As a figurative painter wanting to create results that are consistently expressive and individual, there is no doubt in my mind that the best approach lies in combining both plein-air work and studio painting. Although quite different in terms of the working process and, in consequence, the nature of the finished pictures, the two methods complement each other perfectly. The immediacy and emotive quality of plein-air work encourages similar objectives in studio paintings, which helps prevent them becoming laboured. In its turn, the more in-depth study from studio painting informs the speed of decision making and technique necessary when working on site.

Barn Interior, Brampton-en-le-Morthen

WATERCOLOUR ON TWO RIVERS TINTED PAPER

28.5 × 38.5cm (11¼ × 15¼in)

“This old tithe barn of immense height suggested a portrait-style format to achieve a real sense of drama and scale.”

I like the adrenaline rush and the uncertainty when you are outside: you have to be so alert and responsive to the subject matter. In contrast, in the familiar environment of the studio, there is much more time to explore ideas in some depth. But, whatever the approach, one of the most important factors in influencing the impact and success of the work is the ability to create and preserve passages of brushwork that are spontaneous and descriptive. With experience you learn to leave well alone, avoid overworking such areas and to appreciate your best-quality brushwork effects, for it is those areas that will most enliven a painting and attract interest.

The necessity for painting trips might depend on where you live, your degree of experience or the particular subjects that interest you. But it is always interesting to find new places and ideas and give the familiar locations a rest for a time. I enjoy painting trips and seem to travel more these days. On a recent trip to Pembrokeshire, for instance, I produced between eight and ten paintings on site, and on another trip, to Mallorca, I painted in 14 or so locations.

A potential danger with new locations is that, because time is at a premium, you may feel under pressure to find something to paint and, in doing so, make hasty choices that fail to live up to expectations. Remember, whatever the subject, it must ‘move’ you. I am fortunate in that I can adapt to new places quickly. Soon after I arrive at a new location I like to wander round and make a mental note of subjects that I would like to paint over the coming days. I establish a plan of attack!

Beckside Moorings, Staithes

WATERCOLOUR ON ARCHES ROUGH

28.5 × 38.5cm (11¼ × 15¼in)

“I never tire of painting at Staithes in North Yorkshire: I still manage to find interesting views, such as this one.”

From Across the Beck, Staithes

OIL ON BOARD

25.5 × 30.5cm (10 × 12in)

“Whether it is a familiar location, as in this painting, or a new area, I like to spend a short while wandering around to get an idea of the best subjects to paint.”

Whatever type of location work you are thinking of, it is always worth doing some preliminary planning. I would advise that you travel light – there will be greater opportunities to explore the area and find the more unusual subjects, away from the obvious tourist spots. The essential equipment that I recommend is: a sketching easel; a sketchbook and several soft graphite pencils; a watercolour pad or block with a small selection of paints and brushes and/or a pochade box with the basic materials for oil painting; and the necessary accessories, such as a water container, rags and turpentine.

While you don’t want to be encumbered by things that you are not going to use, equally, try to ensure that you don’t leave a vital piece of equipment at home – and in consequence find that you are limited in the sort of work you can attempt. Your choice of materials and equipment will obviously depend on the location and how you are going to travel there, how long you intend being away, the likely subject matter and your aims and objectives.

For my trips in the UK I travel by car, and therefore I am not so restricted in the quantity and variety of materials that I can take with me. I always take a pochade box and my big box easel, which has the advantage of being more stable than the lightweight sketching easel. Other equipment will include a good choice of prepared boards for oil painting, plus a Saunders Waterford block and six 600gsm/300lb stretched sheets of 28.5 × 39cm (11¼ × 15¼in) Arches Rough paper for watercolours. Also, I take a Binning Munro style palette and a bijou watercolour box.

If I have to walk for some distance along the coast or across the countryside, I carry a smaller selection of materials in a rucksack, with a folding stool and a sketching easel. Alternatively I just sit on the ground, working from a pochade box. When flying to Europe, I keep to the minimum of materials. If I am working in oils, I substitute alkyd colours for some of the slower drying oil colours (cerulean, raw sienna and titanium white), thinning and mixing the colours with Sansodor rather than turpentine.

I know that photographs can be an enormous help to artists in providing specific details and information about the subject matter, but in my view they are no substitute for sketches and studies made on site. I think it is a pity that so many artists now rely principally on the camera as the means of recording ideas and information, rather than their sketchbook.

In fact, if you work only from photographs, the results, although perhaps very lifelike, will almost inevitably be unoriginal and soulless. What they will lack is the interpretation of the artist – this can only come from experiencing the subject matter and, ideally, getting to know it through observation and drawing. I still make sketches: there is no way I could have considered painting the cart, shown in Study with Pony Trap, for example, without first making that drawing.

Both Study with Pony Trap and Old Stables, Marr Hall Farm are drawings made with a Flomaster pen. I used to draw a lot with this type of pen. It had a pump action, which meant that I could let it run slightly dry when I wanted to include soft-toned lines and shaded areas. Then, if I gave it a couple of pumps, the ink would flow dark again. With this sort of drawing is that you can be selective and specifically focus on the elements and qualities that will be helpful in the subsequent painting. For Portrait Head of a Boy I used a very soft pencil, which I still think is one of the simplest, quickest and most reliable ways of making a tonal reference sketch.

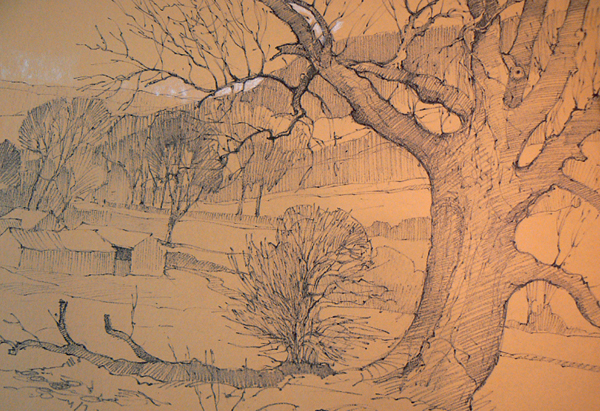

Tree Study, Wentbridge Valley

LINE DRAWING, FINE FELT-TIP PEN ON TONED PASTEL PAPER

57 × 78.5cm (22½ × 31in)

“Sketches like this are very helpful in exploring the tonal contrast of a subject as a preliminary to painting.”

Portrait Head of a Boy

PENCIL ON CARTRIDGE PAPER

38.5 × 28.5cm (15¼ × 11¾in)

“Drawing skills are fundamental to creating convincing paintings.”

Old Stables, Marr Hall Farm

FLOMASTER PEN

23 × 29cm (9 × 11¼in)

“Here, the drawing has helped me select and focus on those parts of the subject matter that I think will make the most interesting painting.”

Study with Pony Trap

FLOMASTER PEN

23 × 29cm (9 × 11½in)

“A quick sketch such as this is useful to establish the likely problem areas of the subject and how best to organize the composition.”

La Tanca de C’an Gaillardo, which I painted when I was staying at a villa in Mallorca, demonstrates my typical working process for plein-air subjects. It was a subject that I hadn’t noticed until almost the end of my stay, but seeing it in the strong, morning sunlight I felt straight away that it would make a good painting. I liked the quality of light, especially on the old olive tree and the building (which, incidentally, was a sort of veranda designed for barbecues). Also, I thought that the composition would work well and, given the particular shapes and textures, that I could achieve the greatest impact with oils, rather than watercolour.

I chose a board prepared in the usual way – first with a coat of gesso primer and then with one of gesso primer mixed with texture paste – and then given a turpsy, bluish wash to block out the white surface and provide a suitable unifying tone to work over. Working quickly, with a No. 1 worn bristle brush and a weak mix of raw sienna and French ultramarine, I placed the main shapes and some of the important dark tones, as you can see in Stage 1.

From this starting point, I went on to develop the composition and main tones in a more positive way in Stage 2, essentially considering the basic tonal relationship between the sky, building, foliage and foreground, mostly working with yellow/green and olive green/grey mixes. I knew that the light would change quickly and therefore alter the shadows, so I needed to identify those at this stage. Working with blocks and patches of colour, my aim was to create a sense of the whole painting and to define the composition, before the build-up of paint made it much more difficult to adjust things.

My colour palette for this painting included Naples yellow light, Naples yellow, Indian yellow and buff titanium (all of which are very useful when painting in Europe and help speed up the mixing process), French ultramarine, burnt sienna, cadmium red, cadmium orange and titanium white. I also used two alkyd colours, raw sienna and cerulean blue, which were chosen because they would dry faster than their oil colour equivalents.

La Tanca de C’an Gaillardo

LOCATION PHOTOGRAPH

Stage 1

“With a No. 1 worn bristle brush, I quickly roughed-in the basic composition and some of the important dark tones.”

Stage 2

“Mostly working with blocks of yellow/green and olive green/grey mixes, I began to consider the tonal relationships throughout the painting.”

Stage 3

“I continued with some attention to the foreground, particularly focusing on the colourful plants and how they created a link with the rest of the composition.”

Stage 4

“Next, I balanced the tones and colours of the foliage with those of the foreground.”

Stage 5

“With small touches here and there to enhance some of the tones and details, I reconsidered the building and foreground areas.”

Next, as shown in Stage 3 I began to consider the foreground, still working with fairly dry paint. One of the most attractive features of this subject, I thought, was the way that the colourful Mediterranean plants in the foreground led the eye up and into the rest of the composition, linking with the angle of the building and that of the interesting, tortuous tree. Also at this stage, I added more touches here and there to adjust the tones and enhance the sense of form, as in the tree, for example.

And essentially this prepared the way for the latter stages of the painting, in which the various adjustments and developments were made always with the whole composition in mind. In Stage 4 I worked on the top right-hand corner to bring out the lightest parts of the foliage. Similarly on the left, I started to define the branch shapes, now also aiming to create more distinction between the foreground and middle distance.

“Detail, showing the figure and the loose brushwork technique.”

“Detail, showing the expressively drawn strokes to suggest the flowering plants in the lower right-hand area of the painting.”

After further work on the wall of the building in Stage 5, I added a few more high-key touches of colour to the foreground, including a hint of Indian yellow. I then concentrated on the seated figure. I felt that the final painting, La Tanca de C’an Gaillardo needed the figure to add life and a sense of scale. Back in the studio, after assessing the painting and looking at my reference photograph, I made some final adjustments – mostly to the figure, to make it a little more believable – and by enhancing the darks, to increase the overall visual ‘punch’ of the painting.

La Tanca de C’an Gaillardo

OIL ON BOARD

30.5 × 40.5cm (12 × 16in)

“I added the seated figure and, after returning to the studio, made a few final adjustments, mostly to enhance the darks.”

Inevitably, for larger and more resolved paintings, it is necessary to work in the studio. The success of this approach will depend mainly on two things: the strength of the reference material and whether it provides enough useful information to work from; and also, of course, your skill in using the information available and enhancing it with your own experience, imagination and expression.

Reference sketches do not have to be elaborate and highly detailed. Most artists develop their own ‘shorthand’ sketching technique, which enables them to jot down the key features of the subject quickly, perhaps also with written notes, as a reminder of what to focus on in the studio painting. Often my sketches consist of only a few lines, giving me just enough information from which to assess the strength of the composition.

Ideally, as well as referring to sketches, colour notes and photographs, it helps if you can work from memory to ‘relive’ the scene and so paint it with some feeling. Also, it is very useful if you can train your memory to help with the inclusion of figures, for example, and other points of interest in a painting. I will often add small figures, such as those in Sharp Morning Light, Sandsend, based on those I observe at the time, but also painted from memory and suggested with just two or three sensitive brushstrokes.

Sharp Morning Light, Sandsend

OIL ON CANVAS

61 × 76cm (24 × 30in)

“I often add small figures from memory or from sketchbook studies.”

Matthew by the Millpond, Monk’s Mill

OIL ON BOARD

30.5 × 35.5cm (12 × 14in)

“The particular handling qualities of oil paint were perfect for capturing the atmosphere of this quiet, intimate subject, which then acquired further impact by the late inclusion of the figure.”

Although the working process is quite different, as with the plein-air paintings, always the most important quality that I want to achieve in my studio work is a sense of mood and place. Something that helps me a great deal in this respect is the fact that, even in the winter months, I often paint outside and therefore I never really lose touch with that sort of experience – I am able to maintain something of its sense of immediacy and feeling when I am working in a more considered way in the studio. The danger in working in the studio, as I have previously mentioned, is inadvertently overstating an idea, so that there is nothing left for the viewer’s imagination. A painting needs areas of mystery; unresolved areas as well as skilfully defined ones.

So, in my studio paintings I try to hold on to the lively, emotive response that I would enjoy outside, but I also adopt techniques that will help keep the paintings loose and expressive. With oil paintings, for example, I keep the amount of preliminary drawing on the canvas to the minimum number of marks, as a detailed drawing is more likely to encourage a fussy, tighter approach in the actual painting. With watercolours, although I often need to start with a carefully planned composition and drawing, I aim to keep the subsequent washes as loose and fresh as possible, creating contrasts between broadly treated and fully resolved areas. For me, the most successful studio paintings will be important, serious works that show my technique to the full, yet nonetheless look as though they were painted in situ.

Curiously, an aspect that is sometimes overlooked in paintings is the potential of the paint medium itself to add interest, vigour and feeling to the work. Each type of paint has its own distinctive properties and characteristics, which are always qualities to exploit when aiming to express ideas with individuality and feeling.

Here is a good example of how the two different media, oil and watercolour, and the two different working methods, plein-air and studio painting, can complement each other. This painting was made in the studio, working in oils, but using a previously painted plein-air watercolour as the principal source of reference. In fact, I started the painting as a demonstration piece, but could only take it so far in the limited amount of time available. So I took it back to my own studio to complete it. The view is from the bridge at Staithes in North Yorkshire and, as well as the watercolour, I had some other reference material to provide more detailed information about the boats.

I always start with an underpainting when I am working in oils, essentially applying a turpsy wash of colour, quickly and loosely, to establish a tonal reference to work from. Depending on the subject matter, I may decide to start on a prepared, dry, underpainted surface or, as for this painting, apply a wet underpainting and then immediately rub out the white or very light areas with a rag. Thereafter, for plein-air subjects – such as Matthew by the Millpond, Monk’s Mill, for example – the process is very much a ‘one-hit’, alla-prima one. For studio paintings, I adopt the traditional ‘fat-over-lean’ technique, building up effects with increasingly thicker paint.

This painting follows that approach, working with closely observed, carefully controlled layered brushwork, developed over several days. It is a painting all about light – glancing light, extreme light, reflections, lost and found, deep shadows and so on – which is a subject that I always find fascinating and challenging. Crisp Spring Afternoon, Staithes is an appropriate painting to conclude with, I think, because not only does it demonstrate the value of developing experience in both plein-air and studio work, but also it shows that, whatever the subject, given the right emphasis on composition, mood and interpretation, you can create an image of real interest and impact.

Crisp Spring Afternoon, Staithes

OIL ON CANVAS

45.5 × 61cm (18 × 24in)