I started painting on a regular basis in my early teens and almost from the beginning, encouraged by the example of some very experienced local artists, I adopted a practice for assessing the key elements of a subject, known as the ‘factor of three’. The three elements were appeal, composition and tone. The idea was that by considering each of these within a painting subject you could judge its worth, both in terms of its possibilities as an interesting painting and, ultimately, the painting’s potential for exhibition and selling. Then, as now, all of my work was inspired by plein-air subjects and I found the ‘factor of three’ method of evaluating them both helpful and reliable. I still use it today.

Winding Lane above Holmfirth

WATERCOLOUR ON ARCHES ROUGH

38.5 × 28.5cm (11 × 15in)

“For me, the three key elements to look for in a subject are appeal, dynamic composition, and interesting tonal contrasts.”

Because I am a tonal painter who prefers to work outside whenever possible, usually the aspect that I find most exciting and appealing in a subject is the particular quality of light and how this influences the mood and impact of the scene. My preferred approach is to paint contre-jour (into the light), so that the tonal effects are enhanced, although recently I have been working more often with the light behind me, which consequently creates greater emphasis on colour. Often, the subjects that have most appeal are those that I find during the early morning or late afternoon on a bright, sunny day when there are strong contrasts of light and shadows.

While a stunning light effect will add drama and impact to the subject matter, it must nevertheless work in relation to certain other factors if the proposed painting is to be a success. The content, and in particular the principal shapes within it, are equally important aspects to consider. Those main shapes will provide the basic structure for the painting and ideally not only must they instil a degree of energy and excitement in the design, they must also be carefully observed and well drawn. Look at the wonderful cliff shapes in Cliffs and Beachscape, Porthcothan, Cornwall, for example. Note also in this subject how the strong, low light creates interest and variety in the tones, with areas of mystery contrasting with others that are more clearly defined.

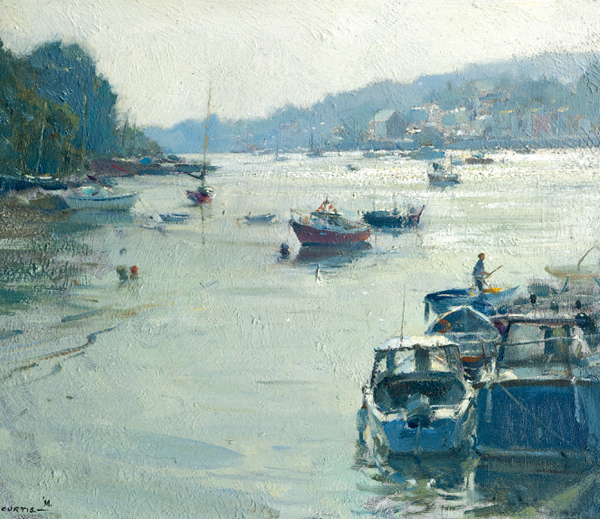

Penryn Harbour, Cornwall

OIL ON BOARD

25.5 X 30.5cm (10 X 12in)

“Here, the appeal was the moody, atmospheric and diffused quality of light.”

The initial reaction to a subject is important, because if there isn’t a sense of excitement about what you see – and a strong desire to paint it – then the eventual painting is unlikely to be a great success. However, before rushing to unpack the paints, it is always a good idea to spend some time making a more considered assessment of the subject. This will help avoid disappointment. When you are enraptured by something truly original and moving within the subject matter, it is easy to overlook a lesser feature that could ultimately prove a serious weakness in the design and impact of the work. Generally speaking, it is best not to be too hasty.

With this type of assessment, the ideal approach lies in striking a balance between relying entirely on inspiration and impulse and being too analytical about what you see and feel. My advice is to base the composition on whatever aspect of the subject matter first attracted you but, through a process of selection and perhaps inventiveness, ensure that the painting as a whole will work in relation to that main focus. Check the principal compositional elements, the colour contrasts and harmonies, and so on. If some kind of adjustment seems necessary in order to reinforce the impact of the main elements, check that it is not simply a matter of altering the viewpoint. Sometimes just a slight modification to the viewpoint will dramatically improve the composition – by just moving to the left or right a little – see Harbour Activity, Castletown, Isle of Man, for example.

Cliffs and Beachscape, Porthcothan, Cornwall

OIL ON BOARD

20.5 X 30.5cm (8 X 12in)

“To paint convincingly relies on an understanding of the subject matter, which in turn begins with observation – by studying the cliff formations in this subject, for example.”

Now, with accumulated experience, I find I can make the initial assessment of a subject – its individual strengths, nuances, design and structure – very quickly. With Harbour Activity, Castletown, Isle of Man, for example, I loved the classic lines of the boat and instinctively felt that the dynamics of the design would be emphasized by painting it from that particular angle. I could see that the boat would make a great composition when viewed with relatively little interest to its left and contained nicely by the variety of shapes on the right. As is so often the case, the light was a factor, creating some lovely strong dark areas that helped emphasize the bold form of the hull and the sense of depth towards the horizon.

Ambition is always a good thing. In choosing subject matter and deciding on the approach and techniques to use, my advice is to aim for work that tests your ability and involves ideas and methods that are at the edge of, if not slightly beyond, your ‘comfort zone’. If the painting places demands on you in this way, it is more likely to succeed as a strong, interesting image. Moreover, you will find that it is only by confronting even greater challenges – and persevering at ways to solve these – that you will improve your work and gain in confidence and skill.

The difficulty lies in judging just how ambitious you should be. By playing safe you gain nothing, whereas if you are over-ambitious the challenge could prove beyond you. It is a matter of finding the right balance. While you are gaining experience, I would say look for subjects that have bold, simple shapes, giving a sound compositional structure, as in Bridge and Stream, Aberdaron. Here, the main shapes are easily defined and they work well together to create an effective design. It is what I would call a traditional subject and, given the necessary care in the observation and drawing of the principal shapes, it is the type of subject that should prove a reliable and rewarding one to attempt.

In contrast, with a painting such as Harbour Activity, Castletown, Isle of Man, the demand on ability and experience is much higher. As you can see, in that particular subject, irrespective of the technical skills required to master the form of the boat, success depended very much on decisions about viewpoint and content. In fact, to help with those decisions, I started by making a small pencil sketch – just a few lines in a 10 × 5cm (4 × 6in) sketchbook. With more complex subjects, making a sketch is a useful way to help plan the essential elements of the design, even if I also decide to take some photographs.

Harbour Activity, Castletown, Isle of Man

WATERCOLOUR ON ARCHES ROUGH

28.5 X 38.5cm (11¼ X 15¼in)

“Viewpoint is everything in creating the most drama and impact from a subject.”

Bridge and Stream, Aberdaron

OIL ON CANVAS BOARD

40.5 X 51cm (16 X 20in)

“This was a lovely, what I would term ‘traditional’ subject, with lots of foreground interest.”

My most popular paintings are my beach scenes but, as you can see from the wide range of illustrations in this book, I enjoy the challenge of different subjects. I do not think it is a good idea to confine yourself to one specialist subject area. As well as being ambitious about how a subject will test your ability in expressing it in a convincing, original way, aim to keep an open mind regarding new types of subject matter.

I am always on the look out for quirky, challenging subjects. Even when I paint at Staithes in North Yorkshire, which is one of my most familiar painting locations, I try to find new, unexpected views. For me, the more important concern is that the subject will make a good painting, rather than be instantly recognizable as a particular place. Also, of course, light and weather can play their part in influencing the look and mood of a scene. What inspired me to paint Rising Mist, Staithes Beck, for example, was experiencing the scene masked by a heavy sea fret, or fog, which gave it an eerie, almost satanic feel. In fact, just ten minutes before I started painting this subject, it was barely visible. So, essentially the challenge was to capture the dramatic atmospheric quality – it is Staithes, but a different Staithes!

Rising Mist, Staithes Beck

WATERCOLOUR ON TWO RIVERS TINTED PAPER

38.5 X 28.5cm (15¼ X 11¼in)

“Again, here the inspiration was the mood of the scene. There was a lifting sea fret, creating some wonderful highlights on the boats.”

Roland with the Morning Paper, Rahoy Lodge, Scottish Highlands

OIL ON BOARD

25.5 X 30.5cm (10 X 12in)

“A wet day kept me inside, but I still found something interesting to paint.”

Coincidentally, the weather was also an influential factor when I painted Roland with the Morning Paper, Rahoy Lodge, Scottish Highlands, which for me was certainly a subject that was different and outside my comfort zone. It was a very wet day, but I desperately wanted to paint. I wandered around the house where I was staying with a group of painting friends and came across Roland reading his newspaper. In some respects this was not the perfect subject, but I was confident I could make something of it. I felt that there was enough interest in the pose of the figure to allow some of the surrounding background area to be treated in a much looser way. Interestingly, the more I worked on this painting, the more rewarding it became.

However well something is painted, poor composition will show and will seriously undermine the impact of the work. The potential within the subject matter for an exciting, successful composition is of paramount importance. Equally it is essential that the composition is carefully planned to support the aims of the work and ensure that the interest is kept within the bounds of the picture plane. I look for a composition that has a strong, well-balanced arrangement of shapes, without any sense of awkwardness. I like the composition to include something that leads the eye into the painting and takes it on a journey to a focal point, which is often a figure or group of figures involved in some sort of activity.

I think Children Playing in the Beck has one of the most satisfying compositions I have ever painted. I chose this subject for a painting demonstration that I had agreed to give at the Royal Society of Marine Artists exhibition at the Mall Galleries in London. I remember saying to the assembled group of 100 people that I was not too worried about working on the painting because the composition was so stunning and would compensate should there be any lapses in technique on my part. I decided to use a portrait format, which I felt would make the most of the dynamic play of shapes and the wonderful contrasts of light and shade. You can see that I have included a ‘lead-in’ with the foreground boat, active figures as a focal point and a small section of the red wall on the left to act as a ‘stopper’ to contain the interest within the painting.

In contrast, Old Church by a Dusty Road, Mykonos, Greece, a small plein-air oil painting, required a different sort of skill and inventiveness to overcome the challenges of its mostly ill-defined shapes, particularly in the large foreground area. For example, the rough roadway could easily have drifted out of the painting to the left, which is why I decided to invent the man on the scooter. The donkeys were part of the scene, although I moved their positions to help enhance a sense of depth across the foreground and similarly I exaggerated some of the tones, especially on the lower-right area, to ensure a more balanced composition.

Children Playing in the Beck

WATERCOLOUR ON ARCHES ROUGH

38.5 X 28.5cm (15¼ X 11¼in)

“With its incredible light effect, figurative content and juxtaposition of shapes, this was one of the most satisfying subjects I have ever painted.”

Old Church by a Dusty Road, Mykonos, Greece

OIL ON BOARD

25.5 X 35.5cm (10 X 14in)

“Sometimes a certain amount of manoeuvring with shapes and tones is necessary to create the most impact with a subject. Here, for example, to ensure a more balanced composition I invented the man on the scooter and exaggerated the tonal contrast.”

The Forgotten Garden, Near Bosa, Sardinia

WATERCOLOUR ON ARCHES ROUGH

57 X 78.5cm (22½ X 31in)

“I liked the idea of this view, contained within an archway, and the opportunity to use the steps to create an interesting ‘lead-in’ device.”

Often, in the early stages of learning to paint, there is a temptation to think that you must include every detail of the subject matter, as seen. In fact, very fussy, detailed paintings are seldom as effective as those in which the artist has selected and simplified certain elements in order to create a better sense of harmony and visual impact. The basis of good composition lies in the ability to focus on those aspects of the subject matter that are essential to the dynamics and interest of the design and, equally, knowing which aspects to subdue or perhaps ignore altogether. Success relies on economy of means, so that the composition conveys a great deal – both in terms of content and feeling – yet at the same time leaves something to the viewer’s imagination.

There are plenty of theories about composition, with advice as to what you should and should not do. Such theories are worth consideration, but a composition that relies heavily on theories will usually look contrived and consequently not attain its full impact. Most experienced artists work with a knowledge of the theories but at the same time they adopt a more intuitive approach. What seems right in theory doesn’t always succeed in practice and, conversely, with experience and ingenuity, something about composition that should theoretically be avoided can be made to work effectively.

Riverside Mooring, Bosa, Sardinia

WATERCOLOUR ON ARCHES ROUGH

28.5 X 38.5cm (11¼ X 15¼in)

“Here, the accent was on strong vertical and horizontal elements in the design.”

Generally, compositions based on a symmetrical or evenly balanced arrangement of shapes are not very successful. For this reason, most artists avoid placing something directly in the centre of the picture area. I sometimes include a feature that is almost central but not quite, as with the mast in Riverside Mooring, Bosa, Sardinia (above), The position of the mast works in this composition, partly because it is not a dominant feature and also because it links in well with the essential vertical and horizontal structure of the painting. Incidentally, note how the rigidity of the design is countered by the play of light and shadows.

As well as the relative positioning of the main shapes, well-conceived directional lines are often important as a means of creating a flow or a sense of rhythm around the painting, which can be reinforced by repeating little passages and accents of the same colour. Also, the energy and interest within the design can be enhanced by contrasting bold shapes and tones with some areas that are handled in a more impressionistic manner.

With most compositions I am seeking to tempt the eye into the central area of the painting, leaving the edges and corners less resolved, but I never rely on a set format. In Above Beck Hole, for example, the composition has a strong, diagonal rhythm. Similarly in Rising Mist, Staithes Beck, the angle and placing of the foreground shapes combine to create a dramatic lead-in to the painting and a sense of recession. Z-shape and S-shape designs are also effective in this way. In other paintings I rely on the more traditional ‘rule of thirds’ principle. Based on the Golden Section, this is a reliable form of composition built around a key shape placed approximately one-third of the way across the picture area.

Above Beck Hole

OIL ON BOARD

35.5 X 25.5cm (14 X 10in)

“For the composition in this painting, I exploited the inherent diagonal rhythm of the subject.”

Together with due consideration to the selection and arrangement of the key shapes within the composition, its impact can be enhanced by the particular way that other aspects are treated during the painting process, such as contrasts of light and dark, the use of colour and texture, and the handling of foreground areas. For instance, as well as being an essential element in expressing the mood of a subject, shadows can contribute in a very positive way to the visual flow, energy and interest in a painting. As you can see in Ancient Woodland, King’s Wood, Bawtry, they can be especially helpful in a foreground area, both as a means of dividing up and adding interest to an otherwise uneventful space and as a way of creating a lead-in to the painting.

In fact, in this painting I deliberately emphasized the simplicity of the foreground as a restful area, in contrast to the busy pattern of dappled light and shade that fills the top half of the composition. It is essentially a painting about light and shade, although this would not have been sufficient in itself to create a strong composition – I felt it needed the two, almost centrally placed figures to add a focus and an extra bit of interest and impact. Similar points apply to the use of reflections, as in the foreground area of Old Moored Vessels on the River Orwell. Here, note how the masts and their reflections break the composition quite boldly into three areas, but with the strong verticals countered by the shapes and angles of the hulls.

Colour is another useful means of giving emphasis to certain parts of the design and acting as a linking device. Although I am not a colourist, I quite often include a passage of high-key colour as a striking contrast or focus somewhere within the composition, which is another effective way of strengthening the impact. The considered use of more vibrant colour, as with the bands of burnt sienna on the boats in Old Moored Vessels on the River Orwell, will enliven a modest subject. Note too in this painting how echoes of a particular colour (burnt sienna) will help unify the design.

Ancient Woodland, King’s Wood, Bawtry

OIL ON BOARD

40.5 X 30.5cm (16 X 12in)

“Shadows are often a very effective way of linking parts of a composition, as here.”

Old Moored Vessels on the River Orwell

OIL ON BOARD

25.5 X 30.5cm (10 X 12in)

“Like shadows, reflections will add interest to otherwise uneventful areas of a painting.”

As I have mentioned, usually it is a particular quality of light that I most want to capture in my paintings and, therefore, I work principally in terms of tone. The inherent tonal qualities of the subject matter (that is the relative lightness or darkness of each particular element), and the potential to exploit these to create a painting with real impact, are aspects that I consider right from the start. In fact, the tonal key is often the feature that initially inspires me to paint something and, certainly more than other aspects such as composition, it allows a fair degree of freedom in the way that it is interpreted. The tonal balance, variety and impact are not always perfect as found in the subject matter but, with experience, these properties can be modified or exaggerated as necessary in order to enhance the success of the painting.

In some ways a sunlit, late afternoon subject will be easier to paint because the contrasts between highlights and deep shadows will be more evident and immediately add to the drama and mood of the scene. As in Tenders on the Slipway, it is often the play between the intense dark areas and the much lighter areas that contributes most to the energy and interest in the painting. Naturally I enjoy painting subjects in which there is an obviously strong light effect, but equally I like to paint in all types of light, including flat light – the sort of low, even light experienced on a dull day. Flat light can be just as rewarding, I think, and as I have implied, there is always the option of exaggerating the slight variations of tone that you find.

Old Moored Vessels on the River Orwell was painted on a very dull day, but as you can see, there is no lack of tonal contrast. I was struck by the potential in the composition of this subject and felt that it would work very well if I could somehow extract more drama from the tonal values. So, it was a matter of making the most of what was there and exaggerating the tonal range to significantly strengthen the darks and intensify the lightest areas. In fact, there can be an advantage in painting in flat light, because it will remain fairly consistent over a longer period of time and thus, if you wish, there is a greater opportunity to concentrate on the drawing and detail in the subject matter. For example, this is the sort of light I prefer for painting barn interiors, boatyard workshops and architectural subjects, which rely more than most on sound drawing.

Tenders on the Slipway

OIL ON BOARD

30.5 X 40.5cm (12 X 16in)

“I always make the most of the tonal contrasts in a subject, as this will enhance its impact.”

Light is a transient quality and one of the difficulties when working outside is that the weather, and consequently the light effect, can change considerably during the course of the painting. Even on a fine summer’s day clouds and shadows can come and go. Because of this, it is wise to establish as quickly as possible the type of light effect and mood that you want for the painting. Keep that in mind and do not be deterred if conditions change. Some artists like to start with a quick, small tonal sketch to use as a reference. Also, bear in mind that the same subject will result in quite a different painting at another time of the day or in different weather conditions. So, if the composition is enticing but the lighting is poor, an alternative approach is to return when you calculate that everything will be just right.

In capturing the mood of a scene and the sense of place, the ability to assess tonal values and interpret them convincingly is a vital asset. Yet the concept of tone, as opposed to colour, can be a difficult one to master. In fact, tone and colour are inseparable qualities, for each colour, as well as being yellow, blue or whatever, also has a particular tonal (light/dark) value. Tone relates to colour in two ways: each colour has an inherent tonal quality, so that yellow, for example, is a naturally light-toned colour and Prussian blue a dark one. Irrespective of this, within each colour there can be many variations of tone, according to how much it is diluted or which other colours it is mixed with.

When painting, the subject matter may include elements of local colour – that is the actual colour of the object, unaffected by shadows or reflections from surrounding objects – but usually the colour and its consequent tonal values are influenced by the effect of light and the way that it plays across a surface. Sometimes this creates many tonal variations, even within a relatively small area. As always the secret lies in simplifying what is seen; in concentrating on the essence rather than every detail. If you squint at the subject it helps to give a better perception of tone rather than colour, with a simplified view of the tonal range and the contrasts of light and dark values.

Copse on a Hillside, Anglesey

OIL ON BOARD

23 X 30.5cm (9 X 12in)

“To convey the calm mood of this scene, I used a limited palette of harmonious greens, blues and greys.”

Rainy Day, Venice

WATERCOLOUR ON ARCHES ROUGH

78.5 X 57cm (31 X 22½in)

“I love the challenge of busy scenes like this, which fully test one’s skills in drawing and the use of colour.”

I always work with a limited colour palette, which helps me focus on the tonal properties within the subject matter and create a degree of harmony in the finished painting. For example, Copse on a Hillside, Anglesey was painted principally in mid-tone values using harmonious greens, blues and greys to evoke a calm, gentle mood. The focus in this painting is concentrated in the middle distance, on the interesting pattern of shapes.

Light was the inspiration for this subject, which I painted on site between 7am and 9am on a fine, mid-September morning. I liked the mood of the scene, created by the quiet, slightly diffused early morning light, which I knew, at this time of year, would remain fairly constant for at least a couple of hours. Probably after that the dark tones in particular would become more intense and the shapes sharper and more defined.

The view was a familiar one – I often paint at Staithes in North Yorkshire – but as always I looked for something different in the composition. In this case it was partly the atmosphere of the scene, but also the fact that I wanted to try a square-format painting, which was something I had not tried before at Staithes. The square format is very appealing, I think, because it makes you concentrate on what you feel is important about the subject matter. It encourages a more disciplined approach to composition. From my vantage point, I could see that this particular view would give some useful directional lines in the composition, as well as an interesting sequence of block-like shapes and juxtapositions within the mass of buildings. In this case the low-key colours and tones were exactly the ones I wanted to capture in the painting, so I needed to work quickly.

I chose a 51 × 51cm (20 × 20in) gesso-primed canvas panel, working directly onto the white surface. I started with a general wash of colour and then lifted out the lightest areas, such as the foreground bridges and the distant sea area, with a rag. Thereafter, essentially the technique was alla prima, a ‘one-hit’, wet-on-wet approach, working with large brushes and vigorous strokes to capture as best I could the wonderful sense of light and the transient quality of the scene.

First Light in September, Staithes Harbour

OIL ON CANVAS BOARD

51 X 51cm (20 X 20in)