Understanding Your Client’s Engagement Style

A system is a set of things—people, cells, molecules, or whatever—interconnected in such a way that they produce their own pattern of behavior over time. The system may be buffeted, constricted, triggered, or driven by outside forces. But the system’s response to these forces is characteristic of itself, and that response is seldom simple in the real world.

—Thinking in Systems: A Primer by Donella H. Meadows

Thus far in this book, I’ve talked extensively about clients as psychological “systems” and about how to build strong relationships with them, based on understanding their “stories” and emotional templates. I’ve introduced you to the Four-Player model and the ways you can use it to engage clients, interact with them, and create collaborative working relationships with them. We’ve talked about people’s “hero types” and how a person’s personality traits become pronounced in situations of high stress and high stakes. And I’ve described how different people communicate with different purposes and intents. The client who speaks in the language of power is a person of action who likes to set goals and accomplish things. The client who speaks in the language of affect is focused on feelings and relationships. The client who speaks in the language of meaning is concerned with their life purpose and is oriented toward thinking, logic, and ideas to support their mission in life.

Appreciating all of these things is important in navigating the nuances of client relationships and understanding what makes our clients tick, but it isn’t all you need to build strong and lasting client relationships. You also need to create strong rapport and chemistry with clients by meeting them where they are, understanding their preferred style of social engagement, and adjusting your own style of engagement accordingly. This is essential in building long-lasting client relationships, based on deep trust and mutual understanding.

Every new client relationship begins with the advisor acting as the formal host and convener of that relationship, setting the table for discussion and creating a “safe container” in which conversation occurs, information is shared, opinions are voiced, options are discussed, and decisions are made. To handle this role effectively an advisor must be a deft conversationalist, able to manage conversations with people of widely differing personalities and interpersonal styles.

In my experience, clients generally display one of three possible “engagement styles” when interacting with an advisor.1 These include:

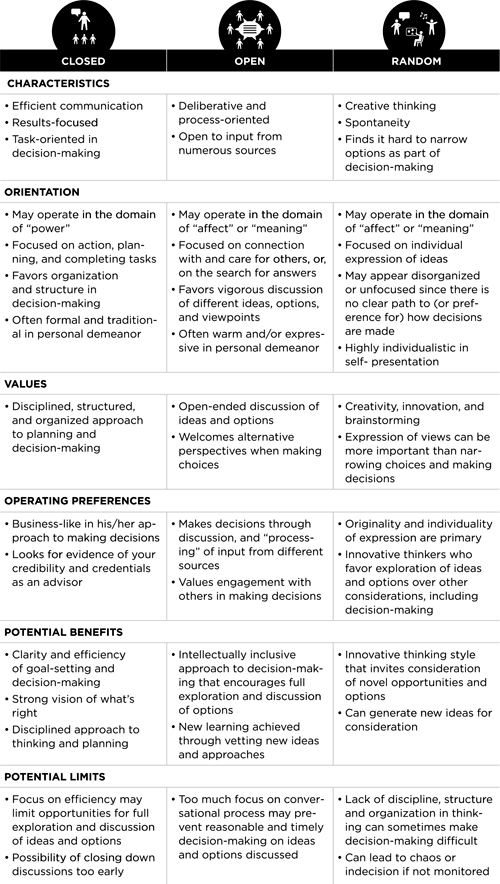

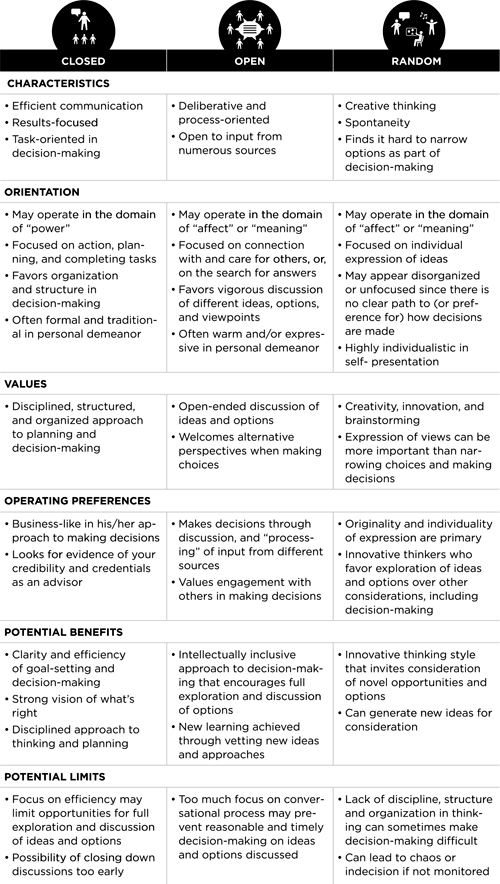

Three Styles of Engagement with Individual Clients3

Open Style. People who prefer an Open style of social engagement typically put a high value on back-and-forth interaction and discussion. They make decisions about things by gathering, discussing, and vetting ideas from different sources, weighing options, and arriving at decisions through careful deliberation and reflection. As an advisor, you’ve undoubtedly had clients who bring this style of engagement to their investment discussions with you. As you work together to define investment goals and implement wealth management plans, such individuals display great openness to new ideas. They’re willing (often eager) to weigh many options, to discuss choices exhaustively, and to make investment decisions in close partnership with you, as their advisor. You often hear such clients talk about the importance of “process” to the decision-making they undertake with you.

Closed Style. People who prefer a Closed style of engagement are less focused on process and inputs and more focused on efficiency, planning, results, and the bottom line. Of the three styles, this style is the most traditional, hierarchical, formal, and structured in its approach to decision-making. This transactional style can be very “black and white” when considering options. You’ll likely recognize clients who operate using this style. They are data-driven, closure-oriented, and like to “cut to the chase” and “bottom-line things” when talking with you and making decisions about investments. Such individuals often come across as all business and are sometimes time-sensitive in their dealings with you. They want to use their time with you efficiently. Professional credibility is very important to such individuals, and they tend to look to you to provide specific subject matter expertise. At the same time, these clients often like to drive conversations and place more importance on completing tasks and identifying/reaching objectives than on the actual process used to make decisions.

Random Style. Individuals with a Random engagement style value creativity, individuality, and spontaneity of expression above all else. In contrast to others, they can come across as having all the time in the world to talk with you. To the untrained eye, Randoms can appear unfocused, disorganized, or distracted when talking with you about investment goals, personal values, and long-term wealth management and estate plans because their interests and priorities can be all over the place. They may have trouble making decisions, given multiple possibilities and choices, and you may be challenged in bringing conversations with them to a close for the purpose of deciding on definitive courses of action. That’s because individuals who operate with a random style have no hard and fast ideas on how to make decisions or review options. As an advisor, you need to bring structure and organization to your discussions with Randoms to facilitate individual, joint, or collaborative decision-making.

Clearly, each of the aforementioned engagement styles requires you to interact with the client in different ways. With the client whose interpersonal style is Open, it’s important to take sufficient time to discuss goals, priorities, and options—“to process”—before the two of you make investment decisions together. With the client whose interpersonal style is Closed, you need to be respectful of time and the client’s desire for “efficient” conversation with you. With the client whose interpersonal style is Random, it’s vital to keep client conversations on topic, to avoid tangents, and to periodically summarize and reframe the goals and objectives of a particular conversation. (For more on the characteristics of clients with each of the three aforementioned engagement styles, see Table 4.1.)

Adapting Your Engagement Style to Your Client’s Personality

It’s critical that you identify the engagement style of your client to ensure a successful working relationship with that person. Once you do, it will provide you with clues about how to adjust your own style to work with them in the most effective way.

Let’s say your own engagement style with others is Open, and you find it relatively easy to work with clients who share this same engagement style. But if your client’s engagement style is Closed, what then? In that case, it may be harder to exert influence, introduce new ideas, build client trust, generate enthusiasm for new investment products, or get the client’s agreement to consider new investment choices, until you first build credibility and establish a track record of success that the client respects.

Table 4.1 Characteristics of the Three Engagement Styles.

If your engagement style is Open, and your client’s Random, you potentially have different challenges. How do you keep the client focused on the investment planning process? How do you partner with a client who may have a million ideas about what to invest in but finds it hard to prioritize options and make actual decisions about investments and estate planning? Because Randoms don’t generally have set ideas about how to make decisions, it’s important for you, as the advisor, to bring sufficient structure and process (including milestones and timeframes) to the work you do with such clients, to facilitate disciplined and effective decision-making.

As noted in Chapter One, an individual’s preferred style of social engagement is formed early in childhood, impacted profoundly by a person’s relationships with parents, family, teachers, religious figures, other authority figures, siblings, and peers. For decades to come, it becomes an integral part of a person’s psyche and emotional template, shaped by specific life experiences of pain and loss and based on response patterns to the external world that were blueprinted at a very early age.4 None of the three styles of engagement—Open, Closed, or Random—is inherently best. It’s important for the adviser to remain nonjudgmental about this. The styles simply offer a predictive model for how an individual is likely to present themselves in conversation with you.

Understanding Your Own Engagement Style

Identifying the engagement style of your clients is one thing; identifying your own preferred engagement style is another. How do you determine yours? For starters, listen to yourself talk at your next client meeting. Does the structure of your sentences and style of engagement show the characteristics of an Open, Closed, or Random style? (See Table 4.1.)

To gain personal insight into your own engagement style with others, think back to your family of origin. What was the culture of your family system like? Was it

My own family system was characterized by a Closed communications style. It was hierarchical and highly organized. Perhaps my parents saw no other way to run their household, given that they had five rambunctious boys to raise, whose birth years spanned almost 15 years!

In any case, my preference for operating using an Open communications style was in direct reaction (and rebellion) to having grown up in a regimented environment. As a young adult, I made a very conscious decision to adopt a different engagement style and also developed Protector tendencies (more about these later) in response to the arbitrary and often ruthless behavior of my parents, especially my father.

The Role of Engagement Style in Building Successful Client-Advisor Relationships

Harmonizing your style with that of your clients calls for careful observation and determination of their style, as well as social and interpersonal agility on your part, using appropriate language, vocal tone, action stances, and communications intent (power, affect, or meaning) to establish rapport, build trust and understanding, and forge the foundation of a strong mutually respectful working relationship. Doing this is both a science and an art. Kantor’s systems dynamics model may be research-based, wonderfully nuanced, and shed light on the multiple dimensions involved in any functional human relationship. But building real connections with others is also creative work, requiring you to act on intuition, take risks, read social cues and clues, and improvise and experiment, all in the service of working through the kinks that are inevitably involved in establishing close working relationships with others.

Form, Storm, Norm, and Perform

Did you know? When groups first start working together they must go through a process of forming and storming before they can effectively norm (work together) and then perform as a group.5 The same holds true for the relationships you have with your clients—whether that client is just one other person, a couple, or a family. The early stages of establishing a relationship involve a sifting and sorting process, as personalities interact, roles are defined, trust and rapport are created, and norms of communication and behavior are established between the parties. Sometimes elements of “struggle,” ego, and the quest for dominance are also involved. Be mindful of all these dynamics as you begin new relationships with clients, because the relationship-building process should not be rushed. Indeed, you owe it to yourself, to your client, and to the professional relationship the two of you are building to establish that relationship based on mutual respect and strong professional and ethical understandings.

When Building Client Relationships Is Difficult

While building strong and healthy working relationships with clients is essential to your professional success (and that of your client), it isn’t always easy to achieve. For example, it’s very difficult to establish strong and healthy working relationships with clients (individuals, couples, or families) where there is a history of long-term family dysfunction, hostile co-dependency between parties (e.g., between spouses/partners), or in situations where individuals display symptoms of mental illness, traumatic brain injury, pathological distrust of outsiders, physical or emotional abuse, substance abuse, or other psychodynamic factors. If you perceive such dynamics at play in dealing with particular clients, proceed cautiously and carefully. In some cases, it may be critical to involve other family members to provide a psychological support system to the client whom you are advising.

Getting an early read on the psychological healthiness of your client, be it an individual, couple, or family, should always be a top priority. After all, you and the client will be working on issues with tremendous implications for the client’s welfare, and his or her judgment and decision-making abilities will be key to a successful working relationship with you.

So, how do you gauge the psychological healthiness of your clients and your ability to connect with them? While doing this is critical when working with individuals, it becomes even more important when dealing with couples and families where system dynamics are more complex.

The pioneering family therapist Carl Whitaker, in his early research and observation of individuals, couples, and groups with whom he worked, found that healthy, functional human “systems” (be they individuals, couples, families) are those in which the possibility and potentiality of change and growth exists for the individuals involved in that system.6 Functional systems can thus be defined as healthy (my word) if and when they support an individual’s personal growth, development, and self-direction. The possibility of individuation (again, my word) exists when an individual (or individuals) within a system has or develops the capacity to act independently of past history and action, to transcend past roles in a family system, to display independence of thought, and to assert personal agency (i.e., act for themselves).

Conversely, Whitaker would likely describe as unhealthy an individual, couple, or family system where an individual (or individuals) seems incapable of personal growth, development, and change. Examples of such arrested development include a grown adult in a dysfunctional family system who is unable to assert independence of thought or action, because of his/her decades of enmeshment in the culture of that family system; an abused or battered spouse who is unable to leave a toxic relationship; or the wife in a traditional marriage who is unable to grow personally and psychologically into the role of financial steward on the occasion of her husband’s death or deteriorating mental and physical condition because she never learned to be an independent actor in her decades-long marriage.

In my experience, Whitaker’s early work with systems (functional and otherwise) has tremendous implications for our advisory work with individuals, couples, and families because assessing the psychological health of a client system is critical to our ability, as advisors, to work with such clients.

Meet the Schibasky Family

Consider the case of the Schibasky family of Aurora, Colorado, with whom I worked about 15 years ago. Stuart Schibasky (the family patriarch), age 62, had always been the chief financial officer of the family assets. It made sense, as he’d been head of a highly respected trust company in Denver. His wife, Alissa, also age 62, happily complied with this arrangement, feeling that she was well taken care of financially and emotionally by her husband. The couple’s five children also felt secure in this arrangement, even after they left home, finished college, and started their own careers and families. Indeed, they felt safe knowing Dad was in charge.

Stuart wound up taking early retirement. Alissa was initially pleased with this decision because it afforded them the opportunity to travel. But shortly after Stuart retired, some red flags appeared. The couple’s spending habits, always a bit on the extravagant side, became over-the-top outrageous. Ultra-luxury items began appearing in the home, the garage, and as accessories on Alissa’s arms. Gambling excursions, several ultra-exclusive vacations, expensive artwork—even money transfers to foreign banks following receipt of Russian and Nigerian emails pleading for help—ensued. Stuart seemed happy-go-lucky, almost oblivious to the reality that he was no longer working and needed to budget the couple’s spending because of their reduced income. Finally, the truth came out when Stuart’s annual physical revealed that he had early onset dementia, which had adversely impacted his executive functioning skills.

It was at this difficult, crucial time that I was retained by this concerned family to help it come to grips with the new realities now facing all of them. Suddenly, Alissa was thrust into a new role of handling the family’s books and paying bills. She needed extensive help with these new responsibilities because she had never had to deal with these tasks before, and she found them quite daunting. The first priority was to get control of the couple’s assets away from Stuart. This meant financial upheaval as accounts were closed and credit cards were taken away. At the same time, we needed to find in-home care for Stuart and employed home health care aides to eventually provide 24-hour care. (Eventually, Stuart’s health declined so much that he was moved to a nearby assisted living facility.) Little by little, Alissa began to get control of and rein in the couple’s expenses. She had to carry the entire burden herself, with my firm providing assistance in paying the larger bills. She showed incredible fortitude in taking on these duties, and she earned my great respect.

The children, interestingly, felt ambivalent. They were surprised at their mother’s transformation but also concerned about her long-term ability to manage the couple’s complex finances. Would their parents run out of money? Where finances most affected the five Schibasky children was in the decision Alissa made (with my assistance) to scale back gifting to each of them. This created a psychological shock wave in the family at first, as the children had to re-adjust their expectations regarding inheritances.7

As I worked with the Schibaskys, I found myself embroiled in a very tricky set of family dynamics. My job, as Bystander, was to explain to Alissa how protective her children felt toward her, while also telling the children how impressed I was with all that their mother was doing. Playing this mediating role proved crucial in this family’s life at this moment, because it enabled each party to appreciate the other in new ways and kept family members from taking on hardened roles that would not have been useful to them or to the family system. However, I found it was easy to overstep my bounds, as I did once by telling one son that he needed to reduce his spending. This was not taken well. I was not his father, whom he missed deeply. There was no way I was going to fill his shoes.

To the extent I ultimately proved successful, my role with this family—whose culture generally reflected an Open engagement style—was to apply sufficient “grease” to the system so that the parts could work more easily than they might have otherwise. This involved facilitating communications among the five Schibasky siblings and also convening several sessions involving both Alissa and her children, so that “the kids,” in Alissa’s words, “would all be on the same page with regard to my wishes, needs and priorities.”

Adjusting Your Style of Engagement, Based on the Client’s Engagement Style

While the Schibasky family’s engagement style was Open, it could just as easily have been Closed or Random. Had it been closed, it would have been much more complicated to engage family members about a discussion of Stuart’s needs, because they might have initially taken the attitude that there was nothing they could do. Stuart would have resisted help and even refused to acknowledge his deteriorating health. And Alissa, confronted by her husband’s deteriorating health, could have played the role of helpless wife and kept her children uninformed and of no help to her.

Conversely, had the engagement style of the family been Random, the children would have long since gone their own ways and distanced themselves years before, in pursuit of their own goals and lives. It’s also likely that they would have failed to achieve any kind of sibling consensus or alignment around how best to deal with their aging parents.

Families, of course, can mean a couple and a child, or it can mean 30 or 40 people meeting in a room together. Group dynamics change as you add players to family wealth management discussions. Besides differing agendas, the more family members you have, the greater the diversity and complexity of engagement styles at play in that family system.

In such situations it falls to you, as the advisor, to facilitate and “broker” communications among parties. This is where your ability to stay emotionally detached, and to initially play a Bystander role—framing and reframing discussions and facilitating connections among people (perhaps across multiple generations or family branches)—becomes critical.

Because of all the psychodynamics involved in a family system, when you first begin working with a wealthy family, it’s important to learn as much as you can about all of the family members and their relationships to one another. Each is a stakeholder in the family system, and it’s important to understand the motivations and engagement styles of each to the fullest extent possible.

In-depth, one-on-one discussions before full family meetings can help you prepare to broker the perspectives of all family members. In family meetings, discussion of genealogy can stimulate discussion of a family’s unique history, values, and goals and help align family members of different generations around common wealth management and investment objectives. This can be particularly important to do in a multigenerational situation, where members of the family’s wealth creation generation seek to connect better with younger family members who may be Millennials, Gen-Xers, and Gen-Yers.

Large family meetings held to discuss investment and wealth management topics are quite stimulating and eye-opening for all the participants involved. They often reveal simmering intra-family jealousies, sibling rivalries, divergent family values, opposing financial objectives, and much more. Conversely, they can also help forge close relationships among family members of different generations. When I’m involved in facilitating such meetings, I often ponder how many people might actually be in the room if we included ancestors from all previous generations as well as the family’s youngest members. The roles and accomplishments of ancestors figure prominently in the DNA of many modern wealthy families and, if adroitly invoked, can help multiple generations of a family to discover familial roots and values they share in common.

The Harrisons

Some years ago, I had occasion to work with the Harrisons, a multigenerational family based in California that was very much in disarray following the death of the family’s patriarch and original wealth creator. The family governance system had fallen apart. This family included four generations of family members. As a controlling personality, the patriarch had been close to two of his children for many years before his death, but had nonexistent relationships with his two other children, one of whom was gay. As part of his final wishes, I was asked to become involved and help the family come back together after his death and forge common wealth management goals for the family’s future.

I was approached by the two grown children closest to the patriarch and asked to convene and then facilitate a family meeting. Part of my mandate was to “set the table” for all the parties involved, and help them work through what, in some cases, were years of misunderstandings and feelings of hurt, exclusion, and estrangement. Over a period of 18 months, I worked closely with the four siblings of the patriarch and with their own families as well. The work consisted both of large group meetings and numerous small group and one-on-one meetings with the patriarch’s four grown children and in some cases their grown children.

Ultimately, working together, we were able to chart a future direction for the family’s investments. We also reviewed and revised inheritance plans and strategies for multiple generations of the family, worked to create better communication and transparency among the various branches of the family, and built a stronger climate of trust and alignment among the patriarch’s four grown children. I’m pleased to say that the patriarch’s four children ultimately were able to repair their broken relationships from years past. Two siblings who had not spoken in ten years put their past estrangement behind them, and the gay son, long a black sheep, was welcomed back into the family, along with his long-time partner and their two adopted kids. In addition, the patriarch’s four children agreed to review the family’s investment strategies and goals on a regular basis, and also agreed on communications plans for discussing these goals with each generation of children as they reached the age of majority.

The Harrison family ultimately was able to come together and work collectively to establish future family wealth management goals, in large measure, because the four siblings were able to put the family’s unpleasant past behind them and rethink their relationships with one another. As siblings, they were willing to “rewrite their family’s DNA” in order to forge new relationships and to intentionally and systemically transform how the family operated.

Unfortunately, not all families are as functional as the Harrisons. Sometimes wealthy families have internal feuds or become conversationally paralyzed when making investment and estate planning decisions after a major family patriarch or matriarch, who served as the family’s emotional glue, has died. Consider a family in which a Random engagement style predominates. In such a family system, establishing a method of governance can be a big challenge. While family members may have robust discussions about disposition of the family’s wealth, there may be such a divergence of views expressed that the family can’t easily reach consensus about a course of action to take.

In such cases, the advisor must be careful not to become emotionally involved. Instead, he or she needs to remain as much of an objective observer and arbiter as possible, to assess the system dynamics at play in the family, and to develop strategies for dealing with a large family group.

I have found that, in situations like this, the Four-Player model again becomes a powerful tool that can be used to help shape a group’s decision-making. By taking the Bystander role initially, an advisor can serve as the convener or “host” of family discussions. At some point in that process, it then becomes possible for him or her to assume a Mover stance, introducing aspects of more Closed systems such as goal setting, option reviews, and milestones for completing specific work tasks. Advisors can supplement these efforts with the use of meeting agendas, performance reviews, visioning exercises, and asset allocation discussions, all of which anchor family meetings in discussion of practical, concrete wealth management priorities.

See how complex and multifaceted the dynamics in family systems can be?

Although advising families is complex work, so too is working with couples. Often a husband and wife (or the two partners in a same-sex relationship) will display different engagement styles. One partner might prefer a Closed engagement style, and the other an Open style. These differences might have attracted the two individuals to one another when they first met, but now these differences may be a source of stress within the relationship. A wife might have loved how competent and in charge her husband was when they first met. But, today she may resent his controlling nature. Meanwhile, the husband may have enjoyed having his wife be so dependent on him during his working years, but now that he’s retired he may resent her for relying on him so completely—financially and emotionally. Understanding such dynamics when working with couples is crucial if you are to serve effectively their common financial interests.

When I first begin working with a couple, I pay close attention not only to the ways in which each half of the couple talks to me but also to how they talk to one another. I can discern a great deal about a couple’s relationship by observing their body language, their vocal inflection and tone, the way they sit in each other’s presence, and the distance or closeness between them when I meet with them. At times, a couple’s relationship almost becomes another party to the discussions. Do the two members of the couple use the same engagement style in talking with each other? Or do they seem to clash in this area? A husband perhaps is exhibiting a Closed style, while the wife shows an Open or Random style, or vice-versa.

As an advisor, I often become a mediator when working with couples and families in which the clash of engagement styles has the potential to generate conflicts, create misunderstandings, or cause communications breakdowns. In such instances, an advisor sometimes must step in to “referee” discussions so that sound financial decisions about retirement, investment planning, and estate management are possible.

Bringing Self-Reflection and Mindfulness to Your Work with Clients

Regardless of who your client is, know that you are part of the client, couple, or family system with whom you work. Many advisors would take issue with this, but I would argue that simply by being in the room with your client you inevitably become part of the conversational system. So, what can you do optimize your working relationships with clients?

Here’s a checklist of items to attend to:

Become Fluent in All Three Communications Styles

As you grow increasingly familiar and comfortable with your own engagement style, understand its strengths and weaknesses. Commit yourself to becoming a student of human nature when you work with clients and to developing a facility with all three of the engagement styles I’ve discussed in this chapter, based on the style that the client displays to you. You may also want to familiarize yourself with other tools and models for understanding social styles, including the Social Styles matrix developed by Wilson Learning of Eden Prairie, Minnesota.8 As an advisor, I have found that the more I’m able to operate using all three engagement styles, as situationally appropriate, the more easily I’m able to connect with different client types and with a larger variety of clients. I will provide more insights on dealing with different client types when we get to the next chapter of this book, which deals with Fixers, Protectors, and Survivors.