TWO

ANDREW JOHNSON SURVIVES

Andrew Johnson’s presidency was born in crisis. The Tennessean became the United States’ 17th president upon the assassination of Abraham Lincoln on April 14, 1865. He had been selected as Lincoln’s running mate by the Republican Convention in June 1864, replacing the sitting vice president, Hannibal Hamlin.

In making this unusual move, which Lincoln privately endorsed, the party sought to bridge two divides: Unlike Lincoln, a Republican from a Union state, Johnson was a Democrat from a Confederate state. As the only United States senator from a secessionist state to remain in Congress (until Lincoln appointed him military governor of Tennessee), rather than resign and join the Confederacy, and having openly denounced secession as treason, Johnson had credibility with Republicans and his presence on the ticket figured to attract Southerners and Northern pro-war Democrats. He and Lincoln campaigned not under the banner of the Republican Party but as the National Union Party, and won election easily in November.

Johnson’s tenure as vice president got off to a shaky start. He showed up at the inauguration drunk, and did nothing to conceal this condition during his long and rambling speech. The reputation of the rough-hewn, uneducated Johnson never fully recovered, though the ever-conciliatory Lincoln forgave his partner the transgression, calling it “a severe lesson for Andy, but I do not think he will do it again.”1 Johnson justified Lincoln’s faith, serving him loyally and serving his purpose as a unifying figure.

But if Johnson’s term as vice president promoted unity, his ascendancy to the presidency had the opposite effect. For Republicans, devastated by Lincoln’s assassination to begin with, it was a bitter pill to see the opposition party handed the White House just five years after the Republicans had attained it for the first time. It made matters much worse that the new Democratic president didn’t share their vision on the major issue of the day, an issue at the heart of a recently concluded war that had claimed 620,000 lives.

The so-called Radical Republicans, who controlled both houses of Congress, saw little room for compromise when it came to racial justice. They thought Lincoln’s plan for Reconstruction insufficiently aggressive, but they admired his steadfast prosecution of the Civil War and expected to work with him in its aftermath. They planned to condition the return of Confederate states to the Union on those states’ willingness to give black men full political rights. Following Lincoln’s assassination, the Republicans suddenly had to deal with an openly white supremacist president who had been a slaveholder and lacked Republicans’ vision of Reconstruction.

Initially, Andrew Johnson seemed accommodating. He kept Lincoln’s cabinet, and sounded conciliatory notes about his intention to work with Congress across party lines. Even ardent abolitionists such as Charles Sumner, the militant Massachusetts senator, pronounced themselves pleased with the new president. To be sure, not all Republicans shared that view. Some, including members of Congress, believed Johnson complicit in Lincoln’s assassination. It didn’t take long for major divisions to develop between Johnson and those Republicans who initially gave him the benefit of the doubt.

Johnson favored extending the vote to literate, tax-paying freedmen, but maintained that “it would not do to let the Negro have universal suffrage now; it would breed a war of races.”2 He insisted the matter be left to the states, a position anathema to the Radical Republicans, who wished to deny reentry into the Union to any states that refused to give black men full voting rights. Naturally, Johnson also opposed a more far-reaching proposed constitutional amendment, a forerunner to the 14th Amendment, requiring states to give black people equal protection of the laws. He also vetoed a bill extending the Freedmen’s Bureau, which assisted former slaves, as well as a Civil Rights Act, which defined national citizenship to include African Americans and gave them various rights, such as acquiring property, making contracts, and testifying in court. Johnson pardoned countless Confederate leaders over the objections of the Radical Republicans.

The division within the federal government mirrored and exacerbated divisions in the country at large. Race riots broke out. In several states, including Johnson’s home state of Tennessee, mobs of white men killed dozens of black people. Predictably, Johnson and the Radical Republicans each blamed the other for the violence.

In the fall of 1866, Johnson traveled the country (his so-called “swing around the circle”) to make a series of inflammatory speeches attacking Congress. Radical Republicans returned the favor, refusing even to refer to Johnson as the President. Instead, he was “The Acting President,” “His Accidency” or “His Vulgarity.” Republicans won the battle for public opinion. In the midterm elections that November, the Radical Republicans substantially increased their majorities in both houses of Congress.

They almost immediately sought to exploit their growing power. In January 1867, triggered by another controversial Johnson veto, this one of a bill giving black men the vote in the District of Columbia, the House Judiciary Committee commenced an investigation into Johnson’s conduct with an eye toward impeachment.

The long investigation included an extensive effort to locate an allegedly treasonous letter from then-Governor Johnson to Jefferson Davis, president of the Confederate States of America, but it turned out that the letter did not exist. The committee also pursued evidence that Johnson was part of the conspiracy to assassinate Lincoln. At its final hearing, 10 months later, the committee called as a witness one of its own members, Ohio congressman James Mitchell Ashley, who claimed to have evidence, which he failed to produce, implicating Johnson in the Lincoln assassination. Under skeptical questioning by Democratic congressmen, Ashley acknowledged that he believed that several presidents had been poisoned by their vice presidents (successfully in the cases of Zachary Taylor and William Henry Harrison).

The threat of impeachment did not faze President Johnson, whose considerable flaws did not include timidity. After meeting Johnson, no less an authority on character than novelist Charles Dickens declared him “a man not to be turned or trifled with. A man (I should say) who must be killed to be got out of the way.”3 The leading Radical Republicans matched Johnson’s determination, setting them on a collision course with him.

Throughout 1867, the chasm between Congress and the president widened. Congress passed the Reconstruction Act to give the federal government power to suspend state officials who impeded Reconstruction and to require former Confederate states to hold constitutional conventions dedicated to establishing racial equality. Johnson vetoed the bill; Congress overrode the veto. This was the first of 15 Johnson vetoes to be overridden, an event which until then was practically nonexistent. For the preceding 16 presidents, only two had vetoes overridden. The total number of overrides before Johnson was six. His total of 15 remains unequaled to this day, even though he served less than one term.

President Ulysses S. Grant

The most consequential battle between Congress and the Johnson White House involved the Tenure of Office Act, which required the president to get the Senate’s consent before removing any officials whose appointment required Senate confirmation. This measure could lock in place Johnson’s cabinet, all members of which were Lincoln carryovers, some of whom supported Congress’s aggressive approach to Reconstruction. Moreover, the Tenure of Office Act specified that failure to abide by its terms constituted a crime as well as “high misdemeanor.” It was, in other words, impeachment bait. Congress passed it on February 18, 1867, and Johnson vetoed it on March 2. Congress overrode the veto the next day.

The new law posed no immediate issue, but over time Johnson grew wary of some members of his cabinet, especially Secretary of War Edwin Stanton. Stanton sided—and perhaps colluded—with the Radical Republicans in most of their battles with Johnson. On August 12, Johnson suspended Stanton while Congress was in recess, and appointed General Ulysses S. Grant as an interim replacement. Stanton replied to notification of his suspension by claiming that the Tenure of Office Act protected him from removal, but in light of Grant’s acceptance of the interim position, “I have no alternative but to submit, under protest, to superior force.”4

Meanwhile, after its wide-ranging investigation, in November the House Judiciary Committee, by a 5–4 vote, passed out of committee a resolution to impeach President Johnson. The yes votes were cast by Radical Republicans, with two moderate Republicans and two Democrats opposed. The majority report located impeachable offenses primarily in Johnson’s improper use of his veto power and pardon power. A dissenting report by the two Republicans stated dissatisfaction with Johnson’s policies but claimed the absence of any impeachable offenses. The Democrats’ dissenting report praised Johnson for protecting the United States from internal enemies.

The resolution went to the full House in December. After very limited debate—just two speeches on each side—the House rejected impeachment overwhelmingly by vote of 108–57. Opponents of the resolution successfully argued that Johnson could not be impeached since no crime on his part was even alleged.

In the meantime, much background maneuvering took place with respect to Johnson’s suspension of Stanton. The Tenure of Office Act appeared to require Johnson to get the Senate’s consent before discharging Stanton, but he had only suspended him, not discharged him, and Congress had not been in session. On January 10, 1868, General Grant informed Johnson that, if the Senate did not concur in Stanton’s suspension, he would resign his interim appointment. A few days later, the Senate passed a resolution instructing the president to reinstate Stanton. Four days later, Grant abandoned his office and Stanton returned to it.

On February 21, 1868, President Johnson fired Stanton and replaced him with Major General Lorenzo Thomas, a well-regarded career military man. That evening, the Senate adopted a resolution declaring that Johnson lacked the authority to take these actions. Three days later, the House voted 126–47, by straight party vote, to impeach the president. Meanwhile, Stanton hunkered down in his office in the War Department and had Thomas arrested by federal marshals. After posting $5,000 bail, Thomas marched over to what he considered his rightful office, only to be rebuffed by Stanton. A frustrated Thomas retreated to the White House to inform Johnson of the stalemate.

A House select committee quickly drafted and approved nine articles of impeachment pertaining to the firing and attempted replacement of Stanton. The committee rejected an article proposed by Massachusetts congressman Benjamin Butler concerning the incendiary speeches President Johnson made the previous year. The full House then adopted the nine articles and appointed seven “managers” to serve as the prosecution team during Johnson’s trial in the Senate. Butler, one of the managers, persuaded his House colleagues to reconsider and adopt the proposed tenth article. It said that Johnson’s speeches violated “the dignities and proprieties” of his office and destroyed the “harmonies and courtesies which ought to exist and be maintained between the executive and legislative branches.”

Leading abolitionist Thaddeus Stevens proposed an eleventh article, which reiterated the charges in the other articles and added allegations based on a speech Johnson made in August 1866 supposedly asserting that Congress lacked the power to make laws (because it was a Congress of only some states) or propose constitutional amendments. Article 11 of the articles of impeachment declared that, by promoting his deficient understanding of the Constitution, Johnson dishonored his oath to faithfully defend it. The new article also passed overwhelmingly.

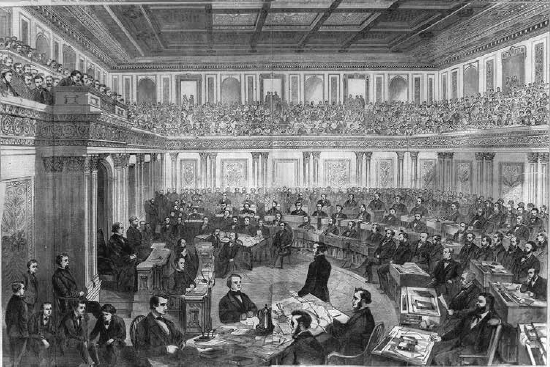

On March 5, 1868, the Senate commenced the first presidential impeachment trial in U.S. history. Indeed, there had been just a handful of prior impeachments of any federal officials, and only a single conviction. That case merits an asterisk in the historical record: Judge West Humphreys, impeached and convicted for joining the Confederacy, had long abandoned his post and did not appear at his trial or contest his prosecution. Humphreys was tried in absentia and found guilty after a trial that lasted a single afternoon.

The chief justice presiding over the trial of Andrew Johnson was Salmon P. Chase, which illustrates that foresight by the drafters of the Constitution could do only so much to ward off problems. They provided that the chief justice would preside over a president’s impeachment trial in order to avoid the vice president’s conflict of interest. But Chase was a presidential wannabe who had sought the office in 1860. President Lincoln selected him as secretary of the treasury (and later appointed him to the Court) as part of his “team of rivals,” but kept a careful eye on his ambitious underling. Lincoln correctly surmised that Chase would never relinquish his desire to be president. Even as he presided over Andrew Johnson’s impeachment trial, Chase was angling for the Democratic presidential nomination—surely an easier task if the incumbent president was removed. So much for avoiding conflict of interest.

The Senate as a court of impeachment for the trial of President Andrew Johnson. Sketched in 1868 by Theodore R. Davis.

Yet one cannot assume that Chase wished to see Johnson convicted, and some perceived otherwise. On March 4, the eve of the trial, Chase hosted a reception at his home and Johnson made an appearance. Newspaper reports of his attendance rankled anti-Johnson partisans.

Chase was hardly the only participant in Johnson’s trial whose impartiality was questioned. The senators to try the case included Chase’s son-in-law, William Sprague (from Rhode Island), and Johnson’s son-in-law, David Patterson (Tennessee). While few registered complaints about their involvement, the participation of Ohio’s Benjamin Wade, the president pro tempore of the Senate, became a major source of contention.

If Johnson were removed from office, Wade would assume the presidency. The Constitution failed to provide for the circumstance of the vice president succeeding to the presidency and leaving the vice presidency vacant—a problem not fixed until adoption of the 25th Amendment a century later. Thus, when Andrew Johnson became president upon Lincoln’s assassination, the vice presidency stood vacant. Meanwhile, a founding-era statute put the president pro tempore next in the line of presidential succession.

It was no accident that Wade, a bold leader of the Radical Republicans, occupied the office of president pro tempore. When it became vacant in March 1867 upon the departure of a senator defeated in the November 1866 election, everyone knew that the Senate’s new president pro tempore could soon end up in the White House. The House of Representatives had already attempted to impeach Johnson once, and had by no means given up on the idea. For that reason, the Republican-dominated Senate chose Wade over fellow senators considered too moderate for the taste of the Radical Republicans. Wade mildly protested that he was not suited for the job (“I am no parliamentarian”),5 knowing full well that his colleagues had in mind for him a different job down the line. Indeed, Wade supposedly had his future cabinet picked out. To complicate all the potential conflicts of interest, Chief Justice Chase was believed to be hostile toward Wade and therefore inclined to tip the scales toward acquittal.

The swearing in of the senators by Chase on March 5 proceeded alphabetically, which meant most of the senators had been sworn in by the time Wade stepped up. Before he could take the oath, Democrats rose to object that his conflict of interest should disqualify Wade from participation in the trial. The Senate halted the swearing-in process to take up the question. More than 20 senators weighed in. Those who defended Wade’s involvement pressed the point that Andrew Johnson’s own son-in-law would be among the senators deciding the case. Ohio’s John Sherman, the younger brother of the great General William Tecumseh Sherman, argued that to remove his fellow Ohioan would deprive their state of full representation at the trial.

At the completion of the arguments, Chief Justice Chase deferred decision: Because the Senate had yet to be constituted as a “court” for the purposes of the trial, any determination about Wade was premature. The Senate voted narrowly, 24–20, to support Chase’s punt, and Wade took the oath the following day, March 6, with no guarantee that he would remain on the case.

Following the completion of the oaths, the House managers and Johnson’s four defense attorneys made their first appearance. The latter included Benjamin Curtis, a former justice of the Supreme Court who wrote a dissenting opinion in the infamous Dred Scott case and resigned from the Court (partly in protest) shortly thereafter. Curtis, defending a president accused of obstructing the push for racial equality, had strong credentials as a supporter of civil rights.

The defense demanded that they be given an additional 40 days to answer the impeachment charges. “Forty days!” thundered Benjamin Butler, an avowed enemy of the president. “As long as it took God to destroy the world by a flood!”6 The Senate deliberated over the request in private for two hours before deciding to grant the defense 10 days.

No one was overjoyed with the compromise, and tempers flared. The defense attorneys objected to the Senate’s “railroad speed” in conducting the trial, a charge that resonated in those early days of rail travel. But not everyone thought the pace too fast. Future president James Garfield, then a member of the House, later bemoaned that the trial was hostage to “the insane love of speaking among public men” and that the proceedings sank in a marsh of endless “words, words, words.”7

Andrew Johnson’s formal response to the charges came on its due date, March 23, and set forth a detailed description of the president’s actions, the legal authority behind them, and his motives. The next day, the House managers offered a boilerplate one-paragraph written reply. They expressed their objections more passionately in statements on the Senate floor. Butler declared that “the President is as guilty of malfeasance and misdemeanor in office as ever man was guilty of malfeasance or misdemeanor in office since nations began to be upon the earth.”8 He took particular issue with Johnson’s claim that he could disregard the Tenure of Office Act because it violated the Constitution. The president was claiming “power thus to lay hands upon the Constitution of the country and rend it in tatters.”9

The senators also took up the issue of timing again. Johnson’s team had requested another thirty-day continuance. After some angry back-and-forth, the Senate compromised on a six-day continuance.

The trial began in earnest at 1:00 p.m. on March 30, before a full gallery that included the British novelist Anthony Trollope. Butler made the opening statement for the managers. The very fact that he was selected to do so reflected the Republicans’ mood. A charismatic, controversial Union general, Butler gained notoriety during the military occupation of New Orleans. His heavy-handed administration of the city included seizing a 38-piece set of silverware from a woman attempting to cross Union lines illegally, earning him the sobriquet “Spoons.” Benjamin “Spoons” Butler was among the most outspoken and militant opponents of Andrew Johnson. He apparently adhered to the batty view that Johnson had acted in concert with John Wilkes Booth and others to assassinate President Lincoln.

Reading his three-hour opening statement, Butler emphasized that an actual crime is not necessary for conviction by the Senate. He instructed senators that they were “a law unto yourselves, bound only by the natural principles of equity and justice.”10 He defended Senator Wade’s participation in the trial, the issue deferred by Chief Justice Chase and still unresolved.* Butler argued that the Senate is not a court, and therefore judicial rules such as those regarding conflict of interest have no place.

After addressing various legal and factual issues surrounding Johnson’s alleged violation of the Tenure of Office Act, Butler finally got around to the article of impeachment that was his personal baby—Article 10, based on Johnson’s inflammatory speeches. But that charge may have rung hollow coming from Butler, whose own rhetorical excesses were on display toward the end of his diatribe: “This man by murder most foul succeeded to the presidency, and is the elect of an assassin to that high office, and not of the people.”11 Butler closed even more melodramatically: “The future political welfare and liberties of all men hang trembling on the decision of the hour.”12

The managers’ presentation of evidence, consisting of both documents and live witnesses, lasted six days, though one full day was consumed by the question of the chief justice’s authority to rule on disputes over evidence. After Chase made a ruling on challenged testimony, the House managers protested that he had no power to make such determinations. They preferred that disputes be resolved by the Senate, where Republicans enjoyed a comfortable majority. However, after much debate the Senate elected not to disqualify Chase from such rulings.

Most of the managers’ case involved setting forth the factual record surrounding the Tenure of Office Act and Johnson’s dismissal of Stanton, though they also called to testify several reporters who had witnessed the inflammatory speeches that gave rise to Article 10 of the articles of impeachment. During cross-examination of these reporters, Johnson’s attorneys elicited that the president appeared sober during these speeches, undermining Republicans’ efforts to present him as a lush.

The managers reserved for the end a clever touch, introducing into evidence two lists: a long list of all cabinet heads ever appointed by presidents and a shorter list of all such cabinet heads whom presidents discharged. The latter included a single name—Timothy Pickering, whom John Adams dismissed as secretary of state in 1800. For good measure, the managers introduced into evidence the correspondence of Adams and Pickering that demonstrated Pickering’s blatant insubordination. Thus the only cabinet dismissal prior to Johnson’s firing of Stanton took place under extreme circumstances. The managers suggested that, even apart from violating the Tenure of Office Act, Johnson’s dismissal of a cabinet secretary was un-American.

The defense requested, and over strong objections was granted, a five-day adjournment. They began their case on Thursday, April 9, with Ben Curtis’s opening statement. Unlike his counterpart Butler, a fellow Massachusetts attorney, Curtis spoke without notes. He advanced three related claims: 1) Stanton was not covered by the Tenure of Office Act;* 2) any misconduct by the president was unintentional, since he genuinely believed that Stanton was not covered by the Act; 3) if Stanton was covered, the Act was unconstitutional, and Johnson was right not to abide by it.

Curtis also went after Butler’s claim that the Senate was a law unto itself, free to convict a president even if he violated no laws. If that were so, Curtis argued, then U.S. citizens’ constitutional protections against ex post facto laws (laws punishing behavior that was legal at the time committed) and bills of attainder (laws singling out people for punishment without trial) somehow did not apply to presidents. And he assailed Article 10, which based impeachment on Johnson’s speeches, as an obvious affront to freedom of speech.

Next came the parade of defense witnesses, who mostly set forth their versions of how Johnson acted in response to the Tenure of Office Act, with an emphasis on his good motives. The managers’ frequent objections to the admissibility of this line of testimony created lengthy disputes that prompted Republican senator Charles Sumner to make a radical suggestion: Thenceforth all questions that were not obviously irrelevant should be permitted. Sumner’s motion cut against his own side, but he had grown impatient because he regarded Johnson’s guilt as a foregone conclusion. Who needed all the legal wrangling? But Sumner’s proposal to facilitate the trial was defeated.

An adjournment was granted during the defense case when one of Johnson’s counsel took ill, prompting Butler to fume that, while the trial dragged on, “Our fellow citizens are being murdered day by day. There is not a man here who does not know that the moment justice is done on this great criminal, these murders will cease.”13 Butler laid the blame for racist lynchings perpetrated by the Ku Klux Klan (formed just three years earlier) at the doorstep of the Oval Office.

When the trial resumed, the defense called a potentially crucial witness, Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles. Welles planned to testify that the cabinet had advised Johnson that the Tenure of Office Act was unconstitutional, supporting the notion that Johnson’s noncompliance with the Act was in good faith. The managers objected that such testimony was irrelevant. The two sides strenuously argued the point, and Chief Justice Chase ruled the testimony admissible because it went to the president’s intent. However, by 29–20 vote, the Senate reversed the ruling, thus gutting a major defense claim.

The Senate also reversed Chase’s ruling allowing Welles to testify that Johnson had been advised by his cabinet that Stanton was not covered by the Tenure of Office Act. As a result of the two rulings, Welles stepped down and the defense didn’t bother calling the secretaries of state, treasury, and interior, all of whom were expected to corroborate Welles’s testimony.

The defense case concluded on April 20. Though 41 witnesses had testified for the two sides (25 for the prosecution, 16 for the defense), no significant factual disputes emerged. What separated the sides were legal technicalities and one overarching question: Assuming President Johnson lacked the authority to fire and replace Secretary Stanton, did those wrongful acts rise to the level of high crimes and misdemeanors justifying his removal from office?

The closing arguments by the two sides commenced on April 22 and did not conclude until May 4. Much of the arguments by the eight counsel—four for each side—revolved around the legal and constitutional nuances surrounding the Tenure of Office Act, presented in every conceivable light. Even if all these questions were to be resolved in favor of the managers, however, the propriety of conviction did not necessarily follow. Indeed, the managers knew they were on shaky ground in claiming that any particular actions by Johnson amounted to impeachable offenses. They at times subtly and at times not so subtly changed the indictment to something more global: Andrew Johnson was a power-hungry monster.

House manager George Boutwell, an abolitionist from Massachusetts who would become secretary of the treasury in President Grant’s administration, claimed Johnson pursued his enemies “with all the violence of his personal hatred.”14 Boutwell also portrayed Johnson as a white supremacist who planned to keep blacks in chains. The president’s resistance to Reconstruction amounted to a criminal scheme to subvert the government and disgraced America in the eyes of civilized nations. Boutwell also tethered his broadsides against Johnson to Article 10 of the articles of impeachment. Johnson’s incendiary speeches showed him to be unfit for the office.

The defense felt compelled to defend the president not only against the articles of impeachment, but also as president and person. Johnson’s attorney and close personal friend, Thomas A.R. Nelson, reminded everyone of his client’s opposition to secession and lamented that one who imperiled himself to fight treason was now stigmatized as a traitor himself. Johnson’s opposition to the Republicans’ aggressive Reconstruction plan stemmed from his desire to heal a wounded country. Nelson added ruefully that “if he erred in this, it was almost a divine error.”15

It seemed impossible that Boutwell and Nelson were describing the same person. The man Boutwell depicted as a hateful would-be tyrant was, according to Nelson, a man of unsurpassed integrity and only the purest motives.

Defense counsel William Groesbeck, who had served as a law clerk for Chief Justice Chase, echoed the notion that if Johnson went wrong with respect to Reconstruction, it was from his yearning for national reconciliation and his absence of malice toward the South. Groesbeck was followed by manager Thaddeus Stevens. The great abolitionist was so infirm that partway through his statement he gave his draft to Butler to read out loud. Butler must have enjoyed the task, as Stevens’s speech contained outlandish rhetoric to rival his own. Though never quite charging that Johnson conspired with John Wilkes Booth, Stevens linked the two men. Johnson was an “offspring of assassination” who could not escape the “just vengeance of the law.”16

Thomas Williams, a congressman from Pennsylvania, went even further than his fellow managers in impugning the president’s integrity. He was the only manager to cast aspersions on Johnson’s opposition to secession, suggesting that it was undertaken solely from political opportunism. He opined that if Johnson were acquitted, no president would ever be impeached, no matter how egregious his misconduct.

Before the next attorney could take his turn, Butler rose to attack defense counsel Nelson for raising an argument that Butler considered irrelevant and offensive. Nelson responded, “So far as any concern that the gentleman desires to make of a personal character with me is concerned, this is not the place to make it. Let him make it elsewhere, if he desires to do it.”17 This challenge prompted Sumner to call for formal condemnation of Nelson for trying to provoke a duel. Nelson replied that while “not a duelist by profession,” he would not back down if challenged.18 (Incredibly, dueling was still accepted in parts of the United States in the 1860s, including Nelson’s home state of Tennessee.) The Senate rejected Sumner’s proposed censure of Nelson by a vote of 35–10.

Next came the closing argument of defense counsel William Evarts, a brilliant attorney destined to become Johnson’s attorney general after the trial and secretary of state under President Rutherford B. Hayes. Evarts spoke eloquently, and spoke and spoke and spoke—for almost four days. He belabored all the technical legal points, but also emphasized the extraordinary nature of impeachment and the need to heed the views of the American people concerning its usage. Evarts characterized impeachment as “this power which has lain in the Constitution like a sword in its sheath.”19 Now that it was drawn, ordinary folks wished to know what crime the president stood accused of. Evarts proceeded to riff on the public’s “wish to know,” caricaturing the impeachers in the process:

[The People] wish to know whether the President has betrayed our liberties or our possessions to a foreign state. They wish to know whether he has delivered up a fortress or surrendered a fleet. They wish to know whether he has made merchandise of the public trust and turned authority to private gain. And when informed that none of these things are charged, imputed, or even declaimed about, they yet seek further information and are told that he has removed a member of his cabinet.20

Evarts proceeded to tutor his audience in realpolitik. The president’s problems stemmed from 1) having attained office through an assassin’s bullets rather than the people’s ballots, and 2) the opposition party dominating Congress. Johnson was impeached solely because of those circumstances and not because he did anything remotely warranting that drastic remedy. Not wishing to waste an opportunity, Republicans contrived “to make out a crime, a fault, a danger that should enlist the terrible machinery of impeachment and condemnation.”21 Put differently, Republicans impeached Johnson simply because they could. Near the end of his exhaustive oration, Evarts succinctly summarized the situation: “It is all political. All these thunder clouds are political.”22

Next up was Henry Stanbery, Johnson’s attorney general until he stepped down to join Johnson’s defense team at the trial. (His reward would be a nomination by Johnson to the U.S. Supreme Court; his punishment, the Senate’s refusal to confirm him.) Stanbery, like co-counsel Nelson and Groesback, vouched for the president’s character, suggesting that in this regard Johnson was the equal of George Washington.

The final closing statement, by manager John Bingham of Ohio, was much anticipated because of Bingham’s exalted reputation as an orator. (He would later earn acclaim as a driving force behind the 14th Amendment.) With little left to be said, however, Bingham repeated and summarized the arguments of his colleagues. He did close with a stirring peroration, pleading on behalf of “the violated majesty of the law, by the graves of a half-million of martyred hero-patriots who made death beautiful by the sacrifice of themselves for their country, the Constitution and the laws, and who, by their sublime example, have taught us that all must obey the law; that none are above the law, that no man lives for himself alone, but each for all.”23 Though perhaps more poetic than logical, his words were met with a prolonged standing ovation.

The managers’ case suffered serious flaws. While most of the articles of impeachment stemmed from Johnson’s discharge of Stanton, several specifically involved his replacement of Stanton with an interim director. Statutes dating back to 1792 authorized the president to make such interim appointments, and the question as to whether a later statute effectively repealed those statutes seemed highly technical. As noted, a second technical question concerned whether the Tenure of Office Act even applied to Stanton.

An overriding question presented itself with respect to these legal disputes: Could disagreement about nuanced legal matters possibly be the basis for conviction and removal of a president? To the extent that the debate on the Senate floor resembled a panel of law professors offering competing interpretations of a statute, by its very nature it did not concern an impeachable offense. Johnson was at most wrong, but not so heinously wrong as to justify the political death penalty.

That perspective also applied to the dispute at the heart of the controversy: the constitutionality of the Tenure of Office Act. Johnson took the plausible position that, insofar as it prevented presidents from discharging their cabinet members without the Senate’s consent, the Act violated the Constitution. Subsequent history validates this position. Congress repealed the Tenure of Office Act in 1887, and the Supreme Court deemed a similar law unconstitutional in 1926.

As a matter of policy, the idea of forcing a president to live with cabinet members he considers insubordinate or incompetent is problematic. In any event, a president must interpret the Constitution as he or she thinks proper. If the president and Congress clash over different interpretations, the solution is to turn to the third branch—the courts, the ultimate interpreters of the Constitution. Had the Supreme Court held that Johnson could not fire Stanton, and had he disobeyed their decision, then and only then would there be grounds for impeachment.

The managers rejected that position, starting with Butler’s opening statement. He acknowledged the indisputable fact that a president may disagree with Congress about the constitutionality of a law. The president’s remedy, though, is to veto the bill. Once a veto is overridden, he must execute the law. He refuses to do so, said Butler, “at his peril [and] that peril is impeachment.”24

Why shouldn’t Johnson instead refuse to abide by the law and allow the courts to resolve the issue? Butler had no good answer, but he did have a fallback position: Even if that were a legitimate course of action, Johnson had not undertaken it. He had done nothing to submit the constitutionality of the Tenure of Office Act to the courts.

The managers were on shaky ground here. For one thing, Johnson had in fact wanted the Supreme Court to resolve the matter and had hoped that would occur when Stanton had Thomas arrested for accepting the appointment as his replacement. Thomas testified that, when he informed Johnson of his arrest, the president expressed satisfaction because he wanted the matter resolved by the courts. It was the Republicans, not Johnson, who saw to it that charges against Thomas were dropped so the constitutionality of the Act would not be adjudicated. Besides, why was Johnson obliged to take the matter to court? Why not act as he thought appropriate and let the aggrieved party (in this case Stanton or a member of Congress) bring suit to challenge him? That was and is the normal course.

Once again, even if one saw that matter differently—if one felt that the president must enforce the law until the courts rule in his favor—this was a debatable matter that separated constitutional lawyers of good faith. Error on such a matter could not justify impeachment.

The two articles of impeachment based on speeches by Johnson ran into a different difficulty. No official transcripts of those speeches existed, and there were conflicting accounts of just what Johnson had said. But quite apart from that, to base impeachment on speeches, even if they were considered outrageous or erroneous, violated the spirit if not letter of the First Amendment.

If the arguments favored acquittal, arithmetic favored conviction: 42 of the 54 senators were Republicans, so a party-line vote in this partisan atmosphere would doom the president. The run-up to the day of decision witnessed the sort of politicking that takes place before any important congressional vote: meetings, negotiations, deals, arm-twisting among the senators and party leaders, as well as senators hearing from their constituents. President Johnson, for his part, let the Republicans know his intention to reward an acquittal by appointing a new secretary of war to their liking.

On May 11, the Senate deliberated behind closed doors for 15 hours, recessing only for dinner. Before debating whether to convict and remove President Johnson, they took up a series of procedural questions. One interesting issue illustrates how the Constitution leaves open the conduct of the impeachment trial. The Constitution specifies that conviction brings mandatory removal from office, and sets forth an optional additional punishment: disqualification from future office. If Johnson were convicted and removed, could he run in the forthcoming presidential election (or for any office thereafter)? The Senate would have to decide, but by what margin? The Constitution says two-thirds is required for conviction, but is silent about the vote needed to impose the additional punishment of future disqualification. A good argument could be made for either two-thirds or a mere majority. The senators debated this issue but failed to resolve it. They would have to take it up again if and when the president was convicted.

This and other issues, and the merits of the 11 articles of impeachment, kept the senators busy until midnight. A final vote on the articles was deferred until May 16. On that fateful day, more than 1,500 spectators crammed in to a Senate gallery that comfortably accommodated one thousand. Those present would uniformly report electricity in the air. People understood that they were about to witness something unprecedented and history-making.

At noon, Chief Justice Chase gaveled the proceedings to begin. Senator George Williams from Oregon, one of the most pro-conviction members, proposed that Article 11 (the omnibus article believed to command the most support) be voted on first, and the senators agreed. One by one each of the 54 senators was called, rose, and announced his vote. (Two were so infirm that Chase gave them permission to remain seated, but they rose nevertheless.) Thirty-five voted to convict and 19 to acquit—one vote short of the two-thirds required for conviction.

Williams again sprang up, this time to ask for a 15-minute recess, presumably to allow the pro-conviction forces to regroup. When this unorthodox proposal received no support, he moved for a 10-day adjournment. Chase overruled the motion but the Senate, by vote of 32–21, reversed the ruling.

During that ten-day break, anti-Johnson forces both inside and outside the Senate desperately sought to pressure the seven Republicans who had voted to acquit. The Republican Party’s national convention met to nominate a presidential candidate and, in addition to nominating Ulysses S. Grant, expressed its support for the conviction of President Johnson. The party platform declared Johnson guilty of high crimes and misdemeanors. The Republican senators who days earlier voted to acquit on Article 11 were (in absentia) alternately vilified and beseeched to vote differently on the outstanding articles.

The outcome remained uncertain when the Senate reassembled as an impeachment court on May 26. The senators discussed and rejected a notion to adjourn for another month. It was then moved and approved to skip Article 1, which had little chance, and vote on Articles 2 and 3, which, dealing with the replacement of Edwin Stanton rather than his discharge, supposedly had more support. This presumed, oddly, that some senators thought Johnson had the power to fire Stanton but not to designate a replacement. As it happens, all 54 senators voted the same way on Article 2 as they had on Article 11. Once again, Johnson escaped conviction by a single vote.

The vote on Article 3 produced déjà vu all over again—the same 35 to convict and 19 to acquit. At this point the defeated anti-Johnson forces adopted an exit strategy: declare victory and go home. Charles Sumner proclaimed that despite the nominal acquittal, the Senate had delivered a profound moral judgment against Johnson. By a vote of 34–16, the Senate disbanded the trial without voting on the remaining eight articles.

Later that day, Stanton notified Johnson by letter that he would abandon his office. Other opponents of the president were slower to accept defeat. Congress immediately launched an investigation into reports that some of the Republican votes to acquit were secured by bribes. Thaddeus Stevens, clinging to life, immediately drafted new articles of impeachment. None of these efforts bore fruit, although Stevens shared his proposed articles in his valedictory speech on the Senate floor on July 7. The lifelong devotee of racial justice also proclaimed that the nation would not be truly blessed until everyone accepted that all human beings enjoy the same inalienable rights.

The seven Republicans who voted to acquit Johnson earned the title “Seven Tall Men” but paid a price for their courage: None was reelected to the Senate. One of them, Edmund Ross, appeared to support conviction but changed his mind late in the process. Ross later wrote that as he cast his vote, “I almost literally looked down into my open grave.”25 He received posthumous glory, meriting a chapter in John F. Kennedy’s book Profiles in Courage, which called his vote the most heroic act in U.S. history. Alas, some evidence suggests that Ross received a bribe from pro-Johnson forces.

Andrew Johnson served out the remaining nine months of his term as a man without a party. He had abandoned the Democrats to join Lincoln’s ticket, yet never became a Republican and alienated Republicans by opposing Reconstruction. He did not actively seek reelection as president, though he did receive substantial support on the first ballot at the Democrats’ nominating convention in New York in July, just two months after he survived the Republicans’ effort to remove him from office.

In a letter to a friend one month later, Johnson showed impressive grace. That he called Lincoln the greatest American who ever lived is not shocking—he always praised his political benefactor. But he also forgave some of his enemies, notably Benjamin Butler. Though Johnson had harsh words for the man who led the charge to remove him, he said Butler’s impressive military service for the Union mitigated his sins. Johnson’s magnanimousness had limits. “I shall go to my grave with the firm belief that [Jefferson] Davis . . . should have been tried, convicted, and hanged for treason.”26 A few months later, he pardoned Davis and other Confederate leaders. Johnson was an elusive character to the end.

He left the White House quietly, but never tired of trying to return to public life. After several electoral defeats in Tennessee, in 1875 he was elected United States senator from the Volunteer State. He became colleagues with 13 of the men who had voted to convict him seven years earlier. Three months after he was sworn in for his new job, Johnson suffered a stroke and passed away the following day.

Most historians regard the Johnson impeachment as a partisan witch-hunt, but the reality is more complex. The further the event recedes in time, the more it becomes divorced from its historical context. If viewed solely as a question of whether Johnson’s defiance of the Tenure of Office Act constituted an impeachable offense, the case is a slam dunk in Johnson’s favor. But viewing the case that way would be like seeing the Dred Scott decision as turning on a technical question of jurisdiction, or Brown v. Board of Education as turning on the quality of the facilities in segregated schools. In other words, it ignores the history of racial oppression.

Out of context, Andrew Johnson’s alleged wrongdoing seems technical and the impeachment episode simply a political tug-of-war. But that wasn’t how the anti-Johnson forces viewed it. Consider these excerpts from Senator Sumner’s opinion favoring Johnson’s conviction: “This is one of the last great battles with slavery. . . . [D]riven from the field of war, this monstrous power has found a refuge in the Executive Mansion.”27 Sumner referred to Johnson as “the patron of rebels,” and claimed that his refusal to break from slavery was “the transcendent crime of Andrew Johnson.”28

These characterizations may have been hyperbolic, but Johnson provided fodder for them. He said in one speech that if blacks and whites could not get along, blacks would have to be colonized; he openly flirted with white supremacy and refused to criticize publicly the Black Codes that legally enforced an apartheid regime.

Imagine, as a thought experiment, if the House’s articles of impeachment tracked Sumner’s critique rather than relying on Johnson’s discharge of Stanton. Suppose the House lumped together his many acts of opposition to Reconstruction into the following charge: “Through his obstruction of efforts to eliminate the vestiges of slavery, including measures providing blacks equal protection of the laws and the right of suffrage, the president has abetted a moral atrocity and thwarted the purpose for which 360,000 Union soldiers and President Lincoln gave their lives. He has thus demonstrated his unfitness for office at this crucial historical moment.”

Though the outcome would likely have been the same, such an article would probably be looked on with more favor today than the articles actually adopted by the House. When we focus on Johnson’s refusal to abolish the remnants of white racial domination and enslavement of black people, we can understand why his opponents felt compelled to remove him. They felt especially justified because Johnson was not elected into the Oval Office. On the great moral issue of the day, progress was blocked and evil enabled by an accidental president. Johnson’s removal would not have undone the will of the people expressed at the ballot box. Indeed, it would have removed someone who arguably threatened the legacy of the man the American people had put in the White House.

To be fair, Johnson’s views of Reconstruction were similar to Lincoln’s, and the Radical Republicans had once toyed with the idea of impeaching Lincoln. Still, to say Republicans used impeachment as a political tool is to oversimplify. Slavery was not a routine political issue akin to fights over health care or taxes. Such issues, while important, lack the nation-defining moral clarity of racial justice, particularly in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War. Andrew Johnson’s supporters insisted that he was not anti-black but rather favored a path to progress that was less punitive toward the South. But Republicans judged in good faith, and correctly, that Johnson was on the wrong side of history and morality.

It does not follow that Johnson’s impeachment adhered to the letter and spirit of the Constitution. It did not, for reasons we will discuss in more detail in chapter six. For present purposes, a few things deserve mention. First, Andrew Johnson’s term as president was winding down. Had Congress avoided the last resort of impeachment, he would have finished his term and stepped aside or else faced the voters. That much we know. It is an educated guess that had Johnson been convicted and removed, impeachment would have been resorted to far more readily thereafter—in the short term as revenge by Democrats, in the long term because of the historical precedent.

Even the failed effort to remove Johnson may have been costly. Many historians claim that it is no coincidence that few people today can name the half-dozen presidents to follow Andrew Johnson, believing that Johnson’s impeachment and near-conviction weakened the presidency.

Perhaps the final word should be left to a Republican who resisted his party’s push to remove the opposition president. Senator Lyman Trumbull, an Illinois Republican, close friend of Lincoln, and coauthor of the 13th Amendment, was one of the seven Republicans who voted to acquit Johnson. Trumbull explained that if Johnson were convicted, “no future president will be safe who happens to differ with a majority of the House and two-thirds of the Senate on any measure deemed by them important. . . . And what then becomes of the checks and balances of the Constitution, so carefully devised and so vital?”29

* Wade abstained from voting throughout the trial, until a key motion right before the actual vote to acquit or convict. He voted on that motion and on the articles of impeachment themselves. Perhaps because the outcome did not end up turning on his vote, no one renewed the objection to his participation.

* The technical question whether the Act applied to Stanton consumed a fair amount of the trial. The Act stated that it protected cabinet members from discharge “during the term of the president by whom they may have been appointed and one more thereafter.” The key term was . . . “term.” Had Lincoln’s term expired with his death? Or did it continue until its natural expiration in 1869?