Chapter 3. Networks: The Technology of Connectivity

This chapter explores networking: how the things communicate with one another. Designers take this for granted when working with multipurpose computers. But networking for connected devices is different, in ways that can have a radical impact on UX. There are different patterns of network connectivity in IoT; each has advantages and disadvantages.

If you’re a designer without a technical background, a basic working knowledge of how data flows around IoT systems will help you anticipate some of the challenges you may come across.

If you’re an engineer, you will already know much of what’s in this chapter, but you might not have thought about how it can affect the UX.

This chapter is lengthy, but it’s designed as a reference. If you’re keen to get on to the design chapters, just read the first section for now to understand why networking matters to UX. Come back to the rest later, when you want to know more about the underlying technology.

This chapter introduces:

The impact of networks on the UX of an IoT system (see Why is Networking Relevant to IoT UX?)

Some typical architectures of IoT systems (see The Architecture of the Internet of Things)

The basics of different types of network used in IoT, both Internet and non-Internet local networks (see Table 3-1)

Network communication patterns, which govern how data flows between devices (see Network Communication Patterns)

The role of the Internet service and application programming interfaces (APIs) (see The Role of the Internet Service)

It will help you understand:

How network latency and reliability can impact UX (see Latency and Responsiveness May Vary)

How choosing local or Internet connectivity shapes system functionality and UX (see How System Architecture Affects UX)

How gateways are a burden to develop but also often a necessity (see Advantages of Gateways)

Why many edge devices cannot connect directly to the Internet, but how this may change (see IP to the Edge)

How push, pull, and polling communication patterns determine whether a device has up-to-date system data (see Network Communication Patterns)

How API design and UX design are related (see Key design issues for APIs)

Why is Networking Relevant to IoT UX?

When we design for PCs and smartphones, we tend to assume that under normal conditions:

A good network connection will be available (e.g., broadband or fast mobile data)

The device will be constantly connected to the network

The system will feel responsive to the user’s actions

Where the system can’t fulfill the user’s request immediately, it can provide good feedback on progress

If we’re accessing a service via more than one device, all those devices will always be in sync and be up to date with any service information

Both designers and users know that connectivity doesn’t always work perfectly. Mobile coverage can be patchy in places, emails or web pages can sometimes be slow to download, and Skype calls can fail. But things mostly work well enough that we design for a constant, working connection and quick response times as the default state. And when things don’t work, designers can usually mitigate the damage to the UX by:

Saving data to let users resume interrupted actions (e.g., an ecommerce checkout process)

Providing information on what has gone wrong, how much of the intended action was successful, and what the user might be able to do about it (e.g., sending an email delivery failure message)

Designing for IoT is different. Connected devices may use different types of network and have different patterns of connectivity. We cannot assume that they will be constantly connected, or instantly responsive. States that might be edge cases in conventional software UX (device offline, data that is not right up to date) may become core considerations for your IoT UX. On top of this, users may be unprepared for the way that Internet networking will affect their interactions with familiar everyday objects.

The following sections describe the impact that networking can have on UX. If you’re a designer accustomed to working with multipurpose computers, you may not have encountered some of these issues before. A basic understanding of networking will help you work with engineers to anticipate potential glitches, and the best way to handle them in your design. If you’re an engineer familiar with IoT technology, you’ll already be familiar with the technical content of this chapter. But you might not have considered how networking can affect the user’s experience.

Networking Issues That Cause UX Challenges for IoT

The key networking issues that affect UX in IoT are: intermittency, latency and responsiveness, and reliability.

IoT Devices Often Connect Only Intermittently

Many IoT devices only connect intermittently, often as a way to conserve power (as discussed in Chapter 2). This can result in parts of the service being out of sync with other parts. The UX can then feel like a bunch of devices doing different things instead of a single coherent whole (see Chapter 9 for more information).

Latency and Responsiveness May Vary

The Internet gets data from one point to another in a way that chooses reliability over speed. When you send (or request) a piece of data, you know the start and end point of its journey. However, you have no control over the route it will take to get there. This is intentional: if parts of the network go down, your message can be routed via other parts and will probably get through. However, it also means that there are no guarantees as to how fast it will get there. The result is that latency (the time it takes for your message to pass through the network) is out of your control. You could be sending an email to someone on the next street, but the Internet might route your commands halfway around the world.

This inability to control latency is a big challenge for UX because it affects responsiveness. Instant responses cannot be guaranteed when interactions are routed via the Internet.

We expect this delay from conventional Internet interactions. It’s frustrating if your email takes a minute to download, but you know this happens sometimes. At least you usually have some feedback that it is in progress.

By contrast, we expect physical things to respond to us immediately. When you turn on a physical light switch, the bulbs illuminate almost instantly. If you tried to turn on your living room lights from your phone and nothing happened for 30 seconds, that would be a poor experience. But there is no way to guarantee immediate responsiveness over the Internet (see Figure 3-1).

Jakob Nielsen’s 1993 book Usability Engineering sets out guidelines for the responsiveness of a system.[30] A UI should respond to a user command within 0.1 seconds for no delay to be noticed. A delay of between 0.2–1.0 seconds will be noticed, but users think the computer is working on the problem. Delays of more than 1 second require the computer to display feedback to show that it is working on the problem. Nielsen’s guidelines were written in an age when a system was often a single device that may not have been networked. But human perception doesn’t change. The light might not turn on immediately because it takes time to send the command across the network. But the control UI must acknowledge the user’s action right away. (See the smart plug example we look at in The Impact of Latency and Reliability on UX.)

Even 1 second to turn on a light could feel noticeably slow to someone not expecting it. And if the user has time to be surprised by the delay, the interaction has claimed their attention in a way it shouldn’t have. But the nature of the Internet means that it will not be possible to guarantee a response time. It may also not be possible to provide insightful feedback that your action is in progress. (See Networks Are Not 100% Reliable.)

In our view, this will make users far less tolerant of poor responsiveness from consumer embedded devices than sluggish mobile and PC interactions. Engineers will need to find ways of minimizing latency for important interactions. Designers will need to find ways of managing consumer expectations and designing around the limitations.

Networks Are Not 100% Reliable

Another aspect of network communication that may feel strange in the physical world is reliability: whether or not a message gets through. If you flip a light switch, you expect something to happen: the light does not sometimes “lose” your instruction. But a command sent across a network can fail to arrive.

The Internet is designed to maximize reliability and provide feedback on whether or not a message arrived at its destination. (See Types of Network.) But connected devices may use local networks that don’t have the same built-in safeguards. It’s impossible to guarantee that a user command won’t get lost. And it’s sometimes impossible to provide confirmation that the command has been executed.

If commands can go missing, and the user doesn’t necessarily know whether they got through or not, the value of the service is undermined.

All networking is unreliable to some extent. This means that edge devices and gateways (where used) may need to buffer (temporarily store) data when the network goes down and resync once back online.

The Impact of Latency and Reliability on UX

The impact of latency and networking reliability on the UX depends on the type of service you are building. For a large network of pollution sensors, the sensors don’t need to be connected all the time. It’s OK if data does not get through quickly, or even if data points occasionally go missing. But when you are sending instructions to a device such as a light, you expect it to respond quickly.

Latency and reliability can also affect design decisions at the UI level.

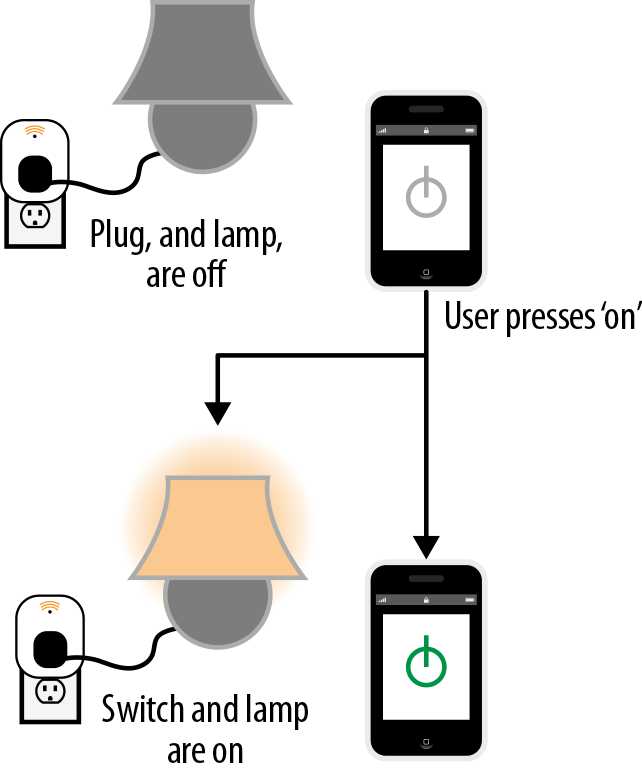

Take the example of a smart plug controlled by a smartphone app. Pressing a button on the app toggles the plug on and off. This feels like an easy and natural metaphor.

This requires two UI widgets in the smartphone app:

One to indicate state (is the plug switched on or off)

One to change state (turn the plug on or off)

The obvious design is to mimic a physical switch and have them be one and the same widget. If it shows “on,” then the switch is on, and touching it will change it to “off” and turn the switch off (see Figure 3-2). This is simple and intuitive, given our everyday experience with switches.

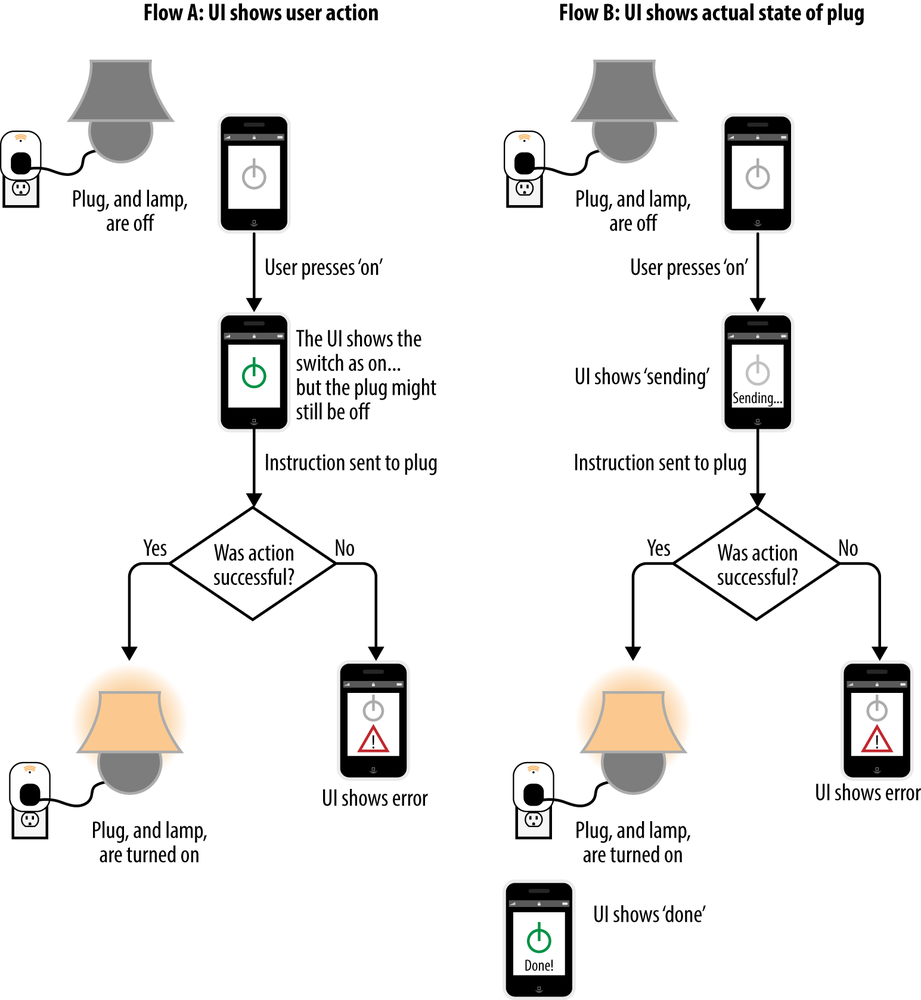

However, network unreliability and latency can raise questions for the UI design. Does the widget indicate what you’ve asked to happen, or what has actually happened?

The obvious design will be responsive, but may not reflect reality. The widget will show that the plug is on before the physical plug turns on (this may be only a few seconds, but it could be longer). If the switch is currently offline, the app will indicate that it is off. In fact, it might still be on, just not connected to the network and therefore unable to receive the instruction.

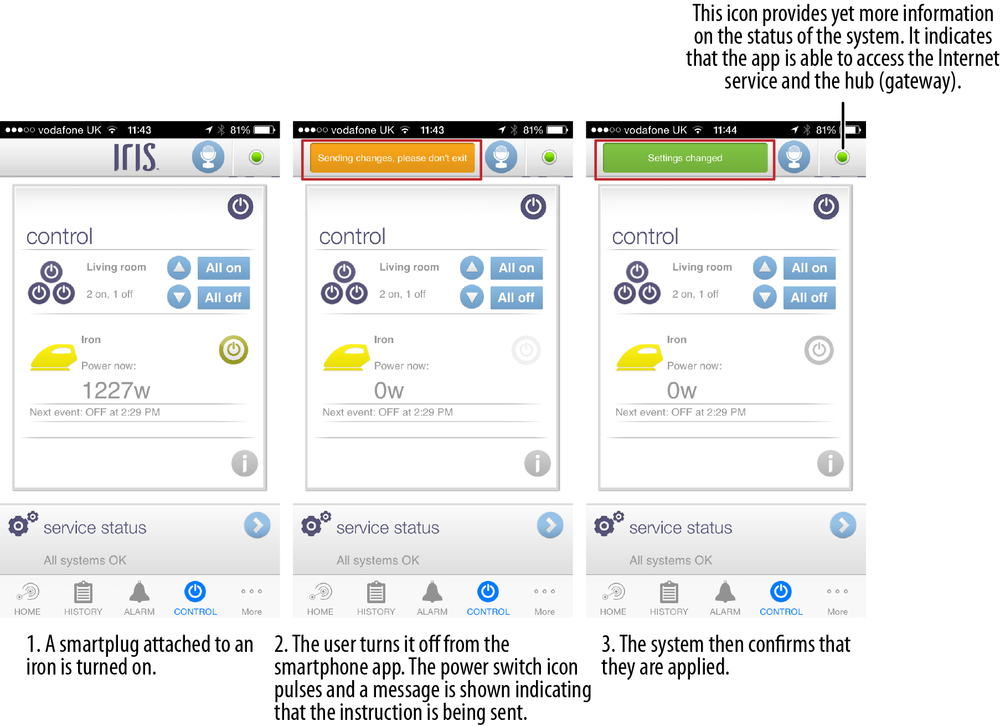

An alternative design might separate these widgets: so one indicates the actual state of the plug and one changes it. If the plug is offline, the UI can show that the current state is not known. This tells us the accurate state of the switch, but means we have to represent in the UI the intermediate states of “off-but-asked-to-turn-on” and “on-but-asked-to-turn-off” (see Figure 3-3 for a comparison of the two approaches, and Figure 3-4 for an example of a UI that uses the second approach). This is a lot more complex than a simple on/off switch! (For a more detailed discussion on handling this issue in UX design, see Continuity in Chapter 9.)

Other Ways Networking Can Impact UX

The choice of networking technology that your system uses can affect the UX in other ways:

- Ease of installation

How easy is it to install a new device? This affects the overall usability of the system. The process of connecting devices to the system (pairing) is slightly different for different network technologies. See Chapter 12 for more information.

- Interoperability

Does the device work with the other devices you want it to work with, and how well does it work? Different types of device may support different types of network, and not all will work together well, if at all. See Chapter 15 for more information.

- Addressability on the Internet

Is the device you want directly addressable on the Internet, or does it need to be connected via a gateway? A fully Internet-enabled device may be able to interoperate better with other devices, but may require you to think more about security.

Note

The rest of this chapter goes into more technical depth around the networking issues that can affect the UX of an IoT system. Of necessity, this is quite long and detailed. If you’re keen to start reading about design (or you already know about IoT networking) feel free to skip ahead to Chapter 4, and return later as needed.

The Architecture of the Internet of Things

The system architecture defines the path through which one device connects to another. This path determines how flexible the system can be, and how responsive and reliable it is likely to be.

This section gives enough background on system architectures to underpin the issues discussed here and in the chapters coming up. It’s worth understanding some common types of network you might encounter, as each has different implications for UX.

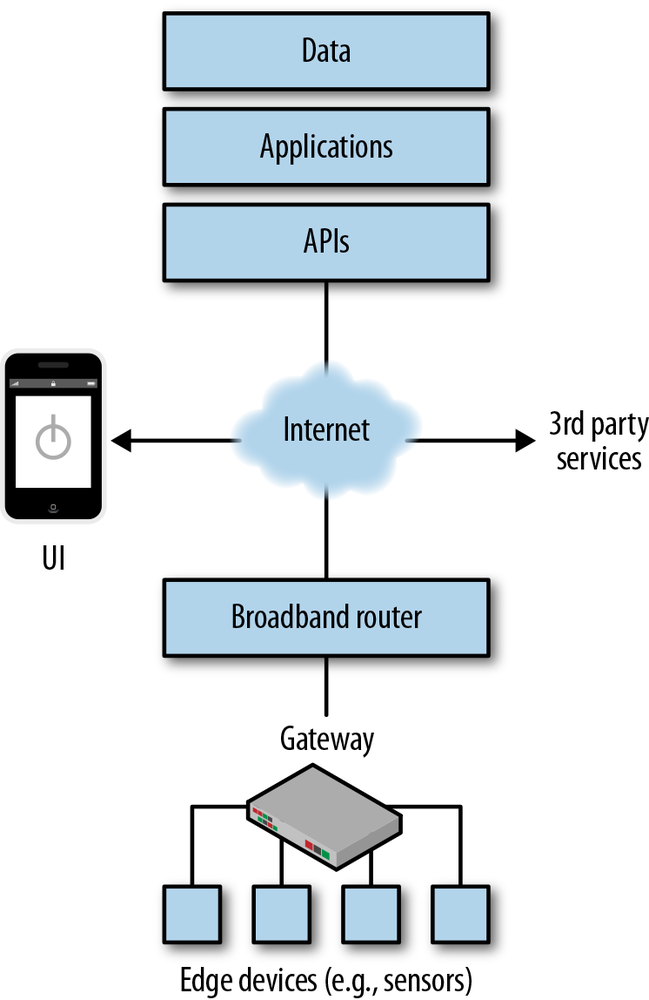

As a general overview, some devices may be directly connected to the Internet. But many are not, and instead connect locally to a gateway, which then connects out to the Internet.

A gateway is a combination of the hardware and software needed to link two different types of network (Figure 3-5). IoT gateways typically translate between Internet Protocol (IP)-based communications and local, non-IP networks used to connect the gateway to the edge devices. The gateway is the furthest point to which the proper Internet reaches. (It’s different from your broadband/WiFi router, which connects devices that support IP networking directly to the Internet.) Consumer IoT gateways are often called hubs or bridges.

We discuss the types of network in more detail in Types of Network. First, this section describes some common architectures for IoT systems, and some of the advantages and disadvantages of each for UX and product design.

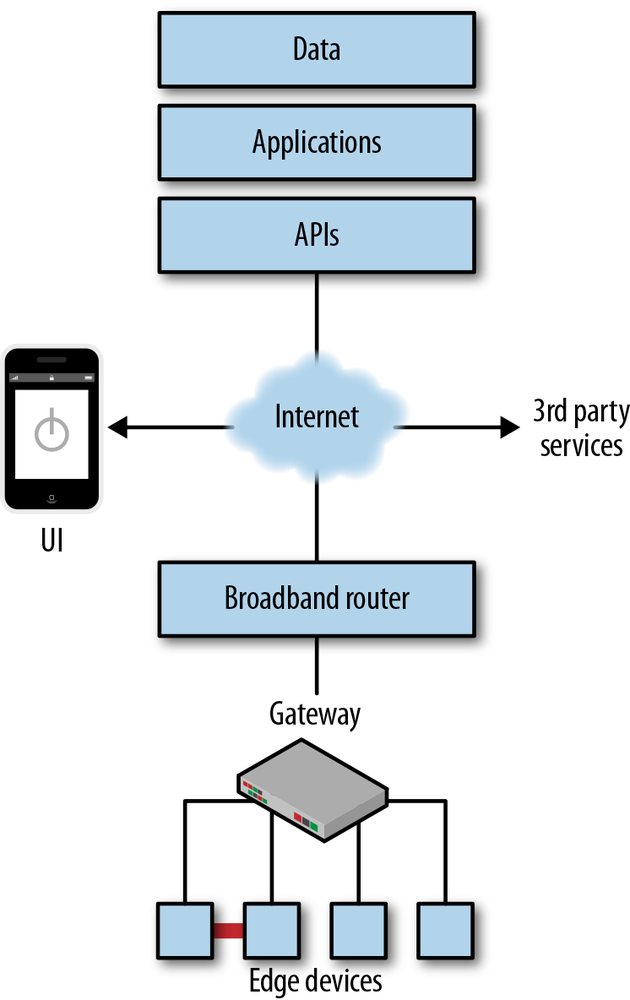

Dedicated Gateway

Figure 3-6 shows a system architecture with a gateway device. This is how a home automation system (like SmartThings) works.

Edge devices (the end points of the system) such as light switches and security sensors use a low-powered network protocol such as ZigBee or Bluetooth to talk to the gateway. None of the edge devices are directly accessible on the Internet: all inbound and outbound communications must pass through the gateway. The gateway translates between the ZigBee protocol and Internet Protocols (we’ll discuss this in more detail momentarily) and provides a security firewall, which controls incoming and outgoing communications to protect the edge devices from malicious attacks. It can also act as a local brain for the system—for example, running the security system or home automation rules.

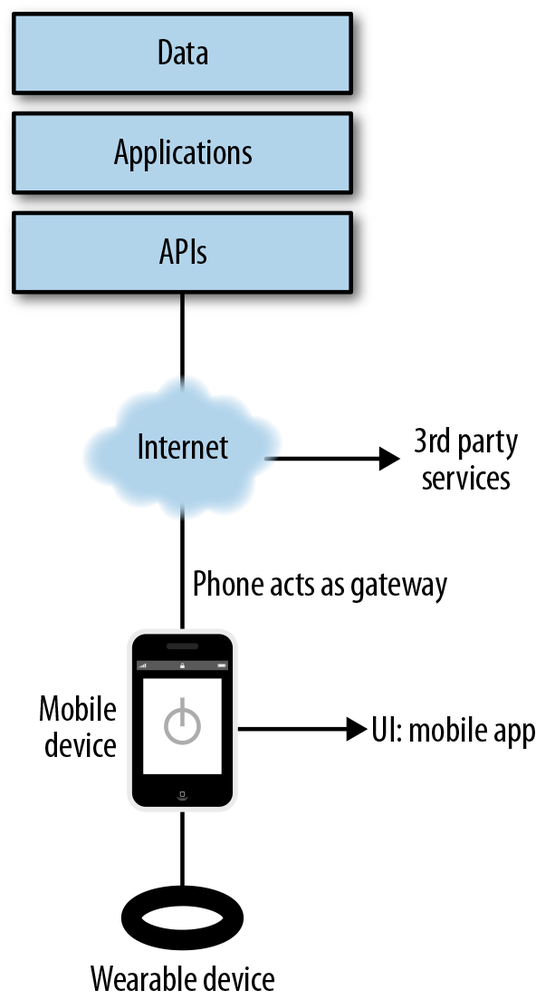

Smartphone as Gateway

A smartphone can also act as a gateway (see Figure 3-7). This is a common pattern for wearable devices, such as the Pebble Smartwatch. The diagram shows a wearable connecting to a smartphone (most likely via Bluetooth). The smartphone has an onboard app that interacts directly with the device. It also acts as a gateway to translate between Bluetooth and Internet networking, via cellular data.

Using a smartphone as the gateway means you don’t need to provide a separate gateway device (as long as your target audience owns a smartphone). However, a smartphone is not a suitable gateway for any device that needs connectivity when the user is not around. A connected home system that needs to function when the house is unoccupied (e.g., to run a security alarm) needs a gateway that is permanently in the home.

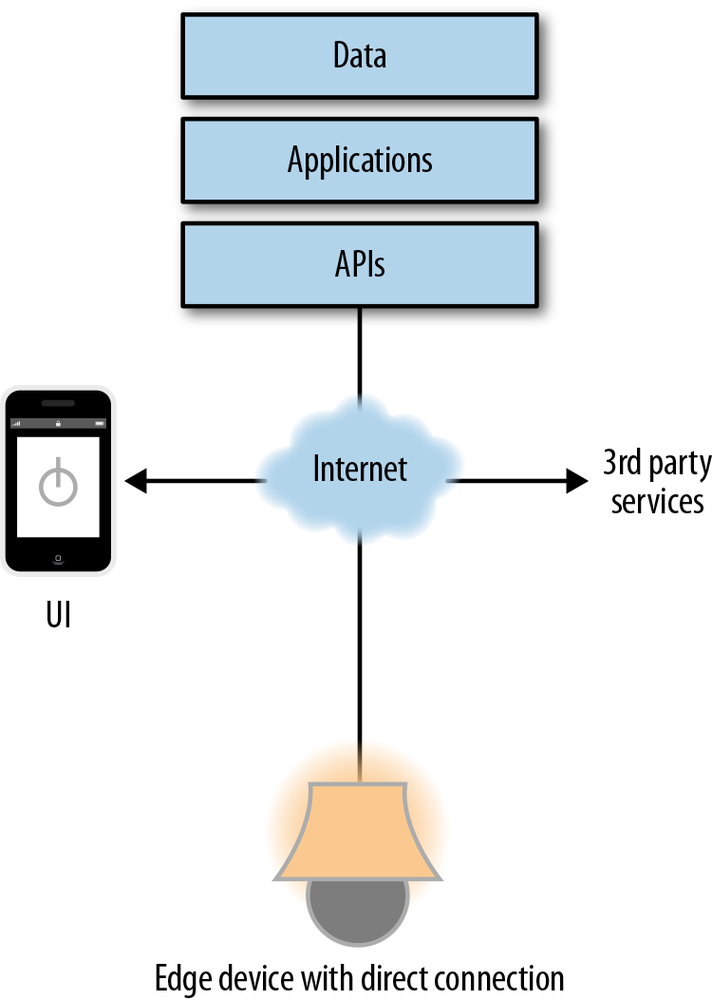

Direct Internet Connection

In some cases, an embedded device might connect directly to the Internet service via WiFi or cellular data without using a gateway (see Figure 3-8). For example, all Belkin WeMo devices connect in this way. These devices nearly always have mains electrical power (WiFi uses a lot of power).

Device-to-Device Connections

Edge devices can sometimes connect directly to each other without going via the Internet or a gateway (see Figure 3-9). So, for example, an intercom system might connect directly to a nearby speaker to sound the alert that someone is at the door. It might also send the alert to the Internet service via a gateway so that if you’re not at home, you can receive alerts and perhaps talk to the visitor. But the connection to the speaker goes direct rather than via the gateway.

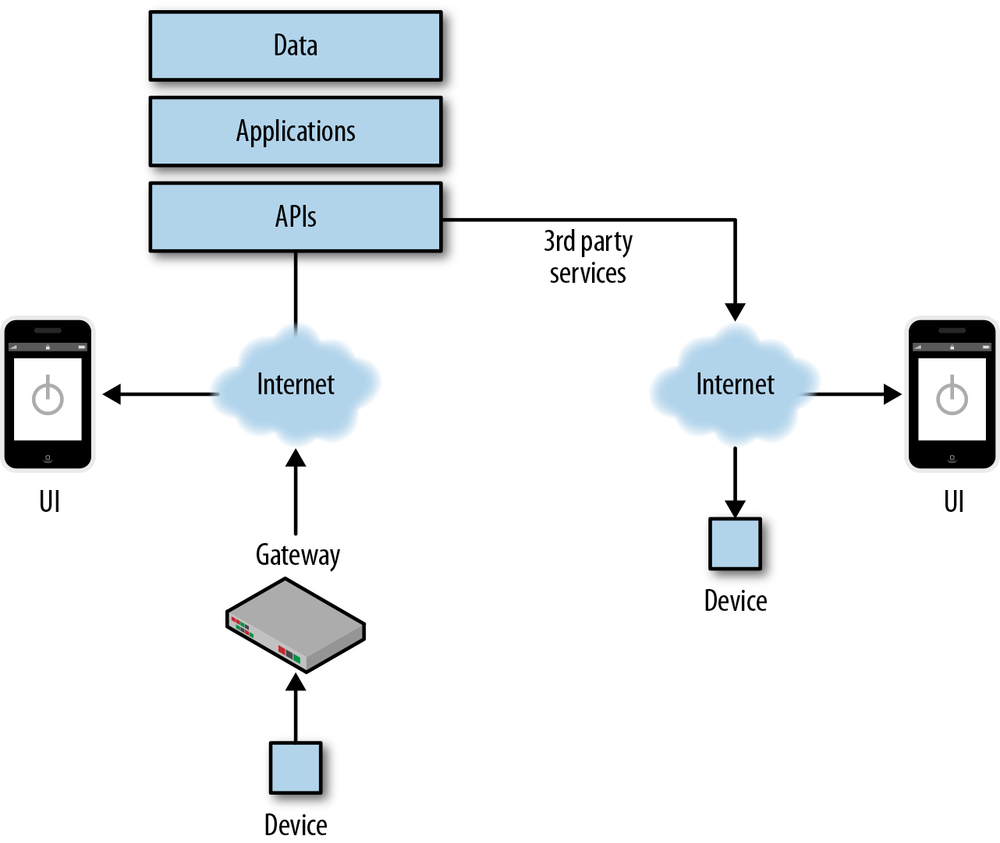

Service-to-Service Connections

Internet services can connect together over application programming interfaces (APIs). (APIs are discussed later in Internet Service.) Devices from different manufacturer services can be integrated without the need for a shared gateway (see Figure 3-10). This is how Nest works with API partners. For example, your Jawbone activity monitor could spot when you’re waking up and notify the Jawbone Internet service. This then notifies the Nest Internet service, which sends a message to your thermostat to turn on and warm up the house.

How System Architecture Affects UX

As explained earlier, the choice of system architecture determines the flexibility, responsiveness, and reliability of the system.

If a sensor is directly connected to an actuator (e.g., a motion sensor connected to a camera), the behavior should be quick and robust. But it is also inflexible: there’s not much scope to add or change system functionality.

If the path from the sensor to the actuator goes through a gateway, there are double the number of wireless connections to break and more code that could contain bugs or cause latency. But there is more flexibility. The sensor can trigger other devices connected to the gateway. The gateway software enables smarter coordination across multiple devices.

If the path goes through the Internet, there is greater potential for unreliability and latency, but the system is more flexible yet. For example, the sensor could now be used to trigger an action on any other Internet-connected device, and the camera could stream video to a smartphone anywhere in the world.

It is possible to do all of these in parallel, to get the best of all worlds: fast, reliable local connections with the flexibility and remote access of the Internet. But this needs careful system design to ensure that everything stays in sync.

Right now, many edge devices can’t run the high-powered networks required to give them a direct Internet presence. But this is likely to change in the future. There is a lot of interest in the technical community in enabling Internet communications over low-powered networks. We’ll look at this in more details in IP to the Edge.

Advantages of Gateways

Gateways (aka hubs or bridges) are an essential part of many IoT systems. They enable devices to work together and can help simplify the UX.

Edge devices can be kept simple

Internet networking and security (such as encryption and decryption) require significant electrical and processing power. Handling these in the gateway allows edge devices to be kept simpler and cheaper. They can run on more basic electronic components and you don’t have to write as much code for them. And if you want to control who can access the system, it’s much simpler to centralize user authentication in the gateway. No one wants to have to log into a light switch.

Security is discussed in more detail in Chapter 11.

Easier setup and maintenance

Gateways simplify installing and maintaining multidevice systems.

If you have a lot of devices that need to connect individually to the Internet, you will have to set up the Internet connection for each one. Imagine all your light switches were WiFi connected. If you changed the password on your WiFi, you would have to reconfigure each one individually. If you moved house, the new occupant would have to set up the light switches on their WiFi network one by one.

With a gateway device, each light switch could be paired with the gateway at the touch of a button over a local radio protocol such as ZigBee or ZWave. You would leave the gateway behind when you moved. The new occupant would have to connect the gateway to their new WiFi network, but they would not have to update every single device.

The system can function when the Internet is unavailable

A gateway can provide a local source of control and decision making that can keep the system running even when the Internet is unavailable. For example, a home automation gateway often stores “rules” locally, so your lighting schedule won’t stop working if the Internet goes down.

Lower latency

You can’t control how data is routed over the Internet, but you can over a local network, meaning latency will be much lower. When you need the system to be responsive, such as turning off the electricity when a gas leak is detected, local connectivity is less risky than routing commands over the Internet.

Enabling interoperability

Gateways can be used to bridge different edge devices that might use different protocols or types of connectivity. The devices don’t need to connect to each other: as long as the gateway can work with each of them individually, they can be used together. So you could combine your ZigBee thermostat, WiFi electrical sockets, and ZWave shade controllers on the same system and access them via the same mobile app. The gateway handles the coordination between the different devices.[32]

It should soon be possible to run Internet Protocol (IP) networking over low-powered networks. Bringing the Internet to edge devices might simplify interoperability even further. Instead of having to translate between different network types, all devices would be able to speak a common language. But this isn’t yet an option (see IP to the Edge).

Disadvantages of Gateways

However, gateways also have disadvantages. The lack of common technical standards means they must be custom built for each system, and centralizing all communications through a single point carries risks.

Time consuming and costly to develop

There are no standard ways to translate between IP networking and local networks. So each service provider creates their own proprietary gateway to meet their own needs. Engineers can’t reuse code written by other engineers, which raises the cost of development. For users, the lack of a standard approach means that different systems won’t work together. And multiple gateways can quickly use up all the Ethernet ports on their broadband router.

A potentially confusing point of failure

If all communications have to go through the gateway, then the gateway is a potential point of failure. If it stops working, so does the rest of the system.

The failure might be technical, or it might be user created. Consumers often don’t understand what the purpose of the gateway is. Unwitting household members may unplug the “mystery box,” as they don’t realize what it’s doing (see Figure 3-11).

As connected devices become more mainstream, gateways may be incorporated into more familiar devices such as home routers or set-top boxes. Table 3-1 summarizes the advantages and disadvantages of gateways.

Advantages of Gateways | Disadvantages of Gateways |

Handling Internet networking and security in the gateway allows edge devices to be kept simpler and cheaper. | Gateways are time consuming and costly to develop, due to the lack of standards. |

Gateways make it much easier to install and maintain multidevice systems: the user doesn’t have to set up the Internet connection for each device individually. | Gateways add another potential point of failure to the system: either technical or user created (e.g., if the gateway is unplugged). |

A gateway can provide a local source of control and decision making that can keep the system running even when the Internet is unavailable. | |

Lower latency: commands can usually be passed more quickly between two local devices over a local network than over the Internet. | |

Gateways enable devices that support different network protocols to interoperate. |

Types of Network

If you’re not already familiar with how networking works, this section will help you better understand how technology can shape UX for IoT and how this may change in the future.

In this section, we’ll look at:

How the Internet works

The pros and cons of different Internet and local network technologies

The potential for bringing direct Internet connectivity to a wider range of devices

How Internet Networking Works

Internet networking is composed of different layers, shown in Figure 3-12.[33] At each layer, there are different protocols: agreed systems of digital rules for exchanging data between computers. Each layer is independent of the lower layers. This means that the application (and the user) doesn’t need to know which low-level communications protocols are being used. For example, when downloading email on your smartphone, you don’t need to know whether it’s using cellular or WiFi, and neither does the email application. This separation of concerns simplifies design and engineering.

Link layer protocols manage data transfer from one computer to another across a single network.

The Internet layer uses Internet Protocol (IP) to manage the transfer of data across multiple networks, called internetworking. At this layer, devices are given a unique identity on the Internet, the IP address. All Internet communications run over IP. If a device supports IP networking, it can connect to the Internet.

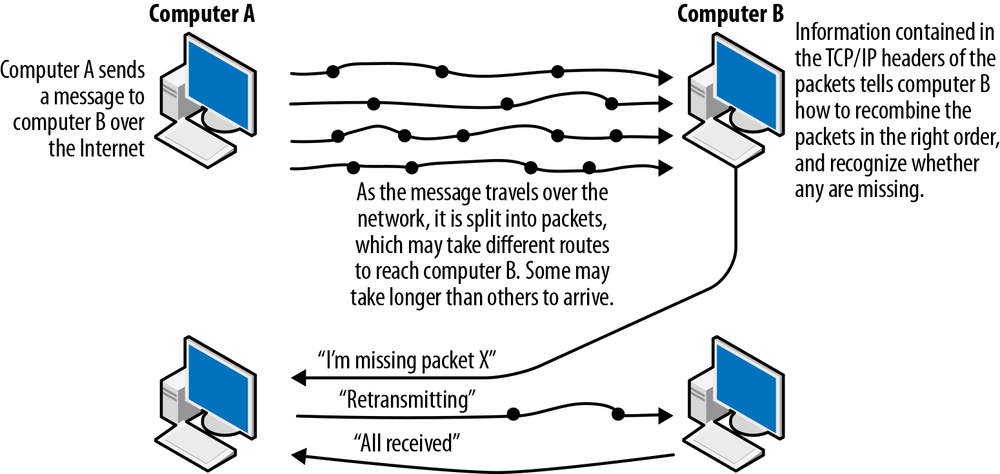

The transport layer establishes a data channel for applications to exchange information with each other. The most common transport level protocol is Transmission Control Protocol (TCP). This allows messages to be split over multiple packets and recombined on receipt, even if they have arrived via different routes. It also provides ways for the sender to know which packets arrived and which went missing, so the missing ones can be retransmitted. TCP is a reliable way of transmitting messages and ensuring they get through without errors, but this comes at the cost of potential delays. TCP over IP (TCP/IP) is the basis of most of the Internet (see Figure 3-13). If a device supports TCP/IP, it’s possible to track whether it received your message or not.

The topmost layer of Internet networking is the application layer, which establishes channels for computer processes to talk to each other. HTTP (HyperText Transport Protocol) is the most common application layer protocol, and establishes the rules for hypertext communication over the Web. Despite the name, HTTP isn’t just for web content and is commonly used for IoT applications. Application layer protocols used in IoT are discussed in more detail in IoT Application Protocols.

If a link layer protocol can support IP running on top, you can use it for any Internet communication. Ethernet, WiFi, and cellular data protocols can, but low-powered networks like ZigBee and Bluetooth cannot (yet). This is why many embedded devices cannot go directly online. (In IP to the Edge, we’ll talk about why this matters.)

Types of Internet Network

Next, we’ll look at some of the connectivity options that currently support Internet networking.

Ethernet

If a wired connection is available and the device won’t need to move around, Ethernet is a fast and reliable option. However, it’s only good for consumer devices that don’t move around, which tend to be kept in the home. Few people have a wired network at home, which means that the device will have to plug into one of the Ethernet ports on their broadband router. Using Ethernet runs the risk that the user won’t have a spare port, and limits them to keeping the device near the router (see Figure 3-14).

WiFi

WiFi can be used to create direct connections between devices, as well as Internet connections via a router. If a device has reliable mains power and tends to stay within the home, it’s generally easiest to connect it via WiFi.[34] But be aware that within the home, some devices may be out of range of the network (e.g., in a garden, cellar, or just because the house is large).

Providing customer support for WiFi devices can be complex, as home WiFi networks are often misconfigured. A misconfigured network may not pose an issue for a laptop but another device, such as a washing machine, might not be able to connect. Consumers may assume this is an issue with the appliance, but it might actually be an issue with the network itself.

Cellular data

Cellular data uses the same data networks to which your mobile phone connects: usually GPRS or 3G/4G (see Figure 3-15 and Figure 3-16). If the device needs to move around or you can’t rely on the user connecting it to a WiFi network, using cellular data may make sense. It also requires minimal user setup: there’s no need for the user to enter network details. But it uses a lot of power and can be expensive, requiring an ongoing subscription to a network provider. SigFox and Weightless are emerging alternatives to conventional mobile data. These have been designed for low power and data needs of the Internet of Things.

Types of Local Networking

This section sets out the types of local networking most likely to be used for consumer applications. None of these currently support IP so cannot be used to connect devices directly to the Internet, only to a gateway. However, it is likely that in the future it will be possible to bring IP to edge devices over some of these radio types, giving them a direct Internet presence. (See IP to the Edge for more details.)

Bluetooth

This is typically used to connect peripherals to mobile phones. Bluetooth is useful when the device is primarily used in range of a phone and in the presence of the user. This works well for wearables and detecting the presence of the owner (see Figure 3-17). It does not yet support IP networking in the real world but the standard allows for it.

Bluetooth LE (low energy; also known as Bluetooth 4 or Smart) is especially suited to connected devices with power constraints. Classic Bluetooth requires paired devices to maintain an open connection to each other, which means that their Bluetooth radios are constantly in use. This could drain the battery of a low-powered device very quickly. Bluetooth LE allows for devices to connect and transmit data at regular intervals, or when they have something to share. This uses less power and preserves battery life.

Bluetooth LE is also beginning to appear in home gateways and home devices (see Figure 3-18).

Proprietary radio

Traditional baby monitors are an example of proprietary radio networks (see Figure 3-19). They use custom connections entirely controlled by the manufacturer. They may be reliable and cheap (there are no license fees for the manufacturer to pay as there would be with Bluetooth, ZigBee, or ZWave). But as the service provider, you have to have control of all the devices that are connected to them. They will not interoperate with other devices and may interfere with them.

ZigBee and ZWave

ZigBee and ZWave are low-powered radio networks, suitable for battery-powered devices and designed for use in home automation systems. Both have a similar range to WiFi. Unlike WiFi, the range of a ZigBee or ZWave network can be extended through mesh networking. This allows any of the devices on the network that run on mains power to act as repeaters, extending the range of the network. Neither currently supports IP networking.

The Nest thermostat connects to the Internet over WiFi, but also has a ZigBee radio. It could in the future act as a gateway for other low-powered devices in the home, giving Nest a route to becoming a home automation platform.

WiFi, Bluetooth, and ZigBee all operate on the 2.4GHz frequency, so there is a risk of interference. For example, there is a slight risk that, if you maxed out your WiFi network transferring videos, your ZigBee light switches might not work. In practice, problems are rare and WiFi routers are getting better at coexisting with other networks, but it’s worth being aware of the risk.

RFID and NFC

Radio frequency identification uses electromagnetic fields to transfer identifying data from small tags to a reader. Passive RFID tags are powered by an electromagnetic field from the reader. They have a very short range (10–100 cm). Active RFID tags have their own power source and can broadcast their ID over longer distances (10–100m). The microchip used to identify household pets is a passive RFID tag (see Figure 3-20), as is London’s Oyster transport card.

Near field communication (NFC) is a set of communications standards built on top of RFID to enable two-way communication. It is designed for mobile phones and other low-powered devices. NFC is often used for mobile payment and works over a very short range (a few centimeters). NFC can also be used to simplify setup of more powerful network connections such as Bluetooth and WiFi. Android Beam and Samsung S Beam are examples of these. NFC could be used to make it easier for consumers to connect home devices together over other network types.

Chapter 12 covers design approaches for connecting devices together over different types of network. (Examples of RFID and NFC applications are also discussed in Chapter 2.)

Powerline networking

Where Ethernet is unavailable and wireless networking too unreliable, it is possible to run data over preexisting electrical power lines using the HomePlug standard. An adapter, plugged into an electrical socket, is connected to Ethernet where a port is available (see Figure 3-21). Another adapter is plugged into an electrical socket near the device that needs connectivity, and connected to the device with an Ethernet cable. Data is transmitted over the electrical wiring.

In addition to being simple to set up, powerline networking is fast, secure, and reliable. It runs through thick concrete floors that might cause problems for WiFi. However, it acts as a radio transmitter and in some countries is legally classed as a form of broadcasting, which requires a license. Where multiple devices are plugged into it, it is possible for the signals to interfere with one another.

IP to the Edge

As we’ve seen, many edge devices cannot speak or understand Internet communications without translation by a gateway.

There is not yet a standard way to translate between Internet networking (TCP/IP) and most non-IP local network protocols such as Bluetooth and ZigBee. This means that custom translation must be built into the gateway apps.

This limits edge devices to doing only what the gateway apps allow. The Internet service can’t talk directly to the edge devices to ask them to do anything else. For example, if you want to use your security motion sensors to inform your heating system that you are in, you have to change the apps on the gateway. The heating system can’t just contact the motion sensors and ask them for the data.

But delivering Internet communications (over IP) all the way to the edge device, across even low-powered networks, is a growing area of interest, to provide many more edge devices with a unique identity on the Internet so they are able to contact (and be contacted by) any service and do anything they want. This is a true Internet of Things.

This would enable a far greater degree of flexibility of functionality. Instead of asking the gateway to pass on a message to a device and hoping that the gateway knows what to do with your particular request, you can contact it directly. You could compare this to the convenience of having a person’s mobile number, as opposed to an office switchboard where you need to leave a message with a receptionist. If you have the mobile number, you don’t need to know where they work in order to get hold of them.

Likewise, a device can identify itself uniquely, no matter how it connects or where from. For example, an electric vehicle could be charged at a friend’s house, and the electricity billed to the car owner, not the friend whose house it was.

Giving all these connected devices unique IP addresses will require a change in standards. Most IP addresses are currently based on the standard IPv4, which provides 4 billion possible IPv4 addresses. This may seem a lot, but it’s not enough to support the billions of connected devices predicted to come online in the next few years. The incoming standard IPv6 provides for the equivalent of 10 IP addresses for every atom on earth.

Initiatives are in development that would allow IP networking to run on top of Bluetooth, ZigBee, and other low-powered local area networks. 6LOWPAN is an IETF working group proposing solutions for IPv6 for low-power wireless personal area networks. In August 2014, Nest and other companies including ARM and Samsung announced the development of a new standard for low-powered networking, named Thread.[35] This can use existing ZigBee radios but supports IPv6.

When edge devices can speak IP, any standard higher-level Internet-based protocol can run on top. So you could use the same application protocol to talk to all your home devices. You no longer have to care about how the devices connect at the link layer, or translate between different network protocols. This will make it much easier for devices with different radios to interoperate. As engineer and founder of 1248.io Pilgrim Beart puts it:

Using the Internet (even to go a few metres from your smartphone to e.g. a PVR or audio system) may sound technically rather mad, but it has the huge benefit that it avoids the problem of physical standards, using the Internet as a lingua franca. Your phone and the PVR may not support the same physical standards but they can still communicate. It also allows you to remote-control from anywhere in the world.[36]

The standards and application protocols needed for this are still in development and are not yet consumer-ready. Also, making connected devices directly reachable on the Internet opens up security risks that would have to be mitigated.

Devices that use low-powered networking would still need to connect via a gateway with the appropriate radios to talk to those devices. But the gateway can be simpler: providing connectivity, a firewall, and local intelligence required to coordinate the devices when the Internet is unavailable. There is more potential to concentrate intelligence in the edge devices and the cloud.

Network Communication Patterns

Communication—how devices send and receive data to the network—can be handled in different ways. This is largely governed by protocols in the application layer. Understanding the way data flows around the devices in your service allows you to understand how responsive it may be and how rapidly data will be synchronized between devices.

Push, Pull, and Polling

As a UX designer, the key factors that you’ll need to be aware of are:

How the device transmits messages to the network. Does it push them at regular intervals or when certain conditions are met? Or does it only transmit when a client device (like a smartphone app) or the service requests it (pull)?

How the device receives messages from the network. Are messages pushed from the service or another device, or does the first device request them as needed?

How frequently the device is connected. Is it constantly connected, connected at regular intervals, or only connected when it knows it needs to be?

How fast instructions or data may get through. This is a combination of:

How long it takes the device to establish a connection

How fast the connection may be

How much data is being sent

How directly it may be routed (anything that goes over the Internet may take longer)

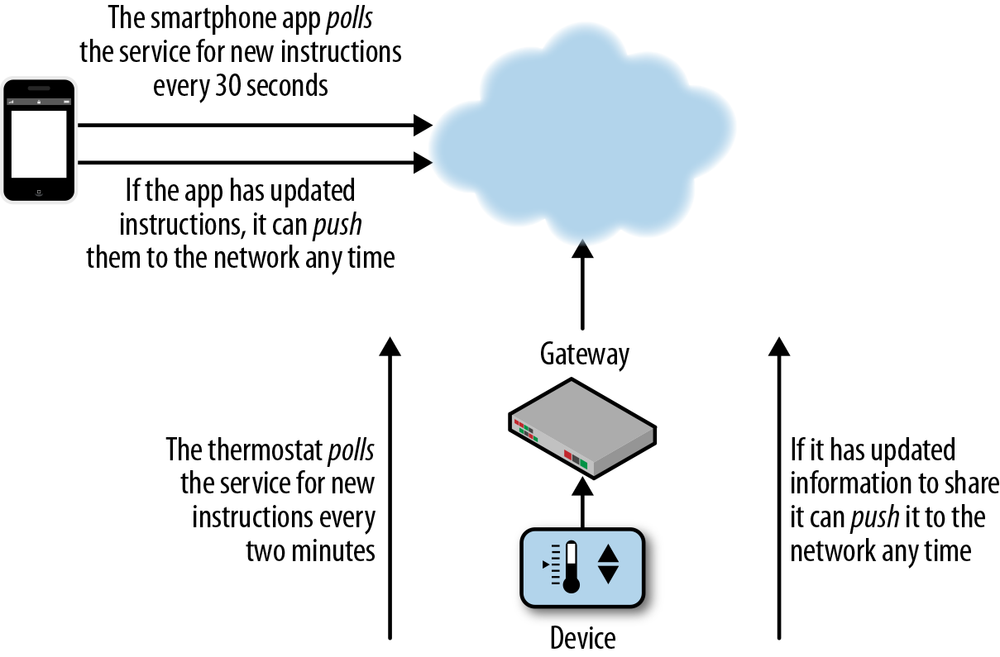

The following example, illustrated in Figure 3-22, illustrates some of the issues you may encounter:

A battery-powered heating controller using ZigBee contacts its gateway every two minutes to register its status and look for new instructions. This is called polling: the controller does not know when there are new instructions, but must check in regularly for updates.

The user turns the heating up from 19° C to 21° C using a mobile app. The app passes the instruction to the Internet service. The gateway device polls the Internet service at regular intervals and receives the instruction. (The gateway has mains power, so it can poll quite frequently, perhaps every few seconds.) The heating controller polls the gateway and receives the instruction.

If the user is in front of the heating controller while using the mobile app, they might see the controller take up to two minutes to respond to the command from the mobile device.

During this period, the phone UI and controller display will display different status information and will be out of sync. The phone may say 21° C, and the controller 19°C. The controller reflects the current true state of the system. In interusability terms, this is a continuity problem. (See Chapter 9 for more details.)

It would be quicker to push the instruction from the Internet service down to the gateway and device. But this is often not possible to do through home routers. Most routers present a single public IP address to the world and keep the addresses of devices on the local network private.[37] So it’s difficult for servers to push to, or pull from, devices on local home networks. Security firewalls may also be an issue.

So, the device has to poll out to check for new instructions, and this can take longer.

There’s likely to be less delay if a user turns the heating up using the controls mounted on the heating controller device. The controller knows that there has been a change to the system, and pushes a message with the updated information via the hub to the Internet service. It knows it needs to connect so it doesn’t wait for the next scheduled poll. If the user’s heating control smartphone app is open, it might request new data from the service every 30 seconds. So if the user is looking at their heating smartphone app at the same time, they might still perceive a discontinuity, but only a short one.

Both the smartphone and the heating controller are polling the Internet service for changes, an example of pull. Both are able to push a message when they know they have updated information or commands to share.

Neither maintains a constant connection to the network, as this would drain battery power. But the phone can check in more frequently than the controller, as it is less power constrained.

Although this arrangement does expose occasional discontinuities, in the context of a heating system these are not disastrous. Most of the time, users are not standing in front of the heating controller with a smartphone. And most of the time, a two-minute lag between issuing the instruction to the heating and it actually turning on is not a problem: heating operates on a timescale of hours rather than seconds.

A polling interval that is too long can make the service feel too unresponsive. For example, using If This Then That (IFTTT),[38] a Philips Hue bulb can be configured to flash or change color when an email is delivered to your Gmail account from a particular recipient. That’s a nice idea, but IFTTT is only able to poll Gmail every 15 minutes (perhaps a limitation imposed by Gmail to avoid undue load on their servers). This means the light may not respond until 15 minutes after the email was received. That’s a very unresponsive notification system.

If you want a device to respond quickly to a command, it has to either maintain an open connection to listen for pushed commands, or poll more frequently. A good example of consumer push notification is Google Contacts. If you update a Google Contact using the Web, an update is pushed to your phone within seconds. The phone is not regularly polling: it receives a spontaneous update notification from Google’s servers.

Frequent polling when there is nothing new to share can place a load on servers (and exhaust batteries). Maintaining many open connections to lots of different devices is similarly impractical. But a device without an open connection cannot be reached for you to tell it to connect. When you need a device to respond quickly you may need an open connection. For example, the shutoff switch to your home’s electricity supply should turn off right away if a gas sensor detects a leak.

It’s easier to control the timing by which a device sends commands. A device can be configured to send data to the network when certain conditions are met; for example, the heating schedule is changed, or a moisture sensor detects water in a basement. It could be configured to keep trying to send data more frequently in certain conditions. If a heat detector that only transmits status every 2 minutes detects a possible fire, it might transmit every second for the next 20 minutes. If it could not contact its usual network gateway, it might hop through alternative nodes on a mesh network to try to get through. With a static IP address (e.g., IPv6) and the appropriate applications in place it could theoretically also try to use a neighbor’s network in an emergency.

A device may also need ways to alert the user when a message has not gotten through. An elderly person’s emergency alarm button should be as reliable as possible and offer backup connectivity, such as cellular data. But the button should still be able to tell the user not just whether their call for help was sent, but whether it was received by the system at the other end.

A key consideration for UX is to understand how quickly data is passed around the system, and whether this is a good fit for the context of use. For example, a home energy monitoring system for electricity usage might upload the last 24 hours’ data to the Internet service every few minutes or longer. When you request this information, it would be sent from the Internet service rather than querying the energy monitor directly. This might be quicker, and/or reduce cellular data costs to your energy company. However, if you want to know whether your front door is locked, it’s very important to know whether or not that data is 2 minutes old—someone might have opened it in the meantime.

IoT Application Protocols

Application protocols sit in the topmost layer of Internet networking. They establish channels for computer processes to talk to each other. They shape the connection patterns by which devices pass and get data to and from the network. The choice of application protocol your system uses is largely a technical design issue, and is unlikely to have a big impact on UX. However, it’s worth being aware of some of the options you may hear about, and understanding how the system you are working on passes data around.

It’s common for IoT applications to communicate over the Internet using HyperText Transport Protocol (HTTP).

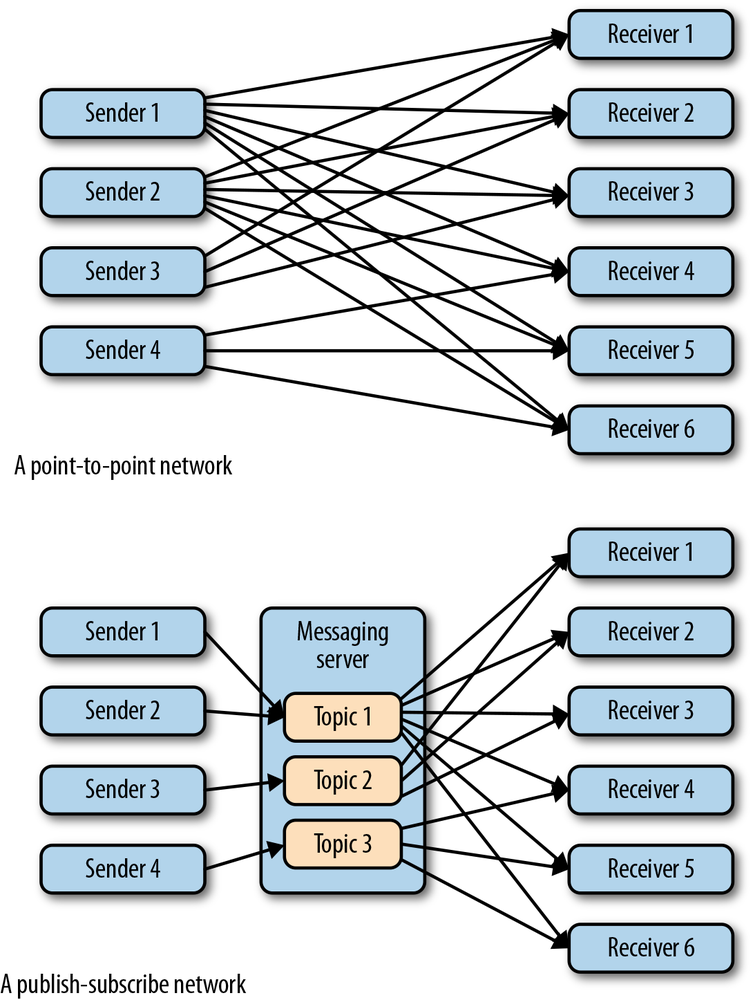

HTTP is a reliable way to pass information around a small number of devices that don’t need to be updated instantly of any change. But it is not designed for push or streaming and so usually requires polling. It’s also not the most streamlined method of passing data around lots of devices, especially ones that have power and computation constraints. It requires a direct connection to be established between any devices that need to share data (a point-to-point network, see Figure 3-23), and messages take up a lot of bytes.

Other protocols, notably MQTT, have been designed specifically for the Internet of Things. These prioritize smaller data transmissions and more efficient ways of passing data around large networks of low-powered devices. Instead of direct connections, MQTT uses a publish-subscribe model where devices push data to a central message broker. Other devices can subscribe to the data feeds (“topics”) they want (see Figure 3-23). It can be fast: Facebook Messenger runs on MQTT. It’s also a more flexible way to manage interconnections between lots of devices: each one simply tunes into the topics they want.

But HTTP is widely supported. It allows sensor networks to be explored in an easily accessible and universal way, through web APIs (discussed further in APIs). It also gets through firewalls, because it looks like normal web browsing.

Internet Service

In this section we’ll look at the role of Internet services in IoT systems, and how the design of APIs (application programming interfaces) relates to UX design.

The Role of the Internet Service

It’s common for IoT systems to rely on some kind of remote centralized Internet service to collect, process, and distribute data and instructions.[39]

The Internet service would generally include some way of storing and handling:

System data (e.g., sensor data or the current state of the devices)

Applications that run on top (e.g., health monitoring or lighting)

The service makes data and system commands available to mobile or web apps via application programming interfaces (APIs). Increasingly, service providers make APIs available to third-party developers to enable other services to integrate with the system.

For example, data captured from a sensor network is aggregated and processed by an Internet server, which publishes a summary of the data.

System designers have a choice as to where processing happens: in the remote service (“cloud”), gateway, or edge device. Doing more processing in the cloud makes it easier to maintain one centralized view of the system. But the system won’t work when devices lose connectivity and can’t access the cloud.

That’s acceptable for nonurgent data, such as air quality monitoring. If sensors go temporarily offline, they can store data and upload it when they reconnect. The worst that happens is that some data may be old.

But it’s not OK where data must get through fast. It’s unacceptable if a baby monitor does not alert a parent in the next room that the child has stopped breathing. This is where local processing is needed, so devices can work without the Internet (e.g., a thermostat with on-device controls, or a gateway that can continue to control the home lighting).

An Internet service may be proprietary (custom built for your service), perhaps with APIs to share data with third-party services. Or it may be an open service (e.g., the Thingspeak[40] open data platform). If you are depending on someone else’s service, then bear in mind that if they have an outage, raise their prices, lose or publicize your data, or go bust... then so do you.

A platform (in this context) is a type of software framework that can be used to build multiple remote service applications. Thingspeak, Kaa,[41] Xively,[42] and Thingworx[43] are examples of platforms that developers can use to create IoT services. Platforms can make it easier for engineers to get a system up and running, but might lock you in or lack flexibility. Relying on a third-party platform carries the risk that the platform provider may go out of business. Separate services connected with open standards may provide more control and choice: if you need to, you can swap out one service for an equivalent.

APIs

An application programming interface (API) is an interface for developers. It provides hooks for them to build things out of your system. This might be your own frontend web or mobile apps or third-party services that interact with your system. APIs are an essential part of creating ecosystems of interoperable devices and services.

APIs enable developers to create web services that can easily be linked to other services. So you needn’t build your own weather forecasting service for your rain-predicting device: you can easily call on a third-party weather service’s API. The principle of “small pieces, loosely joined” encourages developers to create targeted services that do one thing well and can interoperate well with other services. This provides the flexibility to combine different services together to create entirely different applications.

UX people are not usually responsible for designing APIs, but API design can have a significant impact on the UX you are able to create. The functions you make available in your APIs determine both what you can do with your own UX design, and what others (third parties) can do with your service.

Designing APIs is very much like designing an information architecture for a content website. You need to understand what information your users need, and how it should be chunked and organized to make it easy and quick for them to find what they want.

Sometimes design decisions will involve trade-offs: by making some tasks easier, you’ll make others harder.

If your UX design and your API design are a poor fit for each other, the result can be long latencies, poor responsiveness, and overloaded servers. API design should run hand-in-hand with product definition and UX design.

How do web APIs work?

APIs can describe data or function calls. They can be written in many languages, but in this chapter we’ll use the example of standard web APIs, which are based on HTTP.

Web API calls apply actions to URLs. Here’s an example of a possible API URL structure for a connected home system: http://api.[serviceprovidername].com/property/gateway/devicetype/device/channel"/>.

The first part is the service provider’s public domain name.

property is the home in which the system is based (e.g., Claire’s house).

gateway is the name of a gateway device (in case you have more than one).

devicetype is the name of a type of device (e.g., motion sensor, contact sensor, light switch).

device is the name of a specific device assigned by the user (e.g., dining room motion sensor or back door contact sensor).

channel is a data feed from that device. A device might have more than one (e.g., all motion and contact sensors might also sense temperature, so would have two feeds: motion and temperature).

You can use the API to retrieve data, or in some cases, send commands to the system, by sending requests using HTTP methods.

The GET method is the most common and is used to retrieve data. To use our example: if you wanted to retrieve status information from all the motion sensors in the house, you could do so by making a request using the GET method to: http://api.[serviceprovidername].com/claireshouse/gateway1/motionsensors".

The system would respond with something like the following XML code:

<channel type="motion"> <events> <event type="motion" detected="no" timestamp="" location=""/> <event type="motion" detected="no" timestamp="" location=""/> ... (one entry for every motion sensor in the house)... </events> </channel>

If you have the authorization to do so, it’s also possible to use other methods to modify data on the server.

In our example, if you wanted to turn on the light in the dining room to 50% dimmed, you could make a PUT request to:

/{ claireshouse/gateway1/lightswitches/diningroom <light> <state value="on"/> <dimming percentage="25" </light>

These are very simple examples, but should help you understand the design issues described in the following sections.

Key design issues for APIs

The key decisions to be made when designing APIs are the granularity of data and controls, and how you organize them into hierarchies.

Granularity

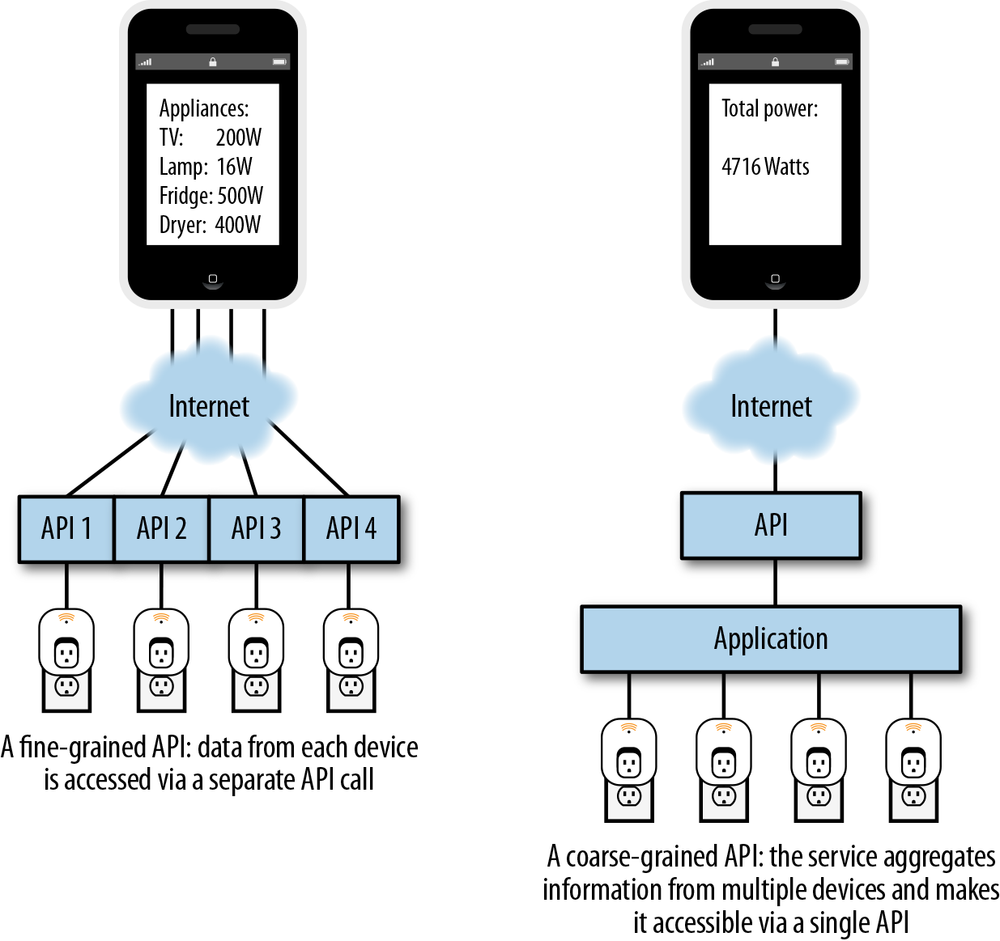

A simple system, composed of one device connected to the Internet, can have a simple API. The device posts key data it has collected and you can pass simple commands (controls) back to it, as in our previous example. This is a fine-grained (or end point–oriented) design, as it exposes low-level data from the device itself.

End point/fine-grained APIs (Figure 3-24) allow for control of specific devices or retrieving specific pieces of data, which is fine for small systems. But if you want to retrieve data from many devices at once, a fine-grained system means making lots of individual API calls. This will be slow: each API call could take 1 second per round trip on a 3G connection. A web page or mobile app screen that has to make 20 API calls will be much slower to load than one that only makes two or three.

In IoT systems with lots of devices, the individual devices often aren’t important to the user anymore. If you want to know the temperature of your living room, you want to think about the room, not about the devices in that room that can sense temperature. The system should calculate the room temperature for you and make this available via a single API call.

These are examples of task-oriented (designed for specific tasks) or coarse-grained (aggregated data) API functions. The service aggregates data from multiple devices and applies some processing on the backend. Your smartphone app then only has to make one API call to know which lights in the house are on or off.

Task-oriented APIs make it easier to support complex functions across multiple devices. You could tie your API tightly to your UI, aggregating all the data needed for a particular screen or widget accessible via a single API call. This would be highly responsive but would need redesigning if you ever wanted to change your UI. Any third parties using your APIs would have to present data in exactly the same screen/widget chunks as you. So task-oriented APIs risk inflexibility: UX designers and developers have to use them in the ways that you bake into the API design.

If an API is too coarse grained, it may also prevent you from accessing the individual device or data you need. You may sometimes want to turn off all the lights, but you also sometimes want to turn off just the hallway light.

Niall Murphy from Evrythng cites the real-world example of a connected car with a single API. This is designed for repair/manufacturer diagnostics, but impractical for other uses:

You can either turn on a stream of all the information from the car or turn it off. The home doesn’t need a stream of the location of the car at all times to open the garage door when you get home. You need to bite-size info down to what is needed for a specific application.

It’s possible to have a mixed design, with some aggregated data and task-oriented APIs, and some end point (device) APIs. This would enable you to show the energy usage of all the appliances in the home, but also just to track usage of the tumble dryer.

Structure

As well as choosing the right granularity of data and controls, you also need to group and organize units (devices and data points) in an API to make sense/be usable to others. This becomes increasingly important the more devices and data points you have.

The way in which data/devices are organized in your APIs can make it easier or harder to retrieve data or apply controls from/to the combination of devices you may want. Trying to create a UX design from an API design that is not a good fit will result in a sluggish, unresponsive UX.

Devices in a home might be organized by their sensing ability (e.g., temperature or motion), location (e.g., kitchen or upstairs), the applications they support (e.g., security or heating), and more. Some can do more than one thing—for example, some devices can sense both temperature and motion and/or might be used by more than one application. If you drew a map of the interrelationships between those devices, it would look like a network structure (see Figure 3-25).

Users might want to access different organizational groups. For example, you might want to see temperature readings around the house. Or you might want to view all the security devices. Or you might want to check up on the current status of every device in the living room.

For complex, multidevice systems, a network type UX often seems like an intuitive way for the user to explore what’s available. From the living room motion sensor, you could browse to other security devices, other motion sensors, and other devices that measure temperature.

The trouble is, providing this much flexibility in the UX isn’t necessarily easy using APIs. In particular, looking up related data is often a challenge. URLs are hierarchical, so they don’t reflect all the ways data can be interrelated.

Take the dining room temperature example we looked at previously. On the same screen as the dining room temperature, you also want to show readings from other temperature sensors in the home. To the user, this might seem like an obvious thing to do: from one temperature reading, I can view the others. But in this schema, they all sit at the bottom of the tree structure and their relationship to one another is not mapped. So you’d have to call the data from each of the other temperature sensors individually. This would be slow and inefficient, just as if you were having to browse up and down the tree structure of a website to compare lots of individual pages of content.

If you’re designing a small system with only a few devices, then the potential inefficiencies are small. But the more data points and devices you have to contend with, the more important it is that your API structure is a good fit for the UX.

As a UX designer, the important thing is to make sure that you work closely with your developers as the APIs are designed.

Third-party APIs

You may be relying on a third-party API, such as Xively or Twitter. If so, you’re bound by their terms and you need to check how you can use them. Providers often impose limitations on the frequency of calls you can make, or the number of API calls per day to avoid overloading their own servers. They may also charge for API calls, as the weather service forecast.io does.[44]

Summary

Networking has a fundamental impact on the UX of an IoT system. Many connected devices connect only intermittently to the network to poll for new instructions. This can create small delays in which parts of the system are out of sync with each other. Network latency and reliability issues may mean that connected devices don’t behave as we expect real-world objects to do.

The system architecture determines how devices pass data around a system, where processing happens, and what will or will not work when parts of the system are offline. Devices may connect directly to the Internet or via a local connection to a gateway. Many devices can only support low-powered networking like Bluetooth and ZigBee. Gateways enable these devices to be connected indirectly to the Internet. In the future, delivering IP over low-powered networks will enable more devices to be directly connected to the Internet. This use of Internet standards will make it easier for different systems to work together.

Application protocols shape the connection patterns by which devices pass and get data to and from networks. Data may be pushed or pulled to a device; the device may be constantly connected or poll for instructions at regular intervals. HTTP is commonly used; specialist IoT protocols like MQTT are optimized for low-power devices with limited bandwidth.

All IoT systems rely on some kind of remote centralized Internet service to collect, process, and distribute data and instructions. The service makes data and system commands available to mobile or web apps via application programming interfaces.

An application programming interface (API) is an interface for developers. It provides hooks for them to use system data to make end user applications and in other systems. If the API design is a poor fit for the requirements of the UX, it can result in a slow, unresponsive experience or overly restrict the functionality you can offer.

Case Study 1: Proteus Digital Health: The Connected Pill

Medicines are an amazing innovation of the 20th century, but they only work when taken correctly. Experts estimate that half of medication is not taken as prescribed, meaning missed doses, wrong doses, or wrong medications.[45] Due to these adherence challenges, the majority of people fail to get maximum value from their medication. Proteus Digital Health is addressing this problem by adding sensors to oral medications and connecting them to the Internet of Things.

These connected medications are providing patients, caregivers, and healthcare professionals with new data streams. Proteus’ system unobtrusively captures exactly when people take their pills, and places that data alongside other physiologic and behavioral data such as heart rate, activity, and sleep patterns. Together, this information enables new methods of self-management and generates new insights to inform clinical decisions.

The Technology

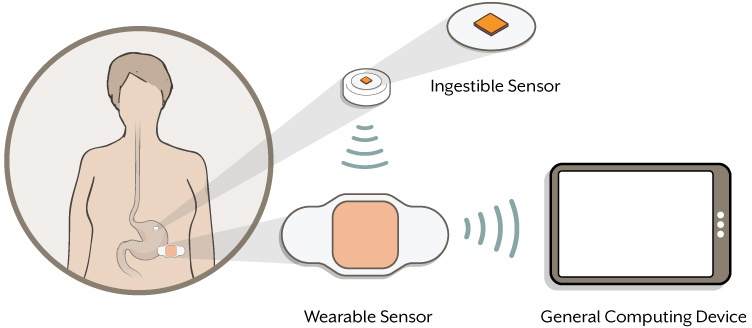

The system’s core innovation is a tiny and low-cost 1mm × 1mm ingestible sensor (see Figure 3-26) that can be placed into pills during the manufacturing process. This disposable sensor is designed to be fundamentally safe, made from elements typically found in the human diet. It is also invisible to the user, enclosed completely inside the pill, so the “connected” pill looks no different from a standard one. When designing the physical sensor, we felt it was important to maintain familiarity with the medication people are accustomed to taking, rejecting attachment methods that left the sensor visible.

The ingestible sensor communicates via a proprietary transmission technology to a small wearable sensor, developed by Proteus and contained within a small patch that is worn on the torso and replaced weekly. The wearable collects additional data such as activity and heart rate, and transmits everything to a mobile phone (see Figure 3-27). The phone then sends the data to the cloud, where it can be analyzed and accessed via secure web portals and apps. The apps can be tailored to different use cases and optimized for different users. People have different uses for the information: patients manage daily care, personal caregivers gain reassurance about their loved ones, nurses triage who needs immediate attention, doctors inform their clinical decisions, and healthcare administrators dig into their population’s trends.

It was also important to design a service that enabled the technology to launch successfully. We initially had two service design goals: (1) lower barriers to using an unfamiliar product, and (2) accelerate our learning about how we can improve our product. To address these goals, we invested in hiring fulltime “coaches” who were responsible for visiting early customers in their homes to help them use the system, and also to report back about their challenges. This investment has been critical, enabling us to quickly identify and fix product pain points. As the product becomes easier to use and customers become more confident with the new technology, we expect to shift to a more cost-effective and less resource-intensive service model.

One of our early design tasks was to figure out who needs to access what data and how. The data generated by Proteus can be used in a variety of contexts for myriad reasons. It was key for us to narrow in and focus on just a few use cases to start.

Our business team identified a set of potential markets. Then, to define the product offering, our design research team visited potential customers in those markets in their homes or clinics and carefully watched for their deepest challenges, listening for the specific questions that Proteus could directly answer. Using these learnings, our interaction designers created potential information visualizations in the form of static screenshots that we brought back into the field for feedback (see Figure 3-28). While our early prototypes displayed lots of data—exhibiting the breadth of the system’s capabilities—the feedback we gathered drove us to instead implement information visualizations focused more directly on the questions asked, leaving a large amount of the data unused. We found that providing too much data generated noise that was counterproductive to helping people maximize their benefits from using the system, especially in the early stages of establishing a “culture of use” with the new technology.

Early Use Case 1: Caregiving

The technology is well suited to help caregivers stay abreast of fragile family members from afar. We met with families and listened to their stories. The main need we heard from caregivers was knowing whether mom took her morning medications and made her usual sandwich at 2 p.m. Mom’s main need was to maintain dignity. Our information visualization for this use case involved a simple ribbon that leveraged medication-taking and activity data, allowing a family to see a high-level overview of a loved one’s pattern throughout the day (see Figure 3-29). So, for example, a family would know that mom was up and about at the time when she makes her usual sandwich. The visualization avoided clinical data such as heart rate that did not provide immediately meaningful insight to family members and had the potential to invade mom’s privacy in this personal use case.

Early Use Case 2: Informing Hypertension Treatment

The second use case involved helping physicians determine why hypertension patients presented with uncontrolled symptoms. Doctors have little insight into whether a patient is uncontrolled due to not taking medication or due to being prescribed the wrong medication. After using the Proteus system for two weeks, the physician can access a succinct report that answers two key questions: did the patient take the medication, and is the condition now under control? Activity data was not included in the report, as it was not useful in answering the physician’s key question. Most patients will take medication as prescribed during the observation period due to the Hawthorne effect—the awareness of being observed changes a person’s behaviors for a short duration of time—so the clinician now has verified adherence and an indication of whether the drugs are working when taken. This combination provides actionable insight that helps a clinician decide between adherence counseling or escalation to the next line of therapy.

Discussion

The focused use cases were critical in building early trust within the market. It is difficult for people to immediately accept new technology, especially technology made intimate by the fact that it is swallowed. We fostered trust by demonstrating to the market that we were striving to understand our customers and directly address their needs, without clutter and unnecessary invasiveness. We were solving real problems for people.

Additionally, the early use cases were forgiving to potential faults that a new technology might experience when first released. Fault resilience was a critical criterion in selecting where to start. The system uses a standard mobile phone to transmit data, and we knew the phone would sometimes be apart from the user (so unable to gather data from the wearable), out of range (so unable to transmit data to the cloud), or off (neither gathering nor transmitting data). Additionally, while we were able to shift to continuously flowing data from the wearable to the phone when Bluetooth Smart became available (with standard Bluetooth we could only transmit data periodically), there is currently no way to have a continuous data connection from the phone to the cloud while maintaining a full day of battery use on the phone.

To mitigate, we designed our wearable to store an entire week’s worth of data, in case the phone was never in range. We also designed a smart data push system, so that connectivity between the phone and cloud was triggered by key events, such as medication detection, making the system feel more continuous than it really was. Most importantly, we consciously looked for use cases that did not require highly accurate in-the-moment information—both use cases cited earlier are focused on trends. We built trust by launching a product we could guarantee works as expected, rather than launch a product with a high risk for reliability issues. As continuous data connections become more robust, we expect to have a host of additional use cases to explore.

Trust also comes from immediately establishing the right mental model about a new technology. When hearing about a new product, people often form immediate misconceptions. We had to get ahead and help people quickly establish the right models. The ingestible sensor, for example, uses a proprietary transmission technology that only works with the wearable provided by Proteus. This makes the system inherently secure and private, but a common misperception is that people will be emanating signals that anyone can pick up whenever they take their connected medication. We helped people understand from the first moment of interaction how the system is fundamentally designed for privacy, explaining not only our use of a proprietary transmission technology but also the advanced security protocols used by the databases and applications.

Proteus is passionate about solving the difficult problem of helping people maximize the benefits of their medications. A broad range of expertise is required to address such a difficult problem as well as to create a connected product. Connected products are not as simple as a standalone app or a novel piece of hardware. They are all that, and they have to integrate seamlessly into the lives we live.

At Proteus, the complex design team includes UX/interaction/UI designers, industrial designers, graphic/visual designers, packaging designers, and a design research team. Every designer on the team is professionally “T-shape”—meaning great skill and depth in one area of expertise, as well as breadth across design disciplines, allowing close collaboration with fellow teammates. The team is also deeply focused on collaborating across the organization. First, designs without champions in the product and engineering organizations are not particularly useful, and second, with such a complex product that contains many parts, everyone involved needs to be passionate about serving the needs of our customers.

In order to create truly groundbreaking IoT products, we embedded a sensitivity for users throughout the organization. We nurtured user champions outside the design team, training anyone interested in how to conduct user observations and bringing them along on field visits. We also educated the organization widely, ensuring that all of our collaborators knew how our team could help. This focus on collaboration, both within the design team and more broadly, is a critical component to creating complex, new-to-the-world products that have a chance at successful market adoption.

[30] Jakob Nielsen, Usability Engineering. Morgan Kaufmann, 1993.

[31] BERG, 2013, Cloudwash http://vimeo.com/87522764.

[32] This doesn’t necessarily mean that it will be easy to get the devices to work together in all the ways that you want, as the different standards may support different types of behavior in different ways. But it does mean you can connect them to the same system and talk to them via a single UI. For more detail on designing for interoperability, see Chapter 10.

[33] This is the TCP/IP model. The more comprehensive OSI model sets out seven layers. But for our purposes, the simpler TCP/IP model is enough to understand how the Internet works.

[34] Although configuring WiFi on devices with limited user interfaces can be awkward. Chapter 12, contains detailed guidance on WiFi setup.

[36] In conversation

[37] This technique of sharing a single IP address is called NAT: network address translation.

[39] A minority of connected devices may not have a remote centralized Internet service. For example, many WiFi printers have their own embedded web servers and thus host their own Internet service. But this is relatively uncommon in IoT.

[44] And, as with third-party platform providers, they may go out of business.

[45] World Health Organization, “Adherence to Long-term Therapies: Evidence for Action.” Accessed December 2014, http://bit.ly/1F68Jra.