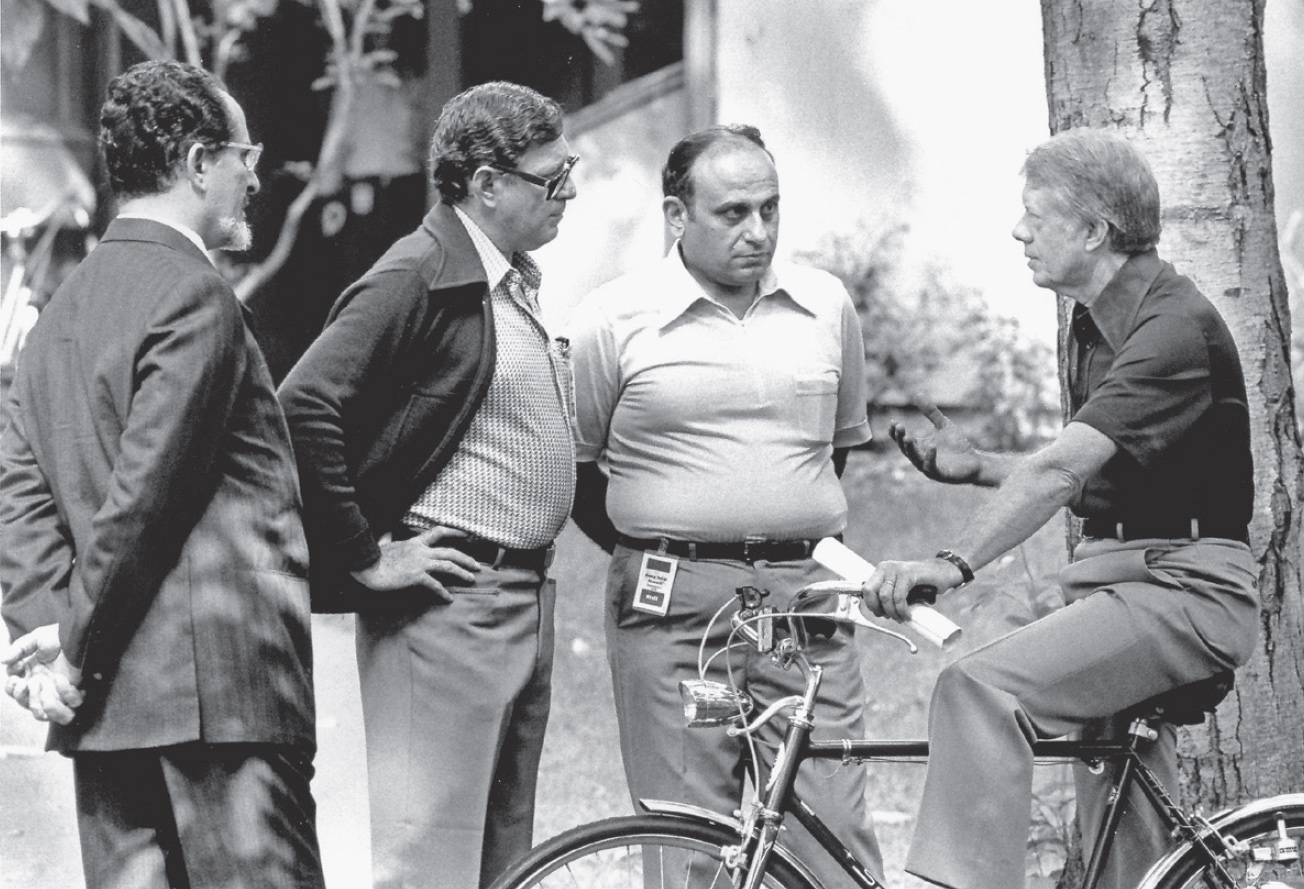

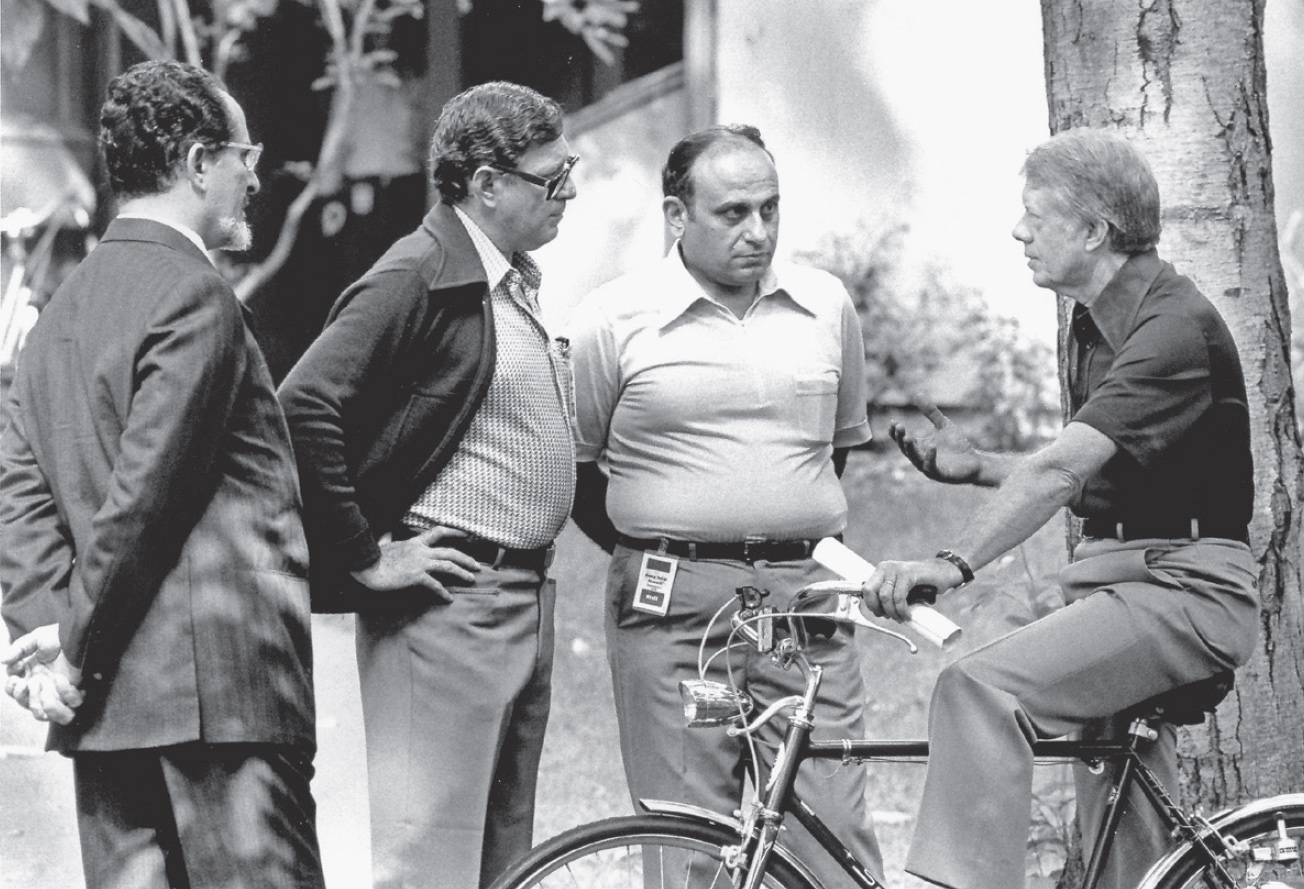

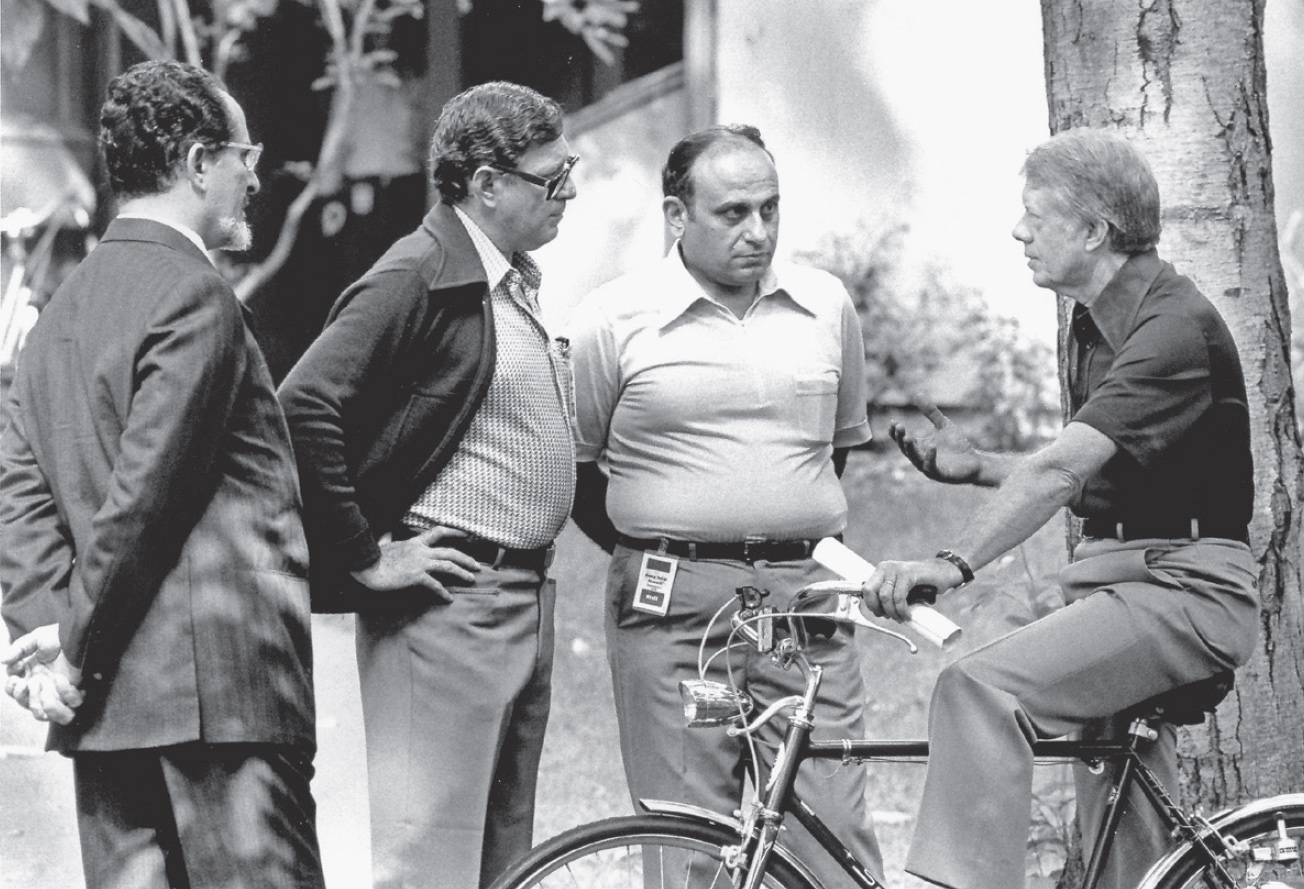

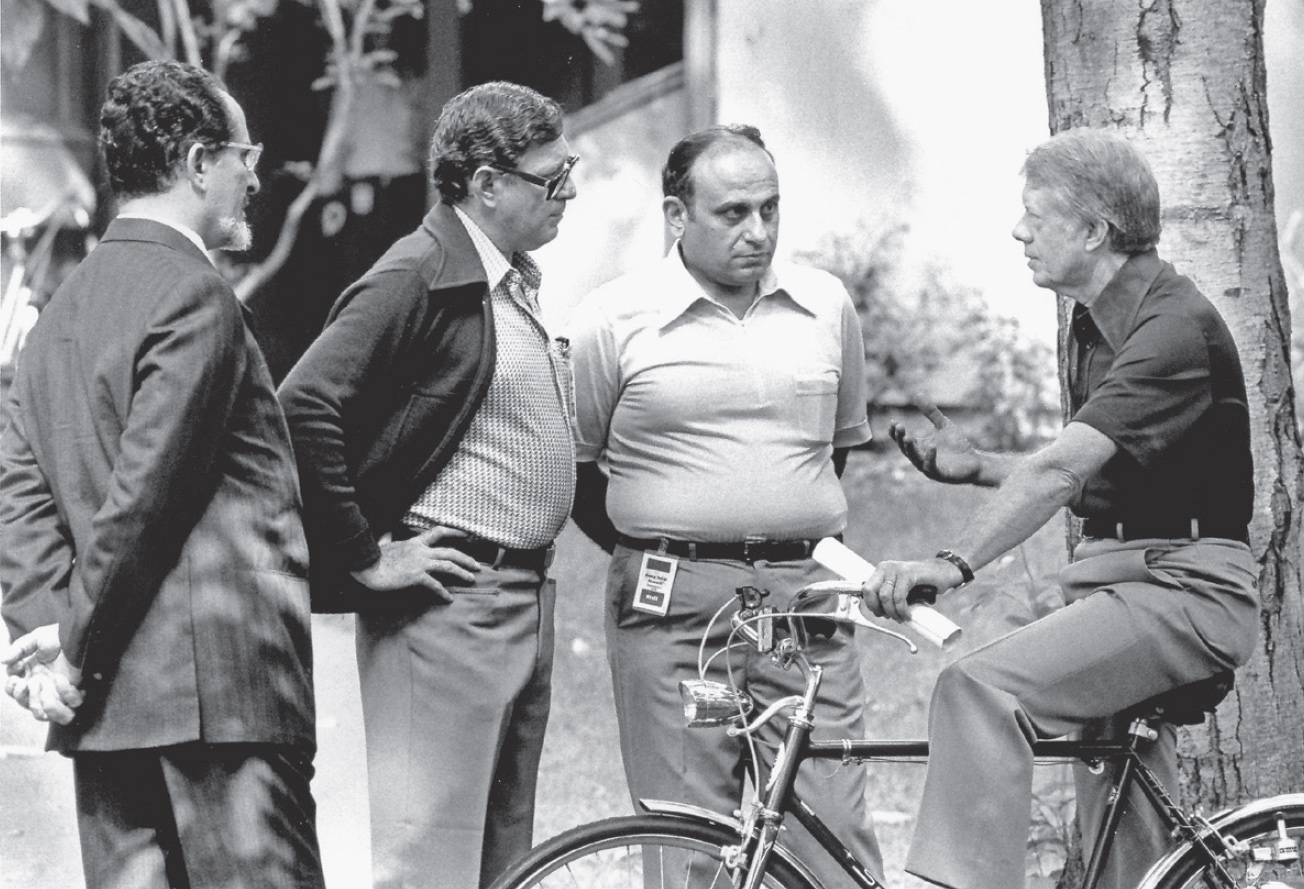

Hassan el-Tohamy, Mohamed Ibrahim Kamel, and Ahmed Maher confer with Jimmy Carter

Hassan el-Tohamy, Mohamed Ibrahim Kamel, and Ahmed Maher confer with Jimmy Carter

AT EIGHT A.M., Jimmy and Rosalynn looked out the window of Aspen Lodge and saw Sadat setting out for his morning constitutional. Immensely relieved, Carter rushed out to join him.

Sadat kept a brisk, military pace as they marched through the forest paths. Carter was in an expansive mood, although he didn’t tell Sadat about his apprehensions of the night before. Sadat confided that since the trip to Gettysburg, he had seen Carter in a different light—as someone who could understand the ravages of war, not just the damage to material things but to the spirit of a defeated people as well. They talked about how long it was taking America to get past the psychic wounds of the Vietnam War. Sadat wondered whether the people of the Middle East would ever recover, even if they made peace at Camp David.

Carter came back to Aspen and went directly to his study. He wanted to work on the latest American draft before Aharon Barak arrived. Rosalynn was headed to Washington again that morning for a luncheon, and before she left she looked in to see what Jimmy’s mood was. When he saw her, he pushed back his chair. “Come here,” he said. Rosalynn sat in his lap. “I think it’s all coming together now,” he said cheerfully.

FROM THE BEGINNING of the conference, Weizman had been urging Sadat and Dayan to meet. He thought that the two of them could break through the psychological obstacles that blocked a settlement. Carter also thought it was important for Sadat and Dayan to talk, because the Israeli foreign minister was the most creative member of the team and also the one most familiar with the West Bank. And yet both men had resisted. Sadat loathed and feared Dayan because he was the architect of the Six-Day War. No Arab could look at Dayan without experiencing once again the flood of shame that followed that overpowering defeat. Moreover, Dayan’s blunt and unsparing manner grated on Egyptian habits of formality and indirection, in which difficult conversations were buttered over with social pleasantries.

For his part, Dayan owed the destruction of his legend to Sadat. He had been minister of defense when Sadat sent the Egyptian Army across the Suez Canal in 1973, shattering the sense of invulnerability that Israel had cloaked itself in. It was Israel’s Pearl Harbor. Dayan had been Israel’s greatest hero, but he got the largest dose of the blame. Before the war, he had been a figure on the cover of magazines around the world, adored by women and courted by statesmen, but after 1973 he was shunned even by people he had never respected—all because of Sadat.

A meeting between the two men was bound to stir up powerful conflicting feelings, even though they were seeking the same goal, perhaps more ardently than anyone else at Camp David. Under pressure, Sadat finally agreed to talk to Dayan, “for Carter’s sake.” That phrase would become an inside joke with the Egyptian delegation, because just when the summit seemed to be on the verge of finding a path to peace, the meeting that neither man wanted would bring everything crashing down.

THE ILLUSION THAT led to Israel’s greatest military setback, and was the source of Dayan’s disgrace, was the Bar-Lev Line. It was one of the great defensive fortifications in military history. Erected after the 1967 war, and stretching a hundred miles along the eastern bank of the Suez Canal, the line presented a sheer, seventy-foot-high sandy rampart facing the Egyptian troops on the western bank, like a mountainous man-made fault line. Buried inside the cliff face were thirty-six Israeli outposts built of reinforced concrete, meant to withstand direct hits from artillery or bombs of more than a thousand pounds. Each fort was equipped with machine-gun emplacements, anti-aircraft weapons, and mortars. In the basement of the multistory forts, there were large containers of oil that could be spewed onto the surface of the canal in order to set the water ablaze. In the intervals between fortifications there were three hundred firing positions for tanks. A second line of defense ran six to eight kilometers to the rear, which included airfields, underground command centers, long-range artillery positions, and anti-aircraft missile bases. All of these positions were encased in multiple circles of barbed wire and studded with minefields and booby traps. Israelis saw the monumental barricade as their first line of defense, but to the Egyptians, the Bar-Lev Line represented Israel’s attempt to confiscate the entire Sinai.

In 1973, Dayan, then minister of defense, took an American diplomat, Nicholas Veliotes, on a tour of the fortifications. They stood atop the mountainous rampart and looked across the canal, two hundred yards wide, at the Egyptian encampment. As usual, the Egyptian soldiers were playing soccer, fishing, and swimming in the canal. Veliotes asked what would happen if Egyptian forces attacked without warning. “The Egyptian Army today is like a ship covered with rust while anchored in harbor and unable to move!” Dayan said dismissively. He was reflecting the consensus of the Israeli defense establishment. Peace no longer seemed necessary or even desirable. Dayan was already drawing up plans to enlarge the State of Israel even more, stretching from the Jordan River to the canal and fortified by new Jewish settlements. “There is no more Palestine,” he told Time magazine in July. “Finished.”

The euphoria of the 1967 victory had blinded Israel to the possibility that Arabs were still capable of inflicting real damage. One after another the Israeli commanders published memoirs and went on television describing their brilliant tactics in the last war and forecasting endless Israeli dominance. An attack by the Arabs was unthinkable, they agreed, suicide.

But as much as the Six-Day War marked a peak moment in the Israeli experience, it was also a turning point for Egyptian society. The defeat acted as a spur to modernization, especially in the military. Before the war, the Arab world treated Israel as if it didn’t exist. Customs officers ripped out pages in imported books that mentioned Israel, including the Larousse French dictionary and Encyclopaedia Britannica. After the war, the Egyptian leader became obsessed with knowing his enemy. Nasser got tapes of the chest-thumping Israeli generals on television, and he watched them for days on end trying to decipher the secret of their success. Obviously, surprise was key; whoever struck first had a decided advantage. Another reason for the Israeli victory was their superior equipment, and so Nasser persuaded the Soviets to resupply the Egyptian forces with better munitions. But those weren’t the only advantages the Israelis enjoyed; their soldiers were simply more capable and better motivated than the Egyptians. Nasser concluded that there would have to be a transformation of the armed forces. University graduates were recruited into the officer corps and encouraged to study Hebrew. Soviet advisers trained the Egyptian troops. Even with all these changes, Nasser had little hope of achieving victory.

When Sadat came to power in 1970, he received a tentative overture from Moshe Dayan for an interim solution: both sides would withdraw outside of artillery range and allow the Egyptians to resume operation of the canal. Sadat responded a few months later with a far more ambitious initiative to declare a cease-fire and sign a peace agreement with Israel through the UN. His price was the return of Sinai to Egyptian sovereignty. Israel could maintain a security presence at key points, such as Sharm el-Sheikh. The Palestinians would be assured of either a state of their own or affiliation with the Kingdom of Jordan. In a secret overture to the U.S., Sadat’s envoy confided to Kissinger that there was a deadline for beginning peace negotiations: September 1973, shortly before the Israeli elections. By that time, Israel would have to make a partial withdrawal from Sinai as a good-faith deposit on the future treaty. Prime Minister Golda Meir rejected the deal. She pressured Kissinger to stall Sadat’s peace overture and maintain the political deadlock until after the elections. In return, Kissinger extracted a fateful promise that Israel would not initiate another war.

With the failure of his initiative, Sadat announced that “the stage of total confrontation” was about to begin. “Everything in this country is now being mobilized in earnest for the resumption of the battle—which is now inevitable,” he told Newsweek in April 1973. “The time has come for a shock.” Nobody believed him. In Egypt, he had become a laughingstock. The complacent Israelis ignored the buildup of troops along the canal that fall, which they accounted as another pointless maneuver by the feckless Egyptian leader. After all, without the Soviets, Egypt would have to fight on its own, or with another weakened Arab state. The assumption was that, because the Arabs would lose, they wouldn’t start a war. This idea was so sensible that the Israelis were deaf to any other argument. Menachem Begin warned of the need to counter the movement of a large number of Egyptian tanks near the canal, but he was a lone voice. The canal itself was the greatest tank trap ever devised, Israeli defense specialists observed, to say nothing of the formidable Bar-Lev Line. Even as the experts told themselves this, however, Israel was gradually scaling down its canal defenses. About a third of the outposts were sealed with sand and left as dummy fortifications, and troop levels were reduced in those that remained.

Dayan had threatened that, in the event of war, “I don’t rule out planning to reach the Nile.” He had always viewed war as an opportunity to expand Israel’s borders, and as the secret September deadline approached, he began boldly speaking of “a new Israel, with wide borders, not like in 1948.” He advocated for more settlements in Sinai and Golan to consolidate Israel’s occupation. He announced the construction of an Israeli port in northern Sinai, in Egyptian territorial waters. All this confirmed in Sadat’s mind that the Israelis were never going to willingly surrender Egyptian territory. War was the only recourse.

Egyptian military planners spent years studying the challenge before them. First, they had to get their troops across the canal. That objective was broken down into discrete tasks, such as backing trucks up to a water barrier and braking so abruptly that the momentum hurled segments of a pontoon out of the truck bed into the water. Twice a day for four years crews worked to unload the trucks in exactly this manner; meantime, other crews trained to bolt the floating segments together to form a bridge. Once the first wave got across, Israeli tanks would be waiting to greet the infantry; in order to blast through that armored barrier, Egyptian teams that would be operating the new handheld Soviet Sagger anti-tank missiles trained every day in a simulator. Endless repetitions made such actions second nature, even among soldiers who doubted they would ever be put to use.1

But the biggest challenge facing the attackers was the formidable Bar-Lev Line. The Russians had told them that only an atom bomb could destroy it. Neither conventional bombs nor artillery could blast open passages in the rampart; the sand just collapsed and filled in the hole. Finally, Egyptian engineers came up with an ingenious solution: they discovered that high-pressure fire hoses connected to turbine-driven German pumps, capable of spewing a thousand gallons a minute, could melt the sand away with seawater drawn right from the canal. Replicas of the barricade were built and blasted down day and night, until the teams could punch a twenty-foot-wide corridor through the wall of sand in the space of five hours. After that, the infantry and the tanks would pour through. Sadat labeled the plan Operation Badr, a reference to the siege of Mecca in 624 CE, by the Prophet Muhammad, in which the Quran says he was assisted by three thousand “havoc-making” angels.

Many considerations went into the timing of the invasion—for instance, the tide should be low and the sun in the eyes of the defenders. Syria planned to attack simultaneously, but there was a possibility of snowfall in the Golan Heights in the late fall. October was the optimum time, with its long nights and moderate weather. As it turned out, the Israelis would also be in the middle of its parliamentary election, and the Americans were hypnotized by the Watergate scandal. October that year was also Ramadan, the fasting month for Muslims, which would make an invasion seem less likely to Israelis but which only enhanced the religious significance of the occasion for the Egyptians. There was one date that leaped out to the military planners: Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, which fell that year on October 6. Ordinary activity in Israel would come to a near-total halt—no buses, no radio, no television—meaning it would be difficult to call up the reserves. The moon that day would shine from sunset to midnight.

On October 4, the remaining Soviet families in Egypt and also in Syria were evacuated—another clear signal that war was imminent. The next day, Israeli aerial reconnaissance discovered five Egyptian divisions poised on the western bank of the canal, along with mobile bridge units and an additional fifty-six batteries of artillery; even in the face of all this, the Israeli cabinet still refused to believe that the Arabs would actually attack. Perhaps the memory of the Egyptian soldiers fleeing in their underwear in 1956 still played in Dayan’s mind, blinding him to the blow that was about to fall. But he wasn’t alone. Israeli military leaders largely agreed that the likelihood of war breaking out was “the lowest of the low.”

The night before the invasion, Egyptian frogmen swam across the canal to sabotage the fuel lines that were meant to incinerate any assault vessels that attempted to cross. Syria had already moved up missile batteries within range of Golan. That same evening, Israel sent a message to Kissinger assuring him that war was unlikely.

Then, in the very early morning of October 6, Israeli intelligence notified military authorities that they had gotten word from a well-placed and trusted spy—actually, Nasser’s son-in-law and Sadat’s confidant, Ashraf Marwan—that the Egyptian forces were going to invade at six p.m. that evening. A meeting took place in Dayan’s office before dawn. He still opposed a general mobilization or a preemptive air attack. Mindful of Israel’s secret pledge to Kissinger not to start a war, he argued that Israel’s regular army should be able to absorb a first strike and quickly organize a massive retaliation; later that morning, however, Meir overruled him and authorized the mobilization of 100,000 troops. It would still take at least twenty-four hours for them to reach the Egyptian front.

The Egyptians were puzzled by the lack of response on the Israeli side; their intentions had been obvious since the spring, when Sadat had publicly spelled out exactly what was going to happen. And yet, on the day the war began, on the Bar-Lev Line itself there were only 436 Israeli soldiers, 3 tanks, and 70 artillery pieces, with an additional 8,000 men and 277 tanks in the rear. They were facing 100,000 Egyptian troops and 1,550 tanks on the western shore.

At 2:05 p.m., the Egyptian artillery—nearly two thousand guns—opened up, raining more than ten thousand shells per minute on Israeli positions. Fifteen minutes later, eight thousand commandos and engineers burst over the western bank and jumped into rubber dinghies. Each of the 750 boats had been numbered and color-coded to avoid confusion. Meantime, low-flying Egyptian jets struck Israeli air bases, anti-aircraft missile batteries, command centers, and radar stations. Simultaneously, from the east, seven hundred Syrian tanks charged toward Israeli positions on the Golan Heights.

When the Egyptian commandos reached the eastern bank of the canal, they scaled the massive barricade of the Bar-Lev Line on rope ladders and planted Egyptian flags atop the fortifications. Water pumps began blasting through the sand. Within a few hours, sixty passages had been opened in the line. Five infantry divisions crossed in a continuous flood—on bridges, boats, some soldiers even swam. “My God,” an Israeli radioman reported to the rear defenses, “it’s like the Chinese coming across.”

The Israeli Air Force, slow to get off the ground, arrived two hours later, but they were knocked out of the sky by heat-seeking SA-6 missiles, which took out twelve Phantom jets before the stymied Israelis turned back. Israeli tank squadrons—so devastating in the previous war—rushed from their rear-guard positions toward the canal to relieve the surviving defenders. Egyptian commandos were waiting for them with wire-guided Sagger missiles. The Israeli tanks were wiped out. Eight bridges were in place by ten thirty p.m., and by midnight the first five hundred Egyptian tanks had crossed to the eastern shore. In Cairo, the fundamentalists passed out pamphlets claiming that the angels of havoc were once again fighting with the Muslims. Sadat had to remind his countrymen that the first Egyptian general to cross the canal was not a Muslim but a Copt.

The Arabs now had better weapons, but the soldiers themselves were also different, Dayan realized: they were well trained and disciplined, and they did not run away. Moreover, they had the crucial advantage of striking first. That evening, however, Dayan went on television to reassure his fellow citizens that he had the situation under control. “In the Golan Heights, perhaps a number of Syrian tanks penetrated across our line,” he conceded, but it was nothing to worry about. As for the canal, Dayan said, the Egyptian attack “will end as a very, very dangerous adventure for them.” The truth, he knew, was that Israel was fighting a war on two fronts and losing both of them. Within twenty-four hours, the Arabs had destroyed two hundred Israeli tanks and thirty-five aircraft, and several hundred troops had been killed.

Shaken out of his complacency, Dayan underwent a personal transformation. He was forced to acknowledge that the Arabs were his equals; and if that was true, the very existence of Israel was at stake. Israel could not match losses with those of Egypt and Syria, which had combined forces of more than a million troops. The entire population of Israel was only three million.

The mission of the Arab armies was to recapture the territory lost in 1967. The Syrians sought to take the Golan Heights and hold their positions for four or five days—long enough for the Egyptian forces to capture the mountain passes in Sinai. Sadat hoped that the shock of the attack would then allow for diplomatic flexibility on all sides, which was impossible as long as the Arabs felt immobilized by humiliation and the Israelis comforted by the status quo. But the Israeli leaders did not believe the Arabs would fight a war for limited aims; the rhetoric of Arab leaders in the past still rang too loudly in the Israeli imagination—of being wiped off the map, thrown into the sea—and so they panicked. Once again, it wasn’t war they feared, it was extinction.

On the morning of the second day, Dayan urged the air force to concentrate on stopping the Syrian advance in the north, where Israel was most vulnerable, but the Israeli planes failed to take out the anti-aircraft missiles, and seven aircraft were shot down. Dayan warned Golda Meir that a catastrophe was unfolding; it was necessary for Israeli forces to withdraw from the Golan Heights and pull back in Sinai to the mountain passes, and then “hold on to the last bullet.” The prime minister and the cabinet were shocked by his forecast, but on the third day, when the Israeli counterattack in Sinai began, Israeli military leaders showed themselves to be disoriented, frightened, and at odds with each other about how to counter the Egyptian thrust. Israeli losses by the end of the day reached forty-nine aircraft and five hundred tanks. The situation seemed even worse than Dayan had described.

Dayan said he intended to go on Israeli television and level with the Israeli public on the perilous state of affairs, but Meir begged him not to. They huddled that night in the huge underground command center. If the nightmare that the Israelis imagined came true, and the vast Arab armies broke through their defenses, then the final line of defense would come into play: nuclear weapons. Israel had never admitted to having such weapons, but it was widely known that it had a small arsenal—perhaps as many as twenty-five bombs—that could be deployed in such a case. Dayan had suitably titled the apocalyptic strategy the “Samson Option.”

What happened that night is still unclear. The Israelis may have decided to arm several nuclear bombs in case of a total military collapse. There was also the possibility of using the threat of a nuclear response as a way of coaxing Washington into resupplying the Israeli forces. William Quandt, who was later at Camp David, was the lead staff member of the National Security Council at the time; he recalls seeing a report that Israel had activated its Jericho ballistic missile batteries, which he presumed would be for nuclear weapons because of their rather poor accuracy.

Meir offered to come to Washington to beg the U.S. to immediately resupply Israel with arms, but a shocked Henry Kissinger rejected the idea at once. That Meir would consider leaving Israel leaderless at such a critical period of time showed both the degree of Israel’s desperation as well as its abject dependence on the U.S. It also demonstrated the gulf between the American and Israeli perceptions of the danger that Israel actually faced. Kissinger never doubted that the Israelis would ultimately prevail, but he didn’t want to see the Arabs thoroughly humiliated again, and he certainly wanted to avoid a superpower confrontation. Total victory left little room for peace negotiations, as the previous war had proved. He readily agreed to resupply the Israeli forces, but in so doing he hoped to manage the scale of the Israeli triumph. The best course, he believed, was to let Israel “bleed a bit but not too much.” Meantime, the Soviets began resupplying Syria and Egypt. The involvement of the superpowers dangerously raised the stakes.

By October 11, Israel had gained the advantage on the Syrian front, with Dayan threatening to send his forces into Damascus. Hoping to relieve his Syrian ally, Sadat hurled an Egyptian force of fifteen hundred tanks against a comparable Israeli force in Sinai. It was one of the largest tank battles in history, and one that the Israelis, backed by anti-tank missiles fired from helicopters, decisively won. The Egyptians had ventured outside their umbrella of air support and lost 250 tanks in a single day.

Immediately following that victory, the Israelis launched a counterattack, led by Major General Ariel Sharon, against a much larger Egyptian force near the southern part of the Suez Canal at a place called the Chinese Farm, because the agricultural equipment had markings that the troops took to be Chinese (in fact, it was Japanese). The goal was to break through the Egyptian line and cross the canal—a brilliant and totally unexpected strategy, one that would leave the Egyptian forces stranded on the eastern bank.

The Israeli assault started the morning of October 15, meeting no initial resistance, but it soon developed into the bloodiest encounter of the war; with armor, infantry, and air support, each side was horribly mauled for three days and nights. Finally, at dawn on October 18, the Israelis managed to place a pontoon bridge across the canal and their forces streamed across. The war took a decisive turn.

Dayan flew to the Chinese Farm to view the carnage. Arab and Israeli soldiers lay side by side, their weapons and personal equipment strewn all over the battlefield. There were hundreds of burned-out and mutilated vehicles, still smoking, and destroyed Israeli and Egyptian tanks that were frozen in place only yards away from each other. “I am no novice at war or battle scenes,” Dayan recalled, “but I had never seen such a sight, neither in action, nor in paintings nor in the most far-fetched feature film. Here was a vast field of slaughter stretching all round as far as the eye could see.”

Sadat stopped eating, living only on fruit juice. He saw his chances of recapturing Sinai slipping away. He grew pale and gaunt and began urinating blood. He just learned he had lost his younger brother Atif in the first five minutes of the war, when his jet was shot down over the canal. Jehan Sadat couldn’t bring herself to deliver the news for four days. The only time she had ever seen her husband cry before this was when his mother died. “All those who died for our country, who sacrificed themselves, are my sons,” he told her. “Even now my own brother.”

On October 17, a new and strikingly modern element of warfare came into play. Arab oil producers met in Kuwait and announced an immediate cut of production by 5 percent, with similar reductions every month until Israel had withdrawn from all the occupied territories. Moreover, they embargoed the sale of any oil at all to the United States. Three days later, Kissinger flew to Russia.

Once in Moscow, he struggled to confine the agenda to a proposed cease-fire, which the UN Security Council passed early in the morning of October 22 and Egypt accepted at once. Nixon had impulsively dashed off a letter to Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev reviving the old notion that the superpowers simply impose peace on the Middle East. With the Watergate scandal in full blaze, Nixon yearned for a foreign policy triumph that would confound his critics, and peace in the Middle East was the biggest prize imaginable. Brezhnev was enthusiastic, but the last thing Kissinger wanted was for the Soviets to find a way to recapture their eroding influence in the region.

Kissinger then flew to Israel. Over a tense and emotional lunch with Meir and her cabinet, Kissinger observed the psychological damage that the war had inflicted on the Israelis, made especially acute by their previous complacency. Kissinger’s sympathetic eye fell on the melancholy figure of Moshe Dayan. They had known each other for nearly twenty years. No other Israeli so impressed him with his imaginative and nimble intellect. Although Dayan was famous for his military genius and his punitive raids against Arabs, he also stood out among his colleagues because of his sympathy for their plight. In Kissinger’s opinion, he was the Israeli statesman best suited to lead the country to peace, and yet Israelis were now treating him almost as a traitor. Three thousand Israeli soldiers had already perished in this war. There were pickets carrying signs with his iconic face on them, but they were inscribed “MURDERER.”

The Israelis wanted revenge, as if that could restore their reputation for invincibility. But the crossing of the Suez Canal by Egyptian forces had shattered that illusion. Sadat had turned the tables on them, and the rage that the Israelis felt rendered them unable to restrain themselves. Meir complained that the cease-fire came too soon; she demanded another three days of fighting in order to surround and destroy the Egyptian Third Army, which was stranded on the east bank of Sinai at the southern end of the canal. Kissinger wouldn’t sanction that, but he added, “You won’t get any violent protests from Washington if something happens during the night, while I’m flying. Nothing can happen in Washington until noon tomorrow.”

While Kissinger was flying back to Washington, Brezhnev sent an alarming note to the White House, resurrecting Nixon’s suggestion of an imposed peace by U.S. and Soviet forces; if that didn’t happen, he warned, the Soviet Union would act unilaterally. Three Soviet airborne divisions were placed on alert and a naval flotilla was actually on its way to Egypt, intent on liberating the Third Army. Nixon—under siege, distraught, drinking heavily—was entirely preoccupied by Watergate. Kissinger worried that the Soviets were trying to take advantage of this chaotic moment in American politics. If they returned to the Middle East in the role of the savior of the Arabs, they would be able to influence the oil producers and threaten world economies. To block that scenario, Kissinger was willing to steer the superpowers to the brink of nuclear war.

The threat level in the U.S. is denominated by five defense readiness conditions. The lowest, DEFCON 5, represents a state of calm; the highest, DEFCON 1, is all-out thermonuclear war. Kissinger decided to send an urgent and unmistakable message to the Soviets, and—without involving the president—he and members of the National Security Council raised the threat level to DEFCON 3—the highest it had been since the 1962 Cuban missile crisis. He also put the 82nd Airborne Division on alert—troops were actually loaded onto transports and were waiting on the runway for the order to fly to Israel. He then sat back, expecting the Soviets to blink, but the flotilla continued toward Egypt.

In a totally unexpected reversal of the forces at play, Sadat saved the superpowers from the clash they were drifting toward. He asked the UN Security Council to provide an international force—one that excluded the United States and the USSR—to oversee the cease-fire. Without a willing client, the Soviets finally backed off, but Israel still refused to take its hands off the throat of the Third Army, which was withering in the Sinai desert, without food or water or even medical supplies.

Once again, Sadat rescued the situation. He suddenly announced that he was willing to engage in direct talks with Israel at the 101-kilometer mark on the Suez–Cairo road—the first time any Arab country had agreed to such an arrangement since the State of Israel was born. In return, Israel finally agreed to let a single convoy of nonmilitary supplies reach the Third Army.

Kissinger had come to deeply admire Sadat without ever having met him. Until the outbreak of the war, he had regarded the Egyptian president as “a buffoon, an operatic figure,” but again and again Sadat had surprised him, not only with his vision and courage but also with his adroit moves in the complex game of international chess of which Kissinger was the acknowledged master. Few leaders on the world scene played at a level that even interested him, but now he recognized in Sadat an instinctive genius for the bold stroke that could change history.

Kissinger had never actually visited an Arab country, but on November 6 he landed in Cairo to negotiate a truce between Israel and Egypt. Sadat began by taking the American into his office and showing him some situation maps outlining a proposed disengagement scheme. “It can be called the Kissinger Plan,” Sadat said coyly. He proposed that the Israelis withdraw halfway across the Sinai Peninsula. Kissinger observed that unilateral withdrawal was not a feature of the Israeli diplomatic vocabulary. Sadat puffed on his pipe, his eyes narrowed and unfocused. Kissinger went on to suggest that the key was to build up confidence so that the Israelis could trust in the outcome. The problem was mainly psychological, not diplomatic, he said. The best course of action was to leave the Third Army where it was—trapped—but with a steady source of supply, while the U.S. worked to disentangle the forces.

Kissinger was asking Sadat to trust an American he had never met, one with no experience in Middle East diplomacy, while keeping his army cut off in the desert for weeks or possibly months. If anything went wrong—if Kissinger couldn’t deliver, if the Third Army cracked under pressure—then Sadat would be ruined and Egypt humiliated once again. Sadat simply accepted, surprising Kissinger once again.

It would take heroic personal diplomacy on Kissinger’s part—shuttling back and forth between Israel and Egypt in mid-January 1974—to finally achieve the agreement that he promised, requiring each side to pull back from the canal and thin out their military forces along the front. The basic recipe for negotiating peace between Egypt and Israel was a bold Egyptian leader willing to talk, a cautious Israeli leader still willing to trust, and tireless American diplomacy to press them to make the peace that they couldn’t achieve on their own. But real peace was not yet in view.

CARTER’S PLEA WORKED. Sadat sent Tohamy to issue the invitation to Dayan to visit his cabin for tea at three p.m. When Carter found out about the meeting, he asked Dayan not to discuss the issues. He worried that each man would become more entrenched in his position and the conference would once again become deadlocked. The only goal of the meeting should be to reduce the tension between them. Dayan pledged to talk only of “camels and date-palms.”

Sadat received Dayan with a polite smile. As his manservant served honeyed mint tea, Sadat accused the Israelis of destroying the summit because of their stubborn refusal to give up the Sinai settlements, the most notable of which was Dayan’s pet project—a proposed new city in northern Sinai, complete with high-rises and movie theaters, projected to have a quarter-million inhabitants within twenty years. Ground had been broken and bulldozers were at work at that very minute. “What did you think, that we would resign ourselves to its existence?” Sadat asked testily.

Dayan forgot all about his promise to Carter. He recalled Nasser’s rejection of the Israeli offer to return Sinai after the 1967 war in exchange for peace. “What was your reply?” he asked. “What was taken by force, you said, would be recovered by force.” He added, “What did you think we would do, sit with folded arms, while you announced that you were not prepared to reconcile yourself to Israel’s existence?”

“If you want peace with us, the table has to be cleared,” Sadat said. He was willing to make a full peace with Israel, despite the opposition of the Arab states, “but you must take all your people out of Sinai, the troops and the civilians, dismantle the military camps and remove the settlements.”

“If anybody told you that any Israeli government could give up the Sinai settlements,” Dayan said, clearly referring to Tohamy, “they were deluding you.” The settlements formed a security belt to protect the Jewish homeland, not only against Egypt but also against Palestinian guerrillas, who infiltrated Israel from the refugee camps in the Gaza Strip. If the Egyptians did not agree to the terms, Dayan said imperiously, “We shall continue to occupy the Sinai and pump oil.”

Sadat exploded. “Convey this from me to Begin!” he cried. “Settlements, never!”

Right after this disastrous meeting, Carter dropped off the draft of a new American proposal. Sadat glanced at it and said he would only negotiate on when the settlements would be withdrawn, not if. All his previous flexibility had boiled away in his wrath at Dayan.

At this juncture, Carter had no idea how to bridge the gap between the two sides. He went to Dayan and asked for his advice. The unrepentant Dayan told him the best approach was to draw up a list of the differences that remained on both sides to show that ten days of work had not been totally in vain. Dayan himself had given up on further progress.

The Egyptian delegation also wondered where Sadat now stood. Kamel went to see him, and found Sadat lying on his couch in his pajamas watching television. “Hi, Mohamed, take a seat!” he said, without getting up. He continued to watch the show. In a little while, other members of the delegation, including Tohamy and Boutros-Ghali, joined them. They were speaking about matters far from Camp David, and Kamel’s mind had wandered, when suddenly he heard Sadat shouting, “What can I do? My foreign minister thinks I’m an idiot!” Then he ordered everyone out of his cabin.

Kamel started to leave, then turned to Sadat. “How can you allow yourself, in front of all these people, to accuse me of considering you an idiot? Would I work with you if I thought you were?” He then announced that he intended to resign as soon as they returned to Cairo.

“Wait, Mohamed,” Sadat said. “Come and sit down.”

Kamel remained standing.

“What’s the matter with you, Mohamed?” Sadat asked. “Don’t you know what I’m going through? If you don’t bear with me, who will?”

“I feel what you feel, but that was no reason for you to address me in such a manner in front of anybody—I wouldn’t take it from my own father!”

“I really am sorry, it’s all the fault of this cursed prison we find ourselves in,” Sadat said. “Why don’t you sit down?”

“It is midnight and I feel like a walk,” Kamel said, still steaming.

ROSALYNN HAD SPENT the day in Washington. When she left that morning, success was in the air. All during a White House luncheon for a local community foundation, she had to fight down a smile. Any emotion could give a hint of how the talks were going, so she remained as poker-faced as possible. When she returned to Camp David that afternoon, she was surprised to see Carter, Brzezinski, and Hamilton Jordan in the swimming pool. The men were laughing in a way that struck Rosalynn as odd. She immediately knew something was wrong.

The talks are over, they told her.

“You’re teasing,” she said desperately. “I know you’re teasing me.”

“No,” Carter said. “We’ve failed. We’re trying now to think of the best way of presenting this failure to the public.”

Carter directed Vice President Mondale to clear his calendar in order to help him manage the political damage. Vance came by the Carter cabin later for martinis. He consoled Carter, saying that he had accomplished everything he could have expected, but feelings on both sides just ran too deep to achieve any major breakthroughs. That night, as Dayan advised, Carter sat down and made the list of items that separated the two sides. It was heartbreaking to see how insignificant the differences really were when measured against the enduring advantages of peace.

1 In an Israeli survey of eight thousand Egyptian prisoners captured during the war, only one said he knew that an actual war was imminent three days before the battle, and 95 percent of the soldiers said they learned of it the day of the actual invasion. Herzog, The War of Atonement, p. 39.