6

TWO CASE STUDIES: AN INTIMATE VISIT

Baby Jack

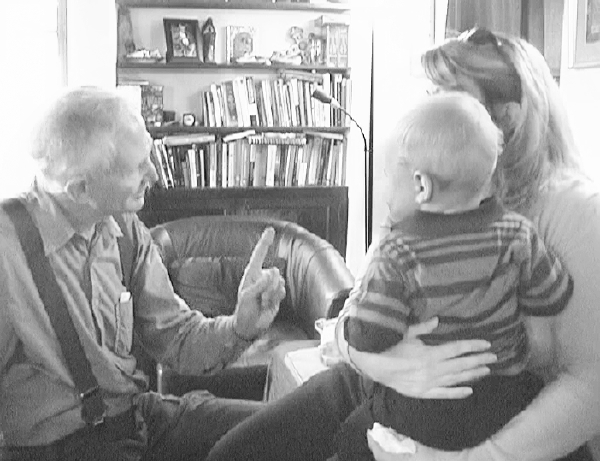

A mother and child reunion.

Jack is a bright and energetic toddler, yet at the same time painfully shy and reserved. He had been referred to me by a colleague because he had struggled through a very difficult birth and was now contending with the sequelae to that ordeal. Jack had been in a breach position with the umbilical cord wrapped three times around his neck and his head caught high in the apex of the uterus. Each push he directed with his tiny feet and legs drove his head into a tighter wedge, while further constricting the cinch around his throat; this was a “no exit” ordeal evoking a primal suffocation terror, something difficult for most adults to comprehend.27 During the emergency C-section, doctors noted Jack’s serious distress; his heart rate had dropped precipitously, indicating a life-threatening situation. In addition to the C-section, it required forceful suctioning to dislodge Jack’s head from the uterine apex. His arrival into this world was accompanied by multiple clinicians poking and prodding at him, plying their trade with the necessary needle sticks, IV insertions, aggressive examinations, and rushed interventions.

Now fourteen months old, Jack was being worked up for yet another invasive procedure to investigate a condition of intermittent gastric reflux. His mother, Susan, was dutifully following through with the pediatrician’s recommendations and had scheduled an endoscopy for two weeks from the day of our first session. While she appreciated the pediatrician’s thoroughness, Susan was hoping that there might be another solution, one that was not invasive and potentially traumatizing. With this hope in tow, she and her young son arrived on my doorstep late in the fall of 2009.

Jack sat astride his mother’s hip as I opened the door and interrupted her second knock. She looked somewhat abashed as the follow-through on her rapping propelled her across the threshold and into my office. Regaining her composure and adjusting her son’s position, she introduced herself and Jack. As they came through the entryway, I noticed an awkwardness in the shared balance of mother and son. I could have dismissed this as a general unease with a new environment, an unfamiliar stranger, and an unknown form of therapy. However, it seemed to be more fundamental than that; there was a basic discordance in their dyadic rhythm.

It is often assumed that when there is a disconnection between baby and mother, there was a failure on the part of the caregiver to provide the “good enough” environment required for bonding. This is not always true, as, clearly, was the case with Susan. She earnestly and lovingly provided comfort, support, and attention. It was, rather, the traumatic birth that caused a jolt, splitting them apart at birth. The subsequent “shock wave” disturbed their mutual capacity to participate in each other’s most intimate moments, to fully bond and attach.

In my office, Jack scanned his new surroundings as his mother summarized his symptoms and the upcoming procedure. While concurring with her concern and offering information about how I work, I was also tuning into her son’s here-and-now process. Following his gaze, I could see that he was intrigued with the colorful array of toys, musical instruments, dolls, and sculptures that were crowded onto the shelves above my table.

I picked out a turquoise Hopi gourd rattle and began slowly shaking its seeds. Using the rhythm to engage baby and mom, I made eye contact with Jack and called out his name. “Hi, Jack,” I intoned in rhythm with the rattle.

Jack tentatively reached out for it, and I slowly extended my arm to offer the handle to him. He then pulled back in response to my overture.

He then reached for it again with an open palm, but on contact, he pushed it away and turned toward his mother with a faint cry of distress.

She responded by securing her hold on him and rotating away from the interaction with a quick spin. He was distracted, looked away, and became quiet. I began talking to Jack about his difficult birth, speaking as if he could understand my words. My prosody and tone modulations seemed to give him some comfort and reassurance, conveying that I was an ally and somehow understood his plight.

Recovering, he reached out again with curiosity and then pointed toward the table. “Apple, apple,” he said, extending his left arm toward a plate holding three pomegranates.

I lifted the plate and offered them to him. Jack reached for them, touched one, and then pushed it away. This time his push was more assertive. “You’re into pushing, aren’t you?” I asked, again communicating not only with words but with rhythm and tone. “I sure can understand how you might want to push, after all those strange people were poking and hurting you.” Wanting to reinforce his pushing impulse and his power, I offered my finger to him; he reached out to push it away. “Yeah, that’s great,” I responded, conveying my feelings of encouragement, warmth, and support. “You sure want to get that away from you, don’t you?” Jack let go another whimper, as if he agreed.

Susan sat down on the couch and began removing Jack’s shoes. He seemed fearful and turned away from the two of us as we talked about his gastric reflux and its possible penetration into his lungs. When Susan mentioned that the pediatric surgeon was proposing an endoscopy, Jack seemed to show a flash of distress: His face scrunched downward in a frown of worry and anxiety as he called out, “Mama.” Jack seemed to have recognized the meaning of our words (or was perhaps picking up on his mother’s unease), and in a millisecond, his mid-back stiffened.

He turned toward his mother and I gently placed my hand on his mid-back, resting my palm over his stiffened and contracted muscles while extending my fingers upward between his shoulder blades.

Jack whimpered again and then turned to look directly at me. Given that he maintained our eye contact, I assessed that it was safe to proceed with the physical touch. Jack continued to connect with me visually as his mother recounted the history of his symptoms, treatment, and medical assessment.

Suddenly, Jack pushed mightily against his mother’s thighs with his feet and legs, propelling him upward toward her left shoulder. This movement gave me a quick snapshot of his incomplete propulsive birth movements. These were the instinctual movements (the procedural memories) that had driven him into the apex of her uterus and strangled his throat with the cord—exacerbating his distress while further activating his drive to push, creating, in turn, even more distress. As if following a dramatic, choreographed script, Jack pushed hard against his mother’s legs twice more, propelling him, again, up to her shoulders.

This completion of his birth push, without the resulting strangulation, intense cranial pressure, and “futility” brought on by his head wedging into the uterine apex, was an important sequence of movements for Jack to experience. It allowed him a successful “renegotiation”—in the here and now—of his birth process. His procedural memories shifted from maladaptive and traumatic to ones that were empowering and successful. Maintaining a low to moderate level of activation in this “renegotiation” was essential. I quietly removed my hand from his back and allowed him to settle.

His mother responded to his thrusts by standing him up in her lap. While I maintained a soft presence with an attentive, engaged gaze, Jack looked directly at me with a fierce intensity that seemed to express his furious determination. His spine elongated and he seemed both more erect and alert.a

I again reached for Jack’s mid-back and spoke soothingly: “I wish we had more time to play, but since they are planning this procedure in a few weeks, I want to see if we can do something to help you.” Jack stiffened again and strongly pushed my hand away with his. He grimaced and flashed me a look of snarling anger while simultaneously retracting his hand and priming for another major defensive push away.

I offered Jack some resistance by bringing my thumb into the center of his small palm. By matching his force and allowing him to push me away with his strength, I observed that, as his arm extended, he was able to harness the full-throttle power of his mid-back and then follow through with a robust thrust. We maintained eye contact and I responded to his expression of concerted aggression by opening my eyes wider in surprise, encouragement, excitement, and invitation.

As he pushed my hand away, his response transformed into one of seeming celebration. I reflected back to him his great triumph over an unwelcomed intruder, an intruder who characterized his earliest experience of a threatening and hostile world.

Jack pulled his hand back and let go with a small whimper, but he maintained eye contact, giving me an indication that he wanted to go on.

His cry strengthened as he gave one more strong push to my thumb. He howled with apparent anguish, confusion, and rage.

His cry deepened, becoming more spontaneous after I placed my hand on his back. This invited the sound to come through his diaphragm in deep sobs. As he pushed my hand away, once more I spoke to him about all those people touching and poking him and how much he must have wanted to push them away too.b

Jack broke our eye contact for the first time in this series of pushes and turned toward his mom.

Within seconds he turned back to reengage our eye contact, even as his cry deepened. I responded to his cry with a supportive “Yeah … yeah,” matching his anguish with a soothing, rhythmic prosody.

Jack took a deep and spontaneous breath for the first time, turning his chest toward his mom, then looking over his shoulder to once again return my eye contact.

I explained to Susan about the importance of encouraging Jack’s breath into the thoracic area of his back. I did this by placing my hand on hers and guiding it to his back, showing her how to support him in that area while also directing and focusing his awareness there. I explained that his pattern of tightening and constricting in this area might be in large part responsible for his reflux issues—and indeed it was! Jack continued to cry, but remained relatively relaxed. We paused for a moment, since I could see that Susan was consumed by many thoughts and feelings of her own.

Susan took a deep breath and then looked down in amazement at her son. “He never cries,” she said. “Or rather, he cries with a little whimper, but never fully like this!” I reassured her that it seemed to be a cry of deep, emotional release.

“I mean, I can’t remember the last time I actually saw tears running down his face,” she added in grateful astonishment.

Jack reached out from his nested position and assertively pushed my finger out of the vicinity of his territory. I reinforced to Susan how profoundly disturbing it must have been for him to have strangers probing him with all those tubes and needles, how very small and helpless he must have felt. Susan repositioned herself as he burrowed deeper into her lap and chest.

Jack nestled into his mother’s lap with a new molding impulse, hitherto unseen by her. Molding is the close physical nestling of the infants’ body into the shoulder, chest, and face of the mother. It is a basic component of bonding—the intimate dance that lets the infant know that he is safe, loved, and protected. I believe that it also replicates the close, contained, physical positioning of the fetus in the womb and conveys similar primal physical sensations of security and goodness.

“I’m not sure what to do with this,” she commented, pointing with her chin to his nuzzling and snuggling shape. We paused together for a moment to appreciate this delicate contact between the two of them.

“Whoa!” she said, breaking the silence. “He is really hot.” I commented that heat was part of an autonomic discharge that accompanied his crying and emotional release.

Jack settled down as she rocked him gently, maintaining full, yielding, chest-to-chest contact. He took in an easy, full inhalation and released it with a deep, spontaneous exhale that sounded both ecstatic and profoundly stress relieving. Indeed, Susan also let down her guard, shedding her doubt and beginning to trust that this new connection was “for real.”

Susan looked down at her son as he continued to mold, deeply, into her chest and shoulder. She bent forward to meet his molding with her head and face. The two could be said to be “renegotiating their bonding.” Susan continued to gently rock her son while maintaining their connection. He continued to regulate himself with a gentle trembling and then took several deep, spontaneous breaths with full and audible exhalations. Susan threw her head back in an ecstasy of contact and connection.

Jack peered out from his burrow and made eye contact with me. I recognized that he had had enough for one day, so I began to wind down the session. Susan acknowledged the closing, but needed to again share her own process of astonishment and hope.

With a perplexed and startled expression she noted, “I’ve just never seen him be this still.” Then she asked Jack, “Are you asleep? So sweet, oh so sweet,” as if getting to know her baby for the first time.

I asked Susan to take notes during the next week of anything new in Jack’s behaviors, energy level, sleep patterns, reflux symptoms, and so on. Jack peeked out from his secure nesting and gave me one brief, broad smile. I responded with a return smile and a few inviting words. A couple of seconds later, another slight smile slipped across his relaxed face.

Before the end of the session, Jack and I played hide-and-seek with this warm and playful engagement for a few moments; however, at no time did he leave the cradle of his mother’s lap. She nuzzled his head and mused, “This really seems different. Usually he gives a quick hug and then is off on his way.” Almost as if smelling her newborn and drawing him in to her chest, she too let out an audible exhale and broke into a broad smile. “This is so very strange,” she murmured quietly. “He is affectionate, but never still … he never stays with me … he’s always off to something new.”

As they continued to snuggle, they smiled in tandem. Their absolute delight was visible and palpable. Her baby had come home and they celebrated, together, that reunion.

At our next session, one week later, Susan had a number of anecdotes she wanted to share. Her upbeat excitement and Jack’s comfortable curiosity were contagious. They sat down together on the couch, Jack resting his head against his mother’s chest. I leaned forward in my chair, eager to hear her report. She began by recounting an episode that had occurred the night after our first session.

“He woke up in the middle of the night and called out, ‘Mama,’” she reported, adding that she went to pick him up as usual. Jack sat quietly on her lap and pulled his head down deeper into her chest. “When I picked him up, he was doing this,” she added, pointing with her chin to his comfortable snuggling.

I watched with an appreciative smile. “Looks to me like he’s making up for lost time,” I suggested.

She resumed her story: “Well … and then he said, ‘Apple, apple.’ I thought he wanted something to eat, but normally this would include him wiggling out of my arms and running to the kitchen. So I realized he must have been talking about the ‘apples,’ the pomegranates, on your table.” She explained that after their last session with me, later in the week, they had an appointment with the pediatrician, which upset Jack. While they drove home in the car he kept calling out to Susan from his car seat, “Pita, pita, apple, pita.”

“Again I thought he was hungry,” Susan continued, “and responded by asking him if he wanted pizza. ‘No,’ [he answered]. ‘pita, pita, apple!’ I realized he was talking about you, trying to say ‘Peter.’ Pretty amazing, isn’t it, how much he recognized and wanted to talk about the change he felt?” she queried, looking up at me for validation.c

I smiled with shared enjoyment and appreciation, and then asked about his energy. “He has been so much more talkative, much more interactive. He wants to show us lots of things and then wants our feedback. He seems much more engaged and interested in having us play with him.” She bent down and kissed his head as he curled up in her lap.

“But really, this is the biggest change,” she said. “I can’t tell you—for him to sit and just be cuddled, it’s a complete change, completely different. It’s not him … it’s … it’s the new him.”

“Or maybe it’s the new us,” I responded.

Susan tipped her head shyly and spoke, ever so softly. “It’s wonderful for me.”

Jack and I played for much of the rest of this session. I recognized that much of the birth trauma and interrupted bonding was resolved and that his social engagement systems were awakening and coming online with gusto. As previously noted, the lack of attachment is far too often attributed to the mother’s lack of availability and attunement. But as you can see here, it was their shared trauma that disrupted their natural rhythm and mutual drive to bond.

The molding that occurred in the first session is an essential component of bonding, a physiological “call and response” between mother and child. The renegotiation of Jack and Susan’s bonding, which had been so severely interrupted by his birth crisis and neonatal care, was revisited after he discovered his capability for self-defense and the establishment of boundaries. Along with this, he had then completed the critical propulsive movements that had been overwhelmed at the time of birth and were left unresolved.

It is assumed that we have extremely limited memory of early preverbal events. However, “hidden” memory traces do exist (in the form of procedural memories) as early as the second trimester in utero and clearly around the period of birth.28 These imprints can have a potent effect on our later reactions, behaviors, and emotional, feeling states. However, these perinatal engrams become visible only if we know where and how to look for them. A useful analogy for how to look for these deep perinatal and birth imprints, which may be obscured by later engrams, is as follows: Consider yourself sitting on the beach, observing the ocean. One becomes aware, first, of the waves and whitecaps. But then, if you were to dive in for a swim, you would be deeply affected by the currents or riptides. Indeed, they would likely have much greater impact than the waves. Further, many orders of magnitude more powerful than either of these forces are the barely visible actions of the tides. Just to recognize that they exist, we would have to sit and observe the water levels for many hours, yet the power we might capture from their force could light up an entire city.

Looking for the powerful perinatal and birth engrams beneath the more recent memory imprints requires that we clinicians use the same patient, relaxed alertness as one observing the waves, currents, and tides. As Yogi Berra said, “You can observe a lot by just watching.” With Jack, these early, primal, tidal forces were noted, for example, when he propelled his whole body upward against his mother’s legs as his back was supported by my hand. This action was evidence of Jack’s inner drive to complete the birth movements that were thwarted when he was trapped in the apex of his mother’s uterus; the more he pushed, the more trapped he became. It was the long-term outcome of his successful renegotiation of the birth traumas that we observed and consolidated at his follow-up visit a couple of years later.

Jack’s Follow-Up Visit

To belatedly celebrate Jack’s fourth birthday, I invited Susan to bring him in for a short visit. I was excited to see the two of them, both because of the delicate moments we had shared together and, quite frankly, from my curiosity about just how his procedural memories would express themselves.

Conventional understanding of neurological development posits that when I first saw Jack at the age of fourteen months, he was far too young to form any episodic or conscious memories. Furthermore, the existence of anything resembling an autobiographical and narrative memory would be impossible at this age. As they entered through my door, I reintroduced myself to Jack and Susan. She asked him if he remembered me. He definitively declined with an emphatic “No!” However, Susan chuckled and said, “As we approached the door he asked me, ‘Mama, is he going to put his hand on my back?’” Clearly, Jack had episodic access to the procedural (body-based) memory from our encounter when he was fourteen months old.

Recall that in his first session Jack was able to engage and develop the impulse to set boundaries and to no longer feel helpless. By then discovering that he could push and successfully propel himself through the birth canal, this time without getting stuck, he achieved a new mastery of the birth process. Along with the crying and autonomic discharge (waves of heat and spontaneous breaths), his and his mother’s innate biological drives were prompted and united, leading to his deep molding and their bonding connection. In this sequence he was able to embody the totality of this experience that was encapsulated in the image of the pomegranate (“apple”). This seemed to reinforce his connection to the three of us. Later, he was able to call on this image and my name (“pita”) to help regulate himself after being frightened by the doctor.

Now at my door, four-and-a-half-year-old Jack’s procedural memory had morphed into an emotional one—the feeling of what had happened—and a desire for more of these feelings. The transformation of his memory engrams, from procedural to emotional to episodic, can be recognized in his expectant question, “Is he going to put his hand on my back?”

Susan went on to say that Jack had turned out to be a stellar athlete, as well as being one of the brightest children in his pre-kindergarten class. No surprise, as his interest in many of the objects in my room was enduring. She also noted that he rarely would curl up in her lap unless he was sad, tired, or scared—perfectly normal for a child his age.

“So Jack,” I asked, “what is your favorite sport?”

“Baseball,” he answered with a grin.

“And what position do you play?” I asked.

“Oh, I like to play pitcher and second base and also catcher,” he replied, smiling with an evident pride in his ability to remember all these positions.

Susan said that he was always playing with his peers and had become quite autonomous, although she added, “He still likes to be hugged and nestled from time to time.” As though on cue, Jack climbed up into his mother’s lap and nuzzled his head and shoulders into her chest, just as he had done three years earlier. And just as she had done at that time, a broad smile appeared on his mother’s lips and eyes. It was as though they had time traveled together in the shared celebration of our reunion. Susan then puzzled out loud, “This is very unusual—Jack is so social and always prefers to be active or with his friends.”

So what can we make of all of this? I am quite sure that Jack did not “consciously” remember me (i.e., as a declarative memory), but then where did the question come from? What part of his memory had prompted him to ask her, “Is he going to put his hand on my back”? Indeed, was Jack using the more conscious part of his brain/mind to access the primal sensations (the procedural memories) that had remained latent until they were triggered at the threshold of my house?

Jack’s four-and-a-half-year-old body began to replay his implicit experience from three years earlier, but this time he was able to put words to his bodily experience, to pose the question of whether I would put my hand on his back. And then, cued and primed, he replayed the procedural memory of securely resting in his mother’s arms. Curling up on her lap with his back facing me, he invited me to put my hand on his spine and, once again, gently massage his now strong, athletic back as he melted into his mother’s embracing arms.

And to top things off, he nestled in for a grand hug.

Jack continues to thrive, and I thank both him and his mother for letting me share their journey.

Ray—Healing the War Within

He who did well at war just earns the right

To begin doing well in peace.

—ROBERT BROWNING

Prologue

The cold facts: Over twenty-two suicides of military personnel occur every day. This totals more than have been killed in the entire wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and more than twice the incidence in the general population. Ray, whose experience we shall visit, was in a platoon that had one of the highest rates of suicide in the Marine Corps.

Two to three million military personnel are returning from warfronts, bringing with them the hidden costs of war. They carry home an invisible affliction, their trauma wounds “infecting” their families and eventually their communities. Certainly if a million people returned from a warfront with an extremely virulent form of tuberculosis, it would be considered a national emergency. We would immediately summon forth the expertise and attention of scientists and clinicians throughout the country. Instead, we turn a blind eye and helplessly brace for an incoming tsunami of trauma, depression, suicide, violence, rape, divorce, addiction, and homelessness to hit our shores. The lack of effective mental health treatment for our soldiers is a broad-scale abandonment of our collective responsibilities as a nation, and particularly as therapists and healers. Neglect of these obligations almost ensures a contagious epidemic of suffering that, ultimately, affects us all.

Whatever our personal beliefs about a particular war, as a society we owe these returning warriors, who have put themselves in harm’s way in our name, the healing and restoration to civilian life that they so deeply deserve. Ray is one of these very exceptional young veterans, and this is his story.

Ray and his platoon were stationed in Afghanistan, in the Helmand province. On June 18, 2008, they encountered a violent ambush, several of the platoon members were killed, and his best friend died in his arms. Later that day, while on patrol, two IEDs (improvised explosive devices) exploded in rapid succession. These blasts, in close proximity to Ray, literally propelled him into the air. He awoke two weeks later in the military hospital in Landstuhl, Germany, unable to walk or talk. Only gradually, and with sheer willpower, was he able to relearn those basic skills. When I first saw Ray about six months later, he was suffering greatly from symptoms of PTSD, TBI (traumatic brain injury), chronic pain, severe insomnia, depression, and what was diagnosed as Tourette’s syndrome. He was on a cocktail of powerful psychiatric medications including benzodiazepines, Seroquel (an “antipsychotic”), multiple SSRIs, and opioid pain meds.

In December 2008, Ray was brought to a consultation group I was holding in Los Angeles (Session 1). After this initial session, we did three more pro-bono sessions at my home (Sessions 2, 3, and 4). And then, in 2009, I invited him to participate in a five-day workshop I was offering at the Esalen Institute in the majestic setting of the rugged Big Sur California coastline (Sessions 5 through 10). This provided an opportunity to continue our work together and gave Ray the possibility of interacting with others in a safe and supportive social environment.

Session 1

Ray began by talking about the dozen or so powerful and numbing psychiatric and narcotic medications he was taking to treat a multiplicity of diagnoses. Functionally, his impairment consisted of convulsive contractions of the head and neck, beginning first in the eyes and jaw and then spreading downward into the neck and shoulders. In this initial interview, he looked away and down at the floor, unable to make eye contact and conveying a pervasive sense of shame and defeat.

As Ray attempted to make eye contact, I noticed one of these convulsive contractions. This sequence took place in an interval of approximately one-half second and is probably the reason he was diagnosed with Tourette’s. From the point of view of Somatic Experiencing, however, these rapid sequences are viewed as incomplete orienting and defensive responses. At the moment of the first explosion, Ray’s ears, eyes, and neck would have (just barely) initiated a turn toward the source of the event. These premotor preparatory responses are triggered in primitive brain stem core response networks (CRNs).29 However, well before this action was even executed, the second blast occurred almost simultaneously, and the two explosions hurled him violently into the air. At this point, his head and neck would have been pulled abruptly into his torso (the so-called turtle reflex), while the rest of his body initiated a curling up into a ball (or, to phrase it technically, he contracted in a global flexion reflex). Together, they form a snapshot of the incomplete orienting and protective defensive sequence that had become “stuck” and overwhelmed. This incomplete procedural memory (fixed action pattern) gives rise to perseveration and the so-called Tourette’s-like tic spasms.

(a)

(b)

(c)

(d)

I noticed that Ray’s jaw contracted first, a fraction of a second prior to the full convulsion, which involved the neck and shoulders. To interrupt this sequence, I had him very, very slowly open and close his jaw: opening to the point where he began to feel resistance or fear and then letting his mouth close, ever so slightly. We did this again, opening to the point where he felt the resistance, and each time gradually expanding the opening. I had him repeat this awareness exercise a few times. Each time, we saw that his mouth was able to open a small amount more. This exercise allowed the convulsive sequence to play out, at a much attenuated level by reducing this “over-coupling”. Ray suddenly opened his eyes, looked around in curiosity, and described a pleasant tingling sensation spreading from his jaws into his arms.

Next, I had Ray follow my finger with his eyes. (The elapsed time for following my finger was about 5 to 6 seconds).

(a)

(b)

(c)

(d)

Eye movements are a vital part of the orienting response. If there is a loud sound (or even the faint sound of footsteps or the cracking of a branch in the forest), our eyes try to localize the source of the disturbance. What I was looking for in this exercise was just where his eyes, along the horizontal, vertical, or circular axes, froze, jumped, or “spaced out.” Ray’s eyes would have been initiating an orienting response toward the source of the first explosion, but then would have been overwhelmed, unable to lock onto and identify the source of the threat as he was blown into the air. Clearly his nervous system was unable to process this utterly overwhelming series of events which followed the fire-fight and the death of his dear friend. Uncoupling the eye movements allowed the clamping-down of his jaw muscles, which I had already identified as the initiator of his convulsive neuromuscular sequence (procedural memory) to further resolve.

In examining his visual response, I saw his eyes lock across 5 to 10 degrees in the left quadrant, reinforcing my suspicion that the blast came from his left side. I stopped my finger movement at the point where Ray’s eyes froze or “spaced out.” These reactions represented episodes of constriction and dissociation, respectively. When either of these outcomes occurred, I paused and allowed the activation to settle. This combination of exertion, triggered response, settling, and stabilization promotes the forward movement of the procedural memory in the direction of an eventual completion.d As I carried out this process in intervals, moving gently through activation/deactivation cycles, Ray’s eye tracking began to gradually “smooth out,” and the convulsive sequence softened and began to become more organized. Ray reported feeling more peaceful.

After resting for a couple of minutes, allowing his activation to settle, I continued the eye tracking. This time there was only a minute activation of the convulsive sequence. Ray then took his first easy (spontaneous) breath and his heart rate slowed from about 100 to 75. I observed this by watching the carotid artery in his neck. He described a deep relaxation in his hands and a “tingling and warmth spreading all over [his] body.” The contented expression on my face reflects our shared experience of his settling as he moved toward an enjoyable tranquility.

(a)

(b)

Elapsed Time ~ 10 seconds

Next, Ray spontaneously stretched out his hands. I had him place his mind in his hands and to really sense what that feels like (interoceptively) from the inside. As Ray did this, each time, he gradually opened his hands wider and wider. This helped him to make greater contact with the dynamic healing rhythms of “pendulation,” pulsation, and flow.

(a)

(b)

(c)

(d)

(e)

Elapsed Time ~ 5 seconds

Session 3

In the third session, at my home, I asked Ray to evaluate his progress by noting where he was at this point in time on a scale of one to ten—one being where he started out before our first session in Los Angeles and ten being where he is fully competent, confident, and has the life that he wants. He reported that he was a four. I then asked if he could look ahead into the future and see where he thought that he would be in the next weeks and months. He opened his arms in an expansive gesture and then said he could see himself as a six … and then as an eight. As his “coach/guide” I didn’t hide my enthusiasm at his belief in his own healing momentum. This “quantitative” assessment that Ray had so energetically participated in is a useful exercise, in that it helps to demonstrate to the client that they are clearly moving out of the traumatic shock/shutdown where they could not imagine having a future different from their (traumatic) past. As Ray so aptly put it, “Now I can see myself having a bright future.”

(a)

(b)

(c)

(d)

(e)

Session 5

The next sessions with Ray took place during a one-week workshop at the Esalen Institute in Big Sur California.

During this session I had Ray make a particular sustained “voo” sound, along with opening and closing jaw movements.e This was to help connect his vital energy center in his abdomen with the sense of determined aggression in his jaw. Ray initially reported experiencing tingling throughout his body that made him feel more alive. However, he was not able to sustain this enlivening feeling and began to close in on himself with a collapsing posture and constricted breathing. I suspect that this shutdown was due to his pervasive survivor’s guilt, which was immediately triggered by the experience of feeling alive. We can clearly observe how his head looks downward. To explore this guilt, I had him say the following words and notice what was happening in his body as he said them: “I am alive … I am here … I survived … not everyone did.” This scripted probing allowed him to both acknowledge the guilt and begin to confront his rage. Eventually, this rage led to uncovering his profound sorrow at losing close comrades from his band of brothers.f

In order to help Ray process his rage and access his underlying feelings of loss, vulnerability, and helplessness, I enlisted two members of the group to help him both contain and direct his rage. I wanted him to be able to sustain this movement and direct it into a large pillow—rather than cathartically exploding with it. Due to his deep fear that his anger and rage could potentially cause him to hurt others, he habitually restrained the impulse to strike out. This impulse to punch and destroy engaged his anterior muscles. In sensing this compelling (but unacceptable) urge, he simultaneously contracted the muscles on the back of his of his arms and his shoulders to prevent this forbidden impulse to annihilate other people. However, this neuromuscular inhibition locked up his body and buried his softer feelings in a kind of muscular “armoring.”

The two group members now “took over” the restraining function (of holding back) and then helped him to contain and channel the action of striking out so that he could feel and move forward with the uninhibited impulse in a safe and titrated way. This allowed him to experience his full “healthy aggression” and contact his “life force,” his elan vital. He repeated this directed action three times, letting the sensations and activation settle after each prolonged and sustained forward thrust.

(b)

(c)

(d)

(e)

Elapsed Time ~ 30 seconds

After the third time, I asked him what he noticed in his hands and arms. He responded, “They feel really strong … in a good way … like I can move forward in my life. I feel the strength to get what I want from my life now while still honoring my buddies who fell.” This forward movement in life is the essence of “healthy aggression.”

At this point we sat down together, side by side. Ray described how it was for him when he saw his best friend die in his arms, the utter helplessness and loss. With my support, and that of the group, he did this, quietly, with grace, calm, and—most importantly—dignity. Tears welled up in his eyes as he calmly acknowledged and shared his pain and grief with the group.

This “soft feeling” component is the culmination of an organic, six-phase, sequential process involving (1) resolving the shock reaction from the blasts; (2) imaging a future different from his past; (3) dealing with his guilt and rage with group support and containment; and (4) contacting his healthy aggression and inner strength, which (5) allowed him to, finally, quietly come to terms with his deeper feelings of grief, helplessness, and loss, and (6) orient in the here and now. Ray, who was shy within groups, began to look at me and around the room as though he was seeing the other group members for the first time. He was able to be with his deep feelings of loss yet be with other human beings. This was, perhaps, a “transitional family” for him, a link to civilian life and the world of feelings.

Some months after the session at Esalen, Ray married Melissa and they had a son, Nathaniel.

In 2012 they arranged to come visit me where I was staying in Encinitas, California, for a check in.

Ray described how “keyed up” he was the night before this session, due to his excitement. By using some of the exercises that I taught him, he was able to bring about states of rapid relaxation. We then did the “voo” sound and jaw movements together. He described relaxing and feeling “waves of warmth” that were also accompanied by “waves of joy.”

I asked Ray how things had been going in his life. He described some of his encounters with equine therapy and how he experienced these animals as nonjudgmental and willing to trust.

Used with permission of The Meadows Addiction Treatment Center © 2012.

I ask Ray to go inside himself and notice if he could feel the same nonjudgmental quality he did with the horses and then to notice where, in his body, he experienced this inner sense. As he began to connect with these feelings of self-compassion, I asked if he could then look at Melissa and notice what he felt for, and from, her. They quietly gazed at each other and smiled softly.

Melissa described how she had learned to give her husband his space and not take it personally when he needed to withdraw.

Melissa started to tear up as she described how relieved she was that they had been able to get to the place where they can stay in contact even when he needs to withdraw. This is an important skill for veterans and their families (and all of us, for that matter!) to develop—the ability to not interfere with a vet’s need for “space” (and to help keep them safe), and for the vet to still maintain a connection by communicating their needs and feelings, including their need to withdraw.

(a)

(b)

(c)

Nathaniel, their son, burst into the room, and Melissa looked at him with joy as Ray took pleasure in Melissa’s loving appreciation of their child.

Melissa told Ray how touched she was as he opened up more and more to her. She added that even though things can be tough, it is these moments that help keep the bond between them growing.

The session ended in the sweet social engagement of mirroring and playful interactions.

A video showing much of what is presented here can be viewed online: www.youtube.com/watch?v=bjeJC86RBgE

Epilogue and Discussion

In January 2015, former Marine David J. Morris published an article in the New York Times titled “After PTSD, More Trauma.”30 In this piece, he describes being discharged in 1998 from the Marine Corps and then working as a reporter in Iraq from 2004 until he was nearly killed in 2007 by an IED. After this harrowing ordeal, he sought therapy at the San Diego Veteran’s Affairs clinic, where he was treated with prolonged exposure (PE), one of “the treatments of choice” for PTSD. In this form of therapy, patients are made to relive, over and over, the worst horrors and terrors of their war experiences; by retelling the story of their trauma to their therapists, patients will theoretically “unlearn” the traumatic reaction they have to those particular memories.

The event Morris chose to focus on in therapy was the IED ambush he had survived in 2007 while reporting in southern Baghdad. “Over the course of our sessions, my therapist had me retell the story of the ambush dozens of times,” Morris writes. “I would close my eyes and put myself back inside the Humvee with the patrol from the Army’s First Infantry Division, back inside my body armor, back inside the sound of the IEDs going off, back inside the cave of smoke that threatened to envelop us all forever. It was a difficult, emotionally draining scene to revisit.” He hoped that over time, with enough repetitions of the story, he would rid himself of his terror. Instead, after a month of therapy, he began to have more acute problems: “I felt sick inside, the blood hot in my veins. Never a good sleeper, I became an insomniac of the highest order. I couldn’t read, let alone write. … It was like my body was at war with itself.” When Morris’s therapist dismissed his increased anxiety and concern about the efficacy of PE, Morris left, calling the treatment “insane and dangerous.”

Morris also critiques PE for its focus on a single event—the equivalent, he presciently noted, “of fast-forwarding to a single scene in an action film and judging the entire movie based on that.” This brief, cursory observation makes a very important point about PE and other cathartic therapies: These dramatic therapies operate with the implied belief that each traumatic memory is an isolated island, a very specific “tumor” that needs to be cut out, excised. This reified, illusory view of traumatic memory, as a thing to be repetitively relived and thus resected, dismisses the organic gestalt of body, mind, and brain in integrating the entirety of an individual’s encounters with stress and trauma, as well as of triumph, happiness, and goodness—that is, within the full developmental arc of one’s entire life. It is here that I feel prolonged exposure types of therapies miss the mark. And though they undoubtedly do help some, they harm others. It is revealing that there is an extremely large dropout rate of those who, like Morris, elect not to continue because of mounting distress. But let us look at a brief history of abreaction and trauma.

Abreaction—derived from the German Abreagieren—refers to the reliving of an experience in order to purge it of its emotional excesses.31 The therapeutic efficacy of this has been likened to “lancing a boil.” Piercing the wound releases the “poison” and allows the wound to heal. In the same way the lancing process is painful, reliving the trauma can be highly distressing for the patient. Hopefully, the freshly opened wound, according to this kind of analogy, will be able to heal. However, this may not avoid renewed infection, and unfortunately, this can happen, as Morris so aptly chronicled. And while Somatic Experiencing, the approach I used with Jack and Ray, works much more gently with procedural memories, no therapy is foolproof. Although, I would offer, its slower and titrated process has a wider margin of safety, which decreases the likelihood of retraumatization when compared with PE and other cathartic therapies. I sincerely hope that therapists using exposure methods will use some of the tools outlined here to inform and evolve their therapeutic work.

Eventually, Freud seemed to construe that the repressed emotions connected to a trauma could be released by merely talking about them; this “discharge” of traumatic affect could be produced by bringing “a particular moment or problem into focus.”32 This method would become the foundation of Freud’s approach to treating (so-called) hysterical conversion symptoms.33 By the time of World War II, hypnosis and phenobarbital (narco-abreactions) were utilized to elicit intense emotional catharsis. However, these methods were eventually abandoned because the results were often deleterious or, at the least, only short-lived. Interestingly, one of the patients at San Diego’s Balboa Naval Hospital in 1943 was the science fiction writer L. Ron Hubbard, who later founded Scientology. Hubbard claimed that “clearing” (the abreacted purging of traumatic events by Scientology’s techniques) was a discovery he made on his own—after being wounded in battle.34 Not surprisingly, there is no mention of the therapy (which was most certainly cathartic) that he received at the San Diego Naval Hospital in 1943.

Next in this quasi-evolution of cathartic therapies, Joseph Wolpe introduced a graded form of exposure therapy during the 1950s.35 This type of therapy was originally designed for the treatment of simple phobias, such as the fear of heights, snakes, or insects. During the procedure, the person would be shown a spider or made to imagine one several times, gradually moving in closer each time to the “feared object” until the charge was “bled off.” Prolonged exposure therapy, as developed by Edna Foa and her colleagues at the University of Pennsylvania in the 1980s, was built on Wolpe’s prototypic method for eliminating simple phobias. However, in aiming to treat PTSD and other diverse traumas, PE took on a very complex and fundamentally different phenomenon than evidenced in simple phobias. It is predicated upon the idea that after traumatic experiences like IED ambushes, explosions, plane crashes, and sexual assaults, survivors can “overlearn” from the event, allowing fears arising from their trauma to dictate their behavior in everyday life.

I believe the repurposing of a therapy originally designed for simple phobias to treating trauma, which is much more complex, may be a disturbing misapplication of these early methods.

Ray’s Epilogue

Some of us think that holding on makes us strong, but sometimes it is the letting go.

—HERMANN HESSE

A man, when he does not grieve, hardly exists.

—ANTONIO PORSCHE

There must be those among whom we can sit down and weep and still be counted as warriors.

—ADRIENNE RICH

As we saw with Ray, there are other methods for treating trauma that are much less “violent” than PE and that operate in an entirely different way. Somatic Experiencing, the approach I am utilizing here, is not primarily about “unlearning” overlearned outcomes of trauma by rehashing but about creating new experiences that contradict those overwhelming feelings of helplessness.35,36 Ray’s transformation was much more than simply unlearning or understanding his trauma response and thought process. It was about completing (and thereby “renegotiating”) the explosive shock to his body and subsequently “melting” and then processing the frozen emotions of rage, grief, and loss held so deeply in his psyche and soul.

As was demonstrated in the case presentation, the resolution of his “stuck” shock/shutdown involved a gradual revisiting (and completion) of his orienting and hyper-protective responses to the blast. These innate protective reactions included ducking, flexing, and bracing. If we had worked immediately and exclusively with his guilt, rage, and grief, it would have been unproductive at best, or, at worst, counterproductive by potentially intensifying his shock reaction and reengaging a discouraging repetition of his tics and seizure-like movements. Work with procedural and emotional memories requires careful monitoring and tracking of the individual’s bodily responses. These responses include gestures, facial micro-expressions (indicating transient emotional states), and postural adjustments, as well as autonomic signs such as blood flow (vasoconstriction and dilation as perceived by changes in skin coloration), heart rate (identified by observing carotid artery pulse), and spontaneous changes in breath.

The initial session progressed through an important sequence of observation and engagement. The first phase was to note that his gaze was directed away from me and downward toward the floor. It was important, at this point, not to compel or even invite eye contact. This would likely have been further distressing and caused greater shutdown, shame, and disconnection. Phase two consisted of my guiding him into a gradual introduction to his body sensations without permitting this experience to become overwhelming. Phase three involved uncoupling the tightly coiled sequence of neuromuscular contractions that were the aftermath of the successive contractions of his eyes, neck, and shoulders in reaction to the blast. These contractions were the consequence of his body’s attempt to first orient and then defend itself against the shockwaves of the two blasts. This involved contractions of all of the body’s flexor muscles, a reflex probably inherited from our arboreal ancestors: curling into a tight ball is the way baby primates protect themselves when they inevitably fall out of trees. As adults it may also protect against blows to the abdomen.

The segue between phases two and three was carried out through awareness work with Ray’s jaw muscles and then with the guided tracking of his eyes. With these very simple awareness exercises he almost immediately felt tingling, warmth, easy breath, and deep relaxation. Phase three was elaborated over the next four sessions. By the fourth session, the startle (“Tourette’s”) response was nearly absent and so it was possible to begin accessing and processing his emotional memories of guilt, rage, grief, and loss. The final work was done in the context of a group experience at the Esalen Institute. There Ray was able, with the support of group members, to learn how to both direct and contain his rage. This contained experience allowed him to rechannel and transform his rage into strength and healthy aggression—in other words, the capacity and energy to move toward what he needs in life. Finally, this shift opened the portals to his softer feelings of grief and loss, and the desire to emotionally connect with others.

If I had prompted Ray to abreact the explosion of the IEDs with the sounds, smoke, and chaos (as with Morris’s prolonged exposure therapy at the VA), it would have merely reinforced and intensified his startle response and gotten him more deeply locked in his body. Indeed, in 2014, a 60 Minutes program showed a group of soldiers undergoing PE. At the end when the soldier was asked if he felt better, most likely not wanting to offend an authority figure, he replied with something like, “I guess so.” However, for anyone who could read bodies, it was clear that he was in significantly greater distress and had been thrust deeper into shutdown.

If I had pressed Ray to try and deal with his rage, guilt, and sorrow before attending to and resolving his global startle response, it is likely that these intense emotions would have been reinforced, likely leading to retraumatization. Hence, the essential nature of the carefully orchestrated sequence of first attenuating the shock-startle response and then, gradually, with close contact and support from the group, helping Ray to access his feelings and come to peace with them. It is this sequence that made it possible for Ray to transition his attachments and vulnerable feelings to his family, as well as to other vets whom he has touched. This outreach was his new duty. Thank you Ray, truly a proud Marine, for both of your services.

Mother and child reunion: Susan and Jack.

Ray, a proud Marine. This photo was taken when Ray joined the service in 2005.

Ray and Melissa share in the caring enjoyment of their son, while Nathaniel basks in the comfort of this warm attention.

a. In my clinical work, I have observed that children who were born via C-section often have a lack of power when they first attempt standing as toddlers. Then, as mature adults, they often have difficulties initiating actions in the world.

b. While it is, of course, unlikely that Jack understood the precise meaning of my words, I believe that communicating as if he did conveyed more than the words themselves; that it was a reflection of his distress and a recognition that I “got him.”

c. I think Susan’s report demonstrates the formation of pre-logical associational networks (procedural memory engrams), which, as we will see, remained in place when they returned for a two-year “checkup” at age four and a half.

d. To avoid confusion, this process of visually activating the spatial-temporal quadrant of a shock response is not related in any way to the finger movements as used in EMDR.

e. See In an Unspoken Voice for a description of this exercise.

f. This kind of emotional processing couldn’t have occurred without first sufficiently resolving the shock reactions (due to the blast explosions). This resolution transpired, primarily, in my first three sessions with Ray. However, we continued to visit the attenuated residual of these shock reactions, as these echoes faintly reemerged from time to time.