(1144–1300)

In the twelfth and thirteenth centuries in Europe, many people had a sense that disaster was just a step away. Life was precarious for rich and poor alike. It was a time when most babies died before their first birthday of diseases that are easily cured today. Few of those who survived their childhood lived much beyond their 30th birthday. In times of fear and anxiety, it is all too easy to blame “them”—the people who are not like “us”—for every tragedy, every hardship, and every loss.

During these years, Jews were under attack almost everywhere in Europe, not for who they were or even for what they believed but for what others imagined Jews were like and what they imagined Jews believed. Those imaginings led to myths that had horrific consequences for Jews then and in centuries to come. One of the most dangerous involved the accusation that Jews killed Christian children as part of their Passover ritual. This myth had its beginnings in an incident that took place in the twelfth century.

On Good Friday in 1144, a forester stumbled upon the corpse of a young boy named William in a woods just outside of Norwich, England. According to a book written some years later by a monk and chronicler known as Thomas of Monmouth, “Becoming aware that [the boy] had been treated with unusual cruelty, [the forester] now began to suspect, from the manner of his treatment, that it was no Christian but in very truth a Jew who had ventured to slaughter an innocent child of this kind with such horrible barbarity.”1

William’s relatives agreed with the forester. His uncle angrily informed church authorities that “the Jews” had committed the murder because of their unrelenting hatred for Christians. He proclaimed, “I accuse the Jews, the enemies of the Christian name, as the perpetrators of this deed and the shedders of innocent blood.” As proof, he described a dream his wife had had a few weeks earlier. In that dream, Jews attacked her in the marketplace and tore off one of her legs. The couple now interpreted the dream as a warning that she would lose a loved one because of the Jews.

Most people in Norwich in 1144 ignored these charges or attributed them to grief at the loss of a beloved child. After all, Jews had been living in the city for about 100 years without a single incident. Many in the town also realized that despite the accusation, there was no proof that a Jew was responsible for the boy’s death. William was buried, and life in Norwich continued as usual until about 1149, when Thomas of Monmouth came to live in a monastery there.

Thomas quickly became obsessed with the murder. He was convinced that William was not a victim of random violence but a martyr who had died for his faith. He wrote a book about William’s death, hoping to have the boy declared a saint. Thomas based his book on stories told by four people—two of whom he never met.

The first story was a deathbed confession by Aelward Ded, one of the richest men in Norwich. In 1149, Aelward told a priest that he had seen a Jew named Eleazar and another man walking with a horse early on the day William’s body was discovered. On the horse was a huge sack. Curious about its contents, Aelward touched it and felt a human body. When the two men realized that Aelward knew their secret, he claimed, they fled into the woods with the sack.

Aelward told the priest that he had never told this story to a single person. But, he claimed, Eleazar and his companion had confessed the murder to the sheriff. They then bribed him to keep their secret and to force Aelward to do the same. Aelward spoke out only as he lay dying—three years after Eleazar’s death in 1146 and the sheriff’s own death shortly thereafter.

Thomas of Monmouth’s second story came from William’s aunt, who now came forward to say that William had come to see her on the day of his disappearance. With him that day was a cook who had offered the boy a job. Suspicious of the cook, the aunt asked her daughter to follow the pair when they left. The little girl told her that William and the cook entered Eleazar’s house and that the door closed behind them. The girl died before Thomas came to Norwich, so he had only her mother’s word for the story. Still, it appeared to connect Eleazar to the child.

The aunt’s account revealed a gap in the complicated story that Thomas was weaving. What had happened to William between the time he supposedly entered Eleazar’s house and the discovery of his body in the woods several days later? Once again, Thomas found a witness, this time a Christian woman who, in 1144, had worked for Eleazar as a servant. She claimed that on the day William disappeared, Eleazar had ordered her to bring him a pot of boiling water. When he carried the pot into another room, she peeked through a crack in the door to see what he did with it. She told Thomas that it was then that she saw a boy tied to a post.

Like Aelward, the woman had up to that point told no one what she had seen. According to Thomas, she was afraid she would lose her job. She also feared for her life, because she was “the only Christian living among so many Jews.” This was an odd comment in a community that had no Jewish quarter; for the most part, Jews and Christians in Norwich lived side by side.

Thomas’s most prized, and most amazing, testimony came from Theobold, a monk who was nowhere near Norwich in 1144. Theobold told Thomas that he had been born a Jew and had converted to Christianity because of William’s martyrdom. He claimed that he and every other Jew in England in 1144 knew that a boy would be killed in Norwich on Good Friday. According to Theobold, prominent Jews gathered in Spain just before Passover each year to determine where a Christian child would be sacrificed. Jews who lived in the selected country drew lots to decide exactly where the crime would take place. In 1144, England was the country selected, and Norwich was the town.

Thomas never doubted Theobold’s story, even though it required believing that thousands of people throughout England and the rest of Europe and the Middle East had kept, and continued to keep, a lifelong secret. It did not strike him as surprising that no one had ever revealed that secret—with the single exception of Theobold. Why would Jews risk their lives to commit such a murder? Theobold claimed that they did it to show their contempt for Christianity and to take revenge for their exile from their homeland.

Thomas added his own twist to Theobold’s tale. He insisted that Jews did more than just kill their victims; they reenacted the crucifixion of Jesus. In his book, he described the scene as he imagined it:

[The Jews] laid their blood-stained hands upon the innocent victim, and having lifted him from the ground and having fastened him upon the cross, they vied with one another in their efforts to make an end of him…. [I]n doing these things they were adding pang to pang and wound to wound, and yet were not able to satisfy their heartless cruelty and their inborn hatred of the Christian name, lo! after these many and great tortures, they inflicted a frightful wound in his left side, reaching even to his heart, and as though to make an end of all they extinguished his mortal life so far as it was in their power. And since many streams of blood were running down from all parts of his body, then, to stop the blood and to wash and close the wounds, they poured boiling water over him.2

Accusations of ritual murder were not new. In the first century of the Common Era, Apion, a Greek lawyer in Alexandria, Egypt, claimed that once a year Jews kidnapped a Greek and fattened him up so that he could be sacrificed to their deity. However, Apion never cited a specific example of such a murder; he wrote in vague, general terms, and his accusation was one of many wild charges that people from various ethnic groups at that time made against others. A few generations later, the Romans would make similar accusations against Christians. Once again, few people at the time paid attention to such charges; they were seen as too outrageous to be true.

In the twelfth century, however, accusations of ritual murder did not seem so outrageous; instead, they seemed to confirm what many people already believed about Jews and Judaism. When William died, the Crusades had been going on for 50 years, and the speeches and sermons that persuaded people to join the crusaders’ armies blamed Jews as well as Muslims for the “loss” of Jerusalem and for any attack on Christians or their beliefs.

Changing attitudes toward Jews were reflected in images found in churches. At a time when few people could read and write, churchgoers “read” the story of Jesus’s life and the founding of the Christian church in stained-glass windows, murals, and altar paintings.

A popular image in many churches showed two women standing next to the cross; one woman represented the church, and the other woman, the synagogue. In the tenth and eleventh centuries, the two women looked much the same, though the artists clearly favored the one who represented the church. By the twelfth century, however, the synagogue was no longer shown as an attractive woman who was simply unable to see the truth of Christianity. Increasingly, she was portrayed as both blind and depraved—a woman with ties to the devil. The shift in the image of the synagogue mirrored the way Christians came to view real Jews in their communities, while also reinforcing negative feelings about them.

We do not know for sure why Thomas of Monmouth put together the web of false accusations about William’s death or why the others involved told lies about how the boy lost his life. Were they making themselves feel important by sharing their fears and suspicions? Were they protecting someone else who might have killed William? Did they truly believe the stories they told, or did they make them up for reasons we will never know? Whatever motives these people had, the story that Thomas of Monmouth told about William’s murder spread like wildfire.

Images that showed the church as superior to the synagogue appeared not only in sculptures, stained-glass windows, and tapestries but also in the artwork that adorned books and manuscripts.

By 1150, crowds of pilgrims were visiting William’s tomb each year, and some were claiming that he performed miracles. Such claims inspired even more people to visit the boy’s tomb in the hope of obtaining miracles of their own. The pilgrims who flocked to Norwich are proof of the success of Thomas’s campaign to win sainthood for young William and fame for his own monastery. But the myth he created and spread had other long-term consequences. His invented tale further reinforced the image of Jews as evil and depraved—people who hated Christians so much that they would stop at nothing.

Thomas of Monmouth’s accusations of ritual murder were not the last made against the Jews. In 1147, Christians in Würzburg, Germany, also accused Jews of murdering a Christian. In 1168, similar charges were made in Gloucester, England, and the same happened a few years later in Paris. By the end of the twelfth century, the lie had spread throughout Europe.

The Jews of Blois, a town in France, were among those specifically accused of ritual murder. Their experience reveals the power of the myth Thomas of Monmouth created.

On a spring day in 1171, a Jewish tanner was walking along the banks of the Loire River. He was carrying a bundle of raw animal hides when he encountered the servant of a town official. As the two men passed one another, one of the skins dropped out of the tanner’s bundle and fell into the river. The servant immediately assumed it was a corpse and ran to tell his master the news.

It seems that neither the servant’s master nor any other Christian in town doubted the story, even though they had no evidence that any crime had been committed, let alone a ritual murder. After all, the tale was in keeping with what many already believed. The count of Blois also accepted the story as fact; he imprisoned all Jewish adults in the city and ordered their children baptized as Christians.

Blois was not, of course, the first place where a Jew was accused of ritual murder. It was, however, the first known place where Jews were punished for a crime that had not even occurred. Jewish leaders pointed out that there was absolutely no evidence of a crime; no one was missing and no body had been found. The count refused to reconsider his position. In exchange for a payment of 1,000 pounds, however—a fortune in those days—he did promise not to arrest Jews who lived in the area around the city.

On May 26, the Jews held in prison were given a choice: conversion or death. Eight or nine chose to be baptized. Most of the rest were herded into a hut and burned alive. When a few men managed to escape, the executioners killed them with swords and then pushed their bodies back into the fire. Almost all of the Jews of Blois—more than 30 men and women in all—died that day.

While little is known about the way Jews in most European cities reacted to news of an accusation of ritual murder, Blois is an exception. Historians have found several letters that Jews in neighboring towns wrote in 1171. The first were from Jews in Orléans, the city closest to Blois. After hearing two eyewitness accounts, they wrote letters to Jews in communities throughout northern France and what is now Germany. The letters described the events in Blois and asked for help in protecting Jews from similar libels. In Paris, a group of influential Jewish leaders persuaded King Louis VII to publicly condemn the actions of the count of Blois. In addition, Louis ordered his own officials to provide his Jewish subjects with better protection.

Jews also appealed to the count of Champagne, a brother of the count of Blois. The count of Champagne responded by saying publicly, “We find nowhere in Jewish law that it is permissible to kill a Christian.” His statement was intended to deny the accusation that Judaism encourages the murder of Christians. When charges of ritual murder were made in the lands he ruled, he refused to act on those charges.

In the meantime, Jews continued to negotiate with the count of Blois. Although most of the Jews in Blois had been burned alive in May, a few remained in prison. A number of Jewish negotiators tried to win their release and secure permission for converts to return to Judaism. They worked mainly through another of the count’s brothers, the bishop of Sens. Nathan ben Meshullam, one of the negotiators, wrote of those efforts:

Yesterday I came before the bishop of Sens, to attempt to release those imprisoned by his brother, the wicked count, and those forcibly converted. I paid the bishop… 120 pounds, with a promise of 100 pounds for the count, for which I have already given guarantees. The count then signed an agreement to release the prisoners from confinement. Concerning the young people forcibly converted, he asked that they be permitted to return to [Judaism]…. He also signed an agreement that there would be no further groundless accusations.3

This letter reveals how the count was able to manipulate the situation to his own financial advantage. It also reveals how precarious life was for Jews. The best that the Jews of northern France could hope for was to save the lives of a handful of survivors in Blois and ask that nothing comparable happen again. They were unable to secure justice.

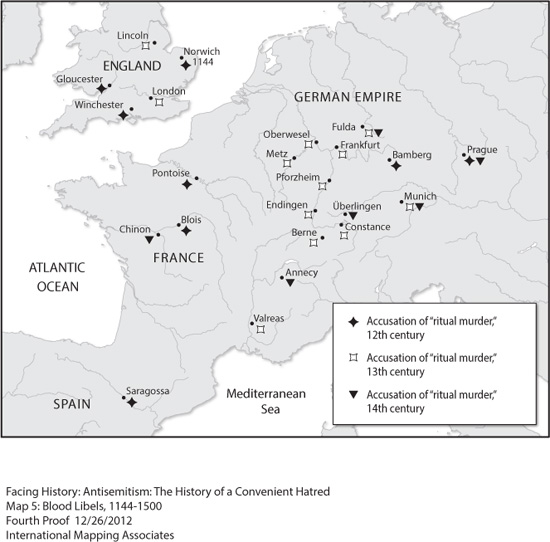

By the end of the twelfth century, Christians in eight cities had accused Jews of ritual murder—two each in England, France, and the German-speaking countries, and one each in Bohemia and Spain. By the end of the thirteenth century, the number of known accusations had more than tripled. And by the sixteenth century, such charges had spread south to what is now Italy and as far to the east as Poland and Hungary.

As accusations spread, so did the false belief that Jews routinely engaged in the practice of ritual murder. An accusation made repeatedly tends to be believed, no matter how illogical and false it is. Where there is smoke, people fear, there is fire.

In 1255, a five-year-old boy was found dead in a well in Lincoln, England. Many historians today believe that young Hugh accidentally fell into the well. But in 1255, Christians in Lincoln were absolutely certain that “the Jews” had murdered him and had then thrown his body into the well. Unlike officials in Norwich, those in Lincoln immediately charged an individual, a Jew known as Copin who lived nearby. They tortured him until he “confessed” to ritual murder, and they then arrested all the other Jews in the city.

This time, no king or emperor stepped in to save the Jewish community. Indeed, King Henry III traveled to Lincoln to order Copin’s execution. Henry also imprisoned all of the other Jews in Lincoln in the Tower of London. Sources suggest that as many as 100 Jews were held there and at least 18 were hanged.

Like William of Norwich, young Hugh became a saint, and his story, like William’s, was embellished with each telling. Eventually, one version claimed that the Jews had fattened the boy for ten days with milk and bread before murdering him. The murder itself was said to have mimicked the details of the Passion—a word that refers to the suffering of Jesus before the crucifixion. Hugh’s story was later set to music; scholars have identified more than 21 versions of a ballad about his death. In the late 1300s, decades after the expulsion of the Jews from England, Geoffrey Chaucer, one of England’s earliest poets, included Hugh’s story in his Canterbury Tales. The cathedral in Lincoln contained a shrine to “Little St. Hugh” that was a tourist attraction for 700 years. In 1955, ten years after the Holocaust and in response to it, the plaque was removed. In its place is one with these words:

By the remains of the shrine of “Little St. Hugh”: Trumped up stories of “ritual murders” of Christian boys by Jewish communities were common throughout Europe during the Middle Ages and even much later. These fictions cost many innocent Jews their lives. Lincoln had its own legend and the alleged victim was buried in the Cathedral in the year 1255. Such stories do not redound to the credit of Christendom, and so we pray: Lord, forgive what we have been, amend what we are, and direct what we shall be.

Twenty years before Hugh’s death in 1255, a new element had been added to charges of ritual murder against Jews. They were now accused of murdering Christian children for their blood. This accusation has become known as the “blood libel.” Like other charges of ritual murder, the “blood libel” is a lie that has led to the death of countless Jews over the centuries.

In the thirteenth century, most people in northern Europe believed that blood had enormous power. Christians thought it was a source of strength, because it held the power of the soul. They used animal blood in medicines and in amulets, or charms, to ward off evil. Jews also thought blood had power. Because they thought that blood contained the spirit of living beings, Jews were forbidden to taste blood. Jewish dietary laws require great care in the preparation of meat to avoid the possibility of eating blood (as those who keep kosher are well aware). Animals are slaughtered in such a way that most of the blood is drained rapidly. Whatever blood remains is removed by broiling or soaking and salting the meat. Even today, observant Jews are not permitted to eat so much as an egg that contains a blood spot. Jews who come into contact with blood have to purify themselves before carrying out their religious obligations.

BLOOD LIBELS (1144–1500)

The map shows where in Europe Jews were accused of killing Christians for their blood for a period of approximately 300 years. Compare and contrast this map with the ones in Chapters 4 and 6. The three not only suggest the power of lies but also offer insight into the way lies spread over time and place.

Nevertheless, on Christmas Day in 1235, Jews in the town of Fulda in Germany were accused of murdering five children for their blood. The story begins when a miller and his wife, who lived just outside the town, returned from church to find their mill burned to the ground. The charred bodies of the couple’s five sons lay in the ruins. They and their neighbors immediately accused “the Jews” of the crime. According to Christian chroniclers, “the Jews” had murdered the boys and had then drawn off their blood and placed it in waxed bags. What was the motive for such a horrendous crime? Some accounts give no explanation. Others suggest that “the Jews” needed the blood for medicinal or religious purposes.

Horrified by the “crime,” townspeople placed the children’s bodies in a cart and carried them to the emperor, Frederick II, as evidence of what “the Jews” had done. At a time when few people traveled more than a few miles from home in a lifetime, they walked more than 150 miles to the emperor’s castle. At every stop along the way, they told their story.

Frederick did not know what to think; he had never heard of such a crime. So he sent messengers to other European rulers asking for advice. He also sent for recent converts to Christianity to help him determine the truth. In an edict issued in 1236, Frederick summarized what he had learned from his advisers:

[It is] clear that it was not indicated in the Old Testament or in the New that Jews lust for the drinking of human blood. Rather, precisely the opposite, they guard against the intake of all blood, as we find expressly in the biblical book, which is called [Genesis in English], in the laws given by Moses, and in the Jewish decrees, which are called in Hebrew, “Talmud.” We can surely assume that for those to whom even the blood of permitted animals is forbidden, the desire for human blood cannot exist, as a result of the horror of the matter, the prohibition of nature, and the common bond of the human species in which they also join Christians. Moreover, they would not expose to danger their substance and persons for that which they might have freely when taken from animals. By this sentence of the princes, we pronounce the Jews of the aforesaid place and the rest of the Jews of Germany completely absolved of this imputed crime. Therefore, we decree… that no one, whether cleric or layman, proud or humble, whether under the pretext of preaching or otherwise, judges, lawyers, citizens, or others shall attack the aforesaid Jews individually or as a group a result of the aforesaid charge. Nor shall anyone cause them notoriety or harm in this regard. Let all know that, since a lord is honored through his servants, whosoever shows himself favorable and helpful to… the Jews will surely please us. However, whosoever presumes to contravene the edict of this present confirmation and of our absolution bears the offense of his majesty.4

Despite the emperor’s order, the accusations continued. In March 1247, two Franciscans (members of a monastic order founded in about 1215) accused the Jews of Valréas, in France, of crucifying a Christian child and using his blood for ritual purposes. Several Jews in the town were tortured and many others were killed. The survivors appealed to Pope Innocent IV for help, and he condemned such accusations in strong language. So did his successor, Gregory X. In 1271, Gregory issued the following statement:

Since it happens occasionally that some Christians lose their Christian children, the Jews are accused by their enemies of secretly carrying off and killing these same Christian children and of making sacrifices of the heart and blood of these very children. It happens, too, that the parents of these children or some other Christian enemies of these Jews secretly hide these very children in order that they may be able to injure these Jews, and in order that they may be able to extort from them a certain amount of money by redeeming them from their straits….

And most falsely do these Christians claim that the Jews have secretly and furtively carried away these children and killed them, and that the Jews offer sacrifice from the heart and the blood of these children, since their law in this matter precisely and expressly forbids Jews to sacrifice, eat, or drink the blood, or to eat the flesh of animals having claws. This has been demonstrated many times at our court by Jews converted to the Christian faith: nevertheless very many Jews are often seized and detained unjustly because of this.

We decree, therefore, that Christians need not be obeyed against Jews in a case or situation of this type, and we order that Jews seized under such a silly pretext be freed from imprisonment, and that they shall not be arrested henceforth on such a miserable pretext, unless—which we do not believe—they be caught in the commission of the crime. We decree that no Christian shall stir up anything new against them, but that they should be maintained in that status and position in which they were in the time of our predecessors, from antiquity till now.5

Gregory’s statement suggests some of the reasons the accusations were readily believed. For one thing, life was difficult and dangerous for most people, and children were particularly vulnerable to accidents and illnesses. Grief-stricken parents may have wanted to blame someone for the death of their child, and by accusing “outsiders,” they did not have to believe that God was responsible for their child’s death. In addition, blaming an “outsider” meant that they themselves did not have to take responsibility for events like the fire in Fulda.

At a time when there were no newspapers and few books, and when most people could not read in any case, news arrived by way of travelers’ stories and rumors. The more gruesome the story, the more interested people were (as they are today). And then, as now, rumors were almost always embellished in the retelling. There were generally no voices to be heard on the other side of the story. So, for example, by the time Frederick II issued his edict concerning the fire in Fulda, a year had passed, and the story was firmly embedded in people’s minds.

Gregory mentions Christian enemies of Jews who falsely claimed that their children were dead in order to have Jews arrested and executed or to demand money from them before “finding” the children safe. Perhaps some of these Christians owed money to Jews and could not repay it; this might have seemed like an easy way to erase the debt. Others, influenced by those who preached against the Jews, doubtless believed they were acting as good Christians. For most Christians, the church was the major force in their lives and the only source of instruction and stories. It was also the main source of help in times of need and of medical care for the injured or ill. For such people, anyone who did not share their respect for and love of the church was easily suspected of terrible deeds.

Near the end of the thirteenth century, a new and even stranger accusation appeared—the desecration of the host. In many Christian churches, the central worship was—and is—the celebration of the Eucharist (a word that means “thanksgiving”). As part of the Eucharistic liturgy, unleavened bread and wine are blessed in remembrance of Jesus’s words and actions at the Last Supper. According to the New Testament, at this Passover meal, Jesus blessed unleavened bread and wine and gave them to his disciples, saying, “This is my body…. This is my blood. Do this in remembrance of me.” While there are different interpretations of what he might have meant by those words, many Christians believe they mean that Christ is truly present in the bread (the “host”) and wine.

In the thirteenth century, however, a number of Christians came to believe that the host had magical powers. By 1290, some of these Christians were accusing Jews of desecrating the host. The rumor began in Paris. People whispered that a Jew had acquired a consecrated host (by theft or as security for a loan) in order to determine whether it had magical power. According to one version of the story, he stabbed it with a knife and then threw it into boiling water. The water immediately turned red with blood. According to rumors, after witnessing this miracle, the man and his family converted to Christianity.

The story spread from city to city and was widely believed. The pope even ordered a chapel built at the spot where the Parisian Jew had supposedly desecrated the host. It became a popular pilgrimage site. Despite the excitement, no one in Paris rioted or attacked Jews because of this story, perhaps because the story ended with the Jew’s conversion. In other cities, however, particularly in what is now Germany, a charge of desecration was usually followed by riots in which many Jews were killed.

With each new rumor, each new accusation, the way Christians thought about Jews became more and more distorted. Jews were increasingly seen as a powerful threat to Christianity, mainly because until the tenth century, Judaism was a faith that encouraged outsiders to convert. Even after Jews abandoned the practice of proselytizing, some Christians became Jews. The fear that many more Christians would do so was reflected in church laws.

For centuries, the church had declared that Jews were entitled to protection of their property and their person. They could not be forced to convert to Christianity, and their religious rituals were protected. These rights were balanced by limitations on what the church defined as “harmful” Jewish behavior. For example, Jews had to be in an inferior position in relation to Christians; therefore, they could not own Christian slaves or hold political positions that gave them authority over Christians. The fear was that if Jews had power, they would use it to lure Christians away from their faith.

Those concerns can be seen in a bull issued in 1120 by Pope Calixtus II. (A bull is a formal proclamation issued by a pope. The word comes from the Latin bulla, or seal, that popes placed on legal documents.) The bull issued by Calixtus was addressed “to all the Christian Faithful.” In it he declared that even though Jews remained “obstinately insistent” on keeping their beliefs, he was willing to protect their ancient rights, including the right to practice their faith, as long as they were “not guilty of plotting to subvert the Christian faith.” Thus the pope maintained that his protection of Jews and their rights was conditional—that is, he would guard their rights provided that they did not challenge Christianity in any way.

Other popes issued similar statements. In 1205, for example, Innocent III stated that “Christian piety permits the Jews to dwell in the Christian midst.” Yet he too warned that “Jews ought not be ungrateful to us, [repaying] Christian favor with [abuse] and intimacy with contempt.”

In 1215, Innocent called together 400 bishops and hundreds of other religious and political leaders for the Fourth Lateran Council, an assembly that met in the Lateran Palace in Rome. The council issued 70 edicts in an effort to unite Christians and stamp out heresies, which were considered threats to the church. Five of the 70 edicts affected Jews or former Jews. Two addressed the cost of the loans Jews made to Christians. Charging interest for a loan was considered usury, a sin in the church. Another edict repeated a law that had been in effect for several hundred years: Jews were not to hold public office, “since this offers them a pretext to vent their wrath against Christians.” Yet another edict dealt with Jews who converted to Christianity: church leaders were to keep those Jews from returning to Judaism. The final edict stated:

In some provinces a difference in dress distinguishes the Jews or Saracens [Muslims] from the Christians, but in certain others such a confusion has grown up that they cannot be distinguished by any difference. Thus it happens at times that through error Christians have relations with the women of Jews or [Muslims], and Jews and [Muslims] with Christian women. Therefore, that they may not, under pretext of error of this sort, excuse themselves in the future for the excesses of such prohibited intercourse, we decree that such Jews and [Muslims] of both sexes in every Christian province and at all times shall be marked off in the eyes of the public from other peoples through the character of their dress…. Moreover, during the last three days before Easter and especially on Good Friday, [Jews] shall not go forth in public at all, for the reason that some of them on these very days, as we hear, do not blush to go forth better dressed and are not afraid to mock the Christians who maintain the memory of the most holy Passion by wearing signs of mourning.

This, however, we forbid most severely, that any one should presume at all to break forth in insult to the Redeemer. And since we ought not to ignore any insult to Him who blotted out our disgraceful deeds, we command that such impudent fellows be checked by the secular princes by imposing [on] them proper punishment so that they shall not at all presume to blaspheme Him who was crucified for us.6

The first paragraph of the edict is similar to ones found in Muslim countries, because Christian authorities, like their Muslim counterparts, were concerned about “honest mistakes” in identifying the “other.” And as in Muslim countries, the edict concerning clothing was not always enforced. A number of Jews quietly resisted the order, and a number of rulers quietly ignored their failure to obey. These rulers regarded Jews as their own subjects, and they did not want the pope to tell them how their subjects were to be treated. A few rulers pointed out that the requirement that all Jews wear a badge contradicted earlier bulls, which had said no change could be made in the customs of Jews.

Still, by the end of the thirteenth century, most European Jews were forced to wear badges or distinguishing clothing. The aim was to humiliate Jews by setting them apart from their neighbors. The effect was twofold: the image of Jews as a threat to Christians was reinforced, and as Jews became easier to identify, they were more vulnerable to attacks.

An even greater infringement on the traditional rights of Jews also had its start in the thirteenth century. The church began to attack the Talmud—the massive collection of Jewish laws and traditions compiled from about 200 to 600 CE. The first to denounce the Talmud was a former Jew named Nicholas Donin. Even before he converted to Christianity, he had rejected the Talmud as contrary to what he considered authentic Judaism—the Judaism of the Bible. The rabbis in La Rochelle, the French port city where he lived, excommunicated him for those beliefs in 1225. He then converted to Christianity and became a Franciscan friar.

A Jewish couple from Worms, a German city. The man has a badge sewn on his upper garment. Jews who failed to wear a badge were fined. In some places, all Jews also had to pay a special tax for the “right” to wear the badge.

In 1236, Donin presented Pope Gregory IX with a list of 35 charges against the Talmud and rabbinic Judaism—the form of Judaism practiced by most Jews since the first century of the Common Era. Donin told the pope that the Talmud was a work of heresy, as it contained lies and statements critical of Christians and Christianity. We do not know why Donin saw the Talmud as a threat to Christianity. Nor do we know why he thought the pope would care that Jews did not practice their faith in exactly the way their ancestors had.

What is known is that the pope waited three years to respond to Donin’s charges. In June 1239, he sent Donin to the bishop of Paris with a copy of the charges and a request that the bishop pass them on to religious and political leaders in other parts of France. The letter contained an order to seize “all the books of Jews” in the leader’s district on the first Saturday of Lent at a time when Jews gathered in their synagogues for prayer. A few weeks later, Gregory issued a second letter to the bishop of Paris directing that the books he had seized be burned.

King Louis IX of France decided to delay the book burnings. He first wanted to place the Talmud on trial. He asked Donin to serve as prosecutor and ordered the leading rabbi of Paris to answer Donin’s charges. Another, more formal trial followed this public debate. The outcome was clear before either event took place: the Talmud was found “guilty,” and the books were burned.

In June 1242, more than 24 wagonloads of books—about 10,000 volumes, each painstakingly created by hand—were destroyed in a public square in Paris. The fire burned for a day and a half. The book burning marked the beginning of a campaign against rabbinic Judaism, a campaign that was part of a larger war against heresies of all kinds. Jews tried desperately to persuade a new pope, Celestine IV, to change the ruling. Although he was willing, it was too late. The damage was done. In the years that followed, the Talmud would become the symbol of everything Christians feared about Jews and tried to suppress.

As a result of the “blood libel” and other lies, Christians in Europe in the thirteenth century and beyond increasingly saw Jews as a depraved and evil people. In many countries, Jews were now required to live apart from their neighbors and wear distinctive badges or clothes that alerted strangers to the “dangers” they posed. In times of war, plague, and other crises, those lies were used to blame “the Jews” for every misfortune.