LATE ONE NIGHT in a rustic lodge on the edge of Jackson Lake, in the Grand Teton National Park, Jimmy Carter took a break from his vacation to open a thick briefing book compiled for him by the Central Intelligence Agency. He had spent one last glorious day, August 29, 1978, fly-fishing on the Snake River, horseback riding through the park, and picking huckleberries with his daughter, Amy, which went into an after-dinner pie. It was a brief escape from the tumult of Washington and his weakened and unpopular presidency. The briefing book contained psychological profiles of two leaders, Anwar Sadat, the president of Egypt, and Menachem Begin, the prime minister of Israel, who would be coming to America in a few days with the unlikely goal of making peace in the Middle East. The ways in which Carter would relate to these leaders—and they to each other—would determine the success or failure of this historic gamble.

The man reading the book had entered the presidency with little experience in foreign policy. He had grown up in the rural South and served a single term as the governor of Georgia. He had never met an Arab until he sat next to one at a stock car race in Daytona. The only Jew he had known as a child was Louis Braunstein, an insurance salesman in Chattanooga, who married Carter’s aunt. Uncle Louie loved professional wrestling and could chin himself with one arm—a feat that had thrilled the young Carter. There were a few Jewish merchants in Americus, Georgia, near Carter’s hometown of Plains, and Carter always thought of them as “exalted” people, in part because of his Bible studies, which informed him that God had chosen them above all others. It wasn’t until he became governor and moved to Atlanta that Carter became familiar with the genteel but ingrained anti-Semitism of the urban South that kept Jews out of country clubs and off government boards.

In 1973, while he was governor, Carter and his wife, Rosalynn, made a pilgrimage to the Holy Land. Prime Minister Golda Meir lent them an old Mercedes station wagon with a driver, and they rode through the tiny country—less than one-eighth the size of the state of Georgia. Rosalynn wept at the commercialization of the holy sites, but Jimmy told her it was just like that when Jesus overturned the tables of the money changers in the temple. They crossed into the occupied West Bank, where they got special permission to wash themselves in the River Jordan, where Jesus was baptized. The river was not much bigger than a creek in south Georgia, but it echoed in Carter’s imagination. He had studied the Bible since he was a child, and the geography of ancient Palestine was more familiar to him than that of most of the United States. He could mentally trace the journey of Abraham from the Mesopotamian city of Ur to Canaan’s sere and rocky landscape two thousand years before Christ was born. To walk the same streets where Jesus walked, to stand in the hallowed shrines, and to wade into the Jordan filled Carter with awe and a dawning sense of purpose.

Few people knew he was secretly planning to run for president—indeed, scarcely anyone outside of Georgia had ever heard of him—but becoming familiar with Israel and its problems was essential for any aspiring national politician. Carter visited several Jewish settlements in the territories that had been occupied by Israel since the Six-Day War in 1967. Israel was still dizzy with euphoria following its lightning victory over four Arab armies, which left it in control of the Golan Heights of Syria, the entire Sinai Peninsula of Egypt, the Gaza Strip, the West Bank of Jordan, and the great prize—the Old City of Jerusalem. United Nations Resolution 242, adopted after the war ended, provided guidelines for ending the conflict, including the termination of all claims of belligerency, acknowledgment of the sovereignty of the states in the area, and respect for the residents’ right to live with secure and recognized borders free from the threat of force. It also obliged Israel to withdraw from land it had seized during the war, but the country’s leaders were in no hurry to abandon the 28,000 square miles of occupied territories, which had tripled the size of the country. The question of what to do with a million and a half Arabs living in those territories was rarely addressed, although they posed a potentially fatal demographic threat to the Jewish state, which contained 2,385,000 Jews at the time, along with 100,000 Christians and the 290,000 Arab Muslims who had not fled.

Menachem Begin, then head of a new minority coalition called Likud, was among the most strident of those arguing for the need to hold on to the gains of the war, especially the West Bank, which he called by its biblical names, Judea and Samaria. Begin’s ideology envisioned a vastly expanded Israel; he did not even acknowledge the existence of the Kingdom of Jordan, which he believed should be conquered and folded into an exclusively Jewish nation—a dream he never entirely surrendered. Many Israelis considered him a crank, a fascist, or just an embarrassing reminder of the terrorist underground that stained the legend of the country’s glorious struggle for independence. “Begin is a distinctly Hitleristic type,” David Ben-Gurion, Israel’s revered founder and first prime minister, wrote of his lifelong political antagonist. “He is a racist who is willing to kill all the Arabs in order to gain control of the entire land of Israel.” Prominent American Jews, including Hannah Arendt and Albert Einstein, denounced Begin’s career as a terrorist chieftain. “Teachers were beaten up for speaking against them, adults were shot for not letting their children join them,” they wrote to The New York Times in 1948, when Begin made his first trip to the U.S. “By gangster methods, beatings, window-smashing, and widespread robberies, the terrorists intimidated the population and exacted a heavy tribute.”

Few could have imagined, when Governor Carter was visiting the Holy Land and Begin was still on the fringe of Israeli politics, that only four years later these two outsiders would be leading their respective countries.

Israel, as Carter experienced it then, was hopeful, prosperous, and surprisingly complacent. The only men in uniform were traffic police. Arabs from the West Bank traveled freely into Israel proper, and a crush of Jewish tourism, along with liberal investment, had raised the standard of living for Palestinians well above what they had endured under Jordanian rule. There were some troubling signs, however. Carter estimated that there were about 1,500 Jewish settlers on the West Bank and in Gaza then, but he could already see that they posed a formidable threat to peace. He and Rosalynn attended a service at a synagogue on the Sea of Galilee and were shocked that there were only two other people present. When they returned the station wagon to Golda Meir, she asked if Carter had any concerns. He knew that Meir, like all her predecessors in that office, was a secular Jew, so he hesitated before mentioning his experience in the synagogue and the general lack of interest in religion that he found in the country. He pointed out that in the Bible whenever Jews turned away from God they suffered political and military losses. Meir laughed in his face. The governor of Georgia! But that very fall, Anwar Sadat sent the Egyptian Army across the Suez Canal, catching the Israelis by surprise and waking the country from a dream of invulnerability. Meir was forced to resign the following spring. Meantime, the Carters returned to Georgia committed to helping Israel in any way they could. The governor began speaking of Meir as “an old friend,” although they had met only that one time.

Soon after he arrived in the White House, Carter began to focus on the Middle East. Walter Mondale, his vice president, was struck by the fact that on Carter’s first day in office he announced that peace in the Middle East was a top priority. That seemed wildly naive. One after another, American presidents had waded into the fray, at great political expense and with little to show for their efforts. Former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, who had spent years under Presidents Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford trying to disarm the explosive temperaments in the Middle East, warned Carter that no American president should ever become involved in a negotiation where the outcome was in doubt. Carter’s closest advisers told him that he should wait until his second term to risk any of his fragile political capital. His approval rating with the American public had reached 75 percent in his first months in office, but it had been plummeting ever since. For Carter, however, this was not entirely a political decision. He had come to believe that God wanted him to bring peace, and that somehow he would find a way to do so.

The dangerous political calculus of this venture was baldly laid out for him in a memo written by his former campaign manager, Hamilton Jordan, which was so sensitive that he typed it himself and kept the only copy in his office safe in the White House. Jews were an outsized presence in American political life, Jordan explained. “Heavy support for the Democratic Party and its candidates was founded in the immigrant tradition of the second and third generation of American Jews and reinforced by the policies of Wilson and Roosevelt,” he wrote. “Harry Truman’s role in the establishment of Israel cemented this party identification.” Although Jews were only 3 percent of the American population, they cast nearly 5 percent of the vote, with turnout close to 90 percent in most elections. In New York State, for instance, Jews and blacks made up about the same percentage of the population, but in the election that brought Carter into the White House, only 35 percent of the black community in New York cast ballots, compared with 85 percent of the Jews. “You received 94% of the black vote and 75% of the Jewish vote,” Jordan wrote. “This means that for every black vote you received in the election, you received almost two Jewish votes.” More than 60 percent of the large donors to the Democratic Party were Jewish, Jordan pointed out. Jews maintained a “strong but paranoid lobby”—the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC)—which reflected the attitudes and goals of the government of Israel and controlled a reliable majority of votes in the U.S. Senate. Carter was a southerner with an unknown history, at least to Jewish leaders. He had made statements in public—about secure and recognized borders for Israel, the need for a Palestinian homeland—that were usually conveyed behind closed doors, which caused Jordan to worry that Jews were already lining up to take a stand against Carter: “I am sure you are familiar with Kissinger’s experience in the Spring of 1975, when the Jewish lobby circulated a letter which had the names of 76 senators which reaffirmed U.S. support for Israel in a way that completely undermined the Ford-Kissinger hope for a new and comprehensive U.S. peace initiative.” The tenor of the memo was that Carter stood to make a formidable enemy of the Jewish community if he brought pressure to bear on Israel, which he would have to do if he hoped to achieve a peace agreement. Jordan, his chief political adviser, was telling him this was a no-win situation. It was a paradox: nothing could be a greater gift to Israel than peace, and nothing was more politically dangerous for an American politician than trying to achieve it.

Carter’s immediate goal was to restart talks at the Geneva Conference on the Middle East. The Geneva Conference had met once in 1973, under the auspices of the United Nations, the United States, and the Soviet Union; it then went into recess and disappeared into the wasteland of good intentions. In his first year in office Carter set about meeting the most prominent Arab leaders—a discouraging ritual, beset with overheated rhetoric and impractical demands. And then Anwar Sadat came to the White House. Carter was immediately taken by him. By comparison with the other Arab heads of state, Sadat was a “shining light” who was “extraordinarily inclined toward boldness.” At last, Carter believed, he had found a partner for peace. The president had a penchant for exaggerating personal connections, perhaps trying to disguise the fact that he was a highly controlled and remote personality who let few people get close to him; still, Carter’s aides saw that he and Sadat were genuinely smitten with each other. Soon after that first meeting, Carter began speaking of the pious Egyptian autocrat as his “dearest friend,” words rarely used by heads of state.

Carter also met with the Israeli prime minister, Yitzhak Rabin, whom he found quarrelsome and pessimistic about the prospects for peace. “It was like talking to a dead fish,” he recalled. Soon after that, Rabin was driven from office by a financial scandal, and Menachem Begin was elected in the most surprising upset in Israeli history.

Carter knew little about the new Israeli leader; nor did the CIA have much to offer. With rising alarm, Carter had watched Begin’s appearance on an American news show, during which he renounced the basis of all peace negotiations for the last decade, United Nations Resolution 242. Whenever a questioner referred to territories that Israel had occupied in the Six-Day War, Begin adamantly corrected him by saying that the territories weren’t “occupied,” they were “liberated.” On the West Bank, he said, he intended to establish a Jewish majority. When asked if his position did not place him in direct conflict with Carter’s well-known views on a peaceful resolution to the Israeli-Palestinian dispute, Begin responded, “President Carter knows the Bible by heart, so he knows to whom this land by right belongs.”

THE PROFILES Carter was studying in Wyoming came from a meeting he had at the CIA a few weeks earlier. He had directed the analysts to answer a number of questions about Begin and Sadat:

What made them leaders? What was the original root of their ambition?

What were their goals?

What previous events had shaped their characters?

What were their religious beliefs? Were they sincere?

Who was important to them? What were their family relations?

How was their health?

What promises and obligations had they made?

How did they react under pressure?

What were their strengths and weaknesses?

What were their attitudes toward the U.S. and Carter personally?

What did they think of each other?

Whom did they trust, especially within their delegations?

The resulting profiles of Begin and Sadat drew sharply opposing portraits. Sadat was a visionary—bold, reckless, and willing to be flexible as long as he believed his overall goals were being achieved. He saw himself as a grand strategic thinker blazing like a comet through the skies of history. The CIA noted his penchant for publicity, terming it his “Barbara Walters Syndrome,” after the famous television personality, but by the time the profile was prepared for Carter that category had been upgraded to Sadat’s “Nobel Prize Complex.” Begin, on the other hand, was secretive, legalistic, and leery of radical change. History, for Begin, was a box full of tragedy; one shouldn’t expect to open it without remorse. When put under stress, Sadat drifted into generalities and Begin clung to minutiae. Clashes and misunderstandings were bound to occur. There was some doubt among the analysts preparing the dossiers whether two such opposing personalities should ever be put into the same room together. The two leaders seemed alike only in unpromising ways. Both men had blood on their hands. They had each spent long stretches in prison and in hiding and were deeply schooled in conspiracy. They were not the kind of men Carter had ever known before.

Carter believed he instinctively understood Sadat, however, even though they came from distant cultures. Part of their bond was the fact that they had both been farmers. As a boy, Carter had plowed the red clay of southwest Georgia behind a mule, feeling the damp cool of the freshly turned earth between his toes. He was struck by the observation that Jesus and Moses would have felt at home on a farm in the Deep South during the first part of the twentieth century. Around the globe but on the same meridian as Plains, Georgia, there is a village of mud huts in Egypt called Mit Abul Kum, where Sadat spent his early years. Farmers in the black alluvial soil of the Nile Delta irrigated their fields using an Archimedes screw, which the Greek sage reputedly invented when he visited Egypt in the third century BCE. One could see painted in the tombs of the pharaohs scenes of village life that were still being lived three thousand years later.

Changelessness is the essential feature of such rural childhoods—a feeling of being cocooned, at once protected and entrapped. And yet, even as a child, a dark-skinned peasant from a small village in the Nile Delta, Sadat sensed his unique role in Egyptian society. Once, when he was playing with some other children near an irrigation canal, they jumped into the water and Anwar leaped in after them. Only then did he remember that he couldn’t swim. He thought, “If I drown, Egypt will have lost Anwar Sadat!”

Although he rarely talked about his race, Sadat was only two generations away from slavery—his maternal grandfather, an African man called Kheirallah, had been brought as a slave to Egypt and was emancipated only after the British occupiers demanded the practice be abolished. Kheirallah’s daughter, Sitt el-Barrein (woman of two banks), was also a black African. She was chosen as a wife for Mohamed el-Sadaty, an interpreter for a British medical group.1 She covered herself in traditional black clothing, with long sleeves and a skirt that reached the floor. She was Mohamed’s sixth wife; the first five bore him no children, so he divorced them one after another. Sitt el-Barrein would bear him three sons and a daughter. Anwar was her second child.

The racial dynamics in the Sadaty family were highly charged, as they were in Egyptian society as a whole. Mohamed el-Sadaty’s mother, called by custom Umm Mohamed (mother of Mohamed), was an overbearing figure who had arranged the match with Sitt el-Barrein. It’s a bit of a mystery why she made such a choice, since Umm Mohamed was of Turkish lineage, with fair features, and she despised her dark-skinned daughter-in-law. Mohamed inherited his mother’s Turkish features; he had blue eyes and blond hair. In Islam, a man is permitted four wives at a time, and Mohamed would eventually marry twice more when the family moved to Cairo. In addition to his three wives and his formidable mother, Mohamed’s vast household grew to thirteen children. Sitt el-Barrein occupied the lowliest place because of her race. She was little more than a maid, occasionally beaten by her husband in front of her children. Sadat rarely spoke of her.

It was his grandmother, Umm Mohamed, the strongest figure in the family, who made the biggest impression on Sadat. “How I loved that woman!” he recalls in his autobiography. She was illiterate, but she insisted that her children and grandchildren become educated. Anwar often spent summers in Umm Mohamed’s mud-walled hut in Mit Abul Kum, where her influence was unequivocal. From an early age he began to imagine himself as a figure of destiny, his imagination fired by the stories his grandmother would tell.

His favorite was the legend of Zahran. It is a tale of martyrdom. In June 1906, several years before Anwar was born, a party of British soldiers was pigeon hunting in a nearby village called Denshawi. They shot some domesticated fowl, infuriating the villagers. Total chaos followed. One of the soldiers accidentally shot and wounded the wife of the local imam. The villagers responded with a hail of stones. The soldiers fired into the mob, injuring five people. A local silo caught on fire, perhaps because of a stray bullet. Two soldiers raced back to camp to get help, but the other members of the hunting party surrendered to the villagers. One soldier who escaped died of sunstroke in the intense heat, although he may also have suffered a concussion from the stoning. British soldiers who came to the rescue killed an elderly peasant who was trying to assist the dying man, wrongly assuming that he had murdered their comrade. The British occupiers decided to make an example of Denshawi. Fifty-two villagers were rounded up and quickly brought before a tribunal. Most of the villagers were flogged or sentenced to long prison sentences. Four were hanged.

This confused and tragic incident marked a turning point in the British occupation, inflaming nationalist sentiments in Egypt and stirring outrage even in Great Britain. Denshawi became a byword for the inevitable clumsy by-products of imperialism. No one embodied the face of Denshawi more than the young man named Zahran, the first of the condemned to be hanged. According to the oral ballad that Sadat’s grandmother told to him, Zahran was the son of a dark mother and a father of mixed blood—just like Anwar. “The ballad dwells on Zahran’s courage and doggedness in the battle, how he walked with his head high to the scaffold, feeling proud that he had stood up to the aggressors and killed one of them,” Sadat writes. He heard this legend night after night, and it worked its way deep into his imagination. “I often saw Zahran,” he writes, “and lived his heroism in dream and reverie—I wished I were Zahran.”

It was in Cairo that Anwar first actually encountered the hated occupiers. He recalls “the odious sight of the typical British constable on his motorcycle, tearing through the city streets day and night like a madman—with a tomato-colored complexion, bulging eyes, and an open mouth—looking like an idiot, with his huge head covered in a long crimson fez reaching down to his ears. Everybody feared him. I simply hated the sight of him.”

In 1931, when Anwar was twelve, Mahatma Gandhi passed through the Suez Canal on his way to London to negotiate the fate of India. The ship stopped in Port Said, whereupon Egyptian journalists besieged the ascetic leader. The correspondent for Al-Ahram marveled that Gandhi was wearing “nothing but a scrap of cloth worth five piasters, wire rim glasses worth three piasters and the simplest thong sandals worth a mere two piasters. These ten piasters of clothing tell Great Britain volumes.” The example of this poor, dark-skinned man who turned the empire upside-down made a deep impression on the young Sadat. “I began to imitate him,” he writes. “I took off all my clothes, covered myself from the waist down with an apron, made myself a spindle, and withdrew to a solitary nook on the roof of our house in Cairo. I stayed there for a few days until my father persuaded me to give it up. What I was doing would not, he argued, benefit me or Egypt; on the contrary, it would certainly have given me pneumonia.” Sadat’s obsession with great men must have seemed comical, especially when he imitated Gandhi by sitting under a tree, pretending he didn’t want to eat, or dressing in an apron and leading a goat. He was consciously shopping for the qualities of greatness, trying on attributes and opinions. It wasn’t just Gandhi’s asceticism that appealed to him; he was drawn to the autocratic side of Gandhi’s nature, which favored action over deliberation and cared nothing for consensus.

Despite Sadat’s hatred of the British, it was through an English doctor who knew Sadat’s father that he was able to enter the Royal Military Academy. Sadat was rescued from the menial destiny he had been born to. The academy had been the exclusive province of the Egyptian aristocracy until 1936, when the British allowed the Egyptian Army to expand. During this period, Sadat read books on the Turkish Revolution and became increasingly devoted to Kemal Atatürk, the creator of modern Turkey. Sadat was already beginning to see himself as a transformational figure whose iron will would rearrange his society into a new paradigm. In that way, he and Begin were much alike.

Paradoxically, those were the same qualities that drew him to Hitler. “I was in our village for the summer vacation when Hitler marched forth from Munich to Berlin, to wipe out the consequences of Germany’s defeat in World War I and rebuild his country,” Sadat recounts. “I gathered my friends and told them we ought to follow Hitler’s example by marching forth from Mit Abul Kum to Cairo. I was twelve. They laughed and ran away.” Two decades later, after Germany was in ruins and sixty million people were dead, Sadat and other prominent Egyptians were asked by a Cairo magazine to write a letter to Hitler as if he were still alive. “My Dear Hitler,” Sadat wrote,

I admire you from the bottom of my heart. Even if you appear to have been defeated, in reality you are the victor. You have succeeded in creating dissension between the old man Churchill and his allies, the sons of Satan.… Germany will be reborn in spite of the Western and Eastern powers.… You did some mistakes … but our faith in your nation has more than compensated for them. You must be proud to have become an immortal leader of Germany. We will not be surprised if you showed up anew in Germany or if a new Hitler should rise to replace you.

THE FACT THAT Sadat was black may have awakened protective and fraternal feelings in Carter. When Jimmy was four years old, his family had moved to the little hamlet of Archery, two miles west of Plains. They were the only whites in a community of fifty-five black families. Jimmy’s main playmates were the sons of these black tenant farmers; in fact, his dialect at the time was indistinguishable from theirs. Jimmy and his best friend, Alonzo Davis, would occasionally be given the chance to ride the train to the nearby town of Americus to watch a movie together, although they had to separate into the “white” and “colored” sections both on the train and in the theater. At the time, Carter simply accepted such practices as natural features of a society in which whites were the owners and blacks the renters.

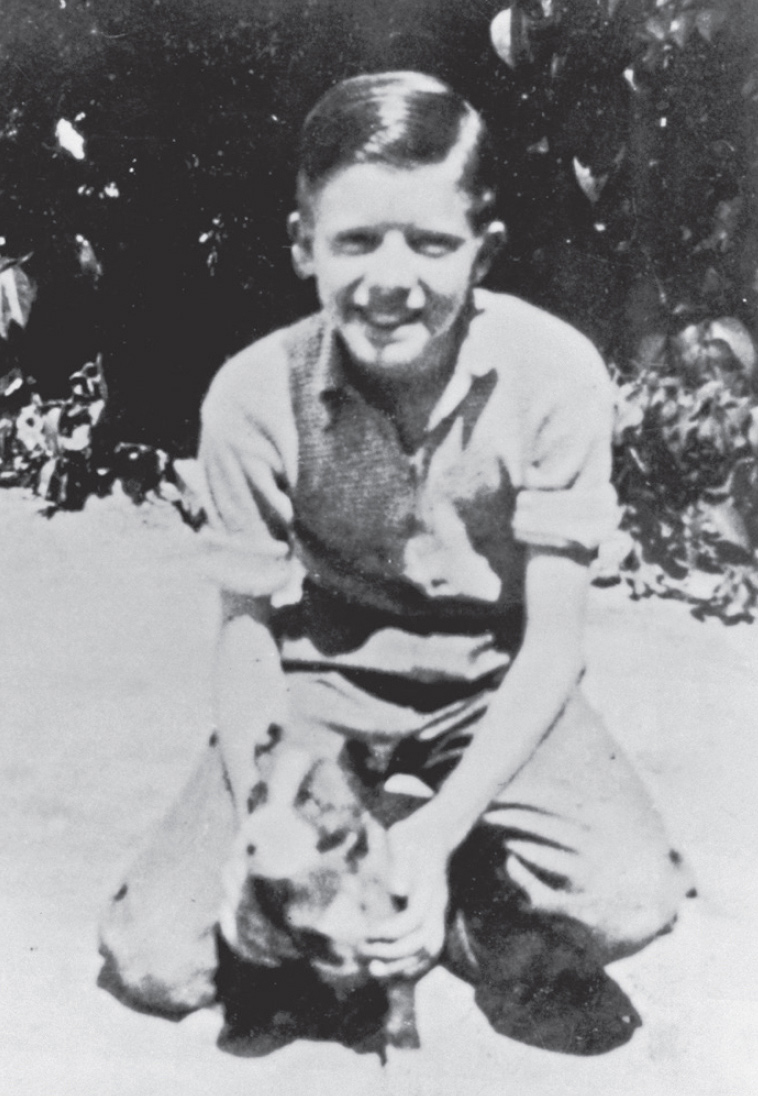

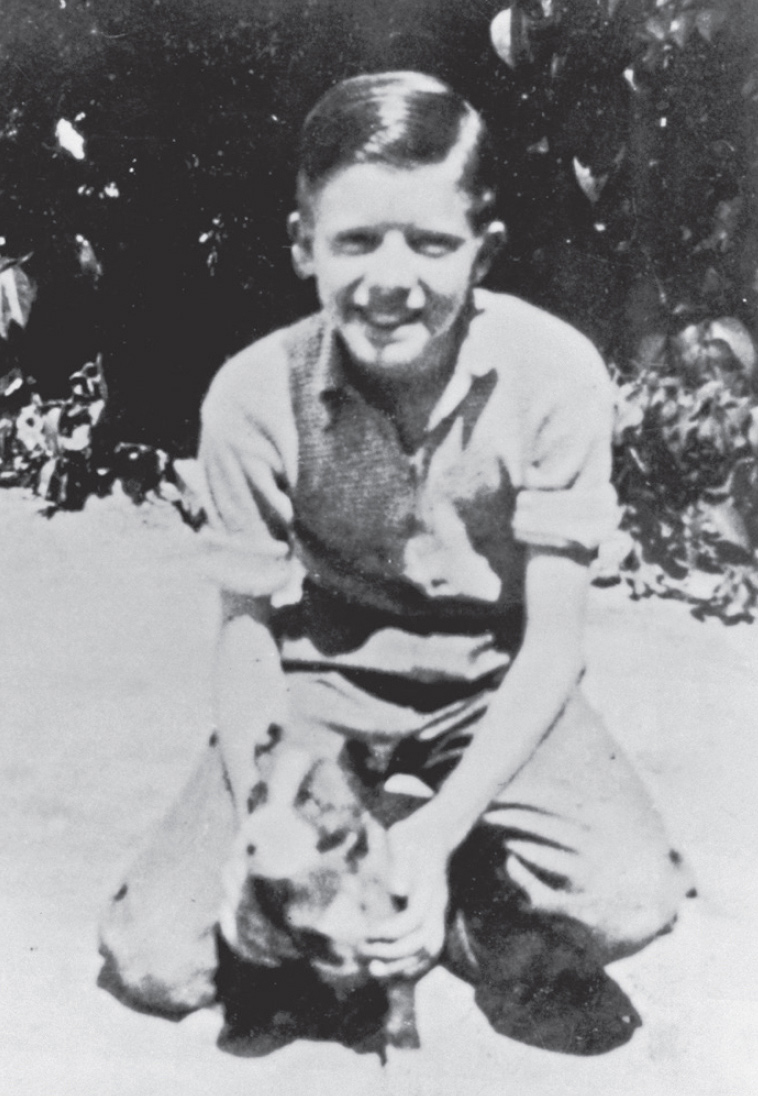

Jimmy Carter with his dog, Bozo, 1937

From the age of five Jimmy began selling peanuts that he picked, boiled, and bagged himself, then carried in a wagon to downtown Plains, where he sold them to the disabled veterans and loafers who played checkers in front of the livery stable. In 1932, at the peak of the Great Depression, the price of cotton plummeted to five cents a pound. By then, Jimmy, age eight, had accumulated enough savings from peanut sales to buy five bales for twenty-five dollars each; then, when cotton went back up to eighteen cents several years later, he sold the cotton and bought five tenant houses, which he rented by the month, joining the landlord class while still a child. It was about this time that two of his black friends opened a gate and then stood back and let Jimmy pass through. He thought it must be a trick they were playing, but this symbolic action signaled a powerful social change. “The constant struggle for leadership among our small group was resolved, but a precious sense of equality had gone out of our personal relationship,” Carter writes, “and things were never again the same between them and me.”

Religion was the elixir that both Carter and Sadat drank in excess. Sadat had gone to the Islamic school in his village, where he memorized the Quran as a young child. Later, he sported the dark callus on his forehead that is the imprint of endless hours of prayerful prostration. This was well before such outward displays of religious zeal were fashionable in cosmopolitan Cairo. He called himself the “Believer President.” Although Carter didn’t advertise it, that’s how people thought of him as well. He had begun memorizing Bible verses at the age of three and publicly declared his faith at a revival meeting when he was eleven. He was baptized into the Plains Baptist Church, where the pastor, Royall Callaway, preached that the Jews would soon return to Palestine and bring on the return of Christ and the rapture of true Christians into Heaven—a doctrine known as premillennialism.

As with Sadat, the military had also provided a means of escape for Jimmy Carter. He had an uncle in the Navy whom he idolized, and he spent his entire childhood obsessed with the goal of entering the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland. That would require a congressional appointment. Carter’s father continually lobbied their local congressman, but it wasn’t until two years after Jimmy graduated from high school that the precious appointment came through. Carter started teaching Sunday school as an eighteen-year-old midshipman at Annapolis, a practice he would continue for the rest of his life. Even on submarines, he held services in the cramped spaces between torpedoes.

Because of his southern background, Carter’s classmates at Annapolis made assumptions about his racial attitudes. And yet when the academy finally admitted a black cadet, Wesley Brown, Carter shielded him from the harassment and bigotry that was the fate of so many civil rights pioneers. Carter was called a “nigger lover” and treated, as another classmate reacalled, “as if he was a traitor.”

In 1949, Carter studied nuclear physics and reactor technology at Union College in Schenectady, New York. Admiral Hyman Rickover, known as the “Father of the Nuclear Navy,” had chosen him to be the chief officer of the USS Seawolf, one of two nuclear submarine prototypes under development. Rickover was—like Menachem Begin—a Polish Jew, as renowned for his impatience as he was for his intelligence. At their first meeting, Rickover offered Carter the opportunity to talk about any subject he chose. Carter was a relentless autodidact, but with each topic he brought up—current events, literature, electronics, gunnery, tactics, seamanship—Rickover would ask a series of questions of increasing difficulty, showing his own superior knowledge of the subject. When Carter discussed classical music, for instance, Rickover dissected nuances of particular pieces that Carter said he admired, such as “Liebestod” from Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde. Throughout the interview, an unsmiling Rickover stared directly into Carter’s eyes. His goal was to see how an applicant behaved under pressure. By the end, Carter was soaking in sweat and humiliation.

Finally, Rickover asked how Carter ranked in his class at the Naval Academy. “Sir, I stood 59th in a class of 820!” Carter said proudly.

“Did you do your best?” Rickover asked.

Carter started to answer in the affirmative, but then he gulped and admitted that he had not always done his best.

Rickover just stared at him, and then turned his chair away, ending the interview. “Why not?” he asked in parting.

Carter was unable to answer. He sat quietly for a moment, shaken by the frankness of the question and the cool dismissal, then he stood and left the room. “He would ask me questions until he proved that I didn’t know anything about anything,” Carter complained to Rosalynn afterward. She would note that, years later, when Carter was governor, he would still break into a cold sweat if he was told that Admiral Rickover was on the line.

As one of Rickover’s protégés, Carter was on track toward a significant military career. But in 1953, Carter’s father was diagnosed with cancer and Jimmy went home to say good-bye. He had been away for eleven years. He was deeply moved by the procession of hundreds of people who came to pay tribute to Mr. Earl as he lay on his deathbed, so many of whom had been aided by his quiet charity over the years. Even though Carter had a secure job with an important future, it seemed to him that his own life would never be so meaningful as the one his father had lived in this small community. There was the additional fact that no one else in the family could take over the farm and the peanut warehouse business that his father had built. Jimmy’s younger brother, Billy, was still in high school, and harvest season would soon begin. As he mulled his decision, Carter concluded, “God did not intend for me to spend my life working on instruments of destruction to kill people.” He resigned his commission and returned to Plains.

Southwest Georgia was Ku Klux Klan country, and Carter became a target because of his progressive views. He was not an activist, but he was the only white man in Sumter County who refused to join the White Citizens’ Council, a segregationist organization that held Dixie in its thrall. His business was boycotted. When he ran for governor the first time, in 1966, he hoped that Georgia was ready to step away from its racist past. He lost to Lester Maddox, who made his reputation by chasing black customers out of his Atlanta restaurant with a pistol and an ax handle. Carter was despondent. “I could not believe that God, or the Georgia voters, would let this person beat me and become the governor of our state,” he lamented. His loss to Maddox prompted a crisis in his lifelong faith. His sister, Ruth Carter Stapleton, an author and evangelist, had a talk with him. She quoted some scripture from the Epistle of James that advised believers to take joy in their failures because they can lead to wisdom. Carter wasn’t ready to hear her advice at the time, but he would later say it was a turning point—what was referred to as his “born again” experience. He announced for governor once more, this time determined to do whatever it took to win.

Race was still the most dangerous subject to navigate in Georgia. Carter defined himself in the 1970 campaign as a populist and a friend of the workingman, appealing to the same constituency that Maddox and other demagogues in Georgia had cultivated. At times he signaled that he was close to Alabama governor George Wallace and other prominent segregationists, even borrowing Wallace’s slogan, “our kind of man,” to wink at the racists in the crowd. He went so far as to endorse Lester Maddox, who could not succeed himself and was running for lieutenant governor, calling him “the embodiment of the Democratic Party.” There was a photograph of Carter’s chief opponent in the Democratic primary, Carl Sanders, standing next to black members of the Atlanta Hawks basketball team (which he partly owned), who were pouring champagne over his head. Atlanta reporters said that staffers in the Carter campaign mailed leaflets with the photograph to white barbershops and churches around the state and even passed them out at Klan rallies. Although Carter himself was not linked to these activities, because he was a south Georgia peanut farmer, it was already assumed that he must be a racist and a plantation owner. “I am not a land baron,” Carter was finally forced to declare. “I do not have slaves on my farm in Plains.”

One of Carter’s main supporters was a wealthy Iranian Jew from Savannah named David Rabhan. He had a shaky business empire that ranged from catfish farms to nursing homes. Tall and muscular, with a shaved head, and typically attired in a blue jumpsuit and sneakers, Rabhan was an author, sculptor, and gourmet cook. He was also a pilot, and during the campaign he flew Carter back and forth across the state in his twin-engine Cessna. They spent so much time together in the air that Carter learned to fly the plane while Rabhan napped.

Rabhan was a liberal, especially on race. He had been marked as a child by seeing the body of a black man who had been murdered by whites; as an adult, he cultivated friendships with some of the most important figures in Atlanta’s influential black community. He quietly introduced Carter to this crowd, along with black preachers and funeral directors throughout the state. Those meetings were kept secret so they would not destroy Carter’s chances. Black voters in the know were able to imagine that Carter was a closet progressive, in the same way that white racists assumed that he was one of them.

On one of the final days of the campaign, as the two men were flying from the Georgia coast across the state, Carter took the controls as Rabhan closed his eyes. They were flying at eight thousand feet when both engines sputtered and died. Carter panicked. He punched Rabhan, who didn’t stir. Then he hit him hard. “What’s the matter?” Rabhan asked.

“We’re out of gas!”

In that case, Rabhan said, they were going to crash.

Rabhan let that sink in, then he turned a valve and opened up the spare gas tank. The engines coughed back to life.

Very few people get away with teasing Jimmy Carter.

After Carter cooled off, he observed that Rabhan had done so much for him. “This is the end of the campaign,” he said. “I think I’ve got a good chance to win. Is there anything I can do for you?”

“No, I don’t need your help as governor,” Rabhan replied. “What I’d like you to do is tell the Georgia people what you think about the millstone of racism that has oppressed our state.”

Carter picked up an old flight map. On the back he wrote, “I know this state as well as anyone. I say to you quite frankly that the time for racial discrimination is over.” He handed it to Rabhan. “If I’m elected, in my inaugural speech I will make this statement.”

“Sign it,” Rabhan demanded.

That declaration from the Georgia governor’s mansion on January 12, 1971, put Carter on the cover of Time magazine and planted the seed of his presidential candidacy.

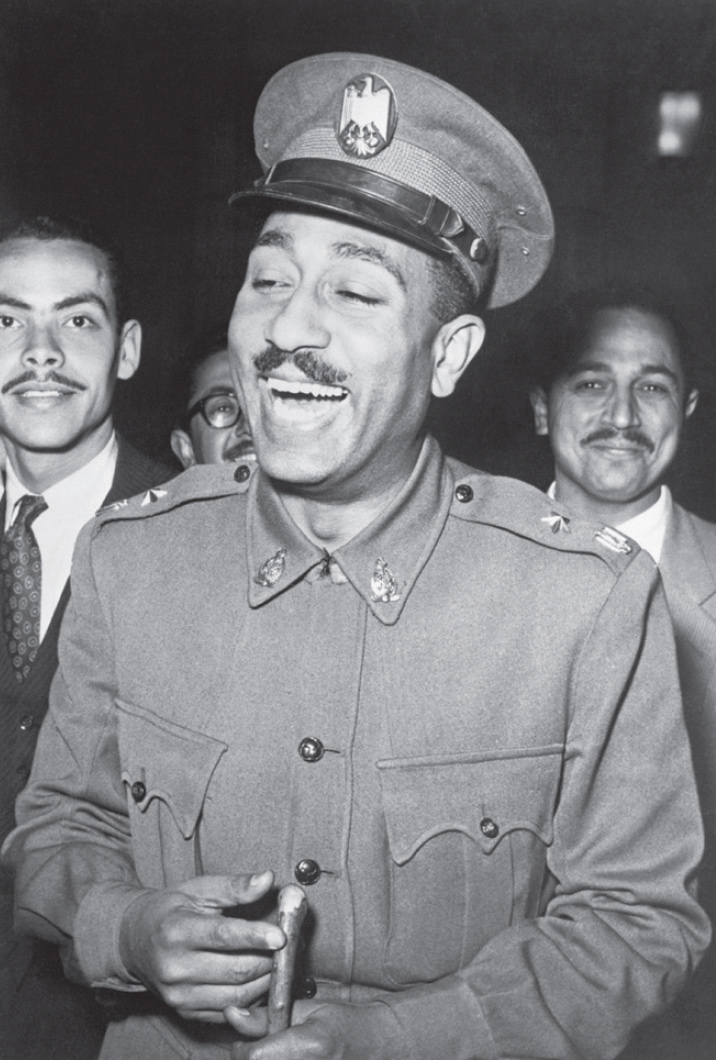

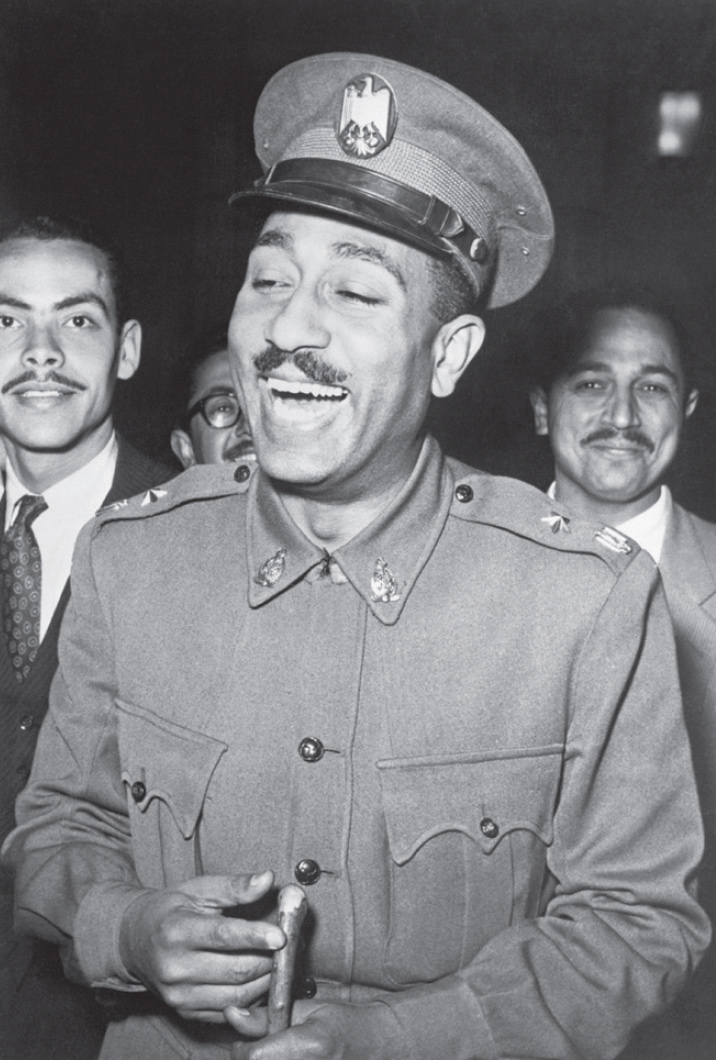

THE AMERICAN INTELLIGENCE COMMUNITY had scarcely noticed Anwar Sadat in his early political career. Then, he was obscured by the giant shadow of Gamal Abdel Nasser, the charismatic architect of the Egyptian revolution. When Nasser died of a heart attack in 1970, Vice President Sadat was universally seen as a placeholder until the next strongman pushed him aside. Instead, he proved to be a master of the unexpected. First, he stunned Egypt by rounding up Nasser’s corrupt cronies, who controlled the main positions of government power, and throwing them in jail. In 1972, he expelled fifteen thousand Soviet troops and military advisers from Egypt. Until that point, Egypt had been essentially a Soviet military base, Russia’s main foothold in the Middle East. There was as much puzzlement as joy in Washington, which had been caught by complete surprise. The Israelis were convinced that without the Russians the Egyptians were incapable of waging war. The very next year, on Yom Kippur, Sadat sent his army across the Suez Canal, catching the Israelis off guard and bringing the superpowers to the point of a nuclear showdown. By then, the mercurial Egyptian leader had become an object of obsession among American policy makers and intelligence analysts.

With all the surprises that Sadat had pulled out of his hat, none equaled the moment, on November 9, 1977, when he set aside the prepared text of a long-winded speech he was making to the Egyptian People’s Assembly and announced, “I am ready to travel to the ends of the earth if this will in any way protect an Egyptian boy, soldier, or officer from being killed or wounded.… Israel will be surprised to hear me say that I am willing to go to their parliament, the Knesset itself, and debate with them.” Few believed it. The Egyptian parliamentarians routinely cheered; even Yasser Arafat, the head of the Palestinian Liberation Organization, who was present as a guest, dutifully applauded. Cairo newspapers omitted the statement the next morning. Everyone thought it was an empty gesture.

Ten days later Sadat’s plane took off for Ben Gurion Airport. He now held the world spellbound. Israel was in a state of confused delirium because of the visit, the first in Israel’s history by any Arab leader. Ten thousand soldiers, police, and security personnel were waiting to guard the Egyptian president, in addition to the 2,500 foreign journalists who had rushed to cover the historic event. At eight thirty p.m., two hours after the end of Shabbat, searchlights picked up the white plane against the black sky, flying low and circling over Tel Aviv. Egyptian flags of red, white, and black intermingled with the blue and white of Israel, even though the two countries were still in a state of war. Without sheet music for the Egyptian national anthem, the Israeli military orchestra had learned how to play it by listening to Cairo radio. Sharpshooters were stationed on the rooftops of the terminal buildings in case terrorists suddenly emerged from the presidential plane rather than Sadat himself. But then there he was.

Anwar Sadat being greeted by Menachem Begin upon arrival in Jerusalem, 1977

Sadat’s enemies were waiting on the tarmac, and he walked among them, joking with the generals and the cabinet officers, greeting Menachem Begin and former Israeli leaders.

“Madame, I’ve waited a long time to meet you,” Sadat said as he kissed Golda Meir.

“We’ve been expecting you,” she said.

“And now I’m here.”

He joked with Ariel Sharon, perhaps the greatest field commander in Israel’s history, saying that the next time he crossed the canal he would have him arrested. “Oh, no, sir,” Sharon replied. “Now I’m just the minister of agriculture.”

By presenting himself to Israel, Sadat was introducing two cultures that were almost entirely unknown to one another. Few Israelis had ever met an Egyptian, except for the Jews who had emigrated from there, so the shock of having Sadat himself in their midst was compounded by curiosity and wonder. The same was true for the Egyptians watching the event on television. To see Sadat staring into the faces of the enemy—until now, figures of legend—suddenly and unsettlingly humanized the Israelis in the Egyptian mind. Sadat was convinced that 70 percent of the conflict between Israel and the Arabs was psychological; if he could make peace seem real and available, not only to the Israelis but also to the Arabs, most of the work would be done. Then, perhaps, there would be a chance for the prosperity that Egyptians desperately needed but which wars had chronically destroyed.

Sadat’s decision to go to Israel shattered the taboo against speaking to Israelis or even acknowledging the existence of a Jewish homeland. Both the foreign minister and the man Sadat had appointed to succeed him had resigned, protesting that Egypt would now be isolated in the Arab world. Sadat compounded the insult by timing his arrival for the eve of Eid al-Adha, one of the main holy days in Islam. On that day, the king of Saudi Arabia goes to unlock the door of the Kaaba, the cubical stone building in Mecca where all Muslims direct their prayers. “I have always before gone to the Kaaba to pray for somebody, never to pray against anyone,” King Khalid said. “But on this occasion I found myself saying, ‘Oh God, grant that the airplane taking Sadat to Jerusalem may crash before it gets there, so that he may not become a scandal for all of us.’ ”

As the presidential motorcade climbed through the rocky hillsides toward Jerusalem, crowds along the highway sang “Hevenu Shalom Aleikhem” (“We’ve Brought Peace upon You”). The Israelis had no armored limousine for Sadat, so they had borrowed one from the American ambassador. All along the way people were openly weeping. Some wore T-shirts saying “All You Need Is Love.” The Egyptian entourage gaped at the scene; it was like being on another planet. The motorcade came to a halt at Jerusalem’s King David Hotel, which Begin’s irregulars had blown up during the British Mandate three decades before. A crowd of 250 people waited in the lobby crying out to Sadat. Across the street, the carillon at the YMCA played “Getting to Know You.”

JERUSALEM—the most contested piece of property in history—was the object of longing and worship for the three great Abrahamic religions and the source of centuries of bloodshed. Israel had seized East Jerusalem ten years before in the 1967 war, thrilling Christians and Jews all over the world and throwing Muslims into despair. Now, from their rooms at the King David, the Egyptian delegation had a magnificent view of the honeyed limestone walls of the Old City and the building cranes that rose like a giant forest around it. “All that construction!” one of the delegates said. “I fear that Jerusalem is lost to the Arabs.” Although Sadat himself seemed serenely untouched, the intermixed feelings of anxiety, hope, and dread among the Egyptians led to great stress and confusion. One of Sadat’s bodyguards actually died of a heart attack in the hotel. His corpse was smuggled into a cargo plane to keep rumors of assassination from taking root.

At the heart of the Old City stands the Temple Mount. According to Jewish tradition, it is where Adam was made from its dust, where Cain killed Abel, and where God’s spirit dwells. King Solomon was said to have built the First Temple on this spot a thousand years before the birth of Jesus in order to house the Ark of the Covenant, which contained the stone tablets with the Ten Commandments that God gave to Moses on Mount Sinai. The First Temple stood until 586 BCE, when the Babylonian ruler Nebuchadnezzar tore it down and herded the Jews into Babylon. Seventy years later the Jews were freed by the Persian ruler Cyrus the Great, and the Second Temple was established on the same spot. King Herod expanded it into one of the largest structures in the ancient world. It was here that Jesus drove out the money changers and the sellers of animals for sacrifice, saying, “Take these out of here, and stop making my Father’s house a marketplace.” The temple was sacked once again in 70 CE, by the Romans, following the Jewish revolt against the empire.

In 1099, the Crusaders arrived in Jerusalem and killed everybody in town. Jews were rounded up and slaughtered in their synagogues. One witness describes Christian knights riding through a lake of blood after slaying ten thousand Muslims who had taken refuge on the Temple Mount. Control of the city passed back and forth between Christians and Muslims until the twelfth century, when Saladin peacefully recaptured the city and allowed each religion the right to worship in its holy places—an example that would prove difficult for his successors to follow. The Ottomans seized Jerusalem in 1517, and maintained control for four hundred years, until the British expelled the Turks and their German advisers at the end of the First World War. By that time, Jerusalem had been reduced to a pestilential town of 55,000 starving souls, overrun with prostitutes and venereal diseases. Conscious of the precedent, the victorious general, Sir Edmund Allenby, entered the city on foot, rather than in a martial display. As he received the keys to the city, Allenby declared, “The Crusades have now ended.” But even then, the British and the French were carving up the Ottoman Empire among themselves. At this imperial feast, the Zionist campaign in Europe succeeded in getting the support of the British to gain a homeland for the Jews in Palestine. A bloody new era was born.

Muslims call the Temple Mount Haram al-Sharif, the Noble Sanctuary. According to the Quran, this is where Abraham demonstrated his faithfulness to God by offering up his son Ishmael. (Christians and Jews believe that Abraham’s son Isaac, father of the Jews, was the intended sacrificial victim.) Two mosques now stand atop the mount where the Jewish temples once had been.

The day after Sadat arrived in Jerusalem was the feast of Eid al-Adha, which commemorates God’s mercy in sparing Isaac. Stalked by television cameras and helicopters, Sadat entered the silver-domed Al-Aqsa Mosque for dawn prayers. His presence in this sacred space sent electrifying currents throughout the Muslim world, alternately of hope and betrayal. On the one hand, the loss of Jerusalem was symbolically greater than that of Sinai and the entire West Bank, and the fact that the city’s future was once again on the bargaining table was almost unbearably thrilling; on the other hand, the mere fact that Sadat was dealing with the occupiers stoked fear and paranoia. This was the same mosque where, in 1951, a Palestinian tailor assassinated King Abdullah I of Jordan because he had dared to negotiate with the Israelis. The bullet holes were still visible in the alabaster columns. As Sadat worshipped, Palestinian protesters outside the mosque loudly denounced him for the same crime.

Sadat moved on to the seventh-century Dome of the Rock, the oldest building in Islam, a magnificent eight-sided structure with ornate porcelain mosaics and a golden cupola that dominates the Old City. It is a resonant icon of Islamic spirituality as well as the ubiquitous political emblem of the Palestinians’ yearning for restitution. The shrine encloses the rocky outcropping that is the summit of the Temple Mount. According to Jewish tradition, the stone is the perch that God made for himself when he created the universe. Muslims believe that the Prophet Muhammad made his night journey to heaven atop his steed, al-Buraq, from this rock. At the End of Days, according to Islamic tradition, the Final Judgment will take place in this sanctuary, with the blessed and the damned going their separate ways for eternity.

Sadat made his way into the Old City at the base of the Temple Mount, stopping at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. A monk showed him the stone where the body of the crucified Jesus was said to have been washed and the tomb where he was buried. Outside, demonstrators were beginning to break through the ranks of security. “Sadat, what do you want from us?” Palestinians cried as he left. “We are against you. We don’t want you here.”

Afterward, Sadat laid a wreath at a memorial for Israeli soldiers killed in all the wars since the founding of the state. Then he joined Begin at the Yad Vashem Holocaust Memorial. Sadat was handed a skullcap. “It’s a kippah,” Begin explained. “It’s our custom to cover our heads during prayers or when entering a house of prayer.”

Sadat silently moved through the somber memorial, with the tools of genocide starkly displayed. There was the gate to Auschwitz, with its grotesquely ironic motto, Arbeit macht frei (Work makes you free), through which more than a million Jews passed on their way to death. The Hall of Names contained brief biographies of two million of the six million Jews who perished in the Holocaust. In the middle of the room there was a great cone lined with images of the victims; it rose skyward like the smokestacks of the death camps. “All this befell us because we had no state of our own,” Begin told Sadat.

Begin’s own parents, Ze’ev Dov and Chasia, as well as his older brother, Herzl, were among the names in this grim repository. On July 22, 1942, the Nazis captured his hometown of Brisk2 and began their systematic annihilation of all Polish Jews. Ze’ev Dov had been attempting to emigrate to Palestine when the Nazis arrived, but Chasia was in the hospital with pneumonia. The Germans murdered her in her bed, along with the other patients. Five thousand Jews from Brisk, including Ze’ev Dov and Herzl, were rounded up. Some were shot and thrown into a pit; Ze’ev Dov was weighted down with rocks and drowned in the River Bug. Menachem learned that his father’s final words were to curse his executioners: “A day of retribution will come upon you too!”

“May God guide our steps toward peace,” Sadat wrote in the guest book. “Let us put an end to all the suffering for mankind.”

SADAT, master of the bold gesture, was indifferent to trifling details, but his confounded Israeli hosts were obsessed with the fine print. What did Sadat want in exchange for this stunning overture? Did he expect Sinai? Some concession on the West Bank or Gaza? They kept trying to pin Sadat down, but he was maddeningly evasive. “We have to concentrate on the heart of the issue, not on technicalities and formalities,” he declared. He wanted to arrive at an “agreed program”—a statement of principles in which Israel would pledge to withdraw from the occupied territories and come to a solution on the Palestinian question. But exactly what did that mean? All the occupied territories, or was that negotiable? What “solution” was there to the plight of the Palestinians? “Every side wants to deal with details,” Begin insisted, “not only general declarations.” The Israelis were so busy trying to read the nuances of Sadat’s language that they were blind to the fact that Sadat’s presence in Jerusalem was the message itself.

Part of the Israeli dilemma was that they had never really confronted what they themselves wanted. Perpetual conflict had pushed the issue of permanent borders into some distant future, but the rude prospect of actual peace demanded immediate choices. What was peace worth to them? Swollen with territories seized in 1948 and 1967, Israel now stretched all the way from the hills of southern Lebanon to the Red Sea, and from the River Jordan to the Mediterranean. All this space provided strategic depth, something Israel had never had before. Sinai had been a historic concourse for attacking armies; the Golan Heights had been the dominating redoubt for Syrian artillery; the West Bank was a hideout for terrorists. Why surrender any of it? Would peace replace the security that Israel gained from having these territories under military control?

There was also something deeply appealing about the largeness of the space the occupation afforded; aesthetically, Israel looked properly filled out. Before the occupation of the West Bank, the country had appeared almost bitten in half. The little fishing village of Sharm el-Sheikh, strategically located at the southernmost tip of the peninsula at the juncture of the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aqaba, had been turned into an Israeli resort town, with classy hotels and dive shops. Radio stations in Tel Aviv regularly gave weather reports for the Red Sea beaches. Israelis had settled into a comfortable feeling of ownership over all this real estate, even if the threat of war never quite disappeared. Moreover, Sinai had oil, which resource-poor Israel was helping itself to. And finally, there was the issue of Jerusalem, the object and focus of Jewish prayers for millennia. Was peace really worth surrendering any of these precious properties?

After lunch, Sadat journeyed to the Knesset to make his speech. The eerie and unprecedented moment of his entrance was heralded by bugle calls. For the first time in the institution’s history, members of the Knesset were permitted to applaud—although not everyone did so. A psychological wall still stood between them, which Sadat meant to obliterate. Even his bitterest foes recognized that Sadat had placed his life dangerously on the line. He had made it harder for the two peoples to hate each other, and the loss of that luxurious emotion on both sides stirred up feelings of murderous rage against him.

“Ladies and gentlemen, there are moments in the life of nations and peoples when it is incumbent on those known for their wisdom and clarity of vision to overlook the past, with all its complexities and weighing memories, in a bold drive towards new horizons,” Sadat began. He spoke words that no Arab leader had ever said before—words many in the audience never imagined they would hear. “You want to live with us in this part of the world. In all sincerity, I tell you, we welcome you among us, with full security and safety,” Sadat declared. “We used to reject you,” he admitted. “We had our reasons and our claims, yes. We used to brand you as ‘so-called’ Israel, yes. We were together in international conferences and organizations and our representatives did not, and still do not, exchange greetings, yes. This has happened and is still happening.”

Then his tone sharpened. “Frankness makes it incumbent upon me to tell you the following,” he said. “I have not come here for a separate agreement between Egypt and Israel.” Many in the room, including Begin, hoped to set the Palestinian issue aside; in fact, Sadat himself had occasionally seemed ambivalent on the subject, but now he was adamant. “Let me tell you without the slightest hesitation that I have not come to you under this dome to make a request that your troops evacuate the occupied territories. Complete withdrawal from the Arab territories occupied after 1967 is a logical and undisputed necessity. Nobody should plead for that.” He went on: “Peace cannot be worth its name unless it is based on justice, and not on the occupation of the land of others. It would not be appropriate for you to demand for yourselves what you deny others.… You have to give up, once and for all, the dreams of conquests, and give up the belief that force is the best method for dealing with the Arabs.”

Sadat promised that Israel could live safely and securely among her Arab neighbors, under certain conditions. “Any talk about permanent peace based on justice, and any move to ensure our coexistence in peace and security in this part of the world, would become meaningless, while you occupy Arab territories by force of arms,” he said, adding, “We insist on complete withdrawal from these territories, including Arab Jerusalem.”

The mood in the Knesset, which had been so buoyant, quickly deflated. The parliamentarians settled in for what now seemed very familiar Arab demands, although no other leader had ever offered real peace in the bargain. “It is no use to refrain from recognizing the Palestinian people and their rights to statehood and rights of return,” Sadat continued, mopping his gleaming forehead in the stiflingly hot room. “If you have found the legal and moral justification to set up a national home on a land that did not all belong to you, it is incumbent upon you to show understanding of the insistence of the people of Palestine on establishing, once again, a state on their land.” Ezer Weizman, the minister of defense, scribbled a note: “We have to prepare for war.” Begin took it and nodded.

It was a strange performance. When has it ever happened that the defeated party—defeated in four wars, in fact—has entered the enemy capital to lay down the terms of peace? When Sadat finished, Begin did not applaud.

Although Begin was well known for his oratory in this chamber, his response was improvised and full of rebuke. The sense of grievance was never far from his lips under any circumstances, and in the curious role reversal that was being played out in this encounter, Begin did not offer his own terms of peace; instead, he defended Israel’s right to exist at all. “No sir, we took no foreign land,” he exclaimed. “We returned to our homeland. The bond between our people and this land is eternal. It was created at the dawn of human history.… Here we became a nation. And when we were exiled from our land because of the force that was applied against us, and when we were thrust far from our land, we never forgot this land, even for one day. We prayed for her. We longed for her.” He mentioned Sadat’s trip to the Holocaust museum earlier in the day. “With your own eyes you saw what the fate of our people was when this homeland was taken from it,” he said. “No one came to our rescue, not from the East and not from the West. And therefore we, this entire generation, the generation of Holocaust and resurrection, swore an oath of allegiance: never again shall we endanger our people.”

Peace had seemed so close at hand when Sadat’s plane had landed in Israel, but when he left it was still very far away.

CARTER HAD MET Begin when he came to Washington in July 1977, only a month after the Israeli had taken office. Carter immediately recognized the man’s formidable intellect—“His IQ is probably as high as anybody I’ve ever met,” he noted—as well as his biblical knowledge, which Carter hoped would help them find common ground. On the other hand, he was shocked by Begin’s arrogance and evident indifference to the effort that the president of the United States was putting into making peace in the Middle East. In Carter’s opinion, Begin made it clear from the beginning that “he wasn’t going to do a damn thing.”

Begin was slightly built, with a large balding head and a long chin, which gave his head something of the shape of a light bulb. Behind glasses with heavy frames, his eyes were blue-gray; the thinning strands of hair that remained were reddish brown. When he smiled, he exposed a prominent gap in his front teeth. His disinterest in fashion had become a trademark, but on the other hand he was elaborately formal by nature and addicted to ceremonies. Dignity was an obsession with him. His stiff-necked code of honor and rococo manners encouraged caricature and ridicule among his opponents. “Begin is absolutely convinced that he holds the truth in his back pocket,” Ezer Weizman observed. “Consequently, in addressing others—including the heads of great nations—he adopts the manner of a teacher talking to his pupils. There is something overbearing in his manner.” Views that did not correspond to his ironclad philosophy of life were rejected as naive or subversive. “Begin simply drives anyone who disagrees with him up the wall,” noted Samuel Lewis, the American ambassador to Israel. Lewis considered it merely one of Begin’s many tactics. “He exhibited a rich arsenal of tools: anger, sarcasm, bombast; exaggeration, wearying repetition of arguments, historical lessons from dark chapters of Jewish history; and stubbornness.”

The prime minister carried an emotional burden that was particularly acute for Holocaust survivors. “Against the eyes of every son of the nation appear and reappear the carriages of death,” he said in one of his despairing proclamations from the underground. “The Black Nights when the sound of an infernal screeching of wheels and the sighs of the condemned press in from afar and interrupt one’s slumber; to remind one of what happened to mother, father, brothers, to a son, a daughter, a People. In these inescapable moments every Jew in the country feels unwell because he is well. He asks himself: Is there not something treasonous in his own existence. He asks: Can he sit by and allow the terrible contradiction between the march to death there and the flow of life here.” He concluded: “And there is no way to run from these questions.”

In private, Begin was guarded and suffered frequent mood swings that would prompt him to retreat into his office and cancel meetings. The prime minister surrounded himself with aides who were little more than acolytes, most of them drawn from the underground, who humored him and dared not question his authority. He was by no means a skilled administrator. He had little understanding of the economy or international affairs beyond his region. In his entire career, he had one main political idea, which was to expand Israel’s borders. His attitude toward the Arabs who lived inside those borders was ambivalent. He devoutly believed that the State of Israel itself belonged entirely to the Jewish people; on the other hand, he suggested that if Israel annexed the territories it acquired through war, the country should award citizenship to every Arab who desired it.

He was not intensely religious. He went to temple mainly on the holidays. Still, he was totally absorbed by the tragic conundrum of Jewish history. Other countries could be multireligious, and other religions could be multinational, he believed, but with Jews there was only one nationality and a single religion, and neither could be separated from the other. His adviser and speechwriter, Yehuda Avner, recalled an evening of Bible study in Begin’s home, the night before he was flying to Washington. Begin proposed to discuss the text from Numbers 22–24. In the story, forty years had passed since the Jews fled Egypt, and their wandering in the wilderness was nearly at an end. The fearful Moabite King Balak attempted to bribe the prophet Balaam to curse the Israelites before they could enter the Promised Land, where the Moabites resided. Balaam refused. “How shall I curse, whom God has not cursed?” he tells the king, and then he adds, referring to the Israelites, “Lo, the people shall dwell alone, and shall not be reckoned among nations.”

“Is this not a startlingly accurate prophecy of our Jewish people’s experience in all history?” Begin asked the assembled guests. Why did Israel endure such solitude in the world? There were many Christian states, and Muslim states, and Buddhist states; there were many countries that spoke English, French, Arabic, and so on; but there was only one Jewish country in the world, and only one that spoke Hebrew. Israel stood alone. “Why have we no sovereign kith and kin anywhere in the world?” he asked. “No other country in the world shares our unique narrative.” The only bond Israel enjoyed with any other people was with fellow Jews in the Diaspora, “and everywhere they are a minority and nowhere do they enjoy any form of national or cultural autonomy.”

Begin started his first meeting with Carter in the White House with an overview of the modern history of Israel, recounting the attacks by Arabs on Jews in the 1948 War of Independence. “There were only 650,000 Jews [in Palestine] in those days, and we had to fight three armies, plus the Iraqis,” he said. “I am not exaggerating when I say that sometimes we had to fight with our bare hands and sometimes with homemade arms that didn’t always work. We lost one percent of our population in that war, 6,000 people.” Begin grew emotional as he spoke about the terror attacks on the part of the Palestinians. “The bloodshed has gone on permanently. My grandchild was bombed in Jerusalem.3

“In May of 1967, I remember being at the Independence Day parade when we got news of Egypt’s mobilization in Sinai,” Begin continued. “For two weeks we were surrounded by a ring of steel. There were more tanks facing us than those that Germany had sent against the Soviet Union in 1941. All of the Arab capitals were calling for our death, and wanting to throw us into the sea.” Faced with such a threat, he said, “we decided to take the initiative. The Six-Day War was an act of legitimate self-defense to save ourselves from total destruction.”

Begin had brought along Dr. Shmuel Katz, a trenchant ideologue and a colleague from their days in the Jewish underground. The meeting took a turn into the dark forest of anxiety that enshrouded Begin and his intimates. Katz unrolled a map of the region, showing the small state of Israel in blue surrounded by twenty-one Arab countries in red—roughly like New Jersey compared to the rest of the United States. Katz asserted that it was a pure myth that there were Palestinians living on the land before Israel was established, and to prove it, he referenced Mark Twain’s dyspeptic account of his travels in the Holy Land in Innocents Abroad, in which he described Upper Galilee in 1867. (“There is not a solitary village throughout its whole extent—not for thirty miles in either direction. There are two or three clusters of Bedouin tents, but not a single permanent habitation.”) Katz went on to say that the Arabs who fled after 1948 had no real roots in the country. “Peasants after all do not flee, even in the midst of war,” he said airily.

Yehuda Avner observed Carter’s clenched jaw and pinched expression as the indefatigable Katz continued his obtuse attempt to undermine any claims that Palestine was ever home to anyone but the Jews. Finally Begin put a restraining arm on his old comrade. “I want to discuss the question you raised about settlements,” he said to Carter. “I want to speak with candor. No settlements will be allowed to become obstacles to negotiations.” However, his policy was that Jews should be allowed to live anywhere they pleased. The West Bank was dotted with towns of historical importance to Jews. “There are many towns named Hebron in the United States, and many named Bethel and Shiloh,” he pointed out. In Genesis, Bethel is the place where Jacob fell asleep and dreamed of a ladder into Heaven. When he climbed to the top, God was waiting and promised him the land of Canaan. Shiloh was a capital of the ancient Israelites before Jerusalem.

“Just twenty miles from my hometown there is a Bethel and a Shiloh, each of which has a Baptist church!” Carter pointed out.

“Imagine the governor of such a state declaring that all American citizens except Jews could go to live in those towns,” Begin exclaimed. “Can we be expected, as the government of Israel, to prevent a Jew from establishing his home in the original Bethel? In the original Shiloh? These will not be an obstacle to negotiation. The word ‘non-negotiable’ is not in our vocabulary. But this is a great moral issue. We cannot tell Jews in their own land that they cannot settle in Shiloh.”

THE CIA PROFILERS HAD scrambled to prepare the dossier on Begin. The analysts read his two memoirs: White Nights, about his imprisonment in Soviet labor camps; and The Revolt, which chronicled his experience as the head of Irgun Zvai Leumi (the “National Military Organization,” known in Israel as Etzel, but abroad as Irgun), an underground group that carried out terror strikes on British forces before independence and then against Palestinian villagers afterward. In his autobiographies, Begin comes off as intransigent, supremely sure of his great intelligence, passionate, riven with guilt, and full of rage. He presents himself as a “new specimen of human being” born out of the ashes of the Holocaust: “the Fighting Jew.” His eloquence teetered on the edge of sophistry and bombast, but he had a genius for picking away at a single word until he had turned its meaning inside out. For instance: “It is axiomatic that those who fight have to hate—something or somebody,” he wrote.

We had to hate first and foremost, the horrifying, age-old inexcusable utter defenselessness of our Jewish people, wandering through millennia, through a cruel world, to the majority of whose inhabitants the defenselessness of the Jews was a standing invitation to massacre them.… We had to hate … foreign rule in the land of our ancestors.…

Who will condemn the hatred of evil that springs from the love of what is good and just? Such hatred has been the driving force of progress in the world’s history—“not peace but a sword”—in the cause of mankind’s advancement. And in our case, such hate has been nothing more and nothing less than a manifestation of that highest human feeling: love. For if you love Freedom, you must hate Slavery; if you love your people, you cannot but hate the enemies that compass their destruction; if you love your country, you cannot but hate those who seek to annex it.

The author of this statement was deaf to the same argument made by Palestinians about their own struggle to overcome weakness and achieve justice. His life had hardened him to the suffering of others. He told Carter that his earliest memory was of Polish soldiers flogging a Jew in a public park. His father, Ze’ev Dov, a wood merchant, inculcated Zionist doctrines into his three children, but insisted on sending them to the Polish high school rather than the private Jewish one. The state school was free, and the Begins had little money to spare; also, in Ze’ev Dov’s opinion, the Polish school would give his children a better chance of getting into a profession. He wanted his youngest, Menachem, to be a lawyer. (Eventually, Menachem would graduate with a law degree from Warsaw University.)

One day, Ze’ev Dov was walking with a rabbi in the street when a Polish policeman tried to cut off the rabbi’s beard. “It was a popular sport among anti-Semitic bullies in those days,” Begin explained, when he told the story to Carter in their first meeting. “My father did not hesitate. He hit the sergeant’s hand with his cane, which, in those times, was tantamount to inviting a pogrom.” The rabbi and Ze’ev Dov got off with a beating. “My father came home that day in terrible shape, but he was happy. He was happy because he had defended the honor of the Jewish people and the honor of the rabbi.” Begin went on: “Mr. President, from that day forth I have forever remembered those two things about my youth: the persecution of our helpless Jews, and the courage of my father in defending their honor.” Later, Begin told his private secretary that he had related the story to Carter because he wanted him to know “what kind of a Jew he was dealing with.”

Menachem was a small, pale child; with his thick, round spectacles, and his full, sensual lips, he was a natural target for bullies. Instead of fleeing, he learned to fight back against the anti-Semites in school—“to beat those who beat us, and to insult our insulters.” He was too frail to inspire caution in his tormenters. “We returned home bleeding and beaten, but with the knowledge we had not been humiliated,” he recalled. What he lacked in physical strength he made up for in his gift for public speaking. Even as a precocious young child, he would recite poetry at the Zionist rallies his father organized, and by the time he was a teenager he was speaking to crowds of hundreds who marveled at his ability to stir powerful and unsettling emotions.

In 1929 Begin experienced a political transformation. Vladimir Jabotinsky, a Russian journalist who advocated an expansive form of Zionism called Revisionism, was speaking at a theater in Brisk. The Revisionists opposed the gradualism that mainstream Zionists endorsed; they insisted on gaining the entire land of Israel rather than compromising with the Arabs already living there. The event was sold out, but Begin sneaked into the orchestra pit. Jabotinsky believed that the Diaspora had left the Jewish people so weakened that they no longer knew how to act in their own interest. Only a state could provide the sanctuary Jews needed to become a people once again. One of his responses was to found Betar, a paramilitary Jewish youth group. The mission of Betar was to create a new species of Jew, one that could quickly build—and ably defend—a Jewish state. He wrote songs for the movement to reach the young minds he hoped to form:

From the pit of decay and dust

Through blood and sweat

A generation will arise to us

Proud, generous, and fierce.

Crowded into the orchestra pit, fifteen-year-old Menachem Begin may have imagined that Jabotinsky was describing him. He felt a spiritual connection with the Betar leader that he later compared to holy matrimony. “Jabotinsky became God for him,” one of Menachem’s friends later remarked.

At the time Jabotinsky was speaking, Jews were outnumbered in Palestine by about eight to one.4 “Emotionally, my attitude to the Arabs is the same as to all other nations—polite indifference,” Jabotinsky wrote in 1923. “Politically, my attitude is determined by two principles. First of all, I consider it utterly impossible to eject the Arabs from Palestine. There will always be two nations in Palestine—which is good enough for me, provided the Jews become the majority.” He recognized that it was “utterly impossible” to persuade the Palestinian Arabs to surrender their sovereignty. “Every native population, civilized or not, regards its lands as its national home, of which it is the sole master, and it wants to retain that mastery always,” he observed. There is not “one solitary instance of any colonization being carried out with the consent of the native population.” Because a voluntary agreement with the Arabs is an illusion, he wrote, there had to be an “iron wall” erected between the Jews and the Arabs—in other words, a powerful military force, which most Zionists believed would have to be their British protectors. Jabotinsky maintained instead that it could only be the Jews themselves. An agreement would not be possible until the Arabs understood that there was no longer any hope of getting rid of the Jews; only then would the leadership pass to more moderate Arab voices, who would ask for mutual concessions. “Then we may expect them to discuss honestly practical questions, such as a guarantee against Arab displacement, or equal rights for Arab citizens, or Arab national integrity.

“And when that happens,” he emphasized, “I am convinced that we Jews will be found ready to give them satisfactory guarantees, so that both peoples can live together in peace, like good neighbors.”

Half a century after Jabotinsky wrote these words, his most famous acolyte was being forced to decide whether that day had finally arrived. Sadat’s gesture had left Begin confused and distrustful, groping in the air. It was far easier to deal with violence than it was with peace. Begin later admitted to Carter that Sadat’s bold move had reminded him of Jabotinsky—as if the Egyptian were the actual heir to his idol’s legacy and not Begin himself.

AFTER THIRTY-SIX HOURS Sadat departed Jerusalem convinced that he had scored a great triumph. “All you journalists are going to find yourselves with nothing to do,” he teased reporters in Cairo. “Everything has been solved. It’s all over.” What about the West Bank, Gaza, Jerusalem? “In my pocket!”

Sadat was being hailed in the international media as a modern prophet or even a savior. “It was as if a messenger from Allah had descended to the Promised Land,” Time magazine gushed. Sadat believed every word. “The Middle East after my initiative to Jerusalem will never be the Middle East that was before,” he exulted on ABC. But the transformation he had wrought came at a cost. The Arab world turned its back on Egypt. There were demonstrations against his visit in several Arab cities, and Egypt Air offices were bombed in Beirut and Damascus. Palestinians in Athens attacked the Egyptian embassy there, killing one person; another was killed in a rocket attack on the embassy in Beirut.

There was an obvious key player excluded from talk of peace: the Palestinians. Sadat was not authorized to represent their interests, and Carter was constrained by a secret U.S. pledge to Israel, made during the Ford administration, not to talk to the Palestinian Liberation Organization—the only authorized representative of the Palestinian people—as long as it failed to recognize Israel’s existence and accept UN Resolution 242. Yasser Arafat, the chairman of the PLO, refused to accept 242 unless the U.S. would guarantee that a Palestinian state would be established and the PLO would lead it. That was too much for Carter, who lost interest in engaging with Arafat.

Meanwhile, the world awaited Israel’s response to Sadat’s historic overture.