Introducing a Conversational Model You Can Use with Clients

The real art of conversation is not only to say the right thing at the right place, but to leave unsaid the wrong thing at the tempting moment.

—Lady Dorothy Nevil

Being a wealth management advisor1 is a tough and demanding job! It involves far more than simply a knowledge of the markets and of various financial and investment products. You must also be good with clients—the people stuff! And that means knowing how to cultivate client prospects and build strong and lasting personal relationships based on trust, mutual respect, discerning listening, and a clear understanding of a client’s needs and wishes.

All this may sound straightforward enough to do, but in fact, it requires a deep and sophisticated understanding of human psychology—both that of your clients and of yourself! This will enable you to more deeply empathize with your clients, understand their needs, and anticipate their requests. You will begin to pick up on the unspoken agendas your clients may have had difficulty discussing with other advisers before you.

For that reason, this chapter delves deeply into the principles of interpersonal dynamics and explains how, by understanding these principles, you can gain a new and much deeper understanding of your clients.

I first mentioned interpersonal (group) dynamics and the work of Dr. David Kantor in Chapter One. In this chapter, I discuss his model of interpersonal interaction in greater detail because I have found it to be a valuable tool in understanding my clients and working effectively with them both in low-stakes and high-stakes situations.

What Exactly Are Interpersonal (Group) Dynamics?

Simply stated, interpersonal or group dynamics provides a way to understand the characteristics and patterns of interaction inherent in any conversational system. For my purposes here, a system can be as basic as the relationship you have with one individual client or as complex as the relationship you have with a couple or with all the members of a multigenerational family you are advising.

So what are the key elements of a conversational “system”?

In every human relationship, people have specific ways of talking with each other. They make statements and requests, for example, and ask questions. They also play specific roles.

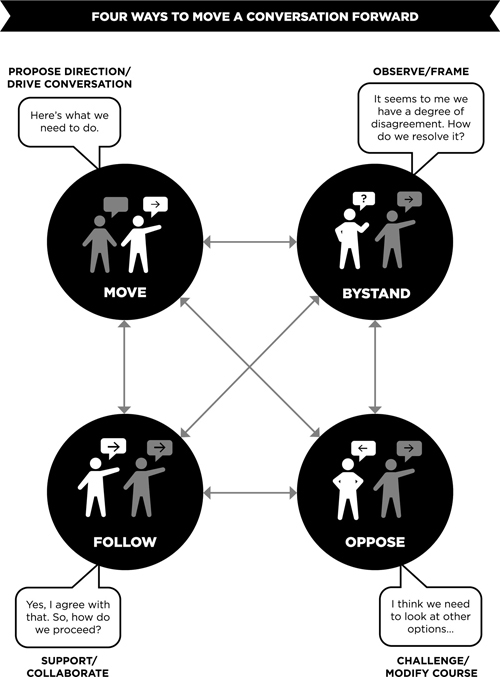

Kantor has identified four principal roles or “action stances” that people play in low-stakes conversations. Movers, for example, tend to initiate action by offering ideas or suggesting specific courses of action to take. Followers are those who support what movers say and tend to keep conversations in a group moving forward. Opposers (not surprisingly) are those who challenge actions proposed by movers. They may resist the suggestions of a mover either because they disagree or because they want to provide an alternative perspective on the matter being discussed. Finally, Bystanders are those who observe the interactions among others in group settings. They offer up neutral comments or bridge the gap between what others say in conversation. They often aim to forge answers or resolution to problems based on different points of view that have previously been expressed by others. In doing so, Bystanders are active conversational participants.

Kantor describes this model as the Four-Player model of human interaction.2 You may already recognize some of your clients as playing one or more of these roles in every conversation you have with them!

Taking a Closer Look at Client Roles (A.K.A. “Action Stances”)

The Mover is the kind of client who is likely to say to you, “I want to examine my portfolio and consider making some changes in asset allocation.” Or, “I like the performance the portfolio has generated in the last nine months, but I’d like to see what we could do to increase returns in the year ahead.” As an advisor it’s quickly apparent when a client is a Mover. He or she is likely to want to drive the conversational agenda when they meet with you (or at least match you in social assertiveness) and may even draw up the proposed agenda for the meetings you have with them!

A Follower on the other hand is somebody who may be inclined to defer to you, at least initially, in client exchanges, especially at the start of a client relationship or when discussing new wealth strategies and investment plans. In response to what you might suggest about portfolio rebalancing, for example, he/she might say something like this: “What you’ve said sounds good to me. Let’s go with it!”

An Opposer as you might guess, is somebody who’s likely to resist your suggestions or at least look for validation of recommendations you are making, or investment strategies and products you may be promoting. He/she may want to review written materials that support your point of view, or research that indicates market and investment trends in a particular direction. Opposers sometimes like to “stress-test” ideas; they look for supporting reasons to pursue a particular course of action, so you want to be prepared for this when you deal with them.

Finally, Bystanders are people who may, on the surface at least, appear a bit passive in client settings, although, in fact, they are simply paying attention to the dynamics taking place among others—or in the case of a one-on-one conversation, between you and them! A Bystander, in my experience, is an impartial observer of a social situation. I think of him or her as a sketch artist who captures not only the action going on in a “scene” of which they are a part but also the underlying moods and color of that scene. By then reflecting back to others the truth of their observations, especially as stakes get higher, the Bystander can be of great assistance in building the central points of agreement within a group. Indeed, he or she can help lay the foundation for group consensus. Having helped build consensus within a group, the Bystander can then adopt other action stances, including that of Mover, Opposer, or Follower, to help move the conversation along. From a group dynamics standpoint, it is very valuable and healthy if Bystanders are encouraged to offer their perspective in group settings (e.g., within a family), as they can often call attention to issues that others are not addressing. In some cases, they can help thwart bad or overly rapid decision-making within groups (or even when part of a couple).

How Clients Communicate Intentions to You

While individuals tend to assume specific roles in conversation, they also tend to communicate with specific (and different) intentions. These intentions typically are reflected in the “languages” of power, affect, or meaning.3

The person (of any type) who speaks in power has an orientation toward responsibility and getting things done. He or she is a person of action, whose goals are efficiency and completion of tasks. He or she is often quite easy to recognize.

Figure 3.1 A Conversational Rosetta Stone: Kantor’s Four-Player model provides a powerful lens through which to observe, understand, and manage interpersonal dynamics.

The person who speaks in affect is focused on feelings and relationships. His/her goals relate to nurturance, intimacy, caring, relationships, and connection with others, and he/she is typically concerned about people’s well-being.

The person who speaks in meaning is oriented toward thinking, logic, and ideas. He or she is focused on the “search for truth” and integrating various ideas into a coherent, understandable, and philosophically complete whole.

So, let’s pause here for a moment to review.

In your conversations with clients in low-risk situations, you’re likely to encounter people who assume the “stances” of Movers, Followers, Opposers, and Bystanders in everyday conversations with you about investing. In so doing, they typically will engage with different intentions—in the “language” of power, affect, or meaning.

So, for example:

A Mover “in power” is likely to say something like this in conversation: “I’d like to use our meeting today to clarify investment goals for the year ahead. Our time is limited, so we need to be focused.”

A Mover “in affect” is likely to say something like this: “I like what you’re proposing today in terms of investment goals. I feel good about them. They will help build a stronger connection between my spouse and me. I’m concerned about the clock, so let’s move forward on this.”

A Mover “in meaning” is likely to say something like this: “Your suggested advice to me today about legacy gifting makes a lot of sense to me. I can see that this now becomes generational in nature. As such, I want it to be part of my wealth management approach for the future. Tell me more what you have in mind!”

A Follower “in power” is likely to say something like this: “I agree with your suggestions. They fit my priorities. Please go over your points in greater detail.”

A Follower “in affect” is likely to say something like this: “I agree in principle with what you’re saying. You know, it’s very important to me to provide for my children and grandchildren. I appreciate where you’re going with this. Go ahead with the discussion.”

A Follower “in meaning” is likely to say something like this: “I resonate with what you’re saying. It makes sense to me to plan systematically for the distribution of gifts over a ten-year period, keeping in mind the complexities of the tax code. I know you’ll explore these intricacies as we get further into our conversation.”

An Opposer “in power” is likely to say something like this: “I disagree for the moment with what you’re saying. I couldn’t agree to what you’re suggesting unless I have more data on which to base a decision.”

An Opposer “in affect” is likely to say something like this: “I’m not yet comfortable that this investment approach will meet my family’s needs or wishes. I feel uneasy about this approach.”

An Opposer “in meaning” is likely to say something like this: “I’m concerned that this approach isn’t really in line with my investment goals and philosophy. You haven’t proven to me the merits of what you’ve suggested.”

A Bystander “in power” is likely to say something like this: “What you seem to be saying is in line with what you’ve recommended before. I see some confusion on your fifth point. Can you illuminate, please?”

A Bystander “in affect” is likely to say something like this: “What you’re saying makes me feel good and corroborates assurances you’ve given me before. I note general agreement in the room with your proposal, although I see some discomfort with your fifth point.”

A Bystander “in meaning” is likely to say something like this: “What you’re saying seems very much in keeping with the philosophy and approach to investing that we’ve discussed before. Perhaps you can give me more detail on your fifth point as it seems to need greater clarification.”

See the subtle differences in messaging in each of the preceding scenarios? An intimate understanding of interpersonal dynamics can help you “code” the conversations you have with clients and make determinations as to the roles and message styles of each of your clients. This, in turn, will help you decide on the role you too must play as part of conversational engagement with a particular client.4

So, for example, if you are dealing with a client who is a strong Mover, with a very clear point of view about something you’re discussing, you may initially want to take the role of Bystander in conversation with him/her, listening to what they have to say, and getting them to articulate their ideas fully. At some point, you may then find yourself taking the Follower role, affirming and agreeing with what they say, and then suggesting a specific course of action to take (putting you in the Mover role).

In another client situation, a high-stakes situation in which a client is aggressively moving the conversational agenda along, perhaps too quickly, you may initially decide to play the role of Bystander so that you can fully discern the context of their concerns and observe the emotions that are fueling the intensity and energy of their words and interaction with you at that moment. Once you’ve read the situation correctly, you might conceivably adopt the role of the Opposer, perhaps to caution the client against taking action that is too rash and not well considered. Example: If he or she says “I want to sell my entire portfolio given what happened in the market today!” you might conceivably say, “I strongly advise against that. I think you’ll regret that decision.”

Given people’s action propensities and the wide range of human personalities, the actual dynamics and texture of any specific human interaction are infinitely varied. And when you factor in people’s engagement style (Closed, Open, and Random) and hero type, interpersonal dynamics become even more complex. These particulars will be covered in Chapters Four through Nine.

The Four-Player model provides a very good framework with which to enter and manage conversations with clients and to help them achieve their goals in both low-stakes and high-stakes situations. It takes a bit of practice to engage with clients this way, but once you master the principles of interpersonal dynamics it will take your wealth consulting skills to a new level and help you to be effective with clients, regardless of the circumstances in which you are counseling them.

Introducing the Behavioral Propensities Profile (BPP)

You may be wondering, “Where does the predisposition to take a particular stance in conversation come from?” As people mature into adults, they develop distinctive patterns (or tendencies) of behavior, engagement, and speech. These patterns became evident in the stances people take in conversational settings, in the words they choose when they speak, and in how they make decisions as conversations with others proceed. Together all these patterns represent a person’s behavioral propensities and form the basis of their behavioral propensities profile (BPP), a personality construct created by Kantor.5

How is an individual’s BPP initially formed? To a large extent it is forged in childhood, in early experiences of challenge, adversity, hurt, and loss. These early experiences of challenge, adversity, hurt, and loss form the basis of a person’s “identity-forming” stories, which, to a very large extent, explain how a person “shows up” in life as an adult.6 I first mentioned “childhood stories” as the foundation of Kantor’s four-stage model in Chapter One. As Kantor notes, they play a critical role in an individual’s early personal development:

Stories are the primary means by which human beings make sense of the world and themselves in it. Each of us is a story gatherer—from birth observing and selecting images as basic references for our ideas about the world, what satisfies our hunger, makes us happy, brings us pain. Story is the device that allows us to store, organize, and retrieve meaning from the images we choose to remember.… Every individual’s patterned behaviors, his or her characteristics in relationships … are based on these images.7

Every one of us walks around with a set of “stories” in our heads that forms the basis of our identity and existence—both to ourselves and to others. Taken in their rich and marvelous totality, these stories represent our connection to this world, to each other, and even to ourselves, helping us to understand who we are in this world. As wealth advisors, we do a great service to clients if we take time to hear and understand their personal life stories, for they hold the keys to comprehending a person’s truest identity. With sensitivity and intention, the advisor who makes it a point to understand a client’s personal life narrative (input that can be gathered at the beginning of a client relationship or during regular client meetings) can gain important insights into what motivates that client as an adult. He/she can begin to understand why they are the way they are, why they embrace certain values and beliefs, why they have a low-risk tolerance or a high-risk tolerance, why they display the behaviors, emotions, and attitudes they do, and why they take particular stances when it comes to discussing matters of money, wealth, life, retirement, and legacy.

When Conversations with Clients Become High Stakes

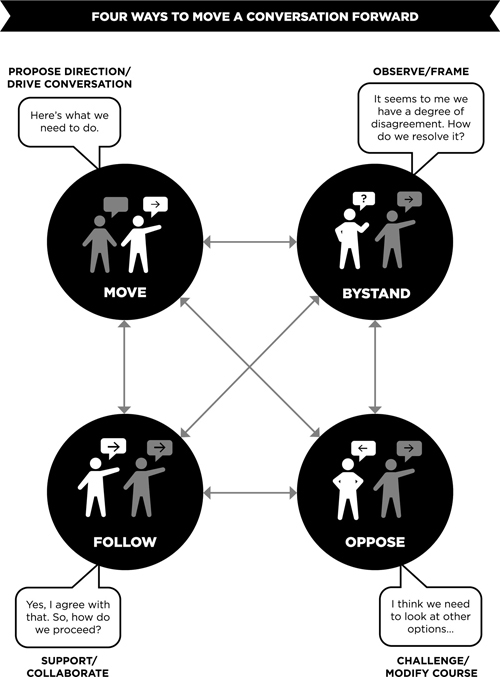

Up to now, I have outlined four conversational stances that clients are likely to display in low-stakes conversations with you or others. And we have touched on the various intentions (power, affect, and meaning) with which people speak in interaction with others. But what happens when circumstances change, and conversations suddenly become “high-stakes”?

This is when a client’s predominant “hero” type (the Fixer, Protector, or Survivor) is likely to emerge in full array. While hero type characteristics are evident even in low-stakes circumstances, they became pronounced and can be problematic to deal with in high-stakes situations. There are many triggers that prompt a person to shift from operating in the “light” or “gray” zone (low-stakes circumstances) to operating in the “dark” zone (high-stakes circumstances.)

Consider the following scenarios:

How Clients’ Personalities Change under Pressure

Each of the preceding scenarios represents a high-stakes situation for a client. Under such circumstances, an individual’s personality takes on new colorations and characteristics. As this occurs, a person’s “hero type” (as a Fixer, Survivor, or Protector) comes into clearer view. The Fixer who was charming and affable in low-stakes situations now becomes demanding, controlling, arrogant, and rude. The Survivor who seemed so reasonable in low-stakes circumstances now seems stubborn and unreasonable, unwilling to listen to your investment advice as the market goes into a nosedive. The Protector, who was always so easy to talk to, and who wanted only the best for his/her family and loved ones, now becomes anxious, may feel like a victim, and even lashes out at you and others.8

Certain behavioral profiles often tend to predispose individuals toward certain heroic stances. The Movers who are oriented toward power, for example, will often reveal themselves as Fixers. The mantra of Fixers is “I will overcome, by sheer will, if necessary.” In contrast, Movers who are oriented toward meaning tend to be Survivors and often display tremendous perseverance and endurance when facing challenging financial or personal circumstances. Meanwhile, the Mover who is a Protector is oriented toward affect and will display great care and compassion for others, even under situations of high stress.9

Figure 3.2 Mood swings in clients. Understanding changes in hero-type behavior as circumstances move from low to high stakes.

I’ll have much more to say about each of the hero types in future chapters. For now, what is important to know is that as a client’s hero type begins to emerge (typically, in high-stakes situations) you need to be prepared. You need to remain grounded and self-aware. You need to carefully observe what’s going on, discern what pressures the client is under, and decide how best to engage that person in conversation at that moment. You need to calmly and confidently read the situation for what it is, and adjust your own action stances in response to the client’s presenting behavior at that time. This requires not only strong interpersonal confidence, but also sharp emotional intelligence, social agility, and the ability to stay very much in the moment with the client.

Understanding Yourself as a System

Up to this point in this chapter I have been talking about your clients—be they individuals, couples, or families—as human systems who tend to display different types of behavior under different life circumstances. I’ve also talked extensively about how an understanding of structural dynamics can provide a robust and flexible framework for dealing with clients under a variety of low-risk and high-risk circumstances.

So now, let’s apply the principles of system dynamics to the conversations you have with yourself—specifically about money and investing. For like your clients, you too are a human system with a unique set of variables and life experiences that inform how you “show up” in the world around you, and how you respond to others in moments of both low and high stress. Like your clients, you too have feelings, emotions, and stories that derive from your childhood, and that have sprung from your life experiences of challenge, adversity, pain, and loss.

Getting in touch with these emotions and stories is critical to do, in order to be optimally effective in eliciting similar life experiences from your clients.

So, let me ask you some questions:

You can see, just from these brief examples, that as a wealth advisor you potentially bring any number of perspectives (a.k.a. “personal stories”) about money and wealth to your role as a counselor to others in managing their own assets.

Advisor Know Thyself!

Quite often, our personal stories about money are inextricably interwoven with other things such as our thoughts about personal security, self-concept, worthiness, success, intelligence, and especially emotional hurt and loss. For example, if, as a child, your family went from living comfortably to living on the economic margin, there are undoubtedly a lot of emotions that you may associate with discussions of money. Conversely, if your family was once of modest means but became wealthy in your childhood, you, your siblings, and your parents all had to “immigrate” to the “land of wealth,” a trip that sounds glamorous, but that, as James Grubman describes in his book, Strangers in Paradise, can be fraught with stress, confusion, family conflict, and loss of identity.10

Your Views about Money and Investing: A Personal Inventory

Given that almost any discussion of money and how a person feels about it can be freighted with emotions and meaning, here are some questions that I invite you to take time to answer. Doing so will help you articulate your emotions and feelings around issues of money, wealth, and investing, and help you come up with an overall philosophy (point of view) about wealth and investment planning. Doing so then provides you with a baseline for working with clients, and helping them to articulate their values and priorities around wealth as well. So, take out a pad of paper and answer these questions:

After you answer the above questions about the past, answer the following as they relate to how you approach your role as a wealth advisor today:

13. As a wealth management professional, what conversation “stances” do you tend to use most often in conversations with others, and in particular clients and prospects?

14. What would you describe your own “hero” type to be in high-stakes situations? Would you say you are a Fixer, a Survivor, or a Protector?

15. What are the values you consider personally important to adhere to in working with clients?

16. What is your “vision” of the wealth management advisory process? How do you think it should work?

17. As a wealth management professional, what are you passionate about? How does this inform your work with clients?

18. What ethical commitments have you made to yourself, as a wealth management professional?

19. How do you currently articulate your advisory approach to clients?

20. How do you build partnerships with clients? What approaches/techniques do you find most effective?

Preparing to Meet the Client

Answering all 20 questions in detail is very good preparatory work for future work with clients. Why? Because if you’re able to excavate the emotions, feelings, experiences and “stories” that you hold inside yourself relative to money and wealth, the easier it will be for you to inquire about and recognize similar or different feelings, emotions, and stories in your clients as part of the investment planning process.

As a wealth advisor, it may be necessary for you to do significant work to help clients unpack all the emotions and feelings they have about money as part of the wealth management and investment planning process. Doing so is critical pre-work for being able to then engage them in thoughtful discussions about their investment goals and wealth management plans.

Conclusions

In this chapter I’ve talked extensively about interpersonal (group) dynamics, and how it provides a model and framework for understanding the nature and texture of the human relationships you have with clients. Mastering the basics of interpersonal dynamics and behavioral profiling can be of tremendous value to you in your work with individuals, couples, and families, and is key to understanding how your clients think, deliberate, and make decisions (either personally or collectively) around wealth management and investment planning matters.

We’ve also discussed the various “action stances” clients typically take in their relationships with you as their advisor—specifically the Mover, the Follower, the Opposer, and the Bystander. And we’ve noted that everybody—both you and your clients—has an “action propensity.” In other words, everyone tends to act in one of the four ways outlined in the model.11

Under pressure or changing market and financial circumstances however, other client propensities can surface in the personalities of the Fixer, the Survivor, and the Protector. As future chapters will show, each brings a different set of issues, expectations, and behaviors to the wealth management process, and each poses unique challenges to you, as the wealth advisor, to deal with.