THREE

DOWN GOES NIXON

It is tempting to say that Andrew Johnson’s impeachment stemmed from his political vulnerability whereas Richard Nixon’s imminent impeachment—averted only by his resignation—occurred because of his political strength. On this reading, the hubris caused by Nixon’s 49-state landslide reelection in 1972 led him to regard himself as above the law and to abuse the prerogatives of his office. That view, however, neglects a crucial fact: The incident that set in motion the chain of events leading to Nixon’s downfall occurred six months before the 1972 election, and reflected his campaign’s sense of insecurity rather than invulnerability.

On June 17, 1972, District of Columbia police caught five men who had broken into the Democratic National Committee headquarters at the Watergate Hotel. The men, who wore surgical gloves and carried walkie-talkies and photographic equipment, apparently planned to bug the offices. Nixon’s response to that failed intrusion, more than any other malfeasance, triggered his resignation two years later.

President Richard M. Nixon

On June 19, two days after the break-in, a pair of young Washington Post reporters broke the news that the burglars included former CIA agent James McCord, who served as security consultant to the Committee to Reelect the President (“CREEP”). Before long, it became clear that some of Nixon’s aides actively and illegally sought to cover up the campaign’s role in the break-in. A central question became whether the cover-up involved the nation’s 37th president himself.

Nixon’s press secretary, Ron Ziegler, downplayed the Watergate break-in as a “third-rate burglary.” If Ziegler had been referring to the ineffectiveness of the operation, he would have had a point: The burglars botched the job. But his efforts to trivialize the break-in amounted to futile spin. A felonious burglary designed to perpetrate covert surveillance of an adversary political party is serious business. McCord and his fellow burglars were convicted of numerous criminal charges.

Far more serious, though, was the cover-up, if only because it ended up implicating the president. But despite the fact that Democrats controlled both houses of Congress, there was reluctance to pursue impeachment even as evidence of the cover-up emerged. This stemmed in part from the absence of precedent. Only 13 impeachment cases in United States history had reached a verdict in the Senate—mostly judges, along with one United States senator, one cabinet official, and President Andrew Johnson—yielding only four convictions, all of judges. Most of these cases involved corruption or drunkenness, circumstances bearing no similarity to the Watergate crimes. Moreover, the most recent impeachment had been in 1936, nearly four decades earlier. For all these reasons, these precedents were almost irrelevant.

The single example of a presidential impeachment counseled caution. Most historians and political scientists considered the impeachment of Andrew Johnson an unseemly, politically-motivated spectacle. That helps explain why no presidents thereafter were impeached, notwithstanding actions (such as the Teapot Dome Scandal during the Harding administration) that, under different circumstances, might have inspired loud calls for impeachment.

Thus, the Andrew Johnson ordeal could be seen as a case study counseling against impeachment. However, this century-old precedent provided limited guidance. Johnson was almost convicted, and senators who voted to acquit might have done so for any number of reasons. They may have believed that Johnson did nothing wrong, as he acted on a correct interpretation of the Tenure of Office Act and/or its unconstitutionality. Alternatively, they may have felt that he acted improperly but that the error did not rise to the level of a high crime or misdemeanor. Or they may have believed that he committed an impeachable offense but concluded that it was unnecessary and unwise to remove him when his term would expire shortly. The Johnson impeachment presented only a single, long-ago case that yielded no clear, agreed-upon narrative.*

The House did not set in motion an impeachment process against Nixon until February 1974, by which time extensive evidence had already been gathered from three independent investigations: 1) the trial of the Watergate burglars before Judge John Sirica in federal court in the District of Columbia, as well as grand jury investigations flowing from that trial; 2) the Senate’s Watergate Committee (more formally the “Select Committee on Presidential Campaign Activities”), chaired by folksy North Carolina Democrat Sam Ervin; and 3) the office of Special Prosecutor Archibald Cox and his successor, Leon Jaworski. In addition, reporting in several newspapers, especiallyby the Washington Post’s Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, provided information used by the various investigators.

The evidence of White House wrongdoing uncovered by these investigations included some that predated the break-in at the Watergate Hotel. Most notably, back in September of 1971, the White House “plumbers” unit—so-called because of their mission to plug leaks in the administration—burglarized the office of a psychiatrist, Dr. Lewis Fielding, looking for material to discredit his patient, Daniel Ellsberg, the former defense analyst who leaked the Pentagon Papers. (The bungled break-in, and other government misconduct, led to dismissal of criminal charges against Ellsberg.)

Fairly early discoveries related to Watergate included the involvement of White House operatives Gordon Liddy and E. Howard Hunt in planning the break-in; the fact that CREEP, run by Nixon’s former attorney general John Mitchell, controlled a secret fund (obtained in violation of campaign finance laws) that financed intelligence gathering and covert operations against Democrats; and the involvement in the Watergate cover-up of Nixon’s top White House staffers, H.R. Haldeman and John Ehrlichman, and White House counsel John Dean, all of whom resigned as a result on April 30, 1973. In accepting their resignations, Nixon called Haldeman and Ehrlichman “two of the finest public servants it has been my privilege to know.”1 He said nothing about Dean, who was allegedly cooperating with prosecutors.

That trio of resignations accelerated inquiries into President Nixon’s possible involvement in the cover-up. On May 1, the Senate by voice vote (albeit with only five senators present) asked Nixon to appoint a special prosecutor to investigate Watergate. On May 18, attorney general-designate Eliot Richardson appointed as special prosecutor Archibald Cox, a Harvard Law School professor and former solicitor general during the Kennedy and Johnson administrations.

One day earlier, Sam Ervin’s Senate Select Committee, which had been established by vote of 77–0 in February, began holding hearings, televised on a rotating basis by ABC, CBS, and NBC until near the end of September. Public hearings continued through mid-November, the last few weeks covered only by public television. In all, the committee held 53 days of public hearings and heard testimony from 63 witnesses.

None was more important than John Dean, who testified under a grant of immunity from the committee after resigning from his White House position seven weeks earlier. (He could still could have been—and was—prosecuted in court; the immunity meant that his testimony before the committee could not be used against him at his trial.) For five days beginning June 25, 1973, Dean gave explosive testimony that propelled the investigation. The first day consisted of Dean reading a 246-page statement, prepared at the request of his attorneys, which outlined everything he knew pertaining to the Watergate break-in, the cover-up, and other wrongdoings involving the White House. The next four days, he relied on his prodigious memory in responding to questioning from the committee.

Dean claimed that the White House pressured the Watergate burglars to plead guilty and remain silent and that Nixon personally authorized “hush money” for that purpose. He asserted that he and Nixon discussed the Watergate cover-up on at least 35 occasions, going back to September 15, 1972, just a few months after the break-in (and not coincidentally the day a grand jury indicted the seven men responsible) and long before Nixon acknowledged even knowing there was a cover-up. Nixon actively participated in those discussions. He repeatedly counseled his underlings to “stonewall” investigators and essentially claim amnesia before a grand jury.

Dean also submitted to the committee a memorandum he authored and distributed to White House staff back in August 1971, stating the unofficial White House policy to explore “how we can use the available federal machinery to screw our political enemies.”2 Closely related, he disclosed that the White House urged the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) to conduct punitive tax audits against people on a long “enemies list” compiled by the White House.

Dean would be a particularly difficult witness to discredit, because he readily confessed to his own extensive involvement in illegal activities. Even so, Nixon’s categorical denial of most of Dean’s accusations created a potentially unresolvable he said/he said (not helped by Nixon’s refusal to appear before the committee). That changed dramatically, however, on July 16, just a few weeks after Dean’s testimony.

Herbert Kalmbach, formerly Nixon’s personal attorney, testified that Dean and John Ehrlichman appealed to him to raise money for the Watergate defendants and their families. Kalmbach explained that he raised $220,000—money he came to realize was designed to buy the defendants’ silence—and gave it to Anthony Ulasewicz, an “investigator” with White House connections, to deliver. (A few days later, Ulasewicz told the committee how he distributed large sums of cash in paper bags that he dropped off in lockers and telephone booths.)

Incredibly, Kalbmach’s testimony, which corroborated Dean’s and confirmed a criminal cover-up at the highest levels, barely made the news. It was overshadowed by testimony the same day from Alexander Butterfield, a retired air force officer who served as Nixon’s appointments secretary from 1969 to 1973 before becoming administrator of the Federal Aviation Administration. Butterfield informed the Ervin Committee about taping devices that, in the spring of 1971, Nixon had installed in several rooms: the Oval Office, his office in the Executive Office Building, and the White House’s cabinet room. These devices presumably recorded many of the president’s conversations.

The superstitious may note that Butterfield first revealed the taping system in a private meeting with committee staff a few days earlier—on Friday, July 13. Dean had testified that he suspected conversations in the White House were recorded. Now a staff member asked Butterfield if there was any basis for Dean’s suspicions. Butterfield replied, “I was hoping you fellows wouldn’t ask me that,”3 before making the stunning revelation.

Watergate special prosecutor Archibald Cox at a press conference, June 4, 1973. PHOTOGRAPH BY WARREN K. LEFFLER.

Immediately following Butterfield’s public testimony, the Ervin Committee and Special Prosecutor Cox requested select tapes, but Nixon declined to provide them, claiming executive privilege. Both Cox and the committee then subpoenaed the tapes, and Judge Sirica ordered Nixon to comply with Cox’s subpoena, a decision upheld by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit on October 12. Nixon still refused to comply, but proposed that Senator John Stennis, a Democrat from Mississippi and ally of the administration (not to mention notoriously hard of hearing), review and summarize the audio recordings for the special prosecutor’s office. He also demanded that Cox thereafter cease seeking more tapes. Cox naturally declined the “compromise” offer that would have forfeited his victory in court.

On October 20, Nixon ordered Attorney General Richardson to fire Cox. (Under an agreement between the White House and Senate, only the Justice Department had that authority.) Richardson refused and resigned, as did Deputy Attorney General William Ruckelshaus. Solicitor General Robert Bork, next in line at the Justice Department, gave Cox the bad news. At a press conference that evening, Ron Ziegler also announced Nixon’s intention to abolish the special prosecutor’s office entirely and return the Watergate investigation to the Justice Department.

Hundreds of thousands of phone calls and telegrams bombarded Washington in protest of the so-called Saturday Night Massacre, but few public officials called for Nixon’s resignation, in part because the vice presidency was at that moment vacant. Less than two weeks earlier, for reasons unrelated to Watergate, instead stemming primarily from misconduct in his days as governor of Maryland, Vice President Spiro Agnew had resigned. The person next in line of succession to the presidency, Speaker of the House Carl Albert, was a Democrat, and Nixon would not have considered resigning under the circumstances. Nor would Republicans have wanted him to.

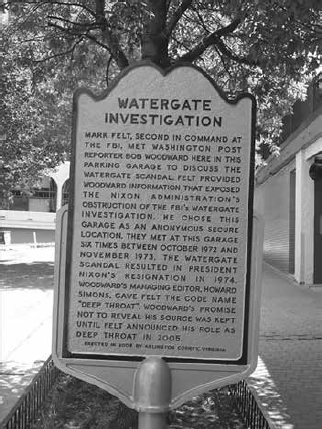

Watergate landmark sign in Arlington, Virginia.

Still, the Saturday Night Massacre seemed like a potential game-changer. To be sure, mention of impeachment had been bandied about six months earlier, following the April 30 resignations of Haldeman, Ehrlichman, and Dean, and an impeachment resolution had been introduced on July 31 by Father Robert Drinan, a Jesuit priest and leftist House member from Massachusetts. However, the resolution was largely ignored. After the firing of Cox, calls for impeachment became more frequent and were taken more seriously.

In the New Yorker, Elizabeth Drew quoted an anonymous Democratic House member as saying that the Saturday Night Massacre let “the genie out of the bottle. . . . What the President did over the weekend may not have been a high crime or misdemeanor, but it opened things up.”4 Indeed, within days of the Saturday Night Massacre, 57 senators introduced bills to establish a new special prosecutor. Nixon quickly backed down on his threat to abolish the office and announced that he would appoint a new special prosecutor to replace Cox.

On November 1, Acting Attorney General Bork appointed Leon Jaworski, a prominent Texas attorney who had been a prosecutor in the Nuremberg war trials, to succeed Cox.

Just two days earlier, on October 30, the House Judiciary Committee, consisting of 21 Democrats and 17 Republicans and chaired by New Jersey Democrat Peter Rodino, established an “impeachment inquiry” staff. The staff eventually included 43 lawyers, two of whom would later achieve political prominence: future Massachusetts governor William Weld and a recent Yale Law School graduate named Hillary Rodham. One of the congressmen on the committee, Iowa Democrat Ed Mezvinsky, would become father-in-law to Rodham’s daughter, Chelsea Clinton, 37 years later.

Nixon did turn over some of the subpoenaed tapes ordered by Sirica and affirmed by the Court of Appeals, but two conversations that seemed particularly important (one with John Mitchell three days after the break-in and one with John Dean that Dean testified was damning) were missing. This prompted more calls for impeachment. In early November, Edward Brooke of Massachusetts became the first Republican senator to call on Nixon to resign.

Nixon steadfastly refused such invitations, and at a press conference on November 17 made one of the more memorable utterances of the entire Watergate affair. “People have got to know whether or not their president is a crook. Well, I am not a crook.”5

Four days later, it was reported that one of the tapes the White House had turned over, involving a discussion between Nixon and Haldeman a few days after the break-in, contained 18.5 minutes in which nothing was audible. On November 26, Nixon’s secretary, Rose Mary Woods, explained the gap in testimony before Judge Sirica. She claimed that she inadvertently recorded over the Nixon-Haldeman conversation in the course of transcribing it. As her alleged blunder would have required a contorted body position (in which she stepped on the recorder’s foot pedal while reaching for the phone and somehow maintained that awkward position for a prolonged period), it became known as “the Rose Mary Stretch.”

The next day, the Senate confirmed Gerald Ford as vice president by a vote of 92–3, and 10 days later the House did so by a vote of 387–35, removing a major impediment to Nixon’s impeachment.*

As if Nixon didn’t have enough problems, his private financial situation attracted scrutiny during this period. It was revealed that he claimed a $570,000 income tax deduction for donating his vice presidential papers to the government and that the government paid for improvements on his private homes in Florida and California. Under pressure from public interest groups, on December 8 Nixon released his tax returns for 1969–72. They showed that he paid a combined total of $6,000 in income tax for 1970–72. (Though he often emphasized his humble beginnings and refusal to capitalize on his public service, Nixon had in fact become a millionaire by this time.) Months later, the IRS determined that he owed $476,000 in back taxes and interest.

House Judiciary Subcommittee questioning President Gerald Ford on pardoning former President Richard Nixon, October 17, 1974. PHOTOGRAPH BY THOMAS J. O’HALLORAN.

Meanwhile, on January 15, 1974, a six-member panel of electronics experts jointly selected by the White House and Special Prosecutor Jaworski’s office to study the missing 18.5 minutes of Haldeman-Nixon conversation reported its findings to Judge Sirica. The group unanimously concluded that the gap on the tape was caused by at least five deliberate erasures, debunking the “Rose Mary Woods Stretch” explanation.

On January 30, in his State of the Union address, President Nixon vowed to cooperate with the House impeachment inquiry “in any way I consider consistent with my responsibility to the office of the presidency,” while reiterating that he would withhold requested materials whose release would compromise the need for confidentiality in high-level conversations. He urged a speedy resolution of the investigation, remarking that “one year of Watergate is enough.” The next day Sam Ervin retorted that “one minute of Watergate was too much” and placed the blame for the delay on Nixon’s failure to cooperate.6

On February 6, by a vote of 410–4, the House formally authorized the Judiciary Committee to investigate the propriety of impeaching Nixon and empowered the committee to draft articles of impeachment if appropriate. It also gave the committee subpoena power.

Just two weeks later, the impeachment inquiry staff weighed in on the ongoing debate over the purpose and scope of impeachment, drafting a memorandum arguing that impeachment does not require criminal behavior but rather any conduct that involves “undermining the integrity of office, disregard of constitutional duties and oath of office, arrogation of power, abuse of the governmental process.”7 However, the memorandum acknowledged that impeachment is a grave step reserved for cases of serious misconduct that violate constitutional norms and duties.

On February 28, Nixon’s legal team, led by Boston attorney James St. Clair, submitted a written response to the committee. (This wasn’t St. Clair’s first brush with history. At the Joseph McCarthy hearings in 1954, he assisted Joseph Welch, who famously asked Senator McCarthy, “Have you no shame?”) He argued, as Nixon’s defenders would throughout the process, that an overly broad view of impeachment would destroy the fundamental principle of separation of powers. St. Clair insisted that a president could not be impeached unless he committed an indictable crime such as treason or bribery. At a press conference three days earlier, Nixon himself maintained that only a criminal offense justifies impeachment.

On March 1, the Watergate grand jury indicted Haldeman, Ehrlichman, and Mitchell for obstruction of justice related to the cover-up of the Watergate break-in. They also handed down indictments of Mitchell and Haldeman for perjury before the Ervin Committee and Mitchell and Ehrlichman for perjury before the grand jury itself.

Five days later, St. Clair announced that Nixon would cooperate fully with requests from the House Judiciary Committee for specific tapes and documents. He would also answer written questions from the committee and even sit down for interviews with members of the committee.

The next day, March 7, brought more bad news for the president’s (former) men: Ehrlichman, Charles Colson, and G. Gordon Liddy were indicted for their role in the burglary of the office of Dr. Lewis Fielding, Daniel Ellsberg’s psychiatrist, back in 1971.

On March 8, just two days after announcing Nixon’s plans for far-reaching cooperation with the Judiciary Committee, St. Clair declared a change of course: Nixon would turn over only materials he considered directly related to the Watergate break-in and cover-up, and planned to withhold some of the tapes and documents the committee had requested.

On April 4, Chairman Rodino opened a session of the Judiciary Committee by reading a statement concerning the White House’s noncompliance with requests for tapes and documents: “The patience of this committee is now wearing thin. . . . We can subpoena them if we must.”8 When the only response was a letter by St. Clair saying that a review of the requested material was under way and might take weeks to complete, the committee made good on its threat. On April 11, by a vote of 33–3, it subpoenaed 42 tapes of conversations involving Nixon. (One of the three “no” votes came from a 32-year-old Mississippi Republican, Trent Lott, who would become Senate minority leader decades later and thus a leading figure at the impeachment trial of Bill Clinton.)

One week later, another subpoena was served on Nixon, this one initiated by Special Prosecutor Jaworski and signed by Judge Sirica. It ordered President Nixon to turn over memoranda and tapes covering 64 conversations deemed potentially relevant to the forthcoming criminal trials of Haldeman, Ehrlichman, Mitchell, and four other defendants charged with Watergate-related crimes.

Nixon operative, G. Gordon Liddy

In a nationally televised address on April 29, Nixon pledged to give the House Judiciary Committee edited transcripts of the conversations in question, but warned that impeachment “would put the nation through a wrenching ordeal.” He remarked, apropos the 18.5-minute gap in a key tape, “How it was caused is still a mystery to me.”9

The next day the White House made public more than 1,200 pages of edited transcripts of the president’s conversations. (The editing included countless insertions of “Expletive Deleted.”) However, Nixon refused to turn over the actual tapes or to comply with the special prosecutor’s subpoena.

The transcripts included substantial damning material. On the day the Watergate burglars were indicted, Nixon praised John Dean for “very skilful[ly] putting your fingers in the leaks that have sprung here and sprung there,” which certainly sounded like reference to maintaining a cover-up. In another conversation, Dean said that buying the silence of the defendants would require one million dollars. Nixon replied, “We could get that. . . . You could get a million dollars. You could get it in cash. I know where it could be gotten.” And he later said about such a payoff, “It would seem to me that would be worthwhile.” In a different conversation, Nixon instructed Assistant Attorney General Henry Petersen, who was at the time investigating Watergate as head of the Justice Department’s criminal division, “You have got to maintain the presidency out of this.”

On May 1, Chairman Rodino sent a one-sentence letter to the president on behalf of the House Judiciary Committee advising him that he had failed to comply with the Committee’s subpoena of April 11. The following day Nixon responded that any further disclosures of White House conversations would be contrary to the public interest.

On May 7, St. Clair announced that no tapes or transcripts would be given to the special prosecutor and nothing additional to the House Judiciary Committee. Two days later, the committee began official impeachment hearings. As in all its prior work, the committee aimed for bipartisanship. The majority and minority had formed a single staff jointly appointed, and held most deliberations in private to reduce partisan pressures. Still, divisions emerged. In their sessions behind closed doors, Chairman Rodino and the committee’s chief counsel, John Doar, presented a pattern of misconduct and Democratic members voiced support for impeachment, but most Republicans held out. They echoed the White House view that only indictable offenses were impeachable and demanded greater specificity in the evidence against Nixon before presidential impeachment could be seriously contemplated.

In late July, the committee televised hearings—roughly 80 hours spanning six days. A recurring question during the hearings was one famously posed by Republican Senator Howard Baker during the hearings of the Ervin Committee (of which Baker was vice chairman): “What did the President know and when did he know it?” The more material that came out with respect to that question, and other White House improprieties, the more the sentiment swung toward impeachment, although during the summer there remained sharp partisan division in both Congress and the country at large.

On May 20, Judge Sirica issued a formal order requiring Nixon to turn over the tapes of the 64 conversations requested by Special Prosecutor Jaworski. The White House announced that it would defy the order and appeal all the way to the Supreme Court. The same day, Newsweek quoted Senator Barry Goldwater, the Republican presidential nominee in 1964, saying that the time had come for Nixon to think about stepping down.

Later in the month, the House Judiciary Committee sent the White House a strongly worded letter stating that it would have to consider whether the refusal to turn over materials might itself constitute a ground for impeachment. The vote to send the letter was 28–10, with eight Republicans going along. On June 6, the Los Angeles Times reported that back in March the federal grand jury that indicted Haldeman, Ehrlichman and others for their involvement in the Watergate cover-up had named Nixon as an unindicted co-conspirator.

On June 24, Charles Colson pleaded guilty and received the stiffest sentence to date for any of the Watergate defendants, one to three years in prison plus a $5000 fine, for obstruction of justice based on efforts to defame Daniel Ellsberg and influence the jury prior to Ellsberg’s trial. In a statement in the courtroom, Colson pointed a finger at the president, who, he said, “on numerous occasions urged me to disseminate damaging information about Ellsberg.”10

On June 27, the Ervin Committee released its 1,094-page report detailing the findings from its year-long investigation. The report made no explicit recommendations, but reasonable readers would see it as supporting Nixon’s impeachment, as Chairman Ervin all but admitted to a reporter: “You can draw the picture of a horse in two ways. You can draw a very good likeness of a horse, and say nothing. Or you can draw a picture of a horse, and write under it: ‘This is a horse.’ We just drew the picture.”11

The next day, St. Clair made his first appearance before the House Judiciary Committee, and maintained that Nixon did not learn about the Watergate cover-up until March of 1973 and never approved the payment of hush money to the defendants.

On July 8, in a special summer session to expedite the matter, the Supreme Court heard argument in U.S. v. Nixon revolving around the president’s refusal to turn over the tapes subpoenaed by Special Prosecutor Jaworski. Nixon’s lawyers argued, among other things, that the president gets to determine the scope of executive privilege and the Court should not intervene in this intramural dispute within the executive branch between the president and the special prosecutor. Jaworski countered that the courts must decide this issue, lest the president trot out executive privilege to shield criminal behavior by himself or his subordinates.

Four days later, John Ehrlichman, G. Gordon Liddy, and two other former White House aides were convicted of conspiracy for their role in the break-in at the office of Daniel Ellsberg’s psychiatrist back in 1971.

On July 19, the House Judiciary Committee, having heard testimony from dozens of witnesses and reviewed hundreds of documents, heard the case for impeachment summarized by its lead counsel, John Doar. (As deputy assistant attorney general and later assistant attorney general of the Civil Rights Division under Presidents Kennedy and Johnson, Doar had already made his mark in history.) Doar recommended in no uncertain terms the impeachment of Nixon, citing his “enormous crimes.”12 Nixon’s press secretary, Ron Ziegler, who had earlier dismissed the Watergate break-in as a “third-rate burglary,” now dismissed Doar as a “partisan ideologue” operating in a “kangaroo court.”13

July 24 brought the most decisive event in the two-year saga. In an opinion signed by Chief Justice Warren Burger, a Nixon appointee, the Supreme Court unanimously rejected Nixon’s claim of executive privilege and ruled that the White House must turn over the subpoenaed tapes. The White House announced that it would comply.

That evening, at 7:45 p.m., the House Judiciary Committee began debate over impeachment, with each of its 38 members allotted 15 minutes. After roughly one hour, and four speakers, Chairman Rodino cryptically announced that he was “compelled to recess” the hearing for an unspecified period of time. It would later be learned that an anonymous bomb threat had been phoned in. Capitol police and bomb-sniffing dogs swept the hearing room and found nothing. Forty minutes later, the hearing resumed and remained in session until almost 11:00 p.m.

In the many hours of statements that night and over the next few days, perhaps the most memorable moment came when Barbara Jordan, an African American congresswoman from Texas, struck a personal note. She observed that when the Constitution was completed, “I was not included in that We the People. I felt somehow for many years that George Washington and Alexander Hamilton left me out by mistake. But through the process of amendment, interpretation, and court decision I have finally been included in We the People.”14

The Preamble to the Constitution declares the goal of a “more perfect union.” The union became “more perfect” when it embraced all Americans, and more perfect still when Congress opened its doors to people like Barbara Jordan. Now the gifted orator explained why that unachievable quest for perfection required removing a president who dishonored that very Constitution. “I am not going to sit here and be an idle spectator to the diminution, the subversion, the destruction” of the nation’s founding and foundational document.

On July 27, the Judiciary Committee passed an article of impeachment alleging obstruction of justice. On July 29, the committee passed a second article accusing President Nixon of abuse of power, and on July 30 a third based on the administration’s defiance of the committee’s subpoenas to turn over tapes and other documents. The committee sent a report to the full House of Representatives recommending impeachment on these three grounds.

The committee rejected two proposed articles of impeachment. One was based on tax fraud and receipt of unconstitutional emoluments (stemming from government expenditures on Nixon’s private homes), and the other was based on the secret bombing of Cambodia in 1969 and 1970—more than 3000 raids that the administration concealed and lied about.

Article 1, the obstruction of justice charge revolving around the Watergate cover-up, laid out nine specific acts of wrongdoing, including approving hush money and promising favorable treatment to various potential witnesses; making and encouraging others to make false statements to law enforcement; and more generally “interfering with the conduct of investigations” by the Department of Justice of the United States, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) , the special prosecutor, and congressional committees. Article 1 passed the Committee by a 27–11 vote.

Article 2, the abuse of power charge, included several subsections alleging misuse of the IRS to harass political enemies and misuse of the FBI and other government bodies to conduct illegal surveillance of political enemies. It passed 28–10.

Article 3, concerning Nixon’s failure to comply with subpoenas to produce evidence, passed 21–17.

The committee rejected the articles based on income tax invasion and receipt of emoluments and the secret bombing of Cambodia by votes of 26–12.

The full House never voted on impeachment. On August 5, the White House turned over the Court-ordered tapes, which laid bare Nixon’s involvement in the cover-up, including his effort to have the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) stop the FBI’s investigation into the Watergate break-in. His support in Congress and in the nation evaporated. All 10 members of the House Judiciary Committee who had voted against the articles of impeachment declared that they would now support at least Article 1.

On August 7, a delegation of Republican leaders, including former presidential nominee Senator Barry Goldwater, paid a visit to Nixon and urged him to resign. The next day, he did.

Even if he had been convicted by the Senate rather than resigned, Nixon would have remained in legal jeopardy. As noted in chapter one, a president removed from office may still be prosecuted for crimes in the court system. However, Nixon could breathe easier one month later. On September 8, his presidential successor, Gerald Ford, granted Nixon a “full, free, and absolute pardon” for any offenses he committed while president.

The Nixon saga vindicated the founding fathers’ vision of impeachment. The process was by no means entirely apolitical: The majority of the Judiciary Committee voted along party lines. But the result was exactly what we would hope for: Republicans’ resistance to impeachment ensured that it did not happen too easily or prematurely. To the contrary, more than two years elapsed between the initial evidence of wrongdoing and Nixon’s resignation. Eventually, enough Republicans came around to produce the peaceful removal of an unfit president. As a body, the House Judiciary Committee ably differentiated among the various charges and correctly identified which ones warranted impeachment.

The committee probably voted correctly with respect to at least four of the five proposed articles of impeachment. Little doubt remains about the first two. Nixon’s guilt with respect to the obstruction of justice and abuse of power charges has become ever more apparent over the years with the release of more taped conversations and other evidence. He clearly participated in the Watergate cover-up and misused various executive branch agencies in an effort to harm his political enemies. Few observers dispute that such misconduct was sufficiently serious to warrant impeachment.

A case can be made that the third article, based on Nixon’s noncompliance with the committee’s subpoenas, was premature, that as with Andrew Johnson’s response to the Tenure of Office Act, Nixon was entitled to withhold materials until courts determined that he had no basis for doing so. His defiance, while perhaps revealing and certainly maddening to members of the committee, arguably did not rise to the level of an impeachable offense. (On the other hand, the withholding of evidence made it difficult to get at the truth of the other accusations. Not impeaching on this charge might have established a perverse precedent for presidents facing scandal.) Significantly, this article squeaked by, receiving zero votes from Republicans and two “no” votes from Democrats.

The decision not to impeach based on Nixon’s alleged tax fraud and wrongful receipt of emoluments made sense on constitutional grounds. These alleged improprieties were unrelated to his official duties as president. They could be prosecuted in criminal court after Nixon left office (or at least the tax fraud could) but were not a strong basis for impeachment.

With respect to the bombing of Cambodia, opponents of impeachment made several arguments that proved persuasive even to many Democrats: Some leading members of Congress knew about the bombing and acquiesced; even after the entire Congress knew, they did not move to stop the bombings for some time, thereby effectively ratifying the bombing campaign; earlier full disclosure to Congress conceivably could have jeopardized the mission and compromised national security; and the matter was subsequently resolved by passage of the War Powers Act, which clarified when and how presidents must consult Congress when undertaking military operations.

The merits aside, pragmatism dictated forgoing these charges. The three articles of impeachment that passed described a clear and serious misuse of presidential powers. To mix in the tax fraud and emoluments claims at the Senate trial would have diluted and even trivialized the articles of impeachment that dealt with meatier matters. In the criminal law, prosecutors routinely make tactical decisions about what to charge. Senators, whom we expect to be attuned to political realities, surely may do the same.

While a powerful case can be made that the secret bombing of Cambodia violated the Constitution, the use of U.S. military force abroad frequently occurs in gray areas. Every president since and including John F. Kennedy—and many before him—used military force in controversial operations not clearly authorized by the Constitution. These controversies are best resolved in the normal political process, with resort to the courts as necessary, and perhaps by constitutional amendment to clarify the branches’ respective authority. Impeachment is not the proper venue for adjudicating such disputes.

Nevertheless, a reasonable case can be made that secret bombings of a noncombatant country were beyond the pale. But context always comes into play, and here the context included the existence of more cut-and-dried bases for impeachment. Had Nixon been impeached over the bombings, the Senate trial might have become a long and involved referendum on the Vietnam War, deflecting attention from his more obvious misdeeds and impeding the prospects of a bipartisan outcome.

One major difference between the cases of Andrew Johnson and Richard Nixon is that Johnson was never elected president, whereas Nixon received over 60 percent of the vote in a landslide of historic proportions. All things being equal, that would make the impeachment of Johnson more amenable. But the more salient difference cuts the other way—Nixon clearly committed impeachable offenses.

The overly tidy verdict of history renders the Johnson impeachment a partisan failure and the Nixon saga a bipartisan success. We are on safe ground in considering the Johnson case a failure and Nixon case a success in terms of outcome: Johnson should not have been impeached, whereas Nixon should have been (and would have been had he not resigned). However, with respect to partisanship, we should be careful not to oversimplify the differences between the cases.

When the House Judiciary Committee released its final report on August 20, 1974, two weeks after Nixon’s resignation, all 38 members opined that impeachment would have been appropriate. The release of damning tapes on August 5 made converts of those Republicans who had voted against all the articles of impeachment. But if we look at the actual votes cast, the Johnson and Nixon cases were not too dissimilar in terms of partisanship. Seven senators voted across party lines to acquit Johnson—the exact number of House members who crossed party lines to vote to impeach Nixon. Indeed, for all the claims of bipartisanship, in the Nixon case just shy of half the members of the Judiciary Committee (18 out of 38) voted the party line on all five articles. Eight Democrats voted for all five proposed grounds of impeachment and 10 Republican senators voted against all five.

To be clear, bipartisanship played a decisive and wholly welcome role in both the Johnson and Nixon cases. In the case of Nixon, historians rightly emphasize the critical roles of Woodward and Bernstein, Mark Felt (“Deep Throat”), Judge John Sirica, and Special Prosecutors Cox and Jaworski in bringing out the truth. They also praise the work of Democrats Sam Ervin and Peter Rodino, who chaired the respective Senate and House committees that investigated Watergate. But the indispensable efforts of these people would not have sufficed to remove Nixon from office but for the courage and patriotism of some Republicans in Congress. Just as the so-called Seven Tall Men spared the nation a catastrophic outcome in the trial of Andrew Johnson, the seven Republicans who voted to impeach Richard Nixon merit a special place in the pantheon of Watergate heroes.

Highest honors are reserved for Maryland Representative Lawrence Hogan, the first Republican on the Judiciary Committee to announce his support for impeachment and the only Republican to vote yes on all three of the articles that passed. Hogan explained the basis of his vote as follows:

The thing that’s so appalling to me is that the President, when this whole idea was suggested to him, didn’t, in righteous indignation, rise up and say, “Get out of here, you’re in the office of the President of the United States. How can you talk about blackmail and bribery and keeping witnesses silent? This is the Presidency of the United States.” But my President didn’t do that.15

As was the case with the Republican senators who acquitted Johnson, Hogan’s heroism proved costly. He ran for governor of Maryland that year but failed to get the Republican nomination. (His son was elected governor of Maryland some 40 years later.) Political observers attributed Hogan’s defeat to his disloyalty to his party during the impeachment process.

Another Republican member of the Judiciary Committee to vote for impeachment, Virginia’s Caldwell Butler, was a first-term congressman with a reputation for integrity who knew that he owed his place in Congress to Nixon—just two years earlier he had ridden the coattails of Nixon’s landslide. In his statement during the final debate on July 25, Butler acknowledged his debt to Nixon but noted that Republicans had long complained about and campaigned against Democratic corruption. “Watergate is our shame. . . . If we fail to impeach, we will have condoned and left unpunished a course of conduct totally inconsistent with the reasonable expectations of the American people.”16 He, too, put patriotism above party.

William Cohen, a 33-year-old congressman from Maine, angered Republicans throughout the process. In May, when the Judiciary Committee voted to send a letter to Nixon complaining about his failure to comply with the committee’s subpoenas, Cohen was the only Republican to vote in favor. In the floor debate over impeachment in July, he addressed the claim by some Republicans that every president engages in the kind of misconduct Nixon stood accused of. “Democracy may be eroded away by degree,” Cohen said. “Its survival will be determined by the degree to which we will tolerate those silent and subtle subversions.”17 Cohen’s career in public service, marked by his willingness to work across the aisle, culminated in his service as Secretary of Defense under a Democratic president, Bill Clinton.

Although the Nixon case never went to trial in the Senate, some Republican senators distinguished themselves along the way. Howard Baker and Lowell Weicker, members of the Ervin Committee, showed more interest in arriving at truth than in automatically backing the president from their party, thus infuriating Republicans nationwide who for a long time supported Nixon overwhelmingly. Kudos also to Barry Goldwater, who helped convince Nixon to resign and spare the nation the trauma of a drawn-out trial and active removal of the president. (“You can only be lied to so often,” Goldwater allegedly told his fellow Republican senators, explaining his support for Nixon’s departure.)18 Ditto Elliot Richardson, a lifelong Republican whose refusal to fire Special Prosecutor Cox sent an important message about the rule of law and marked a decisive blow against Nixon.

If the Nixon ordeal reminded us of the value of bipartisanship, it also reinforced the idea that indictable crimes are not needed for impeachment. Much of the debate over Nixon’s fate throughout 1973–74, both in the country at large and within the congressional investigative committees, revolved around that question. (Eventually it became clear that Nixon’s conduct did include criminal behavior. Indeed, as noted, a grand jury named Nixon an unindicted co-conspirator.) It came to be widely accepted that non-criminal behavior can constitute an impeachable offense. The Constitution authorizes removing the president whose improper actions threaten our system and render that individual unfit, and actions may fit that description without involving crimes on the books.

* Thus, for example, historian David Stewart, author of a fine book about the Johnson impeachment, draws the opposite conclusion from the conventional wisdom that the Johnson case discredited impeachment: “By coming so close to a conviction, the impeachers established that . . . the nation need not wait until the end of a four-year term to jettison a president.” Moreover, “the experience chastened the most powerful person in the nation, who had committed many blunders, whether or not they warranted his removal from office.” Finally, the peaceful impeachment process served as “a constitutional outlet for violent political passions.” But Stewart does not address whether things would have turned violent had Johnson been convicted and removed. It is questionable to praise the pursuit of a remedy as a peaceful outlet if the peacefulness depends on failure. David Stewart, Impeached: the Trial of Andrew Johnson and the Fight for Lincoln’s Legacy (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2009), p. 323.

* In a quirky footnote to history, one of the three “no” votes in the Senate came from Missouri senator Thomas Eagleton, briefly the Democrats’ vice presidential nominee the previous year, until he was forced to step down after revelations that he had been hospitalized for depression on several occasions.