1

Introducing Urban Humanities

The city is the social, physical, and political terrain of our collective lives, where we live in geographic proximity to people unlike ourselves, negotiating the varied understandings that com-prise our coexistence. This definition of the city pertains as readily to historical as well as contemporary examples. However, the intensifying transnational urbanization, globalization, and immigration flows of the last decades have accentuated interactions, contestations, and negotiations of diverse bodies in urban settings.1 Commuters, tourists, public housing tenants, civic leaders, parking attendants, business owners, migrant street vendors, Skid Row residents, school teachers, downtown cops, and corner drug dealers often rub shoulders in cities, articulating daily life in relation to physical spaces. This cosmopolitan congestion produces the friction to spark debates about various social, economic, and cultural issues, and these spatial politics most often play out in the city's common grounds. How space is understood, articulated, and regulated has a lot to do with how we interact in it.

Consider urban streets. In ancient Pompeii, cart traffic into the forum was blocked by large stones to afford both commerce and political discourse among citizens. Nineteenth-century arcades were fundamental to the creation of a vibrant Parisian street life, where strangers encountered one another in public, and consumer life blossomed. Built in 2017, Grand Park in downtown Los Angeles offers Angelenos from different walks of life a common ground for coming together to celebrate or protest. In each instance, a loose or coordinated consortium includes residents, visitors, writers, planners, and politicians who together braid stories about how to imagine, interpret, claim, and act within the city they share. Contested urban space and spaces of resistance also define a portion of this spectrum, as when the French Revolution flourished behind street barricades, the Occupy Movement presented itself to the world in Manhattan's Zuccotti Park, or Tahrir Square became the epicenter of Cairo's Arab Spring. In each instance, the public sphere of street and square situates collective life, inscribing potential for political interchange that in turn recomposes the metropolis.

The city has always been a social, spatial, and political terrain, where we coexist in continuously negotiated spaces, often (though certainly not always) marked by shared histories, narratives, and meanings. However, in the last decades, new urgencies demand our attention, as cities have become the transnational home to the majority of the world's population. These urgencies include vast disparities of wealth that create social tensions in urban settings, migrations of economic and political refugees, and affordable housing shortages globally.2 At the same time, the world's cities produce and experience environmental crises that range from climate change and sea level rise to industrial pollution and toxic air quality.

Rather than rehearse alarmist refrains, these conditions serve as the groundwork for urban humanities, an emerging field and a new approach for not only understanding cities in a global context but also intervening in them, interpreting their histories, analyzing and engaging current circumstances, and speculating about their futures.3 Urban humanities deploy urban studies, design, and the humanities to interpret and intervene in the city through engaged scholarship attentive to the settings of everyday life. The perspectives, interpretive practices, and content of the humanities are enriched by their interaction with those of urban planning and architecture, while the practices of architecture and planning are enhanced by their interaction with humanistic approaches that ground design, speculation, modeling, and intervention in the complex cultural-socio-historical networks that compose the urban.

Defining Urban Humanities

If we have hinted at our understanding of the urban, what then are the urban humanities? We begin this chapter by dwelling a bit longer on the constitutive concepts of this combined term. As a modifier, the “urban” in the “urban humanities” connotes a humanistic inquiry that is specifically centered on the city. This includes the cultural expressions created in cities, their social forms and structures, ethnic and racial composition, and varied and multilayered histories, the languages spoken and linguistic expressions of inhabitants, as well as the built and lived spaces. This inquiry is pursued through the many media forms (including literature, photography, film) that help to make sense of the city and its people, but also through direct interaction with them. By and large, this is a pedagogy of the city attuned to both the empirical and the interactive but also the representational forms that tend to be the way the humanities have conventionally approached the city—that is, by focusing on the reading and interpretation of its representations (i.e., “the city as text”).

However, “urban” need not just modify “humanities.” Rather, the term also connotes a new collective singular, a linkage defined by the productive and sometimes precarious tensions between the two constitutive terms. As a productive tension, neither term is overcome by the other. Instead, they exist in a push-and-pull relationship, in which new possibilities and potentialities are opened up for both the urban and the humanities by virtue of their coming together. In this respect, neither term is static or impermeable. The “urban humanities” emerges as a sublated, third term without, however, losing the elemental components of the urban and the humanities in the dialectical process. In many ways, this is the same logic that provides the dynamic intellectual and pedagogical framework for other new critical, experimental, and praxis-oriented interventions, such as “digital humanities,” “environmental humanities,” and “medical humanities.” 4

In each case, disciplinary formations that had been outside the conventional purview of the humanities (perhaps because of their methodological approach, content, professional ambitions, or pedagogies) are now defined by their intersection with the humanities. Far from “correcting” or merely augmenting the humanities, urban humanities (like digital, environmental, and medical humanities) bring the critical lineages, interpretive paradigms, historical depths, comparative cultural analyses, and ethical orientations of the humanities to bear upon the city (just as digital humanities, for example, do this for computation and digital technologies). What this means is that each of these “hyperobjects”—the city, the digital, the environment, medicine—to use Timothy Morton's coinage to refer to objects of study characterized by vast temporal and spatial dimensionality and complexity5—are conjoined with and interpreted, however provisionally and partially, by the critical practices of the humanities.

At the core of the humanities are, of course, human beings—with all their diverse and embodied cultural expressions, per-spectives, languages, and histories. This is what the humanities study, interpret, and value. They do so through methods of interpretation and critical inquiry, which provide historical context, situated perspectives, and comparative frameworks for under-standing and also exposing various epistemologies, ideologies, value systems, structuring principles, and world views. At the same time, the humanities are attentive to media form and media specificity, as form cannot be dissociated from content. In this sense, humanistic inquiry is also design-oriented because it opens up spaces for the imaginative, the speculative, and the future-oriented. The humanities are not just a retrospective analysis of the remains of the cultural record (the archive, the wisdom of the past, the archaeological artifacts of the past), but can be—and we argue, should be—attuned to futurity, the possibility of justice, reparation, and perhaps even redemption. As the German-Jewish philosopher Walter Benjamin famously said in a context of great historical urgency, as he fled the advances of the Nazi army: “We [human beings] have been endowed with a weak messianic power” by which the past makes a claim on both the present and the possibilities of the future.6 For urban humanists, we see this transformative potential—grounded in and emerging from the injustices of the past—to be oriented toward the possibility of spatial justice. At the core of urban humanities pedagogy, then, is the ideal of spatial justice—a concept we will return to later. But to orient our pedagogy toward this ideal, we must first recognize and break from certain entrenched traditions that have tended to isolate the university and cut off the humanities from other disciplines (especially those in the social and applied sciences, as well as in schools of planning or architecture).

While there have been many calls for reform in the humanities (especially in graduate education), very few programs have made substantive changes beyond shortening the time to degree and supporting “alternative” professionalization opportunities outside the academy.7 Perhaps this is because the humanities tend to be isolated from other disciplines and programs at the university. If we look beyond the humanities to the medical sciences, engineering, the applied social sciences, and other professional schools such as architecture, it is not uncommon to think in terms of “grand challenges” or “big problems”: a cure for a disease, energy independence, global health, clean water, just cities, and so forth. These are not only big problems but ones that require years and years of effort to solve; they require many people from various disciplines to work collaboratively, including generations of scholars, often in labs and studios, and collaborators from public policy, the nonprofit and for-profit worlds, government, philanthropy, the arts, and more. The work takes years, perhaps even decades, to carry out. The research proceeds incrementally and may, in fact, fail. Nonetheless, it is cumulative, with students coming in, working in labs and studios for short periods of time, receiving their degrees focused on elemental aspects of the research process, and moving on.8

In the humanities, scholars tend to approach things exactly the opposite way: with ever smaller, ever more specialized problems, addressed by single individuals almost always working in isolation, with the highest achievement being a dissertation monograph. In fact, almost everything in the humanities is set up to support scholarship in isolation: individual achievement is valorized; single-authored texts are the norm; and even office space is organized by separating scholars from one another. While these practices may come from a tradition of fostering thoughtful (even monastic) contemplation and individualized writing, it means that collaborative, experimental, and speculative research is the exception in the humanities, and students are hardly ever brought into the experimental research process as partners and co-contributors.

What if we turn this approach on its head and ask, instead: “How can a hyperobject like the city be studied and taught? What would it mean to address this challenge with generations of students, who would work with faculty as well as outside collaborators—across multiple disciplines and institutions—to come up with ways to understand, address, contextualize, and respond to the challenge of spatial justice?” The idea is to think at many different scales at once—from the biggest to the smallest, in as many different directions as possible, with as many different methods and people as possible. To give a more concrete example: How might we compose a comprehensive history of immigration to a city as complex as Los Angeles? It would need to treat the topic historically, geographically, socially, culturally, economically, and architecturally; it would focus on issues of race, global histories of nation-states, technologies of mobility, assimilation, identity, public policy, gender, policing, and representations of difference and otherness; it would be multilingual, transnational, and multimedia; it would involve a multitude of voices, perspectives, languages, narratives, and neighborhoods. It would have primary materials, translations, annotations, commentaries, interactive media, historical analyses, datasets, interpretations, and maps; it would be a forum for debate and the development of public policy, a resource for courses, and a collaborative site for reviewing scholarly research of all types. It would be an integrated, open-ended, and collaborative research product with contributions by many students and faculty from various departments, disciplines, organizations, and institutions, especially ones outside of the conventional contours of the university. And it would potentially take scores and scores of researchers and participants decades to do well.

As new multidisciplinary fields such as environmental human-ities, digital humanities, medical humanities, and urban humanities gain traction, we are starting to see research configurations in the humanities that are not based on, limited to, or derived from traditional departments. These configurations are not simply interdisciplinary by virtue of their subject matter or the descriptive modifiers attached to the humanities (as in doing the humanities digitally); instead, they introduce new conjugations of humanities research with the methods, tools, analytical techniques, and content of other disciplines. These configurations lead to different kinds of research questions, in terms of scale, method, content, participation, and output.

How can a single department or discipline possibly provide the range of expertise needed to investigate a phenomenon as complex, say, as the emergence of the Anthropocene and the impact of human activities on the earth's ecosystems, biodi-versity, and climate? An emerging research configuration like environmental humanities responds by bringing climate scien-tists together with literary scholars, information architects, geographers, biologists, and historians. Other new configurations such as urban humanities are also needed to study the cultural, social, and architectural histories of megacities, where some 10 percent of the earth's population now resides. How can we respond to the grand challenge of designing and building a more just city without such a plurality of perspectives and expertise, not to mention partnerships beyond the walls of the university with nongovernmental organizations, city councils and regional governments, developers, museums, artists, schools, and countless other cultural and social constituencies? These are “big projects” that combine deep criticality, interpretation, and transhistorical, comparative perspectives with speculative, experimental, and projective problem-solving. And, more than that, they represent the “translational” public potential of the humanities, the applications of humanities knowledge far beyond the tiny group of specialists who typically encounter and care about humanities research.

It is clear that the old configurations of humanities departments as siloed entities—largely stratified by medium, period, and genre—make no sense at all for asking and answering these big urban questions. The conventional model not only is parochial but also facilitates a very narrow band of research questions that are ever more specialized rather than opening outward to comparative questions and real-world applications that cut across geography, period, language, medium, method, and institution. Our contention is that we typically expect humanities students to do siloed research and individual scholarship, on highly specialized topics, without putting these specializations together to form constellations or large-scale, collaborative projects. In contrast, we believe that we need to encourage the building of “aggregations” of knowledge that have broader application, involving partnerships with communities, with potentially global diffusion.

As we will argue here, a radical reimagining of the humanities has the potential to achieve a number of things: Foster inte-grated, collaborative research that embeds specializations and individual research into a significantly broader, multimodal, and interdisciplinary research context; create new paradigms for recruiting, mentoring, and training students; be a productive response to the “crisis of humanities” by providing a model for engaged, broad-based, collaborative, public humanities scholarship; and, finally, transform the scale, duration, impact, and public resonance of humanities scholarship by placing collaboration, co-creation, speculation, and experimentation at the core of the student experience.

Far from excusing the variety of disciplines outside of the humanities, which have had a history of looking at “big problems,” our project seeks to breathe life into these spheres as well. We don't use this language metaphorically: while these disciplines—namely architecture, urban planning, and the social sciences—have a rich history of examining social ills and proposing bold solutions to these ills and can hardly be thought of as monolithic in any way, the past thirty or so years of social science research have tended toward the numerically quantifiable and the abstraction of human life. As the hegemony of econometrics has spread through planning, policy studies, and the gamut of social sciences to better interface with a global system of capital that translates human relations into an abstract economic calculus, fundamental questions regarding human existence, values, culture, and lived and sensed experiences have often taken a back seat.

Architecture, on the other hand, like the larger world of cultural production of which it is a part, fluctuates between an identification with avant-garde arts and its intrinsic connection to social concerns. While architecture has origins in the technical and applied arts, beginning in the 1970s and coincidental with the expansion of doctoral programs in architectural history and particularly theory, architecture sought to strengthen its roots in form-based logics. This led to a focus on internal or autonomous disciplinary questions like its critical history, its particular practices, the specific nature of architectural drawings, and the development of abstract form. Peter Eisenman's House VI (1975) (figure 1.1) was the “take no prisoners” primary object of architectural autonomy, with its demonstration that form did not emanate from function (for example, columns in House VI were not structural and didn't even meet the ground in one case).9 Subsequent developments of architectural theory's impact on practice were varied, but tended toward abstraction, formalism, and discourse rather than social and political engagement. Thus, while the econometrics approach of the social sciences and the formal approach of architecture could not seem more distantly related, the two have striking similarities.

1.1 House VI by Peter Eisenman, 1975. Credit: Gerrit Oorthuys

There is, of course, a counter-history to these dominant narratives, and even more recent undertakings point toward a reversal of which urban humanities are also a part. A book that has received a lot of attention in urban planning and the social sciences is Matthew Desmond's Evicted, an intensely focused ethnography, which narrates the everyday struggles of those caught up in an increasingly broken housing system.10 And the past few laureates of the Pritzker Prize have included Alejandro Aravena who has developed low-cost social housing in the Global South, and B. V. Doshi who has also worked on low-cost and sustainable housing in India. The field of urban humanities similarly turns its attention toward the aspects of human life that have long been the focus of the humanities, bringing the gaze of architecture, design, urban planning, and the social sciences with it. While attempts to address the “grand challenges” of our day should be celebrated, these efforts that often bring together so much of the quantified and abstracted world will be for naught if at the end of the day we forget about the person standing at the receiving end of some supposed “grand solution.”

Urban humanities employ a set of practices and strategies to enter this bidirectional move—from the intensely focused humanities out toward the larger world, and from the bigness of architecture11 versus the even more macroscopic view of the urban from the social sciences toward the micronarratives of embodied human beings. Our positionality within a university context necessarily forces us to contend with our biases, not the least of which is reproducing the tendency toward the very academic, abstract theorization, which we critique. Thus, while in our work and throughout this volume we return to sources of inspiration, which are often academic and theoretical, we also strive toward building urban humanities out of the projects of creative individuals such as political organizers, artists, and practitioners, but most of all through the on-the-ground practices that we have deployed—sometimes intentionally and other times unexpectedly—through a process of collaborative, iterative, and reflective inquiry. This “emplacement,” or the operative frame that privileges knowledge, learning, experience, and creation, occurs in relation to specific places, and even within specific places, and is a fundamental driver of our particular formulation of urban humanities. As such, it is important to consider the specificity of our project as emanating from UCLA and Los Angeles, in particular.

Looking Out from Los Angeles

Urban humanities were born in Los Angeles. Our views emanate from an academic setting on the “Left Coast,” at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). But our work, however emplaced, is not focused only on our own backyard. We see contemporary urbanism shaped through processes of negotiation taking place in the settings of everyday life, which are plugged into a global network of cities, mediated through information and communication technologies, and constructed by flows of capital, but also by individuals, their collectivities, and cultural practices.12 In fact, Los Angeles acts as a foil to consider cities around the globe. While we deem urban humanities useful and applicable for cities worldwide, this book describes our interconnected research projects, experiences, and collaborations in megacities of the Pacific Rim: Tokyo, Shanghai, Mexico City, and Los Angeles. It goes on, however, to elaborate those analyses in a broader array of cities.

These four Pacific Rim cities have their own identities and cultures, yet they also share what Lisa Lowe might term “intimacies” through curious linkages formed by migrations, investments, and interdependent histories. Urban humanities touch upon Lowe's notion of these intimacies across continents by “examining the dynamic relationship among the always present but differently manifest and available histories and social forces.” 13 As such, transnational urban studies are enriched by transnational humanist perspectives, giving body to otherwise abstract flows. And, as a practice that aims not only to understand and interpret, but also to engage and intervene, urban humanities see these intimacies as a demonstration of the instability in definitions of “home” and “away”: We often find ourselves at home in cities abroad and strangers in our own backyard, the vast landscape of Los Angeles.

The premise of urban humanities is that the city is a site of concrete connections and interactions in space. Therefore, the inquiries of urban humanities precipitate around the cultural artifacts of urban space and the micro-settings of everyday life—a housing project, a plaza, a six-lane boulevard, a gated community, a courthouse, a broken sidewalk, a mural-monument to life lost in a police operation—those are the spatial embodiments of histories, collective lives, intimacies, contestations, power relations, and social distinctions. These fragments of everyday life are influenced by larger forces, but also by subjective, human-scale realities that we as scholars, designers, planners, activists, and humanists have some capacity to affect.

This approach stands apart from the most recognized forms of urban study that precede it, in so far as it borrows from them all to produce a more powerful lens. Since time immemorial, authors have constructed remote locations for readers in literary narratives—from ancient Pausanias's portrayals of second-century Athens, to Baudelaire's and Benjamin's accounts of a changing nineteenth-century Paris. Over the last four decades, in response to critiques that such single-site urban biographies are too limited, parochial, and ethnocentric,14 comparative urbanism has instead flourished, triggered by a desire to compare, contrast, or juxtapose parallel phenomena that happen in multiple socio-spatial contexts and likely influence one another.15 But comparative studies also have been criticized as overly constrained by fixed entities and arbitrary divisions such as municipal or national boundaries. In reality, urban networks and influences are dynamic, diverse, and transcend such boundaries. The emphasis on comparison may also bring along the danger of homogenizing differences and disregarding local particularities in favor of extracting universal lessons to urban issues and problems.16

More recently over the past twenty years, a transnational perspective has gained favor in research on cities, responding to criticism that comparative urbanism suffers from a static perception of the urban.17 In contrast, transnational approaches focus on interdependencies, movements, and flows across borders in regions and subregions. This transnational, transcultural, comparative approach is also reflected within the humanities, particularly in cultural criticism with its emphasis on mobility, migration, border crossing, and hybridity.18 The human body—as national subject, traveler, migrant, refugee, or even as bare life19—stands at the center of such global abstractions and structures of power. By synthesizing these perspectives, of literary depictions of cities with comparative urbanisms from the social sciences, of global flows from transnationalism with the embodied emphases of the humanities, we find ourselves at urban humanities: studying global intimacies manifested in material culture and the human, everyday life interactions at urban settings.

With the expansion of global travel, the accumulation of digitally accessible foreign archives, the development of area studies in the university, and the wide circulation of international media, the study of places of “otherness” grows. The practices, pedagogies, and values of urban humanities arise from multi-pronged investigations in global cities of the Pacific Rim whose literatures, histories, geographies, and architectures do not lend themselves to Eurocentric cosmopolitan conventions, even under conditions of colonialism. Paradigmatic models of Paris, London, and New York are insufficient to grasp Los Angeles or Shanghai.

To illuminate urban humanities, the book features projects that come from our own research and teaching. These projects are the product of collaborations between scholars, community organizations, practitioners, and artists in the four aforementioned cities of the Pacific Rim. The projects are also theoretically founded upon and framed by work from other scholars, artists, and practitioners, often based in a range of other locales around the world. To provide a critical investigation of urban settings in cities, our projects focus on the spaces and artifacts of everyday life but also examine major themes found in contemporary urban settings, such as risk, resilience, spatial contestations of collective and individual identity, and the problematics of borders and migrations.

To study and interpret these complex issues situated in their socio-spatial contexts, urban humanities build a field of inquiry in which history, literature, architecture, art, and urban planning comingle to understand urban realities and respond to new urban challenges. These fused practices take place within scholarly settings of research and teaching, but also within contexts of shared experiences and community engagement beyond academia. These contexts occur in a wide range of urban social settings, from neighborhoods facing the threat of gentrification to streets and sidewalks upon which so much of daily life occurs.

Imagining a Future

In addition to the “situatedness” of our experiences and practices, two other values drive much of urban humanities: an acute attention toward the future and a drive to work toward spatial justice. Together, these values enable us, as the title of our volume suggests, to reimagine our collective life in the context of an increasingly globalized and urbanized world. Without spatial justice, attention toward the future, even with the best of intentions, has often resulted in disastrous consequences, such as the radical reimagining of urban cores that occurred during the middle of the twentieth century under the label of “urban renewal”—and this is but one narrative among countless others in the course of human history. While this vision of the future certainly held the promises of modernity for a select group, for others it was no future at all. Spatial justice demands that we ask why, how, and for whom? And the pursuit of spatial justice—the manifestations of a just world that often play out across spatial dimensions and within cities—with an eye only toward past injustices often leads to a hypercritical tendency to critique, deconstruct, and destroy those factors that have perpetuated these injustices. This pursuit is an important task, to be sure, yet one that all too often has left a void without consideration of reconstructing an alternative future, thus allowing further future injustices to happen. Jane Jacobs's appreciation for the city-as-it-is, calling out the destructive tendencies of modern urban planning, is an example that comes to mind; it certainly came out of a desire for a just city, yet its logical endpoint has landed us in our contemporary neoliberal city, with the seemingly universal traits of the lack of affordable housing, gentrification, and displacement. Only with both an attention toward the future and a desire for spatial justice can we truly and collectively imagine a future.

Most academic work engages with the past or the present through forms of historical and empirical inquiry. Yet by engaging with the city and by calling for spatial justice, we are necessarily thrust into the uncertain and unknown future. What kind of urban future might or ought to happen? What kind of future do we want, and for whom? What are the ways in which the future might be materialized, embodied, and spatialized? To engage with such questions, the urban humanist must gather data, narratives, and historical materials with the explicit mandate to imagine change and transformation. This is not a prescriptive practice mandating a specific future, but rather an expression of values and possibilities in the service of imagining a more democratic, equitable, and just future.

The few strains of scholarly work that engage the future systematically most often come from the professional disciplines of design, urban planning, and architecture, which envision projects and places to be built. Such work incorporates visions of urban futures such as Le Corbusier's Ville Contemporaine (1922), or Hugh Ferriss's depictions in The Metropolis of Tomorrow (1929), which Lewis Mumford called “utopias of reconstruction” (in contrast to utopias of escape).20 While the historical, interpretive methods of the humanities do not, in general, pertain to inves-tigations of the future or speculative design, the utopian imagination has a significant legacy that may be traced in works of literature, philosophy, art, and film. One need only mention Thomas More, Karl Marx, Vladimir Tatlin, and Fritz Lang, among many others. Lang's 1928 film Metropolis, for example, is a futuristic city marked not only by technology and speed but also by overcoming some of the greatest social and economic disparities.

Such total, utopian visions from the mid-1800s to the 1920s atrophied with the postwar retreat from cities to suburbs and the catastrophes of urban renewal in the 1960s and 1970s. Other strains of a future-oriented sensibility have found ground in creative fields, such as sci-fi artistic practices or speculative literature. The field of urban humanities calls for renewed scholarly attention toward the future, not as a totalizing, alternative regime but with an emphasis on spatial justice, and terms the necessity of such work “the generative imperative.” This term also suggests the project-based orientation necessary for such work: urban humanities are organized around collaborative projects with material outcomes.

The initial foray into speculative work is one oriented toward setting agendas and framing questions, as well as outlining actionable projections. By engaging in fictions and narratives about what could possibly come, and by pushing these experiments to the edges of our imagination, we create the capacity to expand what is conceptualized as possible. This form of projection is akin to the exploratory artistic practices that Jacques Rancière has identified as providing fuel to expand the collective imagination.21 We term this “immanent speculation” to preclude the decontextualized and ahistorical tendencies, which gave rise to the tabula rasa approach of 1960s urban renewal. These projects necessarily emerge from socio-spatial contexts, site specificity, and conditions immanent to the place in question. Thus, projective urban humanities work is always grounded in real places, interacting with the real people who inhabit them, in order to create engaged, responsible answers to the elusive questions about the future.

The value of spatial justice compels the urban humanist to act—action that defines an engaged scholarship and pedagogy of a different sort from those drawn from existing models of community-based research, service learning, and the like. Spatial justice is not necessarily a better form of justice; rather, it is a lens through which particular injustices are made visible in cities. So many of the greatest problems of cities, from environmental harms, to economic impoverishment and hunger have been chalked up not to any intrinsic and unalterable natural law, but merely to an inequitable distribution of resources and amenities. The urban humanist sees these problems as socio-politically constructed and spatially manifested.

While drawing upon the long literature regarding the “right to the city,” as espoused by Henri Lefebvre and David Harvey,22 our jumping off point is much closer to home: the critical geographer Edward Soja, who wrote one of his final volumes on the topic of spatial justice, grounding it in his experience of Los Angeles. In Seeking Spatial Justice, Soja describes the necessity for consideration of the spatiality of justice, not only because space acts as a political mechanism for the production of injustice, but also because a consideration of space opens up tools for social and political action.23 To date, however, this effort has been grounded largely in the social sciences. By privileging actions and cultural artifacts of people in their urban settings, and working towards concrete spatial alternatives, urban humanities present a means for the incorporation of “other” marginalized topics and voices in order to expressively undertake new practices that work toward mending spatial injustices.

If urban humanists are to address the spatial injustices in cities, their locus of action will inherently transgress disciplinary, hierarchical, and geographical borders. Urban humanist scholars produce knowledge collaboratively not only across academic disciplines from the humanities, social sciences, and design, but also with other actors in the city, be they community members, policymakers, artists, or activists. In this regard, the research and pedagogical practices of the university are knit within a broader environment, not isolated from the city and outside organizations but, rather, in connection with them. This form of engaged scholar-ship and pedagogy introduces nonhierarchical, self-reflexive, and sited pedagogies to known practices of community-based research and learning, forming the basis for a series of new, exploratory research practices.

First, the researcher is a subject among subjects, in a non-hierarchical relationship in which collaborative practices contri-bute to a shared creation (e.g., a project, an event, a performance, a speculative design, or a report). The term “researcher” as deployed in community-based research may even be obsolete; terms such as “student” or “participant” may be more apt, but even these have their shortcomings. To play out one example, an urban humanist scholar might bring her research tools of mapping and ethnography to the community arts director who brings her practices of teaching and public relations, and together they collaborate with a community to concoct an appropriate plan for an arts center in the local park. Yet while the outcome of this plan is certainly beneficial, the process through which it was developed may have produced new networks of collaboration, experiences, and observations that would yield new knowledge of their own right, and reconfigured power relationships between expert and layperson, or between resident and visitor. Indeed, this example is based on several urban humanities projects undertaken in Mexico City and Los Angeles, which will be discussed in more detail in later chapters. Our current understanding of such engaged scholarship reflects this binational experience.

The commitment of urban humanities to academic scholarship suggests its own practices.24 Prior to fieldwork or engagement, researchers study a place and its people through literature, film, arts, architecture, and history. The range of advance materials and experiences not only prepare, but bias researchers in self-aware and self-critical ways. Acknowledgment of our own subjectivity and positionality (in the context of collective, multidisciplinary teams) is fundamental to cultivating a generation of creative practitioners in urban humanities.25 Further, attention to the positionality of others within a collaborative network, and the power relationships that define this network, are critical for producing work that can legiti-mately respond to spatial injustices. As such, an ongoing process of self-reflexive learning and project modification is necessary and, moreover, can yield creative insights into new project directions.

In addition to such traditional scholarly practices of reading, archival research, or formal analysis, new types of scholarship are evoked that are rooted in place, action, interaction, materiality, and community. Such sited engagement is important for grounding projects, and also for practices that demand spatial learning, reflection, and response. To extend Soja's arguments about the role of spatiality,26 spatially specific engagement provides learning and tools that are capable of identifying and responding to those injustices arising from situated forms of injustice or oppression. This grounded learning emerges from site-specific practices such as fieldwork and spatial ethnography, which form the substance of urban humanities as developed in situ—a way of practice in the city, which we see as distinct from academic methodologies, as conventionally understood.

Practicing Urban Humanities

Urban humanities call for scholarship to be augmented by practices that directly engage with people and places, which in turn provokes questions about values. Why do we engage in these practices, and for whom? What assumptions lie behind them? The foundations of urban humanities rest upon three main values: spatial justice, an imperative to speculate about the future, and pedagogy supporting engaged scholarship. These values are expressed through a set of “fused” practices of scholarship, some of which we have developed in depth (and will be discussed later)—including thick mapping, spatial ethnography, and filmic sensing—while others remain in an experimental form, waiting for other interlocutors to take up their development. We identify these practices as “fused” because they are interdisciplinary, collaborative, and oscillate between process and output.

Given our transformed understanding of the contemporary city, and the values deemed necessary for ethical engagement with socio-spatial settings, existing disciplinary strategies for scholarly and professional work on cities often seem inadequate. For example, methods from urban planning and the social sciences generally rely on economic and quantitative analyses of neighborhood change, ignoring the symbolic, communicative, and cultural elements that also underlie change. Or a humanistic interpretation of changes in the same neighborhood may lack the data-driven evidence that may have the potential to influence policy changes. Moreover, urban understanding is grounded, sometimes tacitly, upon conventions emanating from the study of Eurocentric, postfordist models.

Our fused practices seek to address these shortcomings, though we would hardly claim that they have fully succeeded. Instead, they remain under constant modification, contextualization, and improvisation, given the particularities of a site and a cir-cumstance. Their fusion is part of this process, occurring through the combination of researchers, collaborating across distinct positionalities. This connotes a networked and capa-cious formation of diverse individuals, who come together in common collaboration. These individuals come from a variety of disciplinary backgrounds with expertise in different research practices, from community-based organizations responsible for putting knowledge into action to disparate representational and communicative traditions that have the capacity to bridge scholarly, artistic, and practical media. Our work in urban humanities has brought together, for example, designers and architects, social scientists, literature and film scholars, and urban planners in collaboration with civic agencies, community groups, and nonprofit organizations. Communicating across such a diverse spectrum of individuals is helped by a grounded, action-oriented, site- and project-specific approach.

Fused practices of scholarship are necessary for understanding and intervening in the complexities of contemporary cities—no single discipline can fully claim ownership of a condition as vast and complex as the urban. This is overwhelmingly apparent in the megacities of the Pacific Rim. Therefore, a significant portion of this volume is dedicated to describing, unpacking, and demonstrating these practices. Fused practices deviate from past, exhausted discussions on interdisciplinarity and abstract conversations on how to bridge siloed scholarly work. Rather, they place emphasis on action-oriented, situated practices in order to engage with contemporary urbanism.

The term “practices” is more appropriate than “methods” for several reasons. First, grounded and exploratory, such practices are developed in situ, and lack the precedent and fixity that come with long-established disciplinary methods. This is not a problem, but rather allows for openness, flexibility, and responsiveness to the shifting goals of a project, or the surprises that arise amid new collaborations. Second, these practices are a fusion of research, representation, and action rather than fully instrumentalized methods that lead linearly from research questions to findings. Third, practice theory argues for the subject's agency in the contexts of broader, collective systems. The fused practices of urban humanities explicitly restore agency to engaged scholars and maintain the deep intersectionality of theory and practice.27

The practices introduced here (and examined in depth later in the volume) are not an exhaustive list but are representative and applicable beyond the particularities of our specific collaborators, projects, identities, skills, and places. These practices share several defining traits. First, and most clearly, they shift among research method, experimental scholarly output, and instrument for action; while they may manifest as more strongly one or the other, they are always much more than simply a data collection method. Second, they critically engage with forms of media, rethinking how we see, communicate, understand, and possibly transform the city. Third, they are fundamentally collaborative and project-based. And fourth, they are site-specific and embodied, examining practices of everyday life attuned to the positionality of the subject.

If we had to describe urban humanities with a single word, that word might be “thickness.” Urban humanities “thickens” our understanding of the urban by unearthing the different layers that not only constitute its cultural and historical density, but, more importantly, also propel us into the future in ways that are grounded yet open-ended. Thickness goes beyond “more data” or “more layers” of information; it bespeaks a practice of adding complexity, voices, and perspectives, thereby eliciting productive tensions that enable new, speculative possibilities to emerge.

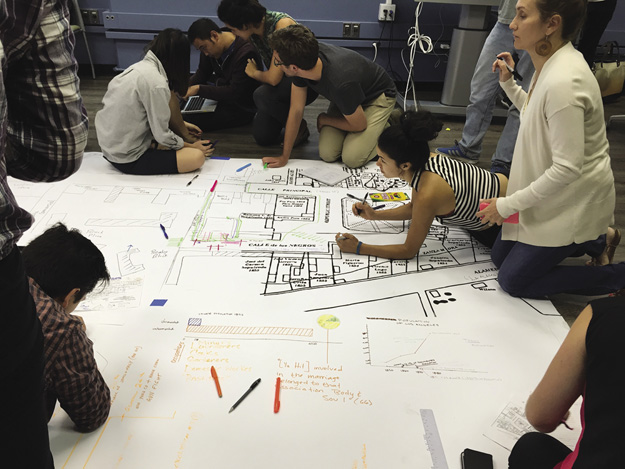

Contemporary cities like Los Angeles or Shanghai seem to elicit the construct of thickness because of their sheer size, complexity, and historicity. Building on the ideas developed for the Hyper-Cities digital mapping project by Todd Presner, David Shepard, and Yoh Kawano, “thick mapping” in the urban humanities is the process of composing a multilayered, multitemporal, and propositional spatial representation that foregrounds multiple voices, perspectives, and narratives.28 Echoing Clifford Geertz's argument for the development of “thick description” 29 as an approach to ethnographic practices attuned to stratification and micro- and macro-level accounts and the construction of all narratives, so too is thick mapping an urban humanities practice for probing, narrating, and representing the city's spatial and temporal dynamics (figure 1.2).

1.2 Students working on a thick map of the Chinese Massacre of Los Angeles in 1871. Photo credit: Authors

Thickness is an attribute that is fundamental to all urban humanities practices. The central goal is to synthesize positivist and empirical modes of the social sciences with the embodied, speculative, critical, material, and ethical sensibilities of architecture and the humanities. Thickness moves beyond a singular or definitive reading, which is a “thin” approach to knowing and being. Rather, thick media incorporate—and perform—multiple readings and histories; they combine polyvocality and contestation in ways that create a greater whole without erasing what might be construed as conflictual or incongruent realities. Thick mapping, thus, takes the cartographic medium, long understood as an objective, scientific representation of the world based in geographic norms and state power, deconstructs it by exposing its assumptions and structuring epistemologies, and layers in the messy reality of humanity, culture, and history. The thick map takes on qualities of a spatial narrative to tell surprising stories of unfamiliar cities.

We intentionally use the verb “mapping” to specify process, namely the incorporation of the range of practices involved in spatial data collection, visual representation, construction of narratives, and iteration, not to mention the deployment of a thick map in the service of political engagement, knowledge production, and policy development. Thick mapping is a practice not limited to the singular goal of a scholarly output, but also involves learning, teaching, and engaging. Thus, urban humanities work depends upon research as well as new pedagogical practices that incorporate collaborative and shared mapping in the classroom and in the field in order to see, create, and act anew. In the words of landscape architect James Corner, we pursue mapping to “emancipate potentials, enrich experiences, and diversify worlds.” 30

Spatial ethnography is another fused practice of urban humanities. It is grounded in the scholarly methods of spatial analysis (coming from geography, urban studies, and architecture), and in ethnography (primarily originating in anthropology and to a lesser extent, history). It merges these research methods with considerations of narrative, media, and fieldwork. The most central element of a spatial ethnographic practice, however, is the process of urban humanities fieldwork, construed in the liminal space between anthropological observation and the architectural site visit. Transnational metropolitan studies incorporate anthropological methods in which a researcher is immersed in an unfamiliar cultural setting in order to observe, experience, form thicker descriptions, and construct more compelling narratives.31 At the other extreme is the site visit, common in architecture, planning, and urban design where an outsider relatively quickly assesses spatial and material qualities of an unfamiliar place. This location-specific investigation involves measurement and data gathering more often through immediate means such as mapping, sketching, and photography. Together, the practices of anthropological observation and the site visit inform the fieldwork undertaken by urban humanists. Fieldwork as defined in urban humanities quickly exposes suspect “othering” of geographies and communities, as well as cultures. Far from “parachuting in” to identify and fix a problem, the urban humanist engages communities, builds relationships of trust, and collaboratively generates possibilities.

At its most elemental, spatial ethnography is a practice of observing, describing, and analyzing situated cultures or people with particular regard to their spatial context. This can be as simple as georeferencing ethnographic information, allowing for anthropological investigations to identify spatial patterns. But spatial ethnography within urban humanities is laden with implications beyond this straightforward tweak to ethnography—and many of these implications stem directly from the fraught history of ethnography within anthropology. The “object” of analysis is never just “out there” but is very much constituted by the positionality of the subject who brings her worldviews, epistemologies, languages, sensitivities, and biases to any practice of representation. Moreover, “space” is hardly a fixed object or container for investigation, as spaces are always dynamic, fluid, mutable, and multiplying.32

Scholars from sociology and urban studies have deployed elements of spatial ethnography (without necessarily identifying it as such) to study the urban. William H. Whyte, for example, in his pioneering study of small urban spaces enacted practices of spatial ethnography, from a keen spatial observation, to placing importance on the embodied and everyday activities of individuals passing under the gaze of his cameras.33 Yet Whyte did not push his spatial ethnography much beyond behavioral observation; without interviews the occupants of the plazas remained mute. What is the cultural context for the plaza users, and how does it relate to their use of space? What particular user narratives may enrich or even contest Whyte's reading and understanding of the plazas? What would it mean to focus on a few individuals rather than synthesizing their aggregate use of space? An urban humanities approach may have uncovered, beyond the formal and social patterns that can be directly observed, a “thick story” of the space.

What separates spatial ethnography from other forms of spatial analysis and GIS (geographic information system)-based social science is that spatial ethnography places the utmost importance on the embodied, everyday practices of people in their settings. Urban humanities aim to push this aspect further by making explicit the field's value claims, championing the importance of humanistic narratives and understandings of embodied spaces. One contemporary scholar who used spatial ethnography to analyze and document the vibrant streets of Ho Chi Minh City is Annette Kim, who merged macro-level socio-political analyses with direct observation of the micro-settings of everyday life (see figures 3.3 and 3.4). Her “critical cartography primer” is a collection of data about the activities taking place over the course of a full day on a single street in the city. She mapped down to the square foot observations of elderly residents playing games on the sidewalk with friends, shops with wares spilling out onto the street, or the rows of parked mopeds. Kim's practice emerges by taking a spatial ethnography sensibility and combining it with the recent, provocative literature on critical cartography.34 In her words, these elements provide “the best hope for throwing off conceptual blinders.” 35 Although Kim's methods can be used in a wide range of metropolitan settings, it is no coincidence that they have evolved outside Eurocentric urban conditions.

Filmic sensing is the third of our more developed practices of the urban humanities. Cinematographers, artists, and urbanists have long used the medium of film and video in order to represent cities, places, and spaces. In the process of developing and producing videos and films, the apparatuses used for capture (e.g., film cameras or cell phones) and editing (scissors or nonlinear editing software) become sensing devices through which our vision of the world around us can be transformed. Landscape architect Anne Spirn suggests that looking through the lens of a camera and capturing photographs not only senses the world but also allows us to make sense of it: “the practice of photography has long been a way of thinking and a method of discovery.” 36 And just as these instruments allow us to see the world anew, they also allow for communication across linguistic, disciplinary, and cultural boundaries. In the twenty-first century, cinematic vision has become so transnational and normalized across cultural boundaries that it constitutes a de facto Esperanto of visual language, a common language through which disparate groups can comfortably communicate with one another. While highly specialized languages such as regression models, digital platforms of architecture representation, and textual exegesis tend to obscure understanding by the layperson, film and video have the particular capacity of allowing participation for those blessed with the “symmetry of ignorance,” 37 that is, all of us.

Filmic sensing has its intellectual origins in two spheres. It stems from work pursued under the auspices of visual and sensory anthropology and ethnographic film, where it is used to provide embodied and sensory information in ethnographic contexts. It also stems from the artistic and creative work produced under the rubric of essay filmmaking. In this sense, it implicates its author in a self-reflexive fashion, combining fiction and nonfiction in pursuit of truths that would have remained otherwise undisclosed. And, importantly, it explicitly engages the aesthetic realm, considering the formal, visual, and artistic elements that contribute toward these truths, effectively represented and communicated to different audiences.

For example, artist Neil Goldberg approaches his video art in precisely this way. One of his projects, titled Surfacing (2011), shows dozens of clips of individuals emerging from a New York City subway stop, stepping up into the brightly lit, midday bustle of a street corner (see figure 3.15). The camera acts as an extension of the human eye, framing and focusing the gaze onto microscopic facial expressions that might otherwise go unnoticed: anticipation, anxiety, exhaustion, resignation. And its database-like organization provides a rigor to this study of human reaction: each clip is precisely edited to capture an identical moment of emergence, so that we can note differences from one commuter to the next. This way, a larger picture emerges that would have otherwise remained opaque, capturing a moment of human universality in the shared act of locating oneself in the world, a split second of vulnerability before the commuter orients herself in the city. More than just a representational medium, filmic sensing becomes an observational and analytical tool for engaging with, probing, and denaturalizing the everyday life of the urban.

Urban Humanities: An Emergent Field

Urban humanities employ the aforementioned three creative practices of scholarship—thick mapping, spatial ethnography, filmic sensing—to study, understand, and transform the urban. They do so with particular attention toward the future and spatial justice. We will discuss each in more detail later in the book and illustrate them through a series of case study projects that use these practices to explore, compare, contrast, and propose interventions for settings of everyday life in Los Angeles, Mexico City, Tokyo, Shanghai, and beyond. These case studies (Projects A–H) are called out in the colored sections between chapters, which provide some visual and textual representation of the larger project, and a handful have been explicated at more length by their respective creators and authors in a series of “interludes” also located in between the primary chapters of the book.

The three practices of scholarship of urban humanities come from a fusion of established disciplines that, in our view, points to an emergent hybrid field for the study of the urban. This field blends a humanist understanding of the spaces and cultures of everyday life, as depicted in text, film, art, or spatial ethnography, with the projective and transformative interventions of urban planning and design. Like any field, urban humanities have an intellectual lineage. In chapter 2, we explore this lineage and the various scholarly influences and precedents that gave rise to urban humanities. These are partially derived from critical transnational urban theorists, but are also indebted to other writers, scholars, and artists who work within an urban humanist frame. In chapter 3, we explore the three practices in depth and touch upon a handful of other practices, which remain in experimental “beta testing.” Chapter 4 brings the future to bear on all that we do, considering the implications of our reclaiming of the speculative, the projective, and the future within the context of academic and urban practice. Lastly, the penultimate chapter prior to the volume's conclusion dives deeper into the question of spatial justice, particularly as it informs our scholarly, pedagogical, and research practices within the contemporary university. In between chapters, we insert interludes—urban humanist projects undertaken by faculty, students and alumni of the program, or community-based collaborators at some cities of our intellectual investigations. These are paired with shorter descriptions of student projects, all indicated by the bright color assigned to each of the four cities (Mexico City: yellow; Tokyo and Fukushima: pink; Shanghai: red; and Los Angeles: blue). Both projects and interludes are included to help demonstrate or clarify our arguments.

Interlude 1:

Mexico City

Peatoniños: Liberating the Streets for Kids and for Play

Mexico City is home to more than two million children that represent 26.7 percent of its total population. But despite their numbers, children remain a political minority due to their perceived limited capacity to influence their environment. Urban policies have been unsuccessful in considering children's needs and perspectives and have not integrated them in the urban planning process. Children, then, must adapt to existing urban conditions, whether or not they are appropriate. Mexico City's highly car-oriented urban form is a major challenge for children, as it negatively impacts their mobility and physical safety and also contributes to their exclusion from open spaces and streets, ultimately isolating them indoors.

Access to high-quality public and play spaces is one of the greatest challenges faced by children in Mexico City. Children living in marginalized areas are the most affected by the lack of open and outdoor spaces where they can rest, walk, or play—activities that are fundamental for their physical, emotional, and cognitive development. Thus, (re)claiming and (re)creating urban environments, for and with children, has become a central issue in urban development. The city's recently enacted Constitution includes “the right to the city” as a main precept. This is the right of all Mexico City residents, including children, to change the city as they change themselves; it is the right to imagine and create the city they live in.

The Peatoniños project focuses on the children's right to their city. The project was created and is led by the Laboratorio para la Ciudad (Lab for the City), which is Mexico City's creative and experimental office directly reporting to the mayor. Peatoniños is a wordplay in Spanish that means “child pedestrians” or “children that walk.” The project is part of the Lab's Pedestrian and Playful city strategies initiative, whose objective is to understand how alternative, nonmotorized modes of travel and play can reconfigure urban imaginaries and encourage citizens to take an active role in the city-making process. Using “Liberating the streets for children and play” as its motto, the Peatoniños project consists of planning, designing, implementing, and evaluating streets that can accommodate play, in areas of the city with high levels of marginalization, large numbers of children, and few open play spaces (figure 1.3).

1.3 Street closed to traffic for Peatoniños event, Mexico City, 2016. Photo credit: Laboratorio para la Ciudad

Peatoniños is a response to the general lack and uneven distribution of playful spaces in Mexico City. It seeks to expand and make more accessible play and playful spaces in the city through the use of existing streets. Peatoniños aims to produce physical manifestations of alternative street use, demonstrating the city's social fabric and community interactions beyond the spatial paradigm of the car-oriented model. The three guiding principles of Peatoniños are: 1) a community-centered design approach, 2) a spatial and urban analysis of street spaces and their adjacent neighborhoods, and 3) a pedagogical approach that promotes a child's right to the city, right to play, and knowledge of issues regarding road safety. The aim is to liberate and reappropriate the city streets through play, especially in neighborhoods where public space is scarce.

Instead of focusing on developing over-planned interventions, detached from already existing local practices and resources available on the streets, Peatoniños follows a process in which every street for play—its tools, activities, and methodologies used before, during, and after the intervention—is understood as a design iteration. The entire process of this project from start to finish emphasizes the social capacity of design. The purpose is to create an index of institutional and local knowledge, resources, and relationships that, ultimately, would help develop networks to scale up and sustain the implementation of the project, but also criteria by which one can assess the quality of each playstreet design.

Eight streets for play have been implemented throughout the city so far, through a variety of collaborations. The first collaboration, in March 2016, was with urban humanities students from UCLA and involved closing down a street in Mexico City's Doctores neighborhood and temporarily converting it into playspace for children. From this small experiment, Peatoniños has evolved into a project that is becoming an ongoing public program. Together with the local government of the Iztapalapa borough—where more than five hundred thousand children live—the merging of top-down and bottom-up approaches addressing the lack and uneven distribution of open play spaces for children is starting to happen. Collaboration with the local government in this area is helping to create a tool to measure the impact of Peatoniños playstreets and identify how play and playfulness influence public narratives and public policy. Furthermore, Peatoniños seeks to cooperate with civic programs that promote community participation in public decision-making (figure 1.4). Peatoniños is now focusing its efforts not only on closing streets and converting them into temporary playspaces, but also on forming a collective vision of how adults and children can shape the city in tangible ways. In its next stage, it also plans to create a new typology of permanent streets designed by and for the children.

1.4 Painting a zebra crossing and leaving a mark in the Obrera neighborhood of Mexico City. Photo credit: Laboratorio para la Ciudad

Figure 1.5 helps to visualize and communicate the overall spirit of the project, which is about considering children (Peatoniños) as active agents and city heroes with the capacity to join forces with “Peatonito”—a luchador (fighter) who defends the rights of pedestrians in Mexico City and changes the communities they live in (figure 1.6).

1.5 Luchador with children wearing masks and acting as city heroes in the Doctores neighborhood. Photo credit: Laboratorio para la Ciudad

1.6 Children wearing a luchador mask, in the Buenos Aires neighborhood of Mexico City. Photo credit: Laboratorio para la Ciudad