Some artists like to concentrate on a very limited range of subject matter, perhaps finding their inspiration from just one source, such as a particular landscape or an individual town or city. However, I prefer variety and apart from still life, which I have yet to consider, I enjoy the challenge and reward to be gained from painting many different subjects. Some of my favourites are beach scenes and interesting old boatyards and farmyards, but I also like painting various types of landscape throughout the seasons, boats and harbours, townscapes, interiors and people.

View from a Terrace, Volterra, Tuscany

OIL ON CANVAS BOARD

40.5 × 40.5cm (16 × 16in)

“Natural sweeping directional curves in the landscape often lend a most agreeable sense of design.”

Ardfern Marina, Argyll

OIL ON BOARD

23 × 30.5cm (9 × 12in)

“A complex subject, in which I have used the shape and direction of the outer boats to help focus attention into the centre.”

Variety can help keep your work fresh and forward-looking, as well as test skills and add to your overall experience and ability. Naturally the choice of subject matter and the objectives for painting can change over the years, as you develop greater confidence and experience.

I now travel much more in search of new subjects, both in the UK and abroad. This is not to say that I have exhausted all my local subjects, of course, although I accept that it is now increasingly difficult to find ideas that have the strength of formal qualities – especially composition – and the degree of originality that I value. I think that one does develop a more discerning eye for those qualities. However, with a little more effort, I can still manage to find exciting subjects in familiar painting haunts such as Staithes and Whitby.

To maintain a desire for painting and keep the work lively and successful, it is necessary to raise the challenge level now and again. I do this by visiting new places, undertaking challenging commissions and setting myself ambitious projects. For example, at some time in the future I would like to try some more very large landscape compositions in which figures play a prominent part – rather like the set-piece paintings by artists of the Newlyn School and the Pre-Raphaelites.

Harbours and estuaries are some of my favourite hunting grounds for exciting subjects to paint. There is every chance that I will find the sort of qualities that most appeal to me – dramatic effects of light with wonderful, interesting shapes and structures, offering the potential for strong composition and impact. Water and reflections, boat shapes, figures and a background of cottages and cliffs will all add to the atmosphere and challenge of the scene.

Marine subjects can be very complex – there might be 50 boats or more in a harbour – and therefore assessing what to include in your painting and what to leave out is the first important consideration. Other key factors to take into account are the tide and the light. You need to choose the right moment, when the tide and the light give you the optimum impact, and quickly record that effect. If you are painting on site, concentrate on the water first, to indicate its essential character and level, and the position of the boats, before things change. I prefer subjects that I can paint while the tide is going out, so the water level is falling and any boats will be left stranded on the sand. This gives some wonderful light effects on the wet mud or sandbanks.

With such a variety of potentially exciting subjects, there can be a temptation to be greedy and include more in the composition than is necessary. Often, as shown in Marina on the Argyll Coast, a certain amount of restraint is required in order to achieve the most effective result. For this subject I decided to build the composition around the triangular sail, exploiting the repetition of the vertical masts and the angle of the three boat shapes and their reflections. The same considerations were true for Ardfern Marina, Argyll. By focusing in and selecting just the right relationship of shapes, I was able to create a more dynamic composition.

Marina on the Argyll Coast

OIL ON BOARD

23 × 30.5cm (9 × 12in)

“Marine subjects offer lots of interesting shapes and reflections to work with. I decided to use the triangular sail as the main feature in this painting.”

From my studio it is only a short trip into the Yorkshire Dales or the Peak District, where I can find open landscapes as well as more intimate rural scenes that are always inspirational. An Old Courtyard, Worsborough Mill, for instance, is typical of the quiet, almost forgotten type of farmyard subject that I love to paint. Although the barns in the background were fairly ordinary, for me, the scene was transformed by the inclusion of the old cart with its sun-bleached patina and, in consequence, in total harmony with its surroundings. It was the perfect subject for a small plein-air oil painting on board, using a limited palette and working with confident, expressive brushstrokes and blocks of colour.

This was a painting in which much depended on the success in handling a particular feature, in this case the cart, which required some sound drawing and the skilful application of perspective. Observation, a degree of simplification and experience all count in such situations. If you are not sure about painting something like this straight away, then start by making a separate drawing.

Climbers by the Great Slab, Millstone Edge

OIL ON CANVAS

61 × 51cm (24 × 20in)

“I often paint in the Peak District, which always impresses me with the majesty and timeless quality of its wonderful rock formations.”

An Old Courtyard, Worsborough Mill

OIL ON BOARD

30.5 × 40.5cm (12 × 16in)

“Rural scenes like this are now very hard to find, but they are one of my favourite subjects.”

For the more traditional landscape subjects, I quite often choose a scene in which there is a high horizon and the potential in the foreground to include an interesting feature that will entice the viewer into the painting. On a clear, winter day, driving across the North York Moors I found just the kind of subject I like and made the pochade-box study, Sunlit Lane, West Barnby. With its incredible composition, scintillating light effect and wonderful tree shapes, this was a really poetic and magical subject to paint.

In contrast, if conditions are favourable, sometimes I opt for a more ambitious approach and work on a larger scale, as I did for Climbers by the Great Slab, Millstone Edge, which was painted on a 61 × 51cm (24 × 20in) canvas. The Derbyshire Peak District is one of my favourite climbing areas and, as an artist, what particularly impresses me is the timeless quality of those great tors, which is something I try to capture and celebrate in my paintings. As a subject, the gritstone rocks are full of potential in terms of colour, tone and texture.

Sunlit Lane, West Barnby

OIL ON BOARD

20 × 30.5cm (8 × 12in)

“The combination of light and composition made this a magical subject to paint.”

With its low light, long shadows and subtle blues, greys and purples, I love the winter landscape. True, it demands more resolve to paint outside in the winter, but however cold and whatever the weather, I venture out almost as much in the winter months as I do in summer, if for shorter periods. For these landscape paintings, as with all others, I look for subjects that offer a strong sense of form and structure, together with interesting qualities of light and colour.

In winter, the form of the landscape is much more evident, having lost the pervading green growth that masks everything and characterizes the summer woods and fields. I especially like the structure of winter trees, for example. If there are greens, I will usually underplay them, as I do in a summer landscape subject. The fact is that greens can so easily become overpowering and too vibrant in a painting, spoiling its credibility and impact. So my advice is always to mix greens rather than rely on colours such as Hooker’s green or emerald green used in their raw state. If I start with olive green, for instance, I will probably add some raw sienna and a little lemon yellow.

Winter Landscape, Everton is a good example of a subject that is full of interest and appeal in the winter, when the bare forms of the trees are showing, but has little to offer in the summer, when everything is lost under a canopy of green. Working in oils on a small, prepared board, my aim was to capture the essence of the fleeting light effect. I particularly liked the way this was enhanced by the reflected light in the pools of water in the foreground. Painted entirely on site, this little study took about 45 minutes.

For the much larger painting, The Old Vicarage, Misson, I was able to return on three consecutive fine days in February, working between about 11am and 1.30pm, when the light was at its best for bringing out the contrasts in form and tone. For Old Cottage Backs, Ledsham, which is also a large painting, an early watercolour, I kept to a limited palette and broad washes of colour. Note how the foreground in this painting is very simple indeed, essentially a single wash of colour, but there is just sufficient tonal change to create interest and lead the eye into the painting.

Winter Landscape, Everton

OIL ON BOARD

20.5 × 30.5cm (8 × 12in)

“I prefer trees in the winter when their form and structure is much more obvious and, in my view, more interesting to paint.”

The Old Vicarage, Misson

OIL ON CANVAS BOARD

40.5 × 40.5cm (16 × 16in)

“Sometimes it is possible to return to the same spot on two or three consecutive days and so attempt a larger and more resolved plein-air work, as here.”

Old Cottage Backs, Ledsham

WATERCOLOUR ON PAPER FROM A SAUNDERS WATERFORD WATERCOLOUR BLOCK

57 × 77.5cm (22½ × 30½in)

“An early watercolour, worked with bold washes over an initial drawing.”

It requires confidence and skill to paint people and place them well in a composition, particularly if they are going to be the main feature of the work. The key to success lies, of course, in observation and sketching people – in cafés, shops, stations and so on – and building up a useful resource of figure studies in this way. Life-drawing classes are also extremely beneficial in helping to understand how to capture pose, movement and character.

Presentation of the Colours by HM The Queen, The Duke of Lancaster’s Regiment 2008

OIL ON CANVAS

96.5 × 132cm (38 × 52in)

“This was a commissioned work, which had to meet certain criteria.”

Sally by the Fireside

WATERCOLOUR ON BOCKINGFORD PAPER

25.5 × 51cm (10 × 20in)

“This is another early watercolour study. Quick studies like this are good for building confidence with figure work, as well as developing painting techniques.”

Letitia at the ROI 2007

OIL ON CANVAS BOARD

51 × 51cm (20 × 20in)

“I like my portraits to have similar qualities to my other subjects, in that I want to create a likeness but achieve this in a loosely described way rather than a highly detailed one.”

Sometimes it is the particular grouping or action of figures that is the attraction of a subject and I will paint such a grouping on site, as at Henley Regatta, for example, which I visited for a number of years. In other paintings I often ‘introduce’ a figure or figures, if I think this will add to the overall interest of the work and impact of the composition. Figures are an ideal means of creating a focal point in a painting and giving a sense of scale.

As well as landscapes and other scenes in which figures are included, equally I enjoy painting portraits and life studies. In a portrait, as in Letitia at the ROI 2007 , I aim for a likeness, but loosely described. On the other hand, for a commissioned work such as Presentation of the Colours by HM The Queen, The Duke of Lancaster’s Regiment 2008, the content is governed by an initial brief. This painting was a wonderful challenge: it had to somehow honour the sense of event and ceremony, while including 12 to 15 identifiable people, with of course Queen Elizabeth II as the most prominent figure. A large, studio painting, it took me over five weeks to complete, working from the photographs, notes and drawings that I made on location, plus the necessary research to ensure that every detail was correct.

Towns and cities offer many different possibilities for paintings, from the compact, intimate subject to the more ambitious townscape with its sense of scale and atmosphere. Again, selection is a key factor in creating a successful painting and my advice is to look for a group of buildings that has an interesting skyline but that will equally give adequate foreground activity. As well as the various practical considerations when painting on site – and particularly in this case finding somewhere to work that won’t attract too much attention from passers-by – you need to assess the degree of challenge and whether tackling it seems feasible in the time available. Alternatively, will the subject provide good reference material for subsequent studio work?

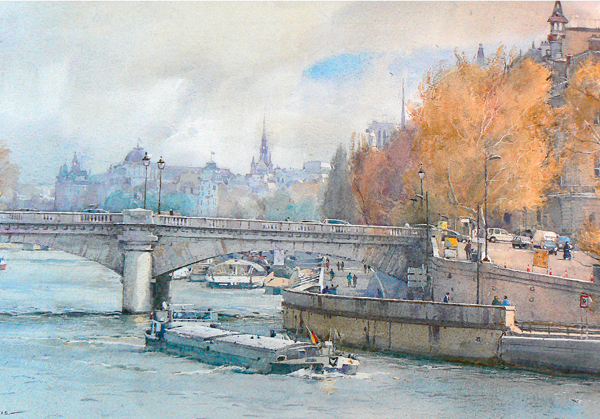

Lower Regent Street, London and Barges on the Seine, Paris show two contrasting approaches to painting city views. Lower Regent Street, London, which in fact was a demonstration painting that I made for a film, was produced in very difficult conditions in one of the busiest parts of London. Being essentially an architectural subject, it required some careful drawing, but, given the constraints of time and so on, I kept the colour work to mainly single, variegated washes. For the white buildings, I exploited the whiteness of the paper, adding shadows where necessary, although not loading the colour too high. Mainly, it is the sky area that defines and enhances the shapes of the buildings. I especially liked the way that the big tree shapes on the right of the composition acted as a foil for the rigid structure of the buildings opposite. It was an interesting painting to produce: loose, descriptive and all the more charming for its rawness, I think.

Barges on the Seine, Paris

WATERCOLOUR ON ARCHES PAPER

57 × 77.5cm (22½ × 30½in)

“Comparative scale and the overall balance and effectiveness of the composition are points to keep in mind when working from reference material for a view such as this.”

Lower Regent Street, London

WATERCOLOUR ON ARCHES PAPER

28.5 × 39cm (11¼ × 15¼in)

“The challenge of painting a busy city scene like this requires all one’s skill and application.”

Contrastingly, Barges on the Seine is a fully resolved watercolour that I made in the studio working from all forms of reference and my memories and experience of the scene. In fact, I used elements from different photographs, taking care over the appropriate scale and positioning of everything (for example, the barges in the centre and far distance), to maximize on the interest and impact of the composition. As with Lower Regent Street, London, this painting started with some serious, careful drawing. Then, after applying an overall ‘ghost’ wash to indicate the basic shapes and colours, I worked with a succession of washes and other techniques to build up the necessary contrasts of tone, colour and surface qualities.

As I have discussed here, I enjoy the challenge of different types of subject matter and, wherever I am, essentially I will be looking for the same qualities in the subjects that I choose – originality, dynamic design and an interesting effect of light. Governed by the fact that all the materials and paintings will have to be packed and transported by plane, I suppose the only difference when painting in Europe is that I usually work on a smaller scale – now, mostly in watercolour rather than oils – and produce a greater proportion of reference studies rather than finished paintings. Additionally, I make some adjustments to the colour palette – to include more yellows and ochres, for example – to suit the warmth and higher colour key of many subjects found in Italy, Spain and France.

Café Study, Barcelona

OIL ON BOARD

38.5 × 28.5cm (15¼ × 11¼in)

“Counter-change effects – light shapes against dark and dark against light – always add to the appeal of a subject.”

Piazza Navona, Rome

OIL ON BOARD

20 × 30.5cm (8 × 12in)

“When there are lots of figures coming and going, select and act quickly to place those that you think will enhance the composition.”

In Café Study, Barcelona the people are there, enjoying their coffee in the sun. I liked the contrast in scale in this scene, between the figures and the magnificent archways above, and also the contrasting light effects. There is a lot of counter-change – light shapes against dark and vice versa. Archways can be very difficult subjects to paint, particularly when taking a face-on view, as here. To avoid making the archways look too balanced and in consequence perhaps reminiscent of giant cricket stumps, I decided to break the view half-way across the second arch. You will also see that I have made full use of the canopy on the left to cut across the first arch and so interrupt the strong vertical element of the composition.

Piazza Navona, Rome is a good example of a scene in which figures are constantly coming and going. You have to quickly place those that will be of value to the composition, or alternatively compile others from various references – using the arms from one figure, legs from someone else and so on. The most important consideration with figures in this sort of context is scale: they must be the right size relative to their surroundings and their placing, whether close-up or further away, in the painting.

Although I regularly make painting trips to various parts of the UK and abroad, sometimes I find excellent subjects right on my doorstep. The Old Willows by the Idle, Misson is a good example. It is a location near Doncaster, quite near where I live, and a familiar subject that I have painted on many occasions, at different seasons of the year – once in a snowstorm. This painting was made entirely on the spot, working with a loose watercolour technique on a small sheet of Arches Rough paper.

My first step was to assess the nature and content of the subject and consider this in relation to the conditions of the day and the time available. This was a windy day in late spring. I knew I had to work quickly and that the most challenging aspect of the painting would be dealing with the various greens across the foreground area and in the large trees. I judged that the best approach would be to tone down the greens and simplify these areas; otherwise the effect would be too vibrant and disjointed.

Once I had decided on the composition and had made the necessary drawing, I applied the initial ‘ghost’ wash (basically a variegated wash of blues and greens) and began to superimpose washes over this to suggest the form of the trees, shadow areas and so on. Essentially, the whole painting was dependent on that first, general variegated wash and, consistent with the lively, spontaneous effect that I wanted, I decided to keep everything broadly stated – the river, for example, and the distant church tower. It was a good exercise in creating the most impact from a fairly ordinary subject, through economy of means and the expressive use of paint.

Old Willows by the Idle, Misson

WATERCOLOUR ON ARCHES PAPER

28.5 × 38.5cm (11¼ × 15¼in)