounding community.

I arrived on a clear but hot May morning and met Carl, the principal investigator, at the airport. Carl coordinated my visit with one of his own: his labs are based in a large urban research university. As a gesture of thanks for introducing me to his field office, I offered to drive from the airport to the field office an hour away. We drove along the Rio Grande to “Sun County,” the (fictitious) jurisdictional name1 of the Texas side of the area he has sampled for nearly three decades. During the drive, I queried Carl about the sampling operation, about the community, and about the consortium. Before we arrived at his field office, we took one detour to view a place along the river where for centuries people, goods, and livestock had crossed the Rio Grande. Veering off the freeway, we followed a two-lane road for several minutes, then pulled onto a remote dirt road. Carl recounted how drug traffickers and coyotes (smugglers of humans) use flotation devices, boats, ferries, and paid swimmers to cross their chemical and human payloads.

As we pulled up to a clearing along the banks, two Immigration and Naturalization vehicles were parked window to window in opposite directions about zo yards from where we stopped. The glare of the sun and tinted windows of the Ford Rangers made it impossible to see the agents. The full-size four-door sedan I had rented made for an awkward moment as I imagined being interpellated by la Migra as a chauffeur with his patron surveying a favored commercial artery. The river was down a 15-foot embankment and was approximately 40 yards wide. We didn’t stay long. After Carl recounted a bit of the history of this particular crossing, pointing to an old cable that had once been part of a crossing apparatus, we left.

We arrived at the field office in time for Carl to treat the staff and me to lunch. I was not expecting the equivalent of a red carpet, but generosity is a defining feature of the sampling field office and staff. I gave a short introduction, and then each staffer explained a little about his or her particular job at the center. I would stay for several days, I told them, and Carl issued a blanket edict that I should be treated well. Carl had a 7 P.M. flight, so about three hours after we arrived, I drove him back to the airport. I exchanged rental cars for a nondescript smaller one and returned to Sun County.

The movement of people, blood samples, and data is a central feature of the diabetes enterprise. Carl’s operation, like the rest of Sun County, does not distinguish between Mexicanos who live in Texas and those who live across the river. Up and down the border, inland a few miles to Carl’s lab, across the four bridges that Carl’s team uses to cross into Mexico, round trips, or “vueltas,” are routine for this sampling effort. Samples are taken from Mexicanas/os in the entire region. Nearly 60 percent of field office time, is spent on vueltas of one sort or another. My life of vueltas would begin the next day.

The field office, in El Camino, is the hub of the field research practices. It is a nondescript one-story converted house in a residential area about four blocks from the highway. A routine day at the field office begins around 7 A.M. My first day there, I meet the center office manager, Judi, and two staff members, Rosa and Virginia. We board a late-model mini-van emblazoned with the university logo and drive north zo miles to the next town. Once in town we turn left at the second stoplight, one of four on this highway. Five hundred feet later we enter the point of no return before crossing the U.S.-Mexico border. Judi and Virginia fumble for the spare change they keep in a urine specimen cup in the utility compartment of the van. “I hope that is not recycled,” I chide. Chuckling, Judi hands the 75 cents to the border official who glances at the van’s passengers, exchanges morning greetings, and waves us across the bridge. As in all bottlenecks, our early-morning passage prevented much delay.

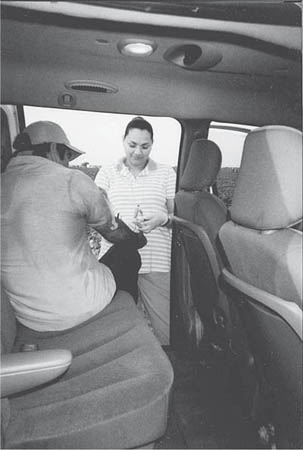

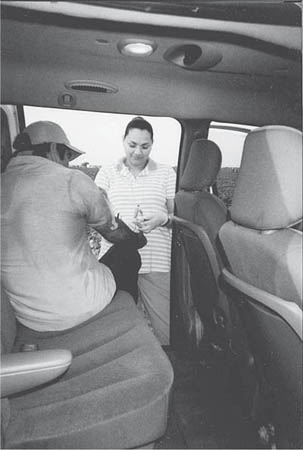

FIGURE 4. Field office staff collecting blood samples from a field worker. Photo by the author.

We proceed through the pueblo toward addresses Judi and Virginia know almost by heart. We stop to ask for directions and eventually retrieve Señor Zambrano and, after about an hour of driving, we collect Señoras Lopez and Espinoza from their respective homes. In the preceding vuelta or loop, we had doubled back through the rural Mexican back roads toward the pueblo directly across the border from El Camino. Judi and Virginia chat with their passengers as we approach the Mexican border guard kiosk. Now at the home crossing Virginia takes the lead this time in engaging the guard in conversation. Knowing the guard since high school, she chats about common friends, then parenthetically explains that we are with the university and that we are taking people in for health examinations for a research project. Fifty yards farther, on the U.S. side of the bridge, Judi pays the attendant, identifies us as employees of the university research center, and we are given the customary nod, smile, and minimalist hand gesture. “Bueno, have a nice day ladies,” the guard says, and we proceed to the office, which is about eight blocks from the Rio Grande.

We return around 10 A.M. Parking next to the other five minivans, we disembark. Judi and Virginia lead the research participants into the building, which is now bustling with activity. The one-story office building is three blocks off the highway near the old center of town. It is on a street with other social service offices, small older homes, and several boarded-up businesses. Like the highway and most built structures in El Camino, the bulk of the approximately 1,100-square-foot office building runs parallel to the river.

Once inside, the passengers are led to their respective stations. The L-shaped office layout is divided into 11 semiprivate work areas, each designed for a specific task. Every square foot of the office is used for something. Even the walls serve as reference points for maps, forms, inspirational posters, work schedules, or photo galleries. As one enters, there is an intake cubicle made of 2-by-4 lumber and a recycled Formica counter where newcomers are first screened. Beyond the intake area is a cubicle with a scale, calipers, and tape measure for anthropometrical measurements and a waiting area that doubles as a meeting and consultation space. Directly opposite the main entrance is the retinopathy examination room. Inside the room are a desk and two eye exam stations. Here, full eye exams are given, and retinographic images are taken in accordance with strict research protocols.

To the right of the retinography area is the main section of the office. On the north side2 is an area for the major blood draws3 performed by the staff nurse. This cramped multiuse area includes the nurse’s desk, a blood draw-chair with supplies at the ready, an empty table and chair used for one-to-one educational sessions, a TV, and another desk used for conducting the extensive medical histories that various research protocols require. Next to the blood-draw area is another bay of similar size that contains the storage freezer and a kitchen. Beyond the kitchen, a central hallway divides the office. On the north side is the lab, a rest-room, and two small partitioned rooms for taking echocardiograms (echos) and electrocardiograms (EKGs), respectively. On the south side is a room with seven staff cubicles and one shared computer station. Judi’s office, the only one with a door, is situated opposite the kitchen.

The filial, economic, and social ties between people along the river make crossing the official border necessary and commonplace. Though border patrol agents outnumber police 5 to 1, for locals the checkpoints are occasions to inquire about an agent’s family—if familiar—or perform the minimal amount of deference required to get the go-ahead from a new agent. The data set comprises information on siblings who are both diabetic as well as on their other relatives with diabetes that the staff can enroll. Because family ties do not adhere to the imposed frontera/frontier, blood samples are regularly collected from Mexico. As Judi once remarked,

One time an agent gave us a hard time for bringing blood samples back over the border. He had good questions and was probably following the letter of the law . . . but he didn’t understand how things work around here. He’s been reassigned. But we carry the Customs book’s Biological Use of Blood Sections just in case another agent needs educating.

Though the river separates the land into two nation-states, for locals it is an inconvenience and a formality that punctuates the seamless ties between here and there, entre aqui y alla.

For some, the border is a reminder of the political history of their community. “At one time, this land was stolen from the Mexicans,” one center staffer notes as we pass the mansion of a corrupt judge. The judge, like so many landowners before him, defrauded the unsuspecting by selling the same plot of land several times over. Land disputes, corruption, and violence are the subject of many conversations between the center workers and their research participants. Other common topics are jobs (or the lack thereof), migration, crops, drug lords, and of course family and health.

“Sun County,” the (fictitious) jurisdictional name of the Texas side of this area, is one of the poorest regions in the United States and is known as one of the roughest drug portals on the U.S.-Mexico border. It is also known for its close multigenerational families and indifference to the formalities of border crossings, reflecting the persistent tenuousness of the symbolic and material dominance of the U.S. nation-state along the border and elsewhere.4 Sun County comprises a series of Mexican pueblos and their South Texas counterparts along the Rio Grande. Like most of South Texas, Sun County boasts agricultural production (grapefruit, onion, sugarcane, sorghum), cattle ranching, and mining and other extractive enterprises as its dominant industries. U.S. Census figures from 2007 estimate that 32 percent of Sun County’s total population lives in poverty and that this includes up to 45 percent of the county’s children. Per capita income is a third of the state average, and nearly 20 percent of Sun County residents are registered as unemployed. High school graduation rates are less than 40 percent. Fewer than one in four residents have health insurance.5 There is less than one direct care physician for every thirty-four hundred people (the state ratio is 1:661), so being seen by a doctor when ill is a luxury for most. Women must leave the county to find an obstetrician or gynecologist.

The region has a well-documented historical and ethnographic record. In his ethnographic examination of the cultural poetics of the region, Limón summons the earliest ethnographic and historical records of the area to highlight that the “lowest socio-economic class sector has historically waged the most intense warfare and suffered the most intense defeats, including, now, the imposition of . . . a racial and class-inflected postmodernity.”6 Scholars characterize the persistence of inequality along the U.S.-Mexico border as a continuation of the region’s social history.7 Born of the atrocities of a land-hungry state, the South Texas region is the site of countless battles between Mexicanas/os and Anglos. A half-dozen military forts stand as structural monuments, if not museums, of the seizure of land that was Mexico’s and the incorporation by fiat of Mexicana/o residents into U.S. jurisdiction. The quickly forsaken 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was but one event in many since, which Mexicanas/os did not quietly accept. Texas Ranger atrocities ensured generations of enmity expressed in heroic Mexicana/o folklore. Through it all, decade upon decade, Mexicanas/os, banditos, and rancheros are subjected to a common description in the Anglo imagination. As one historian says, “Half Indian and half Spanish, gaunt, dark, and of swarthy visage, with ferocious-looking brows and menacing mustaches, they were the ‘Arabs of the American continent.’ Feared by their own people as much as by the Americans, they exhibited ‘but little advance in civilization.’ ”8 One need only search contemporary nativist sources to read similar sentiments of contemporary disdain for Mexicana/o peoples, especially immigrants.

Scholars of the region have amply demonstrated that the transformation of the border region has fueled and been fueled by the political and economic “wars of maneuver” for more than 150 years.9 A zone of often violent conflict, the region has endured two wars (three if the fallout from the U.S. Civil War is included) and a long history of Anglo domination of purportedly inferior Mexicano/a peoples.10 In a poignant depiction that brings us to the present, Limón summarizes the transformation of the political economy of Texas thusly:

[Anglo] Americans came to a new environment to create a new politically and militarily sanctioned culture and economy. The latter would be based on commercializing south Texas into a major agribusiness sector responsive to the demand for food in industrializing America. Based on the “appropriation” of Mexicano land, more often by foul than fair means, this impoverishing social imposition on Mexicano society continued to be ideologically sanctioned by the same continuing racism, religious prejudice, and linguistic xenophobia that had been introduced with the [Mexican American] war.11

The contextualization of the border as a war zone, an analysis supported by numerous historical and contemporary events, is highly instructive for this present account of diabetes research in Sun County: Limón’s field site, the rural areas upriver from “McBurg,” overlaps with the diabetes DNA sampling project of interest here.

Sun County, unlike McBurg and other more urban areas, never attracted many Anglo settlers. It was and remains, a predominantly Mexicano region. Its doctors, lawyers, judges, teachers, and business owners are predominantly Mexicano as are the ranchers, agricultural workers, and those involved in illegal trade. The economic transformations have largely been influenced by changes in agribusiness and in the ebbs and flows of drugs and people between Mexico and the United States. Between the 1960s and 1970s, charter buses provided by processors, packing plants, and growers would line Main Street to carry workers to inland Texas and beyond. Today, such courtesy has been replaced by vanloads of workers stacked six rows high who travel at night on well-worn, well-known passages. Paying between $500 and $2,000 for the promise of delivery past the Texas inland checkpoints, many are dumped just across the boarder. Locals tell me that most do not stay. Their contacts find ways to get them through, or they return to try again later with another coyote.

Sun County’s remoteness enables clandestine crossings, the sheer volume of which captures the surveillance and enforcement agents’ attention. The locals, long term or migrant, are resigned to the political and economic forces that shape their community. As one middle-aged woman recounted, “Everyone knows who is involved in las drogas y otras cosas, Miguel [. . . drugs and other things, Michael]. Y tambien, that those [elected] guys in Austin have their hands in it too. It’s a small town. We all know which ones have their ‘side business’ here in Sun County.” Coupled with such resignation is pride and dedication to the community. One vice principal boasted that the test scores and graduation rates of El Camino’s schools rival many from the Texas inner city. Murals celebrate local generals, picturesque landscape, and agribusiness breakthroughs. Local humor, folk songs, and church and civic groups all celebrate the region, its river, and its people.

It is in this historical space, under these political and economic circumstances, that Mexicana/o DNA donation must be understood. In this chapter I will characterize the complex data-gathering research practices in El Camino and examine the meaning systems that Carl and his field staff use to explain their work. This ethnographic material will be analyzed within the broad political and social context of the area. My assessment is intended to produce a cultural critique that will demonstrate that the scientific frontiers of diabetes epidemiology are configured by the political and economic exigencies of the national frontier.12 It will be shown that the context of DNA sampling enables scientists to both exploit and construct stratified categories of difference founded upon the region’s Mexicana/o residents’ material conditions.

The second aim of this chapter, thus, is to illustrate the cultural consequences of diabetes science on the border. It will be shown that research protocols genetically diagnose Mexicana/o bodies, which aligns the scientific enterprise with the state enterprise of continued capital accommodation and expansion in the region. I will argue that the social relations of DNA sampling along the border discursively configure Mexican American bodies as biologically predisposed to diabetes. Further, I will show the ways Mexicana/o and Anglo alike are rendered hybrid subjects whose ethnicity is flexibly affixed to meet the scientific requirements of the enterprise and the sociopolitical patterns of identity in Sun County. As I argued in chapter 1, this pseudo-reiteration of race is not possible without the particular sets of social relations of DNA sampling, to which we now return.

Mexicanos/as in South Texas are making biomedical history. A search of the National Library of Medicine for Carl’s publications produce nearly 90 publications appearing in numerous journals. In 2000, Sun County made international news headlines with articles reporting the “discovery” of a combination of genes that confer susceptibility to type 2 diabetes. These polygenes, discovered by analyzing the genetics of Sun County Mexican Americans, were announced in the journal Nature Genetics. The significance of this recent finding should not be understated. Finding genetic associations for type 2 diabetes, long viewed as a disease of environment and behavior, is what a Nature Genetics press release for the discovery calls “the holy grail of genetics.” It launches a new era of medical genetics research because the methods and theories deployed in the diabetes research on Sun County Mexicanos/as can be applied to conditions like heart disease, obesity, hypertension, asthma, and a host of other conditions once thought of as predominantly environmental.13

Carl has a staff of nine public health outreach workers, all local women, who work to recruit, screen, monitor, and sample Mexicanos/as for his research. Without these local Mexicanas—the staff and the participants—Carl, the consortium, and the wide world of complex disease gene research would not enjoy the attention it currently receives in the press and in scientific journals and on Wall Street.14 Success in acquiring DNA from Sun County and the border towns of the northern Mexican frontier requires a unique blend of social, political, and investigative expertise.

The research office is managed by Judi, a Mexicana in her mid-fifties, who has worked for Carl for more than 20 years. Judi translates Carl’s paternal—and exacting—managerial style into a professional, yet down-to-earth, practice of data gathering. Throughout the center, used furniture and handmade curtains starkly contrast with the crisp white coats and scrubs many of the staff wear. The atmosphere is professional yet disarming. “It’s about being low key so people feel comfortable,” Judi explained in the customary English-Spanish code switching of the region. “Some people don’t understand that we can’t just treat people like, well, tu sabes [you know]. . . . People have to have confianza [trust].”

The ability to make people feel comfortable in a professional medical setting is the result of the dedication and understanding that the office staff bring to their work. Judi’s professional ethos is one of caring and service to her community. “If I can help just one person feel good today, I have accomplished something,” she remarked. Similarly, while driving through a field toward a group of field workers weeding small cotton plants, Lena recounted how as a child she and her siblings would accompany her mother to the fields. She recalled: “My mother would make a lunch for all of us, and we would eat between the rows. I know what they are going through, Miguel. I remember my mother would give us Kool-Aid if we helped her pick the cotton. Our hands were all cut up, but my mother’s were worse.” When we arrived to take the blood sample from “Chucho,” one of the workers, Lena’s ability to engender confianza was evident in her detailed small talk about the field, about cotton, and about working so hard when you are fasting, or in Lena’s case a hungry child accompanying her mother to work.

This confianza is one aspect of the work that cannot be understated. It is more important to recruit and keep participants involved in the research year after year than knowing the precise thresholds for Hemoglobin 1 AC, than seeing more people in less time, than remembering when the blood samples get shipped, than washing the vans that shuttle participants, or even answering the intake form questions exactly—all items of great scientific import about which Carl might badger staff at a meeting. Without the confianza, however, people will not participate in the research.15

Judi and her staff deploy local knowledge and expertise in the recruitment and retention of research participants. I refer to local knowledge as the robust contextual, experiential, place-specific community understanding of what people in Sun County experience every day.16 What Judi and her colleagues refer to as confianza is the net result of years of experiences with diabetes and diabetics, but more important, with the experiences of living and working in Sun County. Moreover, without Judi, her staff and the community of DNA donors, Carl’s research could not be produced.17 As one consortium member from Glaxo explained, “Without DNA, we can’t do research.” Or as Nora remarked, “You can’t clone someone’s gene if you don’t have their DNA samples.” This is a contribution to making scientific knowledge for which there is little recognition and, because Judi’s and her staff’s work does not fit the dominant models for Mexicana identity and social position, even less ethnographic analyses.18

This is more than a democratic pronouncement about the way scientific knowledge gets produced. Like engaged applied anthropology, community-based health research, and community-based participatory research in environmental justice movements, this local knowledge is a constituent element of the way diabetes genetic knowledge is produced.19 The polygene finding and all others that relied upon Sun County DNA are literally coproduced by Judi and the center staff.20

Carl’s relation to local knowledge makers who are responsible for participant recruitment is a complex one. There are deep, caring connections between Carl and his staff and between participants and the center staff. Many have participated and thus known each other for decades. “Carl drops everything when I need him to,” Judi remarked as we were unloading shipping boxes one afternoon. When there is a problem with staffing, personalities, a participant, a community professional, or data collection, he comes. “He tells [staff] the big picture . . . the importance of the project and all that we have accomplished. It really makes a difference, and I appreciate that,” Judi remarked. Pictures on the wall display more than 20 years of history at the center. Like a family photo wall, ages and surroundings progress through time.

Another feature of local knowledge is that it often entails oppositional discourses that reveal, rather than occlude, structured inequalities that are embedded in the knowledge.21 In spite of the care with which Judi, center staff, and Carl treat one another and their community, there exists an internal critique. For example, Judi filled the confessional space that my presence created with stories of how Carl does not understand what it takes to manage eight outreach workers and maintain the confianza so essential to the center’s success. “Our official titles according to the University System are clerk 1, 2, or 3 and administrative assistant 3 or something,” she explained, looking for my validation. “They pay us a going wage for El Camino, then find the classification that matches the wage. We are all hourly.” Given Judi’s managerial duties—and hence unclassified/exempt status eligibility—I was sympathetic and agreed with the implicit critique. I tried to explain to Judi that perhaps Carl’s business sense was how he kept the center funded, and her employed, for all these years.

Yet more than the wage inequities, uncertainties about the role of the center is an issue. Imelda, a recruiter who has worked on and off for Judi and Carl over the years, told the story of one participant, a man by the name of Fernandez. “Miguel, it is just awful. Poor Señor Fernandez, a U.S. citizen, had TB [tuberculosis], but because he hadn’t had continuous employment in the fields he didn’t qualify for SSI [supplemental security income] or Medicare. He moved back to Mexico to get care even though he’s worked here all his life. Can you imagine that!” She volunteered the story after I commented on the large number of abandoned houses in town and in the colonias (subdivisions, colonies, settlements).

More pointedly, one health professional familiar with the center remarked that participants are never offered treatment. When I ask why, she answers, “Naci de noche pero no anoche” [I was born at night but not last night]. The explicit critique is that treatment would threaten the (un)natural experiment of sampling families and monitoring their progress toward complications. As one Web site says, the study “has completed sampling and extensive genetic typing on more than 5,000 individuals. . . . At this time, the main recruitment effort is to re-evaluate previous study participants to measure changes in their health over time and to perform a more extensive study of the hearts of the subjects, most of whom have high blood pressure.”

Collecting DNA to study the genetics of susceptibility to high blood pressure and numerous complications of diabetes are also part of the center’s activity. In fact, participants can be screened for retinopathies with a series of state-of-the-art retinal cameras, heart conditions with echocardiograms, as well as blood tests for lipids, glucose, and measures of blood pressure and obesity. While no treatment has ever been offered, Carl hounds his staff to follow up referrals to physicians whenever any clinical condition is found or even suspected.

Carl’s hands are tied in his ability to provide treatment to participants. There are numerous prohibitions against providing health care as a form of de facto payment for participation in research. However the critique that no treatment is provided reflects the local frustration that health care is so hard to secure in Sun County. No one feels this more than local doctors. As one local medical official recounted, “I told the [federal] commission on border health that I am tired of surveillance. We know we have diabetes. We must fund solutions now to this epidemic.” Another noted, “For clinicians, genes are important for us to know about. But for lay people, it can be used as an excuse to not do anything [about preventing diabetes].” Everyone, health professionals and lay people alike, remarks that fast-food chains bombard the community with advertising. One local educator wondered aloud if the advent of school breakfasts and lunches with highly Americanized and processed foods might account for the upward trend in diabetes among school-age children since 95 percent of kids in his school get both.

Those who expressed doubts were those intimately familiar with the work of the center.22 This double consciousness weighs heavily upon my El Camino interlocutors.23 It is important to note that the only time I received instruction for “off the record” statements was during these moments of critical doubt. The oppositional discourse is acute in its reference to broader patterns of inequality in the region. The critique of the federal spending on surveillance, the doubts about the effect of federal food programs, the lack of treatment in the midst of a shortage of physicians, the elected officials who have financial interests in Sun County contraband, and the exploitation of confianza to persuade people to participate in studies were all noted, resignedly, as among the externally imposed burdens the community must bear.

“It’s our Valley culture to help one another,” notes one health worker. Working for the center is a kind of activism born of the contradictions of finding work while building community. The ever-present critique just as often gets expressed as a joke, a saying, or a story. I interpret such expressions as cracks in the dominant discourse about South Texas, but also about its people. The critique, thus, reflects the spirit of South Texas, perennially critical, expressive, and nuanced.24 In this way, the center reflects the community because it is created from within it, contradictions and all. The burdens of those contradictions and the responses to them are far from victimological. In Ruiz’s words, “Struggles for social justice cannot be reduced down to a dialectic of accommodation and resistance, but should be placed within the centrifuge of negotiation, subversion, and consciousness.”25 They also reflect the social, political, and economic impositions of structural and symbolic violences upon a multiply marginalized rural area. These critical sensibilities oppose the fixed notions of a weak and impoverished community by revealing an awareness and discourse of these structural contradictions. As such, they resonate completely with the counternarratives for which the region is well known.26

The stated objectives of the center’s activities are summarized in the consent form for a genetics of retinopathy study. It reads:

The purpose of this research is to learn why diabetes complications develop. I understand that this study is an extension of studies on the genetics of diabetes that I have already participated in. I realize that my participation may lead to no immediate benefit to me or my family, but may enable scientists to understand better how genes contribute to the eye and other complications of diabetes and thereby to help others.27

Each work station in the center has been meticulously designed around research protocols for numerous concurrent projects. Staff members keep track of their visitors with color-coded chips because at any given moment there could be a dozen people juggled between more than one research project: as one protocol is finished, a yellow chip is exchanged for a red. The most extensive protocol requires 36 different samples including blood, urine, and plasma as well as EKG, echocardiographic, and retinographic images. Though many jobs are shared, including routine office upkeep and administration, staff members specialize for particular research projects.

Judi and her staff often lead hectic work lives. Every square foot of the office is in use for much of the day. The staff, all high school graduates, are certified phlebotomists and certified lab technicians. One is a certified retinographer, and one staff member traveled to New York to become certified in echocardiography. Their commitment to confianza, however, does not stop them from referring to participants in a local vernacular that is coded into the endless paperwork they must keep for each one. “We have ‘schedules’ to pick up at 6:30, ‘GRs’ [genetics of retinopathy] and ‘walk-ins’ tomorrow, we need 600 ‘controls’ by May,” Judi directs the staff. Participants may arrive with names and addresses, but they are quickly transformed into schedules, GRs, walkins, and controls whose blood serum, red and white blood cells get separated and shipped to Carl and his collaborators for numerous genetic research projects.

The complexity of the work at the center—the blood work, retinography, echos, EKGs, glucose, body mass measurements, and more—are designed to capture biological data on Mexicana/o bodies along the border. As each new research subject is enrolled, the consent forms are read and discussed. An intake can take 45 minutes or longer. This intake process initiates the transformation of Mexicanas/os into research participants for the diabetes enterprise.

The staff calls them “participants,” not patients, given that “we don’t do any treatment.” And participate they do. Thousands of individuals have participated over the years. Carl’s emphasis on “participation” marks his vigilance against the Human Subjects protections about making false promises of benefit but also frames the relationship of DNA donation in the language of humanitarian egalitarianism. As opposed to the labels “patient,” “subject,” “donor” or “volunteer,” “participant” ideology is frequently referred to in Judi’s and Carl’s recruitment pep talks. “By participating in this study, you will be helping your children” is one such participant recruitment phrase.

Carl’s insistence on the label “participant” is a gesture toward the egalitarian participatory research practices of action research within public health and popular education.28 It would be inaccurate to write this naming practice off as merely a means to distance research participants from patients to reduce the ethical quandaries associated with the confusion that might result should a participant think some treatment for diabetes was possible through his or her involvement. The field station does have the look and feel of a community clinic. Staff members wear nurses clothing, vitals and biometrics are taken when the person arrives, and back rooms contain complicated biomedical surveillance apparatuses. However, for Carl and field office staff, participation is a philosophical, rather than ethicolegal, orientation.

Carl recognizes that his success depends on community buy-in which in turn depends on the buy-in of his office manager, clinical director, and other staff: All have been members of the local community for generations. More important, Carl’s and Judi’s careers matured together in this field office. Thus, his connection to the community is palpably filial. Judi and the Sun County participants are like family. However, unlike the inductive epistemological commitments of my use of the term “participant-collaboration,” Carl’s “use of participants” in his study is just that: their use in his study. That is, Carl has defined the questions, the problems, the methods, the acceptable findings and has enrolled participants into his epistemologically reductionistic enterprise. This assessment is not meant to privilege inductive methods over deductive ones, nor ethnography over genetics. Rather, to fully understand the global apparatuses of DNA collection, circulation, and production requires an appreciation of the contours of its acquisition.

Participants in this respect are more like donors of time, energy, embodied knowledge of their diabetes, and, of course, blood. Taking participation beyond a gesture toward egalitarianism would require the DNA field office to include research questions and courses of action that are thematically generated by participants. Hence, the defining characteristic between Carl’s participation and participatory research and action is that Carl’s participants remain squarely the objects of study and not subjects of inquiry and action.29

Consent forms like the one used at the field office and Judi’s dedication to helping the community call upon the ideology of participation and of volunteerism to create the conditions for DNA donation. Examining the creation of biobanks in Europe, scholars have noted that this type of participation is a set of social relations.30 Whether blood, tissue, or genetic material, each transfer of biologic material is intimately part of the local discourse of exchange within each sampling effort. The genetics of chronic diseases presents unique challenges to these relationships because the long-term nature of the sampling efforts are tied directly to the community rates of these diseases. More than simple genetic reductionism in which the genome is treated as the dominant force in all things, the semiotic duty of a participant’s DNA conjures a double ideological message:31 first, that genes drive diabetes; and second, that individual genes can inform groupwide patterns of disease. Unlike biobanks in England, Iceland, or Sweden, where material is taken with unspecified and often blanket research interests, the Sun County sampling effort enrolls participants “as if” the community rates of diabetes were going to be reflected in the individual participant’s DNA. On my first visit to the field office, for example, I asked Judi why there were so many diabetics in her community. She replied matter-of-factly, “It’s in our blood.” Judi’s answering of the hail of biological determinism is not surprising given her responsibility for collecting DNA samples from Mexicanas/os in El Camino.32 However, the essentialist notions of ethnicity in the phrase “our blood” warrants further scrutiny.

The sampling of DNA enacts a worldview that diabetes is a biological phenomenon alone and that the disease rates are the result of the differences within the participants’ bodies. This is an ideological proposition. Ideology, writes Althusser, is a dynamic construction of a “system of ideas and representations which dominate the mind of a man or a social group.”33 This construct is an imaginary representation of one’s real conditions of existence, which for Althusser was fundamentally based on the material relations of inequality between persons within class societies. “What is represented in ideology is therefore not the system of the real relations which govern the existence of individuals, but the imaginary relation of those individuals to the real relations in which they live.”34 In other words, an ideology is a symbolic explanation that we use to describe the world we inhabit.

For instance, targeting the bodies of Sun County individuals maps seamlessly onto the system of ideas that blames the poor for their poverty and the sick for their disease. The blame-the-victim ideology is the idea that if people worked harder, stayed in school, dieted or otherwise changed their behavior, they would not be poor or infirm.35 Participating in research that targets individual bodies without reference to the pronounced structural inequalities that have shaped the region and lives of its inhabitants actively creates the “as if” worldview or ideology that diabetes is a biological—not social—condition. More important, the reduction of diabetes to an individual biogenetic condition that occurs through targeting individuals divorced from their contexts is a contradictory imaginary. That is, the ideological maneuver is not simply the reductionistic one that places individuals as the locus of the disease. Rather, in so doing, the configuration of diabetes as a biogenetic condition keeps the individuals in the crosshairs of blame—except in this instance, their behavioral inadequacies trigger their genetic ones. This is the double edge of the gene environment narrative when social variables are ignored.

In his astute assessment of the U.S. policy of research inclusion, sociologist Steven Epstein details the ways the civil rights movement made necessary the inclusion of women and minorities in clinical research.36 Since women and minorities had been either excluded or abused in previous decades, medical research findings were skewed to reflect clinical universals based upon small nonrepresentative samples (e.g., white college students, white men, soldiers, etc.), or, worse, research was conducted in ways designed to reinforce folk ideas about social difference. The national policy imperative to include women, children, and minorities of color as research subjects and researchers spawned a new science of recruitment, which Epstein calls “recruitmentology.” Recruitmentology draws upon the ethos that underrepresented people should be included and that their difference should be an object of study.37

Carl’s field office might be considered as one of the ground zero sites of recruitmentology. The Sun County sampling efforts began at the same historical moment as the inclusion-and-difference paradigm that Epstein’s work so thoroughly details. The reported motives for sampling were and are to improve the lives of Sun County Mexicanos. There is no question that Judi, Carl, and most of the field staff feel that their work rights a wrong and that theirs is a labor of love. The use of community workers, the narratives of trust, and the community service ethos that permeates the field office culture exemplify the best ways to recruit participants from hard-to-reach areas and populations. Though Carl’s papers rarely speak of his recruitment apparatus and thus may not be formally part of the science of recruitment, I concur with Epstein’s observation that the “theory and practice of recruitmentology have promoted new fusions of biological and cultural knowledge about the medically ‘other.’ ”38 For it is through scientific explanations being crafted from Sun County DNA sampling that sociological explanations of the conditions of life along the border are imagined in ways that conceal the sociocultural while foregrounding the biological.

Sun County Mexicana/o participants are recruited into a transnational diabetes research enterprise and thereby accept the hail of the historical and contemporary formations of Anglo and Mexicano relations. Althusser writes, “Ideology ‘acts’ or ‘functions’ in such a way that it ‘recruits’ subjects among individuals, or ‘transforms’ the individuals into subjects by . . . interpellating or hailing.”39 That is, by participating in this research apparatus, Mexicanas are further subjected to the logics of Anglo dominance, which is manifest in high poverty rates and pervasive medical neglect, both of which are causally implicated in diabetes. The humanist impulse to help the community only works as a response to the interpellating power of these ideological premises within the sampling enterprise. I draw upon Althusser because the hail occurs within a regime of historical inequality and violence akin to coercive apparatuses: police forces, military presence, the Immigration and Naturalization Service, the Texas Rangers, and so on.40 That is, accepting the call to participate is a particular social relation between a state apparatus and a community. Unlike Althusser’s configuration, however, the state apparatus imposes its contemporary threat through the structural violence of gross neglect and social inequality and is manifest in the targeting of the Sun County Mexicana/o community for sampling.41

The social relations configured in diabetes research recruitment and participation are, like Epstein’s inclusion-and-difference, a biopolitical paradigm. To wit, recruitment and participation in the diabetes research apparatus are “an example of how biomedicine (for better or worse) gets politicized . . . and governing gets “biomedicalized,”42 Further, Schneider and Ingram have observed that target populations are configured to fit the instrumental needs of policy makers.43 They also demonstrate that the benefits and efficacy of a given policy often are prefigured by the type of target population the policy constructs. I argue that populations targeted for DNA sampling also are prefigured, as in public policy. In the case of Sun County community members, converting someone into a participant includes constructing him or her as a humanist, as a genetic carrier who represents the broader community, and as a passive, docile body upon which a benevolent bioscientific interlocutor can work for a greater good, one that is greater than the immediate needs of the individual, the individual’s family, or the community.

In spite of the oppositional discourse, the hushed tones of critique never emerge into an appeal or movement for treatment or prevention. “Only more research,” notes a health professional familiar with the DNA collection operation. Contrasted with movements to clean up toxic waste dumps, to improve the health of IV drug users, to screen people for diseases, the complete interpellation as humanitarian and politically docile “participant” is striking.44 To imagine a genetic sampling field office that spent as much time and resources on prevention, community development, and disease management as is spent on surveillance and genetic sampling would require a very different kind of participant and participation. It would require a program in which a donation of biological data also required a donation of time to organizing walking groups, menu surveillance at the schools, health promotion at workplaces, to help those on diets manage caloric ledgers, and the provision of safety nets for housing, health care, food, and other services.

In chapter 1, I presented the rationale for the use of genetics in searching for diabetes cures. As I said there, geneticists use populations to understand the genetics of disease, whereas epidemiologists use genetics to understand disease in populations. However, the study of type 2 diabetes as a biogenetic condition runs counter to the social epidemiologies of disease. Further, treating diabetes as a genetic condition, as researcher, clinician, or patient, obscures the cultural epidemiology of the disease.45 By examining the social explanations of disease as an alternative to the biogenetic epidemiologies, the cultural consequences of DNA sampling will become clearer.

The prominent use of Mexicanas/os on the border as a racialized population whose heredity confers susceptibility to type 2 diabetes is wholly consistent with the epistemological shift away from context and toward explanations of poor health that focus on and sometimes blame the individual.46 An emphasis on risk factor research models has resulted in the erasure of the socioeconomic, historical, and political contexts of populations affected by disease. Life and ecological conditions have been replaced with a reductionistic emphasis on individual and molecular causes of disease. Pearce notes, “The decision not to study socioeconomic factors is itself a political decision to focus on what is politically acceptable” and scientifically imaginable.47

That Mexicanas/os have been targeted for such research is also not surprising. In fact, as the political history shows, the South Texas border region has always been part of state-sponsored or -sanctioned use of the Mexicano/a population. That Mexicanos/as are now used for genetic research, is, it would seem, an almost predictable progression from their use as cheap labor, as Other whose rights to own land or vote varied according to Anglo needs for land and political power, and as national enemy in the context of war and capitalist expansion along the border. Is it a coincidence that Carl’s project began in Sun County at the moment—the 1970s—that the marginalization of Mexicanos/as had stabilized into what Limón argues is now a permanent status of political and economic stagnation? It is a moment now recognizable as keyed to the flexible accumulation characteristic of Harvey’s “condition of post-modernity,” in which labor and laborers are subjected to the whims of distant calculus of economic inputs and before this, Marx’s “floating populations” as the social costs of industrializing agriculture.48

In spite of the convention of explaining the incidence and prevalence of health conditions through biological processes, the incidence of diabetes in the Mexicano/a populace constructed through Carl’s research tells a different story when contextualized within the political and social history of the region. In this light, diabetes is strongly associated with the national political and economic transformations on the border over the last three decades, transformations that themselves reflect new regimes of labor control and the deployment of new technologies.

Beginning with the categories used in epidemiological research, Krieger and Fee trace the history of its use of gender, race, and class variables.49 They demonstrate the ways scientific research configures health risks for populations in accordance with prejudices of the day. From the early nineteenth century to the present, they argue, the so-called biological factors used in biomedical research simply “confuse what is with what must be.”50 This confusion is done through several means. As we have seen from the review of American Diabetes Association abstracts, population categories identified within biomedical literature do not reference anything biologically meaningful but are presumed biological by virtue of their increasing frequency in diabetes research reports. As Krieger and Fee observe, race is presumed to be biological, affected populations are presumed to have biological reasons for their health condition, and physiological differences between populations are given near-magical deterministic powers for health outcomes.

The arguments against racial codes in epidemiology and those that fault epidemiology for the absence of class and socioeconomic status from analyses conclude that social-historical factors, not biological factors, more accurately predict and explain health conditions between and within certain populations.51 Further, in a 2003 issue of the American Journal of Public Health, authors launched an explicit discussion about racism and racial-ethnic bias in health outcomes. Editors called for careful characterization of racial-ethnic prejudice and the physiological response to them.52 Krieger proposes an ecosocial perspective that links racism, biology, and health and that includes economic and social hardships, toxic exposures, verbal and physical threats, unhealthy consumer messages, and substandard medical care: all areas known to affect health.53 Nazroo, van Ryn and Fu, Harrell and colleagues, and Williams and colleagues in varying ways take up Krieger’s call and offer evidence that economic deprivation, biased health care provision, the experience of racism, and community stressors all contribute to negative health outcomes.54

Earlier research by anthropologists argue that epidemiology and anthropology share vital epistemological similarities that, if brought together, would make a good corrective to the social blinders within conventional epidemiology that allow for arbitrary categories of race to persist.55 Hahn’s groundbreaking work importantly highlights the technical weaknesses of racial categories but stops short of assessing the basic assumptions embedded within the categories deployed by epidemiology and anthropology. Social epidemiologists (Krieger and Fee 1994a; Krieger 2005) argue that research that focuses on differences in health patterns between individuals from the same ethnic group would serve as a foil to the current research failures.56 For example, one such failure is the decades-long quest to prove James Neel’s thrifty genotype hypothesis, an effort that has been shown to be both technically flawed and theoretically unwarranted.57

These critiques, and the alternative etiological frameworks for chronic diseases they sustain, directly counter the reductionism of genetic epidemiology. They also call into question the veracity of the risk for diabetes for Mexicanos/as that the genetics approaches portray. Certainly a genetic susceptibility, inasmuch as it omits or minimizes the local biologies of diabetics, is nothing if not a biological reductionism. More than an epistemological critique, however, I have also tried to show that this reductionism is overly reliant upon research variables (population labels, biogenetic samples) whose foundations are empirically neither robust nor reliable.

For this discussion, the epidemiological patterns are important in their cultural implications. That is, I will leave to epidemiologists the risk estimates and the discernment of incidence and prevalence patterns of diabetes along the border. What interests me are the (anti)political implications of a genetics model that so squarely relies upon the ethnically admixed body of Sun County Mexicanos/as. That is, as Ferguson has demonstrated of failed economic development projects that conceal political circumstances, the genetics approach to diabetes is a kind of “anti-politics machine” that reinforces and expands forms of state power while depoliticizing the conditions in which people live.58

Chapter 1 dealt with the theoretical vexations of population differences and the debates surrounding the objectionable uses of racial categories in medicoscientific research. This chapter explored the ways the ideologies of participation, human service, confianza, and a biogenetic approach to diabetes enacts an “as if” proposition of the border that conceals social inequality. In the next chapter, I present the ways the historical, material, and semiotic inequities of Anglo-Mexicano relations co-configure diabetes genetic science through the search for and use of ethnic admixture. This aspect of the diabetes enterprise begins with the premise that the individual biologically represents the community, that DNA represents the individual, and thus that DNA is a proxy for the population of donors of Sun County. The “as if” required for this synecdoche works through a series of strategic conceptual substitutions that enclose and reframe DNA as the material manifestation of the unique biological composition of Mexicano/a participant donors. The notion that individuals can inform—statistically, conceptually, or literally—population-wide representative models (genetic, demographic, cultural) is not only an essentialism of the first order, it is a peculiar kind of epistemic and epistemological politics. The political implications of the ways in which one stands for many in this sociocultural milieu requires that we look more closely at the presumed ethnic composition of Sun County Mexicanas/os.