What Are We?

We are photographers, certainly. We create images of people, places, and things, frozen in time and pixels. We learn our craft and do our best to perfect it. We spend money on gadgets we think we’ll use but never do. We spend money on gadgets that we do use. We may have a physical studio that we rent from someone else, one or two rooms in the house we share with our partner and/or kids, or possibly a converted garage that we can call our own.

But we are so much more than just photographers. We are part psychologist because we have to find a way to connect with everyone who sits or stands in front of us and make them comfortable before we direct them to move and smile on command, and enjoy doing it, while we stand in relative comfort, out of the hot seat and in the shadows. We are expert listeners and potential trivia experts, able to add to strings of thought uttered by our clients while moving or adjusting equipment. We are expert talkers as well, able to add to other random, client-voiced ideas. We sometimes must be the Master Sergeant who orders the troops—our clients—into formation, where they stand at parade rest until given orders to do otherwise. We are part editors because we must critique our own worth and eliminate those images we feel the client will not relate to. It’s a tough job, but we’re the only ones to do it. Sometimes, we’re the cheerleaders who let the client know, in no uncertain terms, that he or she is Number One.

We’re also the secretaries, carpenters, messengers, and janitors of our respective businesses. We wear many hats, but one of the most important is that of problem solver. This is one of the reasons why I wrote this book.

As a commercial, advertising, and portrait photographer, I’ve often had to think on my feet to get a job done by the deadline. Clients have a habit of throwing things into the mix, either at the initial conference or at the last minute, that you might not typically be prepared for. Throughout the fifteen photography books I’ve written, I’ve always maintained that you cannot have a bag of tricks too deep for your job. Consequently, I’ve totally enjoyed the challenge when a client throws me a hanging curve ball. And yes, I’m happy to bill for the extra time it takes to hit that ball out of the park.

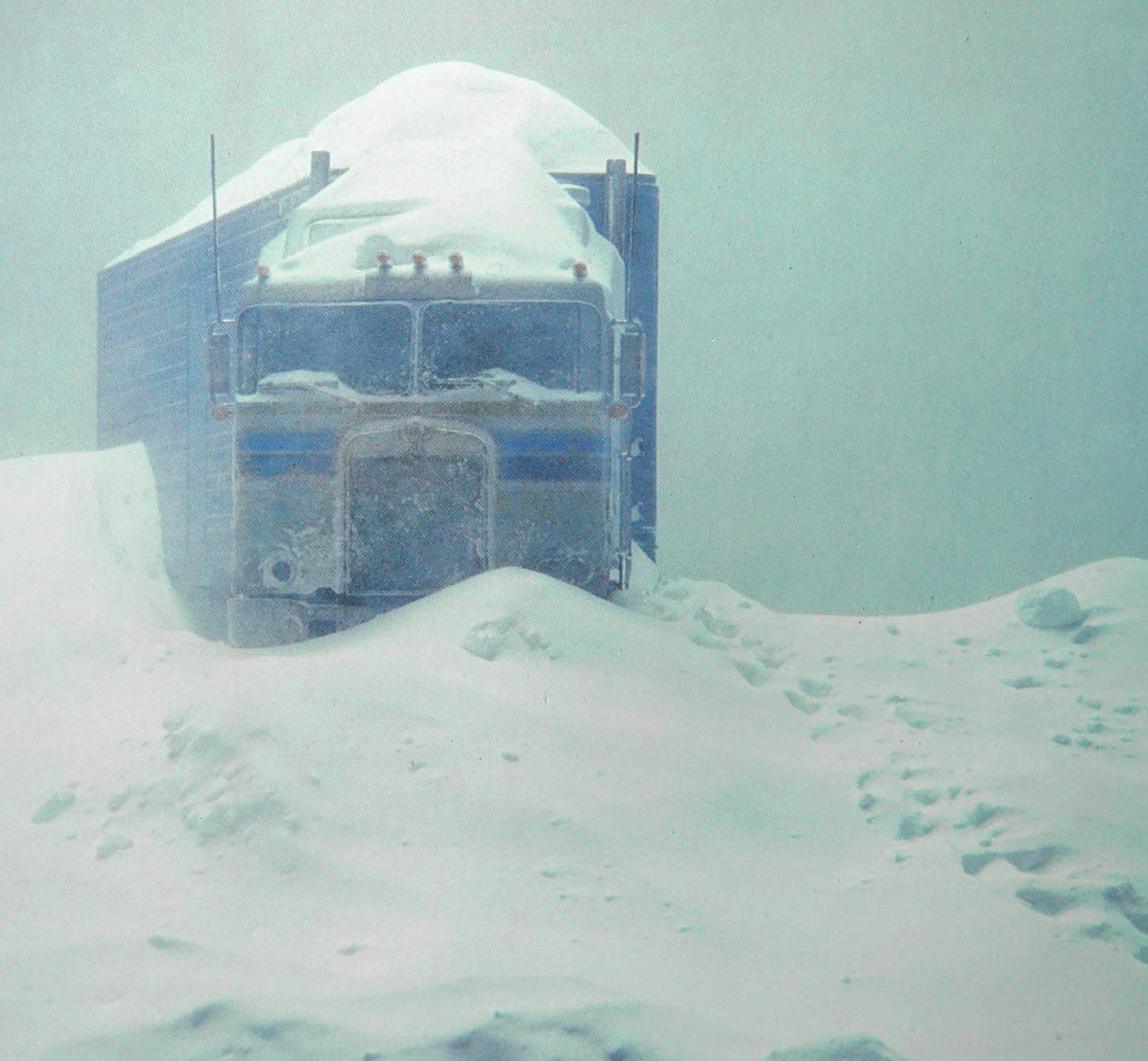

For example, I was presented with this job some years ago in the middle of a hot August. A semi tractor-trailer had to be photographed bogged down in a snowdrift because its battery didn’t put out enough CCA, Cold Cranking Amps, to start the thing in below-zero temperatures.

At the time, the nearest destination with ongoing major snowfall was Peru. With only the budget to go to Wisconsin, we had to come up with a solution. We silently thanked George Lucas and the staff of Cinefex magazine for their behind-the-scenes story of the making of The Empire Strikes Back, especially the part where the AT-ATs (All Terrain Armored Transports) fought in the battle against the Rebellion on the frozen world of Hoth. The huge, lumbering, stop-motion animated machines were walking on baking soda.

I started by buying, building, and painting a scale model of a semi tractor-trailer. I didn’t bother with anything other than the shell because anything that couldn’t be seen just wouldn’t matter.

The set was simple—just a tabletop with a chunk of white foamcore to cover it and another piece of white foamcore behind it to be the featureless, overcast sky.

Once the model was in place, it was aged by blowing grit onto the front, cutting vague wiper patterns on the windshield, and just making it look like it had been a tough day. We built up the basic snowdrifts using baking soda. One of the nice things about using baking soda as snow is that it will “drift” when hit with a fan or the air from a hair dryer.

We threw soda in front of a fan to get the look of a blizzard and shot the image with a 300mm lens at f/16 to give the model the apparent mass of a real truck and not a toy. The “footsteps” from the cab were made by poking a pencil into the soda. It was a simple trick that gave the entire shot a better sense of scale.

This image of a semi stuck in the snow was produced, with a little ingenuity, in mid-August.

Every photo problem has a solution. This image was made on a small set with a model plane, lots of cotton, and an incandescent bulb.

While this is a fun story, the important thing to note is that we created a believable illusion to illustrate the agency’s concept while sticking to the budget. We solved the problem.

Another case in point: My client, a national advertising agency, had been commissioned to create a series of advertisements for an avionics company. As usual, the client, the avionics company, had signed off on illustrated concepts and the promise “we can do it.” Unfortunately, I had not been consulted on the project, which entailed a grand image of an aircraft in flight, silhouetted by the first direct rays of dawn.

Once we decided the problems could be solved and the image would be believable, we got to work. I hired a set builder who was also a pilot to sculpt a blanket of “clouds” out of several pounds of surgical cotton. We anchored the aircraft to a metal rod attached to a base at the floor, through a hole drilled through the clouds. The “sun” was a 100-watt incandescent lightbulb. The bulb was not the source of illumination for the set—that was a job for a strobe in a softbox set on a boom over the bulb. The background—the sky—was blue seamless paper. Turning off all studio and modeling lights made it possible to create the “sun” by using a long exposure with a small f/stop. This image was made in the days before Photoshop, so I had to drag the shutter (see chapter 29) to register the bulb bright enough on the 4×5 transparency film I used.

I wish I could show you the final two-page ad that featured my image, but I do not have the rights to do so. The shot on the page 7, made using the same set but with the addition of a 747-400 model (from another series of ads) will have to do.

Let me tell you a story that may illustrate why it is so important to be a problem solver, an intelligent soul who looks at a problem—perhaps a nonfunctioning background light or any other trouble of that nature—and is able to MacGyver (you may have to look that up) a solution using two paper clips, a mousetrap, and a candle.

Many years ago, I had the absolute pleasure to meet and spend time with the accomplished actor and art historian, Vincent Price. Mr. Price was scheduled to deliver a lecture on contemporary art to a general audience in the auditorium of the college I was attending, followed by a much more intimate discussion, in-the-round, in a smaller room. I was tasked with interviewing and photographing him, and I’ll always remember what a warm and genuine man he was. He unknowingly fostered my about-to-burgeon appreciation for the photographers who shaped our industry and our art.

During the in-the-round discussion, he said that fine art was a reflection of the “art of the masses,” meaning, of course, advertising. There were murmurs of dissent within the crowd until a French foreign-exchange student rose from her seat to challenge him.

“But, that is bullshit!” she exclaimed, as the audience, including Vincent Price, erupted into laughter.

As the laughter died down, he looked at her sincerely, but with a great twinkle in his eye. “My dear,” he said, “Bullshit is the lubricant of commerce.”

I have never forgotten those words, as they have always seemed to sum up what we do. Think of it: We are hired to make people look better than they do. We’re hired to make chintzy products look like a million bucks. We’re hired to make tiny, cramped, four-cylinder cars look like the ultimate driving adventure, and so on.

It is our job to apply the right amount of that lubricant to every job that comes through our doors. How we do it is our business, the crux of our business, and, as long as the results look totally pro, cheaper is better.

Over the years, I’ve developed, discovered, or appropriated (and changed in my own way, I might add) a number of things I lovingly refer to as “cheap tricks.” These are little things, hacks, if you will, that you might do to make certain aspects of your professional life more fun or more manageable. As I’ve often said, a deep bag of tricks is very important to the success of any creative.

Some of the chapters in this book have been reworked from previous books. As Universal Studios was once proud to say at the end of one of their A-list films, “A good cast is worth repeating.” I feel the same way when repurposing some information, though a fair amount of this text is new. In these pages, you’ll find little snippets documenting the tricks I use to make my life easier or to create images that my clients pay for. I like that part the best.

Photographers are tasked with making people look better in an image than they do in real life. We also regularly need to make chintzy products appear luxurious. As Vincent Price said, “Bullshit is the lubricant of commerce.”

Have fun, play with your toys, do good work. Shoot well and prosper.