(1914–1920s)

Between 1903 and 1905, more than 3,000 antisemitic pamphlets, books, and articles were published in Russia alone. One of those works was The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, which supposedly contained the minutes of a secret meeting of Jewish leaders—the so-called “Elders of Zion.” At that meeting, according to the Protocols, the “Elders” plotted to take over the world.

In 1905, few people had paid much attention to the document, but after World War I, it became a worldwide sensation. Many believed that it explained seemingly “unexplainable” events—wars, economic crises, revolutions, epidemics. The idea of a Jewish conspiracy had been around for centuries, but the Protocols gave that belief new life, and it remained rooted in popular culture long after it was exposed as a hoax in the early 1920s. For many people, World War I and the earthshaking events that followed it confirmed the authenticity of the document, no matter what evidence was offered to the contrary.

World War I was sparked not by a Jewish conspiracy but by an assassination in Sarajevo, the capital of Bosnia. On June 28, 1914, a Bosnian Serb who belonged to an extreme nationalist group killed Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the heir to the throne of Austria-Hungary, an empire that controlled much of central Europe. Just two months later, the world was engulfed in a war that lasted four years, was fought on three continents, and ultimately involved 30 nations. On one side were the Central Powers—Austria-Hungary, Germany, and the Ottoman Empire, and the countries that supported them. On the other side were the Allies—Serbia, Russia, France, and Britain, and the countries that supported them. More than 19 million people were killed during the fighting; about half of them were civilians.

Winston Churchill, who later became prime minister of Britain, described the terrible nature of this “world war”:

All the horrors of all the ages were brought together, and not only armies but whole populations were thrust into the midst of them. The mighty educated States involved conceived—not without reason—that their very existence was at stake. Neither peoples nor rulers drew the line at any deed which they thought could help them win…. Every outrage against humanity or international law was repaid by reprisals—often of a greater scale and of longer duration. No truce or parley mitigated the strife of the armies. The wounded died between the lines: the dead moldered into the soil. Merchant ships and neutral ships and hospital ships were sunk on the seas and all on board left to their fate, or killed as they swam. Every effort was made to starve whole nations into submission without regard to age or sex.1

EUROPE AT WAR (1914–1918)

The areas of heavy fighting during World War I in Europe, particularly in the east, were areas where most Jews lived. Many were caught in the crossfire.

Approximately 400,000 Jews served in the armies of the Central Powers, including 300,000 who fought for Austria-Hungary. Among these fighting for the Allies were 300,000 Jews in the Russian military and 4,000–5,000 in the American armed forces.

When people are engaged in such a war, their search for enemies focuses not only on the foreign armies outside their country’s borders but also on enemies—real and imagined—within those borders. During World War I, a number of rulers, generals, and ordinary citizens accused vulnerable minorities in their own countries of treason and disloyalty. In the Ottoman Empire, Christian Armenians were the primary victims. In much of eastern Europe—particularly Russia—Jews were the target. They were seen as disloyal, even though more than 300,000 Jews fought, often with distinction, in the Russian army. In fact, Jews fought in every army involved in the conflict; for example, 100,000 served in the German army.

Accusations of disloyalty have consequences, particularly in a war zone, and according to the American Jewish Committee, “one-half of the Jewish population of the world was trapped in a corner of eastern Europe that is absolutely shut off from all neutral lands and from the sea.”2 The American Jewish Committee had been founded in 1906 by American Jews who wanted to protect Jews in Russia from the pogroms (see Chapter 11). Now, ten years later, they feared for the safety of Jews throughout eastern and central Europe.

The war in Europe was being fought on two fronts, or lines of battle. On the western front, which stretched from Belgium to Switzerland, the two sides were mired in trench warfare, each determined to exhaust the other. Neither was strong enough to win a decisive victory. On the eastern front, however, large stretches of land shifted back and forth from one side to the other.

Early in the war, the Russians won control of much of the Austrian province of Galicia and then bombarded the German state of East Prussia. But as the war progressed, the Germans prevailed. In a battle fought near the city of Tannenberg in August 1914, Germans nearly destroyed the Russian army. To exploit their victory, the Germans went on the offensive. Within two months, they controlled the northwestern part of Russian Poland and parts of Lithuania and the Ukraine. As the Russians retreated, they set fire to homes, farms, and businesses. Millions of people—Jews and Christians alike—were left homeless.

In the eyes of the Russian government, not all of those homeless civilians were loyal. During the war, a Jewish playwright and journalist who called himself S. Ansky traveled through the small towns, or shtetels, that dotted the Pale of Settlement and Russian-controlled Galicia to organize aid to Jewish communities there and investigate accusations that Jews were spying for the Germans. He summarized his findings:

At first, the slanderers did their work quietly and furtively. But soon they took off their masks and accused the Jews openly….

From the generals down to the lowest ensign, the officers knew how the czar, his family, the general staff, and [the commanders] felt about Jews; and so they worked to outdo one another in their antisemitism. The conscripts were less negative but hearing the venom of their superiors and reading about Jewish treason day after day they too came to suspect and hate Jews….

Every commander and every colonel who made a mistake had found a way to justify his crime, his incompetence, his carelessness. He could make everything kosher by blaming his failures on a Jewish spy. The officers, who accepted lies against Jews without question or investigation, were quick to settle accounts with the accused….

The persecution reached mammoth proportions…. When the Russian army passed through many towns and villages, especially when there were Cossacks [members of the army’s elite cavalry], bloody pogroms took place. The soldiers torched and demolished whole neighborhoods, looted the Jewish homes and shops, killed dozens of people for no reason, took revenge on the rest, inflicted the worst humiliation on them, raped women, injured children…. A Russian officer talked about seeing Cossacks “playing” with a Jewish two-year-old: one of them tossed the child aloft, and the others caught him on their swords. After that, it was easy to believe the German newspapers when they wrote that the Cossacks hacked off people’s arms and legs and buried victims alive….

On the assumption that every Jew was a spy, [the Russian government] began by expelling Jews from the towns closest to the front: at first it was just individuals, then whole communities. In many places Jews and ethnic Germans were deported together. This process spread farther and farther with each passing day. Ultimately all the Jews—a total of over two hundred thousand—were deported from Kovno and Grodno provinces.3

At a meeting in St. Petersburg, N. B. Shcherbatov, the Russian minister of the interior, confirmed the charges made by Ansky and other Jews. He told fellow officials that even though “one does not like to say this,” military officers were attributing to Jews “imaginary actions of sabotage against the Russian forces” so that they could hold the Jews “responsible for [the army’s] own failure and defeat at the front.”4 Another official noted that the Jews “are being chased out of the [eastern front] with whips and accused… of helping the enemy”—with no attempt to distinguish the guilty from the innocent. He feared that when these refugees arrived in new areas, they would be in a “revolutionary mood.”5

By late summer of 1915, the Russian army had uprooted more than 600,000 Jews. A non-Jewish deputy in Russia’s parliament described their removal from the province of Radom:

The entire population was driven out within a few hours during the night…. Old men, invalids and paralytics had to be carried in people’s arms because there were no vehicles. The police… treated the Jewish refugees precisely like criminals. At one station, for instance, the Jewish Commission of Homel was not even allowed to approach the trains to render aid to the refugees or to give them food and water. In one case, a train which was conveying the victims was completely sealed and when finally opened most of the inmates were found half-dead, sixteen down with scarlet fever and one with typhus.6

Thousands of Jewish families were displaced during World War I. Some were forced out by the fighting, but many more were expelled from their homes because the Russians saw them as potential traitors.

Soldiers who “catch” toddlers on their swords and police officers who force “old men, invalids, and paralytics” from their homes are not protecting their country from treason. Rather, they are seeing Jews as stereotypes, not as human beings. A stereotype is more than a label or judgment about an individual based on the real or imagined characteristics of a group. Stereotypes dehumanize people by reducing them to categories; in this case, officials treated babies and paralytics as traitors despite all evidence and logic.

Similar stereotypes shaped the irrational decisions of the tsar, his ministers, and top generals. For example, by 1916, Russian soldiers experienced shortages of food, fuel, ammunition, and other necessities, partly because the government was using freight trains and supply wagons to remove thousands of Jewish civilians from cities and towns in western Russia and resettle them farther east.

Although the Council of Ministers expressed no regret for the expulsions or the pogroms, its members did worry about their impact on Russia’s ability to borrow money abroad. The stereotype of the “rich Jewish banker” encouraged the ministers to exaggerate Jewish wealth and influence. In 1915, Jacob Schiff, a German-Jewish American banker, had refused to help the Allies secure a large loan if even “one cent of the proceeds” went to the Russian government. Russian officials saw his action as proof of a “Jewish plot” to overthrow the tsar. But, despite the power attributed to Schiff, the Allies easily found other bankers willing to lend them the money they needed. Although some of those bankers were Jews, the vast majority of them were Christians.

The Russian ministers who saw evidence everywhere of an “international Jewish conspiracy” were not alone. A number of British, French, German, Austrian, and other European officials also routinely exaggerated the power of Jews—particularly American Jews.

Throughout 1915 and 1916, the United States did not take sides in the war, despite the efforts of the Allies and the Central Powers to win the nation’s support. Both believed that American Jews could tip the decision to one side or the other. Why were they so convinced that about three million Jews (most of whom were penniless immigrants) in a nation that was home to more than 88 million people had so much power?7 That belief was based in part on the old myth that Jews controlled the world’s wealth. It was also influenced by the vigor with which Jews defended one another. Every time a group of Jews protested an injustice or helped a poverty-stricken Jewish community at home or abroad, some non-Jews saw those efforts as evidence of an international conspiracy and concluded that Jews were loyal only to one another and not to the countries they lived in.

David Lloyd George, who became Britain’s prime minister in 1916, was among those who believed that “the Jews” had enormous power. He was also convinced that 1917 would be the critical year in the war and that the Allies must make a tremendous effort to ensure their victory—especially after Russia was rocked by a revolution in the spring. He later wrote that he had faced two major problems that year: how to convince the new government in Russia to continue fighting the war and how to persuade the Americans to join the Allies. “In the solution of these two problems,” he noted, “public opinion in Russia and America played a great part, and we [believed]… that in both countries the friendliness or hostility of the Jewish race might make a considerable difference.”8

The Ottoman Empire, which controlled Palestine and other parts of the Middle East, was an ally of Germany and Austria-Hungary. Early in the war, the Ottoman governor of Palestine had feared that Arab and Jewish nationalists there would side with the Allies. So he arrested some of them and banished about 6,000 of the 85,000 Jewish settlers in the province. Many of them found refuge in British-controlled Egypt.

Almost everyone the governor deported was a Russian Jew. In his view, all Russian Jews were enemy aliens, even though many of them considered themselves refugees from Russian persecution. He ordered their newspapers, schools, banks, and political offices closed. When David Ben-Gurion and other Zionist leaders protested, they too were exiled.

That policy persuaded some Zionists and Arab nationalists to help the Allies. In 1916, the British offered to aid the Hashemites, a powerful Arab family, in creating an independent Arab kingdom in exchange for their military support for the Allies. Zionists were interested in a similar arrangement. They wanted the British to recognize the rights of the Jewish people in Palestine. To show their commitment to the Allies, a group of young Jews organized a Jewish legion that fought on behalf of the British. About one-third were from Palestine (including many Russian Jews, some of whom had been expelled by the Ottomans earlier in the war); another third came from the United States. The rest were from various countries, including Britain, Canada, and Argentina.9

On November 2, 1917, Arthur James Balfour, the British foreign secretary, issued a declaration that stated, in part: “His Majesty’s Government view with favor the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavors to facilitate the achievement of this object.” To many antisemites, the Balfour Declaration, as it became known, was “proof” that “the Jews” controlled Britain. To Lloyd George, Balfour, and other government leaders, it was a rational decision that, they believed, would result in strong support for the Allies.

In nations that were already committed to the Allies’ cause, most Jews celebrated the announcement. But some were wary; they thought the declaration suggested that Jews were more loyal to other Jews than to the countries they lived in. And it did not change the way most German and Austrian Jews viewed the war—they remained loyal to their countries.

The Central Powers shared the British government’s view of Jews as a “united race,” and therefore they saw the Balfour Declaration as a powerful piece of propaganda for the Allies; they believed it would prompt Jewish bankers to lend more money to the Allies. To minimize the effects of the declaration, Ottoman officials ended restrictions on Jewish immigration to Palestine. And in January 1918, when the Germans approved their own plan to create an autonomous Jewish settlement in Palestine, the Ottomans reluctantly agreed.

Although the Balfour Declaration would have important long-term effects, it had no impact on the two problems that British Prime Minister Lloyd George struggled with in 1917. As he had hoped, the United States did declare war in April 1917—but the decision could not be attributed to Jewish influence because it occurred about seven months before the Balfour Declaration was issued. In addition, by November 1917, a second revolution was under way in Russia. Not only had the tsar been overthrown but now Russia’s first democratic government had been replaced as well. Russia’s newest government, led by a Communist group known as the Bolsheviks, officially withdrew from the war and signed a peace treaty with the Germans. In spite of Lloyd George’s hopes, Jewish public opinion had no effect on that decision, either.

Thanks to that treaty, Germany was able to transfer thousands of soldiers from the eastern front to battlefields in the west. There they faced a new opponent, the United States. By June 1918, American troops were arriving in France at the rate of 250,000 a month. By fall, the Americans were helping the Allies push the Germans back. On November 1, they crashed through the center of the German line. It was then only a matter of days until Germany surrendered and the war was finally over.

As World War I was coming to an end, Jewish civilians in eastern Europe found that the dangers they faced were intensifying rather than diminishing. Three of the great empires that had controlled eastern and central Europe and western Asia had begun to break apart during the war. Russia, Austria-Hungary, and the Ottoman Empire were each home to dozens of ethnic groups who were determined to take advantage of the collapse. As these groups jockeyed for power and independence, revolutions and civil wars broke out almost everywhere. And almost everywhere, Jews were caught in the middle.

Soon after the Bolsheviks gained control in Russia in 1917, they gave the country both a new name—the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR, or the Soviet Union)—and a Communist government based on the ideas of Karl Marx, a German philosopher who lived from 1818 to 1883. Marx believed that the struggle between workers and manufacturers and other industrialists would end only when workers owned all land and other resources not as individuals but as a community. In his view, only then would everyone be equal.

Because of his belief in communal, or shared, ownership of land and other resources, the system Marx envisioned became known as Communism. It was a radical form of socialism based on the idea of taking from each person according to his or her ability and giving to each according to his or her needs. This meant that a communist government “took” work and other contributions from its citizens and “gave” them support based on their needs rather than on their status in society, efforts, education, or talent. Marx also advocated a dictatorship of the proletariat (the workers), or rule by the majority class in society. Such rule would be a step toward a new classless society.

V. I. Lenin, the leader of the Bolsheviks, agreed with most of Marx’s ideas, but he quickly realized that the real world did not always match Marx’s theories. Almost as soon as the Communists took power, they found themselves at war with the White Army, which was made up mainly of Russians who hoped to restore the deposed tsar to power. The White Army had the support of Britain and the Allies, now that the Bolshevik government in Russia had made its own peace agreement with Germany. The Bolsheviks also faced opposition from nationalist groups who wanted their own independent countries and from bands of outlaws who simply saw an opportunity to acquire wealth and power amid the confusion. As a result, in some parts of the old Russian Empire, no one was in control.

The situation was particularly treacherous in the Ukraine. Like other ethnic groups in the old Russian Empire, Ukrainians wanted independence. As a result, the Bolsheviks’ Red Army there faced not only the White Army, but also gangs of bandits and thugs, and a newly organized Ukrainian national army. With the exception of the Communists, these armies all targeted Jews, in the belief that in doing so they were attacking Bolsheviks. To them, all Jews were Communists and all Communists were Jews.

In fact, most Jews were not Communists, although some Jews did belong to the Communist Party and a few held high positions in the party. Many Russians believed Jews were all Communists because Karl Marx was of Jewish descent. Perhaps the best known Jew in the Russian Communist party was Leon Trotsky, who organized and led the Red Army. Like Marx and other Communists, he had no interest in Judaism or any other religion, and he rejected any connection to Jews as a people. Nevertheless, non-Jews in Russia viewed him and other Communists of Jewish descent as Jews and increasingly regarded Communism as a Jewish creation, even though the vast majority of Communists were non-Jews.

About 60 pogroms against Jews took place in the Ukraine in November and December 1917, and attacks continued off and on for another two years. One of the most horrific took place in February 1919 in the town of Proskurov, about 175 miles south of Kiev. At the time, the town was ruled by an independent Ukrainian government known as the Directory. Early on the morning of February 15, local Communists, including a number of Ukrainians and Jews, tried to regain control of the city by attacking a rail yard where Directory soldiers were encamped. The Ukrainian officer in charge was a man known only as Semosenko. Within a few hours, he and his men had put down the uprising and killed those responsible.

Later that day, Semosenko, who apparently believed that all Jews were Communists, decided to take revenge for the attack by slaughtering all the Jews in the town. He warned his officers that their men were not to loot or steal; they were simply to kill every Jew in Proskurov. He explained that the attack was a matter of honor.

One Ukrainian officer refused to participate in the massacre; he would not allow his men to kill unarmed civilians. The officer and the soldiers under his command were promptly sent out of town. Everyone else obeyed. The men marched through the center of town in battle formation, with the band in front. They then “dispersed into the side streets which were all inhabited by Jews only.”10

It was the Sabbath, and most Jews knew nothing about the early-morning uprising against the Directory or its outcome. They went to synagogue as usual and then returned home for their Sabbath meal. They learned of the attack only when soldiers burst into their houses, unsheathed swords, and “calmly proceeded to massacre the inhabitants without regard to age or sex. They killed alike old men, women, children, and even infants in arms.”11

Among the dead was a local Catholic priest who begged the soldiers to stop. He was killed at the door to his own church. A town councilor begged Semosenko to stop the killing but was ignored. So the councilor sent a telegraph to Semosenko’s commander, who immediately ordered an end to the massacre. Only then did the slaughter stop. As soon as the soldiers heard a prearranged signal, “they fell in at the place previously appointed, and, in orderly ranks, as on a campaign, singing regimental songs, marched to their camp behind the [train] station.”12 In three hours, they had killed 1,200 infants, children, women, and men.

Before leaving town, Semosenko issued a proclamation blaming the Jews for the massacre and warning that he would return if they dared to cause trouble again. He and his troops then headed for a nearby town, where they carried out yet another pogrom.

Despite atrocities like this one, Ukrainian officials insisted that they were not hostile to Jews. But their words did not keep Ukrainian nationalist troops from continuing to target Jews. When a survivor of one massacre protested that neither he nor his neighbors were Communists, he was told, “We aren’t after Communists; we are after Jews.”13 Once again, neither truth nor logic was a match for deep-seated beliefs.

The White Army also participated in pogroms in the territories under its control, and, by late summer of 1919, these forces had taken the lead in attacking Jews. John Ernest Hodgson, a British journalist who traveled with White Army troops, explained why:

The officers and the men of the army laid practically all the blame for their country’s troubles on the Hebrew. They held that the whole [catastrophe] had been engineered by some great and mysterious secret society of international Jews who, in the pay and at the orders of Germany, had seized the psychological moment and snatched the reins of government.14

Those ideas (except for the part about the secret society being in the pay of Germany) came straight from The Protocols of the Elders of Zion. The Protocols had disappeared from view during the world war, but the brutal murder of Tsar Nicholas II, his wife Alexandra, and their five children at the hands of the Bolsheviks in July 1918 had turned new attention to the document. A week after the killing, White Army soldiers found a copy of the Protocols among Alexandra’s possessions. They also discovered that she had drawn a swastika on one wall. For the tsar’s supporters, the two discoveries had great meaning.

Historians have found letters suggesting that Alexandra’s copy of the Protocols was probably not a treasured possession but rather a gift she received just before she was taken into custody. Her letters also indicate that she regarded the swastika as a good luck symbol, as many people did at the time. The symbol, which is at least 3,000 years old, had been used in countries around the world to signify life, power, strength, or good fortune. But in the early 1900s, the symbol had begun to take on a new meaning in Germany. Some Germans now regarded it as a sign of the purity of “Germanic blood” and the struggle of “the Aryans” against “the Jews.” That view of the swastika, as a symbol of a fight against “the Jews,” was also popular among some of the tsar’s supporters. They now imagined that the book and the swastika were signs from the tsarina that the White Army was engaged in an epic battle against the evil Red Army, controlled by “the Jews.”

The news that the tsarina had owned a copy of the Protocols spread quickly through the army. Before long, many officers and ordinary soldiers were convinced that the fact that she had carried the book with her was proof that it was true. However, as early 1905, the tsar, and possibly the tsarina, knew that the Protocols was a hoax. Not long after the tsar first read the document, he had been told that it was a forgery created by his own secret police. He immediately halted plans for mass distribution. “One cannot defend a pure cause,” he wrote, “by dirty methods.”15 But despite his stand, the Protocols had remained in print and spread throughout the Russian Empire.

Did the leaders of the White Army know the work was a forgery? Some clearly did. They had held high positions in the secret police and in the tsar’s army. But most of the men who served in the White Army probably believed it was true because it seemed to provide an explanation for the terrible things that had happened to Russia over the past ten years. Hodgson writes that among the White Russians, the idea of a Jewish world conspiracy became “an obsession of such terrible bitterness and insistency as to lead them into making statements of the most wild and fantastic character.”16

Statistics reveal that as a result of that “fierce and unreasoning hatred,” more than 2,000 pogroms took place in eastern Europe between 1917 and 1921. About 75,000 Jews were killed, many more were injured, and at least half a million were left homeless.

During World War I, Jews throughout the world had tried to help their fellow Jews in Europe. After the war, their aid continued and even expanded. Jewish organizations set up soup kitchens, created clinics, and built orphanages in Poland, Hungary, and other eastern and central European countries. They also gathered information about attacks on Jews, particularly in Poland and other newly independent nations in the region. Many were eager to find a way to protect Jews from further violence.

As the war ended in November 1918, Louis Marshall, a prominent American lawyer and a founder of the American Jewish Committee, sent a series of memos to U.S. President Woodrow Wilson. He argued that the Allies should require newly formed nations in the region to accept a treaty guaranteeing the rights of all minorities in exchange for international recognition. It was not a new idea. In 1878, Jews in the West had tried to protect Romanian Jews with a similar treaty at the Congress of Berlin (see Chapter 10). The Romanian government signed the pact but refused to enforce key provisions, and the major powers were unwilling to require it to do so.

In 1878, the major powers had not been fully convinced of the need to protect minorities. After the war, however, they had a better understanding of why it was essential to do so. In 1919, even as world leaders gathered in Paris to write the treaties that would officially end the war, much of eastern Europe was still engulfed in violence. That violence exposed the dangers that Jews and other minorities faced in a region where every newly independent nation had sizeable minority populations. If those populations were not guaranteed political and social equality, the fighting was almost certain to continue.

In a speech to Congress in January 1918, President Wilson had listed 14 points he considered essential to a lasting peace. Many of them dealt with the “frustrated nationalism” that he believed had been responsible for the world war. Therefore he supported the division of the old multinational empires into independent nations. In Wilson’s view, his 14th point was the most important. It called for a league of nations to keep the peace and guarantee the independence of “great and small States alike.” In a speech delivered to a joint session of Congress on January 8, 1918, Wilson claimed that all 14 points were based on a single principle:

It is the principle of justice to all peoples and nationalities, and their right to live on equal terms of liberty and safety with one another, whether they be strong or weak. Unless this principle be made its foundation, no part of the structure of international justice can stand.

In 1919, almost every minority group in Europe, including many Jewish groups, understood the importance of that principle, which is why each sent a delegation to the peace conference in Paris. They demanded not only civil rights but also “self-determination”—the right to maintain their own languages and to govern themselves.

Some Jews in the West were troubled by the calls for self-determination. They believed that demands for “national rights” could backfire. Henry Morgenthau, a Jew who had served as the U.S. ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, shared that view. He argued:

under this plan, a Jew in Poland or Romania, for example, would soon face conflicting duties, and… any American who advocated such a conflict of allegiance for the Jews of central Europe would perhaps expose the Jews in America to the suspicion of harbouring a similar desire.17

Joseph Tenenbaum, a Jew who grew up in Poland, disagreed:

“Why does not America grant the Jews minority rights?” was the common question raised by most of the peace envoys. The answer was: Because America, the great melting pot, does not preach nationalism. There is no such thing as group rights in America, because fundamentally there is no such thing as national group domination.18

Such arguments convinced Louis Marshall. He insisted:

[W]e must be careful not to permit ourselves to judge what is most desirable for the people who live in Eastern Europe by the standards which prevail on Fifth Avenue [in New York City] or in the States of Maine or Ohio, where a different horizon from that which prevails in Poland, Galicia, Ukraine, or Lithuania bounds one’s vision.19

That argument led to the Minorities Treaty, which granted civil, religious, and political rights to all citizens of a state. The word citizen now applied to anyone who was born or “habitually” lived in that state. The treaty also guaranteed every minority group the right to freely use its own language in trade, in court, and in primary schools in places where that group had a sizeable population. In addition, taxes and other public funds were to be used to support not only the schools, religious institutions, and charities of the majority but also those of minorities. To receive international recognition, a new state had to sign the Minorities Treaty and include the rights it guaranteed in its national constitution. The new League of Nations would be responsible for enforcing those treaties.

Most newly independent states objected to the treaty, arguing that it infringed on their right to govern without outside interference. On May 31, 1919, delegations from Poland, Romania, Hungary, Serbia, and Greece protested the treaty at the peace conference. Austria, Bulgaria, and Turkey also voiced objections. The Allies stood firm, however, and one new nation after another signed a version of the treaty. In the end, though, they did not enforce it for long—and the League of Nations lacked the power to force them to do so.

The only new nation that did not protest the Minorities Treaty was Czechoslovakia. Although many Czechs resented the document, their president, Thomas Masaryk, vigorously defended it. When asked why, he replied, “How can the suppressed nations deny the Jews that which they demand for themselves?”

Although the Allies established new states in eastern and central Europe, they did not even consider doing the same in other parts of the world. Much of Asia and Africa remained under European rule. The British and the French divided up the old Ottoman Empire, ignoring the promises they had made to Arab nationalists and Zionists during the war. The British now controlled Palestine and Iraq, and the French ruled Syria and Lebanon. The Zionists did make one important gain: the text of the Balfour Declaration was included in the mandate that the League of Nations gave to Britain in Palestine, over Arab objections. The league defined a mandate as a territory held in trust by a European nation until that nation gave the territory its independence.

The new Soviet Union was one of the few nations that did not attend the peace conference. It had made peace with Germany before the war’s end. Moreover, Russia’s former allies now regarded it as an outlaw state. Many people feared that the Bolsheviks were exporting Communism. Some allies actively supported the White Russians in their efforts to stop Communism. In the end, however, the White Russians were defeated. By 1920, the civil war was largely over, and the Communists had won.

As White Russians fled the Soviet Union, they brought the Protocols of the Elders of Zion with them. To many of them and to a growing number of people in other countries, the Protocols seemed to explain the losses and anxieties of the modern world.

In 1920, Eyre & Spottiswood, a respected British publisher, produced the first English edition of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion. Many people in Britain were intrigued by the document. The editors of the Times of London asked:

Despite the exposé published by the Times of London, The Protocols of the Elders of Zion was a publishing sensation in the 1920s and 1930s. The book could be found in countries around the world, including Japan, Mexico, and Syria.

What are these “Protocols”? Are they authentic? If so, what malevolent assembly concocted these plans, and gloated over their exposition? Are they a forgery? If so, whence comes the uncanny note of prophecy, prophecy in parts fulfilled, in parts far gone in the way of fulfillment?20

In August 1921, the Times answered those questions by exposing the Protocols as a fraud. The newspaper showed how the original author of the document had copied fictional works to create the Protocols. One of those works was an 1868 novel by Hermann Goedsche, a German antisemite. The novel contains a chapter describing a secret meeting of the “Elders of Zion” at midnight in the oldest Jewish cemetery in Prague. In this chapter, as the men gather to plot the enslavement of non-Jews, two Christians hidden among the tombstones eavesdrop. One of them summarizes how “the Jews” intend to undermine Christian nations.

To concentrate in their hands all the capital of the nations of all lands; to secure possession of all the land, railroads, mines, houses; to be at the head of all organizations, to occupy the highest governmental posts, to paralyze commerce and industry everywhere, to seize the press, to direct legislation, public opinion and national movements—and all for the purpose of subjugating all nations on earth to their power!21

As a result of the exposé by the Times, Eyre & Spottiswood stopped publishing the Protocols, and many newspapers no longer gave it publicity. But neither action hurt its popularity. A group known only as the Britons now published its own edition. The preface claimed that the Times exposé proved nothing:

Of course, Jews say the Protocols are a forgery. But the Great War was no forgery; the fate of Russia is no forgery; and these were predicted by the Learned Elders as long ago as 1901. The Great War was no German war—it was a Jew war. It was plotted by Jews, and was waged by Jewry on the Stock Exchanges of the world. The generals and admirals were all controlled by Jewry.22

By 1922, translations of the Protocols had also appeared in Germany, France, and Poland. The Polish edition appeared at a time when many Poles, including leaders of the Roman Catholic Church in Poland, believed the nation was about to be attacked by the Red Army. Two cardinals, two archbishops, and three bishops—all influenced by the Protocols—sent out a “cry for help” that was read in churches around the world. It said, in part:

The real object of Bolshevism is world-conquest. The race which has the leadership of Bolshevism in its hands, has already in the past subjugated the whole world by means of gold and the banks, and now, driven by the everlasting imperialistic greed which flows in its veins is already aiming at the final subjugation of the nations under the yoke of its rule.23

In fact, the Bolsheviks were not plotting “world conquest,” but a revolution. Their leaders were not Jews. Jews did not control Russia’s Communist government or the world’s banks.

Translations also appeared in Denmark, Finland, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Romania, Spain, and a number of South American countries. White Russian exiles in Siberia carried the document to Japan, where it was published in 1924. The patriarch of Jerusalem (the head of the Eastern Orthodox Church in Palestine) urged his followers to buy the Arabic translation in 1925. And almost everywhere, the false statements contained in the book had seeped into the general culture; exposés of the forgery made little difference. After all, who could deny the wars, the revolutions, and the economic disasters that had taken place in the early 1900s? All had supposedly been prophesied in the Protocols.

In the United States, the strongest supporter of the Protocols was none other than Henry Ford, the manufacturer of the first affordable automobile. In 1919, he began publishing a weekly newspaper called the Dearborn Independent. He gave away copies of the paper to customers and sold subscriptions through his car dealerships.

In 1920, a Russian émigré gave Ford a copy of the Protocols. Like many others, Ford never doubted its authenticity. He immediately serialized the Protocols in his newspaper and printed articles that supported its claims. Those articles promised to reveal “The Scope of Jewish Dictatorship in the United States,” “Jewish Degradation of American Baseball,” and “The International Jew—The World’s Foremost Problem.” In 1922, he turned those articles into a book that sold more than a half-million copies.

American Jews tried repeatedly to show Ford that the book was a forgery. When he ignored them, many expressed their disapproval by refusing to buy Ford cars. So did some non-Jews. But few American Jewish leaders supported the boycott. Most thought they had a better chance of persuading Ford to reconsider his views in private meetings. When he refused to see them, they created a public-relations campaign to educate Americans about Jews and Judaism.

That campaign had the support of a number of prominent Catholic and Protestant leaders, who expressed their confidence in the “patriotism and good citizenship” of “our Jewish brethren.” In addition, 119 prominent Americans, including President Woodrow Wilson and former president William Howard Taft, signed a letter in January, 1921 condemning antisemitism. “We believe it should not be left to men and women of the Jewish faith to fight this evil,” the letter said, “but that it is in a very special sense the duty of citizens who are not Jews by ancestry or faith.”24

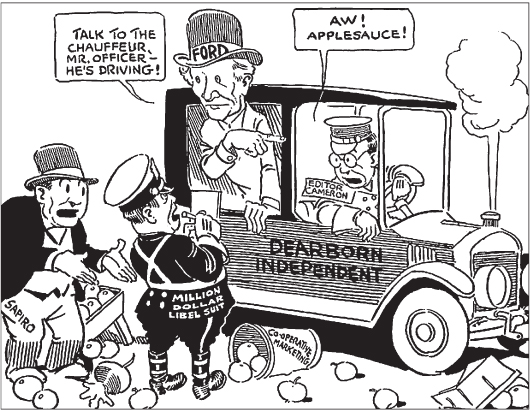

None of these efforts seemed to affect the popularity of the Protocols or Ford’s newspaper. Every week, he received money and letters of appreciation from fans for his “exposé” of Jewish conspiracy. Then, in 1924, the Dearborn Independent ran a series of articles attacking Aaron Sapiro, a Chicago attorney for the National Council of the Farmers’ Cooperative Marketing Association. Ford accused Sapiro of being part of a “conspiracy of Jewish bankers who seek to control the food market of the world.” (According to the Protocols, Jews wanted control of the world’s food supply as a step toward global domination.) Against the advice of family and friends, Sapiro hired a lawyer, who filed a one-million-dollar defamation lawsuit against Ford. (Libel and slander are two forms of defamation. Libel is published defamation, and slander is spoken.) Ford hired a team of lawyers and an army of detectives to defend himself.

Political cartoonists made fun of the tactics Henry Ford used to fight the million-dollar defamation lawsuit that Aaron Sapiro filed against him.

The proceedings ended in a mistrial after a reporter interviewed a juror before the case was decided. As the second trial unfolded, it became increasingly clear that Ford was going to lose the lawsuit, because he had no proof of his charges against Sapiro. At that point, he contacted Louis Marshall and U.S. congressman Nathan Perlman. He told them that he had been wrong to attack Sapiro and other Jews and wanted to make amends. The two men suggested a public apology and an end to Ford’s antisemitic campaign. Ford agreed.

Although some people praised Ford’s change of heart, others were unconvinced. There were five antisemitic organizations in the United States before 1932. Between 1932 and 1940, there were over 120 groups. Many of them relied on the articles and books Ford had published in the 1920s to support their attacks on the Jews.

Among the antisemites who acknowledged their debt to Ford was Father Charles Coughlin, a Detroit-based Catholic priest. At the height of his popularity in the 1930s, his radio show reached more than three million homes across the nation. He also published Social Justice, a magazine with a circulation of about one million. When it reprinted the Protocols, Coughlin wrote, “Yes, the Jews have always claimed that the Protocols were forgeries, but I prefer the words of Henry Ford, who said, ‘The best test of the truth of The Protocols is in the fact that up to the present minute they have been carried out.’” Coughlin added, “Mr. Ford did retract his accusations against the Jews. But neither Mr. Ford nor I retract the statement that many of the events predicted in the Protocols have come to pass.”25

Those “predicted” events included World War I, the Russian Revolution, the Balfour Declaration, and the Minorities Treaty. They were not actually predicted in the Protocols, but the document uses such vague language that it could be interpreted as “proof” of almost any event.

Even before Ford published the Protocols, antisemitism was on the rise in the United States. Some of the antagonism has been linked to the fact that in the early 1900s, about a million immigrants entered the United States each year. Unlike earlier arrivals, most of them were Catholics or Jews from eastern and southern Europe.

Much of the new anti-Jewish feeling was visible but not as conspicuous as the antisemitism in Europe. Nevertheless, American Jews experienced some discrimination almost everywhere they turned. Many colleges, private clubs, and civic organizations limited the number of Jews they would accept, while others excluded all Jews from membership. Employers routinely asked for the “nationality” of job applicants or indicated in their ads that only gentiles (non-Jews) need apply. Even large corporations that were willing to hire Jews for low-level jobs excluded Jews from executive positions or limited their number. Jews were also barred from renting or buying property in some neighborhoods and staying in some hotels. Only rarely did antisemitism become violent. Perhaps the most shocking incident occurred in 1915, during the world war and about five years before the Protocols was published in the United States.

In 1913, Leo Frank, the manager of a pencil factory in Atlanta, Georgia, had been accused of murdering a 13-year-old girl, one of his employees. Even though the prosecution had a weak case, a jury found Frank guilty, as crowds outside the courthouse shouted, “Hang the Jew.” Frank was not allowed in the courtroom when the jury gave its verdict, because the judge feared he would be attacked.

After the judge sentenced Frank to death, his attorneys appealed the conviction, but the higher courts, including the U.S. Supreme Court, voted against reopening the case. Only the governor of Georgia was willing to review the trial records. As a result of that review, he reduced Frank’s sentence to life in prison. A few days later, a mob burst into the prison, kidnapped Frank, and lynched him.

The case shocked Jews throughout the nation. Many had believed that kind of antisemitic violence was impossible in the United States. Five years later, the publication of the Protocols added to their uneasiness. It was a time when vigilante groups like the one that had murdered Frank were being used to keep African Americans, Jews, and Catholics “in their place” not only in the South but also in many northern states. It was also a time when immigration was becoming an increasingly explosive issue, as a story in the New York Times revealed. On August 17, 1920, the newspaper reported:

Leon Kaimaky, [a commissioner of the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society (HIAS) and] publisher of the Jewish Daily News of this city, returned recently from Europe, where he went, together with Jacob Massel, to bring about the reunion of the thousands of Jewish families who were separated by the war. Mr. Kaimaky has been abroad since last February…. In an article in the Jewish Daily News describing conditions in Eastern Europe Mr. Kaimaky declared that “if there were in existence a ship that could hold 3,000,000 human beings, the 3,000,000 Jews of Poland would board it and escape to America.”26

Alarmed readers jumped to the conclusion that the HIAS was planning to bring over three million Polish Jews. So did members of Congress, who immediately called for a ban on all immigration. Albert Johnson, a Republican from Washington State and the chairman of the House Committee on Immigration, brought the matter to a vote without a hearing, and the House quickly passed the ban. By the time the vote was taken, many were fearful that as many as 15 million Jews—the estimated number of Jews in the world in 1920—would soon be arriving in the United States.

The Senate Committee on Immigration was more cautious. Its chairman told reporters, “This talk about 15,000,000 immigrants flooding into the United States is hysteria.” He then called for hearings. The first witness was Johnson, who warned that unless an emergency act was passed, immigrants would “flood this country.”

John L. Bernstein, the president of HIAS, also testified. He told Congress that HIAS had no plans to bring three million Polish Jews to the United States. He bluntly stated:

Now, gentlemen… during the year 1919 we obtained the largest contributions, both in membership and in donations, we have ever received… and the amount of the contributions was $325,000…. Now, I will leave it to you, gentlemen, how much of that $325,000 will be left us to undertake this great plan that somebody is reading about?27

In the end the Senate decided that there was no emergency, nor were there grounds for a general ban on immigration. Still, like their counterparts in the House of Representatives, many senators were uneasy about the “quantity” and “quality” of the nation’s newest arrivals. In 1921, the House and the Senate passed the first of several laws limiting immigration.

In his testimony before the House Committee on Immigration, John Trevor, a New York attorney and member of a group called the Allied Patriotic Societies, proposed that Congress limit immigration country by country to two percent of the number of immigrants from that country living in the United States in 1890. He deliberately ignored the most recent census, from 1920, and chose an earlier one that predated the arrival of most Jewish immigrants. After much debate, a bill containing Trevor’s plan passed by an overwhelming majority in both the House of Representatives (373 to 71) and the Senate (62 to 6). In May 1925, President Calvin Coolidge signed the National Origins Act into law. The new law effectively closed the United States to most Jewish immigrants.

During the debate, Coolidge told the American people,

Restricted immigration is not an offensive but purely a defensive action…. We cast no aspersions on any race or creed, but we must remember that every object of our institutions of society and government will fail unless America be kept American.

Many Americans shared his views. The new law was extremely popular and seemed to solve the nation’s “immigrant problem,” at least for the time being. The problem in Europe was not as easily resolved. There, the notion that “the Jews” were a “nation within a nation” plotting world domination would lead to genocide—an effort to murder all of Europe’s Jews.